1. Introduction

Living Labs (LLs) have evolved into a cornerstone of contemporary innovation policy and research, serving as environments for practical experimentation, co-creation, and learning. Originating in the mid-1990s at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology as an approach to study human–technology interaction through sensor-enriched spaces [

1], the concept has since expanded into a multi-disciplinary paradigm that couples social sciences, engineering, and governance. LLs differ from conventional research infrastructures by positioning users and stakeholders as active contributors in the centre of the innovation process, and not only as subjects of testing [

2]. This participatory approach has made them a compelling response to the growing recognition that technological progress alone cannot address complex sustainability challenges.

The institutionalisation of LLs accelerated in the early 2000s with their inclusion in European innovation policy and the establishment of the European Network of Living Labs (ENoLL) in 2006 [

3]. Since then, LLs have spread globally, engaging academia, public authorities, industry, and civil society in sectors like energy, health, urban development and mobility [

4,

5]. The policy rationale for this expansion follows the broader move toward mission-oriented and locally driven innovation, reflected in the European Green Deal and Horizon Europe programmes [

6]. LLs now act as spaces that connect digitalisation and sustainability transitions, offering testbeds for solutions that are context-specific, inclusive, and adaptable [

7,

8].

Despite the growing popularity of Living Labs, the field remains conceptually fragmented, characterised by divergent interpretations of what a Living Lab is: a methodology [

5], an infrastructure [

7], a governance model [

2], or an innovation ecosystem. These divergent conceptualizations generate epistemic tensions—between openness and control, experimentation and institutionalisation, and participation and technical determinism. Such plurality has enriched the field but hindered its consolidation. Evaluative approaches often reflect these inconsistencies, producing incompatible criteria and limited comparability across cases. Addressing this fragmentation requires not merely cataloguing LL characteristics but critically integrating their conceptual tensions into a unified evaluative logic.

1.1. Literature Review

Early evaluation efforts in Living Lab research centred on identifying critical success factors (CSFs) for effective co-creation, with [

9] emphasising user influence, openness, realism, and value creation, and [

10] highlighting governance clarity, early stakeholder alignment, and contextual specificity. More recent work has shifted toward structured evaluation strategies and comprehensive frameworks [

11,

12,

13,

14] marking a move from factor-based assessment to more systemic, process-oriented evaluation. Reviews consistently report terminological ambiguity, methodological inconsistency, and difficulties in assessing outcomes across projects [

15,

16,

17,

18]. LLs can be simultaneously defined as methodologies, networks, or governance mechanisms, resulting in varying interpretations of their purpose and structure. While this diversity supports flexibility and local adaptation, it impedes cumulative learning and policy comparability. A systematic review by Hossain et al. [

9] noted that the field still lacks a unified theoretical framework, with most studies being descriptive and case-based rather than analytical or evaluative. Subsequent bibliometric analyses confirm the absence of a coherent evaluative tradition, despite the growing policy relevance of LLs in innovation systems [

19,

20,

21].

Foundational methodological contributions have sought to address this gap by developing frameworks for stakeholder engagement and process evaluation. Tang and Hämäläinen [

1] introduced structured methods and tools to support everyday innovation, while Følstad [

5] provided an early conceptual synthesis linking LLs to ICT-based development. Leminen and Westerlund [

2] later expanded this into a typology of innovation tools, distinguishing user, enabler, provider, and utilizer-driven configurations. Feurstein et al. [

7] extended the concept to regional innovation ecosystems, arguing for LLs as human-centric development strategies. These frameworks laid the groundwork for understanding LLs as hybrid entities balancing research, business, and societal objectives.

Adding to these advances, empirical research has revealed challenges in actually achieving co-creation. Burbridge [

16] questioned whether LLs genuinely deliver user-driven innovation or primarily reproduce traditional R&D logics under new terminology. Overdiek and Genova [

17] examined evaluation practices and concluded that existing approaches lack temporal and systemic depth, often measuring immediate outputs but neglecting long-term impacts. Similarly, Dell’Era and Landoni [

22] argued that LLs sit uneasily between participatory design and user-centred design, requiring clearer frameworks for governance and accountability.

Sector-specific applications demonstrate both the potential and the limitations of LL practice. In urban contexts, LLs have been used to promote socio-technical innovation through citizen participation [

18]. In education, university campuses have become “living laboratories” where students, researchers, and administrators co-develop and test sustainability measures [

23,

24]. In the health sector, LLs have fostered participatory co-design of digital health tools, improving accessibility and user acceptance [

25]. In the energy domain, projects such as ENERGISE have shown that behavioural experimentation through LLs can achieve measurable and durable energy savings by reshaping social norms [

26]. More recent work has extended LLs to nature-based solutions, where Soini et al. [

27] highlight the importance of context-sensitive co-creation and equitable participation. Across these domains, LLs are increasingly viewed not just as innovation mechanisms but as socio-technical infrastructures that mediate learning between actors and scales.

Newer literature reflects a maturation of the field toward reflexivity and responsibility. Studies by Habibipour [

28] and Fauth et al. [

29] emphasise the importance of responsible LL design and the orchestration role of LLs within regional innovation ecosystems, while Arias et al. [

30] examine their institutionalisation across geographic and thematic contexts. Schuurman et al. [

21] propose a research agenda to strengthen methodological rigour and theoretical consolidation, and Blanckaert et al. [

31] critically interrogate the risks of “responsible living labs,” identifying ethical and governance dilemmas that accompany rapid diffusion. Together, these works signal a transition from experimentation to institutionalisation, where LLs must balance openness with accountability and innovation with legitimacy.

