Effect of Flax Fiber Content on the Properties of Bio-Based Filaments for Sustainable 3D Printing of Automotive Components

Abstract

1. Introduction

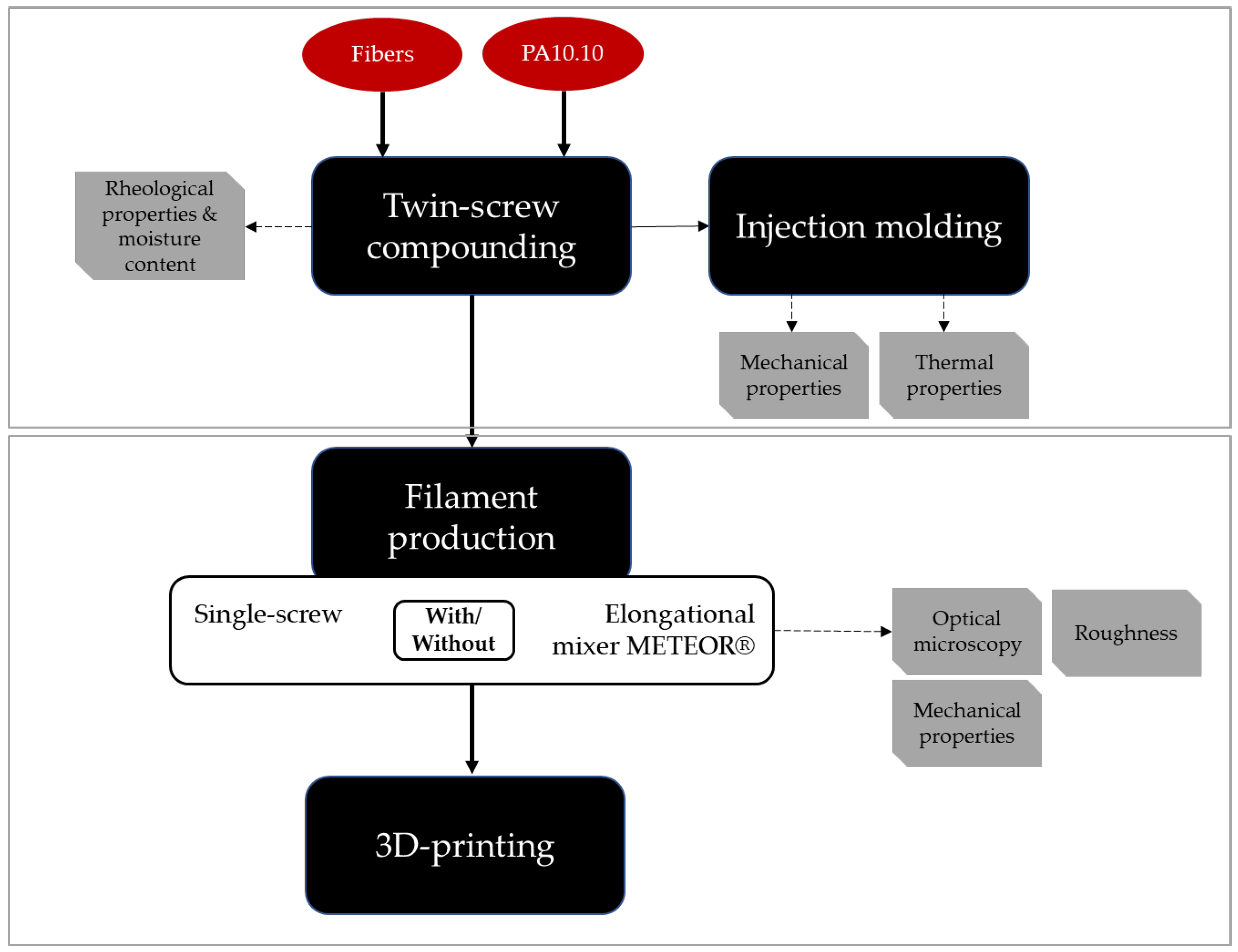

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Blend Preparation Methods

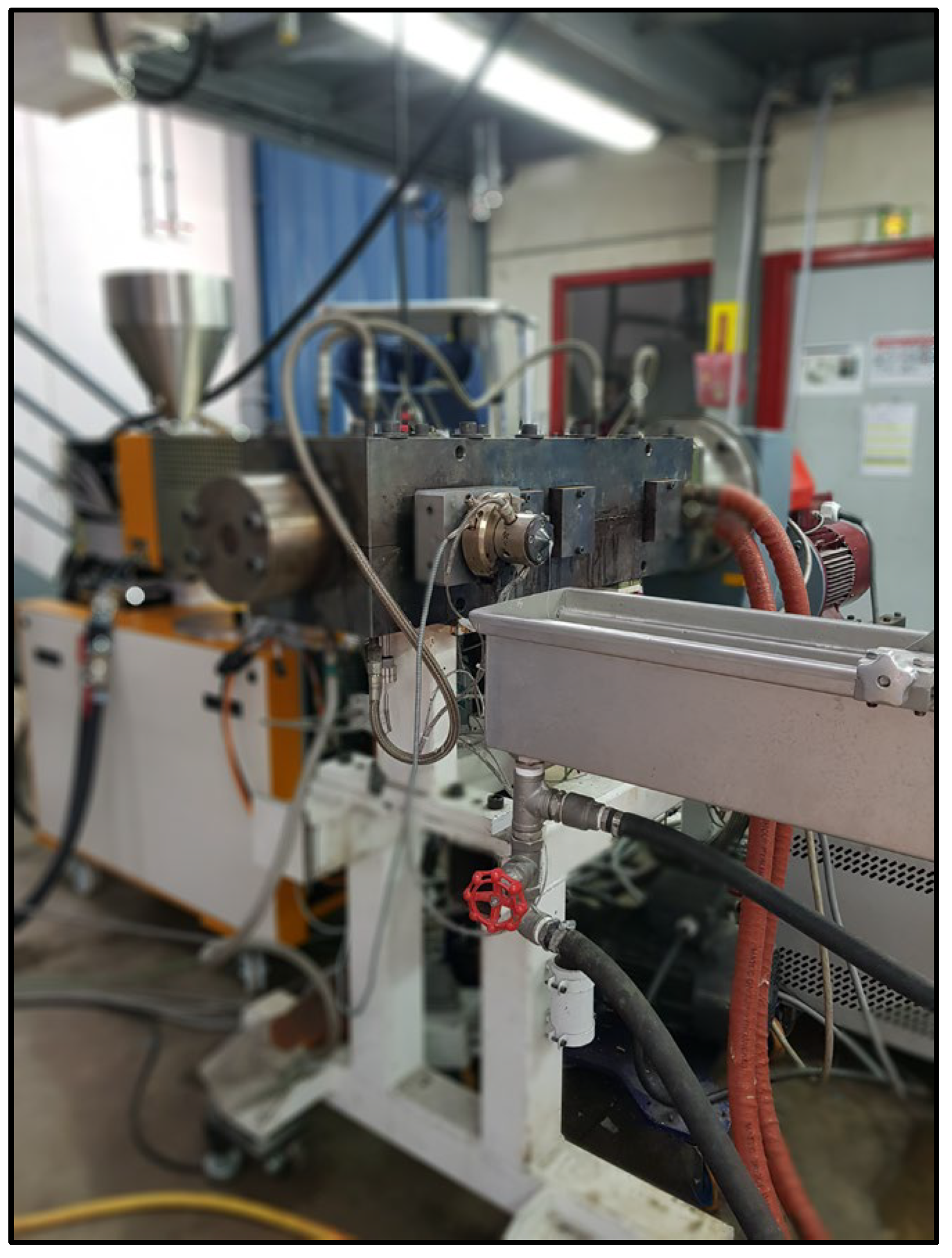

2.2.1. Twin-Screw Extrusion and Compounding

