Agronomic Potential of Pyrochar and Hydrochar from Sewage Sludge: Effects of Carbonization Conditions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Raw Material

2.2. Pyrochar and Hydrochar Production

2.3. Physicochemical Characterization

2.4. Agronomic Properties

- CIC (mg N-NO3− kg−1) is the concentration obtained from ion chromatography,

- Cblank (mg NO3− L−1) is the nitrate concentration measured in the reagent blank,

- Vextract (L) is the extraction solution volume,

- DF is the dilution factor,

- mdry (kg) is the dry-weight equivalent of the sample,

- 14 (mg) is the atomic weight of nitrogen,

- and 62 (mg) is the molecular weight of the nitrate ion (NO3−).

2.5. Data Analysis and Calculations

2.5.1. Yield Calculation

2.5.2. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Pyrochar and Hydrochar Yields

3.2. Physicochemical Characterization

3.2.1. Proximate and Ultimate Analyses

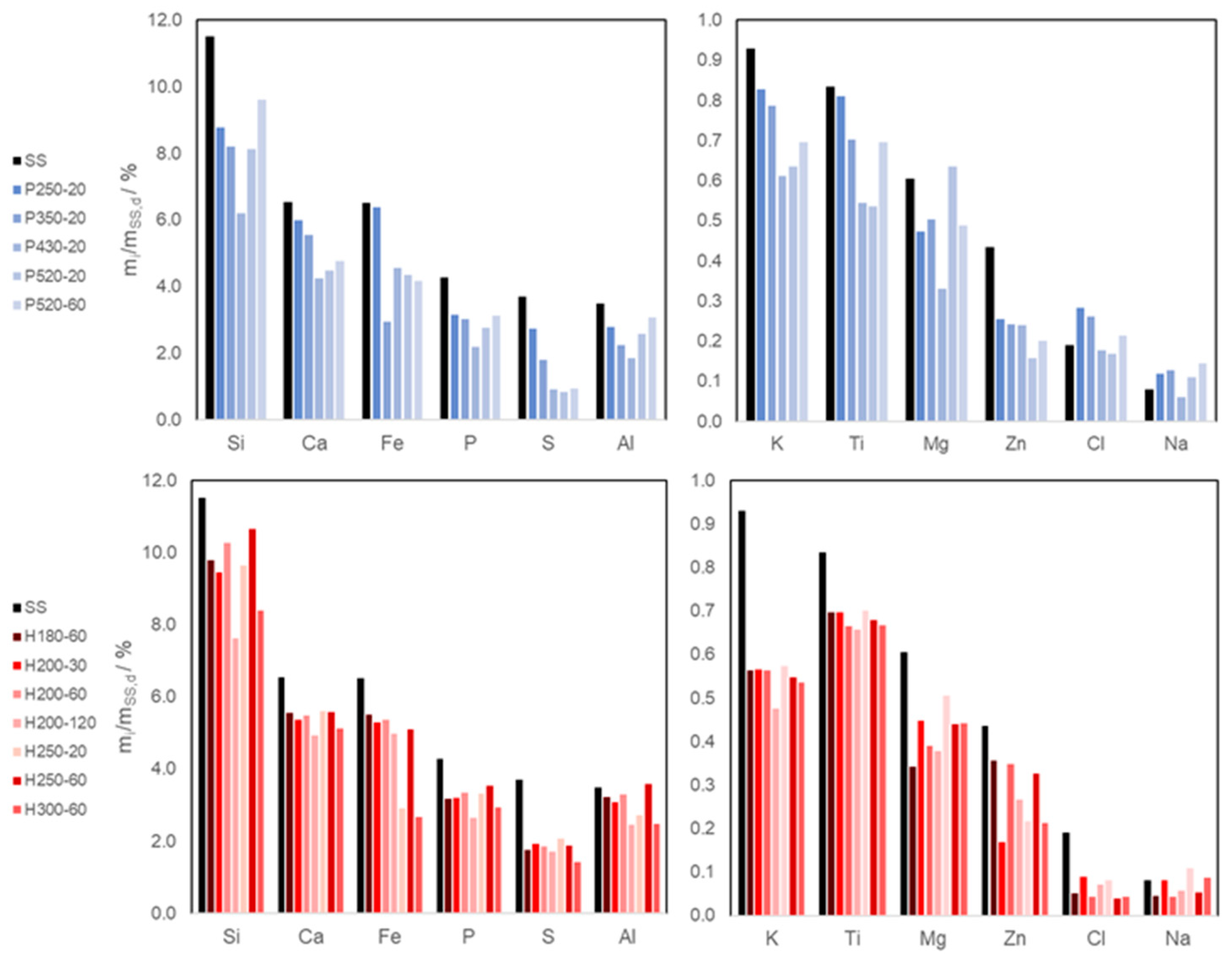

3.2.2. Elemental Composition (XRF Analysis) and Heavy Metal Total Content

3.3. Surface Properties

3.4. Agronomical Properties

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rodriguez, D.J.; Serrano, H.A.; Delgado, A.; Saltiel, D.N.Y.G. From Waste to Resource: Shifting Paradigms for Smarter Wastewater Interventions in Latin America and the Caribbean; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Korhonen, J.; Honkasalo, A.; Seppälä, J. Circular Economy: The Concept and its Limitations. Ecol. Econ. 2018, 143, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhen, G. Chapter One—Sewage Sludge Generation and Characteristics. In de Pollution Control and Resource Recovery for Sewage Sludge; Elsevier Science: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Dong, H.; Wang, Y.; Men, J.; Wang, J.; Zhao, X.; Zou, S. Valorization of Alkali–Thermal Activated Red Mud for High-Performance Geopolymer: Performance Evaluation and Environmental Effects. Buildings 2025, 15, 2471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, A.; Zhang, R.; Ngo, H.H.; He, X.; Ma, J.; Nan, J.; Li, G. Life cycle assessment of sewage sludge treatment and disposal based on nutrient and energy recovery: A review. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 769, 144451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrentino, R.; Langone, M.; Fiori, L.; Andreottola, G. Full-Scale Sewage Sludge Reduction Technologies: A Review with a Focus on Energy Consumption. Water 2023, 15, 615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kominko, H.; Gorazda, K.; Wzorek, Z. Sewage sludge: A review of its risks and circular raw material potential. J. Water Process. Eng. 2024, 63, 105522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.; Tang, Y.; Luo, L. Thermochemistry of sulfur during pyrolysis and hydrothermal carbonization of sewage sludges. Waste Manag. 2021, 121, 276–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rincon, L.S.; Mendoza, Y.A.G. Tratamiento Térmico de Biosólidos Para Aplicaciones Energéticas. Pirólisis y Conversión de Sus alquitranes; Kassel University Press: Kassel, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Mitzia, A.; Hudcová, B.B.; Vítková, M.; Kunteová, B.; Hernandez, D.C.; Moško, J.; Pohořelý, M.; Grasserová, A.; Cajthaml, T.; Komárek, M. Pyrolysed sewage sludge for metal(loid) removal and immobilisation in contrasting soils: Exploring variety of risk elements across contamination levels. