Abstract

The aim of this study was to develop a model that classifies companies into high or low categories based on their return on equity (RoE), the most important indicator of financial performance, using sustainability and governance-related committee reports and reports shared with the public. As a sample, the RoE, sustainability, and governance variables of all 427 companies traded on the Istanbul Stock Exchange in 2024 were used. Using a 70:30 stratified split between the training and test sets, three tree-based models (XGBoost, LightGBM, and Random Forest) were used to perform a binary classification task. The findings show that tree-based models perform only slightly better than the naive majority class rule, and therefore, have limited overall classification power. A noteworthy finding from the study is that SHAP-based explainability analysis shows that the Corporate Governance Report (IMNG), the Integrated Report (IREP) and the existence of a Sustainability Committee (ICOM) rank higher in terms of SHAP-based global importance in the High RoE classification model, although their average contributions are small and, in the case of IMNG, predominantly negative for the probability of belonging to the High RoE class. Methodologically, the article moves away from traditional econometric methods based on ESG scores, instead combining a predictive classification structure with TreeSHAP-based explanations. These findings indicate a need for reporting practices that offer deeper content, clearer evidence of governance quality, and stronger data integrity to better support investors’ decision-making processes through sustainability and governance.

1. Introduction

Sustainability reporting is now considered as important as financial statements for decision makers considering investing in global markets. In Turkey, sustainability or integrated reporting is not mandatory for companies listed on the Istanbul Stock Exchange (BIST). Furthermore, this voluntary approach provides an excellent analytical environment for measuring the impact of sustainability indicators across different topics compared with capital markets that mandate the publication of these indicators. Companies present these reports not only to meet potential legal requirements but also because they complement and support their financial information. The interaction between RoE, one of the key indicators of financial performance that investors refer to when assessing the effective use of capital, and sustainability factors in markets has not been clearly established in the literature.

A review of the literature shows that the impact of sustainability reporting on financial performance has mostly been examined using traditional econometric methods and, more specifically, regression-based models. The main focus of these studies is to predict the level of ESG scores. The lack of objectivity and comparability of ESG scores and corporate governance indicators in emerging markets is a significant problem. It also complicates interpretation of the findings.

On the other hand, testing financial performance solely with traditional econometric models is no longer sufficient. This approach, which reflects the market’s actual products onto the decision-making mechanisms of decision makers, is now inadequate compared with artificial intelligence tools (machine learning algorithms). Furthermore, capital market investors attempt to predict a company’s performance when making decisions. Therefore, they require simple, understandable, and effective indicators to distinguish between high and low performance. This situation brings machine learning models to the fore. These models offer a more distinct prediction-focused framework for classification compared with traditional econometric models. The literature review conducted for this study also points to this gap in the literature. The literature review conducted for this study did not find any research examining the possible effects of governance and sustainability regimes on RoE performance.

This study aims to develop machine learning models that classify the return on equity of 427 companies listed on the BIST as high or low, using sustainability and governance committee and reporting variables as independent variables. The main purpose of using the independent variables in the study’s model is that these reports, audited by internal audit mechanisms and shared with the public, demonstrate companies’ transparency and reporting behavior, and the information they contain is publicly available to all investors in real time. The original aspect of this research is that, rather than measuring the degree of impact of ESG scores, it tests the discriminative power of the relevant independent variables’ binary indicators in classifying companies as low or high based on their RoE. Thus, the aim is to create a predictive mechanism for the power of past governance and reporting indicators to classify companies as low/high based on their RoE in the future.

Although the study relies on simple present/absent (binary) disclosures, these signals are theoretically grounded in both signaling theory and the resource-based view. In emerging markets where information asymmetry is high, binary governance and sustainability indicators function as threshold signals that reveal whether a minimum level of organizational capacity and internal control infrastructure exists. Therefore, even if these signals are coarse, they may still contain limited but non-negligible predictive value for distinguishing firms with stronger future RoE performance. This theoretical link clarifies why binary disclosures are evaluated as potential classification inputs in the present study.

Ultimately, this study does not merely measure the impact of sustainability committees and sustainability reporting on RoE (financial performance) at the level of correlation; it also assesses the extent to which these internal control mechanisms and corporate disclosures provide a distinctive signal for investors/potential investors through classification success. In this respect, the study proposes a new methodological approach for analyzing sustainability committees and reporting, particularly in emerging markets.

This study makes three key contributions to the literature regarding the relationship between financial performance and sustainability reporting. First, it presents an innovative machine learning classification framework based on investors systematically identifying companies with high RoE in the stock market using binary (yes/no) management and reporting signals, rather than traditional econometric analyses using ESG scores. Second, it employs a TreeSHAP-based Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI) approach to explain model decisions, ensuring the interpretability and transparency of results. Third, the finding of low prediction performance empirically demonstrates the inadequacy of quality at the asset level alone in reporting practices and provides important evidence that sheds light on future regulations.

2. Literature Review and Conceptual Framework

2.1. Background on the Development of Sustainability Reporting and Regulations

Sustainability reporting is a corporate reporting process that presents the economic, environmental, social, and corporate governance performance of businesses as a whole. Two main arguments underpin the widespread adoption of this process in the markets. These are legal regulations and the demand for transparency. In particular, the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) [1], the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB [2]), and the added IFRS S1 and S2 standards have been an important step toward regulating sustainability, especially in the context of these two arguments, in companies’ financial reports [3,4].

In Turkey, sustainability reporting has been accepted as an institutional process with the “Sustainability Principles Compliance Framework” that came into force in 2020, both to reduce information asymmetry in the markets on the Istanbul Stock Exchange and to increase investor confidence in businesses. Following this regulation, disclosures related to ESG indicators through integrated reporting practices have become information sets that inform financial decisions, even though they are optional for companies.

2.2. Theoretical Approaches to the Impact of Sustainability Disclosures on Financial Performance

Four fundamental theoretical approaches are used in the literature to explain the impact of sustainability reporting on company performance. The first of these is stakeholder theory, which emphasizes that businesses have responsibilities not only to shareholders but also to all stakeholders, including employees, customers, suppliers, society, and the environment [5]. Stakeholder Theory argues that sustainability disclosures support company value in the long term. In short, according to this theory, meeting stakeholder expectations reduces risk perception, and companies with low risk perception can see long-term improvements in financial performance indicators such as return on equity.

The second theory positioned as a strategic tool used by businesses to align with social norms and expectations from a sustainability reporting perspective is legitimacy theory [6]. Sustainability reports created within the framework of this theory reinforce the social acceptance of the business. This can mitigate the company’s potential sanctions risks and threats to its reputation. Thus, the disclosures covered by the reporting serve as a protective “insurance function” that increases the firm’s resilience to external pressures, indirectly contributing to the company’s financial performance.

Third, signal theory is also a fundamental theory in the perspective of sustainability reporting. This theory addresses companies’ sustainability disclosures within a voluntary disclosure approach and argues that such disclosures send positive signals to the market in favor of the company [7]. In particular, due to high information asymmetry in emerging markets, elements such as having sustainability committees or publishing reports containing sustainability information are interpreted as signals indicating “corporate capacity” for investors, according to this theory. This theory argues that these signals shape expectations regarding the company’s future financial success. Consequently, the predictive power of the relationship between these signal elements and financial performance indicators such as RoE has become an increasingly important research topic in the literature today.

