Abstract

This paper presents a systematic literature review (SLR) of research on strategic positioning of companies and the measurement of greenwashing in sustainability reporting. Its main aim is to synthesize and organize the existing literature, identify key research gaps, and outline directions for future studies. Drawing on a rigorous content analysis of 88 studies, we delineate strategic typologies of greenwashing in sustainability reporting and examine content-analysis-based measurement approaches used to detect it. Our SLR shows that most strategic typologies draw on theories such as legitimacy theory, impression management theory, signaling theory, and stakeholder theory. Several studies adopt a four-quadrant matrix with varying conceptual dimensions, while others classify strategic responses to institutional pressures along a passive–active continuum. However, the evidence suggests that to assume that companies uniformly pursue sustainability reporting strategies is a major oversimplification. The findings also indicate that the literature proposes a variety of innovative, content-analysis-based approaches aimed at capturing divergences between communicative claims and organizational realities—most notably, discrepancies between disclosure and measurable performance, and between symbolic and substantive sustainability actions, as well as the identification of selective or manipulative communication practices that may signal greenwashing. Analytical techniques commonly focus on linguistic and visual cues in sustainability reports, including tone (sentiment and narrative framing), readability (both traditional readability indices and machine learning–based textual complexity measures), and visual content (selective emphasis, imagery framing, and graphic distortions). We also synthesize studies that document empirically verified instances of greenwashing and contrast them with research that, in our view, relies on overly simplified or untested assumptions. Based on this SLR, we identify central theoretical and methodological priorities for advancing the study of greenwashing in sustainability reporting and propose a research agenda to guide future research.

1. Introduction

The concept of greenwashing began to gain wider attention in the late 1990s, with scholarly and public interest in the issue continuing to grow over the following decades [1]. Although research on this phenomenon has expanded significantly, the concept still lacks a single, universally accepted definition, and its interpretation remains open to debate [2]. It was originally applied to environmental issues and defined as “the intersection of two firm behaviors: poor environmental performance and positive communication about environmental performance” [3]. It was also referred to as “symbolic corporate environmentalism” [4]. Subsequently, the concept evolved into a broader interpretation, described as the “selective disclosure of positive information about a company’s environmental or social performance without full disclosure of negative information on these dimensions, so as to create an overly positive corporate image” [5] or the “act of presenting a company’s environmental and/or social performance in a misleading way” [6]. Following the triple-bottom-line approach to sustainability and the principles of environmental integrity, social equity, and economic prosperity, addressing environmental, social, and economic issues has become essential to discussions of greenwashing [2].

Greenwashing has been analyzed from various perspectives, with the literature presenting different conceptualizations of its relationship to similar notions. Some authors interpret it as a form of decoupling [7], highlighting the discrepancy between dissemination of symbolic statements (“talk”) and actual actions (“walk”) [8]. Others view greenwashing as a concept that describes decoupling processes within the context of sustainability, treating greenwashing and decoupling as synonyms [9,10,11]. Yet, Siano et al. [12] distinguish between two primary types of greenwashing: decoupling and attention deflection. In this context, decoupling refers to the gap between disclosure and performance [13] or between policy statements and actual corporate commitment [14], as well as the disconnection between means and ends [15]. It also includes impression management practices that involve “empty green claims and policies” and “sin of fibbing,” in which companies make claims that are outright false [16]. Impression management encompasses emphasizing positive organizational outcomes (enhancement) or obfuscating negative organizational outcomes (concealment) [17].

Attention deflection, as the act of concealing unethical business practices, encompasses various deceptive communication tactics, such as selective and inaccurate disclosure [5], including incomplete comparisons and vague or irrelevant statements [18]. It also involves misleading written texts and visual imagery [19] as well as unverifiable claims, such as implied superiority and the “sin of no proof,” where assertions lack substantiating evidence or accessible supporting information [20].

Greenwashing involves both the overstatement of positive performance and the concealment of negative information [21,22]. It encompasses a broad range of practices commonly characterized by the dissemination of misleading information [23], including various forms of false claims rooted in hypocrisy and/or deception [24]. Some authors connect greenwashing with the obfuscation of negative sustainability information, suggesting that companies with inferior sustainability performance use complex, ambiguous language to produce intentionally opaque or confusing reports [25]. This means that greenwashing can be identified through linguistic patterns, which often rely on overly optimistic terms that emphasize positive aspects. Accordingly, the literature on greenwashing is closely related to research on selective disclosure, in which favorable information is emphasized while unfavorable details are minimized or omitted [26].

In this paper, we refer to greenwashing in sustainability reporting as the deliberate or unintended dissemination of misleading, incomplete, or overly favorable sustainability-related disclosures. It is manifested through the selective presentation of positive information, the concealment or obfuscation of negative performance, or the decoupling of reported claims from underlying organizational practices. This process constructs an unjustifiably positive impression of corporate sustainability by overstating positive actions and concealing negative ones.

The complex and often ambiguous nature of greenwashing presents substantial methodological challenges for researchers attempting to identify and measure it. At the same time, these challenges offer valuable opportunities for future inquiry [27]. However, there remains a limited understanding regarding the strategic typologies of greenwashing in sustainability reporting and the approaches used to measure it, including their operationalization, methodologies, and data sources applied in this field [28]. In particular, approaches based on content analysis are especially valuable and offer significant conceptual and empirical insights, given that much of the existing research on greenwashing relies on indicators derived from secondary sources such as dedicated databases and specific ratings, which are not always transparent, are often binary, and may be arbitrary or highly autocorrelated. In fact, using composite ESG indicators derived from secondary sources typically provides only aggregated scores, obscuring which aspect of greenwashing is measured, reducing comparability across heterogeneous providers, and limiting replicability where access to commercial ESG databases is restricted [29,30,31].

Growing scholarly interest in greenwashing has resulted in the publication of several systematic literature reviews [32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39] and bibliometric analyses that characterize the structure and trends in this scientific field [40,41,42,43]. Nonetheless, systematic literature reviews focusing specifically on the measurement of greenwashing [32] and greenwashing in sustainability reporting [44,45] remain scarce. This scarcity is particularly evident in relation to strategic typologies of greenwashing in sustainability reporting and to measurement approaches grounded in content-analysis studies.

Given these challenges and the rapidly expanding research on greenwashing in sustainability reporting, it is crucial to build on existing analyses to address persistent gaps and explore under-researched areas.

The main aim of this paper, therefore, is to systematically organize and synthesize the current literature, identify key research gaps, and outline directions for future studies in this field. We offer, to the best of our knowledge, one of the most comprehensive syntheses to date of strategic typologies of greenwashing in sustainability reporting and provide an integrated, conceptually grounded overview of existing approaches and analytical techniques used to measure and detect greenwashing through content analysis. In particular, our systematic literature review aims to address the following research questions, which have not been sufficiently explored in existing research:

- What strategic typologies of greenwashing in sustainability reporting have been identified in the literature?

- What content analysis–based measurement approaches are used to detect greenwashing in sustainability reporting?

2. Materials and Methods

We conducted a systematic literature review (SLR) to address the research questions outlined in the introduction. As a rigorous and structured research method, an SLR facilitates a comprehensive examination of scholarly works within a specific research domain. This approach enables the mapping and synthesis of existing knowledge while providing insight into the interconnections among studies. Furthermore, it supports the identification, classification, and critical evaluation of the current body of literature, thereby establishing a foundation for recognizing research gaps and proposing future research directions [28,35,46,47].

The SLR presented in this study was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA 2020) guidelines [48]. The review utilized the Scopus and Web of Science (WoS) Core Collection databases, selected for their reliability, relevance, and frequent use in systematic reviews [35,49]. In addition, these databases are the most widely used citation indexes in the world, and, consequently, most bibliometric and scientometric tools are based on them [50,51].

To improve methodological robustness, the selection of search terms was informed by a comprehensive review of previous SLRs and bibliometric analyses on greenwashing [28,35,36,37,39], sustainability reporting [52,53,54,55], and research integrating both topics [45]. To ensure comprehensive coverage of the research field, a thorough search was conducted using keywords that combined terms related to greenwashing and sustainability reporting.

First, we created a list of terms describing greenwashing activities, which included the following keywords: “greenwash,” “green wash,” “green-wash*,” “decoupling,” “cheating,” “obfuscation,” and “deceptive.”

