Abstract

Goat farming represents a critical component of rural livelihoods, food security, and cultural heritage in southeastern Tunisia. This study adopts a multi-stakeholder approach to analyze the goat value chain in Tataouine, incorporating focus groups, semi-structured questionnaires, and direct observations with 80 farmers, 3 veterinarians, 13 butchers, and 100 consumers. The findings reveal strong local demand, with 72% of consumers purchasing goat meat and 66% consuming milk. However, significant inefficiencies exist, particularly a misalignment between production and market requirements: while 92% of butchers prefer fattened animals, only 16% of farmers engage in fattening practices. Women constitute 49% of dairy processors, yet face persistent resource constraints. Climate pressures exacerbate these challenges, with 80% of farmers reporting water scarcity and 93.8% observing pasture degradation. Three strategic interventions emerge as pivotal for sustainable development: targeted support for feed-efficient fattening techniques, establishment of women-led dairy processing collectives, and implementation of climate-resilient water management systems. These measures address core constraints while leveraging existing strengths of the production system. The study presents a transferable framework for livestock value chain analysis in arid regions, demonstrating how integrated approaches can enhance both economic viability and adaptive capacity while preserving traditional pastoral systems.

1. Introduction

Goat farming in southeastern Tunisia, particularly in Tataouine, plays a vital role in sustaining rural livelihoods in semi-arid and arid regions. Historically rooted in pastoral nomadism, this practice depended on natural migratory routes to exploit limited and irregular forage resources [1]. Local goat breeds are renowned for their exceptional adaptability to environmental variability, low energy requirements, and efficient utilization of body reserves [2]. However, socio-economic transformations such as agricultural mechanization and the intensification of cereal, fruit tree, and olive cultivation have gradually shifted traditional nomadic systems toward sedentary and semi-sedentary practices. These evolving systems increasingly incorporate agricultural residues as feed resources [3,4,5].

The goat population in Tataouine has undergone significant fluctuations, rising from 102,410 in 2011 to 141,450 in 2014, before sharply declining to 79,020 in 2021 [6,7]. These variations reflect the combined impacts of desertification, modern agricultural practices, and economic pressures [8]. Climate change has further exacerbated these challenges, intensifying water scarcity and pasture degradation. Irregular rainfall patterns and extreme temperatures directly affect reproductive performance and overall goat productivity, highlighting the urgent need for structural adjustments to ensure sustainable livestock systems [8]. Nevertheless, on a global scale, goat populations have grown more rapidly than other livestock species, such as cattle and sheep, due to their adaptability to harsh climates and the increasing demand for goat meat, which is often preferred over lamb [9]. This trend is also evident in Tunisia, where the goat population expanded from 739,000 to 922,000 between 2019 and 2022 [7]. However, as Peacock [10] emphasizes, effective governance, infrastructure investments, and policies that promote modern livestock practices are crucial to unlocking the sector’s full potential.

Arid rangelands remain indispensable for livestock production, covering approximately two-thirds of Tunisia’s grazing areas and supplying between 20% and 60% of livestock feed requirements [11,12]. Local goat breeds, highly adapted to these harsh conditions, have become increasingly preferred by breeders for their resilience and ability to thrive where cattle and sheep struggle. However, the absence of structured genetic improvement programs and the historical focus on adaptive traits over productivity have limited their economic potential [1,13]. Atoui et al. [14] estimate the average live weight of local goats to be approximately 24.69 kg, a figure significantly influenced by climatic conditions and suboptimal management practices.

The goat value chain currently faces considerable challenges due to poor coordination and weak governance, limiting its overall efficiency. A comprehensive analysis of this value chain is essential to identifying bottlenecks and improving interactions among farmers, butchers, and consumers [15]. Additionally, goat breeders have limited access to land ownership, while credit constraints remain a critical barrier, especially for women. Therefore, policies should focus on strengthening women’s resilience and integrating them into trade networks [8]. In this regard, research by Duguma and Debsu [16] demonstrates that women’s involvement in livestock management not only enhances household incomes but also contributes to the economic sustainability of farming systems.

Despite the fundamental role of goat farming in the region, comprehensive studies on the goat value chain in southern Tunisia, particularly in Tataouine, remain scarce. This study represents one of the first in-depth analyses of the region’s goat value chain, offering fresh insights into its dynamics, challenges, and opportunities for sustainable development.

This study aims to:

- Identify, describe, and analyze the goat value chain in Tataouine, exploring the roles of farmers, butchers, consumers, and various stakeholders involved in this sector.

- Assess the socio-economic and environmental factors affecting goat farming profitability, including challenges such as climate change and resource limitations.

- Identify key opportunities for enhancing productivity and market access to improve governance and value chain coordination.

- Evaluate the potential of the goat value chain for sustainable growth, considering both environmental and economic sustainability.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

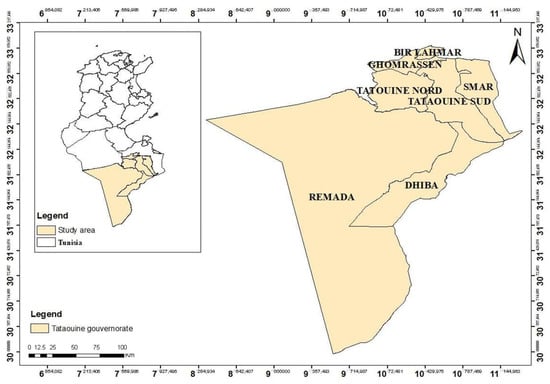

The study was conducted in the governorate of Tataouine, located in the southeast of the Republic of Tunisia (32°55′40″ N, 10°26′57″ E) (Figure 1), covering 8 delegations or districts. It is characterized by a fairly large area, diversified natural resources (oil, gas, useful substances, and groundwater), and important geological, archaeological, and natural sites. The prevailing climate in Tataouine is desert, with very high temperatures in summer and about 116 mm of precipitation each year [17]. Tataouine’s economy is based on the agricultural sector due to inherited traditions in raising and planting fruit trees, mobilizing runoff water, and camel and small ruminant breeding. The goat and sheep population in this zone is approximately 525,000, with a production of 900 tons of goat meat and 300 tons of goat milk in 2022 [18].

Figure 1.

Geographic location of Tataouine governorate.

The Tunisian indigenous Arbi goat (also called ’Bedouin’ or ’Moor’ goat) dominates the study region. This hardy breed is recognizable by its small size and dark brown to black coat with long hair. While morphologically similar to Berber goats of neighboring countries [19], the Arbi shows distinct genetic adaptations to arid conditions [1].

2.2. Analysis of the Goat Value Chain in Tataouine

This study represents the first comprehensive analysis of the goat value chain in Tataouine, a region that has been largely overlooked in previous research. By employing a multi-stakeholder approach [20], the study provides new insights into the dynamics of goat farming in this arid environment, addressing critical gaps in the literature. The analysis was conducted through a structured, five-step methodology designed to comprehensively explore the various stages of the value chain, from production to consumption. Each step was critical in ensuring a complete and accurate understanding of the key actors, practices, and dynamics influencing the goat farming sector in the region.

2.2.1. Step 1: Exploratory Analysis

This exploratory phase aims to map the different links in the goat farming value chain, from production to marketing, while identifying the key actors involved at each stage and analyzing their roles and interactions. One of the expected outcomes of the focus groups is to create a geographic representation of the goat farming activities in Tataouine, covering production areas, processing sites, and marketing locations to facilitate the fieldwork.

For this purpose, three focus groups were organized as part of the exploratory step to collect crucial information for analyzing the goat farming value chain in Tataouine. The first focus group gathered 15 breeders from Tataouine governorate, who shared valuable firsthand testimonies and insights based on their direct experience with goat farming. Their input provided a clearer understanding of the practical challenges faced by farmers, including issues related to livestock management, input supply, market access, and animal health. The second focus group involved researchers from the Arid Regions Institute of Tataouine (IRA). These discussions focused principally on challenges such as water scarcity and land degradation, which are crucial factors influencing productivity and sustainability in the sector. The third focus group brought together 16 engineers and technicians dealing with this sector (ODS; OEP; CRDA).

2.2.2. Step 2: Stakeholders Sampling

Given that Tataouine is composed of 8 districts(Tataouine North, Tataouine South, Smar, Beni Mhira, Bira Lahmer, Ghomrassen, Dhehiba, and Remada), the sampling methodology was designed to ensure the representation of each district in the region. A stratified random sampling approach was applied. Participants were then randomly selected from each district to ensure a representative sample from all geographic areas, capturing the diversity of stakeholders involved in the goat farming value chain across the region. The sample of this study is composed of 80 goat farmers, 3 veterinarians, 13 butchers and 100 consumers.

