Abstract

This study examines the impacts of women’s social, political, and psychological empowerment on their participation in civil societies and further its impacts on their entrepreneurial resilience. This study employed the quantitative approach, and data were collected through surveys, which were later analyzed with Smart PLS 4. This study’s findings revealed mixed results. The impacts of psychological and social empowerment on women’s participation in civil societies and their entrepreneurial resilience were significant. The impacts of political empowerment on women’s participation in civil societies and their entrepreneurial resilience were insignificant. The occurrence of disasters is common in tourist destinations, and several studies have investigated it. However, the study on the ripple impacts of disasters on women has not been thoroughly investigated, specifically in the Asian context.

1. Introduction

Tourism has been hailed as the salvation of many communities worldwide due to its potential to produce additional cash, support the economy, and create jobs [1]. However, many coastal areas and town destinations have been exposed to negative natural and social impacts, as well as catastrophes like floods, tsunamis, storms, droughts, landslides, forest fires, and diseases. Crises like droughts and floods are the most serious threats to a tourism-based country [2]. Heavy rains during the rainy season have recently caused significant flooding in Thailand, and the floods are wreaking chaos on critical tourist destinations [3]. The flooding severely damages the roads and highways connecting tourist areas, international airports, hotels, and tourist attractions. This disrupts the routine operations of tourism businesses and hinders their ability to cater to customers. The destination management authorities have expressed their thoughts that destination crises impact the tourists, but they impact the entrepreneurs harder. Study [4] mentions that women are increasingly involved in the tourism business, and there are multiple challenges they have to face. It is important to empower them as, in chaotic situations, they can sustain their businesses. Study [5] stresses the need to empower women entrepreneurs in Thailand to deal with crises and pandemics.

Women entrepreneurs in Thailand’s tourism sectors significantly contribute to the economy [6]. Women entrepreneurs encounter difficulties rebuilding their enterprises and restoring services, which have long-term consequences for their operations [7]. Furthermore, women entrepreneurs have difficulty obtaining financial resources to rehabilitate and enhance their business sustainability. Limited access to credit, insurance, and capital worsens their problems, making it more difficult for entrepreneurs to recover from the disaster’s economic consequences [8]. Individuals’ safety and wellbeing, especially those of women, are jeopardized by natural catastrophes. They are subjected to physical damage, relocation, or trauma, which can have long-term consequences in their personal and professional life. Personal safety becomes a concern, causing some women entrepreneurs to temporarily halt or terminate their business operations [9].

Natural catastrophes potentially disrupt supply chains, reducing the availability of products and services required by entrepreneurs. This results in shortages, increased expenses, and operational challenges. Furthermore, lower tourism demand in disaster-affected areas severely influences women entrepreneurs who rely mainly on tourists for their business [10]. Natural catastrophes amplify existing gender biases and inequality in the tourist industry. Women entrepreneurs suffer prejudice, restricting their access to resources and recovery possibilities. To mitigate these threats, women’s empowerment is critical in building a trend toward equality [11].

In this specific circumstance, women’s empowerment for disaster resilience is required for planning and practical implementation in the tourism industry. Its outcomes include gender responsiveness standardization, anticipating women in disaster and emergency situations, ensuring women’s privileges, and improving their leadership abilities.

A prior study points out that psychological empowerment can considerably enhance entrepreneurial success. This dimension of empowerment, concentrating on self-awareness, knowledge acquisition, and financial freedom, positively affects business sustainability among women entrepreneurs in various sectors [12]. However, research, particularly on connecting psychological empowerment with entrepreneurial resilience within disaster perspective in the tourism industry, remains unexplored. Further, the impact of social and political empowerment on entrepreneurial outcomes is also prominent. For example, women’s participation in social entrepreneurship positively influences their economic and psychological empowerment [13], and political empowerment is associated with increased entrepreneurial activities [14]. Despite these results, there is inadequate evidence studying how these forms of empowerment directly influence entrepreneurial resilience in tourism-specific contexts. Furthermore, prior research has revealed that women’s participation in social enterprises builds their empowerment and capability to be involved in local economic growth [15]. However, studies that clearly concentrate on how women’s civil society involvement mediates the relationship between women empowerment and resilience in tourism entrepreneurship are limited, especially in Southeast Asia, such as Thailand. The gap lies in the incorporation of multi-dimensional women empowerment, women’s participation in civil society, and entrepreneurial resilience in the tourism sector of Thailand. This gap establishes possibilities for further research to discover how these variables interrelate and influence the success and sustainability of women entrepreneurs in the tourism industry.

