Abstract

Environmental stewardship is crucial for fostering sustainable development, particularly in vulnerable small-island developing states like Tuvalu. Government policies and frameworks play a vital role in shaping the education system, but inconsistencies in policy alignment often hamper efforts to embed Environmental Stewardship Education (ESE) into the national curriculum. We aimed to answer four questions: 1. What formal policies shape Environmental Stewardship Education (ESE) in Tuvalu? 2. Are national educational and environmental policies mutually consistent? 3. Are these national policies consistent with regional and global policies? 4. What challenges hinder the implementation of ESE in Tuvalu? These questions were addressed using a study of regional, international, and Tuvaluan online-available documentary assessments of national policies and frameworks in conjunction with those obtained from the Education Department. Our findings revealed that a combination of Tuvalu’s environmental and educational policies was instrumental in shaping ESE. Nationally, educational and environmental policies are internally inconsistent, as well as being inconsistent externally with regional and international policies. Recommendations for improving policy alignment and the sustainable integration of ESE into the curriculum are provided. The second part (Part 2) of our review covers the development and delivery of effective curricula for ESE.

1. Introduction

Tuvalu is the world’s fourth-smallest country, with a population of roughly 11,000 people, a land area of only 25.9 km2, and a 900,000 km2 exclusive economic zone. It consists of five coralline atolls (Nanumea, Nui, Nukufetau, Funafuti, and Nukulaelae), three table reef islands (Nanumaga, Niutao, and Niulakita), and one composite (coralline atoll/table reef) island (Vaitupu) (Figure 1). Islands and atolls rarely reach higher than 3 m above sea level, an attestation to Tuvalu’s vulnerability to sea-level rise, erosion, saltwater intrusion, inundation, and storm surges associated with cyclones [1]. The 2021 Commonwealth Universal Vulnerability Index (UVI) shows that Tuvalu had an index of 0.97 for UVI_1 in 2018, which signifies its vulnerability to external and natural shocks, climate change, and socio-political or societal fragility, partially matched by its structural and policy resilience. According to UVI_2, Tuvalu was among the thirty most vulnerable countries in 2018 [2]. Based on the 2021 World Risk Index, Tuvalu’s atoll neighbour, Kiribati, is among the twenty countries both at risk of experiencing natural disasters and possessing the lowest adaptation capacity [3]. Tuvalu would have been placed at the same risk level had there not been an excessive number of missing vulnerability values. In June 2024, Tuvalu had an estimated population of 11, 478 [4], of whom an estimated 50.4% resided in Funafuti, the capital of Tuvalu [5].

Figure 1.

Tuvalu’s atoll environment—East Funafuti. Source: [6].

Tuvalu’s vulnerability to environmental changes, such as rising sea levels and extreme weather events, necessitates the incorporation of environmental stewardship into its education system. However, discrepancies in regard to policy alignment have hampered efforts to incorporate Environmental Stewardship Education (ESE) into the national curriculum. This paper focuses on the policy landscape that shapes ESE in Tuvalu and evaluates the consistency of national educational and environmental policies as well as their alignment with regional and international frameworks. Part two of this research will focus on existing curricula and where policy findings can be integrated.

Research Questions

This study aims to address the following research questions:

- RQ1: What formal policies shape Environmental Stewardship Education (ESE) in Tuvalu?

- RQ2: Are national educational and environmental policies mutually consistent?

- RQ3: Are these national policies consistent with regional and global policies?

- RQ4: What challenges hinder the implementation of Environmental Stewardship Education in Tuvalu?

These questions are systematically addressed in Section 5.1, Section 5.2, Section 5.3, and Section 5.4, respectively.

2. Theoretical and Policy Insights

2.1. Environmental Stewardship Education: Theoretical Insights

Environmental stewardship involves preservation, restoration, and using sustainable practices to improve ecosystem resilience and human well-being [7]. This concept aligns with the first research question: What are the formal policies shaping ESE in Tuvalu? Bennett et al. [8] defined local environmental stewardship as individuals, groups, or networks of actors with different motivations and capacities protecting, caring for, or responsibly using the environment to achieve environmental and/or social outcomes in various social–ecological contexts. Bennett et al.’s definition was adopted as this research focused on actors, capacity, and motivation, the three most critical characteristics of environmental stewardship. Individuals, local communities, civil society organisations (CSOs), non-governmental organisations (NGOs), and governments are involved in this activity. Local environmental stewardship may be promoted through horizontal policy integration. Our study draws on an earlier coding scheme (please refer to Section 2.2) to identify how these theoretical insights are reflected in Tuvalu’s formal policies. For instance, terms like “sustainability” and “climate change” are frequently referenced in national policies, indicating a focus on these aspects in the educational framework.

Environmental stewardship (ES) and education are interdependent [9,10,11], as education fosters environmental stewardship by raising awareness, providing information, and promoting responsible behaviour. Environmental stewardship is closely related to environmental education (EE), education for sustainability (EfS), education for sustainable development (ESD), place-based education (PBE), and community-based education (CBE) [12]. EE promotes environmental stewardship through educating individuals regarding the significance of the environment and the consequences of human actions [13]. ESD, EfS, and ES aim to promote sustainable practices and preserve the environment. PBE involves learning about a place’s local environment, culture, and history, while CBE involves learning about and engaging with the local community [14,15]. Both can promote environmental stewardship through nurturing a sense of community and environmental connection and responsibility. In Tuvalu, this occurs through the informal inter-generational transmission of traditional ecological knowledge, skills, and values that generally occurs through oral and practical informal means in village settings, i.e., peer-to-peer learning [16]. For effective ES, this needs to be incorporated into formal education curricula [16,17].

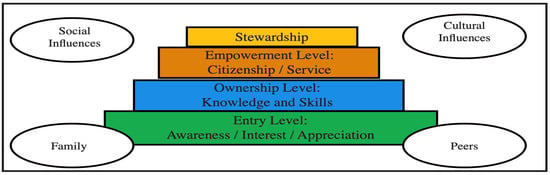

In our analysis, we found that ESE was rarely discussed explicitly in the literature, but the term ‘Stewardship Education’ was commonly used, characterised by a process of creating an internalised stewardship ethic and developing abilities needed to make informed decisions and engage in environmental stewardship behaviours [18]. Association of Fish & Wildlife Agencies-Conservation Education Strategy Committee [11] proposes that to foster environmental stewardship behaviour, education programmes should consider a student’s progression from the entry-level (environmental awareness and environmental knowledge) to the ownership level (an in-depth understanding of and identification with an issue) and empowerment level (the will to act and personal responsibility), as depicted in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Progression toward environmentally responsible behaviour. Source: [11].