2.2.2. Injection of Tensile Specimens

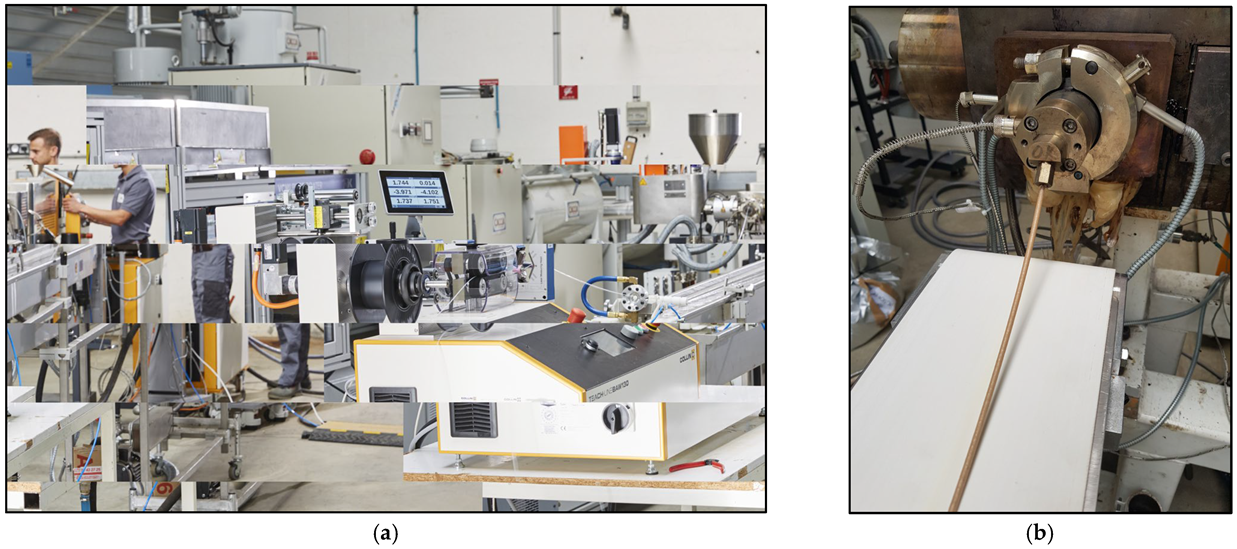

2.2.3. Filament Extrusion

- FDM Line

- Adding the continuous elongational flow mixer METEOR® to the FDM Line

2.2.4. Three-Dimensional Printing Line

2.3. Experimental Methods and Procedures

2.3.1. Rheological Properties

- Temperature: 210 °C.

