Abstract

Digital financial literacy, as an upgrade of financial literacy in the digital age, has a non-negligible impact on the income of farm households and the sustainable development of the rural economy. This study aims to investigate the impact of digital financial literacy on rural household income in China and its mechanism of action. Using the sample of rural households in the 2019 China Household Finance Survey (CHFS), which ultimately collected information on 34,643 households and 107,008 household members, the principal component analysis method was used to analyze scores to measure the digital financial literacy level of rural households at three levels—financial knowledge, financial skill application, and digital skills and digital product use—and to perform mechanism analysis and heterogeneity analysis with inclusive finance data from the Digital Finance Research Center of Peking University. The research ideas in this paper are as follows: firstly, to clarify the metric index system of digital financial literacy and calculate to obtain the digital financial literacy score of farmers; secondly, to analyze the direct relationship between digital financial literacy and farmers’ household income; thirdly, to explore the intermediary role of social capital in the process of digital financial literacy affecting farmers’ income; and lastly, to examine the moderating effect of the level of regional financial development. The findings of this study show that digital financial literacy has a significant income-increasing effect on rural residents; mechanism analysis reveals that digital financial literacy increases farmers’ income by increasing social capital, and the level of regional financial development mediates the impact of digital financial literacy on rural household income. From a macro perspective, this article explains the necessity of improving rural households’ digital financial literacy to deepen rural financial services as well as to promote sustainable rural economic development. From a micro perspective, improving rural households’ digital financial literacy and digital financial infrastructure will help optimize their household income levels and income structure. This study provides empirical evidence and decision-making references for increasing farmers’ income, broadening income channels, and improving farmers’ digital human capital to achieve “rural revitalization” in the new era.

1. Introduction

The urban–rural income gap is common worldwide. Since the beginning of the last century, the uneven distribution of income and wealth among economies around the world has generally experienced a process of deterioration, improvement, and further deterioration. Statistics from the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) show that the income gap between countries worldwide has narrowed significantly, but the gap between regions within countries has widened []. In particular, in some developing countries, such as China, the urban–rural income gap accounts for more than 65% of the total income gap and has become a major obstacle to economic development [,]. Notably, the gap between regions is not limited to developing countries. The urban–rural income gap in some developed countries has also widened []. The urban–rural income gap remains at a high level and has large fluctuations [,].

Narrowing the urban–rural income gap is not only necessary for building a harmonious society but also for avoiding falling into the low- and middle-income trap []. China, as one of the most populous countries in the world, faces the challenges of a complex urban–rural dual structure and unbalanced regional development. In fact, China has already injected new vitality into its rural economic development in the past decades through a series of targeted policies, such as the rural revitalization strategy, digital technology empowerment, and industrial integration, which have succeeded in narrowing the urban–rural income gap to a certain extent and promoting the sustainable development of the rural economy. For China’s current situation, to avoid repeating the mistakes of other countries and keeping the urban–rural income gap within a reasonable range on a sustainable basis, it is essential to continue promoting common prosperity for all people. We must not only promote common prosperity in high-quality development, continuously expand and improve the “social wealth cake”, and consolidate the economic foundation of “prosperity” but also resolve the problems of imbalance and inadequacy in development and prevent polarization. With the narrowing of the regional gap, the urban–rural gap, and the income gap as the three main directions, we will strive to improve the balance and coordination of development. To narrow the urban–rural income gap, the key is to increase farmers’ income. Since 2004, the Central Government’s No. 1 Document has focused on “three rural issues” to narrow the urban–rural income gap. The document repeatedly points out that we must persist in increasing farmers’ income, which is the central task of the “three rural issues”. Increasing farmer income is highly important for narrowing the urban–rural income gap.

Financial exclusion, elite capture, mission drift, and other phenomena have long existed in rural areas [,,], restricting the growth of farmers’ income []. In recent years, the development of digital inclusive finance has effectively alleviated financial exclusion by providing lower-cost and more accessible financial services, thereby increasing farmers’ income [], and has also been able to inject impetus into the sustainable development of the rural economy and promote its long-term stable growth. Li et al. [] used the spatial Durbin model and revealed that digitally inclusive finance can significantly promote the growth of farmers’ income. However, Aisaiti G et al. [] noted that due to the widening gap between urban and rural areas, the development of digital inclusive finance has led to increasing exclusion in rural areas, negatively impacting the growth of farmers’ income. Additionally, Wang Yongjing et al. [] empirically reported a nonlinear “U”-shaped relationship between the development of digital inclusive finance and farmers’ income. Only when the development of digital inclusive finance passes the bottom of the “U”-shaped curve will it produce positive effects on farmers’ income. In addition, from the perspective of rural enterprises, Chinese rural enterprises used to use low-cost production factors such as labor and land to enter the low end of the global value chain (GVC). In view of the increasing importance of digital inclusive finance, the pace of the digital transformation of rural enterprises has also accelerated. The digital transformation of enterprises can significantly improve the GVC of enterprises through the effects of innovation coordination, cost reduction, and industrial integration [], and can also enhance the sustainability of the rural economy through technological upgrades and efficiency gains, which ultimately still work to increase the incomes of the micro-entrepreneurs, i.e., the farm households.

Does the rapid development of digital inclusive finance bring about a “digital dividend” or a “digital divide”? The key to its effectiveness lies not only in “blood filling” on the supply side but also in “blood production” on the demand side, that is, the basic conditions and overall literacy of farmers as microeconomic entities []. The key to the effectiveness of digital inclusive finance lies in constructing digital infrastructure and providing digital inclusive financial products and services, as well as in mastering digital financial knowledge and using digital inclusive financial products and services []. The latter depends on the digital financial literacy of the farmers themselves. In other words, the ultimate target of digital inclusive finance is microsubjects, that is, individual farmers. Therefore, as a prerequisite for the effective use of digital financial services [], farmers must develop digital financial literacy as the key to effective digital inclusive finance and to promoting income growth. In contrast, the knowledge and usage gaps formed by the differences in farmers’ digital financial knowledge acquisition and digital financial product usage capabilities exacerbate the digital divide and inhibit the income increase effect []. The widening of such disparities not only affects short-term income growth but may also pose challenges to the sustainable development of the rural economy.

At present, digital financial literacy is a new research perspective. With the advancement of digital transformation, traditional financial literacy’s definition and measurement indicators are no longer sufficient to capture the particularity of financial services in the digital environment. Therefore, some scholars have proposed the need to conceptualize digital financial literacy to further explore ways to obtain digital financial services in the digital context [,,]. Most scholars define digital financial literacy as the knowledge, skills, attitudes, and behavioral habits necessary for individuals to actively use digital devices to conduct financial transactions and use digital financial services [,].

