Abstract

Tajikistan, a mountainous country in Central Asia, holds considerable potential for the development of ecotourism, particularly through community-based ecotourism (CBE), as a means of enhancing community resilience. The Pamir region, situated in the eastern part of the country, serves as a compelling case study for examining this potential. This study hypothesizes that ecotourism, especially CBE, can contribute to increased resilience among geographically and economically marginalized communities. To evaluate this hypothesis, we pose two guiding research questions: (1) In what ways is ecotourism contributing to community resilience in the Pamirs? and (2) How is CBE being integrated into ecotourism to further promote community resilience? To investigate these questions, 31 in-depth interviews were conducted with individuals directly engaged in the ecotourism sector. Findings indicate that stakeholders acknowledge the conceptual complexity of ecotourism. Regarding the current extent of CBE, the sector is still developing, with support from non-governmental organizations, but with potential for future expansion. Respondents reported that CBE initiatives have contributed to enhanced economic and community stability, increased participation in decision-making processes, and greater awareness of environmental and cultural conservation. These outcomes suggest that ecotourism and CBE contribute meaningfully to enhancing community resilience for participating communities. Nonetheless, several challenges persist, including inadequate infrastructure and insufficient government policy support, which may impede the development of this sector.

1. Introduction

Ecotourism is a well-established global industry and is the fastest-growing sector of tourism [1]. It emphasizes responsible travel to natural areas, prioritizing environmental conservation and supporting local communities’ well-being [2]. While local communities may be involved in leadership or decision-making roles, but such involvement is not always guaranteed [3,4]. Traditionally, top-down leadership models dominate ecotourism [5]. Ecotourism can support conservation and generate economic benefits, yet these benefits are often unevenly distributed among stakeholders [6]. Effective ecotourism management can potentially address the negative impacts of tourism [7]. Countries like Costa Rica and New Zealand demonstrate this by promoting pro-environmental measures and sustainability in the tourism industry [8].

A subset of ecotourism is Community-Based Ecotourism (CBE), in which local communities are the primary stakeholders in planning, managing, and benefiting from ecotourism [9]. The focus of CBE is on combining environmental conservation with community empowerment, cultural preservation, and equitable development [10]. Leadership roles are filled by local communities, often through village organizations or cooperatives [11]. The concept of community is fundamental to CBE, and is central to all aspects, including decision-making, operations, and benefit-sharing [12,13]. In contrast to ecotourism leadership models, CBE best encapsulates bottom-up approaches to community involvement in the development of this sector [14]. Also, unlike ecotourism, CBE ensures that economic, social, and environmental benefits remain within the community [10].

It should be stated that CBE does not always meet these intended outcomes. Empirical studies from Indonesia, Sri Lanka, and Ethiopia demonstrate that limited participation by local communities in Community-Based Ecotourism (CBE) initiatives often result in missed economic opportunities [15,16,17]. These findings underscore the importance of stronger governmental support to enhance local engagement and promote the equitable distribution of CBE benefits [18]. Moreover, several cases reveal persistent inequalities in benefit-sharing among CBE stakeholders. For instance, in China’s Wolong Nature Reserve for Giant Pandas, He et al. [19] found that although rural residents contributed significant time and labor, most of the ecotourism-generated income was retained by the management authorities. A similar pattern was observed in Tanzania’s Amani Nature Reserve, where despite a substantial increase in ecotourism revenue, local residents received only 22% of the total income [18].

In their bibliometric analysis of the Community-Based Ecotourism (CBE) literature, Guerrero-Moreno et al. [9] emphasized the need for increased research in underrepresented geographic regions. They argue that such research is essential for deepening our understanding of how cultural, economic, and environmental contexts influence the implementation and effectiveness of CBE initiatives.

Central Asia remains significantly underrepresented in the literature on Community-Based Ecotourism (CBE). The Pamir Mountains, located in the Central Asian nation of Tajikistan, originally part of the Soviet Union, offer an excellent locale for addressing this gap. Following the collapse of the Soviet Union and the loss of support services to Tajikistan, many Pamiri communities reverted to subsistence livelihoods like agriculture and herding. In recent years, CBE has emerged as a promising strategy for leveraging the region’s unique cultural heritage and natural landscapes to stimulate economic renewal. The development of locally owned tourism enterprises aimed at attracting environmentally conscious visitors is contributing to economic diversification by providing new income opportunities. Within this context, meaningful community participation is imperative.

Ecotourism and CBE offer valuable pathways for enhancing community resilience, particularly in low-income countries and economically marginalized regions within developed nations [20,21]. Magis ([22], p. 401) defines community resilience as the ‘existence, development, and engagement of community resources by community members to thrive in an environment characterized by change, uncertainty, unpredictability, and surprise.’ Cutter et al. [23] further emphasized the importance of pre-existing conditions in shaping a community’s capacity to adapt to change. Such changes may include abrupt socio-economic decline following the withdrawal of external support [24], or post environmental disasters [25]. These disruptions often compel affected communities to seek alternative sources of income to restore and strengthen their resilience. Ecotourism and CBE represent two low-cost and accessible industries that have demonstrated success in various contexts. Examples include marine ecotourism initiatives [26], mountain-based community ecotourism [21], and post-disaster recovery efforts in Japan [27].

The primary objective of this study is to examine strategies used by a low-income nation to adapt after losing socio-economic support from a former governing authority. Tajikistan serves as a pertinent case study, having experienced significant socio-economic disruption following the dissolution of the Soviet Union [28,29,30]. Although this geopolitical shift occurred four decades ago, its repercussions remain particularly pronounced in the country’s most impoverished region, the Pamirs. One notable adaptive strategy emerging in this context is the development of ecotourism, with community-based ecotourism (CBE) playing a pivotal role. To critically assess the potential of ecotourism and CBE in enhancing Pamirs’ community resilience amid constrained external support, it is essential to investigate the scope and nature of local participation in relevant initiatives. We hypothesize that ecotourism, especially CBE, may contribute to increased community resilience among these geographically and economically marginalized communities. To evaluate this hypothesis, we pose two research questions: (1) How is ecotourism building community resilience in the Pamirs? (2) How is CBE becoming integrated into ecotourism to help promote community resilience? To address these questions, we conduct in-depth interviews with a range of tourism stakeholders. These include tour operators, guides, government officials, national park staff, hotel and homestay owners, and local service providers such as cooks. This study is one of few that use qualitative research for the investigation of CBE in Central Asia. Additionally, this study is the first to specifically examine the development of ecotourism and CBE within Tajikistan and the Pamir region.

2. Study Area

2.1. Administrative and Physical Landscape

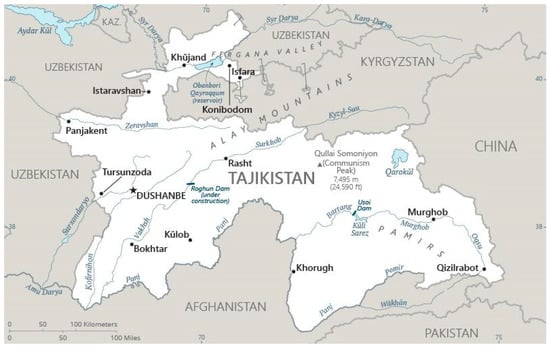

Tajikistan shares borders with China, Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan and Afghanistan (Figure 1). Ninety-three percent of the land area is mountainous, which includes the following mountain ranges: Tyan Shan, the Pamirs, and Alay [31]. The country was formerly part of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) or Soviet Union and achieved independence in 1991. Tajikistan has four administrative regions, and the Gorno-Badakhshan Autonomous Province (here referred to as the Pamirs), the focus of this study, occupies a sizable portion of the country. The Pamirs has seven districts, Darvaz, Vanj, Rushan, Shugnan, Roshtkala, Ishkashim and Murghab. Most are situated in the western part of the territory. The Pamir Mountain Range is part of other notable mountain ranges in the area, such as Tyan Shan, Hindukush, Karakorum, and the Himalayas. Compared to the eastern part of the region, the western area has more precipitation and vegetation. The Murghab district, which encompasses the east part of the region, is more remote and its more extreme climate makes living conditions difficult.

Figure 1.