- Imposed oscillation frequency: 1 Hz.

- Imposed strain (determined from LVE): 0.05%.

- Test durations: 900 s (15 min) and 2700 s (45 min).

2.3.2. Moisture Content Measurement

2.3.3. Thermal Analysis: DSC and TGA

2.3.4. Mechanical Properties

- Injected samples

- Filament samples

2.3.5. Optical Microscopy

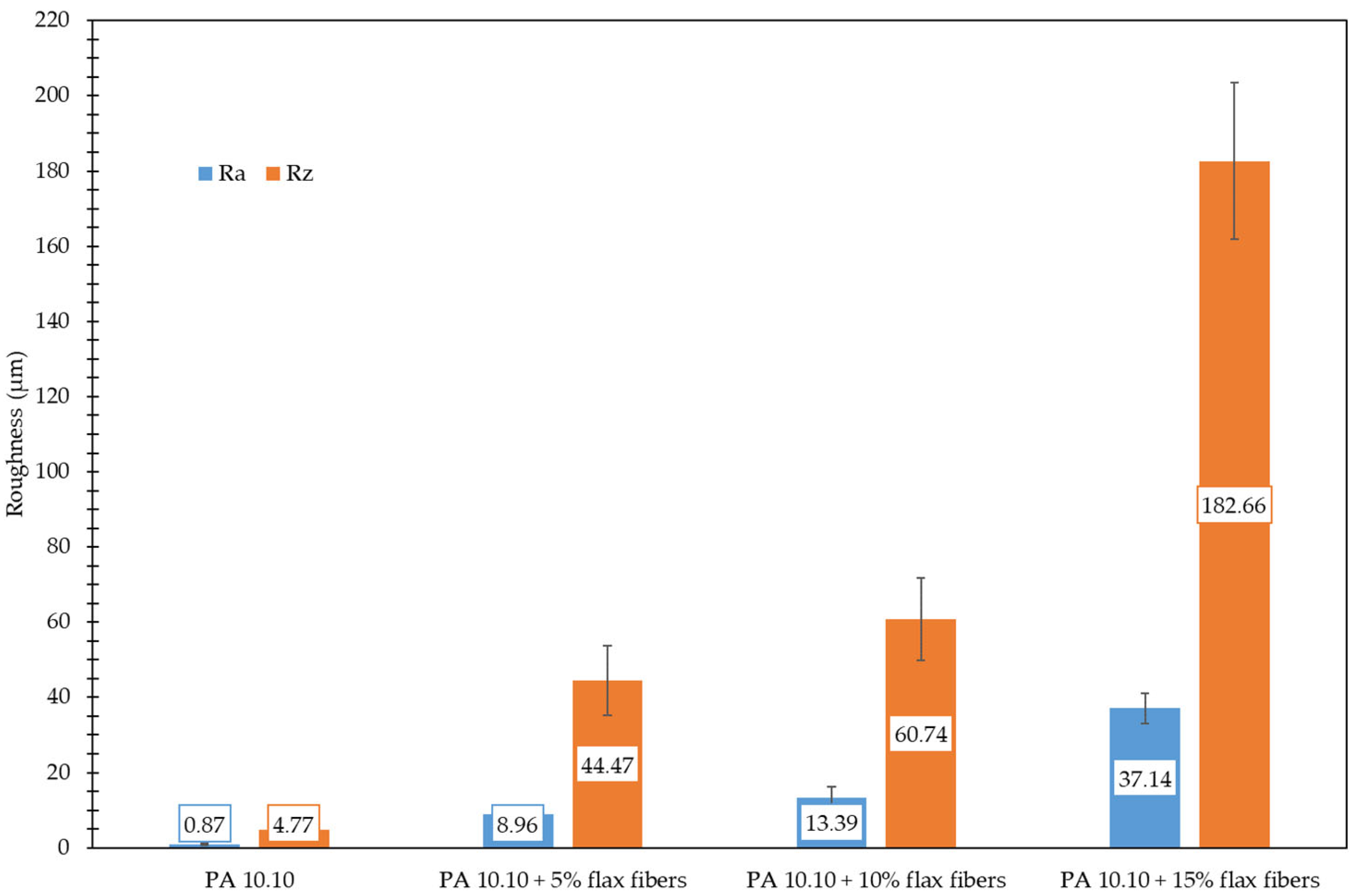

2.3.6. Roughness

3. Results

3.1. Influence of the Fiber Nature on the Properties of Injected PA10.10/Flax Biocomposites Samples

3.2. Three-Dimensional Filament Processing

3.3. Material Properties

3.4. Physical Properties: Optical Microscopy and Surface Roughness