Second, given the diverse terminology used in extensive sustainability reporting research, a detailed search was conducted using keywords such as “sustainability report*/disclosure,” “sustainable development report*/disclosure,” “corporate social responsibility report*/disclosure,” “CSR report*/disclosure,” “responsib* report*/disclosure,” “ESG report*/disclosure,” “corporate citizenship report*/disclosure,” “triple bottom line report*/disclosure,” “TBL report*/disclosure,” “GRI report*/disclosure,” “Global Reporting Initiative report*/disclosure,” “sustainable development goal* report*/disclosure,” “SDG* report*/disclosure,” “integr* report*/disclosure,” “non-financ* report*/disclosure,” “environm* report*/disclosure,” “green report*/disclosure,” “GHG report*/disclosure,” “greenhouse gas report*/disclosure,” “carbon report*/disclosure,” and “social report*/disclosure”.

The list of query words and the combined query string used in this study are provided in Table A1 and Table A2 in the Appendix A.

Next, we defined the inclusion and exclusion criteria for the review (Table A3 in the Appendix A). A study was considered eligible if the publication explicitly addressed the phenomenon of greenwashing in the context of sustainability reporting as a primary research topic. In addition, the study had to discuss greenwashing strategies or methods for measuring greenwashing that were grounded in content analysis of sustainability reporting. We also specified that each study must operationalize at least one dimension of greenwashing through content analysis of sustainability reports or other corporate disclosures containing ESG-related information.

For the exclusion criteria, we omitted publications not written in English, reflecting the dominance of English in scientific communication [56] and reducing language and translation bias [28,57]. We also excluded books, book chapters, editorial materials, meeting abstracts, and data papers, as these document types typically do not undergo a rigorous peer-review process that ensures the reliability and credibility of empirical findings [58]. This approach is standard in many SLRs [28,49]. A complete list of inclusion and exclusion criteria is provided in Table A3 in the Appendix A.

The search was conducted on 17 February 2025, utilizing the query string detailed in Table A2 in the Appendix A. After applying the initial exclusion criteria outlined in phase 1 (document type and language), 249 publications were identified in Scopus and 199 in WoS, resulting in a combined total of 448 records. Following the removal of 174 duplicate records from the two databases, the final dataset consisted of 274 unique publications. To organize key information throughout the process and to facilitate the identification and elimination of duplicates, we used a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet.

In the subsequent screening stage, the titles, abstracts, and keywords of the 274 publications were reviewed by two researchers (the co-authors) to assess their relevance to the study’s objectives and determine eligibility for further analysis and data extraction. Each researcher independently screened all 274 publications to evaluate whether greenwashing in the context of sustainability reporting constituted the primary focus of the article. They also assessed whether the study involved an empirical examination of greenwashing in corporate reporting in line with the predefined scope of the review. Based on these criteria, each publication was classified as either “include” or “exclude.” In cases where a researcher—after reviewing the title, keywords, and abstract—was uncertain about whether a publication met the inclusion criteria, it was conservatively classified as “include” and was retained for full-text assessment in the next stage. To evaluate inter-rater (inter-coder) reliability for the binary inclusion/exclusion decision, the reviewers’ assessments were compared and Cohen’s kappa coefficient was calculated. Cohen’s kappa coefficient was high (κ = 0.84; 95% CI: 0.78–0.91), indicating strong agreement between the two reviewers [59,60]. In cases where discrepancies between the researchers’ decisions occurred, the publication was retained for full-text review in the next stage. As a result of this phase, 182 publications were retained for the research sample, while 92 were excluded as not relevant to the review’s objectives. Full texts were subsequently retrieved for the 182 included studies. Only 4 publications could not be obtained. Additionally, 21 publications were identified through the snowballing method.

In the next stage, 178 publications identified through database searches and 21 additional publications identified via snowball sampling were subjected to in-depth full-text analysis. The same two researchers independently reviewed the full texts, applying inclusion criteria derived directly from the research questions: (1) the article discussed greenwashing strategies in the context of sustainability reporting as a central topic, or (2) the study presented and empirically applied at least one content-analysis-based approach to measuring greenwashing. Publications were excluded if greenwashing strategies or measurement approaches were addressed only tangentially, if no methods or approaches based on content analysis of sustainability reports or other ESG-related disclosures were presented or applied, or if all dimensions of greenwashing were operationalized exclusively through external ESG scores from global financial or non-financial data vendors. Inter-coder decisions were again compared, and Cohen’s kappa was recalculated. Agreement for full-text eligibility reached 88% (95% CI: 0.81–0.95), indicating an almost perfect level of agreement [59,60]. In cases of disagreement, both researchers re-examined the publication, discussed their assessments, and reached a joint decision. Following this process, 88 publications were retained for further analysis (76 identified through database searches and 12 identified via snowball sampling).

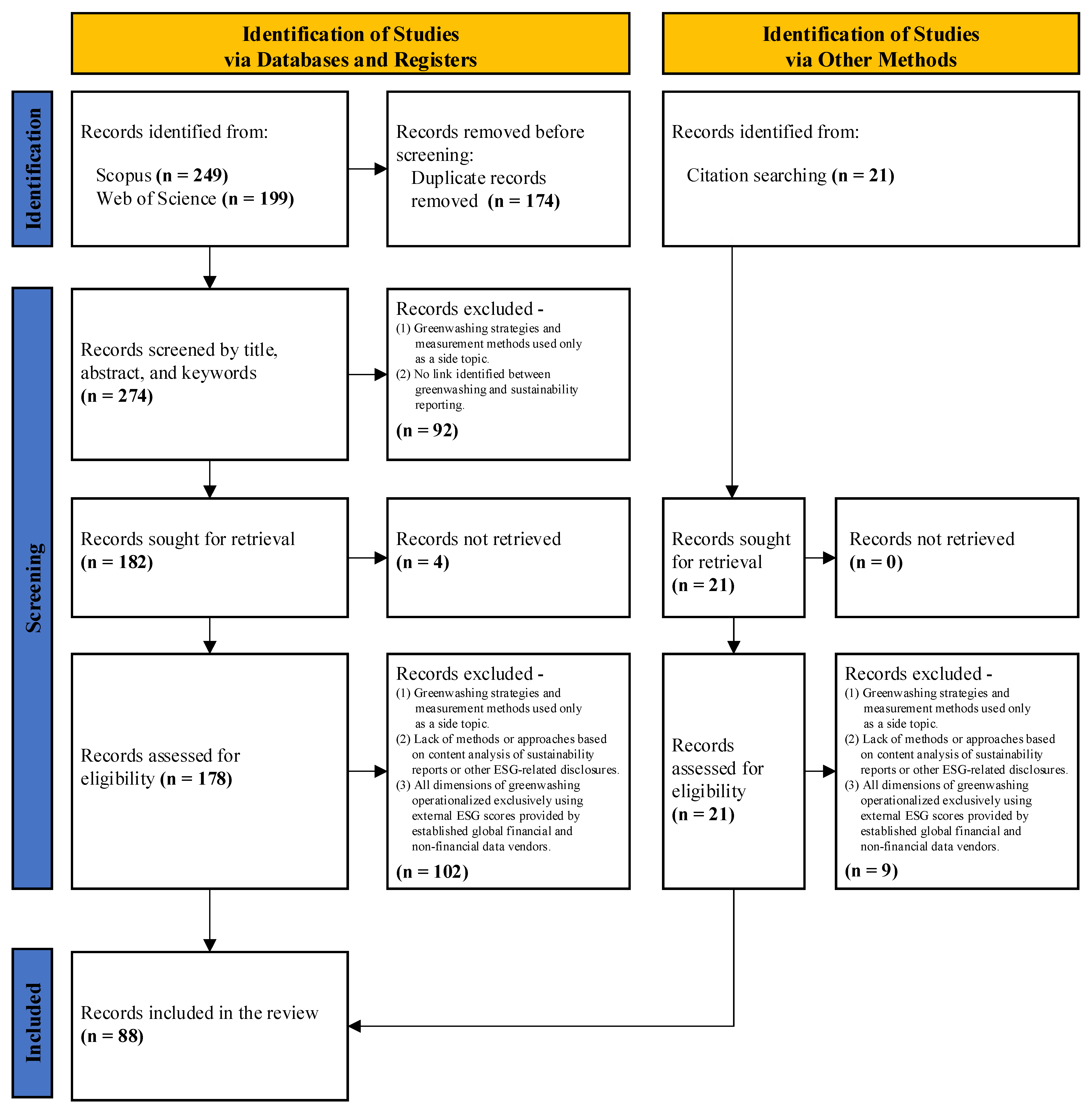

To provide a clearer understanding of the process of searching and including publications in this review, the PRISMA 2020 flow diagram is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

PRISMA 2020 flow diagram for SLR of research on greenwashing in sustainability reporting. Source: Authors’ elaboration based on [48].