The fourth and final fundamental theory, the resource-based view, is a theory that sees sustainability-focused practices as rare and difficult-to-imitate strategic resources that provide a competitive advantage to the organization [8]. According to this theory, expenditures made for corporate sustainability are evaluated not only as a cost to be borne but also as investments that nurture value-creating elements such as human capital, innovation capacity, and corporate reputation. The firm’s long-term competitive strength and financial performance are supported by these strategic assets. Therefore, this theory provides an important framework for explaining the potential effects of sustainability reporting on financial performance in the long term.

2.3. Dominant Approach in the Literature: Testing the Relationship Between ESG Scores and Financial Performance Using Traditional Econometric Methods

Most studies examining the relationship between sustainability reporting and financial performance utilize regression-based econometric models and use ESG scores published by rating agencies as their primary data. These studies are actually based on a rather fundamental assumption. It is assumed that improvements in ESG performance increase investor confidence and reduce capital costs, thereby also improving financial performance [9]. Within this framework, variables such as return on equity (RoE), return on assets (RoA), Tobin’s Q, or market value are generally selected as dependent variables in the models. ESG scores are analyzed using econometric methods as explanatory factors that may have a positive, negative, or neutral effect on financial performance [10,11].

A significant portion of the studies in the literature show that ESG performance contributes to firm value, particularly in developed markets. Eccles et al. (2014) argue that companies adopting sustainability-focused strategies demonstrate higher financial performance than their competitors in the long term [12]. They emphasize that this superiority emerges particularly through the corporate governance component. Derwall and Verwijmeren (2007) identified significant increases in market returns for companies with high environmental impact [13]. In short, these findings reveal a general “positive trend” indicating that ESG practices support firm value.

However, there are also studies in the literature that find results differing from this optimism. These empirical studies report that ESG scores have no statistically significant effect on financial performance [14,15]. Some studies show that the relationship between ESG and financial performance can change direction depending on factors such as sector, market maturity level, and corporate structure. Aras and Crowther (2009), in their study focusing on emerging markets, emphasize that most corporate sustainability practices are limited to symbolic statements aimed at meeting legal requirements [16]. Therefore, the short-term impact on financial performance in these markets remains limited. A study by Kılıç and Kuzey (2019) on a Turkish sample also found that the relationship between ESG scores and RoE in BIST companies is statistically insignificant and weak [17]. The study indicated that this situation stems primarily from a lack of standardization in disclosure content.

In general, these studies reduce the relationship between financial performance and sustainability disclosures to a “linear and incremental” model framework. The studies typically rate ESG scores on a scale of 0 to 100 and then focus on estimating the marginal effect of these scores on financial performance through econometric models. However, these ESG scores are based on companies’ own declarations and are created using weighting methodologies applied by rating agencies. Therefore, these data contain both methodological subjectivity and bias across sectors. This bias is thought to seriously limit the capacity of ESG scores to reflect real corporate differences between companies, particularly in emerging markets such as BIST.

Furthermore, the traditional econometric approach, which is dominant in the literature, largely disregards the interactions and non-linear relationships between corporate factors that shape financial performance. However, it is known that the impact of sustainability disclosures on companies’ financial performance has a complex structure that cannot be explained by a one-dimensional and linear relationship. Therefore, the need for methodological renewal is becoming increasingly apparent. In recent years, some studies have begun to suggest the use of predictive models, classification-based approaches, and explainable artificial intelligence techniques in financial performance analysis [18,19]. This enables more realistic modelling of the multidimensional, dynamic, and non-linear nature of the ESG-financial performance relationship.

2.4. Machine Learning Studies on Sustainability and Financial Performance

The literature examining the relationship between sustainability indicators and corporate/financial performance using machine learning has expanded rapidly in recent years; studies have tended to report both prediction success and explainability.

In predicting financial performance using deep learning and gradient-boosted trees (LSTMOPT, CNNOPT, XGBoost/LightGBM/RF), deep learning has been reported to be superior in accuracy; the predictive power increases with the use of lagged ESG data [20]. In a study comparing 15 models on a sample of Chinese A-shares, Extra Trees achieved the highest accuracy, but ESG disclosures were found to have a positive yet weak relationship with firm performance; environmental disclosures were shown to carry a more pronounced signal compared with other dimensions [21]. In predicting ESG scores with financial variables, ensemble methods (Voting/Bagging) produced very high R2 values, and country and firm size effects were found to be dominant determinants [22]. In investment funds, XGBoost regression strongly explains ESG scores and fund performance; some studies report that Random Forest/Gradient Boosting also outperforms [23,24]. In a global multi-sector analysis, it is noteworthy that ESG factors do not generally improve financial prediction accuracy; they only provide limited benefits in specific sectors (e.g., business services) [25].

In an EU/US comparison, it was emphasized that the environmental dimension (E) exhibits the strongest positive and non-linear (U-shaped) relationship with EBIT, and that data provider heterogeneity is a limiting factor [26]. Studies have also reported that sector knowledge and market indicators play a decisive role in predicting ESG scores, with Gradient Boosting achieving the highest accuracy [27,28].

In the European sample, high explanatory power (R2 approximately 88%) was achieved in profitability (EBIT) prediction using ML (RF/GB). It has been shown that the ESG-profitability relationship is often U-shaped and only contributes positively at high ESG levels; Net Sales, RoE, and the ESG score are among the main determinants [29]. Other studies found that ESG ratings can be reproduced with ML, and key determinants can be explained with SHAP; in the Taiwan sample, ELM/SVM/XGBoost performed strongly, while RF was relatively weak [30,31].

The general trend in these studies is that ESG information alone does not systematically increase short-term market returns or financial prediction accuracy across all sectors; however, it offers positive and non-linear contributions in specific contexts (country/sector) and at high ESG levels.

2.5. A Perspective Overlooked in the Literature: Dual Signals and Predictive Classification Approach

While the vast majority of studies in the literature on the relationship between sustainability reporting and financial performance are conducted using regression-based relationship tests based on ESG scores, there are very few classifier models that analyze the “presence/absence” signal effect of corporate disclosures and focus on predicting financial performance. However, investor behavior in capital markets is shaped not only by the existence of financial relationships, but also by the predictability of these relationships. In this context, binary disclosures such as companies establishing sustainability committees, publishing integrated reports, or presenting ESG indicators send a “corporate capacity signal” to the market, and these signals can be used as discriminative information in investor decisions [7,32]. However, the lack of studies measuring the classification power of these signals in the literature points to a significant methodological gap.

Another significant advantage of the dual signal approach is that it relies on more objective and reproducible criteria than ESG scores. In general, ESG scores depend on weighting systems developed by rating agencies. This can lead to these scores containing subjective assessments. In contrast, binary (yes/no) variables such as “Is a sustainability report published?” or “Has a sustainability committee been established?” are measured based on direct evidence. This evidence is obtained from information contained in companies’ reports, which are prepared in accordance with relevant legislation. This measurement approach relatively reduces methodological subjectivity and increases comparability between companies. Such sustainability and governance-based signals play a critical role, particularly in emerging markets. This is because these signals are interpreted as threshold indicators showing whether the corporate structure has been established at a minimum level [33]. In other words, even simple answers to questions such as “Is there a relevant report? Has a relevant committee been established?” serve as a fundamental signal to investors regarding the company’s corporate capacity.

