Abstract

This paper presents an analysis of energy savings and sustainability measures to improve the environmental performance of glass wool fiberizing, the latter being the most energy intensive production step in manufacturing glass wool thermal insulation, involving conversion of hot molten glass into fibers. The first part evaluates two refractory designs—business as usual (BAU) and modified (MOD), over four trials. BAU refractory has higher density whereas MOD is an innovative lightweight design, with lower density and improved thermal conductivity. The key operational parameters analyzed include energy demand and CO2 emissions in the fiberizing stage, along with burner pressure, temperature and fiber diameter. The results show that MOD has better thermal performance, leading to an average energy demand reduction potential of up to 10%. The second part focuses on promoting a circular economy for the end-of-life refractory, underpinned by the potential for recovery and reuse of spent refractory materials. Based on a total refractory mass of 1.2 tons for the six burners, the end-of-life refractory material recovery is estimated as 0.78 ton (65% of the aggregate). Balancing the recovery costs with the acquired value of the recovered aggregates, results demonstrate significant material and environmental cost avoidance on a 3-year refractory relining cycle.

1. Introduction

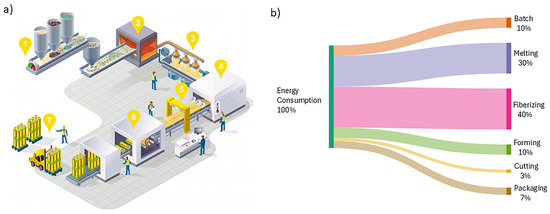

Glass wool thermal insulation (GWTI), commonly known as glass wool or fiberglass, is increasingly applied in modern construction for reducing heating/cooling energy demands. Its diverse applicability in the construction industry has led to efficient and more sustainable construction practices. While alternative materials such as cellulose from recycled paper, polyisocyanurate (PIR) and hemp-based insulation may offer lower thermal conductivity, glass wool remains one of the few materials proven at a large industrial scale, owing to its balance of thermal performance, mechanical durability and cost efficiency [1]. However, its manufacturing involves an energy intensive process. GWTI is typically composed of molten glass mixed with raw materials such as sand, dolomite, borax, etc. Its industrial production involves the following sequential steps: 1. Batching, 2. Melting, 3. Fiberizing, 4. Curing, 5. Cutting, 6. Packaging (Figure 1a) [2]. As a first step, all the raw materials, including glass, are mixed together in batching, and then melted in a furnace. The molten mixture is then passed through a fiberizing machine that converts the molten mix into fibers. The fibers are stuck together using a binder mixture and passed into the forming chamber, followed by cutting and finally packaging for supply. The energy consumption trends in the typical GWTI manufacturing steps are as follows: Fiberizing > Melting > Batch > Curing > Packaging > Cutting (Figure 1b).

Figure 1.

(a) Production stages of glass wool thermal insulation manufacturing: 1. Batching, 2. Melting, 3. Fiberizing, 4. Curing, 5. Cutting, 6. Packaging [2]; (b) Sankey Diagram showing the energy consumption percentages of a typical glass wool production process. Source: Drafted by authors.

The greatest share of energy consumption in the fiberizing step is attributed to the operation of the fiberizing machine that converts hot glass into fibers by a centrifugal force generated by a fast-moving piece of equipment called the spinner. Significant energy is required to maintain the temperature of the fiberizing machine during the fiberizing process, which leads to a higher air-to-gas ratio and hence more carbon dioxide emissions. In addition, the external burner consumes a large amount of fuel (commonly natural gas and air) to maintain the temperature of the spinner. The external burner is cast with thermal cement known as ‘refractory’ to trap the heat inside the burner and to prevent any heat losses. The refractory has excellent thermal properties with which to trap the heat and reduce the consumption of gas and air energy [1]. Theoretically, this enables the maintenance of a higher burner temperature at less gas and air flow, resulting in savings for electricity and gas consumption, thereby reducing overall CO2 emissions.

