1. Introduction

In recent years, ethnic minority tourism has emerged as a significant area of study within global tourism research. Tourist destinations in ethnic minority regions hold significant academic value in studying tourist preferences and revisit intentions due to their unique cultural and social contexts. With the continuous growth in the demand for high-quality development in cultural tourism and the intensifying competition among similar tourist destinations, cultural tourism destinations are facing a series of complex challenges, particularly in terms of how to effectively maintain visitor numbers and enhance competitiveness [

1]. Revisit intention (RI) is defined as the behavioral intention of tourists to visit a destination again in the future. It serves as a key measure of tourist loyalty and destination attractiveness and has a profound impact on the sustainable development of tourism brands. Tourism development in ethnic minority regions attracts investment, creates jobs, and boosts economic growth. Repeat visitors are more cost-effective than new customers, generating profits approximately five times higher [

2], thus offering greater economic benefits to tourism operators. High repeat visitation rates enhance economic gains, particularly vital for low-income countries and disadvantaged groups, including ethnic minorities, while also amplifying tourism’s broader economic multiplier effect, benefiting sectors beyond direct employment and business opportunities [

3]. Additionally, tourism helps ethnic minority communities preserve their cultural traits and uniqueness, fostering confidence and determination to protect their heritage [

4]. In addition, sustained tourism flows stabilize visitor numbers and contribute to the sustainable development of the destination [

5,

6].

Ethnic minority regions boast rich cultural assets, such as traditional festivals, handicrafts, and architecture, which could form the core competitive advantages of their tourism brands. However, insufficient systematic brand development has resulted in low market recognition and difficulty in attracting tourists. Research shows that clear brand positioning and image can significantly enhance tourists’ perceived value and behavioral intentions [

7]. For example, in the process of tourism brand development, a positive destination image can promote tourists’ sustainable behavioral intentions [

8]. Although ethnic minority regions provide unique cultural experiences, visitors often lack lasting memories after their initial visit, leading to low revisit intentions. Research indicates that ethnic characteristics, spatial concentration, and policymaking are key drivers of these destinations’ brand attractiveness [

9]. Enhancing the diversity and cultural depth of visitor experiences is key to addressing low revisit intentions. Ethnic minority regions face brand-building challenges, such as limited promotion and insufficient focus on core values, hindering market competitiveness and long-term growth. Research highlights that successful brand building for repeat visits requires a comprehensive approach that incorporates destination safety, quality, image, and visitor satisfaction [

10]. By formulating a long-term brand development plan and aligning it with market demand while optimizing brand communication, the brand’s visibility and reputation can be enhanced, thereby driving the development of ethnic brands into a positive cycle. Additionally, through public facilities, distinctive landscapes, and cultural connotations, emotional attachment to the brand among tourists can be strengthened, which in turn enhances satisfaction and a sense of identity [

11]. Furthermore, repeat visitation behavior in cultural tourism is driven by tourists’ psychological needs, such as emotional fulfillment, information dissemination, and interactive experiences. Among these, specific experiences can enrich tourists’ loyalty intentions, promote revisit intentions, and contribute to the sustainability of tourism destinations [

12]. Studying factors influencing repeat visitation is crucial for the sustainable development of ethnic minority tourism brands. Insufficient brand impact not only limits tourism consumption but also disrupts the balance between cultural dissemination and resource preservation. Sustainable tourism branding requires harmonizing cultural protection, ecological sustainability, and economic growth, thus promoting synergy between heritage preservation and development. Ethnic minority villages, which are key tourism destinations, attract visitors seeking unique cultural experiences. Yet, many studies overlook tourists’ motivations, perceptions, and attitudes toward these villages [

13]. Therefore, it is essential to study how to enhance the motivations and attitudes of visitors to ethnic minority tourism destinations. This research aims to fill this gap by systematically analyzing the key factors in the sustainable design and development of ethnic minority tourism brands, particularly the influence of cultural representation (CR), emotional resonance (ER), spatial attributes (SAs), information dissemination (ID), and policy support (PS) on tourists’ revisit intentions.

In practical terms, the findings of this study offer valuable insights for tourism managers to develop more targeted frameworks for brand development, marketing strategies, and policy support. Understanding the factors that influence revisit intention, such as destination image, perceived value, and attachment, can help destination management organizations (DMOs) tailor their products to meet visitors’ expectations and encourage them to return [

14,

15,

16]. Furthermore, the study of revisit intention also contributes to building customer loyalty and generating positive word-of-mouth, thereby enhancing the destination’s reputation and attracting more visitors [

16,

17,

18]. Such strategies can strengthen the cultural heritage and economic resilience of local communities, thereby supporting the long-term prosperity and sustainability of tourism destinations.

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Theory of Planned Behavior

This study is based on the TPB, proposed by Ajzen, which is a widely used framework for explaining and predicting individual behavioral intentions [

19]. The core of the TPB lies in three key drivers: personal attitude (PA), subjective norm (SN), and perceived behavioral control (PBC), which collectively influence an individual’s behavioral intention (BI). The TPB model proposed by Ajzen has since been extensively studied.

This theory demonstrates strong explanatory power in assessing the decision-making processes of complex behaviors (such as tourism, green consumption, and environmental protection behaviors), especially under the influence of multiple interacting factors [

20,

21]. Compared to other behavioral theories, such as Stern’s Value-Belief-Norm Theory [

22], the Stimulus-Organism-Response theory [

23], and the Innovation Diffusion Theory [

24], the TPB offers greater flexibility and applicability in capturing the dynamic relationships of complex behaviors [

25]. The VBN theory emphasizes the importance of individual values and norms, making it suitable for exploring the ethical aspects of environmental behavior. However, it fails to fully capture the dynamic interactions between multiple indicators [

22]. The SOR theory is widely used to explain individual behavioral responses to different stimuli, but it relies entirely on linear causal paths and neglects the dynamic interactions in complex decision-making processes [

25]. Innovation Diffusion Theory focuses more on the promotion of technology adoption behaviors, but its explanations are similar when applied to cultural and emotional factors [

24].Through emotional and cognitive evaluations, the TPB framework connects external factors (such as CR, PS, and ID) with BI, thereby providing a more comprehensive analytical tool for studying complex behaviors [

26,

27]. However, the traditional TPB model has limitations in its explanatory power when studying behavioral decision-making in specific contexts, such as generational differences, cultural backgrounds, or emotional resonance [

28]. To address these limitations, this study expands upon the (TPB) framework by focusing on the sustainable design of tourism brands in ethnic minority regions, thereby offering a new theoretical perspective.

As the TPB model has been increasingly applied to the general tourism industry, a growing number of researchers have utilized this model to investigate sustainable tourism. For instance, Kuo and Dai applied the TPB framework to study low-carbon tourism behaviors, where behavioral intention refers to the intention to visit low-carbon tourist destinations in the future [

29]. Similarly, in the present study, behavioral intention refers to the intention of tourists to revisit a destination. In ethnic tourism research, scholars often focus on tourists’ behavioral intentions and explore the factors influencing them (for instance, how attitude and intention significantly affect tourism behavior in the context of sustainable tourism) [

30]. While the TPB provides a well-established framework for understanding behavioral intentions, the existing research has given relatively less attention to the indirect influences of CR, ER, SAs, ID, and PS on PA, SNs, and PBC—all of which play critical roles in shaping tourists’ revisit intentions. To address this gap, this study applies the TPB as the foundational theoretical model while integrating these five factors to further examine their effects on tourist decision-making processes in ethnic tourism destinations.

