Abstract

This study investigates the impact of environmental judicial reform on corporate sustainable development, specifically focusing on the establishment of Environmental Protection Courts (EPCs) in China. Leveraging a quasi-natural experiment created by the staggered rollout of EPCs, we employ a difference-in-differences (DID) model based on a comprehensive dataset of Chinese A-share listed companies from 2009 to 2024. The empirical results demonstrate that the establishment of EPCs significantly enhances corporate ESG performance. This promoting effect remains robust across a series of validity tests, including alternative ESG measures and green patent indicators. Mechanism analysis reveals a dual channel: externally, the reform intensifies local governmental supervision and penalty risks; internally, it elevates managerial green cognition and fosters substantive green investment. Heterogeneity analysis further indicates that the effect is more pronounced in regions with stronger judicial foundations and, notably, for non-heavy-polluting firms sensitive to reputational risks. This paper contributes to the literature by unpacking the “black box” of the judicial transmission mechanism and providing causal evidence of how specialized environmental justice shapes corporate sustainability strategies.

1. Introduction

Globally, the dominant corporate logic is transitioning from maximizing shareholder value to a broader prioritization of stakeholder interests [1]. Within this new paradigm, corporate value is no longer measured solely by financial returns, but by a more holistic and sustainable yardstick encompassing environmental, social, and governance (ESG) performance. This shift has ignited a critical debate among scholars and policymakers on how to design effective institutional arrangements that can steer firms towards sustainable development [2,3]. In China, this global trend converges with a pressing national strategic priority: the pursuit of “high-quality development” and ecological civilization. Consequently, identifying the key institutional drivers of corporate ESG transformation in the Chinese context has emerged as a research imperative of significant theoretical and practical importance.

To date, the literature on environmental governance has largely focused on two primary mechanisms: administrative regulations, such as government-led environmental inspections, and market-based instruments, like emissions trading schemes [4,5]. While these instruments have shown varying degrees of success, administrative approaches often grapple with challenges like local protectionism and information asymmetry, whereas market mechanisms require a high level of market maturity to function effectively [6,7]. This has led scholars to increasingly recognize the judiciary as a crucial, yet comparatively under-explored, “last line of defense” in environmental governance. A professional and independent judicial system, in theory, can provide a powerful coercive force to ensure compliance and deter misconduct. It is against this backdrop that China initiated a pivotal environmental judicial reform in 2007, marked by the establishment of specialized Environmental Protection Courts (EPCs). This reform provides a unique quasi-natural experimental setting to examine a fundamental question: Can judicial specialization serve as an effective catalyst for corporate sustainable development?

Recent empirical studies have started to examine how this judicial innovation reshapes corporate behavior [8,9]. More recently, scholars have started to link this judicial pressure to broader corporate sustainability outcomes, providing initial evidence that EPCs can promote overall ESG ratings [10,11]. Nevertheless, knowledge regarding the specific transmission mechanisms remains limited. First, the existing literature often treats the firm’s response as a “black box,” [12] without fully unpacking the internal cognitive and behavioral pathways through which external judicial pressure is translated into substantive action. Second, it remains unclear whether this pressure leads to genuine, substantive improvements or merely symbolic compliance, a key concern in the context of corporate “greenwashing.” Finally, the boundary conditions under which this judicial intervention is most effective are not yet fully understood.

To fill these voids, we leverage a panel of A-share firms listed between 2009 and 2024. Adopting a difference-in-differences (DID) strategy, we rigorous quantify the causal effect of EPCs on corporate ESG outcomes. Going beyond existing work, our study makes three primary contributions. First, we extend the observation window significantly to offer robust causal evidence regarding the reform’s long-term efficacy. Second, we unpack the underlying mechanisms, revealing a dual channel of external pressure and internal response. This offers a much clearer picture of the causal pathway from judicial intervention to sustainability outcomes. Third, our heterogeneity analysis uncovers that the judicial effect is not uniform; it is amplified in regions with strong legal foundations and, notably, among firms in light-polluting sectors sensitive to reputation.

Our findings are compelling. The establishment of EPCs significantly enhances corporate ESG performance, a result that is robust to a battery of tests. This effect is driven by the synergistic interplay of heightened external oversight and proactive internal strategic adaptation. These insights deepen the theoretical comprehension of judicial intervention and offer actionable guidance for policymakers and corporate leaders managing green transitions.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 outlines the institutional background and develops the research hypotheses. Section 3 describes the research design, including sample selection, variable definitions, and the empirical model. Section 4 presents the empirical results, including baseline regression, robustness checks, heterogeneity analysis, and mechanism tests. Section 5 discusses the implications of the findings and provides policy recommendations. Finally, Section 6 concludes the study.

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

The academic debate regarding the economic consequences of environmental regulation has long centered on two opposing views. One is the “Compliance Cost Hypothesis,” which suggests that strict regulations impose additional costs on firms, crowding out productive investments and harming competitiveness [13]. The other is the celebrated “Porter Hypothesis,” which argues that well-designed environmental regulations can trigger innovation offsets, leading to a “win-win” scenario for both environmental protection and corporate competitiveness [14]. While early studies focused primarily on administrative regulations, recent literature has begun to examine the unique role of the judiciary. However, a comprehensive framework linking specialized judicial institutions to corporate micro-level sustainability strategies remains to be fully developed. This section reviews relevant theories and proposes a hypothesis framework to address this gap.

2.1. Environmental Judicial Reform and Corporate ESG Performance

The establishment of specialized EPCs represents a significant enhancement of the formal institutional environment for corporate sustainability. We draw upon two foundational theories, deterrence theory and legitimacy theory, to argue that this judicial reform will positively influence corporate ESG performance.

