Abstract

The pursuit of low-carbon economic development represents an inherent requirement for implementing the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and serves as a vital support for advancing SDG 7, SDG 9, and SDG 13. Drawing on provincial data from China (2006–2023), this research investigates how digital-real convergence influences low-carbon economic development. The results demonstrate a positive contribution of this convergence to growth in the low-carbon economy, and it proves to be superior to models reliant solely on either digital-digital or real-real convergence. A notable finding is the considerable regional variation in the effect. It is strong in both eastern and western parts of the country, which stands in sharp contrast to central China, where the effect is statistically insignificant or negative. Identified as underlying mechanisms are the agglomeration of innovative talent and the accumulation of innovative capital. Additionally, a single-threshold effect of urbanization level is identified, indicating that the positive impact strengthens only after urbanization surpasses a critical value. Furthermore, digital-real convergence not only enhances local low-carbon development but also generates positive spillover effects on neighboring regions. Thus, to fully advance the SDGs, policy formulation and implementation must account for regional heterogeneity, prioritize the elevation of urbanization levels, enhance cross-regional collaboration, and amplify the enabling role of digital-real integration.

1. Introduction

Addressing global climate change and implementing the 2030 Sustainable Development Agenda have made the green and low-carbon transition a common action plan for countries worldwide [1]. Multiple targets under this agenda (including SDG7, SDG9, and SDG13) all emphasize optimizing energy systems, upgrading industrial structures, and realizing deep decarbonization [2]. China’s launch of the carbon neutrality targets represents a significant commitment to balancing domestic sustainable development with its responsibility in global climate governance. However, China’s current low-carbon transition continues to face structural constraints: the heavy reliance on coal in the energy mix and the predominance of energy-intensive industries remain unresolved [3], while bottlenecks persist in green technology innovation and large-scale application. Additionally, the carbon market and green financial systems require further refinement [4,5]. These challenges constrain the improvement of development quality, creating an urgent need to introduce systemic innovation drivers.

Under this context, the convergence of the digital economy and the real economy (termed “digital-real convergence”) provides a novel solution to sustainability-related challenges [6]. By boosting the clustering and efficient allocation of innovation factors like capital and talent, it continuously refines corporate production and organizational models, elevates energy use efficiency, and in turn speeds up regional low-carbon progress. Building on this logic, this research intends to establish an analytical framework of “convergence, factor clustering, low-carbon transition” to empirically explore the mechanisms and spatial impacts of digital-real convergence on low-carbon transformation. The objective is to offer institutional-level evidence and decision-making references for advancing the UN 2030 Sustainable Development Agenda, especially its SDG9 (Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure) and SDG13 (Climate Action) targets.

As per Klarin’s (2018) analysis of sustainable development’s conceptual evolution, its core rests on balancing the three pillars of economy, society, and environment, the so-called “triple bottom line” principle, which seeks to harmonize economic expansion, social fairness, and environmental conservation [7]. Manioudis (2022) further proposes that sustainable development should revert to the macro-theoretical foundation of classical political economy, framing it as a far-reaching systemic shift that encompasses historical phases, social structures, and production patterns [8]. Within this theoretical framework, the low-carbon economy can be seen as a concrete practice and critical pathway for sustainable development in the field of climate governance [9]. It not only entails “decoupling” economic growth from carbon emissions through improved energy efficiency, clean energy substitution, and innovation-driven strategies [10], but also, from a systemic transformation perspective, translates the concept of sustainable development into actionable and observable processes—namely, driving comprehensive greening transformations in production models, consumption behaviors, and even the entire socio-economic governance system [11]. Therefore, this paper posits that low-carbon transition inherently carries the multidimensional goal-oriented connotation of sustainable development, coordinating economic, social, and environmental objectives. It serves as a critical practical arena for achieving the “triple bottom line” balance and promoting big systemic change.

When evaluating low-carbon development levels, prior research has devised multiple analytical methods, including the Analytic Hierarchy Process and Principal Component Analysis [12,13], and made headway in depicting the regional low-carbon development characteristics across China. These mature methods lay the groundwork for follow-up interdisciplinary research [14,15]. The emergence of the digital economy opens up a fresh lens to interpret low-carbon transformation. Relevant studies indicate that the digital economy can drive emission cuts via three key channels: improving resource allocation efficiency [16,17], boosting production effectiveness, and advancing green technological innovation [18]. Examples include smart grids optimizing energy dispatch and digital platforms facilitating synergistic carbon reduction in industrial chains [19,20,21]. However, most existing studies tend to focus on the independent functions of either the digital economy or the real economy in isolation. They lack a comprehensive lens centered on digital-real convergence, which would allow for a systematic exploration of how the merging of these two sectors shapes relevant outcomes. As industrial convergence trends deepen, research on this holistic effect has become particularly urgent.

With the advancement of research, academics have started to delve into the systemic influences of digital-real convergence, a type of industrial transformation, on the low-carbon economic development of different regions. However, most findings remain confined to case studies. For instance, while case studies on industrial internet or smart logistics reveal the emission reduction potential of technological applications [22,23,24], they lack a generalizable theoretical framework and often overlook the mediating effects of key factors such as innovation factor agglomeration. Additionally, some studies highlight potential challenges, such as the “rebound effect” associated with digital economy development and its own energy consumption growth [25], which may also negatively impact the low-carbon economy.

