Abstract

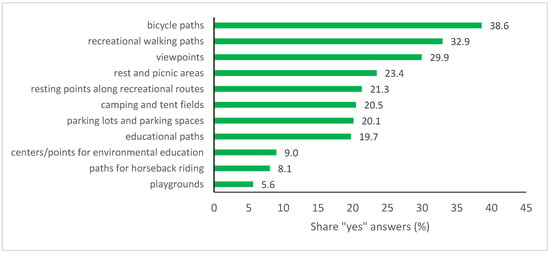

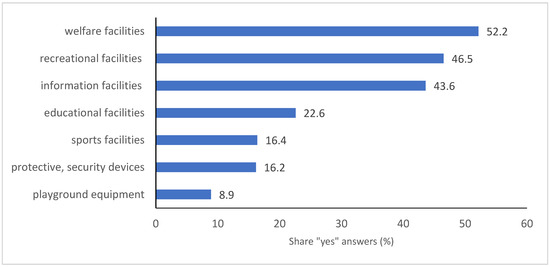

In recent years, there has been a systematic return of humans to nature, the importance of the services and benefits provided by forests and other green spaces has increased, and thus the interest in recreational facilities that appear in forest areas has also increased. Recreational infrastructure in forests is essential to enhance the visitor experience while ensuring the ecological sustainability of forest ecosystems. The aim of our research was to establish how the socio-demographic factors have influenced the public perception of recreational infrastructure in forests, and how the demand for certain types of recreational land facilities has changed. The research material consists of the results of a questionnaire survey (online and traditional) carried out in Poland from September to October in 2020. A total of 1402 people were surveyed. A logistic regression (LR) model was used to determine the influence of the socio-demographic profile of the respondents on their perception of the importance of recreational infrastructure. The results indicate that linear recreational infrastructure, i.e., cycling (38.6% of respondents), walking (32.9%), and educational paths (19.7%), were of greatest interest. Viewpoints were highly preferred by respondents (29.9% of respondents). The demand for recreational facilities was mainly determined by the age and number of children owned and the place of residence of the respondents. Other socio-demographic characteristics, i.e., education level, gender, and satisfaction with the standard of living, were less influential on respondents’ views. Among the most needed recreational amenities in forests, social (52.2%) and recreational (46.5% of respondents) facilities were highlighted. The factors most strongly determining respondents’ views on the need to develop a particular type of recreational facilities in the forest were frequency of visits to the forest and distance of residence from the forest. Other factors such as age, education level, gender, or the number of children owned determined respondents’ opinions on the issues analyzed to a lower extent. The results are of great use, allowing public forest managers to better plan infrastructure in forest areas. Our research provides valuable insights into the management of forests, especially those with dominant social functions. The resulting recommendations allow us to prepare forests for changing demographic trends (an expected increase in urbanized areas and aging population) and rising social expectations. We prove that forests and recreational infrastructure are crucial in promoting people’s physical and mental health. Properly planned recreational infrastructure is able to encourage more physical activity outdoors and more frequent visits to forests.

1. Introduction

In many countries, it has been observed how the roles performed by forests have changed over time [1,2,3]. Forests traditionally used as a source of timber are increasingly serving as recreational areas. Currently, forests’ regulatory and cultural functions are most highly valued, while the provisioning functions occupy a lower position [4,5]. The COVID-19 pandemic, which caused a surge in public awareness of the role of forests in maintaining public health, contributed greatly to the change in perception of the importance of forest ecosystem services [6]. Restrictions on using forests during the pandemic convinced people that forests provided an important place for outdoor physical activity, recreation, and leisure, which are essential for emotional balance and well-being. As restrictions eased, forests became increasingly popular places for walking, chosen because of the need to avoid crowded places and the opportunity to find peace and rest from the daily sense of danger [7,8]. Outdoor environments such as forests had far fewer touch surfaces that could harbor the virus, clearly reducing the risk of infection [9]. Meanwhile, expectations for tourism and recreation have also increased. Trends in recreational infrastructure also focus on sustainability, multifunctionality, and integration with the environment. Recreational infrastructure must be environmentally friendly and built using new technologies and natural elements to create aesthetically pleasing and functional spaces [10]. It must be built with the general public in mind, offering a variety of functions and year-round use. Emerging infrastructure is designed with economic and environmental efficiency in mind [11]. The European Union, to make tourism more competitive and resilient, has set even higher expectations for it—today’s tourism needs to be greener, more digital, and more sustainable. Europe has been betting for years on health tourism and tourism related to cultural and natural heritage [12,13,14]. According to the EU’s New Forest Strategy 20230 [15], the growing popularity of nature-based tourism and well-being services through communing with nature is a guarantee of prosperity, increasing people’s physical and mental health, but also an opportunity to accelerate the ecological transformation of the tourism sector. Both ecotourism and nature-based recreation are becoming increasingly important to a growing global population [1,7,16,17,18]. An overvaluation of the functions forests perform has been observed in many countries [1,2,3]. In particular, forests in cities and suburban zones have begun to be seen as a new living room [19]. With low physical activity, the sedentary lifestyle of most people living in cities, noise, and information overload, it is becoming increasingly urgent to find solutions that facilitate contact with nature and encourage people to be active in nature. Furthermore, many studies [20,21,22] have proved that physical activity in a natural environment might bring greater health benefits than physical activity in other places. There are already several works indicating what characteristics urban green space should have [23,24,25] to increase people’s physical activity and encourage recreation in contact with nature. However, according to Smith et al. [26], there is still limited consensus on the elements and features of the environment that act as determinants of physical activity in populations. As the pattern of recreational activities has changed from passive forms (e.g., rest, relaxation, revival, solitude, and escape) to more active forms (e.g., mountain biking, climbing, and running), the need for forest recreational infrastructure to support more active forms has increased.

Forests are increasingly becoming an area for various physical activities such as walking, trekking, cycling, or running, which are also being undertaken as an organized form of physical activity and sport [18,27]. Recreational infrastructure in forests contributes to the health of urban residents by increasing their physical activity, strengthening social ties, and supporting the aspirations of senior citizens in improving their physical and mental health [28]. Recreational facilities are a key component of research and tourism, yet in environmental studies they are seen as secondary to the natural qualities of an area [29]; it is the recreational infrastructure in forests that determines the overall ability to utilize forest resources and is essential to enhancing the visitor experience while ensuring ecological sustainability. By affecting the aesthetic experience, it is an integral part of recreational ES, combined with the physical use of the environment [30,31]. Infrastructure, along with associated services, expands the palette of regenerative benefits offered by forest ecosystems [32]. It supports the aspirations of seniors in improving their physical and mental health [28]. Recreational infrastructure in forests is essential to enhance the visitor experience while ensuring ecological sustainability. Key elements of such infrastructure include trails, signage, rest areas, and facilities catering to various recreational activities [33]. In addition, infrastructure is part of specialized forest management, primarily those with particularly specific social functions such as national parks, scenic parks, suburban forests, intensive recreation and tourism areas, and experimental forests. Recreational development of the forest is considered in the National Forest Policy [34] as an activity that strengthens the social functions of the forest, contributing to the mitigation of potential conflicts with other forest functions and functions of adjacent areas. Recreational infrastructure, by properly regulating and directing recreation and tourism in forest areas in a way that reconciles the social functions of forests with protective and productive functions, promotes forest improvement and conservation.

Many previous studies [35,36,37] on forest recreation focus on environmental sustainability. However, little is known about what characteristics characterize the planning and management of forest recreational infrastructure [38]. Little is also known about which infrastructure elements are more needed and which are less needed in forests. The development of recreational infrastructure must take into account both environmental and socioeconomic factors [32]. This is because the demand for a specific range of infrastructure is not constant; it changes under the influence of changing patterns of activity in nature, trends, and behavioral patterns. Hence, there is a need for systematic research to reinforce basic assumptions and confirm observed trends. Bell et al. [39] recommend conducting a series of baseline surveys from different countries, as well as longitudinal surveys conducted every 5–10 years, to help policymakers and planners develop policies and plans for the development of outdoor recreation and nature tourism. Understanding long-term trends in the demand for recreational infrastructure in forests requires a comprehensive approach that considers both spatial and temporal changes, the roles of existing infrastructure, and the social context. Hence, this study uniquely examines the interaction between socio-demographic factors and infrastructure needs. Hegetschweiler et al. [40] found that perceptions of cultural ecosystem services depend on various factors. Age, education level, gender, city of residence, membership in environmental organizations, and frequency of visits to nature affect perceptions of CES [41,42,43,44]. As the research of Flick et al. [45] indicates, the same aforementioned factors may also influence preferences for a particular assortment of recreational infrastructure in forests. However, we do not fully know how the demand for recreational infrastructure is correlated with the socio-demographic characteristics of forest visitors, as well as the frequency of visits and the distance of residence from the forest. Hence, the purpose of our research is to determine how the socio-demographic characteristics of forest land users affect their needs for recreational infrastructure in forests. In doing so, we pose the following research questions:

- -

- What assortment of recreational infrastructure is sought by forest users?

- -

- Does the frequency of visits to forests affect forest users’ preferences for recreational infrastructure?