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 918, 170572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.K.; Strezov, V.; Chan, K.Y.; Nelson, P.F. Agronomic properties of wastewater sludge biochar and bioavailability of metals in production of cherry tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum). Chemosphere 2010, 78, 1167–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paz-Ferreiro, J.; Fu, S.; Méndez, A.; Gascó, G. Interactive effects of biochar and the earthworm Pontoscolex corethrurus on plant productivity and soil enzyme activities. J. Soils Sediments 2014, 14, 483–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Huang, L.; Chen, Z.; Wen, Z.; Ma, L.; Xu, S.; Wu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Feng, Y. Biochar and its combination with inorganic or organic amendment on growth, uptake and accumulation of cadmium on lettuce. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 370, 133610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Figueiredo, C.C.; Reis, A.d.S.P.J.; de Araujo, A.S.; Blum, L.E.B.; Shah, K.; Paz-Ferreiro, J. Assessing the potential of sewage sludge-derived biochar as a novel phosphorus fertilizer: Influence of extractant solutions and pyrolysis temperatures. Waste Manag. 2021, 124, 144–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanmohammadi, Z.; Afyuni, M.; Mosaddeghi, M.R. Effect of pyrolysis temperature on chemical and physical properties of sewage sludge biochar. Waste Manag. Res. 2015, 33, 275–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Li, Y.; Liu, F.; Zhang, X.; Song, M.; Li, R. Pyrolysis of sewage sludge to biochar: Transformation mechanism of phosphorus. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2023, 173, 106065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Li, M.; Wang, H.; Tan, M.; Zhang, G.; Huang, Z.; Yuan, X. A review on migration and transformation of nitrogen during sewage sludge thermochemical treatment: Focusing on pyrolysis, gasification and combustion. Fuel Process. Technol. 2023, 240, 107562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kossińska, N.; Krzyżyńska, R.; Ghazal, H.; Jouhara, H. Hydrothermal carbonisation of sewage sludge and resulting biofuels as a sustainable energy source. Energy 2023, 275, 127337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathika, K.; Kumar, S.; Yadav, B.R. Enhanced energy and nutrient recovery via hydrothermal carbonisation of sewage sludge: Effect of process parameters. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 906, 167828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stefanelli, E.; Vitolo, S.; Di Fidio, N.; Puccini, M. Tailoring the porosity of chemically activated carbons derived from the HTC treatment of sewage sludge for the removal of pollutants from gaseous and aqueous phases. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 345, 118887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tasca, A.L.; Vitolo, S.; Gori, R.; Mannarino, G.; Galletti, A.M.R.; Puccini, M. Hydrothermal carbonization of digested sewage sludge: The fate of heavy metals, PAHs, PCBs, dioxins and pesticides. Chemosphere 2022, 307, 135997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, R.; Gao, F.; Tan, Y.; Xiong, H.