A Comprehensive and Multidisciplinary Framework for Advancing Circular Economy Practices in the Packaging Sector: A Systematic Literature Review on Critical Factors

Abstract

1. Introduction

Theoretical Framework

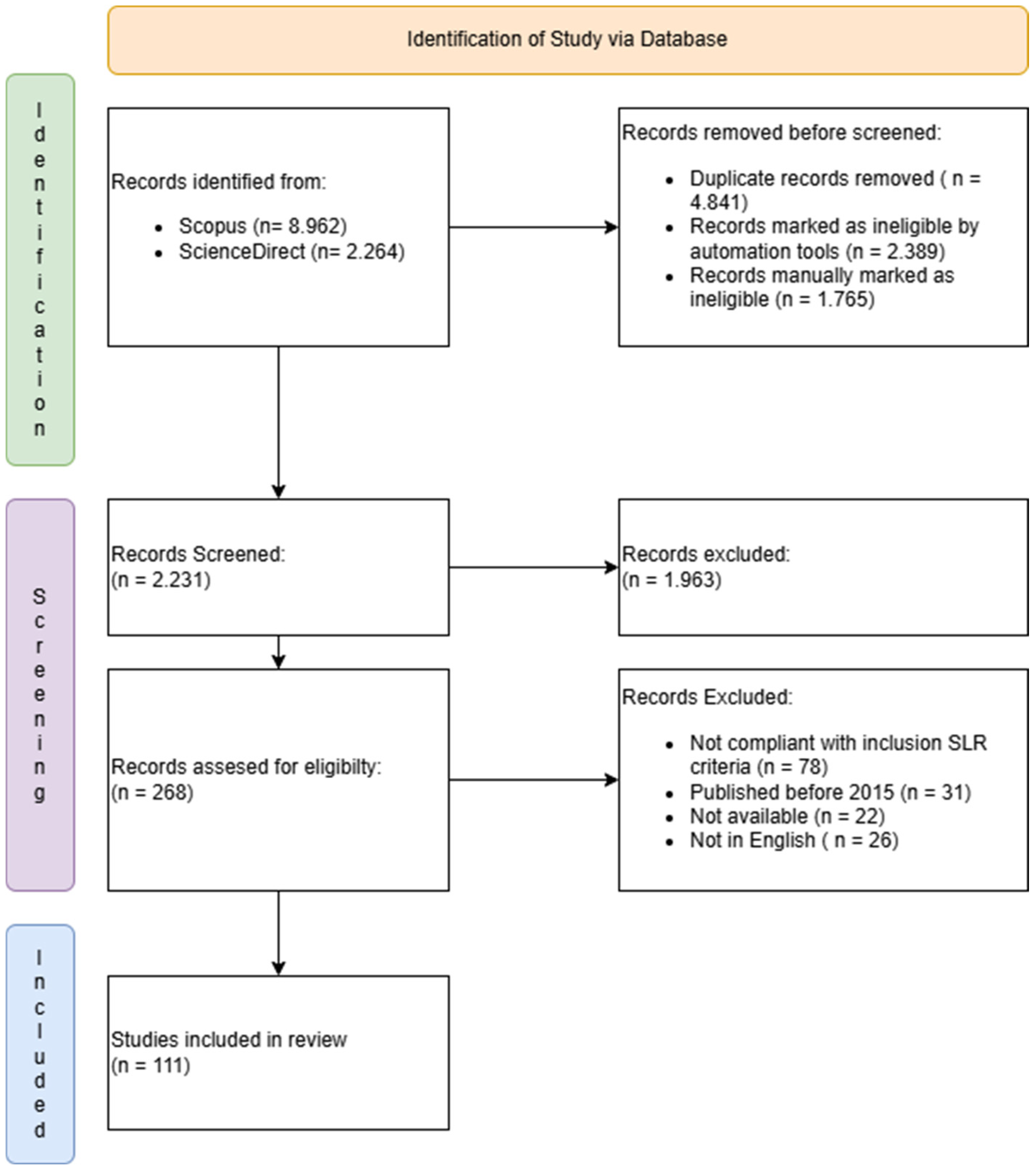

2. Methodology

3. Results

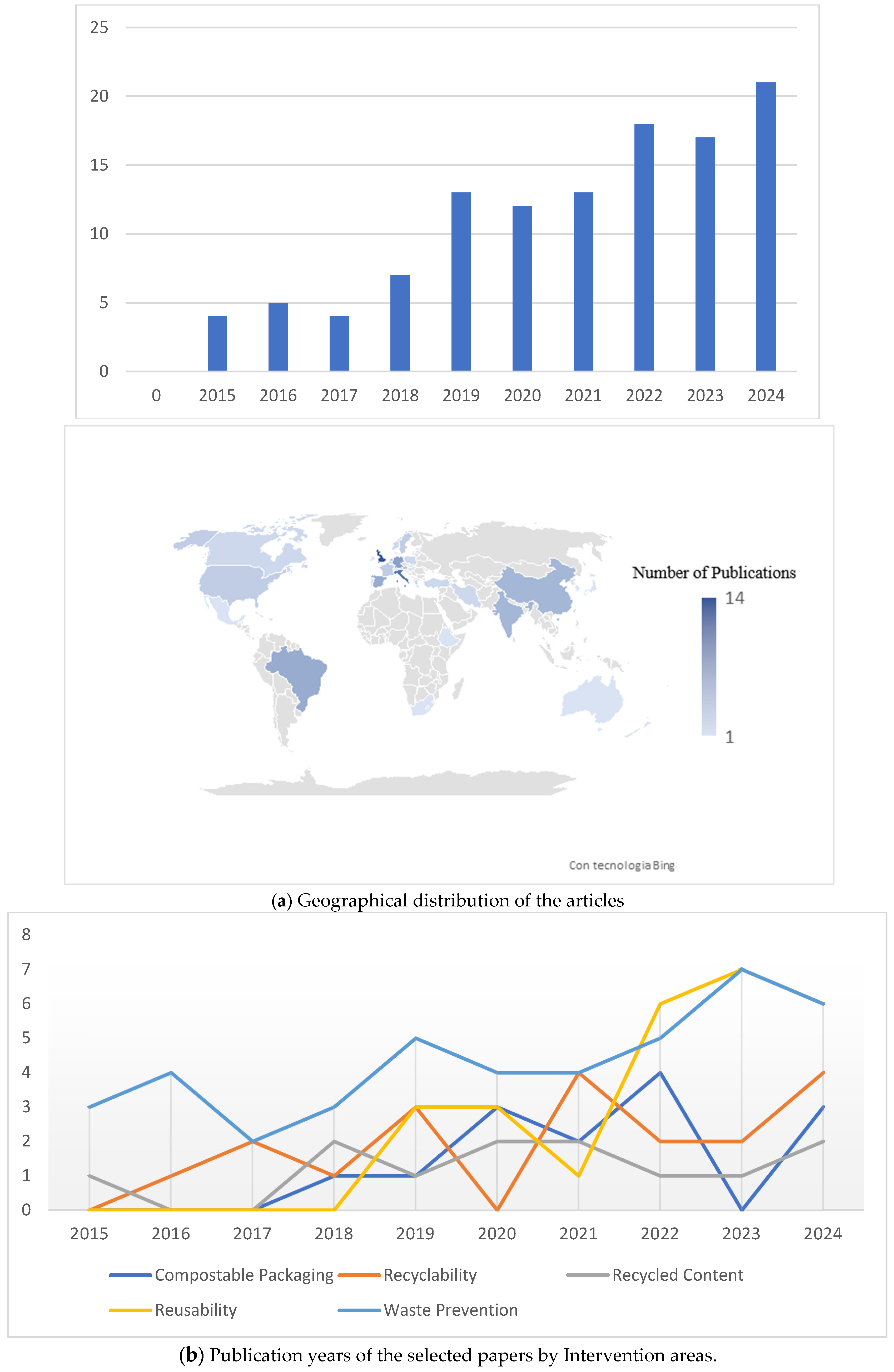

3.1. Overview of the Literature

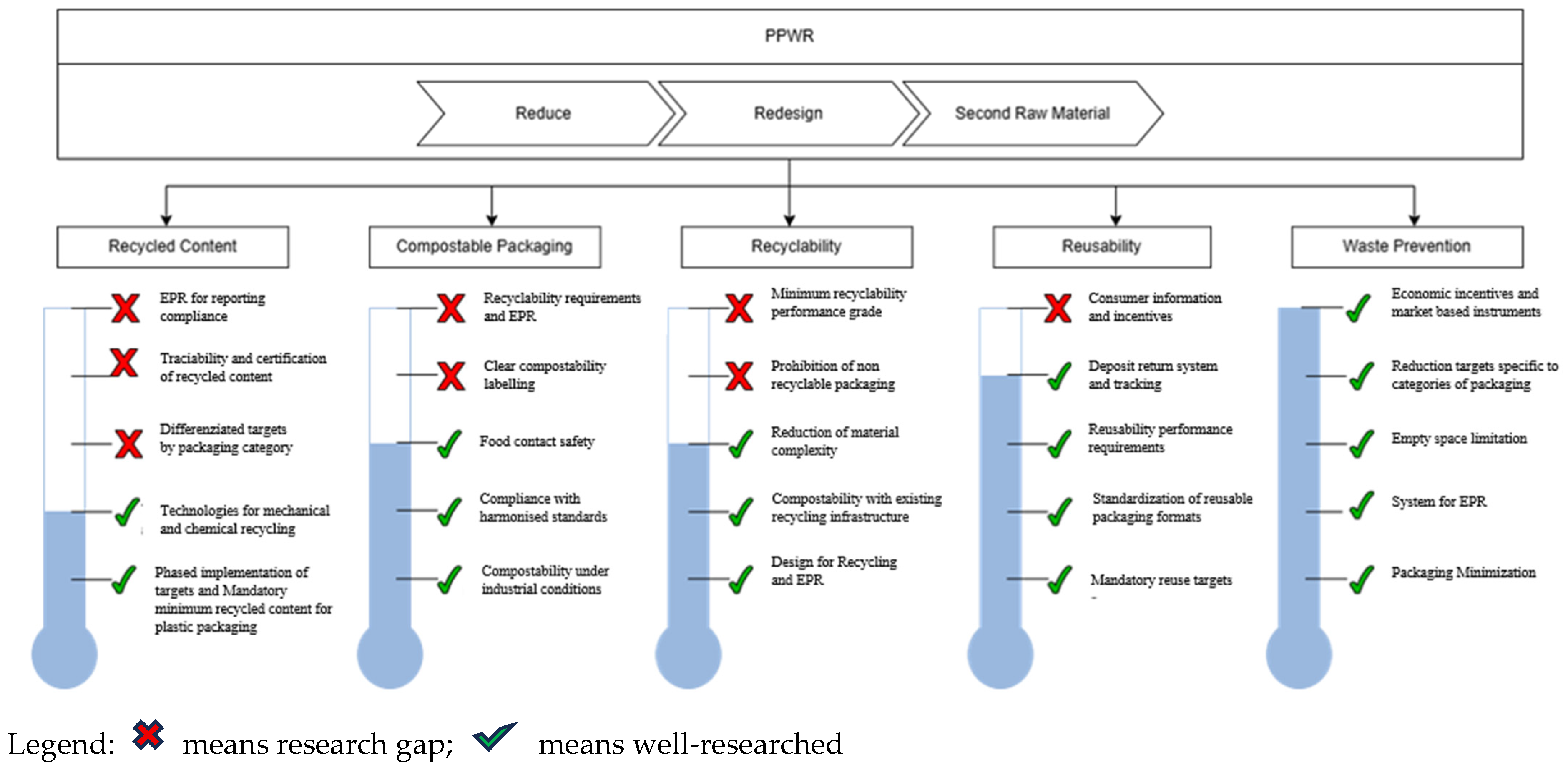

3.2. Intervention Areas

3.2.1. Waste Prevention

3.2.2. Reusability

3.2.3. Compostable Packaging

3.2.4. Recyclability

3.2.5. Recycled Content

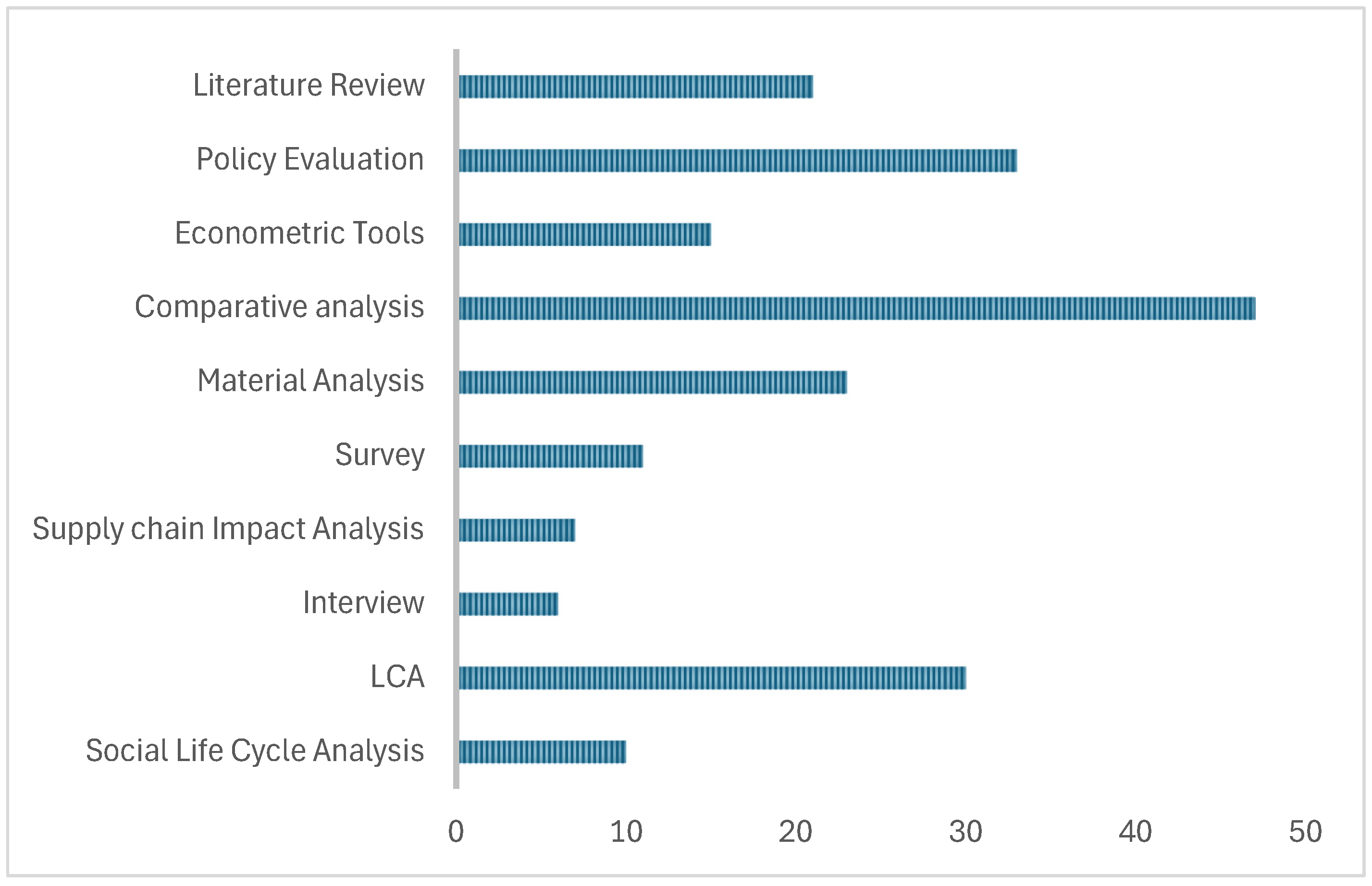

3.3. Methodological Integration Across PPWR Intervention Areas

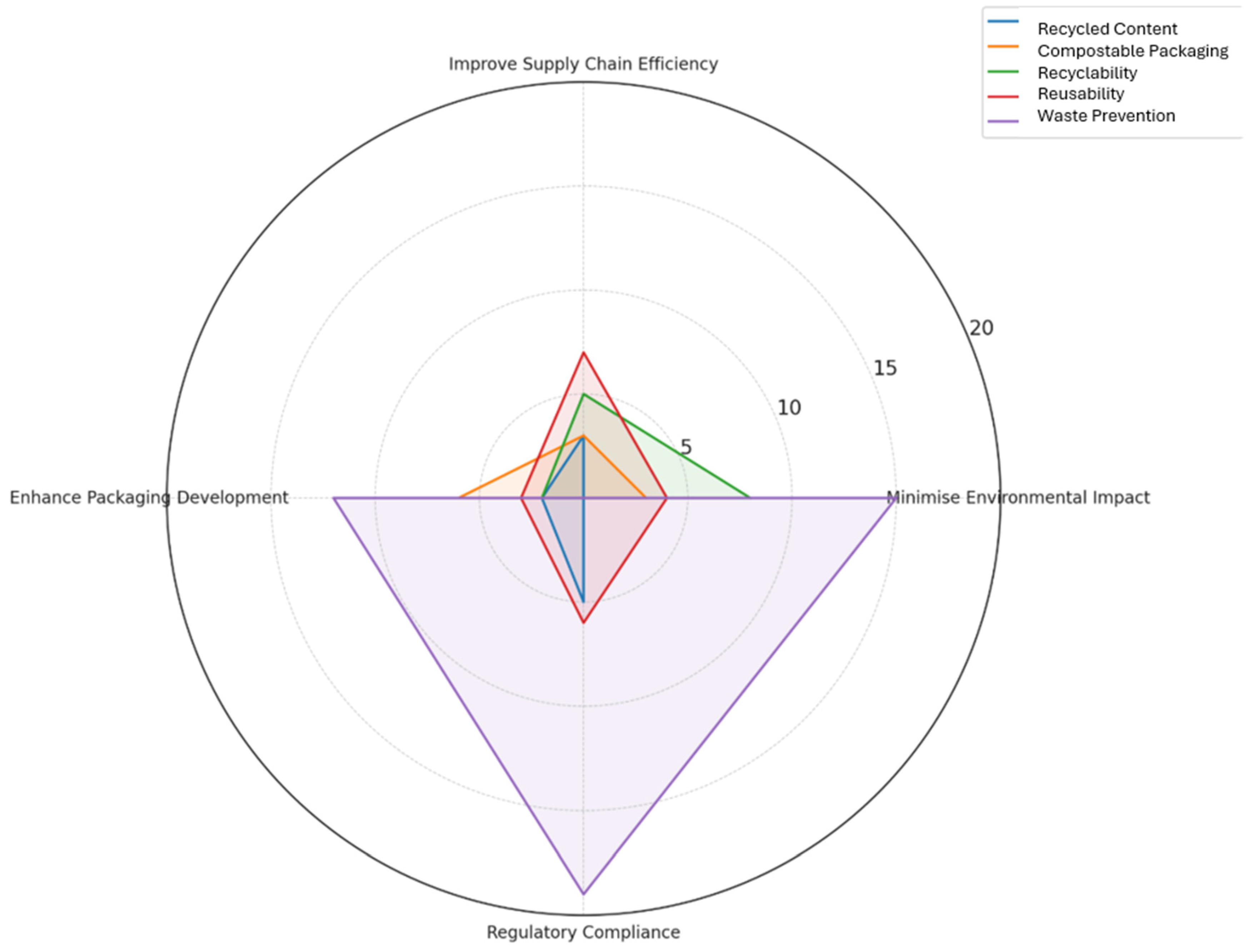

4. Discussion

Policy and Industry Implications

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mosconi, E.M.; Colantoni, A.; Tarantino, M.; Mosconi, E.M.; Colantoni, A.; Tarantino, M. Strategies for Enhancing the Efficiency of Packaging and Managing Packaging Waste in Compliance with Regulations. In Waste Management for a Sustainable Future-Technologies, Strategies and Global Perspectives; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Akbari, F. Integrated sustainability perspective and spillover effects of social, environment and economic pillars: A case study using SEY model. Socio-Econ. Plan. Sci. 2024, 96, 102077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, I.D.; Hamam, Y.; Sadiku, E.R.; Ndambuki, J.M.; Kupolati, W.K.; Jamiru, T.; Eze, A.A.; Snyman, J. Need for Sustainable Packaging: An Overview. Polymers 2022, 14, 4430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coelho, P.M.; Corona, B.; ten Klooster, R.; Worrell, E. Sustainability of reusable packaging–Current situation and trends. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. X 2020, 6, 100037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Union. Regulation (EU) 2025/40 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 19 December 2024 on Packaging and Packaging Waste, Amending Regulation (EU) 2019/1020 and Directive (EU) 2019/904, and Repealing Directive 94/62/EC (Text with EEA Relevance). Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2025/40/oj/eng (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- Banaeian, N.; Mobli, H.; Nielsen, I.E.; Omid, M. Criteria definition and approaches in green supplier selection—A case study for raw material and packaging of food industry. Prod. Manuf. Res. 2015, 3, 149–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, X.; Magnier, L.; Mugge, R. Switching to reuse? An exploration of consumers’ perceptions and behaviour towards reusable packaging systems. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2023, 193, 106972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustavo, J.U.; Pereira, G.M.; Bond, A.J.; Viegas, C.V.; Borchardt, M. Drivers, opportunities and barriers for a retailer in the pursuit of more sustainable packaging redesign. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 187, 18–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sastre, R.M.; de Paula, I.C.; Echeveste, M.E.S. A Systematic Literature Review on Packaging Sustainability: Contents, Opportunities, and Guidelines. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, N.; Pålsson, H. Industrial packaging and its impact on sustainability and circular economy: A systematic literature review. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 333, 130165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geueke, B.; Groh, K.; Muncke, J. Food packaging in the circular economy: Overview of chemical safety aspects for commonly used materials. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 193, 491–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichert, C.L.; Bugnicourt, E.; Coltelli, M.-B.; Cinelli, P.; Lazzeri, A.; Canesi, I.; Braca, F.; Martínez, B.M.; Alonso, R.; Agostinis, L.; et al. Bio-Based Packaging: Materials, Modifications, Industrial Applications and Sustainability. Polymers 2020, 12, 1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumter, D.; De Koning, J.; Bakker, C.; Balkenende, R. Key Competencies for Design in a Circular Economy: Exploring Gaps in Design Knowledge and Skills for a Circular Economy. Sustainability 2021, 13, 776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigamonti, L.; Ferreira, S.; Grosso, M.; Cunha Marques, R. Economic-financial analysis of the Italian packaging waste management system from a local authority’s perspective. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 87, 533–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seier, M.; Roitner, J.; Archodoulaki, V.M.; Jones, M.P. Design from recycling: Overcoming barriers in regranulate use in a circular economy. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2023, 196, 107052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgakoudis, E.D.; Tipi, N.S. An investigation into the issue of overpackaging-examining the case of paper packaging An investigation into the issue of overpackaging-examining the case of paper packaging. Int. J. Sustain. Eng. 2020, 14, 590–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoudi, M.; Parviziomran, I. Reusable packaging in supply chains: A review of environmental and economic impacts, logistics system designs, and operations management. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2020, 228, 107730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, C.G.; Corsini, L. A literature review and analytical framework of the sustainability of reusable packaging. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2023, 37, 126–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S.; Sarwo Utomo, D.; Dadhich, P.; Greening, P. Packaging design, fill rate and road freight decarbonisation: A literature review and a future research agenda. Clean. Logist. Supply Chain 2020, 4, 100066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afif, K.; Rebolledo, C.; Roy, J. Evaluating the effectiveness of the weight-based packaging tax on the reduction at source of product packaging: The case of food manufacturers and retailers. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2022, 245, 108391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meherishi, L.; Narayana, S.A.; Ranjani, K.S. Sustainable packaging for supply chain management in the circular economy: A review. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 237, 117582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joltreau, E. Extended Producer Responsibility, Packaging Waste Reduction and Eco-design. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2022, 83, 527–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilg, P. How to foster green product innovation in an inert sector. J. Innov. Knowl. 