3.5. Rheological Analysis—Plate–Plate Rheometry

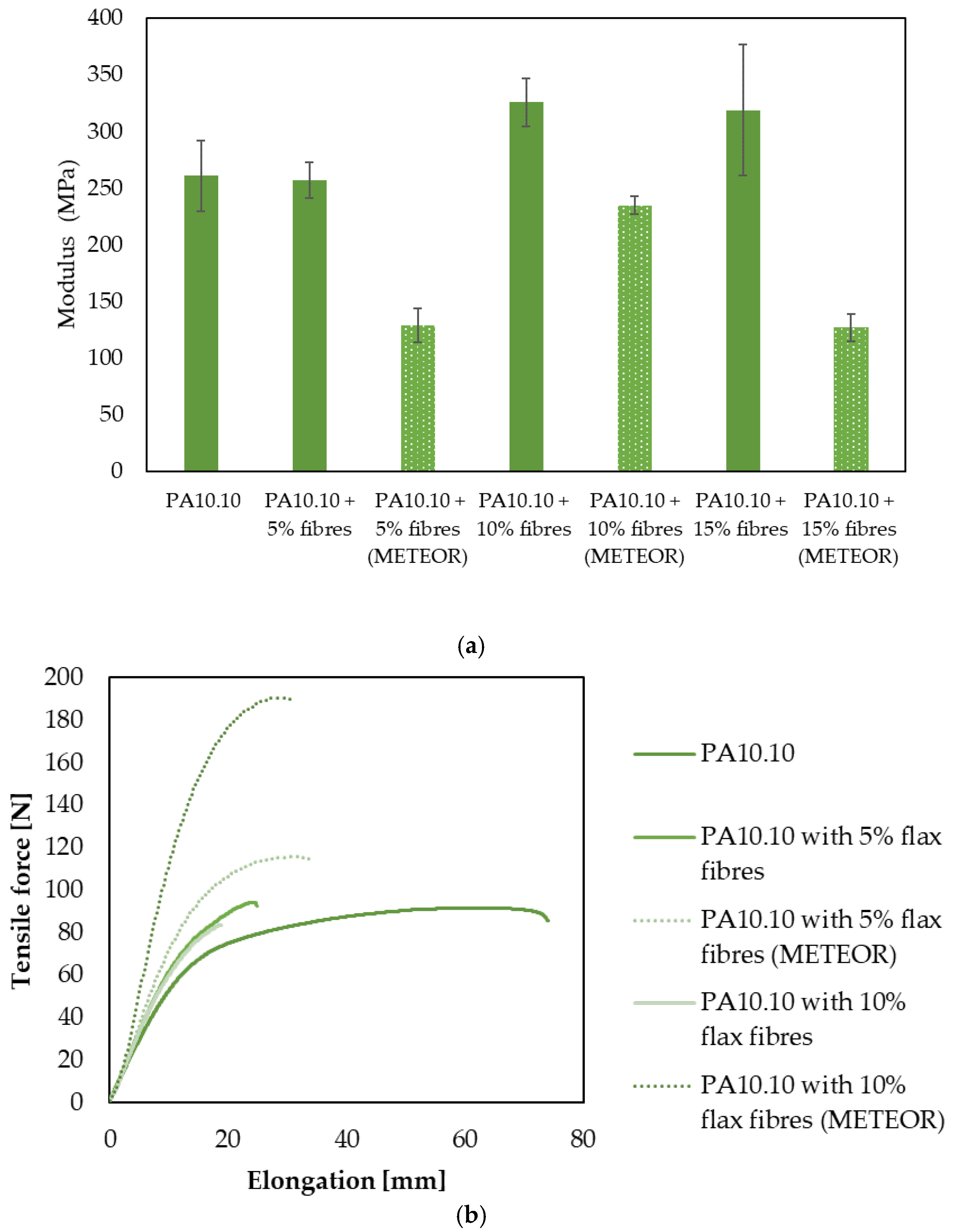

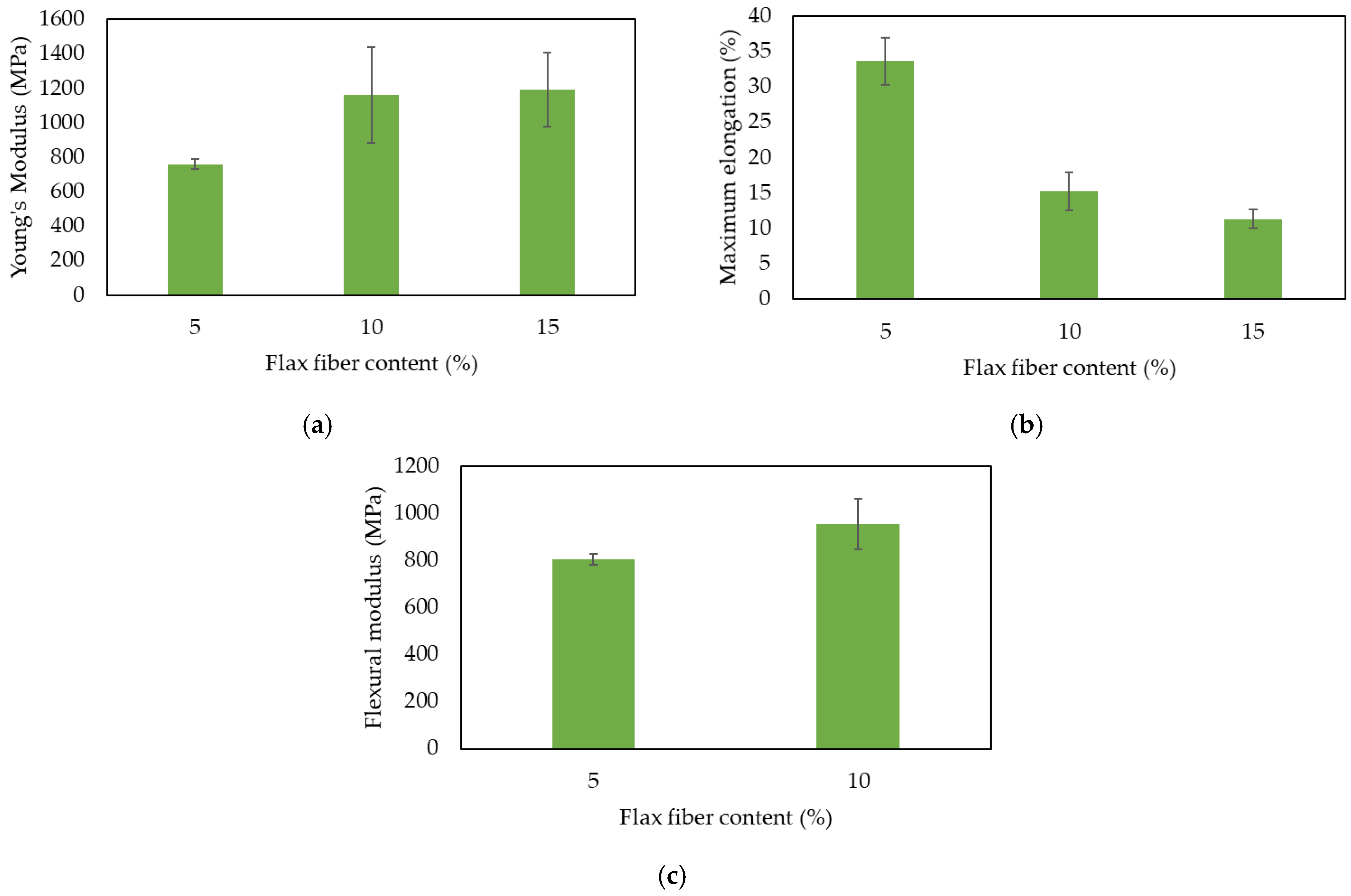

3.6. Mechanical Properties of PA/Flax Fibers Blends

3.7. Three-Dimensional Printing and Demonstrator Development

4. Discussion

4.1. Effect of Fiber Loading on Microstructure and Mechanical Behavior

4.2. Role of Processing Route: METEOR Elongational Mixing

4.3. Rheological Behavior and Implications for Printability

4.4. Optimal Fiber Loading for Functional FDM Components

4.5. Perspectives for Recyclability and Sustainability of PA10.10/Flax Biocomposites

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PA | Polyamide |

| METEOR | Elongational mixer |

| 3D | Three dimensions |

| FDM | fused deposition modeling |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Roughness

| Standard | With METEOR | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample | PA 10.10 | PA 10.10 + 5% flax fiber | PA 10.10 + 10% flax fiber | PA 10.10 + 15% flax fiber | PA 10.10 + 5% flax fiber | PA 10.10 + 10% flax fiber | PA 10.10 + 15% flax fiber |

| Ra (µm) | 0.87 ± 0.33 | 8.96 ± 1.49 | 13.39 ± 2.84 | 37.14 ± 4.02 | 7.16 ± 2 | 8.17 ± 0.79 | 9.67 ±1.83 |

| Rz (µm) | 4.77 ± 1.37 | 44.47 ± 9.35 | 60.74 ± 11.01 | 182.66 ± 20.9 | 36.61 ± 7.79 | 40.96 ± 2.54 | 51.48 ± 9.91 |