From the perspective of deterrence theory, the effectiveness of any regulation hinges on the certainty, severity, and celerity of punishment for non-compliance [15]. The creation of EPCs strengthens the environmental rule of law in all three aspects. First, the specialization of judges and the establishment of dedicated judicial procedures increase the professional capacity to adjudicate complex environmental cases, thereby raising the certainty that corporate environmental violations will be accurately identified and prosecuted [16,17]. Second, the authority vested in these courts to impose significant penalties, including substantial fines and injunctive relief, increases the severity of sanctions. This heightened legal risk fundamentally alters a firm’s cost–benefit analysis, making proactive compliance and investment in ESG a more economically rational choice than facing potential litigation [18,19].

From the perspective of legitimacy theory, firms are not merely profit-seeking entities but also social actors that require a “social license to operate.” They must conform to the norms, values, and expectations of the broader society to maintain their legitimacy and ensure long-term survival [20,21]. The establishment of EPCs sends a powerful institutional signal that society’s expectations regarding corporate environmental responsibility have been formally elevated. In this context, strong ESG performance becomes a critical means for firms to demonstrate their alignment with these evolving societal values and to secure their “environmental legitimacy” [22]. Firms that fail to improve their ESG practices risk being perceived as illegitimate, which can lead to negative reactions from key stakeholders such as customers, employees, investors, and community groups [23,24].

Combining these two perspectives, the environmental judicial reform creates both a direct economic imperative (avoiding punishment) and a broader social imperative (maintaining legitimacy) for firms to improve their sustainability practices. Therefore, we propose our first hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

The establishment of EPCs is positively associated with corporate ESG performance.

2.2. The Mediating Role of External Pressures and Internal Responses

While H1 posits a direct link, we further argue that the effect of judicial reform on ESG performance is not monolithic but is transmitted through distinct external and internal channels.

First, we propose an external pressure channel. The activities of EPCs do not occur in a vacuum; they generate significant informational ripples that activate other monitoring and enforcement agents in the firm’s environment. Judicial rulings against polluters can trigger heightened scrutiny from local governments, compelling them to strengthen their own administrative oversight and enforcement intensity to align with the judiciary’s stance [25,26]. Simultaneously, these legal actions represent direct and tangible punitive threats to firms, increasing the financial and reputational costs associated with environmental malfeasance [27]. We thus expect the judicial reform to intensify both governmental and punitive pressures on firms.

Second, we propose an internal response channel, drawing on the attention-based view (ABV) of the firm [28]. The ABV posits that managerial attention is a scarce resource, and organizational actions are a function of where decision-makers focus their attention. The establishment of EPCs dramatically increases the salience of environmental issues, elevating them from a peripheral concern to a top-tier strategic priority. This shift in attention is expected to first manifest as a change in corporate green cognition, as managers are forced to process and internalize the heightened environmental risks and opportunities [29]. Subsequently, this cognitive reorientation will drive the allocation of organizational resources towards tangible actions, most notably through increased corporate green investment in pollution control technologies and sustainable production processes [30].

Based on this reasoning, we hypothesize that the effect of EPCs on ESG is mediated by these interconnected external and internal mechanisms. Therefore, we propose the following hypotheses concerning the causal pathways:

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

The establishment of EPCs promotes corporate ESG performance by intensifying external pressures, such as strengthening local government environmental governance and increasing environmental penalties.

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

The establishment of EPCs promotes corporate ESG performance by fostering internal responses, such as enhancing corporate green cognition and driving corporate green investment.

In summary, our theoretical framework posits that the establishment of EPCs serves as an exogenous regulatory shock. This shock influences corporate ESG performance through two distinct channels: an external channel characterized by intensified government supervision and penalty risks, and an internal channel driven by enhanced managerial green cognition and investment. Furthermore, this causal relationship is moderated by the regional judicial foundation and industry-specific characteristics.

3. Materials and Methods

This section details the quantitative methodological framework employed to test the proposed hypotheses. It is organized into three parts: First, we describe the sample selection process and data sources (Section 3.1). Second, we provide precise definitions and measurements for the dependent, independent, and control variables (Section 3.2). Third, we specify the Difference-in-Differences (DID) econometric model used for causal identification (Section 3.3).

3.1. Sample Selection and Data Sources

We selected our initial research cohort from the universe of A-share companies trading on the Shanghai and Shenzhen bourses, spanning the period 2009 through 2024. Given that the data availability for the most recent period (especially 2024) depends on the disclosure progress of listed companies, we constructed an unbalanced panel dataset for the analysis. This approach maximizes the use of available information while accounting for the varying reporting timelines of different firms. To construct a reliable dataset for our analysis, we followed a systematic data collection and cleaning procedure. All empirical analyses were processed using Stata (Version 17.0).

We obtained the core data for our key explanatory variable, the environmental judicial reform. Data regarding the establishment dates of intermediate-level EPCs were hand-collected and triangulated using two main channels: official judicial proclamations from local court portals and verified reports from major national and provincial news agencies. This meticulous process ensures the accuracy and timeliness of our treatment variable, which is crucial for the quasi-natural experimental design.

For the dependent variable, we utilized ESG scores extracted from the Huazheng ESG Rating system (available via Wind). As a premier evaluation framework in China, Huazheng provides extensive and consistent longitudinal data for A-share listed entities. All other firm-level financial and corporate governance data were retrieved from the China Stock Market & Accounting Research (CSMAR) Database, a leading data provider for scholarly research on Chinese firms [31,32]. Data cleaning followed standard protocols to ensure robustness: (1) Financial sector entities were omitted given their unique accounting standards; (2) Firms flagged as “ST or “*ST” were filtered out to exclude distressed assets; (3) Samples with incomplete data for key regressors were eliminated; and (4) Continuous variables were winsorized at the 1st and 99th percentiles to curb the influence of extreme values.

3.2. Variable Definitions

The primary outcome variable is the firm’s ESG performance (labeled ESG). Consistent with the mainstream literature, we utilize the Huazheng (Sino-Securities Index) ESG rating system [33,34,35]. This framework assesses firms across nine distinct grades, from C to AAA. To prepare the variable for quantitative analysis, we convert these categorical ratings into a numerical score, assigning a value of 1 to the lowest grade (C) and progressively higher integers up to 9 for the highest grade (AAA). Consequently, a larger ESG score signifies superior corporate ESG performance. To address data skewness, we apply a natural logarithmic transformation to the raw scores for regression analysis.

