Electric Vehicle Adoption: Japanese Consumer Attitudes, Inter-Vehicle Transitions, and Effects on Well-Being

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Description

2.2. Variables and Measures

3. Methodology

4. Results

5. The Choice Between Electric Vehicles and Fossil Fuel Vehicles

6. The Choice Between Electric Vehicles and Fossil Fuel Vehicles—Subsamples

Well-Being and Types of Vehicles

7. Discussion

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- IPCC. Climate Change 2023 Synthesis Report. 2023. Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/syr/downloads/report/IPCC_AR6_SYR_SPM.pdf (accessed on 10 November 2023).

- United Nations. Climate Action. 2015. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/climatechange/net-zero-coalition (accessed on 10 November 2023).

- MOE. The Global Warming Countermeasures. 2021. Available online: https://www.env.go.jp/earth/ondanka/keikaku/211022.html (accessed on 15 August 2025).

- Helmers, E.; Weiss, M. Advances and Critical Aspects in the Life-Cycle Assessment of Battery Electric Cars. Energy Emiss. Control. Technol. 2017, 5, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumann, M.; Salzinger, M.; Remppis, S.; Schober, B.; Held, M.; Graf, R. Reducing the Environmental Impacts of Electric Vehicles and Electricity Supply: How Hourly Defined Life Cycle Assessment and Smart Charging Can Contribute. World Electr. Veh. J. 2019, 10, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Rubens, G.Z.; Noel, L.; Sovacool, B.K. Dismissive and Deceptive Car Dealerships Create Barriers to Electric Vehicle Adoption at the Point of Sale. Nat. Energy 2018, 3, 501–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCollum, D.L.; Wilson, C.; Bevione, M.; Carrara, S.; Edelenbosch, O.Y.; Emmerling, J. Interaction of Consumer Preferences and Climate Policies in the Global Transition to Low-Carbon Vehicles. Nat. Energy 2018, 3, 664–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, X.; Liu, X.; Zuo, J. The Development of New Energy Vehicles for a Sustainable Future: A Review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 42, 298–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huangfu, J.; Wei, W.; Yu, L.; Li, G. The Impact of Environmental Policy Stringency and Oil Prices on Innovation: Evidence from the New Energy Vehicle Industry in China. Econ. Anal. Policy 2025, 85, 979–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Liang, Y.; Yu, E.; Rao, R.; Xie, J. Review of Electric Vehicle Policies in China: Content Summary and Effect Analysis. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 70, 698–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapustin, N.O.; Grushevenko, D.A. Long-Term Electric Vehicles Outlook and Their Potential Impact on Electric Grid. Energy Policy 2020, 137, 111103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, V.; Singh, V.; Vaibhav, S. A Review and Simple Meta-Analysis of Factors Influencing Adoption of Electric Vehicles. Transp. Res. Part D 2020, 86, 102436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.C.-E.; Chao, C.-W. Equal Rights for Gasoline and Electricity? The Dismantling of Fossil Fuel Vehicle Phase-Out Policy in Taiwan. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2022, 89, 102571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonilla, D.; Soberon, H.A.; Galarza, O.U. Electric Vehicle Deployment & Fossil Fuel Tax Revenue in Mexico to 2050. Energy Policy 2022, 171, 113276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asgarian, F.; Hejazi, S.R.; Khosroshahi, H. Investigating the Impact of Government Policies to Develop Sustainable Transportation and Promote Electric Cars, Considering Fossil Fuel Subsidies Elimination: A Case of Norway. Appl. Energy 2023, 347, 121434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debnath, R.; Bardhan, R.; Reiner, D.M.; Miller, J.R. Political, Economic, Social, Technological, Legal and Environmental Dimensions of Electric Vehicle Adoption in the United States: A Social-Media Interaction Analysis. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 152, 111707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Needell, Z.A.; McNerney, J.; Chang, M.T.; Trancik, J.E. Potential for Widespread Electrification of Personal Vehicle Travel in the United States. Nat. Energy 2016, 1, 16112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mersky, A.C.; Sprei, F.; Samaras, C.; Qian, Z.S. Effectiveness of Incentives on Electric Vehicle Adoption in Norway. Transp. Res. Part D 2016, 46, 56–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sierzchula, W.; Bakker, S.; Maat, K.; Van Wee, B. The Influence of Financial Incentives and Other Socio-Economic Factors on Electric Vehicle Adoption. Energy Policy 2014, 68, 183–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Zhan, W.; Hu, Y. Consumer Purchase Intention of Electric Vehicles in China: The Roles of Perception and Personality. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 204, 1060–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, E.; Moore, D.; Kelleher, L.; Brereton, F. Barriers to Electric Vehicle Uptake in Ireland: Perspectives of Car-Dealers and Policy-Makers. Case Stud. Transp. Policy 2019, 7, 118–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Lee, G.; Park, J.Y.; Hong, J.; Park, J. Consumer Intentions to Purchase Battery Electric Vehicles in Korea. Energy Policy 2019, 132, 736–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, E.; Lim, J.; Cho, Y. Understanding the Emergence and Social Acceptance of Electric Vehicles as Next-Generation Models for the Automobile Industry. Sustainability 2018, 10, 662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thananusak, T.; Rakthin, S.; Tavewatanaphan, T.; Punnakitikashem, P. Factors Affecting the Intention to Buy Electric Vehicles: Empirical Evidence from Thailand. Int. J. Electr. Hybrid Veh. 2017, 9, 361–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenn, A.; Laberteaux, K.; Clewlow, R. New Mobility Service Users’ Perceptions on Electric Vehicle Adoption. Int. J. Sustain. Transp. 