Recent studies also underline the need for evaluative frameworks that capture learning dynamics and systemic transformation. Studies on campus-based LLs [

24] and regional digital hubs [

29] propose multi-criteria approaches integrating governance, social value creation, and sustainability indicators. Longitudinal perspectives are becoming essential, as highlighted by Matschoss et al. [

19] who demonstrated that the longer-term impacts of LLs extend beyond immediate behavioural outcomes. The recent studies by Lyes [

32], Weberg et al. [

33], and Stuckrath et al. [

24] further contribute empirical evidence on LLs’ role in scaling social innovation, empowering local communities, and measuring institutional effectiveness. Collectively, they converge on a central insight: LLs represent a process of institutional learning embedded within place-specific systems, and their value lies not only in outputs but in the relationships and reflexivity they cultivate.

Nevertheless, several structural weaknesses persist. LLs often depend on short-term funding, struggle with continuity, and face difficulties in maintaining balanced stakeholder participation [

30]. Without sustained governance and evaluative continuity, many become temporary pilots rather than enduring platforms for systemic change. Moreover, evaluation practices tend to prioritise technological and economic outcomes over social and institutional learning, thereby neglecting the reflexive and temporal dimensions that distinguish LLs from conventional testbeds.

1.2. Contribution

This paper responds to these challenges by synthesising the dispersed body of literature on LLs and proposing a simple but comprehensive qualitative evaluation framework. Building on the accumulated theoretical, methodological, and empirical insights of selected works from the past two decades, it seeks to unify different approaches into an integrative lens encompassing governance, co-creation, methodology, infrastructure, outcomes, scalability, sustainability, equity, and learning. The framework embeds a temporal dimension, acknowledging that innovation processes unfold across iterative cycles of experimentation and adaptation. Finally, by applying the framework to the INNOFEIT Energy Living Lab at the Faculty of Electrical Engineering and Information Technologies in Skopje, the study provides an applied demonstration of how evaluation can inform strategic management, institutional resilience, and policy relevance.

In doing so, this work positions LLs as both experimental ecosystems and policy instruments within the governance of sustainability transitions. It argues that the future of LLs lies not only in multiplying pilots but in cultivating institutions that are capable of continuous learning and societal embedding. The added value of the proposed framework lies in its integration of multiple evaluative traditions, from early CSF-based approaches to process-oriented and contemporary systemic-temporal models. Rather than focusing narrowly on stakeholder processes, technological validation, or outputs, it brings together nine dimensions—including governance, equity, learning, and sustainability—within a temporal structure that distinguishes short-, medium-, and long-term effects. Its application to a university-based energy Living Lab offers rare empirical insights for South-East Europe and supports both cross-LL comparability and reflexive institutional development.

2. Methodological Approach

To establish a foundation for developing evaluation principles, a comprehensive review of international LL initiatives was conducted. For this purpose, the peer-reviewed literature was synthesised to identify domains of application, methodological characteristics, challenges, emerging trends, and to critically integrate the split conceptual landscape that characterises LL research. This approach allowed us to derive a set of evaluation dimensions that respond to empirical evidence, methodological inconsistencies, and theoretical debates in the field.

A simplified PRISMA-inspired procedure was used to ensure methodological transparency. Academic databases such as Google Scholar, IEEE Xplore, and Scopus, as well as research discovery platforms including Connected Papers and SciSpace, were searched for publications from 2000 to 2025. Search strings combined keywords such as “Living Lab(s)”, “innovation”, “co-creation”, “sustainability”, “evaluation”, “framework”, and “user-driven”. Only peer-reviewed journal articles, conference papers, and conceptual studies written in English were considered. Studies were retained if they explicitly discussed LL conceptualisation, governance, methodology, or evaluation; reported empirical findings from LL implementations; addressed LLs across sectors such as energy, healthcare, education, urban systems, or ICT; or identified benefits, challenges, or tools relevant to LL operation. Studies were excluded if they used the term “lab” metaphorically, focused exclusively on technical systems without socio-technical or participatory elements, lacked substantive conceptual or methodological discussion, or were non-peer-reviewed documents such as theses or editorials.

The initial search yielded more than 500 records. After removing duplicates and screening titles and abstracts, 100 articles were selected for full-text review. Of these, 31 studies [

1,

5,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34] met all inclusion criteria and were incorporated into the synthesis. The web-based sources [

2,

3,

6,

35] were used to support contextual and background analysis, while items [

36,

37,

38,

39,

40] provided supporting material for the Living Lab at FEEIT. Together, these studies reflect the diverse and often inconsistent conceptualisations of Living Labs present in the literature. Each publication was analysed using thematic coding, examining domains of application, actor configurations, governance models, methodological approaches and tools, infrastructural components, reported outputs and impacts, and recurring challenges or limitations. This process enabled the identification of converging patterns as well as conceptual and methodological tensions, including discrepancies in stakeholder influence, uneven participation depth, variations in temporal scope, and differing evaluation practices across contexts. LLs aimed at social innovation emphasise inclusiveness, whereas industrial LLs often prioritise validation efficiency. Urban LLs embrace complexity, while health-sector LLs operate under regulatory constraints. These divergences explain the absence of a shared evaluation tradition and underscore the need for a framework capable of accommodating both methodological heterogeneity and conceptual tensions.

Insights drawn from this synthesis were used to construct an argument-driven conceptual foundation for the proposed evaluation framework. Rather than treating findings as a list of themes, recurrent limitations—such as the prevalence of short project cycles, inconsistent user involvement, lack of longitudinal outcome tracking, and fragmented evaluation procedures—directly informed the inclusion of dimensions related to governance, user engagement, learning, equity, scalability, and temporal resilience. At the same time, benefits documented across sectors—including realism, iterative learning, behavioural change, value creation, and knowledge transfer—guided the development of dimensions focused on methods and tools, sustainability, and outputs and impacts. Integrating these elements enabled the design of a framework that responds to both the empirical realities and the conceptual ambiguities that shape LL practice.