The focal independent variable, Law, captures the environmental judicial reform. Designed as the standard DID interaction term (Treat × Post), this binary indicator is assigned a value of 1 for firms located in cities with an operational EPC starting from the establishment year, and 0 otherwise.

Drawing upon established research in corporate finance and governance [36,37,38], we incorporate a comprehensive set of control variables to isolate the effect of the judicial reform from other confounding factors. We account for basic firm attributes, specifically firm size (Size) and age (Age), given that larger, older entities often command more resources for ESG initiatives. We also account for financial status through leverage (Lev) and profitability (ROA). To capture the influence of internal governance mechanisms, we include variables for CEO-chair duality (Dual), board size (Board), and board independence (Indep), as board structure is a critical determinant of corporate strategic decisions. Additionally, ownership nature is captured using a binary variable (SOE) to distinguish state-owned enterprises. This is crucial in the Chinese context, as SOEs may face different political pressures and corporate objectives that significantly influence their ESG strategies [39,40]. Finally, we control for business characteristics and growth potential through the intangible asset ratio (Intangible) and revenue growth (Growth) [41]. Table 1 outlines the detailed definitions for all variables.

Table 1.

Variable Definitions.

3.3. Model Specification

To quantify the causal effect of the judicial reform on corporate ESG outcomes, we utilize a difference-in-differences (DID) specification. The DID methodology is particularly well-suited for this research context as it can effectively mitigate potential endogeneity problems arising from omitted variables or selection bias [42]. By comparing the change in ESG performance of treated firms (those in cities with EPCs) to that of control firms (those in cities without EPCs) before and after the policy shock, the model can isolate the net effect of the reform [43].

Our baseline regression model is specified as follows:

In this equation, the subscript i denotes the firm and t denotes the year. ESGit represents the ESG performance. is our core treatment variable, and its coefficient, , captures the average treatment effect of the environmental judicial reform, which is the primary focus of our study. A significantly positive would lend strong support to our main hypothesis.

Controlsit is a vector of the control variables discussed previously. To further enhance the robustness of our model, we incorporate two-way fixed effects [44,45]. Here, denotes firm fixed effects, capturing time-invariant unobserved factors like corporate culture or inherent strategic focus. represents year fixed effects, which control for any macro-level shocks or time trends common to all firms in a given year, such as nationwide policy shifts or business cycles. is the idiosyncratic error term. Standard errors are clustered at the firm level to correct for potential heteroscedasticity and serial correlation [10,46].

4. Empirical Results and Analysis

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

Table 2 summarizes the descriptive statistics or the variables included in the study. The final dataset consists of a total of 49,609 observations at the firm-year level. The dependent variable, the natural logarithm of the ESG score, has a mean of 4.289 with a relatively small standard deviation of 0.076. This indicates that while there is variation in ESG performance across the sample, the majority of firms’ scores are clustered around the average level. Our core explanatory variable, Law has a mean of 0.467. This suggests that approximately 46.7% of the observations in our sample belong to the treatment group, providing a well-balanced dataset for the DID estimation.

Table 2.

Summary Statistics.

Regarding the control variables, the data exhibits significant variation across firms. The average value of Size stands at 22.180, implying that the sample is dominated by large-scale and mature enterprises. The average Lev is 41.6%, and the average ROA is 3.8%, both of which are consistent with typical performance levels of Chinese listed firms.

In terms of governance structure, the average Dual variable is 0.300, which means that CEO duality (where the CEO also serves as the board chair) occurs in approximately 30% of the sample. The average Board is 2.267, and the mean proportion of Indep is 38.3%, which is above the one-third regulatory minimum in China. An important ownership characteristic is captured by the SOE variable, which has a mean of 0.324, indicating that state-owned enterprises constitute roughly 32.4% of our sample. The distributions of other variables, including Intangible, Growth, and Age, are consistent with prior studies. In sum, these summary statistics provide a reliable basis for the econometric analysis that follows.

4.2. Baseline Regression Analysis

Table 3 reports the empirical findings from the baseline model examining how environmental judicial reform affects corporate ESG outcomes. To provide a comprehensive and robust picture, we build our model in a stepwise fashion.

Table 3.

Baseline regression.

Column (1) reports the result from a simple regression with only our core explanatory variable Law. The estimated coefficient is positively signed and significant at the 1% level, providing initial evidence of a constructive relationship between EPC implementation and firm-level ESG performance

Column (2) incorporates a complete set of firm-level controls. Although the coefficient of Law attenuates slightly to 0.007, it maintains high significance, implying that the observed effect is not merely a byproduct of firm attributes like size or leverage.

Column (3) adds both firm and year fixed effects. This represents our preferred specification as it accounts for unobserved time-invariant heterogeneity and common temporal shocks. Even under this stringent specification, the coefficient of Law remains positive and significant, lending stronger support to a causal interpretation.

Finally, Column (4) displays the results from the most rigorous specification, including all controls and two-way fixed effects. The coefficient of Law stands at 0.004. Economically speaking, this suggests that EPC establishment generates an average 0.4% improvement in ESG scores. This outcome offers compelling support for our central hypothesis, confirming that China’s judicial reform acts as a significant catalyst for enhancing corporate ESG performance. The consistent increase in the adjusted R-squared across the columns, from 0.5% in Column (1) to 41.3% in Column (4), further demonstrates the explanatory power of our full model.

4.3. Robustness Checks

To verify the validity and stability of our baseline results, we performed a battery of robustness tests. The first and most critical test for a DID design is the parallel trend assumption.

4.3.1. Alternative Dependent Variables

To verify that our results are not driven by the specific evaluation criteria of the Huazheng ESG rating system, we conducted robustness tests using three alternative indicators. The results are reported in Table 4.

