Abstract

Sustainable language education necessitates scalable, accessible learning environments that foster long-term learner autonomy and reduce educational inequality. While online courses have democratized access to language learning globally, persistent deficiencies in instructor-student interaction and learner engagement compromise their sustainability. The “face effect,” denoting the influence of instructor facial appearance on learning outcomes, remains underexplored as a resource-efficient mechanism for enhancing engagement in digital environments. Furthermore, effective measures linking psychological engagement to sustained learning experiences are notably absent. This study addresses three research questions within a sustainable education framework: (1) How does instructor identity, particularly facial appearance, affect second language learners’ outcomes and interactivity in scalable online environments? (2) How can digital human technology dynamically personalize instructor appearance to support diverse learner populations in resource-efficient ways? (3) How does instructor identity influence learners’ flow state, a critical indicator of intrinsic motivation and self-directed learning capacity? Two controlled experiments with Japanese language learners examined three instructor identity conditions: real teacher identity, learner self-identity, and idol-inspired identity. Results demonstrated that the self-identity condition significantly enhanced oral performance and flow state dimensions, particularly concentration and weakened self-awareness. These findings indicate that identity-adaptive digital human instructors cultivate intrinsic motivation and learner autonomy, which are essential competencies for lifelong learning. This research advances Sustainable Development Goal 4 (Quality Education) by demonstrating that adaptive educational technology can simultaneously improve learning outcomes and psychological engagement in scalable, cost-effective online environments. The personalization capabilities of digital human instructors provide a sustainable pathway to reduce educational disparities while maintaining high-quality, engaging instruction accessible to diverse global populations.

1. Introduction

The United Nations Sustainable Development Goal 4 (Quality Education) underscores the imperative of developing scalable, accessible, and equitable learning environments capable of serving diverse global populations [1]. As educational institutions worldwide seek to fulfill this mandate, the design of learning systems must balance effectiveness with sustainability—ensuring that pedagogical innovations can be implemented across varied socioeconomic contexts without excessive resource consumption or infrastructure dependency.

Online courses have emerged as a pivotal mechanism for advancing sustainable language education. By eliminating geographical barriers, these platforms democratize access to learning opportunities while simultaneously reducing carbon footprints associated with commuting [2,3]. The asynchronous availability of course materials facilitates knowledge consolidation through repeated viewing and supports self-directed learning [4], while personalized pacing fosters learner autonomy—a cornerstone of lifelong learning and educational sustainability [4]. However, these advantages are undermined by critical challenges that threaten long-term effectiveness. The attenuated interaction between instructors and students in virtual environments often fails to replicate the dynamic, interactive atmosphere of traditional classrooms [5], potentially diminishing intrinsic motivation and sustained engagement [2]. Furthermore, the absence of physical co-presence increases susceptibility to external distractions, reduces focus, and may weaken learning persistence due to limited face-to-face supervision and social accountability [6]. These challenges pose significant barriers to cultivating self-regulated learners capable of continuous skill development.

Existing research aimed at enhancing online course effectiveness has predominantly pursued two directions. Technical optimization approaches focus on improving platform interface design and video playback quality to enhance user engagement [7,8], while pedagogical innovation emphasizes course format redesign and instructional design strategies to improve information delivery efficiency [9]. Although these approaches have yielded valuable insights, they operate within a resource-intensive paradigm that primarily addresses environmental and content-related factors. This paradigm presents scalability constraints across diverse socioeconomic contexts and overlooks a fundamental mechanism for human engagement: nonverbal communication features. Specifically, research has insufficiently explored how nonverbal cues—particularly facial features—can serve as human-centric, resource-efficient mechanisms for enhancing psychological engagement and learning outcomes in online environments.

In interpersonal communication, facial appearance functions as a powerful medium for emotional connection and trust establishment. Psychological research demonstrates that individuals exhibit heightened affinity and trust toward faces that resemble their own [10,11,12], a phenomenon termed the “face effect.” Despite its robust empirical foundation in social psychology, this effect remains critically underexplored in online language learning contexts. The integration of digital human technology offers a sustainable solution by enabling dynamic personalization of instructor appearance, thereby creating psychologically resonant learning experiences at scale. This approach aligns with fundamental sustainability principles: (1) enhancing accessibility through scalable, cost-effective instruction that does not require proportional increases in human instructor resources; (2) fostering intrinsic motivation and learner autonomy essential for lifelong learning; and (3) reducing educational disparities by democratizing access to personalized pedagogical support without necessitating extensive infrastructural investments.

While theoretical frameworks suggest that personalized nonverbal features can enhance emotional engagement, effective indicators for measuring how such engagement translates into sustained learning experiences and self-directed learning capacity remain underdeveloped. Flow theory [13], which characterizes optimal psychological states involving deep engagement, intrinsic motivation, and absorption in task performance, provides a promising framework for assessing the sustainability of learner engagement. By examining flow states as an outcome variable, researchers can evaluate whether technological interventions produce not merely momentary satisfaction but enduring psychological conditions conducive to continuous learning.

This study addresses these identified gaps by investigating the following research questions within a sustainable education framework:

- RQ1: How does instructor identity, particularly facial appearance, influence second language learners’ learning outcomes and engagement in scalable online environments?

- RQ2: How can digital human technology be leveraged to dynamically personalize instructor appearance to support diverse learner populations in resource-efficient ways?

- RQ3: How does instructor identity affect learners’ flow state in online education settings, which is regarded as a key indicator of intrinsic motivation and self-directed learning capacity.

By addressing these questions, this research contributes to the advancement of sustainable language education through technology-enabled personalization that enhances both learning outcomes and psychological engagement.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Sustainable Online Education: Technological and Pedagogical Approaches

The transition to online education represents a critical shift toward more sustainable, scalable, and accessible learning systems that align with global educational equity goals. As online education technologies develop rapidly, a growing body of research has focused on enhancing the effectiveness and sustainability of online course instruction. These studies primarily address two interconnected aspects: the optimization of platform functionalities to support scalable learning environments, and the improvement of pedagogical designs to foster learner autonomy and long-term engagement.

Technical optimization of online course platforms has proven essential for creating sustainable, resource-efficient learning environments. Li et al. demonstrated that virtual online lab environments can overcome temporal and spatial constraints while reducing the need for physical infrastructure, thereby enhancing both instructional interactivity and environmental sustainability [7]. Chukwu confirmed that gamification elements (e.g., points, leaderboards) significantly improve learner engagement and outcomes through intrinsic motivation mechanisms [14]. Mayer’s cognitive theory of multimedia learning emphasizes that incorporating motivational design principles into digital learning environments can enhance both engagement and learning outcomes by reducing extraneous cognitive load while fostering intrinsic motivation [15]. Furthermore, personalized learning systems based on learners’ preferences, such as adaptive content selection [16] or intelligent recommendation [17], have shown potential to enhance learning motivation and self-efficacy, key competencies for self-directed, lifelong learning. Kalyuga further demonstrated that personalized, self-referential content can improve instructional efficiency in e-learning environments by aligning cognitive demands with individual learner characteristics [18].

Beyond technological optimization, pedagogical innovations have explored methods to cultivate sustained learner engagement and autonomy. Kang et al. indicated that forum-based collaborative learning can stimulate learner agency, increase intrinsic participation and motivation, and enhance meaningful teacher-student interaction [9]. The concept of instructor immediacy, defined as verbal and nonverbal behaviors that reduce psychological distance between instructors and students, has been identified as a critical factor in online learning success. Baker found that instructor immediacy and presence significantly impact students’ affective learning, cognition, and motivation in online environments [19]. Richardson et al.’s meta-analysis confirmed that social presence, closely related to instructor immediacy, positively correlates with student satisfaction and learning outcomes in online settings [20]. Li et al. found that strengthening teachers’ online presence and instructional involvement improves student satisfaction, engagement, and overall learning experience [21]. Zhang et al. noted that teacher enthusiasm and emotional support (e.g., positive attitudes, encouraging language) enhance students’ intrinsic motivation and emotional engagement, which are critical factors for sustained learning [22].

