Abstract

This innovative study focuses on identifying the primary trends in citizens’ decision-making regarding sustainable and healthy water use and the promotion of tap water options. The primary objective of this study was to investigate whether there was a connection between citizen-consumer choices of tap water versus bottled water and their socio-demographic attributes or environmental awareness and consciousness, which both influence the access to and quality of drinking water. The availability, safety and quality of drinking water is a basic human right and an important public health issue. Water plays a crucial role in terms of increasing geo-political and socio-economic importance. Several researchers have examined the multiple elements influencing customers’ opinions about the quality of water and services, finding that a variety of internal and external factors play a role. To accomplish the study goals, a variety of research methodologies were applied to the use case of Kilkis city, Region of Central Macedonia, Greece. Gaining insight was first facilitated via communication with a focus group of local professionals and policy-makers. Then, a social survey of 407 randomly chosen citizens was conducted to collect the data. The key determinants influencing citizens’ drinking water choices were investigated using multivariate data analysis. Specifically, cluster analysis was employed to group customers exhibiting similar water usage patterns, resulting in the identification of two groups: (a) individuals who favored bottled water and (b) individuals who favored tap water with no filtration. The comparison of the distribution of water consumers between these two clusters, via a Chi-Square test with cross tabulation analysis, showed that customers’ drinking water buying habits were not influenced by their socio-demographic traits. On the other hand, the choice of tap water was found to be positively connected to citizens’ increased level of environmental consciousness. The outcomes of this study can help the stakeholders involved to assist in making improvements to customer service programs for encouraging tap water use, as a more sustainable and healthy water option. Moreover, the population could potentially be motivated to adopt updated technologies for recycling water down the line, moving towards sustainable water resource management.

1. Introduction

Water is possibly one of the most valuable resources in today’s society, with growing significance in socio-economic and geo-political realms [1,2]. Conserving water is crucial for all activities, and for human, animal and ecological health in the context of the One Health approach [3]. Social awareness is increasingly growing regarding the new challenges associated with the sustainability of water resources and their effects or connections to other concerns, such as climate change, food accessibility, wellness or biodiversity [4].

Citizens’ perceptions of water quality and service efficiency are formed by a range of both internal and external elements. A significant contrast in the way consumers view water quality versus their real consumption encounters has been reported so far [5,6]. Understanding how perceptions are shaped and their determinant factors is essential in bridging the gap between perceptions and reality. The way consumers are informed about drinking water and the services provided by suppliers influences their buying habits and preferences for drinking water [7,8].

Public perceptions of water quality and risk can be influenced by a number of factors. Several researchers have examined the determinants influencing users’ perceptions of water quality and their decision-making process regarding water consumption, aiming to comprehend their preferences. Often, these research studies find that consumer perceptions are influenced by a mix of different factors. The public may interpret bad or strange tastes, smells and colors as suggesting health hazards, and the term “unusual” suggests that familiarity with particular water properties will also be important. Specifically, the various key aspects emphasized in studies are water quality [9,10], sensory information [11,12], trust [13] and the perception of risk [14,15], among others. Additionally, the consumer’s education, age and income level seem to have a substantial influence as determining factors and indicators of sustainability [16]. Furthermore, the characteristics within a household also play a role in influencing their purchasing choices [17].

Confidence in water corporations might also be relevant to risk perception, though it is likely that its significance will not become apparent until issues arise. Also, the supply of safe drinking water by water utilities faces challenges from possible disruptions to water. Several water utilities adopt flexible and adaptable strategies to enable the resilient management of water supply sources, which can be facilitated by constructive connections with the community. Moreover, residents’ perceptions of value, satisfaction and loyalty, which impact their overall well-being, are greatly affected by the policies implemented by central and local public services [18,19,20].

Poor or wrong information and socio-spatial disparities about drinking water quality may especially impact relevant public concerns. External information from water businesses, various media and friends can also have an impact on how water quality and potential risks are perceived [9,21]. A lack of or inadequate communication, or even disagreement among professional expert groups including water industries, scientists and regulators, may also contribute to customer discontent or mistrust over drinking water services, quality and risks [22,23].

Consumers drink water from bottles which are usually made of plastic. Certainly, plastic packaging is very convenient for individuals, but is a doubtful option from an environmental point of view. In fact, bottled water brings plastic pollution due to there being too many non-recycled plastic bottles and microscopic plastic fibers, as plastic packaging is frequently released into the environment right after it is utilized, thus increasingly participating in soil and water pollution and endangering environmental and human health and well-being [24,25,26,27]. On the other hand, glass also does not represent a potential sustainable packaging choice due to the significant energy required for bottle manufacturing and its heaviness during transportation. From an economic point of view, if the full cycle of container use—from obtaining the raw material for the production of plastic to the disposal of discarded containers—is followed and compared with the same cycle for glass packaging, then the use of glass may turn out to be less economical. Particularly, the significance of choosing an optimal waste disposal scheme should be noted here. Thus, it is currently urgent to contribute to solving the increasing pollution issues arising from inconvenient consumption behavior by promoting more sustainable options, such the use of tap water.