In the SEM framework, we establish PA, SNs, and PBC as direct determinants of BI, while CR, ER, SAs, ID, and PS serve as indirect influencers that shape these determinants. Specifically, CR and ER influence PA, reflecting how cultural engagement and emotional connection with the destination shape tourists’ attitudes. Meanwhile, SAs, ID, and PS impact PBC, emphasizing how accessibility, information availability, and supportive policies enhance tourists’ confidence in their ability to make travel decisions. Additionally, SNs are influenced by external social and informational factors, aligning with previous studies that highlight the role of societal influence in shaping behavioral intentions.

By embedding these constructs within the TPB, this study extends the theoretical model to better capture the decision-making mechanisms of tourists in ethnic tourism destinations. This integrated approach strengthens the theoretical foundation of the research while providing a more nuanced explanation of how indirect and direct factors collectively shape revisit intentions. This theoretical extension not only enhances the applicability of the TPB in tourism behavior studies but also contributes to destination branding and sustainable tourism management by offering practical insights into how cultural and structural factors influence traveler behavior.

2.2. Ethnic Tourism

Related research suggests that ethnic tourism is a distinctive type of tourism characterized by the unique environments and customs of specific communities, which are often considered sacred, such as traditional dances, rituals, and ceremonies. With the growing demand for ethnic tourism, particularly organized forms of tourism, one effective approach to developing ethnic tourism is by focusing on and catering to the interests and needs of tourists [

31,

32].

Research on ethnic tourism often emphasizes its effects on indigenous ethnic communities, exploring both beneficial and detrimental outcomes [

33]. On the beneficial side, it offers local ethnic groups a platform to display their cultural heritage, fostering the revival of traditional practices, reinforcing cultural identity, and encouraging greater appreciation and respect for ethnic traditions [

34]. Conversely, ethnic tourism can also lead to adverse socio-cultural consequences, such as the commodification of culture, erosion of cultural authenticity, and the decline of traditional customs [

35]. These negative effects can be alleviated or reduced through strategic planning and the active participation of all stakeholders, particularly local ethnic communities. Studies on ethnic tourism have been carried out in various Chinese provinces, such as Hunan, Guangxi, Inner Mongolia, Yunnan, Hainan, Guizhou, Xinjiang, and Guangdong. These investigations primarily examine the social and cultural implications of ethnic tourism on local minority groups as well as the associated policy frameworks [

13]. The findings highlight the challenges of reconciling the preservation of ethnic cultures with economic growth, meeting the aspirations of ethnic minority residents for enhanced quality of life, and addressing their limited influence over the development of the tourism sector.

2.3. Research Model and Hypothesis Formulation

2.3.1. Cultural Representation

In their study on emotion-based souvenir design, Zhu et al. found that destination-related cultural factors, such as tourism souvenirs, can evoke positive emotional experiences among tourists [

33]. Both natural and cultural environmental factors have the potential to stimulate positive emotions in tourists [

33]. However, heritage revitalization experiences enriched with traditional folklore, music, dance, and other cultural elements, as well as other dynamic interactive experiences, have a more significant stimulating effect than natural environments [

34]. Chen’s study on ecotourism in ethnic minority regions highlights the significant impact of local culture on the sustainable development of ecotourism [

35]. The cultural elements of ethnic minorities form the core appeal and uniqueness of ethnic tourism destinations, serving as a key component in the tourism environment, the commercialization of culture, and the development of the green economy. These CRs reflect the rich local heritage, creating a distinct attraction that differentiates these destinations from others.

CR, as the cornerstone of a tourism destination’s attractiveness, encompasses not only tangible cultural elements, such as architecture, traditional attire, and landmarks, but also intangible cultural heritage, including festivals and local customs. The integration of these cultural elements significantly enhances the uniqueness and appeal of a destination while enriching visitors’ experiences and increasing their satisfaction. Research has indicated that the combination of tangible cultural aspects, such as buildings and landmarks, with intangible cultural practices, such as traditional arts and festivals, can shape the cultural identity of the destination, providing visitors with a profound cultural experience [

36,

37,

38]. Furthermore, traditional attire and local cultural activities not only contribute to conveying the historical and ethnic characteristics of the destination but also create a unique tourist appeal on both visual and emotional levels [

39,

40]. In terms of intangible aspects, cultural festivals, traditional music, local cuisine, dance performances, and rituals offer dynamic and immersive experiences, fostering emotional connections between tourists and local communities. These activities often emphasize the richness, uniqueness, and interactivity of the culture. Many tourists choose to visit ethnic minority regions precisely due to their interest in ethnic cultures and their attention to intangible cultural heritage and traditional crafts [

41,

42,

43]. At the same time, festivals and cultural performances not only serve as a means of showcasing the ethnic minority regions but also play an active role in the preservation and dissemination of cultural traditions [

44]. Meanwhile, the values or societal expectations conveyed through CR (e.g., participating in ethnic festivals as a manifestation of respect for culture) can create a sense of social obligation for individuals, thereby shaping their subjective norms [

45]. These interactions collectively underpin the formation of behavioral intentions and decision-making within the tourism environment. At the same time, the cultural adaptation theory states that when tourists encounter different cultures, they go through an adaptation process to adjust their attitudes and behaviors, allowing them to better integrate into the destination’s culture.

Furthermore, cultural representations promote cultural appreciation and preservation while simultaneously supporting local economic development, thereby fostering sustainable tourism practices. Destinations that emphasize cultural diversity and authenticity attract culturally conscious tourists, enhancing the destination’s appeal and generating sustainable economic benefits. Therefore, the following hypothesis can be proposed:

H1. Cultural representation significantly influences tourists’ personal attitudes.

H2. Cultural representation significantly influences tourists’ subjective norms.

2.3.2. Emotional Resonance

The relevant studies indicate that ER is a significant factor influencing tourists’ attitudes and behavioral tendencies [

46]. Destination brands enhance tourists’ sense of participation in cultural activities and convey unforgettable travel experiences, which helps to strengthen the emotional connection between tourists and the destination [

47,

48]. As active participants in the experience, tourists’ emotions are heightened during and after the experience. Specifically, ER not only helps tourists form a positive perception of the local culture but also significantly enhances their emotional connection to the destination, thereby promoting the formation of their revisit intention.

In ethnic minority regions, tourists’ emotional resonance is often profoundly influenced by multi-sensory stimuli and personalized participation. Ethnic traditional festival tourism helps build a sense of community among ethnic groups, fostering social connections and emotional exchanges while providing tourists with a space for festive experiences [

49]. In such an atmosphere, tourists can both celebrate a glorious past and fulfill a sense of contemporary belonging, further enhancing their travel experience [

50,

51]. Meanwhile, environmental stimuli in ethnic minority regions, such as specific ritual activities, can evoke tourists’ intrinsic emotions, and through motivations such as cultural exploration and social interaction, influence their overall evaluation and attitude toward the destination.

ER, particularly those activities that evoke ER, can deepen tourists’ emotional attachment to the destination, thereby influencing their revisit intention. This process not only strengthens tourists’ sense of identity with the destination but may also encourage them to choose to revisit these places in the future. Specifically, some studies suggest that tourists’ ER during cultural activities is influenced not only by the activities themselves but also by factors such as their gender, cultural background, and personality traits. These factors interact to determine tourists’ ER during cultural events, thereby further influencing their behavioral intentions and emotional connection to the destination [

52]. In ethnic minority tourism destinations, tourists of different genders may exhibit varying ER to cultural activities, which in turn can influence their willingness to participate and their positive attitudes toward the destination.

Based on the above perspectives, the following hypothesis can be proposed:

H3. Emotional resonance significantly influences tourists’ personal attitudes.