Table 4.

Alternative Dependent Variables.

First, we utilized the SynTao Green Finance ESG ratings. Given that the SynTao dataset initiates in 2015, we converted its letter grades into numerical scores and took the natural logarithm for the 2015–2024 sub-sample. As shown in Column (1), the coefficient of Law remains significantly positive.

Second, to incorporate an international perspective, we employed the Bloomberg ESG disclosure scores. Based on data availability, the sample period for this test is 2009–2023. The results in Column (2) confirm that the promoting effect holds, validating our findings against international standards.

Third, to capture substantive environmental improvements and distinguish them from potential “greenwashing” in subjective ratings, we used the natural logarithm of total green patent applications as a proxy for corporate green innovation. Column (3) indicates a strong promoting effect, suggesting that EPCs drive tangible green outcomes.

In summary, regardless of the measurement method, data source, or sample period, the establishment of EPCs consistently promotes corporate sustainable development.

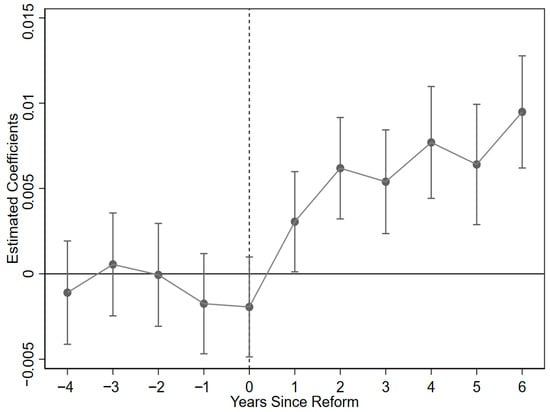

4.3.2. Parallel Trend Test

The validity of the DID design hinges on the parallel trend assumption, which posits that treated and control groups would have followed similar trajectories in the absence of the intervention. To validate this assumption, we employ an event study approach. We substitute the primary explanatory variable, Law, with a series of time-dummy variables denoting the years prior to and following the EPC inauguration. The model is specified as follows:

Here, is a series of dummy variables, where k indicates the number of years relative to the policy implementation (k = 0 for the implementation year). We set the period more than four years before the reform as the baseline group. The coefficients the dynamic effects of the reform over time.

To facilitate interpretation, the solid dots in Figure 1 denote the estimated coefficients , while the vertical bars represent the 90% confidence intervals and the dotted line marks the policy implementation; the crossing of the zero line by these intervals prior tothe reform year (k < 0) indicates the validity of the parallel trend. As depicted in the figure, all coefficients for the pre-reform periods (k = −4 to k = −1) are statistically insignificant and fluctuate around 0. The results reveal no statistically significant divergence in ESG trends between the two groups during the pre-reform period, thereby validating the parallel trend assumption.

Figure 1.

Parallel Trend Test.

Furthermore, the dynamic effects after the reform are clearly visible. The coefficient becomes positive from the first year after implementation (k = 1) and turns statistically significant from the second year (k = 2) onwards. The positive trend largely persists in the subsequent years, suggesting that the promotional effect of the environmental judicial reform on corporate ESG performance is not only significant but also sustainable over the long term. This dynamic pattern strongly reinforces the causal interpretation of our baseline results.

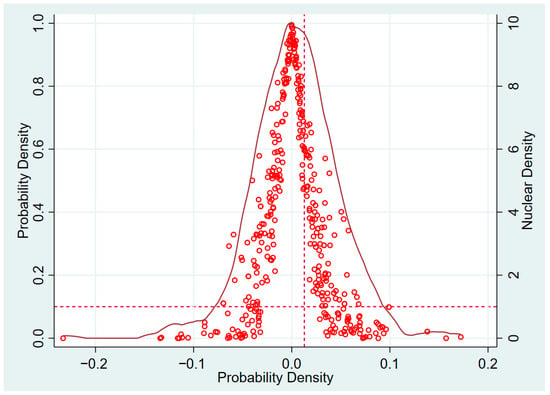

4.3.3. Placebo Test

To exclude the possibility that our findings are artifacts of unobserved confounders or random chance, we implemented a placebo test. Following the methodology proposed by prior literature, we construct a falsification test by randomly assigning the treatment status.

Specifically, we repeat the following procedure 500 times: we first randomly select a group of firms as the “pseudo” treatment group, and then we randomly assign a “pseudo” policy implementation year to each firm. Using this falsified treatment variable (did_placebo), we re-run our baseline regression model as specified in Column (4) of Table 3. If the effect captured by our true variable is genuine, the estimators derived from these randomly generated placebo variables should be statistically indistinguishable from zero.

Visually, Figure 2 shows that the placebo coefficients (represented by circles and the red curve) cluster around zero, whereas our actual estimated coefficient (the vertical dashed line) stands distinctively in the right tail, confirming that the result is an outlier rather than a random event. As is evident, the coefficients from the placebo tests are symmetrically distributed around 0, with a mean that is nearly 0. The vertical dashed line indicates our true baseline coefficient of 0.004 from Table 3. Our actual estimate is positioned at the extreme right tail of the placebo distribution, indicating that the baseline result is almost certainly not a random occurrence. Consequently, this test bolsters our confidence that the observed ESG improvement is causally linked to the environmental judicial reform.

Figure 2.

Placebo Test.

4.4. Heterogeneity Analysis

To examine the heterogeneous effects of the reform, we analyzed how the impact differs across various institutional environments and firm types. We conduct subgroup analyses based on the timing of broader national judicial reforms, the regional judicial environment, and industry-specific pollution levels. The results are presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

Heterogeneity analysis.