To address these research deficiencies, this paper makes three marginal contributions: First, this study examines digital-real convergence within the overarching framework of the SDGs, thereby constructing a theoretical analytical framework to clarify its role in advancing low-carbon economic transformation. Specifically, it delineates how digital-real convergence facilitates the coordinated realization of SDG7, SDG9, and SDG13 by driving the clustering of innovation factors. Second, this study leverages both Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) and Spatial Durbin Models (SDM) to empirically examine three dimensions of digital-real convergence’s influence on the low-carbon economy: its direct effects, the heterogeneous traits across different regions, and the associated spatial spillover impacts. This addresses the lack of micro-mechanism evidence in existing studies and provides empirical insights into regional linkages and potential international cooperation in the low-carbon transition. Finally, the study proposes a differentiated policy system aimed at fostering synergy between digital-real convergence and low-carbon transition at the regional level. This offers theoretically grounded and practically relevant decision-making support for China’s implementation of its “dual carbon” goals and its participation in global sustainable development governance.

2. Theoretical Analysis and Research Hypothesis

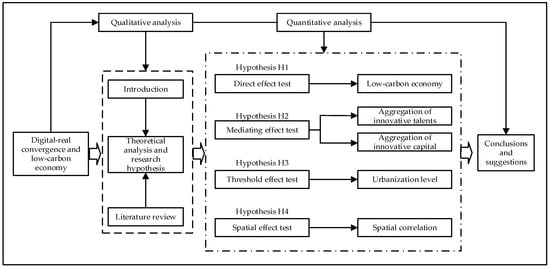

As production factors shift toward intangible components like intelligence and knowledge, digital-real convergence is emerging as a critical driver of low-carbon economic progress. Its core functional path is reflected in two major agglomeration effects. First, it attracts high-level innovative talents to provide intellectual support for breakthroughs in green technologies. Second, guide innovative capital to converge in the low-carbon sector, injecting continuous impetus into the green transformation of industries. This study will systematically dissect how the digital-real convergence empowers low-carbon economic development, focusing on the two dimensions of innovative talent clustering and innovative capital concentration. Figure 1 shows the mechanism path diagram.

Figure 1.

Mechanism Path Diagram.

2.1. Direct Effect Analysis

Digital technology notably boosts resource allocation efficiency via functions like information sensing, real-time data transmission, and intelligent analysis [26], which in turn mitigates resource misallocation and energy waste [27]. This drives down per-unit output energy use and carbon emissions, shaping a resource-efficient utilization model. Second, the integration of digital technology into physical industrial processes drives production methods toward intensification and intelligence. By optimizing process parameters, improving equipment efficiency, and enabling tracking and adjustment of emission sources, it strengthens environmental performance management and facilitates life-cycle improvements [28]. Finally, digital technology enhances supply chain collaboration, establishing a low-carbon-oriented systemic response mechanism. Promoting data sharing and process integration effectively reduces transaction costs and breaks down coordination barriers [29], thereby driving coordinated cross-regional emission reduction actions and ultimately building a more climate-resilient economic system.

Hypothesis H1:

Digital-real convergence plays a key role in advancing the development of a low-carbon economy.

2.2. Indirect Effect Analysis

The digital-real convergence indirectly drives low-carbon economic advancement by accelerating the clustering of innovation factors. This clustering of innovation factors primarily unfolds in two dimensions: the gathering of innovative talent and the concentration of innovative capital.

2.2.1. The Mediating Effect of Innovative Talent Aggregation

Digital-real convergence reshapes industrial organization models and removes barriers to factor flow, creating a strong impetus for the agglomeration and collaboration of innovative talents [30]. The structure of the labor market is reshaped by the digital economy, directing talent flow toward high-value sectors. Leveraging digital platforms, it builds an open innovation ecosystem [31], fostering cross-domain knowledge sharing and collaboration. Meanwhile, new employment models and flexible work arrangements reduce the costs associated with talent mobility [32], encouraging the concentration of highly skilled labor in technology-intensive industrial clusters. This not only boosts the innovation capabilities of regions but also consolidates enterprises’ leading position in the R&D of green technologies.

The clustering of innovative talent is pivotal to advancing low-carbon economic development. On one side, the knowledge spillover effects and innovation networks generated by talent agglomeration speed up the R&D and upgrading of low-carbon technologies (such as clean energy [33] and energy efficiency enhancement), which in turn boost resource utilization efficiency. On the other side, the flexible thinking of innovative talent allows for more effective identification and exploitation of green innovation opportunities, cutting down on resource waste and R&D risks [34]. Additionally, the diverse backgrounds of such talent facilitate the absorption, adaptation, and diffusion of green technologies, opening up new pathways for green innovation [35].