2019, 4, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimon, D.; Tyan, J.; Sroufe, R. Drivers of Sustainable Supply Chain Management: Practices to Alignment with Un Sustainable Development Goals. Int. J. Qual. Res. 2020, 14, 219–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarantino, M.; Mosconi, E.M.; Tola, F.; Gianvincenzi, M.; Matacera, A. Increasing circularity: A systematic review of the sustainable packaging transition towards the European regulation. In Qualità, Innovazione e Sostenibilità Nella Filiera Agro-Alimentare: Atti del Convegno dell’Associazione Italiana di Scienze Merceologiche, 2023; RomaTrE-Press: Rome, Italy, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Sazdovski, I.; Bojovic, D.; Batlle-Bayer, L.; Aldaco, R.; Margallo, M.; Fullana-i-Palmer, P. Circular Economy of Packaging and Relativity of Time in Packaging Life Cycle. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2022, 184, 106393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Politis, A.E.; Sarigiannidis, C.; Voutsinas, V. The Environmental Aspects of Packaging: Implications for Marketing Strategies. In Strategic Innovative Marketing and Tourism; Springer Proceedings in Business and Economics; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 965–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mengist, W.; Soromessa, T.; Legese, G. Method for conducting systematic literature review and meta-analysis for environmental science research. MethodsX 2020, 7, 100777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrini, M.; Marsili, F. Evaluating software tools to conduct systematic reviews: A feature analysis and user survey. Form@re-Open J. Form. Rete 2021, 21, 124–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batista, L.; Gong, Y.; Pereira, S.; Jia, F.; Bittar, A. Circular Supply Chains in Emerging Economies—A comparative study of packaging recovery ecosystems in China and Brazil. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2019, 57, 7248–7268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, R.; Islam, T.; Ghose, A.; Sahajwalla, V. Full circle: Challenges and prospects for plastic waste management in Australia to achieve circular economy. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 368, 133127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell-Johnston, K.; de Munck, M.; Vermeulen, W.J.V.; Backes, C. Future perspectives on the role of extended producer responsibility within a circular economy: A Delphi study using the case of the Netherlands. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2021, 30, 4054–4067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pigosso, D.C.A.; McAloone, T.C.; Rozenfeld, H. Characterization of the State-of-the-art and Identification of Main Trends for Ecodesign Tools and Methods: Classifying Three Decades of Research and Implementation. J. Indian Inst. Sci. 2015, 95, 405–427. [Google Scholar]