- -

- Which socio-demographic characteristics determine the choice of certain types of recreational infrastructure in forests?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The Questionnaire

The research material consists of the results of a questionnaire survey carried out in Poland from September to October in 2020. It was both a distributed survey and an online survey. A link to the survey, created on the Webankieta (https://spoleczne-lasy.webankieta.pl/, accessed on 30 October 2020) platform, was made available on social networks. The survey questionnaire included questions about gender (female, male), age (18–30 years, 31–40 years, 41–50 years, and above 50 years), level of education (primary, secondary, higher), place of residence (rural area, small town with up to 15,000 inhabitants, medium town with 15,000–100,000 inhabitants, large town with more than 100,000 inhabitants), satisfaction with their standard of living, and also the frequency of recreation in the forest (daily, several times a week, several times a year) and the distance of residence from the forest (up to 3 km; 3–6 km; 6–10 km; more than 10 km). The questionnaire comprised nineteen thematic questions relating to various issues related to the ecosystem functions of the forest. Most of them were questions with a Likert scale of five degrees of appreciation (very important, important, moderately important, not very important, irrelevant) through which we could obtain knowledge about the degree of acceptance of the analyzed phenomena, views, processes, features of the forest, etc. This article draws on respondents’ views on the following issues:

- -

- What recreational infrastructure facilities do you think are missing in the forests? (Camping and tenting sites; recreational walking paths; playgrounds; bicycle paths; horseback riding paths; car parks; educational paths; picnic areas; environmental education points; viewpoints; resting points along recreational routes).

- -

- What recreational facilities do you think are missing in the forests? (Social facilities (e.g., toilets, trash garbage cans); sports facilities (e.g., gym fitness facilities); recreational facilities (e.g., shelters, benches); educational facilities (e.g., interpretative signs, educational panels; information facilities (road signs, signposts); playground facilities; protective facilities (barriers, fences)).

Respondents were asked to assess each report on one of five selectable responses ordered on a Likert scale.

2.2. Participants

Participation in the survey was voluntary and anonymous. Respondents were adults and asked for their opinions on infrastructure while in the forest, as well as via social media such as Facebook and Instagram. Survey participants were contacted in the field by a ‘liaison officer’, usually an employee of the district, included in the RDSF Radom, who, on his/her days off, outside of his/her professional duties, forwarded the link to the survey to all persons interested in forest recreation in the region. In the questions, we emphasized that we wanted answers on issues relating to these specific forests and the region in which we were conducting our research. A total of 1402 respondents took part in the survey, including 655 women (46.72%) and 747 men (53.28%). Respondents aged 31–40 years (31.1%) comprised the most numerous group. Respondents aged 18–30 accounted for 27.82% of respondents, followed by those aged 41–50 (23.97%) and those above 51 years (17.12%). Rural residents comprised the most numerous group (42.44%). The survey included 807 urban residents (57.56%), of whom 18.54% of respondents were from small cities (up to 15,000 residents), 23.18% from medium-sized cities (15–100,000 residents), and 15.83% from large cities (over 100,000 residents). The vast majority of respondents had a higher education (64.55%). Secondary education was held by 32.03% of respondents and primary education by only 3.42%. Almost half of the respondents (49.61%) declared that they rest in the forest several times a week, 37.7%—several times a year, and 12.69% rest in the forest daily. More than half of the respondents (51%) live up to 3 km from the forest, 23.7% live 3–6 km away, 11.5% live 6–10 km away, and 13.8% live more than 10 km away.

2.3. Statistic Analysis

A logistic regression (LR) model, in which the variables take dichotomous (qualitative) type values, was used to profile visitors regarding differences in perception of the particular recreational infrastructure’s importance. This model determines the probability that the dependent variable (here, the importance of recreational infrastructure or facilities) will take the value 1, provided that the explanatory variables (x1, x2, …, xi) take certain values [46]. A logistic model with one explanatory variable is defined by the following formula:

If Equation (1) is subjected to a logit transformation, we obtain the logit form of the model, which, generalized to multiple variables, is represented by the following equation:

The logit form of the model shown by Equation (2) is commonly used in research because of the intuitive, simple interpretation of the right-hand side of the equation as a linear function.

The socio-demographic characteristics of respondents were used as potential explanatory variables (gender, age, level of education, place of residence, number of children, satisfaction with the standard of living, distance of the place of residence to the forest, and frequency of visits to forests). All variables were binary in nature, taking the value 1 if the trait applied to the respondent and 0 if the respondent did not have it. The trait “gender” was described by two variables: “female” (F) and ‘male’ (M). If the respondent was female, the variable F = 1, otherwise F = 0. The variable M was coded in the same way. For variables consisting of several categories, zero–one variables were introduced. For example, the variable “age” included four age ranges coded with the following variables: A—respondents aged 18 to 30; B—respondents aged 31 to 40; C—respondents aged 41 to 50; D—respondents aged over 50. In addition, we used BCD (>30 years old) and CD (>40 years old) categories.

The analysis was conducted in two stages. First, the significance of the influence of all seven studied socio-demographic characteristics on the perceived importance of different types of recreational infrastructure in forests was investigated. In the second stage, the characteristics which showed a significant effect (p < 0.05) were used as explanatory variables for explaining the importance of a particular type of infrastructure or facilities. Correlations between the preliminary independent variables were tested, but ultimately, no such significant relationships (p-value < 0.05) were found between the proposed explanatory variables.

The quasi-Newton method was used to parameterize the model. The significance of the model parameters was assessed using the Wald test. The goodness of fit of the model to empirical data was assessed using the Hosmer–Lemeshow test [47]. The modeled probability P(x) that a respondent agrees with the surveyed opinion was determined by substituting into Equation (2) the corresponding values of the explanatory variables (1 or 0) describing the respondent’s socio-cultural characteristics.

In the logistic regression model, in addition to the regression coefficients and their statistical significance, another important parameter is the odds ratio (OR). OR is the ratio of the chance S(A) of an event occurring in group A (e.g., women agree with a given opinion) to the chance S(B) of that event occurring in group B (men agree with a given opinion).

OR = 1 indicates that the chance of agreeing with a given opinion is the same in the women’s group as in the men’s group; OR > 1 indicates that in the first group (women), agreement with a given opinion is significantly higher than in the second group (men). Conversely, OR < 1 indicates that in the first group (women), agreement with a given opinion is lower than in the second group (men). For example, if the odds ratio for the women variable is 2.00, then women are twice as likely as men to identify a given infrastructure component as important. In contrast, OR = 0.50 indicates that women were half as likely as men to indicate a given infrastructure component as important.

3. Results

3.1. Demand for Elements of Recreational Management of the Forest

In the group of recreational land-use facilities most needed in the forest, respondents indicated primarily linear facilities such as bicycle paths and recreational footpaths. Viewpoints and rest and picnic areas were also important to respondents. Playgrounds and paths for horseback riding, as well as environmental education points, were needed to a small extent in the forests, in the opinion of respondents—Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The deficiency of recreational infrastructure objects in the forest according to respondents’ opinions.

3.2. Factors Determining Respondents’ Preferences for Elements of Recreational Forest Management

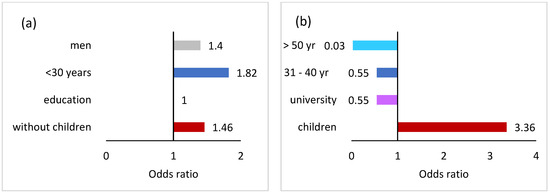

Only in the case of three elements—hiking trails, environmental education points, and horseback riding trails—did we find no statistical relationships between the analyzed variables and the respondents’ views (See Appendix A.1). None of the analyzed factors determined respondents’ opinions. We found that, most often, the age and number of children in the family differentiated the respondents’ opinions on the scarcity of elements of recreational forest management—Table 1.

Table 1.

Logit models of recreational infrastructure’s importance in the forest. Only significant variables are included. All variables are shown in Appendix A.1.

Opinion on the need for camping and tent fields was determined by gender, age, and having children. This type of infrastructure element was less often indicated as needed in the forest by women, older people, and those over 30. Demands for this type of facility were more often reported by those without children (Table 1, Appendix A.2, Figure A1a).

Views on the need for playgrounds were conditioned by education, age, and having children. Respondents with primary and secondary education often indicated playgrounds as needed in forests. Respondents over 50 and those who did not have children were far more likely to consider this type of recreational development unnecessary in the forest—(Appendix A.2, Figure A1b)

Bicycle paths were more often indicated as needed by residents of medium and small towns and villages, as well as respondents under the age of 50 and those who live more than 10 km from a forest (Appendix A.2, Figure A1c). Parking and parking facilities were more often indicated as needed by men, respondents over the age of 30, and those over the age of 50 (Appendix A.2, Figure A1d).

Educational trials were more often indicated as needed by women, as well as by respondents from medium-sized cities, small towns, or rural areas (Appendix A.2, Figure A1e). Recreation fields and picnic areas were more often ordered by young respondents < 30 years old than by older respondents and, in addition, respondents without children were more likely to indicate such facilities as unnecessary (Appendix A.2, Figure A1f).

