Abstract

Rural areas in Italy and Europe, while vital to agriculture and tourism, face transport limitations that restrict access to essential services, education, and jobs, deepening socio-economic exclusion. Transport policies often prioritize urban centers, leaving rural areas underfunded and with inadequate options, making daily mobility and economic development challenging. This study examines good practices from different EU countries, using a holistic case study approach, combining a literature review and analysis of implemented projects. A more nuanced understanding of successful rural mobility solutions throughout Europe is supported by this mixed technique. This hybrid analytical approach facilitates the identification of effective good practices that produce innovation in social engagement and inclusivity. This study’s conclusions highlight the potential of customized mobility solutions with inclusivity at their heart to effectively solve the particular difficulties encountered by rural communities. In contrast to urban areas, which have diverse and well-developed transportation networks, rural populations frequently face a lack of mobility options. This study demonstrates how tailored strategies, like delivering services right to people’s doorsteps, repurposing pre-existing infrastructure, or providing volunteer rides that link an isolated population to other communities, can close accessibility gaps that have long kept these populations apart.

1. Introduction

Rural areas hold immense cultural and natural resources and provide critical inputs for industries and economic activities, such as agriculture, agri-processing, and renewable energy development. These areas support global agricultural production, which makes a significant contribution to food security. Nonetheless, they continue to confront issues such as poverty, poor connectivity, limited access to basic services, and inadequate transportation infrastructure [1,2]. One of the most important of these is the problem of sustainable mobility. Low population density, seasonal demands, and reliance on private vehicles frequently result in transportation poverty in rural communities, which can cause social isolation and restrict access to necessary services [3,4].

In transportation policy-making, rural areas are often overlooked, despite their vital role in promoting environmental and economic sustainability. The majority of current public transportation initiatives and strategies are geared toward cities, underserving rural areas. Research such as the Interreg Europe—Rural Mobility Project and the SMARTA project emphasize the lack of policies specifically addressing rural mobility and the necessity of inclusive and integrated transportation frameworks to close these gaps [5,6,7,8].

The problems with rural mobility are largely caused by infrastructure, economic, and demographic factors. As a result of younger people moving to urban areas for work and educational opportunities [9], urbanization and aging populations have caused rural areas to become more sparsely populated, resulting in a demographic imbalance where a greater percentage of the population is older adults. Because public transportation is frequently inadequate or nonexistent in rural areas, a large number of people, including older adults, rely heavily on their cars, which causes accessibility problems when driving is no longer an option [10,11]. Rural households face financial strain and increased economic vulnerabilities due to forced car ownership brought on by a lack of practical transportation options [12,13].

A major component of transport poverty, accessibility poverty highlights the challenges that rural residents encounter in receiving necessary services in reasonable amounts of time and at reasonable costs because of limited infrastructure and lengthy travel times [14,15]. To further isolate rural populations, public transportation services have been drastically reduced in Norrbotten County, Sweden, where residents frequently travel more than 150 km to obtain basic services [16]. Increasing fuel costs makes things more difficult because older residents are finding it harder and harder to afford to travel, which limits their participation in everyday and social activities. Effective rural mobility solutions are further hampered by a lack of coordination amongst stakeholders and a lack of municipal support. Some of these issues have been addressed by community-driven projects that promote social cohesion and lessen isolation, such as setting up service hubs and using volunteers for technical assistance [17,18]. However, many rural areas remain vulnerable to accessibility and transport poverty due to the lack of comprehensive strategies to integrate public transportation with digital and shared mobility solutions.

Furthermore, traditional economic frameworks that place a higher priority on efficiency and financial costs, often at the expense of social, environmental, and health considerations, have historically influenced transportation decisions [19]. Recently, this economic-centric viewpoint has started to change as social and environmental considerations, especially in urban settings, have gained traction in transportation-related decision making [20,21]. Nevertheless, many European countries have not yet created comprehensive policies or set specific goals for sustainable rural mobility [22]. Rural areas’ naturally low population density makes it difficult to provide public transportation, making it unfeasible from an economic standpoint and encouraging reliance on private vehicles.

