The Impact of GAPPs on the Production Efficiency of Family Farms

Abstract

1. Introduction

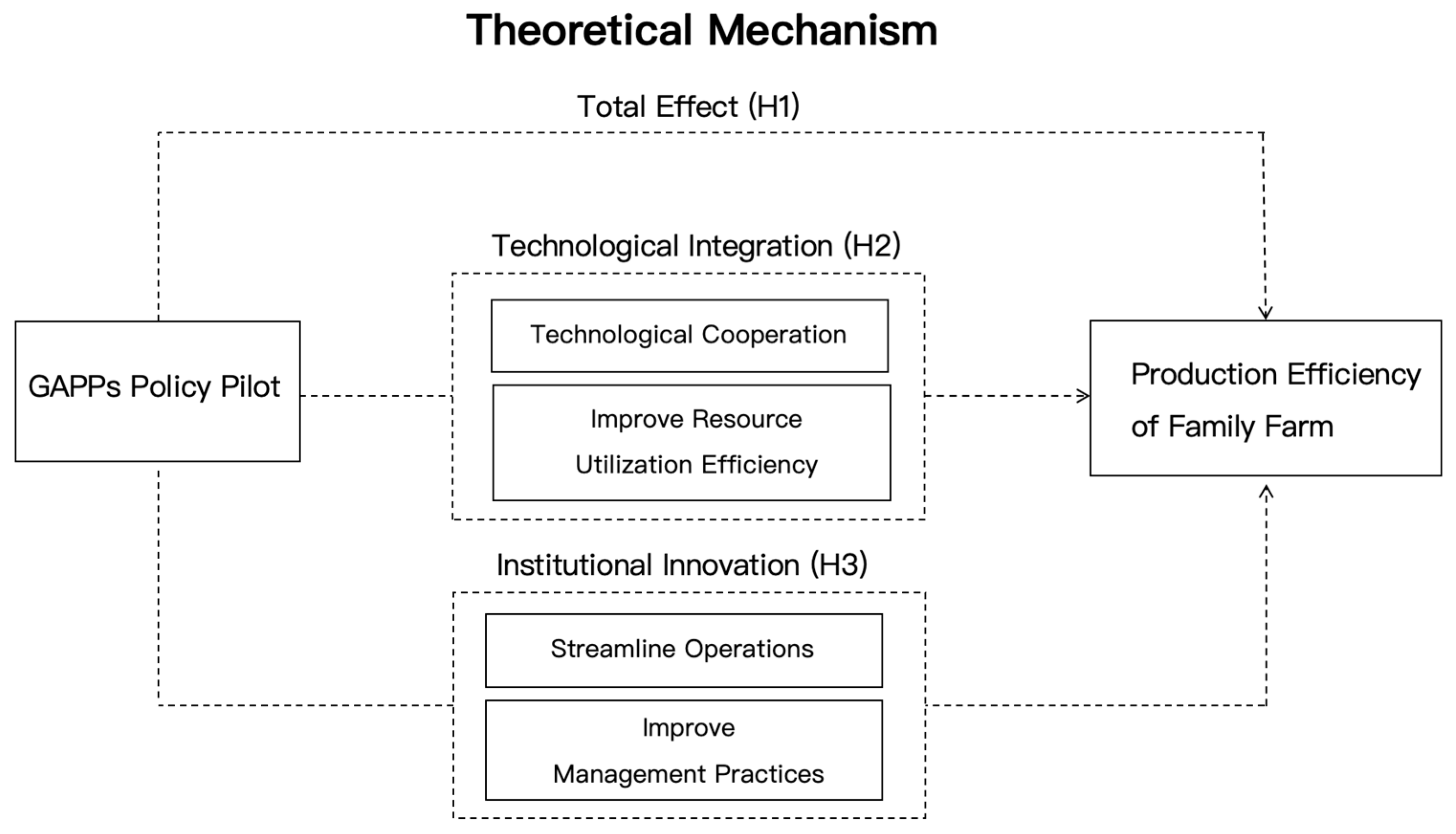

2. Theoretical Analysis Framework and Research Hypotheses

2.1. Establishment of GAPPs and Family Farm Production Efficiency

2.2. Green Technology Integration and Family Farm Production Efficiency

2.3. Green Institutional Innovation and Family Farm Production Efficiency

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Data Sources

3.2. Model Setting

3.2.1. Model for Measuring the Production Efficiency of Family Farms

3.2.2. Estimation Model of Efficiency-Influencing Factors

3.3. Variable Selection

4. Empirical Results and Analysis

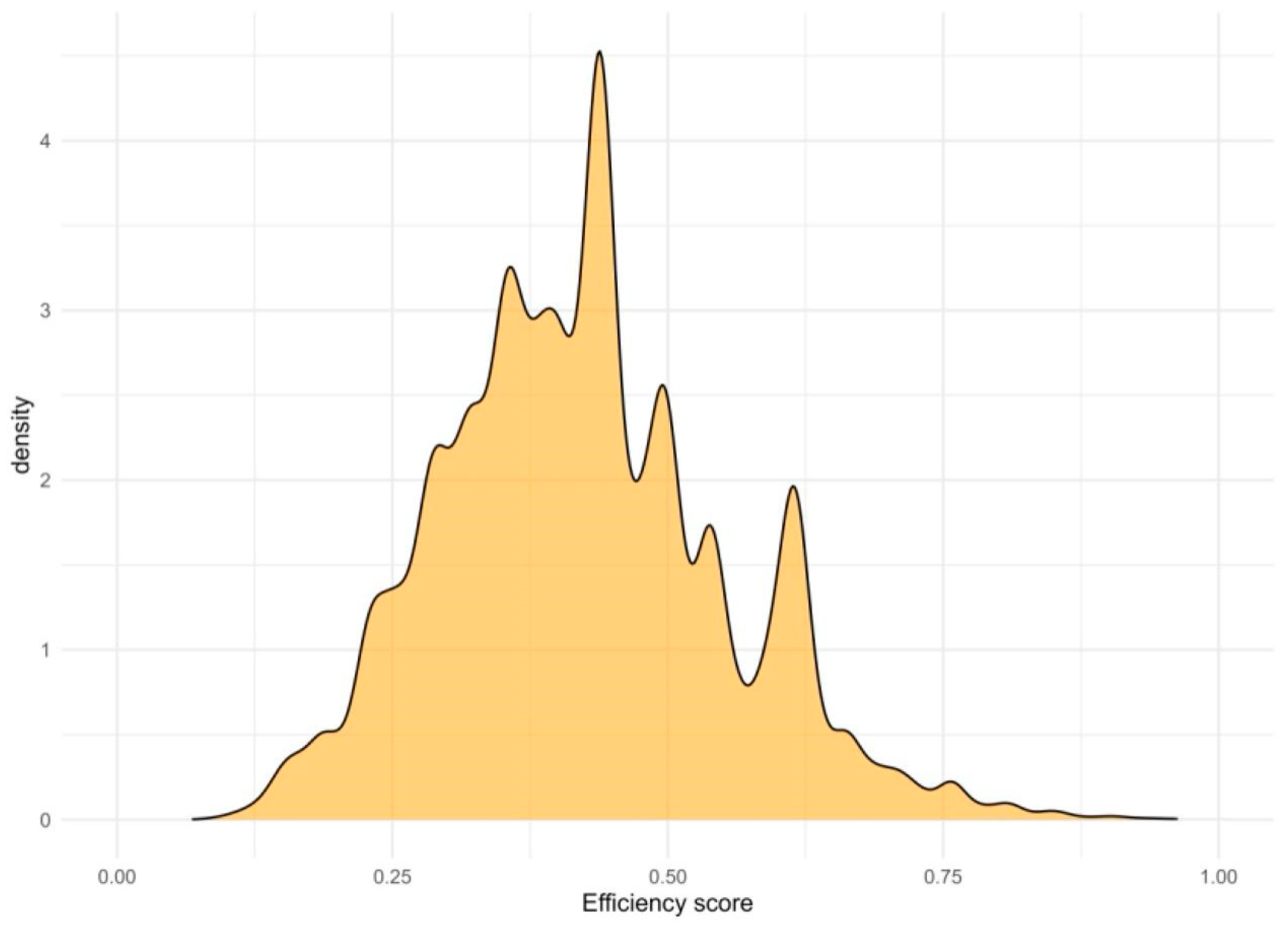

4.1. Distribution Characteristics of Family Farm Production Efficiency

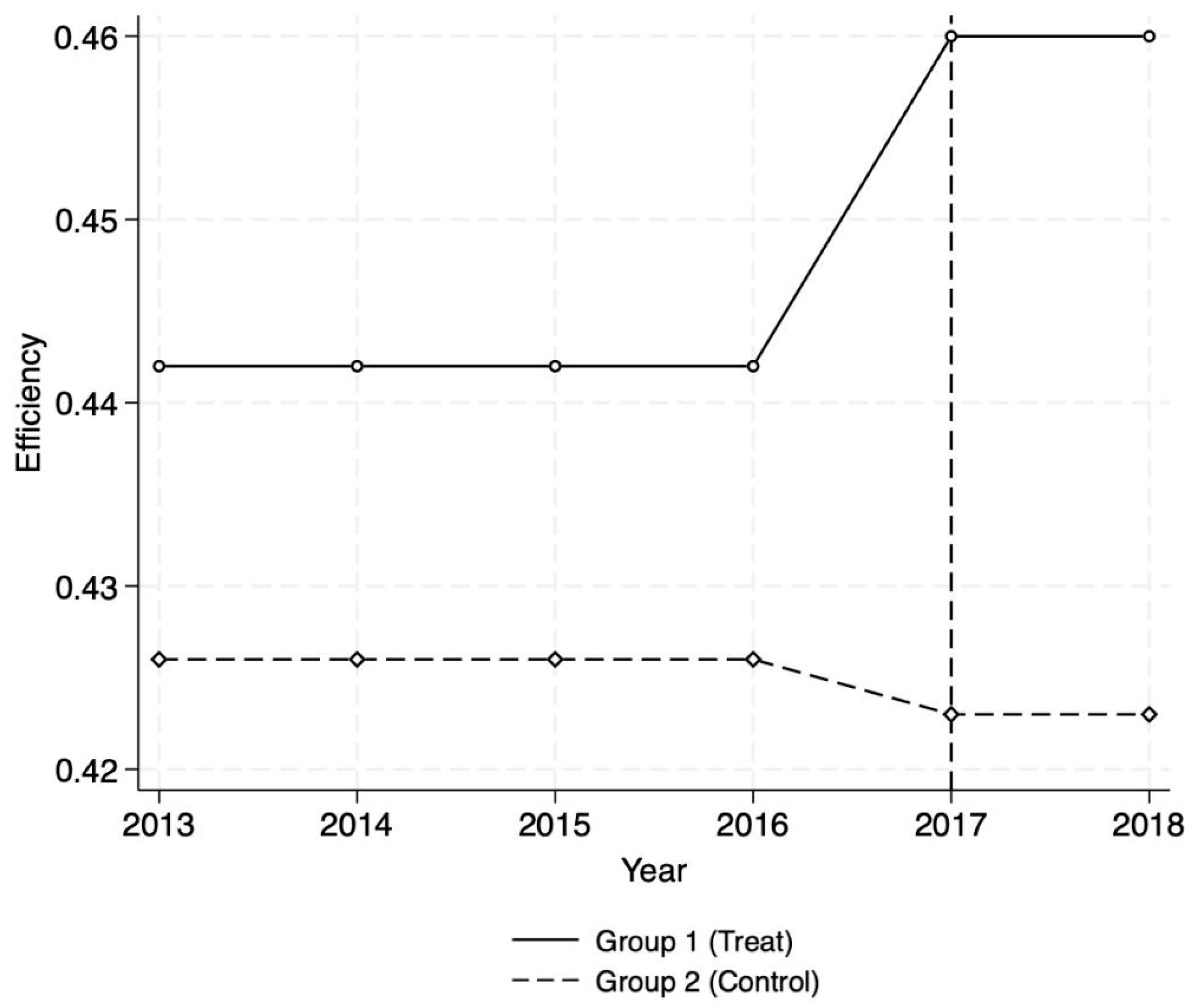

4.2. Benchmark Regression Results

4.3. Robustness Test

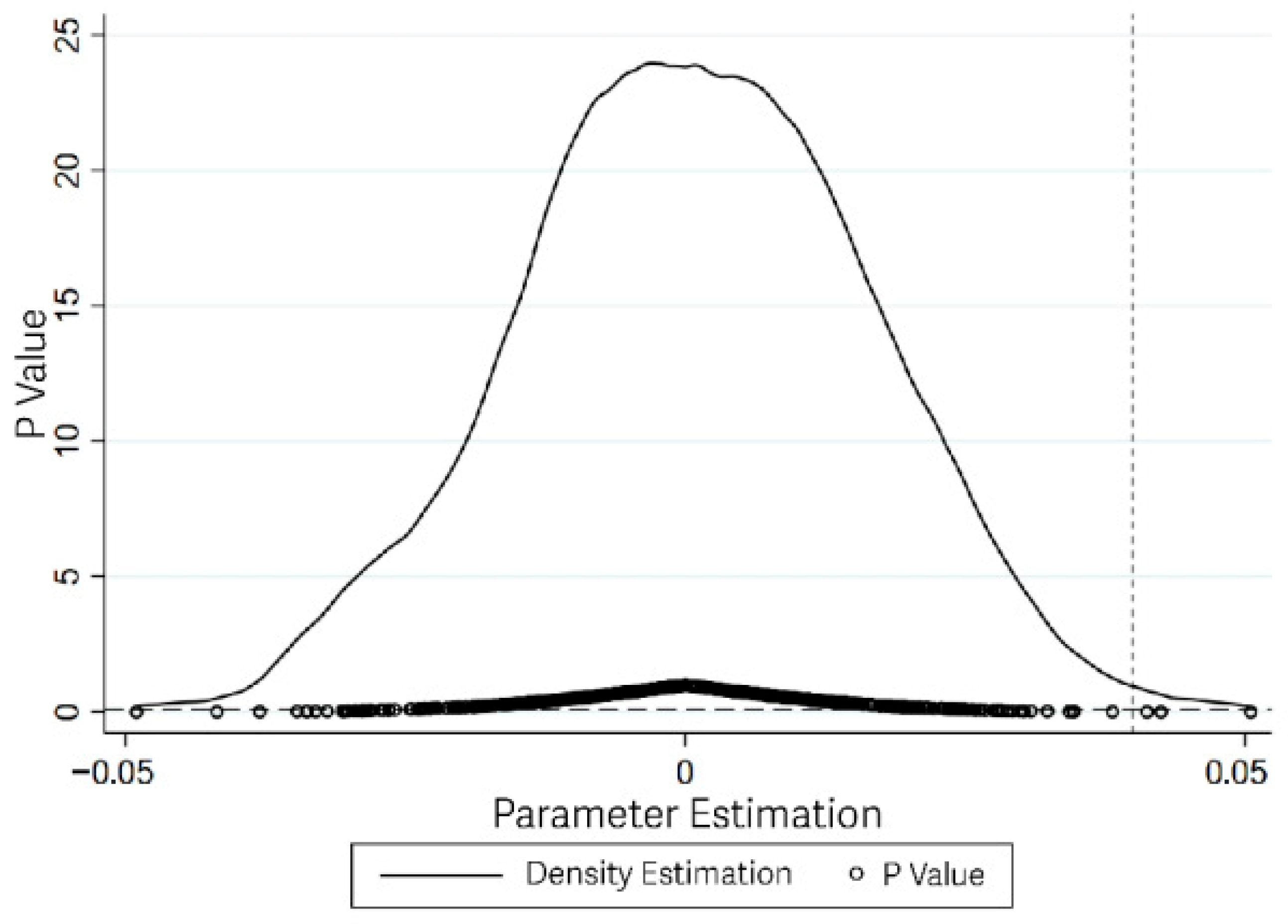

4.4. Placebo Test

4.5. Heterogeneity Test

5. Mechanism of Action Analysis

6. Conclusions and Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chandio, A.A.; Akram, W.; Du, A.M.; Ahmad, F.; Tang, X. Agricultural transformation: Exploring the impact of digitalization, technological innovation and climate change on food production. Res. Int. Bus. Financ. 