Appendix A.2. Mechanical Testing on 3D Printed Specimens

| 3D Printed Sample | Young’s Modulus (MPa) | Maximum Force (MPa) | Elongation at Maximum Force (%) | Force at Maximum Elongation (MPa) | Maximum Elongation (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PA 10.10 + 5% flax fiber | 760 ± 30 | 27 ± 0.4 | 29.0 ± 2.34 | 25.5 ± 0.5 | 33.58 ± 3.32 |

| PA 10.10 + 10% flax fiber | 1160 ± 279 | 24.9 ± 1.1 | 13.73 ± 1.78 | 23.9 ± 1.2 | 15.24 ± 2.7 |

| PA 10.10 + 15% flax fiber | 1192 ± 215 | 20.8 ± 0.6 | 10.54 ± 0.76 | 20 ± 0.9 | 11.3 ± 1.3 |

| 3D Printed Sample | Flexural Modulus (Mpa) | Maximum Force (Mpa) | Elongation at Maximum Force (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| PA 10.10 + 5% flax fiber | 803 ± 24 | 43.0 ± 1.3 | 8.25 ± 0.24 |

| PA 10.10 + 10% flax fiber | 954 ± 107 | 43.2 ± 3.3 | 7.58 ± 0.09 |

References

- Haque, A.N.M.A.; Naebe, M. Tensile Properties of Natural Fibre-Reinforced FDM Filaments: A Short Review. Sustainability 2023, 15, 16580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamadi, A.H.; Razali, N.; Petrů, M.; Taha, M.M.; Muhammad, N.; Ilyas, R.A. Effect of Chemically Treated Kenaf Fibre on Mechanical and Thermal Properties of PLA Composites Prepared through Fused Deposition Modeling (FDM). Polymers 2021, 13, 3299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coppola, B.; Garofalo, E.; Di Maio, L.; Scarfato, P.; Incarnato, L. Investigation on the Use of PLA/Hemp Composites for the Fused Deposition Modelling (FDM) 3D Printing; AIP Publishing LLC: Melville, NY, USA, 2018; p. 020086. [Google Scholar]

- Soccalingame, L.; Perrin, D.; Bénézet, J.-C.; Mani, S.; Coiffier, F.; Richaud, E.; Bergeret, A. Reprocessing of Artificial UV-Weathered Wood Flour Reinforced Polypropylene Composites. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2015, 120, 313–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzanti, V.; Malagutti, L.; Mollica, F. FDM 3D Printing of Polymers Containing Natural Fillers: A Review of Their Mechanical Properties. Polymers 2019, 11, 1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, M.N.; Ishak, M.R.; Mohammad Taha, M.; Mustapha, F.; Leman, Z. A Review of Natural Fiber-Based Filaments for 3D Printing: Filament Fabrication and Characterization. Materials 2023, 16, 4052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Duigou, A.; Correa, D.; Ueda, M.; Matsuzaki, R.; Castro, M. A Review of 3D and 4D Printing of Natural Fibre Biocomposites. Mater. Des. 2020, 194, 108911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhagia, S.; Bornani, K.; Agrawal, R.; Satlewal, A.; Ďurkovič, J.; Lagaňa, R.; Bhagia, M.; Yoo, C.G.; Zhao, X.; Kunc, V.; et al. Critical Review of FDM 3D Printing of PLA Biocomposites Filled with Biomass Resources, Characterization, Biodegradability, Upcycling and Opportunities for Biorefineries. Appl. Mater. Today 2021, 24, 101078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, X. Development of Thermoplastic 3D Printing Feedstock Utilising Biomass. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Southern Queensland, Toowoomba, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Giammaria, V.; Capretti, M.; Del Bianco, G.; Boria, S.; Santulli, C. Application of Poly(Lactic Acid) Composites in the Automotive Sector: A Critical Review. Polymers 2024, 16, 3059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andanje, M.N.; Mwangi, J.W.; Mose, B.R.; Carrara, S. Biocompatible and Biodegradable 3D Printing from Bioplastics: A Review. Polymers 2023, 15, 2355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syrlybayev, D.; Zharylkassyn, B.; Seisekulova, A.; Akhmetov, M.; Perveen, A.; Talamona, D. Optimisation of Strength Properties of FDM Printed Parts—A Critical Review. Polymers 2021, 13, 1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Megersa, G.K.; Sitek, W.; Nowak, A.J.; Tomašić, N. Investigation of the Influence of Fused Deposition Modeling 3D Printing Process Parameters on Tensile Properties of Polylactic Acid Parts Using the Taguchi Method. Materials 2024, 17, 5951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daly, M.; Tarfaoui, M.; Chihi, M.; Bouraoui, C. FDM Technology and the Effect of Printing Parameters on the Tensile Strength of ABS Parts. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2023, 126, 5307–5323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sultana, J.; Rahman, M.M.; Wang, Y.; Ahmed, A.; Xiaohu, C. Influences of 3D Printing Parameters on the Mechanical Properties of Wood PLA Filament: An Experimental Analysis by Taguchi Method. Prog. Addit. Manuf. 2024, 9, 1239–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soni, A.; Gupta, S.K.; Veeman, D.; Katiyar, J.K. 3D-Printed Sustainable Biocomposites via Valorization of Biomass: Focus on Challenges and Their Future Perspectives. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2025, 1–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourry, D.; Khayat, R.E.; Utracki, L.A.; Godbille, F.; Picot, J.; Luciani, A. Extensional Flow of Polymeric Dispersions. Polym. Eng. Sci. 1999, 39, 1072–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rondin, J.; Bouquey, M.; Muller, R.; Serra, C.A.; Martin, G.; Sonntag, P. Dispersive Mixing Efficiency of an Elongational Flow Mixer on PP/EPDM Blends: Morphological Analysis and Correlation with Viscoelastic Properties. Polym. Eng. Sci. 2014, 54, 1444–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, Y. Development of a Novel Microcompounder for Polymer Blends and Nanocomposite. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2009, 112, 609–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldmann, M.; Bledzki, A.K. Bio-Based Polyamides Reinforced with Cellulosic Fibres—Processing and Properties. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2014, 100, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver-Ortega, H.; Julian, F.; Espinach, F.X.; Tarrés, Q.; Delgado-Aguilar, M.; Mutjé, P. 6-Biobased Polyamide Reinforced with Natural Fiber Composites. In Fiber Reinforced Composites; Joseph, K., Oksman, K., George, G., Wilson, R., Appukuttan, S., Eds.; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2021; pp. 141–165. ISBN 978-0-12-821090-1. [Google Scholar]