2.2.3. Step 3: Data Collection

Data collection was carried out in 2021–2022 using semi-structured surveys designed to collect information on several aspects of the goat value chain, including:

- Socio-economic characteristics of the goat farmers: age, educational level, breeding experience, herd size, land status, feeding and fattening practices, herd management, relationships with butchers, etc.

- Veterinary practices: Their impact on productivity and quality of goat products, their collaboration with other actors in the value chain, etc.

- Butcher practices: Criteria for buying animals, selling prices, relationship with the breeders, places of supply and sale, meat processing, etc. (Files S2 and S3).

- Consumer behavior: Meat preferences, frequency of consumption, accepted price, places of purchase, perception of meat quality, etc. (File S1).

The questionnaire underwent pre-testing with a small sample of farmers (15) and technicians (3) to ensure clarity and relevance. Based on their feedback, minor revisions were made, particularly in phrasing and question order, to improve the ease of response and ensure that the questions were culturally appropriate. These adjustments were carried out in collaboration with experts from the IRA. Surveys were then administered in the field, with direct interviews.

This period (2021–2022) was chosen due to the lack of comprehensive data on the goat value chain in southeastern Tunisia, and no significant historical data were available for comparison.

2.2.4. Step 4: Data Analysis and Goat Value Chain Mapping

Collected data were processed and analyzed using IBM SPSS 22. Descriptive analysis was conducted to summarize the demographic and socio-economic characteristics of farmers, butchers, and consumers. Frequency statistics were used to highlight the main trends in livestock practices, consumer preferences, and butchers’ strategies. Relationships between the variables were analyzed using Pearson’s correlation test to assess the intensity and direction of associations between continuous variables, such as herd size and total revenue, as well as the relationship between butchers’ selling prices and consumer acceptance. Chi-square tests were applied to examine associations between categorical variables, such as education level and fattening adoption, and to assess the relationship between fattening practices and farmer demographics. A Student’s t-test was used to compare total revenue between farmers practicing fattening and those who do not, providing insights into the economic impact of fattening adoption. Additionally, correlation tests for proportions were applied to analyze relationships based on percentage-based data, enhancing the understanding of various factors influencing the goat value chain.

These statistical analyses were then used to map and refine the goat value chain, allowing us to visualize the flow of goods, information, and economic value across the goat value chain. This helped identify key value-adding activities and potential areas for improvement.

Finally, a SWOT analysis provides further insights into the challenges and the improvement potential in the sector [21].This analysis identifies the best match between internal resources, key competencies, and competitive advantages while highlighting limitations. It helps assess external opportunities and threats alongside internal strengths and weaknesses [22].

2.2.5. Step 5: Presentation and Validation of the Value Chain Results

The value chain mapping was validated through a focus group composed of 8 farmers, 3 engineers and 2 technicians from the CRDA and OEP, 2 researchers from the IRA, and 2 butchers. This validation process ensured the accuracy and relevance of the findings, while also incorporating the perspectives of stakeholders directly impacted by the challenges and opportunities identified in the SWOT analysis.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Analysis of the Goat Farming Value Chain in Tataouine: Key Actors, Interactions, and Dynamics

This section provides a comprehensive analysis of the goat farming value chain in Tataouine, leveraging insights gathered during the focus group discussions and supplemented by data collected through field surveys. These surveys provided detailed information on socio-economic characteristics of goat farmers, butcher practices, and consumer behavior (Table S1 resume all the numerical results). This dual approach ensures a thorough understanding of the value chain, highlighting its multifaceted nature. Five links in the goat value chain representing the main actors have been identified and described [23].

3.1.1. Input Suppliers

Input suppliers play a pivotal role in the goat farming value chain, providing essential resources that ensure the smooth operation and productivity of the entire production process. In Tataouine, inputs include essential resources, such as livestock, feed, vaccines, and medicines, as well as vital services like veterinary care, credit, and training [24].

Results showed that the majority of goat farms in Tataouine are rearing local breeds, which are well-adapted to the desert environment but exhibit low productivity [25]. Approximately 95% of herds are composed of local Tunisian breeds (‘Arbi’), characterized by their small size, dark coat, and remarkable resilience. However, despite their genetic distinction from neighboring Berber breeds [19], they have not benefited from structured genetic improvement programs, limiting their economic potential [1]. The remaining 5% are sourced through interregional livestock trade. These animals are imported from six neighboring governorates, Medenine, Gabes, Sfax, Sidi Bouzid, Kasserine, and Kairouan, as well as from two neighboring countries, Algeria and Libya [26]. This trade, while limited, facilitates disease transmission and introduces risks to local herds, further complicating animal health management in the region.

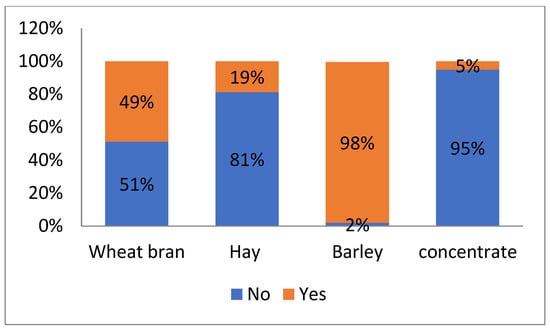

Barley, the primary feed source (used by 98% of farmers), has seen rising prices from TND 0.36 to TND 0.54 per kg (USD 1 = TND 3.03 in 2022), and frequent shortages, further complicating feed supply. These challenges align with findings from other Tunisian Governorates. For instance, Chniter et al. [27] and Bedhiaf et al. [28] identified feed costs and availability as major obstacles in southern Tunisia’s goat farming systems. Similar issues have been reported in Sidi Bouzid, where the demand for subsidized barley exceeds supply, forcing farmers to purchase feed at higher prices from informal markets. Comparable challenges are also evident in arid countries like Jordan, where producers rely on insufficient subsidized supplies and must supplement feed at their own expense [29]. These factors collectively undermine the profitability of goat farming in Tataouine.

Livestock feed supplies remain a critical issue in the region. Local grain shortages and global market instability, exacerbated by the war in Ukraine that started in 2022, have severely disrupted agricultural systems, particularly goat farming in Tataouine. In March 2022, the National Office of Fodder (Office National des Fourrages) distributed 5000 quintals of barley. However, the total allocation for Tataouine from February to March 2022 reached 49,000 quintals. This distribution is managed through 16 SMSA (Mutual Agricultural Services companies which operate across the region’s eight delegations [18]. While the SMSA plays a crucial role in facilitating access to subsidized barley and providing technical support, the supply remains insufficient to meet demand. Consequently, farmers must turn to approximately 300 local market points, where barley prices range from TND 30 to 35 per 50 kg bag, significantly higher than the subsidized rate of TND27. This disparity highlights the persistent challenges in achieving an affordable and balanced feed supply chain [27]. Similar inefficiencies are observed in other studies, where intermediaries dominate livestock transactions, driving up costs for producers and butchers [28,30]. While suppliers cite rising transportation costs as a contributing factor, farmers advocate for stricter governmental oversight to curb opportunistic practices.

In Tataouine, veterinary services face significant challenges. According to the survey, which included three private and two public veterinary doctors, the number of professionals remains insufficient relatively to the vast geographical area of Tataouine, which spans approximately 38,889 km2. The availability of veterinary services is limited, particularly in remote areas and only 3% of livestock farmers benefit from publicly funded vaccination programs, forcing most to rely on costly private veterinarians. This reliance complicates animal health monitoring and exacerbates the risk of disease outbreaks. The challenges reported by the veterinarians include a lack of transportation and analysis laboratories, which hinder their ability to provide comprehensive care. Although health coverage for livestock is estimated at 25%, diseases remain a major concern due to their impact on productivity and public health. Many of these diseases are zoonotic, posing risks to both animals and humans [31]. Similar issues have been observed in other regions, such as Pakistan’s Chakwal District, where free veterinary care is provided but limited by resource constraints [32]. Scholars, including Chniter et al. [27], argue that the vastness of Tataouine makes comprehensive veterinary coverage nearly impossible with current resources. This highlights the urgent need for improved infrastructure, increased staffing, and better resource allocation to address these gaps in veterinary services. Strengthening veterinary services and disease control programs is essential to mitigate these risks and promote livestock development [33]. This situation mirrors challenges in other arid regions, such as Syria and Jordan, where limited infrastructure and resource allocation similarly hinder effective animal health management [29].