Moreover, spring water needs to be strategically safeguarded. However, a noticeable expansion in the sale and consumption of bottled drinking water is observed nowadays. A low quality of tap water and a widespread desire for a healthy lifestyle are reported to be among the main causes of these positive dynamics [28]. However, people are becoming used to drinking water in bottles, rather than focusing on the reasons why tap water would be unfit for human health. Since the effects of climate crisis are increasingly being felt directly, it is crucial for the environment that tap water be safe to drink [29]. The potability of tap water should be achieved and promoted in terms of sustainable development. For this purpose, the Member States of the European Union should address the issue of access to clean water via actions to improve access to water for human consumption for all citizens, including the promotion of tap water as an option, i.e., by encouraging a free water supply for human use in public services and buildings and by providing water for free or at a low service charge for customers in restaurants, canteens and catering facilities [30]. The aim is to increase people’s trust in the water provided to them as well as in water supply services to lead to an increase in the consumption of tap water as drinking water, contributing to a decrease in greenhouse gas emissions and plastic waste, as well as having a favorable effect on the environment and climate change mitigation.

Although tap water is preferable due to resource efficiency and environmental concerns and remains inexpensive and safe to drink in many nations, the world’s consumption of bottled water is increasing. In Flanders, for example, a study indicated that the use of bottled water is common, even despite financial and environmental concerns [31]. Other studies have identified perceptions of safety and the taste of tap water as the main deterrents to drinking fluorinated water from the tap, and perceived health concerns significantly predicted the reasons why survey respondents did not drink tap water [32]. In the U.K., the majority of respondents would purchase and drink bottled water after a “do not drink” notice, although up to 44% would still drink the tap water considered to be contaminated [33]. A survey carried out at a large research university to better understand how students behaved in response to perceived water quality in West Virginia, in an area with a history of water quality problems, showed that one-third of the student body mostly drank bottled water at home [34]. It appears that further studies and policy efforts will gain benefits from a strategy that combines all behavioral factors linked to the consumption of different drinking water types. For tap water to be more widely accepted, it is critical to understand the perceptual driving forces that influence drinking decisions [35].

In this context, the primary aim of the current novel research is to identify basic patterns in citizen-consumer’s decisions on water usage according to the information provided, to encourage the more sustainable and healthy option of tap water.

For this purpose, the specific research objectives examined are as follows:

- (a)

- The investigation of the parameters that influence citizens’ drinking water purchasing behavior, in an attempt to categorize them into comparable behavior groups;

- (b)

- The comparison of the distribution of water consumers between the determined clusters, on the basis of their

- socio-demographic patterns;

- environmental/ecological awareness;

- (c)

- The promotion of social participation that is beneficial for sustainable urban growth. Social involvement in urban drinking water quality evaluation and decision-making entails, among other stakeholders, the public especially, who are directly influenced by their experience with the matter in question, for the advancement of pertinent knowledge and the development of new policies concerning the promotion of tap water use and sustainable water resource management.

2. Methodology and Research Design

A combination of methods was used to address the research objective in the use case of the city of Kilkis in the Region of Central Macedonia, situated in northern Greece, with a population of 30,000 residents. A consultation with professionals and decision-makers facilitated comprehension and the development of a survey for community members who were also consumers.

2.1. Qualitative Research

Firstly, a focus group dialog took place with experts and policy-makers in the region. The research team used in-depth interviews to help them understand the key factors that influenced consumers’ attitudes towards drinking water, involving a total of 20 participants across three focus groups. The team used feedback from focus group notes and quotes to enhance the quantitative analysis results.

2.2. Survey

Every person residing in Kilkis city was considered a potential user of drinking water and had the opportunity to take part in the research study. The precise number of people was recorded in the 2021 census data by the National Statistical Service of Greece. The research involved a sample size including 407 randomly selected residents to achieve statistically significant results at a 95% confidence level (α = 0.05) and a 5% error margin, which was determined using Raosoft’s formulas for calculating sample size [36]. A sampling unit was selected from each household, with the units chosen randomly.

The survey was split into five parts:

- -

- The first part specifically looked at whether consumers chose tap water or bottled water for drinking;

- -

- The following part of the survey asked about how consumers viewed the quality of drinking water in their area;

- -

- In the next section, inquiries regarding consumers’ understanding, education and awareness of issues related to drinking water and environmental concerns were included;

- -

- The fourth section comprised inquiries about consumers’ readiness to utilize and finance recycled or reclaimed water;

- -

- Finally, the fifth section contained inquiries about consumers’ socio-demographic data, including gender, education, income, occupation and related information.

Data were collected via individual interviews using a detailed questionnaire designed specifically for this research (see Supplementary Materials). In June and September 2022, a team of skilled interviewers conducted all interviews through the use of the questionnaire.

2.3. Statistical Data Analysis

Multivariate analysis methods were utilized on the 407 valid survey records gathered to unveil important data from consumers’ answers:

- Initially, cluster analysis was carried out to categorize survey participants, based on their water purchasing/consumption behavior, into different groups. In this context, hierarchical and non-hierarchical procedures were used, specifically Two-Step Cluster Analysis and K-Means Cluster Analysis.