2018, 12, 8318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, S.; Shi, Y.; Adan, D.; Luo, W.; Al Humdan, E. Role of Environmental Awareness & Self-Identification Expressiveness in Electric-Vehicle Adoption. Transportation 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhat, F.A.; Verma, A. Consumer Intention to Accept Electric Two-Wheelers in India: A Valence Theory Approach to Unveil the Role of Identity and Utility. Transportation 2023, 52, 537–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.; Thill, J.-C. Who Is Inclined to Buy an Autonomous Vehicle? Empirical Evidence from California. Transportation 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okada, T.; Tamaki, T.; Managi, S. Effect of Environmental Awareness on Purchase Intention and Satisfaction Pertaining to Electric Vehicles in Japan. Transp. Res. Part D 2019, 67, 503–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansson, J. Consumer Eco-Innovation Adoption: Assessing Attitudinal Factors and Perceived Product Characteristics. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2011, 20, 192–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javid, R.J.; Nejat, A. A Comprehensive Model of Regional Electric Vehicle Adoption and Penetration. Transp. Policy 2017, 54, 30–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Kumar, V.R.; Sidhpuria, M. A Study on the Adoption of Electric Vehicles in India: The Mediating Role of Attitude. Vis. J. Bus. Perspect. 2019, 24, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.K.; Oh, J.; Park, J.H.; Joo, C. Perceived Value and Adoption Intention for Electric Vehicles in Korea: Moderating Effects of Environmental Traits and Government Supports. Energy 2018, 159, 799–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sierzchula, W. Factors Influencing Fleet Manager Adoption of Electric Vehicles. Transp. Res. Part D 2014, 31, 126–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, M.; Higgins, C.D.; Ferguson, M.; Réquia, W.J. The Influence of Vehicle Body Type in Shaping Behavioral Intention to Acquire Electric Vehicles: A Multi-Group Structural Equation Approach. Transp. Res. Part A 2018, 116, 54–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdem, C.; Senturk, I.; Simsek, T. Identifying the Factors Affecting the Willingness to Pay for Fuel-Efficient Vehicles in Turkey: A Case of Hybrids. Energy Policy 2010, 38, 3038–3043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezvani, Z.; Jansson, J.; Bodin, J. Advances in Consumer Electric Vehicle Adoption Research: A Review and Research Agenda. Transp. Res. Part D 2015, 34, 122–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habich-Sobiegalla, S.; Kostka, G.; Anzinger, N. Electric Vehicle Purchase Intentions of Chinese, Russian and Brazilian Citizens: An International Comparative Study. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 205, 188–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thøgersen, J.; Ebsen, J.V. Perceptual and Motivational Reasons for the Low Adoption of Electric Cars in Denmark. Transp. Res. Part F 2019, 65, 89–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, M.; Banister, D.; Bishop, J.D.; McCulloch, M.D. Realizing the Electric-Vehicle Revolution. Nat. Clim. Change 2012, 2, 328–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Will, C.; Lehmann, N.; Baumgartner, N.; Feurer, S.; Jochem, P.; Fichtner, W. Consumer Understanding and Evaluation of Carbon-Neutral Electric Vehicle Charging Services. Appl. Energy 2022, 313, 118799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.-J.; Dua, R.; Bansal, P. Why Chinese Car Owners May Not Repurchase Electric Vehicles? Transp. Res. Part D 2025, 139, 104557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mashrur, S.M.; Mohamed, M. Uncovering Factors Affecting Consumers’ Decisions for Pre-Owned Electric Vehicles. Transp. Res. Part D 2025, 139, 104555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, S. Assessment of Electric Vehicle Repurchase Intention: A Survey-Based Study on the Norwegian EV Market. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2021, 11, 100439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piao, X.; Managi, S. Altruistic Behavior for Environmental Conservation and Life Satisfaction: Evidence from 37 Nations. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2025, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steg, L.; Bolderdijk, J.W.; Keizer, K.; Perlaviciute, G. An Integrated Framework for Encouraging Pro-Environmental Behaviour: The Role of Values, Situational Factors and Goals. J. Environ. Psychol. 2014, 38, 104–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, W.H. Econometric Analysis; Pearson: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Wooldridge, J. Econometric Analysis of Cross Section and Panel Data; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Environment Zeb Portal. 2021. Available online: https://www.env.go.jp/earth/zeb/detail/02.html (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- Yu, T.; Teoh, A.P.; Liao, J.; Wang, C. Determinants of Switching Intention to Adopt Electric Vehicles: A Comparative Analysis of China and Malaysia. Technol. Soc. 2025, 82, 102949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Description |