2025, 75, 102755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marandola, D.; Belliggiano, A.; Romagnoli, L.; Ievoli, C. The spread of no-till in conservation agriculture systems in Italy: Indications for rural development policy-making. Agric. Food Econ. 2019, 7, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Jiang, J.; Du, J. The dual effects of environmental regulation and financial support for agriculture on agricultural green development: Spatial spillover effects and spatio-temporal heterogeneity. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 11609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perlatti, B.; Forim, M.R.; Zuin, V.G. Green chemistry, sustainable agriculture and processing systems: A Brazilian overview. Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric. 2014, 1, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, F.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, J.; Liu, Y.; Chen, Y. Nonlinear impact of the coordination of IFDI and OFDI on green total factor productivity in the context of “Dual Circulation”. Financ. Innov. 2025, 11, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, Z.; Wang, M.; Liu, T.; Cao, G. Does the Different Recipients of Land Fertility Protection Subsidy Influence the Scale and Efficiency of Village Land Circulation? Evidence from a Chinese Agricultural City. Agric. Rural Stud. 2025, 3, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L. Big hands holding small hands: The role of new agricultural operating entities in farmland abandonment. Food Policy 2024, 123, 102605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karbo, R.; Frewer, L.; Areal, F.J.; Boaitey, A.; Jones, G.; Garrod, G. Investigating Farmers’ Intention to Adopt Renewable Energy Technology for Farming: Determinants of Decision Making in Northern Ghana. Agric. Rural Stud. 2025, 3, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, S.; Zhu, Y.; Fang, X. Big Food Vision and Food Security in China. Agric. Rural Stud. 2023, 1, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Lin, Q. Threshold effects of green technology application on sustainable grain production: Evidence from China. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1107970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Wang, X.; Yi, X.; Hu, L. The impact of farmers’ participation in green cooperative production on green performance—A study based on the moderating effect of environmental regulation. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 16733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogliotti, S.; García, M.C.; Peluffo, S.; Dieste, J.P.; Pedemonte, A.J.; Bacigalupe, G.F.; Rossing, W.A.H. Co-innovation of family farm systems: A systems approach to sustainable agriculture. Agric. Syst. 2014, 126, 