Tajikistan and its administrative provinces. Source: www.CIA.gov.

2.2. Distinct Attributes of Pamiri Culture

The potential of CBE in the Pamirs derives from its distinctive cultural identity, shaped by prolonged isolation and adaptation to high-altitude environments. Pamiri culture is characterized by distinctive attributes that underscore its profound historical continuity and deeply rooted cultural traditions. Most notable are the preservation of Pamiri languages, which are the only surviving East Iranian languages in Central Asia. These include Shughni, Rushani, Wakhi, and others, spoken primarily in the Gorno-Badakhshan Autonomous Region of Tajikistan [32]. The region also boasts a rich musical heritage, with traditional instruments and styles that differ significantly from those of other Tajik communities [33]. Pamiri cuisine also reflects regional distinctiveness, with traditional dishes such as palov, a rice dish, and piy, a unique milk-based drink is exclusive to the area [34]. The unique attire of the Pamirs is symbolized by the ornate hats that often feature pre-Islamic symbols. The architecture of the Pamiri house, known locally as chid, is another trait of the culture [35]. The house’s symbolic structure, including its five pillars and stepped ceiling, has both cosmological and religious meanings to the Pamiri people [36]. In the Pamirs, vocabulary has coevolved with agriculture (bioculture), creating diverse unwritten languages and a rich mountain culture. This diversity promotes local resilience and has global significance, with over 150 wheat varieties such as the ritual red wheat Rashtak. The ritual makes the end of winter and the arrival of spring [33].

2.3. Pamir’s Legacy of Soviet Control

Understanding Tajikistan’s economic development requires acknowledging its Soviet legacy. Incorporated into the USSR in 1929, Tajikistan, particularly the Pamirs region, became strategically vital during the Cold War, serving as a buffer near the Chinese border [28]. To secure this region, the Soviets invested heavily in infrastructure, while its provision of free healthcare and education supported regional growth [29]. The Pamirs also played a key logistical role during the Soviet-Afghan War [30].

After the Soviet Union collapsed, the region faced severe instability. The sudden loss of centralized support led to food shortages and exposed reliance on imported goods [37]. Weak local institutions and ethnic divisions further complicated recovery [38]. The end of Soviet investment triggered a decline in living standards, pushing many toward subsistence farming as collective systems disintegrated [39,40]. Attempts to privatize agriculture failed to foster self-sufficiency, and economic dependence on other Tajik regions and Russia persisted. Inequality widened, with few communities adapting through livestock economies [41].

Humanitarian aid, especially from the Aga Khan Foundation, helped stabilize the region, though it also reinforced long-term dependency [42]. Socially, the Pamirs saw migration and urban shifts, yet retained high literacy, increasing the potential for a more resilient society. Environmentally poor resource management led to overgrazing, deforestation, and ecosystem stress, exacerbated by outdated Soviet irrigation systems and energy shortages [34]. In summary, any new initiative aimed at fostering economic self-sufficiency in Tajikistan must contextualized within the context of its political past.

3. Traditional Tourism in the Pamirs

Travel along the Silk Road typifies traditional tourism, with historical records indicating its popularity among travelers since the second century BCE [41]. This ancient path traversed the Wakhan Corridor in the southern part of the Pamirs and features a wealth of historical and cultural sites. Among the most significant are the Yamchun (Figure 2), Qah-Qaha, and Abreshim fortresses. Tourists can explore old shrines, petroglyphs featuring engraved images, and a Buddhist Stupa (the footstep of Buddha). These attractions illustrate Zoroastrian and later Islamic influences after the advent of Ismal in the region [42].

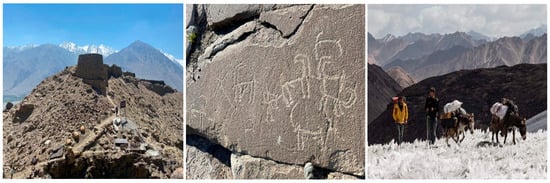

Figure 2.

(Left): Yamchun fortress in Yamg Village, Wakhan Corridor; (Middle): Ancient petroglyphs in Langer Village, Wakhan Corridor; (Right): donkeyman transporting supplies for mountain tourists. Source: Furough Shakarmamadova.

Unfortunately, traditional tourism in the Pamirs is causing the gradual deterioration of the invaluable cultural sites due to the actions of both locals and tourists. Acts of inscribing names on petroglyphs (Figure 2) diminish their historical significance, representing a growing concern in heritage preservation.

The difference between traditional tourism and ecotourism in the Pamirs lies in their focus and approach. Ecotourism focuses on guided tours within the wilderness areas, minimizing human impact on nature. Visitors on those tours do not use facilities requiring energy or excessive water consumption. Additionally, vehicle usage is less frequent, and donkeys are the only means of transportation for carrying tourist loads (Figure 2). In contrast, traditional tourism features cultural tours or “jeep tours” utilizing four-wheel vehicles.

4. Conceptual Framework

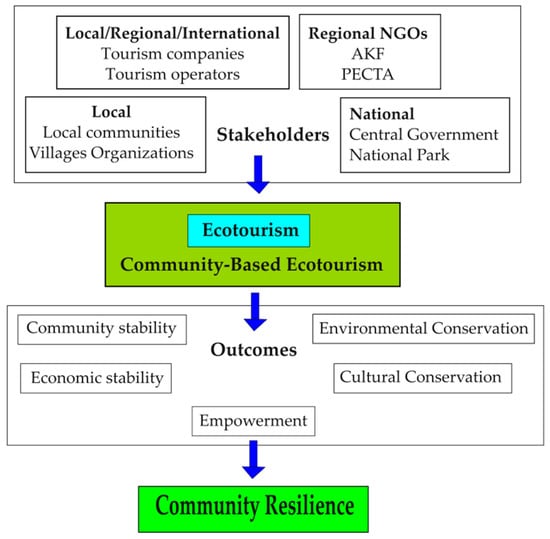

When investigating community resilience, it is essential to identify key stakeholders who play a critical role in examining community-environment interactions [43,44]. Our conceptual model (Figure 3) outlines the primary stakeholders involved in ecotourism—including those relevant to our study of community-based ecotourism (CBE) [45]. The main stakeholders are tour operators, associations, tour businesses, Village Organizations (VO), NGOs (Pamirs Eco-Cultural Tourism Association (PECTA)), the National Park, and the government that collaborate closely with each other. PECTA originated in 2008 through the initiative of the Mountain Societies Development Support Program (MSDSP). Individual tour operators, established through PECTA’s facilitation, are pivotal in regional tourism development, while PECTA actively promotes Pamir exploration through trekking and supports local enterprises. VOs rely on the support of the Aga Khan Foundation (AKF) and the MSDSP, both funding projects to enhance the quality of life in villages beyond tourism. The government regulates the international and local NGOs that oversee CBE programs in the Pamirs. The Tajik National Park (TNP) falls under the control of the government which ensures compliance of the policies and regulations by the users of these parks. There are few government projects supporting the TNP, while PECTA and AKF have made substantial efforts to develop the park.

Figure 3.

The framework of stakeholders and desired outcomes for community-based ecotourism within the encompassing sphere of ecotourism as contributing to community resilience.

This study posits that regions facing socio-economic disruption can strengthen resilience by engaging in emerging industries, particularly ecotourism and its community-based subsector (CBE). Communities in the study region have pursued these avenues in recognition of the intrinsic value of their distinctive cultural heritage and unspoiled natural environment. The proposed framework (Figure 3) situates local stakeholders within these industries and aligns their participation with five core dimensions widely acknowledged as foundational to both ecotourism and CBE: community stability, economic stability, empowerment, environmental conservation, and cultural preservation [46,47,48,49,50,51]. Collectively, these dimensions are essential for the establishment and maintenance of community resilience. Accordingly, this research seeks to evaluate the extent to which ecotourism and CBE contribute to this objective by addressing two guiding questions: (1) In what ways does ecotourism foster community resilience in the Pamirs? (2) How is CBE integrated into ecotourism to advance community resilience? The research questions are addressed through a structured questionnaire survey, designed to systematically capture data relevant to the study’s objectives.

