Abstract

Lignocellulosic residues are increasingly explored as alternatives to wood in particleboard production, fostering sustainability within the circular economy. Beyond these, non-lignocellulosic wastes such as plastics are gaining attention for enhancing panel durability and performance. This study evaluates waste high-density polyethylene (HDPE) as a partial substitute for adhesive resin in sugarcane bagasse-based medium-density particleboards. The objective was to valorize agricultural and plastic residues while reducing reliance on petroleum-based resins and associated environmental impacts. Panels (750 kg/m3) were produced with two face layers of sugarcane bagasse and a core layer combining bagasse and HDPE, bonded with castor oil-based polyurethane resin at 8% and 12% contents. Physical and mechanical performance was assessed against national and international standards, complemented by natural and accelerated weathering tests. A comparative life cycle assessment (LCA) was conducted to benchmark hybrid panels against conventional particleboards. Results showed that incorporating HDPE allows for resin reduction without compromising performance, meeting standard requirements for several applications. The LCA indicated lower environmental burdens in 8 of 10 impact categories for hybrid panels relative to conventional ones, underscoring their potential to reduce fossil resource use and emissions. The findings demonstrate that integrating waste plastics into particleboard production not only improves resource efficiency but also delivers tangible environmental benefits. This approach offers a scalable pathway for advancing sustainable materials, closing waste loops, and supporting circular economy practices in the wood-based panel industry.

1. Introduction

Currently, several industrial and agribusiness sectors face significant challenges regarding the proper disposal of waste generated throughout production, including the reconstituted wood panel industry [1]. These panels are composites manufactured from wood in various forms, such as particles and fibers, bonded with adhesive resins and consolidated under pressure and temperature, offering a viable alternative to solid wood [1,2].

Wood-based panels have gained increasing importance in the furniture and construction sectors, with notable relevance in the Brazilian economy. Brazil ranks as the eighth-largest producer worldwide, with an annual output of 8.5 million m3 in 2022, contributing significantly to employment and income generation [1,3,4,5,6].

Despite the broad product range, panel production largely relies on lignocellulosic feedstock from Eucalyptus and Pinus species. This dependence has raised concerns about resource diversification to reduce pressure on forest resources and promote sustainable production with improved durability [1,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10].

A strategic alternative lies in using lignocellulosic residues, particularly agro-industrial waste, as low-cost, environmentally friendly raw materials. This approach mitigates virgin wood extraction, reduces environmental burdens from agricultural residue disposal, and fosters circular economy practices. Moreover, coupling such residues with bio-based resins, such as castor oil-based polyurethane resin, enhances sustainability [4,8,10,11,12,13,14,15,16].

Sugarcane bagasse has emerged as a promising alternative in particleboard research. As the world’s largest sugarcane producer, Brazil harvested about 710 million tons in 2023/2024, generating 250–300 kg of bagasse per ton—nearly one-third of total production [11,17]. Besides its abundant availability, its lignocellulosic composition and density are comparable to those of wood, thereby making it suitable for panel production [13]. Studies have confirmed its potential, whether used alone or combined with other fibers, exhibiting satisfactory mechanical performance and meeting the requirements established by the relevant panel standards. [2,8,18].

In parallel, the replacement of fossil-derived adhesives with renewable alternatives is gaining traction. Castor oil-based polyurethane resin (PU castor oil resin) demonstrates strong potential compared to formaldehyde-based adhesives, offering favorable mechanical performance, reduced toxicity, and renewable origin [4,16,18,19,20,21,22].

Recent studies have also explored hybrid panels, which combine lignocellulosic materials with polymers to enhance composite performance while providing an outlet for plastic waste recycling [5,23,24,25,26,27]. However, plastic recycling in Brazil still faces structural challenges, such as insufficient technology, inadequate working conditions in cooperatives, and inefficient processing, leading to high material losses. In 2021, nearly 177,000 tons, about 20% of the one million tons of recycled plastic, were discarded, with HDPE ranking second among recycled polymers after PET [28].

Sustainability efforts in the industrial sector increasingly rely on tools such as Life Cycle Assessment (LCA), which systematically quantify inputs and outputs, identify environmental hotspots, and support the development of more efficient and lower-impact alternatives. LCA is closely associated with circular economy principles, particularly regarding the feasibility and optimization of resource reuse [10,21,29,30]. In this context, adhesive resins remain one of the main contributors to environmental impacts of particleboard production, highlighting the need for optimization [4,19,21,29,31,32].

As noted above, several studies have evaluated the incorporation of plastic waste in the production of particleboards; however, the assessment of the potential for reducing resin content, together with the analysis of environmental impacts associated with the production of hybrid panels, still presents gaps that remain to be explored.

This study advances the field by investigating medium-density particleboards made from sugarcane bagasse reinforced with HDPE plastic waste, partially replacing PU castor oil resin. This approach not only leverages underutilized plastic residues from inefficient recycling streams but also optimizes adhesive application, reducing potential environmental burdens. Physical, mechanical, and durability properties under natural and accelerated weathering were evaluated, alongside a comparative LCA of conventional and alternative panels, to evaluate both technical feasibility and environmental performance.

2. Materials and Methods

The particle raw materials used in the production of the hybrid panels in this study were sugarcane bagasse (Saccharum officinarum) supplied by a sugar–alcohol plant and the residual high-density polyethylene plastic from the sorting of a recycling company, both located in the Pirassununga region, São Paulo (Brazil). The commercial two-component polyurethane adhesive resin based on castor oil (PU castor oil)—solvent-free (100% solids) and with mass loss only above 210 °C—was selected to agglomerate these particles. The initial characterization of the sugarcane bagasse and the residual polyethylene used in this study is available in the research conducted by Duran et al. (2025) [24], exhibiting, respectively, average densities of 1311 and 954 kg/m3.

2.1. Hybrid Panel Production

Initially, after collecting the raw materials, the sugarcane bagasse was dried in an air-circulating oven, processed in a knife mill, and sieved in a mechanical shaker, obtaining particles ranging in length from 1.0 to 4.0 mm, following the guidelines adapted from Duran et al. (2025) [24]. The waste plastic, although already sorted by the recycling company and collected as particles, underwent an additional separation stage using a sieve shaker. This supplementary procedure aimed to remove oversized particles, eliminate residual impurities such as cardboard and laminated packaging, and ensure particle size standardization within the 1.0–4.0 mm range.

Following particle preparation, particleboard manufacturing was initiated by spraying PU castor oil resin onto the particles in a planetary mixer, at resin contents of 12% and 8% relative to particle mass. The resin-coated particles were then placed into a mattress-forming mold, pre-compacted, and hot-pressed in a thermo-hydraulic press. The pressing conditions followed the methodology proposed by Duran et al. (2025) [24], applying 5 MPa of pressure for 10 min at 200 °C, a temperature that facilitated the initial melting of the waste plastic and promoted enhanced interparticle adhesion.