|---|---|

| Dependent variables | |

| Owning an electric vehicle | Equals one if the individual owns a fully battery electric vehicle; otherwise, equals zero. |

| Owning a fossil fuel vehicle | Equals one if the individual owns a fossil fuel vehicle; otherwise, equals zero. |

| Life satisfaction | Please imagine a ladder with steps ranging from 0 at the bottom to 10 at the top. The top of the ladder (=10) represents the best possible life you can imagine, and the bottom (=0) represents the worst possible life you can imagine. On which step of the ladder do you feel you currently stand? |

| Happiness | “In the last two weeks, how often have you felt happiness?” often = 4, sometimes = 3, rarely = 2, and not at all = 1. |

| Stress | “In the last two weeks, how often have you felt stress?” often = 4, sometimes = 3, rarely = 2, and not at all = 1. |

| Depress | “In the last two weeks, how often have you felt depression?” often = 4, sometimes = 3, rarely = 2, and not at all = 1. |

| Joyful | “In the last two weeks, how often have you felt joyful?” often = 4, sometimes = 3, rarely = 2, and not at all = 1. |

| Anxiety | “In the last two weeks, how often have you felt anxiety?” often = 4, sometimes = 3, rarely = 2, and not at all = 1. |

| Anger | “In the last two weeks, how often have you felt anger?” often = 4, sometimes = 3, rarely = 2, and not at all = 1. |

| Independent variables | |

| Knowledge of natural environmental issues | The knowledge levels with regard to ten kinds of nature-related issues—natural disasters (typhoons, tsunamis, earthquakes), forest conservation and afforestation, global warming, depletion of the ozone layer, biodiversity loss (e.g., animal protection), air pollution, water pollution, energy sustainability, pollution and landscape conservation (oceans, mountains, rivers, lakes, etc.), and climate change. In the questionnaire, a very knowledgeable response was given a value of 5, a little knowledge response was marked 4, not very knowledgeable was equal to 3, not very knowledgeable was equal to 2, and no knowledge was valued as 1. Knowledge level, considered an independent variable in this study, was calculated as the aggregated unweighted average of the responses to these ten factors. |