In recent years, scholars have measured digital financial literacy from different perspectives. Kamble et al. [] suggested that digital financial literacy includes three indicators: basic knowledge and skills, mobile payment awareness, and mobile payment proficiency. Lyons et al. [] suggested that the digital financial literacy measurement system should include five dimensions: basic knowledge and skills, awareness, practical behaviour, decision-making, and self-protection. The Alliance for Financial Inclusion (AFI) proposed that the measurement of consumer digital financial literacy should include three aspects: the understanding and ability of digital finance and the ability to use relevant digital financial products independently, understanding the risks related to digital finance and the ability to prevent risks when using digital financial products, and understanding the relevant consumer protection and compensation mechanisms and the ability to prevent risks when using digital finance. Prasad et al. [] proposed four dimensions of digital financial literacy, namely, basic knowledge, practical experience, risk awareness, and financial skills.

Scholars have studied factors affecting farmer income, including government subsidies [], social capital [], agricultural technological progress [], labor transfer [], and other aspects. Studies have also been conducted from the perspective of using the internet and e-commerce platforms, human capital, and digital capabilities. Qi Wenhao et al. [] noted that using the internet and e-commerce platforms can promote the growth of farmers’ income. Zhou Chengqi [] further reported that using the internet can significantly increase the wage income, operating income, and property income of farmer families, but the impact on transfer income is not significant. Liu Chujie et al. [] reported that rural human capital can promote the growth of farmers’ wage income and operating income, whereas Yao Xubing et al. [] noted that this impact varies greatly across regions and is even negative in developed regions. Zang Dunggang et al. [] reported that digital capabilities can significantly increase farmers’ income and that financial literacy plays a partial intermediary role.

As a type of human capital in the digital age [], digital financial literacy can directly affect residents’ access to financial information and the efficiency of using financial tools [,], gradually improving farmers’ ability and likelihood of obtaining income, and also enhance the resilience of the rural economy by optimizing resource allocation and risk management, so as to provide strong support for the sustainable development of the rural economy. However, research on digital financial literacy is still in its infancy, and most studies focus on the definition and measurement of digital financial literacy [], as well as its impact on financial status [], farmers’ credit constraints [], household financial asset allocation [], and family economic common prosperity []. Therefore, studying the impact of digital financial literacy on farmers’ income can enrich research in related fields and is important.

Additionally, according to the research of Yin Zhichao et al. [], the impact of digital financial literacy on farmers’ income is also likely to be heterogeneous. Li et al [] reported that China’s digital financial development has a greater positive effect on low-income families. However, Lei Shini [] reported that the relationship between digital financial development and the income level of low-income families is not significant, and in the early stages of economic development dividends, low-income families must solve the more urgent problem of survival. Therefore, the role of digital finance has not yet become prominent. Therefore, we divided the sample into high-, middle-, and low-income areas to examine the heterogeneity of the impact of digital financial literacy on income among rural households at different income levels. Additionally, according to the approach of Huang Xianfeng [], the sample was divided into eastern, central, and western regions to test the heterogeneity of the impact of rural households’ digital financial literacy on income in regions with different levels of financial development.

This paper chooses China as the research area for analysis for three reasons. First, the urban–rural income gap is particularly serious in China. According to data from the National Bureau of Statistics, in 2018, the per capita disposable income of urban residents in China was 2.69 times that of rural residents, exceeding the internationally recognized income gap warning line. This phenomenon is also very serious in some developing countries. In 2014, the per capita income in rural areas of Vietnam was only 68% of that in urban areas, and the per capita consumption of Indian farmers was only half that of urban residents []. Therefore, studying China’s farmers’ income problems is highly important to countries around the world, especially developing countries. Second, China is a leader in the development of a comprehensive digital framework worldwide. In the past decade, China’s digital finance has developed rapidly and the country has become a global leader [,]. According to the White Paper on China’s Economic Development, China’s digital economy reached 39.2 trillion yuan in 2020, ranking second in the world. Moreover, financial technology and internet finance are developing rapidly in China. The scale of China’s third-party payments, digital currency, and other businesses is far ahead of other countries and regions. Additionally, China attaches great importance to the growth of inclusive finance and solutions to the urban–rural dual structure and has formulated several policies to encourage constructing digital infrastructure in rural areas and motivating financial institutions to provide services groups such as farmers, which not only provides the impetus for an in-depth study of the digital finance framework but also provides valuable lessons for the sustainable development of digital finance globally. Therefore, choosing China as a research object can provide important reference value for most countries in the world, especially developing countries facing the same dilemma.

The research objective of this paper is to explore how digital financial literacy affects the income level of Chinese rural households and the role that social capital plays in this process, as well as to examine the moderating role of the level of regional financial development. Specifically, the purposes of this study are as follows: (1) to quantitatively analyze the direct impact of digital financial literacy on rural household income in China; (2) to explore whether social capital plays a mediating role between digital financial literacy and farmers’ income; (3) to test whether the level of regional financial development moderates the impact of digital financial literacy on rural household income. In addition, the marginal contribution of this paper is threefold: (1) Few studies exist on the impact of digital financial literacy on farmers’ income; therefore, this paper enriches the relevant research in the field of farmer income. (2) According to the basic situation of China’s large and small farmer families, this paper uses micro data to empirically analyze the impact of digital financial literacy on farmers’ income. (3) This paper adopts a mediation effect model and selects social capital as the mediating variable to further verify the impact mechanism of digital financial literacy on farmers’ income.

The rest of this paper is structured as follows: Section 2 presents the research hypotheses and sets up the model, Section 3 selects the variables and conducts descriptive statistics, baseline regression, and robustness tests, Section 4 further reports the results of the endogeneity test, mechanism analysis, and heterogeneity test, and, finally, Section 5 presents the conclusions of this paper and gives the corresponding policy recommendations, and elaborates on the limitations of the present study and provides suggestions for future research.

2. Research Program

2.1. Research Hypothesis

According to Schultz’s human capital theory, the higher the quality of the labor force, the greater labor efficiency; that is, the income return of the labor force is proportional to the human capital input. Compared with urban areas, human capital in rural areas is relatively weak [], the digital ability of farmers is relatively low, and farmers often face the dilemma of information asymmetry [], resulting in low income. Digital literacy is an important form of human capital in the digital economy. Improving farmers’ digital literacy can enhance their endogenous development capabilities and, thus, increase their income level. Specifically, due to the lack of collateral and credit data and the high risk of agricultural production and operation, farmers often face strong financing constraints and high financing costs, and their production and operations are severely restricted. Farmers with greater digital financial literacy can use digital financial tools to overcome the limitations of physical outlets and the manual services of traditional financial institutions, obtain financial support at a lower cost, increase the purchase and investment of production materials such as agricultural machinery and equipment, improve agricultural production efficiency and output, and, thus, increase income. Moreover, digital agricultural production data can help farmers fully understand information such as market demand and agricultural product market prices to better formulate business strategies and increase agricultural product sales and income. Furthermore, farmers can broaden their income channels by receiving rural employment and digital financial education. For example, they can sell agricultural products through e-commerce platforms to achieve nonagricultural employment and increase income. Additionally, farmers with greater digital financial literacy can better identify financial risk, make reasonable financial decisions, and protect property security. Finally, farmers with greater digital financial literacy tend to be more willing to invest and are more inclined to contact and use digital financial tools, such as insurance and funds, to increase investment returns. Therefore, this paper proposes the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1:

Digital financial literacy effectively improves the income level of farmer families.