Fiberizing is one of the most important steps in GWTI manufacturing. The hot glass pours into the fiberizing machine where the fast-moving spinner equipment creates fibers through centrifugal force (CF). The CF drags the hot glass into thin shiny fibers, which then pass through binder liquid mixed with water to create a mat with excellent insulating properties. There is an external burner that runs on the combustion of the air and gas mixture to help maintain the temperature of the spinner while glass is spun into fibers through CF. This production stage is crucial to ensure the fibers have the standard mechanical properties and thermal conductivity. It is also an important stage for optimizing the energy efficiency of the overall insulation [2].

To avoid substantial heat loss through the combustion-system linings during fiberizing, refractory design parameters are key in reducing heat losses and improving energy efficiency in high-temperature industries. These include thermal conductivity and aspects of the microstructure, such as porosity level, pore size distribution and phase assemblage [3]. The refractory is composed of a heat-resistant cement binder used in high temperature applications such as the furnace, forehearth and other exposed industrial equipment. The chemistry behind the refractory helps to maintain structural integrity and to provide successful thermal insulation under extreme heat conditions. The microstructure of the refractory provides lower thermal conductivity, indicating that heat transfer is minimum through the material, thereby offering excellent insulation. The refractory material absorbs the stress caused by rapid changes without cracking. This durability property plays a crucial role in high temperature insulation in glass wool manufacturing. Therefore, refractory cement has high temperature resistance, thermal shock resistance and lower thermal conductivity [4]. Modifications at the fiberizing stage can potentially lead to energy savings in terms of air and gas.

Recent refractory research has increasingly focused on microstructure engineering, particularly the control of porosity and phase development, in order to achieve improved insulation (lower heat transfer) while retaining sufficient integrity for industrial operations [5]. These insulation gains, however, typically involve a trade-off with mechanical strength and durability, meaning that lightweight insulating castable is generally more suitable when reducing heat loss is prioritized over high mechanical robustness, such as at the fiberizing stage in GWTI production [6]. It is important to understand the basic chemistry behind refractory cement. This consists of compounds which are high-temperature resistant, such as Calcium Aluminate Cement (CAC), combined with refractory aggerates and other additives that enhance the thermal properties of the material [7]. CAC is one of the main binders in refractory cement. It has a dense matrix attained through a series of high-temperature hydration processes [8]. The refractory aggregates are high-purity oxide materials such as Alumina (Al2O3), Silica (SiO2), Zirconia (ZrO2) and Magnesia (MgO). These aggregates provide stability to the structure and increase the high-temperature performance of the material when they are combined with CAC. The aggregates also assist in improving resistance to thermal shock and in controlling thermal expansion to avoid cracks in the cement. Additives such as spinels, borates and refractory clays are included in the cement to enhance the thermal properties. These additives tailor the thermal insulation properties by changing the phase composition and by reducing thermal conductivity [9].

The use of lightweight insulating castable and graded lining concepts are increasingly applied to improve insulation performance, where an insulating layer is designed specifically to reduce thermal conductivity and minimize heat loss through the refractory lining [10]. From a materials perspective, insulation performance can be enhanced by incorporating porous aggregates (e.g., hollow alumina-based constituents), and by adopting formulation approaches that promote stable pore networks at elevated temperatures, both of which can significantly reduce effective thermal conductivity [11].

This study presents a comparative analysis of glass wool fiberizing using alternative refractory designs, alongside an exploration of the potential for end-of-life refractory reuse. The first part summarizes the results from the four trials conducted with a fiberizing machine cast with a new type of refractory (henceforth called MOD) compared with an old refractory (henceforth called BAU). It identifies the performance improvements between the BAU and the MOD refractory designs in terms of fiberizing data, including burner pressure, burner temperature, gas flow, air flow and fiber diameter. The second part focuses on promoting a circular economy for the end-of-life refractory. This is underpinned by evaluation of sustainability measures to recover refractory material beyond its 3-year operational life through recycling, in order to improve its reuse and reduce its environmental impact.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Refractory Performance Analysis