- Ceschin, F.; Gaziulusoy, I. Evolution of design for sustainability: From product design to design for system innovations and transitions. Des. Stud. 2016, 47, 118–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, R.; Jeanrenaud, S.; Bessant, J.; Denyer, D.; Overy, P. Sustainability-oriented Innovation: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2016, 18, 180–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kędzia, G.; Ocicka, B.; Pluta-Zaremba, A.; Raźniewska, M.; Turek, J.; Wieteska-Rosiak, B. Social Innovations for Improving Compostable Packaging Waste Management in CE: A Multi-Solution Perspective. Energies 2022, 15, 9119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragaert, K.; Huysveld, S.; Vyncke, G.; Hubo, S.; Veelaert, L.; Dewulf, J.; Bois, E.D. Design from recycling: A complex mixed plastic waste case study. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 155, 104646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ada, E.; Kazancoglu, Y.; Lafcı, Ç.; Ekren, B.Y.; Çimitay Çelik, C. Identifying the Drivers of Circular Food Packaging: A Comprehensive Review for the Current State of the Food Supply Chain to Be Sustainable and Circular. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, S.; Nayak, R.; Dora, M.; Mishra, N.; Ghadge, A. An integrated lean and green approach for improving sustainability performance: A case study of a packaging manufacturing SME in the U.K. Prod. Plan. Control 2019, 30, 353–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hage, O.; Sandberg, K.; Söderholm, P.; Berglund, C. The regional heterogeneity of household recycling: A spatial-econometric analysis of Swedish plastic packing waste. Lett. Spat. Resour. Sci. 2016, 11, 245–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, L.; Chen, X.; Cao, C. Impact of quality management on green innovation. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 170, 462–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina-Mijangos, R.; Ajour, S.; Zein, E.; Guerrero-García-Rojas, H.; Seguí-Amórtegui, L. The economic assessment of the environmental and social impacts generated by a light packaging and bulky waste sorting and treatment facility in Spain: A circular economy example. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2021, 33, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sträter, K.F.; Rhein, S. Plastic packaging: Are German retailers on the way towards a circular economy? Companies’ strategies and perspectives on consumers. GAIA-Ecol. Perspect. Sci. Soc. 2023, 32, 241–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matyi, H.; Tamás, P. An Innovative Framework for Quality Assurance in Logistics Packaging. Logistics 2023, 7, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulami, A.P.N.; Murayama, T.; Nishikizawa, S. Promotion of Producer Contribution to Solve Packaging Waste Issues—Viewpoints of Waste Bank Members in the Bandung Area, Indonesia. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Civancik-Uslu, D.; Puig, R.; Voigt, S.; Walter, D.; Fullana-I-Palmer, P. Improving the production chain with LCA and eco-design: Application to cosmetic packaging. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 151, 104475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poltronieri, C.F.; Gerolamo, M.C.; Carpinetti, L.C.R. Integrated Management Systems: Literature Review and Proposal of Instrument for Integration Assessment. Glob. J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2015, 27–34. Available online: https://repositorio.usp.br/directbitstream/87615a84-5c41-405b-8b65-fdadf1c3a1e8/%5BArt%20per%5D%20Poltronieri_Int (accessed on 11 December 2025).