While these studies offer valuable insights into sustainable online course design, most existing work has concentrated on systemic and content-level optimizations, with insufficient attention to human-centric, resource-efficient mechanisms such as nonverbal communication and the potential of pedagogical agents. Pedagogical agents, which are virtual representations of instructors or guides in digital learning environments, have emerged as promising tools for enhancing social agency and learner engagement. Baylor and Kim demonstrated that pedagogical agents can effectively simulate various instructional roles, from motivator to expert, thereby providing scalable personalized support [23]. Schroeder and Adesope’s systematic review revealed that agent persona design influences learners’ motivation and cognitive load, suggesting that thoughtful visual representation can enhance learning experiences [24]. The media equation theory proposed by Reeves and Nass suggests that individuals unconsciously apply social rules to computer-mediated interactions, treating virtual agents as social actors [25]. This theoretical foundation supports the notion that digitally represented instructors can elicit genuine social and emotional responses, making them viable mechanisms for enhancing engagement in resource-constrained educational contexts.

In online educational environments, teachers’ nonverbal behaviors (e.g., facial expressions, intonation, gestures) are often inadequately conveyed, limiting students’ emotional connection and psychological engagement, which are barriers to developing the intrinsic motivation essential for lifelong learning. Addressing this gap, the present research explores how digital human technology can leverage teachers’ visual representations to enhance nonverbal communication functions, thereby fostering deeper engagement and learner autonomy in scalable, cost-effective online instructional settings.

2.2. Nonverbal Communication as a Resource-Efficient Engagement Mechanism

Nonverbal information (e.g., facial expressions, body movements, vocal intonation) plays a vital role in interpersonal communication and instructional interaction, representing a fundamentally human-centric mechanism that requires minimal technological resources while yielding substantial psychological impact. Knapp, Hall, and Horgan’s comprehensive framework of nonverbal communication demonstrates that visual, vocal, and kinesthetic cues constitute fundamental channels through which meaning, emotion, and relational information are transmitted in human interaction [26].

Extensive interdisciplinary research has documented the value of nonverbal information across diverse professional domains. In medical consultations, Ong et al. demonstrated that physicians can enhance diagnostic accuracy by observing patients’ facial expressions and vocal tension [27]. Similarly, therapeutic services rely heavily on nonverbal feedback, where counselors’ facial expressions, vocal tone, and posture significantly influence clients’ emotional regulation and communication willingness [28,29]. In educational contexts, teachers’ nonverbal behaviors reduce psychological distance with students and enhance classroom rapport, fostering environments conducive to sustained engagement and self-directed learning. Allen, Witt, and Wheeless conducted a meta-analysis demonstrating that teacher immediacy behaviors, predominantly nonverbal cues such as eye contact, smiling, and gestures, serve as significant motivational factors that enhance student learning outcomes [30]. Richmond, Lane, and McCroskey further established that immediacy behaviors strengthen teacher-student relationships by creating perceptions of warmth, approachability, and psychological closeness [31].

For instance, Pi et al. found that teachers’ facial expressions directly influence students’ emotional states, with positive expressions evoking positive reactions and boosting intrinsic learning motivation [32]. Paulmann et al. noted that vocal characteristics (e.g., autonomy-supportive tone) foster positive emotions and psychological intimacy, increasing students’ willingness to engage autonomously, while controlling tones may undermine learner agency [33]. Moreover, rewarding nonverbal actions such as nodding or smiling can stimulate intrinsic motivation and participation, alleviate anxiety, and cultivate positive learning atmospheres that support long-term engagement [34,35]. Research on foreign language anxiety and enjoyment provides additional support for the emotional dimension of learning. Horwitz, Horwitz, and Cope identified foreign language classroom anxiety as a distinct psychological construct that significantly impairs learning performance [36]. Conversely, Dewaele and MacIntyre demonstrated that foreign language enjoyment, often facilitated by supportive instructor behaviors and positive classroom climate, serves as a counterbalance to anxiety and promotes sustained engagement [37].

In online educational environments, the transmission of such nonverbal cues becomes particularly challenging, yet research suggests that their impact remains significant. Russo and Benson found that learners’ perceptions of “invisible others” in online settings, including their sense of instructor presence conveyed through limited nonverbal channels, relate significantly to both cognitive and affective learning outcomes [38]. Moreno and Mayer demonstrated that personalized, socially-oriented messages in virtual learning environments, which simulate aspects of face-to-face communication, can promote deeper learning by enhancing learners’ sense of social connection with the instructional content [39].

Overall, interdisciplinary evidence suggests that teachers’ nonverbal cues play pivotal roles in conveying instructional intent, stimulating intrinsic motivation, and providing emotional support, all of which are essential for sustainable learning experiences. However, most existing research has focused on traditional face-to-face classrooms, with limited investigation into how nonverbal communication can be effectively transmitted and potentially enhanced in online education through digital human technologies. In virtual environments, the absence of rich nonverbal channels hinders both immediate teaching effectiveness and long-term learner engagement. Therefore, leveraging digital human technologies to integrate and amplify nonverbal elements (e.g., personalized visual appearance, expressive behaviors) represents a promising, resource-efficient pathway to enhance sustainable online education.

2.3. Self-Reference and Avatar Personalization Effects

An emerging body of research suggests that personalized visual representations, particularly those that incorporate self-referential features, can significantly enhance psychological engagement and behavioral outcomes in digital environments. The self-reference effect, originally documented by Rogers, Kuiper, and Kirker, demonstrates that information processed in relation to the self is recalled more effectively than information processed through other encoding strategies [40]. This cognitive advantage extends beyond memory to encompass motivational and affective dimensions, suggesting that self-relevant stimuli command greater attention and foster deeper processing.

In avatar-mediated interactions, the Proteus effect describes how individuals’ behaviors and attitudes are influenced by the characteristics of their digital self-representations. Yee and Bailenson demonstrated that users who embody taller or more attractive avatars exhibit corresponding behavioral changes, such as increased confidence in negotiations [41]. Extending this research, Ratan and Dawson examined the psychophysiological responses to self-relevant avatars, finding that greater avatar self-relevance corresponds with heightened engagement and emotional investment [42]. While the Proteus effect traditionally focuses on self-representation, these findings suggest broader implications for how self-relevant visual features, including those of instructors or pedagogical agents, might enhance learner engagement through mechanisms of identification and psychological proximity.

When applied to pedagogical contexts, self-referential personalization of instructor appearance may activate similar cognitive and motivational mechanisms, potentially reducing psychological distance and enhancing learners’ sense of connection with instructional content. This theoretical foundation, combined with evidence from nonverbal communication research, suggests that personalized digital human instructors could serve as effective, scalable tools for fostering sustained engagement and intrinsic motivation in online learning environments.

2.4. Flow State as an Indicator of Sustainable Learning Engagement

While nonverbal cues from teachers and personalized pedagogical agents can enhance emotional engagement, valid indicators that capture whether such engagement leads to sustained and self-directed learning remain limited. Flow theory, originally proposed by Csikszentmihalyi, provides a theoretically grounded framework for assessing the quality and long-term potential of learner engagement. Flow describes a psychological state of deep concentration and optimal functioning in which individuals become fully absorbed in an activity. This state involves focused attention, clear goals, unambiguous feedback, a sense of control, reduced self-awareness, altered time perception, and intrinsic enjoyment [43]. Importantly, flow experiences are closely tied to intrinsic motivation, which forms the basis of autonomous and lifelong learning.

In educational contexts, flow has been widely applied to examine and promote sustainable engagement. Shernoff et al. showed that appropriately challenging tasks, clearly defined goals, and timely feedback support high school students’ experience of flow and their sustained participation across extended periods [44]. Research in second language learning provides parallel evidence. Egbert demonstrated that tasks aligned with flow principles, such as optimal challenge and immediate feedback, facilitate learners’ entry into flow states, thereby strengthening intrinsic motivation and improving language acquisition outcomes [45]. Such findings indicate that flow states are meaningful indicators of the deep cognitive and motivational engagement that characterizes sustainable learning.