In the final step of the SLR, a thematic content analysis was conducted to extract and synthesize data relevant to the research questions. A narrative synthesis approach was applied, combining systematic textual summarization with interpretive analysis of the findings, as appropriate given the objectives of this review [61,62]. Two researchers independently reviewed and coded the full texts of all publications to ensure the validity and reliability of the findings. A combined deductive–inductive coding strategy was used. At the deductive level, the coding framework was structured around two main thematic groups of studies, corresponding to the research questions: (1) articles addressing strategic typologies of greenwashing in sustainability reporting and (2) articles presenting and applying content-analysis-based approaches and analytical techniques for measuring greenwashing.

Within each thematic group, additional codes were developed inductively to capture recurring concepts and patterns emerging from the material. For studies classified in the first group (strategic typologies), we coded the following elements: authorship, the theoretical framework(s) used, research sample characteristics, and the characteristics of strategic approaches. For studies classified in the second group (measurement approaches), we coded the following elements: authorship, the measurement approach or analytical technique used, research sample characteristics, the type of data, the method of data acquisition, and the sustainability focus of the measurement (environmental, social, and/or governance).

All codes were documented in a shared Excel spreadsheet, which was used to organize, structure, and synthesize the extracted information and to compile Table A4 and Table A5 in the Appendix A, providing a structured overview of the coded variables. Discrepancies in coding between the two researchers were resolved through discussion, and any agreed refinements of the coding scheme were applied consistently across all publications.

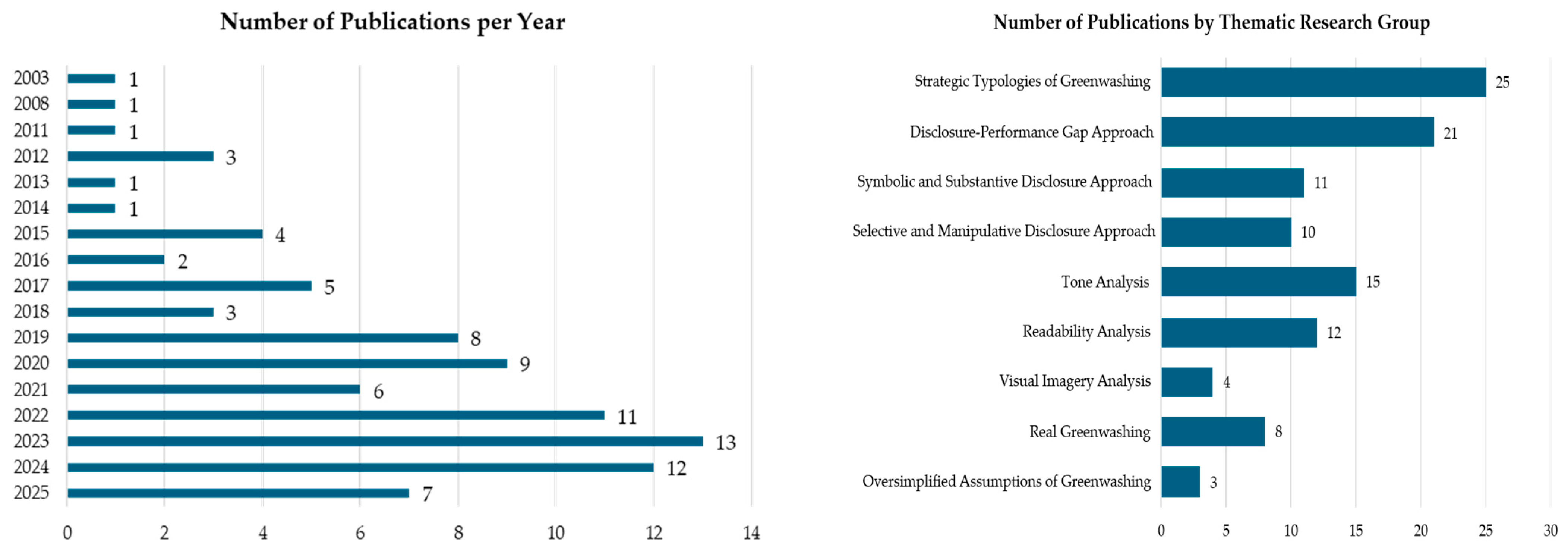

Figure 2 presents the quantitative descriptive characteristics of the analyzed publications, while the following section reports the results of the qualitative content analysis for the two thematic groups. Detailed characteristics of the studies included in the SLR are provided in Table A4 and Table A5 in the Appendix A. It should be noted that some publications addressed both thematic areas (i.e., they proposed a strategic typology and, at the same time, developed or applied a content-analysis-based measurement approach).

Figure 2.

Quantitative descriptive characteristics of the analyzed publications.

In addition, to evaluate the methodological quality and transparency of the review process, the PRISMA 2020 checklist was completed, and compliance with its 27 reporting items was verified (Table S1 in the Supplementary Material).

3. Results and Discussion

This section presents the main findings of the SLR on greenwashing in sustainability reporting. It synthesizes key strategic typologies, content-analysis–based measurement approaches, and analytical techniques used to identify greenwashing. By integrating theoretical, methodological, and empirical insights, the section elucidates how greenwashing has been conceptualized, operationalized, and evidenced across the extant literature.

3.1. Strategic Typologies of Greenwashing in Sustainability Reporting

Research on strategic typologies of greenwashing in sustainability reporting primarily draws on legitimacy theory, impression management theory, signaling theory, and stakeholder theory.

Most existing typologies are structured around a four-quadrant matrix but differ in the dimensions considered. Amores-Salvadό et al. [63] developed a model of four distinct strategic positions by comparing environmental performance and disclosure relative to industry averages. They identify two coherent approaches—green leaders and blackbirds—and two incoherent ones: green quiets (representing brownwashing) and green parrots (indicative of greenwashing). Kurpierz and Smith [64] refined Delmas and Burbano’s [3] greenwashing typology by focusing on the truthfulness of claims (true/false) and their consequences (harm/no harm), thereby deconstructing greenwashing into a harm/no-harm dichotomy that differentiates between fraudulent practices and “cheap talk.” Cooper and Wang [65] analyzed the relationship between reported policy and activities addressing refugee needs. They categorized corporations into four types—reactionary, recurring, relevant, and revelatory—based on the consistency of refugee programming over time and the degree of alignment between programs, policies, and impacts.

In another approach, strategic responses to institutional influences in sustainability reporting have been classified along a continuum from passive to active. Acquiescence represents the most passive strategy, manipulation the most active, while compromise, avoidance, and defiance fall in between [66].

Various typologies are derived from impression management theory. Talbot and Barbat [67] identified four impression management strategies in mining companies’ CSR reports aimed at neutralizing and obscuring negative information on water performance. These include two data manipulation strategies—strategic omission and obfuscation—used to conceal noncompliance and poor performance, and two defensive strategies—minimizing environmental impact and relativizing poor environmental performance—employed to legitimize negative aspects. Leung and Snell [68] found that gambling companies use five camouflaging-based disclosure strategies—zero disclosure, curtailment, disclamation, defensive façades, and assertive façades—involving impression management to selectively maintain moral legitimacy amid shifting institutional expectations. Drawing on an analysis of communication strategies employed by Spanish listed companies regarding the SDGs, García-Sánchez et al. [69] revealed the use of legitimization strategy alongside proactive and defensive impression management approaches. The proactive approach focused on congratulation, self-promotion, and organizational promotion, while the defensive approach addressed negative situations through excuses, justifications, and apologies.

