White Hydrogen and the Future of Power-to-X: A Policy Reassessment of Europe’s Green Hydrogen Strategy

Abstract

1. Introduction

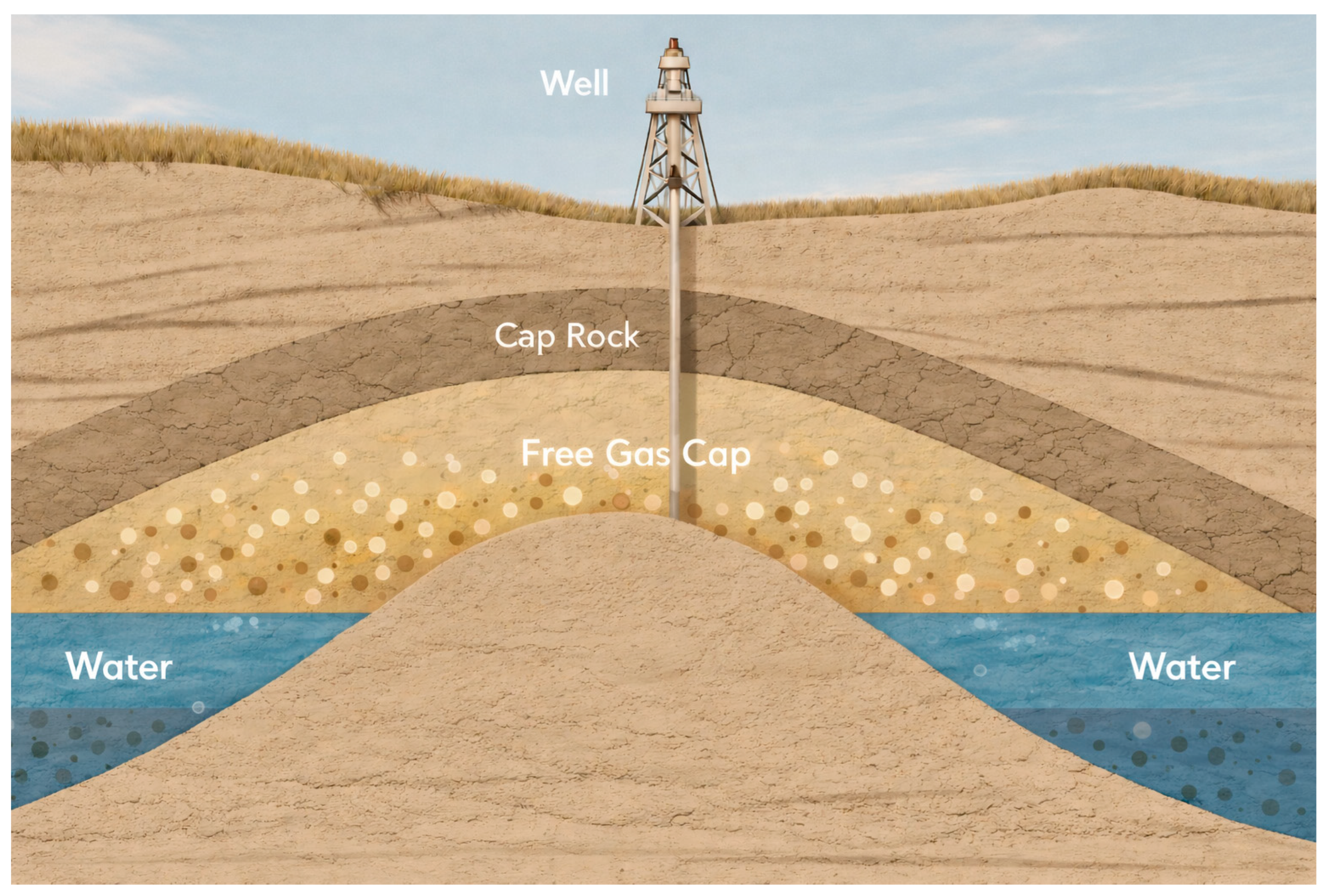

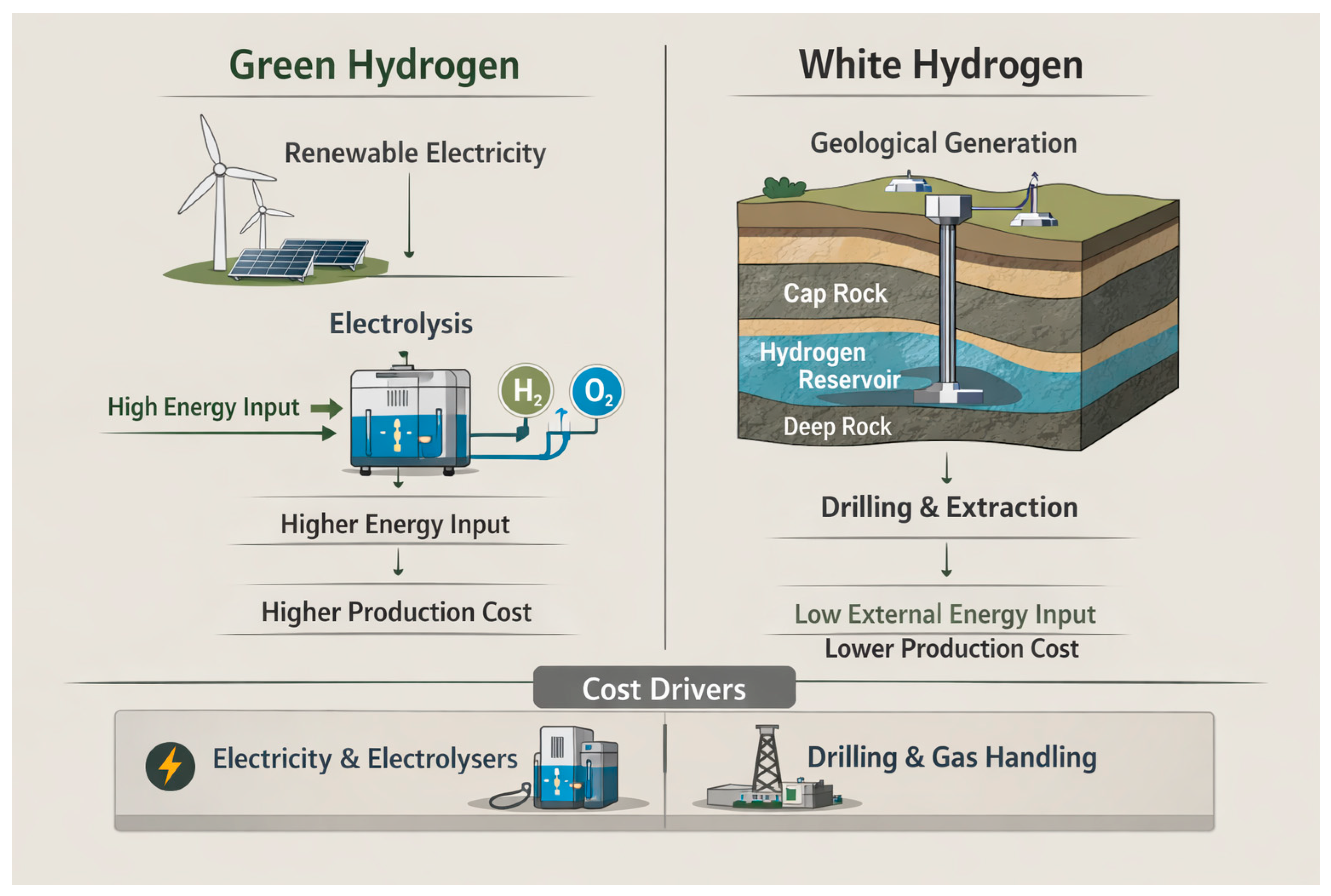

2. Understanding White Hydrogen vs. Green Hydrogen

3. European Natural Hydrogen Discoveries and Reserves

- Lorraine, France (2023): In May 2023, the French company La Française d’Énergie (FDE) detected substantial native hydrogen while checking for firedamp in abandoned coal mines of the Lorraine region [5,6]. Subsequent analysis suggests the Lorraine basin could contain up to ~46 million tonnes of hydrogen [5]—an astonishing figure equivalent to roughly half of current global annual hydrogen production [5]. Some researchers have even speculated that the resource might be larger if deeper stratigraphy is considered, possibly “up to 250 million tonnes” of H2 gas in place [10]. If confirmed, this would be by far the largest natural hydrogen deposit ever identified. The hydrogen concentration in drill samples was around 15–20% at 1250 m depth and appeared to increase with depth [9], indicating a deep source. The discovery, described as a “game changer,” has spurred follow-up drilling plans: FDE aims to drill deeper in 2024–2025 to delineate the deposit, with hopes of beginning pilot production before 2028 [10]. French authorities have responded by updating mining regulations to include hydrogen, ensuring a legal pathway for exploration and eventual exploitation [1,8].