In the case of viewpoints, we observed that respondents’ views on the desire for such facilities differed statistically significantly by education and number of children in the family. They were more often indicated as needed by respondents without children, as well as those with higher education (Appendix A.2, Figure A1g). In turn, rest points along the trails were more often indicated as needed by respondents over the age of 50 and also residents of large cities (Appendix A.2, Figure A1h).

3.3. Demand for Recreational Land Facilities

Of the various options for recreational infrastructure in the forests, the most needed, according to the survey, is social and living infrastructure—Figure 2. In addition, the group of the most needed types of infrastructure included recreational and informational facilities.

Figure 2.

Deficiency of recreational facilities in forests, according to respondents.

3.4. Factors Determining Respondents’ Preferences for Forest Recreational Facilities

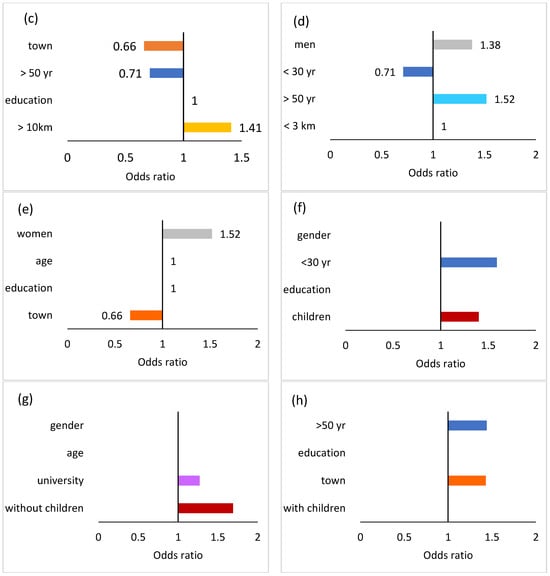

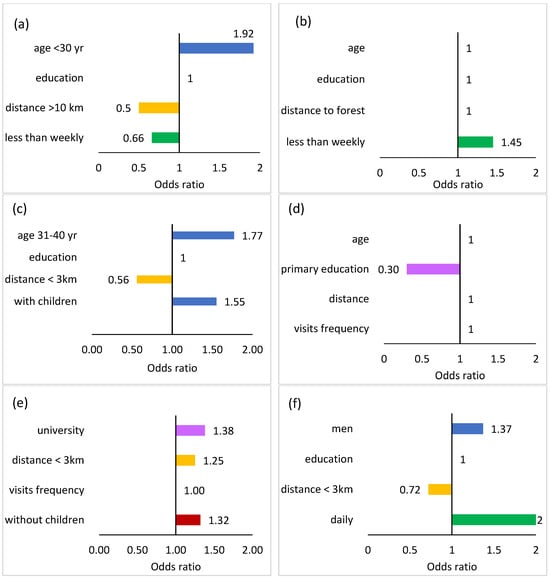

The results show that to the greatest extent, the opinion of respondents on the scarcity of facilities is determined by two factors: frequency of recreation and distance of residence from the forest—Table 2. To the least extent, these preferences are determined by the gender of respondents.

Table 2.

Logit models of recreational facilities’ importance in the forest. Only significant variables are included. All variables are shown in Appendix A.3.

Sports facilities were almost twice as often indicated as needed in the forest by those under 30 years of age. Respondents living more than 10 km from the forest and visiting the forest occasionally were more likely to indicate these facilities as unnecessary (Table 2, Appendix A.4, Figure A2a). Social and living facilities were almost 50% more likely to be indicated as needed by respondents occasionally visiting the forest (Appendix A.4, Figure A2b).

Respondents aged 31–40, as well as respondents with children significantly more often expressed the view that playground equipment was needed in the forests. They were more often considered unnecessary by respondents living less than 3 km from the forest, (Appendix A.4, Figure A2c). Educational devices were more often seen as unnecessary by respondents with primary education (Appendix A.4, Figure A2d).

Information equipment was more often indicated as necessary by respondents with higher education, living less than 3 km from the forest, and having no children (Appendix A.4, Figure A2e). Protective devices were more often indicated as necessary in the forest by male respondents who visit the forest daily. They were more often indicated as unnecessary by respondents who live within 3 km of the forest (Appendix A.4, Figure A2f).

4. Discussion

4.1. Demand for Recreational Forest-Management Elements

In Poland, there is a clear preference for forests with greater recreational infrastructure, equipped with a recreational clearing, barbecue areas, educational paths, and informational signs [48]. One of the most important elements of forest management is trails; they make forests accessible to visitors. Trails are the most important recreational infrastructure in the urban forest of Ljubljana, Slovakia. The majority of respondents preferred informal trails (54.9%) and official trails (42.7%), while gravel roads were the least preferred type [49]. Numerous forms of active recreation in forests, such as walking, cycling, and running, can be realized precisely thanks to a well-functioning network of forest roads. For a long time, the most preferred forms of recreation in forests in Poland have included walking and cycling according to Janeczko et al. [50], and the same is true in the Czech Republic [51], Slovakia [49], and Finland [52], among others. Despite this, however, bicycle paths have been considered more necessary in forests than walking paths. On the one hand, this may be because for walking, ordinary forest roads and branch lines, which do not need to have special amenities, are sufficient. At the same time, routes for cycling are attributed with greater requirements for, for example, better pavement [53]. On the other hand, in recent years, there has been an increase in interest in bicycle tourism in forests. A 2012 study indicated that over a decade there was a 6% increase in interest in cycling in forests within the Warsaw metropolitan area [50]. The preferences and expectations reported for hiking trails and forest recreational routes have long been of interest to researchers from different countries, such as, for example, those from Denmark [54], Austria [55], or Australia [56]. However, as Dorwart et al. [57] and Gundersen and Vistad [58] note, a lack of research specifically addresses the public’s preferences for different types of trails and paths in the forest. Our research shows that not all recreational trails are perceived as needed on forest lands. For example, educational trails, or paths for horseback riding, ranked quite far down the list of needed elements of recreational forest management. This is due to the fact that equestrian tourism is not very common in Polish society; it is a recreational activity perceived as elitist, expensive, and not entirely safe [59]. Educational trails, on the other hand, are not very popular among Polish forest users [53,60]. The fact that they are not particularly needed infrastructure may be determined by the fact that they are common in Polish forests. Hiking trails and forest roads are perceived as a kind of showcase of the forest, a kind of “guide” to the landscape, making it possible to observe the landscape variability of the forest. According to a review of studies [61], environmental attributes reported as favorable include aesthetic qualities, the connectivity of paths and streets, accessible destinations, and safety and lack of traffic. Recreational trails are popular because they provide access to nature values and nature-based experiences [56]. Trail corridors provide a context that provides access to places where visitors seek regenerative experiences [62,63]. The regenerative dimension of natural scenery has long been known, and contemporary scientific evidence supports the beneficial effects of the landscape on mental health [6,64,65]. Exposure to aesthetically pleasing views of nature supports healing and affects well-being. Laumann et al. [66], Reynolds et al. [67], and Ravenscroft [68] believe that human well-being is related to the aesthetics of a space, and they emphasize the importance of the scenic qualities of the landscape to increase visitor preference. People highly value experiencing nature and beautiful landscapes during outdoor activities according to Zeidenitz et al. [69]. Viewpoints make it easier to enjoy the landscape, hence their arguably high ranking among the necessary key elements of forest recreational management.

4.2. Determinants of Respondents’ Preferences for Forest Recreational Elements

Our research shows that the demand for a certain range of infrastructure changes under the influence of various socio-demographic characteristics. This includes the demand for camping areas and picnic clearings. Camping and picnicking are not among the particularly popular forms of recreation in Polish forests. Mainly because, according to the Forest Act, both of these forms of recreation can only be carried out in places designated by the owner or forest manager; besides, unlike walking or nature observation, they are seasonal forms of recreation. In other countries such as Italy, Canada, and the United States, for example, they are much more preferred [39]. In the United States and Canada, according to a report, “Camping and Outdoor Hospitality” [70] shows that demographically, almost half of the campers are under the age of 35. At the same time, 64% of new campers have no children in the household. On the other hand, earlier work by Joppe and Brooker [71] shows that demographically, camping and outdoor hospitality appeals to all age ranges, with the exception of the teenage age category (18–24). Couples most often participate in camping with children aged 6 to 12 years old contributing to the family nature of many OHPs (outdoor hospitality parks). However, outdoor hospitality is also popular among mature couples without children. In Poland, bivouac or tent camping sites are rather low-standard and simple facilities, offering spartan conditions associated with bushcrafting and survivalism rather than glamping and caravanning. For this reason, they are more likely to be preferred by younger, energetic, and vigorous users, as our research has also shown. We further showed that recreational clearings and picnic areas were equally more frequently ordered by young respondents < 30 years old than by older respondents. Younger forest users show more social and active forest use, while adults use forests more contemplatively [40]. For this reason, resting points along trails are important to this group of respondents. It should be noted, however, that older citizens have additional demands on trial infrastructure due to their declining physical and visual abilities [39], hence the postulated retrofitting of rest points along trails for this group. Urban residents were also more likely to indicate the need for such infrastructure to be organized in forests. Perhaps through rest points, the forest becomes more ‘tame’, more predictable, and more identified with the urban park. Age and having children in the household also influenced respondents’ opinions regarding the need for children’s playgrounds. Such facilities are preferred more by people with children. According to Eurostat data [72], the average age at which a mother gives birth to her first child is 29.7 in the EU. Almost all member states postpone this decision for longer each year. In Poland, the average age of a woman giving birth to her first child is 28.2. Women who became first-time mothers after 30 have accounted for more than half of all mothers in the 15–49 age group for several years. Because of this, playgrounds were seen as unnecessary in the forests more often by users under 30. Nor were these facilities important to users who did not have children in their household. Respondents with primary and secondary education often considered these facilities necessary. Forest playgrounds are primarily intended to support informal education, allow for creative, free play, increase the bond with nature, and thus stimulate children to increase their knowledge of the natural world [73]. Perhaps playgrounds in the forest are also a stimulant for older users wanting to become more involved in learning about the natural world through informal education. Our research showed that the need for specialized recreational trails in forests, such as bike paths and nature trails, was more often opted for by residents of rural areas and small and medium-sized cities. This is probably related to the fact that the most common forms of recreation in less urbanized areas, especially rural ones, as established by Florkowski and Us [74], are walking and cycling. Bike paths in large cities are already the norm, a common feature of the metropolitan landscape. Bicycling is gaining prominence as one of the main elements of cities’ transportation strategies that focus on sustainable mobility. There are still gaps in bicycle infrastructure in less urbanized areas, which may resonate precisely in the preferences of residents in such areas. To a greater extent, bicycle paths are also preferred.