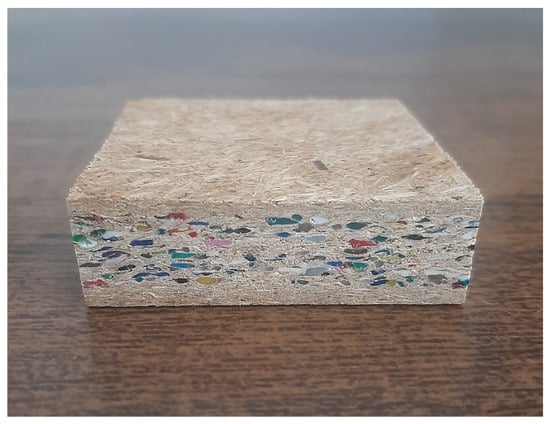

Two hybrid panels were manufactured for each resin content level, 12% resin (BP12) and 8% resin (BP8), both designed with a target density of 750 kg/m3. The resin content was reduced in order to evaluate reductions that would still allow for physical and mechanical properties compatible with established standards. Each panel was composed of three layers in a 20:60:20 mass ratio, with the face layers made exclusively of sugarcane bagasse and the core layer consisting of a mixture of bagasse and waste plastic (Figure 1). The plastic fraction accounted for 20% of the total panel mass [24], and the resin was applied proportionally to each layer. Two reference panels composed solely of sugarcane bagasse and bonded with 8% resin (B8) were produced for comparative purposes. Additional panels of all formulations were also fabricated for weathering assessments.

Figure 1.

Hybrid particleboard. Face layers composed solely of sugarcane bagasse and an inner layer composed of a combination of sugarcane bagasse and waste plastic.

All panels were produced with dimensions of 400 × 400 mm and 15 mm thickness, and subsequently conditioned in a climate-controlled chamber (20 ± 3 °C; 65 ± 5% RH) until a constant mass was achieved.

2.2. Characterization of Particleboards

The physical and mechanical properties of the panels developed in this research were evaluated according to the ASTM (American Society for Testing and Materials) D1037-12 (2020) Standard Test Methods for Evaluating Properties of Wood-Based Fiber and Particle Panel Materials [33], which was determined by the greater similarity of both products. Ten specimens were evaluated for each test: average density (ρ), 24 h thickness swelling (TS), static bending (modulus of rupture (MOR) and modulus of elasticity (MOE)), and perpendicular traction (internal bond strength (IB)). Samples measuring 50 × 50 mm were used for the thickness swelling and internal bond tests and 350 × 50 mm for the bending test. The mechanical evaluations were carried out on a BioPdi universal testing machine with a capacity of 10 kN and a computerized system that allows control of the test variables obtained and the kN collection data (test speed of 8 mm/min for bending test and 4 mm/min for perpendicular tensile). The results were compared with the standards NBR 14810-2: Medium-density particleboard—Part 2: Requirements and test methods (in Portuguese) [34], and ISO 16893:2016: Wood-based panels—Particleboard [35].

2.3. Further Assessment

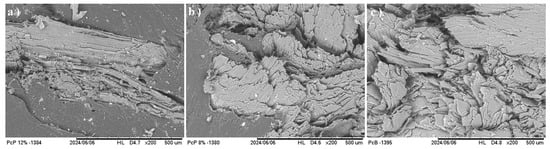

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) analysis was carried out to evaluate the hybrid panel samples developed qualitatively. Therefore, the pore anatomy, particle compaction, and the chemical–mechanical interaction between the sugarcane bagasse and the waste plastic were associated with the physical and mechanical properties obtained. The analysis was carried out using a Hitachi TM-3000 low-vacuum scanning electron microscope.

2.4. Exposure of Hybrid Panels to Natural and Accelerated Weathering

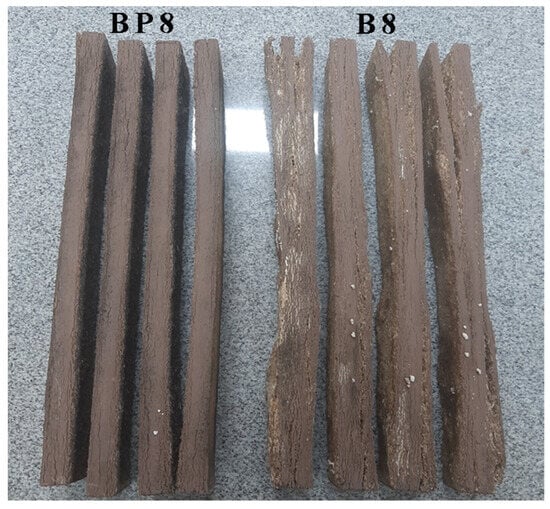

The hybrid panels with reduced resin content (BP8) were subjected to the natural and accelerated weathering test to compare their performance to those produced only with sugarcane bagasse (B8).

For natural weathering exposure, the procedure was based on the methodology reported by Garzón-Barrero et al. (2016) [36], adapted from ASTM D1435—Standard Practice for Outdoor Weathering of Plastics (1994) [37]. Eight specimens of each composition, with dimensions of 350 × 50 mm, were tested. The edges of the samples were coated with an acrylic paste to reduce the degradation caused by environmental agents in these more vulnerable regions created during specimen cutting.

The natural weathering test was carried out in the natural aging field at USP-FZEA (Pirassununga, São Paulo, Brazil), using a table inclined at 30° to magnetic north. The samples were exposed for a period of 6 months, between January and July 2024.

Similarly, the accelerated weathering test employed eight specimens of 350 × 50 mm for each panel type, also coated with acrylic paste. The procedure followed the methodology adapted from Fiorelli, Bueno, and Cabral (2019) [8], designed to simulate indoor environments characterized by high humidity and elevated temperatures. The samples were subjected to eight 12 h cycles in a climate chamber (model EQUV-EQUILAN), consisting of 8 h of UVB radiation (0.49 irradiance at 60 °C) followed by 4 h of condensation (50 °C).

At the end of both weathering tests, the specimens were subjected to static bending to determine the mechanical properties of MOR and MOE, and thus evaluate the mechanical performance between the hybrid panel and the one using only sugarcane bagasse.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

The values found for the physical and mechanical properties of the sugarcane bagasse and waste plastic particleboards were evaluated using descriptive statistics to organize the results. The arithmetic mean was used as a measure of central tendency and the standard deviation as a dispersion measure.

Once the descriptive analysis stage had been completed, the data obtained was subjected to an inferential analysis to verify the existence of significant variance between the different treatments and the studied compositions. The data was then analyzed using analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Tukey’s multiple comparison test, with confidence p < 0.05. The tests were carried out using Minitab® software version 21.1.1.

2.6. Life Cycle Assessment

LCA was developed based on the guidelines of ISO 14040: Environmental Management—Life Cycle Assessment—Principles and Framework and 14044: Environmental Management—Life Cycle Assessment—Requirements and Guidelines [30,38].