As online education expands, flow theory has been increasingly applied to digital learning environments. Esteban-Millat et al. identified focused attention and time distortion as core components of online flow and emphasized task personalization and optimal challenge as central factors that shape these experiences [46]. Empirical studies confirm that flow in online contexts enhances learning outcomes, promotes positive affect, and supports psychological well-being. These benefits are associated with prolonged engagement and continued learning beyond formal instructional settings [46].

Despite these developments, many current evaluation methods in online learning remain limited in their ability to capture psychological dimensions essential for sustainable learning. Traditional assessments typically emphasize short-term performance or learner satisfaction, while overlooking learners’ motivational states, cognitive absorption, and self-regulation during the learning process. Approaches that rely solely on summative evaluation struggle to account for the dynamic and personalized nature of sustainable online learning, where real-time insight into learners’ psychological engagement is crucial.

To address these gaps, this study incorporates flow state assessment into online educational evaluation frameworks. This integration enables more comprehensive measurement of not only immediate learning outcomes but also deeper indicators of sustained engagement, intrinsic motivation, and autonomous learning capacity. By examining how personalized digital human teachers shape learners’ flow experiences, the study contributes to the development of online environments that support learner autonomy, long-term motivation, and continued engagement, which are competencies essential for achieving sustainable education goals.

3. Experiment 1: Online Self-Regulated Learning

3.1. Experimental Conditions and Hypotheses

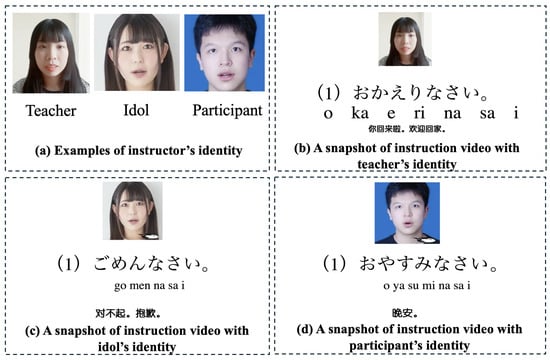

This experiment employed a single-factor design to investigate how personalized teacher identity can enhance sustainable learning engagement in scalable online environments. The independent variable was the instructor’s identity, comprising three experimental conditions:

- C1—Real Teacher Identity: In video instruction, the digital human instructor taught using the real teacher’s original appearance and voice, representing traditional pedagogical authority.

- C2—Self Identity: In video instruction, the digital human instructor taught using the participant’s own appearance and voice, designed to enhance intrinsic motivation through self-referential processing.

- C3—Idol-Inspired Identity: In video instruction, the digital human instructors delivered lessons using the participant’s favorite idol’s appearance and voice, exploring the potential of aspirational or attractive identification.

This experimental design enables systematic investigation of the following hypotheses regarding sustainable learning engagement:

- H1: In the online self-regulated learning context, the digital human instructor’s identity significantly impacts students’ oral test scores, indicating potential for scalable personalized instruction.

- H2: In the online self-regulated learning context, the digital human instructor’s identity significantly impacts students’ flow states, a key indicator of intrinsic motivation and self-directed learning capacity essential for lifelong learning.

The experiment 1 directly addresses RQ1 (teacher identity effects on learning outcomes and interactivity) and RQ3 (teacher identity effects on flow states) in an online self-regulated learning context. The three identity conditions (real teacher, self, idol) enable systematic investigation of how facial appearance personalization influences both objective learning performance and subjective psychological engagement. By measuring both oral performance outcomes and flow state dimensions, this design captures the dual focus of sustainable education—immediate effectiveness and long-term engagement potential.

3.2. Manipulation Check

To verify the effectiveness of identity manipulations, participants rated three instructor characteristics on 5-point Likert scales following the learning session: self-similarity, authority, and attractiveness. Repeated measures one-way ANOVAs were conducted to examine differences across the three identity conditions.

Results confirmed successful manipulation of intended identity features (see Table 1). Self-similarity ratings differed significantly across conditions (, ), with the Self condition (, ) rated substantially higher than both Real Teacher (, ) and Idol conditions (, ), validating the self-referential manipulation. Authority ratings also varied significantly (, ), with Real Teacher (, ) perceived as more authoritative than Self (, ) and Idol (, ) conditions, confirming traditional pedagogical credibility associations. Attractiveness ratings demonstrated significant differences (, ), with Idol-Inspired identity (, ) rated higher than Self (, ) and Real Teacher (, ) conditions, supporting the aspirational appeal manipulation. These patterns confirm that each identity condition activated its theoretically intended psychological dimensions.

Table 1.

Manipulation check results for instructor identity characteristics (Experiment 1).

3.3. Procedure

This experiment recruited nine university students aged 18 to 25, all of whom were Japanese beginners with no prior experience in language instruction with digital humans. All participants signed an informed consent form and took part in the experiment voluntarily. The experimental design used a within-subject design with random ordering of conditions. This ensured the scientific validity and comparability of the results while adhering strictly to ethical review requirements.

Each participant engaged in self-regulated learning across the three experimental conditions, providing insights into how identity-adaptive digital humans can support autonomous learning behaviors critical for sustainable education. The self-regulated learning lasted for six hours in total across three sessions, with one day between each learning session. The content for the three learning sessions focused on everyday conversational Japanese. Each session included Japanese text, romanization for pronunciation guidance, and video instruction materials delivered through resource-efficient digital human technology. The course materials were carefully designed to ensure that the lexical items, length, and difficulty of the content were equivalent across the three learning sessions, thus eliminating confounding between-conditions differences.

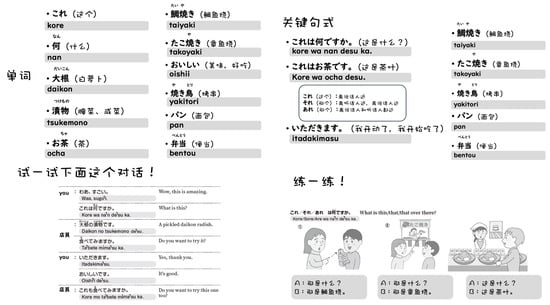

The examples of the materials used in self-regulated learning sessions are shown in Figure 1. After each teaching session, participants completed an oral test and a flow state assessment with a subjective questionnaire. These evaluations were conducted separately following each session to facilitate comparisons of the different conditions’ effects on both immediate learning outcomes and psychological engagement indicators predictive of sustained learning. To prevent content-identity confounding, lesson materials were counterbalanced across identity conditions using a Latin square design (see Table 2). Participants were randomly assigned to condition orders, ensuring each lesson was paired equally with each identity condition across the sample. The order of session within one group is shuffled. Materials were equivalent in vocabulary count, grammatical structures, and length.

Figure 1.

Examples of instruction video with Japanese content and its translations in Chineses and English for the online self-regulated learning. Please refer to Appendix Section (Appendix A) for more details of the experimental system.

Table 2.

Pairs of learning contents and conditions for experiment 1.

The experimental procedure comprised the following steps:

- Experiment Introduction: Participants received a concise overview of the experiment’s purpose and the potential of digital human technology to create personalized, scalable learning experiences. The three digital human instructor’s identities were displayed via video, and a detailed explanation of the experimental procedure was provided. Participants were informed that all learning and testing tasks would be completed through an online conference platform, and that they would be required to complete a flow state questionnaire to assess their psychological engagement.

- Teaching Phase: Each participant was sequentially provided with standardized Japanese teaching materials for the three experimental conditions. The materials included Japanese text, romanized pronunciation guides, and instructional videos delivered by identity-adaptive digital humans. The order of the teaching materials was randomized to mitigate potential sequence effects. Participants had six hours of self-regulated learning time and could review the teaching materials at their convenience, simulating the flexible, self-paced learning essential for sustainable education.

- Testing Tasks and Questionnaire Completion: After each teaching session, participants completed an oral test based on the Japanese text. The system recorded their audio readings for submission to a Japanese language teacher. Subsequently, participants completed the flow state questionnaire to assess the flow state dimensions during the learning process, providing insights into their intrinsic motivation and autonomous engagement.