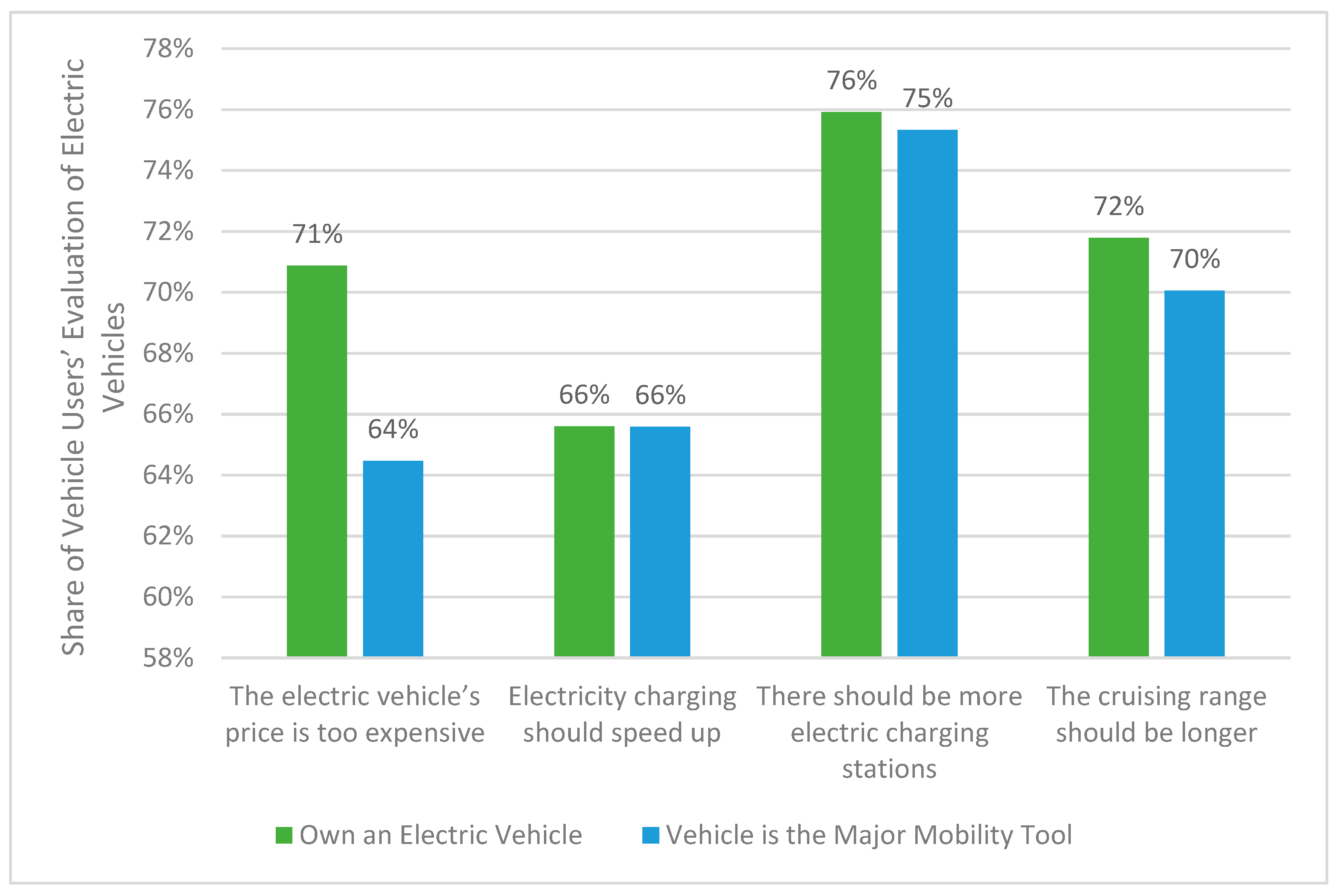

| High price of electric vehicles | “Electric vehicles are currently priced high, considering their present usage and potential future improvements.” (agree = 3, neither agree nor disagree = 2, disagree = 1) |

| Plan to purchase a fossil fuel vehicle | A dummy variable that equals one if the individual plans to plan to purchase a fossil fuel vehicle |

| Plan to purchase an electric vehicle | A dummy variable that equals one if the individual plans to purchase an electric vehicle |

| Plan to purchase a hydrogen vehicle | A dummy variable that equals one if the individual plans to purchase a hydrogen vehicle. |

| Slow charging speed | “the slow charging speed should be improved regarding the current usage of electric vehicles and potential future improvements.” (agree = 3, neither agree nor disagree = 2, disagree = 1) |

| Extensive charging spots | “extensive charging spots concerning the current usage of electric vehicles and potential future improvements.” (agree = 3, neither agree nor disagree = 2, disagree = 1) |

| Long cruising range | “long cruising range concerning the current usage of electric vehicles and potential future improvements.” (agree = 3, neither agree nor disagree = 2, disagree = 1) |

| Altruistic behavior (donations) | The altruistic behavior of individuals based on their donation activity was a dummy variable, meaning that if a respondent had donated some of their income to natural environment conservation or social and government programs, a value of 1 was adjudged, or 0 otherwise. |

| Control variables | |

| Age | Individual’s age |

| Years of schooling | Individual’s total years of education from primary school through their highest level of completed education. |

| Single household | Takes the value of one if the household is a single household and zero otherwise. |

| Married couple/partner-only household | Takes the value of one if the household is a married couple/partner-only household and zero otherwise. |

| Two-generation (parent + child) household | Takes the value of one if the household is a 2-generation (parent + child) household and zero otherwise. |

| Three-generation (grandparent + parent + child) household | Takes the value of one if the household is a 3-generation (grandparent + parent + child) household and zero otherwise. |

| Four- or more-generation households | Takes the value of one if the household is a 4- or more-generation household and zero otherwise. |

| Others (boarding house, households including non-relatives, etc.) | Takes the value of one if the household is another type of household (boarding house, households including non-relatives, etc.) and zero otherwise. |

| Family size | Number of household members in a family |

| Occupation | Represented by a set of dummy variables, including dummies for full-time employee, part-time employee, company owner, government employee/civil servant, self-employed, other occupation types, and unemployed. |

| (1) | (2) | |

|---|---|---|

| Variables | Electric Vehicle | Fossil Fuel Vehicle |

| ME. (S.E.) | ME. (S.E.) | |

| High price of electric vehicles | −0.009 *** | −0.097 *** |

| (0.003) | (0.010) | |

| Plan to purchase a fossil fuel vehicle | −0.009 ** | 0.339 *** |

| (0.004) | (0.020) | |

| Plan to purchase an electric vehicle | 0.044 *** | −0.041 * |

| (0.004) | (0.023) | |

| Plan to purchase a hydrogen vehicle | 0.031 *** | −0.088 *** |

| (0.006) | (0.034) | |

| Slow charging speed | 0.001 | −0.007 |

| (0.004) | (0.013) | |

| Extensive charging spots | 0.001 | −0.098 *** |

| (0.004) | (0.014) | |

| Long cruising range | −0.002 | −0.046 *** |

| (0.004) | (0.012) | |

| Knowledge of natural environmental issues | 0.011 *** | −0.015 ** |

| (0.002) | (0.007) | |

| Altruistic behavior (donations) | 0.008 ** | −0.037 *** |

| (0.003) | (0.012) | |

| Age | −0.000 *** | 0.002 *** |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| Years of schooling | −0.001 | 0.004 * |

| (0.001) | (0.002) | |

| Single household (Ref.) | ||

| Married couple/Partner-only household | −0.005 | 0.151 *** |

| (0.005) | (0.016) | |

| 2-generation (parent + child) household | −0.010 * | 0.159 *** |

| (0.005) | (0.021) | |

| 3-generation (grandparent + parent + child) household | −0.010 | 0.189 *** |

| (0.007) | (0.028) | |

| 4- or more-generation households | −0.033 *** | 0.104 *** |

| (0.010) | (0.039) | |

| Others (boarding house, households including non-relatives, etc.) | −0.000 | 0.029 |