- Aragon, Spain (2023): In northern Spain, at the foothills of the Pyrenees, an Anglo-Spanish startup called Helios Aragón announced access to a “giant” natural hydrogen reservoir and is preparing Europe’s first dedicated hydrogen well [8]. The site near Monzón, Huesca, was originally identified from a 1960s exploratory well that found hydrogen traces (Figure 1); new surveys showed strong hydrogen readings, prompting Helios to plan a 3850 m deep exploratory drill in 2024 [8]. If the deposit is as expected, the company projects commercial extraction by 2028, ramping up to 55,000 tonnes of H2 per year (roughly 10% of Spain’s current hydrogen usage) with a 20-year production horizon [8]. Helios estimates a production cost of ~€0.75/kg, claiming it could deliver “the cheapest H2 in the world” from this site [8]. Notably, the main hurdle so far has been regulatory: Spain’s current law (as of 2023) forbids hydrocarbon exploration, which, by a strict reading, includes pure hydrogen gas (despite hydrogen’s different nature) [8]. The Aragon regional government has declared the project of “regional interest,” and Spain is now moving to amend mining laws to accommodate natural hydrogen extraction, following France’s lead [1,8]. Helios’s initiative has, therefore, become a test case for how quickly Europe can adapt policy to this new resource.

- Other European Occurrences: Beyond these two flagships, evidence of white hydrogen has surfaced in several other locations. In Germany, a 2024 field study in northern Bavaria detected surprisingly high hydrogen in soil gas (up to 1000 ppm H2)—a “sensational” reading indicating a likely subsurface source [7]. German geologists believe commercially viable deposits could exist in parts of Bavaria and elsewhere, though systematic exploration is only just beginning [7]. In Serbia, geologists have likewise pointed to promising geology; Serbia is often noted in studies as a region where natural hydrogen might be found, and initiatives are reportedly underway to investigate it [9]. Even outside the EU, nearby Switzerland joined the hunt in 2023, finding natural hydrogen seeps in the Alps (Graubünden canton) and launching further probes in Valais [2]. These early signs suggest that Europe’s geology could contain multiple hydrogen-rich sites. Mapping of “hydrogen-prone” structures (such as ancient cratons, iron-rich minerals, or deep faults) is now accelerating, driven by startups (e.g., France’s Mantle8, Germany’s H2 Natural, etc.) and research projects aiming to identify where white hydrogen might accumulate. In short, while France and Spain currently lead with confirmed large finds, the resource could be more widespread, and European governments are starting to pay attention.

