Toward Sustainability: Examining Economic Inequality and Political Trust in EU Countries

Abstract

1. Introduction

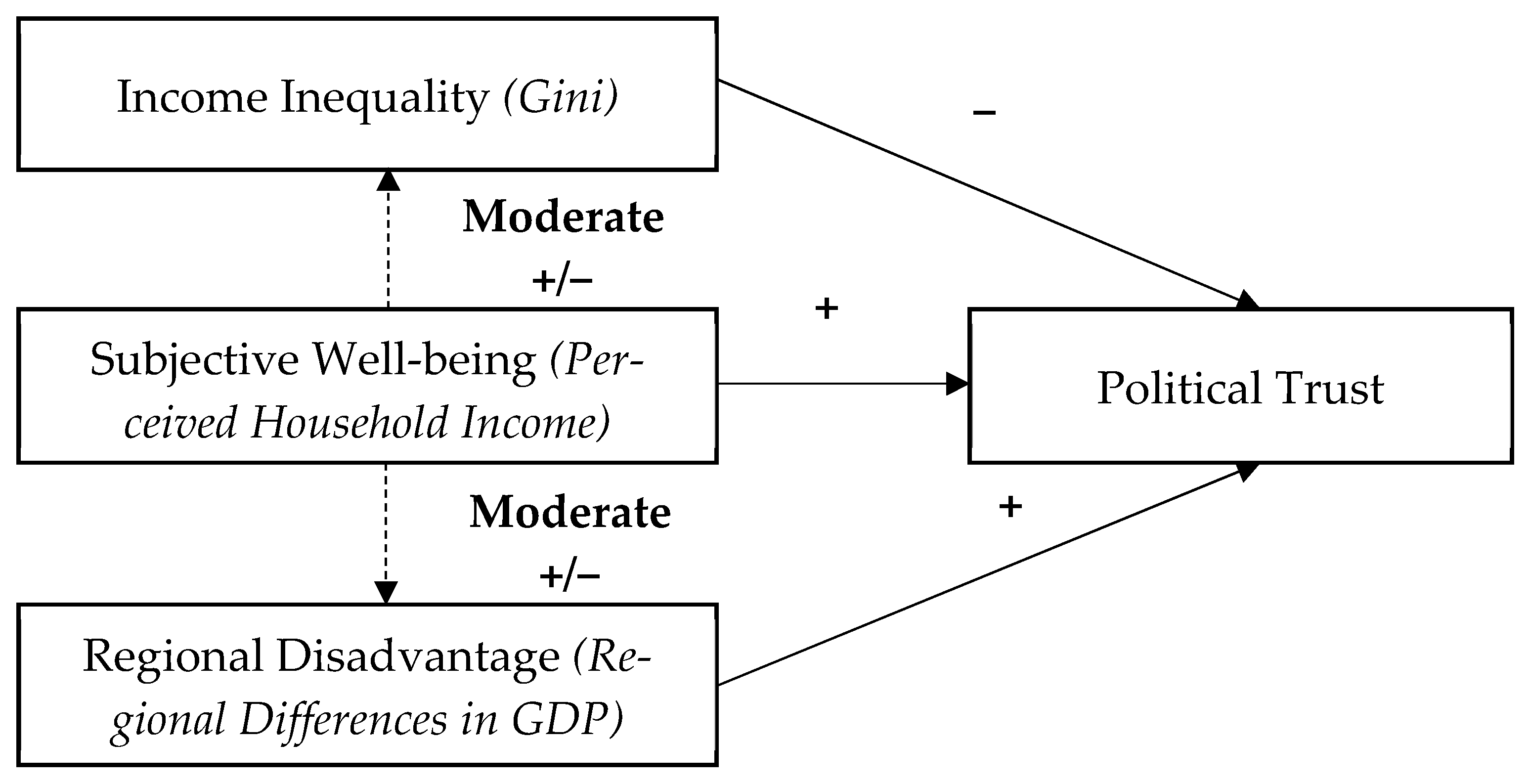

2. Literature Review