The resulting evaluation framework is therefore grounded in a synthesis that acknowledges the heterogeneity of LL models and addresses the methodological inconsistencies observed across the literature. Its purpose is twofold: to provide a comprehensive evaluative lens applicable across different LL contexts and to support reflection on the current state and future evolution of the INNOFEIT Energy Living Lab at FEEIT. The following section presents the evaluation dimensions derived from this integrative process alongside their theoretical grounding.

3. State of the Art of Living Labs and Lessons Learned from Global Practices

In this section, the empirical basis for deriving principles and evaluation criteria is presented, based on an analysis of existing distributions, domains, and trends. The ENoLL, a global innovation platform connecting more than 170 active LLs across over 40 countries, classifies their activities into 23 thematic domains. These topics span from technical areas, such as energy, mobility and AI, to other social domains such as education, health and innovation [

3].

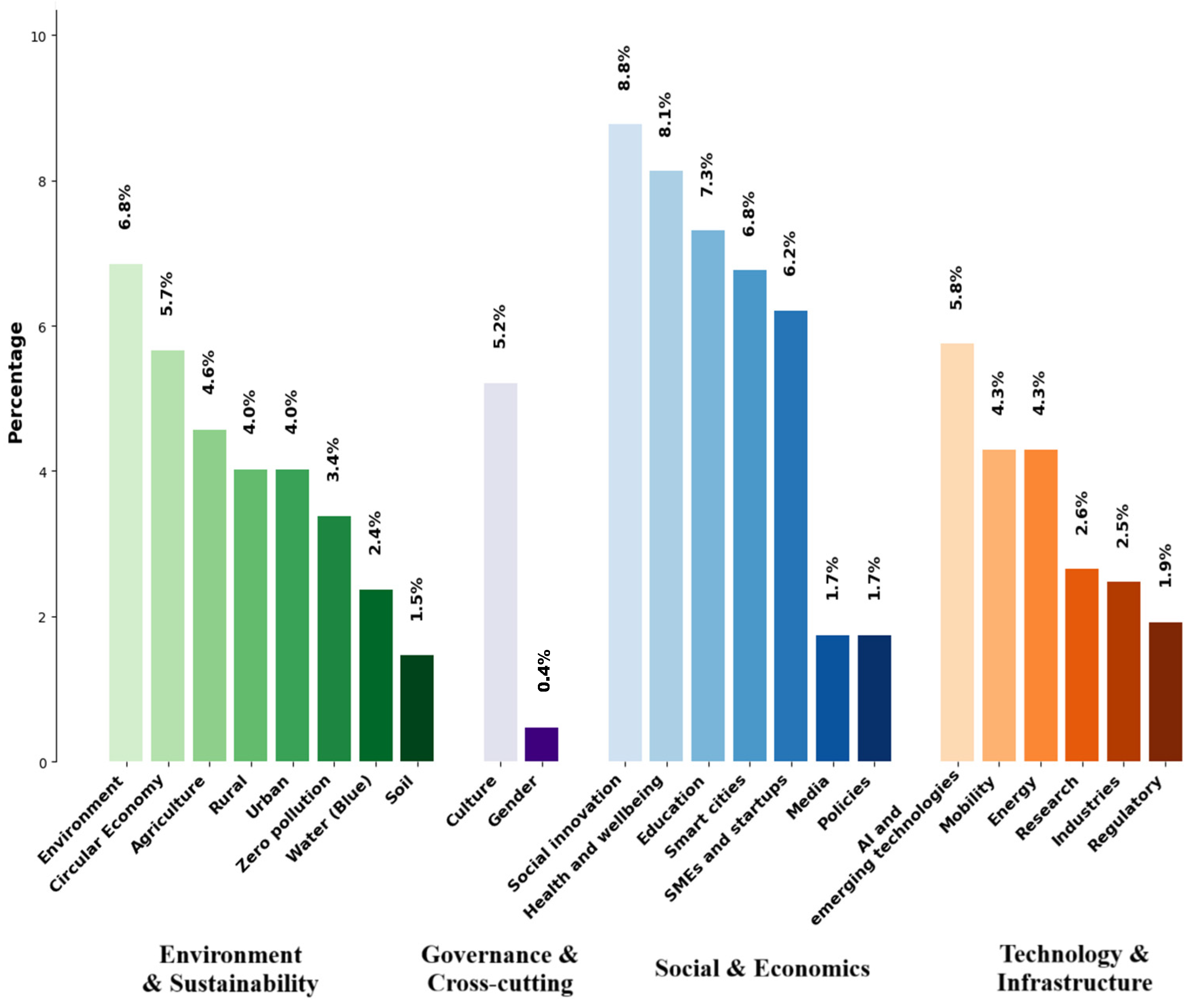

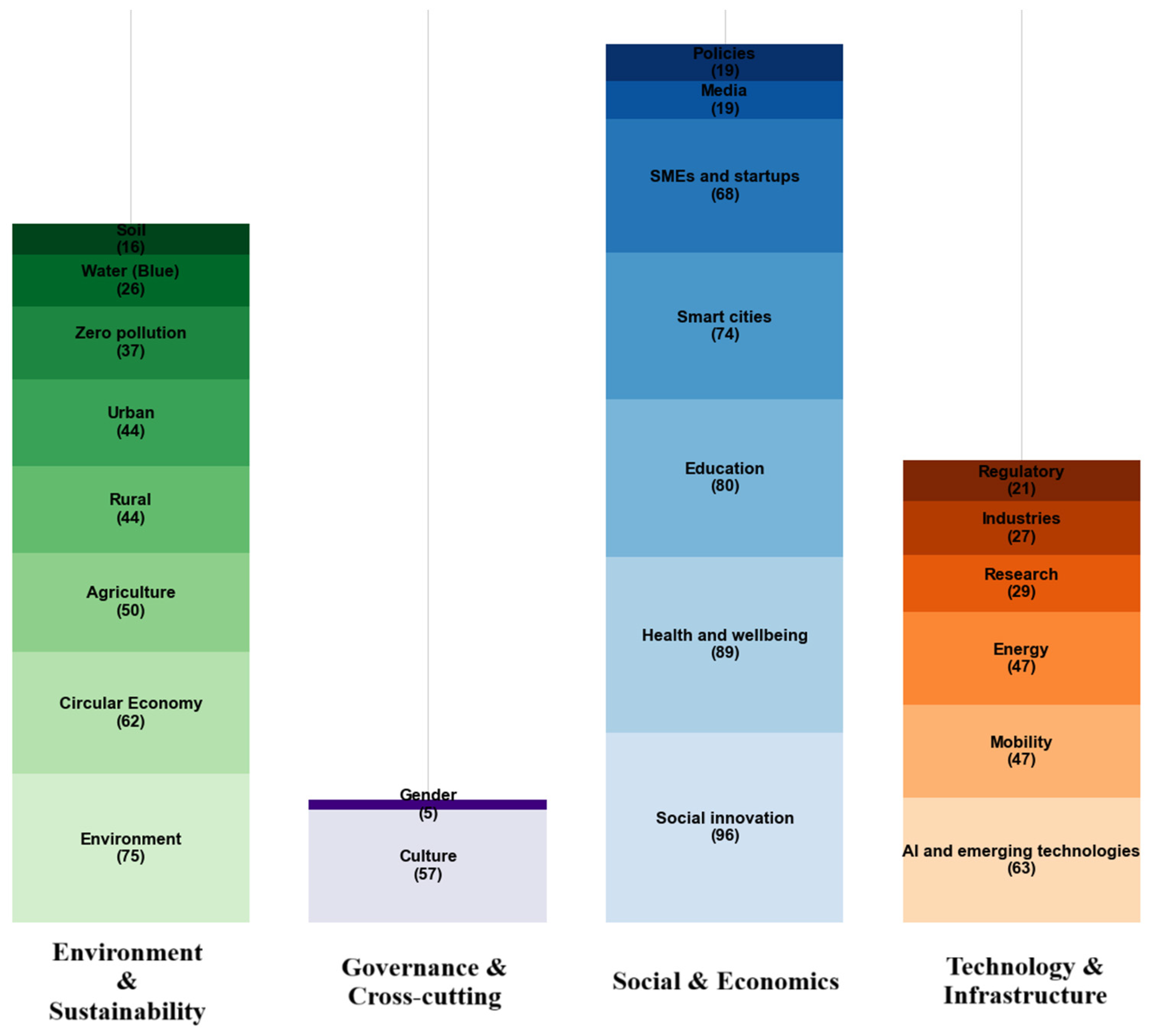

According to the most recent ENoLL data, shown in

Figure 1 and

Figure 2, the most represented domains are Social Innovation and Inclusion (8.77%), Health and Well-being (8.13%), and Education and Vocational Training (7.31%). The prominence of these sectors highlights the growing emphasis on societal well-being, inclusiveness, and capacity-building within Living Lab activities. Substantial representation is also observed in Environment and Climate Change (6.85%) and Smart Cities and Regions (6.76%). This indicates a strong link between LLs and sustainability-driven urban innovation.