2.2.2. The Mediating Effect of Innovative Capital Agglomeration

Digital-real convergence notably boosts the concentration of innovation capital by refining resource allocation and amplifying innovation synergy. Digital technology elevates information openness, cuts down transaction expenses, and boosts market matching effectiveness [36], which in turn enhances capital’s capacity to recognize and steer innovation initiatives. Through digital platforms, the financing needs of innovation projects are more precisely aligned with capital markets, accelerating the formation of innovation capital [37]. Meanwhile, the application of digital infrastructure and data as a production factor reshapes the innovation ecosystem, making feedback among R&D, production, and service processes more efficient. This attracts more venture capital and industrial funds toward high-tech sectors, forming a capital agglomeration pattern centered on technological innovation, which lays the foundation for capital investment in low-carbon fields.

The agglomeration of innovation capital, fueled mainly by advancements in green technological solutions and the upgrading of industrial frameworks, serves as a core driver that underpins the growth of a low-carbon economy. On one side, aggregated capital offers steady backing for R&D into cutting-edge low-carbon technologies, allowing high-risk, long-cycle emission reduction projects to advance smoothly and speeding up technological upgrades in key fields like energy efficiency enhancement and clean energy replacement [38]. On the other side, capital clustering drives the industrialization of low-carbon technological outcomes [39]: through capital-powered large-scale applications, it pushes decarbonization upgrades in traditional industries and nurtures the formation of green industrial chains. The leverage effect of capital amplifies the positive spillover effects of technological innovation, infusing endogenous growth impetus into low-carbon development and thus boosting the reach and spread of low-carbon technologies across the economic system.

Hypothesis H2:

The clustering of innovative talent and innovation capital plays a mediating role, specifically, the digital-real convergence indirectly drives low-carbon economic development by boosting the aggregation of these innovative talents and capital.

2.3. Threshold Effect Analysis

When urbanization is at a low level, limited urban infrastructure carrying capacity, low resource allocation efficiency, and poor information flow hinder the effective integration of digital technologies into the physical production system [40]. Under such conditions, urban operations remain relatively inefficient, motivation for digital transformation is insufficient, and the response of the physical sector to technological adoption is slow. As a result, digital-real convergence does not yet demonstrate a clear inhibitory effect on carbon emissions. Weak governance capacity at low urbanization levels further undermines the transmission pathway through which digitalization enables low-carbon development.

When urbanization surpasses a certain threshold, urban spatial structures, public services, and industrial organization become more mature, providing favorable conditions for digital-real convergence [41]. Cities can efficiently integrate data and physical resources, promoting the intelligent, networked, and green restructuring of production processes. Leveraging functions such as real-time monitoring and dynamic scheduling, digital technology effectively empowers energy systems. It not only enhances their responsiveness and resource recycling capabilities but also strengthens the endogenous momentum for the low-carbon transition of the real economy [42]. The scale and network advantages of urbanization work together to boost technology spillover and systematic coordination, allowing the carbon emission reduction benefits brought by digital-real convergence to be fully unleashed.

Hypothesis H3:

The urbanization level exhibits a threshold effect. When urbanization remains at a relatively low stage, the digital-real convergence has no notable influence on low-carbon development. By contrast, once urbanization reaches a relatively high level, this convergence will produce a clear amplifying effect.

2.4. Spatial Spillover Effect Analysis

The digital-real convergence in a region generates positive spillover impacts on the low-carbon transformation of adjacent areas via spatial interaction effects. Building on geographic proximity, the data-driven, intelligently regulated low-carbon production systems developed locally, along with practical experiences in improving energy efficiency and carbon management, provide tangible technological and institutional models for the surrounding areas. This “demonstration effect” helps reduce trial-and-error costs and uncertainties in the neighboring regions’ transition processes [43], facilitating the cross-regional diffusion of low-carbon development concepts and practical models.

The ubiquitous connectivity of new digital infrastructure [44] provides the foundation for the rapid flow and sharing of relevant technologies and concepts within regions [45], thereby effectively elevating the level of green technology innovation in surrounding areas. [46]. Meanwhile, the cross-regional layout of industrial chains, empowered by digital technologies, drives the regional integration of mechanisms such as green standards and carbon footprint tracking. The synergistic innovation between the digital industry and other sectors strengthens the interconnectivity of innovation activities across different regions through cross-regional linkages [47], forming a chain-like green upgrading effect, and ultimately achieving positive spatial externalities for low-carbon development.

Hypothesis H4:

The digital-real convergence within a region significantly boosts the low-carbon economic progress of its surrounding areas.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Model Design

Based on hypothesis H1, this paper constructs a panel regression model as follows:

Here, denotes the low-carbon economy; corresponds to the digital-real convergence. stands for the control variable; represents the individual and time fixed effects; is the random error term. To examine how the digital-real convergence affects the low-carbon economy, we draw on the approaches of prior researchers [48] and build a stepwise regression model (based on Formula (1)) for validation. The model is presented below:

Here, denotes the concentration of innovative factors, which is primarily categorized into the gathering of innovative talent and the clustering of innovative capital. The definitions of other variables align with those in Formula (1).

