Abstract

In response to UNESCO’s call to integrate sustainability into curriculum design, this study examines the structure of ecological physical education (PE) objectives in China and South Korea and how these patterns reflect different approaches to Education for Sustainable Development (ESD). Using a dual-dimensional framework integrating Weber’s instrumental–value rationality distinction and Hauenstein’s Taxonomy of Educational Objectives, this study conducts a qualitative comparative analysis of ecological PE objectives from the 2022 national curricula of China and South Korea. The analysis focuses exhaustively on the ecological modules within these curricula rather than the full set of PE standards. The findings indicate that China’s curriculum exhibits a linear, standardisation-oriented progression, with objectives concentrated in the Acquisition and Performance levels (31.6% each) and no Accomplishment-level objectives, suggesting limited formal pathways for higher-order ecological enactment. In contrast, South Korea’s curriculum shows a value-oriented spiral progression, with objectives spanning Assimilation (23.5%), Adaptation (58.8%), and Accomplishment (11.8%) levels, suggesting alignment with national sustainability policies. The study proposes the Skill–Ethics Equilibrium framework as an integrative model that synthesises the complementary strengths of both systems, offering dual optimisation pathways: one to strengthen ethical enactment in China and another to enhance evaluative clarity in Korea. This framework provides a theoretically grounded heuristic for advancing ESD-aligned ecological PE in diverse educational contexts.

1. Introduction

Ecological physical education (PE)—understood as a curricular approach that integrates environmental ethics, embodied ecological awareness, and responsible behavioural engagement into physical activity—has become an increasingly prominent focus in global curriculum reforms [1,2,3]. Within this domain, ecological sports serve as a key pedagogical vehicle. These sports constitute a primary form of the ecological practices through which PE can advance broader sustainability goals. Within UNESCO’s agenda for Education for Sustainable Development (ESD), which calls on education systems to “address ecological challenges” [4,5], the role of PE is shifting from solely training motor skills toward a more comprehensive model that uses ecological practices as a vehicle for fostering ecological citizenship, social responsibility, and interdisciplinary sustainability competencies [6,7]. As a highly experiential and context-rich domain, PE provides a unique platform for connecting bodily movement with environmental responsibility, thereby contributing to ESD-oriented educational transformation [8,9,10].

Although China and South Korea share broader East Asian cultural traditions, their national PE curricula exhibit distinctly different orientations toward ecological education. China’s Compulsory Education Physical Education and Health Curriculum Standards (2022) [11] emphasise standardised, quantifiable objectives shaped by instrumental rationality [12], operationalised through a level-based grading system. In contrast, South Korea’s Physical Education Curriculum (2022) [13] is informed by value rationality [14], embedding ecological commitments within its three-dimensional knowledge–skills–values framework. Its structural emphasis is broadly consistent with national sustainability initiatives such as the Korean Green New Deal and the Carbon Neutrality Strategy 2050 [15,16,17,18]. These contrasts reflect a pedagogical tension between measurable skill efficiency and the cultivation of ethical–ecological dispositions, underscoring the need for an integrated analytical framework.

To address this tension, the present study integrates Weber’s dualism of instrumental rationality and value rationality [19] with Hauenstein’s taxonomy of educational objectives [20,21] to form a dual-dimensional analytical lens for examining ecological PE objectives.

Ultimately, the study aims to move beyond descriptive comparison by developing a Skill–Ethics Equilibrium framework that offers a balanced pathway for reconciling technical proficiency with the normative aims of sustainability education. Guided by the structural characteristics of ecological PE objectives in both countries, this study focuses on the following core questions: How do the structural frameworks of ecological PE curriculum objectives in China and South Korea differentially manifest “skill–bearing attributes” (e.g., standardisation and quantification) and “cultural construction attributes” (e.g., ethical internalisation and contextual Adaptation)? How do China’s “level-based grading system” and South Korea’s “grade-level integration system” achieve objective stratification, employing distinct progression logics and reflecting their respective national policy orientations?

2. Theoretical Framework and Research Methodology

2.1. Theoretical Framework

The analytical framework integrates Hauenstein’s Taxonomy of Educational Objectives [20] with Max Weber’s distinction between instrumental rationality and value rationality [19]. This theoretical combination provides a structured analytical lens for examining how ecological physical education (PE) objectives encode both behavioural expectations and the underlying rational motivations that shape them. It is crucial to note that this framework serves as an interpretive tool for comparative analysis, not as a set of predetermined conclusions.

2.1.1. Rationale for Adopting Hauenstein’s Taxonomy

Hauenstein categorises educational objectives into four domains (cognitive, affective, psychomotor, and behavioural), with the behavioural domain synthesising elements of the preceding three [21]. Its five progressive levels—Acquisition, Assimilation, Adaptation, Performance, and Accomplishment—offer a nuanced structure for distinguishing foundational knowledge recall from complex behavioural enactment and internalised ethical practice. For instance, while the Acquisition level may involve stating basic movement or outdoor-activity terminology, the Accomplishment level reflects consistent value-driven behaviour, such as choosing environmentally considerate actions in school sports settings. Given the domain’s emphasis on observable praxis, Hauenstein’s Taxonomy is well-suited for analysing the intersection between skill standardisation and ecological–ethical internalisation in national PE curricula.