Therefore, this study adopts a diverse dimension of women’s empowerment and examines the impact of these dimensions on disaster resilience. Further, women’s empowerment increases their involvement in tourism civil society, which helps and supports women entrepreneurs who are affected by natural disasters. Given its significance, this study aligns with the critical need to increase resilience to disasters, emergencies, and external shocks, reinforce supervision and social attachment, and improve gender and social equity. Therefore, this study investigates women’s empowerment, their assistance in disaster resilience, and how women’s empowerment helps foster women’s participation in Thailand’s civil society and disaster resilience.

This study highlights women’s empowerment in designing and implementing disaster resilience capacities in the tourism sector, with outcomes such as establishing some gender-responsive planning in crises and disasters for women’s rights protection and developing women’s leadership aptitudes. It aids in aligning civil societies on the strategic necessity of assisting female leaders in enhancing their flexibility during crises and catastrophes. Additionally, educational institutions would benefit from this study employing several teaching and learning practices that would empower women. This research also helps women leaders improve the social learning abilities necessary for disaster resilience.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Theoretical Underpinnings

The social constructionism theory holds that the ways individuals understand and categorize several aspects of human identity and experience are not predetermined by nature but rather socially constructed through language, culture, history, and shared belief [16]. Social constructionism and its adaptation have two major fundamentals. The first theme declares that society needs transformation, and the second theme provides learning a leading role in changing society. Therefore, social buildings and society empowerment are highly concerned about future predictivity and address uncertainties [17]. Human actions are attempted from an ethical angle, as each individual action performed has an outcome for its future consequences [18]. The operation of civil society is to construct a fairer human society, which shapes individual behavior in society. Further, ref. [19] highlights the key contribution of social constructionism to increase the betterment of society through individual and community participation. According to the study by [20], the content of social constructionism is derived from an assessment of the society that an individual intends to serve. This study is supported by social constructionism theory, which explains gender role and their constructive and collective identity. Social construction theory offers a comprehensive framework for considering the vibrant relationship between women’s empowerment (psychological, social, and political), civil society participation, and entrepreneurial resilience. Formed by the social construction of gender roles and norms, psychological empowerment is shaped by women entrepreneurs’ determination to reconstruct their self-identity within the business perspective. As they contribute to civil society, they receive endorsement and responses that improve their confidence and psychological strength, contributing to entrepreneurial resilience. Further, the social practices, empowerment, and shared beliefs support each other. As they challenge traditional responsibilities and cooperate with other women in entrepreneurial systems, they redefine what is possible for women in business to make a society resilient and immune to crisis. When it comes to entrepreneurship, specifically tourism entrepreneurship, empowering the rising segments of women becomes necessary to cultivate their social support. Moreover, political empowerment further interrupts gendered constructions of power. When women are politically involved in local governance or activism, they face patriarchal systems, forming a more helpful environment for entrepreneurial success. Their contribution to the political sphere fortifies their sense of assistance and constructs resilience to external pressures.

Along with it, civil society offers a space for these women to construct new standards and positions for themselves, which develops their power to bounce back from obstructions and push entrepreneurial growth. Eventually, entrepreneurial resilience is a collectively formed outcome of women’s empowerment. Women’s engagement in entrepreneurial ventures within Thailand rebuilds their individuality as entrepreneurs, overwhelming societal problems to accomplish long-term success and contribute to their societies’ development.

2.2. Role of Women in Entrepreneurship and Resilience

Women are progressively perceived as key participants in the entrepreneurial landscape. Traditionally, men have conquered entrepreneurship, but in recent decades, more women have moved into the business world, contributing to various sectors, including technology, education, retail, and tourism. Women’s entrepreneurial actions are significant in developing economies and are essential to community development and economic progress [21]. Further, women entrepreneurs participate extensively in innovation by familiarizing themselves with new ideas, products, and services, which, in turn, generate jobs and economic opportunities. They often pay attention to solving social problems, which leads to more comprehensive economic development [22]. Moreover, women’s entrepreneurship is directly connected to women’s empowerment. Successively running businesses enable women to become financially self-sufficient, make decisions, and challenge traditional gender roles [23]. Despite these confronts, many women prove resilience, a key element that allows them to direct and overcome these barriers [24]. As they succeed in entrepreneurship, women motivate others in their communities and establish a ripple effect, encouraging gender equality and social change [25].