Quantitative analysis was conducted to assess the performance improvements (if any) between the old (business-as-usual, BAU) and the modified (MOD) refractories. The first step involved casting the burner with the MOD refractory. This was done in order to assemble the refractory with the rest of the fiberizing machine. There are a total of six fiberizing machines at the manufacturing plant. The BAU refractory has higher density, has better durability and is used in applications that are directly exposed to heat. It also has high thermal conductivity and can accommodate temperature up to 1500 °C. On the other hand, the MOD refractory is lightweight, with lower density and lower thermal conductivity. It is used in applications to prevent heat loss and achieve higher energy efficiency. However, it has lower mechanical strength, making it less durable [12]. Based on the product data sheet provided by GWTI manufacturer Saint-Gobain (ISOVER), the MOD refractory has density typically ranging between 1150 and 1350 kg/m3. In contrast, the BAU refractory has density typically exceeding 2200 kg/m3, hence classifying it as a dense castable. This large difference in density is directly linked to their respective thermal performances. The MOD and the BAU refractories, respectively, have thermal conductivities ranging between 0.30 and 0.32 Wm−1·K−1 and 1.2–1.8 Wm−1·K−1, with MOD clearly having better thermal efficiency. This is owing to its lower density composition, attributed to material with greater porosity, resulting in reduced thermal conductivity and significantly improved insulation efficiency. This explains why machines lined with the MOD refractory retained higher operating temperatures under identical process conditions, as observed in the trial results in this study (See Section 3.1).

The machine monitoring software collects operational data on gas, air, temperature, pressure and fiber diameter as numeric values, 6 times a day, through sensors in order to ensure production parameters are meeting the required specifications. These data collected from the MOD refractory machine were compared with the data collected from the BAU machine following one full month of operation. The multiple numeric data collected from both MOD and BAU refractory machines were analyzed using Excel tools, including the energy savings calculation taking into consideration the computed accurate machine efficiency (See Section 2.2).

2.2. Evaluation of Machine Efficiency

The downtime (DT) of the fiberizing machine was considered to represent its operational inefficiency. Each machine’s downtime was recorded, and the downtime data were exported into an Excel workbook to calculate its inefficiency. This was followed by a method of calculating machine efficiency, which was applied to the MOD refractory machine while it was in production.

The trial duration, number of data points, burner pressure, temperature, gas flow, air flow and fiber diameter remained unchanged for all the four trial data sets. The following units were used throughout in the evaluations throughout: energy conversion from Nm3/h to kWh was applied for consistency to estimate the fuel consumption (gas and air), electricity kWh and CO2 tons. The trial period days were converted into minutes for efficiency calculations. The machine efficiency was estimated using Equation (1). This new extended methodology would give savings only in that particular trial period with a real runtime of the machine.

2.3. Data Collection and Analysis

All raw data obtained for both BAU and MOD refractory machines had identical sampling time with 119 data points. The following five parameters were monitored for comparative analysis:

- Pressure (mmWC): represents the burner pressure that pushes the fibers downwards, expressed in millimeters of water column (1 mm WC= 0.0098 mPa).

- Temperature (°C): represents the burner and fiberizing machine temperature.

- Gas Flow (Nm3h−1): represents fuel consumption by the burner in terms of gas.

- Air Flow (Nm3h−1): represents compressed air supplied at 3 bar for combustion in the fiberizing machine.

- Fiber Diameter: represents the output glass fiber diameter (range 14.5–15.5 µm).

Manual Lip measurements were taken regularly to ensure that pressure and temperature readings were correct. Gas Flow and Air Flow instrument readings in Nm3h−1 were converted into kWh. Table 1 lists the gas-to-energy conversion factors, unit prices for gas and air (electricity), and the tariff values used in the efficiency analysis.

Table 1.

Summary of conversion factors, tariff rates and calculation methods used in efficiency analysis.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Performance Monitoring Trends

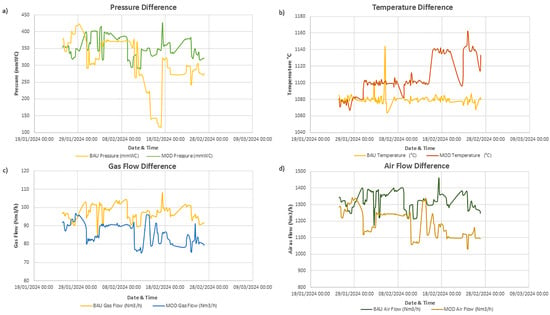

The performance of the MOD and BAU refractory machines were assessed over the trial production period in terms of the monitored parameters. The ideal pressure range to keep the product within specifications is between 300 and 400 mmWC. Figure 2a shows that both MOD and BAU refractories performed within this acceptable pressure range. However, the MOD refractory has more stable pressure control, offering a slight improvement in operational conditions with more data points within the specified pressure range compared to the BAU refractory pressure. The spikes or dips in the graph show anomalies, which are generally attributed to the furnace load or sensor issues.