Furthermore, since most relationship tests in the literature are limited to linear regression models, they cannot provide analytical insight into the extent to which a variable with multidimensional and non-linear dynamics, such as financial performance, can be predicted from sustainability explanations. At this point, machine learning-based classification models offer a new methodological contribution to the literature because they can naturally capture interactions between variables and non-linear structures. Tree-based learning algorithms such as Random Forest and XGBoost allow testing of the discriminatory power of binary indicators in classifying financial performance as high/low and reveal the market signal value of these indicators based on predictive accuracy [34,35].

When examining machine learning-based financial classification studies in the literature, it is evident that models largely rely on financial ratios and macroeconomic variables. Dual indicators related to governance activities and sustainability reporting are almost entirely absent from these studies. This is a significant shortcoming. It points to a critical research gap, particularly in emerging markets, regarding measuring how signals from corporate sustainability disclosures resonate with investor perceptions. This gap has implications not only for theoretical discussions but also for policymakers and decision makers. This is because the effectiveness of regulations on sustainability reporting depends on whether these disclosures truly reflect the company’s financial performance in a distinctive manner. This is the fundamental issue.

The machine learning-based classification approach developed in this study contributes to the governance and sustainability literature at a different level of proposition. The study does not merely test whether there is a relationship between sustainability indicators and financial performance; it also tests the distinguishing power of governance and sustainability disclosures on financial performance. In short, it seeks not only to detect the interaction but also to answer the question “How well does it distinguish?” The main contribution of the study is that it adopts a prediction-oriented framework rather than an explanation-oriented one. Rather than modelling causal effects, it presents a predictive paradigm that measures the signaling power of variables. It aims to produce an analytical answer to the question “To what extent does the market view sustainability disclosures as a set of discriminative information?” This question has been largely unanswered in the literature.

2.6. Gap in the Literature and Contribution of This Study

A review of the existing literature reveals that the relationship between sustainability reporting and financial performance has largely been analyzed through regression-based causality tests and graded ESG scores. This approach focuses on measuring the linear effect of a company’s sustainability performance on financial outcomes; however, it remains limited regarding predictive capacity and discriminatory power that directly reflect the decision-making processes of the capital market. Particularly in the context of emerging markets, factors such as the methodological subjectivity of ESG scores, the lack of data standardization, and the limited inclusiveness of rating agencies reduce the generalizability of the findings in the literature. Furthermore, most of these studies treat financial performance variables as continuous measurements and do not analytically model the distinction between “high-performing firms and non-performing firms,” which is critical in investors’ decision making processes.

In this context, a notable gap in the literature is the untested distinguishability of financial performance based on governance signals, which are either present or absent in sustainability disclosures. However, unlike ESG scores, most corporate reporting practices are based on objective disclosures in publicly available documents and are considered a “signal of corporate credibility” for investors in emerging markets where information asymmetry is high. Although existing studies have theoretically discussed the impact of these signals on investor perception, there appear to be no systematic and quantitative analyses measuring the predictive power of these signals on financial performance.

This study aims to fill this methodological gap in the literature and tests the discriminative capacity of binary indicators related to sustainability reporting in classifying the return on equity (RoE) of BIST companies as high/low using machine learning methods. Thus, unlike regression models aimed at explaining financial performance, this study develops a classification approach that is predictive and consistent with the investor perspective. The comparative application of algorithms such as Random Forest, XGBoost, and LightGBM not only shows which model achieves higher classification success but also reveals whether governance-sustainability indicators are meaningful regarding “signal strength”. In this respect, the study offers an empirical, prediction-oriented perspective on the use of corporate reporting signals and strengthens the evidence for their predictive relevance in emerging markets. Furthermore, the SHAP-based explainable artificial intelligence analysis used in the study transparently shows which variables influence the classification decision and to what extent, thus offering a solution to the “black box” problem frequently criticized in the literature. This methodological choice transforms the study from being solely focused on prediction performance into an explainability-based contribution that allows for theoretical interpretation of the findings.

3. Methodology

3.1. Model Specification and Hyperparameter Settings

This study employs three tree-based classification algorithms—Random Forest, XGBoost, and LightGBM—to predict whether a firm’s first-quarter RoE for 2025 falls into the high (H) or low (L) category. All models were implemented in Python 3.11 using scikit-learn (version 1.4), XGBoost (version 2.0), and LightGBM (version 4.1). To ensure full reproducibility, all procedures used a fixed random_state = 42, and the same 70/30 stratified train–test split was applied across algorithms.

A consistent model tuning framework was adopted to avoid overfitting and to ensure comparability. Hyperparameters were optimized via a 5-fold stratified cross-validation scheme on the training set. For XGBoost and LightGBM models, early stopping (patience = 50 rounds) was applied during tuning. The grids explored for each algorithm were as follows:

- Random Forest

- n_estimators: {200, 400, 600}

- max_depth: {None, 5, 10, 20}

- min_samples_split: {2, 5, 10}

- min_samples_leaf: {1, 2, 4}

- max_features: {“sqrt”, “log2”}

- XGBoost

- n_estimators: {300, 500, 800}

- learning_rate: {0.01, 0.05, 0.10}

- max_depth: {3, 4, 6}

- subsample: {0.7, 0.9, 1.0}

- colsample_bytree: {0.7, 0.9, 1.0}

- gamma: {0, 1}

- LightGBM

- n_estimators: {300, 500, 800}

- learning_rate: {0.01, 0.05, 0.10}

- max_depth: {−1, 4, 6}

- num_leaves: {15, 31, 63}

- feature_fraction: {0.7, 0.9, 1.0}

- bagging_fraction: {0.7, 0.9, 1.0}

- bagging_freq: {0, 1}

Model performance was evaluated using Accuracy, Precision (Macro), Recall (Macro), F1 (Macro), AUC, and Balanced Accuracy. All models were evaluated using a standard decision threshold of θ = 0.50, which classifies a firm into the high (H) class if the predicted probability p(H) ≥ 0.50. The majority-class baseline model was computed using the same test set to provide a transparent reference point. All SHAP analyses were conducted with the shap package (version 0.44), using the TreeExplainer for tree-based models.

This specification provides a reproducible and transparent model card for the analysis, in line with the editor’s request for methodological clarity.

3.2. Data Description, Variable Definitions, and Thresholding Rules

The aim of this analysis is to develop a machine-learning framework grounded in the presence of sustainability and governance indicators to classify the return on equity (RoE) levels of firms listed on BIST in an emerging capital market setting into high/low (H/L) categories and to quantify the discriminative power of these features. By comparing alternative machine learning algorithms used for classification, the study seeks to obtain generalizable and time-robust classification performance and, through explainability analyses, to identify which compliance elements systematically separate RoE classes.

Whereas the sustainability and financial performance literature has largely focused on regression and ESG score-based tests of association, the predictive classification perspective and the separating capacity of binary governance signals have been relatively underexamined. Yet, regulatory pressure and investors’ need for rapid, replicable screening make models that operate with low-cost, transparent input sets particularly valuable.

Within this study, the RoE of 427 BIST-listed firms is modelled using sustainability reporting and governance indicators as features. The choice to define the sample as 427 firms across multiple industries reflects several methodological considerations: the pursuit of external validity and generalizability, regulatory and accounting comparability, data accessibility and disclosure quality, and the desire to increase empirical power. All data were obtained from the Public Disclosure Platform (KAP) of the Capital Markets Board of Türkiye (SPK).