3. Materials and Methods

4. Results

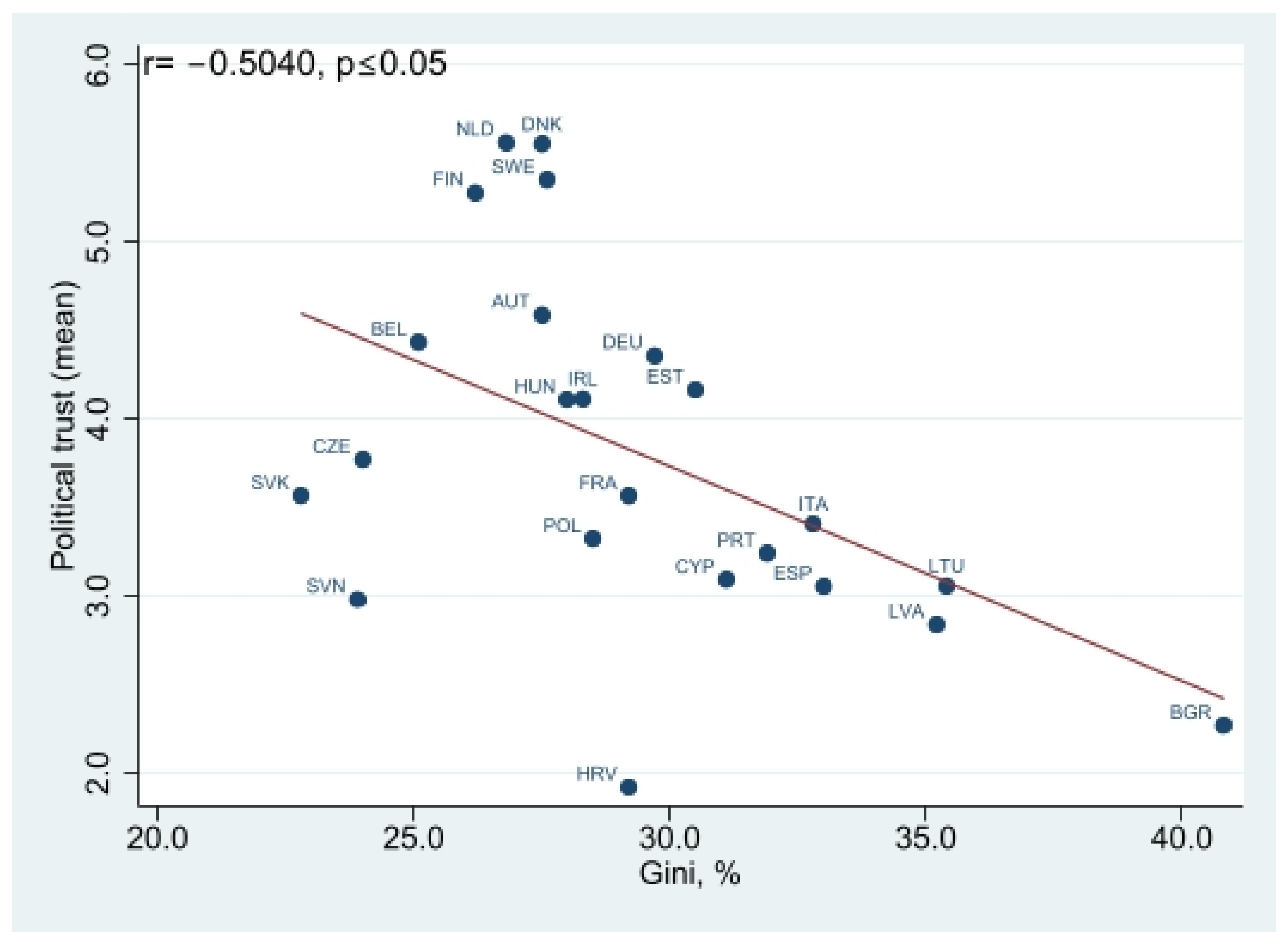

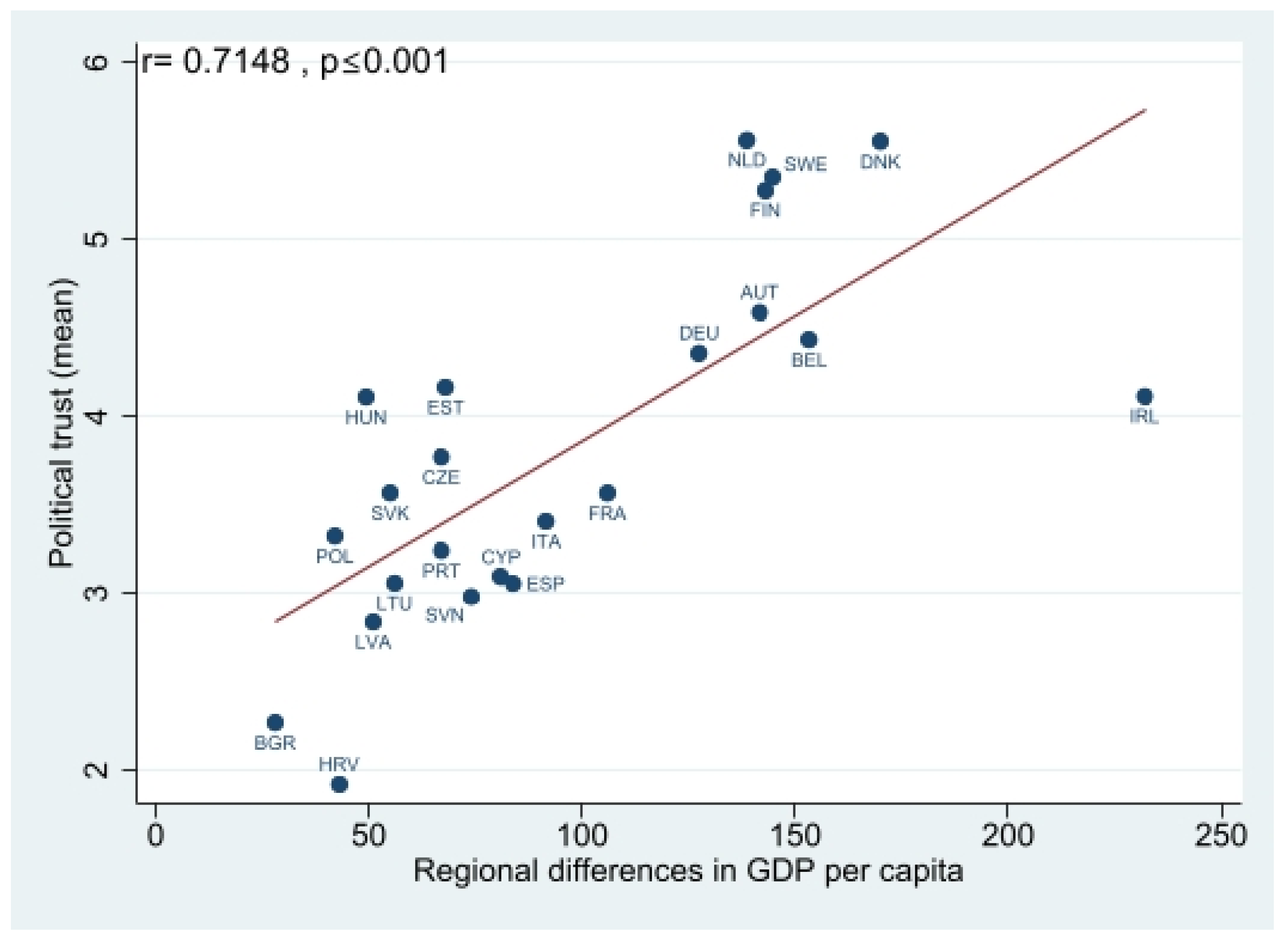

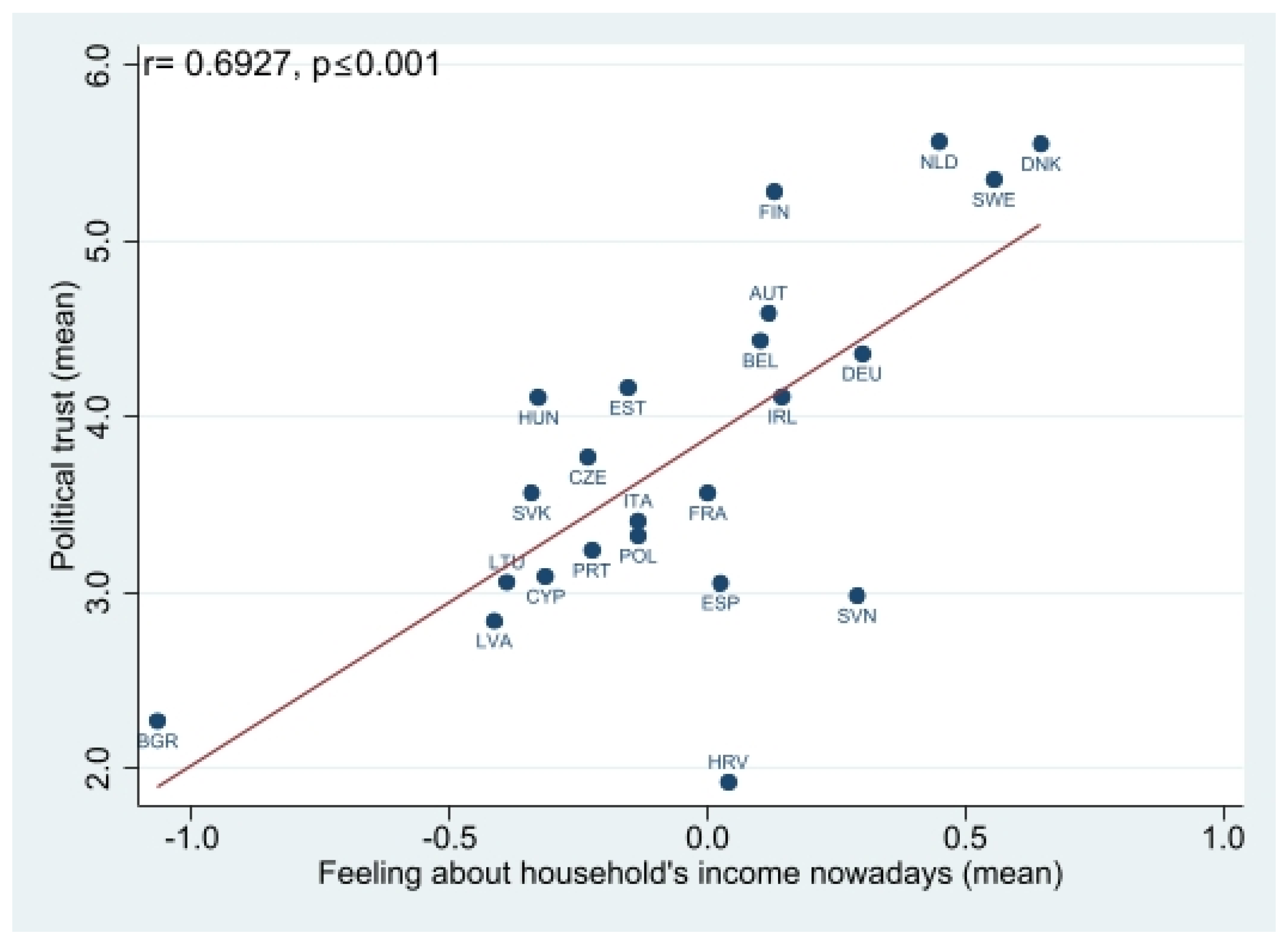

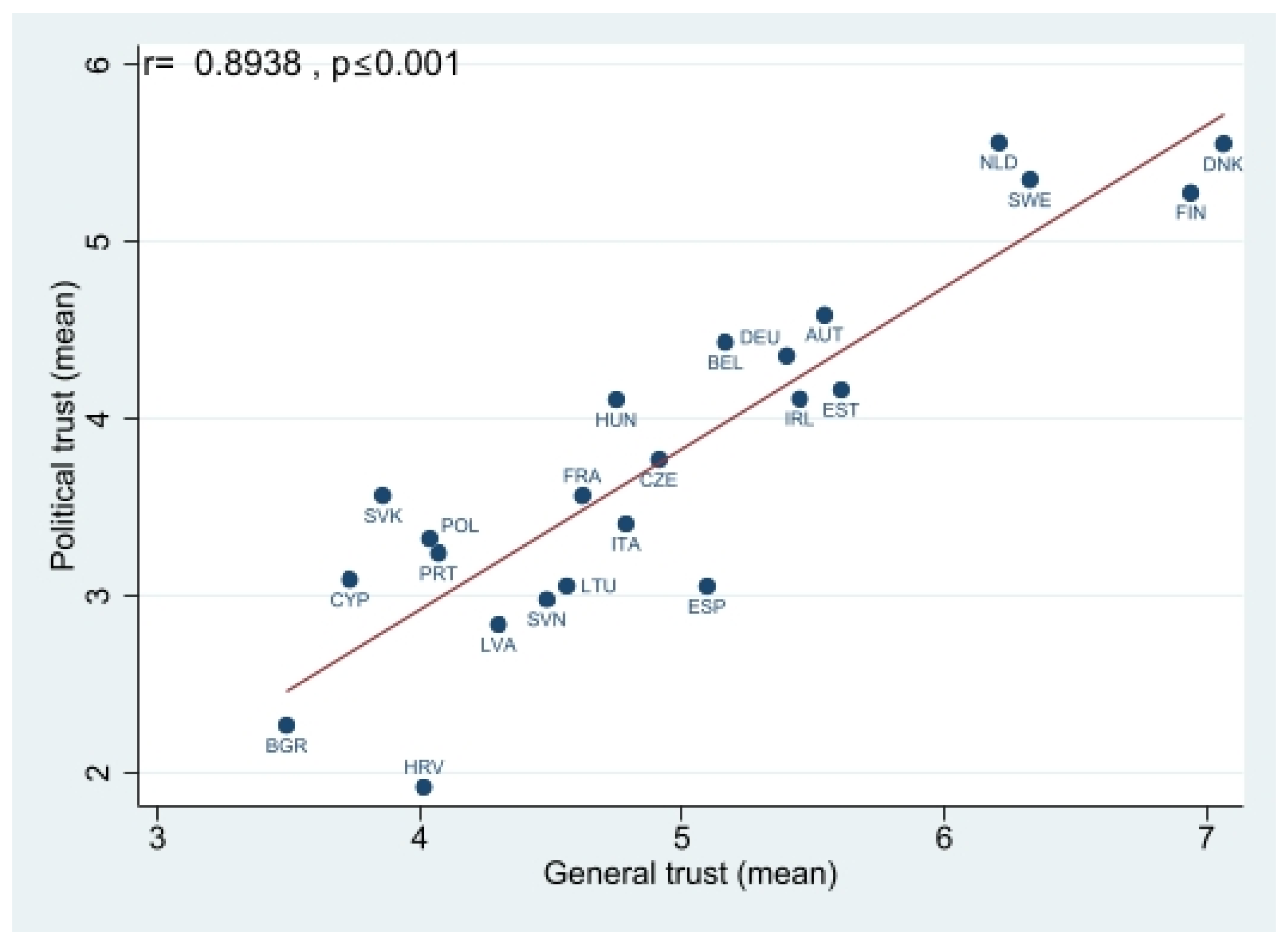