In rural areas, farmers have long formed social networks on the basis of kinship and geography. The solidification of social groups has blocked access to information, making it difficult for farmers to obtain resources and information across classes. Farmers with greater digital financial literacy can use digital technology and digital devices to integrate interpersonal trust relationships, break the confines of the social circle and social distance of the traditional acquaintance society, increase social interactions outside the circle, and expand social capital [,]. Social capital is a kind of social resource formed based on social networks, and the amount of an individual’s social capital is positively proportional to his or her social relationships []. First of all, social capital can help farmers obtain information about market prices and sales channels. Through social networks, farmers receive advice and information from other farmers or agricultural professionals, so as to better grasp market opportunities and improve the competitiveness of agricultural products, as well as to establish contacts with dealers, wholesalers, and retailers to seek more sales opportunities and obtain better sales prices, and ultimately increase incomes []. Second, social capital helps increase the level of trust between farmers, ease financing constraints, and increase the possibility of farmers obtaining private loans [], making it easier for farmers to obtain capital loans as well as agricultural insurance, so that farmers can improve the stability of their incomes in the face of natural disasters, market fluctuations, and other agricultural risks. Additionally, the accumulation of social capital can effectively obtain information outside the group, promote information sharing and resource allocation, supplement or replace productive assets, and increase labor productivity and income. Therefore, this paper proposes the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2:

Digital financial literacy improves farmers’ household income levels by enhancing farmers’ social capital.

In the digital age, important national strategies such as “Broadband China”, “Internet +”, and “Artificial Intelligence +” continue to advance, promoting the construction and improvement of urban and rural digital infrastructure, significantly increasing the development speed of digital finance, and expanding digital market channels for farmers to increase their income. However, due to China’s vast land area, digital inclusive finance is in the development stage, with uneven development among regions and significant disparities in the development levels of digital finance and financial markets. This situation limits the ability of rural households to enhance their digital financial literacy. From the perspective of different levels of economic development, rural areas in central and western China are generally characterized by a large gap in development effectiveness, urban–rural economic differentiation, lack of rural financial resources and other real problems, and the unbalanced development of digital financial inclusion is still due to the relatively fragile digital infrastructure of the country’s digital divide, the financial ecological imbalance, and the education divide, which is caused by the low level of rural education. The reason for the unbalanced development of digital inclusive finance is still due to the “digital divide” of the relatively fragile domestic digital infrastructure, the “ecological divide” of the unbalanced financial ecology, and the “educational divide” of the low level of rural education []. However, in areas with a higher level of inclusive financial development, more complete related infrastructure, and relatively high education levels, residents can more directly and conveniently use digital means to penetrate the financial market and access a higher level of financial knowledge, thus creating better opportunities and channels to increase family income. Therefore, this article proposes the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3:

Regional digital financial development plays a regulatory role in cultivating farmers’ digital financial literacy and improving farmers’ household income levels.

2.2. Research Design

2.2.1. Data Sources

Considering the significant changes in the income of the interviewed households due to the epidemic, as well as many uncontrollable factors during the epidemic, this paper selects research data from the 2019 China Household Finance Survey [] database, which is a nationwide sampling survey project conducted by the China Household Finance Survey and Research Center of Southwestern University of Finance and Economics. The project aims to collect relevant information on the microlevel of household finance and provide a description and detailed data on relevant issues for studying the impact of digital financial literacy on farmers’ income. The 2019 China Household Finance Survey sample covers 29 provinces (autonomous regions, municipalities), 343 districts and counties, and 1360 village (neighborhood) committees across the country. In the end, information on 34,643 households and 107,008 family members was collected. The data are representative of the entire country and all the provinces. The digital inclusive finance index comes from the “Peking University Digital Inclusive Finance Index (2019)”. The report data reflect the development level and regional balance of digital inclusive finance under China’s innovative digital finance trend.

This study’s sample is selected from rural household heads who completed the questionnaire survey. To avoid errors caused by outliers and missing values, the data of farmers with more missing information were eliminated. After data sorting, 8504 samples were finally obtained.

2.2.2. Model Setting

Benchmark Regression Model

The OLS model was used to explore the impact of digital financial literacy on farmers’ rural common prosperity. The benchmark regression model was constructed as follows:

where represents the natural logarithm of the total income of a farmer’s household in one year; represents the digital financial literacy score of the farmer’s household; represents control variables such as household head characteristics, family characteristics, and regional characteristics; is the intercept term; and are coefficients; and is a random disturbance term.

Mediation Effect Model

To test whether farmers’ social capital plays a mediating role in the impact of digital financial literacy on farmers’ household income, the hierarchical regression model of Wen Zhonglin [] was used to analyze the model via stepwise regression. Models (2–4) were used to explore the relationships between the core explanatory variables and the mediating variables. The specific model is as follows:

where is the mediating variable, which represents the social capital score of the farmer household; is the control variable; , , , and are the parameters to be estimated; and is the random disturbance term.

Moderating Effect Model

To determine whether the impact of farmers’ digital financial literacy on their household income is affected by their level of digital financial development in a province or region, the model was established according to (1) and moderating variables were added. To eliminate the possible heteroscedasticity effect of the interaction term and improve the goodness of fit, the following moderating effect model was constructed:

where represents the level of regional digital financial development, and represent centralized variables, and the meanings of the remaining variables are the same as those in Model (1).

3. Empirical Analysis

3.1. Variable Selection and Descriptive Statistics

3.1.1. Explained Variable

The dependent variable of this paper is the total income of the farmer’s household in one year (). To eliminate the impact of heteroscedasticity, the natural logarithm of total income is taken for empirical research.

3.1.2. Explanatory Variables

The independent variable of this paper is farmers’ digital financial literacy (). Using the measurement systems of Wang Wenzheng [] and Wu Zhiwei [], this paper divides digital financial literacy into three levels of progressive evaluation: financial knowledge, application of financial skills, and digital skills and use of digital financial products. The specific indicators and assignment methods are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Digital financial literacy indicator system and value assignment.

Measurements are made by the principal component factor analysis method proposed by Lyons et al. [] and by performing dimensionality reduction processing on the above multiple indicators to obtain digital financial literacy indicators. To ensure the accuracy and stability of the measurement and empirical results and to evaluate whether the filtered data are suitable for factor analysis and correlation analysis, a correlation test between the KMO test and Bartlett test was performed before factor analysis. The test results (Table 2) are shown. The p value significance of Bartlett’s sphere test is 0.000, and the KMO value is 0.720, which meets the test standards, indicating a strong correlation between various indicators, and it can be used for principal component analysis.