This research draws on Thorne’s [19] ESE definition, which considers the inclusion of care pedagogy in environmental and sustainability education programmes. Thorne demonstrates that ESE is a feasible educational strategy and explores where it is effective and how Tuvalu may benefit from it. It has also been posited that ESE is a crucial component of education in the Anthropocene [20], as it is designed to develop the emotional and cognitive skill sets necessary to deal with severe environmental change and provide the foundation for an egalitarian and sustainable culture [12]. Furthermore, ESE is included in all formally recognised environmental education programmes, including EE, ESD, EfS, PBE, CBE, and climate change education (CCE) [12,21] (p. 22; p. 6). ESE is a tool with which to change students’ attitudes and behaviours towards the natural environment, and formal education is the best medium for developing environmentally conscious citizens [22]. Formal education is essential for developing a literate and educated populace for the modern economy [23], allowing for the development of skills, attitudes, and values to foster decent living and improved environmental behaviours [24]. Recent studies have shown that more excellent formal education significantly boosts individuals’ public and private environmental behaviour [25,26]. Higher levels of formal education improve individuals’ environmental knowledge and pollution awareness, influencing their environmental behaviour. However, there is a debate on where and how to situate formal ESE appropriately across formal educational timelines.

2.2. Policy Analysis Methodology

In our study, we utilised a coding scheme adapted from Thorne (2017) [19] and Aikens et al. (2016) [27], focusing on keywords such as “sustainability”, “biodiversity”, “climate change”, and “disaster risk reduction”. Additionally, it focuses on phrases like “environmental stewardship” and “ethic of care”. The document analysis method utilised in this study ties into the second research question: are national educational and environmental policies mutually consistent? All relevant policy documents were thoroughly read, focusing on the identified keywords and phrases. These keywords and phrases were extracted and synthesised into overarching themes, allowing for a structured and systematic analysis of how environmental stewardship is incorporated into Tuvalu’s policies.

3. National, Regional, and International Policies and Frameworks

3.1. National Policies

Tuvalu has developed several national policies aimed at integrating environmental stewardship into formal education. These include the Tuvalu National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan (TNBSAP) 2012–2016 [28], the Integrated Environment and Natural Resources Policy (IENRP) 2020–2022 [29], and the Tuvalu National Environmental Management Strategy (NEMS) 2022–2026 [30]. However, while these documents emphasise sustainability and climate resilience, they only implicitly reference environmental stewardship, and their connections to formal education are indirect.

Table 1 specifically summarises the overarching goals of policies most explicitly relevant to environmental stewardship and its integration into formal education. While the TNBSAP is included in both the paragraph and the table due to its direct focus on biodiversity and its linkages to education, the IENRP and NEMS were excluded from the table because their primary focuses lie in broader environmental management and resource use rather than explicitly targeting formal education or curriculum integration.

Table 1.

Goals of Tuvalu’s relevant policies on environmental stewardship.

3.2. International and Regional Frameworks

International frameworks such as the Paris Agreement [31], the Kunming–Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (KMGBF) 2022–2030 [32], and the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction (SFDRR) 2015–2030 [33] emphasise the need for education to address climate change, disaster risks, and biodiversity conservation. The Paris Agreement is a global pact with the aim of limiting global warming to well below 2 degrees Celsius, preferably 1.5 degrees Celsius; in Article 82, it calls on all parties to ensure that education contributes to the development of climate change resilience. The Kunming–Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (KMGBF) 2022–2030 and its predecessor, the Strategic Plan for Biodiversity 2011–2020 [34], are international frameworks designed to guide governments, both subnational and local, in taking action to halt and reverse biodiversity loss and enhance the benefits of biodiversity for people. These frameworks encourage incorporating biodiversity into education programmes, promoting biodiversity conservation and sustainable use curricula in educational institutions, and fostering knowledge, attitudes, values, behaviours, and lifestyles consistent with living in harmony with nature [30]. The SFDRR promotes disaster risk knowledge in formal and non-formal education, primary and secondary school resilience programmes, teachers’ curricula material, and the idea that children and youth are agents of change [33].

Regional frameworks like the Pacific Islands Framework for Nature Conservation and Protected Areas (PIFNCPA) 2021–2025 [35] and the Framework for Resilient Development in the Pacific (FRDP) 2017–2030 [36] also stress the importance of aligning national policies with regional and global standards. The PIFNCPA guides Pacific partners’ conservation efforts, emphasising the need for coordinated Pacific-wide efforts to handle environmental issues and emerging threats to Pacific ecosystems, cultures, and economies [35]. The objectives of the PIFNCPA are to protect Pacific biodiversity and the natural environment forever, lead conservation and preservation activities regarding natural resources for present and future generations, and conserve nature and use resources sustainably. The FRDP promotes two types of integration: integrating climate change and disaster mitigation actions to reduce redundancy and maximise resource use and mainstreaming climate change and disaster risk action into development planning, policy, funding, programming, and execution. The FRDP [36] is a “mainstreaming and integration” first for the Pacific and represents the region’s global leadership in the recognition and advocacy of integrated resilient development. It should also be noted that ministers at the Inaugural Pacific Disaster Risk Reduction Ministers Meeting (Nadi, Fiji, September 2022) and the Asia–Pacific Ministerial Conference for Disaster Risk Reduction (APMCDRR, Brisbane, Australia, September 2022) recognised that disaster risk reduction (DRR) underpins sustainable development and serves as the nexus for the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, the Paris Agreement, the Agenda for Humanity, and the New Urban Agenda. This integrated approach is very much reflected in the ethics of environmental stewardship. The FRDP encourages formal and non-formal education systems to increase knowledge related to causes, impacts, and responses to climate change, hazards, and disasters and capacity-building for adaptation and risk management measures. The PIFNCPA 2021–2025 and the FRDP 2017–2030 are relevant regional guidelines that could connect to the Tuvaluan policy context above.