Access to credit and financing remains limited for farmers in Tataouine, hindering their ability to invest in quality inputs. According to our findings, only 5% of livestock farmers have accessed credit or investment opportunities. While funding sources exist through state institutions and microfinance structures, farmers’ reluctance to provide guarantees often impedes access. These economic challenges are consistent with findings in central Tunisia and Jordan, where small farmers face similar barriers [29,34]. Structural weaknesses in value chains disproportionately affect small-scale producers, limiting their access to competitive markets [35,36].

The Initiative for the Promotion of Agricultural Value Chains [37] highlights alternative financing models, such as value-chain interfacing, which involve collaboration between producers, buyers, and facilitators. These models have proven effective in addressing credit challenges and improving financial resource allocation. Expanding microfinance initiatives, such as Micro-Credit Associations (AMCs) and Microfinance Institutions (MFIs), could enhance financing access for smallholders in remote regions like Tataouine. Strengthening farmer cooperatives and value-chain alliances could further improve credit access and financial sustainability [37].

Addressing the limitations in input supply, veterinary services, credit access, technical training, and water management is crucial for improving the profitability and sustainability of goat farming in Tataouine. Moreover, enhanced governance, infrastructure, and farmer support services are essential to strengthen the goat value chain [38], and especially ensure the resilience of smallholder farmers in the region who predominantly rely on traditional systems and where the extreme climatic conditions exacerbate the difficulties in accessing inputs and impact the profitability of livestock farming.

3.1.2. Production

Breeders Demographic Profile

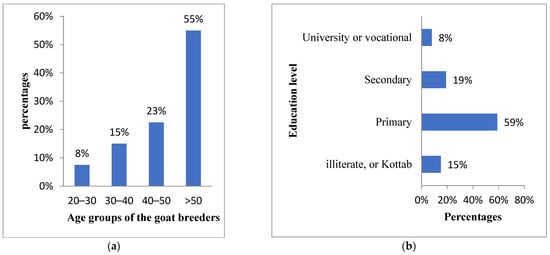

The demographic profile of goat farmers in Tataouine reveals predominantly male producers (95%), with an average age of 51, and an experience of 23 years in goat farming. While this experience is a valuable asset, it is coupled with a low level of education (Figure 2). Indeed, 59% of the goat breeders have only a primary level of education, while 15% are illiterate or attended only Kottab (traditional Quranic schools focused on basic religious instruction and Arabic literacy). This gap poses a significant barrier to the adoption of new technologies and optimized herd management practices. Similar challenges are observed in other arid regions, such as Jordan, where over 59% of small ruminant producers are illiterate and rely on traditional practices [39]. Furthermore, Chniter et al. [27] emphasize that low education levels among breeders in southern Tunisia limit the adoption of innovative livestock practices, which could otherwise enhance productivity.

Figure 2.

Distribution of goat breeders in Tataouine by age (a) and education level (b).

The current work results showed that the average size of farm households in Tataouine is six (6) members, which influences the availability of labor for herd management. In Tataouine, young people under 16 years old play a significant role in tasks such as grazing and watering animals. However, relying on children for these activities often limits their ability to perform tasks efficiently due to their lack of experience, physical capacity, and time constraints that impact negatively the overall productivity. Similar patterns have been observed in other contexts, such as in Zimbabwe, where the involvement of children in agricultural activities has been shown to reduce productivity, as it often interferes with their education and development [40]. In Tataouine, 86% of goat farmers are primarily engaged in livestock farming, while 14% combine it with other activities. Family labor is central in herd management, with women comprising 49% of milk processors and playing crucial roles in dairy activities [27].

Technical training is another critical area requiring attention. Results showed that only 16% of breeders in Tataouine have received technical training which is significantly lower than in northern Tunisia, where training opportunities are more accessible [27]. Moreover, unlike regions such as Pakistan’s Chakwal District, where breeders have access to public training on modern livestock practices [32], Tataouine lacks such programs. This limits farmers’ ability to adopt improved techniques for herd management, reproductive practices, and animal health. Expanding agricultural extension services in Tataouine is essential to address this disparity.

Herd Characteristics and Reproductive Performances

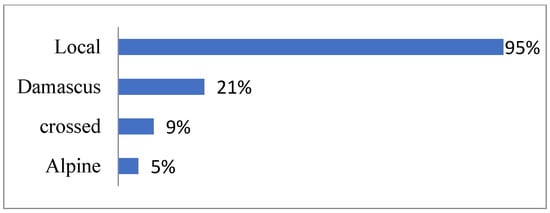

The average herd size in Tataouine is 132 goats represented predominantly by local Arbi breeds (95%), well-adapted to local conditions (Figure 3). These breeds, while resilient, exhibit low productivity, a trend also observed in southern Tunisia, Jordan, and Zimbabwe [27,29,40]. Furthermore, results showed that production systems remain mostly extensive [41].

Figure 3.

Distribution of goat farms by reared goat breeds.

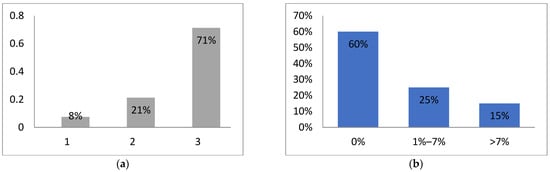

Reproductive performances vary significantly among herds (Figure 4). In fact, fertility rates are notably high, with 71% of herds achieving 100%, 21% falling within the 80–100% range, and 8% reporting rates as low as 50–80%. Prolificacy, however, shows more mixed results: 60% of herds maintain a 100% rate, 34% achieve rates between 100–150%, and only 10% exceed 150%. Better reproductive management practices, such as selective breeding and enhanced herd management techniques could optimize reproductive performances in similar contexts [14]. Abortion rates also vary, with 60% of herds experiencing no case of abortions, 25% reporting rates between 1–7%, and 15% exceeding 7%. High abortion rates are often linked to poor nutrition, diseases, or stress caused by water scarcity. Addressing these issues through improved feeding, vaccination, and better shelter design could significantly reduce losses.

Figure 4.

Distribution of goat herds according to their fertility rate (a) and abortion rate (b).

Feed and Water Management

Goat farms in Tataouine primarily rely on barley (98%) and local agricultural residues to feed their flocks (Figure 5). However, modern feed management practices, such as fattening, are poorly adopted, with only 16% of farmers using this method to enhance profitability. The limited adoption of fattening practices remains a significant barrier to improve profitability in goat farming [42]. Pre-weaning mortality represents another challenge, with an average rate of 2% but reaching up to 30% in some herds. This variability underscores the need for better neonatal care practices, such as colostrum feeding and disease prevention. In addition, water scarcity remains a critical issue for goat farmers in Tataouine, with herds grazing for an average of 6.6 h per day to meet their fodder and water needs. Similar challenges are observed in arid regions like Jordan and Pakistan, where herders must frequently move their herds to access water [32,43].

Figure 5.

Different feed types used for goat herds.

In the study area, approximately 55% of surveyed farms rely on water wells, while 45% depend on water trucks, with the latter incurring an annual cost of around TND 2600 per farm. Water scarcity significantly impacts herd management [43,44,45], as limited access to reliable water sources disrupts livestock health and productivity.

Addressing these challenges particularly through improved water infrastructure and better reproductive practices could substantially enhance herd productivity and farm profitability. Additionally, collaborative water management strategies, such as community-based water harvesting systems or shared irrigation networks, could mitigate water scarcity issues and improve long-term resilience [45,46].

Dairy Production and Product Upgrading

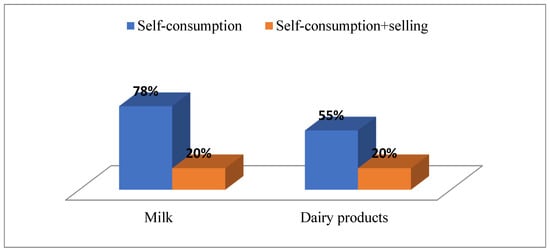

Goat milk production is a vital component of livestock farming in Tataouine, with 97% of farmers practicing milking and 79% processing milk into by-products such as cheese, and butter. However, 78% of the produced milk is intended for self-consumption, and only 22% of farmers are engaging in milk commercialization (Figure 6). The generated income from milk sales is modest, averaging TND 9 per day for those selling 6 L at TND 1.5 per liter.

Figure 6.

Destination of goat milk and dairy products.