4.4.1. Heterogeneity Across Judicial Reform Periods

The trajectory of environmental governance in China has undergone shifts. Notably, the Supreme People’s Court’s creation of the Environmental and Resources Tribunal in 2014 represented a watershed moment, signaling a top-down enforcement push. To examine whether the effectiveness of municipal-level EPCs changed in this evolving context, we split the sample into two sub-periods: before and after 2014. The results in Columns (1) and (2) of Table 5 reveal that the Law coefficient becomes significantly positive only in the post-2014 era, while remaining insignificant in the earlier period. This temporal heterogeneity can be attributed to the “cumulative impact” of the judicial reform. In 2014, the Supreme People’s Court (SPC) established the Environmental Resources Trial Division, marking a pivotal “top-down” reinforcement of environmental justice. Before 2014, local EPCs operated with limited guidance and authority. The SPC’s reform in 2014 provided crucial institutional legitimacy, standardized adjudication guidelines, and stronger political backing for local courts. Consequently, the synergy between the central SPC reform and local EPC practices significantly amplified the judicial deterrence effect in the later period [47].

4.4.2. Heterogeneity Across Regions with Different Judicial Demonstration Status

The implementation and effectiveness of judicial reforms can be contingent on the local institutional capacity and environment. We identify a list of provinces and municipalities designated as “environmental judicial demonstration zones,” which are pioneers in judicial practice. We then test for heterogeneous effects between these demonstration zones and other regions. Columns (3) and (4) show a compelling result: the Law coefficient is significantly positive only in the sample of demonstration zones. This variation can be explained by the institutional advantages of demonstration zones in terms of judicial expertise and adjudication efficiency. First, demonstration zones typically pioneer the “Three-in-One” adjudication model (integrating criminal, civil, and administrative environmental trials), which cultivates judges with specialized expertise in complex environmental laws and sciences. These professional judges are better equipped to identify “greenwashing” and impose precise penalties. Second, these zones often implement fast-track procedures (“green channels”) for environmental cases, significantly improving case adjudication efficiency. According to Deterrence Theory, the certainty and celerity of punishment in these zones create a stronger binding force on local firms, compelling them to substantively improve ESG performance.

4.4.3. Heterogeneity Across Industries with Different Pollution Levels

Finally, we explore whether the reform’s impact differs between heavy-polluting and non-heavy-polluting industries. Intuitively, one might expect a stronger effect on heavy polluters. However, the results in Columns (5) and (6) reveal a nuanced story: the effect of EPCs is significant for non-heavy-polluting firms but insignificant for heavy polluters. We offer a deepened interpretation based on industry characteristics and regulatory contexts.

First, regarding industry characteristics, heavy-polluting industries (e.g., mining, chemical, and metallurgy) are typically characterized by high capital intensity and prohibitive transformation costs [13,48]. Unlike reputation-sensitive service or light manufacturing firms that can swiftly adjust strategies, heavy polluters rely on massive fixed assets. For these firms, “going green” requires replacing entire production lines or technologies, which is a long-term and costly process that cannot be immediately triggered by judicial verdicts alone.

Second, from the perspective of regulatory substitution, heavy polluters have long been the primary targets of strict administrative environmental regulations (e.g., mandatory emission permits and frequent inspections). In this context, the establishment of EPCs may act as a substitute rather than a complement to existing administrative measures. Since the marginal compliance pressure is already near the “saturation point,” the additional deterrence from judicial reform is less likely to drive significant marginal improvements in ESG performance compared to non-heavy-polluting firms, which were previously under-regulated [49].

4.5. Mechanism Analysis

After confirming the causal relationship, we proceed to investigate the potential transmission channels linking judicial reform to ESG outcomes. We posit that the reform works through a dual channel: by intensifying external pressures on firms and by fostering their internal strategic responses. We test this proposition by examining the reform’s impact on four specific mechanism variables. Table 6 summarizes the results of the mechanism analysis.

Table 6.

Mechanism Analysis.

4.5.1. The External Pressure Channel

We first investigate how the establishment of EPCs amplifies the external pressures faced by firms.

First, we examine the impact on the intensity of local government environmental governance. We construct an index for Government Environmental Governance by performing textual analysis on the annual work reports of municipal governments. A higher value of this index indicates a stronger emphasis on environmental protection by the local government. As displayed in Column (1), the coefficient of the interest variable is positive and statistically significant. This suggests that the establishment of EPCs, as a strong judicial signal, prods local governments to enhance their environmental regulatory efforts, creating a stricter institutional environment for firms.

Second, we test the direct deterrent effect on firms by looking at Environmental Penalties. The dependent variable is defined as the natural logarithm of the total environmental penalties levied against the firm. As shown in Column (2), the coefficient of Law is positive and significant. This provides direct evidence that the judicial reform has increased the intensity of environmental law enforcement, raising the expected cost of non-compliance for polluting firms.

4.5.2. The Internal Response Channel

Next, we explore how firms internally process and react to these heightened external pressures.

First, we construct a measure of Corporate Green Cognition to capture the extent to which green and sustainability-related concepts are embedded in the firm’s strategic discourse. Following established literature [50], we employed a text analysis approach. Specifically, we constructed a keyword dictionary based on authoritative policy documents (e.g., the “13th Five-Year Plan”) to ensure semantic validity. Using Python (Version 3.12) and the “jieba” (Version 0.42.1) word segmentation tool, we extracted the frequency of these environmental keywords from the Management Discussion and Analysis section of annual reports. The natural logarithm of the total frequency was used as the proxy variable. The result in Column (3) reveals that the coefficient of Law is significantly positive. This novel finding suggests that the external judicial pressure effectively translates into a higher level of environmental awareness and strategic priority within the firm’s management.

Second, we examine the firm’s tangible commitment by analyzing its Corporate Green Investment. We quantify this variable using the ratio of corporate environmental protection expenditures to total assets. Column (4) shows a significantly positive coefficient for Law, indicating that firms respond to the judicial reform not just with words, but with substantive actions in the form of increased green capital expenditure.

In summary, the mechanism analysis paints a clear picture: the environmental judicial reform enhances corporate ESG performance by creating a powerful synergy between heightened external (governmental and punitive) pressures and proactive internal (cognitive and investment) responses.