In the context of signaling theory and legitimization strategies, Hahn and Lülfs [70], drawing on the concepts of symbolic and substantive management of legitimacy, identified six specific strategies for disclosing negative aspects in sustainability reports: marginalization, abstraction, indication of facts, rationalization (instrumental and theoretical), authorization, and corrective action (type 1 and type 2). Saber and Weber [71] subsequently applied the same framework and typology. Yuan et al. [72] identified three distinct greenwashing strategies: exaggerating, referring to the gap between actual performance and disclosure; distracting, highlighting the gap between strengths and concerns; and window-dressing, addressing the gap between materiality and immateriality. Leung and Snell [73] further revealed that companies in controversial industries, such as gambling, often engage in symbolic manipulation rather than substantive CSR, aiming to alter perceptions of corporate identity by emphasizing pragmatic legitimacy, diverting attention from moral legitimacy issues, and manipulating cognitive symbols. Finally, Martínez-Ferrero et al. [74] found that companies with superior CSR performance tend to use high-quality CSR reporting to highlight achievements (enhancement strategy), offering more comparable and reliable information. In contrast, companies with poorer CSR performance often employ low-quality reporting to obscure actual performance (obfuscation strategy), providing information that is less balanced, accurate, and clear.

While some researchers emphasize the exaggerated optimism in sustainability communications, others focus on the defensive strategies employed by companies. Laskin and Mikhailovna Nesova [26] demonstrated that sustainability reports are characterized by pronounced optimism, as they employ a higher frequency of positively charged linguistic elements—such as praise, satisfaction, and inspiration—while reducing the use of negatively charged expressions such as blame, hardship, and denial. Megura and Gunderson [75] identified subtle forms of climate change denial in the sustainability reports of fossil fuel companies, manifested as ideological denialism, greenwashing, and reification. Moreover, they observed various forms of greenwashing used to manipulate stakeholder perceptions within climate-related narratives, including techno-optimism, compliance, countermeasures, and omission. Laufer [76] argued that companies use defensive strategies to protect themselves from liability, both internally and externally, with greenwashing relying on three key elements of deception: confusion, fronting, and posturing. Companies sometimes engage in strategic silence, with sustainability reports omitting concrete strategies for managing or curbing overproduction—a form of vagueness recognized as a signal of greenwashing [77]. Research by Roszkowska-Menkes et al. [9] identified the selective disclosure of negative events in sustainability reporting, manifested in three forms: vague disclosure, avoidance, and hypocrisy. In addition, Gentile and Gupta [78] identified several strategies adopted by leading global fossil fuel companies, including necessitarianism; greenwashing, manifested through claims of sustainability, strategic wording, overstated commitments, half-truths, the use of ‘net-zero’ as a marketing label, and avoidance of critical issues (‘the elephant in the room’); strategic blame placement; and techno-optimism.

Considering how visual elements can be leveraged to influence CSR reports, Friedel [79] emphasized the strategic use of images and text and their impact on the perceived objectivity and construction of truth, highlighting how corporate myths are created and maintained to enhance organizational legitimacy. Additionally, Cho et al. [80] and Cüre et al. [81] investigated corporate manipulation of graphs in sustainability reporting and identified two impression management strategies—enhancement and obfuscation—evidenced by the selective presentation of graphical data emphasizing favorable trends and the inclusion of material distortions within the graphs.

Research shows that to assume that companies adopt uniform sustainability reporting strategies is a significant oversimplification. Moreover, ESG practices are driven by diverse motivations, including strategic, altruistic, and greenwashing-related incentives [82]. Schons and Steinmeier [10] argue that companies can adopt strategies that combine symbolic and substantive CSR actions. This means that some of them may choose not to engage in CSR at all—either symbolically or substantively—and then they are referred to as Neglectors. Other companies may decide to focus primarily on symbolic actions (Greenwashers), who follow a “mere talk” strategy, or on substantive actions (Silent Saints), who adopt a “mere walk” strategy. Finally, some companies may demonstrate high levels of both symbolic and substantive engagement, acting as Balanced Engagers who “walk the talk”. Siano et al. [12] argued that the simple distinction between talk and action is insufficient. Following the Volkswagen emissions scandal, they expanded the greenwashing taxonomy—originally encompassing decoupling and attention deflection—by identifying a new form of irresponsible behavior, namely “deceptive manipulation,” in which sustainability communication is deliberately used to manipulate actual business practices. Furthermore, Cho et al. [83] argued that more diverse and nuanced theoretical perspectives are needed to understand sustainability reporting, as conflicting societal and institutional pressures can force companies to engage in organizational hypocrisy by creating and maintaining discrepant façades, such as rational, progressive, and reputational.

Considering research on strategic typologies of greenwashing in sustainability reporting, most studies in this domain can be viewed as extending or complementing one another rather than offering contradictory insights. Apparent inconsistencies typically stem from scholars examining different dimensions of greenwashing—for instance, exaggerated optimism versus subtle forms of denial, or text-based versus visual communication strategies. Moreover, the literature has evolved from simple 2 × 2 typologies toward more sophisticated frameworks that either position strategic responses to institutional pressures along a passive–active continuum or conceptualize varying forms and degrees of obfuscation or deception.

Table 1 summarizes the strategic approaches and conceptual positions of greenwashing identified in sustainability reporting. A detailed description of the underlying studies is provided in Table A4 in the Appendix A.

Table 1.

Overview of Strategic Typologies of Greenwashing in Sustainability Reporting.

3.2. Approaches to Measuring Greenwashing in Sustainability Reporting Using Content Analysis

3.2.1. Disclosure–Performance Gap Approach

One of the main approaches used to measure greenwashing in sustainability reporting focuses on the discrepancy between sustainability disclosure (D) and actual sustainability performance (P). Within this framework, researchers quantify ESG disclosure (i.e., what companies communicate about their sustainability actions) separately from ESG performance (i.e., what companies actually achieve). Greenwashing is thus conceptualized as the difference, imbalance, or misalignment between these two constructs. This approach builds on the “talk–walk gap” perspective, which assumes that companies may deliberately overstate their sustainability commitments when actual performance fails to support the communicated narrative.

In accordance with the inclusion criteria adopted in this review, the analyzed sample consists exclusively of studies in which at least one component of greenwashing measurement—disclosure and/or performance—is derived from content analysis of sustainability-related reports. While content analysis is most frequently applied to capture the scope and characteristics of sustainability disclosure [1,11,23,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94], the sample also includes studies in which both disclosure and performance measures are extracted from sustainability report content and subsequently coded using predefined analytical schemes [95,96,97,98,99].

Various methods have been employed to quantify sustainability disclosure. The most prevalent approach involves counting the frequency of environmental (E), social (S), and governance (G) keywords and normalizing these counts by the total word count of sustainability reports [23,84,88]. Some studies further refined this approach by weighting ESG terminology according to its contextual relevance or importance [86,97,98,99], or by assigning differentiated weights to monetary, quantitative, and purely narrative statements to assess disclosure precision, with financial data considered the most credible form of evidence [1]. Some studies have used advanced natural language processing techniques to quantify ESG disclosures, combining content extraction with sentiment analysis [87,91,92,93,94].

Beyond quantitative text metrics or sentiment indicators, several studies operationalized disclosure through checklist-based assessments, identifying the presence or absence of specific sustainability elements, typically coded in binary form [11,85,89,90,95,96]. In addition, environmental disclosure has also been quantified using self-reported environmental data submitted to external registries, treating reported quantities as indicators of environmental transparency [7,100].

In the reviewed studies, sustainability performance was most frequently quantified using external ESG scores provided by established global financial and non-financial data vendors, including Bloomberg [1,85,91], Refinitiv (now LSEG Data) [23], MSCI KLD STAT [11,93], CNRDS [88,92], HEXUN-RKS [90,94] and KOSPI200 [86]. Lagasio [87] also employed a normalized ESG score to assess greenwashing, although the data source for this metric was not explicitly specified. In several studies, environmental performance indicators were obtained directly from external operational data registries, most commonly from greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions reported to regulatory authorities and environmental agencies [7,89,100].

In the remaining group of studies, ESG performance was derived through content analysis of sustainability reports. These studies constructed checklist-based assessments of indicators aligned with the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) framework or specific ESG actions. Quantitatively verified practices were distinguished from qualitative descriptions, with greater weight assigned to evidence supported by measurable or verifiable data [84,95,96,97,98,99].