Initiatives like Women Agricultural Development Groups, such as Elamal in Guermasa and Elezdihar in KsarHdada, demonstrate the potential of women-led dairy processing. These groups, supported by the CRDA manage the entire production chain, from milking to selling products like milk (TND 2 per liter), butter (TND 50 per kg), and ricotta (TND 15 per kg). Notably, while individual farmers sell milk at TND 1.5 per liter, these women-led groups achieve a higher price of TND2 per liter, reflecting an added value through processing and marketing efforts.

Despite these achievements, 55% of the processed dairy products are consumed within households, and only 20% are marketed, revealing untapped potential for growth. However, the lack of formal marketing channels and organized markets in Tataouine remains a major obstacle to increasing profitability. Establishing milk collection centers and farmer cooperatives could address these barriers by improving market access and enabling the adoption of modern processing techniques, particularly in a growing market for artisanal goods like goat cheese [47,48].

Economic Viability

The average annual income of a goat farmer in Tataouine is TND 5264, and varies between TND 56,000 and TND 0, with an average herd of 132 goats. Several factors undermine profitability, including high feed and veterinary costs, transportation expenses, and low productivity, with a production cost of TND 155 per head. The cost of veterinary consultations varies, with additional expenses including vaccines, antiparasitic treatments, a filing fee of TND5 per small ruminant, and an insecticide treatment cost of TND0.40 per animal. The lack of subsidized veterinary services exacerbates this financial burden, particularly for larger herds [49]. Moreover, transport costs ofTND5 on average/farm pose a significant challenge for farmers in Tataouine, as they must frequently transport water, feed, and animals over long distances. Droughts significantly increase production costs.

Low productivity, driven by slow herd growth and high pre-weaning mortality, limits income generation for goat farmers in Tataouine. The absence of systematic breeding programs further reduces reproductive efficiency, impacting herd productivity and income. These challenges are not unique to the region; for instance, in Zimbabwe, high mortality rates among young stock have been shown to significantly hinder herd growth and sales, highlighting the broader implications of such issues in arid and resource-limited settings [40]. Addressing these barriers through improved breeding strategies and herd management could enhance productivity and income potential.

Marketing challenges further limit profitability, particularly due to the lack of formal distribution channels, which restricts farmers’ ability to sell meat, milk and dairy products at competitive prices. Similar issues have been observed in Pakistan, where informal markets hinder farmers’ access to fair pricing [32]. To address these challenges, diversifying income sources processed dairy products or agroforestry could improve this livestock activity resilience. Additionally, farmer cooperatives could play a key role in reducing costs and enhancing bargaining power through collective sales and shared transportation [50]. Furthermore, expanding outreach programs and feed resources subsidies, especially during critical seasonal periods, could reduce costs for smallholders and enhance herd health, ultimately improving the profitability and sustainability of goat farming in Tataouine.

Interestingly, the average income for farmers practicing fattening (TND 5534.62) is higher than that for those who do not engage in fattening (TND 5046.72). To assess whether this difference is statistically significant, a t-test for independent samples was conducted. The results of the Student’s t-test (t = 0.41, p = 0.68) show that the income difference between the two groups is not statistically significant. This suggests that while fattening practices may increase income, other factors, such as feed costs, herd management, and market access, may play more significant roles in determining overall profitability [51]. The limited adoption of fattening practices and the lack of formal distribution channels for fattened animals may explain why fattening has not yet shown a strong impact on income across a larger population of farmers.

3.1.3. Processing

Butchers Profile and Processing Activities

Butchers in Tataouine are predominantly elderly men, with an average age of 53.77 ± 16.10 years’ old. Over half of them (54%) are over 50 years old, reflecting an aging workforce in the sector. Their experience is substantial, with 62% having more than 20 years in the trade. However, processing practices remain underdeveloped, as only 15% of butchers offer processed products, mainly on demand for high-end customers. This limited value addition highlights a significant gap in the meat value chain.

The low processing capacity in Tataouine is constrained by traditional methods and limited consumer demand for processed products. Butchers face challenges in accessing modern equipment, which restricts their ability to diversify offerings and capture higher market segments. This trend is consistent with observations in other Tunisian governorate, such as Sidi Bouzid and Zaghouan, where traditional butchers rarely diversify into processed products, and in Al-Ruwaished, Jordan, where processing is largely limited to restaurants and hotels [29,30,52]. These examples underscore the larger challenges faced by traditional butchers in expanding their product offerings.

Robust processing capabilities are essential for capturing higher margins along the value chain, as emphasized by Humphrey and Oetero [53]. However, in Tataouine, this potential remains largely untapped, with processing practices failing to move beyond niche markets. Addressing these barriers could involve investing in modern equipment, promoting consumer awareness of processed products, and fostering partnerships with local businesses to expand market access.

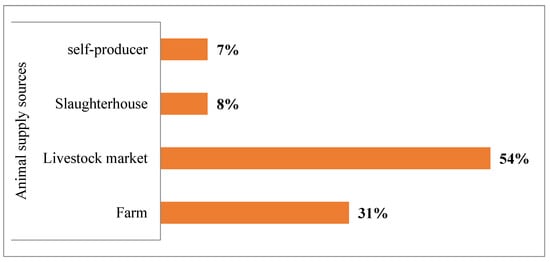

Sources of Supply and Slaughter

Butchers in Tataouine primarily source their animals from markets (54%) and local farms (31%), with only 8% directly supplied by slaughterhouses and 7% from their own farms (Figure 7). However, many butchers who purchase from slaughterhouses rely on intermediaries, particularly maquignons (intermediaries), which increases costs. For instance, a 10–12 kg goat purchased from a maquignon costs TND 180, compared to the TND 150 paid by the maquignon to the farmer. This markup reflects the logistical and market coordination provided by maquignons but also places a financial burden on butchers.

Figure 7.

Animal supply sources of goat meat for butchers.

The selection of animals is based on strict criteria, including health status (100%), price (100%), and fattening status (92%). Butchers prioritize health and fattening status to ensure meat quality, but their reliance on maquignons inflates costs and reduces profit margins [27].

Regarding slaughter practices, 54% of butchers prefer to use approved slaughterhouses where a veterinarian conducts post-mortem inspections, ensuring meat safety. However, 46% of butchers slaughter animals directly in their shops, often under informal conditions. This poses significant health risks, such as bacterial contamination, zoonotic disease transmission, improper waste disposal, and exposure to chemical residues [54]. These informal practices, including the absence of veterinary oversight and the use of non-compliant sites such as garages or streets, not only compromise meat safety but also highlight the insufficient number of modern slaughterhouses and the lack of sanitary oversight in rural areas like Tataouine.

3.1.4. Marketing

Market Dynamics and Selling Prices

Goat meat prices in Tataouine range between TND 22 and 28 per kilogram, with an average of TND 24.62 in 2022. This price range aligns with trends observed in Zaghouan, where consumer demand for low-fat, high-quality meat drives market dynamics [30]. Price variations are influenced by meat quality and target customers, with 77% of butchers catering to local clients, 15% serving large stores, and 8% focusing on upscale clientele such as restaurants. Studies highlight the importance of understanding consumer preferences, shaped by cultural and economic factors, to design effective marketing strategies [55].

Maquignons, play a significant role in the marketing of live animals. Among farmers, 42% sell directly on the farm, with 70% of these transactions involving maquignons. In contrast, 58% prefer selling at local markets, where 46% report that maquignons purchase 70% of their animals. These intermediaries resell animals to butchers or slaughterhouses at higher prices, adding costs along the value chain. The reliance on intermediaries in Tataouine reflects structural inefficiencies. Unlike in regions such as Zimbabwe, where collective marketing systems connect farmers directly to processors [40]. The absence of modern infrastructure and formal marketing mechanisms limits farmers’ ability to capture more value, while intermediaries dominate transactions, inflating prices for consumers and reducing profitability for farmers [56]. Countries with well-structured goat value chains, such as Nepal, demonstrate how targeted policies can integrate small-scale producers into commercial markets [57]. Applying similar strategies in Tataouine such as improving infrastructure, strengthening connections between herders and markets, and promoting efficient production practices could transform the goat sector into a pillar of the local economy [15]. Enhanced coordination among value chain actors, coupled with incentives for modern infrastructure investments, has the potential to significantly boost the region’s economic.