5. Methods

We used key informant interviews as our main instrument for data collection. Stakeholder interviews were conducted with groups identified by Shakarmamadova, based on the author’s prior professional engagement in the region’s tourism sector. This helped ensure the collection of relevant information, thereby mitigating the shortcomings mentioned by Carr and Worth [52]. Further, her familiarity with the sociocultural environment of the study area was instrumental in facilitating open and candid interviews. At the beginning of each interview, participants were advised of their right to withdraw at any time and assured of complete anonymity in their responses. These procedures reflect standard ethical practices in qualitative research and were approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at the University of South Florida.

A total of 31 key informant interviews were conducted, with 10 out of 31 participants being women. We used semi-structured interviews as the primary qualitative data-gathering method. The interviews included members from each stakeholder group: five tour operators, two individuals from PECTA, five guides, three government officials, four individuals from the Tajik National Park (Director and park rangers), two individuals from the Department of Nature Protection, three homestay owners, one mountain cook, one employee of MSDSP, two drivers, one representative from VO, and two foreign consultants who had worked in the Pamirs. Selection criteria emphasized Shakarmamadova’s longstanding engagement in the region, with stakeholder groups aligning closely with findings from prior CBE research in Kazakhstan [45].

In qualitative research, the required number of informants for generating meaningful insights is contingent upon the size and characteristics of the participant pool [53,54]. For instance, Kunjuraman et al. [10] conducted a study on community-based ecotourism (CBE) in Sabah, Malaysia, involving only 10 participants, an appropriate number given the scope and scale of the sector in that context. Similarly, in the Pamirs, where CBE remains a fledgling industry, a sample of 31 participants were drawn from diverse stakeholder groups representing a substantial proportion of those actively engaged in the ecotourism sector. This sample size is therefore considered sufficient to capture a broad range of perspectives and experiences relevant to the study. For example, there are a total of 10 tour operators in the Pamirs region of which five have been interviewed in this study.

Our research activities were limited due to travel restrictions (regional instability), which required interviews to be conducted remotely via phone and Facetime™. While telephone interviews can yield inconsistent results [55], Sturges and Hanrahan [51] highlighted certain advantages, such as broader access to interviewees. The COVID-19 pandemic and other security concerns also challenged in-person interviews. Consequently, virtual data collection methods utilize the Internet and phone platforms like Zoom and WhatsApp [56]. We employed purposive sampling because it provided in-depth information from stakeholders with firsthand knowledge [57] of the ecotourism industry.

To extract and analyze the interview data required for testing our hypothesis, we adopted an approach grounded in Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (IPA) [58]. As a qualitative research method, IPA examines how individuals interpret and make sense of their lived experiences and emphasize the subjective meaning attributed to events, relationships, and phenomena [59]. An IPA framework matrix was employed to examine 53 responses collected through seven structured interview questions, supported by Co-Pilot™ and GPT-5™ artificial intelligence tools. Current literature increasingly recognizes the methodological rationale for employing AI-assisted approaches in thematic analysis [60,61]. The thematic categories applied in this analysis correspond to the outcomes delineated in our conceptual framework. The Python 3.11 script used for data processing and matrix construction is provided in the Supplementary Materials.

To address our first research question (RQ 1), whether ecotourism contributes to building community resilience in the Pamirs, we presented seven targeted questions to the informants (Table 1). Each question was designed to reflect elements of the five key outcomes outlined in our conceptual framework. To address the second research question how CBE is integrated into ecotourism to foster community resilience, we conducted targeted interviews with (1) individuals actively engaged in promoting CBEs and (2) those directly involved in this sub-sector of ecotourism (Table 1). These inquiries were directed toward PECTA officials (RQ 2a) as well as participants from the local communities (RQ 2b).

Table 1.

Research questions (RQ) of this study and their component questions.

As outlined in the Study Area Section, the collapse of the Soviet Union had a profound and lasting impact on the Pamiri economy. To better understand the implications of this geopolitical shift on the development of ecotourism, we conducted interviews with three individuals offering diverse perspectives (RQ 3): a university lecturer from the University of Central Asia, a veteran tourism operator, and a former director of PECTA (Table 1).

6. Results

The presentation of results includes four sections organized around the two central research questions. The first section examines the role of ecotourism in enhancing community resilience within the Pamir region. This includes two subsections: an analysis of stakeholder perceptions of ecotourism, followed by an evaluation using the Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (IPA) framework matrix. The second section explores the integration of CBEs into ecotourism and their contribution to resilience-building efforts. The third section examines the role of the central government and the influence of geopolitical developments in the region on the ecotourism industry. Finally, the fourth section examines obstacles identified by informants that could hinder the full realization of ecotourism and CBE potential.

6.1. Ecotourism Fostering Community Resilience

6.1.1. Definition of Ecotourism

Most respondents utilized a common definition of ecotourism. One respondent, an employee of International Ecotourism Societies (TIES), described the following definition:

“Ecotourism that includes sustainability, traveling to a remote area to be in closer [in] connection with the wild nature and not harming the environment.”(2 July 2022)

This interpretation fits the evolution of ecotourism as defined by Boo [62], Ceballos-Lascurain [63], and Ryan [64], who focus on the protection of the environment and offering employment opportunities for locals. Nevertheless, other definitions of ecotourism arose among the tourism pioneers in the region. They objected to the World Trade Organization (WTO) interpretation of ecotourism that explains ecotourism more as a type of tourism. For example, a tourism expert from Tajikistan stated:

“Ecotourism is not tourism or type of tourism, but rather an ecological approach to tourism. All the tours happening in the Pamirs should have an ecological approach, including the jeep tours, trekking, cultural tours, etc.”(2 July 2022)

This definition incorporates the principles of green and carbon-free tourism. Several initiatives are currently underway to adopt these ecological approaches, supported by grants from NGOs such as PECTA. These initiatives reflect a growing recognition of the importance of environmentally sustainable practices within the tourism sector.

6.1.2. Ecotourism Building Community Resilience

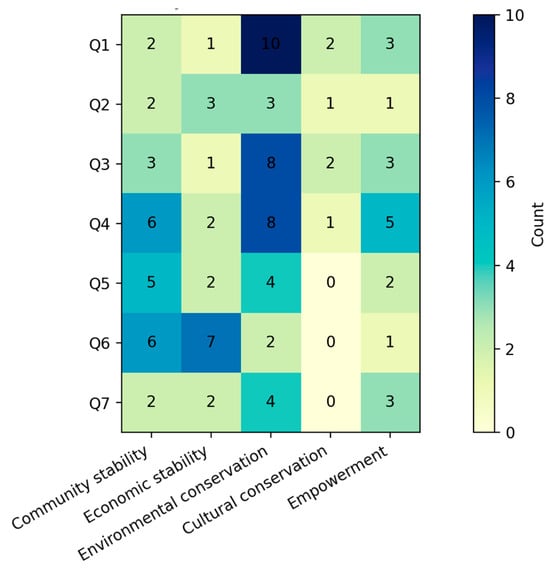

As previously noted, ecotourism has been identified in prior research as a potentially pivotal mechanism for aiding communities in recovering from socio-economic disruptions and environmental crises. Its capacity to promote economic and social stability, support environmental and cultural conservation, and empower local stakeholders contributes significantly to enhancing community resilience. Figure 4 presents the theme salience of five key thematic components that highlight ecotourism’s substantial contribution to community support. Respondents consistently identified environmental conservation as a central element of ecotourism, a view shaped by their lived experiences. Additionally, participants underscored ecotourism’s role in promoting community cohesion and acknowledged its importance in strengthening community resilience.

Figure 4.

Theme salience by question (counts of coded mentions).

Table 2 addresses seven key questions. Analysis of the 53 responses reveals a strong emphasis on themes related to community and economic stability. Environmental and cultural conservation were also noted, albeit to a lesser extent. Understandably, the theme of empowerment received the least attention, due to its abstract nature, which may have resulted in fewer direct references during the interviews.

Table 2.

IPA Framework Matrix (Themes and Evidence).

6.2. Community-Based Incorporating Ecotourism

This analysis investigates strategies employed to promote the potential of CBEs in the region and critically assesses their outcomes across recent decades. This latter component entails an evaluation of the actual scale of the industry. It further examines whether the industry has emerged as a driver of community resilience, primarily through economic advancement and increased environmental awareness.