An overview of methods used to operationalize ESG disclosures and performances is presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Methods for Operationalizing Greenwashing in Sustainability Reporting through the Disclosure–Performance Gap.

In the analyzed studies, greenwashing is primarily conceptualized as the discrepancy between companies’ communicated sustainability claims and their actual sustainability performance. Accordingly, empirical measurement typically relies on discrepancy-based indicators, expressed either as the difference between ESG disclosure levels and ESG performance levels [1,88,90] or as the ratio of disclosed ESG items to implemented sustainability actions [23].

More advanced studies develop customized indicators that integrate cognitive and linguistic dimensions of sustainability communication. For instance, Kim et al. [86] define greenwashing as the difference between text-weighted ESG disclosure scores—which capture the depth and materiality of sustainability language—and ESG performance. Kim and Lyon [7] measure greenwashing as the deviation between declared and actual emission reductions, normalized by declared reduction levels to control for firm-size effects. Similarly, Lagasio [87] constructs an “ESG-washing” metric by subtracting standardized sustainability performance scores from sentiment-based ESG disclosure indices. Lee and Raschke [23] compute the ratio of textual ESG performance communication to standardized Refinitiv ESG scores to capture the communicative exaggeration of performance. Li et al. [96] likewise calculate greenwashing as the discrepancy between standardized indices of green communication (GCI) and green practices (GPI), reflecting overstated communication relative to actual initiatives. Finally, Zhou and Chen [97] and Zhou et al. [98,99] operationalize greenwashing as the standardized disparity between weighted textual disclosure indices and quantified environmental performance indicators, offering a multidimensional representation of disclosure–performance misalignment.

In summary, methods for measuring greenwashing through content analysis of sustainability disclosures and performance consistently draw on the notion of the “talk–walk gap,” but operationalize it in different ways, thus yielding different analytical insights. Checklist-based indices provide transparency and close alignment with reporting standards but are highly labor-intensive and limited in scalability. Keyword-frequency approaches offer strong scalability but primarily measure the volume of ESG communication, which can lead to inflated perceptions of disclosure quality. More advanced approaches—such as quality-weighted metrics, sentiment analysis, and broader NLP techniques—more effectively capture discrepancies between communication and actual performance, but they require specialized tools and expertise, and their outputs may diverge from those produced by simpler measures. On the performance side, ESG ratings, hard ESG indicators, and checklist-based indices capture distinct facets of sustainability, resulting in varying assessments of the same companies. ESG ratings face additional challenges due to methodological opacity, dependence on corporate disclosures, and inconsistency across providers. Overall, the evidence suggests that disclosure and performance measures should be viewed as complementary: differences between them reflect the multidimensional nature of greenwashing rather than measurement error.

3.2.2. Symbolic and Substantive Disclosure Approach

The second methodological approach conceptualizes greenwashing as the distinction between symbolic and substantive sustainability disclosures, determined by the credibility, specificity, and verifiability of the information provided. Within this framework, it is assumed that companies may use sustainability rhetoric as a means of gaining legitimacy by emphasizing broad commitments or aspirational claims that are not substantiated by verifiable actions, measurable outcomes, or tangible resource allocations. Consequently, content analysis of sustainability reports is used to identify the nature of corporate sustainability activities, classify them as symbolic or substantive, and assess the potential imbalance between these two dimensions in sustainability reporting. From this perspective, greenwashing is operationalized as a predominance of symbolic content over substantive information [101,102,103]. However, it should be emphasized that symbolic communication should not, in all contexts, be treated as synonymous with greenwashing. It constitutes greenwashing only when it systematically substitutes for or obscures substantive information, rather than when it coexists with reliable, performance-based disclosure [6,30,103,104].

Symbolic actions (often referred to as green talk) occur when a company makes claims or discloses information about social or environmental initiatives that are not actually implemented in practice [24]. Such symbolic disclosures tend to be broad, predominantly positive, and typically lack measurable evidence or verifiable outcomes. In contrast, substantive actions (green walk) refer to disclosures describing initiatives that have been materially implemented and have produced tangible, verifiable impacts. In other words, whenever a company provides detailed and evidence-based information about a specific action, or when the accuracy of its claims can be verified, the disclosure is considered substantive [24].

Although the symbolic–substantive distinction is the most widely used conceptualization in the literature, several authors employ alternative terminology to describe comparable phenomena. For example, Khan et al. [104] differentiate between cosmetic and organic efforts, where cosmetic efforts rely on rhetorical strategies and attention-grabbing narratives that superficially frame positive environmental performance, whereas organic actions reflect credible and meaningful initiatives supported by concrete evidence. Xing et al. [102] distinguish between soft and hard sustainability disclosures, with soft disclosures referring to claims without strong objective evidence, typically compiled by companies themselves, and hard disclosures based on quantitative data that can be verified by other institutions. Despite the different terminology, these studies share a common assumption: symbolic communication reflects declarative or aspirational expressions of commitment, while substantive actions provide verifiable evidence of actual progress towards sustainability.

Our SLR revealed that most authors applied checklist-based classification schemes to distinguish between symbolic and substantive sustainability actions. This method relies on predefined lists of sustainability-related issues or actions, where each disclosed item is coded as symbolic or substantive depending on its level of detail, quantification, and verifiability. For example, Xing et al. [102] developed a checklist consisting of 16 soft and 79 hard disclosure items, representing narrative versus evidence-based information. Khan et al. [104] constructed a checklist of 14 items assessing the reliability (organic actions) and relevance (cosmetic actions) of information presented in sustainability reports. Li et al. [101] identified 8 elements characterizing symbolic actions and 6 describing substantive ones. Van der Ploeg and Vanclay [6] employed a ten-question checklist to assess whether reports provided balanced information, including negative environmental impacts, arguing that a high proportion of descriptive over data-supported disclosures indicates potential symbolic legitimation strategies. Zhang et al. [105] proposed a checklist of 19 environmental disclosure items, specifying criteria for classifying each disclosure or corporate activity as symbolic or substantive. Subsequently, Zhang et al. [106] expanded this framework to 22 indicators, while Zhang et al. [107] further incorporated additional evidence such as certifications and quantified environmental achievements. Similarly, Xu et al. [103] applied a 17-item checklist addressing the readability, reliability, and completeness of sustainability disclosures, defining explicit criteria for categorizing statements as symbolic or substantive.

A slightly different approach to classifying corporate sustainability actions as symbolic or substantive was proposed by Costa et al. [108]. The authors employed the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) framework to identify and categorize disclosure indicators. Based on these standards, they developed a checklist of GRI indicators and subsequently evaluated each disclosure item in sustainability reports to determine whether it was presented in a narrative (symbolic) form or as verifiable quantitative or performance-based (substantive) information.

In several studies, a linguistic–textual classification was applied to distinguish between symbolic and substantive sustainability actions. For example, Khalil and O’Sullivan [24] differentiated between the two by examining the linguistic structure of ESG narratives, including the number of sentences and words related to environmental and social topics, under the assumption that a higher proportion of symbolic expressions indicates a greater likelihood of greenwashing. Similarly, Huq and Carling [30] utilized natural language processing (NLP) techniques to quantify the number of substantive greenhouse gas (GHG) disclosures included in sustainability reports, interpreting a low proportion of evidence-based statements as indicative of symbolic reporting and potential greenwashing.

An overview of methods used for operationalizing greenwashing in sustainability reporting based on symbolic and substantive dimensions is presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Methods for Operationalizing Greenwashing in Sustainability Reporting Based on Symbolic and Substantive Dimensions.

Our analysis indicates that, within this group of studies, greenwashing was most frequently quantified as the discrepancy between symbolic and substantive sustainability disclosures [101,102,105,108] or as the ratio of symbolic to substantive elements in sustainability reporting [103,106,107]. Some researchers examined this phenomenon indirectly through disclosure quality indicators, where a greater emphasis on relevance (cosmetic efforts) relative to reliability (organic efforts) was interpreted as indicative of symbolic reporting and potential greenwashing [104]. Other studies identified greenwashing through the dominance of symbolic disclosures over substantive ones [24,30], or by observing a prevalence of declarative statements (symbolic actions) over verifiable data (substantive actions) [6]. Collectively, these findings suggest that symbolic sustainability communication not supported by verifiable progress may serve as a deliberate impression management strategy, representing greenwashing in corporate sustainability reporting.