- Casarejos, F.; Bastos, C.R.; Rufin, C.; Frota, M.N. Rethinking packaging production and consumption vis-a-vis circular economy: A case study of compostable cassava starch-based material. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 201, 1019–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vegter, D.; Van Hillegersberg, J.; Olthaar, M. Supply chains in circular business models: Processes and performance objectives. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 162, 105046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, C.; Loubet, P.; da Costa, T.P.; Quinteiro, P.; Laso, J.; de Sousa, D.B.; Cooney, R.; Mellett, S.; Sonnemann, G.; Rodríguez, C.J.; et al. Packaging environmental impact on seafood supply chains: A review of life cycle assessment studies. J. Ind. Ecol. 2022, 26, 1961–1978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansilla-Obando, K.; Llanos, G.; Gómez-Sotta, E.; Buchuk, P.; Ortiz, F.; Aguirre, M.; Ahumada, F. Eco-Innovation in the Food Industry: Exploring Consumer Motivations in an Emerging Market. Foods 2024, 13, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant, C.J. We Can’t Keep Meating Like This: Attitudes towards Vegetarian and Vegan Diets in the United Kingdom. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tencati, A.; Pogutz, S.; Moda, B.; Brambilla, M.; Cacia, C. Prevention policies addressing packaging and packaging waste: Some emerging trends. Waste Manag. 2016, 56, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Wang, J.; Chen, R.; Xi, Y.; Liu, S.Q.; Wu, F.; Masoud, M.; Wu, X. Innovation-driven industrial green development: The moderating role of regional factors. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 222, 344–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allacker, K.; Mathieux, F.; Pennington, D.; Pant, R. The search for an appropriate end-of-life formula for the purpose of the European Commission Environmental Footprint initiative. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2017, 22, 1441–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, T.; Chirla, S.R.; Singla, N.; Gupta, L. Product Packaging by E-commerce Platforms: Impact of COVID-19 and Proposal for Circular Model to Reduce the Demand of Virgin Packaging. Circ. Econ. Sustain. 2023, 3, 1255–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Escursell, S.; Llorach-Massana, P.; Roncero, M.B. Sustainability in e-commerce packaging: A review. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 280, 124314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jang, Y.; Kim, K.N.; Woo, J. Post-consumer plastic packaging waste from online food delivery services in South Korea. Waste Manag. 2023, 156, 177–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guarnieri, P.; Cerqueira-Streit, J.A.; Batista, L.C. Reverse logistics and the sectoral agreement of packaging industry in Brazil towards a transition to circular economy. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 153, 104541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trivellas, P.; Malindretos, G.; Reklitis, P. Implications of Green Logistics Management on Sustainable Business and Supply Chain Performance: Evidence from a Survey in the Greek Agri-Food Sector. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.S.; Hung, S.T.; Wang, T.Y.; Huang, A.F.; Liao, Y.W. The influence of excessive product packaging on green brand attachment: The mediation roles of green brand attitude and green brand image. Sustainability 2017, 9, 654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monnot, E.; Reniou, F.; Parguel, B.; Elgaaied-Gambier, L. ‘Thinking Outside the Packaging Box’: Should Brands Consider Store Shelf Context When Eliminating Overpackaging? J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 154, 355–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar Pani, S.; Pathak, A.A. Managing plastic packaging waste in emerging economies: The case of EPR in India. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 288, 112405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walls, M. Extended Producer Responsibility and Product Design Economic Theory and Selected Case Studies Extended Producer Responsibility and Product Design: Economic Theory and Selected Case Studies. Available online: https://www.rff.org (accessed on 5 October 2023).

- Pouikli, K. Concretising the role of extended producer responsibility in European Union waste law and policy through the lens of the circular economy. ERA Forum 2020, 20, 491–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compagnoni, M. Is Extended Producer Responsibility living up to expectations? A systematic literature review focusing on electronic waste. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 367, 133101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maitre-Ekern, E. Re-thinking producer responsibility for a sustainable circular economy from extended producer responsibility to pre-market producer responsibility. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 286, 125454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diggle, A.; Walker, T.R. Implementation of harmonized Extended Producer Responsibility strategies to incentivize recovery of single-use plastic packaging waste in Canada. Waste Manag. 2020, 110, 20–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muranko, Ż.; Tassell, C.; van der Laan, A.Z.; Aurisicchio, M. Characterisation and Environmental Value Proposition of Reuse Models for Fast-Moving Consumer Goods: Reusable Packaging and Products. Sustainability 2021, 13, 26091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatt, I.J.; Refalo, P. Reusability and recyclability of plastic cosmetic packaging: A life cycle assessment. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. Adv. 2022, 15, 200098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauer, E.; Wohner, B.; Heinrich, V.; Tacker, M. Assessing the Environmental Sustainability of Food Packaging: An Extended Life Cycle Assessment including Packaging-Related Food Losses and Waste and Circularity Assessment. Sustainability 2019, 11, 925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Q.; Yang, L.; Wei, F.; Chen, Y.; Li, J. Is reusable packaging an environmentally friendly alternative to the single-use plastic bag? A case study of express delivery packaging in China. Conserv. Recycl. 2023, 190, 106863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Canio, F. Consumer willingness to pay more for pro-environmental packages: The moderating role of familiarity. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 339, 117828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.T.; Chiang, C.W.; Cai, J.N.; Chang, H.Y.; Ku, Y.N.; Schneider, F. Evaluating the waste and CO2 reduction potential of packaging by reuse model in supermarkets in Taiwan. Waste Manag. 2023, 160, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruggerio, C.A. Sustainability and sustainable development: A review of principles and definitions. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 786, 147481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, A.; Seuring, S. Digital product passport for sustainable and circular supply chain management: A structured review of use cases. Int. J. Logist. Res. Appl. 2024, 27, 2513–2540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beswick-Parsons, R.; Jackson, P.; Evans, D.M. Understanding national variations in reusable packaging: Commercial drivers, regulatory factors, and provisioning systems. Geoforum 2023, 145, 103844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnusdei, G.P.; Gnoni, M.G.; Sgarbossa, F. Are deposit-refund systems effective in managing glass packaging? State of the art and future directions in Europe. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 851, 158256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kazancoglu, Y.; Ada, E.; Ozbiltekin-Pala, M.; As¸kın, R.; Uzel, A. In the nexus of sustainability, circular economy and food industry: Circular food package design. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 415, 137778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellsworth-Krebs, K.; Rampen, C.; Rogers, E.; Dudley, L.; Wishart, L. Sustainable Production and Consumption Circular economy infrastructure: Why we need track and trace for reusable packaging. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2022, 29, 249–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, G.; Styles, D.; Lens, P.N.L. Environmental performance comparison of bioplastics and petrochemical plastics: A review of life cycle assessment (LCA) methodological decisions. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 168, 105451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedrich, K.; Fritz, T.; Koinig, G.; Pomberger, R.; Vollprecht, D. Assessment of technological developments in data analytics for sensor-based and robot sorting plants based on maturity levels to improve austrian waste sorting plants. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gastaldi, E.; Buendia, F.; Greuet, P.; Bouchou, Z.B.; Benihya, A.; Cesar, G.; Domenek, S. Degradation and environmental assessment of compostable packaging mixed with biowaste in full-scale industrial composting conditions. Bioresour. Technol. 2024, 400, 130670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojnowska-Baryła, I.; Kulikowska, D.; Bernat, K. Effect of Bio-Based Products on Waste Management. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakadellis, S.; Lee, P.H.; Harris, Z.M. Two Birds with One Stone: Bioplastics and Food Waste Anaerobic Co-Digestion. Environments 2022, 9, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabarzare, N.; Rasti-Barzoki, M. A game theoretic approach for pricing and determining quality level through coordination contracts in a dual-channel supply chain including manufacturer and packaging company. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2020, 221, 107480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooque, M.; Zhang, A.; Thürer, M.; Qu, T.; Huisingh, D. Circular supply chain management: A definition and structured literature review. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 228, 882–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Liu, W.; Ye, S.; Batista, L. Packaging design for the circular economy: A systematic review. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2022, 32, 817–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahladakis, J.N.; Iacovidou, E. Closing the loop on plastic packaging materials: What is quality and how does it affect their circularity? Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 630, 1394–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardas, B.B.; Raut, R.D.; Narkhede, B. Identifying critical success factors to facilitate reusable plastic packaging towards sustainable supply chain management Sustainability Multi-criteria decision-making Lean production Interpretive structural modeling Total interpretive structural modeling. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 236, 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonopoulos, I.; Faraca, G.; Tonini, D. Recycling of post-consumer plastic packaging waste in the EU: Recovery rates, material flows, and barriers. Waste Manag. 2021, 126, 694–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panchal, R.; Singh, A.; Diwan, H. Economic potential of recycling e-waste in India and its impact on import of materials. Resour. Policy 2021, 74, 102264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firoozi Nejad, B.; Smyth, B.; Bolaji, I.; Mehta, N.; Billham, M.; Cunningham, E. Carbon and energy footprints of high-value food trays and lidding films made of common bio-based and conventional packaging materials. Clean. Environ. Syst. 2021, 3, 100058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyaert, C.; Fishel, Y.; Van Nueten, L.; Cencic, O.; Rechberger, H.; Billen, P.; Nimmegeers, P. Using Recyclable Materials Does Not Necessarily Lead to Recyclable Products: A Statistical Entropy-Based Recyclability Assessment of Deli Packaging. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 11719–11725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gianvincenzi, M.; Mosconi, E.M.; Marconi, M.; Tola, F. Battery Waste Management in Europe: Black Mass Hazardousness and Recycling Strategies in the Light of an Evolving Competitive Regulation. Recycling 2024, 9, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radusin, T.; Nilsen, J.; Larsen, S.; Annfinsen, S.; Waag, C.; Eikeland, M.S.; Pettersen, M.K.; Fredriksen, S.B. Use of recycled materials as mid layer in three layered structures-new possibility in design for recycling. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 259, 120876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Production Capacities of Bioplastics 2018–2024 Global Production Capacities of Bioplastics 2019 (by Material Type). Available online: http://www.european-bioplastics.org/news/publications/ (accessed on 11 December 2025).