Promoting Pamiri Community-Based Ecotourism

The CBEs operate in the following manner: tourists initially visit PECTA’s Tourism Information Centre (TIC). Based on individual preferences, PECTA advises tourists on suitable locations and activities. Following this, they are referred to a CBE operating in the district of their choice while ensuring all CBEs benefit equally. When tourists arrive at the destination, the CBE provides them with a team of guides, homestay owners, drivers, porters, cooks, and donkey men to accompany them during their stay. Tours in the Pamirs can range from three days up to one month.

One of the organization’s main goals is to promote a fair income for local tourism providers. It also aims to educate members of CBE in specifically designed educational activities. Another goal is to facilitate communication between the districts to encourage and market their services. As not all tourists go through PECTA, it is common for the CBE members to direct visitors to each other’s businesses. To make CBE more sustainable, PECTA encourages its members to improve their services and develop new activities. Respondents from the Murghab district shared examples of newly developed tourism offerings. These include yak safaris, Marco Polo-themed tours, and camel safaris, which are actively promoted in countries like Germany and Switzerland. In addition to these tours, community members organize events like the Regatta Festival, where participants engage in kite surfing during the first week of September.

Surveyed participants identified poverty reduction as the central purpose of CBEs. They emphasized that ecotourism provides a viable and sustainable means of income for local communities, particularly when visitor inflows to the region are significant (Figure 5). The executive director of PECTA provided a clear definition of the Pamirs’ CBE:

“A chain that helps to unite local communities’ services to boost their businesses through ecotourism. Its main purpose is that the capital can go directly to the local communities. The services CBE’s members can provide are tour operating, guiding, homestay management, porter, etc.”(5 July 2022)

Figure 5.

A homestay in the Pamirs with guests enjoying traditional foods. Source: Furough Shakarmamadova.

Interviewees emphasized the importance of the natural environment in the success of community-based ecotourism (CBE) activities. Guides and Tajik National Park staff described efforts to integrate history, culture, and nature into the visitor experience. The head of the National Park also highlighted a recently developed tour created with support from PECTA, aimed at improving ecotourism offerings in the region. This tour includes the ancient solar calendar in the Shuraly valley, Murghab crater [meteorite site], and the nearby natural geyser; he stated:

“It is fascinating for tourists to reveal the Solar Calendar and the old meteorite site in the middle of nowhere, making it an exceptional experience.”(5 July 2022)

While CBE is a new concept in the Pamirs, its adoption has been successful despite the small numbers of tourists in the region. The development of CBEs is rooted in the region’s longstanding engagement with ecotourism in the Pamirs. Organizations such as PECTA have been helping manage CBE through professional training for tourism stakeholders such as the importance of environmental protection.

6.3. Extent of Pamiri Community-Based Ecotourism

The CBE operates from May to September. During the off season, CBE members work to improve their service facilities while PECTA conducts training sessions. In addition, PECTA and the tour operators visit the International Tourism Board (ITB) in March to participate and promote during an annual exhibition. Currently, CBE members are planning to extend the tourist season into December by introducing winter activities thereby providing opportunities for more employment and income.

Thus far, the CBE has successfully developed ecotourism activities in the seven Pamirs districts. A total of 22 CBE enterprises are operative and new initiatives grow each year with more participants in tourism-related businesses. These include Ishkashim District: Darshai, Vrang, and Langar communities; Rushan District: Jizev, Siponj, Roshorv, Barchidev, Sawnov, and Bopasor villages; Murghab District: Bulunkul, Alichur, Murghab town, Bashgumbez, Jartygumbez, and Karakul; Shughnon District: Khorog town and Bachor village; Roshtqala District: Javshangoz, Rubot, and Tusyon; Darvaz District: Qalai Khumb town; and Vanj District: Poi-Mazor village. The town of Khorog in the Murghab District serves as the central hub for the CBE industry, the reason being that it is the location of the PECTA.

The capacity of CBEs remains underutilized in many Pamiri districts. Despite Darvaz District’s proximity to, and greater interaction with, the more populous and economically developed western region of Tajikistan, only a single CBE enterprise has been established. The Roshtqala District continues to be underexploited, thereby presenting substantial prospects for expansion and growth. Limited marketing and a lack of capacity-building initiatives have hindered its growth, despite the area’s exceptional natural and cultural assets. Roshtqala features stunning valleys that are often excluded from mainstream tourist itineraries. Strategically located, it serves as a gateway to both Murghab and the Wakhan Corridor and offers untapped trekking routes, such as a five-day journey from Bathomdara to Darshay village in the Wakhan Corridor, and a three-day trek from Rubot or Javshangoz through the 5000 m-high Vrang Pass to Vrang village.

Unlike other regions within the Pamirs, Roshtqala is characterized by extensive forested landscapes and abundant natural features, such as historic fortifications and hot springs. The district also stands out for its rich musical heritage, known for both traditional and modern music and songs. Notably, the community religious eulogy performed during funeral ceremonies has survived Soviet atheism thanks to its preservation in the Roshqala district. Traditional handicrafts have also endured, such as Pamiri carpets and the iconic tall boots made primarily from Marco Polo sheep skin. A recent example of local innovation is Pamir Cashmere (Figure 6), a manufacturing initiative whose products are now being exported to Great Britain.

Figure 6.

Pamir Cashmere—wool processing facility and finished product. Source: Furough Shakarmamadova.

6.4. Community-Based Ecotourism: Economic and Environmental Drivers of Community Resilience

This section focuses on evaluating the potential of CBE to serve as drivers of community resilience, particularly through increased income generation and enhanced environmental awareness. By conducting interviews with individuals actively engaged in CBE initiatives, the study seeks to assess the viability of this sector in providing financial support to local communities and sustainably managing their natural resources.

6.4.1. Financial Benefit of CBE

Most tourism stakeholders see ecotourism as the only way for local communities to improve their livelihoods. An excellent example of the potential of CBE is the Bachor village of Ghund Valley where it has been successfully established, enabling most of the population to become involved in ecotourism-related activities. The executive director of PECTA said,

“Bachor village in Ghund Valley is a good example of CBE, where almost 90% of the population are involved in ecotourism; some successfully run the homestay business, some provide guiding and donkeyman services, cook, etc. They additionally have developed horse riding in their village and throughout the trekking. Those horses are accustomed to going through the rocky trails in the mountains. Also, the CBE is managed so that other people could indirectly benefit from it; some people give their donkeys for a seven-day trip without joining them and get 300 dollars a week. This is a good income in Bachor, considered one of the most remote places in the Pamirs. There is a big demand for donkeys for carrying tourists loads throughout the trekking,” He also noncommittally smiled and said, “donkey’s service costs more than human.”(20 July 2022)

Ecotourism brings significant capital to the region; it is a primary or secondary income to most stakeholders (Table 3). Tour operators earn the most from ecotourism. They market the region and CBEs services during the off-season at the ITB. The tourism expert, who is also a tour operator, said,

“Those working in tourism must visit the ITB; without this experience, they would not understand the meaning of tourism and how to deal with it.”(2 September 2022)

Table 3.

Approximate income (USD) from all tourism stakeholders in the Pamirs from CBE.

Table 3.

Approximate income (USD) from all tourism stakeholders in the Pamirs from CBE.

| Type of Service | Daily Income | Monthly Income | Income Per Group/ Number of People | Annual Income |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Porters/ Donkeyman | 30 | 720 | 3750 | |

| Guides | 30–40 | 840–960 | 3750–5000 | |

| Cook | 30 | 720–840 | 4000–5000 | |

| Homestay | 15 | 4500–5000 | 10 people/150 | 22,500 |

| Drivers | 2800 | 700 | 8000 | |

| Hotels | 50 | 10,000–15,000 | 10 people/500 | 75,000 |

| Tour operator | 15,000–200,000 | 8 people/5000 | 50,000–60,000 |

Guides earn comparatively high incomes; however, their work necessitates considerable physical exertion. In the mountains they also serve as cooks for small group tours while larger organized group tours have their separate cooks. Porters also accompany the tours. They receive compensation for both the provision of their services and the management of the donkey.