- Data Collection and Analysis: After the experiment, oral test scores and flow state questionnaire data for each participant under the three experimental conditions were collected with strict adherence to anonymity and ethical standards. Statistical analysis was performed to compare the differences in learning outcomes and psychological engagement among the different digital human instructor’s identities, informing the design of sustainable, personalized online education systems.

3.4. Measurement

This experiment utilized two primary methods to evaluate the impact of different digital human teachers on students’ Japanese oral learning outcomes: objective learning performance scores and subjective flow state assessments. This dual approach captures both immediate learning effectiveness and the psychological engagement essential for sustained, self-directed learning.

3.4.1. Learning Performance Scores

To provide a rigorous and theoretically grounded assessment of students’ oral learning outcomes, we evaluated their performance across three core dimensions of second language oral proficiency: lexical accuracy, phonetic accuracy, and fluency. These dimensions were selected based on communicative competence theory, which conceptualizes oral proficiency as a multidimensional construct involving organizational, phonological, and strategic competencies. Lexical accuracy captures learners’ command of word-level forms and morphological structures; phonetic accuracy reflects their ability to produce segmental and suprasegmental features intelligibly; and fluency indicates the degree of automaticity and continuity in speech production. Together, these components provide a comprehensive profile of oral performance by assessing both accuracy-related and fluency-related aspects of language use, which are widely recognized as the two fundamental parameters of L2 oral proficiency.

To ensure measurement reliability and fairness, the scoring process followed a standardized protocol. Three experienced Japanese language instructors, who had jointly calibrated and discussed the scoring criteria in advance, independently evaluated each student’s oral output. Their scores were averaged to produce the final performance score. This multi-rater approach minimizes subjective bias and enhances inter-rater reliability. All audio recordings were anonymized and labeled only with participant IDs and session numbers, without any indication of the instructional identity condition (Real Teacher, Self, or Idol). The recordings were randomly ordered so that raters could not infer grouping or sequence from file arrangement. Raters were informed only that the audio samples came from students who had learned through online teaching formats and no information about the identity manipulation, use of digital human teachers, or study hypotheses was disclosed. Additionally, the scoring rubric was designed to adhere closely to both theoretical principles and practical instructional standards, with clear numerical ranges, decision rules, and illustrative examples included in Table 3. These additions help ensure transparency and consistency in how performance scores were assigned across learners and across the three assessed dimensions.

Table 3.

Scoring Criteria for Learning Performance (Oral Test) in Online Self-regulated Learning Experiment.

3.4.2. Flow State Assessment

To assess students’ psychological engagement and flow experiences during learning, we employed the Flow State Scale (FSS) developed by Jackson and Marsh [43], adapted for online language learning contexts. The FSS is grounded in Csikszentmihalyi’s [13] flow theory and has been extensively validated across multiple domains, demonstrating robust psychometric properties in diverse activities including educational settings [43]. We made minimal adaptations to the original FSS to suit our online language learning context: (1) Contextual modification: Changed activity referents from generic “activity” to “language learning” (e.g., original: “I was completely focused on the task at hand” → adapted: “I was completely focused on language learning content”); (2) Retained core elements: All original item content and wording (except context referent), original 5-point Likert response format (1 = Strongly Disagree, 5 = Strongly Agree), and five-dimensional structure corresponding to core flow components. Flow states are considered critical indicators of intrinsic motivation and deep engagement that predict continued learning beyond formal instruction. Dimension scores were calculated as the mean of constituent items for each participant in each condition.

3.5. Results

3.5.1. Oral Learning Performance

To ensure scoring objectivity, we assessed inter-rater reliability among the three Japanese teaching experts using Intraclass Correlation Coefficients (ICC). The results demonstrated excellent reliability across all measures. Lexical accuracy showed the highest agreement with ICC(2,3) = 89%, followed by phonetic accuracy at ICC(2,3) = 87%. Fluency exhibited strong reliability with ICC(2,3) = 85%. All ICC values exceeded the threshold of 80%, indicating excellent inter-rater agreement and confirming the consistency of scoring procedures across the three raters. Initial observations of descriptive orderings based on observed means rather than confirmed effects across conditions:

- Total Score: Condition 2 (Self Identity) () > Condition 1 (Real Teacher Identity) () > Condition 3 (Idol-Inspired Identity) ()

- Fluency: Condition 2 () > Condition 1 () > Condition 3 ()

- Phonetic Accuracy: Condition 2 () > Condition 1 () > Condition 3 ()

- Lexical Accuracy: Condition 2 () > Condition 3 () > Condition 1 ()

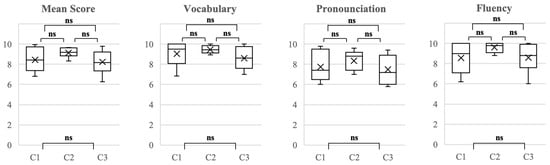

The results of Shapiro–Wilk Test () shows our collected data follow the normal distribution. Results of the repeated measures one-way ANOVA (Figure 2) indicated no significant effects of instructor’s identity on learners’ oral fluency (, , ), phonetic accuracy (), or lexical accuracy (). While statistical significance was not achieved in this preliminary study, the consistent pattern of higher mean scores in the self-identity condition suggests potential benefits that may become more pronounced in longer-term learning contexts.

Figure 2.

Results of objective learning performance scores in online self-regulated learning. C1 is Real Teacher Identity; C2 is Self Identity; C3 is Idol-Inspired Identity. ns stands for non-significant difference.

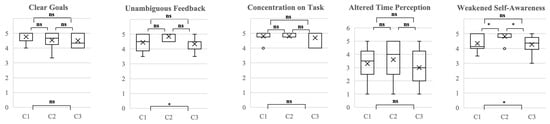

3.5.2. Flow State Analysis

Initial observations of the mean scores revealed the following rankings across conditions:

- Clear Goals: Condition 2 (, 95% CI [3.38, 4.12]) > Condition 3 (, 95% CI [3.21, 4.17]) > Condition 1 (, 95% CI [3.17, 4.05])

- Unambiguous Feedback: Condition 3 (, 95% CI [3.64, 4.32]) > Condition 1 (, 95% CI [3.45, 4.33]) > Condition 2 (, 95% CI [3.31, 4.35])

- Concentration on Task: Condition 2 (, 95% CI [3.23, 4.11]) > Condition 1 (, 95% CI [2.66, 3.28]) = Condition 3 (, 95% CI [2.64, 3.30])

- Altered Time Perception: Condition 1 (, 95% CI [3.55, 4.33]) > Condition 3 (, 95% CI [3.56, 4.28]) > Condition 2 (, 95% CI [3.12, 4.00])

- Weakened Self-Awareness: Condition 3 (, 95% CI [3.53, 4.47]) > Condition 1 (, 95% CI [3.38, 4.28]) > Condition 2 (, 95% CI [3.30, 4.20])

The results of Shapiro–Wilk Test () shows our collected data follow the normal distribution. Figure 3 shows the repeated measures one-way ANOVA results, which revealed a significant effect of instructor’s identity on learners’ concentration (, ), a key dimension of flow state associated with deep engagement and intrinsic motivation. Multiple comparisons revealed that students in the self-condition exhibited significantly higher concentration than those in the idol-condition () and teacher-condition (). A significant effect was found of instructor’s identity on learners’ altered time perception (), but the multiple comparisons showed no significant differences among three conditions. However, no significant difference was found between the teacher-condition and idol-condition. Additionally, digital human teacher images did not significantly impact clear goals (), unambiguous feedback (, ), altered time perception (), or weakened self-awareness ().

Figure 3.

Results of subjective flow-based assessment in online self-regulated learning. C1 is Real Teacher Identity; C2 is Self Identity; C3 is Idol-Inspired Identity. ∗ indicates the significant difference while ns stands for non-significant difference.