Figure 2.

Time-series plots for the parameters monitored for the two refractory designs. (a) Pressure difference; (b) Temperature difference; (c) Gas flow difference; (d) Air flow difference. Source: Drafted by authors.

Figure 2b shows that the MOD refractory had better insulation and consistent heat management. In addition, Table 1 shows that MOD and BAU refractory machines recorded average temperature of 1107.22 °C and 1080.45 °C, respectively. The higher temperature observed in the MOD refractory trial (+26.77 °C) is attributed to its insulation property owing to lower density composition. Unlike the BAU refractory, which is a dense castable with higher thermal conductivity, the MOD material incorporates lightweight aggregates and a modified alumina–silica binder system that increases porosity and reduces conductive heat loss. This behavior is consistent with established findings that aggregate selection, binder chemistry and additives directly influence thermal conductivity (see Section 2.1) and heat retention in alumina-based refractory castable [4,5,6]. This enabled better thermal conditions in MOD machine for fiberizing of the molten glass.

As shown in Figure 2c, the BAU refractory machine consumed an average gas flow between 90 and 105 Nm3/h; meanwhile, the MOD refractory machine consistently showed lower consumption of gas flow and stayed within in the range 75–90 Nm3/h. This indicates that the MOD refractory has lower energy demand and has better heat retention compared to the BAU refractory machine. Both refractories show a stable operation, but the MOD refractory achieved better thermal conditions as it achieved a higher temperature with less gas consumption, showing improvement in thermal efficiency and optimized process conditions.

Figure 2d clearly shows that the MOD refractory machine requires less air flow to maintain fiberizing production conditions. The air flow for the BAU refractory machine fluctuate between 1200 and 1400 Nm3/h; meanwhile, the airflow range was significantly low for the MOD refractory machine, ranging between 1000 and 1250 Nm3/h. This was consistent with expectations, as the MOD refractory machine consumes lower gas energy and maintains better heat management, and therefore does not require higher air flow for combustion.

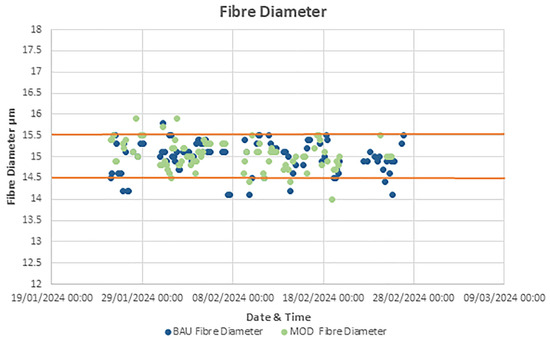

Figure 3 shows the glass fiber diameter measurements from the two fiberizing units over the sampling period in order to ascertain any compromise in fiber quality. Specifically, it has taken into account the MOD refractory trial to monitor any variations in the quality of fiber while attaining efficiency measures. The ideal range for fiber diameter for optimum fiber quality is considered as between 14.5 and 15.5 µm, and both BAU and MOD refractory machines were noted to produce fibers within this acceptable range.

Figure 3.

Glass fiber diameter measurements from the two fiberizing units over the sampling period. Source: Drafted by authors.

This indicates that the MOD refractory machine, despite having lean (and efficient) operating conditions in terms of temperature, gas flow and air flow, does not compromise on quality, and is still capable of yielding high quality glass fibers within the acceptable fiber diameter range.

3.2. Efficiency Analysis

Emission Factor: The CO2 reduction of 39 tons or 39,000 kg refers specifically to operational emissions avoided during the four refractory trials. A total measured gas reduction of 195,156 kWh was recorded over the four trials (75,859 + 49,552 + 51,424 + 18,321 kWh) (Table 2). Therefore, the emission factor is estimated using Equation (2).