| (0.012) | (0.057) | |

| Family size | 0.001 | 0.018 ** |

| (0.002) | (0.008) | |

| LR chi2(31) | 433.65 | 3098.40 |

| Prob > chi2 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.1210 | 0.2383 |

| Log likelihood | −1575.383 | −4952.08 |

| Observations | 10,000 | 10,000 |

| (a) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | |||

| Variables | Electric Vehicle | Fossil Fuel Vehicle | Electric Vehicle | Fossil Fuel Vehicle | Electric Vehicle | Fossil Fuel Vehicle | Electric Vehicle | Fossil Fuel Vehicle | ||

| ME | ME | ME | ME | ME | ME | ME | ME | |||

| High price of electric vehicles | −0.017 *** | −0.012 * | −0.005 | −0.071 *** | −0.006 | −0.095 *** | −0.014 ** | −0.120 *** | ||

| (0.006) | (0.007) | (0.005) | (0.017) | (0.004) | (0.013) | (0.006) | (0.020) | |||

| Slow charging speed | 0.011 | −0.003 | −0.005 | 0.008 | 0.008 | −0.012 | 0.001 | 0.008 | ||

| (0.007) | (0.010) | (0.006) | (0.021) | (0.005) | (0.019) | (0.007) | (0.028) | |||

| Extensive charging spots | 0.008 | −0.037 *** | 0.012 * | −0.109 *** | −0.016 ** | −0.065 *** | −0.001 | −0.109 *** | ||

| (0.009) | (0.011) | (0.007) | (0.023) | (0.007) | (0.021) | (0.009) | (0.031) | |||

| Long cruising range | −0.007 | −0.010 | −0.006 | −0.040 * | 0.007 | −0.028 | −0.003 | −0.059 ** | ||

| (0.007) | (0.009) | (0.006) | (0.021) | (0.005) | (0.018) | (0.007) | (0.025) | |||

| Plan to purchase fossil fuel vehicle | −0.022 *** | 0.118 *** | −0.005 | 0.322 *** | −0.011 * | 0.307 *** | −0.008 | 0.531 *** | ||

| (0.008) | (0.014) | (0.007) | (0.031) | (0.006) | (0.027) | (0.010) | (0.072) | |||

| Plan to purchase electric vehicle | 0.053 *** | −0.041 *** | 0.048 *** | −0.043 | 0.040 *** | −0.032 | 0.035 *** | 0.019 | ||

| (0.007) | (0.013) | (0.008) | (0.039) | (0.006) | (0.033) | (0.007) | (0.046) | |||

| Plan to purchase hydrogen vehicle | 0.042 *** | −0.072 *** | 0.037 *** | −0.051 | 0.026 *** | −0.132 *** | 0.027 *** | −0.070 | ||

| (0.011) | (0.019) | (0.010) | (0.060) | (0.009) | (0.050) | (0.010) | (0.067) | |||

| Knowledge of natural environmental issues | 0.014 *** | −0.008 | 0.015 *** | −0.015 | 0.009 *** | −0.002 | 0.006 | −0.007 | ||

| (0.004) | (0.005) | (0.004) | (0.013) | (0.003) | (0.010) | (0.004) | (0.014) | |||

| LR chi2(31) | 178.63 | 293.83 | 222.52 | 831.08 | 167.30 | 1172.98 | 104.62 | 1177.29 | ||

| Prob > chi2 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||

| Pseudo R2 | 0.0866 | 0.0905 | 0.1716 | 0.2041 | 0.1308 | 0.2508 | 0.1055 | 0.2895 | ||

| Log likelihood | −942.15 | −1476.21 | −536.9124 | −1620.7604 | −555.79324 | −1752.03 | −443.56 | −1444.498 | ||

| Household type | Primary mobility tool | Young | Middle | Old | ||||||

| Observations | 4762 | 4762 | 2964 | 2964 | 3911 | 3911 | 3125 | 3125 | ||

| (b) | ||||||||||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | (10) | |

| Variables | Electric vehicle | Fossil fuel vehicle | Electric vehicle | Fossil fuel vehicle | Electric vehicle | Fossil fuel vehicle | Electric vehicle | Fossil fuel vehicle | Electric vehicle | Fossil fuel vehicle |

| ME | ME | ME | ME | ME | ME | ME | ME | ME | ME | |

| High price of electric vehicles | 0.001 | −0.137 *** | −0.017 ** | −0.093 *** | −0.010 | −0.084 *** | −0.002 | −0.057 *** | −0.018 | −0.041 ** |

| (0.003) | (0.022) | (0.008) | (0.031) | (0.006) | (0.015) | (0.040) | (0.021) | (0.013) | (0.020) | |

| Slow charging speed | −0.007 | −0.026 | −0.001 | −0.023 | −0.000 | 0.025 | 0.004 | −0.048 * | −0.006 | −0.004 |