3.6. Analysis

The results indicate that the self-identity condition was associated with higher levels of reported concentration compared with the other instructional identities. This pattern is consistent with Hypothesis 2, although the evidence is limited to subjective flow measures and should be interpreted within the scope of the present experimental setting. No corresponding advantages were observed in phonetic or lexical accuracy, suggesting that any influence of teacher identity may not generalize across all learning outcomes measured in this study.

The self-condition also showed relatively stable performance across participants, whereas the idol condition exhibited greater variability. This variability suggests that learner responses to visually stylized or aspirational identities may differ substantially across individuals. The present data do not indicate a uniform benefit or disadvantage for such identities, and further work is needed to clarify the conditions under which particular identity designs support or impede learning. While some theoretical accounts highlight potential effects of self-related cues or personally relevant stimuli on attention, the current study did not collect direct measures of attentional processes, motivation, or affect. As such, the mechanisms underlying the observed differences cannot be determined from the available data. The findings are therefore best viewed as descriptive evidence of differential learner responses rather than indicative of specific cognitive or motivational pathways. The absence of significant effects on phonetic and lexical measures suggests that short-term exposure to different digital-human teacher identities may have limited influence on performance-based outcomes in constrained learning tasks. The brief task structure and limited instructional duration may also contribute to the modest effect sizes observed.

Finally, although the within-subject design reduces individual differences as a source of variance, the short interaction period and controlled experimental setting restrict the generalizability of the findings. More extended learning scenarios, additional outcome measures, and larger samples would be needed to assess the reliability and practical relevance of identity-related differences in digital-human instructional contexts.

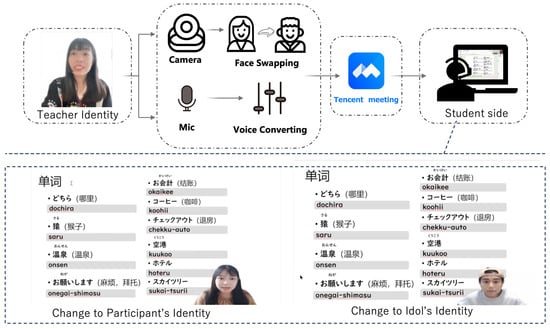

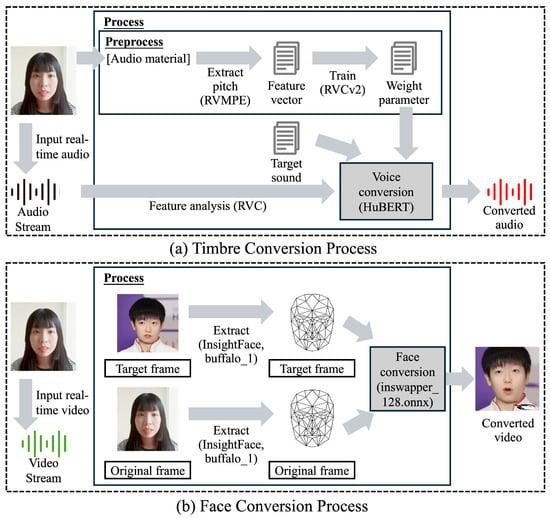

4. Experiment 2: Online Teaching

Building upon the findings of Experiment 1, which demonstrated significant identity effects on flow state (particularly concentration), Experiment 2 addresses all three research questions with enhanced ecological validity. As Figure 4 shows, the transition from pre-recorded videos to real-time face-voice-swapped streaming directly addresses RQ2, demonstrating how digital human technology can dynamically personalize teacher appearance in realistic, interactive online teaching contexts. The extended duration and increased interactivity provide stronger tests of RQ1 (sustained effects on learning outcomes) and RQ3 (flow states in dynamic interaction settings). For these sakes, experiment 2 introduced several key modifications designed to better simulate realistic online learning contexts. As illustrated in Figure 5, firstly, we transitioned from pre-recorded digital human instructor videos to face-voice-swapped real-teacher streaming. This change aimed to enhance the realism and interactivity of teacher-student interactions in the e-learning environment, more closely approximating the dynamic engagement critical for cultivating learner autonomy. Secondly, we extended the experimental duration and incorporated more interactive teaching elements to provide a more comprehensive assessment of how personalized digital human teachers influence both academic performance and the flow states predictive of continued learning motivation. By implementing these adjustments, Experiment 2 seeks to offer deeper insights into how teacher identity influences students’ learning experiences in ways that support sustainable, self-directed language learning.

Figure 4.

Interaction system and examples of Japanese learning materials for the online teaching. Please refer to Appendix Section for more details of the experimental system.

Figure 5.

Examples of learning materials of Japanese and its translation in English for the online teaching.

4.1. Experimental Procedure

This experiment recruited 12 university students (4 males and 8 females) aged between 18 and 25. All were Japanese beginners with no prior experience in digital-human-based language instruction. They all signed informed consent forms and participated voluntarily, adhering to ethical standards for research involving human participants.

The experiment employed a within-subject design to control for individual differences while examining the effects of personalized teacher identity on sustainable learning engagement. Each participant attended one class under each of the three conditions. Each class lasted approximately 30 min, with a one-day interval between classes to allow for consolidation and reduce fatigue effects. The class topics were “What is this?”, “Please take me to the monkey hot spring”, and “I want to buy a rice cooker”. The course content for each topic included words, key sentence patterns, dialogues, and interactive exercises designed to foster active participation and autonomous language use. The topics were selected by referring to the Japanese learning content for beginners developed by NHK, ensuring pedagogical validity and practical relevance. Figure 5 presents examples of materials.

Lesson 1, “これはなんですか (what is this, kore wa nan desu ka)?”, aimed to deepen the understanding of Japanese food culture while focusing on mastering practical expressions for ordering and asking questions, skills essential for autonomous communication in real-world contexts. In vocabulary, traditional foods (e.g., たい焼き-taiyaki, たこ焼き-takoyaki) and daily foods (e.g., 弁当-bento, パン-pan) were selected. In sentence pattern teaching, the focus was on the question-asking expression “Kore wa nan desu ka”. In practice exercises, a role-playing activity in a simulated restaurant scenario was implemented to promote active language use and intrinsic engagement.

Lesson 2, “猿の温泉までお願いします (please take me to the monkey hot spring, saru no onsen made onegaishimasu)”, focused on expressions needed for moving between accommodation facilities and sightseeing spots, especially for taking taxis. The vocabulary mainly included words like airport, hotel, and hot spring. In sentence pattern teaching, the core expression “-までお願いします (made onegaishimasu)” was emphasized, and the function of the particle “made” (indicating the destination) was explained. In practice exercises, students were asked to create dialogue scenarios between taxi drivers and passengers, fostering creative language application and autonomous communication skills.

Lesson 3, “炊飯器を買いたい (I want to buy a rice cooker, komensu o kaitai desu)”, aimed to develop basic communication skills for shopping in Japan. The vocabulary focused on words related to local specialties. In sentence pattern teaching, request expressions using “欲しい (I want, hoshii)” and fixed phrases for price negotiation were constructed. In practice exercises, through role-playing, students simulated conversations between shop assistants and customers, from price confirmation using “いくらですか (how much, ikura desu ka)” to completing the checkout process, promoting confident and autonomous language use in practical contexts.

To prevent content-identity confounding, lesson topics were counterbalanced across identity conditions using a Latin square design. Participants were randomly assigned to condition orders, ensuring each lesson was paired equally with each identity condition across the sample (see Table 4). The order of session within one group is shuffled. Oral tests and flow state assessments were conducted separately after each teaching session to compare the effects of different conditions on both immediate learning outcomes and psychological engagement indicators predictive of sustained learning motivation. The three lessons’ oral tests included three sub-tests: translation questions (Chinese to Japanese), pronunciation checks, and sentence pattern completion questions. The flow state assessment questionnaire was the same as in Experiment 1, measuring dimensions critical for understanding intrinsic motivation and self-directed learning capacity.

Table 4.

Pairs of learning contents and conditions for experiment 2.

- Experiment Introduction: Participants were briefly introduced to the experiment’s purpose, emphasizing the potential of personalized digital human technology to create more engaging and effective online learning experiences. They were informed that all learning and testing tasks would be completed via online conferences and that they would need to fill out a flow state questionnaire to assess their psychological engagement during learning.