Table 2.

Energy performance comparison between BAU and MOD refractories across four trials.

The emission factor methodology follows the GHG Conversion Factors for Company Reporting, issued by the UK Government Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA), 2025, which provides the standard natural-gas emission factor of 0.183 kg CO2/kWh [13].

Table 3 lists the recorded BAU and MOD refractory parameters The average pressure for the recorded MOD is 327.22 mmWC, which is lower than that of the BAU refractory (354.24 mm WC). This indicates reduced system resistance and improved flow characteristics. The average temperature recorded for the BAU and the MOD were, respectively, 1080.45 °C and 1107.22 °C. The higher average temperature for MOD represents better insulation conditions, which in turn is beneficial for optimum fiberizing conditions. The average gas flow reduction in MOD to 86.31 Nm3h−1 from 96.97 Nm3h−1 in BAU, and the lower air flow for MOD of 1191.09 Nm3h−1 compared to BAU 1321.35 Nm3h−1, indicates efficient combustion conditions and potential for energy savings. The average fiber diameter for MOD is recorded as 15.04 µm, which is within the acceptable glass fiber diameter range of 14.5–15.5 µm, indicating that the energy efficiency attained does not compromise the quality of the glass fiber.

Table 3.

BAU and MOD refractory parameters (30-day average between 25 January 2024 and 26 February 2024).

Only the operational data collected for samples with a fiber diameter within the acceptable threshold of 14.5–15.5 µm were considered for efficiency analysis. Table 4 shows energy cost savings over the four trials between the BAU and MOD in terms of reduced fuel costs (gas and air) and CO2 emissions. The first trial achieved the highest saving of £7605 over the 31-day trial period, with the highest machine efficiency of 90.73%. The second trial achieved £5058 savings at a machine efficiency of 80.91%. This is acceptable given that the second trial was only over a 20-day period. However, the machine efficiency dropped significantly in the third trial period, attributed mainly to the excessive downtime. Noteworthily, the fourth trial had the lowest energy savings among all the trials, despite a machine efficiency of 72%, attributed mainly to poor glass quality. Over the total of 111 trial days, the MOD refractory machine saved £19,710: £15,593 on gas consumption, £1, on air consumption and £2935 on CO2 reductions, leading to an estimated reduction of 39 tons of CO2 emissions compared to the BAU in Table 4. The MOD refractory design therefore demonstrates promising results towards cleaner production practices in the glass wool manufacturing industry.

Table 4.

Energy cost saving data with machine efficiency for the four trials.

3.3. Recovery Potential of Refractory External Burner

This section explores circular economy pathways with which to recover the spent (used) external burner refractory. Typical external burner refractory has an average lifetime of 3 years. It becomes thermally insufficient after 3 years and cannot trap heat inside the burner, thereby leading to operational inefficiency. The heat losses largely occur due to cracking of the refractory inside the burner. The cracks could also take place before the 3-year period due to heat stress. Nevertheless, as a standard practice, the refractory needs to be replaced at the end of its operating life every 3 years. The chunks of refractory are removed from the external burner as a solid concrete and this opens an opportunity to extend the refractory’s lifetime by recycling those chunks of refractory.

As a first step, various methods were considered of extending the operating life of the external burner refractory used in the fiberizing machine in the glass wool insulation industry, and the current practice of recycling spent (used) refractory material was reviewed (Table 5). Spent refractory linings represent a significant secondary material stream in high-temperature industries, but feasibility and the benefits of recovery depend on the waste chemistry, degree of contamination and the end-use pathway. Based on a life-cycle assessment of refractory waste management in an operating steelworks, the end-of-life applications typically comprise a mixed portfolio, such as direct reuse of selected refractory brick types, external recycling for compatible streams, etc. The net environmental benefit is also strongly influenced by adoption of realistic system boundaries and substitution assumptions, such as the displacement of refractory raw material [14]. Figure 4 depicts the prominent recycling pathways for spent refractory in glass wool manufacturing.

Table 5.

Available external burner refractory recycling methods.

Figure 4.

Independent recycling pathways for spent refractory in glass wool manufacturing [15,16,17,18].