However, Tuvalu’s national policies often lack the depth required to align fully with these global and regional commitments. Figure 3 shows a timeline of cross-cutting international strategies, conventions, and frameworks relevant to environmental stewardship in the Pacific.

Figure 3.

Timeline of cross-cutting international strategies, conventions, and frameworks relevant to environmental stewardship in the Pacific. Source: Authors’ creation.

Table 2 below provides a comparison of Tuvalu’s national policies with regional and international frameworks.

Table 2.

Broad goals of national, regional, and international policies on environmental stewardship.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Collection of Key Documents

We sought to collect relevant national policy documents from government agencies addressing environmental stewardship and related themes. A combination of methods was employed, including an Internet-based search of documents on national ministries of environment, climate change, and education websites as well as a Google search using keywords such as the ‘Pacific Strategy for Biodiversity Conservation’, ‘Climate change and Disaster Risk Reduction’, ‘a Global Framework for Biodiversity Conservation’, ‘Paris Agreement’, ‘Disaster Risk Reduction Global Framework’ and ‘Agenda 2030 for Sustainable Development’. Materials not available online were requested from relevant national agencies through email.

4.2. National Policies and Frameworks

The documents were filtered and analysed to assess the degree of alignment between educational and environmental policies. Government policy records available online were identified in the following relevant government departments: the Education Department (EdDep), the Department of Environment (DoE), and the Department of Climate Change (DCC). EdDep documents were filtered for those available from 2007 to 2019, resulting in nine documents (see Table 3), while DoE and DCC documents were the most recent ones used for their day-to-day management decisions (see Table 1, Table 2 and Table 4).

4.3. Regional and International Policies

We compared national policies with regional and international frameworks to evaluate consistency. Tuvalu is part of the Pacific region, and regional policies influence national policies. Regional policy records available online were identified in the South Pacific Regional Environmental Programme (SPREP) and Pacific Community (SPC). The documents analysed (see Table 2 and Table 5) included the PIFNCPA 2021–2025 [35] and the FRDP 2017–2030 [36].

Additionally, this study examined the consistency of national policies with international ones. Relevant global policies and frameworks that promote environmental stewardship education, such as the Kunming–Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (KMGBF) and its predecessor, the Paris Agreement (PA), the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction (SFDRR), and the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development also known as the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), were identified through Internet searches (see Table 1 and Table 6).

4.4. Document Content and Discourse Analysis of the Policy Documents

This analysis was conducted to identify the presence of environmental stewardship (ES) concepts in the policies. An analysis of national government policy documents on education that frame ES and its related themes was conducted to understand Tuvalu’s education strategies and curricula regarding ES. The approach used was a document content and discourse analysis based on Cardno’s [39] and Perryman’s [40] typologies. In Document content analysis, the aim is to extract meaning from data by revealing underlying themes, patterns, and trends that reveal authors’ intentions, worldviews, and practises [39]. Document discourse analysis focuses on the social and cultural contexts in which the studied documents were produced and how the language used reflects and shapes these contexts [40].

We conducted a document content and discourse analysis of government, regional, and international documentation. We read the documents to examine the language used and whether ES was emphasised in government documents. The intent of the government documents and the expression of ES in educational and environmental policies were analysed to uncover relationship linkages. We were particularly interested in how the educational policies mirrored the language of environmental policies that call for the inclusion of environmental stewardship and related themes. The inquiry was broadened to see if national policies were consistent with regional and international ones.

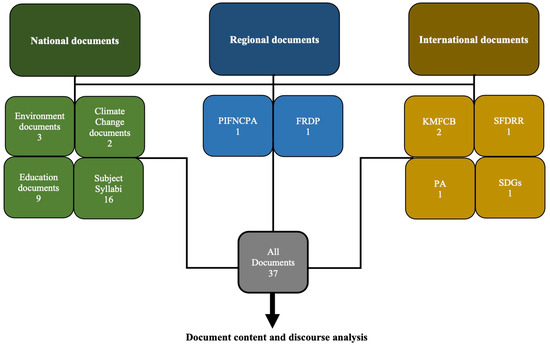

In this research, we utilised keywords and phrases employed by Thorne [19] (p. 100) and Aikens et al. [27] (p. 338) to identify the actual word ‘environmental stewardship’, ‘phrases related to environmental stewardship’, and ‘phrases that depict an inference to environmental stewardship’ in policy documents. These search terms and phrases were compared to the environmental and education documents, and repeated words were highlighted and tallied. To identify rhetoric and determine the meaning of the words and phrases in the policy documents, tone and mood were analysed according to the procedures explained by Thorne [19] and Aikens et al. [27]. An analysis of the content and discourse of policy documents was carried out. All documents examined in this research included environmental and educational policies formulated by the Tuvaluan Government to provide direction for environmental and academic endeavours in the country as well as key regional and international frameworks. These regional and international documents, such as the Pacific Islands Framework for Nature Conservation and Protected Areas (PIFNCPA), the Framework for Resilient Development in the Pacific (FRDP), the Paris Agreement, the Kunming–Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (KMGBF), and the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction, were included to understand the alignment of Tuvalu’s policies with broader global and regional priorities for ESE. The statistical association approach was employed to evaluate the frequency of the words and their contextual function to gain insight into the context density surrounding the principles and objectives of ES and its associated concepts. All documents were analysed using quantitative and qualitative content analysis. A summary of all documents collected for analysis is presented in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

A summary of all documents collected and analysed. Source: Authors’ creation.

5. Results

5.1. Formal National Policies Shaping ESE in Tuvalu

The analysis of the 30 national documents collected, especially the 9 educational policy documents from 2007 to 2019, revealed that environmental stewardship (ES) was not explicitly emphasised in government documents between 2007 and 2019 (see Table 3 below). This result suggests a gap in the explicit promotion of ES within these documents. However, sustainability, environment, biodiversity, climate change, and disaster risk reduction were referenced in educational documents, with sustainability and the environment being the most referenced concepts.

Table 3.

References to ES-related concepts in government education documents.

Table 3.