-R.; Xu, Z.-X.; Osman, S.M.; Zheng, L.-J.; Luque, R. Phosphorus species transformation and recovery in deep eutectic solvent-assisted hydrothermal carbonization of sewage sludge. Sustain. Chem. Pharm. 2024, 37, 101408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Hu, G.; Basar, I.A.; Li, J.; Lyczko, N.; Nzihou, A.; Eskicioglu, C. Phosphorus recovery from municipal sludge-derived ash and hydrochar through wet-chemical technology: A review towards sustainable waste management. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 417, 129300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Tian, L.; Liu, T.; Liu, Z.; Huang, Z.; Yang, H.; Tian, L.; Huang, Q.; Li, W.; Gao, Y.; et al. Speciation and transformation of nitrogen for sewage sludge hydrothermal carbonization-influence of temperature and carbonization time. Waste Manag. 2013, 162, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhuang, X.; Huang, Y.; Song, Y.; Zhan, H.; Yin, X.; Wu, C. The transformation pathways of nitrogen in sewage sludge during hydrothermal treatment. Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 245, 463–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Chen, M.; Yang, T.; Liu, Z.; Jiao, W.; Li, D.; Gai, C. Gasification performance of the hydrochar derived from co-hydrothermal carbonization of sewage sludge and sawdust. Energy 2019, 173, 732–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Huang, J.; Hu, W.; Xie, D.; Xu, M.; Qiao, Y. In-depth study of the sulfur migration and transformation during hydrothermal carbonization of sewage sludge. Proc. Combust. Inst. 2023, 39, 3419–3427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gwenzi, W.; Muzava, M.; Mapanda, F.; Tauro, T.P. Comparative short-term effects of sewage sludge and its biochar on soil properties, maize growth and uptake of nutrients on a tropical clay soil in Zimbabwe. J. Integr. Agric. 2016, 15, 1395–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueiredo, C.; Lopes, H.; Coser, T.; Vale, A.; Busato, J.; Aguiar, N.; Novotny, E.; Canellas, L. Influence of pyrolysis temperature on chemical and physical properties of biochar from sewage sludge. Arch. Agron. Soil Sci. 2017, 64, 881–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez, W.A.; Klose, Y.S.R. Pirólisis de Biomasa. Cuesco de Palmade Aceite; Kassel University Press: Kassel, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Talero, G.; Rincón, S.; Gómez, A. Biomass torrefaction in a standard retort: A study on oil palm solid residues. Fuel 2019, 244, 366–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 647; Brown Coals and Lignites—Determination of the Yields of Tar, Water, Gas and Coke Residue by Low Temperature Distillation. ISO—International Organization for Standardization: Geneve, Switzerland, 1974.

- ISO 18134-1:2022; Solid Biofuels—Determination of Moisture Content. ISO—International Organization for Standardization: Geneve, Switzerland, 2022.

- ISO 18122-1:2022; Solid Biofuels—Determination of Ash Content. ISO—International Organization for Standardization: Geneve, Switzerland, 2022.

- ISO 18123-1:2023; Solid Biofuels—Determination of Volatile Matter. ISO—International Organization for Standardization: Geneve, Switzerland, 2023.