- Next, a x2 (Chi-Square) test was employed with cross-tabulation analysis to compare the distribution of water consumers between the clusters defined, based on their

- socio-demographic patterns

- environmental awareness.

x2 (Chi-Square) cross-tabulation analysis is a widely used statistical method examining the relationships between categorical variables. It is particularly useful for assessing the homogeneity between populations or groups [37], as shown by [38], who analyzed environmental awareness in relation to drinking water purchasing behavior. Cross-tabulation, also referred to as contingency table analysis, was opted for as an appropriate statistical method available when performing a survey analysis and comparing the results for one variable with the results of another, particularly when analyzing categorical (nominal measurement scale) data. Practically, cross-tabulations can just be data tables that display the findings from the subgroups of survey participants, such as the clusters/groups determined in the current research. The contingency tables allowed us to look at connections in the data that may not have been immediately obvious when examining the overall number of survey replies. The main statistic for determining if the cross-tabulation table was statistically significant was the Chi-Square statistic. The two variables’ dependence or independence was examined using Chi-Square testing. The choice of the cross-tabulation x2 analysis was based on its simplicity, interpretability and ability to compare distributions between different groups [39]. For example, primary school students’ attitudes towards environmental issues were assessed using cross-tabulation x2 analysis to classify students based on their levels of knowledge and awareness [40]. Similarly, the same method was used to investigate the effect of ambient temperature on sleep needs in emergency hospitals in order to assess the importance of environmental factors on patient behavior [41]. These examples can highlight the potential of this analysis to identify the significant patterns and associations within categorical data.

3. Results and Discussion

The average subject of this study was a 43-year-old person that had completed college, worked full-time in a private company, lived in an apartment and had a family income in the range of EUR 8801 to 13,200 annually.

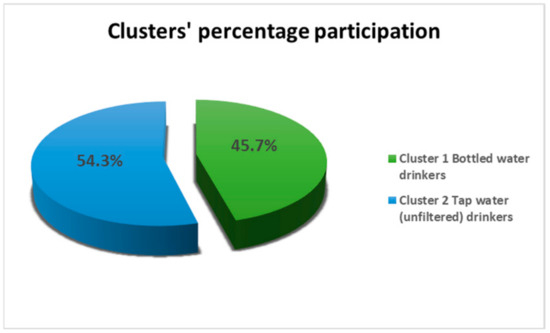

Utilizing both hierarchical and non-hierarchical clustering techniques helped in forming a categorization of customers’ purchasing behaviors. There were no irregularities detected in the 407 customers examined in the cluster analysis. Based on their water consumption habits and preferences, two distinct consumer groups were identified through cluster analysis. There were two groups: “Bottled water drinkers” accounted for 45.7% of the survey sample, while “Tap water (unfiltered) drinkers” made up 54.3%, thus being the majority of the participants (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Citizen clustering based on their drinking water consumption habits and preferences.

In relation to the first group, people characterized as “Bottled water drinkers” chose bottled water over unfiltered tap water when they were out and about or traveling. External opinions and the water provider’s brand impacted the purchasing decisions of this particular demographic. They lacked trust in the local water supplier and were reluctant to buy or trust bottled tap water. Although the water quality could be excellent, a lot of people preferred not to drink tap water. The reason for this was the belief that tap water and its quality remained unfavorable [14,28]. For comparison, it was shown in other studies among university students that they would buy bottled water, despite its high price, primarily for its flavor, and in part because of their irrational concerns about the quality of the tap water; however, there were water hydration stations all over the campus that were free, easily accessible and filtered [42]. Since bottled water has become a more and more popular tap water substitute, it is therefore urgent to design successful public health measures to guarantee drinking water quality at the point of use in the face of downgraded source waters [43]. It seems that previous policies were not widely recognized or lacked a significant impact because of a lack of confidence in the policy.

Citizens in the second group, “Tap water (unfiltered) drinkers”, chose to consume water from the community supplier. They trusted their community water provider and searched for details online regarding water-related matters. Additionally, they mentioned that when away from home or on the go, they opted to use bottled water rather than tap water. In the end, they were likely to use treated recycled wastewater from an urban water reuse initiative.

The results of the Chi-Square test with cross tabulation analysis conducted to examine the specific research objective, namely whether the distribution of drinking water consumers on the basis of their socio-demographic patterns differed between the aforementioned two consumer clusters (refer to contingency Table 1), showed that consumers’ choices of drinking water did not appear to be influenced by their socio-demographic patterns. Also, in another study regarding socio-demographic factors, no correlation was noted in relation to household drinking water quality [44]. On the other hand, other researchers indicated that particular socio-cultural elements and psychological obstacles might have been significant for a social acceptance disparity recorded between tap water and bottled options (only 50% of the individuals surveyed reported that tap water was socially accepted among family, friends and colleagues) [45].

Table 1.

Characteristics of the citizen clusters based on their socio-demographic profiles.

