Abstract

Despite growing technological and economic viability, the adoption of solar energy in the United States remains low. This research synthesizes 96 peer-reviewed publications from 2000 to 2024 to investigate how public perceptions, user psychology, institutional setups, and socioeconomic contexts shape solar energy adoption decisions in the United States. Drawing on a PRISMA systematic review of publications gathered from Scopus and Web of Science databases, the study reveals that solar adoption is influenced not only by environmental concern and perceived economic benefits but also by institutional trust, social norms, cognitive biases, and demographic characteristics. Key findings highlight that while higher income and education levels enable adoption, marginalized communities face persistent barriers, including institutional distrust, limited awareness, and constrained access to financing. Residential rooftop solar projects receive higher public approval than utility-scale developments, with agrivoltaics systems emerging as a promising middle ground. This review identifies critical gaps in public awareness and institutional credibility, calling for integrated policy responses that combine financial incentives with inclusive engagement strategies. By emphasizing the socio-behavioral dimensions of energy transitions, it offers actionable insights for policymakers, energy planners, and researchers aiming to broaden solar accessibility and equity. It underscores the need for future research on identity-driven adoption behavior, participatory energy planning, and depoliticized communication to bridge the intention-action gap and accelerate the just transition to solar energy.

1. Introduction

Public perception and support are increasingly recognized as critical determinants in the diffusion and deployment of energy technologies [1], particularly solar energy. Although the environmental and economic benefits of solar energy are well established, public uptake remains uneven across regions and demographics [2]. This discrepancy suggests that technical and economic feasibility alone cannot drive the diffusion of innovation [3] and widespread technological adoption. It remains underexplored how people interpret, engage with, and make decisions about solar energy adoption in their energy portfolio.

Several studies emphasize that the transition to renewable energy involves complex social negotiations [4]. Public unfamiliarity with energy systems, from fossil fuel extraction to smart grids, impairs acceptance and slows behavioral change. Moreover, attitudes are often shaped less by facts than by ideologies and cultural identities [5]. As such, adopting an integrated lens that considers social viability, personal values, psychological norms, and community-level dynamics is essential in the energy sector.

This research is particularly timely given the urgency of climate change and the United States government’s growing emphasis on distributed renewable energy [6]. A deeper understanding of public perception is essential for explaining the social dimensions influencing the adoption of solar energy alternatives [7,8]. This understanding also allows for the systematic analysis of prevailing trends and pathways in how the public perceives solar technologies [2,9]. It helps to identify critical research gaps related to public attitudes and acceptance of solar energy systems [4,10], which will inform policymakers to anticipate resistance, tailor engagement strategies, and design inclusive energy policies.

The dynamic nature of public perception in response to policy shifts, media narratives, and evolving climate discourses remains underexplored. According to studies like Carlisle et al. [2] and Alipour et al. [9], public perceptions of solar energy are influenced by continuous social disputes and policy circumstances rather than being static. Yet, longitudinal studies that capture how perceptions change over time and across different socio-political environments are scarce. There is also a critical need for more interdisciplinary research that integrates behavioral science, communication strategies, and community engagement models to design inclusive energy policies [4,10].

There are also significant research gaps in understanding the nuanced institutional, social, cultural, and psychological factors that shape public perception of energy sources. Much of the existing literature focuses heavily on technical feasibility and economic incentives, often overlooking how social identities, historical experiences with energy systems, and trust in institutions influence adoption decisions [4,5]. As Ajibade and Boateng [7] highlight, public perceptions are deeply rooted in lived experiences and cultural narratives, making it essential for research to explore how these factors interact with attitudes toward solar technologies. There is also limited exploration of how marginalized communities, who often bear the brunt of energy injustices, perceive and engage with solar initiatives [8]. Without addressing these gaps, efforts to promote solar adoption risk alienating key demographic groups and perpetuating existing social inequities.

2. Materials and Methods

This study adopts the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) framework [4,11,12,13] to critically analyze public perceptions of solar energy adoption, focusing particularly on the interplay of social, psychological, and institutional factors that influence decision-making in the United States. Systematic reviews, like PRISMA, have proven valuable in synthesizing fragmented knowledge in complex domains such as energy transitions and climate behavior [8,14], enabling researchers to identify consistent patterns, theoretical gaps, and methodological limitations across a broad set of studies. Out of 27 steps in the PRISMA review framework, 20 were implemented at various stages of this review, including the identification of journal articles, their analysis, drawing of findings and conclusions on solar energy perception, and identification of adoption determinants in the United States (Further details in Supplementary Material S1). Seven steps from the list were not applicable to this analysis, including reviewer registration information, registration amendments, review protocols, assessment bias risks among selected studies, conflicts of interest of reviewers, and the template for data collection forms [11].

The research integrates both quantitative and qualitative evidence from peer-reviewed publications, reflecting a mixed-methods synthesis and PRISMA framework that captures the richness of both quantitative trends and contextual insights [15,16]. This integration offers a holistic and nuanced understanding of the complexities surrounding solar adoption behaviors and challenges in the United States, especially as they relate to social learning, behavioral inertia, institutional trust, and spatial equity in energy access.

2.1. Publication Search and Selection

An extensive search of peer-reviewed literature was conducted across two prominent academic databases, Scopus and Web of Science, encompassing peer-reviewed articles from 2000 to 2024, without considering the backtracking of publications. Search queries employed keywords focused on public perception, renewable alternatives, and geographic constraints (The United States). Multiple iterations of searches were conducted using a combination of words, ranging from broad and general to specific to the United States and public perception. The first combination of words used was “renewable energy perception,” which returned 2612 in Scopus and 2541 in the Web of Science databases. It helped to understand the landscape of research on renewable energy perception, leading to the second iteration of the keywords. In the second iteration, the search key terms were modified to scope the search to the United States as “renewable energy perception United States”. It returned 160 publications in Scopus and 237 on the Web of Science. This demonstrated that there is a sizeable number of research focused on renewable energy perception in the United States. This led to a focus on solar energy in the search.

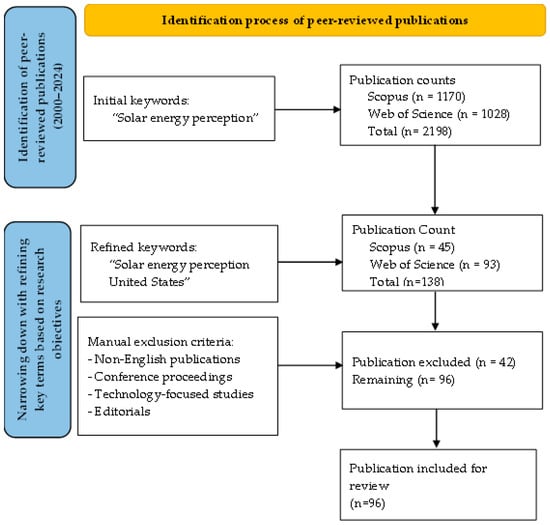

The second combination of words was focused on solar energy perception. As illustrated in Figure 1, the search yielded 1170 articles in Scopus and 1028 in Web of Science. When refining the search with keywords “Solar energy perception United States”, 45 publications from Scopus and 93 from Web of Science (a total of 138) were retained. A manual relevance screening (exclusion of the solar thermal, non-English publications, conference proceedings, solar engineering, and editorial) further distilled this set to 96 publications deemed highly pertinent to the research objectives.

Figure 1.

PRISMA 2020 Flow Diagram Illustrating Publication Search and Selection Steps and Processes [11,13].

This iterative approach ensured the inclusion of only the relevant studies. Ultimately, the review concentrated on literature pertaining to the United States, reflecting the geographic scope of this research.