2.3.3. Spatial Attributes

SAs are one of the key factors influencing tourists’ personal attitudes and perceived behavioral control. The quality of tourism infrastructure and public services directly affects tourists’ travel decisions and the overall quality of their tourism experience [

53,

54,

55]. It encompasses aspects such as the infrastructure of tourism destinations, transportation accessibility, and spatial agglomeration effects [

44]. Transportation is a crucial component of the tourism system, and the mobility of tourists has been enhanced with the development of transportation infrastructure, including roads, railways, and waterways [

56,

57]. Furthermore, the establishment of infrastructure such as accommodation and tourism information services not only enhances the accessibility of tourism destinations but also improves the quality of the tourists’ experience, thereby attracting more tourism consumption. In addition, according to Porter’s cluster theory, well-developed infrastructure is a key factor in the development of tourism industry clusters [

58]. Tourism industry clusters significantly enhance the competitiveness of the tourism sector and promote spatial agglomeration effects [

59]. At the same time, they stimulate the development of the tourism economy, thereby further advancing the sustainable development of tourism regions.

In addition, the attractiveness of SAs is often reinforced through visual communication, enhancing tourists’ perceptions and further influencing their experience quality at the destination. The combination of local cultural representations and spatial features, particularly in ethnically distinct regions with strong cultural symbols, can strengthen tourists’ emotional identification and cultural engagement, thereby enhancing their positive attitudes and behavioral intentions toward the destination. For example, the integration of unique geographical locations, historical landmarks, ethnic cultural symbols, and landscape elements not only captures tourists’ attention but also deepens their emotional resonance, leading to a more profound tourism experience and increasing the competitiveness of the destination [

60].

Therefore, SAs are not only an essential element in the development of tourism destinations but also a key factor influencing tourist behavior. As relevant studies have indicated, the SAs of rural tourism destinations directly affect tourists’ emotional identification and behavioral responses toward the destination. In particular, in the context of improved SAs, tourists’ satisfaction with the destination and their perceived behavioral control significantly increase [

44]. Therefore, the following hypotheses can be proposed:

H4. Spatial attributes significantly influence tourists’ personal attitudes.

H5. Spatial attributes significantly influence tourists’ perceived behavioral control.

2.3.4. Information Dissemination

Despite ongoing efforts to study the development of tourism and tourist behavior, research on the impact of social media on tourism remains limited [

61]. However, in the context of the proliferation and development of online information sources, the importance of social media continues to grow daily [

62]. In addition to providing consumers with channels for booking and purchasing various travel products and services, online information sources have also greatly transformed the way consumers gather information, make decisions, and share purchase opinions [

63,

64].

First, ID significantly influences subjective norms (SNs). Tourists are more likely to share and promote destinations they identify with to others [

65]. Therefore, information sharing through forms such as electronic word-of-mouth and travel reviews can shape tourists’ social expectations, thereby influencing their behavioral choices. Research indicates that the enthusiasm of potential tourists is often inspired by the travel experiences of others and may translate into their own visitation behavior [

66]. After being exposed to a large amount of positive information, tourists are often more inclined to meet the societal expectations of the “ideal tourist”. The dissemination of such external information reinforces the role of social norms. Through the spread of electronic word-of-mouth, tourists’ choices are not only driven by personal interests but also significantly influenced by social pressures, thereby impacting their travel decisions.

Moreover, ID significantly influences PBC. Destination-related information promoted through social media and travel websites (such as real-time navigation, accommodation options, and activity arrangements) provides tourists with comprehensive and instant decision support, greatly reducing uncertainty in their travel planning. This convenience enhances tourists’ confidence and sense of control over their travel decisions, thereby strengthening their perceived behavioral control. Additionally, the interactivity and transparency of digital platforms further enhance tourists’ sense of control over their travel decisions, making them feel more autonomous and capable of making more confident choices.

Furthermore, innovations in tourism marketing further enhance the effectiveness of ID. This digital promotion model not only strengthens the accessibility of information but also amplifies tourists’ behavioral intentions through visual and interactive elements. For example, Wang and Xu suggest that, from a community perspective, the intensity of destination promotion and its overall image play a crucial role in the development of tourism destinations [

67]. Therefore, the following hypotheses can be proposed:

H6. Information dissemination significantly influences tourists’ subjective norms.

H7. Information dissemination significantly influences tourists’ perceived behavioral control.

2.3.5. Policy Support

PS is a key driving factor in promoting the sustainable development of tourism destinations, particularly in enhancing tourists’ PBC. PS is an indispensable component of tourism [

67]. By providing quality tourism infrastructure, clear policies and regulations, effective rural tourism planning, and supervision of tourism stakeholders, the government can significantly enhance tourists’ confidence and sense of control over their tourism experience. Furthermore, to achieve sustainable development, tourism destinations should implement appropriate sustainability policies [

68,

69].

First, the development of infrastructure is a key manifestation of PS. Scholars and policymakers unanimously agree that infrastructure development plays a crucial role in sustaining tourist numbers and driving overall economic growth [

70,

71]. PS for sustainable tourism, such as the development of reliable transportation networks and clean tourism facilities, can reduce uncertainties faced by tourists during their journeys and enhance their sense of control over the destination, thereby improving their overall travel experience. Research indicates that transportation and communication infrastructure driven by policy funding can significantly promote economic growth and social development [

72]. This means that it significantly increases tourists’ ability to access travel destinations.

Second, the implementation of policies and regulations provides tourists with a clear framework for behavior. By introducing environmentally friendly policies, reducing overdevelopment, and strengthening institutional safeguards for rural tourism, the government can shape tourists’ sense of responsibility and enhance their decision-making ability during travel. Additionally, effective policies, destination management, and stakeholder accountability play a crucial role in mitigating the inevitable issues associated with tourism activities [

73]. From the perspective of the Self-Efficacy Theory, when individuals perceive that external structures and policies facilitate their actions, their self-efficacy increases, reinforcing their belief in successfully carrying out a behavior [

74].

In addition, tourism policies and destination management can effectively describe the competitive attributes of a destination, including experiences, knowledge, and tourism-related information [

75]. At the same time, they also enhance the positive impact of local residents on the tourism destination community [

76,

77]. They enable tourists to gain a better understanding of the destination’s sustainability concept, thereby strengthening their PBC. Therefore, the following hypothesis can be proposed:

H8. Policy support significantly influences tourists’ perceived behavioral control.

2.3.6. Personal Attitude

Attitude is a psychological tendency through which individuals express their positive or negative evaluations of objects or experiences [

78]. In the tourism industry, the study of attitudes from various perspectives has garnered widespread attention. For instance, research has been conducted on the influence of attitudes on destination choice [

79]. Kim et al. [

80] research confirms that PA has a significant and direct impact on an individual’s BI. This article also evaluates the effectiveness of the TPB through a meta-analytic review and confirms the substantial influence of PA on BI [

81]. Therefore, the following hypothesis can be proposed:

H9. Personal attitude influences tourists’ revisit intention.

2.3.7. Subjective Norms

SNs refer to societal expectations regarding individual behavior. In particular, the influence of social opinions, recommendations from friends, and social media can significantly impact tourists’ behavioral decisions. In cultural tourism, social media and electronic word-of-mouth are especially important as tourists’ travel decisions and revisit intentions are strongly influenced by the behaviors and opinions of others. Previous studies have already explored the impact of SNs on purchase intentions. SNs have a significant and direct influence on an individual’s BI [

80]. The research findings of Hasan, German, and others also indicate that SNs and PBC have a strong influence on consumers’ perceived value in green purchase intentions, exerting a positive impact on their decision-making [

82,

83]. Moreover, in developing countries, there is a significant relationship between subjective norms and purchase intentions. Positive information spread through electronic word-of-mouth and social network channels significantly enhances tourists’ sense of identification with the destination and their BI. This social influence further drives their intention to revisit the destination. Therefore, the following hypothesis can be proposed:

H10. Subjective norms influence tourists’ revisit intention.