- Mimura, T.; Reid, R. Phosphate environment and phosphate uptake studies: Past and future. J. Plant Res. 2024, 137, 307–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amadou, I.; Faucon, M.-P.; Houben, D. Role of soil minerals on organic phosphorus availability and phosphorus uptake by plants. Geoderma 2022, 428, 116125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayan, O.P.; Kumar, P.; Yadav, B.; Dua, M.; Johri, A.K. Sulfur nutrition and its role in plant growth and development. Plant Signal. Behav. 2023, 18, 2030082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Geografico Agustin Codazzi (IGAC). Métodos Analíticos del Laboratorio de Suelos, 6th ed.; IGAC, Imprenta Nacional de Colombia: Bogotá, Colombia, 2006.

- Gonzaga, M.I.S.; Mackowiak, C.L.; Comerford, N.B.; Moline, E.F.d.V.; Shirley, J.P.; Guimaraes, D.V. Pyrolysis methods impact biosolids-derived biochar composition, maize growth and nutrition. Soil Tillage Res. 2017, 165, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 10304-1:2022; Water Quality—Determination of Dissolved Anions by Liquid Chromatography of Ions—Part 1: Determination of Bromide, Chloride, Fluoride, Nitrate, Nitrite, Phosphate and Sulfate. ISO—International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022.

- JCGM 104:2009; Evaluation of Measurement Data—An Introduction to the “Guide to the Expression of Uncertainty in Measurement” and Related Documents. Joint Committee for Guides in Metrology—JCGM: Sèvres, France, 2009.

- Mendoza-Geney, L.; Prat, S.R.; Gómez, A. A comprehensive study of the high temperature pyrolysis of sewage sludge: Kinetics, energy analysis and products formation. Glob. Nest J. 2024, 24, 16–28. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Lu, P.; Chen, D.; Song, T. Effect of operation conditions on fuel characteristics of hydrochar via hydrothermal carbonization of agroforestry biomass. Biomass Conv. Bioref. 2023, 13, 11891–11903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libra, J.A.; Ro, K.S.; Kammann, C.; Funke, A.; Berge, N.D.; Neubauer, Y.; Titirici, M.-M.; Fühner, C.; Bens, O.; Kern, J.; et al. Hydrothermal carbonization of biomass residuals: A comparative review of the chemistry, processes and applications of wet and dry pyrolysis. Biofuels 2011, 2, 71–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, P.; Kaushal, P. Chapter 4—Biomass characteristics. In de Biomass Gasification, Pyrolysis, and Torrefaction, 4th ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2024; pp. 63–105. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, H.; Lu, T.; Huang, H.; Zhao, D.; Kobayashi, N.; Chen, Y. Influence of pyrolysis temperature on physical and chemical properties of biochar made from sewage sludge. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2015, 112, 284–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, Y.-H.; Zhao, D.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, W.; Tang, Y.-Y.; Huang, X.; Wu, Q.; Wang, Y.-X.; Xiao, T.; Liu, C. Feasibility of sewage sludge derived hydrochars for agricultural application: Nutrients (N, P, K) and potentially toxic elements (Zn, Cu, Pb, Ni, Cd). Chemosphere 2019, 236, 124841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiedemeier, D.B.; Abiven, S.; Hockaday, W.C.; Keiluweit, M.; Kleber, M.; Masiello, C.A.; McBeath, A.V.; Nico, P.S.; Pyle, L.A.; Schneider, M.P.; et al. Aromaticity and degree of aromatic condensation of char. Org. Geochem 2015, 78, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Sun, K.; Han, L.; Chen, Y.; Liu, J.; Xing, B. Biochar stability and impact on soil organic carbon mineralization depend on biochar processing, aging and soil clay content. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2022, 169, 108657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun, Y.; Shen, G.; Chiou, K.T.; Xing, B. Compositions and sorptive properties of crop residue-derived chars. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2004, 38, 4649–4655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.-E.; Kim, I.-T.; Yoo, Y.-S. Stabilization of High-Organic-Content Water Treatment Sludge by Pyrolysis. Energies 2018, 11, 3292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilk, M.; Czerwińska, K.; Śliz, M.; Imbierowicz, M. Hydrothermal carbonization of sewage sludge: Hydrochar properties and processing water treatment by distillation and wet oxidation. Energy Rep. 2023, 9, 39–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hämäläinen, A.; Kokko, M.; Kinnunen, V.; Hilli, T.; Rintala, J. Hydrothermal carbonisation of mechanically dewatered digested sewage sludge—Energy and nutrient recovery in centralised biogas plant. Water Res. 2021, 201, 117284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Řimnáčová, D.; Bičáková, O.; Moško, J.; Straka, P.; Čimová, N. The effect of carbonization temperature on textural properties of sewage sludge-derived biochars as potential adsorbents. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 359, 120947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Fu, X.; Wang, J.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, W.; Memon, A.G.; Zhang, H.; Wen, Y. Characteristics of advanced anaerobic digestion sludge-based biochar and its application for sewage sludge conditioning. Bioresour. Technol. 2024, 402, 130833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Wang, B.; Guo, Y.; Yang, F.; Cheng, F. Insights into the structure evolution of sewage sludge during hydrothermal carbonization under different temperatures. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2023, 169, 105839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.K.; Strezov, V.; Chan, K.Y.; Ziolkowski, A.; Nelson, P.F. Influence of pyrolysis temperature on production and nutrient properties of wastewater sludge biochar. J. Environ. Manag. 2011, 92, 223–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Xue, X.; Chen, D.; He, P.; Dai, X. Application of biochar from sewage sludge to plant cultivation: Influence of pyrolysis temperature and biochar-to-soil ratio on yield and heavy metal accumulation. Chemosphere 2014, 109, 213–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zielińska, A.; Oleszczuk, P. The conversion of sewage sludge into biochar reduces polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon content and ecotoxicity but increases trace metal content. Biomass Bioenergy 2015, 75, 235–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Lee, K.; Park, K.Y. Hydrothermal carbonization of anaerobically digested sludge for solid fuel production and energy recovery. Fuel 2014, 130, 120–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roslan, S.Z.; Zainudin, S.F.; Aris, A.M.; Chin, K.B.; Musa, M.; Daud, A.R.M.; Hassan, S.S.A.S. Hydrothermal Carbonization of Sewage Sludge into Solid Biofuel: Influences of Process Conditions on the Energetic Properties of Hydrochar. Energies 2023, 16, 2483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, D.A.; Cole, A.J.; Whelan, A.; de Nys, R.; Paul, N.A. Slow pyrolysis enhances the recovery and reuse of phosphorus and reduces metal leaching from biosolids. Waste Manag. 2017, 64, 133–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Sample | Yield yd/wt.% | Proximate Analysis/wt.% | Ultimate Analysis/wt.% | SBET,d /m2·g−1 | SBJH,d /m2·g−1 | Vp,d /cm3·g−1 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ad | Vd | Cfix 1 | Cd | Hd | Nd | Sd | Od 1 | |||||