Using steps prescribed by the PRISMA Framework, the progressive filtering of search results clearly illustrates the significant narrowing of relevant research when focusing specifically on solar energy perceptions within the United States. The limited number of studies highlights a critical gap in the literature and underscores the importance of further investigation in this area.

Besides the key phrases (i.e., “solar energy perception United States”) search in both databases, the final selection of studies adhered to the following inclusion criteria, executed manually in the process:

- Peer-reviewed journal articles published between 2000 and 2024 [17].

- Research explicitly addresses public perceptions, social acceptance, and behavioral influences related to solar energy adoption [18].

- Exclusion of non-English language publications, solar thermal-related studies, conference proceedings, editorials, and studies focused solely on the technical or engineering dimensions of solar energy without considering social, cultural, or behavioral factors [19].

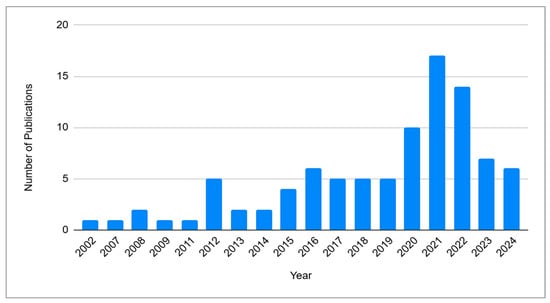

Following the application of these exclusion criteria, a total of 96 full-text articles were subjected to the analysis. Figure 2 tallies the distribution of publication counts by years, providing insights into the evolution of research in this field. The number of publications grew continuously between 2000 and 2021 and then started to decrease.

Figure 2.

Distribution of Selected Publications from 2000 to 2024.

2.2. Review Process: Codes, Themes, and Weights

A rigorous inductive thematic coding process [20] and visualization of the research trends [21] were conducted, following established qualitative analysis methods and keyword mapping [21] to systematically identify and categorize key patterns within the publications [22], where qualitative and quantitative data were extracted. The approach allows for a structured and transparent analysis of complex qualitative data, enabling the identification of recurring themes.

Each code within a theme was assigned a weighted importance score based on its frequency. A linear combination method, commonly used in multi-criteria decision analysis (MCDA) frameworks [23,24], was applied to combine these weights into a single composite value. This approach quantified the relative impact of each factor, specifically psychological factors, socioeconomic variables, and institutional setups, on public perception and adoption decisions.

The methodology, combining systematic review procedures [25,26] with a structured linear combination of theme weights, provided a robust, transparent, and replicable approach. It ensured the synthesis of the complex interactions between psychological, behavioral, socioeconomic, and institutional factors [9]. Consequently, the outcomes of the study not only clarify existing knowledge but also identify critical gaps, guiding future research directions and policy formulation aimed at enhancing solar energy adoption in the United States.

2.3. Setting Scales for Codes and Themes

A scaling approach was established to evaluate the relative significance of various factors affecting solar energy uptake across thematic categories. This process combined a review of the frequency of each factor appearing in the literature with a critical interpretation of the emphasis placed on its role in shaping adoption outcomes. The aim was to create a consistent yet flexible evaluative process that could accommodate both the code frequency and the conceptual weight assigned to different factors across four domains: psychological and behavioral influences, socioeconomic and institutional conditions, public perceptions of solar project types, and structural barriers to adoption [14,15].

Across all domains, the influence typology was grounded in thematic coding, comparative frequency, and the interpretive weight placed on each factor within the reviewed studies. By integrating these components, the scaling framework maintained methodological consistency while accommodating the thematic diversity inherent in the literature. This approach provided a structured yet flexible means of synthesizing qualitative insights and empirical patterns into a coherent assessment of the factors shaping solar energy adoption in the United States.

For the psychological and behavioral domain, ratings were derived from a combination of code frequency and interpretive prominence within published studies. A factor within the domain was classified as having a high influence when it appeared in a substantial number of publications (typically more than 15) and was consistently identified as a primary driver of adoption behavior. For example, climate change concern, cited in 22 studies, was repeatedly linked to pro-sustainability attitudes and a greater willingness to install residential solar systems [27]. Social norms (peer effects), cited in 18 studies, were also classified as high influence due to their consistent association with neighborhood clustering and peer-based visibility effects that reinforce adoption behavior [28]. A moderate to high influence rating was assigned to perceived self-efficacy, which appeared in 15 studies and was typically associated with individuals’ confidence in understanding, operating, or maintaining solar technologies, although often moderated by access to information and support systems. Factors with moderate influence were those noted less frequently or framed as supplementary motivators; for example, aesthetic preferences, cited in 10 studies, influenced adoption but were rarely emphasized as core motivations. Moderate to high influence was also assigned to psychological deterrents such as status quo bias and temporal myopia, identified in 14 studies as recurring cognitive barriers that reduce responsiveness to long-term benefits and inhibit the uptake of solar technologies [8,29].

In the socioeconomic and institutional domain, influence was similarly determined through a combination of code frequency and thematic centrality across published studies. A moderate to high influence rating was assigned to household income, cited in 15 studies, as higher income levels were consistently associated with a greater likelihood of adoption, primarily due to improved ability to manage upfront installation costs [30]. Education level, cited in 12 studies, was also rated as a moderate to high influence, given its recurring association with increased awareness and receptivity to solar technology, although its effect was often mediated by information access and socioeconomic context. Financial incentives, including rebates, tax credits, and leasing options, were cited in 20 studies and classified as a high influence, especially for enabling adoption among low- and middle-income households by reducing cost barriers. Institutional factors such as trust and fairness, cited in 17 studies, also received a high influence rating, as transparent planning processes and public confidence in solar initiatives were shown to significantly improve participation rates. Conversely, institutional opacity, regulatory complexity, and a lack of community engagement have been identified in previous research as eroding public trust and discouraging involvement in solar programs [31,32].

Since public perception is shaped by both social narratives and spatial context, frequency alone was insufficient. Projects with generally positive perception were discussed in multiple studies with clear indicators of public approval, such as residential rooftop systems, which were framed as familiar, beneficial, and community-aligned [33]. Mixed to negative perceptions were applied to project types like utility-scale solar farms, which were often associated with land-use conflicts, aesthetic disruption, or perceived imposition on local values [34]. Projects classified as having high potential but moderate awareness, such as agrivoltaics, were those that appeared less frequently in the literature but were framed positively when discussed, indicating strong conceptual appeal despite limited public familiarity [35].

For the barriers to adoption, the same frequency-plus-emphasis logic was applied, but with a focus on deterrents rather than enablers. Barriers labeled as having a high negative impact were those cited in more than 15 studies and consistently identified as major obstacles, such as high upfront costs, lack of financing options, and widespread misinformation [36,37]. Factors with negative influence included those cited slightly less frequently but still framed as persistent impediments, such as partisan ideological resistance or regulatory complexity [32]. In each case, influence ratings reflect not only how often a barrier was mentioned but also the degree to which it was described as obstructing progress in different policies and community contexts.

3. Results and Key Findings

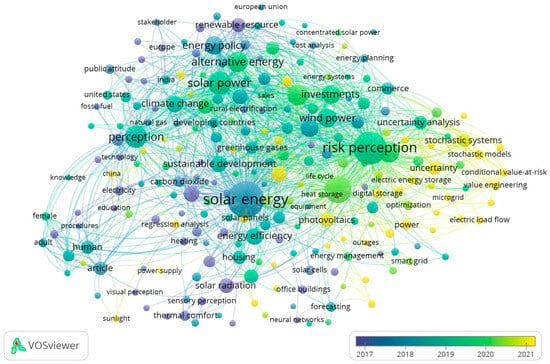

This section explains how people perceive and make decisions on solar energy. The findings show that adoption is often influenced by how individuals assess personal risk, draw from social cues, and evaluate their own ability to use the technology effectively [28,38]. This has been a growing research area since 2000. Figure 3 illustrates the co-occurrence map among publications in Scopus. It shows that publications related to solar energy perception are emerging in the context of risk, uncertainties, and decentralized systems (microgrid, energy storage, smart grid, optimization of flow, and photovoltaics).