76–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, N.; Yang, X.; Shadbolt, N. The balanced scorecard as a tool evaluating the sustainable performance of Chinese emerging family farms—Evidence from Jilin province in China. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tirkaso, W.; Hailu, A. Does neighborhood matter? Spatial proximity and farmers’ technical efficiency. Agric. Econ. 2022, 53, 374–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, C.; Liu, S.; Van Grinsven, H.; Reis, S.; Jin, S.; Liu, H.; Gu, B. The impact of farm size on agricultural sustainability. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 220, 357–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Wang, T.; Li, N. Reciprocal and Symbiotic: Family Farms’ Operational Performance and Long-Term Cooperation of Entities in the Agricultural Industrial Chain—From the Evidence of Xinjiang in China. Sustainability 2022, 15, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornasin, A.; Breschi, M.; Manfredini, M. Peasant families and farm size in Fascist Italy. Genus 2024, 80, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yunis, M.; Tarhini, A.; Kassar, A. The role of ICT and innovation in enhancing organizational performance: The catalysing effect of corporate entrepreneurship. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 88, 344–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, K.E.; Wu, J.H.; Lu, S.Y.; Lin, Y.C. Innovation and technology creation effects on organizational performance. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 2187–2192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iansiti, M. Technology integration: Managing technological evolution in a complex environment. Res. Policy 1995, 24, 521–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.R. Agricultural sustainability and technology adoption: Issues and policies for developing countries. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2005, 87, 1325–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, B.; Mishra, A.K. Modernizing smallholder agriculture and achieving food security: An exploration in machinery services and labor reallocation in China. Appl. Econ. Perspect. Policy 2024, 46, 1662–1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.; Zhao, M.; Yao, L.; Qiao, D. Agricultural production and management form selection: Scale, organization, and efficiency—A case study of farmers in the Shiyang River Basin of the Northwest Arid Region. J. Agrotech. Econ. 2016, 2, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.Y. Rural reforms and agricultural growth in China. Am. Econ. Rev. 1992, 82, 34–51. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/2117601 (accessed on 3 October 2025).