2.3. Women’s Empowerment and Participation in Civil Society

Women entrepreneurs are important in the entrepreneurial age, and tourism is no exception. According to ref. [26], it is necessary to recognize a diversified paradigm of women’s empowerment that includes psychological, political, and social factors to understand women’s empowerment, facilitate civil societies, and ensure their entrepreneurial resilience [27]. Women’s empowerment is important in shaping their social position, making them resilient, and broadening their social participation and support to other women in disaster-hit destinations [28]. According to women empowerment-based studies, women’s economic participation in the industry is based on their psychological, political, and social empowerment [29]. The study by [30] highlights that women’s empowerment provides them with the confidence to participate in civil societies and makes them super resilient to face difficult situations. Moreover, ref. [31] asserts further that empowering women makes the tourism sector super resilient and, eventually, makes a country immune to crisis. Based on this, this study hypothesizes the following:

H1a.

Psychological empowerment significantly impacts participation in civil society;

H2a.

Social empowerment significantly impacts participation in civil society;

H3a.

Political empowerment significantly impacts participation in civil society.

2.4. Women’s Participation in Civil Society

The cornerstone of women’s action for the country’s evolution means that action for egalitarianism, growth, and communalism brings every woman to a level that would be considered resilient [32]. Civil societies usually do not fully involve the government and maintain contact with communities and societies to achieve their objectives [33]. Civil society is a monitoring entity that holds the government and institutions responsible, such as when certain civil society officials monitor environmental crises and send information to local communities and international organizations in other countries [34]. Furthermore, politically empowered women activists and spokespeople increase awareness of concerns by giving the voiceless a voice and advocating change, such as in the tourism sector, once entrepreneurs call for help [35]. As per ref. [36], civil society is a well-known contribution to creating global governance norms. According to ref. [37], civil societies are community-based institutions that are smaller but more locally oriented organizations that are open to people and the institutions’ governing bodies. Civil societies provide vast benefits and support to establish the normal state of destination as it had before the crises. Furthermore, ref. [38] stated that civil societies could develop a strategy to challenge the chaotic situation and shape their environments by fostering community connections. Women’s empowerment, which includes social, psychological, and political empowerment, is clearly visible in its contribution to their role and duties in civil society, which helps them to deal with disaster by making them resilient. Therefore, this study has proposed the following:

H1b.

Psychological empowerment and entrepreneurial resilience mediated by women’s participation in civil society;

H2b.

Social empowerment and entrepreneurial resilience mediated by women’s participation in civil society;

H3b.

Political empowerment and entrepreneurial resilience mediated by women’s participation in civil society.

2.5. Women’s Participation in Civil Society and Entrepreneurial Resilience

Women’s perceptions appear to concern a growing leadership position at several levels in numerous fields [39]. However, history demonstrated that women were maturing and playing a significant role in the survival of political parties and social movements. They propose a social transformation that connects thoughts and actions with emotions and sentiments to rebuild a new and better social association for a better society [40]. As a result, females’ participation in rebuilding a disaster-hit destination is rooted in several aspects of their culture, increasing the economic benefits to include social, psychological, and political dimensions [41,42,43,44]. More empirical studies are required to determine the role of women in dealing with disasters, enhancing their entrepreneurial resilience, and participating in civil societies to support other women entrepreneurs, which is a timely call. Therefore, this study investigates their level of participation in civil societies and making tourism-based entrepreneurship residents. Therefore, this study proposed the following hypothesis.

H4.

Women’s participation in civil society significantly impacts entrepreneurial resilience.

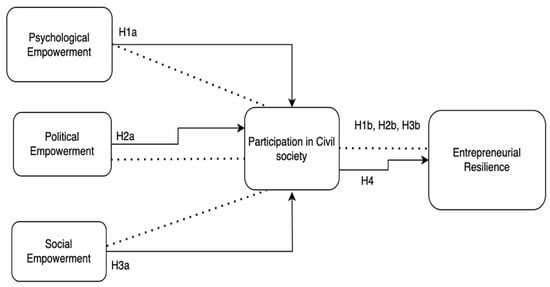

Further, Figure 1 shows the graphical picture of conceptual framework that contains the relationship between psychological empowerment, political empowerment, and social empowerment, to participation in civil society and entrepreneurial resilience as following:

Figure 1.

Conceptual Framework (Source: Author Own Creation).

3. Materials and Methods

This study employed the quantitative approach, collected the data through surveys, and focused on women entrepreneurs in Thailand’s tourism and hospitality sector. Thailand is considered one of the world’s top ten tourism destinations, and many women entrepreneurs are involved in the tourism and hospitality sector. The survey focused on women facing complications in their entrepreneurial actions during natural disasters. Data were collected from May to September 2024. Through purposive sampling, the responses were obtained from multiple cities in Thailand, specifically Phuket, Phang Nga, and Krabi, because of their geographical location and tourists’ footsteps. This study used twelve items to measure women’s empowerment, including social, psychological, and political empowerment adopted by [45]. Further, five items were used to measure participation in civil society, adopted from [46]. The ten-item scale of entrepreneurial resilience was borrowed from the study by [47], and the 7-point Likert scale measured all constructs. The questionnaire of this study is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Questionnaire of Study.