The dependent variable, RoE, is measured as of Q1 2025 (t). The independent variables are firms’ sustainability disclosures and governance practices for the 2024 fiscal period (t − 1). Two considerations motivate this design. The first is temporal precedence and the avoidance of simultaneity bias: using explanatory variables from t − 1 to account for financial performance at t helps limit reverse causality and contemporaneous common shocks (e.g., market volatility, regulatory changes). Second, the inherent reporting lag in sustainability and annual reports means that investors, when assessing next-period financial outcomes, effectively rely on prior-period corporate practices. Accordingly, the information set used here aligns with investors’ realistic information access.

Although quarterly profitability measures may exhibit seasonal or sector-driven volatility, Q1 RoE was selected because it represents the most recent financial performance available to investors at the time of prediction. Using the immediately subsequent reporting period (t) is consistent with a forward-looking classification design, where sustainability disclosures from year t − 1 are used to predict early-period performance in year t. Nevertheless, the study acknowledges that future research may incorporate annual RoE, sector-adjusted profitability ratios, or multiple-period averages to assess the robustness of the observed patterns.

From a machine learning standpoint, this design also constrains prediction to the information set available to a real-world researcher/decision maker and, crucially, mitigates artificially inflated accuracies due to data leakage. Put differently, the temporal separation between 2024 sustainability indicators (features) and Q1-2025 RoE (target) prevents target-period information from inadvertently entering the model, thereby strengthening the reproducibility of findings. Numerous recent cases across scientific fields have shown that leakage can systematically overstate the results of ML-based studies. For this reason, a “lagged” information structure for prediction is methodologically recommended [18]. The model for this study is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Variable definitions, thresholding rules, and coding scheme.

Note for ISDK variable: In the Turkish corporate governance framework, this indicator reflects the presence of a board-level Audit Committee (Denetimden Sorumlu Komite) established in accordance with the Capital Markets Board Communiqué on Corporate Governance (II-17.1) and the annexed Corporate Governance Principles (Corporate Governance Principles Section 4.5, Principle 4.5.9). The Audit Committee is responsible for overseeing the integrity of financial reporting, internal control and compliance and, in practice, contributes to the oversight of non-financial and sustainability-related reporting and risks in coordination with other board committees. ISDK does not denote a separate, stand-alone “sustainability audit committee”.

As shown in Table 1, the median split was preferred because it is distribution-robust and less sensitive to extreme sector-specific profitability differences. Alternative thresholds such as quartile-based splits, industry-adjusted medians, or continuous modelling were also considered. However, given the cross-industry nature of the sample, a median-based rule provides the most interpretable and sector-neutral benchmark. Future robustness checks may incorporate alternative cut-offs to confirm that classification performance does not materially depend on the threshold definition.

Building on this thresholding structure, the binary rating of RoE relative to the median (H = 1/L = 0) and the coding of the sustainability indicators as Yes = 1/No = 0 are motivated by several considerations. First, median-based thresholding for RoE provides a classification that is less sensitive to extreme observations than the mean, thereby limiting the extent to which measurement error and volatility stemming from accounting policies degrade model performance. In addition, the sample spans firms from heterogeneous industries whose capital intensity and cyclicality structurally differentiate RoE levels. Defining “high/low” relative to the median yields a reference that is independent of sectoral composition and supports a directly interpretable output for policymakers and investors, e.g., “a firm exceeding the median exhibits relatively strong performance”.

Coding the independent variables on a present/absent basis furnishes an objective criterion grounded in regulation and publicly disclosed reports, reducing coder subjectivity and measurement error compared with graded rating scales. These indicators also function as threshold signals of whether a minimum governance infrastructure is in place. Accordingly, the binary (present/absent) scheme is designed to distinguish between firms that surpass the minimum corporate capacity threshold and those that do not.

4. Analyses and Empirical Results

This section presents the empirical results in four steps. We begin with descriptive counts by variable to characterize the sample and class distributions. We then assess marginal (bivariate) associations between the high/low RoE classes and each binary sustainability/governance indicator using the Chi-square test and Cramér’s V. Next, we compare the out-of-sample performance of three tree-based classifiers (Random Forest, XGBoost and LightGBM) under a common evaluation protocol. Finally, we provide model-agnostic explanations via TreeSHAP to identify which disclosures and governance features contribute most to the classification decision, thereby linking predictive evidence to interpretable signals relevant for investors and policymakers.

- Step 1. Descriptive Counts by Variable (Firm-Level Frequencies)

Table 2 reports the number of firms for the RoE class distribution and for the binary governance/sustainability indicators. For the dependent variable, firm counts are presented under the Low–High RoE classes; for the independent variables, counts are presented under the No–Yes codes, thereby documenting the binary coding scheme used in the analysis.

Table 2.

Firm counts by RoE class and binary indicators.

- Step 2. Chi-Square Test and Cramér’s V (Bivariate Association)

In the second step of the analysis, to evaluate the marginal (bivariate) association between RoE (H/L) and the binary sustainability indicators (ISUS, ICOM, IESG, IREP, IMNG, ISDK), we employ the Chi-square test of independence and Cramér’s V as an effect-size measure. The Chi-square test addresses whether the RoE class and each binary indicator are independent, whereas Cramér’s V quantifies the strength (intensity) of any association. In short, the Chi-square p-value tests “Is there an association?”, while Cramér’s V answers “How strong is the association?”. Table 3 summarizes the results of this analysis.

Table 3.

Bivariate association between RoE class (H/L) and binary indicators: Pearson’s χ2 and Cramér’s V.

Bivariate associations between the binary indicators and the RoE high/low class were assessed using Pearson’s Chi-squared tests. All x2 statistics for 2 × 2 tables were computed without Yates’ continuity correction. Tests were performed in SPSS (version 20). We report the Pearson χ2 statistic without continuity correction and the corresponding Cramér’s V.

Table 3 indicates weak statistical evidence only for ISUS at the p ≤ 0.10 level, with a small effect size (Cramér’s V, approximately 0.08). No marginal relationship was observed in other variables regarding both significance and effect size. This result indicates that binary and superficial relationships are limited and, therefore, the use of multivariate/interactive machine learning algorithms is analytically necessary.

- Step 3. Machine Learning Classifiers and Comparative Performance

This study addresses a binary classification task, where firms are classified into High RoE (1) versus Low RoE (0) using binary (0/1) sustainability and governance indicators for a sample of 427 firms. In this context, tree-based ensemble methods Random Forest (bagging), XGBoost, and LightGBM (boosting) are selected because, for medium-scale tabular data, they offer a well-established balance of predictive performance, flexibility, and interpretability. These approaches explicitly capture non-linear patterns and feature interactions, require no scaling/standardization, handle binary/categorical attributes natively, and yield explainability outputs via feature importance [19,34,36]. Accordingly, they are well suited to uncover the non-linear and interactional relations between financial indicators and sustainability disclosures.