Figure 3.

Co-occurrence of keywords [21] 10 times or more in publications on solar energy perception from 2000–2024 in Scopus.

Socioeconomic conditions, particularly income and education, also strongly affect adoption, with lower-income households consistently facing affordability challenges despite positive attitudes [39,40]. Trust in institutions and perceptions of fairness in policy design further shape public support, especially where community engagement is limited [41,42]. These insights form the foundation for the more detailed thematic discussion that follows.

3.1. Psychological and Behavioral Factors

The review revealed that while technological advancements and financial incentives remain significant drivers, they are insufficient in isolation to achieve widespread adoption. Instead, individuals’ knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions of solar energy play a critical role in shaping their willingness to adopt such technologies. The publications suggest that social and behavioral factors, such as enhancing public awareness, addressing misconceptions, and fostering positive attitudes toward solar energy, are integral components of the adoption process and must be addressed alongside technical and economic considerations in policy and programmatic interventions.

Public perceptions of solar energy are significantly influenced by a complex interplay of psychological (e.g., individual attitudes, underlying value systems, and cognitive abilities) and behavioral (e.g., personal decisions, actions, and social connections) predispositions. These cognitive and affective factors shape how individuals interpret information about solar technologies, assess their benefits and drawbacks, and ultimately make decisions regarding their adoption and support.

Environmental concerns consistently emerge as a powerful motivator for solar adoption. According to Ter-Mkrtchyan et al. [38], individuals who recognize and worry about climate change are significantly more inclined to support or install solar technologies in their homes. A recent survey in the U.S. found that those highly concerned about climate impacts showed much greater willingness to invest in residential solar [43]. However, not all studies agree on the primacy of environmental motives. An analysis by Rai and Beck [8] suggested that environmental concern alone may not spark action unless accompanied by clear personal benefits, such as cost savings, to enhance positive attitudes and perceived control. This highlights the nuanced role of financial considerations even in ostensibly altruistic motivations.

Individuals who perceive themselves as environmentally conscious, or who experience a sense of moral obligation to act sustainably, are significantly more inclined to invest in residential solar technologies, controlling for other factors. These intrinsic motivations reinforce pro-environmental behaviors, including the installation of solar panels, thereby complementing external social influences.

The role of social dynamics in influencing solar energy adoption is increasingly recognized within the literature. Social norms and peer influences are particularly significant factors shaping household decision-making regarding renewable energy technologies. Empirical studies have demonstrated that homeowners are more inclined to consider the installation of solar photovoltaic (PV) systems after observing adoption within their immediate social networks, resulting in observable clustering effects across communities [28]. This phenomenon, often described as social contagion, underscores how peer effects not only encourage adoption but may also lead to larger-scale installations through the creation of a bandwagon effect that normalizes and legitimizes solar adoption within a neighborhood context [28].

Despite favorable environmental attitudes and demonstrable financial returns, adoption decisions are often impeded by cognitive and psychological barriers. Kunreuther et al. [44] highlight the impact of behavioral biases such as status quo bias and temporal myopia, which lead individuals to overemphasize immediate inconveniences and undervalue long-term benefits. These tendencies contribute to decision inertia and herd behavior, wherein individuals avoid adopting solar technologies even when such investments are economically rational and socially endorsed. Consequently, the presence of these biases suggests that providing purely economic or technical information may be insufficient to overcome entrenched behavioral patterns, underscoring the need for integrated policy and communication strategies that account for both rational and non-rational dimensions of decision-making.

Perceptions of ease and efficacy also matter. According to the Theory of Planned Behavior, if individuals feel confident in their ability to install and use solar technology with high perceived behavioral control or self-efficacy, their intention to adopt increases [45]. Informational interventions can bolster this sense of efficacy.

A lack of knowledge or misconceptions about technology can dampen confidence. Many consumers remain uncertain about how solar panels will integrate into their daily lives or doubt their performance, reflecting a persistent awareness gap. For example, some prospective adopters express concern about the aesthetics of rooftop solar units or worry about maintenance, which in turn affects their attitudes. While such factors (e.g., aesthetics of panels) are typically secondary, they still exert a moderate influence on decision-making.

In summary, the decision to embrace solar energy is not purely economic; it is equally a product of environmental values, social context, perceived ease-of-use, and psychological biases. Table 1 summarizes key psychological and behavioral factors identified in the literature and their relative influence on solar adoption.

Table 1.

Key Psychological/Behavioral Factors Influencing Solar Adoption.

Despite these insights, there remain open questions about how personal psychology drives solar adoption. For example, research has called for further examination of the role of environmental self-identity, how seeing oneself as a “green” person correlates with actually installing solar panels. There is a need to validate comprehensive behavioral models (e.g., the value-identity-personal-norm framework) to better explain pro-sustainable actions like solar adoption [7]. Understanding the nuanced interplay of identity, personal norms, and information could improve the design of interventions that encourage broader adoption.

3.2. Socioeconomic and Institutional Factors

Beyond the influence of individual attitudes, a complex interplay of socioeconomic and institutional factors shapes the public adoption of solar energy technologies. A consistent pattern emerging from the reviewed literature highlights income level and educational attainment as critical predictors of solar energy adoption [40].

According to Sharma [40], households with annual incomes exceeding approximately $60,000 and individuals possessing at least a college degree demonstrate a markedly higher likelihood of both familiarity with solar technologies and actual adoption. This trend is largely attributable to their enhanced financial capacity to make upfront investments and their greater exposure to information regarding renewable energy technologies. Conversely, lower-income populations often encounter substantial financial barriers, rendering the adoption of solar energy systems unattainable without external financial assistance or policy incentives.

Individuals with higher exposure to scientific and environmental education, whether through formal academic pathways or self-directed learning, are more likely to understand the environmental and economic benefits of solar technologies and exhibit greater confidence in navigating the installation and maintenance processes [9].

Homeownership further reinforces these disparities. The review results suggest that homeowners, particularly those residing in single-family dwellings, represent the primary adopters of rooftop solar photovoltaic (PV) systems [19]. In contrast, renters and individuals residing in multi-family housing complexes face significant limitations, often lacking the authority or structural feasibility to implement such technologies [44].

Demographic trends play an increasingly important role in shaping future adoption patterns. Younger generations, particularly those classified as Generation Z, are demonstrating heightened interest in sustainable and clean energy solutions [46]. Kc et al. [47] observed that young homeowners exhibit a strong preference for adopting renewable energy technologies, including solar PV systems. This demographic trend suggests that as these environmentally conscious cohorts transition into homeownership, the overall rate of solar energy adoption is expected to rise, potentially accelerating the broader transition toward sustainable energy systems.

However, socioeconomic factors do not act in isolation. Institutional support and context are pivotal in converting willingness to action. Government and policy incentives greatly affect the economic feasibility of solar adoption. Clear and substantial financial incentives (such as rebates, tax credits, or feed-in tariffs) have proven crucial for enabling uptake among middle- and low-income households.

When generous incentives or financing programs are in place, they effectively reduce the upfront cost barrier and widen access to solar energy. Studies confirm that the availability of rebates or subsidies is strongly correlated with higher rates of residential solar installations [39]. However, without supportive policies, even people who are interested in adopting solar energy may delay or completely forgo installation because of financial barriers.

The review demonstrates that institutional factors play a crucial role in shaping community perceptions of solar energy initiatives. Public trust in government agencies, electric utilities, and project developers has a significant influence on how communities respond to such projects. For example, Goedkoop and Devine-Wright [48] demonstrated that perceptions of fairness and inclusive decision-making processes improve public acceptance of renewable energy projects. Similarly, Horne et al. [41] found that homeowners with higher trust in utilities and government institutions are more likely to support and adopt rooftop solar systems.