Economic and Health Challenges

Butchers in Tataouine face numerous challenges, including limited access to modern infrastructure and refrigerated slaughterhouses. In addition, some butchers (90%) are using inappropriate means of transport, which increases the risk of meat contamination. The lack of cold chain facilities significantly affects meat quality and safety. Illegal slaughtering remains widespread, complicating the regulation of the sector and the implementation of health standards [58]. Additionally, taxes imposed on slaughterhouses (TND 0.22 per head of animal andTND5 per carcass) increases the operating costs, especially for small-scale operators. This combination of taxation, lack of modern infrastructure, and informal slaughter practices constitutes a major barrier to profitability and competitiveness for local butchers. These challenges are not unique to Tataouine or Tunisia; in fact, in Zimbabwe, the lack of direct access to approved slaughterhouses results in high costs for producers, while in Jordan, the absence of formal markets in live animals’ selling forces farmers and traders to resort to unregulated sales methods, increasing health risks and reducing transaction transparency [29,40].

The lack of formal market structures in Tataouine creates significant barriers for both producers and butchers, hindering efforts to improve the economic viability and health standards of the meat supply chain.

Opportunities for Improvement

Formalizing the role of intermediaries and establishing direct marketing channels could reduce costs and increase profitability for goat breeders in Tataouine. For example, collective marketing systems, as seen in Zimbabwe, could be adapted to the local context [40]. Second, investing in modern infrastructure, such as refrigerated slaughterhouses and cold chain facilities, would enhance meat quality and safety while reducing health risks [59]. Finally, targeted training programs for butchers on modern processing techniques and food safety standards could help to diversify products and meet the growing demand for high-quality, processed meat.

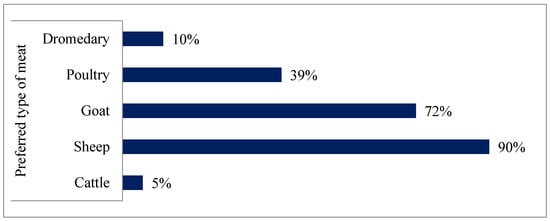

3.1.5. Consumption

In Tataouine, goat meat consumption patterns are deeply influenced by demographic, economic, and cultural factors. The majority of the surveyed consumers are elderly, with 58% over 50 years old, a demographic that tends to favor traditional dietary habits. However, economic constraints play a significant role in shaping food choices. Nearly 40% of households have an income of less than TND 700 per month, limiting their ability to purchase goat meat; in spite of its appreciation by 72% of the population, it remains unaffordable for 69% of non-consumers. Sheep meat is overwhelmingly preferred by 90% of the population (Figure 8), reflecting its cultural significance and integration into local traditions, particularly during religious celebrations like Eid al-Adha.

Figure 8.

Consumers’ meat preferences.

Among those who consume goat meat, 80% do so moderately, with 56% purchasing 1 kg every two weeks and 27% buying more. Despite its cultural appreciation, the average price of TND 25.14/kg makes it less accessible to lower-income groups, even though 64% of current consumers consider it affordable. Similarly, goat milk is consumed by 66% of the population, often provided for free by farmers, highlighting its reliance on self-consumption rather commercialization. However, 62% of non-consumers cite unavailability as the main barrier. Goat cheese consumption is even more limited, at only 14%, due to the lack of production infrastructure and weak local demand. Studies highlight that the absence of formal marketing channels and processing facilities for goat milk and cheese significantly limits their commercialization potential in regions like Tataouine [27].

At the national level, these trends are consistent with broader patterns. Goat meat accounts for only 7.7% of total red meat consumption in Tunisia, largely due to its limited availability compared to sheep meat which dominates the market due to its cultural relevance, Additionally, its higher price influences consumer preferences [60]. Goat milk and cheese face similar commercialization challenges, as informal distribution systems and limited infrastructure hinder their market potential despite their nutritional and economic value.

The strong preference for sheep meat in Tataouine underscores its cultural and symbolic importance, particularly in rural areas where traditions heavily influence dietary habits. However, the limited adoption of goat products, despite their cultural appreciation, reveals a missed opportunity for enhancing dietary diversity and supporting rural economies. While goat meat and milk are valued in southern Tunisia for their nutritional quality and flavor, economic and structural barriers restrict their wider adoption.

Addressing these challenges needs targeted interventions to improve the commercialization and accessibility of goat products. Developing infrastructure for goat cheese production, enhancing distribution networks for goat milk, and promoting added-value goat meat products could unlock significant economic opportunities. Creating cooperatives and marketing associations could help connect producers with formal markets, increasing the visibility and appeal of goat products. These efforts would not only benefit smallholder farmers in Tataouine but also contribute to national food security by diversifying available protein sources. Additionally, promoting goat products through cultural and regional branding, such as certifications of origin, could enhance their appeal in both local and export markets [60]. By addressing economic and structural barriers, Tataouine and similar regions can tap into the untapped potential of goat products, fostering both economic growth and dietary diversity.

3.1.6. Interaction Between Breeders, Butchers, and Consumers in the Tataouine Goat Value Chain

The dynamics of the goat value chain in Tataouine reveal intricate interactions between farmers, butchers, and consumers, which significantly influence the goat meat demand, supply, and profitability. A high correlation coefficient of 0.947 (p < 0.001) between consumer preferences and the meat sold by butchers demonstrates a strong alignment between consumer expectations and butcher supply (Table 1). In fact, butchers adapt their offerings to precisely match local preferences, particularly for goat meat. This adaptability ensures that consumer preferences directly shape the type and quality of the available meat, sustaining demand and maintaining market relevance [24,55].

Table 1.

Correlation between variables from goat value chain actors.

However, farmers face significant challenges in meeting the criteria set by butchers. Only 16% of farmers in Tataouine practice animal fattening, while 92% of butchers consider fattening as an essential criterion for purchasing livestock. The perfect negative correlation (−1, p < 0.001) between farmer practices and butcher criteria highlights a major misalignment, which limits profitability for farmers and increases costs for butchers. Fattened animals yield higher-quality cuts and command better prices, but the lack of fattening practices among farmers reduces their bargaining power and constrains the added value potential of their products. This discrepancy underscores a critical gap in the value chain, where farmers’ limited capacity to invest in fattening undermines overall profitability, a pattern observed in other rural goat farming systems across Tunisia [60].

Moreover, an analysis of the relationship between farmers’ education levels and their engagement in fattening practices reveals a statistically significant correlation (χ2 = 15.8238, p = 0.001). Farmers with higher education levels are more likely to engage in fattening. Among those with university education (8% of the sample), 67% practice fattening, while 33% do not. This suggests that better-educated farmers may have greater access to technical knowledge, financial resources, or networks that enable them to adopt fattening practices more effectively. Conversely, farmers with lower education levels, particularly those with only primary education or less, are significantly less likely to engage in fattening, further contributing to the observed misalignment between farmer supply and butcher demand. This analysis highlights education as a key driver of fattening adoption, suggesting that policies aimed at improving farmer training and knowledge-sharing could enhance productivity and profitability in the Tataouine goat value chain.

Additionally, a Pearson correlation of 0.80 between herd size and goat farming revenue reveals a strong positive relationship, indicating that farmers with larger herds tend to generate higher revenues. This is consistent with expectations, as larger herds increase the volume of milk and meat production, directly boosting farmers’ incomes. This correlation suggests that farmers with larger herds may have better access to resources, markets, and economies of scale, all of which contribute to enhanced profitability. Therefore, supporting small-scale farmers to expand their herds, perhaps through financial incentives or better access to animal husbandry resources, could increase their productivity and income potential.

The correlation between the price at which goat meat is sold by farmers and the price accepted by consumers is moderate (0.37, p < 0.05), suggesting that while consumers are price-sensitive, other factors such as quality and freshness play a decisive role in their purchasing decisions. Efforts to improve meat quality and handling practices at all levels of the chain could better align farmer revenues with consumer expectations. For instance, improved cold chain management, enhanced hygiene standards, and better animal selection criteria could increase consumer willingness to pay higher prices. This finding reflects trends in neighboring regions, where investments in cold chain logistics and quality assurance have successfully enhanced consumer trust and willingness to pay for premium meat products [61].

The perfect positive correlation (1, p < 0.001) between animal supply and animal sales indicates the efficiency of existing distribution networks in matching supply with demand. However, the over-reliance on traditional intermediaries, such as maquignons, often distorts pricing mechanisms and reduces direct profits for farmers. These intermediaries can impose disproportionate markups, undermining farmer incomes and creating inefficiencies in the value chain. Strengthening direct farmer–buyer relationships could bypass intermediaries and improve value chain transparency, as demonstrated in other regions such as Kairouan [30,62].