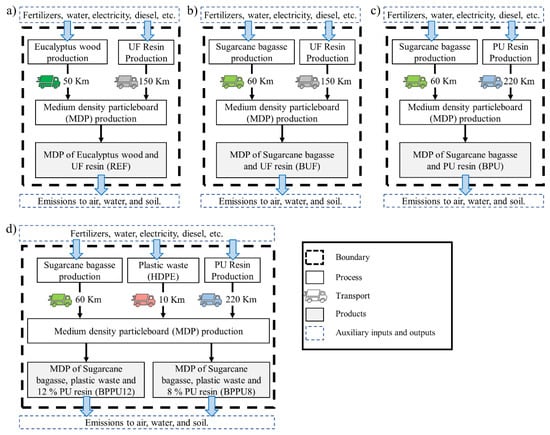

To this end, this study presents a comparative attributional LCA between five medium-density particleboard productions: Eucalyptus + UF resin (REF), sugarcane bagasse + UF resin (BUF), sugarcane bagasse + PU resin (BPU), sugarcane bagasse + waste plastic + 12% PU resin (BPPU12) and sugarcane bagasse + waste plastic + 8% PU resin (BPPU8). This LCA aims to assess whether the incorporation of waste plastic can help mitigate the potential negative environmental impacts of particleboard production.

The studied system function was established for medium-density particleboard for non-structural use applications in a dry environment, following standard NBR 14810-2:2018, and for general use and furniture production in dry conditions meeting the requirements demanded by ISO 16893-2016. Thus, the functional unit defined for this study was the production of a particleboard of 1 m3 with a density of between 700 and 750 kg/m3.

The reference flows for this study are shown in Table 1, where the quantities shown for the REF panel, BUF, and BPU were obtained from previous articles, while the quantities for BPPU12 and BPPU8 are from the present study.

Table 1.

Composition of particleboards.

The geographical scope of this study was based on the work of Gavioli (2024) [4] and adapted for the incorporation of HDPE waste plastic as a raw material in the production of BPPU12 and BPPU8 panels. The geographical scope is in the interior of the state of São Paulo, Brazil, considering the transportation of the main raw materials used in the different particleboard productions in this study (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Geographic scope location of raw materials and panel production.

The Cradle-to-Gate system was adopted, which encompasses the production, acquisition, transportation, and preparation of raw materials and the production of panels. Concerning the raw materials eucalyptus and sugar cane bagasse, the main activities of the agricultural or forestry phases are growing seedlings, preparing the soil, planting seedlings, handling, harvesting, and transportation. All these raw materials are dried, chipped, or ground and classified so that they can then be molded and pressed along with resins (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Cradle-to-gate system boundaries. (a) REF production; (b) BUF production; (c) BPU production; (d) BPPU12 and BPPU8 production.

The previous waste plastic production impacts were not considered in the process, since HDPE plastic is not currently produced for this purpose, and the product used comes from a recycling process where it is characterized as waste from an inefficient sorting process, i.e., it is a material destined for landfill without expectations of being reused. However, all the afterward-related impacts were considered, such as transportation to the panel factory, as well as all the steps required to process the plastic particles.

Also, within this context, the processing stage of the waste plastic does not require processing in a knife mill to obtain particles, since the waste is already collected in particulate form and therefore the energy costs were disregarded, based on the Lippel knife granulator mill used for this purpose during the panel production stage. The sieving stage to obtain the particle size and filter out dirt and undesirable aggregates was maintained.

Finally, it was also assessed that the 200 °C pressing process used in this work does not lead to significant volatile organic compound (VOC) emissions from the waste plastic. According to research by Yamashita et al. (2009) [40], VOC emissions from polyethylene are only significant above 200 °C, with higher rates around 250 °C for, for example, aldehyde and ester emissions.

The life cycle inventory (LCI) stage was developed using primary data from a Brazilian PU castor oil resin company (energy consumption, water consumption, and volume of raw materials) and secondary data extracted from a database with an information portion contextualized for the European region (Table 2). When complete national data were unavailable, European inventories from the Ecoinvent 3.8 database were used due to their technological coverage and methodological consistency. In these cases, adaptations were made for the Brazilian context, such as replacing the European energy mix with the national electricity matrix and using primary data for castor oil resin production, in addition to using national transport and agricultural process data whenever available. Thus, the use of European data was not indiscriminate, but a methodologically accepted solution, with adjustments that minimize regional biases and ensure representativeness of the Brazilian scenario.

Table 2.

The life cycle inventory.

In this study, sugarcane bagasse was considered a by-product of the sugar-energy industry, and not a valueless residue, since it has consolidated commercial applications and represents a relevant flow in the industrial process. Therefore, a mass allocation criterion was adopted, attributing 20.61% of the environmental impacts of the previous stages of the process, including cultivation, harvesting, sugarcane transport, and juice extraction, to the bagasse. This percentage was defined based on laboratory measurements and experimental quantifications carried out in this study, ensuring consistency with the real scenario of material generation and utilization.

This data was processed using GaBi 6 software, the Ecoinvent 3.8 database, and previous literature on the processes used. The ReCiPe2016 methodology [41] was used to develop the LCA, as it is one of the most up-to-date methods available and covers many impact categories. The LCA therefore took place through a midpoint assessment at a hierarchical level using the ReCiPe2016 v.1.1 version and evaluating categories chosen based on previous work, such as Silva et al. (2013) [31] and Gavioli et al. (2024) [4], as well as categories that highlight the importance of reducing resin content by incorporating waste plastic. The categories assessed are Climate change (including biogenic carbon); Fossil depletion; Freshwater consumption; Freshwater ecotoxicity; Human toxicity, cancer; Human toxicity, non-cancer; Photochemical ozone formation, ecosystems; Photochemical ozone formation, human health; Terrestrial acidification; and terrestrial ecotoxicity.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Physical and Mechanical Properties of Panels

Table 3 shows the average values of the properties, both physical and mechanical, of the BP12, BP8, and B8 compositions and compares them with the values established for the NBR 14810:2 (2018) [34] and ISO 16893 (2016) [35] standards.

Table 3.

Mean values of the physical and mechanical properties for each particleboard composition and normative guidelines.

According to the values presented above, the properties of TS, MOR, and IB, the BP12 and BP8 panels show no statistical differences between them, according to the Tukey test (p < 0.05). On the other hand, the B8 panel shows inferior results and statistical differences (p < 0.05) compared to BP12 and BP8 for all the physical and mechanical properties evaluated.

The results show that the hybrid panels, even with the 8% PU castor oil resin content, meet the minimum requirements of both standards. On the other hand, the panel made only with sugarcane bagasse particles failed to meet the normative recommendations given the high TS index and the low IB value obtained when a lower resin content was used.

In this context, although BP8 panels do not meet NBR14810-2 (2018) for structural use due to the MOE property (2300 MPa), the composite is still viable for this purpose according to the international standard ISO 16893 (2016) (2100 MPa).

Duran et al. (2025) [24] also evaluated the incorporation of HDPE to produce sugarcane bagasse particleboards but with a higher content of PU castor oil resin (15%). Consistent with the findings of Lopez et al. (2021) [25], Nogueira et al. (2022) [5], and Campos et al. (2023) [26], the authors observed that increasing the pressing temperature promotes improvements in the physical and mechanical properties of hybrid panels if the initial melting of the incorporated plastic occurs. Conversely, they reported that at conventional pressing temperatures, such as 100 °C, the interfacial bonding between the lignocellulosic particles and the polymer matrix is limited, thereby compromising the composite’s overall performance. This behavior substantiates the need for higher processing temperatures.