We observed few differences when it came to the influence of gender on the views of respondents. It turns out that women were more likely to opt for educational paths. In general, women are more likely to pay attention to the content of interpretive signs on educational paths [75]. It is certain that women are more eager to acquire new knowledge, reaching for books or magazines more often than men, and from an early age [76]. Researchers consider historical and cultural background to be the reason for this tendency. In our study, men, on the other hand, were more likely to show a need for parking and parking spaces. In Poland, three out of four men and slightly more than half of women (56%) hold a driver’s license [77], so it is not surprising that it is the main car users who are opting for increased development of infrastructure that allows them to get close to the forest in safety and comfort. It seems that the most elite element of recreational infrastructure in the forests are viewpoints, most often indicated as needed by people with a college education and without children, whose social status is most likely to be high. A person who is already at the top of Maslow’s pyramid of needs wants to surround themselves with beautiful things and experience beautiful, interesting things.

4.3. Demand for Recreational Land Equipment

For recreation, an undisturbed forest environment is important for producing the most valuable and restorative experiences that allow for relaxation. A common problem in some parts of the world, as well as in Poland, is high forest litter, most often occurring near urbanized areas where forest recreation is very important. Studies by Janeczko [78] and Janeczko and Woźnicka [60] show that land litter is one of the most important factors causing discomfort among tourists and forest visitors and thus lowering the assessment of landscape attractiveness. Therefore, it is not surprising that trash garbage cans or toilets—welfare facilities—were mentioned among the most-needed facilities. The popularity of recreational facilities is because basically every form of recreation, both active and passive, carried out in forests requires amenities that allow a moment to breathe or provide an opportunity to contemplate the forest landscape—hence, in the opinion of forest users, such facilities as canopies, benches, and tables are also perceived as very necessary in forests. Also, research conducted in Sweden by Frick et al. [45] shows that infrastructure for contemplative and social activities is highly valued. Research conducted in the UK by Chastin et al. [79] shows, among other things, that the presence of rest facilities in forests increases motivation for recreation and confidence to venture further [69]. Another study [80], also conducted in the UK, found that the seating areas and amenities, such as restrooms, make it possible, especially for the elderly, to enjoy public green spaces [80]. For the most part, the rationale behind the survey respondents’ choices is the dominant way of spending time in the forest [81]. Given the dominant form of recreation, which is walking, elements that enable free movement and orientation in the area, i.e., all elements related to landmarking (signposts, information boards), are of great importance to visitors. Walks on educational trails were much less preferred. Hence, educational devices such as interpretative signs, posters, etc., usually accompanying educational paths, were only secondarily perceived as needed in forest areas.

4.4. Determinants of Respondents’ Preferences for Forest Recreational Facilities

Regarding recreational infrastructure elements, views on the importance of recreational facilities in forests also differed due to the socio-demographic characteristics analyzed. Our research confirms that how people spend their time in the forest implies the need for a certain assortment of recreational facilities. We found, for example, that sports equipment was almost twice as often indicated as needed in the forest by young users. Research conducted in Norway by Fjørtoft and Sageie [73] shows that young people use the forest primarily as a place to engage in sports, and therefore showed a greater preference for sports infrastructure, such as fitness and running trails and biking trails, than adults, who, in turn, perceived sports infrastructure in the forest as more annoying. In our survey, sports facilities were more often indicated as needed by respondents living more than 10 km from the forest and those visiting the forest occasionally. Visitors to the forest occasionally were also more likely to express the view that forests should be retrofitted with social and living facilities. This is an important observation because it suggests that retrofitting forests with sports or social and living facilities could be a stimulus to increase outdoor physical activity for people living a little farther from the forest, as well as those who do not use the forest very often. It seems that this type of infrastructure could encourage people to visit the forests more often. An interesting cautionary note is how respondents’ views on the recreational infrastructure needed in forests are determined by the distance of where they live from the forest. For example, a study in Portugal’s Leiria National Forest found that people living near forests are more likely to invest in developing recreational infrastructure [82]. Our research shows that people’s views on only some of the recreational facilities are determined by the distance of residence from the forests, this is true for protective equipment and playground equipment. It turns out that people who live closer to the forest were less likely to postulate the introduction of protective devices. Probably, for this group of respondents, the forest was the primary place for recreation, many owners of gardens on forest plots borrow the forest landscape. Hence, they do not see the need to introduce artificial elements into the landscape, such as barriers or security barriers, and they do not want to fence off the forest. On the other hand, those living close to the forest also present a somewhat selfish, but also pragmatic approach to locating new recreational infrastructure facilities in the forest, such as playground equipment. Playgrounds, as a rule, generate more noise and the accumulation of tourist participants, which may be contrary to the interests of local groups of forest-area residents. Playground equipment was more often considered necessary by young people in the 31–40 age range and those with children. Those living within 3 km of the forest were instead more likely to indicate the need for informational devices. Visitors generally value informational signs; they help enhance the recreational experience [33]. De Meo et al. [33] believe that educational posters about forest ecosystems are also valued by visitors, helping to educate the public about sustainable forest use. However, our research does not confirm this. In addition, we found that they are perceived as unnecessary primarily by users with primary education.

5. Conclusions

The main impetus for the development of recreation in contact with nature is to improve recreational opportunities in the forests, as well as to facilitate physical activities that improve health. Understanding the preferences of citizens and determining the factors that determine their opinions is important for forest management, as this enables the adoption of certain forest-management strategies, particularly in terms of infrastructure investment. Careful planning and management of space is key to the sustainable development of a place. It allows for better protection of the natural environment while promoting physical activity and enhancing the experience of forest visitors. Forest recreational management enhances the social functions of the forest, helping to mitigate potential conflicts with other forest functions. According to our research, key elements of forest recreational development include well-designed trails, primarily biking and hiking. The demand for recreational infrastructure was determined mainly by the age and number of children they had, as well as where the respondents lived. These three key variables interest many politicians, policymakers, and forest managers today. Many documents show conclusively that more and more people are living in cities, fewer children are being born, and the proportion of elderly people in society is increasing, which will affect the forest recreation model in the future. On the other hand, mainly due to widespread urbanization, more and more people are living in the vicinity of the forest. As our research shows, the expectations of this group of forest users are clearly different from those of the rest of the leisure group. Hence, it is necessary to monitor these preferences and try to remodel existing forest management so that in the future it will definitely be more responsive to people’s needs and encourage them to be active in nature. The results of our study provide the following practical implications:

- Comprehensive strategies and plans are needed to expand recreational infrastructure in forests to encourage and support physical activity in nature, promoting the use of forests so that the public health benefits of contact with nature are fully utilized.

- These days, forest ecosystem services that provide health benefits are gaining in importance. Supporting these services can be the infrastructure design enabling physical activity—it is also important to promote infrastructure solutions supporting forest landscapes’ therapeutic role. Visitors should be encouraged to enjoy both physical and mental recreation. Creating infrastructure solutions to restore involuntary attention (Attention Restoration Theory) supports the restorative, healing potential of the forest landscape. In this context, special attention should be paid to the forest’s coastal zone, where forest stands meet other natural ecosystems—such as reservoirs-water, meadows and other open forestless areas.

- Recreational development of the forest should take into account the needs and expectations of visitors. Facilities are needed for a wide range of visitors, hikers, cyclists, and casual recreational walkers. Especially in the planning and design of recreational infrastructure, it is important to take into account the anticipated demographic trends and to give preference to solutions that are friendly to people with disabilities, in line with the expectations of seniors. Removing barriers to seniors’ access to forest land and strategic infrastructure planning can increase the effectiveness of recreational facilities in meeting public demand for nature-based recreation.