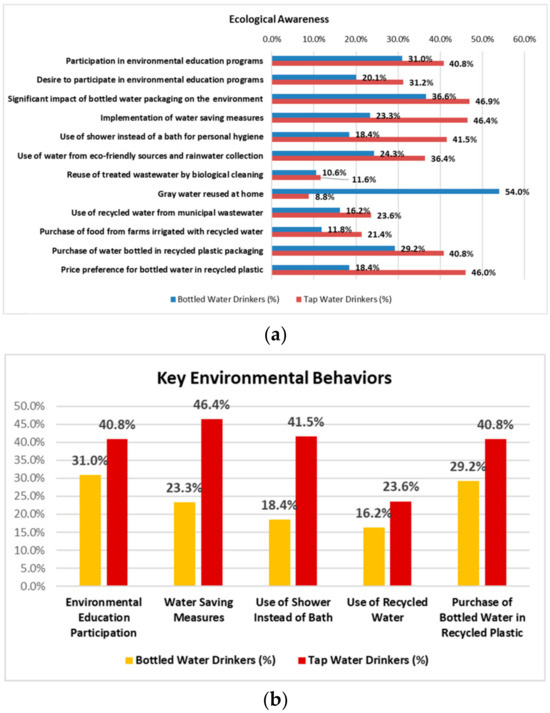

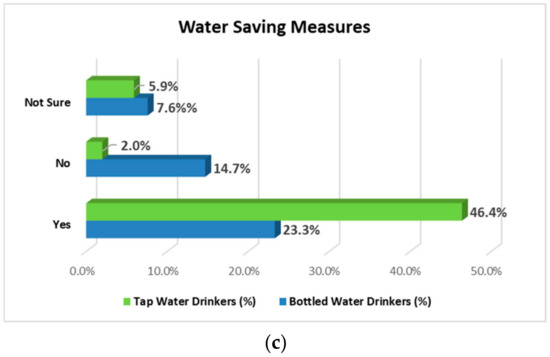

The results of the Chi-Square cross-tabulation analysis carried out to investigate the other specific research objective, namely whether the distribution of drinking water consumers on the basis of their ecological awareness/consciousness differed between the aforementioned two determined consumer clusters (“Bottled water drinkers” and “Tap water drinkers”), are provided in detail in the contingency Table 2.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the citizen clusters based on their environmental awareness/consciousness profiles.

The primary results in Table 2 clearly confirm a link between the factors influencing consumers’ choice of drinking water and their embrace of specific purchasing behaviors. Expectedly, the current research findings reveal that consumers’ preference of drinking water is particularly linked to their environmental awareness, as people who opt for tap water take steps to conserve water in their everyday habits and are also more inclined to use municipal wastewater that has been recycled and treated. Nevertheless, most consumers in both clusters/groups report not participating in environmental education programs, though they are prepared to contribute to them in the upcoming future. Moreover, people in both categories favor showering over bathing as a way to conserve water. Citizens recognize that bottled water packaging has significant impacts on the environment, and the majority are open to purchasing bottled water packaged in recycled plastic. On the other hand, individuals who purchase bottled water do not mind spending the usual price for recycled plastic bottled water, which is comparable to other relevant research findings [42]. It should be noted that those who drink unfiltered tap water want a discount for this compared to regular bottled water. The potential implementation of creative initiatives and programs like that launched (Philadelphia, USA) to use income-based billing to try to address the affordability issue, incorporating water, stormwater and wastewater service fees, may be of certain assistance [46].

Consumers’ sustainable decision-making can be heavily influenced by their comprehension, convictions and behaviors [47]. Furthermore, this study finds that customers place varying levels of importance on different internal and external factors when making decisions about bottled water. Therefore, the findings indicate that present-day consumers are concerned about the key environmental issues impacting the quality and accessibility of potable water. Fast-growing bottled water companies are increasingly focusing on the connections between business and the environment as well as consumption. Through a cross-sectional approach gathering data from online buyers, the views of consumers were explored prior to purchasing bottled water regarding the risk elements of the potential hazards caused by the pollution arising due to bottled water packaging. It was actually demonstrated that attitude, subjective norm and perceived behavior control regarding online bottled water purchases had a significant and beneficial influence on the consumers’ purchasing intentions based on the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB), expanded by adding risk components [48]. According to the TPB in other research, bottled water is less likely to be consumed by people who have a strong habit of drinking tap water [49].

Citizens’ growing awareness of the environmental impact of their food choices as their identities change has already been highlighted [50]. In fact, many citizens that participate in the current research show a strong desire for products and methods that greatly affect the environment (see Figure 2). As a result of this, they integrate water conservation techniques into their daily routines. Moreover, clients from both groups would make use of water obtained from a sustainable resource like rainwater. Nevertheless, most customers in both clusters are reluctant to consume water or purchase food produced from a farm using an eco-friendly source for watering, such as recycled wastewater (post-biological treatment), due to a fear of the unfamiliar. Indeed, “Bottled water consumers” object to using appropriately processed wastewater or gray water for household utilization, while “Tap water (unfiltered) consumers” are not willing to use water from these origins. Additionally, individuals who drink tap water (unfiltered) could potentially access recycled wastewater from a future program for urban water reuse, but those who prefer bottled water appear to be uncertain. Although they are considered to be more sustainable solutions, tap water and food produced with recycled water are thought to be less savory and healthful to ingest. Attitudes are reported to be linked to views about water quality (such as its sustainability, flavor and healthfulness), and expressed preferences and choices about products rely on explicit and implicit attitudes as well as on attributed beliefs [51].

Figure 2.