Homestays are ubiquitous, as they are present in many villages within each district. Their number has increased every year; currently, there are at least 120 homestays in the region. CBE homestays receive institutional support from PECTA and MSDSP, which contributes to the enhancement of service quality. Although some areas remain under-promoted, the majority of districts secure adequate visitor numbers to sustain profitable operations.

Although homestays earn less income than tour operators, these businesses have a lower cost of operation. Homestays “infrastructure” is already in place, and the main cost is the provision of food to visitors. However, these operators can incur one-off costs such as installing toilets or adding bedrooms. In contrast, tour operators have greater outlays such as transportation (vehicles, their maintenance and fuel), food and temporary employee wages but they include these costs as part of the tour packages. Renumeration for independent drivers is based on the kilometers they drive which, for the tourist season, allows for reasonable profits. However, as these vehicles remain in use beyond the designated season, the income the drivers receive from ecotourism is often not enough to sustain them throughout the entire year.

6.4.2. Increasing Environmental Awareness

Respondents were aware of how the CBE tourism model contributed to environmental protection and local community economic development. Engagement in CBE initiatives has heightened environmental awareness among community members, who increasingly recognize that the natural landscape is a key attraction for visitors. This shift in perception has led to a growing appreciation of the environment beyond its economic value. For instance, whereas tourist drivers previously discarded waste from their vehicles, and now routinely collect and dispose of it in garbage bags. The tourism expert stated that:

“As a result, in general very little refuse can be seen along the roads/trails. Clean-ups campaigns are being promoted, and at the military checkpoints, tour operators have trained the soldiers to keep their spots clean, hence they began to control littering in their areas. The experts of tourism think that another focus of tourism stakeholders is promoting awareness through their actions. One example is a teacher of tourism, who over the last decade, began collecting garbage at checkpoints which made people think about the importance of their environment.”(3 September 2022)

Interviews revealed that respondents view ecotourism in the Pamirs as a valuable tool for educational outreach and promoting environmental protection. Those involved in community-based enterprises (CBEs) reported a growing appreciation for their environment. They became engaged in conserving both natural and cultural resources, especially after recognizing their importance to improving their livelihoods. These findings align with research conducted in other countries [65,66,67,68].

6.5. Role of Government and Impact of Geopolitical Shifts on Ecotourism

6.5.1. Government Involvement

The Government of Tajikistan has enacted laws concerning Specially Protected Areas (SPAs), including the Tajik National Park and the Zorkul Nature Reserve. Protected area management in Tajikistan dates to the Soviet era, when designations such as zapovedniki, zakazniki, and national parks were central to biodiversity conservation. The creation of Tajik National Park occurred under the Law on Natural Protected Areas of the Republic of Tajikistan (No. 329, 1996) and the Order of the State Directorate of Natural Protected Areas (No. 147, 2005), in response to ecosystem degradation.

Environmental protection legislation only became feasible after political stability returned after the civil war concluded [69]. Legal frameworks initially mirrored Soviet-era conservation practices. A major milestone came with the passage of Law No. 786 in 2011, titled “Protected Natural Areas,” which marked a significant advancement in the country’s environmental policy. Article 4 of this law declares these natural zones as the exclusive property of the state and outlines their legal, organizational, and economic foundations. Additionally, Article 18 allows citizens to use these protected areas for various purposes, including recreation, health, cultural activities, and ecotourism.

When asked about the importance of environmental laws and regulations, most respondents from the environmental sector emphasized the need for strong legal protection. Tourism stakeholders noted that although the region currently receives few foreign visitors, the development of ecotourism policies is essential to manage potential future impacts. Government officials interviewed also agreed on the necessity of creating specific policies for ecotourism.

Respondents stressed that while environmental protection policies are important, their effectiveness depends on proper enforcement. According to tour operators, acts causing environmental harm are legally treated as criminal offenses, carrying penalties that vary from suspended sentences to multiple years of imprisonment. Examples of such offenses include the use of explosives for fishing and the poaching of endangered species. According to a tour operator who was formerly working with a nature conservancy:

“Until 2000, government officials were involved in illegal hunting with the Russian army resulting in catastrophic decreases in certain species numbers. We were part of a smaller conservancies team working on the ground in remote areas with locals to protect the area’s wildlife by conducting awareness-raising training on the importance of wildlife protection. Our area is a large territory of the Tajik National Park”.(30 July 2022)

Poaching continues to pose a serious threat to ecotourism in Tajikistan, particularly for tourists hoping to observe mountain wildlife such as the endangered snow leopard (Panthera uncia), Siberian ibex (Capra sibirica), and Marco Polo sheep (Ovis ammon polii) [70,71]. The persistence of poaching is largely linked to subsistence hunting, a traditional livelihood strategy among local populations [72]. For instance, a policy protecting the endangered snow leopard imposes a fine of 330,000 somoni (approximately $30,000 USD) for harming or killing the animal.

Awareness of habitat degradation in Tajik National Park and adjacent protected areas has grown, especially among those with a history of intensive hunting of mountain ungulates. These individuals were among the first to recognize the environmental consequences of their activities. The head of the successful conservancy in Murghab declared:

“I remember going hunting with a Kalashnikov automatic rifle, which allowed me to kill a large number of ungulates just in a matter of minute. However, I am taking significant measures currently to protect those species with my organization. In addition, I cooperate with national and international organizations to protect those species at large scale. For example, we had very effective projects with the American organization “Panther””.(3 August 2022)

Over time, the Tajik government became increasingly conscience of the negative impacts of widespread hunting [72]. In response, the government took steps to eliminate mass hunting. With the introduction and enforcement of the Wildlife Management Regulation (WMR) in the Pamirs during the late 1990s and early 2000s, most respondents believe the regulation has been effective in reducing poaching activities. The success observed can primarily be credited to community-driven initiatives, though in Murghab District, private enterprises played a pivotal role in launching conservation activities.

6.5.2. Impact of Geopolitical Changes on Ecotourism

Respondents attributed the dissolution of the Soviet Union as a catalyst for increased ecotourism engagement. An expert on tourism development in Tajikistan explained:

“During the Soviet era, many people from the region went abroad to study and always returned home. Education was central to life here—most people became teachers, and the population was deeply dedicated to learning. However, industries were underdeveloped, and the economy remained weak. When the Soviet Union collapsed, opportunities opened up for the private sector. During the Soviet period, there was no private sector at all. The first private enterprise was established on 1 July 1984. I was appointed as the director of the Bureau of Travel and Excursions, as it was called”.(3 September 2022)

The tourism operator elaborated that, initially, tourists tended to visit other Soviet Republics rather than Tajikistan. Domestic tourism only began to develop later, with cities such as Khujand and Dushanbe receiving Intourist tours due to their well-developed infrastructure. In contrast, the Pamir region remained inaccessible, designated as a restricted zone for security reasons. Moreover, the area’s infrastructure was severely underdeveloped; for instance, even hotels lacked indoor plumbing. However, with a budding private sector and the increasing accessibility of the region to foreign visitors, a new ecotourism industry began to emerge. A former Executive Director of PECTA noted:

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, we quickly turned to tourism because people in the region were well educated and many spoke English. Local residents began building guesthouses and small hotels once they realized the financial benefits of tourism. The education system played a vital role in this transformation. The MSDSP also implemented projects that trained local people to produce handicrafts for tourists, creating new income opportunities.(3 September 2022)

The tourism expert confirmed the importance of education but also continuing obstacles:

Our people are very educated—about 99.9 percent of the population here is educated —and they recognized that tourism could be a great opportunity to make a living, since there were few other options. Still, I wouldn’t say we have a large number of visitors. Only a small fraction of all foreign tourists coming to Tajikistan visit the Pamirs, but that also depends on the population—not many people live in this region. The main challenge is the distance between destinations: from Dushanbe to Khorog, the center of the Pamirs, it’s about 600 km, and a tourist needs at least eight days to see everything properly. In some remote areas, homestays still offer very basic accommodation.(3 September 2022)

6.6. Obstacles to Ecotourism in the Pamirs

While the government of Tajikistan instituted numerous laws and regulations for the environment protection after the fall of the Soviet Union, our study’s respondents believe that the Law of Republic of Tajikistan on Nature Protection, (No. 223, 1996) and the Order of State Directorate of Natural Protected Areas, (No. 147, 2005, Law No. 786, 2011) will not guarantee long-term protection. A major issue highlighted was the lack of systematic scientific investigation into the biodiversity of the region. This gap stems from the departure of Russian conservationists and scientists [73].