| (0.004) | (0.031) | (0.010) | (0.042) | (0.007) | (0.021) | (0.077) | (0.027) | (0.013) | (0.025) | |

| Extensive charging spots | 0.004 | −0.106 *** | −0.012 | −0.165 *** | 0.005 | −0.085 *** | 0.012 | −0.017 | 0.012 | −0.059 ** |

| (0.004) | (0.036) | (0.011) | (0.046) | (0.009) | (0.023) | (0.223) | (0.031) | (0.018) | (0.027) | |

| Long cruising range | −0.001 | −0.031 | 0.021 ** | −0.043 | −0.003 | −0.051 *** | −0.027 | −0.044 | −0.021 | −0.028 |

| (0.004) | (0.030) | (0.009) | (0.042) | (0.008) | (0.019) | (0.503) | (0.028) | (0.015) | (0.023) | |

| Plan to purchase fossil fuel vehicle | −0.005 | 0.399 *** | −0.008 | 0.408 *** | −0.023 ** | 0.294 *** | 0.000 | 0.143 *** | −0.014 | 0.194 *** |

| (0.004) | (0.047) | (0.014) | (0.069) | (0.009) | (0.031) | (0.012) | (0.038) | (0.014) | (0.038) | |

| Plan to purchase electric vehicle | 0.021 *** | −0.085 | 0.043 *** | −0.028 | 0.042 *** | 0.007 | 0.033 | −0.049 | 0.077 *** | −0.093 ** |

| (0.005) | (0.058) | (0.013) | (0.074) | (0.008) | (0.035) | (0.611) | (0.044) | (0.016) | (0.039) | |

| Plan to purchase hydrogen vehicle | 0.008 | 0.049 | 0.015 | −0.150 | 0.039 *** | −0.113 ** | 0.038 | −0.122 * | 0.053 ** | −0.025 |

| (0.005) | (0.082) | (0.017) | (0.110) | (0.011) | (0.050) | (0.707) | (0.071) | (0.025) | (0.068) | |

| Knowledge of natural environmental issues | 0.008 *** | 0.007 | 0.014 ** | −0.034 | 0.009 ** | −0.017 | 0.008 | 0.006 | 0.019 ** | −0.016 |

| (0.002) | (0.018) | (0.006) | (0.025) | (0.004) | (0.011) | (0.144) | (0.016) | (0.007) | (0.013) | |

| LR chi2(31) | 167.82 | 904.54 | 79.19 | 381.99 | 125.00 | 749.67 | 49.98 | 250.82 | 105.28 | 227.29 |

| Prob > chi2 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.0091 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.2732 | 0.2810 | 0.1857 | 0.2605 | 0.1162 | 0.2129 | 0.1065 | 0.2010 | 0.1987 | 0.2231 |

| Log likelihood | −223.199 | −1157.35 | −173.61 | −542.086 | −475.26 | −1385.67 | −209.63 | −498.66 | −212.24 | −395.72 |

| Region | Tokyo 23 wards and ordinance-designated cities | Cities with population of 500,000 or more | Population of 100,000 or more/less than 500,000 | Population 50,000 or more/less than 100,000 | Population less than 50,000 | |||||

| Observations | 2323 | 2323 | 1004 | 1072 | 2921 | 2970 | 1132 | 1158 | 1048 | 1062 |

