3.1. Theoretical Rationale

To explore the comprehensive impact of green technology innovation, renewable energy consumption, and environmental tax on carbon dioxide emissions, this study has constructed a cross-disciplinary analytical framework that integrates perspectives of technology, energy, and economy. This framework mainly relies on the following three core theories, which jointly explain the internal mechanisms by which different driving factors affect carbon emissions.

Firstly, the theory of technological change and environmental efficiency provides the foundation for this study to examine the role of green technology innovation. This theory emphasizes that targeted technological progress is a key way to enhance environmental performance and resource efficiency [

36]. Specifically, green technology innovation encompasses a series of technologies ranging from improving energy efficiency to carbon capture and storage. Its essence lies in significantly reducing carbon emissions generated by unit economic output or energy consumption through improvements in production processes and the development of low-carbon products and services. Therefore, this theory anticipates that green technology innovation can become the fundamental driving force for achieving deep emission reduction without restricting economic growth.

Secondly, the theory of energy transition provides fundamental support for understanding the role of renewable energy consumption in reducing emissions. This theory states that the structural transformation of the global energy system from being dominated by fossil fuels to being dominated by renewable energy is the core for addressing climate change and achieving sustainability [

37]. The direct substitution of renewable energy sources (such as solar, wind, and hydro power) for carbon-intensive energy sources like coal, oil, and natural gas can significantly reduce greenhouse gas emissions at the source. This transition process is directly linked to the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals, particularly ensuring universal access to affordable, reliable, and sustainable modern energy (SDG 7) and taking urgent action to address climate change and its impacts (SDG 13).

Finally, Pigouvian tax theory serves as the economic foundation for evaluating the effectiveness of environmental taxation policies. This theory posits that by using tax tools to internalize the negative external costs of environmental pollution, it can provide economic incentives for polluters to reduce emissions [

38]. A well-designed environmental tax can guide enterprises and households to adopt cleaner production and consumption patterns through price signals, and may use the collected revenue to fund green technology research and development or for fair transition, thereby forming a virtuous cycle of “innovation—emission reduction” [

39]. However, the full theoretical potential of environmental taxes is highly dependent on specific design details such as tax rate setting, coverage scope, income utilization methods, and coordination with other policies.

Based on the above theoretical analysis, this study proposes the following core hypotheses:

H1: Green technology innovation (GTI) has a significant negative impact on carbon dioxide emissions in OECD countries.

H2: Renewable energy consumption (REC) has a significant negative impact on carbon dioxide emissions in OECD countries.

H3: Under the current prevailing policy framework, the environmental tax (ETAX) has no significant impact on carbon dioxide emissions in OECD countries.

3.2. Empirical Model Building

Considering the afore-discussed theoretical foundations, this extant study proposes a panel model in a multivariate framework to estimate the impact of green technology innovation, renewable energy consumption, and environmental taxes on CO

2 emissions in OECD economies. Importantly, all variables are transformed into natural logarithms to mitigate potential heteroscedasticity. Thus, our proposed method transforms log-linear model in a panel multivariate context specified as follows:

where lnCO

2, lnGTI, lnREC, and lnETAX, respectively, represent the natural logarithm transformations of carbon dioxide emissions, green technology innovation, renewable energy consumption, and environmental taxes. Given the log-linear specification, the coefficients

β1,

β2, and

β3 represent elasticities, indicating the percentage change in CO

2 emissions resulting from a 1% change in the respective explanatory variable, holding other factors constant.

is the error term, while

and

indicate the country cross-sections and time.

In particular, to control for socioeconomic conditions in nations and time-varying factors that may influence changes in the dependent variable, the study incorporates control variables such as income. Thus, the specified model in Equation (2) is extended as follows:

where

is a constant term for the individual cross-sections,

,

and

are the parameter estimates of capturing the effect of green technology innovation, renewable energy consumption and environmental taxes correspondingly,

is

vector of parameters that accounts for the respective effect of the control variables, whereas

is also a vector containing the control variables (economic growth (GDP) and fossil fuel energy consumption (FEC)), where

and

represent individual countries within a panel at a specific time correspondingly and

represents the error term.