Characteristics of the citizen clusters based on their environmental awareness/consciousness profiles. (a) Citizens’ Ecological Awareness between the clusters; (b) Citizens’ Key Environmental Behaviors between the clusters; (c) Comparison of the Water Saving Measures between citizens’ clusters.

Similar studies reported in the literature, which were conducted in other regions of the world, have indicated that global bottled water consumption is on the rise in numerous countries, although tap water is still affordable and safe to drink, and is also favored for its resource efficiency and environmental benefits. For instance, in the USA (West Virginia), a study conducted at a major university revealed that one-third of the students primarily consumed bottled water at home, a behavior associated with the perceived water quality in a State with previous water quality issues [34]. In a U.K. survey, most participants would buy and consume bottled water following a related warning, yet as many as 44% would continue to drink tap water deemed unsafe [33]. In Belgium (Flanders), research showed that consuming bottled water was prevalent, even with the financial and environmental issues [31]. On the other hand, in countries with lower and middle incomes that have insufficient infrastructure, demographic and health surveys (e.g., in Somalia) have revealed the major difficulties encountered in offering better drinking water options, with a high occurrence of inadequate sources [52,53].

The degree of awareness and the optimistic outlook, however, still require improvement. For instance, people with higher levels of education tend to drink less bottled water [49]. Therefore, educational institutions and community centers should launch more extensive public awareness initiatives. Specific seminars and ecological awareness actions can also contribute to the education and motivation of the general public, with the goal of creating an environmentally literate society [54]. It is only by synthesizing how individuals view water and how they comprehend the issues and hazards related to it that we can gain a clearer insight into the fundamental assumptions behind their thought processes and environmental perspectives.

It should be noted here that some of the survey participants spontaneously recorded their negative views on the safety, flavor and smell of tap water as being barriers influencing their motivation to consume fluorinated tap water, possibly associated with the perceived health hazards also claimed in another relevant study [32]. This may be indicative of a certain distrust in local water suppliers, which is an important factor influencing drinking water choices. Thus, it is a valuable area for further investigation, and examining it could enhance the depth and applicability of future research.

Environmental issues also involve socio-political issues, because solutions can only be achieved by changing human behavior [55]. For maintaining high water quality standards and moving toward sustainable water resource management, new water quality policies should be formulated within an integrated strategic framework, taking into account important sustainability indicators from the aforementioned perspectives [56]. In order to encourage sustainable growth and environmental behavior, future research should concentrate on new concerns [57]. Moreover, further research into how environmental knowledge affects consumer behavior may yield more tap water promotion insights.

Moreover, the usage of recycled water should be seriously considered on a large-scale basis in the future, not only due to the scarcity of potable water and its distribution but also due to the other challenges that will be faced, including human, animal and environmental health issues, in the context of the One Health holistic approach [3]. Water influences socio-economic systems by impacting physical and mental health and overall social well-being [58,59]. For instance, water shortages impact health and wellness in many ways, including insufficient water (both for drinking and hygiene), risks of illnesses, wildfires, poor air quality as well as food insecurity and malnutrition. Other extreme climate events (like heat waves as well as risks of flooding or infectious disease outbreaks) and their related health effects may possibly be enlarged. In agriculture, drought can result in income loss and joblessness, prompting internal and cross-border migration, along with a rise in food prices [60,61]. Furthermore, water shortages can disrupt the ecological equilibrium of natural systems and negatively impact biodiversity, including fish, wildlife and plant species, along with the benefits that these ecosystems offer to human populations [62].

In this context, the present study provided answers to understand public perceptions of the water sector and how they impact social engagement to raise social awareness of ecological consumption and to help and motivate water policy-makers to assess the situation, plan appropriate campaigns and take the necessary actions for promoting tap water use. In order to significantly boost the tap water consumption rate, it is essential to enhance the projects and social campaigns that consumers can engage with directly in the designated area. Such actions can enhance trust in healthy water policies, which in turn influences individuals’ behavior regarding tap water consumption, and can also employ a promotional approach for those who are either satisfied or somewhat dissatisfied with tap water, proving efficiency in increasing tap water intake.

4. Conclusions

The current study aimed to investigate the social behavior regarding the consumption of drinking water, which has become more significant in modern society due to its socio-economic and geo-political implications. To meet the goals of this research, we needed to determine whether the citizens were aware of the quality of the water they were drinking and the implications related to environmental sustainability and health.

The primary results revealed a clear link between the factors influencing citizens’ choices of drinking water and their embrace of specific social behaviors. In addition, the study found that consumers placed varying levels of importance on different internal and external factors when making decisions about bottled water. Therefore, the findings indicated that citizens were concerned about the key environmental issues impacting the quality and accessibility of potable water. Many customers showed a strong desire for products and methods that greatly affected the environment. As a result of this, they integrated water conservation techniques into their daily routines, although most customers were reluctant to consume water or purchase food produced from an eco-friendly source, such as recycled wastewater (post-biological treatment), due to a fear of the unfamiliar. Consumers’ choices of drinking water did not appear to be influenced by their socio-demographic elements. On the other hand, the results indicated that citizens’ environmental consciousness was correlated with their choice of drinking water. Actually, people were more inclined to use treated recycled urban wastewater when they chose to use tap water and adopt water-saving practices in their daily lives. These findings suggest that citizens’ choices in drinking water were significantly impacted by environmental awareness.