- In the vicinity of small and medium-sized cities and in rural areas, forests should be retrofitted with a network of bicycle and educational trails. Bikeways in forested areas can help integrate and improve the functioning of existing local bikeway networks, supporting active transportation and significantly increasing physical activity in the population. In the vicinity of large cities, existing recreational routes, especially walking paths, should be equipped with rest and welfare facilities, thereby increasing access and encouraging seniors to enjoy nature-based recreation.

- A form of encouraging young people to engage in outdoor activities in the forest can be sports infrastructure. Equipping forests with sports or social and living facilities can be a stimulus for increasing outdoor physical activity of people, especially those living a little farther from the forest and those who do not use the forest very often. It can be a form of promoting an active lifestyle, counteracting the phenomenon of nature deficit, and encouraging contact with nature.

6. Limitation

The information collected for this study comes from forest land users visiting forests in central Poland for tourism and recreation. This is not a representative sample of Polish residents. We have not conducted a nationwide survey that would guarantee that the sample of respondents would be representative. Nevertheless, we made every effort to reliably present the needs and expectations with regard to the recreational infrastructure of people visiting forests. In our study, we used an online survey questionnaire. This is a common social research tool that can be used to determine people’s expectations and preferences. Perhaps other research tools and techniques (e.g., interviews, focus studies) would have provided more insight into the motives behind the indications and choices made by our respondents. However, we conducted the research during the pandemic period, with limited opportunity for direct contact with respondents. The research design and construction of the questionnaire involved consultation with a sociologist and a statistician. The essential research was preceded by a pilot study to eliminate technical and organizational errors. We used an online survey, which eliminated the problem of not answering any of the questions. Moving on to the next question required answering the previous question. We are aware that an online survey is also fraught with certain risks—the inability to check the age of the person answering, or the low turnout of seniors. According to the CBOS report [83], almost half of Poles aged 55–64 and three-quarters of the oldest (aged 65 and over) remain offline. We realize that the results we obtained using a different tool may not always give similar results, as the study by Tahvanainen et al. [84] showed significant differences in respondents’ opinions depending on the survey technique adopted (descriptive-picture questions). Future research on assessing the need for recreational infrastructure in forests would need to focus on at least three aspects:

- We studied the influence of the distance of the place of residence from the forest on people’s opinions regarding recreational infrastructure. However, it would be worthwhile to determine how the housing conditions in which respondents live influence their opinion regarding forest recreational development. However, it seems that the needs for recreational infrastructure in the forest reported by owners of houses or bungalows/second homes in the vicinity of the forest may be different from the needs expressed by residents of multi-family houses, sometimes also built close to forests.

- Based on our research, there is a clear trend of treating forests in the vicinity of cities as if they were extensive park spaces (paths, rest points, restrooms, recreational glades, etc.). In future research, it would be worthwhile to see which elements of recreational infrastructure are preferred in urban parks and which in forest areas. Do urban residents understand the need for the different saturation of recreational infrastructure in parks and forests?

- Not much is known about the nature of recreational roads in forests. Our research does not provide information on the recommended length of recreational routes, the preferred surface, the number of resting places per km of route, etc., as well as the capacity of the route. It seems that in future studies, with the help of photographic material or graphic diagrams, a set of practical implications in this regard could be completed

- We still do not know much about the possibility of the use and importance of recreational infrastructure for the rapidly developing forest areas, such as forest bathing, meditation, yoga, etc. Can recreational infrastructure support forest therapy? To what extent?

These are just a few of the research threads that can be taken up in the future to more fully, more accurately answer the questions posed in the title of our manuscript.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.J., J.B. and M.W.; methodology, E.J., J.B., M.W., K.J., S.Z. and K.U.-B.; validation, E.J. and, J.B.; formal analysis, J.B., E.J., K.J. and A.B.; investigation, E.J., J.B., M.W. and S.Z.; resources, K.J., K.U.-B. and S.Z. data curation, E.J. and J.B.; writing—original draft preparation, E.J.; writing—review and editing, M.W. and A.B.; visualization, K.U.-B.; supervision, K.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in full compliance with the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR 679/2016) and the Declaration of Helsinki (2000). Due to the anonymous nature of data collection and absence of personal identifiers, formal ethics committee approval was not required.

Informed Consent Statement

The surveys conducted are entirely voluntary surveys, with no data to identify respondents.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Logit Models of Recreational Infrastructure’s Importance in Forest

| Infrastructure | Variable | Coefficient | p Value | Statistics t | Wald’s χ2 | Odds Ratio |

| Camping and tent fields | intercept | −2.026 | 0.000 | −7.00 | 48.95 | 0.13 |

| men | 0.332 | 0.017 | 2.39 | 5.73 | 1.39 | |

| daily | 0.179 | 0.440 | 0.77 | 0.60 | 1.20 | |

| several times a week | 0.127 | 0.414 | 0.82 | 0.67 | 1.14 | |

| <30 years | 0.613 | 0.001 | 3.49 | 12.17 | 1.85 | |

| village | 0.088 | 0.577 | 0.56 | 0.31 | 1.09 | |

| big-city residents | 0.348 | 0.093 | 1.68 | 2.83 | 1.42 | |

| primary | −0.164 | 0.671 | −0.43 | 0.18 | 0.85 | |

| higher education | −0.147 | 0.323 | −0.99 | 0.98 | 0.86 | |

| families without children | 0.344 | 0.042 | 2.04 | 4.16 | 1.41 | |

| satisfied | 0.124 | 0.438 | 0.78 | 0.60 | 1.13 | |

| up to 3 km | 0.036 | 0.877 | 0.16 | 0.02 | 1.04 | |

| 3–6 km | −0.029 | 0.907 | −0.12 | 0.01 | 0.97 | |

| 6–10 km | −0.516 | 0.089 | −1.70 | 2.89 | 0.60 | |

| Recreational walking paths | intercept | 0.493 | 0.040 | 2.06 | 4.24 | 1.64 |

| men | 0.121 | 0.297 | 1.04 | 1.09 | 1.13 | |

| daily | 0.278 | 0.173 | 1.36 | 1.86 | 1.32 | |

| several times a week | 0.063 | 0.621 | 0.49 | 0.24 | 1.07 | |

| <30 years | 0.225 | 0.158 | 1.41 | 2.00 | 1.25 | |

| village | 0.198 | 0.134 | 1.50 | 2.25 | 1.22 | |

| big-city residents | 0.224 | 0.214 | 1.24 | 1.55 | 1.25 | |

| primary | 0.261 | 0.458 | 0.74 | 0.55 | 1.30 | |

| higher education | −0.070 | 0.586 | −0.54 | 0.30 | 0.93 | |

| families without children | −0.084 | 0.561 | −0.58 | 0.34 | 0.92 | |

| satisfied | 0.049 | 0.719 | 0.36 | 0.13 | 1.05 | |

| up to 3 km | −0.012 | 0.954 | −0.06 | 0.00 | 0.99 | |

| 3–6 km | −0.158 | 0.452 | −0.75 | 0.57 | 0.85 | |

| 6–10 km | −0.109 | 0.645 | −0.46 | 0.21 | 0.90 | |

| Playgrounds | intercept | −2.797 | 0.000 | −5.46 | 29.79 | 0.06 |

| men z | −0.148 | 0.535 | −0.62 | 0.39 | 0.86 | |

| daily | −0.182 | 0.659 | −0.44 | 0.19 | 0.83 | |

| several times a week | −0.473 | 0.074 | −1.79 | 3.19 | 0.62 | |

| village | −0.200 | 0.475 | −0.71 | 0.51 | 0.82 | |

| big-city residents | 0.461 | 0.172 | 1.37 | 1.87 | 1.59 | |

| primary | 0.325 | 0.623 | 0.49 | 0.24 | 1.38 | |

| higher education | −0.558 | 0.029 | −2.18 | 4.77 | 0.57 | |

| satisfied | −0.130 | 0.635 | −0.48 | 0.23 | 0.88 | |

| up to 3 km | 0.181 | 0.661 | 0.44 | 0.19 | 1.20 | |

| 3–6 km | 0.529 | 0.183 | 1.33 | 1.77 | 1.70 | |

| 6–10 km | −0.173 | 0.738 | −0.34 | 0.11 | 0.84 | |

| >50 years | −3.201 | 0.002 | −3.15 | 9.95 | 0.04 | |

| families with children | 1.028 | 0.000 | 3.66 | 13.39 | 2.80 | |

| Bicycle paths | intercept | −0.889 | 0.000 | −4.91 | 24.14 | 0.41 |

| men | 0.124 | 0.268 | 1.11 | 1.23 | 1.13 | |

| higher education | 0.212 | 0.082 | 1.74 | 3.02 | 1.24 | |

| >10 km | 0.248 | 0.137 | 1.49 | 2.21 | 1.28 | |

| families without children | 0.019 | 0.872 | 0.16 | 0.03 | 1.02 | |

| village | 0.346 | 0.003 | 2.96 | 8.75 | 1.41 | |

| several times a week | 0.088 | 0.476 | 0.71 | 0.51 | 1.09 | |

| satisfied | 0.071 | 0.587 | 0.54 | 0.30 | 1.07 | |

| >50 years | −0.273 | 0.084 | −1.73 | 3.00 | 0.76 | |

| daily | −0.181 | 0.338 | −0.96 | 0.92 | 0.83 | |

| Paths for horse back riding | intercept | −2.133 | 0.000 | −7.14 | 50.94 | 0.12 |