- Learning Phase: Each participant attended online courses in all three experimental conditions delivered through identity-adaptive digital human technology. The course content included vocabulary, grammar explanations, and interactive exercises like word substitution and role-playing designed to promote active participation. The order of the conditions was randomly assigned to mitigate potential sequence effects and ensure valid comparisons.

- Testing Tasks and Questionnaire Completion: After each teaching session, participants completed an oral test based on the lesson content. The system recorded their audio readings and submitted them to a Japanese language teacher for evaluation. Subsequently, participants completed the flow state questionnaire to assess flow state dimensions during the learning process, providing insights into their intrinsic motivation and engagement quality.

- Data Collection and Analysis: After the experiment, oral test scores and flow state questionnaire data for each participant under the three experimental conditions were collected anonymously, adhering to ethical standards and privacy protections. Statistical analysis was performed to compare the differences in learning outcomes and psychological engagement among the different digital human teacher identities, informing the design of sustainable, personalized online education systems.

4.2. Experimental Conditions and Hypotheses

This experiment employed a single-factor design to investigate how personalized teacher identity influences sustainable learning outcomes and engagement in interactive online teaching contexts. The independent variable was the teacher’s image and voice type, comprising three experimental conditions:

- C1—Real Teacher Identity: In the online real-time course, the teacher taught using their original appearance and voice, representing traditional pedagogical presence and authority.

- C2—Self Identity: In the online real-time course, the teacher’s image and voice were replaced with the participant’s own image and a similar voice, designed to enhance intrinsic motivation through self-referential processing and psychological resonance.

- C3—Idol-Inspired Identity: In the online real-time course, the teacher’s face and voice were replaced with a participant’s favorite idol’s image and a similar voice, exploring the potential of aspirational identification to enhance engagement.

This experimental design enabled systematic investigation of the following hypotheses regarding sustainable learning outcomes:

- H1: Given prior studies and the results of Experiment 1, which indicate that learners have a preference for faces similar to their own and show enhanced concentration with self-identity conditions, it is hypothesized that replacing the teacher’s face with the learner’s own will optimize learning outcomes and foster the intrinsic motivation essential for sustained, autonomous learning.

- H2: Drawing on the Proteus effect theory, where virtual identity with salient attractiveness, authority, or capability (e.g., experts, celebrities) can enhance user performance through “identity projection”, it is posited that learners may have a stronger preference for idol faces, and thus replacing the teacher’s face with an idol’s will boost learners’ motivation and learning outcomes through aspirational engagement.

Based on these hypotheses, the study predicted the following order of learning effectiveness across the three conditions: the self-condition would yield the best learning outcomes and strongest flow states, followed by the celebrity-condition, with the real-teacher condition resulting in relatively weaker performance in dimensions related to intrinsic motivation and autonomous engagement.

4.3. Manipulation Check

Consistent with Experiment 1, participants evaluated three instructor characteristics following the interactive learning session: self-similarity, authority, and attractiveness, rated on 5-point Likert scales. One-way repeated-measures ANOVAs assessed whether the real-time face-voice-swapped streaming successfully maintained distinct identity manipulations in the more interactive context.

Results confirmed effective manipulation of identity characteristics in the dynamic teaching environment (see Table 5). Self-similarity ratings differed significantly across conditions (, ), with the Self condition (, ) substantially exceeding both Real Teacher (, ) and Idol conditions (, ), demonstrating robust self-referential perception even in real-time streaming. Authority ratings varied significantly (, ), with Real Teacher (, ) perceived as more authoritative than Self (, ) and Idol (, ) conditions, preserving traditional pedagogical credibility associations. Attractiveness ratings demonstrated significant differences (, ), with Idol-Inspired identity (, ) rated significantly higher than Self (, ) and Real Teacher (, ) conditions, confirming aspirational appeal. Notably, the manipulation effects remained robust despite the transition to real-time interactive streaming, with effect sizes comparable to or exceeding those in Experiment 1, validating the scalability of identity personalization in dynamic online teaching contexts.

Table 5.

Manipulation check results for instructor identity characteristics (Experiment 2).

4.4. Measurements

This experiment employed two primary methods to assess the impact of different digital human identities on students’ Japanese oral learning outcomes: learning performance scoring and flow state evaluation. This dual assessment approach captures both immediate learning effectiveness and the psychological engagement dimensions critical for sustained, self-directed learning.

To obtain a comprehensive and theoretically grounded evaluation of students’ learning outcomes in Experiment 2, we assessed their oral performance across four key dimensions of second language proficiency: lexical accuracy, grammatical accuracy, pronunciation accuracy, and fluency. These dimensions reflect core components of communicative competence, including organizational competence, morphosyntactic control, phonological competence, and strategic competence. Compared with Experiment 1, grammatical accuracy was included in this experiment to capture learners’ developing command of Japanese grammatical structures, which became more salient in the interactive instructional setting. This dimension evaluates morphosyntactic competence, including correct particle usage, verb conjugation, and sentence construction, which are particularly critical when learners must actively produce utterances based on newly taught grammatical patterns. To ensure reliable and unbiased scoring, three experienced Japanese language instructors independently evaluated all oral productions using a standardized rubric. Before scoring, the instructors jointly calibrated their interpretation of the criteria to ensure consistency. Importantly, all ratings were conducted under strict blinding procedures to prevent condition-related bias. All audio recordings were anonymized and labeled only with participant IDs and session numbers, without any indication of the instructional identity condition (Real Teacher, Self, or Idol). The recordings were randomly ordered so that raters could not infer grouping or sequence from file arrangement. Raters were informed only that the audio samples came from students who had learned through online teaching formats and no information about the identity manipulation, use of digital human teachers, or study hypotheses was disclosed. These procedures ensured that scoring reflected actual linguistic performance rather than expectations tied to instructional conditions. The final score for each dimension was calculated as the average of the three raters’ evaluations to improve objectivity and inter-rater reliability. The specific scoring criteria, including detailed rules and examples for grammatical accuracy, are shown in Table 6. The flow state assessment was identical to Experiment 1.

Table 6.

Scoring Criteria for Learning Performance (Oral Test) in Online Teaching.

4.5. Results

4.5.1. Oral Learning Performance

Inter-rater reliability was examined using Intraclass Correlation Coefficients (ICC) to establish scoring consistency among the three Japanese teaching experts. The analysis revealed excellent agreement across all four performance dimensions. Lexical accuracy demonstrated the strongest reliability with ICC(2,3) = 91%, followed by grammatical accuracy at ICC(2,3) = 88%, Phonetic accuracy showed ICC(2,3) = 86%. All ICC coefficients surpassed the 80% benchmark for reliability, demonstrating robust inter-rater consistency and validating the scoring framework employed in this study. Initial observations of descriptive orderings based on observed means rather than confirmed effects across conditions:

- Total Score: Condition 2 (Self Identity) (, 95% CI [9.18, 9.68]) > Condition 1 (Real Teacher Identity) (, 95% CI [8.32, 8.88]) > Condition 3 (Idol-Inspired Identity) (, 95% CI [7.27, 9.11])

- Fluency: Condition 2 (, 95% CI [9.19, 9.81]) > Condition 1 (, 95% CI [8.03, 8.75]) > Condition 3 (, 95% CI [7.33, 9.23])

- Phonetic Accuracy: Condition 2 (, 95% CI [8.46, 9.48]) > Condition 3 (, 95% CI [7.56, 9.28]) > Condition 1 (, 95% CI [6.80, 7.92])

- Grammar Accuracy: Condition 2 (, 95% CI [9.50, 10.10]) > Condition 1 (, 95% CI [9.24, 9.92]) > Condition 3 (, 95% CI [6.55, 8.95])

- Lexical Accuracy: Condition 2 (, 95% CI [9.00, 9.88]) > Condition 1 (, 95% CI [8.42, 9.72]) > Condition 3 (, 95% CI [7.36, 9.24])

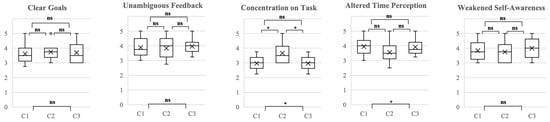

The results of Shapiro–Wilk Test () shows our collected data follow the normal distribution. Results of the repeated measures one-way ANOVA (Figure 6) indicated the following:

Figure 6.