However, although particleboards produced from lignocellulosic residues and PU castor oil resin can be manufactured at pressing temperatures of 100 °C, as reported by Duran et al. (2023) [2], Fiorelli, Bueno and Cabral (2019) [8] and Yano et al. (2020) [42], a substantial reduction in resin content may be impractical, since it results in physical and mechanical properties below the minimum requirements established by technical standards, as observed in the present study. In this context, the incorporation of waste plastics, materials that would otherwise be discarded, represents a potential strategy to optimize the particleboard manufacturing process by reducing the amount of adhesive resin required.

Figure 4 illustrates the microstructure of panels BP12 (a), BP8 (b), and B8 (c) observed with SEM images at 200x magnification. From these images and the results of the properties shown in Table 3, the waste plastic can act as a partial substitute for the resin, promoting the packing of the sugarcane bagasse particles, reducing the number of empty spaces, and making it possible to anchor the fibers.

Figure 4.

SEM images of the panels at 200× magnification. (a) panel BP12; (b) panel BP8; (c) panel B8.

However, as observed by Lopez et al. (2021) [25], the “encapsulation” of the lignocellulosic particles by the plastic does not occur due to the technology applied (compression), which does not allow full melting down of the plastic, which perhaps would not happen in an extrusion or injection process. Despite these defects in the lignocellulosic material surface covering, the panel’s performance still exhibits satisfactory physical and mechanical properties.

Campos et al. (2023) [26] also evaluated the production of medium-density particleboard with added plastic, producing panels combining Pinus wood particles and PET plastic. The work developed by the authors also used a lower content of castor bean PU resin (10% by mass) and presented physical and mechanical results indicating the application feasibility for structural use following standard NBR 14810-2 (2018), demonstrating the potential of associating plastic in composite panels.

Figure 4c illustrates that, with reduced resin content, the lignocellulosic particles agglomerate less, and the panels using only sugarcane bagasse, even at a pressing temperature of 200 °C, are unable to maintain their physical and mechanical properties. This is due to the porosity of the particles themselves associated with the lower resin content applied, which, given the lower pore filling and the lower compaction of the particles, does not enable good TS and IB indices for the composite.

According to Solt et al. (2019) [43] and Bekhta et al. (2021) [44], although resin only represents 2 to 14% of the dry mass of wood in panels, the cost of resin can correspond to around 30 to 50% of the total costs of the materials used to produce the panels. It is therefore important to control and optimize resin costs in particleboard production since, even at low concentrations, it significantly impacts the price of the final product. In this context, incorporating waste plastic as a partial resin substitute can consequently reduce the production costs of particleboard.

3.2. Exposure to Natural and Accelerated Weathering of Reduced Resin Content Panels

Table 4 shows the average values of the mechanical properties of the different panel compositions with reduced resin content evaluated before and after the natural and accelerated weathering test.

Table 4.

Mean values of mechanical properties for each optimized particleboard composition.

The MOR and MOE properties for both compositions, BP8 and B8, showed statistical differences (p < 0.05) between the results before and after the accelerated weathering test. The compositions suffered a drop in mechanical performance after the accelerated weathering conditions, as also observed by Garzón-Barrero et al. (2016) [36] and Fiorelli, Bueno, and Cabral (2019) [8].

According to Fiorelli, Bueno, and Cabral (2019) [8], continuous exposure to moisture can cause dimensional instability in lignocellulosic compounds, which can release tensions between the fiber and the resin. Other factors also contribute to performance loss, such as water, temperature, and the influence of long and short-wave ultraviolet, which can degrade PU castor oil resin. Finally, the authors state that the decrease in MOR and MOE properties can be explained by the degradation of the resin and fibers in contact with water, which acts as an oxidation accelerator.

Nonetheless, the evaluation of physical and mechanical properties prior to weathering indicates that the BP8 panel is suitable for use under dry conditions. After undergoing accelerated weathering, the optimized hybrid panel retained an MOR value that complies with the minimum requirements (11 MPa) set by NBR 14810-2 (2018) and ISO 16893 (2016), with its MOE value also remaining close to the standards’ minimum threshold (1600 MPa). In contrast, panel B8, which consists exclusively of sugarcane bagasse particles, failed to exhibit similar performance, underscoring the potential of waste plastic particles to enhance the durability of composite panels.

Furthermore, the results obtained from the natural weathering test demonstrated a notable reduction in the MOR and MOE of the BP8 and B8 formulations. Exposure for six months to environmental factors such as sunlight, rainfall, humidity, and temperature fluctuations facilitates microbial colonization, as reported by Garzón-Barrero et al. (2016) [36], and can thus lead to the degradation of the lignocellulosic material, which consequently reduces the mechanical performance of the composite.

As mentioned above, the “encapsulation” of the sugarcane bagasse particles by the plastic does not occur completely (Lopez et al., 2021) [25]. In the meantime, the defects caused by this aspect can, therefore, contribute to detachment between the particles and favor water absorption in the composites, causing a reduction in mechanical properties after weathering tests.

Although both formulations exhibited a pronounced decline in MOR and MOE, the BP8 panel demonstrated markedly superior resistance to natural weathering, with mechanical properties approximately three times higher than those of the B8 panel. As illustrated in Figure 5, BP8 specimens also maintained enhanced dimensional stability, which can be attributed to the presence of waste plastic that promoted the anchoring of sugarcane bagasse particles and mitigated water absorption, due to the inherently hydrophobic characteristics of HDPE particles [45].

Figure 5.

Comparison of test specimens of BP8 and B8 panels after natural weathering.

3.3. Life Cycle Assessment Results

Table 5 presents the overall results of the potential environmental impacts of the 10 impact categories discussed throughout this topic and in accordance with the production of the chosen panel type.

Table 5.

Overall LCIA results at midpoint level for each panel production evaluated.

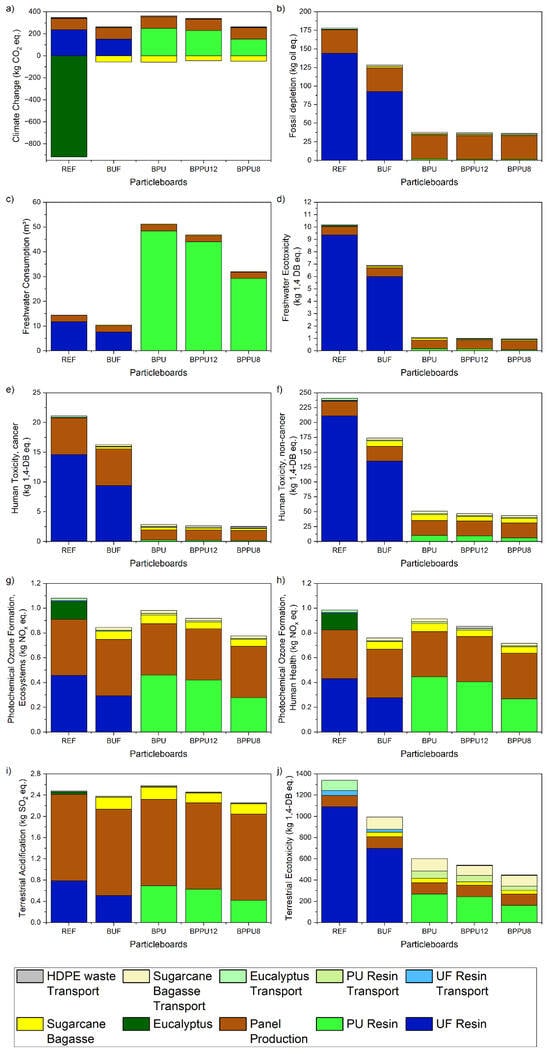

Of the 10 impact categories evaluated, BPU8 panels had the best environmental performance in 8, while REF panels were the worst in 7 categories. The intermediate panels that use sugarcane bagasse show results with significant changes depending on the type and quantity of resin used. The overall results show that the reduced amount of resin is a highly sensitive production factor to potential environmental impacts, highlighting the importance of using waste plastic as a partial substitute for PU castor oil resin.