2.1.2. Theoretical Integration: Mapping Rationalities to Hauenstein’s Levels

Instrumental rationality—emphasising efficiency, standardisation, and quantifiable outcomes—conceptually aligns with the lower and intermediate behavioural levels, where objectives commonly prioritise skill mastery, procedural accuracy, and measurable performance [22]. Conversely, value rationality—centred on intrinsic meaning, ethical commitment, and context-sensitive decision-making—corresponds more strongly to the higher levels of the taxonomy, where learners adapt behaviours to ecological or social contexts and ultimately demonstrate internalised responsibility [19]. Crucially, this mapping reflects an analytical expectation derived from the conceptual properties of each rationality type, not an empirical conclusion. These theoretical associations are translated into explicit coding definitions, as summarised in Table 1, which served as the basis for coding the curricular objectives in subsequent analyses.

Table 1.

Operational Definitions for Behavioural Levels in Hauenstein’s Taxonomy with Examples.

2.2. Research Methodology

This study follows a cross-cultural comparative design and employs qualitative content analysis guided by the integrated theoretical framework [23]. The methodological procedures—from corpus construction to coding and validation—were designed to ensure transparency, replicability, and interpretive validity.

2.2.1. Data Corpus Construction

The dataset comprises the most recent national PE curriculum standards from China and South Korea: China’s “Compulsory Education Physical Education and Health Curriculum Standards (2022 Edition)” [11] and South Korea’s “Physical Education Curriculum (2022)” [13]. The modules included in the two international standards are as follows:

- China: 19 objectives from the ‘Emerging Sports’ module (Levels 2–4).

- South Korea: 17 objectives from the ‘Ecological Sports’ module (Grades 3–4, 5–6, and middle school).

Within China’s “Emerging Sports” module, several activities—such as orienteering, wilderness survival, nature trekking, mountaineering, and climbing—are conducted predominantly in natural outdoor environments and require direct engagement with ecological settings. These survival- and exploration-oriented components represent the densest concentration of nature-based content in the Chinese PE Standards, making the module directly comparable to Korea’s “Ecological Sports” module.

Focusing on module-level ecological objectives ensures that both datasets share a coherent pedagogical orientation. Although the corpus includes 36 objectives, the extraction is exhaustive within the targeted ecological modules, making it appropriate for structural and interpretive comparison rather than statistical generalisation.

2.2.2. Coding Procedure and Reliability Assurance

The analysis followed a multi-stage coding procedure. First, a detailed coding protocol was developed to operationalize the theoretical framework, translating Weber’s types of rationality and Hauenstein’s behavioural levels into explicit indicators (Table 1). To calibrate the application of this protocol, a pilot exercise was conducted. Prior to any discussion, the two coders independently coded a subset of four objectives. Initial agreement was reached on 3/4 behavioural-level assignments and 2/4 rationality-orientation assignments. Given the inherently interpretive nature of classifying rationality orientations, this level of convergence provided a solid foundation for the subsequent consensus discussions.

Following this calibration, the two researchers then independently coded all 36 curriculum objectives. Both coders were doctoral researchers in physical education with professional certifications in outdoor and adventure sports, as well as relevant teaching experience. This expertise, combined with their familiarity with the national curriculum frameworks of both countries, provided strong interpretive grounding for the analysis.

When ambiguities arose during the independent coding—particularly in composite objectives or statements with dual emphases such as “valuing sports environments and stewarding community resources”—a consensus-building approach was applied. This iterative discussion method prioritised interpretive validity, enhancing the overall trustworthiness of the final coding. Such consensus procedures are widely recommended in qualitative content analysis to strengthen credibility [24,25].

2.2.3. Differential Analysis and Case Anchoring

Coded data were analysed in two complementary ways.

- A quantitative distribution analysis calculated the proportional allocation of objectives across Hauenstein’s five behavioural levels for each country.

- A qualitative case analysis examined emblematic objectives to illustrate how instrumental-rational orientations or value-rational orientations manifest in curriculum language and structure.

This mixed-mode approach ensures both structural clarity and contextual depth. Representative coding examples, including ambiguous or borderline cases, are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Theoretical Framework Instantiation with Curriculum Examples.

2.3. Coding Framework and Illustrative Examples

To ensure transparency and replicability, this section outlines the dual classification process used to determine: (a) each objective’s rationality orientation, and (b) its corresponding behavioural level.

2.3.1. Classifying Rationality Orientation

The rationality orientation of each objective was determined through its dominant linguistic and conceptual emphasis:

- Instrumental rationality was identified through markers such as quantitative benchmarks, efficiency-focused verbs, and standardised skill formulations (e.g., “execute,” “master,” “organise”).

- Value rationality was identified by references to ecological attitudes, ethical conduct, and community-oriented behaviour (e.g., “cultivate,” “appreciate,” “address collaboratively”).

2.3.2. Assigning Behavioural Levels (Hauenstein’s Taxonomy)

Each objective was assigned a behavioural level (based on Hauenstein’s Taxonomy) according to the complexity of the required behaviour and its alignment with the operational definitions in Table 1.

2.3.3. Illustrative Coding Examples

Occasionally, the objectives presented semantic ambiguities. For instance, the Korean objective “valuing sports environments and stewarding community resources” encompasses both attitudinal and behavioural components. Final level assignment was resolved through the consensus-building process described in Section 2.2.2, ensuring interpretive consistency across coding decisions. Representative examples—including borderline or multi-faceted objectives—are summarised in Table 2, demonstrating how the analytical framework was systematically applied across both curricula.

3. Comparative Analysis of Chinese and Korean Goals: Constituent Characteristics and Progressive Mechanisms

3.1. China: Instrumental Rationality-Dominated Linear Skill Closed-Loop

An analysis of the target composition using Hauenstein’s behavioural hierarchy (Table 3) reveals that China’s Compulsory Education Physical Education and Health Curriculum Standards (2022) [11] are oriented toward “skill standardisation,” a focus reflected in three structural characteristics.