- Gauss, C.; Pickering, K.; Tshuma, J.; McDonald-Wharry, J. Production and Assessment of Poly(Lactic Acid) Matrix Composites Reinforced with Regenerated Cellulose Fibres for Fused Deposition Modelling. Polymers 2022, 14, 3991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deb, D.; Jafferson, J.M. Natural Fibers Reinforced FDM 3D Printing Filaments. Mater. Today Proc. 2021, 46, 1308–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mani, S.; Pivard, L.; Duthel, H. A New Continuous Extensional Flow Mixer for Compounding and Recycling of Polymer Blends. Patent 1656930 (B1), 26 January 2018. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 527-1; Plastics—Determination of Tensile Properties—Part 1: General Principles. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019.

- Pickering, K.L.; Efendy, M.G.A.; Le, T.M. A Review of Recent Developments in Natural Fibre Composites and Their Mechanical Performance. Compos. Part Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2016, 83, 98–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazan, P.; Nosal, P.; Wierzbicka-Miernik, A.; Kuciel, S. A Novel Hybrid Composites Based on Biopolyamide 10.10 with Basalt/Aramid Fibers: Mechanical and Thermal Investigation. Compos. Part B Eng. 2021, 223, 109125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, R.; Ray, S.S. Role of Rheology in Morphology Development and Advanced Processing of Thermoplastic Polymer Materials: A Review. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 27969–28001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muthuraj, R.; Hajee, M.; Horrocks, A.R.; Kandola, B.K. Biopolymer Blends from Hardwood Lignin and Bio-Polyamides: Compatibility and Miscibility. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 132, 439–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Depuydt, D.; Balthazar, M.; Hendrickx, K.; Six, W.; Ferraris, E.; Desplentere, F.; Ivens, J.; Van Vuure, A.W. Production and Characterization of Bamboo and Flax Fiber Reinforced Polylactic Acid Filaments for Fused Deposition Modeling (FDM). Polym. Compos. 2019, 40, 1951–1963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muukka, S. Bio-Oil Based Polymeric Composites for Additive Manufacturing. Master’s Thesis, Aalto University, Espoo, Finland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Gallos, A.; Paës, G.; Allais, F.; Beaugrand, J. Lignocellulosic Fibers: A Critical Review of the Extrusion Process for Enhancement of the Properties of Natural Fiber Composites. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 34638–34654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, T.N.; Bayer, I.S.; Heredia-Guerrero, J.A.; Frugone, M.; Lagomarsino, M.; Maggio, F.; Athanassiou, A. Cocoa Shell Waste Biofilaments for 3D Printing Applications. Macromol. Mater. Eng. 2017, 302, 1700219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filgueira, D.; Holmen, S.; Melbø, J.K.; Moldes, D.; Echtermeyer, A.T.; Chinga-Carrasco, G. 3D Printable Filaments Made of Biobased Polyethylene Biocomposites. Polymers 2018, 10, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirsch, P.; Theumer, T. Comparative Study on Polyamide 11 and Polyamide 10.10 as Matrix Polymers for Biogenic Wood-Plastic Composites. Macromol. Symp. 2022, 403, 2100492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, S.M.; Wilson, L.A.; Rb, J.R. Natural Fiber Filaments Transforming the Future of Sustainable 3D Printing. MethodsX 2025, 14, 103385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milosevic, M.; Stoof, D.; Pickering, K.L. Characterizing the Mechanical Properties of Fused Deposition Modelling Natural Fiber Recycled Polypropylene Composites. J. Compos. Sci. 2017, 1, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manker, L.P.; Hedou, M.A.; Broggi, C.; Jones, M.J.; Kortsen, K.; Puvanenthiran, K.; Kupper, Y.; Frauenrath, H.; Marechal, F.; Michaud, V.; et al. Performance Polyamides Built on a Sustainable Carbohydrate Core. Nat. Sustain. 2024, 7, 640–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample | Tensile Properties | Thermal Properties | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tensile Modulus (MPa) | Stress at Break (MPa) | Strain at Break (%) | ΔHm (J.g−1) | Percentage of Crystallinity (%) | Vicat (°C) | HDT (°C) | |