2.3.8. Perceived Behavioral Control

PBC and habits have a significant and direct impact on an individual’s behavioral intention [

80]. PBC refers to tourists’ perception of control over their travel decisions. In particular, in complex travel environments, tourists’ strong sense of control can influence their behavioral intentions. According to the study by Roh et al., customers’ perceived green value affects their attitudes toward consuming organic food [

84]. Therefore, the following hypothesis can be proposed:

H11. Perceived behavioral control influences tourists’ revisit intention.

2.3.9. Revisit Intention

Revisit intention refers to the likelihood of tourists choosing the same destination again in the future. This is typically manifested as tourists considering whether they will revisit a destination based on their previous travel experiences, cultural attractions, or the characteristics of the destination. Many contemporary concepts and empirical studies have examined both first-time and repeat tourism behaviors [

85,

86,

87]. These studies aimed to determine whether there is a correlation between previous visits and the intention to choose the same destination in the future. By exploring the relationship between tourists’ familiarity with a destination and their intention to revisit that destination or other tourist sites within the same country/region, these researchers offer a relatively uncommon perspective that enriches the existing literature.

Related studies suggest that tourism experience in ethnic minority regions involves a variety of factors, with particularly notable findings from multi-group analyses that reveal differences in tourists’ personal attitudes, behavioral intentions, and revisit intentions. These studies emphasize that tourists’ revisit decisions are closely linked to the design of cultural tourism experiences. At the same time, satisfaction is widely regarded as a key factor in understanding destination performance [

88].

Tourist satisfaction arises from the extent to which the travel experience meets the tourists’ desires, expectations, and needs [

89]. Traditional perspectives suggest that satisfaction leads to repeat purchase behavior and positive word-of-mouth recommendations in the post-consumption phase. The marketing literature has extensively focused on the relationship between customer satisfaction and loyalty [

90,

91,

92]. According to this perspective, customers’ intention and desire to repurchase something are typically closely linked to their satisfaction with the product or service. When customers have a positive experience, they are more likely to engage in repeat purchasing behavior. This view posits that customers’ repurchase intentions and desires are strongly associated with their satisfaction levels. When customers are satisfied with the experience, they are more inclined to make the decision to repurchase the product or service [

93]. Related studies suggest that tourists use the perceived image of a destination to form expectations, which they then compare to their post-travel experiences [

89]. As a result, a favorable image of a destination boosts the chances of making positive assessments of the trip and strengthens the intention to return and suggest the destination to others.

Although previous research has identified various factors influencing tourists’ behavioral intentions, comprehensive cross-variable analyses of revisit intentions remain relatively scarce, especially in the context of cultural tourism. This paper aims to explore the key factors influencing tourists’ revisit intentions in depth, providing a comprehensive analysis within the framework of the Theory of Planned Behavior. By integrating cultural, social, and policy perspectives, this study offers theoretical support for the sustainable development of ethnic cultural tourism destinations and provides empirical evidence to assist destination managers in formulating targeted marketing strategies and policy frameworks.

2.4. Conceptual Model

The above sections provide a comprehensive examination of the theory of RI and sustainable development in ethnic cultural tourism, with particular emphasis on factors such as CR, ER, and PS, which influence tourists’ decision-making processes. The introduction outlines the research background by focusing on the rapid growth of cultural diversity protection and the demand for ethnic cultural tourism in the context of globalization. This background reveals how to promote sustainable economic development while protecting culturally distinct minority regions, thus highlighting the importance of understanding tourists’ RI and its sustainable impact. This study adopts the TPB as the research framework to systematically explore the factors influencing RI in ethnic cultural tourism, effectively integrating academic findings related to cultural tourism decision-making. The core focus on PA, SNs, and PBC in relation to RI aligns closely with the complexities of ethnic cultural tourism decision-making.

Moreover, the academic literature acknowledges the limitations of the TPB in capturing the multidimensional complexity of culture-driven BI. This study extends the TPB framework by incorporating CR, ER, SAs, ID, and PS as key exogenous variables and provides an in-depth exploration of how these variables jointly influence RI through PA, SNs, and PBC. Each section of the literature review offers a detailed analysis of the theoretical foundations and empirical evidence for these key factors, including the role of CR in shaping PA, the reinforcing effect of PS on PBC, and the influence of SAs on PBC, among others. By integrating relevant theoretical perspectives and empirical studies, this research proposes a series of hypotheses aimed at revealing the mechanisms underlying RI in ethnic cultural tourism, while providing a theoretical basis for sustainable tourism behavior.

Additionally, the literature review highlights the importance of moderating factors, such as digital information dissemination and social influence. These factors are particularly crucial in understanding the behavioral decision-making of ordinary tourists as travelers increasingly rely on social media and informational promotions in their tourism choices. This study incorporates these moderating factors into the extended TPB framework, which not only enhances the explanatory power of the model but also provides a new perspective on the impact of the integration of culture and technology on tourists’ RI. By integrating these key factors, this research aims to fill the theoretical and practical gaps in the study of ethnic cultural tourism behavior and offer theoretical support for optimizing the design and marketing strategies of ethnic cultural tourism destinations.