Although prices charged by butchers and prices accepted by consumers are linked, there is a significant opportunity for improvement in profitability along the value chain. Training programs for farmers on fattening practices, coupled with incentives for butchers to establish formal agreements with producers, could bridge the existing gaps and create a more balanced value chain. Similar approaches in other Tunisian governorates such as Siliana and Sidi Bouzid have demonstrated that fostering direct partnerships between farmers and butchers can enhance transparency, reduce costs, and improve product quality [60]. Additionally, cooperative models could strengthen these interactions by ensuring fair pricing and equitable profit-sharing among value chain actors.

Educating consumers on the nutritional benefits and quality of goat meat could further stimulate demand and justify higher prices. Public awareness campaigns have proven effective in increasing the acceptance of goat products in rural and peri-urban areas of Tunisia, particularly when combined with branding strategies that highlight local and traditional production methods [63]. In Tataouine, promoting the unique qualities of goat meat and milk products through regional branding could enhance their market appeal and competitiveness.

3.1.7. Governance of the Goat Value Chain in Tataouine

Governance in value chains refers to the mechanisms through which actors influence one another to ensure organized and efficient interactions [64]. In Tataouine, weak coordination among farmers, butchers, and consumers undermines the goat value chain’s efficiency, limiting small producers’ integration into structured markets. This disorganization, as explained by the theory of value chain governance (VGC), disrupts the equitable distribution of resources and gains, often marginalizing certain actors [65]. Effective governance requires organizing activities to ensure a functional division of labor, with clear resource allocations and participation conditions. A key governance challenge is the misalignment between farmers and butchers. This gap reflects the absence of collaborative frameworks to align production with market demand. Formal agreements or contracts could improve synchronization and mutual benefits, as demonstrated by successful models in other regions [27,66].

Farmers, who rely essentially on traditional practices, face limited market access. Approximately 70% of farm-level sales and local market transactions are conducted through intermediaries, such as maquignons. While intermediaries facilitate trade, their dominance reduces farmers’ direct market access and profit shares. Strengthening farmers’ trading power through cooperatives could help them capture greater value and negotiate better terms. Studies highlight that cooperatives in southern Tunisia have empowered farmers by improving market access and providing collective resources like veterinary care and training [52,67].

Butchers, critical to processing and distribution, suffer from inadequate infrastructure and only 54% of them use approved slaughterhouses, while 46% rely on informal practices, increasing health risks and undermining consumer trust. This situation confirms findings in Zoghmar, where the lack of modern slaughterhouses inhibits value addition [52]. Developing slaughterhouses with refrigeration systems could improve meat quality and reduce losses. Transparent pricing mechanisms and enforced health regulations are also essential to enhance governance and equity.

To address these gaps, agricultural cooperatives could improve coordination and market access, promoting equitable profit distribution [66]. Cooperatives could also provide essential services like veterinary care and training, while enhancing farmers’ bargaining power. Upgrading processing infrastructure, such as establishing health-compliant slaughterhouses, is crucial for competitiveness. Training programs on value addition, like fattening or dairy processing, could further boost profitability and diversify income sources. Public policies incentivizing such initiatives, alongside subsidies for modern infrastructure, could accelerate this transformation.

By integrating structured governance, supported by public policies and training, the goat value chain in Tataouine could become more resilient to economic challenges while improving producer profitability and consumer satisfaction. Participatory platforms to foster dialogue among farmers, butchers, and consumers could enhance collaboration and mutual understanding across the value chain [68].

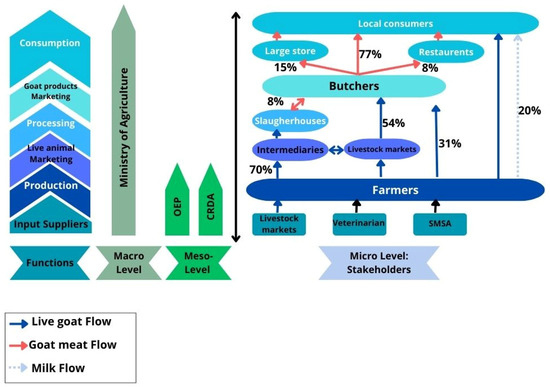

3.1.8. Mapping Value Flows in the Goat Value Chain in Tataouine

The mapping of value flows in Tataouine’s goat value chain (Figure 9) provides a comprehensive overview of the activities and stakeholders involved in production, processing, and marketing. Rather than categorizing activities based on their direct contribution to value creation, the map illustrates the organization of different stages within the chain and the interactions among actors.

Figure 9.

Value chain mapping of goat production in Tataouine.

Certain practices play a crucial role in enhancing the quality and marketability of goat meat. Animal feeding, breed selection, and fattening are essential for meeting consumer preferences for tender, low-fat, and fresh products [30]. Similarly, processing and marketing ensure that products reach the market in optimal condition and attract consumer interest.

Other activities, while essential to the functioning of the chain, are more operational in nature. Transportation, logistics, storage, and weighing facilitate the movement of animals and products but do not directly improve product quality. However, optimizing these processes can enhance efficiency and reduce costs.

The map also highlights the significant role of consumers, whose demand for fresh and affordable products influences farmer and butcher practices. Despite this, a gap remains between production and market expectations. While only 16% of farmers engage in fattening, 92% of butchers consider it a key factor in purchasing decisions. This mismatch limits farmers’ ability to maximize product value and increases costs for butchers. Reducing the role of intermediaries who often drive-up prices and lower farmers’ direct profits can improve overall profitability [60]. Strengthening direct farmer–buyer relationships can help bridge this gap and improve the efficiency of the value chain.

Investments in climate-resilient infrastructure, such as modernized slaughterhouses with refrigeration systems, can significantly reduce spoilage and enhance meat quality [69]. Additionally, improved coordination among stakeholders through cooperatives or producer groups can promote resource sharing and increase bargaining power [65].

3.2. Impact of Climate Change on the Goat Value Chain in Tataouine

Climate change poses significant challenges to the goat value chain in Tataouine, affecting production, processing, and marketing. The majority of the surveyed farmers (97.2%) report increased temperatures and prolonged droughts, which severely disrupt pasture availability and reduce animal production yields, in concordance with the results of Shah et al. [70]. Water scarcity, exacerbated by declining rainfall (reported by 80% of farmers), and rising water supply costs further strain the profitability of goat farms. These conditions negatively impact the quality of meat and milk, particularly during periods of intense heat and drought. Additionally, 93.8% of farmers observe degraded pastures, making it increasingly difficult to sustain goat production [71,72]. The findings of Rjili and Jaouad [64] underscore these challenges, projecting a 30% decline in rainfall and a 2.1 °C rise in temperatures by 2050 for arid regions like Tataouine. These climatic shifts exacerbate rangeland degradation, threatening the primary source of fodder for goats and forcing farmers to adopt adaptive measures. Increased aridity not only reduces natural forage availability but also heightens reliance on costly supplementary feeds, further straining farmers’ financial resources [27].

3.2.1. Adaptation Strategies in Production

To mitigate the effects of extreme heat, all farmers in Tataouine implement protective measures during the summer. A common practice is constructing shaded areas near grazing fields or water points to reduce heat stress on animals. This infrastructure is critical for maintaining animal welfare and productivity during harsh weather conditions.

Farmers also adopt several strategies to cope with resource scarcity. Purchasing additional feed is widespread (98%), with some increasing feed quantities during heat waves to reduce grazing time (60%). Many have shifted to supplementing goat diets with crop residues and alternative feeds (54%), a practice proven effective in other arid regions [73]. Transhumance, already common in Tataouine, is being intensified to compensate for local pasture shortages during droughts (40%).

Integrating agriculture and livestock practices, such as cultivating forage crops alongside traditional farming, offers dual benefits. These methods not only provide supplementary feed but also enhance soil fertility and reduce water evaporation, improving resilience to climate variability [69]. Some farmers (45%) also invest in water storage tanks to address immediate water needs and support long-term herd resilience during dry spells. However, 50% of the surveyed goat farmers have resorted to reducing herd sizes to better manage limited resources. While this strategy helps mitigate resource scarcity, it also limits the economic potential of goat farming by reducing the number of animals available for breeding and sale.

3.2.2. Challenges in Processing and Marketing

The impact of prolonged drought extends to the processing link, where irregular goat supplies complicate slaughter planning and increase post-slaughter losses, especially during hot weather [74]. Processing facilities, such as slaughterhouses, are ill-equipped to handle these production fluctuations, leading to higher storage and distribution costs. For instance, the lack of refrigeration and cooling systems in many slaughterhouses (80%) results in significant spoilage during peak heat, reducing the quality and quantity of meat available for sale. Addressing these issues requires investments in modernized, climate-resilient facilities.