3.2. Variable Settings

3.2.1. Dependent Variable

Low-carbon economy (denoted as Low-car). Refer to the study by Fu et al. (2011) [14], we have built an evaluation index system covering five dimensions. Here, low-carbon output mainly reflects the carbon emission efficiency of economic activities, low-carbon consumption measures the carbon emission levels in residents’ lives and government operations, low-carbon resources mainly assess carbon sink capacity and total carbon emissions, low-carbon policies center on the design and execution of environment-oriented policy measures, while the low-carbon environment focuses on the effectiveness of industrial “three wastes” treatment. In terms of the measurement method, a combined approach combining the analytic hierarchy process (or expert consultation) and data envelopment analysis is adopted for a comprehensive assessment. As shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Evaluation index system for low-carbon economy.

Specific calculation methods (For other detailed calculation methods and steps, please refer to the “Supplementary Material” of this manuscript):

First, standardize the data, including the forward adjustment of indicators and dimensionless processing. For reverse indicators, the reciprocal transformation method is applied for forward adjustment (Formula (4)). Dimensionless processing of indicators is carried out using normalization (Formula (5)), as shown below:

Second, perform index composition, including the synthesis of individual index values and the composite index (expressed on a 100-point scale). We adopt the linear weighted summation method to compute the value of each index (Formula (6)), where represents the i-th index value in the evaluation of low-carbon economic development capacity, and i is the five secondary indices mentioned above. The standardized dimensionless indicators are denoted as , and the corresponding sub-weight of each indicator is denoted as . We use the linear weighted summation method to compute the low-carbon economic development level index (Formula (7)). Here, LCEI refers to the low-carbon economic development level index, and denotes the weight assigned to each index.

3.2.2. Independent Variable

Digital-real convergence (denoted as Dig-rea). Referencing the findings of Zhou et al. (2024) [49], this paper leverages China’s patent application dataset (covering invention patents, utility models, and design patents). By linking technology and industry correspondences, we convert technology-focused data into industrial integration metrics. Through this process, we calculate the degree of “digital-real convergence”, “digital-digital convergence”, and “real-real convergence”.

3.2.3. Mediating Variable

Agglomeration of innovation elements. For assessing the agglomeration level of each innovation element, we primarily draw on the approach used by Feng et al. (2016) [50], which mainly employs factor analysis. The agglomeration of innovation elements includes the agglomeration of innovation talents (denoted as Inn-tal) and innovation capital (denoted as Inn-cap). As shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Evaluation index for the aggregation level of innovative elements.

3.2.4. Threshold Variable

Urbanization level. Here, urbanization mainly refers to population urbanization, and we employ the ratio of the permanent urban resident population to the total permanent resident population (computed annually at year-end) as the proxy variable for this metric.

3.2.5. Control Variables

Additionally, the following series of control variables are selected in this paper: regional economic development level (denoted as Econ), environmental regulation intensity (denoted as Envi), population density (denoted as Popu), financial development level (denoted as Fina), and human capital level (denoted as Huma). Specifically, Econ is operationalized as the natural logarithm of a region’s per capita GDP. Envi is represented by the share of words related to environmental regulation in the total word count of pertinent textual materials. Popu is determined as the ratio of the year-end permanent resident population to the land area of the region. Fina is represented by the share of total deposits and loans of financial institutions in GDP. Huma uses the current enrollment of higher education institutions as its proxy variable.

3.3. Data Sources

The dataset for this research consists of panel data from 30 provincial-level administrative regions in China (starting in 2006; Tibet, Hong Kong, Macao, and Taiwan are excluded). Since certain data have not been updated to 2024, the panel dataset is truncated at 2023 to maintain data validity. For provinces with partial data missing, linear interpolation is applied to fill in the incomplete entries. Table 3 provides the descriptive statistics of all variables.

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics (n = 540).

4. Empirical Result Analysis

4.1. Analysis of Benchmark Test Results

Conducted in this study is a variance inflation factor (VIF) test on the model variables. The results show a mean VIF of 4.2500, which is below 10, indicating no severe multicollinearity issues.

In Table 4, under the random effects model, the coefficient of digital-real convergence is 2.6290, which is highly significant. After incorporating control variables, the coefficient dropped to 0.8894 but remained significant. In the model that controls for individual and time effects, the coefficient of the independent variable is 0.6005; with further addition of control variables, it is adjusted to 0.4746. Both coefficients remain significant, verifying that digital-real convergence stably promotes the low-carbon economy, though there may be some overestimation of this effect.

Table 4.

Benchmark test results.

To mitigate endogeneity issues, this research employs the 1984 historical number of post and telecommunications bureaus as an instrumental variable in the instrumental variable (IV) estimation framework. Relevant test results show: the first-stage F-statistic is 2619.7, and the minimum eigenvalue statistic is 3898.38. All metrics meet the corresponding thresholds, confirming the validity of the instrumental variable. The IV estimation results indicate a coefficient of 0.4912 for digital-real convergence, which further supports the core conclusion. Among control variables, environmental regulation and financial development level exert significantly positive impacts; economic development shows a negative effect, which may imply that economic growth and carbon emissions have not yet fully decoupled.

4.2. Analysis of Robustness Test Results

This study employs four validation methods: lagging the independent variable, adding new control variables, excluding municipal-level administrative regions, and conducting quantile regression. The robustness test results are presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

Robustness test results.