Random Forest is a bagging-based ensemble classifier that aggregates predictions from many feature-subsampled decision trees via voting/averaging, reducing inter-tree correlation and thereby lowering generalization error [34]. XGBoost is a scalable, regularized implementation of gradient-boosted trees; with sparsity-aware splitting, weighted-quantile sketch and system-level optimizations, it achieves high accuracy and speed on large tabular datasets [35]. LightGBM accelerates histogram-based gradient boosting using GOSS (Gradient-based One-Side Sampling) and EFB (Exclusive Feature Bundling), and, with its preference for deeper trees, provides an efficient and memory-friendly boosting library [37].

The principal rationale for employing this trio is that bagging (Random Forest) and boosting (XGBoost/LightGBM) exhibit different bias–variance profiles; comparing all three on the same dataset allows us to assess robustness and reduce the risk that findings are algorithm-specific [38,39].

All three models were trained using a five-fold cross-validation procedure on the training set to reduce overfitting and ensure generalizable performance. Hyperparameters were tuned using a restricted grid search focusing on commonly influential parameters such as maximum tree depth, number of estimators, learning rate, and subsampling ratios. These optimization steps follow standard machine-learning practice and help ensure that the reported model performance is not driven by arbitrary parameter choices.

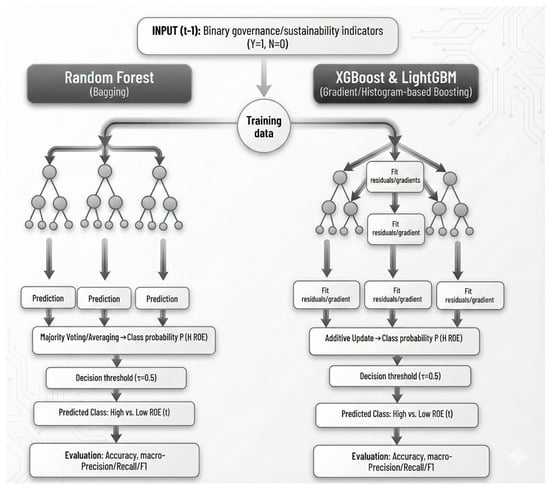

In this study, the classification pipeline ingests firm-level binary governance/sustainability indicators from period t − 1 (Yes = 1, No = 0) as inputs and aims to predict the RoE class (high vs. low) at period t Random Forest aggregates parallel trees by majority voting/averaging, whereas XGBoost and LightGBM build trees sequentially via additive updates to minimize a regularized loss. Each model produces the class probability P (High RoE), which, unless otherwise stated, is mapped to a predicted class using a decision threshold . Performance is evaluated on a held-out test set (30%) using Accuracy, macro-Precision/Recall, macro-F1. The process is depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Classification workflows for Random Forest, XGBoost, and LightGBM (BIST; RoE H/L; binary governance/sustainability indicators; 70% train/30% test).

The analysis findings are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

(a). Model comparison—binary RoE (0/1). (b) Confusion Matrices for the Best Model (XGBoost) and the Majority-Class Baseline (Test Set).

As shown in Table 4, all models yield extremely limited discrimination power, with ROC(AUC) values ranging from 0.48 to 0.53. In practical terms, these AUC levels are almost indistinguishable from random classification (AUC = 0.50). XGBoost performs only marginally above the majority-class baseline (AUC = 0.526 vs. 0.500), while LightGBM and Random Forest remain at or below random-classification levels. Accuracy, balanced accuracy, and macro-averaged F1 scores are all tightly clustered around the majority-class prevalence, indicating that the models do not provide a practically usable screening tool for distinguishing high-RoE from low-RoE firms. Instead, the results should be interpreted as evidence that, under current reporting practices, binary governance/sustainability indicators carry at most a very weak and unstable predictive signal for future RoE.

Beyond these supplementary indicators, Table 4 also reports the primary metrics used in the study. According to the results reported in Table 4, XGBoost ranks first regarding accuracy (0.5116). Random Forest (RF) attains an accuracy of 0.4884, and LightGBM yields 0.4731. Macro-averaged F1 scores confirm the same ordering (XGBoost 0.5100; RF 0.4869; LightGBM 0.4670). Macro-averaged Precision/Recall are similar across models (LightGBM: 0.4708/0.4711; XGBoost: 0.5120/0.5120; RF: 0.4879/0.4884), indicating that class-imbalance weighting does not distort the metrics.

For benchmarking, model performance is compared against the majority-class baseline. This reference corresponds to the accuracy obtained by predicting the most frequent class in the test set for all observations, a widely used and recommended practice to make the impact of class distribution explicit, especially when reporting accuracy [40]. As noted, the data are split into 70% training/30% test. With a total of 427 observations, the test set contains approximately 427 × 0.30 = 128.1, i.e., about 129 observations. The accuracy of the majority-class baseline equals the prevalence of the majority class in the test set. When every observation is predicted as that class, the proportion correctly classified coincides with that prevalence. Given the definition of accuracy, [41,42], the baseline accuracy for a reference model that assigns all cases to the majority class is in the binary case, that is, the majority-class prevalence. Given the test-set prevalence , the majority-class baseline is approximately 0.504. Accordingly, XGBoost performs slightly above the majority-class reference, whereas Random Forest and LightGBM are at or below that level. This finding indicates that for this sample, separating RoE (H/L) based on sustainability indicators is a difficult task, and that the underlying signal is weak. Nevertheless, the modest improvement in binary classification is consistent with the small effect sizes observed in the earlier Chi-square/Cramér’s V analyses. Taken individually, the binary sustainability indicators appear to have limited discriminative power for RoE (H/L). Even so, because tree-based methods can capture feature interactions and non-linear patterns, XGBoost is able to surpass the majority class baseline.

Overall, the findings do not reveal a robust relationship between the binary sustainability indicators and RoE classes. Any predictive signal, if present at all, appears to be extremely weak, fragile, and of negligible practical importance for out-of-sample classification. This is consistent with the class balance provided by stratified partitioning and implies that there is no overfitting to a single class, with errors distributed across both classes. The limited improvement in binary classification is consistent with the small effect sizes observed in the previously presented Chi-square/Cramer’s V analyses. In summary, the discriminatory power of binary sustainability indicators individually appears low for RoE (H/L). Nevertheless, thanks to the ability of tree-based methods to capture feature interactions and non-linear patterns, XGBoost is seen to outperform the majority class reference.

To enable readers to directly examine class-wise prediction errors, Table 4 presents the confusion matrices for the best-performing model (XGBoost) and for the majority-class baseline on the held-out test set. These matrices provide a transparent view of false positives and false negatives for each RoE class and complement the summary metrics reported in Table 4. Table 4 reports the overall performance metrics, whereas Table 4 reports the corresponding confusion matrices (Panels A–B) for XGBoost and the majority-class baseline.

- Step 4. SHAP-Based Explainability Analysis

Step 3 reveals a significant finding: XGBoost is the only model that outperforms the majority class-based reference model. Therefore, in Step 4, Shapley Additive Explanations (SHAP) analysis will be applied to the XGBoost model to see which variables influence the classification decision and to what extent, and to examine the marginal contributions of these variables. In short, in Step 4, the model’s decision will be analyzed by breaking it down “feature by feature”.

SHAP is an explainability framework based on game theory and decomposes a single prediction produced by any machine learning model into marginal contributions at the feature level, i.e., Shapley values. It does this based on an additive decomposition structure. It is also a unique method that simultaneously provides desirable properties such as local accuracy, consistency, and missingness. Thanks to these qualities, it serves as an umbrella approach that brings different explanatory techniques together on common ground [43,44].