Table 2.

KMO and Bartlett’s correlation tests.

Following the research of Yin Zhichao [] and Zhu Tao [], this paper selects three principal component factors, whose cumulative contribution rate reaches 85.07%, indicating that the variables effectively cover most of the information. After the factors are rotated and the four principal component factors are obtained, it is necessary to calculate the common factor scores. This paper uses the proportion of the variance value provided by each principal component factor to the cumulative variance value as the weight and weights the three common factors. To facilitate the analysis in the following text, the original digital financial literacy scores are standardized; that is, they are processed into values between []. The conversion method is as follows, where represents the original digital financial literacy score of the household. and represent the maximum and minimum values of digital financial literacy, respectively.

By comparing the descriptive statistical analysis of the indicators for constructing the farmer sample (Table 3) with the entire sample, we can observe the difference between the national average of farmers’ financial knowledge in the sample and the national average of the survey.

Table 3.

Descriptive statistical analysis of digital financial literacy indicators.

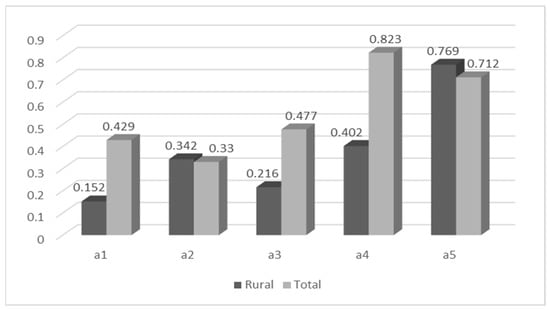

As shown in Table 2 and Figure 1, in terms of financial knowledge, the accuracy of rural residents’ calculations of interest rates and inflation is lower than the overall level, indicating that their financial knowledge reserves are relatively weak. Because some farmers are engaged in the primary industry, their overall understanding of risks and returns is relatively high. However, in general, the financial knowledge of urban and rural residents is generally not high.

Figure 1.

Descriptive statistical analysis of farmers’ and overall “financial knowledge level”.

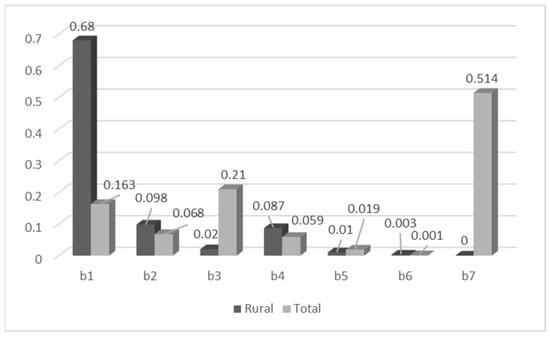

Figure 2 shows that rural residents’ financial skills are not as good as the general population’s. In terms of the proportion of people using online lending platforms (b7), the proportion of rural residents is 0, which is far lower than the general proportion of 0.514. Second, the proportion of rural residents and the general population using financial management products (b3) is 0.02 and 0.21, respectively, and the proportion of rural residents and the general population who hold stock accounts (b5) is 0.01 and 0.19, respectively. However, in terms of using mobile phones that can access the internet (b1), the proportion of rural residents reached 0.680, which is far greater than the general population proportion of 0.163. This may be the result of the government-led and multiparty promotion of the rural internet in recent years in view of the significant impact of the digital divide on the urban–rural dual structure. Additionally, the proportion of rural residents and the general population holding credit cards (b2) is 0.098 and 0.068, respectively; the proportion of rural residents and the general population that understands stocks, bonds, and funds (b4) is 0.087 and 0.059, respectively; and the proportion of rural residents and the general population holding funds (b6) is 0.003 and 0.001, respectively. Although urban and rural residents have basically met the conditions for digital infrastructure, there is still a large gap in the proportion of those who hold credit cards and use financial management products. In particular, there is still much room for improvement in rural residents’ willingness to use online lending platforms.

Figure 2.

Descriptive statistical analysis of the “financial skills application” of farmers and the whole population.

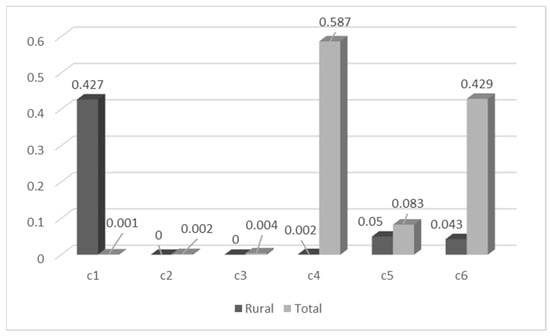

In terms of digital skills and the use of digital financial products, as shown in Figure 3, the proportion of rural residents is lower than that of the overall population. The proportion of rural residents and the general population using mobile payments (c1) is 0.427 and 0.001, respectively, which is higher for rural residents than for urban residents. This is closely related to the popularization of mobile internet and the continuous improvement of financial services in rural areas in recent years. The proportion of rural residents and the general population applying for bank loans (c2) through online banking and other APPs is 0 and 0.002, respectively; the proportion of rural residents and the general population obtaining education, medical, and vehicle loans through the internet (c3) is 0 and 0.004, respectively; the proportion of rural residents and the general population borrowing funds through online loan platforms (c4) is 0.002 and 0.587, respectively; the proportion of rural residents and the general population holding internet financial products (c5) is 0.05 and 0.083, respectively; and the proportion of rural residents and the general population obtaining income through internet financial products (c6) is 0.043 and 0.429, respectively. The proportion of those using mobile payments, applying for bank loans through online banking and other APPs, obtaining education, medical, and vehicle loans through the internet, and holding internet financial products is very low, especially for rural residents, who apply for bank loans through online banking and other APPs and obtain education, medical, and vehicle loans through the internet, all of which are 0. This may be due to the relatively weak economic conditions in rural areas, and borrowing from online lending platforms may increase their financial burden and interest rates, which they are unable to bear. Additionally, the relatively conservative social atmosphere and economic environment in rural areas make farmers unwilling to use the internet to trade with strangers.

Figure 3.

Descriptive statistical analysis of “digital skills and use of digital financial products” among farmers and the general population.

3.1.3. Mediating Variables

Social capital of farmer households (). As shown in Table 4, this paper measures the social capital of farmer households in four dimensions: farmer social networks, family relationships, personal reputation, and social norms. Twelve variables are selected, and the scores are constructed via the same method as the core explanatory variables.

Table 4.

Rural household social capital index system and value basis.

3.1.4. Moderating Variable

Regional financial development level (): this paper uses the 2019 Peking University Digital Inclusive Finance Index to measure the level of digital financial development in the province where the farmer household is located.