Controlling for GDP and fossil fuel consumption is essential to isolate the impact of green policies on CO

2 emissions, as their confounding effects distort findings. GDP fluctuations conflate cyclical economic effects with policy outcomes—expansions increase emissions irrespective of green advancements, while downturns may falsely suggest policy-driven reductions. Furthermore, omitting fossil fuel consumption risks misattributing emission declines to renewables when they are actually driven by fluctuations in fossil fuel use or prices, inducing omitted variable bias given the interdependencies within energy systems [

40]. Environmental tax efficacy further depends on economic/energy contexts [

41], while rebound effects necessitate GDP controls to quantify green innovation’s net impact. Fossil fuel controls prevent overstatement of renewables’ displacement effects [

42], collectively mitigating biases and clarifying decarbonization pathways.

3.3. Estimation Approach

Prior to estimating the effect of environmental tax, renewable energy consumption, and green technology innovation on CO

2 emissions whilst controlling for economic growth and fossil fuel energy consumption, the following standard panel econometric procedures are carried out steadily. First, the existence of cross-section CSD is examined. CSD arises when unobserved common factors such as global economic shocks, shared policies, or spatial spillovers induce correlations in residuals across units (countries), violating independence assumptions. Ignoring this can lead to biased standard errors and invalid inferences. Based on this, the Pesaran CSD (PCSD) test is employed to examine the issues relating to cross-sectional dependence. The test statistics of the PCSD test were derived from the pairwise correlation coefficients of residuals obtained from individual regressions for each cross-sectional unit. Specifically, for a panel with

cross-sectional units and

periods, the PCSD test calculates the average of all pairwise correlations of residuals between units

and

(denoted as

), then standardizes this average to form a statistic that asymptotically follows the standard normal distribution under the null hypothesis of no cross-sectional dependence. The test equation is formulated as follows:

where

is the sample of the correlation coefficient between the residuals of the units

and

. Under the null hypothesis of cross-sectional independence, CSD converges to a normal distribution with mean 0 and variance 1. A significant PCSD test value rejects the null hypothesis, indicating the presence of cross-sectional dependence.

Bearing in mind the potential existence of cross-sectional dependence in panel data settings, it would not be econometrically meaningful to use conventional unit root tests such as the ADF test, PP test and IPS test, since they do not produce robust and reliable outcomes in the presence of cross-sectional dependence issues. In line with this, the study employs a second-generation unit root test by Pesaran [

43] known as the cross-section Im, Pesaran and Shin (CIPS) test, in the second phase of the estimation procedure to examine the stationarity properties of the study variables. The CIPS explicitly models dependence by augmenting the standard Dickey–Fuller (DF) regressions with cross-sectional averages of lagged levels and the first differences in the series. For a panel dataset with

cross-sectional units (countries) and

time periods, the CIPS test estimates the cross-sectional augmented DF regression for each unit

:

where

is the first difference in the variable

,

is the lagged level of

,

is the cross-sectional average of lagged first differences,

is the cross-sectional difference in the lagged levels, whereas

,

and

are unit-specific coefficients. The inclusion of

and

accounts for common factors affecting all units, mitigating cross-sectional dependence. The CIPS statistics are, thus, estimated as the cross-sectional averages of the

statistics (

) for the null hypothesis of

(unit root exists) from each cross-section augmented DF regression:

Having confirmed the integration order of the utilized variables, the study further examined the existence of cointegration or long-run liaison among variables within the proposed empirical model using the Westerlund [

44] (WE) cointegration test. The test employs an error correction model framework. Thus, for a panel with

cross-section units and

time periods, the error correction model for unit

is specified as follows:

where

captures the cointegration relationship (speed of adjustment towards the long-run equilibrium) with

being the lagged dependent variable,

the lagged independent variable(s),

the vector of cointegration coefficients,

represents the lags of the dependent variable’s first difference, capturing the short-term effect and

denotes the lags of the independent variable(s)’s first difference, capturing the short-term dynamics of