4. Economic and Environmental Implications of White Hydrogen

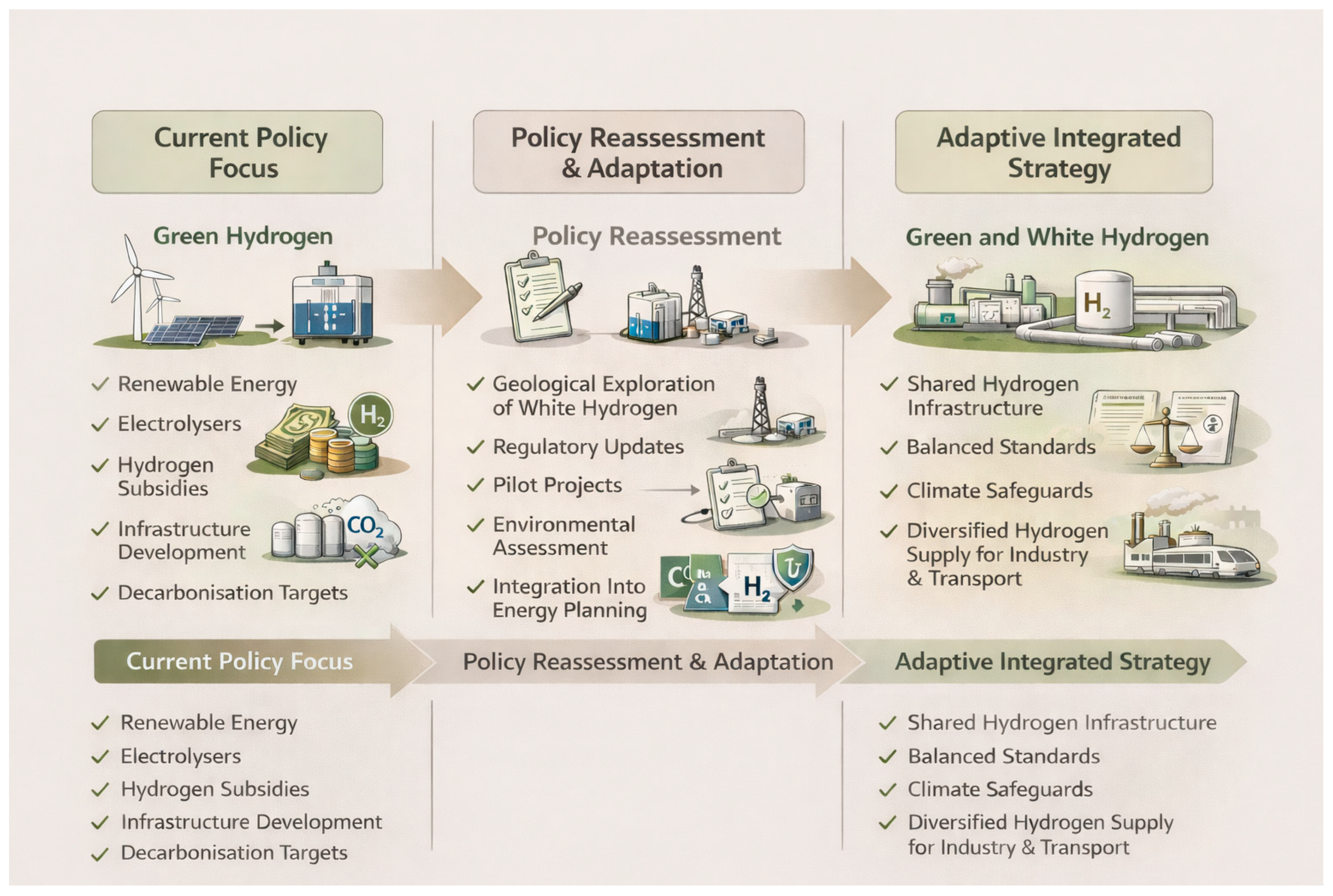

5. Policy Implications: Reassessing Europe’s Hydrogen Strategy

- Incorporating White H2 into Planning: Acknowledge natural hydrogen in EU strategic documents and conduct a formal study on its potential. For instance, the EU could task geological agencies or a body like the JRC (Joint Research Centre) to evaluate Europe’s white hydrogen resource base and its possible contribution to the 2030–2050 climate targets. This would put data behind the hype and inform targets accordingly. If white hydrogen can realistically supply, say, 1–2 million tonnes by 2035, that could be factored into infrastructure planning.

- Developing Regulatory Frameworks: Create guidelines for licensing, environmental assessment, and safety for white hydrogen drilling projects. As noted, current laws in many EU countries did not anticipate hydrogen extraction, leading to legal grey areas or outright prohibitions (by analogies to hydrocarbons) [8]. The EU could facilitate best-practice sharing or even propose amendments to relevant directives (such as the Mining Waste Directive or fuel quality regulations) to cover geologic hydrogen. Ensuring strict environmental safeguards—e.g., leak detection standards, water protection, methane management—will be critical to address the valid concerns raised by environmental groups [1]. This can prevent a “wild west” of hydrogen drilling and align the industry with Europe’s sustainability values.

- Aligning Incentives and Definitions: Currently, EU hydrogen incentives (such as carbon contracts for difference, the Hydrogen Bank auctions, etc.) are geared toward green hydrogen. The EU might consider extending some form of support or at least recognition to “ultra-low carbon” hydrogen, that is, hydrogen whose lifecycle greenhouse gas emissions are substantially lower than those of conventional fossil-based hydrogen, as long as it meets stringent GHG criteria (e.g., 70%+ emissions savings over fossil, which white H2 easily could [3]). This could be done by tweaking the taxonomy or delegated acts; for example, counting white hydrogen as a renewable fuel of non-biological origin (RFNBO) if it meets additionality and sustainability requirements. At minimum, clarity that using white hydrogen will count toward industrial decarbonization targets (for steel, ammonia, etc.) would remove uncertainty for investors. One might imagine, for instance, a steel mill being allowed to offtake white hydrogen and have it qualify under the same quotas that mandate a share of renewable hydrogen use in industry [3].