When we introduce one-period and two-period lags for the independent variable, the estimated coefficients are 0.3922 and 0.3142, respectively, both statistically significant, though exhibiting a downward trend. This suggests that the effect of digital-real convergence persists, but its marginal impact weakens over time. After incorporating a set of additional control variables (including social consumption level, technological innovation, transportation infrastructure, and regional openness), the coefficient remains at 0.5625 and retains its significance. When municipal-level regions are excluded from the sample, the coefficient rises to 0.4960 (still significant), implying that the promoting effect of digital-real convergence is more concentrated in ordinary provincial samples. The quantile regression results show that at the 25th, 50th, and 75th percentiles, the coefficients are 0.6112, 0.5176, and 0.4211, respectively. The significance levels at the 25th and 50th percentiles are higher than that at the 75th percentile, which means the driving effect of digital-real convergence is stronger in regions with less developed low-carbon economies. As the low-carbon development level improves, this marginal contribution gradually declines.

4.3. Analysis of Heterogeneity Test Results

To examine regional heterogeneity, this study conducted regression analysis on samples from three major regions. As shown in Table 6, the coefficient for digital-real convergence in the eastern region is 0.2648; in the central region, the coefficient is −0.4647 but not statistically significant; and in the western region, the coefficient is 2.4530. This indicates clear regional differences in the promoting effect: the eastern region benefits from its developed economic and technological foundation, the western region gains from its lower baseline and policy support, while the central region may not yet exhibit significant convergence effects due to path dependency during its transition phase.

Table 6.

Heterogeneity test results.

Additionally, this study analyzes the heterogeneous effects of three convergence modes: “digital-real convergence”, “digital-digital convergence” (denoted as Dig-dig), and “real-real convergence” (denoted as Rea-rea). The results indicate that digital-real convergence has the largest coefficient (0.4912). Next is digital-digital convergence, with a coefficient of 0.4095, while real-real convergence has a coefficient of only 0.0068. This finding implies that the in-depth convergence of digital-real, by directly optimizing production processes and energy allocation, drives the low-carbon economy most strongly. It outperforms the synergistic models that are limited to either the digital or real economy sectors alone.

4.4. Analysis of Mechanism Path Verification Results

As shown in Table 7, the coefficients of digital-real convergence on innovation talent agglomeration and innovation capital agglomeration are 2.6787 and 0.6147, respectively, which proves that digital-real convergence can effectively drive the agglomeration of these two innovation factors. When the mediating variables are introduced into the baseline regression, the coefficient of digital-real convergence drops to 0.3811 and 0.4344. The coefficients of innovation talent agglomeration and innovation capital agglomeration are 0.0349 and 0.0655, respectively, both showing positive effects. This result indicates that the agglomeration of innovation factors not only directly drives the low-carbon economy but also plays a significant partial mediating role in the process through which digital-real convergence influences it. The internal mechanism behind this is: digital-real convergence builds digital platforms and industrial ecosystems to attract talent and capital into the field of green innovation, and then indirectly enhances the impetus and quality of low-carbon transformation through knowledge spillover, technological synergy, and financial support.

Table 7.

Mechanism path verification results.

5. Extended Discussion and Analysis

5.1. Analysis of the Threshold Effect of Urbanization Level

5.1.1. Construction of Panel Threshold Model

Referring to Hansen’s (1999) threshold model testing method [51], the model is shown below:

Here, denotes the urbanization level; stands for the threshold value. The definitions of other variables are consistent with those in Formula (1).

5.1.2. Analysis of Threshold Value Test Results

According to Table 8, the single threshold, double threshold, and triple threshold values for urbanization level are 0.7351, 0.5550, and 0.5673, respectively. Of these, only the single threshold value meets the 1% significance level requirement: its F-value substantially exceeds the critical values across all intervals. In comparison, the double and triple threshold setups fail to achieve statistical significance. The outcome suggests the presence of a single-threshold mechanism, whereby the urbanization level acts as a critical moderator in the relationship between digital-real convergence and the development of low-carbon regional economies, aligning with theoretical predictions. As such, the single-threshold model meets the necessary test standards.

Table 8.

Threshold value test results.

5.1.3. Analysis of Threshold Effect Test Results

The exhibited relationship between digital-real integration and the low-carbon economy is a markedly nonlinear characteristic. As presented in Table 9, when the urbanization level falls below the threshold of 0.7351, the coefficient of digital-real convergence is 0.1880, showing no statistical significance; however, once this threshold is exceeded, the coefficient jumps to 1.5616. This finding indicates that in the initial phases of urbanization, inadequate digital infrastructure and limited industrial collaboration constrain the role of digital-real convergence in advancing low-carbon transformation. As urbanization progresses, improved network facilities, a more dynamic innovation environment, and updated production models create favorable conditions for digital-real convergence, thereby substantially enhancing its driving impact on the low-carbon economy.

Table 9.

Threshold effect test results.