’s. The test computes four statistics: two group-mean statistics (

and

), which explore the alternate theory of cointegration of the whole group and two-panel statistics (

and

), which, on the other hand, note that at least one cross-section of the panel is cointegrated. The group-mean statistics aggregate individual unit results, with

averaging the

statistics of

and

averages normalized adjustment speeds as follows:

where

is the standard error of

. The panel statistics pools data across units, with

and

derived from pooled estimates of

as follows:

The WE cointegration test relies on the null hypothesis, , which posits no cointegration across units, while the alternative , suggests cointegration in at least one unit. Critical values are generated via a sieve bootstrap procedure to address cross-sectional dependence. This method resamples residuals while preserving their cross-unit correlation structure, ensuring robustness to shared trends or shocks.

Further, heterogeneity -where parameters vary across cross-sectional units -reflects divergent responses to variables due to institutional, cultural or economic differences. Specifically, the presence or absence of slope heterogeneity leads to the selection of an appropriate estimator for estimating the slope coefficients with respect to the variables specified in the study’s proposed model. Thus, to determine whether slope heterogeneity is an issue of concern, the Pesaran and Yamagata [

43] (PY) test is employed prior to finally estimating the relationship among the study variables. The PY test extends Swamy’s method by addressing small-sample bias and cross-sectional dependence. Under the null hypothesis

, slope coefficients are identical across units (homogeneity), while the alternative allows heterogeneity (

). The test employs two test statistics, which include the delta tilde (

) and adjusted delta tilde (

) which modify Swamy’s statistic to correct for bias in finite samples. The statistics are thus estimated as follows:

where

represent the unit-specific ordinary least square estimates,

is a weighted fixed-effects pooled estimator,

is the matrix of regressors,

is the within-group matrix,

is the error variance estimate for unit

,

is the number of regressors,

and

are cross-sectional and time dimensions, and

is the Swamy’s original statistic. Under the null hypothesis,

and

converge to a standard normal distribution for large

and

. Rejection of the null hypothesis thus implies slope heterogeneity, necessitating the implementation of estimators like the AMG, CCEMG, just to mention a few.

Addressing cross-sectional dependence and slope heterogeneity, this study estimates cointegration between CO

2 emissions, environmental taxes, and renewable energy—controlling for GDP and fossil fuels—using AMG [

45] and CCEMG [

46]. Unlike traditional FE methods imposing homogeneity assumptions, AMG incorporates common dynamic effects (θₜ), capturing unobserved time-varying factors across units, thereby correcting for heterogeneity biases while averaging unit-specific coefficients. This approach ensures robust estimation where conventional methods fail. The AMG model for unit

at time

is thus expressed as follows:

where

is the dependent variable,

is a vector of independent variables,

is a unit-specific intercept,

represents unit-specific slopes, and

is a common term (often proxied by the cross-sectional average of

or time dummies). By specifying or reformulating Equation (10) with the study variables, the AMG model to be estimated in this study thus becomes

From Equation (11), the AMG estimates for the coefficients or parameters with respect to the explanatory variables and control variables are thus determined by using the cross-sectional means of

’s and

’s as follows:

where

and

are the AMG estimators of the explanatory variables of interest and control variables for each cross-sectional unit in the panel,

and

are the parameter estimates concerning the explanatory variables of interest and the control variables utilized in this study.

On the other hand, the CCEMG estimation method accounts for cross-sectional dependence by including cross-sectional averages of the dependent and independent variables as proxies for unobserved common factors. Using the cross-section averages of the regressors together with those of the response variable, the CCEMG approach approximates latent common factors, allowing the model to filter out cross-unit correlations. Thus, for a cross-sectional unit

at time

, the CCEMG model is theoretically expressed as

where

and

are the cross-sectional averages of the response and regressors at time

, whereas

and

respectively denotes specific unit coefficients of the cross-sectional means of the response and explanatory variables. By specifying the theoretical model in Equation (14) with the study variables, the CCEMG model is empirically expressed as follows:

where

,

,

,

and

represents the cross-sectional averages

,

,

and

together with the control variables

and

is the slope coefficient of the

control variable.