Technological and economic domains such as Artificial Intelligence and Emerging Technologies (5.75%), Circular Economy (5.66%), and SMEs and Start-ups (6.21%) demonstrate how LLs increasingly function as testbeds for innovation and entrepreneurship. Meanwhile, fields like Agriculture and Agri-food (4.57%), Culture and Creativity (5.21%), and Mobility (4.29%) show the adaptability of the LL model to diverse sectoral contexts, supporting both industrial transformation and social innovation.

Conversely, some areas remain underrepresented. Topics such as Water (Blue Economy), Regulatory Learning, Policies, Media, Gender and Soil have lowest representation and participation rates. These disparities suggest that, despite their expansion, LLs are yet to fully engage with equality, policy innovation, and resource management—domains that hold potential for broadening the social and environmental impact of the Living Lab approach.

3.1. Drivers Behind Living Labs

LLs have a central role as networks of partners. They actively involve end-users and customers in testing activities and innovation development phases [

2]. While LLs are frequently presented as open and user-driven environments, the literature acknowledges that LLs differ considerably in terms of who drives the process, how collaboration unfolds, and what type of value is pursued. This diversity has contributed to a degree of conceptual fragmentation within the field, with different schools of thought emphasising market-oriented, societal, technological, or community-driven logics.

To systematise these divergent interpretations, prior research categorises LLs according to their dominant actor: utilizer-driven, enabler-driven, provider-driven, and user-driven models (

Table 1) [

5]. This typology clarifies the strategic motivations behind LL formation—ranging from market validation to policy experimentation or grassroots problem-solving—and exposes inherent tensions, such as balancing commercial objectives with participatory ideals or reconciling research timelines with industry demand. These tensions underscore why LLs do not operate uniformly, and why evaluation approaches must reflect actor dynamics and power relations rather than assuming a single LL model.