Results of objective learning performance scores in online teaching. C1 is Real Teacher Identity; C2 is Self Identity; C3 is Idol-Inspired Identity. ∗ indicates ; indicates ; ns indicates non-significant difference; + indicates marginal difference.

- Significant differences in mean scores across conditions (, , ). Multiple comparisons revealed a significant difference between Condition 2 and Condition 3 (), demonstrating that self-identity personalization significantly enhanced overall learning outcomes.

- A marginal differences in lexical accuracy (), suggesting that vocabulary learning may be potentially influenced by teacher identity and more dependent on memory-based strategies.

- Significant differences in grammar accuracy (). Multiple comparisons showed a significant difference between Condition 2 and Condition 3 (), indicating that self-identity conditions particularly support complex cognitive tasks requiring deep processing.

- Significant differences in phonetic accuracy (). Multiple comparisons indicated a significant difference between Condition 2 and Condition 1 (), suggesting that self-identity reduces psychological barriers to oral practice.

- Significant differences in fluency (), indicated a significant difference between Condition 2 and Condition 1 (), as well as Condition 2 and Condition 3 (), suggesting that self-identity can encourage oral practice of the learner.

4.5.2. Flow State Analysis

Initial observations of descriptive orderings based on observed means rather than confirmed effects across conditions:

- Clear Goals: Condition 1 (, 95% CI [4.50, 5.02]) > Condition 2 (, 95% CI [4.18, 4.88]) > Condition 3 (, 95% CI [4.22, 4.78])

- Unambiguous Feedback: Condition 2 (, 95% CI [4.70, 5.00]) > Condition 1 (, 95% CI [4.08, 4.82]) > Condition 3 (, 95% CI [4.09, 4.61])

- Concentration on Task: Condition 2 (, 95% CI [4.54, 5.06]) = Condition 1 (, 95% CI [4.54, 5.06]) > Condition 3 (, 95% CI [4.40, 5.00])

- Altered Time Perception: Condition 2 (, 95% CI [2.62, 4.58]) > Condition 1 (, 95% CI [2.42, 4.18]) > Condition 3 (, 95% CI [2.17, 3.83])

- Weakened Self-Awareness: Condition 2 (, 95% CI [4.64, 5.02]) > Condition 1 (, 95% CI [4.01, 4.69]) > Condition 3 (, 95% CI [3.90, 4.66])

The results of Shapiro–Wilk Test () shows our collected data follow the normal distribution. Results of the repeated measures one-way ANOVA (Figure 7) indicated the following:

Figure 7.

Results of subjective flow-based assessment in online teaching. C1 is Real Teacher Identity; C2 is Self Identity; C3 is Idol-Inspired Identity. ∗ indicates ; ns indicates non-significant difference.

- Significant effects of teacher image on unambiguous feedback (, , ) and weakened self-awareness (, ), key dimensions associated with intrinsic motivation and autonomous engagement. Multiple comparisons revealed significant differences between Condition 2 and Condition 3.

- No significant effects of teacher image on clear goals (, ), concentration on task (), or altered time perception ().

4.6. Analysis

4.6.1. Objective Learning Performance

Across all evaluation dimensions, learners in Condition 2 (Self Identity) obtained higher scores than those in the other conditions. While this pattern is consistent with Hypothesis 1, the mechanisms underlying this effect should be interpreted cautiously. One plausible interpretation is that visually personalized teacher representations may increase learners’ sense of familiarity or subjective comfort, which could facilitate engagement in some learning activities. This interpretation aligns with perspectives in motivation and learning research suggesting that perceived relevance or personal connection can support learner involvement, although the present data do not allow strong conclusions about underlying psychological processes.

Learners in Condition 3 (Idol-Inspired Identity) showed the lowest performance in most dimensions except phonetic accuracy, diverging from Hypothesis 2. Several possible explanations may be considered, though they remain speculative. For instance, highly stylized or attention-capturing representations may influence learners’ distribution of attention during instruction, which could in turn affect their focus on task-relevant information. Alternatively, differences in perceived instructional authority or credibility of the teacher image could shape how learners respond to feedback or explanations. These possibilities warrant further empirical investigation rather than firm interpretation at this stage. It is also notable that Condition 3 displayed substantially higher score variance. This suggests that responses to idol-based representations may differ across individuals, with some learners appearing to benefit while others perform less effectively. Such heterogeneity indicates that externally appealing identities may not operate uniformly across learners and may pose challenges for consistent instructional design. Lexical accuracy did not differ significantly across conditions. This pattern suggests that vocabulary learning in this context may be influenced less by teacher identity and more by factors such as repetition, memory strategies, or task structure. Teacher image characteristics appear to play a relatively limited role in this aspect of performance. For phonetic accuracy, learners in Condition 2 achieved the highest mean score with the smallest variance. One possible explanation is that personalized teacher images may reduce learners’ anxiety or performance pressure during oral practice, allowing them to engage more consistently in pronunciation tasks. However, as no direct measures of affect or anxiety were collected, this interpretation should be taken as a tentative hypothesis. The relatively higher phonetic performance in Condition 3 compared to the traditional teacher condition may similarly reflect increased attention to visual cues such as mouth movements, though the current data do not allow us to confirm the specific processes involved.

4.6.2. Subjective Flow State

Except for the clear goals dimension, the self-identity condition yielded higher flow ratings, which is broadly consistent with Hypothesis 1. Significant differences were found between Condition 2 and other conditions in unambiguous feedback and weakened self-awareness, both of which are associated with subjective engagement in learning tasks. One possible interpretation is that personalized visual representations may make the interaction feel more familiar or less socially evaluative, potentially supporting learners’ receptivity to feedback. This interpretation remains tentative, as the study did not directly measure the proposed mediating factors.

Learners in the idol-inspired condition reported the lowest flow levels, consistent with their lower academic performance. This may suggest that visually prominent or stylized representations can shift learners’ attention away from task-relevant cues, thereby affecting their ability to maintain sustained engagement. However, this interpretation should be considered preliminary, and future research could more systematically examine how different types of visual personalization affect attentional allocation and perceived task involvement.

For the clear goals dimension, learners in Condition 1 (Real Teacher Identity) showed slightly higher ratings, although not significantly different from Condition 2. One possibility is that traditional teacher images carry familiar associations with instructional roles, making goal-setting cues easier to interpret. This finding suggests that different identity representations may support different aspects of the learning experience, and that a context-adaptive personalization strategy could be explored in future work.

5. Discussion

5.1. Response to RQ1: Teacher Identity and Sustainable Learning Outcomes

The results indicate that teacher identity, particularly when embodied as a learner’s own face (Condition 2), positively influences both oral performance and flow state dimensions such as concentration, which are key indicators of sustainable learning engagement. While objective learning outcomes (fluency, phonetic accuracy, and lexical accuracy) showed limited significant differences across conditions in Experiment 1, the self-condition consistently yielded the highest mean scores and demonstrated significant advantages in Experiment 2’s more interactive, sustained learning context. This aligns with Self-Determination Theory, which posits that intrinsic motivation, foundational to lifelong learning, is heightened when learners perceive tasks as self-relevant [47]. The self identity likely served as a cognitive anchor, triggering the Self-Reference Effect and enhancing attentional focus on language material while fostering the learner autonomy essential for sustainable education.

From a sustainable education perspective, these findings have important implications. The self-identity condition’s enhancement of intrinsic motivation and concentration suggests that personalized digital human teachers can cultivate self-directed learning capacities without requiring proportional increases in human instructor resources. This scalability is critical for addressing educational equity challenges in resource-constrained contexts. By fostering psychological ownership of the learning process, self-identity avatars may support the transition from externally-motivated to autonomously-regulated learning, a hallmark of sustainable educational outcomes.