| men | 0.044 | 0.825 | 0.22 | 0.05 | 1.05 | |

| higher education | −0.267 | 0.203 | −1.27 | 1.62 | 0.77 | |

| >10 km | 0.003 | 0.986 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 1.00 | |

| families without children | −0.209 | 0.324 | −0.99 | 0.97 | 0.81 | |

| village | 0.174 | 0.392 | 0.86 | 0.73 | 1.19 | |

| several times a week | 0.222 | 0.321 | 0.99 | 0.98 | 1.25 | |

| satisfied | −0.377 | 0.081 | −1.74 | 3.04 | 0.69 | |

| >50 years | −0.433 | 0.142 | −1.47 | 2.16 | 0.65 | |

| daily | 0.393 | 0.208 | 1.26 | 1.59 | 1.48 | |

| Parking lots and parking spaces | intercept | −1.450 | 0.000 | −6.53 | 42.66 | 0.23 |

| men | 0.355 | 0.010 | 2.57 | 6.62 | 1.43 | |

| higher education | 0.115 | 0.440 | 0.77 | 0.60 | 1.12 | |

| >10 km | 0.067 | 0.737 | 0.34 | 0.11 | 1.07 | |

| families without children | −0.008 | 0.963 | −0.05 | 0.00 | 0.99 | |

| village | 0.096 | 0.505 | 0.67 | 0.45 | 1.10 | |

| several times a week | −0.217 | 0.145 | −1.46 | 2.13 | 0.80 | |

| satisfied | −0.129 | 0.413 | −0.82 | 0.67 | 0.88 | |

| >50 years | 0.441 | 0.012 | 2.51 | 6.28 | 1.55 | |

| daily | −0.399 | 0.089 | −1.70 | 2.90 | 0.67 | |

| <30 years | −0.345 | 0.083 | −1.74 | 3.01 | 0.71 | |

| Educational paths | intercept | −1.467 | 0.000 | −6.83 | 46.68 | 0.23 |

| higher education | 0.035 | 0.813 | 0.24 | 0.06 | 1.04 | |

| >10 km | −0.050 | 0.822 | −0.22 | 0.05 | 0.95 | |

| families without children | 0.190 | 0.266 | 1.11 | 1.24 | 1.21 | |

| several times a week | 0.021 | 0.892 | 0.14 | 0.02 | 1.02 | |

| satisfied | −0.123 | 0.431 | −0.79 | 0.62 | 0.88 | |

| >50 years | −0.163 | 0.409 | −0.83 | 0.68 | 0.85 | |

| daily | 0.025 | 0.910 | 0.11 | 0.01 | 1.03 | |

| <30 years | −0.258 | 0.177 | −1.35 | 1.82 | 0.77 | |

| women | 0.421 | 0.002 | 3.09 | 9.54 | 1.52 | |

| big-city residents | −0.429 | 0.054 | −1.93 | 3.73 | 0.65 | |

| Rest and picnic areas | intercept | −1.532 | 0.000 | −6.32 | 39.89 | 0.22 |

| higher education | 0.102 | 0.469 | 0.72 | 0.52 | 1.11 | |

| >10 km | −0.400 | 0.057 | −1.90 | 3.62 | 0.67 | |

| several times a week | −0.199 | 0.153 | −1.43 | 2.05 | 0.82 | |

| satisfied | −0.018 | 0.906 | −0.12 | 0.01 | 0.98 | |

| >50 years | 0.011 | 0.955 | 0.06 | 0.00 | 1.01 | |

| daily | −0.374 | 0.088 | −1.71 | 2.91 | 0.69 | |

| <30 years | 0.463 | 0.009 | 2.60 | 6.75 | 1.59 | |

| women | 0.187 | 0.144 | 1.46 | 2.14 | 1.21 | |

| big-city residents | 0.293 | 0.112 | 1.59 | 2.52 | 1.34 | |

| families with children | 0.346 | 0.037 | 2.09 | 4.36 | 1.41 | |

| Centers/points for environmental education (16.9) | intercept | −2.909 | 0.000 | −8.12 | 65.92 | 0.05 |

| higher education | 0.004 | 0.977 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 1.00 | |

| >10 km | 0.086 | 0.766 | 0.30 | 0.09 | 1.09 | |

| several times a week | 0.030 | 0.887 | 0.14 | 0.02 | 1.03 | |

| satisfied | 0.253 | 0.277 | 1.09 | 1.18 | 1.29 | |

| >50 years | −0.463 | 0.110 | −1.60 | 2.56 | 0.63 | |

| daily | 0.082 | 0.795 | 0.26 | 0.07 | 1.09 | |

| <30 years | −0.026 | 0.921 | −0.10 | 0.01 | 0.97 | |

| women | 0.348 | 0.067 | 1.83 | 3.36 | 1.42 | |

| big-city residents | 0.096 | 0.727 | 0.35 | 0.12 | 1.10 | |

| families with children | 0.378 | 0.123 | 1.54 | 2.39 | 1.46 | |

| Viewpoints | intercept | −1.389 | 0.000 | −6.72 | 45.13 | 0.25 |

| higher education | 0.231 | 0.075 | 1.78 | 3.17 | 1.26 | |

| several times a week | 0.105 | 0.432 | 0.79 | 0.62 | 1.11 | |

| satisfied | 0.280 | 0.050 | 1.96 | 3.84 | 1.32 | |

| >50 years | −0.001 | 0.978 | −0.03 | 0.00 | 1.00 | |

| daily | 0.158 | 0.436 | 0.78 | 0.61 | 1.17 | |

| <30 years | 0.145 | 0.360 | 0.91 | 0.84 | 1.16 | |

| women | −0.195 | 0.103 | −1.63 | 2.66 | 0.82 | |

| big-city residents | −0.116 | 0.503 | −0.67 | 0.45 | 0.89 | |

| families without children | 0.465 | 0.002 | 3.16 | 10.00 | 1.59 | |

| up to 3 km | −0.011 | 0.947 | −0.07 | 0.00 | 0.99 | |

| 3–6 km | −0.047 | 0.789 | −0.27 | 0.07 | 0.95 | |

| Resting points along recreational routes | intercept | −1.600 | 0.000 | −7.57 | 57.37 | 0.20 |

| higher education | 0.017 | 0.908 | 0.12 | 0.01 | 1.02 | |

| several times a week | 0.184 | 0.202 | 1.28 | 1.63 | 1.20 | |

| satisfied | 0.047 | 0.762 | 0.30 | 0.09 | 1.05 | |

| >50 years | 0.379 | 0.029 | 2.18 | 4.75 | 1.46 | |

| daily | 0.092 | 0.676 | 0.42 | 0.17 | 1.10 | |

| women | 0.055 | 0.676 | 0.42 | 0.17 | 1.06 | |

| big city residents | 0.373 | 0.035 | 2.11 | 4.45 | 1.45 | |

| 3–6 km | −0.032 | 0.837 | −0.21 | 0.04 | 0.97 | |

| families with children | −0.014 | 0.926 | −0.09 | 0.01 | 0.99 | |

| Significant variables in the model are marked in bold. | ||||||

Appendix A.2

Figure A1.

Predictors of preference for (a) camping and tenting sites in forests; (b) playgrounds; (c) bicycle paths in forests; (d) car parks in forests; (e) educational trails in forests; (f) recreational fields and picnic sites; (g) viewpoints in forests; and (h) rest points along routes.

Appendix A.3. Logit Models of Recreational Facilities’ Importance in Forest

| Facilities | Variable | Coefficient | p Value | Statistics t | Wald’s χ2 | Odds Ratio |