5.2. Analysis of Spatial Spillover Effect

5.2.1. Model Construction

The model is shown below:

Among them, represents the spatial weight matrix. When j = 1 and j = 2, it corresponds to the geographic and the economic matrix, respectively; ρ stands for the spatial autoregressive coefficient; and is an estimated parameter, reflecting the local impact of the influence. represents the spatial effect parameter, which has three scenarios: < 0 indicates a negative spillover effect, > 0 indicates a positive spillover effect, and = 0 means no spatial spillover effect exists.

5.2.2. Analysis of Global Autocorrelation Test Results

A widely adopted, reliable method for this purpose is the global spatial autocorrelation test. The Moran index, a key statistical measure for assessing spatial agglomeration traits, is commonly applied to identify the correlation patterns of variables across spatial distributions. As shown in the global autocorrelation test results (Table 10), between 2006 and 2023, the global Moran indices for both digital-real convergence and low-carbon economic development took positive values and passed the 1% significance level test. This implies a significant positive spatial autocorrelation between the two in geographic space: high-value regions tend to neighbor other high-value regions, while low-value areas also exhibit a clustered distribution, forming a clear spatial agglomeration pattern.

Table 10.

Global autocorrelation test results.

5.2.3. Analysis of Spatial Spillover Effects

As presented in Table 11 and Table 12, under both spatial weight matrices, the direct effect coefficients of digital-real convergence are 0.3328 and 0.3666, respectively. This validates that digital-real convergence stably drives the local low-carbon economy. Using Formula (9), we compute the feedback effect (defined as the gap between the direct effect and the coefficient from the original model): the values are 0.3328 − 0.3264 = 0.0064 and 0.3666 − 0.3511 = 0.0155. From an economic perspective, this means neglecting spatial factors would lead to an underestimation of the effect by about 0.64% and 1.55%, respectively. The root cause of this underestimation is the failure to account for the spillover benefits generated by local digital-real convergence, which are transmitted back to the region via neighboring provinces.

Table 11.

The spillover effect of geographic spatial matrix.

Table 12.

The spillover effect of economic spatial matrix.

Regarding indirect effects, the coefficients of digital-real convergence are 0.5035 (under the economic distance matrix) and 0.5059 (under the geographical adjacency matrix). These figures confirm that digital-real convergence generates notable positive spatial spillover impacts on adjacent regions, driven by mechanisms including factor flow, technology diffusion, and industrial collaboration. Notably, the spillover effect under the economic distance weight is marginally larger than that under the geographical adjacency matrix. This reflects that closer economic ties between regions support better policy alignment, deeper market integration, and more effective cross-regional dissemination of digital technologies and integration models. By contrast, geographical proximity is limited by administrative barriers and industrial similarity, leading to relatively lower transmission efficiency. The total effects were 0.8363 and 0.8725, both significant. In summary, these results show that whether spatial spillovers are considered or not, digital-real convergence exerts a systemic and all-round positive driving influence on the low-carbon economy.

6. Conclusions

This study found that digital-real convergence significantly boosts the low-carbon economy; this conclusion remains valid even after robustness checks and instrumental variable analysis to address endogeneity. Analysis of regional heterogeneity shows that this positive impact is statistically significant in both eastern and western areas, yet it lacks significance (or even takes on a negative direction) within the central region. Additionally, the driving impact of digital-real convergence is notably stronger than that of “digital-digital convergence” or “real-real convergence”. Mechanism tests indicate that digital-real convergence indirectly propels low-carbon development mainly through two channels: promoting the agglomeration of innovative talent and the accumulation of innovative capital. Further analysis identifies a single threshold (0.7351) for urbanization level; once this threshold is crossed, the promoting effect of digital-real convergence strengthens substantially. Spatial econometric results show a marked spatial correlation between digital-real convergence and the low-carbon economy, featuring a distinct positive spatial clustering pattern. Local digital-real convergence not only advances the low-carbon economy within the region itself but also generates positive spillover effects on adjacent areas. Notably, these spillover effects are more prominent in regions with higher economic development levels.

The aforementioned conclusions not only offer policy insights for advancing China’s “dual carbon” goals but also provide the following implications for developing countries and regions worldwide in promoting the Sustainable Development Goals:

First, the synergistic transition of digitalization and green transformation should be tailored to local conditions. Policy formulation should consider each region’s development stage, industrial structure, and digital infrastructure readiness. For more developed areas, the focus can be placed on enhancing the integration of digital tools into conventional energy-heavy sectors. In contrast, less developed regions might give priority to bolstering digital infrastructure, as well as cultivating local capacities for green innovation and building up relevant human capital. This will help coordinate industrial innovation (SDG9) with climate action (SDG13).

Second, institutional design should guide the agglomeration of innovation factors toward green sectors. Policies must go beyond mere technology promotion to actively shape a market environment that incentivizes the flow of talent and capital into green innovation. Examples include refining green financial standards, establishing dedicated risk funds, and implementing incentive programs for technical talent. Such measures can systematically strengthen the intrinsic linkage between clean energy (SDG7) and industrial innovation (SDG9).

Finally, efforts should be made to build cross-regional collaborative governance networks to amplify the benefits of the transition. Given the significant spatial spillover effects of low-carbon transformation, it is essential to foster cooperation beyond administrative boundaries. Through initiatives such as establishing international green technology cooperation zones, transnational digital carbon management platforms, and mechanisms for sharing green patents and ecological compensation, countries and regions can accelerate the diffusion of green technologies, reduce global transition costs, and synergistically advance climate action (SDG13) and global partnerships (SDG17).

