1. Introduction

As a major source of global environmental pollution, clothing ranks second only to petrochemicals [

1]. Clothing production consumes large amounts of water resources [

2], while overproduction further exacerbates marine, air, and soil pollution [

3]. The sustainable challenges are more severe for the Chinese fashion industry [

4]. According to official data, China has become the top producer and consumer of clothing in the world [

5]. In 2024, clothing production exceeded 70 billion pieces, with domestic sales reaching 4.5 trillion yuan, accounting for approximately 40% of global sales [

5]. Despite the huge potential of the domestic market, lots of clothes are soon discarded once their brief popularity fades [

6]. In response, the government has developed policies to promote the green transformation of industries, providing financial incentives for enterprises to adopt environmentally friendly production processes [

7]. Meanwhile, more and more scholars have turned their attention to this field. Although consumers recognize the environmental value of the products, a gap remains between their positive attitudes and purchase behaviors [

8].

Previous research has indicated that consumers’ purchase intention of sustainable fashion products is affected by perceived value and product attributes [

8], while the connection with local culture can further strengthen perceived value [

9]. Compared to other countries, Chinese consumers exhibit notably higher scores on the dimension of “long-term orientation” [

10]. In a culture that emphasizes traditional values and intergenerational continuity [

11], supporting sustainable products to foster cultural development has become a key driver of Chinese consumers’ purchase behavior. In addition, clothing is a direct expression of consumers’ cultural and aesthetic preferences [

12]. Therefore, design strategies based on traditional cultural elements may improve consumers’ evaluation of sustainable fashion products. However, there remains a lack of systematic empirical research on which traditional cultural elements can effectively influence Chinese consumers’ purchase intentions and their mechanisms of action.

Hall described culture as an iceberg that contains visible aspects (e.g., artifacts and graphics), as well as invisible aspects (e.g., values, spirit, and techniques) [

13]. This study posits that consumers can also perceive two aspects of traditional culture in sustainable fashion products: traditional cultural symbols and traditional craftsmanship. This integration provides a comprehensive understanding of how traditional culture-based design strategies influence Chinese consumers’ purchase behaviour. Traditional cultural symbols are perceivable visual forms on clothing, constructed through established conventions and traditional customs [

14], such as styling, motifs, and colour [

15]. Traditional craftsmanship refers to techniques and skills that have been preserved through generations [

16]. Consumers usually perceive through touch or marketing content [

17]. Several design practice cases demonstrate that integrating traditional cultural symbols into modern fashion can effectively promote cultural sustainability and achieve brand differentiation [

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23]. Scholars have also examined the role of traditional craftsmanship in slow fashion and sustainable production [

24,

25,

26]. Yet few studies have empirically examined how traditional cultural symbols and craftsmanship impact consumers’ purchase intention to purchase sustainable fashion products. In the field of product design, tangible or visible symbols are usually easier to recognize and apply [

27]. However, with the transformation of “national identity” in Chinese fashion design, cultural expression has gradually shifted from the figurative “symbolic stage” to the “spiritual stage” centred on Eastern philosophy [

28]. At the relational and mechanism levels, whether explicit expression is more effective than implicit expression requires further discussion. Therefore, this study, based on SOR theory, develops a research framework, incorporating traditional cultural symbols and traditional craftsmanship as external stimuli. The objectives of this research are:

How do traditional cultural symbols and traditional craftsmanship affect Chinese consumers’ purchase intention?

How do perceived environmental benefits and emotional attitudes affect Chinese consumers’ purchase intention?

What is the difference between traditional cultural symbols and traditional craftsmanship?

The structure of this paper is as follows. The next section reviews the related literature, develops hypotheses, and constructs the research model. The methodology part outlines the research design, including the questionnaire, data collection process, and sample characteristics. Subsequently, the findings are presented and interpreted, followed by a discussion of their theoretical and practical implications. The paper then concludes by highlighting the study’s limitations and proposing directions for future research. Research findings provide new perspectives for sustainable fashion design. The present study extends the empirical research on sustainable consumption by adding traditional cultural elements into this area. This study takes into account the Chinese market, which could help companies and designers to understand the Chinese consumers’ aesthetic preferences and behavioral characteristics.