- Sondh, S.; Upadhyay, D.S.; Patel, S.; Patel, R.N. Strategic approach towards sustainability by promoting circular economy-based municipal solid waste management system—A review. Sustain. Chem. Pharm. 2024, 37, 101337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazulytė, I.; Kruopienė, J. Production of packaging from recycled materials: Challenges related to hazardous substances. Environ. Res. Eng. Manag. 2018, 74, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boesen, S.; Bey, N.; Niero, M. Environmental sustainability of liquid food packaging: Is there a gap between Danish consumers’ perception and learnings from life cycle assessment? J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 210, 1193–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera, A.; Acosta-Dacal, A.; Luzardo, O.P.; Martínez, I.; Rapp, J.; Reinold, S.; Montesdeoca-Esponda, S.; Montero, D.; Gómez, M. Bioaccumulation of additives and chemical contaminants from environmental microplastics in European seabass (Dicentrarchus labrax). Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 822, 153396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niero, M. Implementation of the European Union’s packaging and packaging waste regulation: A decision support framework combining quantitative environmental sustainability assessment methods and socio-technical approaches. Clean Waste Syst. 2023, 6, 100112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.H.; Hung, P.; Ma, H.W. Integrating circular business models and development tools in the circular economy transition process: A firm-level framework. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2020, 29, 1887–1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lifset, R.; Kalimo, H.; Jukka, A.; Kautto, P.; Miettinen, M. Restoring the incentives for eco-design in extended producer responsibility: The challenges for eco-modulation. Waste Manag. 2023, 168, 189–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinhorst, J.; Beyerl, K. First reduce and reuse, then recycle! Enabling consumers to tackle the plastic crisis—Qualitative expert interviews in Germany. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 313, 127782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrmann, C.; Rhein, S.; Sträter, K.F. Consumers’ sustainability-related perception of and willingness-to-pay for food packaging alternatives. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2022, 181, 106219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragaert, K.; Delva, L.; Van Geem, K. Mechanical and chemical recycling of solid plastic waste. Waste Manag. 2017, 69, 24–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallick, P.K.; Salling, K.B.; Pigosso, D.C.A.; McAloone, T.C. Designing and operationalising extended producer responsibility under the EU Green Deal. Environ. Chall. 2024, 16, 100977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilkes-Hoffman, L.; Ashworth, P.; Laycock, B.; Pratt, S.; Lant, P. Public attitudes towards bioplastics—Knowledge, perception and end-of-life management. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 151, 104479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Extended Producer Responsibility: Basic Facts and Key Principle. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/content/dam/oecd/en/publications/reports/2024/04/extended-producer-responsibility_4274765d/67587b0b-en.pdf (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- Dörnyei, K.R.; Uysal-Unalan, I.; Krauter, V.; Weinrich, R.; Incarnato, L.; Karlovits, I.; Colelli, G.; Chrysochou, P.; Fenech, M.C.; Pettersen, M.K.; et al. Sustainable food packaging: An updated definition following a holistic approach. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2023, 7, 1119052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera Huerta, A.; Sidorczuk-Pietraszko, E.; Piontek, W.; Larsson, A. Are Deposit–Return Schemes an Optimal Solution for Beverage Container Collection in the European Union? An Evidence Review. Sustainability 2025, 17, 8791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picuno, C.; Gerassimidou, S.; You, W.; Martin, O.; Iacovidou, E. The potential of Deposit Refund Systems in closing the plastic beverage bottle loop: A review. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2025, 212, 107962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, H.; Keane, K.; McGillivray, L.; Akhtar-Khavari, A.; Chambers, L.; Barner-Kowollik, C.; Lauchs, M.; Blinco, J. Reforming plastic packaging regulation: Outcomes from stakeholder interviews and regulatory analysis. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2025, 54, 52–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammoud, R.; Massoud, M.A.; Chalak, A.; Abiad, M.G. Exploring the feasibility of extended producer responsibility for efficient waste management in Lebanon. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 15444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Context | To support the European Union’s transition towards a circular economy, the packaging sector must advance in terms of technology, innovation and alignment with regulatory frameworks. From a policy perspective, the European Commission has introduced several legislative tools, including the new Regulation that aimed at defining eco-design requirements for sustainable products. |