3.1.5. Control Variables

Variables reflecting the personal characteristics, family characteristics, and regional characteristics of the head of the farmer’s household were selected as control variables. The variables of the personal characteristics of the head of the farmer’s household included age (), gender (, male = 1), education level (, never attended school = 1; primary school = 2; junior high school = 3; high school = 4; technical secondary school = 5; college = 6; undergraduate = 7; master’s degree = 8; doctoral degree = 9), marital status ( married = 1), health status (, very good = 1; good = 2; average = 3; bad = 4; very bad = 5), working status (working, had a job last year = 1), and whether they work outside (, living or working outside for more than half a year = 1). The family characteristics included the number of houses owned (), family net assets (), agricultural assets (), land assets (), and family population size (). The regional characteristic variables included the region where the respondents are located (, east = 1, central = 2, west = 3, northeast = 4) and the city level where the respondents are located (, first-tier cities/new first-tier cities = 1, second-tier cities = 2, third-tier cities and below cities = 3). The descriptive statistics of all the variables are shown in Table 5 below.

Table 5.

Basic descriptive statistics of each variable.

3.2. Benchmark Regression

To perform a regression test on the benchmark model, this study gradually adds control variables for the personal characteristics of the household head, family characteristics, and regional characteristics of the interviewed household to the model. The regression results are shown in Columns (1)–(4) of Table 6. After the personal characteristics of the household head, family characteristics, and regional characteristics are gradually controlled, the regression coefficient of digital financial literacy on farmers’ income is significantly positive. After adding the control variables, the coefficient decreases significantly, indicating that controlling the variables is significantly effective. Preliminarily, H_1 verified that digital financial literacy has a significant positive effect on farmers’ income, indicating that farmers with higher digital financial literacy are better able to establish correct digital financial awareness and can effectively increase family income.

Table 6.

Benchmark regression results.

3.3. Robustness Test

Table 7 reports the results of the robustness check as follows:

Table 7.

Robustness test regression data results.

- The number of samples is reduced, and some samples are eliminated. Drawing on the practices of [], after excluding the household samples from first-tier and new first-tier cities, Column (1) shows that the regression coefficient of digital financial literacy is still significantly positive. This proves that the impact of digital financial literacy on rural household income does not change due to changes in the urban level, indicating that the results are robust.

- Smoothing extreme values. When digital financial literacy is improved by 1%, Column (2) shows that the regression coefficient is still significantly positive. In summary, the results of the previous benchmark regression analysis are robust.

4. Further Analysis

4.1. Endogeneity Test

Instrumental variable method: Taking into account the problems of omitted variables and reverse causality, we referred to existing research methods (Li Jingyuan, 2023 []) and selected the average digital financial literacy level (IV) of other households in the same region and the same city level as the tool. Variables were tested for endogeneity. The interviewed households had different digital financial infrastructures depending on the city levels in which they were located. The digital financial literacy of rural households at different city levels and age groups was not controlled by the interviewed households and is different from the digital financial literacy of the interviewed households. Literacy was not directly related. Table 8 reports the regression results of the instrumental variables. According to the results of the Cragg–Donald Wald F statistic and LM statistic, the selection of the instrumental variable passed the weak instrumental variable test and the nonidentifiable test, indicating that the selection of the instrumental variable was reasonable. After considering endogeneity issues, the regression coefficients of digital financial literacy on rural household income were all significant at the 1% level, further confirming that the cultivation of digital financial literacy provides the possibility of increasing rural household income, verifying again.

Table 8.

Endogeneity test regression results.

4.2. Mechanism Analysis

4.2.1. Mediating Effect

The previous theoretical analysis shows that farmers’ digital financial literacy can increase the income of rural households by increasing social capital. To further test whether farmers’ social capital plays an intermediary role in the impact of digital financial literacy on rural household consumption, this study establishes a model. We borrow Wen Zhonglin’s hierarchical regression model [] and use the stepwise regression method for analysis. The regression results are shown in Table 9. The results show that the coefficient of digital financial literacy is significant and has the same sign as expected, indicating that digital financial literacy can improve farmers’ income level by increasing their social capital.

Table 9.

Results of regression data for the mediation effect test.

Additionally, the Sobel test and bootstrap test results shown in Table 10 also reveal that social capital partially mediates the impact of digital financial literacy on farmers’ income.

Table 10.

Bootstrap test results.

In the social relationships between acquaintances in rural areas, where people look up but never look down, the habit of “talking about human feelings and relationships” is still important to the nature and action logic of Chinese acquaintance society and traditional rural society. Social networks have become a channel for obtaining important information in rural areas and are also the main method of interactive communication. To a large extent, the level of social capital determines the effective dissemination of information among rural residents and is effective at improving their own income status and achieving common prosperity. According to the stepwise regression results, the regression coefficient of the effect of digital financial literacy on social capital is positive and significant, indicating that improvements in digital financial literacy can significantly increase the social capital of rural residents. An improvement in social capital helps increase the income of rural households. Comprehensive theoretical analysis and empirical results show that digital financial literacy can promote rural household income by increasing the social capital of rural residents; thus, Hypothesis is confirmed.

4.2.2. Modulating Effect

To further examine the impact mechanism of digital financial literacy on China’s rural household income, this paper uses the digital financial inclusion index to measure the digital financial development level of the province in which rural households are located and adds adjustment variables and the relationships between adjustment variables and explanatory variables according to the baseline regression model’s interaction terms. The regression results are shown in Table 11. The results show that the coefficients of the regional financial development level and the interaction term between the regional financial development level and rural household digital financial literacy are significantly positive, indicating that the regional financial development level has significantly strengthened the impact of digital financial literacy in China. The improvement in rural household income indicates that the more developed digital inclusive finance in the area in which farmers are located, the higher the income of households with greater digital financial literacy. Thus, Hypothesis is verified.

Table 11.

Moderating effect regression data results.

The level of regional digital financial development plays an important regulatory role in improving farmers’ digital financial literacy, thereby increasing their family income level. First, the development of digital finance has improved the accessibility of financial services and the accessibility of financial market services, providing good knowledge acquisition conditions for improving farmers’ digital financial literacy and enabling them to more easily obtain diversified digital financial services. Second, improving information infrastructure helps farmers obtain key market information, and more complete financial infrastructure enhances the channels for farmer families to become wealthy, which is more conducive to increasing farmer family income. Additionally, digital finance reduces transaction costs, allowing farmers to conduct financial activities and market transactions more economically. Through these pathways, developing regional digital finance has effectively promoted the economic growth and income level of farmers.

4.3. Heterogeneity Analysis

- The impact of digital financial literacy on rural households at different income levels. The baseline regression results in Table 6 show that digital financial literacy significantly increases the income level of rural households. To explore the impact of digital financial literacy on families with different income levels in depth, this study defines samples with a family income above the median as high-income families and those with a family income below the median as low-income families. The Chow test results show that there are significant differences between groups, and the results for the low- and high-income samples are comparable. Columns (1) and (2) of Table 12 report the impact of digital financial literacy on families with different income levels. The results show that digital finance increases not only total household income but also the total income of low-income groups more than that of high-income groups. The income group results show that improving digital financial literacy is more necessary and urgent among low-income rural households and that digital financial literacy can narrow the income gap between rural households.