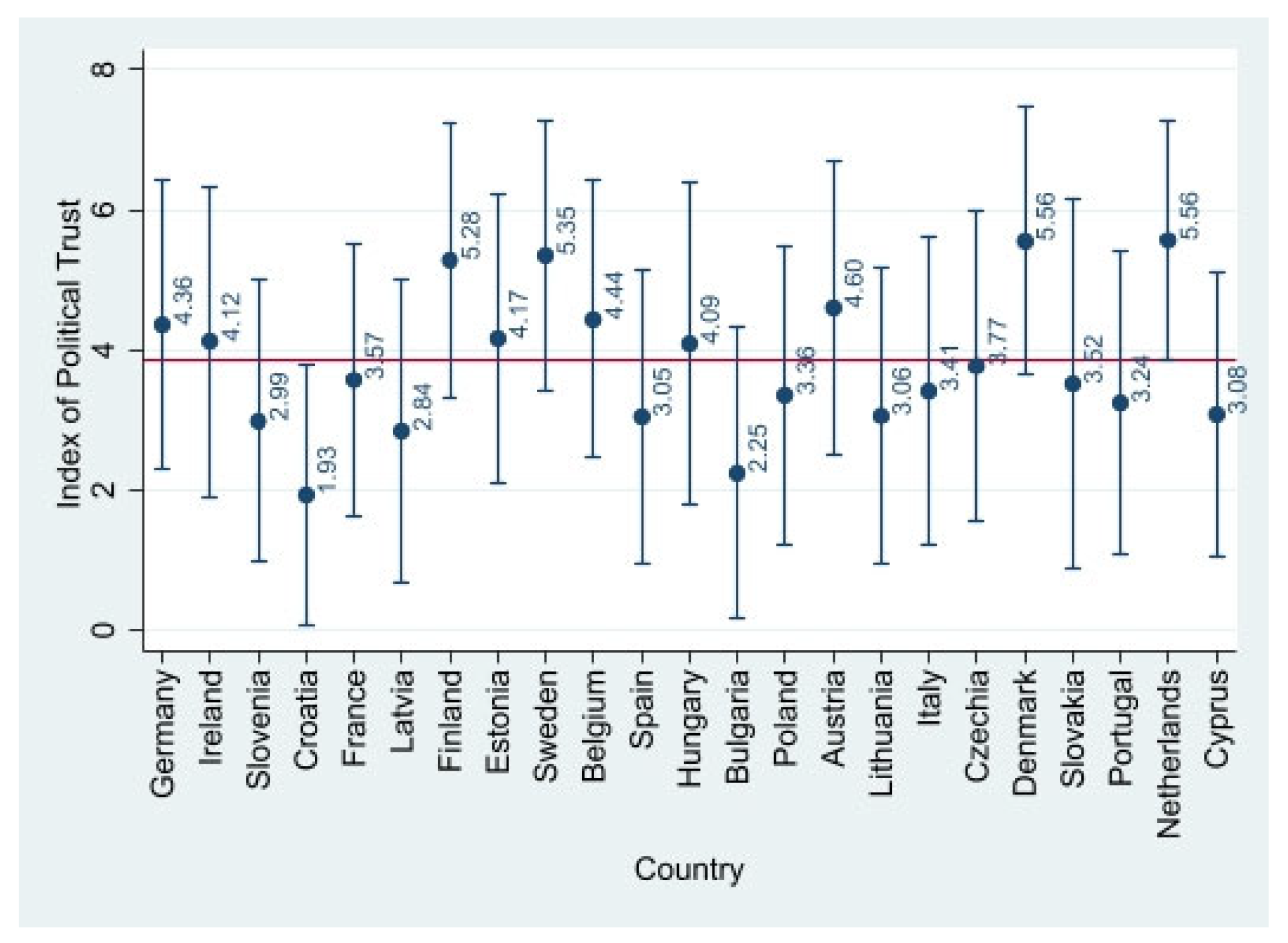

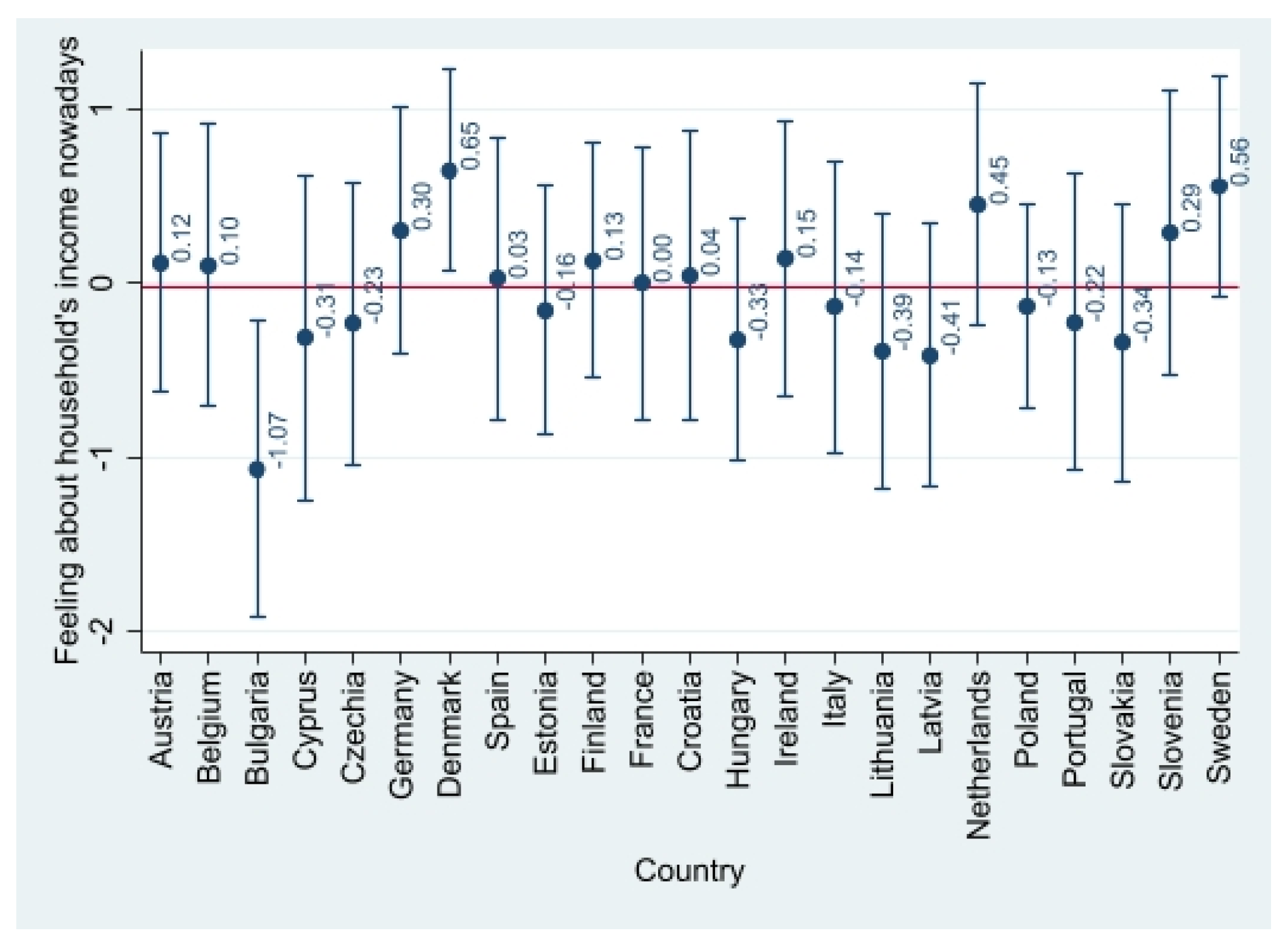

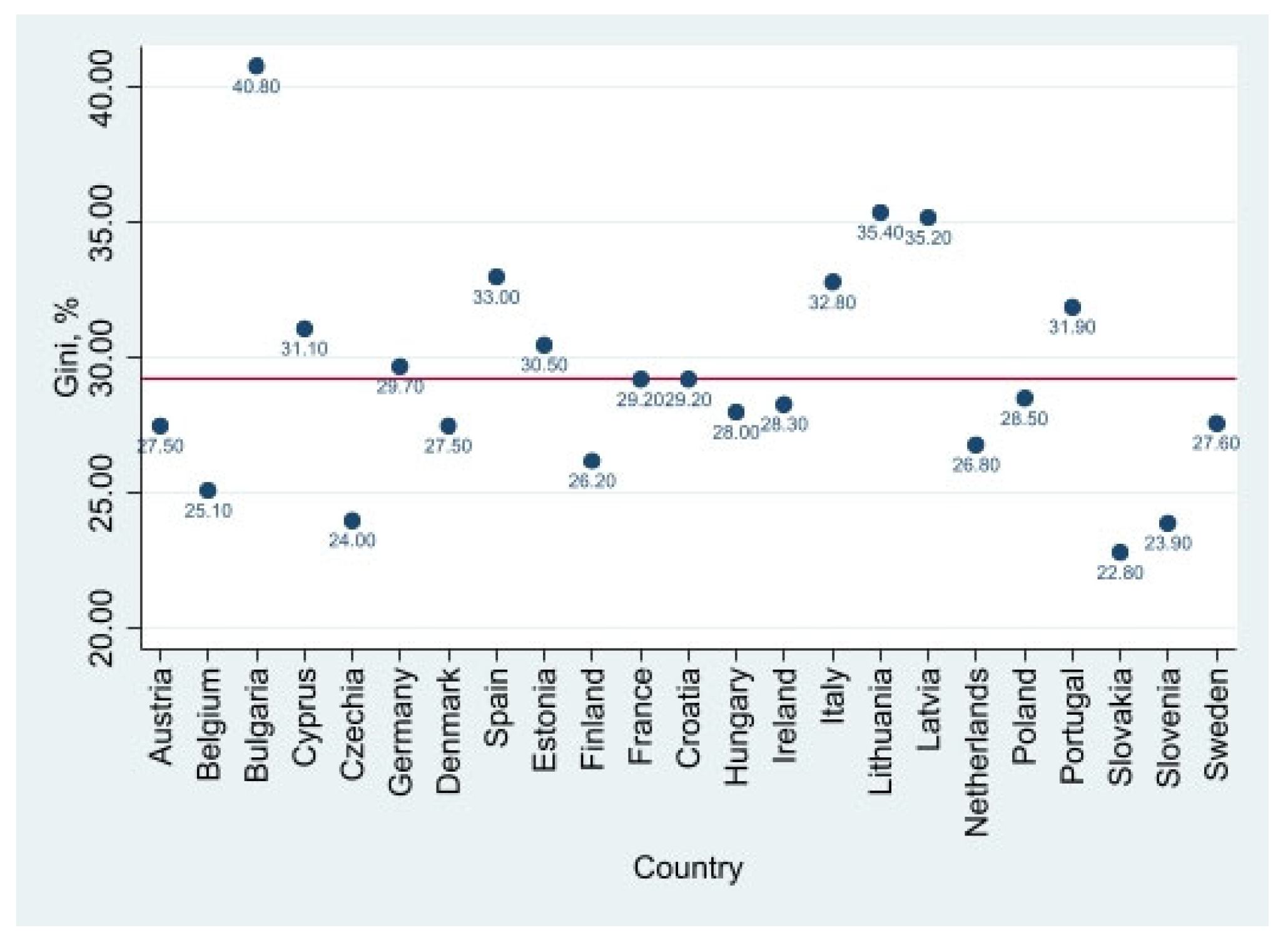

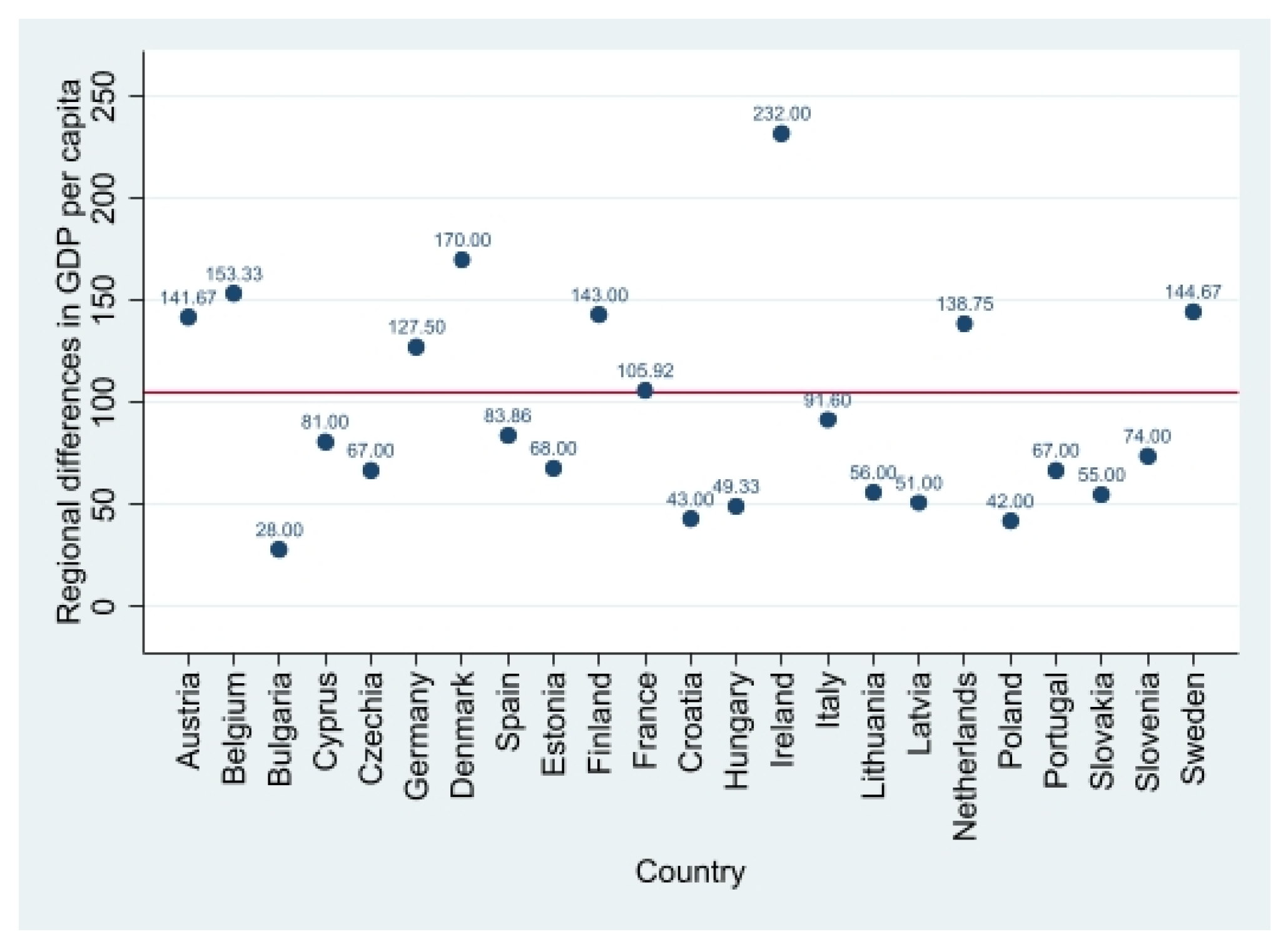