- Avoiding Stranded Assets: The EU’s hydrogen strategy should also guard against the risk of stranded assets or long-term economic inefficiencies. From a technical perspective, hydrogen molecules are chemically identical regardless of whether they originate from electrolysis or geological sources. Infrastructure compatibility is, therefore, determined not by origin, but by factors such as gas purity, pressure management, material integrity, and leakage control. This implies that, provided harmonised technical standards are enforced, hydrogen infrastructure such as pipelines and storage facilities can, in principle, accommodate hydrogen from multiple production pathways. Designing infrastructure with this flexibility in mind would reduce the risk of lock-in to high-cost production routes and allow Europe to adapt its hydrogen supply mix as new evidence on white hydrogen availability emerges. The worst-case scenario would be Europe locking itself into very high-cost hydrogen production (needing perpetual subsidies to compete) while a cheaper resource lies untapped. A prudent policy will hedge bets: continue scaling green H2 in the near term (since we know we need it), while aggressively researching white H2 so that it can complement or substitute when ready.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Haas, J.; Gnant, E. Geogenic Hydrogen: Exploring a New Frontier of the Energy Transition. Available online: https://www.boell.de/en/2024/11/22/geogenic-hydrogen-exploring-new-frontier-energy-transition (accessed on 26 October 2025).

- Symons, A. What is ‘White Hydrogen’? The Pros and Cons of Europe’s Latest Clean Energy Source. Available online: https://www.euronews.com/green/2023/11/05/what-is-white-hydrogen-the-pros-and-cons-of-europes-latest-clean-energy-source (accessed on 26 October 2025).

- European, C. Hydrogen (EU Energy System). Available online: https://energy.ec.europa.eu/topics/eus-energy-system/hydrogen_en (accessed on 26 October 2025).

- Carnevali, A. Scientists are Shocked by the Discovery of White Hydrogen in France: Could it be Europe’s Fuel? Available online: https://www.euronews.com/next/2024/02/07/scientists-are-shocked-by-the-discovery-of-white-hydrogen-in-france-could-it-be-europes-fu (accessed on 26 October 2025).

- Gold, H. Natural Hydrogen Find in France. Available online: https://www.goldhydrogen.com.au/updates/natural-hydrogen-find-in-france/ (accessed on 26 October 2025).

- Hydrogen, E. Excitement Grows About ‘Natural H₂’ as Huge Reserves Found in France. Available online: https://hydrogeneurope.eu/excitement-grows-about-natural-h2-as-huge-reserves-found-in-france/ (accessed on 26 October 2025).

- Friedrich-Alexander-Universität, E.-N. Natural hydrogen—The Treasure Hidden Underground. Available online: https://www.fau.eu/2024/11/news/natural-hydrogen-the-treasure-hidden-underground/ (accessed on 26 October 2025).

- Hydrogen, C. Spain—Aragon Launches Exploration in Huesca for a ‘Treasure’ of Natural Hydrogen. Available online: https://hydrogen-central.com/spain-aragon-launches-exploration-in-huesca-treasure-natural-hydrogen/ (accessed on 26 October 2025).

- Vujasin, M. White Hydrogen: Sustainable Energy from Depths of Earth. Available online: https://balkangreenenergynews.com/white-hydrogen-sustainable-energy-from-depths-of-earth/ (accessed on 26 October 2025).

- Meza, E.; Wehrmann, B. Natural Hydrogen Discoveries near French-German Border Fuel Hopes for H₂ Abundance. Available online: https://www.cleanenergywire.org/news/natural-hydrogen-discoveries-near-french-german-border-fuel-hopes-h2-abundance (accessed on 26 October 2025).

- Parkes, R. Massive Underground Reservoir of Natural Hydrogen in Spain ‘Could Deliver the Cheapest H2 in the World’. Available online: https://www.hydrogeninsight.com/innovation/massive-underground-reservoir-of-natural-hydrogen-in-spain-could-deliver-the-cheapest-h2-in-the-world/2-1-1431515 (accessed on 26 October 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Jørgensen, B.N.; Ma, Z.G. White Hydrogen and the Future of Power-to-X: A Policy Reassessment of Europe’s Green Hydrogen Strategy. Sustainability 2026, 18, 190. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010190

Jørgensen BN, Ma ZG. White Hydrogen and the Future of Power-to-X: A Policy Reassessment of Europe’s Green Hydrogen Strategy. Sustainability. 2026; 18(1):190. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010190

Chicago/Turabian StyleJørgensen, Bo Nørregaard, and Zheng Grace Ma. 2026. "White Hydrogen and the Future of Power-to-X: A Policy Reassessment of Europe’s Green Hydrogen Strategy" Sustainability 18, no. 1: 190. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010190

APA StyleJørgensen, B. N., & Ma, Z. G. (2026). White Hydrogen and the Future of Power-to-X: A Policy Reassessment of Europe’s Green Hydrogen Strategy. Sustainability, 18(1), 190. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010190