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/su18010202/s1, File S1: Formula Supplement.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.Z.; data curation, T.Y.; formal analysis, T.Y.; funding acquisition, H.Z.; investigation, T.Y.; methodology, T.Y.; project administration, T.Y.; resources, T.Y.; software, T.Y.; supervision, H.Z.; validation, H.Z.; visualization, T.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, T.Y. and F.W.; writing—review and editing, T.Y. and F.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Social Science Foundation of China Major Project (24VRC003).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are openly available in National Bureau of Statistics at https://www.stats.gov.cn/.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Liang, X.; Qiu, S.Y. Dilemmas in China’s low-carbon economic development and new opportunities under the “new normal”. Seek Truth 2016, 43, 54–61. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, Z.; Lan, Y.; Zhuo, Q.; Hsu, S.C. Innovating for a greener future: Novelty in green patents and its impact on sustainable development goals in China’s construction sector. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2025, 213, 108025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.C.; Cao, X.; Song, L.H. Research on the pollution reduction and carbon emission reduction effects of the carbon emission trading system—Empirical analysis based on the synthetic control method. J. Nat. Resour. 2024, 39, 712–730. [Google Scholar]

- Xing, B.Y. Practice, problems and countermeasures of low-carbon development in new cities and new areas in China. Macroecon. Manag. 2017, 33, 46–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, L.L. Problems and suggestions in the construction of China’s carbon emission trading market under the “double carbon” goal. Environ. Prot. 2024, 52, 74–75. [Google Scholar]

- Ouyang, R.H. Theoretical logic and analytical framework of data factors promoting the in-depth integration of digital economy and real economy. Econ. Rev. J. 2024, 40, 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klarin, T. The concept of sustainable development: From its beginning to the contemporary issues. Zagreb Int. Rev. Econ. Bus. 2018, 21, 67–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manioudis, M.; Meramveliotakis, G. Broad strokes towards a grand theory in the analysis of sustainable development: A return to the classical political economy. J. Political Econ. 2022, 27, 866–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, J.; Zhuang, G.; Zheng, Y.; Zhu, S.; Xie, Q. Clarification of the concept of a low-carbon economy and the analysis of its core elements. In Political Economy of China’s Climate Policy; Research Series on the Chinese Dream and China’s Development Path; Springer: Singapore, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.J.; Ma, X.F. China entering the era of low-carbon economy—Exploring a low-carbon path with Chinese characteristics. Soc. Sci. Guangdong 2009, 26, 43–49. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, X. Connotation and development trend of low-carbon economy in the new period. J. Shanxi Univ. (Philos. Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2011, 34, 140–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.H.; Li, X.L.; Meng, H.Y. Evaluation of low-carbon economic development in cities of central and southern Hebei Province. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 2014, 24, 24–27. [Google Scholar]

- He, Y.; Guo, Q.Y.; Wu, B. Establishment and comprehensive evaluation of indicators for the development level of low-carbon economy. Stat. Decis. 2014, 30, 47–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.F.; Zheng, L.C.; Cheng, X.L. Evaluation of domestic differences and international gaps in the development level of low-carbon economy. Resour. Sci. 2011, 33, 664–674. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, L.C.; Fu, J.F.; Li, J.S. Evaluation of the development level and spatial process of low-carbon economy in China’s provinces. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 2011, 21, 80–85. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L. The impact of the digital economy on the high-quality development of Xi’an’s manufacturing industry. Appl. Math. Nonlinear Sci. 2024, 9, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subkhan, F.; Maarif, M.S.; Rochman, N.T.; Nugraha, Y. Digital economy: Reinforcing competitive economy of smart cities, a fuzzy-AHP approach. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on ICT for Smart Society (ICISS), Bandung, Indonesia, 4–5 September 2024; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.H.; Liu, Y.Y.; Peng, L.Y. Digital economic development and improvement of green total factor productivity. Shanghai J. Econ. 2021, 41, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.X.; Zhou, J.P.; Liu, C.J. Spatial effect of digital economic development on urban carbon emissions. Geogr. Res. 2022, 41, 111–129. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, X. Digital economy, resource misallocation and total factor productivity. Financ. Trade Res. 2022, 33, 10–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, D.L. Impact of digital economy on urban energy use efficiency in China—Based on the perspective of technological empowerment and technology spillover. Resour. Sci. 2023, 45, 296–307. [Google Scholar]