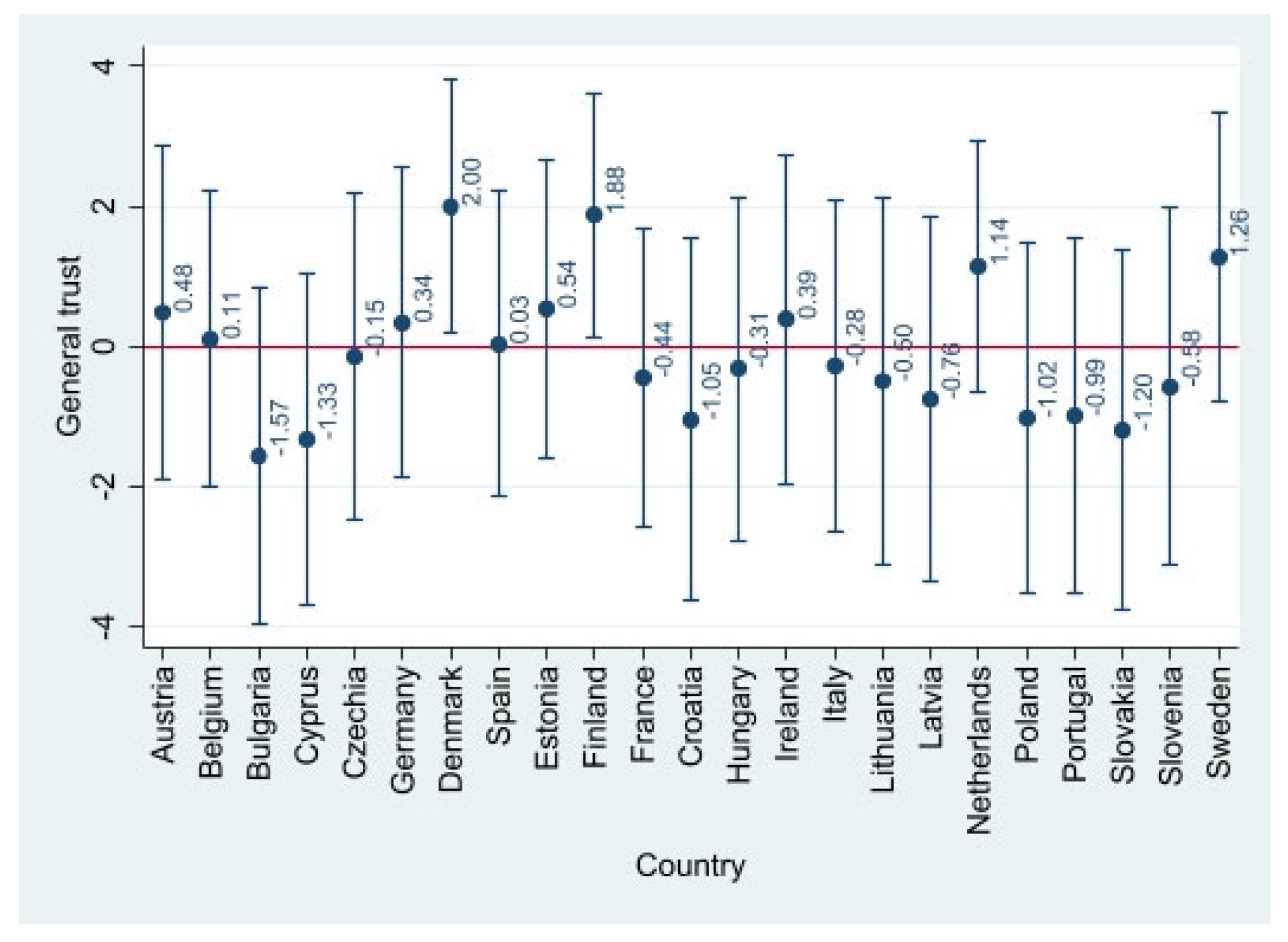

4.1. Descriptive Evidence

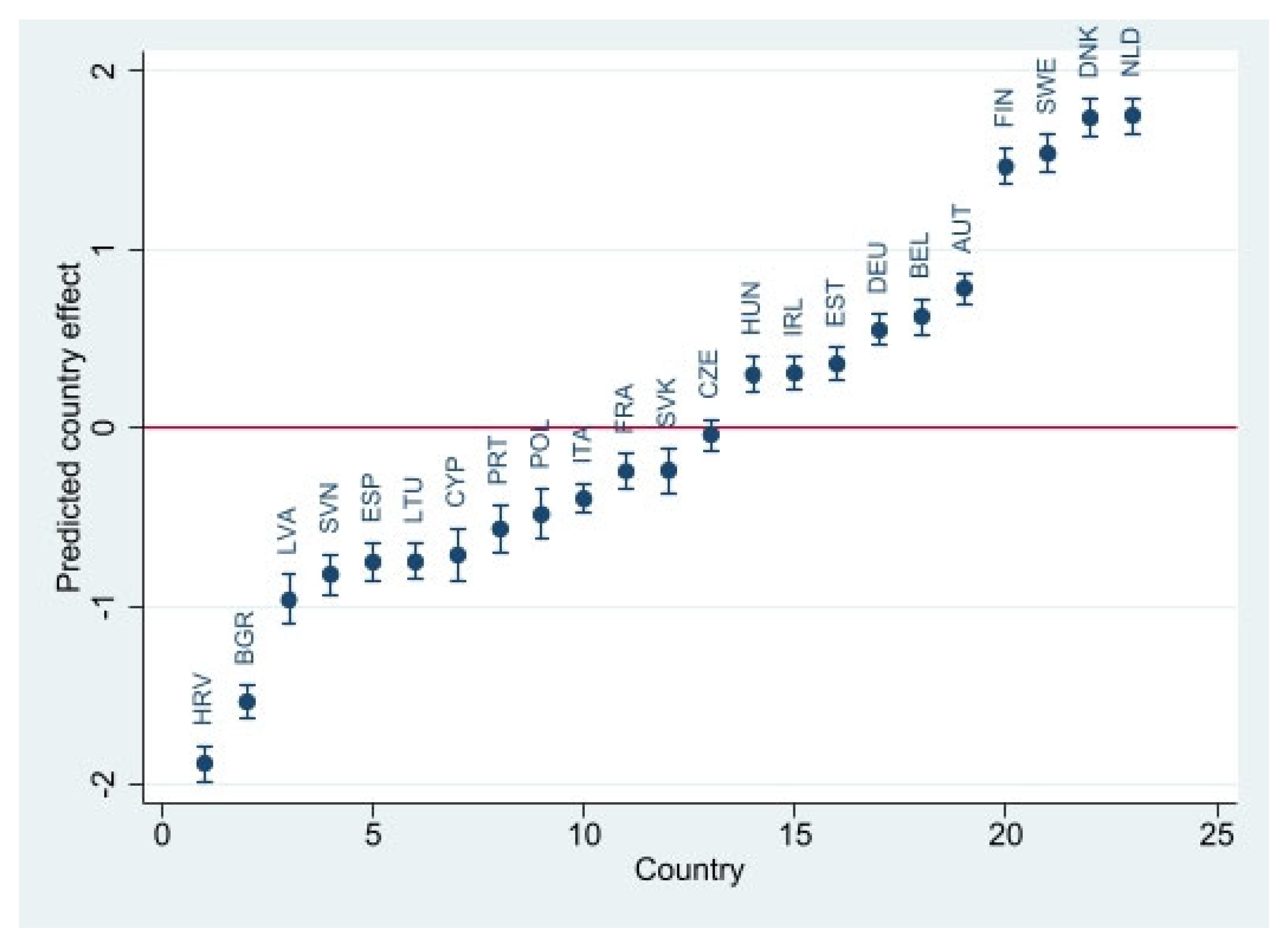

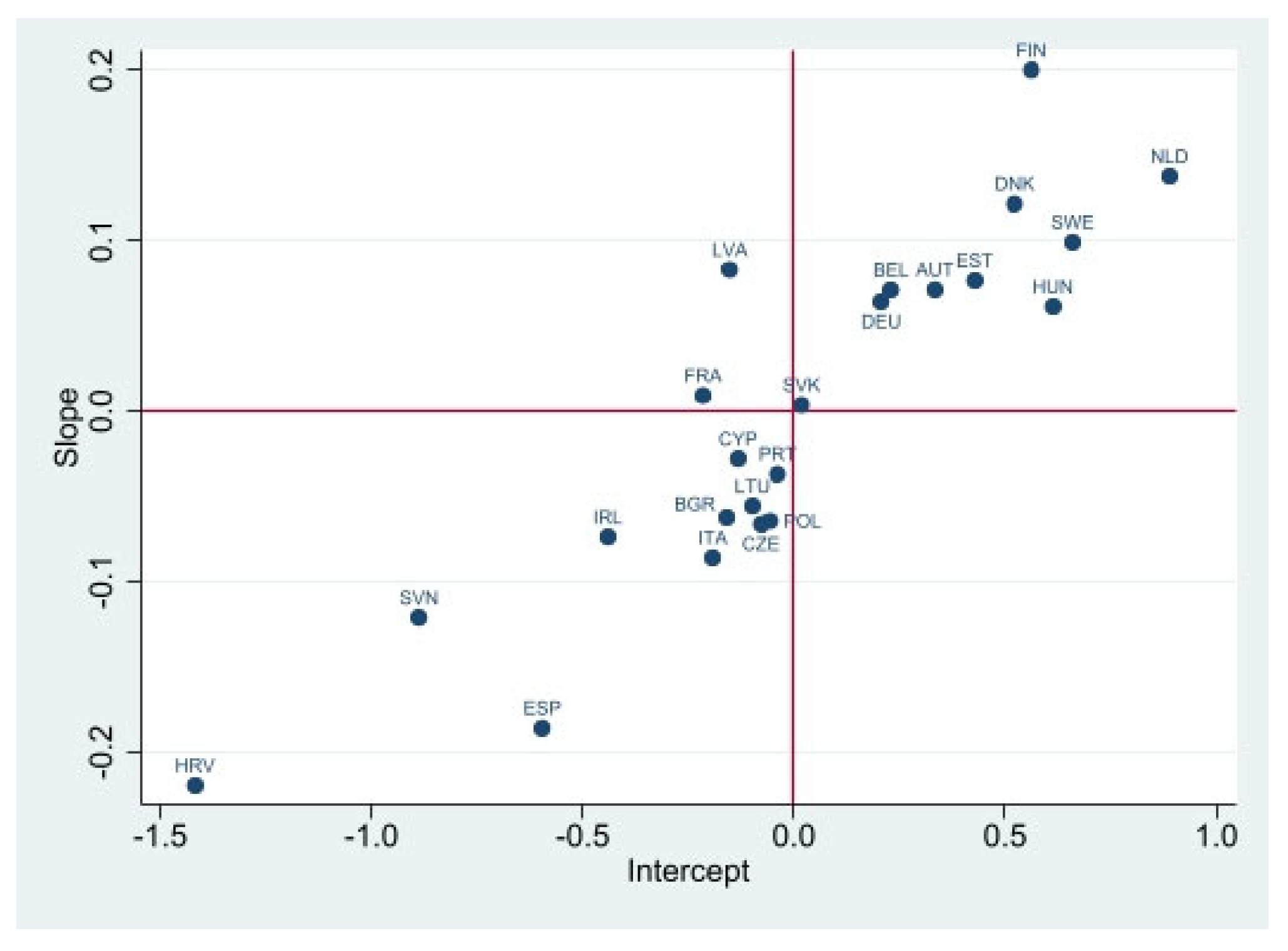

4.2. Evidence from Multilevel Models

4.2.1. The Unconditional Random Intercept Model

4.2.2. The Two-Level Random Intercept Model

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| GDP | Gross domestic product |