Understanding the diverse needs of various user groups, including both temporary and permanent residents, is essential to addressing social inclusivity in rural transportation. Nevertheless, there is still a dearth of research that considers all rural user groups holistically when assessing mobility solutions. The mobility requirements of temporary visitors and permanent residents are frequently separated in the literature currently in publication. One body of research examines how permanent residents travel, with an emphasis on the elements that help or hinder mobility for various groups, including working-age people, children, and retirees [23,24,25,26]. On the other hand, another body, frequently framed within the framework of tourism research, investigates the travel requirements of both domestic and foreign tourists in addition to second-home owners [27,28,29,30,31]. This disarray in academic discourse creates a significant research vacuum concerning rural transportation systems’ capacity to successfully meet the various mobility requirements of all user groups. In order to address the transportation needs of all rural residents and visitors, future research must take an integrated approach to investigate how rural transportation solutions can be created to guarantee inclusivity and be sustainable at the same time.

Comparing different mobility practices in various contexts is a crucial component of this research since it enables the assessment of which solutions are most practical and sustainable in particular situations. The effectiveness of various mobility initiatives in tackling the particular difficulties that rural areas face, such as poor transportation infrastructure, low population density, and financial limitations, will be compared in this study. In order to ensure that all user groups, including low-income families, the elderly, people with disabilities, and tourists, are taken into account, this comparative approach will also take into account the mobility needs of both temporary and permanent residents.

This study intends to offer useful insights into how tailored approaches can greatly improve the quality of life in rural communities, especially for vulnerable populations, by identifying these crucial elements and evaluating the relative effectiveness of different mobility solutions. In the end, the results will help develop socially inclusive and sustainable transportation models that promote community well-being and regional resilience, meeting the urgent need for comprehensive sustainable strategies for rural mobility that take into account the various needs of all users.

2. Materials and Methods

This study is part of a PhD research project titled “Habitat Matters: Managing and Reducing the Risk of Built Heritage by Promoting Ecological Transition, Accessibility, and Sustainable Mobility in Rural Areas”. This chapter outlines two distinct methodological approaches: one that supports the entire doctoral study by providing a comprehensive framework for addressing rural mobility challenges and another that is specifically tailored for the analysis presented in this article. Furthermore, it explains the methodology adopted for this article in relation to the broader framework of the PhD research. The doctoral project comprises three main phases: a foundational background study on sustainable mobility in rural Europe; an analysis of 24 good practices across 13 EU countries; and the development of guidelines to enhance rural mobility in alignment with ecological transition goals. This article focuses on a specific aspect of the second phase, examining the innovation and social impacts of mobility practices. It investigates four selected cases that prioritize inclusivity and community engagement, particularly targeting the needs of vulnerable and marginalized groups. By centering on the social dimension, this study provides a deeper insight into how mobility solutions can promote equity and participation, thereby making a significant contribution to the overarching objectives of the PhD research.

The PhD project methodology comprises three main phases. The first phase involved a comprehensive background study on sustainable mobility, its importance, and the challenges in rural European areas, including EU strategies, policies, and practices, resulting in two conference papers. This phase also included an analysis of transport conditions using expertise gained at MIC-HUB, a global transport planning company in Milan. The second phase focused on analyzing rural mobility systems in 13 EU countries, identifying 24 good practices (Table 1) to address gaps and opportunities for sustainable rural mobility. These practices were categorized into three main areas: mobility modes: mobility modes refer to the various types of transportation options available for individuals and communities to move from one location to another [32]; mobility infrastructure: the interconnected systems of communication, transportation, and regulations that support the flow of people, products, and information [33]; and mobility platforms: an integrated digital system that facilitates the management, access, and coordination of several transportation services [34].

The selection of good practices considered criteria such as geographical location and urbanization levels. Rural areas across Europe face unique mobility challenges, ranging from isolated mountain regions like the Alps and Scandinavian woodlands, which struggle with climatic and accessibility issues [35,36], to productive agricultural plains in southern and eastern regions, where sustainability and transport regulations are prioritized [37]. Economic diversity, encompassing sectors like renewable energy, tourism, and agriculture, influences infrastructure and mobility [38,39]. Additionally, transport investments and service accessibility are further complicated by population decline, aging demographics, and tourism pressures [40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47].

In the third phase of the doctoral study, we focus on defining guidelines based on tools and innovations identified through a comparative analysis of case studies to improve mobility and accessibility in EU rural areas within the context of ecological transition.