| Raw PA 10.10 | 1580 ± 63 | Not measured (too flexible) | 53.0 | 21.7 | 194 ± 0.0 | 112 ± 3.3 | |

| PA10.10 + 5% flax fibers | 2000 ± 127 | 47.7 ± 0.5 | 22.7 ± 1.9 | 51.1 | 221 | 196 ± 0.1 | 135 ± 0.4 |

| PA10.10 + 10% flax fibers | 2600 ± 84 | 51.0 ± 1.1 | 10.6 ± 0.3 | 52.6 | 23.9 | 197 ± 0.1 | 149 ± 0.6 |

| PA10.10 + 15% flax fibers | 2900 ± 68 | 51.0 ± 1.4 | 9.0 ± 0.4 | 52.7 | 25.4 | n.d. | n.d. |

| PA10.10 + 20% flax fibers | 3416 ± 70 | 51.1 ± 0.3 | 8.2 ± 0.2 | 51.2 | 26.2 | 196 ± 0.5 | 172 ± 2.4 |

| PA10.10 + 30% flax fibers | 4348 ± 259 | 55.6 ± 1.6 | 4.4 ± 0.3 | 57.9 | 33.9 | 196 ± 0.9 | 179 ± 0.4 |

| Flax Fibers Loading | 5% | 10% | 15% | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Extrusion Process | Standard | With METEOR | Standard | With METEOR | Standard | With METEOR |

| Extruder screw speed (rpm) | 11 | 16 | 11 | 25 | 13 | 13 |

| Mater temperature (°C) | 213 | 190 | 213 | 191 | 217 | 217 |

| METEOR parameters | n.a. | 5 rpm/215 °C | n.a. | 5 rpm/215 °C | n.a. | 5 rpm/220 °C |

| Die temperature (°C) | 210 | 215 | 210 | 215 | 220 | 205 |

| IV (cm3/g) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Flax Fibers Loading | Standard | With METEOR |

| 0% | 170.7 | na |

| 5% | 168.0 | 160.7 |

| 10% | 163.8 | 165.6 |

| 15% | 152.8 | 130.0 |

| Without METEOR | With METEOR | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flax Fibers Loading | Approximate Porosity (%) | Mean Length (µm) | Approximate Porosity (%) | Mean Length (µm) |

| 5% | / | 50.4 ± 58.0 | 37.1 | 88.8 ± 42.1 |

| 10% | 27.4 | 41.8 ± 26.7 | 32.7 | 54.0 ± 47.3 |

| 15% | 7.2 | 54.9 ± 30.9 | 52.0 | 58.7 ± 32.2 |

| Nozzle Diameter | 0.6 mm |

| Nozzle Temperature | 240 °C |

| Layer Height | 0.2 mm |

| Speed | 20 mm/s |

| Flow Rate | 100% |

| Infill Density | 100% |

| Bed Temperature | 75 °C |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Isnard, F.; Poloni, M.; Redrado, M.; Navarro-Miguel, R.; Mani, S. Effect of Flax Fiber Content on the Properties of Bio-Based Filaments for Sustainable 3D Printing of Automotive Components. Sustainability 2026, 18, 199. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010199

Isnard F, Poloni M, Redrado M, Navarro-Miguel R, Mani S. Effect of Flax Fiber Content on the Properties of Bio-Based Filaments for Sustainable 3D Printing of Automotive Components. Sustainability. 2026; 18(1):199. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010199

Chicago/Turabian StyleIsnard, Florence, Mélissa Poloni, Marta Redrado, Raquel Navarro-Miguel, and Skander Mani. 2026. "Effect of Flax Fiber Content on the Properties of Bio-Based Filaments for Sustainable 3D Printing of Automotive Components" Sustainability 18, no. 1: 199. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010199

APA StyleIsnard, F., Poloni, M., Redrado, M., Navarro-Miguel, R., & Mani, S. (2026). Effect of Flax Fiber Content on the Properties of Bio-Based Filaments for Sustainable 3D Printing of Automotive Components. Sustainability, 18(1), 199. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010199