It is important to note that SHAP values are model-based, game-theoretic attributions rather than test statistics. In this study, SHAP is used purely as a descriptive explainability tool to summarize the magnitude and direction of feature contributions to the predicted probability of High RoE. We therefore do not attach p-values, confidence intervals, or formal notions of ‘statistical significance’ to SHAP values; inferential statements remain restricted to the classical tests reported in Step 2.

Because XGBoost is tree-based, we employ TreeSHAP, which yields exact, model-consistent attributions for tree ensembles. In addition to overall predictive accuracy, we thus identify which sustainability indicators increase or decrease the probability of High RoE, both at the global level (via the ranking of mean ∣SHAP∣) and at the local level (firm-specific explanations). This dual perspective enhances transparency and supports interpretation and policy inference in accounting and finance. Figure 2 presents TreeSHAP’s mechanics, exemplified by the IMNG variable.

Figure 2.

How TreeSHAP operates in tree ensembles: an IMNG-based example.

The results obtained from the SHAP analysis are provided in Table 5.

Table 5.

SHAP summary metrics.

Table 5 presents the SHAP analysis, which summarizes the relative contributions of the six corporate-governance indicators to the High RoE predictions. Ranking variables by their mean |SHAP| values shows that IMNG and IREP are the most influential features in the XGBoost model, followed by ISUS and ISDK, whereas IESG has the lowest SHAP importance. Thus, IMNG and IREP account for a large share of the model-based variation in the predicted probability of belonging to the High RoE class, even though their average directional effects differ.

The signed mean SHAP values complement this ranking by indicating the predominant direction of each variable’s contribution. For IMNG, the signed mean SHAP value is negative and only about 31% of its local SHAP contributions are positive; in approximately 69% of the cases IMNG reduces the predicted probability that a firm belongs to the High RoE group. In other words, IMNG is a strong but predominantly negative governance signal for current High RoE outcomes in our sample. By contrast, IREP tends to produce positive SHAP contributions for a larger share of observations, which is consistent with stronger internal reporting practices being associated with a higher probability of High RoE.

The signed mean SHAP value for ISUS is positive (approximately 0.0187) and its positive SHAP ratio is above 50% (52.35%), indicating a small but predominantly positive contribution to the predicted probability of High RoE. By contrast, IESG has a slightly negative signed mean SHAP value (approximately −0.0015), while its positive SHAP ratio remains relatively high (62.08%). This combination suggests a mixed pattern in which IESG contributes positively in a majority of observations, but a smaller subset of firms exhibits negative contributions that are large enough to pull the overall mean contribution marginally below zero. In contrast, although the signed mean SHAP value of ISDK is negative (−0.0181), its positive SHAP ratio is quite high (79.87%), suggesting that ISDK increases the model’s predicted probability of High RoE in most observations, while the overall average becomes slightly negative due to comparatively larger negative contributions in a smaller subset of cases.

Figure 3 shows the Shap beeswarm plot and dependency plots for IMNG, IREP and ICOM.

Figure 3.

SHAP beeswarm plot and dependency plots for the ICOM, IMNG, and IREP variables.

Figure 3 displays the SHAP beeswarm plot used to explain the model alongside the dependency plots for the ICOM, IMNG, and IREP variables. In the beeswarm plot at the top, each point represents an observation, the x-axis denotes the SHAP value (marginal contribution to the model output), and the colour scale indicates the level of the corresponding variable at the observation level. The spread of the points along the horizontal axis reveals that the effect of the variables on the prediction is distinctly heterogeneous in both direction and magnitude. For example, for IMNG and IREP, high values (red dots) are mostly associated with negative and positive SHAP values, respectively, whereas in some observations, the same colour tones also have SHAP values with opposite signs. Similarly, when the ICOM variable is high, it produces both positive and negative SHAP values, meaning that the same variable level can affect the prediction in a positive or negative manner in different observations. The dispersion of points of the same level (similar colour) to both the right and left suggests that the effect of the variable in question arises in interaction with other explanatory variables; thus implying that the assumption of a univariate linear effect is insufficient to capture the true data structure.

In the dependency graphs presented below, the SHAP distributions are distinctly separated for each level of the binary-coded ICOM, IMNG and IREP variables, but there is substantial dispersion within these distributions. For example, in the case of IREP = 1, although SHAP values are mostly concentrated in the positive region, there are also non-trivial negative contributions within the same group. Similarly, for IMNG and ICOM, it is noteworthy that positive and negative contributions coexist within each category. This structure implies that the multivariate contributions of these variables are relatively small on average, yet systematically non-zero at the level of individual observations. When such heterogeneous effects with opposite signs are aggregated, classical marginal analyses (e.g., univariate regression coefficients or group mean-difference tests) may report the average effect as ‘non-existent’ or negligible, because they simply average out local effects that operate in different directions across subgroups and interaction regimes. In contrast, the SHAP-based multivariate explainability approach disaggregates local contributions for each observation, thereby revealing heterogeneity and interaction patterns and showing that relationships which appear weak in marginal analyses can in fact be complex, non-linear and context-sensitive.

5. Discussion

This study departs from the dominant regression/ESG score paradigm in the sustainability–financial performance literature by introducing a predictive classification approach based on binary (present/absent) governance–sustainability indicators. Modelling RoE as high/low and defining predictors with yes/no codes reduces the subjectivity inherent in scoring methodologies for emerging markets. Using period (t − 1) disclosures to predict RoE at (t) enforces temporal ordering and mitigates the risk of simultaneity and data leakage. The findings show that XGBoost performs slightly above the majority-class baseline, whereas LightGBM and Random Forest are at or below that level. SHAP analyses indicate that, although some indicators rank relatively high in global importance, their average effects remain small and directionally heterogeneous. Notably, IMNG emerges as the most influential indicator in terms of mean |SHAP|, yet its signed mean SHAP value is negative and only about one third of its local SHAP contributions are positive. This pattern is consistent with governance reforms being implemented after periods of weak performance and with potential short-term profitability costs of compliance, so that stronger formal governance practices can coincide with a lower contemporaneous probability of High RoE in our sample.

From a strict methodological perspective, the most important result of this study is what the models fail to do: despite a carefully specified pipeline and comparative ensemble design, the classification performance remains essentially at the level of random guessing. This implies that, in their current form, binary “presence/absence” sustainability and governance signals are not capable of providing investors with a reliable ex ante tool for separating high-RoE from low-RoE firms. The contribution of the study therefore lies not in proposing a deployable prediction model, but in documenting a negative empirical result that highlights the limitations of existing disclosure practices in an emerging market context.

Within this framework, it demonstrates that simple “presence/absence”-type signals alone are not strong discriminators. However, these signals are not entirely ineffective. They produce context-sensitive weak signals. Furthermore, these signals can contribute to prediction performance, albeit to a limited extent, through feature interactions and non-linear patterns. At the methodological level, the use of a comparative ensemble classification approach in conjunction with TreeSHAP-based explainability in the analysis process of the study provides a transparent answer to two fundamental questions simultaneously: firstly, “Which model performs better?”, and secondly “Where and how does each indicator play a role in the decision boundary?” Thus, in this study, the path leading to the model’s decision is as important a benchmark as the model selection itself. The results obtained regarding policy and practice show that the impact of sustainability reporting and sustainability committees becomes stronger as content depth, governance quality, and data quality increase. In other words, as the corporate reporting structure matures, these models will become more meaningful. Thus, value creation and accountability capacity can be supported in a more consistent and sustainable manner at the organizational level.