Further demographics of this study revealed that 76 respondents did not have formal education. A total of 107 respondents had a middle school education, and 127 had a senior high school education. Further, 67 had polytechnic education, 52 were undergraduate, and 29 respondents were postgraduate. From the age perspective, 118 respondents were under 26 years of age; 83 were between 26 and 35 years old; 78 respondents were between 36 and 44, and 63 respondents were between 45 and 53. Further, 62 respondents were between 54 and 62 years old, and 54 were above the age of 63. Mentioning the monthly income, 109 revealed that they earned below THB 20,000 monthly. A total of 104 had an income between THB 20,000 and THB 30,000; 69 revealed that they earned THB 40,000, and 83 respondents recorded their monthly income between THB 40,000 and THB 50,000. Only 93 mentioned monthly earnings of more than THB 50,000. When asked about building ownership status, 203 mentioned it as their own, and 255 mentioned it as a rented place.

3.1. Data Analysis Procedure

Before collecting data, this study performed a pretest and pilot test. For pretesting of the questionnaire, it was shared with three academicians, and minor changes were mentioned. The academicians highlighted repeating certain words, replacing specific terms with simple, understandable terms, and rewriting double-meaning sentences. They noted that the specific terms might be understandable by researchers but not by the public. After that, this study performed pilot testing and ensured the optimum value between 0.7 and 0.9 of Cronbach’s alpha [48]. After that, 500 questionnaires were dispersed, and 458 responses were used for further analysis through Smart PLS 4.

3.2. Assessment of Outer Model

This study has assessed its outer model through the PLS algorithm feature of Smart PLS, and following [49], this study warranted the common method bias issue of the data. The variance inflation factor values were below 3.3, following the [50]’s criteria. The model’s heterotrait–monotrait ratio (HTMT) was below 0.9, which satisfied the criteria [51]. The HTMT table of study is provided in Table 2.

Table 2.

HTMT.

Furthermore, the average variance of this model was above 0.5; loadings were above 0.6, satisfying the threshold limits [52]. It is important to mention the deletion of items due to lower loadings. This study has deleted one item from the construct of political environment because of its loading, which was 0.385, and reported AVE 0.584. After deletion, the AVE of the construct improved to 0.730. Further, one item was deleted from the construct of entrepreneurial resilience, the loading of which was 0.592 and reported as AVE 0.510. After the deletion of the item, AVE improved to 0.530. Before deletion, SRMR was 0.087, and after deletion, it improved to 0.084. However, [53] leaves the deletion of items on research context and choice of researchers involved in this study. However, deleting an item improves the model loadings, and removing it from the model is better. The loadings, average variance, composite reliability, and Cronbach’s alpha of this study are provided in Table 3.

Table 3.

Assessment of Outer Model.

3.3. Model Fit and Assessment of Inner Model

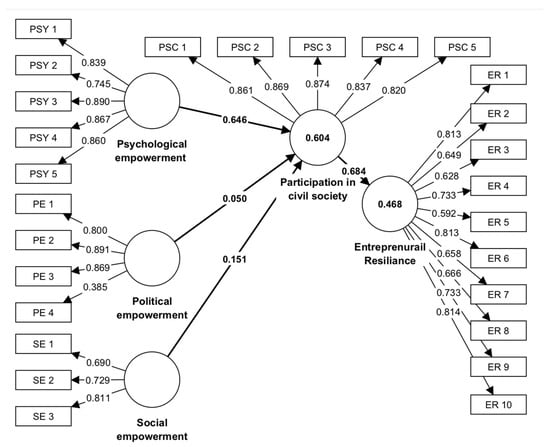

After assessing the inner model, the next step is to ensure that the model fits the inner model. The value of SRMR is 0.08, satisfying the threshold set by [54]. The value of predictive relevance Q2 of the model is 0.420, highlighting the model’s strength. As per the study by [49], the higher the value of Q2 is above zero, the stronger it indicates predictive relevance. Further, the effect size of this model is 0.931, and the value of the coefficient of determination is 0.482. As per [55], the value obtained for the normed fit index (NFI) closer to 1 ensures a better NFI fit; for this study, it is 0.78. The study by [56] revealed an interesting phenomenon, as this study checked NFI through CB-SEM and PLS-SEM. This study obtained a value of 0.93 for NFI through CB-SEM, and the value obtained through PLS-SEM was 0.89. It revealed that the PLS-SEM revealed a low value, and this current study also used PLS-SEM, which could be one of the reasons for low NFI values. Furthermore, the graphical representation of the model assessment is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Measurement model of this study (Source: Author’s Own).