- Röling, N. Pathways for impact: Scientists’ different perspectives on agricultural innovation. Int. J. Agric. Sustain. 2009, 7, 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjalmarsson, L.; Kumbhakar, S.C.; Heshmati, A. DEA, DFA and SFA: A comparison. J. Product. Anal. 1996, 7, 303–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Cook, W.D.; Li, N.; Zhu, J. Additive efficiency decomposition in two-stage DEA. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2009, 196, 1170–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, R.E. Land tenure, fixed investment, and farm productivity: Evidence from Zambia’s Southern Province. World Dev. 2004, 32, 1641–1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butzer, R.; Mundlak, Y.; Larson, D.F. Measures of fixed capital in agriculture. In Productivity Growth in Agriculture: An International Perspective; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2012; pp. 313–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandth, B.; Haugen, M.S. Farm diversification into tourism–implications for social identity? J. Rural Stud. 2011, 27, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Zhao, Z.; Liu, D. Impact of agricultural mechanization on agricultural production, income, and mechanism: Evidence from Hubei province, China. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 838686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Rousseau, R.; Chen, J. A new approach for measuring the value of patents based on structural indicators for ego patent citation networks. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2012, 63, 1834–1842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Dai, J.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, W. The impact of agricultural trade on green technological innovation in China’s agricultural sector. Iscience 2024, 27, 111101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiore, V.; Borrello, M.; Carlucci, D.; Giannoccaro, G.; Russo, S.; Stempfle, S.; Roselli, L. The socio-economic issues of agroecology: A scoping review. Agric. Food Econ. 2024, 12, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Long, H.; Tang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Qu, Y. Analysis of the spatial variations of determinants of agricultural production efficiency in China. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2021, 180, 105890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Xia, Y.; Jin, J.; Pan, C. The impact of climate change on the efficiency of agricultural production in the world’s main agricultural regions. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2022, 97, 106891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Shi, Y.; Khan, S.U.; Zhao, M. Research on the impact of agricultural green production on farmers’ technical efficiency: Evidence from China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 38535–38551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aragón, F.M.; Restuccia, D.; Rud, J.P. Are small farms really more productive than large farms? Food Policy 2022, 106, 102168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul-Rahaman, A.; Issahaku, G.; Zereyesus, Y.A. Improved rice variety adoption and farm production efficiency: Accounting for unobservable selection bias and technology gaps among smallholder farmers in Ghana. Technol. Soc. 2021, 64, 101471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Definition/Unit | Mean | SD | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Input variables | |||||

| Total assets | Ten thousand yuan (CNY), logarithmic form | 3.645 | 1.432 | 0.693 | 6.965 |

| Number of farm employees | Persons, logarithmic form | 1.497 | 0.494 | 0.693 | 3.178 |

| Output Variables | |||||

| Total income | Ten thousand yuan (CNY), logarithmic form | 3.453 | 1.661 | 1.000 | 7.397 |

| Efficiency | |||||

| Efficiency | Unitless DEA efficiency score (0–1 range) | 0.424 | 0.131 | 0.068 | 0.965 |

| Key explanatory variables | |||||

| Pilot Zone establishment | Pilot areas during the pilot period = 1, others = 0 | 0.017 | 0.130 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| Control Variables | |||||

| No. of patents | Pieces | 0.020 | 0.646 | 0.000 | 67.000 |

| No. of certifications | Pieces | 0.003 | 0.099 | 0.000 | 7.000 |

| Registered capital | Ten thousand yuan (CNY), logarithmic form | 4.160 | 1.177 | 0.000 | 19.000 |

| Whether they have other investments | Dummy variable (1 = Yes, 0 = No) | 0.021 | 0.144 | 0 | 1 |

| Whether they have online shops | Dummy variable (1 = Yes, 0 = No) | 0.018 | 0.133 | 0 | 1 |

| Whether they have abnormal operations | Dummy variable (1 = Yes, 0 = No) | 0.109 | 0.312 | 0 | 1 |

| Whether they have been punished | Dummy variable (1 = Yes, 0 = No) | 0.010 | 0.102 | 0 | 1 |

| Whether they have trademarks | Dummy variable (1 = Yes, 0 = No) | 0.026 | 0.158 | 0 | 1 |