Networking across multiple LL locations further complicates the landscape. Although cross-Lab networks enable broader co-creation and reduce duplication of resources [

7], they also amplify coordination challenges, variation in governance styles, and potential mismatches between local priorities and shared objectives. Such differences contribute directly to the patchy nature of LL literature.

The actor-based drivers outlined above directly informed the design of the evaluation framework. Distinguishing between utilizer-, enabler-, provider-, and user-driven LLs shaped the framework’s dimensions on governance, stakeholder diversity, and user engagement by clarifying who initiates LL processes, influences decisions, and holds power. These configurations translate into criteria for role clarity, inclusion, and influence. Likewise, recognising how strategic motivations differ across LL types also shaped indicators addressing outputs, impacts, and diffusion potential—ensuring that the framework responds to the heterogeneous realities of LL practice.

3.2. Benefits of Living Labs

Studies show that up to 85% of new product issues stem from flaws in the design process, placing constant pressure on companies to improve their development practices to remain competitive [

7]. At the same time, there’s an increasing demand for faster and more cost-effective innovation, particularly as many advanced technologies lack viable, market-ready applications. Unfortunately, only 15% of development efforts lead to products that reach the market, and just 18% of those are sustainably successful. This is often the result of focusing on technological potential rather than actual user needs. Recognising these challenges, early innovators identified the potential of the Living Lab model to bridge this gap by aligning innovation processes with real-world contexts and user expectations [

8].

However, while these benefits are consistently cited in the literature, their realisation varies significantly across contexts—highlighting both the strengths and conceptual tensions within LL practice.

The foundational LL pillars, namely public–private–people partnerships, real-life experimentation, iterative co-creation, and open innovation, are intended to promote openness, influence, realism, value creation, and sustainability. Yet empirical studies show that these principles are not always uniformly achieved. For example, LLs promise strong user influence, but many remain technology-driven or expert-led in practice. Similarly, realism can improve ecological validity but reduces experimental control, challenging methodological consistency. Value is expected to benefit all actors but may manifest unevenly across economic, social, and environmental domains.

Sectoral cases illustrate both the potential and variability of LL benefits. University LLs such as the University of British Columbia’s Campus as a Living Lab (e.g., BRDF and SHED projects) demonstrate how sustainable technologies can be tested on campus infrastructure while enhancing student learning [

35]. Research-oriented LLs like the Savona Campus in Italy support small-scale experimentation that can feed into broader urban innovation strategies [

23]. Urban LLs such as Torino City Lab facilitate collaboration between municipalities and companies to deploy technologies that improve environmental performance [

34]. In healthcare, the Digital Health Living Lab (University of Brighton) co-designs solutions with elderly residents to enhance usability and acceptance [

25]. Energy-focused LLs, including the ENERGISE project implemented across eight European countries, have demonstrated measurable behaviour change and reductions in energy demand through real-life experiments [

19].

These examples show that LL benefits are highly context-dependent, shaped by regulatory, cultural, organisational, and infrastructural conditions. This variability highlights the need for evaluation frameworks capable of capturing both immediate outputs and long-term transformations.

The benefits above directly shaped the framework’s methodological design. Principles such as realism, iterative learning, and value creation informed dimensions like methods and tools, sustainability, and learning. Sector-specific benefits—knowledge transfer, behavioural change, and collaborative experimentation—guided indicators for short-term outputs and long-term impacts. This ensures the framework reflects both the opportunities and limitations of LL benefits as documented across sectors.

3.3. Challenges and Limitations Faced by Living Labs

Despite their potential, LLs face structural, methodological, and conceptual challenges. A key issue—repeatedly emphasised in the literature—is the lack of unified conceptual and methodological foundations, which leads to different evaluation practices and limited comparability across LLs. The multiplicity of LL definitions (as infrastructures, methods, governance tools, or community platforms) further complicates synthesis and standardisation.

Sector-specific challenges amplify these inconsistencies. In smart city LLs, aligning the interests of municipalities, technology providers, and citizens can be difficult, often resulting in projects driven more by technological imperatives than meaningful engagement [

18]. In healthcare LLs, strict ethical and data protection regulations constrain the ability to involve vulnerable groups as co-creators [

22], while pilot studies struggle to scale. In educational LLs, traditional curricula, lack of digital literacy, and institutional time constraints limit deep participation and long-term sustainability [

9].

Cross-cutting issues include short project cycles, dependence on temporary funding, inconsistent stakeholder participation, and the absence of longitudinal impact tracking. These limitations frequently result in LLs producing promising prototypes but lacking evidence of sustained behavioural, organisational, or policy impact.

These challenges shaped the structure of the framework as well. Fragmented methodologies justified adopting a comprehensive, multi-dimensional model. Short project timelines informed the inclusion of a temporal dimension differentiating short-, medium-, and long-term effects. Engagement difficulties motivated strong emphasis on governance, equity, and user participation. Challenges of scalability and limited reflexive practices supported the integration of learning, diffusion, and adaptability mechanisms. Together, these elements position the framework as a response to the limitations identified across LL research.

4. Methodological Framework for Evaluating Living Labs

The selection of the nine dimensions emerged from a structured synthesis of LL literature and from three guiding criteria: empirical recurrence across published studies, theoretical relevance to co-creation and innovation governance, and conceptual distinctiveness to avoid redundancy. For example, governance transparency and stakeholder diversity recur as determinants of effective collaboration, while continuity of user engagement and methodological rigour are frequently highlighted as essential for ensuring realistic and context-sensitive innovation. At the same time, more recent discussions emphasise equity, reflexivity, and long-term societal value creation—leading to the inclusion of equity, learning, and temporal considerations. The framework also clarifies conceptual boundaries that are often blurred in LL evaluation. In particular, it differentiates sustainability (operational and institutional stability) from temporal resilience (capacity to generate and track long-term impacts), which are frequently conflated in the literature despite having distinct implications for practice.