3.2.3. Innovative Solutions for Resilience

Farmers in Tataouine are exploring innovative strategies to enhance herd resilience. Introducing drought-resistant breeds (26%) and using artificial insemination (5%) to improve reproductive performance are among the potential solutions. While artificial insemination remains rare, government initiatives could facilitate its adoption. Drought-resistant breeds, combined with improved breeding practices, offer a sustainable pathway to maintain productivity under arid conditions.

Diversification of agricultural activities, such as cultivating drought-resistant forage crops or adopting agroforestry practices, has also been identified as a promising adaptation strategy (54%). These practices, successfully implemented in other regions facing similar climatic challenges [75], could provide dual benefits: increasing feed availability for goats while enhancing soil fertility and water retention in arid areas.

3.3. SWOT Analysis of the Goat Value Chain in Tataouine, Tunisia

For the Tataouine goat value chain, a SWOT analysis reveals critical insights into its current state and future potential (Table 2).

Table 2.

SWOT analysis of the goat value chain in Tataouine, Tunisia.

To address the weaknesses and threats identified in the SWOT analysis, a multi-faceted approach is essential. First, modernizing livestock practices is critical. This includes promoting fattening techniques to meet butchers’ expectations and improve meat quality, as well as training farmers in modern reproductive and dairy production techniques to increase yields. Second, developing marketing infrastructure, such as establishing agricultural cooperatives and structured local markets, can centralize supply and sales, reducing reliance on intermediaries and facilitating the sale of milk, meat, and dairy products like cheese, butter, and lben. Third, improving access to resources and services is vital. Investments in modern, climate-resilient slaughterhouses and strengthened veterinary services can reduce post-slaughter losses, improve meat quality, and enhance animal health. Fourth, addressing climate challenges through the promotion of drought-resistant goat breeds, transhumance practices, and the cultivation of drought-resistant forage crops can optimize pasture use and reduce dependence on barley. Fifth, enhancing the value of local dairy products by supporting women’s groups (e.g., Elamal and Elezdihar) to develop local cheese brands and improving access to urban markets for artisanal dairy products can capitalize on growing demand. Finally, reducing dependence on intermediaries by facilitating direct sales between farmers and butchers and promoting innovative financing models, such as microcredit, can increase farmers’ profit margins and enable investments in quality inputs and infrastructure. These recommendations, when implemented collectively, can strengthen the Tataouine goat value chain, making it more resilient, profitable, and competitive.

4. Conclusions and Recommendations

The goat value chain in Tataouine presents a striking paradox: significant potential is constrained by systemic challenges. This sector, deeply embedded in local culture and livelihoods, is hindered by traditional practices, fragmented markets, and climate vulnerabilities. While indigenous breeds exhibit remarkable resilience and women play a pivotal role in dairy processing, the industry struggles with inefficient production methods, inadequate infrastructure, and limited value addition.

Three key challenges emerge as critical bottlenecks. First, production constraints stemming from traditional husbandry practices and climate pressures limit productivity and profitability. Second, market inefficiencies, driven by poor coordination and inadequate processing infrastructure, restrict access to higher-value markets. Third, institutional gaps in policy support and stakeholder collaboration hinder the sector’s ability to scale and modernize.

To address these challenges and unlock the sector’s potential, an integrated set of interventions is required. Production modernization should prioritize training programs on improved breeding, fattening techniques, and herd health management to enhance productivity. Climate-smart practices, such as drought-resistant fodder cultivation and optimized water management, must be promoted to mitigate environmental risks. Expanding veterinary services and ensuring access to high-quality inputs through public-private partnerships will further strengthen the production base.

Value chain development requires investments in modern processing facilities that meet hygiene and safety standards for both meat and dairy products. Encouraging the establishment of women-led cooperatives for artisanal dairy production, coupled with quality certification schemes, can enhance product differentiation and consumer trust. A regional branding strategy, such as “Tataouine Goat Cheese”, can further position local products in niche markets, increasing their competitiveness.

Market system strengthening is essential to improve access and ensure fairer pricing mechanisms for producers. The formation of producer organizations will enhance bargaining power and facilitate coordinated market engagement. Digital platforms connecting farmers with buyers and input suppliers can streamline transactions and reduce inefficiencies. Additionally, exploring export opportunities through alignment with regional trade agreements can further expand market reach.

Creating an enabling environment is crucial for the sector’s long-term sustainability. Targeted subsidies for infrastructure improvements and climate adaptation measures should be advocated to support producers. Establishing multi-stakeholder platforms will enhance coordination between policymakers, private sector actors, and farmers, fostering a more integrated development approach. Furthermore, implementing monitoring systems to track the impact of interventions will ensure continuous improvement and adaptation of strategies.

Achieving sustainable transformation in the Tataouine goat sector requires a phased and strategic approach. The process should begin with production improvements to establish a consistent and high-quality supply base, followed by processing upgrades to enhance value addition, and culminating in market expansion initiatives to secure demand and optimize profitability. This structured pathway, supported by strong governance mechanisms, will create a virtuous cycle of quality improvement and market access.

Realizing this vision demands collective action across all levels from farmers adopting improved practices to policymakers creating supportive regulatory frameworks. With strategic investments and sustained commitment, Tataouine’s goat sector can evolve into a model of sustainable livestock production, driving economic resilience and improved livelihoods across southern Tunisia.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/su17083669/s1, Files S1–S3: Full surveys used in data collection; Table S1: Table resume complete numerical results.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.D., A.M.-B. and M.J.; methodology, R.D., A.M.-B. and F.A.; data collection, R.D.; validation, R.D., A.M.-B., F.A. and M.J.; formal analysis, R.D., A.M.-B. and F.A.; data curation, R.D.; writing—original draft preparation, R.D.; writing—review and editing, F.A., A.M.-B. and M.J.; supervision, R.D., A.M.-B., F.A. and M.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical approval was not required for this study, as it involved non-interventional research (surveys and questionnaires) conducted in accordance with ethical standards. However, all procedures involving human participants were conducted following the Declaration of Helsinki (1975, revised in 2013). The study was carried out with the ethical standards of the Arid Region Institute (IRA Medenine).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our sincere acknowledgement to the staff working for the Tunisian Ministry of Agriculture and its institutions in Tataouine. Their support, cooperation, and provision of necessary resources were instrumental in the successful completion of this study. Their valuable input has greatly enriched this study and enhanced its credibility. We would also like to acknowledge the contributions of all the participants and stakeholders involved in this research. Their willingness to share their knowledge, experiences, and perspectives was essential in understanding the complexities of the goat value chain in Tataouine governerate.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| OEP | Livestock and Pasture Office |

| CRDA | Regional Agriculture Development Commissariat |

| ODS | Southern Office |

References

- Najari, S. Caractérisation Zootechnique et Génétique d’une Population Caprine. Cas de la Population Caprine Locale des Régions Arides Tunisiennes. Ph.D. Thesis, Institut National Agronomique, Tunis, Tunisia, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Atoui, A.; Laaroussi, A.; Abdennebi, M.; Ben Salem, F.; Najari, S. Impacts of food scarcity and irregularities under arid conditions on the body reserves and production of local goat population in the southern of Tunisia. J. OASIS Agric. Sustain. Dev. 2022, 4, 24–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Salem, H.B. Mutations des systèmes alimentaires des ovins en Tunisie et place des ressources alternatives. Options Méd. Sér. A Méd. Sémin. 2011, 97, 29–39. [Google Scholar]

- Alary, V.; Moulin, C.-H.; Lasseur, J.; Aboul-Naga, A.; Sraïri, M.T. The dynamic of crop-livestock systems in the Mediterranean and future prospective at local level: A comparative analysis for South and North Mediterranean systems. Livest. Sci. 2019, 224, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibidhi, R.; Frija, A.; Jaouad, M.; Ben Salem, H. Typology analysis of sheep production, feeding systems and farmers strategies for livestock watering in Tunisia. Small Rumin. Res. 2018, 160, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Office de Développement du Sud. Tataouineen Chiffre 2022; Office de Développement du Sud: Medenine, Tunisia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Observatoire National de l’Agriculture. Annuairestatistique 2022; Observatoire National de l’Agriculture: Tunis, Tunisia, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Najjar, D.; Baruah, B. “Even the goats feel the heat”: Gender, livestock rearing, rangeland cultivation, and climate change adaptation in Tunisia. Clim. Dev. 2023, 16, 526–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennis, E.; Bailey, D.V.; Gillies, R. An initial assessment of the opportunities and challenges associated with expanding Nepal’s goat market. In Research Brief. Feed the Future Innovation Lab; Colorado State University: Fort Collins, CO, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Peacock, C. Goats—A pathway out of poverty. Small Rumin. Res. 2005, 60, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ILRI. ILRI 2021 Financial Statements; ILRI: Nairobi, Kenya, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Jaouad, M.; Sghaier, M.; Bechir, R.; Khorchani, T. Au-delà de la sécuritéalimentaire et nutritionnelle: Quelle importance de l’élevage pastoral dans les filièresd’élevage dans le Sud-Est Tunisien? Eur. J. Soc. Law 2022, 54, 112–120. Available online: https://openurl.ebsco.com/contentitem/gcd:154308709?sid=ebsco:plink:crawler&id=ebsco:gcd:154308709 (accessed on 11 December 2024).