References to ES-related concepts in government education documents.

| Year | Document—Author | ES | Sus | Env | BD | CC | DRR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2007 | Early-Childhood Care and Education Policy 2007—Government of Tuvalu | 0 | 0 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2009 | National Education Policy—Government of Tuvalu | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2011 | Tuvalu Education Sector Plan II (TESP II) 2011–2015—Government of Tuvalu | 0 | 2 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2013 | Tuvalu National Curriculum Policy Framework (TNCPF 2013): Quality Education for sustainable living for all—Government of Tuvalu | 0 | 31 | 28 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2013 | Tuvalu MDG Acceleration Framework: Improving Quality Education—Government of Tuvalu | 0 | 43 | 8 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| 2015 | Education for All 2015 National Review Report: Tuvalu—Government of Tuvalu | 0 | 21 | 20 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| 2016 | Tuvalu Education Sector Plan III (TESP III) 2016–2020—Government of Tuvalu | 0 | 25 | 7 | 0 | 17 | 8 |

| 2017 | Tuvalu Education Sector Situational Analysis—Government of Tuvalu | 0 | 9 | 5 | 0 | 2 | 3 |

| 2019 | Tuvalu National Curriculum Policy Framework (TNCPF 2019): Quality Education for sustainable living for all—Government of Tuvalu | 0 | 29 | 26 | 0 | 5 | 0 |

Source: PhD thesis of Tinilau [41]. ES—environmental stewardship; Sus—sustainability; Env—environment; BD—biodiversity; CC—climate change; DRR—disaster risk reduction.

The primary educational policies shaping ESE in Tuvalu include the Tuvalu Education Strategic Plan III (TESP III) 2016–2020 [42] and the Tuvalu National Curriculum Policy Framework (TNCPF) 2019 [43]. These educational policies aim to incorporate sustainability into the formal education system but only refer to environmental stewardship in broad terms, without a focused agenda for ESE.

Other national frameworks shaping ESE in Tuvalu are environmental frameworks such as the Tuvalu National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan (TNBSAP) 2012–2016, the Integrated Environment and Natural Resources Policy (IENRP) 2020–2022, and the Tuvalu National Environmental Management Strategy (NEMS) 2022–2026. The TNBSAP outlines strategies for managing and protecting biodiversity in Tuvalu, focusing on ecosystem health and sustainability. This plan highlights the need to incorporate biodiversity and environmental awareness into formal education as a cross-cutting theme. However, analysis reveals that the explicit promotion of environmental stewardship is limited, with most references to biodiversity preservation and climate resilience not being directly tied to educational objectives. The IENRP aims to address critical environmental challenges by promoting the sustainable use of natural resources. Although the IENRP includes provisions for environmental stewardship, they are broadly outlined and lack detailed strategies or specific guidelines for the integration of ES into the formal education system. On the other hand, the NEMS emphasises the importance of environmental sustainability and outlines strategies for waste management, pollution control, and ecosystem preservation. While it advocates for public environmental education, this policy lacks specific guidance on how ESE should be implemented within formal school curricula.

Our analysis of these formal policies indicates that while numerous national frameworks indirectly support environmental stewardship, they do not explicitly prioritise ESE as a core component of formal education. Environmental stewardship is often embedded within broader themes of sustainability and climate resilience rather than being a standalone objective in the educational policies shaping the formal education system in Tuvalu.

5.2. Inconsistencies Between Educational and Environmental Policies in Implementing ESE

Our analysis reveals inconsistencies between national educational and environmental policies in terms of how they approach ESE. Educational policies such as TESP III 2016–2020 and TNCPF 2019 emphasise sustainability as a guiding principle in the curriculum but provide little guidance on how ESE should be integrated into learning objectives. The TNCPF envisions an outcome-based curriculum focusing on skill development for managing environmental change. However, it lacks specific provisions for biodiversity conservation, climate change education, or disaster risk reduction as part of the core curriculum at different educational stages.

On the other hand, environmental policies such as the TNBSAP, IENRP, and NEMS prioritise environmental preservation and awareness but do not provide adequate frameworks for formal school integration. For instance, while the TNBSAP calls for integrating biodiversity into the curriculum, the educational policies do not reflect these intentions with corresponding curriculum changes.

Evidently, horizontal integration between the education and environmental sectors is weak. Limited collaboration exists between government departments responsible for education and those managing environmental initiatives. This has led to gaps in aligning environmental policies with actual educational practices, where ESE remains underdeveloped in formal schooling despite being a key focus of environmental policies.

Hence, the national educational and environmental policies are not mutually consistent. The environmental policies advocate for environmental awareness and stewardship, but the education system does not adequately reflect these in its curricula. There is a clear need for greater horizontal policy integration between the education and environmental sectors to ensure that ESE is consistently addressed.

5.3. Alignment of National and Global Environmental Stewardship Frameworks

Several gaps and inconsistencies emerge when comparing Tuvalu’s national policies with regional and international frameworks.

Consistency with Regional Policies: Regional frameworks such as the Pacific Islands Framework for Nature Conservation and Protected Areas (PIFNCPA) and the Framework for Resilient Development in the Pacific (FRDP) stress the importance of integrating environmental stewardship into educational systems to foster climate resilience and disaster preparedness. These frameworks encourage formal education systems to build a capacity for addressing climate change, DRR, and biodiversity conservation. Tuvalu’s environmental policies, such as the TNBSAP and NEMS, are broadly consistent with these regional frameworks, as they prioritise biodiversity protection and disaster risk management. However, the degree of translation of these objectives into the formal education system remains weak, creating a misalignment between the goals of regional frameworks and national educational implementation.

Consistency with Global Policies: International frameworks such as the Paris Agreement [31] and the Kunming–Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (KMGBF) 2022–2030 [32] call for integrating climate change education, biodiversity conservation, and sustainable development into school curricula. The Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction (SFDRR) 2015–2030 similarly emphasises disaster education as a critical strategy for building resilience. Although Tuvalu’s national policies express commitments to these global agendas, our analysis indicates that these commitments have not been fully translated into the education system. For example, global goals to integrate biodiversity education, climate change mitigation, and disaster preparedness into school curricula are echoed in environmental policy documents but not sufficiently reflected in educational strategies such as the TNCPF and TESP III.

Figure 3 above illustrates the timeline of international frameworks and regional strategies relevant to environmental stewardship in Tuvalu. This visualisation highlights the regional and global obligations that should inform Tuvalu’s policies. The above results suggest that while Tuvalu’s environmental policies align with regional and global frameworks, there is a significant gap in the educational policies’ alignment with these global commitments. The national curriculum does not fully reflect the key priorities set out in international agreements, which poses challenges for integrating ESE into the education system at a level that meets global standards.