Table 3.

Distribution of Hauenstein’s Behavioural Levels in Chinese and Korean Curricula.

First, a dual-peak distribution is evident: the Acquisition level (31.6%) and the Performance level (31.6%) together account for 63.2% of all objectives (Table 3). This pattern reflects a linear “basic skill input → advanced task execution” structure. For example, Level 2 objectives, such as “state basic movement terminology” (Acquisition level), and Level 4 objectives, such as “organise inter-class competitions” (Performance level), demonstrate a progression centred on technical mastery and task completion. However, ecological–ethical intentions are not explicitly embedded within these transitions. The complete absence of Accomplishment-level objectives (0%, Table 3) indicates limited attention to higher-order creative outcomes, such as designing eco-friendly activities. Ecological awareness appears only in fragmented or implicit forms—often subsumed under general “sports ethics” descriptors (e.g., “observe competition etiquette”).

Moreover, module fragmentation further weakens ecological coherence. Ecological elements tend to appear only superficially in the “safety protection” module. At the same time, substantive environmental content is confined to low-contact-hour sections (approximately 10%), such as “cross-disciplinary thematic learning” and “Health Education.” While this structure enhances within-module coherence, it may hinder cross-module integration and limit ecological meaning-making [26,27,28].

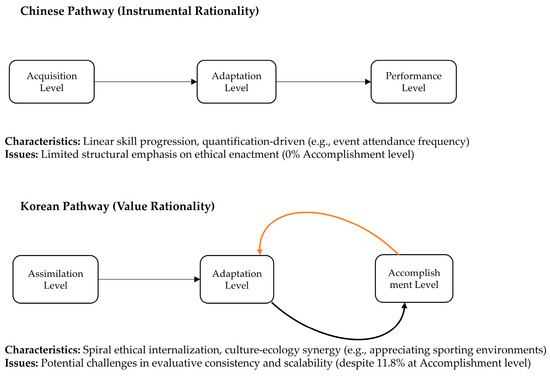

Second, regarding progression mechanisms, the level-based grading system reinforces a linear “Acquisition → Adaptation → Performance” trajectory, driven by quantifiable benchmarks (Figure 1). Level 2 emphasises foundational cognition and experiential engagement (e.g., “identify movement terminology”), with 100% of objectives located at the Acquisition level (Table 4). By Level 4, objectives shift toward complex performance tasks (e.g., “optimise sport-specific fitness parameters”), with 85.8% classified at the Performance level (Table 4). Although the progression from Level 2’s “engage in fitness games” (Acquisition level) to Level 4’s “optimise fitness levels” (Performance level) outlines a skill-standardisation-centred loop, it lacks explicit linkage to ecological–ethical objectives such as “assess venue ecological impact.” As a result, opportunities for value-oriented development during adaptation stages (e.g., Level 3’s “exhibit sportsmanship”) remain primarily technical rather than ethical.

Figure 1.

Contrasting curricular progression pathways: Skill standardisation vs. ethical internalisation.

Table 4.

Hierarchical Distribution and Progression Logic of Chinese Curriculum Objectives.

The curriculum’s emphasis on quantification fits within the broader discourse of national strategies such as the Sports Power Strategy and Healthy China 2030 (2019), such as physical fitness test pass-rate requirements [29,30]. Observable and easily measurable behaviours—such as “attend ≥8 sporting events per semester” or “skate through three obstacle types”—serve as major evaluation anchors. This efficiency-focused framework foregrounds tangible metrics (e.g., fitness test compliance) [31,32], creating a structural tension in which the dominance of instrumental rationality may marginalise value rationality. Although these quantifiable standards may help narrow regional disparities in resource allocation (e.g., standardised skating tasks), they constrain the ethical potential of Adaptation-level objectives (21.0% of objectives, Table 3), which become oriented toward technical refinement rather than ecological praxis. Consequently, such objectives do not readily translate into value-externalising behaviours, limiting alignment with UNESCO’s call to “cultivate ecological citizenship through education” [33,34].

3.2. South Korea: Value Rationality-Driven Internalisation of the Ethical Spiral

South Korea’s Physical Education Curriculum (2022) [13] adopts a three-dimensional knowledge–skills–values framework (Table 5). Through its grade-integrated design, this framework establishes a pathway for ethical internalisation grounded in value rationality. In moral psychology, this process of internalisation is conceptualised as the gradual incorporation of extrinsic values into one’s self-regulatory system [35]. The model comprises three interacting and complementary dimensions.

Table 5.

Hierarchical Distribution and Progression Characteristics of South Korea’s Curriculum Objectives.

First, in terms of target composition, the curriculum differs markedly from China’s instrumental rationality approach. The Adaptation level (58.8%) serves as a Skill–Ethics nexus, integrating technical adaptability with ecological sensitivity [36]. For instance, the Grades 5–6 objective “select context-appropriate equipment and strategies” requires learners to adjust activities in response to environmental conditions while demonstrating eco-conscious attitudes. Such objectives elevate Hauenstein’s Adaptation level from a focus on behavioural expectations to one that includes dual Skill–Ethics alignment. Second, explicit value externalisation at the Accomplishment level (11.8%) frames abstract ecological ethics in terms of observable, civically oriented actions. A representative example is the middle school objective “practice eco-friendly conduct; collaboratively address environmental challenges,” which positions athletic participation alongside other forms of community engagement. In this structure, the progression outlines a “knowledge → behaviour → values” continuum by foregrounding ethical principles within actionable practices. Third, the Assimilation level (23.5%) serves a cultural anchoring function, framing ecological awareness in relation to Korea’s ecological-sports heritage. Objectives such as “compare historical characteristics of ecological sports” encourage students to consider sustainable practices in traditional games (e.g., use of natural materials such as straw or bamboo). This resonates with Weber’s principle of value rationality, wherein meaning and cultural legitimacy underpin ethical orientations rather than external enforcement [37].