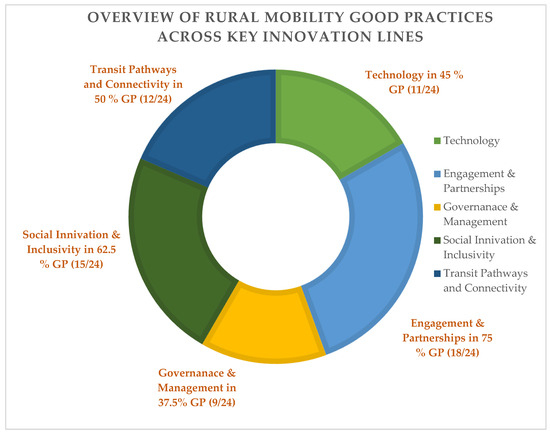

Given these necessary premises for the overall framework of the doctoral study where this article is rooted, the aim of this contribution is to analyze a specific aspect of sustainable mobility in European rural areas, namely the innovation and impacts of mobility in the social dimension of rural communities and particularly in their engagement in the decision-making process. As we analyzed the 24 practices for the larger PhD project, these two innovation fields were dominant, as presented in Figure 1. Figure 1 illustrates the innovative elements categorized into five key innovation lines: technological innovation, engagement and partnership, governance and management, transit pathways and connectivity, and social innovation and inclusivity. The 24 good practices reflect these elements, with engagement and partnerships leading at 75% (18 practices), emphasizing the role of teamwork in rural mobility solutions. Social innovation and inclusivity feature in 62.5% (15 practices), underscoring the focus on equitable access. Transit pathways and connectivity are present in 50% (12 practices), while technological innovation is highlighted in 45% (11 practices). Governance and management appear in 37.5% (9 practices), stressing the importance of effective planning. Together, these findings highlight diverse strategies that balance partnerships, technology, and inclusivity to address rural mobility challenges.

Figure 1.

Overview of rural mobility good practices across key categories and innovation lines. Note: The total percentage does not equal 100% because each good practice contributed to innovations in multiple categories.

This study adopts a qualitative methodology to provide an in-depth exploration of mobility in rural areas, focusing particularly on its social dimension to address the challenges faced by vulnerable groups and marginalized communities. The methodology involves selecting four good practices from a pool of 24 identified cases for an in-depth analysis. The majority of these cases demonstrate significant innovation in the social dimension and community engagement, highlighting the importance of inclusive and participatory approaches to addressing rural mobility challenges. Moreover, provided that this research investigates sustainability in the field of mobility, and given that the social dimension is one of the three pillars of sustainability, it is evident how the social perspective must be regarded as an essential element to look at when exploring sustainable mobility [48]. Additionally, social innovation and community engagement are critical components in rural mobility projects, particularly in areas with aging populations. In such settings, solutions cannot succeed without inclusivity. Community engagement is equally vital, as involving local residents helps build trust, ensuring they adopt the solutions without facing physical or economic risks. Furthermore, among the selected four practices, two are from the mobility mode category, as it is the dominant category within the 24, one is from mobility infrastructure, and one is from mobility platforms. The four selected practices are as follows:

- Cycling Without Age in Kalundborg and Lamvig, Denmark (Mobility Mode): this initiative aims to connect older people with society through voluntary rides.

- Transport on demand and shared mobility in Badenoch and Strathspey (Mobility Mode): this service addresses the needs of rural populations, particularly older people, by providing accessible transport, including vehicles for people with disabilities.

- Conversion of old rail trails into greenways in Ireland (Mobility Infrastructure): abandoned rail trails are converted into cycling paths, enhancing connectivity and preserving cultural heritage, similar to the renewed side railway in the Marche Region, from Fabriano to Pergola, that we have experienced during an international workshop.

- Service-to-People accessibility solution in Hallig Hooge (Mobility Platform): this initiative shifts the traditional mobility paradigm by bringing services directly to the doorstep of the isolated islanders of Hallig Hooge, many of whom are elderly.

A thorough and critical examination of the chosen good practices is the following stage, with an emphasis on understanding their novel elements, especially with regard to social inclusion and community involvement. This requires a thorough examination of how each practice encourages community members to actively participate, supports equitable access to services, and attends to the particular needs of marginalized groups, the elderly, and those with disabilities. We also evaluate how these practices contribute to building stronger social ties, encouraging volunteerism, and creating sustainable mobility solutions. Additionally, in some cases, like “Cycling Without Age”, the investigation looks at how effective and adaptable certain methods are to various geographical areas. We hope to ascertain these methods’ wider relevance and potential for resolving rural mobility issues throughout Europe by evaluating how easily they may be exported and adapted for usage in other rural locations. This stage is essential for understanding the effects of these activities locally as well as their potential to expand and improve accessibility and mobility in a variety of rural contexts.

Table 1.

Complete list of the 24 selected good practices from thirteen EU countries, as a result of the PhD thesis.

Table 1.