4. Results and Discussion

The results of this study revealed the mixed findings. Before discussing the findings, it is important to highlight the demographics of this study. From a gender perspective, only women were considered, and other genders were not involved in this study. As per education level, the maximum number of women were undergraduates. In marital status, many women mentioned being separated or single. Although data from this study were obtained from small and medium-sized businesses, most respondents belonged to small-scale businesses. The findings of this study revealed the impacts of women’s empowerment on their participation in civil society.

This study’s first hypothesis mentions the impact of the psychological empowerment of women on their participation in civil society and further impacting entrepreneurial resilience. Analysis of this model revealed the significant results of H1a and H1b. The results of this hypothesis are aligned with this study by [57]. The next hypothesis of this study is to ensure the impacts of political empowerment on women’s participation in civil society and their entrepreneurial resilience. This study has found insignificant results, and the possible reason for this can be rooted in the contextual aspect or culture [58]. Findings on women’s empowerment in Thailand often highlight economic and social empowerment more than political empowerment. Women in rural areas or the tourism industry may be more engrossed in economic freedom and social empowerment through entrepreneurship rather than political involvement. These entrepreneurs may sense that direct business sustainability, rather than political involvement, is critical for their entrepreneurial resilience [59]. From the perspective of the tourism industry, practical resources, such as training, social support setups, and entrance to markets, may have a more critical impact than political contribution.

The third hypothesized relation of this study is investigating the impacts of the social empowerment of women on their participation in civil society and their entrepreneurial resilience. The results of this hypothesis are significant and are aligned with [60,61]. The fourth hypothesis of this study is investigating women’s participation in civil society and its impacts on their entrepreneurial resilience, which are aligned with the study by [62,63]. The results of the hypotheses of this study are illustrated in Table 4.

Table 4.

Hypotheses of Study.

5. Conclusions

5.1. Practical and Theoretical Implications

Despite the gendered effect of crises on their entrepreneurial activities, women entrepreneurs establish notable resilience, empowering them to support and even foster their ventures despite hardship. Therefore, this explanatory study, occupying a quantitative methodology, investigates the unique approaches that women entrepreneurs practice to enhance resilience and navigate severe experiences and encounters during crises. The outcomes of this study provide valued insights into the gendered and contextual dynamics of the resilience-building procedure. Sustainably operating the businesses empowers women to become financially self-contained, make choices, and confront traditional gender roles. Despite these confronts, many women show evidence of resilience, a key part that lets them direct and overcome these obstructions. As they thrive in entrepreneurial ventures, women encourage others in their communities and make a ripple effect, boosting gender parity and social change. Moreover, this study highlights the coping approaches women entrepreneurs use and discovers how these approaches add value to entrepreneurial and business resilience. The evolving model from this study works as an underpinning for developing theories on women entrepreneurs’ resilience in crisis. Furthermore, this model also delivers a deeper understanding of how women entrepreneurs confront multiple crises and how they navigate them and survive during hard times. From a practical context, this study offers valuable implications for policymakers, women entrepreneurs, and businesses.

Firstly, destinations integrating gender-responsive planning into disaster resilience frameworks recognize men’s and women’s different vulnerabilities and needs. Policies that support women’s access to resources, land tenure, and decision-making processes are crucial in ensuring entrepreneurial resilience. Tourism destinations can create gendered disaster risk reduction plans acknowledging women’s roles in community-based disaster management. Secondly, gender concerns must be considered while designing urban infrastructure. For instance, women, children, the elderly, and those with disabilities involved in businesses should all be able to access public areas and shelters safely and easily. Destinations may support gender-sensitive infrastructure that considers women’s access to emergency services, mobility, and safety during catastrophes.

Third, one important tactic is introducing training programs for women in climate change adaptation and disaster resilience. Topics like emergency preparedness, disaster risk reduction, and the use of technology for gathering climate data could all be included in these seminars. Tourism destinations can collaborate with civil society organizations to offer these programs and develop local competence. It can launch awareness campaigns emphasizing the value of women’s contributions to resilience-building. The significance of gender parity in disaster management can be brought to the attention of both men and women through these efforts. Fourth, local governments can set up systems to include women in decision-making, like forming climate committees with a women’s focus or women’s advisory councils. Planning for urban resilience can incorporate gender-sensitive strategies using these frameworks.