A history of poor community engagement or opaque permitting processes breeds skepticism. A national review noted that despite broad support for solar energy in principle, local opposition often arises when large projects are pursued without meaningful public input, exacerbating fears of unfair outcomes [42]. Interestingly, distrust in traditional institutions can sometimes spur pro-solar behavior in a different way: households that distrust their utility companies or the central grid may be more inclined to install rooftop solar as a form of personal energy autonomy [41]. In this sense, lack of trust in institutions can either hinder large-scale efforts or motivate individual-scale adoption, depending on context.

The findings indicate that higher socioeconomic status tends to facilitate solar adoption; however, equitable growth of renewable energy requires supportive institutional frameworks. Policies and incentives are critical for bridging the gap so that solar is not limited to the wealthy. Table 2 summarizes several key socioeconomic and institutional factors and their observed effects on adoption behaviors.

Table 2.

Socioeconomic and Institutional Factors Affecting Solar Adoption.

Despite a broad understanding of these factors, gaps remain in the knowledge of socioeconomic factors. Sociodemographic influences can vary by context, and further research is needed to disentangle how characteristics like age, income, and culture interact to shape acceptance of renewable energy [49,50].

Policy research suggests that one-size-fits-all incentive programs may not be optimal. The relevance of incentives, e.g., Investment Tax Credit, rebates, and Solar Renewable Energy Credits, is influenced by social, economic, and financial characteristics of households and communities. Previous studies have shown that having multiple incentive programs in place increases the solar adoption rates, but not all of them may be relevant for all income groups [51]. Future efforts should consider targeted policies designed for specific segments: for example, tailored support for low-income communities or leveraging social network effects in tight-knit neighborhoods as a way to address non-financial barriers to adoption [52]. Exploring such nuanced policy designs would help ensure that the benefits of solar energy are accessible across all segments of society, not just the affluent or the well-educated.

3.3. Social Acceptance of Large-Scale and Rooftop Solar

Public acceptance of solar energy projects can differ depending on the scale and context of deployment [50,53]. Small-scale installations (like residential rooftop solar or community-shared solar gardens) generally enjoy high levels of acceptance. These distributed projects are often seen as aligning with individual and community interests. Homeowners appreciate the direct benefits (reduced electricity bills and promoting energy independence).

In contrast, utility-scale solar farms (large arrays of solar panels installed on open land) tend to provoke more mixed or even negative reactions, especially in rural or suburban communities. The reviewed publications document a range of community concerns around large solar developments. A common perception is that utility-scale facilities might industrialize the landscape and threaten local land-use and rural character [54].

This review identified well-documented concerns among residents in agricultural areas regarding large-scale solar projects. For example, surveys in the Great Lakes region of the United States identified that one of the most prevalent objections to large solar developments was the fear of negative impacts on farmland and the pastoral scenery that defines rural communities [54]. Other frequently cited concerns include visual aesthetic impacts, potential harm to local wildlife and ecosystems, and anxieties over property values or tax implications [2].

While solar energy generally enjoys a favorable public perception nationally, opposition often emerges when projects are proposed near residential areas, a phenomenon commonly described as “Not In My Backyard” (NIMBY) [42]. This review found that such opposition intensifies when community members feel excluded from the decision-making process or perceive that decisions are made by outside entities without consideration for local values and preferences [55].

By contrast, rooftop solar is typically met with positive attitudes or at least minimal opposition [41,56]. Because rooftop panels are installed on individual homes or businesses and have a smaller footprint, they generally avoid triggering land-use conflicts common with large-scale projects.

In fact, distributed solar is often seen as a way to strengthen communities by contributing to cleaner air and enhancing resilience without altering communal land [53]. Communities support the idea of solar panels on schools, homes, and commercial buildings, viewing it as a practical and commonsense use of existing structures. Public surveys consistently show that people approve of solar energy in their communities, particularly when projects are small in scale and locally owned [10]. When projects are community-driven, such as cooperative solar funded and used by local residents, acceptance rates tend to be even higher due to the direct local benefits [57]. Emphasizing these local benefits and ensuring community control are thus key strategies for improving social acceptance of solar energy.

There are also strategies to improve the acceptance of larger solar projects by aligning them with local values. One promising approach is agrivoltaics, the co-location of solar panels with agriculture (such as installing panels above crops or pastures). This dual-use concept addresses land-use concerns by allowing continued agricultural production alongside energy generation. Reviewed studies suggest agrivoltaics systems can create synergies: they provide shade that can reduce crop heat stress and simultaneously produce electricity, offering farmers a supplemental revenue stream. It provides a win-win situation for energy and agricultural production, which bolsters the land-use efficiency [58]. Publications have shown that co-locating solar with farming has reduced weather-related financial risks for farmers while boosting overall land productivity, effectively acting as a partial substitute for crop insurance by diversifying income [24,59,60,61]. Further studies by Barron-Gafford et al. [32] and Weselek et al. [62] also highlight that agrivoltaics systems can significantly improve water efficiency and crop resilience under changing climate conditions.

Another important factor is place attachment, and the emotional and cultural connection people have with their locality. Research indicates that homeowners with stronger attachment to their place are more likely to adopt residential solar energy than those without such ties [56,63]. This finding is further reinforced by Tongsopit et al. [64], who observed that community identity and cultural ties directly influence energy-related decisions, especially in rural areas.

The context matters enormously for social acceptance of solar. Small, distributed projects integrated within communities tend to be welcomed, whereas large, centralized projects must proactively address local concerns to gain approval. Table 3 contrasts public perception trends for different project types, illustrating the acceptance gap between rooftop versus utility-scale solar, as well as the potential of hybrid solutions like agrivoltaics.

Table 3.

Public Perceptions by Solar Project Type.

There are some alignments of the findings with other studies in Table 3. The residential rooftop solar has higher acceptance among households due to its role in reducing utility costs [65,66] and energy burdens for families [67] compared to some of the environmental benefits. The energy independence and energy backup systems during extreme weather are motivators for residential rooftop solar installations [65,66]. Compared to rooftop photovoltaics, the publications have some concerns over the utility-scale solar installations. Among them, the distance from the residence has been a major determinant besides aesthetics and economic benefits [68,69]. There is strong support for agrivoltaics [70,71,72], but given the noble nature of the approach, there is a limitation in understanding about the benefits and implementation models of this emerging solar technology.

Ongoing research is exploring ways to more accurately measure and enhance social acceptance of renewable energy. One noted challenge in this study is the inconsistent use of the term “NIMBY” to diagnose opposition. Scholars argue that a common definition of a NIMBY attitude should be adopted to avoid oversimplifying complex local dynamics [55]. The cost–benefit analysis for utility-scale solar installations is another important direction set by this review.

Whereas surveys and quantitative studies can reveal general attitudes (e.g., what percentage of people support or oppose a project), they often fail to capture the deeper narratives of why communities feel the way they do. Historic identity, sense of place, and local experiences with past projects can strongly influence acceptance. Yet, these qualitative aspects are sometimes overlooked. Future work should aim to integrate qualitative insights. For example, understanding how cultural values or community stories shape energy opinions, rather than just numerical polling [73]. By addressing these gaps and engaging with communities on their own terms, developers and policymakers can better anticipate resistance and cultivate genuine social license for both small and large solar energy projects.