Certain limitations of this study can be noted. Despite conducting wide-ranging research, the study focused on the use case of Kilkis city, Greece. It would be interesting to further extend this work in a multi-location study to encompass other urban areas or countryside regions, to potentially provide broader results and insights into consumer water choice behavior. Another built-in shortcoming is that the survey was carried out over a specific time during the economic, health and energy emergency period. Considering citizens’ beliefs, perceptions, attitudes and awareness of drinking water over a longer duration, and also exploring the factors that impact consumer decisions on drinking water after the crises, would be intriguing in a future study.

Nevertheless, this research offered responses in order to learn how the public views the water sector and the way it affects the social engagement process for enhancing ecological consumption awareness, and also assisted and inspired water policy-makers and the public sector to evaluate the circumstances, organize relevant campaigns and education programs and take appropriate initiatives for further enhancing ecological consciousness and promoting more sustainable and healthy water consumption options, such the use of tap water. To conclude, this research emphasizes the significance of social surveys in effectively understanding citizens’ drinking water preferences and the factors that affect water management choices and decision-making.

Future water quality policies should be developed within a strategic framework, considering crucial key sustainability indicators from the aforementioned perspectives on maintaining high water quality standards to move towards sustainable water resource management practices.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/su17083597/s1, S1: The Consumer Questionnaire from the survey.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.S. and M.P.; Investigation, P.K. and M.P.; Methodology, G.T. and M.P.; Project administration, P.S.; Resources, P.A. and P.K.; Supervision, P.S. and G.T.; Validation, P.K. and E.L.; Visualization, P.A., E.L. and V.K.; Writing—original draft, G.T., P.A. and V.K.; Writing—review and editing, E.L. and V.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This project was financed by the E.U. through the ENI CBC Mediterranean Sea Basin Programme. The information in the present work does not in any way represent the views of the E.U. or the Programme management.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Since it was a social study with anonymous questionnaires, no specific ethical approval was required, however the Ethics Committee of the International Hellenic University, Greece was informed on time and the appropriate Blank Consent Form provided by the Committee was used. This form was given to the research participants of the use case of Kilkis city, Greece.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article and Supplementary Materials.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Aguirre, K.A.; Cuervo, D.P. Water Safety and Water Governance: A Scientometric Review. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Valderrama, J.; Olcina, J.; Delacámara, G.; Guirado, E.; Maestre, F.T. Complex Policy Mixes are Needed to Cope with Agricultural Water Demands Under Climate Change. Water Resour. Manag. 2023, 37, 2805–2834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO (World Health Organization). One Health. 2024. Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/one-health#tab=tab_1 (accessed on 25 March 2025).

- Ruiz-Garzón, F.; Olmos-Gómez, M.d.C.; Estrada-Vidal, L.I. Perceptions of Teachers in Training on Water Issues and Their Relationship to the SDGs. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anadu, E.C.; Harding, A.K. Risk perception and bottled water use. J. Am. Water Work. Assoc. 2000, 92, 82–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romano, G.; Masserini, L. Factors affecting customers’ satisfaction with tap water quality: Does privatisation matter in Italy? J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 258, 120593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueiredo, M.; Fernandes, A.; Neves, J.; Vicente, H. Sustainable Water Use and Public Awareness in Portugal. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustavsen, G.W.; Hegnes, A.W. Turning the Tap or Buying the Bottle? Consumers’ Personality, Understanding of Risk, Trust and Conspicuous Consumption of Drinking Water in Norway. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De França Doria, M. Factors influencing public perception of drinking water quality. Water Policy 2010, 12, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Z.; Xu, X.; Hu, L.; Liu, J.; Yan, X.; Han, M. A study on long-term forecasting of water quality data using self-attention with correlation. J. Hydrol. 2025, 650, 132390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Morton, L.W.; Mahler, R.L. Bottled Water: United States Consumers and Their Perceptions of Water Quality. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2011, 8, 565–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubens, L.; Le Roy, J.; Rioux, L. Consumption of tap water, perceived health and beliefs in health and illness. Environ. Risques Santé 2012, 11, 212–220. [Google Scholar]