Importantly, recovery levels reported in the literature demonstrate that meaningful diversion from landfill can be achieved when the spent refractory stream is appropriately characterized and matched to a suitable outlet. Smith et al. reported that up to 50% of the spent refractories generated annually in Missouri, USA had strong recycling potential, specifically identifying alumino-silicate refractories (45% Al2O3) as effective raw-material substitutes in Portland cement manufacture, and Doloma refractories as having reuse potential, such as in soil conditioning, provided that the material is segregated and processed appropriately [19]. This evidence supports presenting recovery as a range constrained by composition and handling and this aligns with the conservative reclaim assumptions adopted in this study.

- Refractory cost estimation: Procurement costs are charged on a dry mass basis. Procurement records (provided by Saint-Gobain, ISOVER) indicate a unit price of £5260 per ton on a dry mass basis for the MOD refractory used in the trials. The burner casting procedure requires 100 kg dry mix (4 × 25 kg bags of dry mix per burner, equivalent to 0.1 ton). Considering six burners, this would equate to a mass of 0.6 ton and the corresponding cost would be £3156 on a dry weight basis. However, the material specification involved 48–55% added water, resulting in a cast mass after mixing of approximately 200 kg, equivalent to 0.2 ton. This would lead to a total mass of 1.2 tons for the six burners and a corresponding total cost of £6312. At the end of life, the full installed mass of 1.2 tons is physically available for recycling. Accordingly, all material recovery and circular-economy calculations in this study are expressed on a post-mix (installed-mass equivalent) basis.

The chemical binder dissolution process reclaims the refractory mass in the range of 600–720 kg from the 1.2 ton total mass. The patch and repair method does not recover any mass, as it simply fills the cracks in the refractory as a maintenance procedure and extends the life of the material up to a maximum 1 year.

The mechanical crushing and screening method alone can recover up to approximately 65% of the spent refractory original mass. This leads to a net reclaimed mass through mechanical procedure as 65% of 1.2 tons = 0.78 ton per 3-year cycle, if all machines are cast at the same time.

This would lead to an estimated 65% of the total spent refractory mass eligible for recovery and reuse, avoiding landfill disposal. The retrieved material can be used in new burner linings or sold to low temperature application industries to promote a circular economy, also potentially reducing the demand for virgin refractory materials.

- Environmental and Economic assessment: The following assumptions were made regarding reusability of the spent refractory:

- i.

- Internal reuse: The recovered refractory material can be blended with fresh alumina to cast new burner linings. Industry practice suggests a safe recycling content of up to 30%, ensuring that the mechanical and thermal performance of the castable is maintained [15].

- ii.

- Selling to cement companies: Selling the aggregate to other cement industries to reduce the operational cost and support a broader circular economy.

- iii.

- Reuse in the construction sector: The reclaimed refractory can be used as insulating castable formulations in the construction sector, such as ducts and roofs, promoting environmental sustainability [20].

Based on today’s refractory price (£5260/ton), when recycling 0.78 ton of the spent refractory material at an assumed recycling cost of £59/ton with 3% inflationary margins, the present value of this saving is estimated as £4055. This indicates that, even under conservative financial modelling, the recycling pathway delivers a strong net benefit relative to virgin procurement.

- CO2 Emissions Reduction: As these recycling methods are avoiding the production of 0.78 ton of new castable refractory material that would otherwise require high temperature firing of new castable material, it would effectively be saving 1.2 tons of CO2 emissions generated per ton of produced castable material [20]. Therefore, total (1.2 × 0.78 =) 0.93 ton of CO2 emissions can be reduced per 3-year campaign.

The final fate distribution of spent refractories varies across sectors and sites, such as in internal reuse, recycling/downcycling or landfill, meaning that recovery rates should be framed as scenario-dependent and reported with clear assumptions regarding segregation, quality control and the intended end-use market [21]. From a sustainability perspective, life-cycle comparisons of refractory product systems also indicate that upstream production stages (raw materials and processing) can contribute materially to overall impacts, highlighting that credible recovery pathways can deliver an environmental benefit and reduction in refractory waste [22]. In practical terms, one scalable outlet for suitable processed fractions is their conversion into construction-grade granulates using appropriate binders, which provides a feasible route for secondary applications where refractory-grade specifications are not required [23]. However, these measures come with some practical challenges and their solution need to be explored further, such as with reference to contamination in recovered refractory due to binder remains. Therefore, quality assurance and testing are essential to separate healthy refractory aggregate that can be reused.