| SS | 100 | 41.82 ± 0.12 | 51.94 ± 0.22 | 6.23 ± 0.25 | 32.02 ± 0.39 | 4.10 ± 0.12 | 5.52 ± 0.14 | 1.19 ± 0.02 | 15.35 ± 0.45 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

| H180-60 | 74.22 ± 0.36 | 55.12 ± 0.07 | 39.99 ± 0.04 | 4.89 ± 0.08 | 27.11 ± 0.64 | 3.66 ± 0.05 | 3.82 ± 0.64 | 1.02 ± 0.02 | 9.28 ± 0.91 | 14.7 | 11.7 | 0.0156 |

| H200-30 | 73.29 ± 1.31 | 56.41 ± 0.40 | 38.76 ± 0.64 | 4.83 ± 0.75 | 27.45 ± 1.41 | 3.61 ± 0.20 | 2.33 ± 0.19 | 1.05 ± 0.09 | 9.15 ± 1.49 | 86.0 | 67.6 | 0.0793 |

| H200-60 | 72.33 ± 1.69 | 56.80 ± 0.39 | 38.25 ± 0.05 | 4.95 ± 0.39 | 27.03 ± 1.30 | 3.55 ± 0.16 | 3.21 ± 0.09 | 1.12 ± 0.17 | 8.29 ± 1.38 | 39.8 | 34.8 | 0.0458 |

| H200-120 | 69.99 ± 1.01 | 58.05 ± 0.14 | 36.59 ± 0.41 | 5.36 ± 0.43 | 26.24 ± 0.87 | 3.38 ± 0.13 | 2.00 ± 0.07 | 0.98 ± 0.03 | 9.35 ± 0.89 | 60.1 | 19.1 | 0.0234 |