Similar to the AGM estimator, the CCEMG estimates for the coefficients or parameters with respect to the explanatory variables and control variables are thus determined by the following relations:

where

and

are the CCEMG estimators for the explanatory variables and control variables for each cross-sectional unit in the panel,

and

are the parameter estimates concerning the explanatory variables of interest and the control variables utilized in this study.

Since the recommended estimation approaches (AMG and CCEMG) only give elasticity inference, the direction of causal relationships between the employed study variables is examined by employing the panel causality approach of Dumitrescu and Hurlin [

47] (henceforth, DH test). Unlike conventional tests assuming homogeneous causality, the DH test explicitly accommodates heterogeneity—allowing causal relationships to exist in some cross-sectional units but not others—making it ideal for contexts where structural or institutional differences cause varying effects across economies. The test implements a panel vector autoregressive (VAR) framework to determine if lagged values of variable X improve predictions of variable Y beyond Y’s own history, thereby robustly identifying causal pathways amid unit-specific variations. Thus, for each cross-section unit

and time

, the model is specified as

where

represents unit-specific fixed effects,

and

are the lag coefficients specific to unit

and

is the error term. The null hypothesis posits that

does not Granger-cause

in any unit

, while the alternative hypothesis allows for causality in at least some units

. This formulation explicitly acknowledges heterogeneity as a causal effect (

) as being permitted to differ across units. The test statistics are constructed in two stages. First, individual Wald statistics

are computed for each unit

to test the null hypothesis

. These statistics are then averaged across units to form the panel statistic

. To address cross-sectional dependence and ensure asymptotic normality, the standardized statistic

is derived, where

is the number of cross-sectional units, and

is the number of lags. Under the null,

converges to a standard normal distribution, enabling hypothesis testing.