Although the Tajik National Park (TNP) is a major asset to CBE for mountain tourism, it lacks adequate protection which has led to overgrazing and poaching. This problem is due to the lack of community awareness of the environmental fragility of the TNP ecosystem [74]. The 2013 UNESCO report on the Tajik National Park’s designation as a World Heritage Site noted that local communities were aware of the significance of this recognition and its potential to improve their livelihoods [75]. However, the report also highlighted concerns among these communities regarding the lack of government support for the park. Findings from the report validated these concerns, noting that park authorities admitted government investment was insufficient to ensure proper management of this vast protected area [75]. As a potential solution, Shokirov et al. [73] explored the idea of co-management. Their interviews with 61 hunters and herders indicated a willingness to participate in joint management initiatives.

Governmental promotion of mountain tourism has followed conventional methods rather than an ecotourism-focused approach. Key infrastructure challenges include poorly constructed roads and bridges [76] (Figure 7), a lack of basic facilities such as restrooms along travel routes, and limited dining options. Even the Tajik National Park, a major ecotourism attraction, suffers from insufficient facilities. While infrastructure development is underway, such as road construction, these efforts often stop short at the border of the Pamirs. In contrast, neighboring Kyrgyzstan has demonstrated how strategic capital investment can successfully support tourism across the country [77].

Figure 7.

Poor state of roads in the Pamirs. Source: Furough Shakarmamadova.

The Tajik government still faces significant challenges in developing a successful ecotourism sector. Respondents in our study stressed the need to prioritize infrastructure improvements while simultaneously formulating ecotourism policies. Efforts by the central government to enhance the competitiveness of local tour operators have yielded limited results. Ironically, this is partly due to Kyrgyz and Uzbek tour operators offering more affordable tour packages within Tajikistan.

7. Discussion

7.1. Importance of Definition

Understanding how tourism stakeholders conceptualize ecotourism and community-based ecotourism (CBE) is essential, as their definitions and expectations shape their perceptions of these sectors’ importance and success. As Giampiccoli and Saayman [78] note, success in ecotourism is inherently subjective, varying according to individual perspectives. Therefore, if informants share consistent understandings and expectations, this provides a reliable foundation for analysis and enables meaningful comparison with existing literature on the topic.

Insights from the interviews emphasized the nuanced nature of ecotourism, illustrating how it diverges fundamentally from conventional tourism models. One respondent highlighted the significance of incorporating ecology and local culture into defining ecotourism. Another common theme was the inclusion of environmental conservation which adheres to the norms of defining ecotourism as discussed by Fennell [79].

The concept of “community-based ecotourism” emphasizes local control and active participation in the development and management of ecotourism initiatives [80]. A key principle is that the benefits of ecotourism should remain within the community [81]. The perspectives expressed by informants, including homestay operators, tour guides, and representatives of NGOs such as PECTA, reflected this understanding, repeatedly underscoring the importance of community ownership and participation in decision-making processes.

7.2. Extent of CBE in the Pamirs

Alam and Nayak [82] emphasize the importance of fostering local participation, equitable benefit-sharing, and environmental education to enhance conservation outcomes. The Pamir Eco-Cultural Tourism Association advances these goals through its Tourist Information Center. This center equitably directs visitors to local homestays and tourism operators, thereby ensuring broad economic distribution within the community. Additionally, PECTA offers environmental training during the off-season to build local capacity. Effective marketing is also critical for expanding ecotourism and community-based ecotourism (CBE) [83]. PECTA contributes to this by facilitating the participation of local operators in international platforms such as the International Tourism Board (ITB), thereby increasing visibility for the Pamirs.

Despite these efforts, untapped opportunities remain. For instance, extending the tourism season has emerged as a promising strategy, with CBE members now offering winter experiences. Operators like Pamirecotourism and the Murghab Ecotourism Association have introduced winter wildlife safaris that include homestays for accommodation and cultural immersion. Furthermore, the Roshtqala district presents significant potential for CBE expansion due to its rich cultural and natural assets, which could attract additional ecotourists.

7.3. CBE as Driver of Economic Development and Environmental Preservation

Insights from our interviews allow us to assess how effectively Pamiri communities are achieving the outcomes outlined in our conceptual framework. Table 4 presents examples of success across these outcomes. Notably, increased income has emerged as a cornerstone of both community well-being and economic stability. PECTA, through its Tourist Information Center (TIC), has played a key role in directing ecotourists to a range of local enterprises. These include tour operators, homestays, hotels, and drivers, which facilitates a more equitable distribution of income. This coordinated approach has significantly contributed to the socio-economic resilience of Pamiri communities. Evidence of successful community-based ecotourism (CBE) initiatives has emerged across various low-income countries. For example, Ntshona and Lahiff [84] highlight effective CBE models in Cambodia, Peru, and Amadiba, South Africa. In Ventanilla, Oaxaca, Mexico, CBE-generated household income significantly greater than those singularly reliant on farming [85]. Ma et al. [67] found notable increases in household earnings near protected areas. In Thailand, Leksakundilok and Hirsch [86] reported that income from ecotourism ranged from 1.5% to 100% of household earnings, averaging 27.3%. Additional successful examples include homestays in the Himalayas [87], Peru [88], and northern Vietnam [89].

Table 4.

Success of CBE in meeting outcomes highlighted by the literature.

Empowerment is widely recognized as a cornerstone of successful community-based ecotourism (CBE) [14]. In the Pamirs, this is evident through active community involvement in product development and the establishment of village organizations (VOs). Facilitated by PECTA, these VOs were created to ensure that local voices shaped the direction of the emerging ecotourism sector. Research shows that meaningful community engagement can foster transformative leadership and strengthen collaboration in CBE development [90]. Such leadership is rooted in the empowerment of local stakeholders. For example, in Ban Na Village, Lao PDR, CBE initiatives led to increased community empowerment in developing and controlling of the local ecotourist activities [91]. Similarly, in the Sundarbans, Bangladesh, Dey et al. [92] found strong local interest in ecotourism, while Salam et al. [93] highlighted its socio-economic benefits, including job creation and cultural exchange through tourist interaction.

Our study revealed an increasing awareness among participants regarding the necessity of environmental conservation for the long-term viability of their developing economic activities. Informants stressed the importance of protecting the TNP, plus efforts in tree planting and green energy. These examples align with a core objective of community-based ecotourism (CBE): addressing environmental degradation. For instance, the Chambok CBE in Cambodia was established in response to forest loss, prompting active community engagement in ecotourism development and resource protection [94]. Similarly, Foucat [95] observed that CBE initiatives can stimulate conservation of natural landscapes and cultural heritage. However, Ma et al. [67] noted that while livelihoods improved near a panda reserve in China, increased environmental exploitation also occurred. In the Pamirs, efforts to reduce overgrazing in the Tajik National Park and combat poaching reflect growing local commitment to conservation.

Cultural conservation represents the final and most significant goal of CBEs. In the Pamirs, the vibrant tapestry of food, music, rituals, and architecture forms the backbone of the region’s CBE industry. Homestays and tour operators actively display this cultural richness, making them strong advocates for maintaining traditional practices and safeguarding heritage sites. Nguyen et al. [47], in their study of CBE in Central Vietnam, emphasized that cultural preservation is vital for building a sustainable ecotourism sector. The study underscores that effective cultural asset management, including visitor regulation to maintain carrying capacity, is indispensable for ensuring the long-term sustainability of CBEs across region [96].

7.4. Sustainability of Community-Based Ecotourism

The body of research on CBEs emphasizes multiple essential conditions necessary to foster growth and long-term viability of this sector. These include inclusive governance and strategic planning [12,46], as well as active participation from local communities [12]. Efani et al. [97] emphasized the importance of balanced policies that address ecological, economic, and social dimensions. Such policies should support capacity building within local communities, which in turn depends on robust institutional backing [46]. In relation to economic and social aspects, effective mentoring of CBE initiatives can significantly enhance employment opportunities [94]. Lastly, cultivating a strong sense of environmental stewardship is vital for the long-term sustainability of the CBE industry [12].