5. Discussion of Findings

This study examines the key determinants of Chinese consumers’ purchase intentions toward sustainable fashion products. Partly support the research hypothesis; others are new findings, which provide references for the research on sustainable consumption and clothing sales and product design.

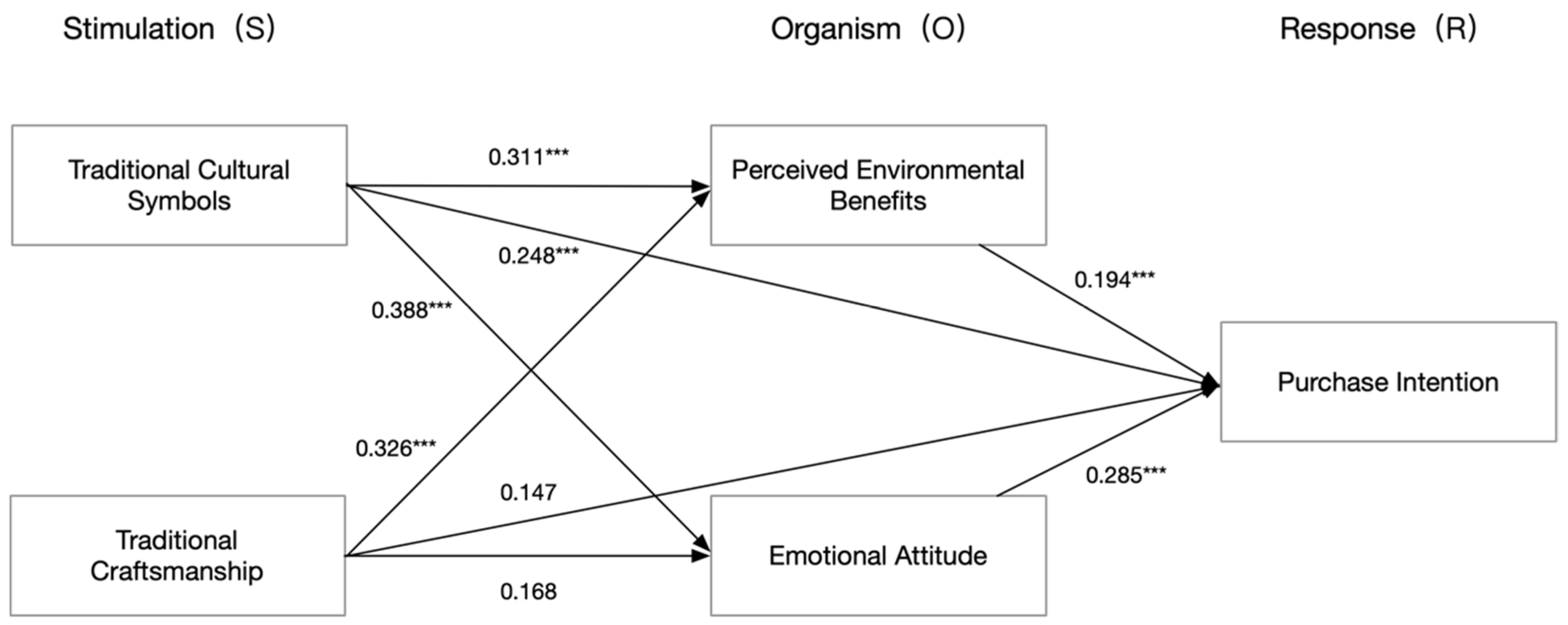

(1) Traditional cultural symbols have a significant positive effect on the perceived environmental benefits (β = 0.311; p < 0.001), which supports hypotheses H1a. It extends the research on sustainable consumption. Traditional cultural symbols help Chinese consumers recognize that sustainable fashion products are closely tied to their lives through visual images. Traditional cultural symbols have a significant positive effect on emotional attitude (β = 0.388; p < 0.001), which supports hypothesis H1b. The design strategy based on traditional cultural symbols satisfies consumers’ aesthetic and spiritual needs, generating a sense of belonging and pride. Therefore, traditional cultural symbols improve emotional attitude.