Regarding progression, the grade-integrated structure forms an “Assimilation → Adaptation → Accomplishment” spiral pathway (Figure 1) that is intended to support the gradual development from cultural cognition to civic agency. At Grades 3–4, cultural identity and resource reverence are positioned as being fostered through gamified learning (e.g., “develop rule-adherence attitudes,” Assimilation level, Table 5). At Grades 5–6, ecological sensitivity is framed as becoming connected with technical execution via objectives such as 6-02-12 (“sustain sporting environments,” Adaptation level, Table 5). At the middle school stage, ethical understanding is described as relating to forms of civic praxis, demonstrated by objectives such as 9-02-27 (“eco-friendly attitude,” Accomplishment level, Table 5). This scaffolded progression is depicted as encouraging ecological consciousness to move from norm internalisation toward applied innovation, illustrating how value rationality is conceptualised as operating.

In relation to policy discourse, the curriculum is presented as supporting praxis-based ethical internalisation. The curriculum exhibits a structure that resonates with national sustainability agendas, such as the Korean Green New Deal and Carbon Neutrality Strategy 2050 (2020) [38,39]. Middle school objectives (e.g., 9-02-20/23 “adapt to socio-natural environments”) echo the language and intent of policy documents like the Framework Act on Carbon Neutrality, suggesting a conceptual affinity with broader goals of ecological stewardship. This parallel suggests a potential synergy among culture, policy discourse, and educational design in promoting ecological citizenship [40].

3.3. Core Divergence: Contrasting Heuristic Archetypes—The Skill Closed-Loop vs. Ethical Spiral

Superimposing the two analytical frameworks (Figure 1) reveals a fundamental divergence, suggesting pedagogical expressions of two distinct modernisation priorities. This divergence can be crystallised into two contrasting heuristic (ideal-typical) archetypes. China’s instrumental rationality pathway forms a predominantly linear, skill–centred “Acquisition → Performance” closed loop. Its strength is often associated with supporting skill standardisation through quantifiable milestones embedded in the level-based grading system (e.g., “navigate three obstacle types while skating,” Table 6). This design may help reduce regional disparities in foundational motor skill attainment. However, this progression appears to exhibit limited ethical integration: ecological aims remain embedded primarily within ancillary modules (e.g., safety protection), and Level 4 objectives such as “coordinate cross-class competitions” emphasise operational completion rather than Accomplishment-level outcomes (e.g., resource circulation or venue ecological restoration).

Table 6.

Comparative Analysis of Goal Design Framework in China and South Korea.

Conversely, South Korea’s value rationality pathway establishes an “Assimilation → Adaptation → Accomplishment” ethical spiral, designed to foster culture–policy–education synergy. Its core contribution is often characterised as relating to situated forms of ethical generativity. At Grades 3–4, cultural identity and resource reverence are positioned as being reinforced through objectives such as “understand sports concepts through environmental interaction” (Assimilation level). By middle school, objectives such as “practice eco-friendly conduct; collaboratively address environmental challenges” can be interpreted as framing ethical norms in relation to forms of civic agency (Accomplishment level). Within this structure, the Adaptation level (58.8%) is presented as a pivotal link between technical execution and ethical intentionality, supporting the development of ecological consciousness through interlinked skill progression and value internalisation.

Figure 1 presents an analytical reconstruction of the dominant progression patterns. The Chinese pathway (top) illustrates a predominantly linear shift from Acquisition to Performance levels, reflecting an instrumental-rational orientation toward skill standardisation. The Korean pathway (bottom) depicts a spiral progression through the Assimilation, Adaptation, and Accomplishment levels, highlighting a value-rational orientation that emphasises ethical internalisation. Arrows indicate the primary direction of curricular emphasis across grade levels.

4. Discussion: Cross-National Learning and Theoretical Advancement

The comparative analysis can be interpreted as indicating that the structural divergences between the Chinese and Korean ecological PE curricula are not merely pedagogical variations but may reflect a broader tension within global Education for Sustainable Development (ESD). This tension can be analytically framed as arising between the need for standardised skill acquisition—which supports equitable access and measurable outcomes—and the aspiration to foster ethical internalisation for sustainable citizenship. The findings can be viewed as suggesting that China’s instrumental-rationality-oriented model, while often described as supporting equitable skill dissemination, may offer fewer explicit structural opportunities for the kinds of ecological meaning-making emphasised in UNESCO frameworks [33,34]. Conversely, Korea’s value-oriented approach can be interpreted as articulating a clearer pathway for ethical internalisation. However, its reliance on qualitative assessment and its relative cultural homogeneity may raise considerations regarding Adaptation across diverse educational settings. Building on these insights, this study is positioned as moving beyond dichotomous diagnoses to propose an integrative model that combines the strengths of both systems.

4.1. China’s Evolutionary Pathway: Embedding Ethical Enactment Capacity

The analysis indicates that China’s ecological-sports curriculum could benefit from adapting its unidirectional, skill-based, closed-loop approach, which characterises its instrumental-rational orientation. While retaining the merits of skill standardisation—particularly its role in supporting equitable outcomes—a complementary ethical progression pathway could enhance the curriculum’s ecological responsiveness. Drawing on insights from Korea’s ethical spiral, China could be seen as exploring the incorporation of more explicit ecological targets—particularly at the Accomplishment level—to engage with the structural gap identified in the analysis (0%; Table 3).