- Najari, S.; Gaddour, A.; Ouni, M.; Abdennabi, M.; Ben Hamouda, M. Non genetic factors affecting local kids growth curve under pastoral mode in Tunisian arid region. J. Biol. Sci. 2007, 7, 1005–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atoui, A.; Carabaño, M.J.; Najari, S. Evaluation of a local goat population for fertility traits aiming at the improvement of its economic sustainability through genetic selection. Span. J. Agric. Res. 2018, 16, e0404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sala, S.M. An Analysis of the Factors Influencing Participation of Pastoralists in Commercial Fodder Value Chain for Livelihood Resilience in Isiolo County. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Nairobi, Nairobi, Kenya, 2019. Available online: http://erepository.uonbi.ac.ke/handle/11295/107167 (accessed on 11 December 2024).

- Duguma, A.L.; Debsu, J.K. Determinants of livestock production development of smallholder farmers’. J. Appl. Sci. Environ. Manag. 2019, 23, 1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Climate Data. Climat Águas de Lindóia. Available online: https://fr.climate-data.org/afrique/tunisie/tataouine/tataouine-27575/ (accessed on 24 November 2024).

- ODS. Tataouine en Chiffre 2021; Office de Sud: Medenine, Tunisia, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. The Tunisian Arbi Goat—A Treasure of Diversity [Success Story]. Domestic Animal Diversity Information System (DAD-IS). 2019. Available online: https://www.fao.org/dad-is/success-story/detail/en/c/1641060/ (accessed on 26 March 2025).

- Kilelu, C.; Klerkx, L.; Omore, A.; Baltenweck, I.; Leeuwis, C.; Githinji, J. Value Chain Upgrading and the Inclusion of Smallholders in Markets: Reflections on Contributions of Multi-Stakeholder Processes in Dairy Development in Tanzania. Eur. J. Dev. Res. 2017, 29, 1102–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emet, G. SWOT analysis: A theoretical review. J. Int. Soc. Res. 2017, 10, 994–1006. [Google Scholar]

- Istaitih, Y.; Yelboğa, M.N.M. SWOT analysis of small ruminants production in West Bank-Palestine. Mediterr. Agric. Sci. 2018, 31, 255–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellin, J.; Meijer, M. Guidelines for Value Chain Analysis; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO): Rome, Italy, 2006; Available online: https://www.fao.org/fileadmin/templates/esa/LISFAME/Documents/Ecuador/value_chain_methodology_EN.pdf (accessed on 26 March 2025).

- Salla, D.A. Review of the Livestock/Meat and Dairy Value Chains and the Policies Influencing Them in West Africa; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO): Rome, Italy, 2017; Available online: https://openknowledge.fao.org/handle/20.500.14283/i5275en (accessed on 13 December 2024).

- Gaddour, A.; Kraiem, A.; Mohamed, A. Goat breeding in Southern Tunisia. J. Oasis Agric. Sustain. Dev. 2022, 4, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalthoum, S.; Lachtar, M.; Ben Smida, B.; Jouini, K.; Mhateli, K.; Dali, Y.; Bouajila, M. La mobilité animale dans le gouvernorat de Tataouine. Bull. Zoosanit. 2021, 23, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Chniter, M.; Dhaoui, A.; Houidheg, A.; Atigui, M.; Hammadi, M. Socio-economic aspects and farming practices of goats in Southern Tunisia. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2024, 56, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhraief, M.; Bedhiaf, S.; Dhehibi, B.; Oueslati, M.; Jebali, O.; Salah, Y. Factors affecting the adoption of innovative technologies by livestock farmers in arid area of Tunisia. FARA Res. Rep. 2018, 3, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awad, R.; Titi, H.; Mohamed-Brahmi, A.; Jaouad, M.; Gasmi-Boubaker, A. Small ruminant value chain in Al-Ruwaished District, Jordan. Reg. Sustain. 2023, 4, 416–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khemiri, H.; Darej, C.; Attia, K.; M’Hamdi, N.; Sghir, C.; Moujahed, N. Evaluation of the sustainability of goat farms in the north-western region of Tunisia. Malays. Anim. Husb. J. 2019, 1, 54–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, L.H.; Latham, S.M.; Woolhouse, M.E. Risk factors for human disease emergence. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. London. Ser. B Biol. Sci. 2001, 356, 983–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, H.; Akhtar, W.; Akmal, N.; Hassan, T.; Farooq, W.; Muhammad, I.; Kassie, G.; Rischkowsky, B.; Razzaq, A. Rapid Assessment of the Small Ruminant Value Chain in Chakwal District, Pakistan; ICARDA: Islamabad, Pakistan, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Rossi, G.; De Balogh, K.; Di Nardo, A. Disease prevention in livestock trade: The role of veterinary services. Rev. Sci. Tech. 2017, 36, 267–276. [Google Scholar]

- Chihi, A. Dynamics of livestock systems in Tunisia: Challenges and opportunities. Tunis. J. Anim. Sci. 2006, 12, 45–58. [Google Scholar]

- Gereffi, G. The organization of buyer-driven global commodity chains: How U.S. retailers shape overseas production networks. In Commodity Chains and Global Capitalism; Gereffi, G., Korzeniewicz, M., Eds.; Praeger: Westport, CT, USA, 1994; pp. 95–122. [Google Scholar]

- Pietrobelli, C.; Saliola, F. Power relationships along the value chain: Multinational firms, global buyers and performance of local suppliers. Camb. J. Econ. 2008, 32, 947–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Initiative pour la Promotion des Filières Agricoles (IPFA). Offreet Demande de Conseils et Produits Financiers dans le Secteur Agricole; GIZ: Tunis, Tunisia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Keneni, C. Maximize goat farm production value chain and profitable potential East Ethiopia, at Doba District. J. Livest. Policy 2018, 1, 52. [Google Scholar]

- Awad, R.; Gasmi-Boubaker, A.; Mohamed, J.; Titi, H. Assessing the small ruminant value chain in arid regions: A case study of the North-Eastern Badia Basalt Plateau in Jordan. J. Glob. Innov. Agric. Sci. 2023, 11, 549–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gumindoga, B.; Chikaka, A.T. Evaluating Buhera and Nkayi Goat Value Chains in Agroecological Zone V of Zimbabwe. Int. J. Res. Innov. Appl. Sci. 2024, IX, 425–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaddour, A.; Najari, S.; Abdennebi, M. Spécificité et diversité des systèmes de production caprine et ovine dans les régions arides tunisiennes. In Technology Creation and Transfer in Small Ruminants: Roles of Research, Development Services and Farmer Associations; Chentouf, M., López-Francos, A., Bengoumi, M., Gabiña, D., Eds.; CIHEAM/INRAM/FAO: Zaragoza, Spain, 2014; pp. 477–480. [Google Scholar]

- Hamid, A. Assistance in fattening goat farming business: Diversification strategy and productivity improvement ‘Gus Shor Farm’ Kanugrahan Maduran Lamongan Village. Sahwahita Community Engagem. J. 2024, 1, 79–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Zanat, M.; HA, M.; Tabbaa, M. Production systems of small ruminants in Middle Badia of Jordan. Dirasat Agric. 2005, 32, 205–214. [Google Scholar]

- IMMAP. Mapping of Wheat and Small Ruminants Market Systems in Al-Hasakeh Governorate. 2018. Available online: https://immap.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/Care-NES-Facesheet-Final-9102018.pdf (accessed on 30 November 2024).