Table 12. Heterogeneity test regression data results.

Table 12. Heterogeneity test regression data results. - The impact of digital financial literacy on rural households in the east, middle, and west. Sample analysis by region: According to the approach of Huang Xianfeng [], since the eastern region takes the lead in achieving priority development, compared with the central and western regions, the eastern region’s financial market is more developed. Therefore, this study divides the sample into eastern, central, and western regions. The regression results are reported in Columns (3), (4), and (5) of Table 4 and Table 5, respectively. After the Chow test, the differences between the groups are significant. The sample results are comparable. The regression results indicate that, compared with those in the central region, the digital financial literacy of rural households in the eastern and western regions is greater in total household income. According to the Peking University Digital Financial Inclusion Index, in 2020, the digital financial inclusion index in the eastern region of China was 67.2, that in the central region was 54.6, and that in the western region was 49.8. The gap between the eastern and western regions reached 17.4 percentage points, and the gap between the central and western regions reached 4.8 percentage points. The eastern region is significantly greater than the central and western regions in terms of the breadth of digital financial coverage, the depth of digital financial use, and the digitalization of inclusive finance. The digital financial infrastructure is relatively complete, and farmers who improve their digital financial literacy can obtain more financial service help, increasing income; however, the income of farmers in the western region is relatively low. As digital financial inclusion increases in the western region, once farmers’ digital financial literacy improves, its marginal impact on income increases significantly.

According to the heterogeneity analysis part of this study, it can be seen that the improvement of digital financial literacy can help to reduce the income gap between regions and groups and promote the coordinated development of regions. By improving digital financial literacy, low-income farm households and farm households in less developed regions can better integrate into the digital economic system and share the dividends brought by digital finance, thus realizing the improvement of income level and the optimization of economic structure. The differences in the impact of digital financial literacy on the household income of farm households at different income levels and in different regions not only reflect the “enabling” effect of digital financial literacy but also reveal the important influence of regional financial development level, market opportunities, and policy environment on the mechanism of digital financial literacy. This heterogeneous phenomenon provides an important economic basis for the formulation of precise policies.

5. Conclusions and Policy Implications

By combining the domestic and foreign literature on the factors affecting farmers’ income and the definition and measurement of digital financial literacy, this paper selects questions from the CHFS questionnaire to construct a measure of digital financial literacy using the 2019 China Household Financial Survey (CHFS) data. The index system uses the factor analysis method to calculate farmers’ digital financial literacy scores. On this basis, the impact of digital financial literacy on farmers’ income and the intermediary effect of social capital through which digital financial literacy affects farmers’ income were empirically analyzed. Regional finance moderates the effect of development level, and finally, a heterogeneity test was conducted on the impact of digital financial literacy on farmers’ income. This research revealed that (1) digital financial literacy significantly increased the total income of farmers, with a unit impact of 65.77%. The results still hold true after robustness testing. (2) Mechanism analysis revealed that social capital plays a partial intermediary role in the impact of digital financial literacy on farmers’ income, with a unit utility value of 59.61%. The level of regional financial development plays a moderating role in the impact of digital financial literacy on farmers’ income, with a unit utility value of 42.64%. (3) The heterogeneity test revealed that digital financial literacy increased the income of low-income rural households to a greater extent, and digital financial literacy in the eastern and western regions increased the income of rural households more than in the central region. On this basis, this article has the following policy implications:

First, the government needs to increase financial investment and prioritize the promotion of rural digital infrastructure. In the process of building and improving rural digital hard and soft infrastructure, it should be ensured that villages are covered by the network and households are connected to the network. By relying on the village committee, professionals should be sent to each village regularly to carry out formal vocational training to improve farmers’ digital capabilities. Through inclusive finance or rural cooperative management and other learning methods, farmers are given certain financial practice opportunities, the process of participating in financial activities is simulated, and the entire process of financial activities is understood. Farmers should be encouraged to participate in small credit activities and investment activities and improve their awareness and financial skills through practice to accelerate popularizing finance and implementing financial knowledge. The pilot implementation of digital demonstration villages and financial demonstration villages should be accelerated, and points should be used to form lines to form surfaces to comprehensively improve farmers’ digital literacy and financial literacy. Although infrastructure construction requires a large initial investment, in the long run, it can significantly reduce the transaction costs of financial services, enhance the availability of financial services, and have a long-term positive effect on the enhancement of the income of rural households. In addition, the improvement of infrastructure not only enhances the digital financial literacy of current farmers but also lays the foundation for the digital transformation of the rural economy in the future, which has significant sustainability.

Second, the market needs to improve the supply of digital products and services. Financial institutions should combine farmers’ financial needs and actual production and operation activities, actively innovate financial products and services, and provide targeted financial products and services. Financial institutions should strengthen the quality of financial services; deepen various types of financial services, such as farmer withdrawals, remittances, transfer services, and mobile payments; and provide farmers with convenient and simple financial products and services. Financial institutions can combine financial products with farmers’ practical activities so that farmers can use their financial knowledge and skills in actual applications, and continuously improve their financial literacy and farmers’ personal financial well-being. Financial institutions need certain R&D costs for product innovation and service optimisation, but from the perspective of market competition, they are able to increase their share of the rural market and customer satisfaction. Through the supply of accurate financial products, the financial participation and income level of rural households can be effectively enhanced, while also contributing to the sustainable development of financial institutions. In addition, improving digital financial literacy not only improves current income levels, but also enhances the ability of farm households to cope with future economic changes and contributes to the sustainable development of the rural economy.

Third, farmers should take the initiative to learn new digital skills. Farmers should establish a correct view of financial investment and be able to carry out correct investment and financial management activities to enhance their awareness of financial risk prevention. Family members should also actively participate in family financial investment decisions, adapt to the wave of digital villages, continuously improve digital capabilities and financial literacy, and accumulate digital human capital to broaden income channels and achieve stable growth in farmers’ income. In addition, improving digital financial literacy not only improves current income levels, but also enhances the ability of farm households to cope with future economic changes and contributes to the sustainable development of the rural economy.

Fourth, the two-way flow of urban and rural resources needs to be promoted and the vitality of rural areas stimulated. Special incentive measures can be taken to encourage returnees to start businesses, such as setting up special funds, issuing start-up subsidies, and providing transportation support. The focus should be placed on returnees with digital financial literacy, and encouraging them to drive local employment through innovative models such as live e-commerce and the digital transformation of rural tourism. By accelerating the digital transformation of agriculture, we can support the connection between agricultural cooperatives and digital platforms, using blockchain technology to achieve full traceability in production and sales, improve the value preservation rate of agricultural supply chains, promote the connection between the increase in incomes of left-behind farmers and industrial upgrading, and alleviate the pressure of labor outflow. A comprehensive database of “digital financial literacy-income flow-industrial transformation” should be established to evaluate the effects of relevant policies in real time. The digital agriculture compensation mechanism in areas with net labor outflow should be strengthened, and cultivating emerging digital industries in areas with population inflow should be prioritized. This strategy helps prevent structural imbalances caused by policy homogeneity.