The subtopics below present the discussion for each impact category evaluated in more detail.

3.3.1. Climate Change Including Biogenic Carbon

Figure 6a shows the impact results for the climate change (CC) category, including carbon sequestration. This category can have several negative effects on the entire planet since it influences climate change and can consequently contribute to the extinction of animal species, loss of biodiversity, melting glaciers (rising sea levels), fires, and human health problems.

Figure 6.

Environmental impact results. (a) Climate change; (b) Fossil depletion; (c) Freshwater Consumption; (d) Freshwater ecotoxicity; (e) Human toxicity, cancer; (f) Human toxicity, non-cancer; (g) Photochemical ozone formation, ecosystems; (h) Photochemical ozone formation, human health; (i) Terrestrial acidification; (j) Terrestrial ecotoxicity.

Regarding the CC category, the REF panel has the lowest impact potential among the panels evaluated, with a positive index of −571 kg CO2 eq. This is due to carbon sequestration during the Eucalyptus wood cultivation stage, which absorbs a large volume of CO2 during photosynthesis. Although the sugarcane cultivation stage also manages to sequester carbon, the volume absorbed is insufficient to neutralize the amount emitted in other process stages.

According to the table, the resin production stage affects mostly the CC category, where the production of UF resin accounts for over 70% of the impact generated in producing the BUF panel. The PU castor oil resin is also the most responsible for impacting the other panels, with the BPPU8 panel accounting for the lowest impact among the panels using the resin, given the reduction in the resin content. Using derived compounds from fossil raw materials or non-renewable sources to obtain electric energy also contributes to those impacts.

Moreover, the production of UF resin contributes significantly to the impacts since urea and methanol cause carbon dioxide and methane emissions. Concerning the PU castor oil resin, the contribution is related to the castor bean cultivation process, with emissions in the field due to fertilizer use and production.

The second stage that contributes most to the CC category is the production of the panels, given that part of the electricity comes from non-renewable sources and heavy fuel oils.

3.3.2. Fossil Depletion

The Fossil Depletion (FD) category concerns the consumption of fossil-based compounds throughout production. Figure 6b shows the impacts related to the FD category. For panels using UF resin (REF and BUF), the main hotspot corresponds to the production of this resin, while for panels using PU castor oil resin (BPU, BPPU12, and BPPU8), the main hotspot regards producing the proper panel.

Regarding the production of panels using UF resin, the main hotspot occurs due to the large use of fossil resources in the manufacture of the adhesive, such as urea and methanol, which use mineral coal and natural gas in their production [32]. Although PU castor oil resin also impacts this category, due to the consumption of fossil fuels in transportation and equipment during the cultivation phase, it is not as significant as conventional resin.

The panel production phase is also important for the DP category, representing more than 80% of the impact of producing panels that use PU castor oil resin as a binder. Gavioli et al. (2024) [4] observed that this is due to heavy fuel oil consumption as a thermal energy resource, diesel for internal transportation, and fossil resources for a small fraction of energy production in the Brazilian context [46].

3.3.3. Freshwater Consumption

The Freshwater Consumption (FC) category shows the impacts of water consumption in each panel’s production process in m3. Figure 6c shows that the main hotspot for the CF category regards the production of adhesive resins and, secondarily, the actual production of panels. For this category, the energy mix is highly relevant, since more than 50% of Brazil’s electricity comes from hydroelectric plants [46]. In this sense, the energy consumption of the industrial stages will be directly impacted, and the greater the consumption, the greater the impact on CF.

The irrigation stage to produce castor beans is crucial for production since high water consumption is required [47], which impacts panel production using PU castor oil resin as a binder. In this scenario, the production of PU castor oil resin could represent up to 90% of the impact in the FC category, demonstrating once again the importance of reducing the resin content in production, which could be made possible by incorporating waste plastic into the process.

3.3.4. Freshwater Ecotoxicity

Water contamination with regard to the emissions of toxic substances is represented by the Freshwater Ecotoxicity (FE) category. The graph illustrated in Figure 6d shows the results for the FE category, with the panels produced with UF resin presenting the highest impact indices, as also observed by Gavioli et al. (2024) [4]. In general, the actual production of the panels is once again highly relevant to the impacts of the panel manufacturing process.

Due to the formaldehyde emissions that occur during the production process of UF resin (when formaldehyde is generated by the condensation reaction, in addition to the residual formaldehyde in the resin) and urea, panels produced with conventional resin have a much higher impact on the FE category [48], with the REF panel displaying an index over 10 times higher than the BPPU8 panel.

It can also be seen that although the use of pesticides in the cultivation stage of both sugarcane and castor beans affects the FE category, the potential impacts are much lower than those generated by emissions from UF resin. Therefore, reducing sugarcane bagasse and PU castor oil resin by incorporating plastic is not very relevant but makes it viable by a lower impact in making BPPU8 panels.

3.3.5. Human Toxicity, Cancer

The Human Toxicity [Cancer] (HTC) category presents the potential impacts of the release of toxic substances, which, when inhaled or ingested, can cause health problems such as cancer.

Figure 6e displays a graph showing the results for the HTC impact category. The production of the adhesive used in UF resin panels represents the main hotspot in the process, while for the other processes, it would be the actual production stage of the panels.

The major influence of UF resin on REF and BUF panels is mainly due to formaldehyde emissions and nitrogen oxide emissions from urea, which also contribute to this category. The European Panel Federation (2018) [49] reports on the possibility of formaldehyde emissions causing human health problems, such as cancer. On the other hand, the production of PU castor oil resin also presents emission problems, mainly due to isocyanate, pesticides, and fertilizers used in the castor bean cultivation stage.

As observed by Gavioli et al. (2024) [4] and Silva et al. (2014) [32], the panel production phases are highly relevant to this category, especially the emissions associated with spraying the resin, heating during the composite material pressing process and electricity generation, the latter linked to non-renewable sources such as coal and oil.

Although the panel production stage releases emissions for all the processes evaluated, UF resin represents the largest fraction of the potential environmental impacts, with the REF panel displaying an impact index 8 times higher than the BPPU8 panel for the HTC category.

3.3.6. Human Toxicity, Non-Cancer

As mentioned for the HTC category, the Human Toxicity [non-cancer] (HTnC) category also presents potential impacts of releasing toxic substances that, when inhaled or ingested, can cause health problems but are not carcinogenic.

Figure 6f shows the results for the HTnC category. The REF and BUF panels have the highest rates for this category due to the use of UF resin, as also reported by Duran et al. (2024) [47]. In addition, the production stage of conventional resin is the main hotspot for panels that use it, given the substances emitted during its production.