5. Discussion

We empirically examine how specialized environmental courts drive sustainable corporate practices within the Chinese context, offering a rigorous assessment of judicial efficacy. Our findings, derived from a robust DID design, are both statistically significant and economically meaningful. This section discusses the key findings and their broader implications.

5.1. Summary of Key Findings

First and foremost, our baseline analysis reveals a strong and robust causal link: the establishment of specialized EPCs significantly promotes corporate ESG performance. This core finding withstands an extensive battery of robustness checks, including a parallel trend test that validates our research design and a placebo test that rules out the influence of unobserved confounding factors, solidifying the credibility of our causal claim.

Second, our heterogeneity analysis uncovers the nuanced and context-dependent nature of this policy effect. The promoting effect is notably amplified post-2014 and within designated “demonstration zones,” while appearing particularly potent—perhaps counterintuitively—for sectors sensitive to reputational damage (non-heavy polluters). These results suggest that the effectiveness of municipal-level judicial specialization is amplified by supportive national-level institutional reforms and a stronger local enforcement environment, and that it exerts a greater marginal influence on firms that are more sensitive to reputational and market-based pressures.

Finally, our mechanism analysis opens the “black box” of how this judicial reform translates into corporate action. We find that the establishment of EPCs operates through a dual channel. It intensifies external pressures by prompting local governments to strengthen their environmental governance and by increasing the direct penalty risks for firms. Concurrently, it fosters proactive internal responses by elevating corporate green cognition at the managerial level and ultimately driving substantive corporate green investment. This dual-channel mechanism provides a clear causal pathway from judicial intervention to tangible sustainability outcomes.

5.2. Theoretical Contributions

Our work advances the current scholarship in three distinct ways.

First, we enrich the literature on institutional theory and environmental regulation by providing novel evidence from a judicial perspective. Unlike extensive prior studies focusing on administrative mandates or market mechanisms (e.g., emissions trading), this research highlights the often-overlooked function of the judiciary as a formal institutional constraint. Our findings demonstrate that judicial specialization, exemplified by the establishment of EPCs, serves as a powerful and distinct form of environmental regulation. It can effectively enhance corporate ESG performance, likely by mitigating issues such as local protectionism that may hamper administrative enforcement. Our study thus underscores the indispensable role of an independent and professionalized judiciary in creating a robust institutional environment for sustainable development, extending the classic arguments of institutional theory [51].

Second, we enrich the corporate governance literature by demystifying the “black box” process through which external legal pressures are translated into internal strategic actions. Many studies establish a direct link from external governance mechanisms to firm outcomes, yet the intra-firm cognitive and behavioral pathways remain underexplored. By identifying and verifying “corporate green cognition” as a key mediating channel, we provide a clearer understanding of this internalization process. Our results show that judicial pressure is not merely a coercive force; it actively shapes managerial awareness and priorities, which in turn translates into substantive green investments. Aligning with the attention-based view [28], this insight offers a micro-level perspective on how firms strategically decipher and adapt to institutional signals.

Third, we extend the theoretical boundaries of stakeholder management and corporate sustainability by mapping the diverse trajectories of ESG transformation. Our intriguing finding—that the judicial reform has a more pronounced effect on firms in non-heavy-polluting industries—challenges the simplistic assumption that regulatory pressure is always most effective when targeted at the worst offenders. We propose a more nuanced view: for firms whose value is heavily reliant on reputational capital and stakeholder perception (often non-heavy polluters in consumer-facing or high-tech sectors) [52,53], environmental regulation functions not just as a compliance cost but as a strategic lever. Such enterprises are incentivized to enhance their ESG metrics, serving not merely as a compliance buffer but as a strategic signal of quality to green-conscious stakeholders. This perspective offers a valuable refinement to our understanding of the diverse motivations driving corporate sustainability strategies.

5.3. Practical Implications

Besides theoretical advancements, our findings offer actionable guidance for regulators and business leaders committed to sustainability.

For policymakers, our findings provide robust evidence supporting the continued deepening of environmental judicial reform. To maximize the policy efficacy, we propose three concrete and actionable recommendations. First, enhance the coordination mechanism between judicial bodies and administrative environmental agencies. A synergistic governance framework should be established where administrative data on pollution monitoring is shared with judicial courts, and judicial verdicts are effectively enforced by administrative bodies. This “linkage mechanism” ensures a unified front of environmental deterrence, preventing regulatory arbitrage. Second, strengthen judicial capacity in non-demonstration regions to bridge regional disparities. Since our heterogeneity analysis shows weaker effects in regions with less developed judicial foundations, resources should be tilted towards these “non-model” areas. Specific measures could include cross-regional judicial exchange programs, specialized training for judges in environmental sciences, and the establishment of circuit courts to ensure equitable environmental justice nationwide. Third, design positive incentives to guide enterprises beyond mere compliance. While judicial pressure acts as a stick, policymakers should also offer carrots to foster proactive ESG strategies. This includes tax incentives for green investments, green credit priorities for firms with superior ESG ratings, and public recognition for ESG leaders. Such measures will encourage firms to internalize ESG as a strategic value driver rather than viewing it solely as a compliance cost.

For corporate managers, our study sends a clear signal: environmental judicial risk is now a salient and strategic issue that cannot be ignored. As low-cost compliance becomes obsolete, firms must embed ESG into their strategic DNA rather than relegating it to a marginal CSR function. Our mechanism analysis offers a roadmap for this integration. It is not enough to merely react to external pressures; firms must foster genuine “green cognition” within their leadership teams. This internal cognitive shift should then be translated into tangible actions, particularly substantive green investments in cleaner production and pollution control. Through such measures and transparent engagement, firms can convert legal risks into reputational capital, securing a sustainable edge in the market.