Although all methods aim to detect the gap between symbolic and substantive disclosures, they operationalize this gap differently. Manual approaches provide detailed, context-sensitive assessments but are highly time- and resource-intensive. Automated methods (e.g., NLP, text mining) enable large-scale analysis and efficient analysis but may overlook subtle linguistic and contextual nuances. These approaches are therefore best seen as complementary: manual coding can be used to train and validate automated tools, thereby combining interpretive accuracy with computational scale. The optimal method ultimately depends on research objectives and resource constraints—automated techniques are well suited for large cross-sectional studies, whereas manual checklists are preferable for in-depth analyses of individual reports or small samples.

3.2.3. Selective and Manipulative Disclosure Approach

A third approach to measuring greenwashing in sustainability reporting focuses on how companies present ESG-related information. Within this research stream, greenwashing is operationalized through the detection of selective disclosures and expressive manipulation of the content of sustainability reports. Selective disclosure is defined as a company intentionally emphasizing positive ESG achievements while omitting or downplaying negative aspects of its operations [109,110,111,112,113,114]. Expressive manipulation, on the other hand, involves using a promotional tone, emotional language, or biased narrative to influence stakeholder perceptions and create a favorable, yet potentially misleading, impression of the company’s actual ESG activities and performance [111,112].

Our SLR revealed that selective disclosure and expressive manipulation were most commonly identified using checklist-based manual coding, in which ESG topics were classified as disclosed or omitted and further distinguished as symbolic or substantive. In these studies, selective disclosure was typically measured as the proportion of omitted ESG items relative to the total number of expected disclosures, while expressive manipulation was quantified as the ratio of symbolically disclosed items to all disclosed items [106,107] or as the ratio of symbolic to substantive disclosure elements [115]. The overall greenwashing level was often computed as the geometric mean of the selective disclosure and expressive manipulation levels [115,116,117].

Other researchers applied rubric-based coding frameworks, using author-designed diagnostic questions [109] or custom indicators [118] specifically developed to detect narrative exaggeration, unverifiable claims, and selective omission of sustainability information.

Another method for detecting greenwashing applies GRI-indicator-based manual coding, in which disclosures are classified as “good news,” “neutral news,” or “bad news,” and companies are subsequently evaluated on whether they systematically downplay or omit unfavorable information while emphasizing positive disclosures [110].

Selective disclosure and expressive manipulation have also been examined using linguistic–textual methods. These methods relied on keyword frequency analysis and sentiment analysis to detect inflated positive language and patterns of symbolic communication [112,113]. They also combined lexicon-based techniques with stylistic and syntactic coding to capture narrative tone and discursive bias [111]. Finally, Yu et al. [114] applied a computational similarity-based method, demonstrating that templated sustainability statements with high textual similarity scores indicate generic and repetitive disclosure practices intended to obscure substantive performance.

An overview of methods used for operationalizing greenwashing in sustainability reporting based on selective and manipulative disclosure is presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Methods for Operationalizing Greenwashing in Sustainability Reporting based on Selective and Manipulative Disclosure.

In summary, selective and manipulative measurement approaches share a common conceptualization of greenwashing—emphasizing positive information while omitting negative information—but differ in how they quantify the phenomenon and in their sensitivity to detecting it. Checklist-based methods offer transparent assessments of selective disclosure and symbolic claims but are difficult to scale. Linguistic and NLP-based methods capture rhetorical cues such as tone, readability, and narrative patterns, though their accuracy depends on model quality and may produce results that diverge from checklist-based evaluations. Consequently, the literature increasingly views these methods as complementary: measuring both what is disclosed and how it is disclosed provides distinct yet mutually reinforcing insights into the multidimensional nature of greenwashing.

3.3. Analytical Techniques for Detecting Greenwashing in Sustainability Reporting Using Content Analysis

3.3.1. Detecting Greenwashing in Sustainability Reporting Through Tone Analysis

An expanding line of research examines how the tone of sustainability reporting—captured through linguistic and sentiment cues—functions as a proxy for detecting greenwashing.

Based on Diction 6.0, Fisher et al. [119] analyzed six forms of tone—positivity, activity, optimism, certainty, realism, and commonality—as potential measures of obfuscation in corporate narratives. However, they found no evidence that tone was used for obfuscation; instead, they observed the opposite effect. In contrast, Esterhuyse and du Toit [120] examined narrative tones (certainty, optimism, activity, realism, and commonality) in large multinationals’ human rights disclosures using Diction 7.1.3. They found that low-disclosure companies disproportionately relied on an optimistic tone—particularly using terms denoting satisfaction and inspiration—thereby signaling assertive impression management strategies. Drawing on the AFINN dictionary for word-level sentiment classification, García-Sánchez [69] also identified the use of impression-management practices in sustainability communication strategies.

Adopting a slightly different approach, Zharfpeykan [110] assessed Australian companies’ environmental and social disclosures, ranging from omission to fully quantified reporting of positive, negative, or neutral news, including violation-versus non-violation-related information. The study found that companies tended either to report representatively (balancing favorable and unfavorable items) or to engage in greenwashing by downplaying high-impact negatives while emphasizing less relevant positives. Using standard natural-language processing techniques, Gorovaia and Makrominas [113] applied supervised sentiment analysis (positive/neutral/negative) to examine how a CSR report’s environmental score—defined as a text-based measure of environmental emphasis—relates to positivity metrics, thereby evaluating two greenwashing mechanisms: decoupling and attention deflection. Martínez-Ferrero et al. [74] further demonstrated that companies with the worst CSR performance, when using an obfuscation-based disclosure strategy, provide less balanced reports that emphasize overly optimistic content. In addition, Conrad and Holtbrügge [121] showed that decoupling companies use fewer emotional references, more self-references, and fewer mentions of risk and anxiety, while relying more heavily on masculine-coded language.

Some studies restrict their analysis to counts of positive and negative words, thereby suggesting that an overly optimistic tone may indicate greenwashing [122]. Building on Huang et al. [123], Hamza and Jarboui [124] employed a more elaborate method, assessing tone management in French companies’ sustainability reports by counting positive and negative terms using the French version of Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count dictionary. They decomposed tone into a normal component, reflecting neutral descriptions, and an abnormal component, indicating the strategic use of tone management to inform or mislead stakeholders. Liao et al. [125] adopted a similar approach, analyzing the net positive tone of ESG reports (based on positive and negative dictionary of Tsinghua University) by Chinese listed companies and arguing that companies that “talk more and work less” engage in tone management—i.e., greenwashing. Liang and Wu [126] also applied this approach, using the “Bag of Words” method and textual analysis of CSR reports from Chinese listed companies, and suggested that companies may engage in greenwashing through the use of an abnormally positive tone in their CSR disclosures.

An alternative approach was proposed by Chen and Ma [91], who used the Term Frequency–Inverse Document Frequency algorithm and derived an “ESG greenwashing tone” from the frequencies of positive and negative emotion words and assessed greenwashing as the discrepancy between that tone and the firms’ ESG performance. Chen et al. [92] similarly computed decoupling as the difference between an ESG report’s optimistic tone—estimated using the Loughran–McDonald lexicon—and actual ESG performance, with both quantities standardized to z-scores, such that larger values indicate greater decoupling. A similar approach was employed by Sauerwald and Su [93] and Zhang [94], who linked the optimistic tone of CSR-reports to corporate social performance; however, Zhang [94] cautioned that relying on the tone–performance gap as a proxy for CSR decoupling has notable limitations.

3.3.2. Detecting Greenwashing in Sustainability Reporting Through Readability Analysis

Readability analysis of sustainability reporting aids in detecting greenwashing by examining sentence length, word complexity, jargon use, and overall clarity, which may reveal when complex or technical wording is strategically employed to obscure weak CSR performance. Some studies treat greenwashing and report readability as distinct constructs yet find a significant negative association, indicating that lower readability corresponds to higher levels of greenwashing [127]. However, several studies directly infer greenwashing and obfuscation from the readability metrics in sustainability reports.