Institutionalising “ecological praxis” benchmarks at Level 4 may be interpreted as creating space for expanding predominantly technical objectives into contexts that foreground ethical enactment. For example, the existing Performance-level objective “organise inter-class competitions” could be expanded to include an ecological dimension, for instance, “design and coordinate resource-conscious athletic events,” which might involve basic evaluations of material use and waste-reduction strategies. Such an approach may be viewed as shifting ecological objectives from their current ancillary association with safety protocols toward a more integrated role in framing ecological meaning-making processes [41].

However, the adoption of such benchmarks would likely require consideration of systematic teacher training, curricular resources, and supportive evaluation mechanisms to ensure feasible and equitable implementation across regions. These conditions may be understood as important for supporting ethical enactment processes while maintaining the curriculum’s commitment to national standardisation.

4.2. South Korea’s Optimisation Path: Strengthening Quantitative Anchors and Resilience Assessment

The findings can be interpreted as suggesting that South Korea’s Ecological Sports curriculum, while demonstrating strong capacity for ethical internalisation, may be viewed as having scope for integrating selected operational features of China’s instrumental rationality approach to help establish a more balanced dual-track progression of skills and ethics. Such integration does not imply replacing qualitative orientations, but can be understood as complementing them with modest quantitative anchors to enhance clarity, transparency, and scalability across diverse educational contexts.

One potential direction is to consider whether certain qualitative objectives could be supplemented with behaviourally grounded indicators that retain their ethical intent while providing opportunities to improve evaluative consistency. For instance, the middle school objective “practice eco-friendly conduct” (Accomplishment level) could be accompanied by context-sensitive behavioural indicators, such as participation in small-scale sports-environment improvement activities or basic monitoring of material use and recycling practices. These anchors may be interpreted as complementing the curriculum’s value-oriented goals while introducing optional validation dimensions that could help address concerns about assessment subjectivity, particularly in pluralistic or resource-diverse settings.

Any movement toward strengthening quantitative components, however, would need to be carefully calibrated to avoid diluting the curriculum’s core emphasis on cultural identity, participatory experience, and affective internalisation. Ensuring teacher support, workload feasibility, and local adaptability may be viewed as important considerations for maintaining alignment with the curriculum’s value-rational orientation.

4.3. Theoretical Innovation: Construction of a Two-Dimensional Balance Model

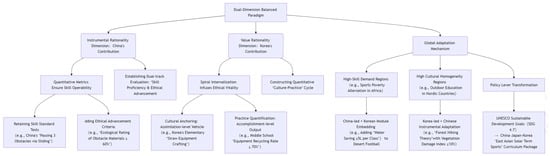

To address this ESD tension, this study synthesises the complementary strengths of both curricular pathways to propose a ‘Skill–Ethics Equilibrium’ framework [42,43,44] (Figure 2). Positioned as a heuristic model, this framework integrates the dual contributions of instrumental rationality and value rationality to outline a balanced structure for ecological PE. The instrumental rationality dimension, informed by China’s emphasis on standardised technical progression, is conceptualised as retaining the advantages of measurable skill development while creating potential entry points for ethical enrichment. For example, the existing Performance-level objective “skate through three obstacle types” could be analytically reframed as including an ecological component—such as simple evaluations of material sustainability—which may be interpreted as creating space for concurrent attention to technical proficiency and ecological considerations.

Figure 2.

The Skill–Ethics Equilibrium framework: A contextual adaptation model for ecological PE curriculum design. This heuristic model synthesises the instrumental (skill-standardisation) and value (ethical-internalisation) dimensions derived from the Chinese and Korean curricula, respectively. It illustrates how curriculum designers might prioritise or integrate these dimensions based on specific contextual conditions (e.g., high skill-demand vs. high cultural homogeneity). The diagram outlines potential adaptation pathways and practical examples, guiding towards a balanced design that aligns with broader policy and global sustainability goals (SDG 4.7).

In parallel, the value rationality dimension, derived from Korea’s emphasis on cultural and ethical internalisation, is understood as outlining pathways associated with ecological citizenship through spiral developmental mechanisms. When supported by modest, context-appropriate quantitative anchors, these value-oriented objectives could become more widely applicable across culturally diverse settings while maintaining their core emphasis on meaning, participation, and ethical intentionality. Together, the two dimensions form an analytical model of dynamic equilibrium aimed at addressing the central ESD challenge of integrating measurable competencies with value-driven action, as articulated in global sustainability education frameworks [45].

The model’s potential applicability may be further explored through the use of digital technologies. Digital learning platforms, mobile applications for tracking sustainability practices during school sports activities, and virtual simulations of ecological sports environments can be considered as providing illustrative mechanisms for linking physical skill practice with structured forms of ethical reflection [46,47]. These tools could contribute tangible data and immersive experiences that support both dimensions of the equilibrium model, potentially offering opportunities to explore connections between behavioural performance and ecological reasoning.

Ultimately, the proposed Skill–Ethics Equilibrium framework offers more than a synthesis of Sino-Korean best practices; it provides a scalable conceptual architecture for navigating the broader global tension between efficiency-driven and meaning-driven educational paradigms [48]. By rendering implicit rationalities explicit and providing an actionable framework for their integration, the model may be viewed as assisting curriculum designers and policymakers in transforming the perceived tension between “skills” and “ethics” into a productive, manageable balance. In doing so, it can be interpreted as suggesting a conceptual pathway for engaging with ESD ambitions across diverse cultural, institutional, and policy contexts.