- Pierce, G.; Gonzalez, S. Mistrust at the tap? Factors contributing to public drinking water (mis)perception across US households. Water Policy 2017, 19, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debbeler, L.J.; Gamp, M.; Blumenschein, M.; Keim, D.; Renner, B. Polarized but illusory beliefs about tap and bottled water: A product- and consumer-oriented survey and blind tasting experiment. Sci. Total. Environ. 2018, 643, 1400–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyritsakas, G.; Boxall, J.B.; Speight, V.L. A Big Data framework for actionable information to manage drinking water quality. Aqua-Water Infrastruct. Ecosyst. Soc. 2023, 72, 701–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokkinos, K.; Lakioti, E.; Samaras, P.; Karayannis, V. Evaluation of public perception on key sustainability indicators for drinking water quality by fuzzy logic methodologies. Desalination Water Treat. 2019, 170, 378–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javidi, A.; Pierce, G.U.S. Households’ Perception of Drinking Water as Unsafe and its Consequences: Examining Alternative Choices to the Tap. Water Resour. Res. 2018, 54, 6100–6113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grupper, M.A.; Schreiber, M.E.; Sorice, M.G. How Perceptions of Trust, Risk, Tap Water Quality, and Salience Characterize Drinking Water Choices. Hydrology 2021, 8, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rico, M.S.O.; Vergara-Romero, A.; Subia, J.F.R.; del Río, J.A.J. Study of citizen satisfaction and loyalty in the urban area of Guayaquil: Perspective of the quality of public services applying structural equations. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0263331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, K.; Chen, Z.; Wang, H. How do citizens feel about their water services in the water sector? Evidence from the UK. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2021, 33, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, J.; Kang, S. Another Injustice? Socio-Spatial Disparity of Drinking Water Information Dissemination Rule Violation in the United States. J. Policy Stud. 2022, 37, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hundemer, S.; Monroe, M. Stakeholder Engagement and Communication for Water Policy, Book Chapter. In Elgar Encyclopedia of Water Policy, Economics and Management; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2024; pp. 246–251. [Google Scholar]

- Khumalo, L.; Mickelsson, M.; Fogel, R.; Mutingwende, N.; Madikiza, L.; Limson, J. Progressing from Science Communication to Engagement: Community Voices on Water Quality and Access in Makhanda. Sustainability 2024, 16, 459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barhoumi, B.; Metian, M.; Zaghden, H.; Derouiche, A.; Ben Ameur, W.; Ben Hassine, S.; Oberhaensli, F.; Mora, J.; Mourgkogiannis, N.; Al-Rawabdeh, A.M.; et al. Microplastic-sorbed persistent organic pollutants in coastal Mediterranean Sea areas of Tunisia. Environ. Sci. Process. Impacts 2023, 25, 1347–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gambino, I.; Bagordo, F.; Grassi, T.; Panico, A.; De Donno, A. Occurrence of Microplastics in Tap and Bottled Water: Current Knowledge. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 19, 5283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouri, A.; Guesmi, M.; Jlalia, I.; Grassl, B.; Abderrazak, H.; Souissi, R. Assessing microplastic presence and distribution in sandy beaches: A case study of the Gulf of Tunis coastline. Euro-Mediterranean J. Environ. Integr. 2024, 10, 437–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phinikettou, V.; Papamichael, I.; Voukkali, I.; Economou, F.; Golia, E.E.; Navarro-Pedreño, J.; Barceló, D.; Naddeo, V.; Inglezakis, V.; Zorpas, A.A. Micro plastics mapping in the agricultural sector of Cyprus. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 370, 122414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhelaeva, S.E.; Khamaganova, T.K.; Sharaldaev, B.B.; Garmaeva, E.T.; Hunkai, Y.; Burtonova, G.B.; Shapkhaev, B.S. The bottled drinking water market in China: Features of sustainable development. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2021; Volume 885, p. 012044. [Google Scholar]

- Ulusoy, C.K. The Importance of Being Returned from Bottled Water to Tap Water in Turkey in Terms of Sustainable Development. World Sustainability Series; In An Agenda for Sustainable Development Research; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; Part F3447; pp. 265–276. [Google Scholar]

- Directive (EU) 2020/2184 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 16 December 2020 on the quality of water intended for human consumption. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2020/2184/oj/eng (accessed on 13 April 2025).

- Geerts, R.; Vandermoere, F.; Van Winckel, T.; Halet, D.; Joos, P.; Steen, K.V.D.; Van Meenen, E.; Blust, R.; Borregán-Ochando, E.; Vlaeminck, S.E. Bottle or tap? Toward an integrated approach to water type consumption. Water Res. 2020, 173, 115578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Family, L.; Zheng, G.; Cabezas, M.; Cloud, J.; Hsu, S.; Rubin, E.; Smith, L.V.; Kuo, T. Reasons why low-income people in urban areas do not drink tap water. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2019, 150, 503–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rundblad, G. The semantics and pragmatics of water notices and the impact on public health. J. Water Health 2008, 6, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leveque, J.G.; Burns, R.C. Drinkingwater in West Virginia (USA): Tap water or bottled water-what is the right choice for college students? J. Water Health 2018, 16, 827–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, S.H.; Sakai, H. Perceptions of water quality, and current and future water consumption of residents in the central business district of Yangon city Myanmar. Water Supply 2022, 22, 1094–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raosoft. 2004. Available online: http://www.raosoft.com/samplesize.html (accessed on 1 April 2022).

- Wikipedia. 2023. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Contingency_table (accessed on 7 November 2023).

- Sugiyono; Dewancker, B.J. Study on the DomesticWater Utilization in Kota Metro, Lampung Province, Indonesia: Exploring Opportunities to Apply the Circular Economic Concepts in the DomesticWater Sector. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qualtrics.xm. 2025. Available online: https://www.qualtrics.com/experience-management/research/cross-tabulation/?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 4 April 2025).