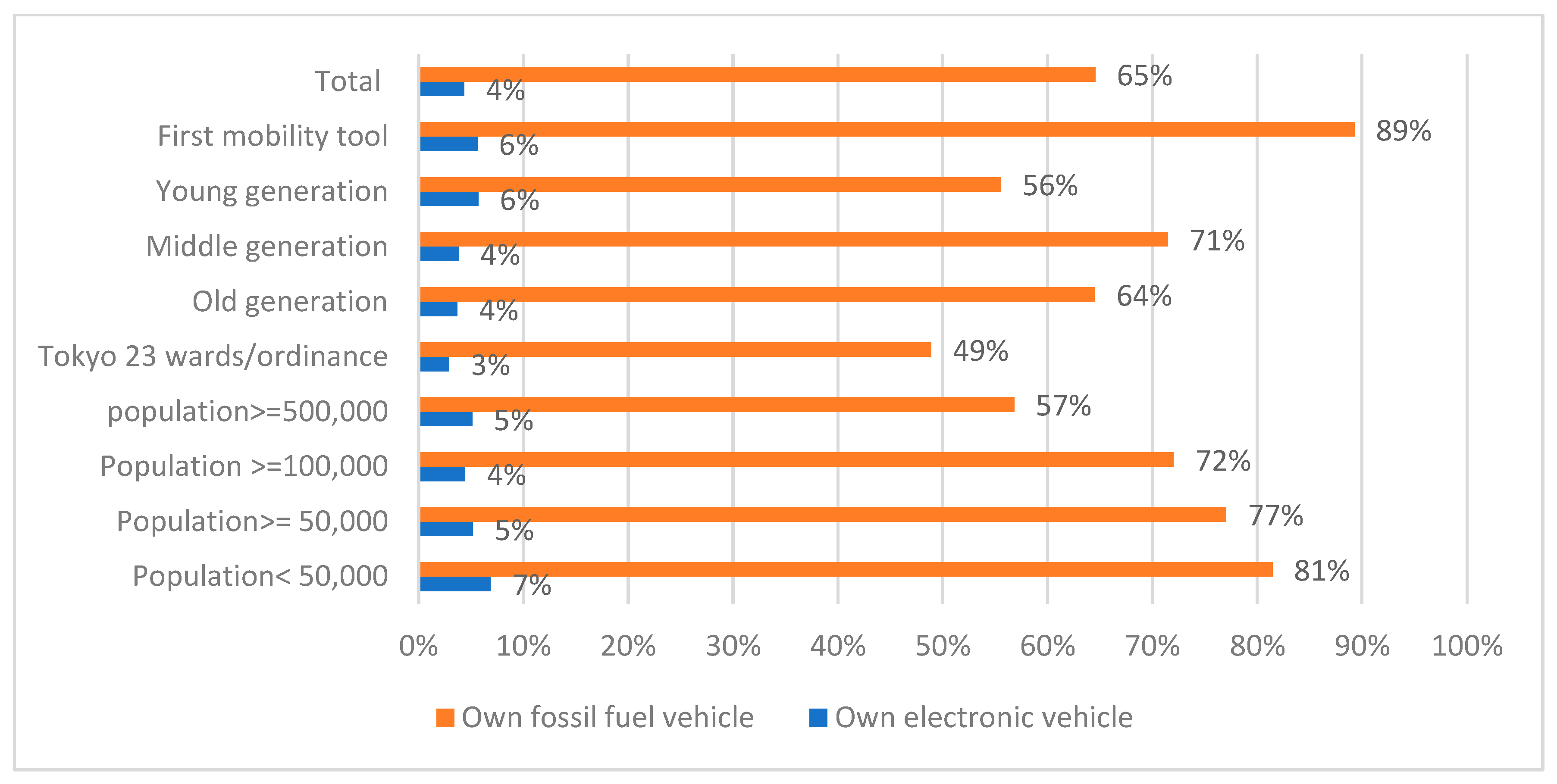

| Variable | Mean |

|---|---|

| Have vehicle | 77% |

| Have fossil fuel vehicle (total) | 65% |

| Have electric vehicle (total) | 4% |

| Vehicle is the primary mobility tool (obs = 4762) | |

| Own electric vehicle and vehicle is the primary mobility tool | 6% |

| Own fossil fuel vehicle and vehicle is the primary mobility tool | 89% |

| Have fossil fuel vehicle (vehicle is the primary mobility tool and have a plan to purchase their next vehicle) (obs = 1190) | |

| Plan to purchase fossil fuel vehicle | 75% |

| Plan to purchase electric vehicle | 29% |

| Plan to purchase hydrogen vehicle | 8% |

| Have electric vehicle (vehicle is the primary mobility tool and have a plan to purchase the next vehicle) (obs = 106) | |

| Plan to purchase fossil fuel vehicle | 38% |

| Plan to purchase electric vehicle | 73% |

| Plan to purchase hydrogen vehicle | 25% |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Life Satisfaction | Happiness | Stress | Depression | Joy | Anxiety | Anger |

| Coeff. | Coeff. | Coeff. | Coeff. | Coeff. | Coeff. | Coeff. | |

| Owning a fossil fuel vehicle | −0.001 | 0.093 | 0.378 *** | 0.104 | 0.271 *** | 0.190 ** | 0.243 *** |

| (0.088) | (0.095) | (0.091) | (0.089) | (0.094) | (0.090) | (0.090) | |

| Owning an electric vehicle | 0.478 *** | 0.540 *** | −0.060 | 0.043 | 0.204 * | 0.028 | 0.164 |

| (0.117) | (0.132) | (0.122) | (0.119) | (0.124) | (0.120) | (0.119) | |

| Knowledge of natural environmental issues | 0.302 *** | 0.355 *** | −0.119 *** | −0.113 *** | 0.277 *** | −0.162 *** | −0.065 * |

| (0.036) | (0.040) | (0.037) | (0.036) | (0.038) | (0.037) | (0.037) | |

| Donation activities | 0.355 *** | 0.301 *** | −0.109 * | −0.061 | 0.165 *** | −0.020 | −0.091 |

| (0.057) | (0.065) | (0.060) | (0.059) | (0.061) | (0.059) | (0.060) | |

| Age | 0.004 * | 0.005 ** | −0.024 *** | −0.020 *** | −0.015 *** | −0.025 *** | −0.028 *** |

| (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.002) | |

| Vehicle is the major mobility tool | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Control variables | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| LR chi2(30) | 444.02 | 403.76 | 625.38 | 271.59 | 296.31 | 385.97 | 536.89 |

| Prob > chi2 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.022 | 0.0348 | 0.0523 | 0.0216 | 0.0262 | 0.0313 | 0.045 |