| Input | To contribute to the objectives set forth in the Regulation, a SLR was conducted. The focus is on packaging and the five priority areas identified within the legislative framework. |

| Mechanism | In order to interpret the aims of the Regulation, this paper maps academic and market knowledge across the targeted intervention areas, considering technological trends, policy developments and economic drivers. This enables a structured analysis of the state of the art in relation to regulatory ambitions. |

| Outcome | By evaluating the quality and focus of the state of the art, this study identifies both gaps and opportunities within the literature that relate to the goals of the Regulation. This evidence base can inform future scientific research and help align academic output with European circular economy targets. |

| N | Area PPWR | Searching String | Rationale | Scopus | ScienceDirect |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Circular Economy Principles in Packaging | (“circular economy” OR CE) AND (packaging) | Includes different terms related to eco-design and emphasizes design strategies that align with sustainability. | 2829 | 353 |

| 2 | Eco-design and Material Efficiency | (“eco-design” OR ecodesign) AND (packaging) | Includes different terms related to eco-design and emphasizes design strategies that are in line with sustainability. | 211 | 67 |

| 3 | Recyclability | (“recyclability” OR “recycling performance” OR “recyclable materials” OR recycle) AND (packaging) | Includes performance metrics and research on design for recyclability. | 1022 | 587 |

| 4 | Compostable and Biodegradable Packaging | (“compostable packaging” OR “biodegradable packaging” OR compostability) AND (packaging) | Includes all relevant terminology related to compostable materials. | 462 | 211 |

| 5 | Supply Chain Optimization | (“supply chain” OR “value chain” OR “value supply chain”) AND (sustainability OR sustainable) AND (packaging) | Includes research on logistics, supply chain efficiency, and sustainable management in the packaging sector. | 2533 | 375 |

| 6 | Waste Prevention & Minimization | (“waste prevention” OR “waste reduction” OR “waste minimization”) AND (packaging) | Includes key synonyms for reduction strategies that align with the focus of PPWR on upstream interventions. | 402 | 152 |

| 7 | Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) | (“extended producer responsibility” OR EPR) AND (packaging) | Targets policy-related and governance-focused research. Explicit and acronym-inclusive. | 268 | 112 |

| 8 | Reusable Packaging Systems | (“reusable packaging” OR “multi-use packaging” OR “returnable container *” OR “reusable container *” OR reuse) AND (packaging) | Includes literature focused on logistics and reuse systems. | 906 | 282 |

| 9 | Recycled Content in Packaging | (“recycled content” OR “post-consumer recycl *” OR “secondary raw material *” OR SRM OR “second material *”) AND (packaging) | Wildcard for “recyclables/recycled/recycling”; emphasizes the integration of materials into production processes. | 206 | 60 |

| 10 | Packaging Policy and Regulation | (“packaging regulation” OR “packaging directive” OR “PPWR” OR “EU packaging law”) AND (packaging) | Includes formal names of regulatory instruments and broader legal terminology. | 114 | 36 |

| Eligibility Criteria | Decision |

|---|---|

| The chosen keywords exist at least in the title or abstract section of the document | Inclusion |

| The document is published in a peer-reviewed scientific journal | Inclusion |

| The document is written in the English language | Inclusion |

| The paper is duplicated within the search documents | Exclusion |

| The document is published before 2015 | Exclusion |

| Intervention Areas | Packaging Regulation | SLR Inclusion Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Waste Prevention | Ecodesign; Material Efficiency and minimization; Harmonized labelling; Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR); Quantitative Waste Reduction Targets. | The paper analyses the state of the art in waste prevention, highlighting strategies such as extended producer responsibility (EPR), eco-design in packaging, harmonization of labelling, improved material efficiency, and waste minimization, along with specific quantitative waste reduction targets. |

| Recyclability | Mandatory design standards for recyclable packaging; Recycling performance grades and minimum thresholds; Reduction in material complexity to enhance recyclability. | Papers should focus on evaluating technologies, standards, or methods aimed at enhancing packaging recyclability. This includes measures such as the use of mono-materials, development of recyclability performance metrics, and advancements in material recovery processes. |

| Compostable Packaging | Criteria for defining compostable materials. Mandatory compostability standards for specific applications. Harmonized labelling for compostable packaging. | Papers that discuss the role of compostable packaging in reducing contamination in recycling streams, examining technological, environmental, or policy perspectives. |

| Reusable Packaging | Standardization of reusable packaging systems

| The literature must explore reuse systems, their environmental impact, operational frameworks, or the feasibility of scaling reusable packaging systems across various sectors. |

| Recycled Content | Mandatory targets for integrating recycled content into packaging materials; Verification and reporting mechanisms for recycled content compliance. | This includes studies that examine the use of recycled materials in packaging, focusing on the technical, economic, and policy-related challenges and solutions associated with this integration. |

| Journal | N |

|---|---|

| Journal of Cleaner Production | 18 |

| Sustainability | 13 |

| Waste Management | 8 |

| Science of the Total Environment | 5 |

| Article | Intervention Areas | Key Pillars | LCA | Interview | Survey | Material Analysis | Comparative Analysis | Econometric Tools | Policy Evaluation | Literature Review | SLCA | Economic Analysis | Supply Chain Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [48] | Compostable Packaging | Enhance Packaging Development Process | x | x | |||||||||

| [93] | Compostable Packaging | Minimise Environmental Impact | x | x | |||||||||

| [82] | Compostable Packaging | Improve Supply Chain Efficiency | x | x | |||||||||

| [83] | Compostable Packaging | Minimise Environmental Impact | x | x | x | ||||||||

| [3] | Compostable Packaging | Improve Supply Chain Efficiency | x | x | x | ||||||||

| [23] | Compostable Packaging | Enhance Packaging Development Process | x | x | x | ||||||||

| [86] | Compostable Packaging | Improve Supply Chain Efficiency | x | x | x | ||||||||

| [85] | Compostable Packaging | Minimise Environmental Impact | x | x | |||||||||

| [36] | Compostable Packaging | Enhance Packaging Development Process | x | x | x | ||||||||

| [12] | Compostable Packaging | Enhance Packaging Development Process | x | x | x | ||||||||

| [9] | Compostable Packaging | Enhance Packaging Development Process | x | x | |||||||||

| [84] | Compostable Packaging | Enhance Packaging Development Process | x | x | x | ||||||||

| [55] | Recyclability | Minimise Environmental Impact | x | x | x | ||||||||

| [91] | Recyclability | Minimise Environmental Impact | x | x | x | ||||||||

| [81] | Recyclability | Minimise Environmental Impact | x | x | |||||||||

| [61] | Recyclability | Improve Supply Chain Efficiency | |||||||||||

| [46] | Recyclability | Minimise Environmental Impact | x | x | |||||||||

| [87] | Recyclability | Improve Supply Chain Efficiency | x | x | x | x | |||||||

| [40] | Recyclability | Improve Supply Chain Efficiency | x | x | |||||||||

| [89] | Recyclability | Enhance Packaging Development Process | x | x | x | x | |||||||

| [79] | Recyclability | Enhance Packaging Development Process | x | x | |||||||||