| EU | European Union |

| PCA | Principal component analysis |

| ESS | European Social Survey |

| ICC | Intraclass Correlation Coefficient |

| DEFF | Estimated Design Effect |

| SDG | Sustainable Development Goal |

| AIC | Akaike Information Criterion |

| BIC | Bayesian Information Criterion |

Appendix A. Results of the Correlation Analysis

Appendix B. Results of Multilevel Analysis

| Variables | Models | ||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |

| Country Level | |||||||||||

| Gini | −0.12 *** (0.03) | −0.09 ** (0.03) | −0.07 ** (0.02) | −0.07 *** (0.02) | −0.07 ** (0.02) | −0.07 *** (0.02) | −0.07 *** (0.02) | −0.04 * (0.02) | −0.07 ** (0.03) | −0.05 * (0.02) | |

| GDP_diff | 0.01 *** (0.00) | 0.01 *** (0.00) | 0.01 *** (0.00) | 0.01 *** (0.00) | 0.01 *** (0.00) | 0.01 *** (0.00) | 0.01 *** (0.00) | 0.01 *** (0.00) | |||

| Individual Level | |||||||||||

| Income | 0.42 *** (0.03) | 0.42 *** (0.04) | 0.30 *** (0.03) | 0.30 *** (0.03) | 0.65 *** (0.18) | 0.15 ** (0.05) | 0.32 *** (0.03) | 0.65 ** (0.22) | 0.23 *** (0.04) | ||

| G_trust | 0.26 *** (0.02) | 0.26 *** (0.02) | 0.26 *** (0.02) | 0.26 *** (0.02) | 0.26 *** (0.01) | 0.26 *** (0.01) | 0.26 *** (0.01) | ||||

| Gender | −0.01 (0.03) | −0.02 (0.03) | −0.01 (0.03) | −0.01 (0.02) | −0.01 (0.02) | −0.01 (0.02) | |||||

| Age | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.00 (0.00) | −0.00 (0.00) | −0.00 (0.00) | −0.00 (0.00) | −0.00 (0.00) | |||||

| P_work | −0.20 *** (0.06) | −0.20 *** (0.06) | −0.20 *** (0.05) | −0.20 *** (0.04) | −0.20 *** (0.04) | −0.20 *** (0.04) | |||||

| Unempl_a | −0.20 ** (0.07) | −0.20 ** (0.07) | −0.20 ** (0.07) | −0.21 ** (0.07) | −0.21 ** (0.07) | −0.21 ** (0.07) | |||||

| Educ | 0.42 *** (0.05) | 0.42 *** (0.05) | 0.42 *** (0.05) | 0.43 *** (0.05) | 0.43 *** (0.05) | 0.43 *** (0.05) | |||||

| Housework | −0.08 (0.04) | −0.08 (0.04) | −0.08 (0.04) | −0.08 ** (0.03) | −0.08 ** (0.03) | −0.08 ** (0.03) | |||||

| Unempl_n | −0.12 (0.11) | −0.12 (0.11) | −0.12 (0.11) | −0.12 (0.08) | −0.12 (0.08) | −0.12 (0.08) | |||||

| Disabled | −0.37 *** (0.06) | −0.37 *** (0.06) | −0.37 *** (0.06) | −0.34 *** (0.06) | −0.34 *** (0.06) | −0.34 *** (0.06) | |||||

| Retired | −0.01 (0.06) | −0.01 (0.06) | −0.01 (0.06) | −0.01 (0.05) | −0.01 (0.05) | −0.01 (0.05) | |||||

| Cm_serv | −0.26 (0.23) | −0.27 (0.23) | −0.27 (0.23) | −0.27 (0.32) | −0.27 (0.32) | −0.27 (0.32) | |||||

| Other | −0.12 (0.08) | −0.12 (0.08) | −0.11 (0.08) | −0.10 (0.08) | −0.10 (0.08) | −0.10 (0.08) | |||||

| Intersections | |||||||||||

| Income × Gini | −0.01 * (0.01) | −0.01 (0.01) | |||||||||

| Income × GDP_diff | 0.01 ** (0.00) | 0.01 * (0.00) | |||||||||

| Constants | |||||||||||

| Constant | 3.81 *** (0.21) | 7.36 *** (1.15) | 6.71 *** (1.01) | 5.56 *** (0.83) | 5.37 *** (0.66) | 5.48 *** (0.68) | 5.61 *** (0.72) | 5.56 *** (0.68) | 4.79 *** (0.59) | 5.59 *** (0.79) | 4.89 *** (0.57) |

| lns1_1_1 | |||||||||||

| Constant | −0.02 (0.12) | −0.16 (0.15) | −0.24 (0.16) | −0.42 ** (0.16) | −0.64 *** (0.19) | −0.63 *** (0.18) | −0.64 *** (0.19) | −0.65 *** (0.19) | −1.96 *** (0.18) | −2.03 *** (0.19) | −2.18 *** (0.22) |

| lnsig_e | |||||||||||

| Constant | 0.73 *** (0.02) | 0.73 *** (0.02) | 0.72 *** (0.02) | 0.72 *** (0.02) | 0.68 *** (0.02) | 0.67 *** (0.02) | 0.67 *** (0.02) | 0.67 *** (0.02) | 0.67 *** (0.00) | 0.67 *** (0.00) | 0.67 *** (0.00) |

| lns1_1_2 | |||||||||||

| Constant | −0.65 *** (0.15) | −0.67 *** (0.15) | −0.66 *** (0.15) | ||||||||

| atr1_1_1_2 | |||||||||||

| Constant | 0.99 *** (0.29) | 0.99 *** (0.28) | 1.13 ** (0.35) | ||||||||

| ICC | 0.1829 | 0.1428 | 0.1273 | 0.0937 | 0.0671 | 0.0687 | 0.0678 | 0.0668 | 0.0661 | 0.0671 | 0.06 |

| DEF | 300.15 | 234.67 | 209.30 | 154.17 | 110.66 | 113.30 | 111.95 | 108.32 | 109.10 | 110.74 | 106.39 |

| N | 37,638 | 37,638 | 37,638 | 37,638 | 37,638 | 37,638 | 37,638 | 37,638 | 37,638 | 37,638 | 37,638 |

| Standard errors in parentheses. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001. | |||||||||||

References

- Sachs, J.D. The Age of Sustainable Development; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015; ISBN 978-0-231-17315-5. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, T.; Rocha, J.C.; Berry, K.; Chaigneau, T.; Hamann, M.; Lindkvist, E.; Qiu, J.; Schill, C.; Shepon, A.; Crépin, A.-S.; et al. Triple Bottom Line or Trilemma? Global Tradeoffs Between Prosperity, Inequality, and the Environment. World Dev. 2024, 178, 106595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weymouth, R.; Hartz-Karp, J.; Marinova, D. Repairing Political Trust for Practical Sustainability. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brechin, S.; Kempton, W. Global Environmentalism: A Challenge to the Postmaterialism Thesis? Soc. Sci. Q. 1994, 75, 245–269. [Google Scholar]

- Fairbrother, M.; Arrhenius, G.; Bykvist, K.; Campbell, T. Governing for Future Generations: How Political Trust Shapes Attitudes towards Climate and Debt Policies. Front. Political Sci. 2021, 3, 656053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, T.; Zhang, Y. Government Institutional Trust and Sustainable Environment: Evidence from BRICS Economies. Econ. Res.-Ekon. Istraživanja 2023, 36, 2164032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banik, D. Democracy and Sustainable Development. Anthr. Sci. 2022, 1, 233–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalton, R.J. Democratic Challenges, Democratic Choices: The Erosion of Political Support in Advanced Industrial Democracies; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2004; ISBN 978-0-19-170857-2. [Google Scholar]

- Kestilä-Kekkonen, E.; Söderlund, P. Political Trust, Individual-Level Characteristics and Institutional Performance: Evidence from Finland, 2004–2013. Scand. Political Stud. 2016, 39, 138–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghion, P.; Caroli, E.; García-Peñalosa, C. Inequality and Economic Growth: The Perspective of the New Growth Theories. J. Econ. Lit. 1999, 37, 1615–1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkire, S.; Foster, J.; Seth, S.; Santos, M.E.; Roche, J.M.; Ballón, P. Multidimensional Poverty Measurement and Analysis; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hellier, J.; Chusseau, N. (Eds.) Growing Income Inequalities: Economic Analyses; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2013; ISBN 978-0-230-30342-3. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins, S.P.; Kerm, P.V. The Measurement of Economic Inequality. Available online: https://www.oxfordhandbooks.com/view/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199606061.001.0001/oxfordhb-9780199606061-e-3 (accessed on 27 November 2020).