| Welfare | intercept | −0.028 | 0.886 | −0.14 | 0.02 | 0.97 |

| men | −0.071 | 0.514 | −0.65 | 0.43 | 0.93 | |

| several times a week | −0.098 | 0.366 | −0.90 | 0.82 | 0.91 | |

| <30 years | 0.245 | 0.098 | 1.66 | 2.74 | 1.28 | |

| big-city residents | 0.017 | 0.916 | 0.11 | 0.01 | 1.02 | |

| higher education | 0.033 | 0.782 | 0.28 | 0.08 | 1.03 | |

| satisfied | −0.115 | 0.361 | −0.91 | 0.83 | 0.89 | |

| >10 km | 0.165 | 0.329 | 0.98 | 0.95 | 1.18 | |

| with children | 0.278 | 0.042 | 2.03 | 4.13 | 1.32 | |

| Sports | intercept | −1.933 | 0.000 | −9.35 | 87.35 | 0.14 |

| men | 0.038 | 0.794 | 0.26 | 0.07 | 1.04 | |

| several times a week | 0.299 | 0.045 | 2.01 | 4.03 | 1.35 | |

| <30 years | 0.602 | 0.002 | 3.13 | 9.77 | 1.83 | |

| big-city residents | −0.144 | 0.535 | −0.62 | 0.38 | 0.87 | |

| higher education | −0.045 | 0.772 | −0.29 | 0.08 | 0.96 | |

| without children | 0.071 | 0.705 | 0.38 | 0.14 | 1.07 | |

| satisfied | 0.037 | 0.825 | 0.22 | 0.05 | 1.04 | |

| >10 km | −0.715 | 0.012 | −2.50 | 6.27 | 0.49 | |

| Recreational | intercept | 0.084 | 0.665 | 0.43 | 0.19 | 1.09 |

| men | 0.055 | 0.614 | 0.50 | 0.25 | 1.06 | |

| several times a week | 0.011 | 0.915 | 0.11 | 0.01 | 1.01 | |

| <30 years | −0.096 | 0.517 | −0.65 | 0.42 | 0.91 | |

| big-city residents | 0.274 | 0.088 | 1.71 | 2.91 | 1.32 | |

| higher education | −0.113 | 0.333 | −0.97 | 0.94 | 0.89 | |

| satisfied | −0.046 | 0.720 | −0.36 | 0.13 | 0.96 | |

| >10 km | −0.344 | 0.044 | −2.02 | 4.06 | 0.71 | |

| with children | −0.192 | 0.162 | −1.40 | 1.96 | 0.83 | |

| Educational | intercept | −1.134 | 0.000 | −4.92 | 24.18 | 0.32 |

| men | 0.066 | 0.611 | 0.51 | 0.26 | 1.07 | |

| several times a week | 0.017 | 0.898 | 0.13 | 0.02 | 1.02 | |

| <30 years | −0.010 | 0.954 | −0.06 | 0.00 | 0.99 | |

| big-city residents | 0.082 | 0.651 | 0.45 | 0.21 | 1.09 | |

| satisfied | −0.021 | 0.893 | −0.13 | 0.02 | 0.98 | |

| with children i | −0.131 | 0.415 | −0.82 | 0.66 | 0.88 | |

| primary | −1.152 | 0.030 | −2.17 | 4.70 | 0.32 | |

| up to 3 km | 0.009 | 0.947 | 0.07 | 0.00 | 1.01 | |

| >50 l | −0.201 | 0.288 | −1.06 | 1.13 | 0.82 | |

| Playground equipment | intercept | −2.408 | 0.000 | −8.87 | 78.75 | 0.09 |

| men | −0.258 | 0.176 | −1.35 | 1.83 | 0.77 | |

| several times a week | 0.084 | 0.662 | 0.44 | 0.19 | 1.09 | |

| big-city residents | −0.237 | 0.393 | −0.85 | 0.73 | 0.79 | |

| satisfied | 0.019 | 0.928 | 0.09 | 0.01 | 1.02 | |

| primary | 0.784 | 0.093 | 1.68 | 2.83 | 2.19 | |

| up to 3 km | −0.652 | 0.001 | −3.26 | 10.60 | 0.52 | |

| 30–40 years | 0.600 | 0.002 | 3.06 | 9.38 | 1.82 | |

| 1–2 children | 0.443 | 0.024 | 2.26 | 5.09 | 1.56 | |

| Information | intercept | −0.706 | 0.000 | −4.30 | 18.47 | 0.49 |

| men | −0.170 | 0.121 | −1.55 | 2.40 | 0.84 | |

| several times a week | 0.039 | 0.723 | 0.35 | 0.13 | 1.04 | |

| big-city residents | 0.273 | 0.079 | 1.76 | 3.09 | 1.31 | |

| satisfied | 0.201 | 0.117 | 1.57 | 2.46 | 1.22 | |

| up to 3 km | 0.257 | 0.023 | 2.27 | 5.17 | 1.29 | |

| 30–40 years | −0.285 | 0.019 | −2.35 | 5.51 | 0.75 | |

| higher education | 0.297 | 0.013 | 2.47 | 6.12 | 1.35 | |

| without children | 0.240 | 0.035 | 2.11 | 4.44 | 1.27 | |

| Security | intercept | −1.600 | 0.000 | −7.47 | 55.73 | 0.20 |

| men | 0.359 | 0.016 | 2.41 | 5.80 | 1.43 | |

| several times a week | 0.069 | 0.639 | 0.47 | 0.22 | 1.07 | |

| big-city residents | −0.302 | 0.173 | −1.36 | 1.86 | 0.74 | |

| satisfied | −0.119 | 0.480 | −0.71 | 0.50 | 0.89 | |

| up to 3 km | −0.244 | 0.106 | −1.62 | 2.62 | 0.78 | |

| 30–40 years | 0.207 | 0.192 | 1.30 | 1.70 | 1.23 | |

| higher education | −0.080 | 0.614 | −0.50 | 0.25 | 0.92 | |

| without children | −0.124 | 0.425 | −0.80 | 0.64 | 0.88 | |

| Significant variables in the model are marked in bold. | ||||||

Appendix A.4

Figure A2.

Predictors of preference for (a) sports facilities in forests; (b) social and living facilities; (c) playgrounds in forests; (d) environmental education points; (e) information devices in forests; and (f) protective devices in forests.

References

- Konijnendijk, C.C. A decade of urban forestry in Europe. For. Policy Econ. 2003, 5, 173–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, L. Exploring underpinnings of forest conflicts: A study of forest values and beliefs in the general public and among private forest owners in Sweden. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2012, 25, 1102–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bang, K.-S.; Kim, S.; Song, M.K.; Kang, K.I.; Jeong, Y. The Effects of a Health Promotion Program Using Urban Forests and Nursing Student Mentors on the Perceived and Psychological Health of Elementary School Children in Vulnerable Populations. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janeczko, E.; Banaś, J.; Woźnicka, M.; Zięba, S.; Banaś, K.U.; Janeczko, K.; Fialova, J. Sociocultural Profile as a Predictor of Perceived Importance of Forest Ecosystem Services: A Case Study from Poland. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nastran, M.; Pintar, M.; Železnikar, Š.; Cvejić, R. Stakeholders’ Perceptions on the Role of Urban Green Infrastructure in Providing Ecosystem Services for Human Well-Being. Land 2022, 11, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janeczko, E.; Czyżyk, K.; Woźnicka, M.; Dudek, T.; Fialova, J.; Korcz, N. The Importance of Forest Management in Psychological Restoration: Exploring the Effects of Landscape Change in a Suburban Forest. Land 2024, 13, 1439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-C.; Tsai, F.C.; Tsai, M.-J.; Liu, W.-Y. Recreational Visit to Suburban Forests during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Case Study of Taiwan. Forests 2022, 13, 1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baranowska, M.; Koprowicz, A.; Korzeniewicz, R. Społeczne znaczenie lasu–raport z badań pilotażowych prowadzonych w okresie pandemii. Sylwan 2021, 165, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulfone, T.C.; Malekinejad, M.; Rutherford, G.W.; Razani, N. Outdoor Transmission of SARS-CoV-2 and Other Respiratory Viruses: A Systematic Review. J. Infect. Dis. 2021, 223, 550–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, H.; Wu, Z. The Role of Single Landscape Elements in Enhancing Landscape Aesthetics and the Sustainable Tourism Experience: A Case Study of Leisure Furniture. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wielgus, K. Preservation and Formation of Engineering Works in the Landscape—The Scope of the Issues; Landscape Architecture and Urban Planning; Cracow University of Technology: Cracow, Poland, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Communication from the Commission Agenda for a Sustainable and Competitive European Tourism. Document 52007DC0621. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/PL/TXT/?uri=celex%3A52007DC0621 (accessed on 16 March 2025).

- Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions Europe, the World’s No 1 Tourist Destination—A New Political Framework for Tourism in Europe. Document 52010DC0352. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/PL/ALL/?uri=CELEX%3A52010DC0352 (accessed on 16 March 2025).

- Communication from the Commission—A Renewed EU Tourism Policy-Towards a Stronger Partnership for European Tourism. Document 52006DC0134. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/pl/HIS/?uri=CELEX:52006DC0134 (accessed on 16 March 2025).

- A New EU Forest Strategy for 2030–Sustainable Forest Management in Europe. Available online: https://oeil.secure.europarl.europa.eu/oeil/en/procedure-file?reference=2022/2016(INI) (accessed on 16 March 2025).