Drawing on the insights provided by informants, CBE in the Pamirs appear to fulfill many of the foundational criteria outlined in the literature for sustainable development. In terms of inclusive governance and strategic planning, Village Organizations (VOs) are actively engaged in the planning of CBE activities in collaboration with the Pamir Eco-Cultural Tourism Association (PECTA). Furthermore, PECTA has played a pivotal role in mentoring CBE initiatives, contributing to notable job creation within the region. As our IPA framework matrix results demonstrate that involvement in CBE activities correlates with increased environmental awareness among informants, thereby suggesting a reinforcement of pro-environmental attitudes and stewardship behaviors.

As a result, Pamiri CBEs have contributed to poverty alleviation, environmental conservation, and socio-economic empowerment, fostering a sense of ownership and cultural preservation among local communities. Nevertheless, the sector continues to face challenges as highlighted by our informants. They cite inadequate institutional support from the central government and limited investment in infrastructure. There remains significant scope for the development of more effective governmental policies aimed at environmental protection. Informants consistently identified key barriers to the development of CBE in the Pamirs. Those identified include inadequate road infrastructure, limited stakeholder consultation in policy formulation, ongoing poaching activities, and insufficient investment in human capital.

Government participation is essential to both the initial development and the ongoing sustainability of CBE frameworks. For instance, Kim et al. [98], in their study of CBEs in Cambodia, highlighted the introduction of a national ecotourism policy that empowers local communities to manage ecotourism sites. This policy also provides incentives and opportunities for individual households, thereby encouraging broader community participation. According to Bhalla et al. [99], local government participation is critical to the success of Himalayan homestay programs. Public education initiatives centered on conservation play a key role in ensuring that residents gain meaningful advantages from their environmental resources.

7.5. Local Governance and Empowerment in Community-Based Ecotourism

Strong inclusive governance is fundamental to equitable and sustainable CBE development which inherently leads to the empowerment of local communities [100]. Effective governance must recognize the legitimacy of diverse stakeholders and must take into consideration social status and hierarchies [13]. Nurhasanah et al. [14] found that Bottom-up projects lead to empowerment of local communities and foster real engagement and long-term collaboration [13]. Leadership, institutional coordination, and transparent decision-making processes are essential to building trust and enhancing community involvement [101]. Moreover, culturally sensitive strategies help promote long-term stakeholder engagement [102]. Inclusive governance is vital to enhancing CBE’s role in environmental conservation and the promotion of sustainable livelihoods.

Our findings reveal that the governance structure of CBE in the Pamirs is characterized by a high degree of inclusivity. Interview data reveal that a broad spectrum of stakeholders, consistent with those identified in the relevant literature, are actively engaged in the sector. CBE initiatives structured from the bottom up have contributed to empowering local communities. Kreczi [103] emphasizes the pivotal role of Village Organizations (VOs) as key agents in advancing development objectives. This participatory approach also encourages the implementation of culturally sensitive strategies. Non-governmental organizations, such as the PECTA, have recognized the need to incorporate such strategies in promoting CBE and the inclusion of VOs in its development. In contrast, top-down governance is largely absent, as the central government’s ruling elites have shown limited interest in the Pamirs [104]. Consequently, government engagement in establishing local ecotourism has been minimal.

7.6. Shifts in Geopolitics and Pamiri Ecotourism

Following the dissolution of the Soviet Union, all former Soviet republics experienced profound socio-economic upheaval [105]. The abrupt withdrawal of state support for health care, education, and employment left these nations seeking alternative strategies for self-sufficiency [106]. The Pamir region experienced disproportionate impacts owing to its geographic isolation and classification as a restricted zone, conditions that significantly constrained economic development [35,36,37]. According to statements from PECTA officials and tourism experts, Pamiri communities began exploring new economic opportunities, notably ecotourism and CBE. The region’s remoteness inadvertently preserved its natural environment and cultural heritage, creating favorable conditions for the emergence of these industries. This shift contributed to the region’s economic resilience. Free educational provision under the Soviet system unintentionally created the structural basis that facilitated the emergence and growth of this sector. Similar examples have occurred in other Central Asian countries, including Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Turkmenistan [45,77,107].

7.7. Building Community Resilience Through Ecotourism

Our hypothesis proposed that ecotourism, particularly community-based enterprises (CBE), could enhance resilience among geographically and economically marginalized communities. The findings of this study provide strong support for this proposition. Our IPA framework matrix provides direct evidence of how local communities see that ecotourism and CBE are increasing their financial income, creating new jobs thereby leading to more stable communities. The preservation of cultural heritage, recognized as integral to the success of ecotourism, has emerged as a priority, necessitating its protection. Similarly, informants underscored the critical importance of conserving the natural environment, who acknowledged its significant role in attracting visitors.

According to the current director of the PECTA, both ecotourism and CBEs continue to expand across the Pamir region, contributing to growing community resilience. External support has also proven critical to the success of these sectors [108]. In particular, the involvement of PECTA has been instrumental in facilitating development through financial assistance, capacity-building initiatives, and strategic marketing. Informants consistently cited these forms of support as essential to the establishment and sustainability of local ecotourism and CBE activities.

For these sectors to maintain momentum and achieve long-term viability, it is imperative that all stakeholders are actively engaged in the planning, development, and management processes [109]. Such inclusive participation fosters community empowerment, a key component of resilience [110]. While informants reported involvement in decision-making at the local level, many expressed concern about being marginalized in the processes of policy development at the national scale.

Despite existing challenges, there remain significant opportunities to further strengthen community resilience through the continued development of ecotourism and CBEs. As previously noted, inadequate infrastructure, such as poor road conditions, limited airport access, and insufficient sanitation facilities, poses a major barrier to growth. Bhuiyan et al. [111] highlighted the importance of government investment for ecotourism development. Addressing these infrastructural shortfalls is not only vital for the advancement of ecotourism and CBEs but also for broader economic development. Improved connectivity and services could attract additional industries and enhance the region’s capacity to export goods to wider markets across Tajikistan. Comparable investments have demonstrated success in bolstering the economies of other remote regions in low-income countries such as Costa Rica [112], Zimbabwe [113], and Gambia [114].

7.8. Limitations of Study

This study is subject to several limitations that warrant consideration. First, travel restrictions in place during the data collection period prevented in-person interviews. As a result, all interviews were administered remotely. Although this approach is not without shortcomings, the research team sought to mitigate potential constraints by leveraging established personal networks, which helped with participant recruitment and fostered trust. Second, the study design initially envisioned the inclusion of a survey instrument to enable a broader quantitative analysis. However, practical challenges, most notably the geographic isolation of the study area and limited internet connectivity, made survey distribution infeasible.

8. Conclusions

The findings of this study demonstrate that the ecotourism sector, including CBE, plays an effective role in enhancing community resilience. Nonetheless, considerable potential remains for further expansion of this sector. Despite the efforts of NGOs such as PECTA, the advancement of ecotourism remains constrained by the absence of targeted government policies and the limited allocation of resources for infrastructural development. Informants suggested a need to create such policies before the central government invests in infrastructural improvement as these policies will help guide such investment.

CBE initiatives in the Pamirs have demonstrated significant effectiveness. Local communities exhibit strong motivation to further improve and expand the quality of their services. Increased income and employment opportunities contribute positively to the long-term societal sustainability of these communities. Moreover, CBE has proven highly effective in promoting environmental awareness, as the tangible financial benefits derived from ecotourism have increased local appreciation for environmental protection. The direct link between conservation and livelihood has encouraged environmental stewardship among community members. Consequently, the continued expansion of CBE in the Pamirs is pivotal for strengthening the social, economic, and environmental stability of the region.

We emphasize that a multi-stakeholder approach is essential to the success of CBE, particularly with the active involvement of all levels of government. Governmental bodies must not only develop, fund, and enforce effective environmental policies, but also to support its growth through investments in regional and local infrastructure. However, stakeholder participation in environmental decision-making remains uneven. The extent to which the central government incorporates local community perspectives is unclear, though evidence from our research suggests it is limited. As a result, the effectiveness of existing or future regulations in enhancing the environmental sustainability of the Pamirs remains uncertain.