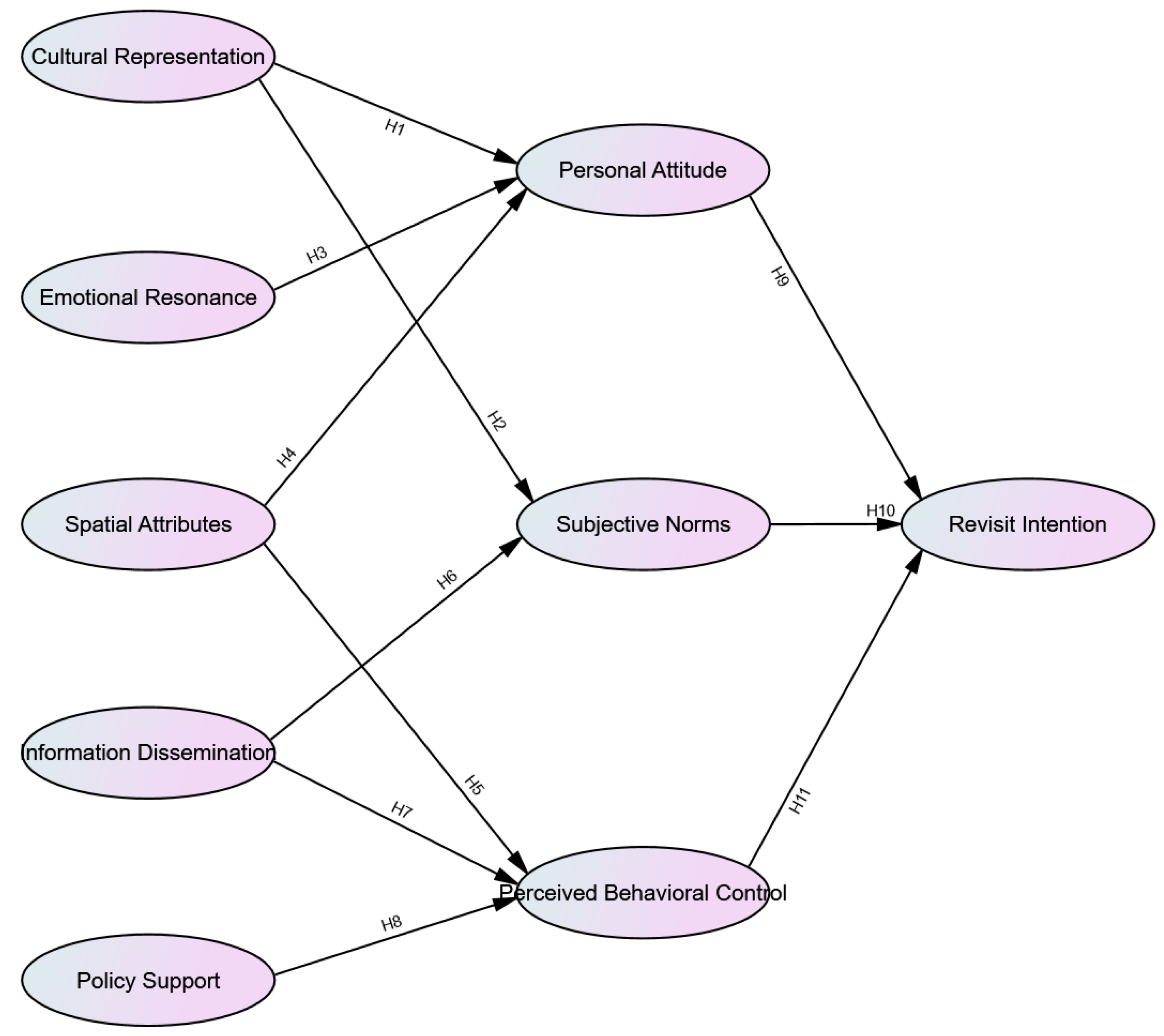

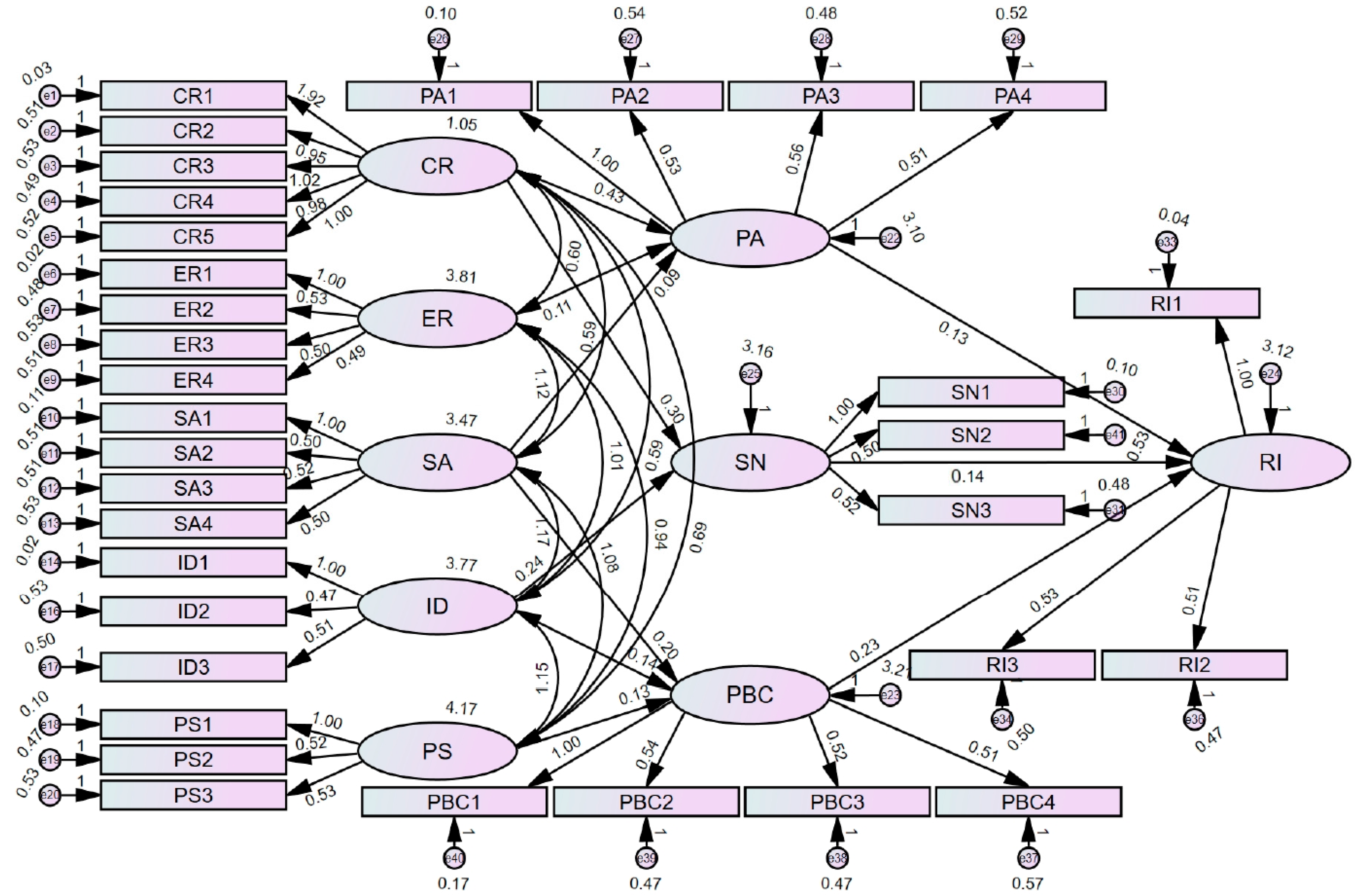

Overall, the literature review provides a solid foundation for the theoretical framework of this study, identifies the gaps in the existing research, and proposes corresponding hypotheses. These hypotheses will guide the development of the extended TPB model in this research. By demonstrating the validity of the selected theoretical structure, this study establishes a basis for the subsequent empirical analysis. Building upon previous research, the proposed research hypothesis model is presented in

Figure 1.

2.5. Previous Studies and Research Objectives and Contributions

In recent years, the study of revisit intentions in tourism has garnered significant attention, particularly in the context of sustainable tourism development. Previous research has explored various factors influencing tourists’ decisions to revisit destinations, including destination image, perceived value, and emotional attachment [

2,

6]. However, much of this research has focused on general tourism contexts, with limited attention given to the unique cultural and social dynamics of ethnic minority tourism destinations. Studies such as those by Yang et al. [

4] and Li et al. [

13] have highlighted the importance of cultural representation and emotional resonance in shaping tourists’ experiences in ethnic regions; yet, these studies often lack a systematic framework to analyze how these factors influence revisit intentions.

Moreover, while the TPB has been widely applied in tourism research to predict behavioral intentions [

19,

29], its application in the context of ethnic tourism branding remains underexplored. Existing studies have primarily focused on traditional tourism environments, with limited consideration of how cultural, emotional, and spatial factors interact to influence tourists’ attitudes and revisit intentions [

30]. For instance, research by Chen [

35] and Jangra et al. [

38] has emphasized the role of cultural elements and infrastructure in enhancing tourist satisfaction, but these studies often fail to integrate these factors into a cohesive theoretical framework.

Additionally, the role of information dissemination and policy support in shaping tourists’ perceived behavioral control and subjective norms has been acknowledged in the literature [

67,

68]. However, there is a lack of empirical studies that examine how these factors collectively influence revisit intentions in ethnic tourism destinations. This gap in the literature underscores the need for a more comprehensive approach that integrates cultural, emotional, and structural factors into the TPB framework to better understand the drivers of revisit intentions in ethnic minority regions.

By building upon these previous studies, this research aims to address these gaps by providing a systematic analysis of the factors influencing revisit intentions in ethnic tourism destinations. The integration of cultural representation, emotional resonance, spatial attributes, information dissemination, and policy support into the TPB framework offers a novel perspective on how these factors collectively shape tourists’ attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control, ultimately influencing their revisit intentions.