Fifth, tourism destinations might encourage collaborations between regional women’s organizations and international organizations to enhance women’s participation in disaster resilience. Women’s voices can be amplified in policy conversations via these alliances, giving them a forum to share their ideas, solutions, and experiences. Sixth, numerous initiatives headed by women have successfully increased community resilience to disasters. Local governments may help these movements by offering forums for visibility, training, and resources.

5.2. Limitations and Future Directions

This study has explained an important and comparatively overlooked segment. However, this study is not free of limitations and invites future scholars to work on it. This study’s first and foremost limitation is its gender restriction, which is specific to women. Future studies may involve unspecified genders. There was a limited number of participants above fifty years of age in the age group. However, involving older entrepreneurs can be an interesting topic. The contextual limitations of this study can be removed by incorporating several cultures and backgrounds. The questionnaire survey limited the opportunity for participants to explain the topic further, and a qualitative study could explain it further. This study has noted that the entrepreneurial aspects and investigating the destination managing authorities can provide deeper insights.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.S. and R.K.; methodology, M.R. and A.S.; software, L.I. and A.A.; validation, R.K. and M.R.; formal analysis, M.R.; investigation, R.K.; resources, R.K.; data curation, A.S.; writing—original draft preparation, A.S., R.K. and M.R.; review and editing, L.I. and A.A.; visualization, L.I.; supervision, L.I.; project administration, A.S., L.I. and A.A.; funding acquisition, L.I. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Research Center for Engineering and Management (no. 05/10.09.2024 for studies involving humans).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. They were informed that all data would be used for this research entitled “We can and must empower women to thrive through destination crisis: A study of women’s entrepreneurial resilience in the tourism sector”.

Data Availability Statement

The data are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Krannich, R.; Petrzelka, P. Tourism and natural amenity development: Real opportunities. In Challenges for Rural America in the Twenty-First Century; Penn State University Press: University Park, PA, USA, 2003; pp. 190–199. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, A.K.; Nair, S.S. Environmental Extremes Disaster Risk Management-Addressing Climate Change; National Institute of Disaster Management: New Delhi, India, 2012; p. 40.

- ECHO. Malaysia, Thailand—Floods, Update (NOAA-CPC, ADINet, Media) (ECHO Daily Flash of 20 December 2022); ECHO: Brussels, Belgium, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Filimonau, V.; Matyakubov, U.; Matniyozov, M.; Shaken, A.; Mika, M. Women entrepreneurs in tourism in a time of a life event crisis. J. Sustain. Tour. 2024, 32, 457–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukphan, J.; Satjasomboon, S. Challenges of Young Female Social Entrepreneurs in Post-COVID 19: A Case Study of Mueang Pon, Mae Hong Son, Thailand. Rajabhat Chiang Mai Res. J. 2023, 24, 65–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghouse, S.M.; Durrah, O.; McElwee, G. Rural women entrepreneurs in Oman: Problems and opportunities. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2021, 27, 1674–1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesnaya, O. Restoration of the Country Through Support of Entrepreneurship. SSP Mod. Econ. State Public Adm. 2022, 1, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, R.; Raza, M.; Sawangchai, A.; Raza, H. The Challenges to Women’s Entrepreneurial Involvement in the Hospitality Industry. J. Lib. Int’l Aff. 2022, 8, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rembiasz, M.; Siemieniak, P. Selected entrepreneurship support factors increasing women’s safety and work comfort. Syst. Saf. Hum.-Tech. Facil. 2019, 1, 120–125. [Google Scholar]

- Mittal, R.; Sinha, P. Framework for a resilient religious tourism supply chain for mitigating post-pandemic risk. Int. Hosp. Rev. 2022, 36, 322–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karam, C.M.; Afiouni, F. Localizing women’s experiences in academia: Multilevel factors at play in the Arab Middle East and North Africa. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2014, 25, 500–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, N.; Rony, R.J.; Sinha, A.; Ahmed, S.; Saha, A.; Khan, S.S.; Abeer, I.A.; Amir, S.; Fuad, T.H. Risk communication during COVID-19 pandemic: Impacting women in Bangladesh. Front. Commun. 2022, 7, 878050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lionanda, G.; Kurniawati, K. Analysis of the role of community business and social capital in the development of community-based tourism. J. Soc. Res. 2024, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Ogbari, M.E.; Folorunso, F.; Simon-Ilogho, B.; Adebayo, O.; Olanrewaju, K.; Efegbudu, J.; Omoregbe, M. Social Empowerment and Its Effect on Poverty Alleviation for Sustainable Development among Women Entrepreneurs in the Nigerian Agricultural Sector. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Jong, A.; Ngoasong, M.Z.; Kimbu, A.N. The Gendered Dynamics of Financing Tourism Entrepreneurship. In Gender, Tourism Entrepreneurship and Social Policy; Routledge: London, UK, 2025; pp. 97–111. [Google Scholar]