- Wilkes-Allemann, J.; Pütz, M.; Hirschi, C. Governance of Forest Recreation in Urban Areas: Analysing the role of stakeholders and institutions using the institutional analysis and development framework. Environ. Pol. Gov. 2015, 25, 139–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnberger, A. Recreation Use of Urban Forests: An Inter-Area Comparison. Urban For. Urban Green. 2006, 4, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janeczko, E.; Wójcik, R.; Kędziora, W.; Janeczko, K.; Woźnicka, M. Organised Physical Activity in the Forests of the Warsaw and Tricity Agglomerations, Poland. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinbrenner, H.; Breithut, J.; Hebermehl, W.; Kaufmann, A.; Klinger, T.; Palm, T.; Wirth, K. “The Forest Has Become Our New Living Room”–The Critical Importance of Urban Forests During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Front. For. Glob. Change 2021, 4, 672909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, R. Is physical activity in natural environments better for mental health than physical activity in other environments? Soc. Sci. Med. 2013, 91, 130–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowler, D.E.; Buyung-Ali, L.M.; Knight, T.M.; Pullin, A.S. A systematic review of evidence for the added benefits to health of exposure to natural environments. BMC Public Health 2010, 10, 456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaczynski, A.T.; Besenyi, G.M.; Stanis, S.A.; Koohsari, M.J.; Oestman, K.B.; Bergstrom, R.; Potwarka, L.R.; Reis, R.S. Are park proximity and park features related to park use and park-based physical activity among adults? Variations by multiple socio-demographic characteristics. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2014, 11, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chastin, S.F.; Fitzpatrick, N.; Andrews, M.; DiCroce, N. Determinants of sedentary behavior, motivation, barriers and strategies to reduce sitting time in older women: A qualitative investigation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2014, 11, 773–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oreskovic, N.M.; Perrin, J.M.; Robinson, A.I.; Locascio, J.J.; Blossom, J.; Chen, M.L.; Winickoff, J.P.; Field, A.E.; Green, C.; Goodman, E. Adolescents’ use of the built environment for physical activity. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaczynski, A.T.; Henderson, K.A. Parks and recreation settings and active living: A review of associations with physical activity function and intensity. J. Phys. Act. Health 2008, 5, 619–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, B.; Mackenzie-Stewart, R.; Newton, F.; Haregu, T.; Bauman, A.; Donovan, R.; Mahal, A.; Ewing, M.; Newton, J. A longitudinal study examining uptake of new recreation infrastructure by inactive adults. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2019, 16, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janeczko, E.; Tomusiak, R.; Woźnicka, M.; Janeczko, K. Preferencje społeczne dotyczące biegania jako formy aktywnego spędzania czasu wolnego w lasach. Sylwan 2018, 162, 305–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.; Hu, H.; Sun, B. Elderly Suitability of Park Recreational Space Layout Based on Visual Landscape Evaluation. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahuelhual, L.; Carmona, A.; Lozada, P.; Jaramillo, A.; Aguayo, M. Mapping recreation and ecotourism as a cultural ecosystem service: An application at the local level in Southern Chile. Appl. Geogr. 2013, 40, 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peña, L.; Casado-Arzuaga, I.; Onaindia, M. Mapping recreation supply and demand using an ecological and a social evaluation approach. Ecosyst. Serv. 2015, 13, 108–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vigl, L.E.; Depellegrin, D.; Pereira, P.; de Groot, R.; Tappeiner, U. Mapping the ecosystem service delivery chain: Capacity, flow, and demand pertaining to aesthetic experiences in mountain landscapes. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 574, 422–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kulczyk, S.; Woźniak, E.; Derek, M. Landscape, facilities and visitors: An integrated model of recreational ecosystem services. Ecosyst. Serv. 2018, 31, 491–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Meo, I.; Alfano, A.; Cantiani, M.G.; Paletto, A. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Citizens’ Attitudes and Behaviors in the Use of Peri-Urban Forests: An Experience from Italy. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polityka Leśna Państwa. Dokument Przyjęty Przez Radę Ministrów w Dniu 22 Kwietnia 1997 r. Ministerstwo Ochrony Środowiska Zasobów Naturalnych i Leśnictwa, Warszawa. 1997. Available online: https://www.katowice.lasy.gov.pl/c/document_library/get_file?uuid=506deebb-988d-4665-bcd9-148fcf66ee02&groupId=26676 (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- Crisp, B.R.; Swerissen, H.; Duckett, S.J. Four approaches to capacity building in health: Consequences for measurement and accountability. Health Promot. Int. 2000, 15, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bricker, K.S.; Winter, P.L.; Schultz, J.R. Health, economy, and community: USDA Forest Service managers’ perspectives on sustainable outdoor recreation. Rural Connect. 2010, 5, 38–42. [Google Scholar]

- Selin, S. Operationalizing sustainable recreation across the National Forest System: A qualitative content analysis of six regional strategies. J. Park Recreat. Adm. 2017, 35, 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkes-Allemann, J.; Hanewinkel, M.; Pütz, M. Forest recreation as a governance problem: Four case studies from Switzerland. Eur. J. Forest Res. 2017, 136, 511–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, S.; Tyrväinen, L.; Sievänen, T.; Pröbstl, U.; Simpson, M. Outdoor Recreation and Nature Tourism: A European Perspective. Living Rev. Landscape Res. 2007, 1, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegetschweiler, K.T.; Wartmann, F.M.; Dubernet, I.; Fischer, C.; Hunziker, M. Urban forest usage and perception of ecosystem services—A comparison between teenagers and adults. Urban For. Urban Green 2022, 74, 127624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaligot, R.; Hasler, S.; Chenal, J. National assessment of cultural ecosystem services: Participatory mapping in Switzerland. Ambio 2019, 48, 1219–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-López, B.; Iniesta-Arandia, I.; García-Llorente, M.; Palomo, I.; Casado-Arzuaga, I.; Del Amo, D.G.; Gómez-Baggethun, E.; Oteros-Rozas, E.; Palacios-Agundez, I.; Willaarts, B.; et al. Uncovering Ecosystem Service Bundles through Social Preferences. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e38970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plieninger, T.; Bieling, C.; Ohnesorge, B.; Schaich, H.; Schleyer, C.; Wolff, F. Exploring Futures of Ecosystem Services in Cultural Landscapes through Participatory Scenario Development in the Swabian Alb, Germany. Ecol. Soc. 2013, 18, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riechers, M.; Barkmann, J.; Tscharntke, T. Diverging perceptions by social groups on cultural ecosystem services provided by urban green. Landsc Urban Plan 2018, 175, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frick, J.; Bauer, N.; Lindern, E.; Hunziker, M. What forest is in the light of people’s perceptions and values: Socio-cultural forest monitoring in Switzerland. Geogr. Helv. 2018, 73, 335–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilbe, J.M. Logistic Regression Models; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2009; ISBN 1420075772. [Google Scholar]

- Hosmer, D.; Lemeshow, S. Applied Logistic Regression; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Mandziuk, A.; Fornal-Pieniak, B.; Stangierska, D.; Widera, K.; Bihunova, M.; Arsenio, P.M.R.; Janeczko, E.; Żarska, B.; Parzych, S. Attitudes toward paying for recreation in urban forests: A comparison between Warsaw and Lisbon’s young populations. Forests 2025, 16, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verlič, A.; Arnberger, A.; Japelj, A.; Simončič, P.; Pirnat, J. Perceptions of recreational trail impacts on an urban forest walk: A controlled field experiment. Urban For. Urban Green. 2015, 14, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janeczko, E.; Woźnicka, M.; Tomusiak, R.; Dawidziuk, A.; Kargul-Plewa, D.; Janeczko, K. Preferencje społeczne dotyczące rekreacji w lasach Mazowieckiego Parku Krajobrazowego w roku 2000 i 2012. Sylwan 2017, 161, 422–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fialová, J.; Březina, D.; Žižlavská, N.; Michal, J.; Machar, I. Assessment of Visitor Preferences and Attendance to Singletrails in the Moravian Karst for the Sustainable Development Proposals. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuvonen, M.; Sievänen, T. Outdoor Recreation Statistics 2010. 2011. Available online: https://jukuri.luke.fi/handle/10024/536119 (accessed on 25 March 2025).

- Kikulski, J. Preferencje rekreacyjne i potrzeby zagospodarowania rekreacyjnego lasów nadleśnictw Iławą i Dąbrowa (wyniki pierwszej części badań). Sylwan 2008, 5, 60–71. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, F.S. Landscape managers’ and politicians’ perception of the forest and landscape preferences of the population. For. Landsc. Res. 1993, 1, 79–93. [Google Scholar]

- Reichhart, T.; Arnberger, A. Exploring the influence of speed, social, managerial and physical factors on shared trail preferences using a 3D computer animated choice experiment. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2010, 96, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heagney, E.C.; Rose, J.M.; Ardeshiri, A.; Kovač, M. Optimising recreation services from protected areas–Understanding the role of natural values, built infrastructure and contextual factors. Ecosyst. Serv. 2018, 31, 358–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorwart, C.; Moore, R.; Leung, Y. Visitors’ Perceptions of a Trail Environment and Effects on Experiences: A Model for Nature-Based Recreation Experiences. Leis. Sci. 2010, 32, 33–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gundersen, V.; Vistad, O.I. Public Opinions and Use of Various Types of Recreational Infrastructure in Boreal Forest Settings. Forests 2016, 7, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanowska, A.; Bołdak, A. Relacja człowiek–koń, czyli o znaczeniu koni w życiu człowieka pod względem cywilizacyjnym i indywidualnym. Semin. Poszuk. Nauk. 2022, 43, 107–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janeczko, E.; Woźnicka, M. Zagospodarowanie rekreacyjne lasów Warszawy w kontekście potrzeb i oczekiwań mieszkańców stolicy. Stud. I Mater. Cent. Edukac. Przyr.-Leśnej Rogowie 2009, 11, 131–139. [Google Scholar]

- McCormack, G.R.; Shiell, A. In search of causality: A systematic review of the relationship between the built environment and physical activity among adults. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2011, 8, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaplan, R.; Kaplan, S. The Experience of Nature: A Psychological Perspective; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Hartig, T.; Evans, G.W.; Jamner, L.D.; Davis, D.S.; Gärling, T. Tracking restoration in natural and urban field settings. J. Environ. Psychol. 2003, 23, 109–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]