To address these research gaps, this study makes several significant contributions:

Promoting Sustainable Tourism Branding in Ethnic Regions: Previous research has predominantly focused on traditional tourism environments, with limited attention to the factors driving tourists’ revisit intentions. At the same time, consumer preferences have evolved with changing times. Grounded in the present, this study offers strong timeliness by exploring which brand attributes can effectively enhance the sustainability of tourism destinations in ethnic regions, providing theoretical support for branding strategies in culturally unique areas. Furthermore, the existing research lacks survey-based and quantitative analyses, particularly in the context of low revisit rates and insufficient focus on ethnic minority tourism. This study addresses this gap through quantitative methodologies.

Integrating the TPB into the Conceptual Framework for Sustainable Ethnic Tourism Branding: Although the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) has been widely applied in tourism behavior research, its use in the design of ethnic tourism branding remains limited. This study extends the TPB framework by analyzing how brand elements such as cultural representation, emotional resonance, spatial attributes, information dissemination, and policy support influence tourists’ attitudes, perceived behavioral control, and social norms, thereby enhancing revisit intentions. Additionally, this research introduces a chain-like thinking approach, comprehensively considering the decision-making process of tourists from pre-trip promotion to post-trip experience design.

Providing Practical Insights for Sustainable Tourism Development: This study offers practical recommendations for destination management organizations (DMOs), policymakers, and tourism operators, assisting them in formulating effective branding strategies to enhance tourist loyalty and revisit intentions, thereby ensuring the economic and cultural sustainability of ethnic tourism destinations. The research also highlights the evolution of tourist preferences over time, emphasizing the need for experience-based insights that reflect current trends rather than relying solely on past findings.

As a specific contribution, this study identifies the key factors influencing tourists’ revisit intentions and proposes a framework for leveraging local characteristics to design tailored tourism experiences. This approach not only enhances visitor engagement and repeat visitation but also provides a foundation for developing culturally distinctive tourism offerings, thereby addressing the challenge of homogenization and contributing to the sustainable development of regional tourism industries.

In summary, this study contributes to the literature by integrating destination branding, revisit intentions, and sustainable tourism design strategies within the context of ethnic tourism. It explicitly addresses the following research questions:

Which characteristics of tourism branding in ethnic minority regions are most effective in promoting brand sustainability?

How can the TPB be applied to design tourism branding that enhances tourists’ revisit intentions?

5. Discussion

The results of the empirical analysis yielded several key findings, which will be discussed in detail in the following sections.

H1 and H3 are valid, indicating that CR and ER are significant factors influencing PA. CR, as a symbolic representation of the destination’s culture, aligns with previous research that suggests iconic architecture, historical sites, and local arts not only provide tourists with engaging and interactive cultural experiences but also deepen their cognitive and emotional connection with the destination’s culture, thereby significantly impacting their PA [

36,

37,

38]. ER, on the other hand, enhances the emotional connection between tourists and the destination by evoking emotional responses, such as emotional engagement with local traditions, festive activities, or folk performances. This finding is consistent with previous research. When tourists’ emotional needs are met, their evaluations of the destination become more positive, which in turn fosters the development of a more favorable personal attitude. Additionally, studies have shown that cultural identity is positively correlated with behavioral attitudes. As cultural identity strengthens, individuals tend to exhibit more positive behavioral attitudes [

100]. Therefore, cultural representation and emotional resonance not only influence tourists’ immediate feelings but also play a crucial role in the long-term decision-making process, becoming key factors that shape tourists’ attitudes and behavioral intentions.

Therefore, destinations should prioritize CR in their branding efforts by emphasizing local traditions, historical landmarks, and unique cultural experiences that attract tourists. This can be achieved by designing interactive cultural experiences, such as festivals or workshops, to foster a deeper emotional and cognitive connection with the destination. At the same time, destinations can enhance ER by curating personalized experiences, such as evoking emotional connections through local festivals, traditional performances, or community interactions. Establishing these experiences helps fulfill tourists’ emotional needs and creates a stronger attachment to the destination, thereby encouraging revisit intentions.

Hypotheses H5, H7, and H8 are supported, indicating that PS, SAs, and ID are significantly positively correlated with PBC. Specifically, PS significantly reduces tourists’ uncertainty in the travel decision-making process by providing clear regulations, financial incentives, and a favorable tourism environment, thereby enhancing their sense of behavioral control [

101]. From the perspective of the Self-Efficacy Theory, when individuals perceive that external structures and policies facilitate their actions, their self-efficacy increases, reinforcing their belief in successfully carrying out a behavior [

74]. For example, government investments and infrastructure development in the cultural tourism sector not only provide tourists with enhanced service experiences but also increase tourists’ trust in the destination through the implementation of sustainable tourism policies, thereby strengthening their perceived behavioral control over tourism activities. SP refers to the destination’s geographical location, transportation accessibility, and spatial agglomeration effects [

44]. According to the Self-Efficacy Theory, tourists’ confidence in their ability to navigate and experience a destination is shaped by external enablers, such as well-developed infrastructure and efficient transportation networks. At the regional level, it is essential to further enhance the integration of resources across various levels of government and relevant departments, maintain market order, create a fair competitive environment, and encourage innovation in rural tourism business models and industry formats, among other measures [

67]. These factors can influence tourists’ perceptions of destinations, leading to higher levels of satisfaction throughout the tourism experience. Locations with unique landscapes or cultural resources often stimulate tourists’ desire to explore while simultaneously enhancing their confidence in behavioral decision-making. ID, particularly through digital platforms, social media, and online reviews, effectively increases tourists’ cognitive affinity and provides real-time and transparent tourism information. In line with the Self-Efficacy Theory, easy access to accurate and timely information strengthens tourists’ confidence in their ability to make informed choices by reducing uncertainty and fostering a sense of control over their actions. This enables tourists to feel more in control and comfortable when selecting and planning tourism activities. The timeliness and accuracy of information directly impact tourists’ decision-making processes and strengthen their sense of behavioral control. Consequently, the synergistic effects of PS, SAs, and ID significantly enhance tourists’ perceived behavioral control in cultural tourism, thereby encouraging them to make more positive tourism decisions.

Therefore, to reduce uncertainty and enhance PBC, tourism destinations should focus on improving infrastructure, including clear signage, a well-developed transportation system, and efficient information dissemination. This will increase tourists’ confidence in navigating the destination, ensuring they feel in control of their itinerary and strengthening their determination to revisit. At the same time, ID plays a crucial role in enhancing PBC. Tourism authorities should leverage digital platforms and social media to provide real-time updates on local conditions, policies, and attractions, which will give tourists the confidence to make informed decisions during their visit. Additionally, clear and accessible information about transportation options, local attractions, and policies should be provided to tourists before and during their travels.

Hypotheses H2 and H3 are supported, indicating that CR and ID are significant factors influencing SNs. First, CR, as a symbol and manifestation of destination culture, effectively shapes tourists’ social identity and sense of belonging by conveying unique cultural elements, such as local traditional arts, architectural styles, and historical landmarks. These cultural elements not only stimulate tourists’ interest in the destination but also indirectly influence their social norms and behavioral expectations in decision-making by reinforcing their respect for and identification with the culture [

102]. When tourists recognize that a cultural destination possesses unique cultural values, they are more likely to be influenced by the cultural identity and social expectations of those around them, thereby forming behavioral attitudes that align with social norms. Cultural identity is positively correlated with subjective norms, and as cultural identity strengthens, the influence of subjective norms becomes more pronounced [

100].