The overall panel production stage matters for the impacts of the HTnC category. The second stage possesses the greatest impact for production with UF resin and the first stage for production with PU castor oil resin. Concerning PU castor oil resin production, the sugarcane and castor bean cultivation stages are more important due to pesticide use and field emissions.

Although the PU castor oil resin production stage is not the main hotspot for the HTnC category, partially replacing it by incorporating waste plastic makes the BPPU8 panel categorically viable for production with the lowest potential environmental impact.

3.3.7. Photochemical Ozone Formation, Ecosystems and Human Health

The photochemical ozone formation [ecosystems] (POFE) and photochemical ozone formation [human health] (POFHH) categories present the environmental impacts related to NMVOC (non-methane volatile carbon compounds) emissions.

The graphs in Figure 6g and Figure 6h show the results for the POFE and POFHH categories, respectively. For both categories, one of the main hotspots is related to the actual production of the panels. Although they are not so significant, the transportation stage of the raw materials is more important than the other categories due to the emissions of volatile compounds from burning fuel.

The production of UF resin directly impacts these categories through urea production, due to VOC (volatile organic compounds) and hydrocarbon emissions. Regarding PU castor oil resin production, the greatest contributions occur with isocyanate, as VOC emissions, followed by diesel consumption in transport, use of agricultural machinery, and NO2 field emissions.

For both categories, incorporating waste plastic as a partial substitute for PU castor oil resin is an excellent way of mitigating the impact, making the BPPU8 panel viable for its lower-impact production than others evaluated. The panel productions using the PU castor oil resin, with no reduction in its content, have more impact than the BUF panel.

3.3.8. Terrestrial Acidification

Terrestrial acidification (TA) occurs due to the atmospheric deposition of inorganic substances in soil. The results for the TA category presented in Figure 6i show that the main production hotspot is linked to the panel production phase. In second place comes the production of UF and PU castor oil resins, with similar impact indices among the panels evaluated.

The panels’ actual production is the main cause of environmental impacts for the TA category due to the direct emissions of sulfur dioxide into the air, which can precipitate as acid rain and contaminate the soil.

The UF resin production stage contributes to the TA category through emissions from the production of urea and formaldehyde, which can generate emissions related to sulfur dioxide and NOx. Although PU castor oil resin manufacturing causes emissions, the main emissions come from castor bean cultivation, with NH3 and NO2, followed by pesticide production.

Once again, the incorporation of waste plastic makes the BPPU8 panel viable as a panel with the lowest environmental impact for the TA category. The partial replacement of castor bean PU resin with waste plastic in the BPPU8 panel results in an impact reduction of 12% compared to the BPU one.

3.3.9. Terrestrial Ecotoxicity

The Terrestrial Ecotoxicity (TE) category presents the results of the impacts caused by emissions equivalent to 1,4-dichlorobenzene, which can harm the soil. The TE category can also harm the development of certain plant species due to soil contamination.

As illustrated by Figure 6j, the results for the TE category show that the main hotspot for terrestrial ecotoxicity indices is the resin production stage, with emphasis on UF resin, which has the highest impact indices, as also seen by Duran et al. (2024) [47]. As was observed in the POFE and POFHH categories, the raw material transportation stages are also more relevant to the impacts caused by the TE category, in this case, with greater relevance than when compared to the panel production stage.

The UF resin is the highest contributor to impact indices in the TE category due to the production of urea and formaldehyde from methanol. On the other hand, PU castor oil resin’s contributions are due to the production of pesticides during the agricultural stage and the production of isocyanate during the industrial stage.

Regarding the TE category, the castor bean PU resin is an alternative for mitigating environmental impacts since replacing conventional resin significantly reduces the index. Incorporating waste plastic allows for a greater impact reduction, as seen in the graph where the BPPU8 panel displayed a decrease of nearly 33% of the impact compared to the REF one.

3.3.10. LCA Final Considerations

Based on the impact categories evaluated above, the resin production and the panel manufacturing stage are the two biggest environmental impact hotspots for all the types of panels compared in this study. In this sense, the resin production was the largest hotspot among all the panels for four (4) impact categories, while the actual panel production was the largest for two (2) ones.

The transportation stage was the least affected in this study since the factory was located strategically in São Paulo, close to regions with available raw materials for panel production. Therefore, the transportation of raw materials was the least impactful stage for all the categories, showing higher relevance only for the POFE, POFHH, and TE categories.

Concerning the type of resin used in the production, it was clear that the amount of adhesive used is sensitive to the impacts generated, especially in the categories where there is a parity of emissions between UF and PU castor oil resins. In the meantime, PU castor oil resin has proved to be an interesting substitute for conventional resin. However, it does have a disadvantage in the FC category, due to high water consumption for planting castor beans.

At last, the incorporation of waste plastic helped mitigate the significant impacts of sugarcane bagasse and the production stage of PU castor oil resin. The POFE, POFHH, TA, and TE categories stood out, where the incorporation of plastic was fundamental in reducing the impacts generated by the resin, with the BPPU8 panel presenting the lowest impact production.

In conjunction with the technical performance results, the LCA conducted in this study indicates that the hybrid panels are consistent with circular economy principles, particularly through the partial substitution of high environmental impact raw materials, such as UF resin, and the valorization of readily available resources, including sugarcane bagasse and residual plastic [4,10,19,22]. Further studies should be developed focusing on industrial scaling-up and sensitivity analyses.

4. Conclusions

This research presented quantitative and qualitative data on the incorporation of HDPE waste plastic as a partial substitute for PU castor oil resin in medium-density sugarcane bagasse particleboards, evaluating physical and mechanical properties and comparative LCA between hybrid and conventional particleboards.

The results obtained with reduced resin content demonstrate that the inclusion of waste plastic enables partial replacement of PU castor oil resin. Panels composed solely of sugarcane bagasse particles (B8) did not achieve satisfactory results in TS and IB properties according to the standards evaluated. In contrast, hybrid panels (BP8), containing incorporated plastic, achieved performance levels that allow structural use under dry environmental conditions according to ISO 16893 (2016), even with only 8% resin content.

The weathering assessments indicated that the incorporation of waste plastic contributes to the durability of particleboards, with the hybrid panels exhibiting superior mechanical indices compared to panels made solely from sugarcane bagasse. After the accelerated weathering test, the hybrid panels, even with reduced resin content, showed results much closer to the minimum use viability, according to the standards evaluated.

The LCA results further reinforce the benefits of hybridization: the BPPU8 panel, containing only 8% resin by mass, exhibited the lowest environmental impact in 8 out of 10 impact categories assessed, with no category showing the highest potential impact. This highlights the significance of incorporating waste plastic to mitigate the environmental footprint associated with PU castor oil resin.

In conclusion, this research advances sustainable materials development by being among the first studies to integrate plastic waste into lignocellulosic particleboards derived from sugarcane bagasse. The findings provide a promising strategy for valorizing industrial and agricultural residues, promoting circular economy practices, and supporting the achievement of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production) and SDG 13 (Climate Action).

For future research, we recommend exploring other lignocellulosic matrices combined with different proportions of HDPE and further analyses of panel performance under extreme environmental conditions of use and storage. In addition, the economic assessment of the process and studies into the feasibility of large-scale applications could contribute to the industrial adoption of the hybrid materials developed.