| H250-20 | 67.46 ± 0.66 | 58.02 ± 0.21 | 34.75 ± 0.42 | 7.24 ± 0.47 | 27.87 ± 0.09 | 3.37 ± 0.01 | 2.30 ± 0.01 | 0.94 ± 0.00 | 7.50 ± 0.23 | - | - | - |

| H250-60 | 66.64 ± 0.72 | 62.71 ± 0.40 | 32.04 ± 0.64 | 5.25 ± 0.75 | 25.22 ± 1.13 | 3.03 ± 0.19 | 2.62 ± 0.69 | 0.92 ± 0.05 | 5.49 ± 1.40 | 96.5 | 79.2 | 0.0886 |

| H300-60 | 62.26 ± 0.38 | 63.23 ± 0.20 | 30.56 ± 0.30 | 6.21 ± 0.36 | 24.59 ± 0.03 | 2.95 ± 0.01 | 1.74 ± 0.01 | 0.78 ± 0.00 | 6.72 ± 0.20 | - | - | - |

| P250-20 | 91.04 ± 0.15 | 43.79 ± 0.06 | 46.98 ± 0.06 | 9.23 ± 0.08 | 32.97 ± 0.14 | 3.94 ± 0.02 | 4.99 ± 0.02 | 1.18 ± 0.00 | 13.13 ± 0.15 | 12.7 | 10.4 | 0.0132 |

| P350-20 | 70.89 ± 0.10 | 59.00 ± 0.07 | 28.21 ± 0.19 | 12.78 ± 0.20 | 29.17 ± 0.04 | 2.63 ± 0.01 | 3.97 ± 0.01 | 0.93 ± 0.00 | 4.29 ± 0.08 | 20.1 | 20.2 | 0.0257 |

| P430-20 | 61.20 ± 0.43 | 65.75 ± 0.07 | 17.56 ± 0.09 | 16.68 ± 0.11 | 25.12 ± 0.04 | 1.70 ± 0.01 | 3.38 ± 0.01 | 0.79 ± 0.00 | 3.26 ± 0.08 | 38.4 | 31.8 | 0.0426 |

| P520-20 | 58.21 ± 0.30 | 70.65 ± 0.07 | 12.38 ± 0.07 | 16.97 ± 0.10 | 24.25 ± 0.05 | 1.33 ± 0.01 | 3.03 ± 0.01 | 0.69 ± 0.00 | 0.05 ± 0.09 | 33.6 | 34.7 | 0.0343 |

| P520-60 | 57.51 ± 0.43 | 70.27 ± 0.15 | 11.10 ± 0.14 | 18.64 ± 0.21 | 24.50 ± 0.07 | 1.03 ± 0.01 | 3.17 ± 0.02 | 0.65 ± 0.00 | 0.38 ± 0.17 | 12.7 | 12.1 | 0.0123 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Mendoza-Geney, L.; Fonseca, S.; Bermudez-Aguilar, F.; Martinez-Cordón, M.; Gómez-Mejía, A.; Rincón-Prat, S. Agronomic Potential of Pyrochar and Hydrochar from Sewage Sludge: Effects of Carbonization Conditions. Sustainability 2026, 18, 223. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010223

Mendoza-Geney L, Fonseca S, Bermudez-Aguilar F, Martinez-Cordón M, Gómez-Mejía A, Rincón-Prat S. Agronomic Potential of Pyrochar and Hydrochar from Sewage Sludge: Effects of Carbonization Conditions. Sustainability. 2026; 18(1):223. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010223

Chicago/Turabian StyleMendoza-Geney, Libardo, Santiago Fonseca, Fredy Bermudez-Aguilar, María Martinez-Cordón, Alexánder Gómez-Mejía, and Sonia Rincón-Prat. 2026. "Agronomic Potential of Pyrochar and Hydrochar from Sewage Sludge: Effects of Carbonization Conditions" Sustainability 18, no. 1: 223. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010223

APA StyleMendoza-Geney, L., Fonseca, S., Bermudez-Aguilar, F., Martinez-Cordón, M., Gómez-Mejía, A., & Rincón-Prat, S. (2026). Agronomic Potential of Pyrochar and Hydrochar from Sewage Sludge: Effects of Carbonization Conditions. Sustainability, 18(1), 223. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010223