6. Conclusions

This study presents a prediction framework that classifies the 2025 first-quarter RoE values of 427 companies listed on the BIST as “high/low” using sustainability/governance statements (indicated by yes/no codes) for the 2024 period. The XGBoost, LightGBM, and Random Forest models were compared on the same 70/30 stratified test sample, and the results regarding accuracy metrics were centered around the majority class-based reference value for all three algorithms. SHAP explanations were analyzed using the XGBoost model, which yielded the highest accuracy rate among the three algorithms used in the analysis phase. These analysis findings revealed that the indicators “Corporate Governance Report”, “Integrated Report” and “Sustainability Committee” rank higher in terms of SHAP-based global importance in the High RoE classification model. However, the associated average SHAP effects remain small, and the directions of their contributions are heterogeneously distributed across firms. This overall picture shows that the binary (yes/no) explanations of the independent variables used were not sufficient to strongly distinguish RoE classes on their own but instead produced weak but context-sensitive signals.

The findings also reveal the relative strengths and weaknesses of sustainability tools. While corporate reporting issues generate some relative signals, these effects appear to be small and heterogeneous, and the overall predictive power remains very limited. Based on these results, we do not interpret the current set of sustainability and governance indicators as a practically useful basis for RoE prediction. A corporate sustainability architecture that is more closely aligned with financial performance targets would require substantial improvements in the depth of content, governance quality, and data quality of sustainability practices. Only under such conditions might these tools eventually become more effective in supporting value creation and responding to stakeholder demands, and this possibility should be viewed as conditional and speculative rather than as a direct implication of our empirical results.

From a stakeholder perspective, the findings also offer several practical implications. For policy makers, the results highlight the need for more standardized, content-rich, and verifiable sustainability reporting frameworks. For corporate managers, the study underscores that the mere existence of committees or reports is insufficient unless supported by substantive governance quality and deeper disclosure practices. For investors, the weak but interpretable signals identified through SHAP suggest that report quality and underlying governance capacity should be evaluated beyond simple disclosure presence. For civil society organizations, the findings reinforce the importance of transparency, accountability, and independent assurance in strengthening the informational value of sustainability reporting. Finally, for the academic community, the study identifies promising avenues for integrating textual ESG analytics, hybrid modelling, and cross-market comparisons into future research.

Finally, studies in the literature have reached similar findings [14,15,16,17,20], and it is understood that sustainability indicators alone do not provide generalizable discriminatory power for all sectors; the effects are largely sensitive to sector/country conditions, the existence of corporate committees on this issue, and the quality of reports.

Using a broad sample, this study contributes to the discussion in the context of Turkey, a developing country, regarding methodology and application through comparative tree-based models and explainability tools. The findings indicate that the potential of sustainability committees and sustainability reports to enhance value and accountability capacity must be realized not only through formal existence, but primarily through substantive depth and governance quality. However, our results also suggest that these practices can have modest and, in some cases, negative short-term impacts on financial performance, which is consistent with the predominantly negative SHAP contributions of the most influential governance indicator to the High RoE class in our sample.

When all findings are evaluated together, the main result of this study shows that in their current form, dual sustainability and corporate governance signals have limited power to reliably distinguish RoE classes. However, these results do not overshadow the methodological strength of our study and its contribution to the literature. On the contrary, our framework, based on objective signals and a prediction-based classification method, suggests that current reporting practices may not always provide sufficiently rich or reliable market signals, particularly when disclosures are limited to simple presence/absence indicators. Furthermore, the use of SHAP analysis transparently shows which management signals are most considered by the model in predicting financial outcomes, providing an interpretable perspective for investor decision-making processes. Taken together, these findings demonstrate that binary governance and sustainability signals possess limited standalone explanatory power, yet remain theoretically meaningful within signaling and resource-based perspectives. The results therefore clarify how minimal disclosure structures function in emerging markets and highlight where more substantive reporting becomes necessary for predictive value creation. Overall, the study contributes empirical evidence that helps bridge theoretical expectations with the practical performance of simple corporate disclosure mechanisms.

Limitations and Directions for Future Research

This study is subject to several limitations that provide opportunities for future research. First, the sustainability and governance indicators are coded in a binary (yes/no) format, which restricts the granularity of information captured from corporate reports. As a result, subtle differences in reporting depth, content quality, or governance practices are not reflected in the models. Future studies may incorporate richer textual or quantitative ESG data, including the report length, narrative tone, disclosure specificity, or externally assured metrics. Second, model performance remains close to the majority-class benchmark across all algorithms, suggesting that the predictive signal contained in binary disclosures is inherently weak. This highlights the value of exploring alternative modelling strategies such as textual embeddings, topic modelling, or hybrid quantitative–qualitative approaches. Third, the use of quarterly RoE as the outcome variable may introduce noise due to seasonality and short-term fluctuations; future research can evaluate whether annual profitability metrics, multi-period averages, or sector-adjusted returns yield improved discriminative power. Finally, the empirical design focuses on firms listed on a single emerging market exchange (BIST), which may limit generalizability. Comparative analyses involving multiple countries or broader ESG regimes would help assess the extent to which the findings generalize across institutional settings. Future research could complement the present tree-based analysis with more traditional linear benchmarks, such as parsimonious or penalised logistic regression models, to further assess the robustness of the results.

Overall, the magnitude of these effects remains modest and heterogeneous, and the predictive improvement over a naïve majority-class baseline is slight.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.F.Ü.U. and B.T.; methodology, A.E.B. and G.D.D.; software, B.T.; validation, M.T. and N.K.; formal analysis, M.T., B.T. and N.K.; investigation, G.F.Ü.U. and B.T.; resources, A.E.B.; data curation, A.E.B.; writing—original draft preparation, G.F.Ü.U., M.T. and B.T.; writing—review and editing, G.F.Ü.U., M.T., A.E.B., N.K., B.T. and G.D.D.; visualization, B.T.; supervision, M.T. and G.D.D.; project administration, G.F.Ü.U. and M.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The financial data used in this study were obtained from publicly available KAP (Public Disclosure Platform of Türkiye) reports (https://www.kap.org.tr/tr) (accessed on 9 October 2025). Processed datasets and analysis files are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Global Reporting Initiative (GRI). GRI Sustainability Reporting Standards. 2023. Available online: https://www.globalreporting.org (accessed on 9 October 2025).

- Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB). SASB Standards. 2025. Available online: https://sasb.ifrs.org/ (accessed on 9 October 2025).

- IFRS Foundation. IFRS S1 General Requirements for Disclosure of Sustainability-Related Financial Information. 2023. Available online: https://www.ifrs.org/content/dam/ifrs/publications/pdf-standards-issb/english/2023/issued/part-a/issb-2023-a-ifrs-s1-general-requirements-for-disclosure-of-sustainability-related-financial-information.pdf?bypass=on (accessed on 9 October 2025).

- IFRS Foundation. IFRS S2 Climate-Related Disclosures. 2023. Available online: https://www.ifrs.org/content/dam/ifrs/publications/pdf-standards-issb/english/2023/issued/part-a/issb-2023-a-ifrs-s2-climate-related-disclosures.pdf?bypass=on (accessed on 9 October 2025).