5.4. Challenges Regarding Policy Implementation

While Tuvalu’s educational policies address sustainability, several factors have hindered the implementation of ESE. One major challenge is the lack of horizontal integration between government departments responsible for education and the environment. Policies on formal schooling and environmental stewardship lack coordinated implementation guidance across government departments and NGOs. This disconnect creates gaps between policy formation and practical application.

In addition, financial limitations, including reliance on Overseas Development Aid (ODA), constrain the government’s ability to fund long-term ESE programmes. Without adequate financial resources, policy execution and long-term planning for ESE implementation remain underdeveloped.

Another significant issue is the lack of vertical alignment between Tuvalu’s national policies and international frameworks, particularly regarding biodiversity conservation and climate change education. Table 4, Table 5 and Table 6 outline how national, regional, and international frameworks emphasise capacity-building through formal education systems and highlight where misalignments occur in Tuvalu’s policies.

Table 4.

Capacity-building references in national school-related environmental policies.

Table 4.

Capacity-building references in national school-related environmental policies.

| Policy/Framework | Aspect of Capacity-Building | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Tuvalu National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan (NBSAP) 2012–2016 | Formulate training modules as well as relevant curricula streams; the latter is for the incorporation of the teaching of biodiversity at all levels of schooling in the country, while the former is for national and community training workshops. Streamline biodiversity into primary and secondary curricula. | Cross-Cutting Issue 1: Capacity Building, Education, Training, Awareness, and Understanding, p. 24. Cross-Cutting Issue 1: Capacity Building, Education, Training, Awareness, and Understanding, Objectives 3, Actions 2, p. 27. [28] (p. 24, 27) |

| Integrated Environment and Natural Resources Policy 2020–2022 | Increase citizenry conservation through responsible waste management behaviour and participate in activities while complying with the applicable laws through awareness and education. Include waste management and pollution control subjects in the school curriculum and public awareness and radio programs. | Objective 3, Strategies bullet point 1, p. 11. Objective 3, Strategies bullet point 4, p. 11. [29] (p. 11) |

| Tuvalu National Environmental Management Strategy 2022–2026 | Train communities trained through formal and informal education in waste management and pollution control. Integrate traditional environmental knowledge and cultural practices into the Tuvalu education curriculum. | Section 3.8 Theme 8, NEMS Actions 8.1.1, p. 34 Section 3.8 Theme 8, NEMS Actions 8.2.3, p. 34 [30] (p. 34) |

Source: [28,29,30].

Table 5.

Capacity-building references in regional environmental frameworks for schools.

Table 5.

Capacity-building references in regional environmental frameworks for schools.

| Pacific Island Framework for Nature Conservation and Protected Areas (PIFNCPA) 2021–2025 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Strategic Objectives | Priority Actions | Best Practice | Page No. |

| 1. Empower our people to take action for nature conservation based on our understanding of nature’s importance for our cultures, economies, and communities | Change behaviour around nature conservation through identity, traditional knowledge, education, heritage, and cultural expressions. | Education-for-conservation and art-for-conservation initiatives must value and celebrate Pacific cultural expressions by cultivating partnerships with our elders, educators, artists, athletes, and community role models, as well as with our youth, women’s, faith-based, and cultural organisations. Existing traditional schools of learning should be supported by conservation partners as well as newer forms of education. | 18 |

| Framework for Resilient Development in the Pacific (FRDP) 2017–2030 | |||

| Goal | Stakeholders | Priority Actions | Page No. |

| 1. Strengthen integrated adaptation and risk reduction to enhance resilience to climate change and disasters | National and subnational governments and administrations | (q) Increase knowledge regarding the causes and local impacts of and responses to climate change, hazards, and disasters and build capacity for local adaptation and other risk management measures through formal and non-formal education systems, including for loss and damage. (r) Improve understanding and applications of successful strategies to increase resilience by documenting traditional, contemporary, and scientific knowledge and lessons learned to develop and utilise appropriate awareness, communication, education, and information materials for communities, media, schools, training providers, and universities. | 15 16 |

| Regional organisations and other development partners | (n) Work in close collaboration with member countries and other stakeholders to develop and deliver relevant capacity-building programmes, including emerging priorities such as loss and damage as a result of climate change. | 17 | |

| 2. Increase low-carbon development | Civil society and communities | (b) Lead and contribute to awareness campaigns and capacity-building in schools and communities to promote and facilitate energy and ecosystem conservation and the increased use of renewable energy through changes in attitudes and behaviour. | 20 |

| 3. Strengthen disaster preparedness, response, and recovery | National and subnational governments and administrations | (f) Support existing and additional capacity building and awareness raising for governments and communities (including churches and schools) to improve their disaster preparedness, response, and recovery capabilities, as they are often the first responders in the event of a disaster. | 23 |

Source: [35,36].

Table 6.

Capacity-building references in international environmental frameworks for schools.

Table 6.

Capacity-building references in international environmental frameworks for schools.

| Section/Subsection | Code | Objectives | Page No. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Strategic Plan for Biodiversity 2011–2020 | |||

| E. Enhancing implementation through participatory planning, knowledge management, and capacity building | ABT 19 | By 2020, ensure knowledge of and the science base and technologies relating to biodiversity, its value functioning, status and trends, and the consequences of its loss, are improved, widely shared and transferred, and applied. | n.p. |

| Kunming–Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (KMGBF) 2022–2030 | |||

| C. Making considerations for the implementation of the framework | 22 | Implementation of the framework requires transformative, innovative, and transdisciplinary education, both formal and informal, at all levels, including via science–policy interface studies and lifelong learning processes, recognising the diverse world views, values, and knowledge systems of indigenous peoples and local communities. | 7 |

| K. Communication, education, awareness, and uptake | 40 (f) | Integrating transformative education regarding biodiversity into formal, non-formal, and informal educational programmes; promoting curricula on biodiversity conservation and sustainable use in educational institutions; and promoting knowledge, attitudes, values, behaviours, and lifestyles that are consistent with living in harmony with nature. | 14 |

| Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction (SFDRR) 2015–2030 | |||