(2) Traditional craftsmanship has a positive effect on perceived environmental benefits (β = 0.326;

p < 0.001) and thereby hypothesis H2a is supported. This is in line with previous research [

17]. Traditional craftsmanship can convey a compelling, sustainable message to Chinese consumers and thereby influence their perception of the product’s environmental benefits. However, traditional craftsmanship does not have a significant impact on emotional attitude (β = 0.326;

p > 0.05); hence, hypothesis H2c cannot be supported. Maybe because in the actual production process, traditional craftsmanship cannot be directly perceived by consumers. Consumers can only know about traditional craftsmanship through the text or labels such as “handmade” or “intangible cultural heritage craft”. Furthermore, consumers need sufficient knowledge to judge whether craftsmanship is tied to local culture, which may also explain its non-significant effect on emotional attitude. This aligns with findings from product attributes research: unobservable production characteristics are primarily associated with quality rather than emotional cues [

79,

80].

(3) Perceived environmental benefits (β = 0.194;

p < 0.001) and emotional attitude (β = 0.286;

p < 0.001) have a significant positive effect on purchase intention, and thereby hypotheses H3 and H4 are supported. When some product attributes stimulate consumers, they would have evaluations on different dimensions [

30]. Perceived environmental benefits give a rational component, and an emotional attitude gives an emotional component. Both would influence Chinese consumers’ purchase intention. It should be noted that the emotional attitude (β = 0.286;

p < 0.001) exerts a significantly greater influence on the purchase intention than the perceived environmental benefits (β = 0.194;

p < 0.001), which means that Chinese consumers’ behavior is more affected by their response than by their rational thinking. The added aesthetic value is more concerned because of the specific characteristics of fashion products. Meanwhile, the influence of perceived environmental benefits is weak.

(4) Traditional cultural symbols have a direct influence on purchase intention (β = 0.248;

p < 0.001) and thereby hypothesis H1b is supported. Traditional cultural symbols satisfy consumers’ needs for aesthetics, and thus have a direct influence on purchase intention. In addition, perceived environmental benefits and emotional attitude partially mediate the relationship between traditional cultural symbols and purchase intention. This meets the requirement of consumer value orientation in the research of sustainable fashion consumption [

76]. However, traditional craftsmanship does not have a significant impact on purchase intention (β = 0.147;

p > 0.05) and thus hypothesis H2b is rejected. Maybe consumers are more interested in the appearance and style of fashion products rather than how they are manufactured. In a fashion consumption context, external stimuli about craftsmanship may take a backseat, thereby failing to directly enhance purchase intention. In addition, some consumers think that traditional craftsmanship is behind the times and unscientific, and thus they may think that traditional craftsmanship has certain limitations in functionality.

(5) Differences exist in the mechanism of action between traditional cultural symbols and traditional crafts. The mediating effect indicates that traditional craftsmanship affects purchase intention indirectly through perceived environmental benefits, while traditional cultural symbols exert both direct and indirect effects via perceived environmental benefits and emotional attitude (H5a, H5b and H6). From the perspective of symbolic consumption theory, traditional cultural symbols serve an identity display function [

81]. Their symbolic value is easily perceived by consumers, which triggers emotional responses and stimulates purchase intention. In contrast, the value of traditional craftsmanship is reflected in product quality and the manufacturing process [

82]. Furthermore, according to cue utilization theory, consumers tend to rely on external cues when product quality is difficult to assess, such as symbols [

83]. Traditional craftsmanship often requires physical contact or specialized knowledge to be appreciated. These findings share commonalities with Western research on sustainable fashion while also exhibiting distinct differences. Western studies on sustainable fashion have shown that when forming purchasing intentions for sustainable fashion, consumers place greater emphasis on factors such as production process information, consumers’ perceived level, retail environment, and social norms [

84,

85,

86], while cultural symbols are relatively secondary. This difference may be related to cultural background.