- Freeman, R.E.E.; McVea, J. A Stakeholder Approach to Strategic Management. In The Blackwell Handbook of Strategic Management; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2005; Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1111/b.9780631218616.2006.00007.x (accessed on 9 October 2025).

- Suchman, M.C. Managing Legitimacy: Strategic and Institutional Approaches. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 571–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, M. Job Market Signaling. Q. J. Econ. 1973, 87, 355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J. Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friede, G.; Busch, T.; Bassen, A. ESG and financial performance: Aggregated evidence from more than 2000 empirical studies. J. Sustain. Financ. Invest. 2015, 5, 210–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velte, P. Does ESG performance have an impact on financial performance? Evidence from Germany. J. Glob. Responsib. 2017, 8, 169–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atan, R.; Alam, M.M.; Said, J.; Zamri, M. The impacts of environmental, social, and governance factors on firm performance. Manag. Environ. Qual. Int. J. 2018, 29, 182–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eccles, R.G.; Ioannou, I.; Serafeim, G. The Impact of Corporate Sustainability on Organizational Processes and Performance. Manag. Sci. 2014, 60, 2835–2857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derwall, J.; Verwijmeren, P. The Economic Virtues of SRI and CSR; Erasmus Research Institute of Management (ERIM): Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Revelli, C.; Viviani, J. Financial performance of socially responsible investing (SRI): What have we learned? A meta-analysis. Bus. Ethics A Eur. Rev. 2015, 24, 158–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auer, B.R. Do socially responsible investment policies add or destroy European stock portfolio value? J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 135, 381–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aras, G.; Crowther, D. Corporate sustainability reporting: A study in disingenuity? J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 87, 279–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kılıç, M.; Kuzey, C. Determinants of climate change disclosures in the Turkish banking industry. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2019, 37, 901–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapoor, S.; Narayanan, A. Leakage and the reproducibility crisis in machine-learning-based science. Patterns 2023, 4, 100804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grinsztajn, L.; Oyallon, E.; Varoquaux, G. Why do tree-based models still outperform deep learning on typical tabular data? In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS 2022); Curran Associates, Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2022; Volume 35, pp. 507–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, W.L.; Lin, Y.L.; Lai, J.P.; Liu, Y.H.; Pai, P.F. Forecasting Corporate Financial Performance Using Deep Learning with Environmental, Social, and Governance Data. Electronics 2025, 14, 417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dossa, J.V.; Ukwuoma, C.C.; Thomas, D.; Dossa, J.M.; Gopang, A.A. Prediction of nexus among ESG disclosure and firm Performance: Applicability, explainability and implications. Innov. Green Dev. 2025, 4, 100261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsayyad, M.; Fadel, S.M. Predicting ESG scores using firms’ financial indicators: A machine learning regression approach. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Momparler, A.; Carmona, P.; Climent, F. Catalyzing Sustainable Investment: Revealing ESG Power in Predicting Fund Performance with Machine Learning. Comput. Econ. 2025, 65, 1617–1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin-Melero, I.; Gomez-Martinez, R.; Medrano-Garcia, M.L.; Hernandez-Perlines, F. Comparison of sectorial and financial data for ESG scoring of mutual funds with machine learning. Financ. Innov. 2025, 11, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dincă, M.S.; Ciotlăuși, V.; Akomeah, F. Estimating the Impact of ESG on Financial Forecast Predictability Using Machine Learning Models. Int. J. Financ. Stud. 2025, 13, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palynska, M.; Medda, F.; Caivano, V.; Di Stefano, G.; Scalese, F. The Impact of the ESG Factor on Industrial Performance: An Analysis Using Machine Learning Techniques; CONSOB: Rome, Italy, 2024; Available online: https://www.consob.it/web/consob-and-its-activities/abs_sf/-/asset_publisher/coLw917vXYH5/content/sustainable-finance-no.-4/718268?utm_source (accessed on 9 October 2025).

- Jiang, X. Predicting corporate ESG scores using machine learning: A comparative study. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Financial Technology and Business Analysis, San Francisco, CA, USA, 27–28 July 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y. Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Business and Policy Studies; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- D’Amato, V.; D’Ecclesia, R.; Levantesi, S. Firms’ profitability and ESG score: A machine learning approach. Appl. Stoch. Model. Bus. Ind. 2023, 40, 243–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Vitto, A.; Marazzina, D.; Stocco, D. ESG ratings explainability through machine learning techniques. Ann. Oper. Res. 2023, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.Y.; Hsu, B.W. Empirical Study of ESG Score Prediction through Machine Learning—A Case of Non-Financial Companies in Taiwan. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connelly, B.L.; Certo, S.T.; Ireland, R.D.; Reutzel, C.R. Signaling theory: A review and assessment. J. Manag. 2011, 37, 39–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Gong, M.; Zhang, X.Y.; Koh, L. The impact of environmental, social, and governance disclosure on firm value: The role of CEO power. Br. Acc. Rev. 2018, 50, 60–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breiman, L. Random forests. Mach. Learn. 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Guestrin, C. XGBoost: A Scalable Tree Boosting System. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, New York, NY, USA, 13–17 August 2016; pp. 785–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, J.H. Greedy function approximation: A gradient boosting machine. Ann. Stat. 2001, 29, 1189–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, G.; Meng, Q.; Finley, T.; Wang, T.; Chen, W.; Ma, W.; Ye, Q.; Liuet, T.-Y. LightGBM: A highly efficient gradient boosting decision tree. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; Guyon, I., von Luxburg, U., Bengio, S., Wallach, H., Fergus, R., Vishwanathan, S.V.N., Garnett, R., Eds.; Curran Associates, Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 3146–3154. [Google Scholar]

- Martinović, M.; Dokic, K.; Pudić, D. Comparative Analysis of Machine Learning Models for Predicting Innovation Outcomes: An Applied AI Approach. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 3636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tagaeva, S.; Sodikova, S.; Usmanova, N.; Usmonov, F. Ensemble classifiers for news classification: Methods and applications. In AIP Conference Proceedings; AIP Publishing: Melville, NY, USA, 2025; p. 070009. Available online: https://pubs.aip.org/aip/acp/article-lookup/doi/10.1063/5.0300378 (accessed on 9 October 2025).

- Ghanem, M.; Ghaith, A.K.; El-Hajj, V.G.; Bhandarkar, A.; De Giorgio, A.; Elmi-Terander, A.; Bydon, M. Limitations in Evaluating Machine Learning Models for Imbalanced Binary Outcome Classification in Spine Surgery: A Systematic Review. Brain Sci. 2023, 13, 1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David Martin Ward Powers. Evaluation: From precision, recall and F-measure to ROC, informedness, marked-ness; correlation. J. Mach. Learn. Technol. 2011, 2, 37–63. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn, M.; Johnson, K. Applied Predictive Modeling; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Lundberg, S.M.; Lee, S.I. A unified approach to interpreting model predictions. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; Curran Associates, Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Lundberg, S.M.; Erion, G.; Chen, H.; DeGrave, A.; Prutkin, J.M.; Nair, B.; Katz, R.; Himmelfarb, J.; Bansal, N.; Lee, S.I. From local explanations to global understanding with explainable AI for trees. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2020, 2, 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.