- Li, F. Inherent logic and path selection of industrial internet promoting industrial low-carbon development under the “double carbon” goal. Guizhou Soc. Sci. 2023, 44, 120–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, W.; Liu, T.; Gan, L. Spatiotemporal heterogeneity of the influence of industrial linkage on building carbon emission. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 100, 111772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Wang, J. The dynamic impact of digital economy on carbon emission reduction: Evidence from city-level empirical data in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 351, 131570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.X.; Xu, H. Can China’s digital economic development bring economic greening?—Empirical evidence from China’s inter-provincial panel data. Inq. Econ. Issues 2021, 42, 15–29. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Y.; Yang, J. Research on the impact of technological change on corporate finance in the digital economy era. Econ. Sci. 2025, 47, 162–184. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L.; Zhang, B.; Xia, Q.Y.; Dong, J. Spatial effect and influence path of land resource misallocation on carbon emission efficiency—Empirical evidence from 108 cities in the Yangtze River Economic Belt. Resour. Sci. 2023, 45, 1059–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhou, X.Y.; Chen, M.Y. From “cultivator” to “influencer”: How digital transformation promotes green innovation development—A longitudinal case study of Inspur. China Soft Sci. 2023, 38, 146–163. [Google Scholar]

- Li, G.; Wang, Y.F.; Yan, T.W. Has digital transformation promoted rural innovation and entrepreneurship?—A quasi-natural experiment based on the “National Digital Village Pilot” policy. Economist 2024, 36, 114–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Qi, Y.D.; Chen, S.J.; Yu, J.T. Digital economy, talent agglomeration and industrial chain modernization. Stat. Decis. 2025, 41, 105–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.J.; Su, J.Q. Construction of open innovation ecosystem for digitally transformed enterprises—Theoretical basis and future prospects. Stud. Sci. Sci. 2023, 41, 335–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, B.; Guo, Q. Impact effect of digital economy on flexible employment: Based on the dual perspectives of quantity and quality. China Soft Sci. 2024, 39, 150–160. [Google Scholar]

- Rui, X.Q.; Niu, C.H.; Chen, X.G.; Fan, Y.P. Measurement and generation mechanism of the agglomeration effect of scientific and technological talents in innovation networks. Sci. Technol. Prog. Policy 2011, 28, 146–151. [Google Scholar]

- Bao, P.C.; Yin, C.J.; Yang, K. Can innovative talent agglomeration improve urban carbon emission performance?—Empirical evidence from Chinese prefecture-level cities. Res. Econ. Manag. 2025, 46, 24–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Xu, M.; Ma, S.J. Corrigendum to “The effect of the spatial heterogeneity of human capital structure on regional green total factor productivity” [Structural Change and Economic Dynamics 59 (2021) 427–441]. Struct. Change Econ. Dyn. 2022, 61, 463–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, D.Y.; Chen, L. Research on the impact of digital technology application on enterprises’ total factor productivity—Also on solving the new “Solow Paradox”. Sci. Res. Manag. 2024, 45, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, W.L.; Peng, Y.Y. Platform economic financialization and financial risk governance research. Contemp. Econ. Res. 2023, 34, 37–48. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, J.J.; Yuan, Y.J. Collaborative innovation, local official turnover and technological upgrading. Stud. Sci. Sci. 2018, 36, 1143–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, C.; Li, C.Y. Development trend and policy orientation analysis of low-carbonization of China’s manufacturing industry. Qilu J. 2024, 51, 137–149. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y. The process, problems and trends of urbanization development in China. Res. Econ. Manag. 2011, 32, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.C. Giving play to the radiation-driven role of innovation agglomeration areas in central cities. Urban Manag. Sci. Technol. 2021, 22, 51–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Q.; Su, Q.X. Research on the mechanism of cross-border e-commerce platforms empowering the internationalization of small and medium-sized enterprises. Intertrade 2022, 41, 68–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.J.; Liang, Y.X.; Gong, R.R. Research on the dynamic impact of digital economy on the urban-rural income gap—Evidence from 31 provinces (autonomous regions and municipalities directly under the Central Government) in China. Inquiry Econ. Issues 2023, 44, 18–40. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y.H.; Xu, Q.X.; Yan, H.; Zheng, H. Digital empowerment for the open, inclusive and high-quality development of future education. Open Educ. Res. 2023, 29, 104–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Ma, Y.R.; Xu, S.X. Has the development of digital economy improved China’s green economic efficiency? China Popul. Resour. Environ. 2022, 32, 72–85. [Google Scholar]

- Chao, X.J.; Shen, L. Spatial spillover effect of new digital infrastructure on urban ecological efficiency in the Yellow River Basin—Analysis based on data of 97 cities along the line from 2013 to 2020. J. Shaanxi Norm. Univ. (Philos. Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2023, 52, 46–60. [Google Scholar]

- Dou, S.Q.; Wang, Q. Digital industry collaborative innovation, new quality productivity and common prosperity. Stat. Decis. 2025, 41, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Z.L.; Zhang, L.; Hou, J.T.; Liu, H.Y. The mediating effect test procedure and its application. Acta Psychol. Sin. 2004, 49, 614–620. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, M.; Wang, L.; Guo, J.H. Measurement and spatial-temporal comparison of the integration of digital and real economies under the background of new quality productivity—A study based on the patent co-classification method. J. Quant. Tech. Econ. 2024, 41, 5–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, N.P.; Zhou, Y.Y.; Si, J.L.; Chen, S.Y. Analysis of the agglomeration level and development focus of regional innovation factors in China. East China Econ. Manag. 2016, 30, 80–87. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, B.E. Threshold effects in non-dynamic panels: Estimation, testing, and inference. J. Econom. 1999, 93, 345–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.