Second, ID, in the context of increasingly advanced information technology today, facilitates the rapid spread of information regarding the reputation of tourist destinations [

103,

104]. Any behavior or event that undermines the reputation of a tourist destination can have devastating impacts on the destination. Therefore, destination managers and administrators should not merely focus on their own service elements—such as service fairness, service quality, and perceived value—but should also adopt a comprehensive multifaceted approach to cultivating a positive reputation over the long term. By doing so, they can enhance tourists’ sense of identification with the destination, thereby increasing their loyalty to the destination [

65]. In particular, in the digital age, channels such as social media, electronic word-of-mouth, and online reviews have become significant forces in shaping tourists’ SNs. ID not only provides relevant information about destinations but also subtly influences tourists’ behavioral decisions. On social media platforms and travel-sharing websites, tourists’ comments, ratings, and recommendations from friends or opinion leaders have a substantial impact on other tourists’ BI. Through ID, the tourism information that tourists obtain becomes more diversified and transparent, thereby making their decisions not solely based on their own interests and preferences but also significantly influenced by opinions within their social networks. Additionally, if tourists have a high propensity to revisit a destination they identify with, they are more willing to disseminate information to others [

65]. Therefore, the development of rural tourism destination images should be approached from the perspective of establishing deeper and more enduring emotional connections, enhancing distinctiveness and identification, cultivating customer loyalty, and extending the lifecycle.

Therefore, tourism destinations should encourage positive online discussions and reviews through marketing and community engagement, thereby shaping SNs. Tourism managers should develop strategies to foster positive user-generated content and reviews from tourists who strongly identify with the destination’s culture, creating an atmosphere where tourists feel social pressure to revisit based on peer recommendations and the influence of social media.

Hypotheses H9, H10, and H11 are supported, indicating that PA, SNs, and PBC are significantly positively correlated with RI. First, PA has a direct positive effect on RI. When tourists hold a positive attitude toward a destination, they are more inclined to revisit it. This positive attitude typically arises from tourists’ strong recognition of the destination’s cultural appeal, the quality of the tourism experience, and factors such as ER. If tourists have a favorable experience during their initial visit, such as profound cultural engagement or emotional resonance, their satisfaction with the destination is significantly enhanced, thereby increasing their RI.

Second, SNs, as a social and cultural factor guiding tourist behavior, also play a crucial role in RI. Influences within the social circle, such as recommendations from friends and family or positive reviews on social media, usually motivate tourists to develop a willingness to revisit. In particular, when tourists observe others’ travel experiences and recommendations on social platforms, these external opinions can strengthen their decision-making confidence, thereby affecting their RI. Additionally, SNs encompass tourists’ recognition of social expectations and cultural norms, and this sense of identification encourages tourists to adhere to social and cultural behavioral patterns, further influencing their RI.

Finally, PBC significantly impacts tourists’ RI. Perceived behavioral control assesses tourists’ perception of the controllability of their revisit behavior. When tourists perceive lower complexity and uncertainty in travel, they are more likely to decide to revisit. For example, convenient transportation facilities, transparent tourism policies, and comprehensive tourism infrastructure can significantly enhance tourists’ sense of behavioral control, reducing uncertainty during the travel process. This sense of control fosters confidence in the feasibility and convenience of revisiting, thereby promoting their choice to revisit the same destination in future travels. Consequently, the stronger the sense of behavioral control, the higher the RI of tourists. Similarly, related studies have demonstrated that PA, SNs, and PBC positively influence tourism consumption intentions [

100]. This is consistent with previous studies, which indicate that personal attitudes, social influences, perceived behavioral control, and habits have a significant and direct impact on an individual’s behavioral intentions [

80].

To encourage RI, destinations should strengthen positive PA by offering unforgettable cultural experiences and high-quality tourism services. Fostering positive word-of-mouth from satisfied tourists will further solidify their attitudes and influence their future decisions to revisit the destination. Additionally, destinations can enhance PBC by improving accessibility and reducing barriers to revisit. This may include simplifying transportation options, offering special discounts for repeat visitors, and providing clear information about travel requirements. Making the revisit process more convenient will increase PBC and boost revisit intentions.

Hypothesis H4 is not supported, indicating that there is no significant correlation between SAs and PA. Although SAs may have some impact during the initial stages of attracting tourists—for example, a naturally scenic area with convenient transportation or a unique geographical location can stimulate tourists’ interest and desire to explore—it does not significantly affect tourists’ deeper attitudes. According to Stanovčić et al. (2021), multiple dimensions of cultural tourism experiences (such as sensory, social, and emotional experiences) exert a stronger influence on tourists’ behaviors and attitudes than geographical location or SAs [

105]. PA is more easily influenced by factors such as local culture, social atmosphere, and the emotional connections between tourists and destinations, which are not directly related to spatial endowment. For example, although certain locations may possess advantageous geographical positions, the absence of rich cultural activities, high-quality tourist experiences, or comprehensive services may prevent significant improvement in tourists’ personal attitudes. Stanovčić et al.’s research indicates that the quality and interactivity of cultural tourism activities have a significant impact on tourists’ attitudes and behaviors [

105]. Specifically, experiences in the sensory and emotional dimensions often determine whether tourists are willing to recommend a destination or develop revisit intentions [

105]. Therefore, SAs may play a certain role in attracting tourists during the initial stages, but their influence on tourists’ deeper attitudes is relatively limited. Tourists place greater emphasis on the cultural depth of the destination, the richness of tourism activities, and their overall experience.

6. Implications of This Study

6.1. Theoretical Significance

The theoretical significance of this study lies in its comprehensive exploration of the driving factors behind tourists’ revisit intentions in ethnic minority tourism destinations. By integrating these factors with the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB), this study identifies five key variables—cultural representation (CR), emotional resonance (ER), spatial attributes (SAs), information dissemination (ID), and policy support (PS)—that significantly shape tourists’ revisit intentions. Revisit intention is a critical factor for the long-term sustainable development of tourism brands. However, existing TPB models rarely account for the influence of cultural, emotional, and spatial factors on tourists’ revisit intentions in the context of ethnic minority tourism destinations. This study addresses this gap by expanding the TPB framework and providing a theoretical foundation for understanding revisit intentions in such unique cultural settings.

First, revisit intention is influenced not only by tourists’ personal attitudes (PAs), subjective norms (SNs), and perceived behavioral control (PBC) but also by critical cultural factors such as cultural representation and emotional resonance. Cultural representation, manifested through rich cultural elements and unique tourism experiences, enhances tourist satisfaction and strengthens emotional attachment to the destination, thereby fostering revisit intentions. Emotional resonance, as a deep emotional connection between tourists and the destination, significantly shapes tourists’ personal attitudes and increases the likelihood of revisit intentions through meaningful emotional interactions. These findings extend the applicability of the TPB in explaining tourists’ revisit intentions and offer a novel theoretical perspective for understanding tourist behavior in ethnic cultural tourism.

Second, the roles of spatial endowment and information dissemination in shaping revisit intentions are also pivotal. This study reveals that well-developed infrastructure and convenient transportation networks enhance tourists’ perceived behavioral control, reduce travel-related uncertainties, and thus increase revisit intentions. Simultaneously, information dissemination through positive electronic word-of-mouth and social media effectively shapes tourists’ social expectations and decision-making processes, further influencing their revisit intentions. Policy support, through government initiatives in tourism infrastructure, cultural preservation, and tourism management, boosts tourists’ travel confidence and provides a robust foundation for the formation of revisit intentions.

Third, this study advances the application of the TPB in the context of sustainable tourism branding, particularly in ethnic tourism destinations. While the TPB has been widely applied in fields such as consumer behavior and health studies, its application in sustainable tourism branding remains underexplored. By introducing cultural factors, this study enriches the theoretical landscape and provides new insights into the role of culture in shaping brand loyalty and revisit intentions. The findings demonstrate that tourists’ attitudes, subjective norms, and PBC are influenced not only by their cultural backgrounds but also by their cognitive and emotional connections to tourism brands. This research opens new avenues for the further development of the TPB, particularly in cross-cultural tourism studies and brand behavior research.