However, there are some limitations to this study. First, due to the timeliness of the data, the findings of this paper may not fully reflect the current situation, and the impact of digital financial literacy may change with the passage of time and the development of digital finance. Second, this study is mainly based on data from China, which may have geographical limitations, and the applicability of its conclusions in other countries and regions may require further verification. In addition, this paper mainly focuses on the direct impact of digital financial literacy on income, and there is insufficient exploration of the indirect impact and long-term effects.

Future research can expand in the following aspects: first, updating the data to verify the timeliness and dynamic changes of the impact of digital financial literacy; second, expanding the scope of the study to explore the impact of digital financial literacy on farm household income in different countries and regions; and third, analyzing in-depth the paths and mechanisms of the indirect impact of digital financial literacy on the income of farm households, as well as its long-term effects on the welfare of farm households. In addition, future research could focus on the interaction of digital financial literacy with other financial literacy (e.g., traditional financial literacy) and on how policy interventions can improve the digital financial literacy of farm households, thereby contributing to the growth of farm household incomes and narrowing the urban–rural income gap.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.Y. and W.L.; methodology, Y.Y.; software, W.L.; validation, Y.Y.; formal analysis, H.L.; investigation, S.L.; resources, S.L.; data curation, W.L.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.Y., W.L. and H.L.; writing—review and editing, Y.Y.; visualization, W.L.; supervision, Y.L.; project administration, Y.L.; funding acquisition, Y.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work has been financially supported by the Major Program of the National Social Science Foundation of China (No. 18BMZ126).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data can be obtained from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- OECD Regions and Cities at a Glance 2022 (Summary in Hebrew). 2022. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/oecd-regions-and-cities-at-a-glance-2022_14108660-en.html (accessed on 23 March 2025).

- Yin, X.; Wang, Q. The study on financial development, urbanization and urban & rural residents’ income gap in China. Econ. Geogr. 2020, 40, 84–91. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, C.; Li, S.; Yue, X. An analysis of changes in the extent of income disparity in China (2013–2018). Soc. Sci. China 2021, 1, 33–54. [Google Scholar]

- Kastrop, C.; Ponattu, D.; Schmidt, J.; Schmidt, S. The Urban-Rural Divide and Regionally Inclusive Growth in the Digital Age. G20 Insights. Policy Area. Inequality, Human Capital and Well-Being 2019. Available online: https://t20japan.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/t20-japan-tf6-8-urban-rural-divide-regionally-growth-digital-age.pdf (accessed on 23 March 2025).

- Yuan, Y.; Wang, M.; Zhu, Y.; Huang, X.; Xiong, X. Urbanization’s effects on the urban-rural income gap in China: A meta-regression analysis. Land Use Policy 2020, 99, 104995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, F.; Xiao, D.; Chang, M.-S. The impact of carbon emission trading schemes on urban-rural income inequality in China: A multi-period difference-in-differences method. Energy Policy 2021, 159, 112652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, W.; Zhang, J. Income Level, Income Gap and Independent Innovation: The Formation and Escaping of the Middle-income Trap. Econ. Res. J. 2018, 53, 47–62. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Liu, J.; Huo, X. Impacts of tenure security and market-oriented allocation of farmland on agricultural productivity: Evidence from China’s apple growers. Land Use Policy 2021, 102, 105233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakano, Y.; Magezi, E.F. The impact of microcredit on agricultural technology adoption and productivity: Evidence from randomized control trial in Tanzania. World Dev. 2020, 133, 104997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giné, X. Access to capital in rural Thailand: An estimated model of formal vs. informal credit. J. Dev. Econ. 2011, 96, 16–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liping, C. Research on Regional Differences in the Impact of Rural Financial Exclusion on Urban-Rural Income Gap. Master’s Thesis, Nanjing Forestry University, Nanjing, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Diniz, E.; Birochi, R.; Pozzebon, M. Triggers and barriers to financial inclusion: The use of ICT-based branchless banking in an Amazon county. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2012, 11, 484–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, M.; Liao, G.; Wang, J. Spatial spillover effect and threshold effect of digital financial inclusion on farmers’ income growth—Based on provincial data of China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aisaiti, G.; Liu, L.; Xie, J.; Yang, J. An empirical analysis of rural farmers’ financing intention of inclusive finance in China: The moderating role of digital finance and social enterprise embeddedness. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2019, 119, 1535–1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Hui, L. Digital financial inclusion, new urbanisation and the urban-rural income gap. Stat. Decis. 2021, 37, 157–161. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, S.; Zhang, R.; Di, D.; Li, G. Does digital transformation promote global value chain upgrading? Evidence from Chinese manufacturing firms. Econ. Model. 2024, 139, 106810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W. Research on the Impact of Digital Financial Literacy on Household Income Gap. Master’s Thesis, Shandong University of Finance and Economics, Jinan, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Lian, H.; Shaoqun, Y.; Chengyu, Y.; Luhan, J. Does digital inclusive finance help alleviate relative poverty? Financ. Res. 2021, 47, 93–107. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, P.J.; Huang, B.; Trinh, L.Q. The Need to Promote Digital Financial Literacy for the Digital Age. IN THE DIGITAL AGE. 2019. Available online: https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/503706/adbi-realizing-education-all-digital-age.pdf#page=56 (accessed on 23 March 2025).

- Ping, C.; Shuhua, W. Digital financial inclusion, digital divide and multidimensional relative poverty: From the perspective of aging. Econ. Res. 2022, 10, 173–190. [Google Scholar]

- Lyons, A.C.; Kass-Hanna, J. A methodological overview to defining and measuring “digital” financial literacy. Financ. Plan. Rev. 2021, 4, e1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephen, G. Digital financial literacy skills among library and information science professionals in northeast India. A study. Libr. Philos. Pract. 2022, 6709, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Ravikumar, T.; Suresha, B.; Prakash, N.; Vazirani, K.; Krishna, T. Digital financial literacy among adults in India: Measurement and validation. Cogent Econ. Financ. 2022, 10, 2132631. [Google Scholar]

- Saini, S. Digital financial literacy: Awareness and access. Int. J. Manag. IT Eng. 2019, 9, 201–207. [Google Scholar]

- Azeez, N.A.; Akhtar, S.J. Digital financial literacy and its determinants: An empirical evidences from rural India. South Asian J. Soc. Stud. Econ. 2021, 11, 8–22. [Google Scholar]