| II. Expected outcome and goal | 17 | Reduce disaster risks and prevent new ones from developing through the implementation of integrated and inclusive economic, structural, legal, social, health, cultural, educational, environmental, technological, political, and institutional measures that prevent and reduce hazard exposure and vulnerability to disasters and increase preparedness for response and recovery, thus strengthening resilience. | 12 |

| IV. Priority 1: Understanding disaster risk at national and local levels | 24 (l) 24 (m) | Promote the incorporation of disaster risk knowledge, including disaster prevention, mitigation, preparedness, response, recovery, and rehabilitation, in formal and non-formal education, in civic education at all levels, and in professional education and training. Promote national strategies for strengthening public education and awareness regarding disaster risk reduction, including disaster risk information and knowledge, through campaigns, social media, and community mobilisation, taking into account specific audiences and their needs. | 15 |

| V. Role of stakeholders | 36 (a) (ii) | Children and youth are agents of change and should be given the space and modalities required to contribute to disaster risk reduction, in accordance with legislation, national practice, and educational curricula. | 23 |

Source: [32,33,34].

6. Discussion

This study aimed to understand the status of environmental stewardship education in Tuvalu’s elementary and secondary schools. Document analyses found that national policies provide only sporadic support for formal education, emphasising environmental stewardship. Environmental stewardship and biodiversity are closely related but not explicitly specified as learning outcomes in the recently adopted outcome-based curriculum. Additionally, there is a mismatch between national policies and those at the regional and international levels.

In the global context, the Strategic Plan for Biodiversity 2021 and the newly endorsed Kunming–Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework urge the integration of biodiversity education into formal, non-formal, and informal educational programmes. The Sendai Framework calls for incorporating disaster risk knowledge in formal and non-formal education and empowering children and teenagers to contribute to disaster risk reduction through educational curricula. These recommendations have garnered support from scholars who advocate for integrating crucial concepts such as biodiversity [44], disaster risk reduction [45], and climate change [46] across all educational programmes.

On a regional scale, the Pacific Islands Framework for Nature Conservation and the Framework for Resilient Development in the Pacific promote conservation education and emerging forms of education to improve awareness of climate change, hazards, and disasters, as well as the capacity for adaptation and risk management. It also emphasises the development of capabilities for conserving terrestrial and marine ecosystems and using renewable energy in schools and communities to build resilience.

At the national level, Tuvalu has developed its TNBSAP, Te Vaka Fenua o Tuvalu, and Te Kete, which set out the country’s priorities until 2030. The TNBSAP encourages the formulation of biodiversity-relevant curricula streams and incorporates the teaching of biodiversity at all levels of schooling. Te Kaniva [47], Tuvalu’s previous climate change policy, calls for integrating climate change and disaster risk management into the school curriculum. At the same time, Te Kete Strategic Priority Area 1 does not mention any capacity building through formal primary and secondary education.

Key international and regional policies emphasise the importance of educating students at all levels about environmental stewardship. This prospect was promoted by Bennett et al. [48] and Potter [49] as ‘an education for the 21st century’, while Thorne and Whitehouse [20] argue that it is a critical component of education in and for the Anthropocene. Rogayan [10] remarked that “environmental stewardship must be developed in every student to globally make a difference towards the resolution of some, if not all, problems in the environment” (p. 10). These sentiments have been reflected in Tuvalu’s environmental policies, such as the biodiversity and climate change policies, but were not reflected in the education policies and frameworks.

7. Conclusions

This article has examined how formal policies shape ESE in Tuvalu and highlighted the challenges of aligning national, regional, and international policies. To embed ESE into Tuvalu’s education system, national policies must be revised to align with global commitments. Effective horizontal and vertical integration between government departments and sustained financial support is critical to ensuring the long-term success of ESE in the national curriculum.

To fully address the above policy misalignments, the following recommendations are proposed:

- ▪

- Biodiversity, Disaster Risk Reduction, and Climate Resilience in the Curriculum: National policies must prioritise the inclusion of biodiversity, disaster risk reduction, and climate resilience within the national curriculum to align with international frameworks.

- ▪

- Horizontal and Vertical Policy Integration: Government departments must work cohesively to align educational policies with national, regional, and international policies. This will ensure consistent implementation of ESE across the formal education system.

- ▪

- Long-Term Funding Mechanism: Securing long-term funding for ESE integration is essential. Tuvalu must strengthen its relationships with international donors and development partners to secure sustainable funding for educational development.

- ▪

- Capacity-Building Initiatives: Teachers and educational institutions should receive targeted training in ESE to ensure the effective delivery of content. Curriculum development and implementation are long processes that require sustained investment.

The government of Tuvalu can address these recommendations to promote ESE within its formal school system and align its educational policies with regional and international commitments. This will ensure that future generations of Tuvaluans are equipped with the knowledge, skills, and attitudes necessary to protect and conserve the environment for the benefit of all. Part 2 of this article will focus on the development and delivery of effective curricula for ESE.

Future research directions could focus on investigating the potential benefits of the suggested alterations, assessing their enduring effects on environmental awareness and actions, and identifying approaches to address any potential obstacles that may arise during their implementation. Such investigations are particularly critical for small-island developing states like Tuvalu.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.S.T., S.L.H. and A.P.K.; Methodology, S.S.T.; Formal analysis, S.S.T.; Investigation, S.S.T.; Data curation, S.S.T.; Writing—original draft preparation, S.S.T., S.L.H. and A.P.K.; Writing—review and editing, S.S.T., S.L.H., T.G.M., M.H. and A.P.K.; Visualization, S.S.T.; Supervision, A.P.K., S.L.H., T.G.M. and M.H.; Project administration, S.S.T. and A.P.K.; Funding acquisition, S.S.T. and S.L.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received external funding from the Commonwealth Scholarship Commission. The funding number to access this fund at the University of Lincoln is 0006192.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethics approval for this research was granted by the University of Lincoln, UK: LEAS reference 2021_6409.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the support provided by the Commonwealth Scholarship Commission, which was instrumental in facilitating this research. Additionally, we extend our gratitude to those who provided administrative and technical support throughout this project. Special thanks go to the Tuvalu Education Department, which contributed materials and resources for this project.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Government of Tuvalu. Te Kete: Tuvalu National Strategy for Sustainable Development 2021–2030; Ministry of Finance: Funafuti, Tuvalu, 2020.