However, the domain-specific nature of these effects warrants careful consideration. Self-identities primarily benefited tasks requiring deep cognitive engagement (e.g., concentration, grammatical accuracy) rather than those dependent on precise imitation (e.g., phonetic accuracy in Experiment 1). This distinction suggests that sustainable personalization strategies must be tailored to learning objectives: self-identity avatars may optimally support comprehension and autonomous practice phases, while traditional teacher identities may better serve modeling and demonstration phases requiring authoritative guidance.

The idol condition (Condition 3) consistently underperformed expectations, potentially due to imbalanced cognitive resource allocation toward the teacher’s image rather than learning content. Learners may also have questioned the pedagogical authority of non-traditional identities, reducing trust and undermining the psychological safety necessary for sustained engagement. The high variance in this condition indicates polarized responses, highlighting risks of distraction-based disengagement that could undermine long-term learning persistence. From a sustainability standpoint, this suggests that celebrity-like avatars may inadvertently create engagement patterns dependent on external appeal rather than intrinsic interest in the learning content itself, a trajectory incompatible with lifelong learning goals.

Together, these findings imply that teacher identity design for sustainable online education must carefully balance psychological familiarity (to foster intrinsic motivation), perceived authority (to establish trust and clear goals), and task-specific relevance (to optimize cognitive resource allocation). Such balanced approaches can create scalable, personalized learning environments that cultivate learner autonomy while maintaining educational effectiveness across diverse populations.

5.2. Response to RQ2: Digital Humans as Scalable Personalization Tools

Digital human technologies demonstrated substantial potential to personalize teacher appearance in resource-efficient ways that enhance psychological engagement and support sustainable education goals. The self-condition’s superiority in concentration and overall performance validates the hypothesis that identity-specific visual stimuli can deepen learner immersion while requiring minimal additional technological resources beyond initial system development. This scalability is crucial: once developed, digital human systems can serve unlimited learners with personalized experiences at marginal costs approaching zero, dramatically improving the cost-effectiveness ratio compared to human-delivered personalized instruction.

From a sustainable education perspective, this technology addresses three critical challenges. First, it democratizes access to personalized instruction, traditionally available only in resource-rich educational settings. By enabling automatic adaptation of teacher appearance to individual learner characteristics, digital humans can reduce educational disparities without requiring proportional increases in qualified human instructors, a scarce resource in many contexts. Second, it supports learner autonomy by creating psychologically resonant learning experiences that foster intrinsic motivation and self-directed engagement. Third, it enables continuous learning beyond formal instructional hours, as learners can access personalized digital teachers asynchronously and repeatedly, supporting the flexible, self-paced learning essential for lifelong skill development.

To operationalize real-time adaptation for maximum sustainability impact, future systems could integrate physiological or behavioral metrics (e.g., eye-tracking, response latency, interaction patterns) to dynamically adjust teacher identity based on real-time learner engagement indicators. For instance, systems might transition from neutral teacher avatars to self-identity representations during detected low-concentration phases to re-engage distracted learners, then return to authoritative teacher identities when providing corrective feedback requiring perceived expertise. Such adaptive approaches could optimize both immediate learning effectiveness and long-term motivation maintenance.

Additionally, hybrid personalization strategies, such as blending self-identity features with authoritative teacher traits, or gradually morphing between identities based on learning phase, might mitigate the “celebrity effect” observed in the idol condition while maintaining both psychological resonance and pedagogical trust. These approaches warrant investigation as potentially optimal configurations for sustainable, scalable personalized learning environments.

Importantly, the resource efficiency of this approach extends beyond direct instructional costs. By enhancing engagement and intrinsic motivation, personalized digital humans may reduce dropout rates and improve learning persistence, critical sustainability metrics often overlooked in traditional educational assessments. Future research should examine long-term retention, continued learning motivation, and transfer of self-directed learning skills to assess the full sustainability impact of identity-adaptive digital human teachers.

5.3. Response to RQ3: Flow State as a Sustainable Learning Indicator

The study confirms that flow dimensions, particularly concentration and weakened self-awareness, serve as meaningful indicators of sustainable learning engagement and can be effectively incorporated into online educational assessments. Learners in the self-identity condition reported significantly heightened flow states, suggesting that identity-driven personalization fosters the deep psychological immersion associated with intrinsic motivation and autonomous learning, core competencies for lifelong education. This finding validates flow theory as a valuable framework for assessing not merely immediate learning effectiveness, but the quality of psychological engagement that predicts sustained learning beyond formal instruction.

From a sustainable education perspective, flow states represent a critical intermediate outcome linking immediate instructional experiences to long-term educational trajectories. Unlike traditional metrics focused solely on academic performance, flow indicators capture learners’ intrinsic enjoyment, sense of control, and absorption in learning activities, psychological states that predict continued voluntary engagement with learning beyond course completion. By demonstrating that personalized digital human teachers can enhance these flow dimensions, this research suggests a pathway to cultivating self-directed learners capable of continuous skill development throughout their lives. The differential effects across flow components indicate that comprehensive assessment frameworks must account for the multidimensional nature of sustainable engagement. Traditional teacher identities maintained advantages in establishing clear goals, likely due to their perceived authority and alignment with learners’ educational schemas. This suggests that different teacher identity configurations may optimally support different aspects of sustainable learning: authoritative identities for goal-setting and structure provision, personalized identities for intrinsic motivation and autonomous engagement. Future educational systems should leverage these complementary strengths through context-adaptive identity switching.

5.4. Limitations and Future Directions

Sample Size and Generalizability Constraints. A limitation of this study concerns the small sample sizes employed in both experiments (N = 9, N = 12). While the within-subject design provided some statistical efficiency advantages, these samples remain modest by conventional standards and constrain the confidence with which findings can be generalized. The significant effects we observed for self-identity on oral performance and specific flow dimensions exhibited medium-to-large effect sizes within our sample. However, we emphasize that these results require replication with substantially larger and more diverse samples before definitive conclusions can be drawn regarding the educational efficacy of identity-adaptive digital human instructors. The present findings should be interpreted as exploratory evidence suggesting potential pedagogical value of self-referential personalization, rather than as conclusive demonstrations. The limited sample size constrains both statistical precision and generalizability across learner populations. Future research employing adequately powered samples is essential to establish whether the observed patterns represent robust, replicable phenomena or sample-specific results. Moreover, the homogeneity of our participant pool—Japanese language learners recruited from a single institution limits conclusions about broader applicability. Critical questions remain unaddressed due to these sample constraints. Cross-cultural validation is particularly important, as the effectiveness of self-identity personalization may vary across cultural contexts characterized by different self-presentation norms, face-saving practices, or collectivistic versus individualistic orientations. Similarly, cross-task validation across different language learning activities (e.g., reading comprehension, written production, pragmatic competence) would be necessary to assess whether our findings generalize beyond oral performance contexts. We acknowledge that multi-site collaborative approaches may be necessary to achieve adequate sample sizes and diversity, though such efforts require substantial coordination and resources that were beyond the scope of the present exploratory investigation.

Short Exposure and Lack of Longitudinal Validation. The self-identity condition’s significant enhancement of concentration and weakened self-awareness dimensions suggests potential for sustainable learning engagement. Drawing on established flow-persistence relationships documented across educational contexts [45], we theorize that these immediate psychological benefits may translate into continued autonomous learning behavior. However, direct longitudinal validation of knowledge retention, voluntary practice maintenance, and long-term skill development remains necessary to substantiate these predictions empirically.

Future research should implement multi-wave longitudinal designs tracking participants at 1-month, 3-month, and 6-month intervals to assess outcomes critical for educational sustainability and equity:

- Durable knowledge retention: Delayed post-tests assessing learned vocabulary and grammatical structures to determine whether personalized digital human teachers produce learning persisting beyond formal instruction;

- Continued autonomous learning behavior: Learning analytics capturing voluntary platform access, self-initiated practice frequency, and learner-directed content exploration—behavioral indicators of the self-directed learning capacity essential for lifelong education;