The framework is anchored in a Theory of Change (ToC) logic, which provides the underlying causal rationale connecting Living Lab activities, mechanisms, and outcomes. This ToC foundation rests on several assumptions observed across LL research: that real-world experimentation improves usability and acceptance of innovations; that multi-stakeholder collaboration enhances legitimacy and relevance; that iterative cycles generate cumulative learning; and that long-term societal impacts require stable participation and institutional support. These assumptions translate into mechanisms embedded in the nine dimensions—for example, governance mechanisms that ensure coordination and transparency, engagement mechanisms that allow users to influence decisions, methodological mechanisms that integrate experimentation and validation, and learning mechanisms that enable reflection and adaptation. In line with ToC reasoning, the framework distinguishes between short-term outputs (such as prototypes, datasets, or user insights), medium-term outcomes (such as behavioural change, organisational adaptation, or improved system performance), and long-term impacts (such as policy influence, technology diffusion, or societal transformation). These causal pathways justify not only the inclusion of temporal resilience but also the organisation of evaluation into progressive and iterative stages.

Based on the literature synthesis and the recurrent themes identified across Living Lab studies, nine key dimensions were selected:

Governance and stakeholders—transparency, role clarity, and diversity.

User engagement—depth and continuity of participation.

Methods and tools—balance between experimental control and real-world relevance.

Infrastructure and resources—adequacy of facilities, data, and skills.

Outputs and impacts—distinction between immediate, medium-term, and long-term effects.

Scalability—potential for replication and diffusion.

Sustainability—stability of operations and funding.

Equity—fairness and inclusiveness in participation and outcomes.

Learning—mechanisms for reflection and adaptation.

Together, these dimensions allow for a comprehensive understanding of how LLs function as socio-technical systems. They cover the structural, behavioural, methodological, and temporal aspects of Living Lab operations, capturing both the conditions that enable innovation and the results it produces. This methodological tension can be situated within the four quadrants of Living Labs, which distinguish between laboratory-based and real-context methods, as well as between traditional and ICT-mediated approaches (

Figure 3).

Consistent with the ToC logic, the evaluation process follows a four-phase cycle: Vision, Prototype, Evaluation, and Diffusion & Adoption. This cycle reflects the iterative nature of Living Labs, allowing insights generated during evaluation to feed back into earlier phases and influence strategic redirection, methodological adjustment, or stakeholder reconfiguration. It treats evaluation as a continuous learning mechanism rather than a final judgement. The process also combines qualitative methods (such as interviews, focus groups, and workshops) with quantitative indicators (such as engagement metrics, adoption rates, performance measurements, and resource utilisation), which helps address the methodological fragmentation noted in the literature and ensures that findings are both context-sensitive and analytically robust.

Figure 4 provides a visual representation of the framework’s logic. Each block corresponds to one phase of the evaluation cycle, showing how Living Lab activities evolve from defining a shared vision to prototyping, structured assessment, and eventual diffusion. The arrows between blocks represent iterative feedback mechanisms through which insights from evaluation are fed back into earlier phases, enabling adaptation of methods, stakeholder configurations, or resource allocations. The central loop illustrates how learning is embedded across all phases, ensuring that evaluation is not linear but iterative, participatory, and responsive to contextual change.

LLs are often time-bound and resource-limited, making long-term evaluation difficult. Operating under project-based structures, they frequently prioritise short-term deliverables over extended impacts, limiting the ability to trace long-term behavioural or systemic effects. Integrating a temporal perspective within the framework therefore helps ensure that even within finite project cycles, mechanisms exist to monitor and understand enduring impacts.

Overall, the framework balances comparability across Living Labs with flexibility to adapt to diverse contexts, scales, and stakeholder compositions. It aligns with ENoLL and Horizon Europe evaluation principles—including relevance, efficiency, coherence, impact, and sustainability—ensuring compatibility with broader research and policy agendas. The conceptual block diagram of the proposed evaluation framework is presented in

Figure 4.

In the following section, the framework is applied to the Living Lab at the Faculty of Electrical Engineering and Information Technologies (FEEIT) to assess its governance, stakeholder collaboration, methodological practices, and contribution to sustainable innovation within the Macedonian context.

5. Case Study—INNOFEIT Energy Living Lab

5.1. Functional Description of the INNOFEIT Energy Living Lab

The INNOFEIT Energy Living Lab is a newly established initiative, funded by the Ministry of Economy and Labour, to enhance R&I capacity in alignment with the Smart Specialisation Strategy. It’s still in the process of expanding its infrastructure, governance model, and participatory mechanisms. Rather than being defined by its equipment, the Living Lab operates as a socio-technical system in which physical infrastructure, digital platforms, and human activities converge to support experimentation, learning, and innovation.

The facility includes several interaction and experimentation zones—collaborative workspaces, test rooms, a smart IoT laboratory, and monitored offices—that enable the design, testing, and evaluation of energy-related solutions under realistic operating conditions. Across these spaces, the Living Lab integrates interconnected subsystems such as thermal regulation, renewable energy generation and storage, electric mobility, environmental sensing, and digital monitoring platforms. These subsystems allow users to simulate energy flows, optimise control strategies, monitor performance, and study user–technology interaction on-site.