Integration of innovative digital twin modelling with real-time temperature and pressure data can help to study the health of the refractory inside the burner without causing any maintenance downtime. Adopting these measures would enable the glass wool fiberizing industry to reduce its ecological footprint, and at the same time secure financial returns by aligning advanced technology using circular economy principles [24].

4. Conclusions

This study presented a comparison between two refractory designs for glass wool fiberizing (business as usual, BAU and modified, MOD) in terms of fiberizing data, including burner pressure, burner temperature, gas flow, air flow and fiber diameter. Based on the four trials conducted, the MOD refractory is found to significantly reduce fuel consumption (air and gas) at an average efficiency of 74% while maintaining the burner temperature and quality of the product, saving £19,710 over 111 days of production. This result in an approximate overall operational CO2 emissions reduction of 39 tons. The MOD refractory design therefore demonstrates promising results towards cleaner production practices in the glass wool manufacturing industry. The study also evaluated prospects for a circular economy in the end-of-life recovery and reuse potential of the refractory after 3 years of its useful life, when it needs replacing owing to cracking and poor thermal efficiency. Based on an estimated 1.2 tons of refractory material on a post-mix (installed-mass equivalent) basis, recovery through mechanical crushing and screening is expected to yield up to 0.78 ton (65% of the aggregate). At an assumed recycling cost of £59/ton with 3% inflationary margins, this would approximate to a material cost savings of £4055 on a 3-year refractory relining cycle.

Further research is warranted on the potential usage of the recovered aggregate, supporting innovative applications such as burner lining and other high temperature applications, including development of new furnaces. An operational framework is required for quality assurance and testing to separate healthy refractory aggregates that can be reused. This will be specifically relevant for minimizing development of any contamination in recovered refractory due to binder remains.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.A. and A.T.; methodology, J.A. and B.F.; validation, J.A.; formal analysis, J.A. and B.F.; resources, B.F.; data curation, J.A. and B.F.; writing—original draft preparation, J.A.; writing—review and editing, A.T. and B.F.; supervision, A.T. and B.F.; project administration, B.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

J.A. would like to acknowledge the support from the St. Gobain UK (ISOVER) plant in providing access to the performance data for the fiberizing machines over the study period, which have been applied in this evaluation.

Conflicts of Interest

The author Baptiste Forgerit (B.F.) is employed by St. Gobain (ISOVER). The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Klemczak, B.; Kucharczyk-Brus, B.; Sulimowska, A.; Radziewicz-Winnicki, R. Historical evolution and current developments in building thermal insulation materials—A review. Energies 2024, 17, 5535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobain, S. Glass Wool. 2024. Available online: https://www.isover-technical-insulation.com/glass-wool (accessed on 6 June 2025).