| Establishment time | Years since establishment | 4.027 | 1.371 | 4 | 9 |

| Before Implementation | After Implementation | Difference | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inside Pilot Zone | 0.436 | 0.455 | 0.019 ** |

| Outside Pilot Zone | 0.421 | 0.418 | 0.003 *** |

| Difference | 0.015 *** | 0.017 *** | 0.018 *** |

| Variable Name | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treat × Period | 0.036 *** | 0.036 *** | 0.039 *** | 0.038 *** |

| (0.006) | (0.006) | (0.006) | (0.006) | |

| No. of patents | −0.004 *** | −0.003 ** | −0.002 | |

| (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | ||

| No. of certifications | 0.014 * | 0.016 ** | 0.022 *** | |

| (0.008) | (0.008) | (0.008) | ||

| Registered capital | −0.019 *** | −0.017 *** | ||

| (0.001) | (0.001) | |||

| Whether they have other investments | −0.011 * | 0.002 | ||

| (0.006) | (0.006) | |||

| Whether they have online shops | 0.020 *** | 0.026 *** | ||

| (0.007) | (0.007) | |||

| Whether they abnormal operations | −0.019 *** | −0.013 *** | ||

| (0.002) | (0.002) | |||

| Whether they have been punished | 0.002 | 0.005 | ||

| (0.007) | (0.008) | |||

| Whether they have trademarks | 0.014 *** | 0.020 *** | ||

| (0.005) | (0.005) | |||

| Establishment time | −0.002 *** | −0.003 *** | ||

| (0.001) | (0.001) | |||

| Constant item | 0.395 *** | 0.395 *** | 3.806 *** | 5.687 *** |

| (0.001) | (0.001) | (1.148) | (1.133) | |

| N | 58,814 | 58,814 | 58,814 | 58,814 |

| Model 5 | Model 6 | Model 7 | Model 8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Operating Earnings | Efficiency | Efficiency | Efficiency |

| Treat × Time | 0.284 *** | 0.041 *** | 0.042 *** | 0.035 *** |

| (0.054) | (0.006) | (0.006) | (0.005) | |

| Other policies | 0.020 *** | |||

| (0.003) | ||||

| Control variables | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year fixed effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Province fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Industry fixed effects | – | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Constant term | 163.690 *** | 8.565 *** | 8.622 *** | 15.840 *** |

| (14.258) | (1.836) | (1.837) | (2.513) | |

| N | 58,814 | 58,814 | 58,814 | 49,665 |

| Model 8 | Model 9 | Model 10 | Model 11 | Model 12 | Model 13 | Model 14 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Eastern Region | Central Region | Western Region | Plantations | Forestry | Livestock | Fisheries |

| Treat × Time | 0.045 *** | 0.011 | 0.102 *** | 0.048 *** | 0.030 * | 0.034 ** | 0.044 *** |

| (0.009) | (0.012) | (0.019) | (0.010) | (0.016) | (0.014) | (0.012) | |

| Control variable | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Annual fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Province fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 13,798 | 34,542 | 10,474 | 25,184 | 6460 | 16,498 | 15,157 |

| Model 15 | Model 16 | Model 17 | Model 18 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Technology Integration | Institutional Innovation | ||

| Treat × Time | 0.003 *** | 0.002 *** | 0.002 ** | 0.002 *** |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.001) | (0.000) | |

| Control variable | – | Yes | – | – |

| Annual fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Province fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 58,814 | 58,814 | 58,814 | 58,814 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Li, X.; Liu, Q.; Yang, X. The Impact of GAPPs on the Production Efficiency of Family Farms. Sustainability 2026, 18, 228. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010228

Li X, Liu Q, Yang X. The Impact of GAPPs on the Production Efficiency of Family Farms. Sustainability. 2026; 18(1):228. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010228

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Xuran, Qiang Liu, and Xingjie Yang. 2026. "The Impact of GAPPs on the Production Efficiency of Family Farms" Sustainability 18, no. 1: 228. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010228

APA StyleLi, X., Liu, Q., & Yang, X. (2026). The Impact of GAPPs on the Production Efficiency of Family Farms. Sustainability, 18(1), 228. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010228