- Ravallion, M. The Economics of Poverty: History, Measurement, and Policy; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2016; ISBN 978-0-19-021276-6. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis-Beck, M.S.; Paldam, M. Economic Voting: An Introduction. Elect. Stud. 2000, 19, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAllister, I. The Economic Performance of Governments. In Critical Citizens: Global Support for Democratic Government; Norris, P., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1999; pp. 188–203. ISBN 978-0-19-829568-6. [Google Scholar]

- Catterberg, G.; Moreno, A. The Individual Bases of Political Trust: Trends in New and Established Democracies. Int. J. Public Opin. Res. 2006, 18, 31–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Meer, T.; Hakhverdian, A. Political Trust as the Evaluation of Process and Performance: A Cross-National Study of 42 European Countries. Political Stud. 2017, 65, 81–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magalhães, P.C. Economic Outcomes, Quality of Governance, and Satisfaction with Democracy. In Myth and Reality of the Legitimacy Crisis: Explaining Trends and Cross-National Differences in Established Democracies; van Ham, C., Thomassen, J., Aarts, K., Andeweg, R., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2017; ISBN 978-0-19-879371-7. [Google Scholar]

- Dellmuth, L. Regional Inequalities and Political Trust in a Global Context. J. Eur. Public Policy 2023, 31, 1516–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Meer, T.M.G. Economic Performance and Political Trust. In The Oxford Handbook of Social and Political Trust; Uslaner, E.M., Ed.; Oxford Handbooks; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2018; pp. 599–611. ISBN 978-0-19-027480-1. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, C.J.; Tverdova, Y.V. Corruption, Political Allegiances, and Attitudes Toward Government in Contemporary Democracies. Am. J. Political Sci. 2003, 47, 91–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabbi, M.; Osei, A.; Wigmore-Shepherd, D.; Ahlin, E. Minding the Local Slot: Municipalities as Drivers of Trust in Public Institutions. Can. J. Afr. Stud. Rev. Can. Des Études Afr. 2024, 58, 301–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braithwaite, V.A.; Levi, M. (Eds.) Trust and Governance; Russell Sage Foundation: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, C.; Jiang, J.; Zhang, Y. Political Trust and Government Performance in the Time of COVID-19. World Dev. 2024, 176, 106499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yu, X. Trust, Political Knowledge and Institutionalized Political Participation: Evidence from China. Curr. Psychol. 2023, 42, 15019–15029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stals, L.; Isac, M.M.; Claes, E. Political Trust in Early Adolescence and Its Association with Intended Political Participation: A Cross-Sectional Study Situated in Flanders. Young 2022, 30, 377–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, W. Trust and Corruption: How Different Forms of Trust Interact with Formal Institutions. Glob. Public Policy Gov. GPPG 2023, 3, 160–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauhr, M.; Charron, N. Corruption and Political Trust: How the Effect of Societal Cleavages on Trust Depend on the Corruption Context. In Handbook on Trust in Public Governance; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2025; pp. 292–307. ISBN 978-1-80220-140-6. [Google Scholar]

- Dolan, P.; Peasgood, T.; White, M. Do We Really Know What Makes Us Happy? A Review of the Economic Literature on the Factors Associated with Subjective Well-Being. J. Econ. Psychol. 2008, 29, 94–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danish, M.H.; Nawaz, S.M.N. Does Institutional Trust and Governance Matter for Multidimensional Well-Being? Insights from Pakistan. World Dev. Perspect. 2022, 25, 100369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berliani, A.D.; Violita, E.S. The Role of Governance in SDG through Public Trust in Government: Study in Selected OIC Member States. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 716, 012100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thinyane, M. Engaging Citizens for Sustainable Development: A Data Perspective; United Nations University: Tokyo, Japan, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Budanov, K.; Vereshchak, V.; Kudriavtsev, V.; Mokliak, S.; Rubel, K. Peace and Development: A Strategy for Global Engagement. Rev. Cercet. Si Interv. Soc. RCIS 2025, 20, 48–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishler, W.; Rose, R. What Are the Origins of Political Trust?: Testing Institutional and Cultural Theories in Post-Communist Societies. Comp. Political Stud. 2001, 34, 30–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, J.S. Foundations of Social Theory; Belknap Press of Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1990; ISBN 978-0-674-31225-8. [Google Scholar]

- Hetherington, M.J. The Political Relevance of Political Trust. Am. Political Sci. Rev. 1998, 92, 791–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallier, K. Trust in a Polarized Age; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2020; ISBN 978-0-19-088722-3. [Google Scholar]

- Easton, D. A Re-Assessment of the Concept of Political Support. Br. J. Political Sci. 1975, 5, 435–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomassen, J.; Andeweg, R.; Ham, C. van Political Trust and the Decline of Legitimacy Debate: A Theoretical and Empirical Investigation into Their Interrelationship. In Handbook on Political Trust; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2017; pp. 509–525. ISBN 978-1-78254-511-8. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, C. Institutional Change, Economic Conditions and Confidence in Government: Evidence from Belgium. Acta Politica 2009, 44, 28–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.; Chang, C.Y.; Hur, H. Economic Performance, Income Inequality and Political Trust: New Evidence from a Cross-National Study of 14 Asian Countries. Asia Pac. J. Public Adm. 2020, 42, 66–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, A.; Listhaug, O. Political Performance and Institutional Trust. In Critical Citizens: Global Support for Democratic Government; Norris, P., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1999; ISBN 978-0-19-829568-6. [Google Scholar]

- Van Erkel, P.F.A.; van der Meer, T.W.G. Macro-Economic Performance, Political Trust, and the Great Recession: A Multilevel Analysis of the Effects of within-Country Fluctuations in Macroeconomic Performance on Political Trust in 15 EU Countries, 1999-2011. Eur. J. Political Res. 2016, 55, 177–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergbauer, S.; Giovannini, A.; Hernborg, N. Economic Inequality and Public Trust in the European Central Bank. Econ. Bull. Artic. 2022, 3, 1671843. [Google Scholar]

- Adeleye, B.N.; Gershon, O.; Ogundipe, A.; Owolabi, O.; Ogunrinola, I.; Adediran, O. Comparative Investigation of the Growth-Poverty-Inequality Trilemma in Sub-Saharan Africa and Latin American and Caribbean Countries. Heliyon 2020, 6, e05631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuznets, S. Economic Growth and Income Inequality. Am. Econ. Rev. 1955, 45, 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Amponsah, M.; Agbola, F.W.; Mahmood, A. The Relationship between Poverty, Income Inequality and Inclusive Growth in Sub-Saharan Africa. Econ. Model. 2023, 126, 106415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Victora, C.G.; Hartwig, F.P.; Vidaletti, L.P.; Martorell, R.; Osmond, C.; Richter, L.M.; Stein, A.D.; Barros, A.J.D.; Adair, L.S.; Barros, F.C.; et al. Effects of Early-Life Poverty on Health and Human Capital in Children and Adolescents: Analyses of National Surveys and Birth Cohort Studies in LMICs. Lancet 2022, 399, 1741–1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Yang, W.; Zhao, K. The Impact of Income Inequality on Health Levels: Empirical Evidence from China: 2002–2016. Soc. Work. Public Health 2024, 39, 335–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barro, R.J. Inequality and Growth in a Panel of Countries. J. Econ. Growth 2000, 5, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamasauskiene, Z.; Dilius, A. The Impact of Income Inequality on Economic Growth Through Channels in the European Union. In Eurasian Economic Perspectives; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 315–330. ISBN 978-3-030-40375-1. [Google Scholar]

- Alesina, A.; Perotti, R. Income Distribution, Political Instability, and Investment. Eur. Econ. Rev. 1996, 40, 1203–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jianu, I.; Dinu, M.; Huru, D.; Bodislav, A. Examining the Relationship between Income Inequality and Growth from the Perspective of EU Member States’ Stage of Development. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Policardo, L.; Sanchez Carrera, E.J. Wealth Inequality and Economic Growth: Evidence from the US and France. Socio-Econ. Plan. Sci. 2024, 92, 101804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; Yahong, W.; Zeeshan, A. Impact of Poverty and Income Inequality on the Ecological Footprint in Asian Developing Economies: Assessment of Sustainable Development Goals. Energy Rep. 2022, 8, 670–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Dong, K.; Ren, X. Would Narrowing the Income Gap Help Mitigate the Greenhouse Effect? Fresh Insights from Spatial and Mediating Effects Analysis. Energy Ecol. Environ. 2024, 9, 241–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, R. Support for Democracy in Cross-National Perspective: The Detrimental Effect of Economic Inequality. Res. Soc. Stratif. Mobil. 2012, 30, 389–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsässer, L.; Schäfer, A. Political Inequality in Rich Democracies. Annu. Rev. Political Sci. 2023, 26, 469–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solt, F. Economic Inequality and Democratic Political Engagement. Am. J. Political Sci. 2008, 52, 48–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bienstman, S. Does Inequality Erode Political Trust? Front. Political Sci. 2023, 5, 1197317. [Google Scholar]