| Log likelihood | −9430.5016 | −5469.5104 | −5691.0904 | −6179.0633 | −5371.2473 | −5947.7304 | −5704.4888 |

| Observations | 4762 | 4762 | 4762 | 4762 | 4762 | 4762 | 4762 |

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electric Vehicle | Fossil Fuel Vehicle | |||||

| ME | Coeff. | ME | Coeff. | VIF | 1/VIF | |

| High price of electric vehicles | −0.009 *** | −0.009 ** | −0.097 *** | −0.084 *** | 2.56 | 0.390122 |

| (0.003) | (0.004) | (0.009) | (0.008) | |||

| Plan to purchase a fossil fuel vehicle | −0.013 ** | −0.015 ** | 0.314 *** | 0.210 *** | 1.06 | 0.943005 |

| (0.005) | (0.006) | (0.018) | (0.012) | |||

| Plan to purchase an electric vehicle | 0.053 *** | 0.133 *** | −0.039 * | −0.028 | 1.12 | 0.892795 |

| (0.005) | (0.008) | (0.022) | (0.017) | |||

| Plan to purchase a hydrogen vehicle | 0.041 *** | 0.123 *** | −0.084 ** | −0.064 ** | 1.09 | 0.921461 |

| (0.007) | (0.013) | (0.033) | (0.026) | |||

| Slow charging speed | 0.001 | 0.002 | −0.006 | −0.005 | 4.02 | 0.248457 |

| (0.004) | (0.005) | (0.012) | (0.010) | |||

| Extensive charging spots | 0.000 | 0.002 | −0.099 *** | −0.096 *** | 5.09 | 0.196562 |

| (0.005) | (0.006) | (0.014) | (0.012) | |||

| Long cruising range | −0.002 | −0.002 | −0.045 *** | −0.043 *** | 3.85 | 0.260051 |

| (0.004) | (0.005) | (0.012) | (0.010) | |||

| Knowledge of natural environmental issues | 0.011 *** | 0.014 *** | −0.015 ** | −0.012 ** | 1.14 | 0.879388 |

| (0.002) | (0.003) | (0.007) | (0.005) | |||

| Altruistic behavior (donations) | 0.013 *** | 0.016 *** | −0.036 *** | −0.026 *** | 1.09 | 0.913547 |

| (0.004) | (0.004) | (0.011) | (0.009) | |||

| Age | −0.000 *** | −0.001 *** | 0.002 *** | 0.001 *** | 1.81 | 0.551096 |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | |||

| Years of schooling | −0.001 | −0.001 | 0.003 | 0.002 | 1.11 | 0.900812 |

| (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.002) | (0.002) | |||

| Single household (Ref.) | ||||||

| Married couple/partner-only household | −0.004 | −0.007 | 0.148 *** | 0.137 *** | 2.1 | 0.47633 |

| (0.005) | (0.006) | (0.015) | (0.012) | |||

| Two-generation (parent + child) household | −0.011 * | −0.016 ** | 0.154 *** | 0.139 *** | 2.53 | 0.395505 |

| (0.006) | (0.008) | (0.021) | (0.016) | |||

| Three-generation (grandparent + parent + child) household | −0.011 | −0.014 | 0.180 *** | 0.155 *** | 3.07 | 0.325233 |

| (0.007) | (0.010) | (0.028) | (0.021) | |||

| Four- or more-generation households | −0.033 *** | −0.046 *** | 0.104 *** | 0.095 *** | 2.45 | 0.408624 |

| (0.011) | (0.014) | (0.038) | (0.029) | |||

| Others (boarding house, households including non-relatives, etc.) | 0.001 | 0.007 | 0.025 | 0.032 | 1.71 | 0.584606 |

| (0.014) | (0.021) | (0.056) | (0.043) | |||

| Family size | 0.002 | 0.003 | 0.019 ** | 0.016 ** | 4.18 | 0.23927 |

| (0.002) | (0.003) | (0.008) | (0.006) | |||

| Model | Probit model | Linear probability model | Probit model | Linear probability model | VIF | 1/VIF |

| Observations | 10,000 | 10,000 | 10,000 | 10,000 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Piao, X.; Nasuda, A.; Li, S. Electric Vehicle Adoption: Japanese Consumer Attitudes, Inter-Vehicle Transitions, and Effects on Well-Being. Sustainability 2026, 18, 195. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010195

Piao X, Nasuda A, Li S. Electric Vehicle Adoption: Japanese Consumer Attitudes, Inter-Vehicle Transitions, and Effects on Well-Being. Sustainability. 2026; 18(1):195. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010195

Chicago/Turabian StylePiao, Xiangdan, Akiko Nasuda, and Shenghua Li. 2026. "Electric Vehicle Adoption: Japanese Consumer Attitudes, Inter-Vehicle Transitions, and Effects on Well-Being" Sustainability 18, no. 1: 195. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010195

APA StylePiao, X., Nasuda, A., & Li, S. (2026). Electric Vehicle Adoption: Japanese Consumer Attitudes, Inter-Vehicle Transitions, and Effects on Well-Being. Sustainability, 18(1), 195. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010195