| [42] | Recyclability | Minimise Environmental Impact | x | x | x | ||||||||

| [92] | Recyclability | Improve Supply Chain Efficiency | x | x | |||||||||

| [71] | Recyclability | Minimise Environmental Impact | x | ||||||||||

| [15] | Recyclability | Improve Supply Chain Efficiency | x | x | |||||||||

| [10] | Recyclability | Minimise Environmental Impact | x | x | |||||||||

| [82] | Recycled Content | Implicate Regulatory Compliance | x | x | |||||||||

| [11] | Recycled Content | Implicate Regulatory Compliance | x | x | x | x | |||||||

| [100] | Recycled Content | Implicate Regulatory Compliance | x | x | x | ||||||||

| [94] | Recycled Content | Implicate Regulatory Compliance | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||

| [33] | Recycled Content | Enhance Packaging Development Process | x | ||||||||||

| [96] | Recycled Content | Improve Supply Chain Efficiency | x | x | x | ||||||||

| [37] | Recycled Content | Enhance Packaging Development Process | x | x | |||||||||

| [15] | Recycled Content | Improve Supply Chain Efficiency | x | x | |||||||||

| [13] | Recycled Content | Implicate Regulatory Compliance | x | x | |||||||||

| [24] | Recycled Content | Improve Supply Chain Efficiency | x | x | |||||||||

| [78] | Reusability | Implicate Regulatory Compliance | x | x | x | x | |||||||

| [50]. | Reusability | Improve Supply Chain Efficiency | x | x | |||||||||

| [56] | Reusability | Improve Supply Chain Efficiency | x | x | x | ||||||||

| [30] | Reusability | Improve Supply Chain Efficiency | x | x | |||||||||

| [77] | Reusability | Implicate Regulatory Compliance | x | x | |||||||||

| [4] | Reusability | Implicate Regulatory Compliance | x | x | x | ||||||||

| [68] | Reusability | Implicate Regulatory Compliance | x | x | x | x | |||||||

| [80] | Reusability | Improve Supply Chain Efficiency | x | x | x | ||||||||

| [57] | Reusability | Minimise Environmental Impact | x | x | |||||||||

| [90] | Reusability | Improve Supply Chain Efficiency | x | x | x | ||||||||

| [70] | Reusability | Enhance Packaging Development Process | x | x | x | ||||||||

| [59] | Reusability | Improve Supply Chain Efficiency | x | x | x | ||||||||

| [58] | Reusability | Minimise Environmental Impact | x | x | |||||||||

| [74] | Reusability | Improve Supply Chain Efficiency | x | x | |||||||||

| [44] | Reusability | Improve Supply Chain Efficiency | x | x | x | ||||||||

| [7] | Reusability | Enhance Packaging Development Process | x | x | x | ||||||||

| [69] | Reusability | Improve Supply Chain Efficiency | x | x | x | x | |||||||

| [72] | Reusability | Minimise Environmental Impact | x | x | x | ||||||||

| [88] | Reusability | Improve Supply Chain Efficiency | x | ||||||||||

| [38] | Waste Prevention | Minimise Environmental Impact | x | x | |||||||||

| [35] | Waste Prevention | Implicate Regulatory Compliance | x | x | |||||||||

| [6] | Waste Prevention | Enhance Packaging Development Process | x | x | x | x | |||||||

| [52] | Waste Prevention | Minimises Environmental Impact | x | x | x | ||||||||

| [32] | Waste Prevention | Implicate Regulatory Compliance | x | x | x | ||||||||

| [34] | Waste Prevention | Enhance Packaging Development Process | x | x | |||||||||

| [61] | Waste Prevention | Enhance Packaging Development Process | x | x | x | ||||||||

| [39] | Waste Prevention | Minimise Environmental Impact | x | x | x | x | |||||||

| [66] | Waste Prevention | Implicate Regulatory Compliance | x | x | x | ||||||||

| [73] | Waste Prevention | Enhance Packaging Development Process | x | x | |||||||||

| [68] | Waste Prevention | Implicate Regulatory Compliance | x | x | x | ||||||||

| [62] | Waste Prevention | Enhance Packaging Development Process | x | x | |||||||||

| [67] | Waste Prevention | Implicate Regulatory Compliance | x | x | |||||||||

| [16] | Waste Prevention | Enhance Packaging Development Process | x | x | |||||||||

| [8] | Waste Prevention | Enhance Packaging Development Process | x | x | x | ||||||||

| [101] | Waste Prevention | Minimise Environmental Impact | x | x | |||||||||

| [102] | Waste Prevention | Enhance Packaging Development Process | x | x | |||||||||

| [31] | Waste Prevention | Minimise Environmental Impact | x | x | |||||||||

| [2] | Waste Prevention | Minimise Environmental Impact | x | ||||||||||

| [22] | Waste Prevention | Implicate Regulatory Compliance | x | x | x | ||||||||

| [63] | Waste Prevention | Implicate Regulatory Compliance | x | x | x | ||||||||

| [54] | Waste Prevention | Minimise Environmental Impact | x | x | |||||||||

| [103] | Waste Prevention | Implicate Regulatory Compliance | x | x | |||||||||

| [51] | Waste Prevention | Minimise Environmental Impact | x | x | |||||||||

| [28] | Waste Prevention | Enhance Packaging Development Process | x | x | x | ||||||||

| [62] | Waste Prevention | Minimise Environmental Impact | x | x | |||||||||

| [104] | Waste Prevention | Implicate Regulatory Compliance | x | ||||||||||

| [29] | Waste Prevention | Enhance Packaging Development Process | x | x | x | ||||||||

| [27] | Waste Prevention | Minimise Environmental Impact | x | x | |||||||||

| [47] | Waste Prevention | Implicate Regulatory Compliance | x | x | |||||||||

| [65] | Waste Prevention | Implicate Regulatory Compliance | x | x | |||||||||

| [14] | Waste Prevention | Implicate Regulatory Compliance | x | x | |||||||||

| [75] | Waste Prevention | Minimise Environmental Impact | x | x | |||||||||

| [45] | Waste Prevention | Implicate Regulatory Compliance | x | x | |||||||||

| [53] | Waste Prevention | Implicate Regulatory Compliance | x | x | x | ||||||||

| [49] | Waste Prevention | Minimise Environmental Impact | x | x | |||||||||

| [64] | Waste Prevention | Implicate Regulatory Compliance | x | x | x |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Tarantino, M.; Mosconi, E.M.; Tola, F.; Gianvincenzi, M.; Delussu, A.M. A Comprehensive and Multidisciplinary Framework for Advancing Circular Economy Practices in the Packaging Sector: A Systematic Literature Review on Critical Factors. Sustainability 2026, 18, 192. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010192

Tarantino M, Mosconi EM, Tola F, Gianvincenzi M, Delussu AM. A Comprehensive and Multidisciplinary Framework for Advancing Circular Economy Practices in the Packaging Sector: A Systematic Literature Review on Critical Factors. Sustainability. 2026; 18(1):192. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010192

Chicago/Turabian StyleTarantino, Mariarita, Enrico Maria Mosconi, Francesco Tola, Mattia Gianvincenzi, and Anna Maria Delussu. 2026. "A Comprehensive and Multidisciplinary Framework for Advancing Circular Economy Practices in the Packaging Sector: A Systematic Literature Review on Critical Factors" Sustainability 18, no. 1: 192. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010192

APA StyleTarantino, M., Mosconi, E. M., Tola, F., Gianvincenzi, M., & Delussu, A. M. (2026). A Comprehensive and Multidisciplinary Framework for Advancing Circular Economy Practices in the Packaging Sector: A Systematic Literature Review on Critical Factors. Sustainability, 18(1), 192. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010192