- Subramaniam, S.; Mathai, S.M. Psycho-social and health related adaptive responses to climate change. Asia Pac. Bus. Rev. 2010, 6, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razmeh, S. From screen to society: Second language learners’ cultural adaptation and identity reconstruction in virtual knowledge communities. J. Multicult. Educ. 2024, 18, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramaniam, K. Student teachers’ conceptions of teaching biology. J. Biol. Educ. 2014, 48, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hota, P.K.; Subramanian, B.; Narayanamurthy, G. Mapping the intellectual structure of social entrepreneurship research: A citation/co-citation analysis. J. Bus. Ethics 2020, 166, 89–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mpuangnan, K.N.; Ntombela, S. Community voices in curriculum development. Curric. Perspect. 2024, 44, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafar, M.; Bashir, M.F.; Bukhari, A.A.A. Women’s empowerment and tourism: Emerging determinants of poverty in low and middle-income countries. Int. Soc. Sci. J. 2024, 74, 1069–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrasco-Santos, M.J.; Seyfi, S.; Hosseini, S.; Hall, C.M.; Mohajer, B.; Almeida-García, F.; Macías, R.C. Breaking boundaries: Exploring gendered challenges and advancing equality for Iranian women careers in tourism. Tour. Manag. 2024, 103, 104913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, D.; Meiklejohn, A.; Spencer, N.; Lawrence, S. Precariat women’s experiences to undertake an entrepreneurial training program. J. Bus. Res. 2024, 178, 114671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, A. Empowering Rural Women in Harnessing Entrepreneurship for Sustainable Development Goals in the Digital Era. In Empowering Women Through Rural Sustainable Development and Entrepreneurship; IGI Global Scientific Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2025; pp. 179–200. [Google Scholar]

- Ndaita, J.S.; Chebet, E. Redefining Ripple Effect on Education of Women as Agents of Social Transformation and Peacemakers in Africa: A case of Elgeyo Marakwet County, Kenya. J. Afr. Interdiscip. Stud. 2024, 8, 75–86. [Google Scholar]

- Boley, B.B.; McGehee, N.G. Measuring empowerment: Developing and validating the resident empowerment through tourism scale (RETS). Tour. Manag. 2014, 45, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatta, D.D.; Sarfraz, M.; Ivascu, L.; Pislaru, M. The Nexus of Corporate Affinity for Technology and Firm Sustainable Performance in the Era of Digitalization: A Mediated Model. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLeod, L.; O’Reilly, M. Feminist Interventions in Critical Peace and Conflict Studies; Routledge: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- McMillan, M.S.; Rodrik, D. Globalization, Structural Change and Productivity Growth; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Vicent, L.; Senyonga, L.; Namagembe, S.; Nantumbwe, S. Analysis of the impact of women’s empowerment and social network connections on the adoption and sustained use of clean cooking fuels and technologies in Uganda. Energy Policy 2025, 198, 114435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyfi, S.; Kimbu, A.N.; Tavangar, M.; Vo-Thanh, T.; Zaman, M. Surviving crisis: Building tourism entrepreneurial resilience as a woman in a sanctions-ravaged destination. Tour. Manag. 2025, 106, 105025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahin, E. From Contention to Prefiguration: Women’s Autonomous Mobilization and Rojava Revolution; State University of New York at Binghamton: Binghamton, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Rendueles, C. The Commons: A Force in the Socio-Ecological Transition to Postcapitalism; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Kreienkamp, J. Responding to the Global Crackdown on Civil Society; Global Governance Institute: Brussels, Belgium, 2017; Available online: https://www.ucl.ac.uk/global-governance/sites/global-governance/files/policy-brief-civil-society.pdf (accessed on 13 December 2024.).