- Vivaldini, D.O.; Mourão, A.A.C.; Salvini, V.R.; Pandolfelli, V.C. Review: Fundamentals and Materials for the Microstructure Design of High Performance Refractory Thermal Insulating. Cerâmica 2014, 60, 297–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayoumi, I.M.I.; Ewais, E.M.M.; El-Amir, A.A.M. Rheology of Refractory Concrete. Boletín de la Sociedad Española de Cerámica y Vidrio 2022, 61, 453–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitiello, D.; Nait-Ali, B.; Tessier-Doyen, N.; Tonnesen, T.; Laím, L.; Rebouillat, L.; Smith, D.S. Thermal Conductivity of Insulating Refractory Materials: Comparison of Steady-State and Transient Measurement Methods. Open Ceram. 2021, 6, 100118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemaleu, J.G.D.; Savemane, A.A.; Tome, M.; Mboussa, J.; Fabbri, L.; Tchamba, C.M.; Nzengwa, R.; Russias, J. Low-Temperature High-Strength Lightweight Refractory Matrices with a Reduced Environmental Footprint. Ceram. Int. 2023, 49, 27654–27661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Wang, X.; Li, Y.; Mu, Y.; Jia, Q.; Wang, G.; Chen, L. Evolution in properties of high-alumina castables containing basic zinc carbonate. Ceram. Int. 2021, 47, 19019–19025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giovannelli Maizo, I.D.; Luz, A.P.; Pagliosa, C.; Pandolfelli, V.C. Boron sources as sintering additives for alumina-based refractory castables. Ceram. Int. 2017, 43, 10207–10216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luz, A.P.; Lopes, S.J.S.; Gomes, D.T.; Pandolfelli, V.C. High-alumina refractory castables bonded with novel alumina–silica-based powdered binders. Ceram. Int. 2018, 44, 9159–9167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salomão, R.; Arruda, C.C.; Pandolfelli, V.C.; Fernandes, L. Designing High-Temperature Thermal Insulators Based on Densification-Resistant In Situ Porous Spinel. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2021, 41, 2923–2937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, Y.; Jian, Y.; Yin, H.; Tang, Y.; Yuan, H.; Liu, Y. The Influence of Alumina Bubbles on the Properties of Lightweight Corundum–Spinel Refractory. Materials 2023, 16, 5908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhatia, A. Overview of Refractories: Dense versus Insulating Refractory Castables—Processing, Properties, and Applications; CED Engineering Technical Report; Continuing Education and Development, Inc.: Woodcliff Lake, NJ, USA, 2019; Available online: https://www.cedengineering.com/userfiles/Overview%20of%20Refractories-R1.pdf (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- Department for Environment; Food & Rural Affairs (DEFRA). UK Government GHG Conversion Factors for Company Reporting. 2025. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/government-conversion-factors-for-company-reporting (accessed on 7 December 2025).

- Muñoz, I.; Soto, A.; Maza, D.; Bayón, F. Life cycle assessment of refractory waste management in a Spanish steel works. Waste Manag. 2020, 111, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spyridakos, A.; Alexakis, D.E.; Vryzidis, I.; Tsotsolas, N.; Varelidis, G.; Kagiaras, E. Waste Classification of Spent Refractory Materials to Achieve Sustainable Development Goals Exploiting Multiple Criteria Decision Aiding Approach. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 3016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colla, V.; Matino, I.; Rinaldi, M.; Baragiola, S.; Strohmeyer, M.; Ibañez, M.; Machado, J. Future Research and Developments on Reuse and Recycling of Refractories in the Steel Industry. Metals 2023, 13, 676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, H.; Zang, Y.; Li, H.; Xiong, S. Study of Spent Refractory Waste Recycling from Metal Industries. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 1999, 28, 239–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horckmans, L.; Nielsen, P.; Dierckx, P.; Ducastel, A. Recycling of Refractory Bricks Used in Basic Steelmaking: A Review. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 140, 297–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.D.; Fang, H.; Peaslee, K.D. Characterization and Recycling of Spent Refractory Wastes from Metal Manufacturers in Missouri. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 1999, 25, 151–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badioli, S.; Jubayed, M.; Dargaud, M.; Siebring, R.; Léonard, A. Environmental performance of refractories: A state-of-the-art review on current methodological practices and future directions. Environ. Sustain. Indic. 2025, 27, 100868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feucht, F.; Moderegger, R.; Neuhold, S.; Sedlazeck, K.P. Analysing material flows and final fate distribution of spent refractories from steel casting ladles and cement rotary kilns in Europe. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2025, 215, 108158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boenzi, F.; Ordieres-Meré, J.; Iavagnilio, R. Life Cycle Assessment Comparison of Two Refractory Brick Product Systems for Ladle Lining in Secondary Steelmaking. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seco, A.; del Castillo, J.M.; Perlot, C.; Marcelino, S.; Espuelas, S. Recycled granulates manufacturing from spent refractory wastes and magnesium based binder. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 365, 130087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grieves, M.; Vickers, J. Digital Twin: Mitigating Unpredictable, Undesirable Emergent Behavior in Complex Systems. In Transdisciplinary Perspectives on Complex Systems; Kahlen, F.-J., Flumerfelt, S., Alves, A., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 85–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.