3.4. Barriers to Solar Energy Adoption

Despite the generally positive public attitudes toward solar energy and its well-documented benefits across publications, several persistent barriers continue to slow the widespread adoption of solar technologies. Reviewed publications highlighted that a fundamental impediment is a lack of information and familiarity. Large segments of the public are not well-informed about how solar technology works, its reliability, or how to go about installing a system. This technological unfamiliarity breeds hesitation. Indeed, studies have found that the public is often unfamiliar with energy technologies in general, from fossil fuel systems to smart grids, and solar is no exception [4]. People who have never been exposed to solar panels (either directly or via trusted acquaintances) may harbor undue concerns about maintenance, lifespan, or safety [63]. Misinformation in this domain can further exacerbate the issue. In some cases, individuals receive conflicting messages, for example, exaggerated claims about solar energy being too weak to power a home.

Twelve studies in the review identified political identity as one of the most frequently discussed sociopolitical barriers to solar energy adoption. The influence of political ideology on renewable energy perception is well-documented, with Crowe [19] providing particularly compelling evidence on how partisan divides shape public attitudes toward solar policies and adoption. Based on reviewed publications, economic and financial barriers remain the most immediate and cited obstacles to adoption [63]. The high upfront cost of installing solar panels is a deterrent for many households. Even though the long-term savings on electricity bills can be substantial, the initial investment (equipment purchase and installation labor) is often thousands of dollars, which can be prohibitive for middle- and low-income families without financing support. Additionally, there may be ancillary costs, such as reinforcing an old roof or installing new wiring, which contribute to the perceived expense. The payback period for energy savings to recoup the initial cost can span several years, and some homeowners are unwilling or unable to wait that long for a return on investment.

Limited access to capital or credit thus prevents many willing adopters from proceeding. Furthermore, even when incentive programs exist to offset costs, a lack of awareness or understanding of these incentives is a barrier. Many households are unaware of government rebates, tax credits, or utility net-metering programs that could make solar energy more affordable, or they find the process of claiming these incentives too complex. One study on passive solar technology adoption identified a lack of consumer demand as the biggest hindrance, attributing it in part to low awareness and insufficient economic incentives to spark interest [63]. This indicates that better promotion of incentive programs and perhaps simplification of the enrollment process could help translate latent interest into action.

Not all barriers highlighted in publications are economic and financial; some are simply practical. Homeowners may be unable to install solar panels due to structural issues like shaded or weak roofs. Others live in rental properties or multi-unit buildings where rooftop installations are not feasible. In such cases, expanding access to community solar programs and shared solar initiatives becomes essential to broaden participation [74].

Behavioral factors also play a significant yet subtle role. Even when solar is financially advantageous, individuals often procrastinate or resist change due to cognitive biases like status quo bias and risk aversion [41]. People tend to stick with familiar options, even if switching to solar would be in their long-term financial interest. Some consumers also demand unrealistically short payback periods, viewing the investment through a lens of immediate risk rather than future gains. These behavioral tendencies suggest that simply providing rational economic arguments is not enough; targeted messaging, social proof through neighborhood adoption, and assurances such as performance guarantees can help overcome these psychological hurdles. Major barriers to solar energy adoption are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Major Barriers to Solar Adoption.

Addressing the identified barriers requires multifaceted strategies rooted in the patterns and solutions proposed across the reviewed publications. First, informational campaigns and demonstration projects have been widely suggested as effective ways to demystify solar technology and build public trust [4]. Studies have shown that unfamiliarity with technology creates hesitation, and direct experiences such as community workshops or solar open house events allow individuals to interact with solar installations and ask practical questions. This approach directly responds to the barrier of technical unfamiliarity highlighted in several studies.

Combating misinformation was another frequent recommendation in the reviewed literature. Crowe [19] emphasizes the importance of coordinated public messaging to correct false narratives around solar energy. Engaging trusted local voices, including community leaders and early adopters [3], has been shown to be effective in sharing positive and accurate experiences. This helps counteract misinformation and reduces fear and uncertainty, especially in communities where skepticism about renewable technologies remains high.

On the financial front, the reviewed studies consistently pointed to the need for stronger policy support and innovative financing options to reduce the cost burden [63,74]. Solutions such as rebates, tax credits, low-interest loans, and pay-as-you-go financing models were frequently highlighted as critical tools for making solar energy more accessible to low- and middle-income households. In addition, streamlining permitting and interconnection processes was noted in multiple studies as a necessary step to remove bureaucratic barriers that slow adoption. Several studies also stressed the importance of addressing sociopolitical divides by reframing solar energy as not only an environmental solution but also an economic opportunity. Highlighting job creation, long-term energy savings, and increased energy independence can broaden the appeal of solar technologies beyond environmentally motivated individuals [42]. This approach directly tackles partisan and ideological biases that were frequently identified as barriers in the reviewed literature.

Several studies have identified a notable disparity between public attitudes towards renewable energy and actual behavioral adoption of solar technologies, known as the intention-action gap. This phenomenon typically arises from practical impediments such as financial constraints and limited technological accessibility [74]. Furthermore, the widespread lack of familiarity and adequate understanding regarding emerging energy technologies among the general public remains a persistent and significant challenge, highlighting the need for enhanced outreach and educational interventions [4].

4. Discussion

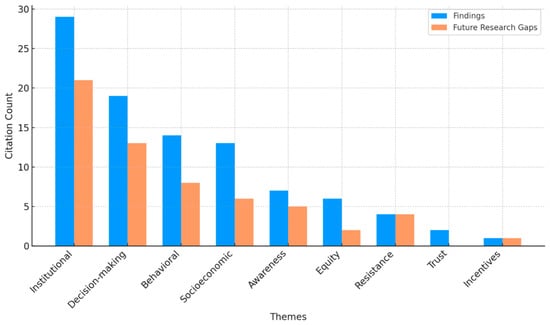

The discussion integrates insights from 88 documented findings and 54 research gaps, drawing heavily on thematic patterns, stakeholder perceptions, and systemic challenges identified in this review. The charts and tables provided in this section further quantify the trends and gaps in the four domains.

4.1. The Integration of Social, Economic, and Institutional Factors

While the findings were initially categorized into four broad areas: psychological and behavioral factors, socioeconomic and institutional dynamics, public perceptions of solar projects, and structural barriers, a closer look revealed that many of these categories contained distinct subcomponents that are emphasized by published literature. For example, within the psychological and behavioral category, themes such as individual decision-making habits and resistance to change were consistently mentioned in different contexts. In the socioeconomic and institutional domain, studies frequently distinguish between institutional quality, public trust, equity in access, and the presence or absence of financial incentives. Other dimensions, like education and knowledge, stood out on their own due to their central role in shaping early attitudes toward solar energy. This detailed unpacking led to the identification of eight core themes with higher concentrations: institutional, decision of adoption, behavioral, socioeconomic, education/knowledge, equity, resistance, and incentives. The influence of each theme is rated as Yes, Partial, or No, based on empirical evidence drawn from 96 reviewed studies.

These themes were assessed against three major factors in the adoption process: whether they influence awareness of solar energy, whether they shape trust in relevant institutions, and whether they facilitate or hinder decision-making. The relationships are summarized in Table 5.

Table 5.

Cross-Tabulation of Selected Themes by Influence Types.

Institutional factors were the only theme to be rated as a strong influence across all three categories. Evidence consistently showed that credible institutions increase public awareness by offering clear information, build trust by demonstrating accountability, and support decision-making by delivering services reliably [41,75]. In projects where government agencies or utility companies maintained transparency and fairness, adoption levels were significantly higher.

The decision to adopt solar itself also scored highly across all dimensions. It was found to directly affect people’s capacity to evaluate solar options and to act on them. While decision-making supports awareness and engagement, its influence on trust is more conditional. Several studies observed that decisions are shaped by personal and social context, including peer influence and the perception of risk [40,45]. However, when institutions fail to provide adequate guidance or follow through on commitments, the decision-making process becomes strained.