- Kattumuri, R. The Commonwealth Universal Vulnerability Index: For a Global Consensus on the Definition and Measurement of Vulnerability. 2021. Available online: https://thecommonwealth.org/sites/default/files/inline/Universal%20Vulnerability%20Index%20Report.pdf (accessed on 11 January 2022).

- Aleksandrova, M.; Balasko, S.; Kaltenborn, M.; Malerba, D.; Mucke, P.; Neuschäfer, O.; Radtke, K.; Prütz, R.; Strupat, C.; Weller, D.; et al. World Risk Report: Social Protection. 2021. Available online: https://www.preventionweb.net/publication/world-risk-report-2021-focus-social-protection (accessed on 3 March 2022).

- World Population Review. World Population by Country 2024 (Live). Available online: https://worldpopulationreview.com/ (accessed on 1 June 2024).

- Central Statistics Division of the Government of Tuvalu. Tuvalu 2012: Population and Housing Census Volume 1 Analytical Report; Central Statistics Division: Funafuti, Tuvalu, 2013.

- Government of Tuvalu. Tuvalu NAPA II Project: Effective and Responsive Island-Level Governance to Secure and Diversify Climate Resilient Marine-Based Coastal Livelihoods and Enahnce Climate Hazard Response Capacity; Department of Environment: Funafuti, Tuvalu, 2013.

- Chapin, F.S., III; Carpenter, S.R.; Kofinas, G.P.; Folke, C.; Abel, N.; Clark, W.C.; Olsson, P.; Smith, D.M.S.; Walker, B.; Young, O.R.; et al. Ecosystem stewardship: Sustainability strategies for a rapidly changing planet. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2010, 25, 241–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bennett, N.J.; Whitty, T.S.; Finkbeiner, E.; Pittman, J.; Bassett, H.; Gelcich, S.; Allison, E.H. Environmental Stewardship: A Conceptual Review and Analytical Framework. Environ. Manag. 2018, 61, 597–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maher, M. Environmental Stewardship: “Where There’s a Will, Is There a Way?”. Aust. J. Environ. Educ. 1986, 2, 7–9. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/45239480 (accessed on 19 January 2022). [CrossRef]

- Rogayan, D.J.V. I Heart Nature: Perspectives of University Students on Environmental Stewardship. Int. J. Eng. Sci. Technol. 2019, 1, 10–16. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Danilo-Rogayan-Jr/publication/316698512_I_heart_nature_perspectives_of_university_students_on_environmental_stewardship/links/5c87cf89a6fdcc88c39d5e0a/I-heart-nature-perspectives-of-university-students-on-environmental-stewardship.pdf (accessed on 12 January 2021).

- Association of Fish & Wildlife Agencies-Conservation Education Strategy Committee. Stewardship Education: Best Practices Planning Guide; Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies: Washington, DC, USA, 2008. Available online: https://www.fishwildlife.org/application/files/5215/1373/1274/ConEd-Stewardship-Education-Best-Practices-Guide.pdf (accessed on 19 January 2022).

- Thorne, M.; Whitehouse, H. Environmental Stewardship Education in the Anthropocene (Part Two): A Learning for Environmental Stewardship Conceptual Framework. Soc. Educ. 2018, 36, 17–28. Available online: https://search.informit.org/doi/abs/10.3316/aeipt.219844 (accessed on 13 October 2022).

- McGuire, N.M. Environmental Education and Behavioral Change: An Identity-Based Environmental Education Model. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Educ. 2015, 10, 695–715. Available online: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1081842 (accessed on 21 November 2022).

- Gallay, E.; Marckini-Polk, L.; Schroeder, B.; Flanagan, C. Place-Based Stewardship Education: Nurturing Aspirations to Protect the Rural Commons. Peabody J. Educ. 2016, 91, 155–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, G.A.; Sobel, D. Place-and Community-Based Education in Schools; Spring, J., Ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2010; Available online: http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/ulinc/detail.action?docID=481055 (accessed on 19 January 2022).

- Pacific Community. Kiwa Initiative Capacity Needs Assessment for Implementing Nature-Based Solutions for Climate Change Adaptation; Pacific Community (SPC): Noumea, New Caledonia, 2023; Available online: https://library.sprep.org/content/kiwa-initiative-capacity-needs-assessment-implementing-nature-based-solutions-climate (accessed on 17 April 2024).

- Pierce, C.; Hemstock, S. Resilience in Formal School Education in Vanuatu: A Mismatch with National, Regional and International Policies. J. Educ. Sustain. Dev. 2021, 15, 206–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siemer, W.F. Best Practices for Curriculum, Teaching, and Evaluation Components of Aquatic Stewardship Education; ERIC: Alexandria, VA, USA, 2001. Available online: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED463935 (accessed on 15 November 2022).

- Thorne, M. Learning for Environmental Stewardship in the Anthropocene: A Study with Young Adolescents in the Wet Tropics. Ph.D. Thesis, College of Arts, Society and Education, James Cook University, Townsville, Australia, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorne, M.; Whitehouse, H. Environmental Stewardship Education in the Anthropocene: What Have We Learned from Recent Research in North Queensland Schools Adjacent to the Wet Tropics? Soc. Educ. 2017, 35, 17–27. Available online: https://search.informit.org/doi/epdf/10.3316/aeipt.216997 (accessed on 13 January 2025).

- Benavot, A. Education for Sustainable Development in Primary and Secondary Education; University at Albany-State University of New York: New York, NY, USA, 2014; Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/282342116_Education_for_Sustainable_Development_in_Primary_and_Secondary_Education (accessed on 14 February 2023).

- Borhan, M.T.; Ismail, Z. Promoting Environmental Stewardship through Project-Based Learning (PBL). Int. J. Humanit. Sci. 2011, 1, 180–186. Available online: www.ijhssnet.com (accessed on 31 January 2022).

- Kedrayate, A. Non-Formal Education: Is It Relevant or Obsolete. Int. J. Bus. Humanit. Technol. 2012, 2, 11–15. Available online: http://ijbhtnet.com/journals/Vol_2_No_4_June_2012/2.pdf (accessed on 7 January 2023).