- Zmerli, S.; Castillo, J.C. Income Inequality, Distributive Fairness and Political Trust in Latin America. Soc. Sci. Res. 2015, 52, 179–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goubin, S.; Hooghe, M. The Effect of Inequality on the Relation Between Socioeconomic Stratification and Political Trust in Europe. Soc. Just Res. 2020, 33, 219–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipps, J.; Schraff, D. Regional Inequality and Institutional Trust in Europe. Eur. J. Political Res. 2021, 60, 892–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gould, E.; Hijzen, A. Growing Apart, Losing Trust? The Impact of Inequality on Social Capital; IMF Working Paper; International Monetary Fund: Washington, DC, USA, 2016; p. 46. [Google Scholar]

- Gustavsson, M.; Jordahl, H. Inequality and Trust in Sweden: Some Inequalities Are More Harmful than Others. J. Public Econ. 2008, 92, 348–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, C.; Frieden, J. Crisis of Trust: Socio-Economic Determinants of Europeans’ Confidence in Government. Eur. Union Politics 2017, 18, 511–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchison, M.L.; Xu, P. Trust in China? The Impact of Development, Inequality, and Openness on Political Trust across China’s Provinces, 2001–2012. Asian J. Comp. Politics 2017, 2, 176–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKay, L.; Jennings, W.; Stoker, G. What Is the Geography of Trust? The Urban-Rural Trust Gap in Global Perspective. Political Geogr. 2023, 102, 102863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inglehart, R. Trust, Well-Being and Democracy. In Democracy and Trust; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1999; pp. 88–120. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, C.J.; Singer, M.M. The Sensitive Left and the Impervious Right: Multilevel Models and the Politics of Inequality, Ideology, and Legitimacy in Europe. Comp. Political Stud. 2008, 41, 564–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ESS Round 9: European Social Survey Round 9 Data 2018.

- Hooghe, M. Why There Is Basically Only One Form of Political Trust. Br. J. Politics Int. Relat. 2011, 13, 269–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marien, S. The Effect of Electoral Outcomes on Political Trust: A Multi–Level Analysis of 23 Countries. Elect. Stud. 2011, 30, 712–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, R.; Maritz, A.; Lobo, A. Evaluating Entrepreneurs’ Perception of Success: Development of a Measurement Scale. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2014, 20, 478–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uslaner, E.M. The Moral Foundations of Trust; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2002; ISBN 978-0-521-81213-9. [Google Scholar]

- Zmerli, S.; Newton, K. Social Trust and Attitudes Toward Democracy. Public Opin. Q. 2008, 72, 706–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newton, K. Social and Political Trust in Established Democracies. In Critical Citizens: Global Support for Democratic Government; Norris, P., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1999; pp. 169–187. ISBN 978-0-19-829568-6. [Google Scholar]

- Peugh, J.L. A Practical Guide to Multilevel Modeling. J. Sch. Psychol. 2010, 48, 85–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dahl, R.A. On Political Equality; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 2007; ISBN 978-0-300-12687-7. [Google Scholar]

| Variable | Description | Mean | Standard Deviation | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variables | |||||

| Index of political trust | Average of the following indicators: Trust in parliament; Trust in politicians; Trust in political parties. | 3.924 | 2.285 | 0 | 10 |

| Independent Variables | |||||

| First-Level (Individual) | |||||

| Perceived household’s income—cluster-mean centered | Which of the descriptions on this card comes closest to how you feel about your household’s income nowadays? 1—Living comfortably on present income 2—Coping on present income 3—Difficult on present income 4—Very difficult on present income | −0.018 | 0.84 | −2.038 | 0.962 |

| Level of general trust—cluster-mean centered | Most people can be trusted or you can’t be too careful in dealing with people? 0 means you can’t be too careful, and 10 most people can be trusted. | 0.017 | 2.455 | −5.061 | 4.938 |

| Gender | 1—male, 2—female. | 1.535 | 0.499 | 1 | 2 |

| Age | 52.135 | 18.072 | 15 | 90 | |

| Type of economic activity | What you have been doing for the last 7 days? | ||||

| Paid work | 0—No, 1—Yes | 0.537 | 0.499 | 0 | 1 |

| Education | 0—No, 1—Yes | 0.067 | 0.25 | 0 | 1 |

| Unemployed, actively looking for a job | 0—No, 1—Yes | 0.032 | 0.176 | 0 | 1 |

| Unemployed, not actively looking for a job | 0—No, 1—Yes | 0.021 | 0.142 | 0 | 1 |

| Permanently sick or disabled | 0—No, 1—Yes | 0.030 | 0.171 | 0 | 1 |

| Retired | 0—No, 1—Yes | 0.295 | 0.456 | 0 | 1 |

| Community or military service | 0—No, 1—Yes | 0.001 | 0.031 | 0 | 1 |

| Housework, looking after children, others | 0—No, 1—Yes | 0.155 | 0.361 | 0 | 1 |

| Other | 0—No, 1—Yes | 0.017 | 0.129 | 0 | 1 |

| Second-Level (Country) | |||||

| Gini index | Gini coefficient of equivalized disposable income 2019, % | 29.348 | 4.197 | 22.8 | 40.8 |

| Regional differences in GDP per capita for major socio-economic regions | GDP at current market prices—Euro per inhabitant in percentage of the EU average 2000 | 104.693 | 45.683 | 20 | 232 |

| A | B | C | D | E | F | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Random Intercept Effects Only | Random Intercept Effects and Random Slope Effects | |||||

| Country Level | ||||||

| Gini | −0.0652 **/(0.0199) | −0.0701 ***/(0.0212) | −0.0682 ***/(0.0197) | −0.0411 */(0.0191) | −0.0684 **/(0.0264) | −0.0451 */(0.0188) |

| Regional differences in GDP | 0.0041 ***/(0.0007) | 0.0041 ***/(0.0007) | 0.0041 ***/(0.0007) | 0.0038 ***/(0.0006) | 0.0038 ***/(0.0006) | 0.0040 ***/(0.0006) |

| Individual level | ||||||

| Income | 0.3030 ***/(0.0310) | 0.6513 ***/(0.1793) | 0.1527 **/(0.0524) | 0.3173 ***/(0.0327) | 0.6469 **/(0.2184) | 0.2333 ***/(0.0448) |

| Generalized trust | 0.2610 ***/(0.0161) | 0.2609 ***/(0.0161) | 0.2606 ***/(0.0161) | 0.2600 ***/(0.0045) | 0.2600 ***/(0.0045) | 0.2600 ***/(0.0045) |

| Intersection | ||||||

| Income × Gini | −0.0117 */(0.0056) | −0.0112/(0.0074) | ||||

| Income × Regional differences in GDP | 0.0015 **/(0.0005) | 0.0009 */(0.0004) | ||||

| Constant | 5.4562 ***/(0.6748) | 5.5756 ***/(0.7141) | 5.5300 ***/(0.6745) | 4.8099 ***/(0.5906) | 5.5528 ***/(0.7929) | 4.9096 ***/(0.5771) |

| lns1_1_1 | 5.4805 ***/(0.6773) | 5.6083 ***/(0.7180) | 5.5569 ***/(0.6769) | 4.7861 ***/(0.5866) | 5.5867 ***/(0.7914) | 4.8864 ***/(0.5738) |

| Constant | ||||||

| lnsig_e | −0.6315 ***/(0.1854) | −0.6382 ***/(0.1875) | −0.6525 ***/(0.1871) | −1.9635 ***/(0.1830) | −2.0325 ***/(0.1904) | −2.1811 ***/(0.2204) |

| Constant | ||||||

| lns1_1_2 | 0.6722 ***/(0.0194) | 0.6720 ***/(0.0194) | 0.6717 ***/(0.0195) | 0.6708 ***/(0.0036) | 0.6708 ***/(0.0036) | 0.6708 ***/(0.0036) |

| Constant | ||||||

| atr1_1_1_2 | −0.6452 ***/(0.1537) | −0.6669 ***/(0.1500) | −0.6583 ***/(0.1525) | |||

| AIC | 157,555.44 | 157,542.20 | 157,518.05 | 157,478.87 | 157,478.69 | 157,477.31 |

| BIC | 157,709.08 | 157,704.38 | 157,680.23 | 157,649.59 | 157,657.94 | 157,656.56 |

| N | 37,638 | 37,638 | 37,638 | 37,638 | 37,638 | 37,638 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Revtiuk, Y.; Zelinska, O. Toward Sustainability: Examining Economic Inequality and Political Trust in EU Countries. Sustainability 2026, 18, 210. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010210

Revtiuk Y, Zelinska O. Toward Sustainability: Examining Economic Inequality and Political Trust in EU Countries. Sustainability. 2026; 18(1):210. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010210

Chicago/Turabian StyleRevtiuk, Yevhen, and Olga Zelinska. 2026. "Toward Sustainability: Examining Economic Inequality and Political Trust in EU Countries" Sustainability 18, no. 1: 210. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010210

APA StyleRevtiuk, Y., & Zelinska, O. (2026). Toward Sustainability: Examining Economic Inequality and Political Trust in EU Countries. Sustainability, 18(1), 210. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010210