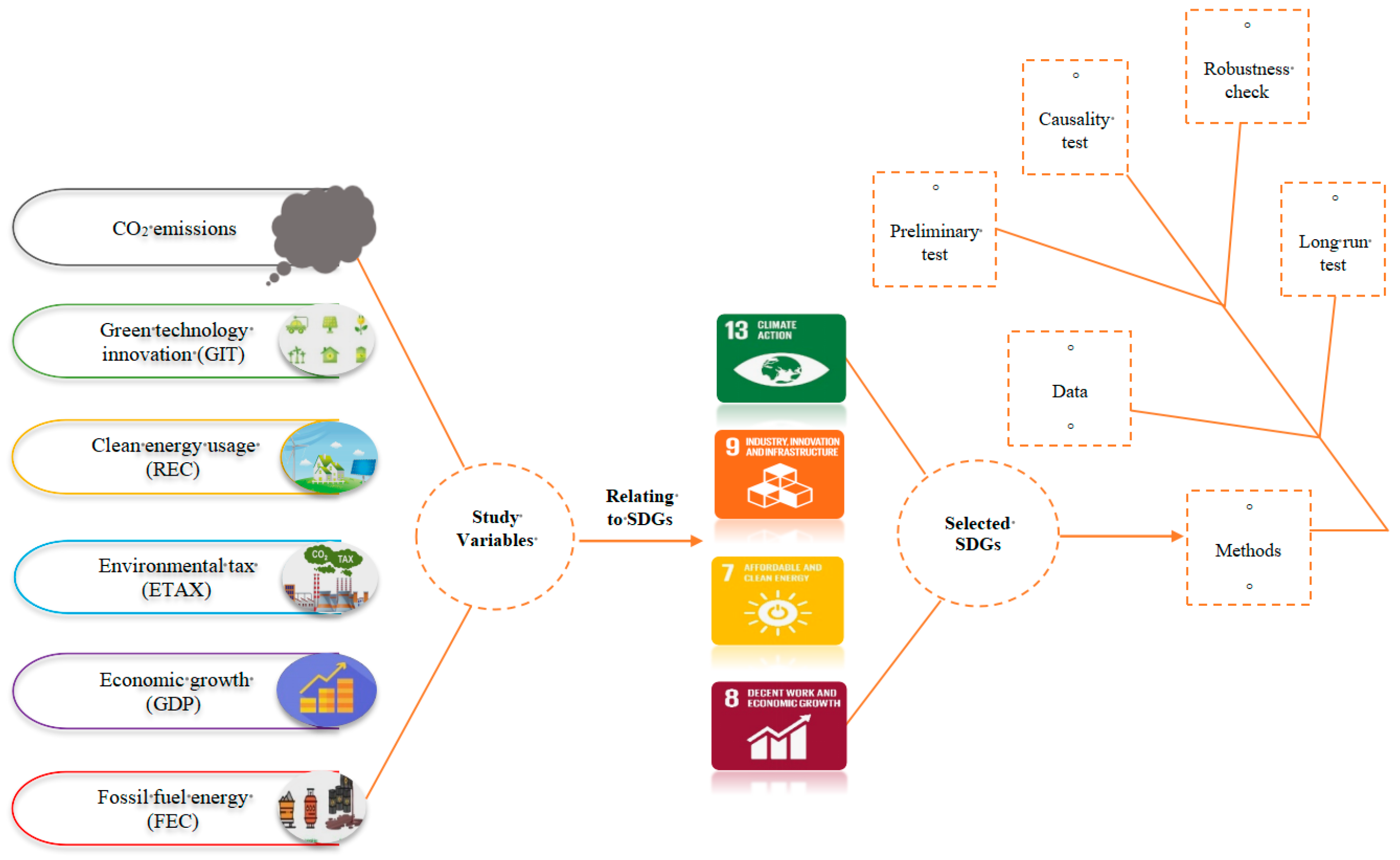

In summary, the analytical roadmap is pictorially illustrated in

Figure 3 as

3.4. Data and Descriptive Analysis

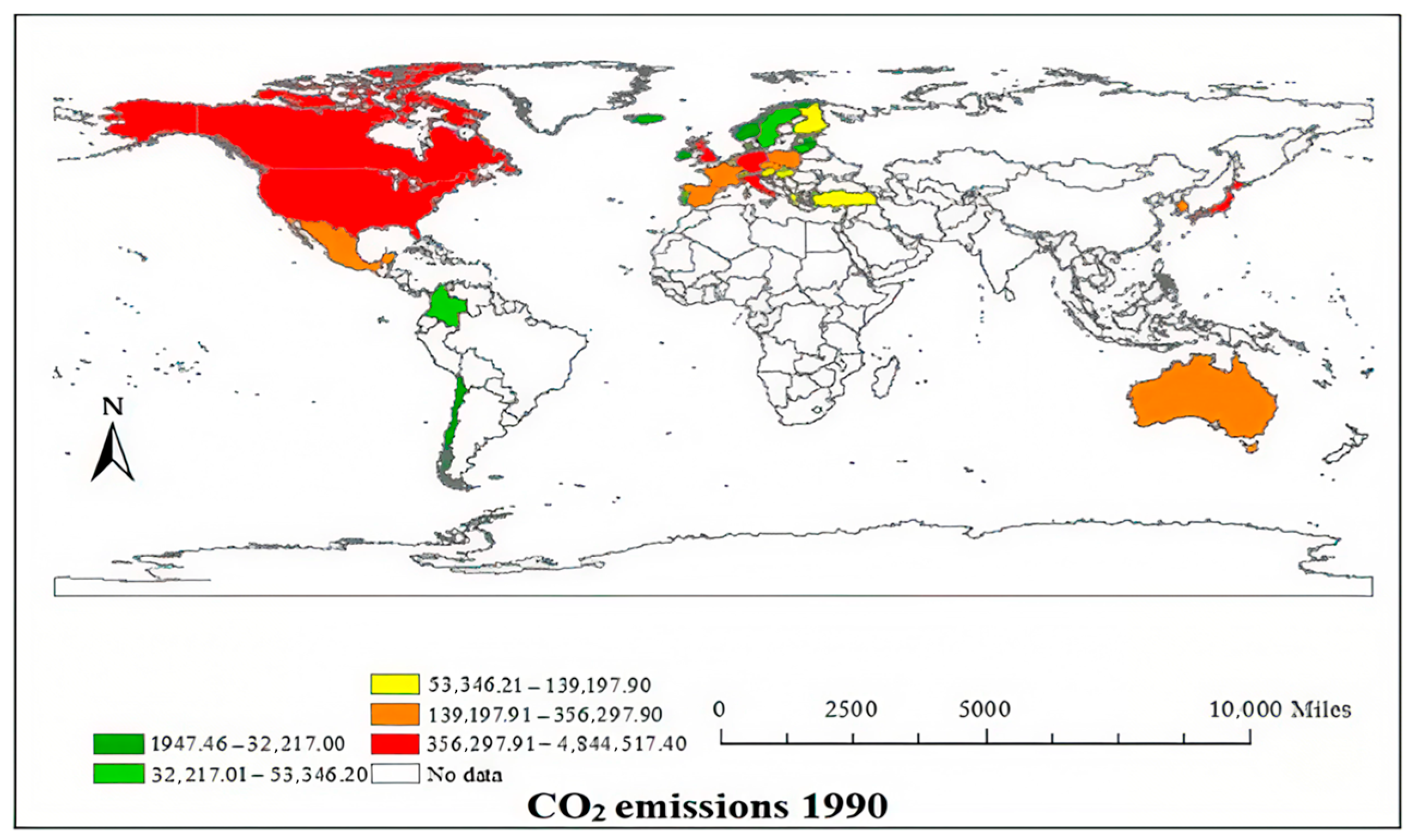

Based on data availability, this study uses annual data of 35 OECD economies from 1990 to 2019. Data on green technology innovation and environmental taxes are sourced from the OECD statistics database. Renewable energy consumption, fossil fuel energy consumption, and GDP were sourced from the World Development Indicators (WDIs). Based on previous literature [

48,

49,

50], the selected variables are based on the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (7, 8, 9, and 13):

Carbon dioxide emissions (CO2): The total amount of carbon dioxide emissions (in thousands of tons) sourced from the World Development Indicators (WDI) database. This indicator is a direct result variable for measuring the impact of human activities on climate change and is the core dependent variable for evaluating the ultimate effectiveness of various emission reduction policies and technologies.

Green Technology Innovation (GTI): The “number of environmental-related technology patents” from the OECD statistical database is used as the proxy variable. Patent data is an internationally recognized indicator for measuring the output of technological innovation and the stock of knowledge, and can effectively capture the invention and creation activities in the green technology field. This indicator operationalizes the core concepts in the “Theory of Technological Change and Environmental Efficiency”, and is used to test the contribution of green knowledge creation to emission reduction.

Renewable Energy Consumption (REC): Utilizing the “percentage of renewable energy consumption in the total final energy consumption” from the World Development Indicators (WDI) database. This indicator directly quantifies the extent to which clean energy replaces traditional fossil fuels, and is the core metric for measuring the process of the energy system’s transition towards a low-carbon model.

Environmental Taxes (ETAX): Utilizes “environmental taxes revenue” from the OECD statistical database. It is usually measured as a percentage of GDP or total taxes for cross-country comparisons. This indicator aims to capture the overall policy intensity of countries in using price-based tools for environmental regulation.

GDP: The per capita GDP (in constant 2010 US dollars) is used as a control variable to account for the fundamental impact of economic development stage, economic scale, and related energy demand levels on emissions.