6. Conclusions

This study primarily examines the influence of traditional cultural elements on Chinese consumers’ purchase intentions for sustainable fashion products. The results show that traditional cultural symbols have a positive impact on purchase intention and that traditional craftsmanship exerts an indirect impact on it. Perceived environmental benefits and emotional attitude partially mediate the impact of traditional cultural symbols on purchase intention, and perceived environmental benefits completely mediate the impact of traditional craftsmanship on purchase intention.

The primary theoretical contribution of this study lies in constructing and validating an analytical framework based on the SOR model, systematically revealing the pathways through which traditional cultural elements influence Chinese consumers’ sustainable fashion consumption [

87]. At the construct level, traditional cultural symbols and traditional craftsmanship are distinguished as two measurable variables and incorporated into the SOR framework. Secondly, at the relational level, the study uncovers differences in the operational modes of traditional cultural symbols and traditional craftsmanship, while validating the mediating roles of perceived environmental benefits and affective attitudes. At the mechanism level, it verifies that traditional cultural symbols and traditional craftsmanship influence sustainable purchase intentions indirectly, via perceived environmental benefits and emotional attitudes as mediating factors. Finally, at the contextual level, in China’s long-term–oriented, culture-salient fashion market, traditional cultural symbols are more effective than traditional craftsmanship in driving sustainable fashion purchase behavior. Overall, this study broadens the use of the SOR model to the sustainable fashion product domain, offering novel insights into the interaction between cultural relevance and sustainable consumption behavior.

This study offers practical insights for businesses and designers on leveraging traditional elements to advance sustainable fashion consumption. For enterprises, traditional cultural content should be regarded as a vital resource in the Chinese market. Businesses can develop sustainable fashion products by integrating traditional cultural symbols into their designs as a development approach, thereby strengthening emotional connections with local consumers. Although the influence of traditional craftsmanship remains limited, businesses can still construct sustainability-aligned narratives around such artisanal techniques. These narratives can be disseminated through packaging, advertising, and short-form video channels to heighten consumer awareness of environmental benefits. For designers, traditional cultural symbols can serve as core visual elements for sustainable fashion products. Designers may extract symbols from representative traditional Chinese attire and reinterpret them through contemporary silhouettes, colour palettes, and materials to heighten appeal among target consumers. Furthermore, designers can explore integrating eco-friendly materials with traditional craftsmanship to create sustainable fashion products that convey cultural identity while embodying environmental responsibility. In practice, firms can also add clear eco-labels or QR codes on products to briefly explain the traditional element used and its environmental benefits at the point of purchase.

Although this study offers unique insights into sustainable fashion development from the Chinese market, several limitations remain. The research primarily examines how Chinese cultural orientations shape consumer preferences, potentially offering a reference for countries with similar cultural contexts (such as long-term orientation, collectivism, and national pride). However, the universality of these findings needs more validation. Future studies should survey consumer groups in culturally similar settings to confirm these results. Furthermore, the sample size of this study (N = 358) is small compared to the overall scale of the Chinese apparel consumer population, and its geographic coverage is limited. Therefore, the findings should be regarded as preliminary conclusions, and future research should validate and expand upon them using larger samples with broader geographic representation. This study explores the influence of traditional cultural elements on sustainable fashion products from the design perspective, without simultaneously incorporating other external variables such as price, quality, and value orientation. Future research can combine these variables into a single research framework to explore people’s purchase intention for sustainable fashion products.