Behavioral factors followed a similar pattern. They strongly influence both awareness and decisions, but only partially impact trust. People who consider themselves environmentally responsible are more likely to explore solar energy and act on their intentions [7]. Still, behavioral motivations can falter in the absence of reliable institutional support, which limits their trust-building potential.

The role of socioeconomic conditions was rated as a strong influence on awareness and decision-making, but only a partial influence on trust. Income and education levels consistently shaped people’s understanding of solar technologies and their ability to invest in them [33]. However, socioeconomic privilege alone does not guarantee institutional trust, especially in communities that have historically been underserved. Education was confirmed to have a direct influence on increasing public interest in solar energy and plays a partial role in encouraging decisions. Yet, it showed no direct influence on trust. While information is essential, it must be accompanied by equitable access and institutional clarity to support long-term engagement [27,74].

The reviewed publications rated equity as a partial influence across all three categories. Although mentioned less frequently than other themes, it had strong implications in areas with social and economic disparities. Equity influences trust, particularly when solar adoption programs are seen as exclusive or biased. Sunter et al. [31] found that racial and class disparities in solar deployment eroded trust even when communities were aware of the technology and its benefits.

Resistance was found to play a partial role in shaping awareness and trust, and a stronger role in decision-making. In communities where solar panels are perceived as unattractive, complicated, or unfamiliar, resistance can hinder or prevent their adoption. Bollinger and Gillingham [28] noted that in neighborhoods without visible solar installations, residents were less likely to make the switch, even if they had the resources and information.

Finally, incentives had a strong and direct influence on all three dimensions. They increased awareness when well-communicated, built trust when perceived as fair and reliable, and motivated decisions by lowering financial barriers. Crago and Chernyakhovskiy [33] found that well-designed incentive programs were especially effective when paired with clear guidance and minimal bureaucracy.

Altogether, these nine themes illustrate the multifaceted nature of solar energy adoption. They do not act in isolation, but rather overlap and interact in ways that shape their outcomes. Table 5 captures this dynamic by assigning each theme to a relative influence level, grounded in the frequency and depth of evidence found in the literature.

The community adoption of solar technologies is a complex process. The findings of this review align with previous studies in terms of economic incentives, environmental benefits, and sociodemographic characteristics as determinants of solar energy adoption [76]. This review identifies the institutional factors as a strong determinant of the solar energy awareness, trust, and decision-making of adoption at household and community levels, which is a cross-cutting theme among previously identified theories of energy technology adoptions, including diffusion of innovation [77,78], theory of planned behavior [77,79], value-belief-norm theory [77], and the technology acceptance model [13]. Institutional factors also influenced other themes identified during the review, including technological education and knowledge, trust-building, equitable distribution of photovoltaics, and personal decisions to adopt solar technologies.

Perception of technology, trust in institutions, shared understanding, and social cognitions are critical aspects of renewable adoption [80]. The themes of individual decisions, behavioral intentions, socioeconomic characteristics, and incentives were identified as partial determinants of awareness, trust, and decision-making of solar energy adoption in this review. They are heavily dependent on institutional factors. Besides case studies from different communities and geographies (e.g., [81,82]), there are limited reviews that have identified institutional factors as the most important theme among publications on solar energy perception in the context of changing landscapes of renewable energy adoptions in the United States. This spearheads a new research direction in the field of policy and administrative aspects of solar energy adoption using the institutional theory of renewable energy transition [83].

4.2. Research Gaps and Emerging Priorities

Institutional factors lead the thematic landscape, with the highest frequency in both existing findings (29 mentions) and future research gaps (21 mentions) (Figure 4). This pattern suggests a persistent concern about how regulatory frameworks, governance quality, and administrative capacity shape solar adoption. Even as institutional dynamics are among the most studied areas, they remain the most cited as needing further attention. Researchers appear to recognize that solving institutional challenges requires more than descriptive analysis. It demands applied insights into how reforms can be effectively implemented, especially in diverse political and cultural contexts [75].

Figure 4.

Identified Research Gaps across Publications.

Decision-making is the second most cited theme, with 19 mentions in the findings and 13 in the research gaps. This reflects a continuing interest in the cognitive, psychological, and social processes that influence whether people choose to adopt solar technology. Even though the literature has outlined many of these processes, there is still uncertainty around how to support and simplify decision-making for households across different income levels and cultural settings [40,45].

Behavioral influences rank third, with 14 citations in the findings and 8 in the gaps. This demonstrates both solid research coverage and continued interest in how everyday habits, environmental identity, and peer behaviors shape adoption patterns. Future studies may need to go beyond general behavioral drivers to explore specific interventions that can shift routines or amplify pro-sustainability norms [7,64].

Socioeconomic factors, mentioned 13 times in the findings and 6 times in the gaps, have been relatively well explored but still present important equity-related concerns. While it was noticed that income and education shape adoption outcomes, the mechanisms through which these advantages translate into action are less explored. Moreover, how policy tools can help bridge gaps for underrepresented groups remains a crucial research question [33].

Awareness, with 7 mentions in findings and 5 in gaps, remains a consistently cited area of concern. Although it may appear to be a lower priority compared to institutional or behavioral issues, its role as a foundation for all other influences should not be underestimated. Research going forward could benefit from focusing on the effectiveness of various communication strategies, especially those targeting rural, low-income, or linguistically diverse populations [27,74].

Equity, which appears 6 times in findings and just 2 times in future gaps, may be underreported in part due to its emerging relevance. Although fewer papers listed equity as a future research need, its significance is likely to grow, especially in light of recent policy movements focused on just energy transitions and inclusive access.

Resistance shows a symmetrical pattern, with 4 mentions in both findings and gaps. This suggests a balanced understanding that while resistance is a known barrier, it also requires more nuanced research. The reasons why people push back against solar adoption, whether due to aesthetics, technological skepticism, or cultural values, remain varied and context-specific [28].

Trust, which appears just 2 times in findings and not at all in research gaps, stands out as an area that may be underexplored or underreported. Given its significance in the previous section, its low visibility in future research agendas is notable. This could indicate a gap between how trust is acknowledged versus how it is systematically studied. Expanding research on the formation and maintenance of institutional trust could yield valuable insights, particularly in post-crisis or underserved regions [48].

Incentives were mentioned once in both the findings and the research gaps. While this may suggest that financial motivations are well understood, it also implies that there is limited scholarly attention to how incentive programs evolve or perform across different user demographics. Given that incentives remain one of the most practical levers for increasing adoption, future work could investigate design innovations, long-term impacts, or unintended consequences [33].

5. Conclusions

A comprehensive review of public perceptions influencing solar energy adoption in the United States sheds light on psychological, socioeconomic, institutional, and contextual factors. Key findings from this review highlighted that solar adoption decisions are not driven solely by technical feasibility or environmental benefits but are deeply intertwined with institutional trust, individual attitudes, social norms, financial capabilities, environmental concerns, and equity. Socioeconomic status, notably income and education level, substantially impacts individuals’ ability and willingness to adopt solar technologies [33], underscoring the need for targeted financial incentives and educational initiatives. The review identified rebates, tax credits, and leasing as financial instruments targeted to the low-income and minorities to boost their capacity to adopt solar technologies. Conflicting interests of policymakers and the emergence of a fossil fuel-based energy agenda in policies and programs can undermine the adoption of solar energy [84], which will lead to unfavorable institutional outcomes for solar energy adoption.

This review advances renewable energy scholarship by synthesizing diverse disciplinary perspectives, including psychological, economic, and sociopolitical aspects of solar energy acceptance and denial. It identifies critical gaps in understanding how social and cultural variables influence solar energy perceptions [85], thus contributing to a nuanced comprehension of solar energy adoption processes. This research enriches the dialogue on energy transitions by emphasizing the interplay of personal decisions, community norms, and systemic barriers, advocating for an integrative approach that balances the technical innovations of solar energy with social and institutional viability. It identifies the perception of individual capacity, pro-sustainability attitudes, household income, education levels, personal desire to maintain home appearance, status quo bias, myopia, peer-pressure from neighbors, ideological biases, and aesthetics of the neighborhood as personal and social determinants of solar energy adoption.