Fossil Fuel Energy Consumption (FEC): The “percentage of fossil fuel energy consumption in the total final energy consumption” (WDI) is used as a control variable to control the carbon intensity of the energy structure itself. This is crucial for isolating the effect of renewable energy (REC) substitution, avoiding mistakenly attributing the decline in fossil fuel energy consumption due to market or technological factors to policy variables.

Table 1 contains definitions of the variables and data sources.

Table 2 summarizes descriptive statistics for the study variables using their respective means, median, maximum and minimum values, standard deviations, skewness and kurtosis, Jarque–Bera test, and Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) outcomes. Specifically, the mean values indicate the average level of each variable across 1050 observations, with CO

2 emissions averaging 11.531, GTI at 4.168, REC at 2.375, ETAX at 0.766, FEC at 4.248, and GDP at 10.111. Further, the maximum and minimum values highlight the range of variations within the dataset. Evidently, CO

2 emissions range from 7.528 to 15.569, GTI varies significantly from −1.722 to 9.429, and ETAX shows a particularly large spread from −4.200 to 1.681, indicating substantial differences in environmental tax policies. The standard deviation values also suggest the extent of variability in each variable, with GTI exhibiting relatively higher variability at 2.380, reflecting the unbalanced development of green technology innovation; while ETAX and FEC show lower dispersion at estimated values of 0.471 and 0.386, respectively. Overall, the standard deviation suggests that while some variables, such as GTI, have substantial fluctuations, others, like ETAX and FEC, display more stability within the dataset.

On the other hand, the median values are close to their respective means, indicating that most variables have approximately symmetric distributions. However, the skewness and kurtosis values of ETAX and FEC show that their distributions deviate from normality (negative skew, high kurtosis), and the Jarque–Bera test further confirms the non-normality. These distribution characteristics suggest that there may be cross-sectional heterogeneity in the data, which needs to be considered in the subsequent modeling. The VIF values are all below 5 (the maximum is 2.29), indicating that severe multicollinearity is not present among the explanatory variables. This supports the reliability of the subsequent regression estimates, a conclusion further corroborated by the correlation matrix presented in

Figure 4.

Moreover,

Figure 5 presents combined boxplot and violin plots for CO

2 emissions, GTI, REC, ETAX, GDP, and FEC, offering a visual summary of their distributions and dispersion. For CO

2 emissions, the interquartile range indicates a moderate variability in emission levels, with the median positioned centrally, reflecting balanced dispersion. GTI also exhibits a compact interquartile range, suggesting clustered data around the median, which may imply limited but consistent adoption of sustainable technologies. REC also exhibits a similar narrow spread, highlighting regional similarities in OECD economies’ renewable energy usage, although the median levels may reflect modest overall adaptation. Moreover, ETAX displays a tilted distribution, with the median closer to the lower quartile, indicating that most regions in the OECD economies implement relatively low tax policies. Conversely, FEC has a wide interquartile range, underscoring significant variability in reliance on non-renewable energy sources, with the median indicating a moderate overall dependence. GDP finally demonstrates a right-skewed distribution, where the median is closer to the lower end of the scale, indicating economic disparities, as most nations in the OECD community exhibit lower GDP levels. These visual results further emphasize the existence of cross-national heterogeneity.

Figure 6’s scatter plots reveal critical bivariate relationships: CO

2 emissions exhibit a counterintuitive positive correlation with GTI, suggesting innovations may coexist with carbon-intensive processes or exhibit delayed mitigation effects. Conversely, REC shows a clear negative correlation, confirming cleaner energy’s decarbonization role. ETAX displays no discernible trend, indicating that effectiveness depends on enforcement rigor, rate calibration, and complementary policies. FEC demonstrates a strong positive relationship, reinforcing carbon-intensive energy’s environmental impact. GDP exhibits a weak positive correlation, with data dispersion reflecting heterogeneous growth-emissions linkages across economies due to varying efficiency and policies. These visual patterns align with

Figure 6’s correlation matrix, collectively highlighting the complex, variable-specific dynamics governing emission drivers in OECD nations.