Author Contributions

A.J.F.P.D.: conceptualization, methodology, investigation, data curation, writing, reviewing and supervision. G.P.L.: investigation, data curation, writing and reviewing. L.E.C.F.: methodology, data curation and reviewing. G.A.d.C.H.: methodology, data curation and reviewing. J.A.R.: conceptualization, reviewing and supervision. J.F.: conceptualization, methodology, data curation, reviewing and supervision. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was financed, in part, by the São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP), Brazil (Process Number #2023/12355-0 and #2024/16946-5), by the Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (CAPES)–Brazil–Finance Code 001, and by CNPq (proc. 306131/2023-4 and 303850/2024-8).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Carvalho Araújo, C.K.; Bigarelli Ferreira, M.; Salvador, R.; de Carvalho Araújo, C.K.C.; Camargo, B.S.; de Carvalho Araújo Camargo, S.K.; de Campos, C.I.; Piekarski, C.M. Life Cycle Assessment as a Guide for Designing Circular Business Models in the Wood Panel Industry: A Critical Review. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 355, 131729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duran, A.J.F.P.; Lopes Júnior, W.E.; Pavesi, M.; Fiorelli, J. Assessment of Medium Density Panels of Sugarcane Bagasse. Cienc. Florest. 2023, 33, e69624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brito, F.M.S.; Bortoletto Júnior, G.; Paes, J.B.; Belini, U.L.; Tomazello-Filho, M. Technological Characterization of Particleboards Made with Sugarcane Bagasse and Bamboo Culm Particles. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 262, 120501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavioli, L.; Lopes Silva, D.A.; Bueno, C.; Rossignolo, J.A. Life Cycle Assessment as a Circular Economy Strategy to Select Eco-Efficient Raw Materials for Particleboard Production. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2025, 212, 107921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogueira, N.D.; Narciso, C.R.P.; de Lima Felix, A.; Mendes, R.F. Pressing Temperature Effect on the Properties of Medium Density Particleboard Made with Sugarcane Bagasse and Plastic Bags. Mater. Res. 2022, 25, 107921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, S.S.; Guimarães Júnior, J.B.; Mendes, L.M.; Mendes, R.F.; Protásio, T.d.P.; Lisboa, F.N. Valorization of sugarcane bagasse for production of low densityparticleboards. Rev. Ciência Madeira 2017, 8, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima Mesquita, A.; Barrero, N.G.; Fiorelli, J.; Christoforo, A.L.; De Faria, L.J.G.; Lahr, F.A.R. Eco-Particleboard Manufactured from Chemically Treated Fibrous Vascular Tissue of Acai (Euterpe oleracea Mart.) Fruit: A New Alternative for the Particleboard Industry with Its Potential Application in Civil Construction and Furniture. Ind. Crops Prod. 2018, 112, 644–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorelli, J.; Bueno, S.B.; Cabral, M.R. Assessment of Multilayer Particleboards Produced with Green Coconut and Sugarcane Bagasse Fibers. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 205, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klímek, P.; Wimmer, R.; Meinlschmidt, P.; Kúdela, J. Utilizing Miscanthus Stalks as Raw Material for Particleboards. Ind. Crops Prod. 2018, 111, 270–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Russell, J.D. Accelerating the Transition to Wood-Based Circular Bioeconomy: A Literature Review of Current State, Trends, Opportunities, and Priorities for Future Research. Curr. For. Rep. 2025, 11, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cangussu, N.; Chaves, P.; da Rocha, W.; Maia, L. Particleboard Panels Made with Sugarcane Bagasse Waste—An Exploratory Study. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 25265–25273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maraveas, C. Production of Sustainable Construction Materials Using Agro-Wastes. Materials 2020, 13, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, D.P.; Vilela, A.P.; Silva, D.W.; Napoli, A.; Mendes, R.F. Effect of Heat Treatment on the Properties of Sugarcane Bagasse Medium Density Particleboard (MDP) Panels. Waste Biomass Valorization 2020, 11, 6429–6441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorelli, J.; Gomide, C.A.; Lahr, F.A.R.; do Nascimento, M.F.; de Lucca Sartori, D.; Ballesteros, J.E.M.; Bueno, S.B.; Belini, U.L. Physico-Chemical and Anatomical Characterization of Residual Lignocellulosic Fibers. Cellulose 2014, 21, 3269–3277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwakiri, S.A.; de Andrade, A.S.; Cardoso, A.A., Jr.; Chipanski, E.d.R.; Prata, J.G.; Adriazola, M.K.O. Produção de Painéis Aglomerados de Alta Densificação Com Uso de Resina Melamina-Ureia-Formaldeido. Cerne 2005, 11, 323–328. [Google Scholar]

- Suana Sugahara, E.; Augusto Mello da Silva, S.; Soler Cunha Buzo, A.; Inácio de Campos, C.; Martines Morales, E.; Santos Ferreira, B.; dos Anjos Azambuja, M.; Rocco Lahr, F.A.; Christoforo, A.L. High-Density Particleboard Made from Agro-Industrial Waste and Different Adhesives. BioResources 2019, 14, 5162–5170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CONAB. Acompanhamento da safra brasileira de cana-de-açúcar 2023/2024—4° levantamento. Cia. Nac. Abast. Conab 2024, 11, 1–52. [Google Scholar]

- Buzo, A.L.S.C.; Silva, S.A.M.; de Moura Aquino, V.B.; Chahud, E.; Branco, L.A.M.N.; de Almeida, D.H.; Christoforo, A.L.; Almeida, J.P.B.; Lahr, F.A.R. Addition of Sugarcane Bagasse for the Production of Particleboards Bonded with Urea-Formaldehyde and Polyurethane Resins. Wood Res. 2020, 65, 727–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duran, A.J.F.P.; Lyra, G.P.; Campos Filho, L.E.; Martins, R.H.B.; Bueno, C.; Rossignolo, J.A.; Fiorelli, J. The Use of Castor Oil Resin on Particleboards: A Systematic Performance Review and Life Cycle Assessment. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertolini, M.D.S.; de Morais, C.A.G.; Christoforo, A.L.; Bertoli, S.R.; dos Santos, W.N.; Lahr, F.A.R. Acoustic Absorption and Thermal Insulation of Wood Panels: Influence of Porosity. BioResources 2019, 14, 3746–3757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uemura Silva, V.; Nascimento, M.F.; Resende Oliveira, P.; Panzera, T.H.; Rezende, M.O.; Silva, D.A.L.; Borges de Moura Aquino, V.; Rocco Lahr, F.A.; Christoforo, A.L. Circular vs. Linear Economy of Building Materials: A Case Study for Particleboards Made of Recycled Wood and Biopolymer vs. Conventional Particleboards. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 285, 122906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvez, I.; Garcia, R.; Koubaa, A.; Landry, V.; Cloutier, A. Recent Advances in Bio-Based Adhesives and Formaldehyde-Free Technologies for Wood-Based Panel Manufacturing. Curr. For. Rep. 2024, 10, 386–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Macedo, L.B.; Da Silva, M.R.; Da Silva César, A.A.; Panzera, T.H.; Christoforo, A.L.; Lahr, F.A.R. Painéis OSB de Madeira Pinus Sp. e Adição de Partículas de Polipropileno Biorientado (BOPP). Sci. For. Sci. 2016, 44, 887–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duran, A.J.F.P.; Filho, L.E.C.; Lyra, G.P.; Held, G.A.d.C.; Rossignolo, J.A.; Fiorelli, J. Evaluation of Physical and Mechanical Properties in Medium Density Particleboards Made from Sugarcane Bagasse and Plastic Waste (HDPE) at Different Pressing Temperatures. Ind. Crops Prod. 2025, 223, 120190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, Y.M.; Gonçalves, F.G.; Paes, J.B.; Gustave, D.; Gutemberg de Alcântara Segundinho, P.; Vicente de Figueiredo Latorraca, J.; Theodoro Nantet, A.C.; Suuchi, M.A. Relationship between Internal Bond Properties and X-Ray Densitometry of Wood Plastic Composite. Compos. Part B Eng. 2021, 204, 108477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, P.H.S.; Santos Junior, A.J.; de Souza, M.V.; Herradon, M.P.; Libera, V.B.L.; Dezen, L.E.; da Silva, É.V.; Silva, A.G.B.P.; Rodrigues, F.R.; Bispo, R.A.; et al. Evaluation and Production of High-Strength Wood Composite Panels with Polyethylene Terephthalate (PET). BioResources 2023, 18, 8528–8535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, F.R.; Bispo, R.A.; Cazell, P.H.; Silva, M.J.; Christoforo, A.L.; Silva, S.A.M. Particleboard Composite Made from Pinus and Eucalyptus Residues and Polystyrene Waste Partially Replacing the Castor Oil-Based Polyurethane as Binder. Mater. Res. 2023, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PICPLAST. Monitoramento dos Índices de Reciclagem Mecânica de Plásticos Pós-Consumo No Brasil, PICPLAST. 2022. Available online: https://www.abiplast.org.br/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/pesquisa-links.pdf (accessed on 24 July 2023).