These design principles are particularly relevant in increasingly multicultural PE classrooms, where students bring heterogeneous cultural understandings of nature, physical activity, and community responsibility. Embedding ecological reflection within skill practice may be seen as creating a shared learning structure that remains sensitive to cultural diversity while aligning with broadly shared sustainability-oriented orientations.

4.4. Study Limitations and Future Directions

First, the analysis is intentionally limited to the compulsory education phase in China and South Korea. This focus is justified because compulsory schooling represents the most standardised and policy-intensive stage of ESD implementation [49,50]. Extending comparisons to higher education or additional nations, however, would introduce substantial variability in curricular structures and learning objectives. Such expansion constitutes a distinct research agenda beyond the diagnostic scope of the present study.

Second, the analysis relies primarily on policy texts, which enables a systematic examination of intended curricula but does not capture enacted or experienced dimensions in classrooms. Future research should therefore incorporate qualitative methods—such as teacher interviews, classroom observations, and analyses of document–practice alignment—to provide a more comprehensive understanding of implementation dynamics and contextual conditions. Such qualitative, implementation-focused research is critical not only for distinguishing the “enacted” curriculum from the “intended” curriculum [51,52], but also for illuminating the institutional and pedagogical conditions under which the proposed Skill–Ethics Equilibrium framework may be interpreted, adapted, or contested in practice.

Third, future theoretical development would benefit from longitudinal and cross-contextual extensions. Longitudinal studies could explore how curricular objectives are interpreted and negotiated over time, particularly with respect to Hauenstein’s Accomplishment level and its conceptual relationship to ecological agency. Cross-cultural research across diverse educational systems could further illuminate how variations in cultural norms, governance structures, and pedagogical traditions shape different configurations of instrumental rationality and value rationality.

In addition, operationalising the proposed equilibrium framework may require the development of mixed-method evaluation tools. A promising direction is to design an “Ecological sports Portfolio” that synthesises quantitative indicators (e.g., participation records, task performance benchmarks) with qualitative assessments (e.g., reflective journals, peer appraisal of ecological orientations). Such tools may be understood as offering a more balanced basis for examining how skill development and ethical meaning-making coexist within instructional contexts.

Beyond these foundational steps, the Skill–Ethics Equilibrium framework opens several avenues for applied pedagogical research. Future studies may investigate the feasibility and contextual dynamics of context-sensitive curricular adaptations. In the Chinese context, research could examine how localised ecological elements—such as incorporating place-based environmental knowledge or designing low-resource ecological activity stations—are interpreted and negotiated within classroom and school-based practices. In the Korean context, empirical work could consider cross-disciplinary integrations that link Ecological Sports with STEM domains, such as navigation activities supported by digital mapping tools or sustainability problem-solving tasks embedded in outdoor sports modules. Developing and validating tiered ethical-assessment scales for multicultural classrooms would further support the model’s adaptability by providing culturally responsive indicators that capture nuanced forms of ethical reasoning and ecological engagement.

Together, these future directions underscore the need for sustained empirical, theoretical, and design-based research to further refine and examine the applicability of the Skill–Ethics Equilibrium framework across diverse educational settings.

5. Conclusions

5.1. Underlying Patterns of Divergence: Pathways of Instrumental and Value Rationalities

The comparative analysis suggests that the divergences observed between the Chinese and Korean ecological PE curricula point to a broader tension within ongoing debates in global Education for Sustainable Development (ESD): balancing measurable competencies with opportunities to cultivate ethical and ecological orientations. Beyond representing isolated pedagogical choices, the two systems express distinct cultural pathways shaped by instrumental rationality and value rationalities.

China’s curriculum, informed by an efficiency-oriented logic, lays out a linear “Acquisition → Adaptation → Performance” structure that emphasises system-wide skill standardisation. This design supports the equitable dissemination of foundational motor competencies and aligns with national priorities in physical fitness and educational accountability. At the same time, the analysis suggests that ecological and ethical intentions are not systematically embedded within this progression, often appearing indirectly through safety-related modules or through sections with limited instructional time. The absence of Accomplishment-level objectives (0%) limits the formalised opportunities for higher-order ecological reasoning or value enactment, resulting in a curriculum that foregrounds technical proficiency while providing more limited structural space for ecological citizenship as envisaged in ESD frameworks [42,43].

In contrast, South Korea’s curriculum can be viewed as articulating a value-oriented cultural symbiosis framework. Its “Assimilation → Adaptation → Accomplishment” spiral progression connects cultural heritage, ecological awareness, and civic participation, positioning ethical orientations as elements that may be enacted through practice. This structure appears to create clearer conceptual linkages to ecological meaning-making. However, the curriculum’s reliance on qualitative assessment and the absence of Performance-level objectives may pose challenges for ensuring transparency and consistency in more culturally diverse or resource-variable school environments.

Taken together, these findings do not pit one system against the other; rather, they illustrate how two modern educational logics—instrumental rationality and value rationality—manifest in ecological sports curricula, presenting distinctive strengths alongside identifiable constraints.

5.2. Research Contributions: Advancing a Two-Dimensional Equilibrium Model

This study contributes to ESD theory and practice through the development of the Skill–Ethics Equilibrium framework.

Theoretically, the Skill–Ethics Equilibrium framework moves beyond a simple dichotomy by illustrating how the strengths of each system can be complementary. China’s emphasis on standardised progression may be interpreted as offering mechanisms that enhance clarity and evaluability within value-oriented curricular components. At the same time, Korea’s spiral internalisation provides conceptual pathways for embedding ecological meaning within sequences of skill development. Viewed in this way, the two national approaches are reframed not as oppositional systems, but as mutually informative dimensions within a balanced educational framework that engages with the enduring ESD tension between skill proficiency and ecological citizenship.