5.4. Limitations and Future Research

Despite the robustness of our results, certain limitations remain, which open meaningful avenues for future scholarly inquiry. First, our reliance on composite ESG ratings, though standard in the literature, may not fully distinguish between firms’ substantive environmental improvements and their symbolic disclosure tactics. Future research could use more granular data, such as firm-level emissions or green patents, to specifically examine the role of judicial reform in combating corporate “greenwashing.” Second, our analysis is focused at the firm level. The cascading effects of judicial pressure throughout the supply chain, such as heightened environmental standards for suppliers, remain an important and unexplored territory.

These limitations pave the way for several promising research avenues. A particularly fruitful direction would be to delve deeper into the “black box” of the judicial process itself. By collecting and analyzing detailed data from court verdicts—such as the severity of penalties or the professional background of judges—scholars could uncover the specific attributes of judicial intervention that are most effective in driving corporate change. Furthermore, exploring the intra-organizational consequences of this reform, such as shifts in the power dynamics between legal and operational departments, could provide a richer, micro-foundational understanding of how external institutional pressures reshape corporate sustainability strategy, potentially drawing on insights from the behavioral theory of the firm [54,55].

6. Conclusions

Successfully managing the shift toward a green economy demands a profound comprehension of the institutional drivers governing corporate conduct. This study provides a comprehensive investigation into a crucial, yet under-explored, driver: the specialization of environmental justice. Using a robust DID design based on the staggered establishment of EPCs across China, we find strong and consistent evidence that this judicial reform significantly promotes corporate ESG performance.

Our contribution is threefold. We not only confirm the causal effect of this reform but also unpack its underlying mechanisms and identify its boundary conditions. Our analysis reveals that the policy operates through a powerful dual channel of intensifying external pressures and fostering proactive internal responses, including elevated green cognition and substantive green investment. Crucially, our analysis reveals that the judicial impact is amplified within robust legal environments and, notably, among reputation-sensitive sectors (light polluters), underscoring the strategic nature of corporate ESG adaptation.

In conclusion, our study underscores the pivotal role of a professionalized and independent judiciary as a cornerstone of effective environmental governance. By validating the translation of the “green rule of law” into concrete sustainability metrics, this work provides actionable frameworks for regulators and executives dedicated to advancing the sustainable development agenda.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.C., G.C. and Z.L.; methodology, Z.L.; software, Z.L.; validation, Z.C. and Z.L.; formal analysis, Z.L.; investigation, Z.L.; resources, H.L.; data curation, Z.C. and H.L.; visualization, Z.L.; writing—original draft, Z.C. and Z.L.; writing—review and editing, Z.L.; supervision, G.C. and H.L.; funding acquisition, Z.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated or analyzed during this study are not publicly available but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- DesJardine, M.R.; Zhang, M.; Shi, W. How Shareholders Impact Stakeholder Interests: A Review and Map for Future Research. J. Manag. 2023, 49, 400–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, X.; Yu, J. Striving for Sustainable Development: Green Financial Policy, Institutional Investors, and Corporate ESG Performance. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2024, 31, 1177–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvioni, D.; Gennari, F.; Bosetti, L. Sustainability and Convergence: The Future of Corporate Governance Systems? Sustainability 2016, 8, 1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Zhong, T.; Gan, S.; Liu, J.; Xu, C. Penalties vs. Subsidies: A Study on Which Is Better to Promote Corporate Environmental Governance. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 859591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, D.; Zhao, Y. The Impact of Environmental Regulations on Enterprises’ Green Innovation: The Mediating Effect of Managers’ Environmental Awareness. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, G.; Miao, J.; Miao, C.; Wei, Y.D.; Yang, D. Interplay of Environmental Regulation and Local Protectionism in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 6351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.; Su, C.; Zhang, Y.; Fan, X. Complexity Analysis of Carbon Market Using the Modified Multi-Scale Entropy. Entropy 2018, 20, 434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chava, S. Environmental Externalities and Cost of Capital. Manag. Sci. 2014, 60, 2223–2247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Ghoul, S.; Guedhami, O.; Kim, H.; Park, K. Corporate Environmental Responsibility and the Cost of Capital: International Evidence. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 149, 335–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Y.; Yang, X. Environmental Justice Specialization and Corporate ESG Performance: Evidence from China Environmental Protection Court. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, S.; Hai, M.; Fang, Z.; Zheng, D. The Role of Environmental Justice Reform in Corporate Green Transformation: Evidence from the Establishment of China’s Environmental Courts. Front. Environ. Sci. 2023, 11, 1090853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguinis, H.; Glavas, A. What We Know and Don’t Know about Corporate Social Responsibility: A Review and Research Agenda. J. Manag. 2012, 38, 932–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaffe, A. Environmental Regulation and the Competitiveness of U.S. Manufacturing: What Does the Evidence Tell Us? J. Econ. Lit. 1995, 33, 132–163. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, M.E.; Linde, C.V.D. Toward a New Conception of the Environment-Competitiveness Relationship. J. Econ. Perspect. 1995, 9, 97–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, G.S. Crime and Punishment: An Economic Approach. J. Polit. Econ. 1968, 76, 169–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Li, Y. Evaluation of the Impact of the Ecological Environment Damage Compensation System on Enterprise Pollutant Emissions. Front. Environ. Sci. 2025, 13, 1455563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, B. The Judicial Assessment of States’ Action on Climate Change Mitigation. Leiden J. Int. Law 2022, 35, 801–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, H.; Cao, Y. Environmental Justice, Ethical Transformation: Environmental Courts and Corporate ESG Performance. J. Asian Econ. 2025, 100, 101987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, M.; Zhang, G.; Yan, W.; Qi, F.; Qin, L. Greening through Courts:Environmental Law Enforcement and Corporate Green Innovation. Econ. Anal. Policy 2024, 83, 223–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiMaggio, P.J.; Powell, W.W. The Iron Cage Revisited: Institutional Isomorphism and Collective Rationality in Organizational Fields. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1983, 48, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suchman, M.C. Managing Legitimacy: Strategic and Institutional Approaches. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 571–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clément, A.; Robinot, É.; Trespeuch, L. The Use of ESG Scores in Academic Literature: A Systematic Literature Review. J. Enterp. Communities People Places Glob. Econ. 2025, 19, 92–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulou, V.; Karagiannopoulou, S.; Sariannidis, N.; Giannarakis, G. Unmasking Independent Directors: Corporate Social Responsibility Strategy as a Mediator of ESG Controversies in European Firms. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2025; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acuti, D.; Bellucci, M.; Manetti, G. Preventive and Remedial Actions in Corporate Reporting among “Addiction Industries”: Legitimacy, Effectiveness and Hypocrisy Perception. J. Bus. Ethics 2024, 189, 603–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kostka, G.; Nahm, J. Central–Local Relations: Recentralization and Environmental Governance in China. China Q. 2017, 231, 567–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Xu, T.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, X. Strategic Interactions in Environmental Regulation: Evidence from Spatial Effects across Chinese Cities. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 823838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Gao, L.; Xu, X.; Zeng, Y. Does Stricter Command-and-control Environmental Regulation Promote Total Factor Productivity? Evidence from China’s Industrial Enterprises. Discret. Dyn. Nat. Soc. 2022, 2022, 2197260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocasio, W. Towards an Attention-based View of the Firm. Strateg. Manag. J. 1997, 18, 187–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Wang, L.; Zheng, S. Executives’ ESG Cognition, External Governance, and Corporate Green Development. Econ. Anal. Policy 2025, 87, 2458–2469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helfat, C.E.; Martin, J.A. Dynamic Managerial Capabilities: Review and Assessment of Managerial Impact on Strategic Change. J. Manag. 2015, 41, 1281–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Li, H. The Impact of ESG Ratings on Low Carbon Investment: Evidence from Renewable Energy Companies. Renew. Energy 2024, 223, 119984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Chen, Y.; Si, D.-K.; Jiang, C.-Y. How Does Environmental Legislation Affect Enterprise Investment Preferences? A Quasi-Natural Experiment Based on China’s New Environmental Protection Law. Econ. Anal. Policy 2024, 81, 834–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Dai, J.; Dong, X.; Liu, J. ESG Rating Disagreement and Analyst Forecast Quality. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2024, 95, 103446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Yang, Q.; Wei, K.; Dai, P.-F. ESG Rating Disagreement and Idiosyncratic Return Volatility: Evidence from China. Res. Int. Bus. Financ. 2024, 70, 102368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khurram, M.U.; Abbassi, W.; Chen, Y.; Chen, L. Outward Foreign Investment Performance, Digital Transformation, and ESG Performance: Evidence from China. Glob. Financ. J. 2024, 60, 100963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Firth, M.; Gao, D.N.; Rui, O.M. Ownership Structure, Corporate Governance, and Fraud: Evidence from China. J. Corp. Financ. 2006, 12, 424–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Ke, J.; Chen, A.; Cai, X. Judicial Independence and Corporate Innovation: Evidence from China’s Unified Management of Local Courts Reform. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2025, 102, 104331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Y.; Wu, W. Environment, Social, and Governance Performance and Corporate Financing Constraints. Financ. Res. Lett. 2024, 62, 105083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, T.; Yang, C. State-Owned Equity Participation and Corporations’ ESG Performance in China: The Mediating Role of Top Management Incentives. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Yatim, P.; Ngan, S.L. Empirical Research on the Effect of Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) Rating on Green Innovation of Chinese a-Share Listed Companies. Int. J. Clim. Change Strateg. Manag. 2025, 17, 70–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Wang, Z.; Huang, Q.; Ding, H. The Impact of ESG Performance on Corporate Value in Listed Sports Companies: The Mediating Role of Intangible Assets and Moderating Role of Policy Environment. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertrand, M.; Duflo, E.; Mullainathan, S. How Much Should We Trust Differences-in-Differences Estimates? Q. J. Econ. 2004, 119, 249–275. [Google Scholar]