The operation of the Living Lab can be understood as a dynamic interaction between its thermal, electrical, and digital subsystems. Energy is generated on-site through photovoltaic panels, stored in the battery system when available, and distributed throughout the building based on real-time conditions monitored by environmental sensors and the central automation platform [

36]. The thermal system—comprising the heat pump, fan coils, and adaptive shading—responds to occupancy patterns and climatic conditions, while the digital control layer continuously optimises energy flows to balance comfort, efficiency, and system performance. As the integration deepens, the Living Lab functions as a real-world microgrid, providing an environment for experimentation, scenario testing, and iterative learning across the nine evaluation dimensions of the proposed framework.

At this stage, the lab supports several dimensions of the evaluation framework:

Governance and stakeholders: coordination between FEEIT, INNOFEIT, industry partners, and academic users.

User engagement: use of physical zones for workshops, co-design activities, and student-led experimentation.

Infrastructure and resources: availability of sensors, IoT platforms, renewable energy systems, and real-time monitoring tools.

Learning: early activities already support experiential learning and course integration

Sustainability and scalability: integration of PV generation, battery storage, demand–response scenarios, and potential for replication in other institutional settings.

To support transparency and clarity,

Table 2 summarises the Living Lab’s main functional subsystems and their relevance to the evaluation framework.

5.2. Purpose and Role of the Living Lab

As an emerging Living Lab, the INNOFEIT initiative serves as an initial platform for innovation, interdisciplinary collaboration and development of practical skills thorugh experimentation and demonstration in the energy sector. By creating a real-life environment for testing technical solutions, it bridges the gap between theory and practice, supporting research and development in fields such as renewable energy, energy storage, automation, and system optimisation [

37]. Researchers and students can develop and evaluate algorithms for energy management and load and storage optimisation, as well as test the performance of automation systems under realistic conditions [

38].

Although still in development, the Living Lab offers students hands-on experience, project-based learning and prototype testing [

39]. It enables practical learning across multiple disciplines, including power engineering, electronics, computer science, and automation [

33]. This allows for assessing the impact of different design and control strategies in real-world conditions. By bridging academic learning with industry practices, the lab also enables companies to deploy their solutions and test products before investing further in product development.

6. Results: Application of the Evaluation Framework on INNOFEIT Energy Living Lab

The evaluation of the INNOFEIT Energy Living Lab was conducted using the proposed Iterative Evaluation Framework to understand how the Lab is progressing during its formative phase. The purpose was to determine how effectively the Lab embodies the guiding principles of openness, influence, realism, value, and sustainability, while acknowledging the time-bound and resource-limited nature typical of most LLs. A mixed-methods approach was adopted, combining preliminary system-level data (energy generation, usage, meteorological and environmental monitoring), semi-structured interviews, student research projects, and documentation from ongoing collaborations with academic and industrial partners. This triangulation enabled the integration of operational indicators with qualitative insights. The evaluation followed our structured qualitative protocol inspired by formative Living Lab assessments [

11,

13]. Given the Lab’s early development, the data sources were exploratory and included semi-structured interviews, internal workshops, document analysis, and initial system-data reviews. Stakeholder participation was primarily internal—students, researchers, and technical staff—reflecting the current governance and user base. This concentration of expert perspectives introduces potential bias, mitigated through triangulation and cross-validation with early external collaborators, including industry partners and GoToTwin [

40] researchers. As the Lab matures, future cycles will incorporate broader participation from citizens, community groups, and policymakers.

Table 3 summarises the evaluation results, complemented by a dimension-by-dimension analysis. Where possible, semi-quantitative metrics are included to enhance transparency and demonstrate operational maturity. Overall, the evaluation indicates that INNOFEIT is at an early yet highly promising stage of development, characterised by strong infrastructure readiness, initial stakeholder engagement, and emerging methodological and organisational processes.

The governance structure remains academically led, coordinated by FEEIT and INNOFEIT, with project priorities and infrastructure use guided by research and educational needs. Industrial engagement is developing: Kontron is currently an active user, working on optimising inverter operational modes, and a second company has expressed interest in telemetry and digital twin applications, pending completion of the system. The Lab is embedded within the GoToTwin network, where its digital twin and monitoring architecture are being integrated with four partner Living Labs in North Macedonia, Serbia, Croatia, and Greece. This cross-border collaboration significantly extends the Lab’s reach and external visibility. Additionally, INNOFEIT has initiated the process of applying for ENOLL membership. Broader governance, however, still lacks representation from citizens and public authorities, which limits societal alignment.

Engagement is currently centred on students, researchers, and early industrial partners. Two ongoing student projects—a master’s thesis on the meteorological station and a bachelor’s thesis on PV power quality—together with several mini student projects demonstrate the Lab’s strong educational integration. Industrial co-creation is present through Kontron’s work. However, a key limitation is the limited involvement of citizens and non-technical users during its early development. Because the Lab originated as a research- and infrastructure-driven initiative within an academic setting, participation was largely expert-oriented. This enabled rapid technical progress but reduced opportunities for broader community engagement, despite Living Lab literature emphasising early and continuous user involvement. To address this gap, the Lab is now developing participatory mechanisms—such as an open-access digital twin interface and public engagement workshops—to better integrate citizens, non-engineering students, and local community groups into future co-design and evaluation cycles. A public open call is planned for the future, expected to broaden participation and include non-technical and community users in co-design activities. In parallel, the team is preparing an open-access digital-twin platform to support remote, low-barrier public engagement.

Methodologically, the Lab has begun implementing the four-phase cycle (Vision, Prototype, Evaluation, Diffusion & Adoption), primarily within teaching and research projects. A major milestone is the completion of the digital twin of the PV plant, presented in Slovenia, marking a significant step towards real-time simulation, remote participation, and advanced optimisation studies. A second digital twin for telemetry is under development and currently on hold until key components are finalised. Establishing standardised documentation and evaluation protocols will be essential as the Lab transitions into more regular cycles of co-creation.