- Rehman, N.; Zhan, W.; Khalid, M.S.; Iqbal, M.; Mahmood, A. Assessing the knowledge and attitude of elementary school students towards environmental issues in Rawalpindi. Present. Environ. Sustain. Dev. 2021, 15, 5–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budiharjo, N.; Sismulyanto; Kuswandari, H.; Nurdiana, O.; Mursaka; Ulumuddin, Y. The Relationship between Environmental Temperature and Sleep Needs of Patients in Emergency Hospitals. Medico-Legal Updat. 2021, 21, 52–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, A.; DeStefano, K.; Pineño, O. Some Determinants of Bottled vs. Tap Water Choice on Campus. Psicologica 2024, 54, 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Bear, S.E.; Waxenberg, T.; Schroeder, C.R.; Goddard, J.J. Bottled water, tap water and household-treated tap water–insight into potential health risks and aesthetic concerns in drinking water. PLoS Water 2024, 3, e0000272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ondieki, J.; Akunga, D.; Warutere, P.; Kenyanya, O. Socio-demographic and water handling practices affecting quality of household drinking water in Kisii Town, Kisii County, Kenya. Heliyon 2022, 8, e09419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garfí, M.; Requejo-Castro, D.; Villanueva, C.M. Social life cycle assessment of drinking water: Tap water, bottled mineral water and tap water treated with domestic filters. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2022, 112, 107815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mack, E.A.; Wrase, S.; Dahme, J.; Crosby, S.M.; Davis, M.; Wright, M.; Muhammad, R. An Experiment in Making Water Affordable: Philadelphia’s Tiered Assistance Program (TAP). J. Am. Water Resour. Assoc. 2020, 56, 431–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peschel, A.O.; Grebitus, C.; Steiner, B.; Veeman, M. How does consumer knowledge affect environmentally sustainable choices? Evidence from a cross-country latent class analysis of food labels. Appetite 2016, 106, 78–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, M.; Tan, C.L.; Wu, L.; Peng, J.; Ren, R.; Chiu, C.H. Determinants of intention to purchase bottled water based on business online strategy in china: The role of perceived risk in the theory of planned behavior. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 10729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zvěřinová, I.; Ščasný, M.; Otáhal, J. Bottled or Tap Water? Factors Explaining Consumption and Measures to Promote Tap Water. Water 2024, 16, 3011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalampira, E.S.; Papadaki-Klavdianou, A.; Nastis, S.; Partalidou, M.; Michailidis, A. Food for thought: An assessment tool for environmental food identities. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2019, 27, 80–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bass, D.A.; McFadden, B.R.; Costanigro, M.; Messer, K.D. Implicit and Explicit Biases for Recycled Water and Tap Water. Water Resour. Res. 2022, 58, e2021WR030712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, A.M.; Barakale, N.M.; Salih, O.; Muse, A.H. Unimproved source of drinking water and the associated factors: Insights from the 2020 Somalia demographic and health survey. PLoS Glob. Public Health 2024, 4, e0003844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nel, M.; Simuyaba, M.; Muchelenje, J.; Chirwa, T.; Simwinga, M.; Speight, V.; Mhlanga, Z.; Jacobs, H.; Nel, N.; Seeley, J.; et al. Broad Brush Surveys: A rapid qualitative assessment approach for water and sanitation infrastructure in urban sub-Saharan cities. Front. Sustain. Cities 2023, 5, 1185747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, I.; Hayat, W.; Gong, S.; Yang, X.; Lai, W.-F. A Comparative Analysis of Public Awareness Level about Drinking Water Quality in Guangzhou (China) and Karachi (Pakistan). Sustainability 2023, 15, 8408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaseková, V. How do people in China perceive water? From health threat perception to environmental policy change. J. Environ. Stud. Sci. 2022, 12, 627–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilalova, S.; Newig, J.; Tremblay-Lévesque, L.-C.; Roux, J.; Herron, C.; Crane, S. Pathways to water sustainability? A global study assessing the benefits of integrated water resources management. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 343, 118179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patiño-Toro, O.N.; Valencia-Arias, A.; Palacios-Moya, L.; Uribe-Bedoya, H.; Valencia, J.; Londoño, W.; Gallegos, A. Green purchase intention factors: A systematic review and research agenda. Sustain. Environ. 2024, 10, 2356392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E.U. European Climate and Health Observatory. Drought and Water Scarcity. 2025. Available online: https://climate-adapt.eea.europa.eu/en/observatory/evidence/health-effects/drought-and-water-scarcity (accessed on 4 April 2025).

- UNDRR. GAR Special Report on Drought 2021. Geneva. 2021. Available online: https://www.undrr.org/publication/gar-special-report-drought-2021 (accessed on 14 October 2021).

- Ebi, K.L.; Vanos, J.; Baldwin, J.W.; Bell, J.E.; Hondula, D.M.; Errett, N.A.; Hayes, K.; Reid, C.E.; Saha, S.; Spector, J.; et al. Extreme Weather and Climate Change: Population Health and Health System Implications. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2021, 42, 293–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryan, K.; Ward, S.; Roberts, L.; White, M.P.; Landeg, O.; Taylor, T.; McEwen, L. The health and well-being effects of drought: Assessing multi-stakeholder perspectives through narratives from the UK. Clim. Change 2020, 163, 2073–2095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. National Integrated Drought Information System. 2025. Available online: https://www.drought.gov/sectors/ecosystems (accessed on 4 April 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).