Fourth, this study underscores the importance of cultural factors in tourism brand design, especially in the development of ethnic tourism destinations. The results highlight that cultural identity plays a crucial role in driving tourists’ brand loyalty and revisit intentions. This study challenges existing theories by revealing how tourists’ emotional and cognitive responses to cultural elements influence their decision-making processes. Based on these findings, future research could explore the integration of the cultural adaptation theory with the TPB to further enrich the theoretical framework. Additionally, scholars could investigate how cultural adaptation and social norms intersect with brand loyalty in tourism, particularly through cross-cultural comparisons. Such research would refine the theoretical framework for sustainable tourism brand design by providing insights into behavioral differences across diverse cultural groups.

In summary, this study extends the TPB by integrating multidimensional factors—such as culture, emotion, space, and policy—into the understanding of tourists’ revisit intentions in ethnic minority tourism destinations. While revisit intention has been extensively studied in general tourism, the unique cultural contexts and specific needs of ethnic minority regions have often been overlooked. By incorporating factors like cultural representation and emotional resonance, this research fills a critical gap in the literature and offers a new theoretical lens for understanding tourist behavior in ethnic cultural tourism. Furthermore, this study examines how ethnic cultural features influence tourist loyalty, proposing a new theoretical framework that links cultural factors to brand sustainability—an aspect that has not been sufficiently addressed in the existing research. The interdisciplinary approach, combining tourism studies, psychology, and cultural research, provides novel insights into tourism branding and visitor behavior, particularly in ethnic destinations. Ultimately, this study not only enriches the TPB model by incorporating these additional factors but also lays a theoretical foundation for the sustainable development of ethnic minority tourism destinations, offering both practical and theoretical contributions for future research and targeted marketing strategies.

6.2. Practical Significance

In the tourism brand development of ethnic minority regions, the tourist revisit rate is considered a core indicator of the destination’s long-term sustainability and brand loyalty. Through an in-depth analysis of tourists’ revisit intentions, this study reveals the important role of five factors—CR, ER, SAs, ID, and PS—in driving tourists’ revisit behavior. This research provides empirical support for the sustainable development of ethnic cultural tourism destinations.

First, tourists’ revisit intentions are not merely a short-term market response but also a key factor that involves long-term tourist loyalty, sustainable local economic growth, and cultural transmission. Destinations with high revisit rates can significantly enhance the economic benefits of tourist attractions and strengthen the local brand image. By exploring the factors influencing revisit intentions, this study provides a clear direction for the construction of ethnic minority tourism brands.

The practical significance of this study lies in its contribution to filling the gap in the existing academic research on the relationship between revisit rates and the brand development of ethnic minority cultural tourism. The findings offer actionable recommendations for destination managers and policymakers, providing them with a clearer understanding of how to design targeted branding strategies that enhance visitor experience and foster tourist loyalty. By analyzing the perspectives of key stakeholders, this study offers practical guidance for the development of tourism strategies in ethnic regions, helping policymakers and tourism professionals achieve the sustainable development goals of these areas. The research also emphasizes the importance of strengthening tourist loyalty as a key factor in ensuring long-term success. Additionally, this study calls for future research to expand its scope and incorporate a variety of data sources to improve the comprehensiveness of the findings. This would help enhance the tourism industry’s ability to meet the diverse needs of visitors, ultimately improving tourist satisfaction and contributing to the future development of the sector.

The research results provide strong support for tourism brand development; however, factors such as regional economic conditions, cultural diversity, and local policies may influence the applicability of the findings. For instance, economic disparities across regions could affect resource allocation for tourism development, while cultural diversity might shape tourists’ preferences and behaviors. Additionally, local policies could either facilitate or hinder the implementation of recommended strategies, depending on their alignment with sustainable tourism goals and local development priorities.

7. Conclusions

Sustainable development, as a central principle of growth, exerts significant economic, environmental, and social impacts. The growth of the tourism industry is closely linked to the three dimensions of sustainability in the modern world. As global economic, social, and environmental systems continue to expand, analyzing new approaches to sustainability is crucial for the tourism sector [

101].

This study employs empirical analysis to reveal the influence of multiple factors on tourists’ RI and delves into the formation mechanisms of cultural tourism destination attractiveness and tourist behavior through the TPB framework. The research findings indicate that CR and ER significantly impact tourists’ PAs. Specifically, CR enhances tourists’ cultural identity and ER by showcasing cultural elements such as historical sites, architectural styles, and local arts, thereby contributing to the formation of a more positive PA. ER, in turn, deepens the emotional connection between tourists and destinations by eliciting emotional responses, particularly through participation in local festivals and cultural experiences. This emotional investment plays a crucial role in shaping tourists’ PAs.

Furthermore, PS, SAs, and ID have significant positive effects on tourists’ PBC. PS, through government investment and infrastructure development, provides higher-quality services and a favorable tourism environment, thereby enhancing tourists’ trust and reducing decision-making uncertainty. While SAs positively influence the initial attraction of tourists—such as through advantageous geographical locations and convenient transportation—it has a limited impact on tourists’ deeper PAs. Tourists’ PAs are more readily influenced by factors like local cultural atmosphere, social interactions, and ER, indicating that SAs play a role in the early stages of attraction but are not a key determinant of deep-seated PAs. ID plays a significant role in shaping tourists’ SNs, especially in the digital age, where online reviews, ratings, and recommendations on social media platforms and travel-sharing websites influence tourists’ BI. Through ID, the tourism information accessed by tourists becomes more diversified and transparent, enabling decisions that are influenced not only by personal interests and preferences but also by opinions within their social networks.

Finally, this study demonstrates that PA, SNs, and PBC have significant positive effects on tourists’ RI. Tourists who hold positive PAs towards a destination after their initial visit and are influenced by their social circles and societal expectations are more inclined to revisit. Additionally, when tourists perceive a higher level of control over their travel, such as through convenient transportation and transparent policies, their RI is significantly enhanced.

In summary, this research provides important theoretical support for the management and marketing strategies of cultural tourism destinations, emphasizing the critical roles of CR, ER, ID, and PS in enhancing tourists’ RI. These findings assist tourism destinations in better understanding the behavioral motivations of tourists and offer strategic guidance for achieving long-term visitor retention and sustainable development.

8. Future Avenues of Research

Although this study provides valuable theoretical and empirical support for exploring the relationship between tourists’ revisit intentions and brand development at ethnic minority tourist destinations, there is still room for improvement. First, the sample in this study is primarily focused on ethnic minority tourist destinations within China. Future research could expand the sample to include other countries or regions to more broadly verify the relationship between revisit rates and brand development. Second, this study employs cross-sectional data analysis, which, while useful for revealing the current situation, does not fully address the dynamic changes in revisit intentions. Therefore, future research could adopt a longitudinal design to track changes in tourist behavior, offering deeper insights into the long-term relationship between revisit behavior and sustainable development.

Additionally, this study focuses on variables such as cultural representation, emotional resonance, spatial endowment, information dissemination, and policy support. Future research could further expand the range of variables to include factors such as tourist personality traits and socio-cultural background, thus providing a more comprehensive analysis of the driving mechanisms behind revisit rates. While Structural Equation Modeling was used for data analysis, quantitative methods may not have fully captured the emotional and psychological aspects of tourists’ revisit behavior. Future research could combine qualitative methods, such as in-depth interviews, to explore the underlying factors in the formation of revisit intentions.

Finally, cultural differences may influence tourists’ revisit behavior. Although this study did not delve deeply into this factor, tourists from different ethnic and cultural backgrounds may exhibit different patterns of revisit behavior. Therefore, future research should further consider the impact of cultural differences on revisit rates. In summary, future studies could optimize sample selection, research design, variable expansion, and methodological innovation to more comprehensively explore the impact of revisit rates on the sustainable development of ethnic minority tourist destinations.