Positioned as a heuristic framework derived from this comparative case analysis, the Skill–Ethics Equilibrium model offers a reflective lens for curriculum design and adaptation, rather than a prescriptive or universally applicable solution.

At a more applied conceptual level, the model provides a flexible analytical foundation for exploring potential curricular refinements across both systems. The findings suggest that China’s curriculum may be understood as benefiting from the selective incorporation of explicit ecological objectives at the Accomplishment level, thereby expanding structural opportunities for ethical enactment. In contrast, Korea’s curriculum may be viewed as being complemented by the inclusion of modest, context-appropriate behavioural anchors to support evaluative clarity and consistency. These illustrations are intended not as prescriptive recommendations, but as reflective examples of how instrumental and value rationalities may interact productively within curriculum design.

More broadly, the Skill–Ethics Equilibrium framework offers an adaptable conceptual lens for curriculum designers and policymakers seeking to align national educational priorities with global sustainability frameworks. As a reflective rather than prescriptive tool, the Skill–Ethics Equilibrium framework helps educational stakeholders navigate tensions between efficiency-driven and meaning-driven imperatives. Future empirical research—including classroom-based studies, mixed-method evaluation tools, and cross-cultural applications—will be important for examining how this framework is interpreted and explored in practice, and for refining its applicability across diverse educational settings. Through such sustained inquiry, the conceptual synthesis advanced in this study may contribute to ongoing international discussions surrounding ESD and UNESCO’s Sustainable Development Goal 4.7.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.-X.Y.; methodology, K.-X.Y. and S.H.; software, K.-X.Y.; validation, L.-M.T. and S.H.; formal analysis, K.-X.Y., S.H. and H.-C.J.; investigation, K.-X.Y. and L.-M.T.; data curation, K.-X.Y., L.-M.T. and S.H.; writing—original draft preparation, K.-X.Y.; writing—review and editing, K.-X.Y., L.-M.T., X.-L.Z. and H.-C.J.; visualisation, K.-X.Y.; supervision, X.-L.Z. and H.-C.J.; project administration, K.-X.Y., L.-M.T. and X.-L.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Lee, S.K.; Kim, N. Environmental education in schools of Korea: Context, development, and challenges. Environ. Educ. 2017, 26, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, J.; Trendafilova, S.; Ziakas, V. Environmental sustainability and sport management education: Bridging the gaps. In Creating and Managing a Sustainable Sporting Future; Routledge: London, UK, 2020; pp. 168–179. [Google Scholar]

- Van Rheenen, D.; Melo, R. Nature sports: Prospects for sustainability. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yekini, A. The Implementation of Climate Change Law: The Case of Benin; Proefschrift Maken: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Reimagining Our Futures Together: A New Social Contract for Education; Educational Science Press: Beijing, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Lundvall, S.; Fröberg, A. From individual to lifelong environmental processes: Reframing health in physical education with the Sustainable Development Goals. Sport. Educ. Soc. 2023, 28, 684–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucht, C.; Mess, F.; Bachner, J.; Spengler, S. Education for sustainable development in physical education: Program development by use of intervention mapping. Front. Educ. 2022, 7, 1017099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos-Pastor, M.L.; Ruiz-Montero, P.J.; Chiva-Bartoll, O.; Baena-Extremera, A.; Martínez-Muñoz, L.F. Environmental education in initial training: Effects of a physical activities and sports in the natural environment program for sustainable development. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 867899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posso Pacheco, R.J.; Cóndor Chicaiza, M.G.; Cóndor Chicaiza, J.D.R.; Núñez Sotomayor, L.F.X. Desarrollo ambiental sostenible: Un nuevo enfoque de educación física pospandemia en Ecuador. Rev. Venez. Gerenc. 2022, 27, 464–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baena-Morales, S.; Merma-Molina, G.; Ferriz-Valero, A. Integrating education for sustainable development in physical education: Fostering critical and systemic thinking. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2023, 24, 1915–1931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China. Compulsory Education Physical Education and Health Curriculum Standards (2022 Edition); Beijing Normal University Press: Beijing, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.; Wan, Y.; Cao, Y. Logical dimension and practical approach of equity in physical education classroom teaching based on embodied cognition theory. J. Shandong Inst. Phys. Educ. Sports 2025, 41, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Education of South Korea. Physical Education Curriculum; Ministry of Education: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J. Understanding and practicing ecological sports: Focusing on the application of marathon classes. Uri Cheyuk 2023, 30, 16–25. [Google Scholar]