- Kamble, P.A.; Mehta, A.; Rani, N. Financial inclusion and digital financial literacy: Do they matter for financial well-being? Soc. Indic. Res. 2024, 171, 777–807. [Google Scholar]

- Prasad, H.; Meghwal, D.; Dayama, V. Digital financial literacy: A study of households of Udaipur. J. Bus. Manag. 2018, 5, 23–32. [Google Scholar]

- Briggeman, B.C.; Gray, A.W.; Morehart, M.J.; Baker, T.G.; Wilson, C.A. A new US farm household typology: Implications for agricultural policy. Appl. Econ. Perspect. Policy 2007, 29, 765–782. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Giles, J.; Rozelle, S. Does it pay to be a cadre? Estimating the returns to being a local official in rural China. J. Comp. Econ. 2012, 40, 337–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathijs, E.; Noev, N. Subsistence farming in central and eastern Europe: Empirical evidence from Albania, Bulgaria, Hungary, and Romania. East. Eur. Econ. 2004, 42, 72–89. [Google Scholar]

- Kung, J.K.-S. Off-farm labor markets and the emergence of land rental markets in rural China. J. Comp. Econ. 2002, 30, 395–414. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, W.; Li, M.; Li, J. Digital Rural Empowerment and Farmers‘ Income Growth: Role Mechanisms and Empirical Tests—A Study on the Moderating Effect Based on Farmers’ Entrepreneurial Activity. J. Southeast Univ. (Philos. Soc. Sci.) 2021, 23, 116–125+148. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, C. A Study of the Impact of Internet Use on Farmers’ Incomes. Master’s Thesis, Chongqing Technology and Business University, Chongqing, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C.; Jiang, W. A study on the impact path of rural human capital on farmers’ income growth under the rural revitalisation strategy. Xinjiang Farm Res. Sci. Technol. 2020, 11, 12–21. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, X.; Luo, G.; Huang, Y. Research on the revenue effect of financial support to agriculture based on the threshold model. Inq. Into Econ. Issues 2015, 6, 10–17. [Google Scholar]

- Zang, D.; Li, F.; Jiang, Y. Digital Capability and Farmers’ Income—Based on Survey Data on Livelihood Development in Tibet, China. J. Tibet. Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2022, 37, 187–197+205. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, L.; Lianyun, Z. Digital financial capabilities and relative poverty. Econ. Theory Econ. Manag. 2021, 41, 11. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, D. Empirical study on the impact of digital financial capabilities on household consumption upgrade. Stat. Decis. 2022, 38, 147–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuanning, S.; Yahong, L.; Le, S. Digital financial capabilities, income diversification and household consumption upgrade. Consum. Econ. 2022, 38, 70–80. [Google Scholar]

- Choung, Y.; Chatterjee, S.; Pak, T.-Y. Digital financial literacy and financial well-being. Financ. Res. Lett. 2023, 58, 104438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xinyan, S. The impact of digital financial literacy on farmers’ credit constraints: An analysis of the mediating effect based on risk attitude. Today’s Fortune 2024, 6, 98–100. [Google Scholar]

- Mingjie, C. Research on the Impact of Digital Financial Literacy on Household Financial Asset Allocation. Master’s Thesis, Guizhou University, Guiyang, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Yu, W. Can digital financial literacy promote common prosperity of families?—A study based on the Chinese Household Finance Survey. Financ. Dev. Res. 2023, 6, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Z.; Wu, Y.; Gan, L. Financial accessibility, financial market participation and household asset choices. Econ. Res. J. 2015, 50, 87–99. [Google Scholar]

- Lei, S. Study on the Impact of Mobile Internet on the Income Level of Low-Income Households. Master’s Thesis, Central South University, Changsha, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, X. Digital Finance, Household Heterogeneous Decision Making and Common Wealth—Empirical Evidence Based on Chinese Household Finance Survey Data. Stat. Decis. 2024, 40, 75–80. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, G.; Jiajia, L.; Zhixiong, D. Evolution trend of urban-rural income gap: International experience and its implications for China. World Agric. 2022, 6, 5–17. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, Q.; Wen, H.; Lee, C.-C. How does economic growth target affect corporate environmental investment? Evidence from heavy-polluting industries in China. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2022, 95, 106799. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y.; Huang, Z. The development of digital finance in China: Present and future. China Econ. Q. 2018, 17, 205–218. [Google Scholar]

- Binhui, W.; Mingzhong, L. The impact of digital economy on agricultural productive services: From the perspective of non-agricultural employment and factor supply. J. Nanjing Agric. Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2024, 24, 154–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jianjun, L.; Xun, H. Inclusive finance, income distribution and poverty alleviation: Policy framework selection to promote efficiency and fairness. Financ. Res. 2019, 465, 129–148. [Google Scholar]

- Jinjie, W.; Shaohong, M.; Yuxue, S. Is e-commerce beneficial to rural residents’ entrepreneurship?—Based on the perspective of social capital. Econ. Manag. Res. 2019, 40, 95–110. [Google Scholar]

- Aiyun, N.; Ying, G. Internet use and residents’ social capital: A study based on the China Household Panel Studies. Macroecon. Res. 2021, 9, 133–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yudong, Q.; Xi, C. Employment effects of digital life: Internal mechanisms and micro-evidence. Financ. Trade Econ. 2021, 42, 98–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weicong, W.; Xindong, Z. Does Social Capital Increase Farm Household Income Mobility?—Empirical Evidence from Three Periods of Chinese Household Tracking Survey Data. Shanghai Financ. 2024, 4, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sha, L. Research on the impact of social capital on rural private lending: A test of the mediating effect based on interpersonal trust. Wuhan Financ. 2019, 2, 70–75. [Google Scholar]

- Zhihong, S.; Yaping, H.; Hongfei, H. A study on the impact of digital inclusive financial development on rural residents’ income from a regional perspective. Financ. Dev. Rev. 2023, 4, 48–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, L.; Yin, Z.; Tan, J. Report on the Development of Household Finance in Rural China (2014); Springer: Singapore, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Zhonglin, W.; Baojuan, Y. Mediation effect analysis: Method and model development. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2014, 22, 731–745. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Z.; Yin, M.; Wu, Y. Research on the Measurement of Residents‘ Digital Financial Literacy and Its Influencing Factors—An Empirical Test Based on the Data from the Questionnaire Survey on Chinese Residents’ Digital Financial Literacy in 2022. J. Cent. Univ. Financ. Econ. 2023, 8, 103–115. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, Z.; Song, Q.; Wu, Y. Financial literacy, investment experience and household asset selection. Econ. Res. J. 2014, 49, 62–75. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, T.; Qian, R.; Li, S. An empirical study of the impact of financial literacy and education level on household financial behaviour. Financ. Perspect. J. 2015, 5, 85–93. [Google Scholar]

- Jiguo, S.; Wei, C. Digital inclusive finance and common prosperity of farmers and rural areas: An analysis based on the perspective of income gap. Rural. Financ. Res. 2023, 4, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).