From an infrastructure perspective, the INNOFEIT Living Lab is highly advanced for its developmental stage. It integrates 22 kWp of photovoltaic capacity, battery storage (8 kWh), multiple inverters, an EV charging station, hybrid heating and cooling systems, an IoT laboratory, and more than 180 sensors, all unified within a PLC-based central monitoring and control system. A rooftop meteorological station provides measurements of irradiance, temperature, humidity, wind, and precipitation, enabling prediction, optimisation, and digital twin model validation. The Lab’s technical resources are robust enough to serve as a regional testbed, and its integration within the GoToTwin network connects its architecture to four additional Living Labs.

Short-term outputs are substantial, including student theses, datasets, digital twin models, prototypes, and early industrial use cases. Medium-term outcomes—such as strengthened collaboration with regional LLs, increased industrial cooperation, and enhanced technical expertise—are already emerging. Long-term impacts, including behavioural change, policy effects, and technology transfer, remain unobservable at this stage, largely due to the limited operational timeframe. Similarly to other early-stage LLs, INNOFEIT’s project-based structure has encouraged a focus on measurable short-term results rather than longitudinal tracking. Establishing a system for long-term outcome monitoring will be important for enhancing temporal resilience.

Environmental sustainability is embedded through renewable energy integration, energy-efficiency optimisation, and data-driven operations. Institutional sustainability, however, depends on continued research funding and successful ENOLL integration. Equity is present through academic accessibility, but broader inclusion remains a developmental goal. Learning processes are strong within academic activities but would benefit from more formalised reflective structures. Although the evaluation did not explicitly employ an action-learning methodology, several components—such as iterative workshops, reflective student projects, and ongoing industry collaboration—naturally generated action-learning dynamics. Future evaluation cycles may incorporate a more structured action-learning approach to more effectively capture mutual learning and co-design among diverse stakeholders. Temporal resilience is currently low due to the short operational period, though plans for longitudinal tracking and the expansion of digital twin capabilities indicate future improvements.

Overall, the strongest aspects of INNOFEIT are its infrastructure readiness, methodological experimentation, and research-educational synergies. Areas requiring development include wider user integration, diversified governance, sustained engagement mechanisms, and systematic long-term evaluation. The planned public digital twin interface, upcoming open call, and expanding cross-border collaborations position the Lab well for its next phase.

Applying the proposed framework as a recurring assessment tool—linking short-term outputs to medium- and long-term societal impact—will further support continuous learning and ensure that INNOFEIT evolves as a sustainable, inclusive, and scalable model for energy innovation within North Macedonia and beyond.

7. Conclusions

This systematic review examined more than a decade of scholarly research on LLs, highlighting their evolution into dynamic platforms for user-centred, co-creative innovation across diverse sectors. The analysis identified the main domains of application, methodological frameworks, and operational tools, alongside the recurring benefits and challenges that shape their implementation and outcomes.

Findings confirm that while LLs enable meaningful stakeholder collaboration and real-world experimentation, they continue to face limitations such as conceptual ambiguity, inconsistent stakeholder engagement, limited scalability, and fragmented evaluation practices. Building upon these insights, this paper proposed an enhanced evaluation framework that integrates governance, co-creation, methodological diversity, infrastructure, outcomes, and sustainability—complemented by a temporal dimension to assess both immediate and long-term impacts. The evaluation framework is not only analytical but also developmental—it supports continuous improvement, tracking, and strategic evolution of the Living Lab.

Applying the framework to the INNOFEIT Energy Living Lab demonstrated its capacity to generate structured, multidimensional insights into an early-stage LL. The evaluation revealed several strengths, including advanced technical infrastructure, initial implementation of iterative LL methods, and strong integration within educational activities. The recent completion of the digital twin of the PV system, early industrial involvement, and cross-border collaboration through the GoToTwin network illustrate rapid progress in the Lab’s technological and organisational development. At the same time, the assessment highlighted areas requiring further attention—particularly the diversification of stakeholders, earlier inclusion of non-technical users, the formalisation of reflective learning processes, and the establishment of mechanisms for long-term impact tracking. These findings underscore the framework’s ability to expose both capabilities and gaps, making implicit processes visible and guiding future development.

Beyond the case study, the proposed framework offers broader relevance for the Living Lab community. Its multidimensional structure provides a common vocabulary for comparing LLs operating in different sectors or national contexts, while the temporal dimension addresses a persistent gap in existing assessment approaches. Nevertheless, several limitations should be acknowledged. Effective use of the framework requires access to reliable data, continuity of stakeholder engagement, and institutional support—conditions that may be challenging in resource-constrained or project-based environments. Furthermore, while the framework is adaptable, its applicability depends on careful contextualisation to the socio-technical dynamics of each Lab. Additional testing across diverse LLs is needed to refine indicators and validate the framework’s robustness and generalisability.

Future work should focus on operationalising the framework into measurable performance indicators, developing participatory evaluation instruments, and exploring digital tools—such as dashboards or digital twins—that can support real-time monitoring and longitudinal learning. Cross-Lab comparative studies, particularly within networks such as ENOLL and GoToTwin, would help establish benchmarks, reveal systemic patterns, and advance theoretical foundations for LL evaluation.

Ultimately, Living Labs represent critical infrastructures for the green and digital transitions, but their effectiveness depends on structured, reflexive, and inclusive evaluation practices. By offering a holistic and temporally sensitive framework, this work contributes to strengthening Living Labs as sustainable, socially embedded, and evidence-based innovation platforms capable of supporting societal transformation.