Liao et al. [125] suggested that companies engage in greenwashing of ESG reports by “talking more and doing less,” as evidenced by textual analysis of ESG-related word frequencies relative to overall report length (based on Loughran–McDonald’s word list). A study by Esterhuyse and du Toit [120] revealed that low-disclosure companies engaged in obfuscation by reducing report readability, as measured by the Flesch Reading Ease Index, which accounts for average sentence length and syllables per word. Using the same index and based on the Textstat library, Gorovaia and Makrominas [113] quantified the readability of CSR reports and interacted it with the environmental score to examine greenwashing mechanisms. In turn, Fabrizio and Kim [128] analyzed voluntary responses to CDP’s Climate Change Survey to investigate linguistic obfuscation in environmental disclosures, using the Lingua::EN::Fathom package in Perl and the Gunning Fog Index to measure text complexity based on syllables per word and words per sentence. Martínez-Ferrero et al. [74] showed that companies with poor CSR performance employ obfuscation strategies by producing longer, less readable reports containing less accurate and transparent information. They assessed report accuracy and clarity using metrics such as the total number of pages and words, the ratio of numerical characters to total characters and words, and highlighted that “soft” information (text) is more cognitively demanding to process than “hard” information (numbers).

Some studies use multiple metrics to assess the readability of sustainability reports. For example, Fisher et al. [119] analyzed corporate accountability disclosures using Flesch Reading Ease as the primary index, complemented by the Flesch–Kincaid, SMOG, and Gunning Fog. Similarly, Nazari et al. [129] applied a comprehensive set of readability and disclosure-size measures—Flesch Reading Ease, Flesch–Kincaid Grade Level, Gunning Fog, Coleman–Liau, SMOG, and the Automated Readability Index—and found that shorter, less readable CSR disclosures were associated with poorer CSR performance, thereby suggesting the presence of greenwashing. Nilipour et al. [130] found that longer sustainability reports tend to have lower readability scores. Drawing on the ReadablePro online readability tool and using five readability indices (Flesch-Kincaid, Gunning Fog, Coleman-Liau, SMOG, and Automated Readability Index), they suggested that information overload and reduced readability may serve to obfuscate negative information. Wang et al. [25] suggested that companies with poor CSR performance may engage in greenwashing by employing complex language to produce vague reports, thereby minimizing the risk of adverse stakeholder reactions. To assess the readability of CSR reports, they applied three indices–Fog, Flesch, and Kincaid–to evaluate the overall difficulty of comprehension.

In a slightly different approach, Conrad and Holtbrügge [121] used Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count software (LIWC2015) to analyze morphology, syntax, semantics, and pragmatics in sustainability reports, finding that decoupling companies employ less cognitively complex language and exhibit lower linguistic sophistication. Using the same software, Corciolani et al. [131] measured analytical and authentic language in CSR reports and showed that greater involvement in corporate social irresponsibility is associated with more narrative (as opposed to analytical) and more deceptive (as opposed to authentic) language.

It should also be noted that, using machine learning and text analysis, Pan et al. [132] identified an inverted U-shaped relationship between environmental performance feedback and the readability of CSR reports among Chinese SMEs. In this case, readability was operationalized using a word2vec CBOW model trained on CSR reports to predict target words from their surrounding context.

3.3.3. Detecting Greenwashing Through Visual Imagery Analysis

Considering how visual elements can be leveraged to influence sustainability reporting, Friedel [79]—in one of the first studies in this field—argued that the strategic use of imagery in CSR reports, such as depictions of Indigenous bodies and landscapes, was designed to alleviate public concerns about the environmental impacts of fossil fuel production and may represent a distinct form of greenwashing. Hrasky [133] examined the number, size, and types of graphs and photographs related to the three dimensions of sustainability—economic, social, and environmental. The analysis revealed that sustainability-oriented companies used fewer photographs and relied more on quantitative data presented in graphical form within sustainability reports to highlight measurable impacts. In contrast, less sustainable companies pursued symbolic legitimacy, using imagery lacking concrete action as a greenwashing tool in sustainability communication with stakeholders. Cho et al. [80] identified the enhancement strategy by examining whether a significantly larger proportion of graphed items in sustainability reports displayed favorable trends. Additionally, they assessed obfuscation by identifying graphical distortions that presented favorable information, thereby serving as tools for impression management. A similar approach was adopted by Cüre et al. [81] to identify enhancement and obfuscation as impression-management strategies, analyzing graphs with both favorable and unfavorable trends and detecting visual distortions used to manipulate perception.

3.3.4. Evidence of Real Greenwashing

While the existing greenwashing literature predominantly addresses alleged or theoretical cases, only a small subset examines instances that have been empirically verified.

Examining the Deepwater Horizon oil spill, Mobus [134] analyzed BP’s pre-crisis CSR disclosures on environmental and safety performance, thematic trends in newspaper coverage during the crisis, and post-crisis findings on contributing conditions, thereby demonstrating the risks of relying on self-reported sources that provide strong incentives to emphasize favorable information while omitting adverse details. Du [135] used the Greenwashing Identification Committee’s list—published by South Weekend, one of China’s most influential newspapers—to detect greenwashing, thereby demonstrating that this list can serve as an empirical verification tool for confirmed cases. Using content analysis and comparative evaluation of CSR reports against external data on Foxconn, Noronha and Wang [13] identified a disclosure–performance gap attributed to greenwashing. This gap stemmed from selectively highlighting positive aspects while omitting negative social performance details, particularly in cases involving incomplete disclosure and non-compliance with reporting guidelines. Analyzing the Volkswagen emissions scandal, Siano et al. [12] compared the Volkswagen Group’s CSR reports with media coverage exposing the “Dieselgate” controversy—representing the public revelation of greenwashing—and identified false claims and deliberate manipulation within these reports. Contreras-Pacheco and Claasen [136] identified clear signals of fuzzy reporting as a form of greenwashing. They examined the environmental disaster through events before, during, and following the incident, focusing on the company’s disclosure practices, and found that the firm adapted its narrative over time to align with changing stakeholder expectations. In a related vein, Roszkowska-Menkes et al. [9] identified forms of selective disclosure by analyzing companies involved in severe controversies and assessing whether, and to what extent, these controversies and their associated negative events were reported in sustainability disclosures. Corciolani et al. [131], analyzing evidence of negative impacts on human rights, demonstrated how the language of CSR reports can be strategically used to offset companies’ involvement in corporate social irresponsibility (CSIR). Finally, Gorovaia and Makrominas [113] analyzed how penalized environmental violations influence CSR report readability and sentiment, observing that violating companies tend to adopt a more assertive and overly positive tone while disclosing larger volumes of environmental information—resulting in reports that are more extensive yet less readable.

3.3.5. Oversimplified Assumptions of Greenwashing in Sustainability Reporting

In our opinion, some studies are built on assumptions that oversimplify the detection of greenwashing in sustainability reporting.

Some scholars assume that merely issuing CSR reports by companies with poor corporate social performance—or exhibiting a low degree of conformity with the GRI Sustainability Framework and Standards—constitutes evidence of greenwashing, consistent with a symbolic management approach [137]. In this context, Karaman et al. [138] argued that the presence of greenwashing tendencies in the energy sector could be dismissed, as companies with superior CSR performance were more likely to issue CSR reports. Similarly, Koseoglu et al. [139] found that high-performing companies in the hospitality and tourism industry were more likely to publish CSR reports, adopt the GRI framework, and obtain external assurance—thereby providing grounds for rejecting the greenwashing hypothesis in that sector. Mahoney et al. [140] posited—consistent with a signaling theory perspective—that stronger CSR performers issue reports to signal genuine commitment to sustainability, whereas weaker performers use them to project an image of responsibility despite poorer records, thereby engaging in greenwashing. However, it should be noted that none of these three studies employed content-analysis-based methods, which limits their ability to directly assess communicative or linguistic indicators of greenwashing.

Taking into account other studies that, in our view, also oversimplify greenwashing detection in sustainability reporting, Lewis [141] argued that multinational corporations may be accused of greenwashing if they either omit any discussion of their supply chain’s environmental impact or report on it only at the level of values and goals, without providing substantive or verifiable details. Additionally, drawing on an assessment of the quality of sustainability disclosures among Australian companies, Zharfpeykan and Akroyd [142] argued that companies tend to adopt greenwashing strategies when the quality of disclosures on material issues either declines or fluctuates—patterns suggesting attempts to obscure weak social and/or environmental performance.