- MacGregor, S. ‘Gender and climate change’: From impacts to discourses. J. Indian Ocean Reg. 2010, 6, 223–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerő, M.; Fejős, A.; Kerényi, S.; Szikra, D. From Exclusion to Co-Optation: Political Opportunity Structures and Civil Society Responses in De-Democratising Hungary. Polit. Gov. 2023, 11, 16–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, S.; Füreder, P.; Rogenhofer, E. Earth observation for humanitarian operations. In Yearbook on Space Policy 2016: Space for Sustainable Development; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 217–229. [Google Scholar]

- Riley, D.; Fernández, J.J. Beyond strong and weak: Rethinking postdictatorship civil societies. Am. J. Sociol. 2014, 120, 432–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Husseini, S.; Elbeltagi, I. Transformational leadership and innovation: A comparison study between Iraq’s public and private higher education. Stud. High. Educ. 2016, 41, 159–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamid, M.A.; Basid, A.; Aulia, I.N. The reconstruction of Arab women role in media: A critical discourse analysis. Soc. Netw. Anal. Min. 2021, 11, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, M.I. Attribution Theory Revisited: Probing the Link Among Locus of Causality Theory, Destination Social Responsibility, Tourism Experience Types, and Tourist Behavior. J. Travel Res. 2023, 62, 1309–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Sun, J. Embodiment of feminine subjectivity by women of a tourism destination. J. Sustain. Tour. 2023, 31, 1447–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhabra, D. Transformational model of well-being for serious travellers. Int. J. Spa Wellness 2022, 5, 129–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Pan, L.; Hu, Y. Cultural involvement and attitudes toward tourism: Examining serial mediation effects of residents’ spiritual wellbeing and place attachment. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2021, 20, 100601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshaer, I.; Moustafa, M.; Sobaih, A.E.; Aliedan, M.; Azazz, A.M.S. The impact of women’s empowerment on sustainable tourism development: Mediating role of tourism involvement. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2021, 38, 100815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, C.; Pichler, F. More participation, happier society? A comparative study of civil society and the quality of life. Soc. Indic. Res. 2009, 93, 255–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cioca, L.-I.; Ivascu, L.; Turi, A.; Artene, A.; Găman, G.A. Sustainable Development Model for the Automotive Industry. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, M.; Khalid, R.; Loureirco, S.M.C.; Han, H. Luxury brand at the cusp of lipstick effects: Turning brand selfies into luxury brand curruncy to thrive via richcession. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2024, 79, 103850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.; Sarstedt, M. Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM); Sage Publications Ltd.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kock, N. Common method bias in PLS-SEM: A full collinearity assessment approach. Int. J. e-Collab. 2015, 11, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Howard, M.C.; Nitzl, C. Assessing measurement model quality in PLS-SEM using confirmatory composite analysis. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 109, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarstedt, M.; Hair, J.F., Jr.; Nitzl, C.; Ringle, C.M.; Howard, M.C. Beyond a tandem analysis of SEM and PROCESS: Use of PLS-SEM for mediation analyses! Int. J. Mark. Res. 2020, 62, 288–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Gabriel, M.; Patel, V. AMOS covariance-based structural equation modeling (CB-SEM): Guidelines on its application as a marketing research tool. Braz. J. Mark. 2014, 13, 44. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, M. Structural equation modeling: Threshold criteria for assessing model fit. In Methodological Issues in Management Research: Advances, Challenges, and the Way Ahead; Emerald Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2019; pp. 269–276. [Google Scholar]

- Bejan, V.; Pîslaru, M.; Scripcariu, V. Diagnosis of Peritoneal Carcinomatosis of Colorectal Origin Based on an Innovative Fuzzy Logic Approach. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hibbs, L. ‘I could do that!’—The role of a women’s non-governmental organisation in increasing women’s psychological empowerment and civic participation in Wales. Women’s Stud. Int. Forum 2022, 90, 102557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linfang, Z.; Khalid, R.; Raza, M.; Chanrawang, N.; Parveen, R. The Impact of Psychological Factors on Women Entrepreneurial Inclination: Mediating Role of Self-Leadership. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 796272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, R.; Raza, M.; Piwowar-Sulej, K.; Ghaderi, Z. There is no limit to what we as women can accomplish: Promoting women’s entrepreneurial empowerment and disaster management capabilities. J. Hosp. Tour. Insights 2025, 8, 393–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jinia, N.J.; Asaduzzaman, M.; Vartola, J. Empowerment of civil society. In Reduced Inequalities; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 167–177. [Google Scholar]

- Ivascu, L.; Sarfraz, M.; Mohsin, M.; Naseem, S.; Ozturk, I. The Causes of Occupational Accidents and Injuries in Romanian Firms: An Application of the Johansen Cointegration and Granger Causality Test. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei-Moghaddam, K.; Badzaban, F.; Fatemi, M. Entrepreneurial resilience of small and medium-sized businesses among rural women in Iran. J. Agric. Educ. Ext. 2023, 29, 75–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitole, F.A.; Genda, E.L. Empowering her drive: Unveiling the resilience and triumphs of women entrepreneurs in rural landscapes. Women’s Stud. Int. Forum 2024, 104, 102912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).