The findings indicate that policymakers must develop institutional frameworks for incentives and interventions that resonate with diverse demographic and socioeconomic groups. This review finds that a particular focus on promoting financial incentives to low-income families, extending educational campaigns, and mitigating misinformation can reduce the unjustified uncertainties among people. Transparent and inclusive decision-making processes centering on community priorities, values, and concerns are essential for cultivating community trust and mitigating opposition to larger solar installations [86]. Strategic informational campaigns tailored to local contexts and literacy levels can effectively combat misinformation and cognitive biases, thereby bridging knowledge gaps and promoting widespread adoption.

The study has some limitations despite its relevance and timely contribution. The first limitation is related to the methodology. The qualitative nature of the review limits its findings, which are not informed by quantitative rigor. The codes and themes were manually sorted, organized, and analyzed in an inductive manner to draw results during this review. The quantitative and automated coding and thematic analyses could strengthen the findings through statistical tests and analysis of interconnections of themes and codes. The second limitation is the timeframe of the data for this review. The timeframe of the publication selection is from 2000 to 2024. Based on the authors’ anecdotal observations, there have been multiple groundbreaking publications in the field of energy that have significantly impacted social and public perception, predating 2000. They are not included in this review. The final limitation is the scope of the review. Solar energy perception is practically narrow in scope for the renewable transition for communities, cities, and regions in the United States. Solar is one of the many renewable energy sources that rural and urban communities are investigating for the energy transition. Conducting a comprehensive analytical review of publications focusing on renewable energy alternatives, such as solar, wind, biomass, and geothermal, in the context of both rural and urban areas in the United States, could provide a comprehensive landscape of research in the renewable energy field in the country. Such a review would have higher relevance for renewable energy transition planning at different scales in the United States.

Looking forward, the future of solar energy adoption hinges on the successful integration of technological advancements with social acceptance strategies. Increasing emphasis on community-driven initiatives, such as agrivoltaics and community solar, offers promising avenues for enhancing local benefits and reducing land-use conflicts, particularly in rural areas. Addressing sociopolitical barriers through depoliticized communication strategies that highlight solar energy’s economic and resilience benefits may broaden acceptance across political divides. Ultimately, achieving the full potential of solar energy will require sustained collaborative efforts among researchers, policymakers, and communities to develop adaptable, inclusive, and context-sensitive renewable energy solutions.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/su18010227/s1, Solar Energy_Ghimire, Plange-Rhule, Smith_PRISMA_Checklist_2020_SolarPerception_revision 1. doc

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.G.; methodology, J.G., D.P.-R. and E.S.; software, D.P.-R.; validation, J.G., D.P.-R. and E.S.; formal analysis, D.P.-R. and E.S.; investigation, J.G., D.P.-R., and E.S.; resources, J.G.; data curation, D.P.-R. and E.S.; writing—original draft preparation, J.G. and D.P.-R.; writing—review and editing, J.G. and D.P.-R.; visualization, D.P.-R.; supervision, J.G.; project administration, J.G.; funding acquisition, J.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Office of the Vice President of Research (OVPR) at Iowa State University, Research and Innovation Roundtable (RIR): Energy Solutions for Iowa and Beyond (2023-2024).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Boyd, A.D.; Liu, J.; Hmielowski, J.D. Public support for energy portfolios in Canada: How information about cost and national energy portfolios affect perceptions of energy systems. Energy Environ. 2019, 30, 322–340. [Google Scholar]

- Carlisle, J.E.; Kane, S.L.; Solan, D.; Bowman, M.; Joe, J.C. Public attitudes regarding large-scale solar energy development in the U.S. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 48, 835–847. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, E.M. Diffusion of Innovations, 5th ed.; The Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Boudet, H.S. Public perceptions of and responses to new energy technologies. Nat. Energy 2019, 4, 446–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowe, J.A. The Effect of Partisan Cues on Support for Solar and Wind Energy in the United States. Soc. Sci. Q. 2020, 101, 1461–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graff, M.; Carley, S.; Konisky, D.M. Stakeholder perceptions of the United States energy transition: Local-level dynamics and community responses to national politics and policy. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2018, 43, 144–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajibade, I.; Boateng, G.O. Predicting why people engage in pro-sustainable behaviors in Portland Oregon: The role of environmental self-identity, personal norm, and socio-demographics. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 289, 112538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, V.; Beck, A.L. Public perceptions and information gaps in solar energy in Texas. Environ. Res. Lett. 2015, 10, 074011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alipour, M.; Salim, H.; Stewart, R.A.; Sahin, O. Predictors, taxonomy of predictors, and correlations of predictors with the decision behaviour of residential solar photovoltaics adoption: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2020, 123, 109749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assefa, G.; Frostell, B. Social sustainability and social acceptance in technology assessment: A case study of energy technologies. Technol. Soc. 2007, 29, 63–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Rocco, A.R.; Trovato, M.R.; Caponetto, R.G.; Nocera, F. Energy Poverty and Territorial Resilience: An Integrative Review and an Inclusive Governance Model. Sustainability 2025, 17, 8555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliva, E.J.D.; Atehortua Santamaria, R. Decoding Solar Adoption: A Systematic Review of Theories and Factors of Photovoltaic Technology Adoption in Households of Developing Countries. Sustainability 2025, 17, 5494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sovacool, B.K.; Linnér, B.-O.; Goodsite, M.E. The political economy of climate adaptation. Nat. Clim. Change 2015, 5, 616–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gough, D.; Thomas, J.; Oliver, S. An Introduction to Systematic Reviews; Sage Publication: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Grant, M.J.; Booth, A. A typology of reviews: An analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Inf. Libr. J. 2009, 26, 91–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boudet, H.; Zanocco, C.; Stelmach, G.; Muttaqee, M.; Flora, J. Public preferences for five electricity grid decarbonization policies in California. Rev. Policy Res. 2021, 38, 510–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, O.; Florkowski, W.J.; Us, A.; Klepacka, A.M. Renewable energy perception by rural residents of a peripheral EU region. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowe, J.A.; Li, R. Is the just transition socially accepted? Energy history, place, and support for coal and solar in Illinois, Texas, and Vermont. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2020, 59, 101309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saldana, J. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers, 2nd ed.; Sage: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bukar, U.A.; Sayeed, M.S.; Razak, S.F.A.; Yogarayan, S.; Amodu, O.A.; Mahmood, R.A.R. A method for analyzing text using VOSviewer. MethodsX 2023, 11, 102339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nugroho, A.T.; Hadi, S.P.; Sutanta, H.; Ajrin, H.A. Optimising agrivoltaic systems: Identifying suitable solar development sites for integrated food and energy production. J. Power Energy Control 2024, 1, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Li, W.; Haq, S.U.; Shahbaz, P. Adoption of renewable energy technology on farms for sustainable and efficient production: Exploring the role of entrepreneurial orientation, farmer perception and government policies. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carley, S.; Konisky, D.M.; Atiq, Z.; Land, N. Energy infrastructure, NIMBYism, and public opinion: A systematic literature review of three decades of empirical survey literature. Environ. Res. Lett. 2020, 15, 093007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juntunen, J.K.; Martiskainen, M. Improving understanding of energy autonomy: A systematic review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 141, 110797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolske, K.S.; Gillingham, K.T.; Schultz, P.W. Peer influence on household energy behaviours. Nat. Energy 2020, 5, 202–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bollinger, B.; Gillingham, K. Peer effects in the diffusion of solar photovoltaic panels. Mark. Sci. 2012, 31, 900–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, C.; Dowlatabadi, H. Models of decision making and residential energy use. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2007, 32, 169–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drury, E.; Miller, M.; Macal, C.M.; Graziano, D.J.; Heimiller, D.; Ozik, J.; Perry, T.D., IV. The transformation of southern California’s residential photovoltaics market through third-party ownership. Energy Policy 2012, 42, 681–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunter, D.A.; Castellanos, S.; Kammen, D.M. Disparities in rooftop photovoltaics deployment in the United States by race and ethnicity. Nat. Sustain. 2019, 2, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stokes, L.C.; Warshaw, C. Renewable energy policy design and framing influence public support in the United States. Nat. Energy 2017, 2, 17107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crago, C.L.; Chernyakhovskiy, I. Are policy incentives for solar power effective? Evidence from residential installations in the Northeast. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2017, 81, 132–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlisle, J.E.; Solan, D.; Kane, S.L.; Joe, J. Utility-scale solar and public attitudes toward siting: A critical examination of proximity. Land Use Policy 2016, 58, 491–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barron-Gafford, G.A.; Pavao-Zuckerman, M.A.; Minor, R.L.; Sutter, L.F.; Barnett-Moreno, I.; Blackett, D.T.; Thompson, M.; Dimond, K.; Gerlak, A.K.; Nabhan, G.P. Agrivoltaics provide mutual benefits across the food–energy–water nexus in drylands. Nat. Sustain. 2019, 2, 848–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jager, W. Stimulating the diffusion of photovoltaic systems: A behavioural perspective. Energy Policy 2006, 34, 1935–1943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palm, J.; Tengvard, M. Motives for and barriers to household adoption of small-scale production of electricity: Examples from Sweden. Sustain. Sci. Pract. Policy 2011, 7, 6–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ter-Mkrtchyan, A.; Wehde, W.; Gupta, K.; Jenkins-Smith, H.C.; Ripberger, J.T.; Silva, C.L. Portions in portfolios: Understanding public preferences for electricity production using compositional survey data in the United States. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2022, 91, 102759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwan, C.L. Influence of local environmental, social, economic and political variables on the spatial distribution of residential solar PV arrays across the United States. Energy Policy 2012, 47, 332–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, N. Public perceptions towards adoption of residential Solar Water Heaters in USA: A case study of Phoenicians in Arizona. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 320, 128891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horne, C.; Kennedy, E.H.; Familia, T. Rooftop solar in the United States: Exploring trust, utility perceptions, and adoption among California homeowners. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2021, 82, 102308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, J.; Bessette, D.; Mills, S.B. Rallying the anti-crowd: Organized opposition, democratic deficit, and a potential social gap in large-scale solar energy. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2022, 90, 102597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adesanya, A.A. Can Michigan’s upper peninsula achieve justice in transitioning to 100% renewable electricity? Survey of public perceptions in sociotechnical change. Sustainability 2021, 13, 431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunreuther, H.; Polise, A.; Spellmeyer, Q. Addressing Biases that impact homeowners’ adoption of solar panels. Clim. Policy 2022, 22, 993–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. Perceived behavioral control, self-efficacy, locus of control, and the theory of planned behavior 1. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 32, 665–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arshad, N.S.M.; Abd Razak, S.F.F.; Razak, M.Z.A.; Muslim, N.A.; Manaf, N.A.; Nawang, D.; Azman, F.; Zamri, I.S.M. Willingness to Utilise Solar Energy in Malaysia: A Case of Gen-Z. Glob. Bus. Manag. Res. 2021, 13, 179–191. [Google Scholar]