4. Directions for Future Research

Our SLR reveals significant research gaps and unresolved questions that can guide future investigations. While previous studies have provided valuable insights, several areas remain underexplored and warrant more rigorous scholarly attention.

Overall, adopting a mixed-methods approach that integrates qualitative and quantitative techniques is crucial. It enhances methodological rigor, captures the multifaceted nature of greenwashing analysis, and addresses the lack of qualitative depth inherent in purely quantitative designs.

The analyzed studies indicate that companies may adopt diverse—and often mixed—greenwashing strategies in sustainability reporting, ranging from purely symbolic to substantive actions, or combinations of both. However, existing research frequently oversimplifies these practices, limiting our understanding of how greenwashing manifests across different strategic approaches [10]. Future studies should address this gap by systematically aligning narrative disclosures with verified performance metrics using supervised machine-learning methods, and by employing longitudinal or case-based designs to trace strategic combinations, shifts, and manipulative practices over time. Despite substantial progress in conceptualizing strategic typologies of greenwashing—ranging from distinctions between symbolic and substantive legitimacy management [70] to impression-management frameworks such as enhancement and obfuscation [80,81] or deceptive manipulation [12]—the literature continues to focus predominantly on observable communications and reporting artifacts. It pays less attention to internal organizational processes that generate them. Much of the current understanding derives from textual, visual, or case-based inferences [26,67,74], making it difficult to link specific communicative approaches to concrete decision-making rules within companies. Future research should therefore combine primary data, governance documents, and assurance workpapers to trace how corporate “talk” is generated, by whom, and for what purposes. It should also aim to develop validated tactic-to-signal dictionaries that connect internal routines with external reporting outcomes. Another notable gap concerns the under-measurement of silence. While existing typologies richly describe what companies disclose—for example, camouflaging strategies in controversial industries [68,73]—they are less effective at identifying greenhushing, or strategic nondisclosure, which often escapes text-based analyses. Studies documenting defensive legitimation and denial frames [75,76] suggest that the boundary between selective speech and deliberate silence is blurred; yet, systematic measures of omission remain scarce. Future research should therefore model disclosure decisions at the margin—examining what is omitted and why—by combining anonymous managerial surveys with gap analyses between internal practices and external reporting. Existing research predominantly focuses on listed companies in developed markets, often within single industries or national contexts [67,68,73], whereas evidence on small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) and companies in emerging economies remains limited. Strategic frameworks explicitly distinguish between “talk” and “walk” [10] or classify disclosure–performance consistency [63,64,65], highlighting substantial heterogeneity across organizational and institutional contexts. Comparative research designs should therefore investigate how specific constraints—such as reporting costs, liability risk, and supply-chain opacity—influence the selection of disclosure tactics, particularly in sectors where hidden trade-offs are most prevalent. In addition, causal evidence regarding the mechanisms that effectively curb greenwashing remains limited. The existing literature often posits that assurance or regulatory pressure can discipline reporting practices [72]; however, robust empirical tests—particularly those distinguishing between limited and reasonable assurance, or between in-scope and out-of-scope emissions—remain scarce. This includes investigating how greenwashing practices and stakeholder perceptions evolve over time and across regulatory contexts. The field would benefit from applying quasi-experimental designs such as difference-in-differences or interrupted time-series approaches, leveraging changes in assurance coverage or regulatory adoption. These should be combined with hybrid human–large language model (LLM) coding frameworks capable of capturing both linguistic and visual dimensions of disclosure tactics. The growing use of LLM-assisted writing introduces both risks and opportunities. Generative tools may homogenize tone, amplify optimism bias in corporate sustainability discourse [26], and reinforce identity-management effects [73]. Conversely, when coupled with transparent codebooks, human adjudication, and validation against objective outcomes, these tools can also enhance the detection of greenwashing. Advancing from proxy-based measures to ground-truth evidence will require the creation of labeled repositories containing report excerpts, graphics, and internal artifacts. Such datasets would enable predictive tests linking specific reporting approaches to subsequent organizational or environmental outcomes.

Recent studies increasingly measure greenwashing through content analysis by examining discrepancies between corporate sustainability disclosures and actual ESG performance. However, empirical evidence indicates that estimates of greenwashing vary substantially depending on the data source used for performance evaluation and the assumed time lag between disclosure and realized outcomes [84,89]. Future research should employ distributed lag models and integrate multiple independent sources of ESG performance data to enhance the reliability and validity of greenwashing assessments. Moreover, existing research has predominantly focused on the environmental pillar, providing limited insight into greenwashing within the social and governance dimensions. It is therefore essential to examine the consistency of disclosure–performance gaps across all ESG pillars and to explore contextual moderators that may influence such decoupling [1,88]. Another promising but underexplored avenue concerns the regulatory effectiveness and auditability of disclosure–performance gap metrics [87]. Future research should investigate whether the introduction or strengthening of disclosure obligations reduces these gaps and which ESG components are most responsive. Moreover, many studies rely on unvalidated coding schemes or subjective classifications methods, raising concerns regarding the construct validity and replicability of greenwashing indicators derived from content analysis. More systematic validation procedures, coupled with the increased application of natural language processing and AI-based techniques, are needed to improve the methodological rigor of future analyses [86,95].

The symbolic–substantive approach to measure greenwashing also faces several limitations that warrant further research. One major challenge concerns the lack of consistency in how symbolic and substantive disclosures are operationalized. Existing studies employ divergent classification rules, which may yield inconsistent conclusions depending on the coding schemes, linguistic contexts, and sectoral characteristics applied [6,24]. Future research should prioritize the development of unified coding frameworks, assess their cross-contextual stability, and validate them across multilingual corpora and industry segments using measurement-invariance techniques.

Another underexplored area involves the role of stakeholder perceptions in mediating the classification of symbolic versus substantive ESG claims. Current studies often assume homogeneous interpretive frameworks, overlooking how investors, NGOs, regulators, or consumers may differentially interpret identical disclosures [103,107]. Behavioral experiments and stakeholder-centered conjoint analyses could provide valuable insights into these perception gaps. Institutional and internationalization dynamics also warrant deeper examination. Current research provides limited evidence on how a company’s degree of internationalization and institutional context influence the symbolic or substantive nature of ESG communication [101,104]. Future research could explore how external pressure and legitimacy demands jointly shape disclosure behavior. Moreover, most current analyses focus on isolated narrative fragments—such as specific phrases or report sections—rather than evaluating the broader alignment between the company’s overall discourse and verified ESG outcomes. This narrow focus constrains the ability to detect symbolic decoupling at scale. Future research should adopt more comprehensive, firm-level approaches that link entire report contents to quantifiable performance indicators [102,108]. Digital transparency tools and emerging technological systems also merit greater attention. While some recent studies acknowledge the growing adoption of digital reporting mechanisms, empirical evidence on their impact remains scarce [30,107]. Future research could examine whether tools such as real-time ESG dashboards, structured data reporting, and algorithmic monitoring reduce company’ capacity to engage in symbolic disclosure.

Detecting greenwashing through selective disclosure and narrative manipulation likewise represents a rapidly developing research area. Yet, a key limitation lies in the absence of standardized procedures for identifying and classifying such practices across industries, languages, and coding systems. Current studies often rely on heterogeneous textual metrics without confirming measurement invariance, which undermines comparability and replicability [111,116,118]. Future research should aim to establish unified codebooks and multilingual natural language processing (NLP) pipelines, complemented by manual validation of sampled text segments to ensure methodological robustness. The role of institutional investors in shaping information opacity also remains underexplored. Although prior studies have pointed to the potential emergence of “disclosure fog” in ESG communication, few have empirically examined whether institutional ownership correlates with hedging language, lexical dilution, or selective ESG narrative construction [107,112]. A promising avenue for future research involves exploring whether and how companies imitate competitors’ selective disclosure strategies. Textual similarity measures could help detect industry-specific patterns of imitation—such as linguistic convergence in phrasing, tone, or narrative structure [114,117]. Additionally, further investigation is needed into the strategic manipulation of ESG topic emphasis, wherein companies may disproportionately highlight less material or less scrutinized themes. Empirical evidence remains limited regarding whether such shifts in topic salience reflect deliberate narrative avoidance [109,115]. Future studies should apply systematic text-analytic approaches to detect and evaluate the prevalence and implications of these distortive practices in sustainability reporting.