- Son, C.-T.; Youn, H.-S. Past, present, and future of school physical education in Korea: From the perspective of curriculum revision. Jpn. J. Sport Educ. Stud. 2011, 30, 77–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, K. Exploring support plans for teachers’ understanding of the 2022 revised physical education curriculum. J. Curric. Eval. 2023, 26, 107–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.; Yi, D.; Hong, J.H. Estimating the economic value of environmental education: A case study of South Korea. Environ. Educ. Res. 2024, 30, 1748–1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, D.; Park, S. A study of measures for sustainable sport. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, M. Economy and Society: An Outline of Interpretive Sociology; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Hauenstein, A.D. A Conceptual Framework for Educational Objectives: A Holistic Approach to Traditional Taxonomies; University Press of America: Lanham, MD, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, N. The comparison of Hauenstein’s taxonomy of educational objectives to Bloom’s. Stud. Foreign Educ. 2004, 12, 10–13. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, L.; Sheng, Q. New framework for educational objectives classification: A review of Hauenstein’s taxonomy and its integration model. China Educ. Technol. 2005, 7, 21–25. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Qu, B.; Wu, X. A comparative study of primary school PE teaching in China and South Korea. Sichuan Sports Sci. 2016, 35, 126–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, J.W.; Rodrigues, R.B.; Cicek, J.S. Pair-coding as a method to support intercoder agreement in qualitative research. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE Frontiers in Education Conference (FIE), Lincoln, NE, USA, 13–16 October 2021; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bengtsson, M. How to plan and perform a qualitative study using content analysis. NursingPlus Open 2016, 2, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eelderink, M.; Vervoort, J.M.; Van Laerhoven, F. Using participatory action research to operationalise critical systems thinking in social-ecological systems. Ecol. Soc. 2020, 25, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, W.; Liu, X.; Tao, X. Cross-level thematic design logic of interdisciplinary thematic learning in physical education and health. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Sport Science, Guangzhou, China, 26–27 April 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, R.; Huang, J.; Chen, H.; Xue, P.; Guo, M.; Liu, X. Current situation of health education in physical education and health curriculum in primary and secondary schools in Beijing. Health Educ. Inst. Beijing Cent. Dis. Control Prev. 2025, 41, 252–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- State Council of the People’s Republic of China. Outline for Building a Leading Sports Nation. 2019. Available online: https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/content/2019-09/02/content_5426485.htm (accessed on 10 May 2019).

- Central Committee of the Communist Party of China; State Council of the People’s Republic of China. “Healthy China 2030” Planning Outline. 2016. Available online: https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/2016-10/25/content_5124174.htm (accessed on 13 May 2019).

- Wang, X. Curriculum content structure and characteristics of compulsory education curriculum standards for physical education and health (2022 edition). J. Cap. Univ. Phys. Educ. Sports 2022, 34, 241–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Z.; Meng, H.; Sun, M.; Tian, H.; Guo, Z.; Liu, B. Thinking principles and practical paths of implementing key competency cultivation in physical education and health curriculum under the background of new curriculum standards. J. Cap. Univ. Phys. Educ. Sports 2022, 34, 253–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, X.; Liang, H. On the Ecological Attainment of Citizens and Its Cultivation. J. China Exec. Leadersh. Acad. Jinggangshan 2016, 9, 60–67. [Google Scholar]

- Mao, Z.; Yang, D.; Li, H. “Health China 2030 Program” and school PE reform strategies (2): For reaching excellence rate of national student physical health standard by over 25%. J. Wuhan Inst. Phys. Educ. 2018, 54, 75–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krettenauer, T.; Stichter, M. Moral identity and the acquisition of virtue: A self-regulation view. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2023, 27, 396–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Education for Sustainable Development: Towards Achieving the SDGs (ESD for 2030); UNESCO: Paris, France, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, J.; Choi, D.; Lee, M. The Environmental Education of Primary School Applying Ancestral Eco-wisdom in Traditional Culture. Environ. Sci. Educ. 2007, 20, 73–89. [Google Scholar]

- Government of the Republic of Korea. The Korean New Deal: National Strategy for a Great Transformation; Government of Korea: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Ecology and Environment of South Korea. Carbon Neutrality Strategy 2050; Ministry of Ecology and Environment: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Government of the Republic of Korea. Framework Act on Carbon Neutrality and Green Growth for Coping with Climate Crisis; Government of Korea: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, D.; Wang, Y.; Wu, S. Research on the value implications and practical pathways of ecological civilisation education in higher education institutions under the dual carbon goals. J. Hebei Polytech. Univ. Soc. Sci. Ed. 2025, 25, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D. Causes and elimination paths of ecological imbalance in physical education teaching. Teach. Adm. 2014, 30, 113–115. [Google Scholar]

- Da Costa, L.A.; McNamee, M.; Lacerda, T. Re-envisioning the ethical potential of physical education. Recerca 2016, 18, 29–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldock, R.; Pill, S. What are physical education teachers being told about how to teach sport? An exploratory analysis of sport teaching in physical education. Learn. Communities Int. J. Learn. Soc. Contexts 2017, 21, 108–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Global Education Monitoring Report 2016: Education for People and Planet; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Lynch, J.; Thomas, H. Digital technology in outdoor and environmental education: Affects, assemblages and curriculum-making. Aust. J. Environ. Educ. 2024, 40, 288–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuang, T.-Y.; Tsai, S.-H.; Lu, Y.-L. Technology-enhanced digital game-based learning for environmental literacy: Catalysing attitude change in learners. Front. Educ. 2025, 10, 1629670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popa, S. Towards 2030 and beyond: Challenges, constants, and the need to transform education. Prospects 2024, 54, 507–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yao, J.; Zhou, S. Is the standardisation of compulsory education school helpful to improve students’ performance? An empirical analysis based on monitoring data in province A. Best Evid. Chin. Educ. 2020, 5, 591–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, S. Analysis on Chinese compulsory education classroom structure from the perspective of ESD strategy. In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Humanities and Social Science Research (ICHSSR 2021), Qingdao, China, 23–25 April 2021; Atlantis Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 23–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karakus, G. A literary review on curriculum implementation problems. Shanlax Int. J. Educ. 2021, 9, 201–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falkner, K.; Sentance, S.; Vivian, R.; Barksdale, S.; Busuttil, L.; Cole, E.; Quille, K. An international comparison of K–12 computer science education intended and enacted curricula. In Proceedings of the 19th Koli Calling International Conference on Computing Education Research, Lieksa, Finland, 21–24 November 2019; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.