Upon completing this study and in light of the challenges surrounding the development of ecotourism and CBE in the Pamir region, we propose a series of recommendations. These are intended to support the sustainable advancement of CBE initiatives:

- Policy Reform: There is a pressing need for updated government policies focused on environmental protection. These policies should be informed by the best available scientific evidence and incorporate meaningful stakeholder input.

- Infrastructure Investment: The Tajik government must prioritize infrastructure development in the region. Current road conditions are severely inadequate, and access to air travel remains extremely limited, posing significant barriers to tourism growth.

- Global Visibility: The Pamirs suffer from limited global visibility. Strategic government investment in marketing the region, highlighting its distinctive environmental and cultural attributes, could enhance its visibility and attract ecotourism.

- Support for Tajik National Park (TNP): The TNP represents a critical resource for ecotourism but is currently understaffed. Adequate staffing would not only help mitigate poaching but also improve safety and visitors’ experience within the park.

- Public–Private Partnerships: The development of public–private partnerships modeled after Kazakhstan’s Integrated Ecotourism Development Model [115] could be adopted. Kazakhstan faces similar challenges, and its approach may provide valuable lessons for the Pamirs.

In terms of future investigations, this research could be broadened to encompass additional Central Asian nations. Examining comparable efforts to establish CBE in neighboring countries could yield valuable insights. Such analysis would help identify which strategies have proven effective and which have not. Pooling this knowledge would allow for a comprehensive approach to promoting CBE in the region, not only for smaller geographic settings. Exploring how best to integrate private/public partnerships could help streamline the implementation of CBE, thereby strengthening the overall growth of this sector across the region.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/su18010207/s1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.S., P.E.v.B. and F.A.A.; methodology, F.S., P.E.v.B. and F.A.A.; formal analysis, F.S. and P.E.v.B.; investigation, F.S.; resources, F.S.; data curation, F.S.; writing—original draft preparation, F.S.; writing—review and editing, F.S., P.E.v.B. and F.A.A.; visualization F.S., P.E.v.B. and F.A.A.; supervision, P.E.v.B. and F.A.A.; project administration, F.S., P.E.v.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

No external or internal funding was used for this research.

Institutional Review Board Statement

According to Institutional Review Boards of University of South Florida, this activity does not constitute research involving human subjects as defined by DHHS and FDA regulations, therefore, IRB review and approval is not required.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

Shakarmamadova, van Beynen and Akiwumi thank the informants of this study who graciously gave their time to provide in-depth responses to the many questions. In particular PECTA and the Executive Director, Government entities (Tajik National Park) and Civil Society. We thank the anonymous reviewers and academic editors for their valuable contributions.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Furough Shakarmamadova was employed by the company Oxus. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Anandaraj, M.; Phil, M. Ecotourism: Origin and Development. Int. J. Manag. Humanit. 2015, 2, 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Machnik, A. Ecotourism as a Core of Sustainability in Tourism. In Handbook of Sustainable Development and Leisure Services; Lubowiecki-Vikuk, A., de Sousa, B.M.B., Đerčan, B.M., Leal Filho, W., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coria, J.; Calfucura, E. Ecotourism and the Development of Indigenous Communities: The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly. Ecol. Econ. 2012, 73, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kia, Z. Ecotourism in Indonesia: Local Community Involvement and the Affecting Factors. J. Gov. Public Policy 2021, 8, 93–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salman, A.; Jaafar, M.; Mohamad, D.; Ebekozien, A.; Rasul, T. The Multi-Stakeholder Role in Asian Sustainable Ecotourism: A Systematic Review. PSU Res. Rev. 2024, 8, 940–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeboah, T. Dynamics of Ecotourism Benefits Distribution. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2024, 21, 122–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cresco, S.; Querini, G. The Role of Tourism in Sustainable Economic Development. Eur. Reg. Sci. Assoc. 2003, 1, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Hunt, C.A.; Harbor, L.C. Pro-environmental Tourism: Lessons from Adventure, Wellness and Ecotourism (AWE) in Costa Rica. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2019, 28, 100233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero-Moreno, M.A.; Oliveira-Junior, J.M.B. Approaches, Trends, and Gaps in Community-Based Ecotourism Research: A Bibliometric Analysis of Publications between 2002 and 2022. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunjuraman, V.; Hussin, R.; Che Aziz, R. Community-Based Ecotourism as a Social Transformation Tool for Rural Community: A Victory or a Quagmire? J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2022, 39, 100524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erwin, E.; Rahim, A.; Dwipatn, I.M.J.A.; Nugraha, P.A.D. Revitalizing Village-Owned Enterprises (Bumdes) Through BUMDES Management Training for Sustainable Tourism Development: A Case Study of Rinding Allo Village, Rongkong District. Soc. J. Pengabdi. Masy. 2025, 4, 814–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafezi, F.; Bijani, M.; Gholamrezai, S.; Savari, M.; Panzer-Krause, S. Towards Sustainable Community-Based Ecotourism: A Qualitative Content Analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 891, 164411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darwis, H.; Duli, A.D.; Mulyadi, Y.; Rasyidi, E.S.; Mappasomba, Z.M.; Rudi, R. Collaborative Governance in Community-Based Mangrove Ecotourism: A Longitudinal Case Study of Banua Pangka, Luwu Timur (2015–2025). J. Multidiscip. Res. Innov. 2025, 1, 317–325. [Google Scholar]

- Nurhasanah, I.S.; Hudalah, D.; Van den Broeck, P. Systematic Literature Review on Alternative Governance Arrangements for Resource Deficient Situations: Small Island Community-Based Ecotourism. Isl. Stud. J. 2024, 19, 214–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M.N.; Syaputra, Y. Social and Economic Impacts of Ecotourism Development on Local Communities in Coastal Tourism Areas. Bima Cendikia J. Community Engagem. Empower. 2025, 2, 41–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prarthana, P.; Rathnayakalage, K. An Analysis of the Challenges and Opportunities in Promoting Sustainable Community-Based Homestay Tourism in Galle, Sri Lanka. Master’s Thesis, Umeå University, Umeå, Sweden, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Teshome, E.; Shita, F.; Abebe, F. Current Community-Based Ecotourism Practices in Menz Guassa Community Conservation Area, Ethiopia. GeoJournal 2021, 86, 2135–2147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoo, R.A.; Songorwa, A.N. Contribution of Ecotourism to Nature Conservation and Improvement of Livelihoods around Amani Nature Reserve, Tanzania. J. Ecotour. 2013, 12, 75–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, G.; Chen, X.; Liu, W.; Bearer, S.; Zhou, S.; Cheng, L.Y.; Liu, J. Distribution of Economic Benefits from Ecotourism: A Case Study of Wolong Nature Reserve for Giant Pandas in China. Environ. Manag. 2008, 42, 1017–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irawan, D.; Istiqomah, Y. Strengthening Coastal Community Resilience through Marine Ecotourism in Pangandaran, West Java. Bima Cendikia J. Community Engagem. Empower. 2024, 1, 175–212. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, S. Capacity Building of Community-Based Ecotourism in Developing Nations: A Case of Mei Zhou, China. In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Business, Economics, Management Science (BEMS 2019), Hangzhou, China, 20–21 April 2019; pp. 582–605. [Google Scholar]

- Magis, K. Community Resilience: An Indicator of Social Sustainability. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2010, 23, 401–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutter, S.L.; Barnes, L.; Berry, M.; Burton, C.; Evans, E.; Tate, E.; Webb, J. A Place-Based Model for Understanding Community Resilience to Natural Disasters. Glob. Environ. Change 2008, 18, 598–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbers, H. Transformation in the Tajik Pamirs: Gornyi-Badakhshan-an example of successful restructuring? Cent. Asian Surv. 2001, 20, 367–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanif, H.; Maulida, A.; Kamal, M.; Oktari, R.S. Empowerment and Development of Kajhu Village as a Disaster Resilient Village Based on Factorization and Ecotourism. J. Pengabdi. Kpd. Masy. (Indones. J. Community Engag.) 2023, 9, 68. [Google Scholar]