- Fafioye, O.O.; Sangodapo, M.O.; Aluko, O.O. Is Formal Education and Environmental Education a False Dichotomy. J. Res. Environ. Sci. Toxicol. 2013, 2, 150–153. Available online: https://www.interesjournals.org/articles/is-formal-education-and-environmental-education-a-false-dichotomy.pdf (accessed on 11 March 2022).

- Hoffmann, R.; Muttarak, R. Greening through schooling: Understanding the link between education and pro-environmental behavior in the Philippines. Environ. Res. Lett. 2020, 15, 014009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Yang, S.; Li, S.; Zhang, Y. Does education level affect individuals’ environmentally conscious behavior? Evidence from Mainland China. Soc. Behav. Personal. 2020, 48, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aikens, K.; McKenzie, M.; Vaughter, P. Environmental and sustainability education policy research: A systematic review of methodological and thematic trends. Environ. Educ. Res. 2016, 22, 333–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Government of Tuvalu. Tuvalu National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan 2012–2016; Department of Environment: Funafuti, Tuvalu, 2012. Available online: https://tuvalu-data.sprep.org/dataset/national-biodiversity-strategy-and-action-plan-2012-2016 (accessed on 20 November 2021).

- Government of Tuvalu. Integrated Environment and Natural Resources Policy 2020–2022; Department of Environment: Funafuti, Tuvalu, 2019.

- Secretariat of the Pacific Regional Environment Programme. Tuvalu National Environment Management Strategy (NEMS) 2022–2026; Secretariat of the Pacific Regional Environment Programme: Apia, Samoa, 2022; Available online: https://www.sprep.org/news/tuvalu-launches-state-of-environment-report-and-national-environment-management-strategy (accessed on 25 November 2022).

- UNFCCC. Paris Agreement; UNFCCC: Bonn, Germany, 2015; Available online: https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/english_paris_agreement.pdf (accessed on 26 December 2022).

- Convention on Biological Diversity. Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework 2022–2030: Draft Decision Submitted by the President. In Proceedings of the Conference of the Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity Fifteenth Meeting (COP), Montreal, QC, Canada, 7–19 December 2022; Available online: https://www.cbd.int/conferences/2021-2022/cop-15/documents (accessed on 26 December 2022).

- UNDRR. Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015–2030. 2015. Available online: https://www.undrr.org/publication/sendai-framework-disaster-risk-reduction-2015-2030 (accessed on 19 December 2022).

- UNCBD. Strategic Plan for Biodiversity 2011–2020, Including Aichi Biodiversity Targets. 2011. Available online: https://www.cbd.int/sp/ (accessed on 19 December 2022).

- SPREP. Pacific Islands Framework for Nature Conservation and Protected Areas 2021–2025; Pacific Regional Environment Programme: Apia, Samoa, 2021; Available online: https://www.sprep.org/pirt/framework-for-nature-conservation-and-protected-areas-in-the-pacific-islands-region-2021-2025 (accessed on 24 December 2022).

- Pacific Community; Secretariat of the Pacific Regional Environment Programme; Pacific Islands Forum Secretariat; United Nations Development Programme; United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction; University of the South Pacific. Framework for Resilient Development in the Pacific: An Integrated Approach to Address Climate Change and Disaster Risk Management (FRDP) 2017–2030; Pacific Community: Suva, Fiji, 2016; Available online: https://www.resilientpacific.org/en/framework-resilient-development-pacific (accessed on 29 January 2022).

- Government of Tuvalu. Te Vaka Fenua o Tuvalu: National Climate Change Policy 2021–2030; Department of Climate Change: Funafuti, Tuvalu, 2021.

- UNDESA. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/publications/transforming-our-world-2030-agenda-sustainable-development-17981 (accessed on 19 December 2022).

- Cardno, C. Policy Document Analysis: A Practical Educational Leadership Tool and a Qualitative Research Method. Kuram Ve Uygulamada Eğitim Yönetimi 2018, 24, 623–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perryman, J. Discourse analysis. In Research Methods in Educational Leadership and Management, 3rd ed.; Ann, B., Marianne, C., Marlene, M., Eds.; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2012; pp. 309–322. [Google Scholar]

- Tinilau, S.S. An Examination of Formal, Non-Formal, and Informal Environmental Stewardship Education in Tuvalu. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Lincoln, Lincoln, UK, 2024. Available online: https://repository.lincoln.ac.uk/articles/thesis/An_Examination_of_Formal_Non-formal_and_Informal_Environmental_Stewardship_Education_in_Tuvalu/27018520/1 (accessed on 12 December 2024).

- Government of Tuvalu. Tuvalu Education Sector Plan III (TESP III) 2016–2020; Ministry of Education Youth and Sports: Funafuti, Tuvalu, 2016. Available online: https://meys.gov.tv/publication (accessed on 24 November 2021).

- Government of Tuvalu. Tuvalu National Curriculum Policy Framework; Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports: Funafuti, Tuvalu, 2019.

- Schneiderhan-Opel, J.; Bogner, F.X. FutureForest: Promoting Biodiversity Literacy by Implementing Citizen Science in the Classroom. Am. Biol. Teach. 2020, 82, 234–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amri, A.; Lassa, J.A.; Tebe, Y.; Hanifa, N.R.; Kumar, J.; Sagala, S. Pathways to Disaster Risk Reduction Education integration in schools: Insights from SPAB evaluation in Indonesia. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2022, 73, 102860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, R.R.; Mkumbachi, R.L. University students’ perceptions of climate change: The case study of the University of the South Pacific-Fiji Islands. Int. J. Clim. Change Strateg. Manag. 2021, 13, 416–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Government of Tuvalu. Te Kaniva: Tuvalu Climate Change Policy 2012; Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Trade, Tourism, Environment, and Labour: Funafuti, Tuvalu, 2012.

- Bennett, D.C.; Cornwell, G.H.; Al-Lail, H.J.; Schenck, C. An Education for the Twenty-First Century: Stewardship of the Global Commons. Lib. Educ. 2012, 98, 34–41. Available online: https://gustavus.edu/kendallcenter/teaching-programs-and-resources/documents/2013PDFAnEducationfortheTwenty-FirstCentury.pdf (accessed on 23 May 2023).

- Potter, G. Environmental Education for the 21st Century: Where Do We Go Now? J. Environ. Educ. 2009, 41, 22–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).