- Costa, D.; Serra, J.; Quinteiro, P.; Dias, A.C. Life Cycle Assessment of Wood-Based Panels: A Review. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 444, 140955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 14040; Environmental Management—Life Cycle Assessment—Principles and Framework. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006.

- Silva, D.A.L.; Lahr, F.A.R.; Garcia, R.P.; Freire, F.M.C.S.; Ometto, A.R. Life Cycle Assessment of Medium Density Particleboard (MDP) Produced in Brazil. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2013, 18, 1404–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, D.A.L.; Lahr, F.A.R.; Pavan, A.L.R.; Saavedra, Y.M.B.; Mendes, N.C.; Sousa, S.R.; Sanches, R.; Ometto, A.R. Do Wood-Based Panels Made with Agro-Industrial Residues Provide Environmentally Benign Alternatives? An LCA Case Study of Sugarcane Bagasse Addition to Particle Board Manufacturing. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2014, 19, 1767–1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM D1037-12; Test Methods for Evaluating Properties of Wood-Base Fiber and Particle Panel Materials. American Society for Testing and Materials: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2020. [CrossRef]

- NBR 14810-2; Medium Density Particleboards: Part 2: Requirements and the Test Methods. Associação Brasileira de Normas Técnicas: São Paulo, Brazil, 2018.

- ISO 16893; Wood-Based Panels—Particleboard. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016.

- Garzón-Barrero, N.M.; Shirakawa, M.A.; Brazolin, S.; de Barros Pereira, R.G.d.F.N.; de Lara, I.A.R.; Savastano, H. Evaluation of mold growth on sugarcane bagasse particleboards in natural exposure and in accelerated test. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2016, 115, 266–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM D 1435-94; Standard Practice for Outdoor Weathering of Plastics. American Society for Testing and Materials: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 1994.

- ISO 14044; Environmental Management—Life Cycle Assessment -Requirements and Guidelines. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006.

- Çamlibel, O.; Aydin, M. Influence of Density on Medium-Density Fiberboard Properties At Industrial Scale Experimental. Pro Ligno 2023, 19, 11–20. Available online: https://www.proligno.ro/en/articles/2023/2/CAMLIBEL_Final.pdf (accessed on 20 October 2024).

- Yamashita, K.; Yamamoto, N.; Mizukoshi, A.; Noguchi, M.; Ni, Y.; Yanagisawa, Y. Compositions of Volatile Organic Compounds Emitted from Melted Virgin and Waste Plastic Pellets. J. Air Waste Manag. Assoc. 2009, 59, 273–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huijbregts, M.A.J.; Steinmann, Z.J.N.; Elshout, P.M.F.; Stam, G.; Verones, F.; Vieira, M.; Zijp, M.; Hollander, A.; van Zelm, R. ReCiPe2016: A Harmonised Life Cycle Impact Assessment Method at Midpoint and Endpoint Level. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2017, 22, 138–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yano, B.B.R.; Silva, S.A.M.; Almeida, D.H.; Aquino, V.B.M.; Christoforo, A.L.; Rodrigues, E.F.C.; Junior, A.N.C.; Silva, A.P.; Lahr, F.A.R. Use of Sugarcane Bagasse and Industrial Timber Residue in Particleboard Production. BioResources 2020, 15, 4753–4762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solt, P.; Konnerth, J.; Gindl-Altmutter, W.; Kantner, W.; Moser, J.; Mitter, R.; van Herwijnen, H.W.G. Technological Performance of Formaldehyde-Free Adhesive Alternatives for Particleboard Industry. Int. J. Adhes. Adhes. 2019, 94, 99–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekhta, P.; Noshchenko, G.; Réh, R.; Kristak, L.; Sedliačik, J.; Antov, P.; Mirski, R.; Savov, V. Properties of Eco-Friendly Particleboards Bonded with Lignosulfonate-Urea-Formaldehyde Adhesives and PMDI as a Crosslinker. Materials 2021, 14, 4875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalhat, M.A.; Adesina, A.Y. Utilization of Micronized Recycled Polyethylene Waste to Improve the Hydrophobicity of Asphalt Surfaces. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 240, 117966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Empresa de Pesquisa Energética (Brasil). Balanço Energético Nacional 2024: Ano Base 2023. Rio de Janeiro. 2024. Available online: https://www.epe.gov.br/pt/publicacoes-dados-abertos/publicacoes/balanco-energetico-nacional-2024 (accessed on 19 August 2024).

- Duran, A.J.F.P.; Lyra, G.P.; Campos Filho, L.E.; Bueno, C.; Rossignolo, J.A.; Alves-Lima, C.; Fiorelli, J. The Use of Sargasso Seaweed as Lignocellulosic Material for Particleboards: Technical Viability and Life Cycle Assessment. Buildings 2024, 14, 1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tohmura, S.I.; Inoue, A.; Sahari, S.H. Influence of the Melamine Content in Melamine-Urea-Formaldehyde Resins on Formaldehyde Emission and Cured Resin Structure. J. Wood Sci. 2001, 47, 451–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Panel Federation. Autonomous Agreement on a European Action Guide Regarding the Prevention of Formaldehyde Exposure in the European Panel Industry and Compliance with the Occupational Exposure Limits. 2018. Available online: https://europanels.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/epf-broch-formaldehyde-eng.pdf (accessed on 19 August 2024).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.