- Kc, R.; Föhr, J.; Ranta, T. Public Perception on the Sustainable Energy Transition in Rural Finland: A Multi-criteria Approach. Circ. Econ. Sustain. 2023, 3, 735–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goedkoop, F.; Devine-Wright, P. Partnership or placation? The role of trust and justice in the shared ownership of renewable energy projects. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2016, 17, 135–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urpelainen, J. Energy poverty and perceptions of solar power in marginalized communities: Survey evidence from Uttar Pradesh, India. Renew. Energy 2016, 85, 534–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharpton, T.; Lawrence, T.; Hall, M. Drivers and barriers to public acceptance of future energy sources and grid expansion in the United States. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2020, 126, 109826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Sims, C.; Chen, C.-F.; Holladay, J.S.; Jones, G.; Roberson, T. Looking High and Low: Incentive Policies and Residential Solar Adoption in High- and Low-Income U.S. Communities. Energies 2024, 17, 4538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundaram, A.; Gonçalves, J.; Ghorbani, A.; Verma, T. Network dynamics of solar PV adoption: Reconsidering flat tax-credits and influencer seeding for inclusive renewable energy access in Albany county, New York. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2024, 112, 103518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cha, M.-K.; Struthers, C.L.; Brown, M.A.; Kale, S.; Chapman, O. Toward residential decarbonization: Analyzing social-psychological drivers of household co-adoption of rooftop solar, electric vehicles, and efficient HVAC systems in Georgia, US. Renew. Energy 2024, 226, 120382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uebelhor, E.; Hintz, O.; Mills, S.B.; Randall, A. Utility-Scale Solar in the Great Lakes: Analyzing Community Reactions to Solar Developments. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carley, S.; Konisky, D.M. The justice and equity implications of the clean energy transition. Nat. Energy 2020, 5, 569–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbett, C.J.; Hershfield, H.E.; Kim, H.; Malloy, T.F.; Nyblade, B.; Partie, A. The role of place attachment and environmental attitudes in adoption of rooftop solar. Energy Policy 2022, 162, 112764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoesch, K.W.; Bessette, D.L.; Bednar, D.J. Locally charged: Energy justice outcomes of a low-income community solar project in Michigan. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2024, 113, 103569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torma, G.; Aschemann-Witzel, J. Social acceptance of dual land use approaches: Stakeholders’ perceptions of the drivers and barriers confronting agrivoltaics diffusion. J. Rural. Stud. 2023, 97, 610–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuppari, R.I.; Higgins, C.W.; Characklis, G.W. Agrivoltaics and weather risk: A diversification strategy for landowners. Appl. Energy 2021, 291, 116809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, P.K.; Morgan, W.; Richardson, J. Land Use Conflicts Between Wind and Solar Renewable Energy and Agricultural Uses; The National Agricultural Law Center: Lawrence, KS, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, S.; Graff, H.; Ouellet, C.; Leslie, S.; Olweean, D. Can we have clean energy and grow our crops too? Solar siting on agricultural land in the United States. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2022, 91, 102731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weselek, A.; Bauerle, A.; Hartung, J.; Zikeli, S.; Lewandowski, I.; Högy, P. Agrivoltaic system impacts on microclimate and yield of different crops within an organic crop rotation in a temperate climate. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2021, 41, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrett, V.; Koontz, T.M. Breaking the cycle: Producer and consumer perspectives on the non-adoption of passive solar housing in the US. Energy Policy 2008, 36, 1551–1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tongsopit, S.; Kittner, N.; Chang, Y.; Aksornkij, A.; Wangjiraniran, W. Energy security in ASEAN: A quantitative approach for sustainable energy policy. Energy Policy 2016, 90, 60–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brungard, E. Voters Are Interested in Rooftop Solar, but See Barriers to Personal Adoption. Available online: https://www.dataforprogress.org/blog/2024/12/9/voters-are-interested-in-rooftop-solar-but-see-barriers-to-personal-adoption (accessed on 16 December 2025).

- Dillman-Hasso, N.H.; Sintov, N.D. Can we achieve equity in residential solar adoption? Public perceptions of rooftop and community solar in the United States. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2025, 122, 104022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]