- Flammer, C. Corporate Social Responsibility and Shareholder Reaction: The Environmental Awareness of Investors. Acad. Manag. J. 2013, 56, 758–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.; Vuković, D.B.; Sokolov, B.I.; Vukovic, N.; Liu, Y. Enhancing ESG Performance through Digital Transformation: Insights from China’s Manufacturing Sector. Technol. Soc. 2024, 79, 102753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Wang, Z.; Tang, Y.; Yang, F. ESG Performance, Green Technology Innovation, and Corporate Value: Evidence from Industrial Listed Companies. Alex. Eng. J. 2025, 123, 369–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lins, K.V.; Servaes, H.; Tamayo, A. Social Capital, Trust, and Firm Performance: The Value of Corporate Social Responsibility during the Financial Crisis. J. Financ. 2017, 72, 1785–1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Zheng, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, S. Environmental Justice and Corporate Green Transition: A New Perspective from Environmental Courts in China. Econ. Change Restruct. 2025, 58, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, B.; Xiang, Q. Environmental Regulation, Industrial Innovation and Green Development of Chinese Manufacturing: Based on an Extended CDM Model. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 176, 895–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Shen, N. Environmental Regulation and Environmental Productivity: The Case of China. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 62, 758–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, Z.; Cao, Y.; Goh, M.; Wang, Y. Executive Green Cognition and Corporate ESG Performance. Financ. Res. Lett. 2024, 69, 106271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- North, D.C. Institutions. J. Econ. Perspect. 1991, 5, 97–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fombrun, C.; Shanley, M. What’s in a Name? Reputation Building and Corporate Strategy. Acad. Manag. J. 1990, 33, 233–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karpoff, J.M.; Lott, J.; Wehrly, E.W. The Reputational Penalties for Environmental Violations: Empirical Evidence. J. Law Econ. 2005, 48, 653–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, M.C.; Meckling, W.H. Theory of the Firm: Managerial Behavior, Agency Costs and Ownership Structure. J. Financ. Econ. 1976, 3, 305–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Liu, P.; Chen, H. Corporate ESG Performance, Green Innovation, and Green New Quality Productivity: Evidence from China. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.