Complete list of the 24 selected good practices from thirteen EU countries, as a result of the PhD thesis.

| Categories | Good Practice Name | EU Country | Activation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mobility modes |

| Scotland | 2017–2020 |

| Denmark | 2012 | |

| Austria | 2017–2020 | |

| Latvia | 2017–2020 | |

| Scotland | 2018 | |

| Germany | 2018 | |

| Ireland | 2001 | |

| Germany | 2013 | |

| Germany | 2019 | |

| Italy | 2022 | |

| Mobility infrastructure |

| Italy | 2014 |

| Ireland | 2019 | |

| Ireland | 2021 | |

| Spain | 2017-2018 | |

| Poland | 2019-2021 | |

| Belgium | 2016 | |

| Scotland | 2021 | |

| Mobility platforms |

| Portugal | 2013 |

| France | 2009 | |

| Scotland | 2018 | |

| Italy | 2019 | |

| Finland | 2019 | |

| Denmark | 2019 | |

| Germany | 2018 |

3. Analysis and Results

As this study is part of a larger PhD project, we selected four good practices from the identified cases that drive social innovation and community engagement, as detailed in the methodology chapter. These include two from the category of “mobility modes” (the dominant category), one from “mobility infrastructure”, and one from “mobility platforms”, followed by outlining the key aspects of these practices below and in Table 2. First, a contextual overview of the three categories presented in Table 1 is provided, followed by an analysis of the selected practices in the subsequent chapter.

3.1. Contextual Overview

Rural areas are often characterized by low population densities, limited infrastructure, and a lack of viable public transportation options. Introducing new mobility services such as micromobility, shared mobility, transport on demand, integrated platforms, innovative infrastructures that support these modes of mobility can significantly address these challenges, fostering better connectivity, inclusivity, and accessibility in these regions. These solutions are categorized into mobility modes, mobility infrastructure, and mobility platforms, each addressing key aspects of transportation. Mobility modes, such as micromobility, shared mobility, and transport on demand, offer flexible alternatives to private vehicles. Mobility infrastructure, including bus and subway stations, bike lanes, pedestrian pathways, park-and-ride facilities, and mobility hubs, supports sustainable and interconnected networks. Meanwhile, mobility platforms, like on-demand, shared, and Mobility-as-a-Service (MaaS) platforms, integrate transportation options into seamless, user-centric systems. Together, these approaches provide innovative and adaptable solutions to enhance rural connectivity, sustainability, and accessibility.

3.1.1. Mobility Modes

Mobility modes refer to the various types of transportation options available for individuals and communities to move from one location to another [32].

For short distances, micromobility, which includes devices like e-bikes and scooters, represents a sustainable substitute for conventional motor vehicles. Studies demonstrate the benefits of e-biking for reducing sedentary lifestyles [48] and the advantages of active transportation, such as cycling, for mental health compared to driving [49]. Rural areas do, however, present certain difficulties, such as the restricted accessibility of transit hubs. For instance, more than 80% of people in the Netherlands reside 7.5 km or less from a train station, so increasing the cycling range is a practical way to facilitate access to these hubs. [50]. Practical disadvantages of e-biking include the requirement for specific gear and weather protection [51], as well as speed and carrying capacity restrictions that could make multipurpose travel more difficult [52]. With lifecycle emissions varying from 4.7 to 25 g of CO2 per person-kilometer, depending on the region and study, e-bikes have a significantly lower environmental impact than motorized vehicles despite these difficulties [53,54,55]. Conventional bicycles, on the other hand, have comparable but marginally lower emissions [56]. Users of micromobility continue to have serious concerns about safety. Compared to motor vehicle occupants, cyclists are at a 10-fold increased risk of accidents, a 1.8-fold increased risk of injury, and a 1.3-fold increased risk of death [57,58,59]. Head injuries are the most common cause of death on urban roads, where they frequently result from collisions with motor vehicles [60,61].

For rural and low-demand locations, on-demand transportation (ToD) services provide customized solutions that promote inclusivity, sustainability, and flexibility. Studies conducted in Switzerland have shown that these services lower CO2 emissions, with averages of 129.75 g per person-kilometer in urban settings and 135.5 g per person-kilometer in rural areas [62]. Economically speaking, ToD uses smaller fleets of vehicles, vans, or buses, requires smaller budgets than typical public transport systems, and has even been provided for free in Latvia under EU funding [63]. Features like child safety seats, seat belts, surveillance cameras, and door-to-door evening services all contribute to increased safety [64]. Another characteristic of ToD is social inclusion, which enables people with impairments, older adults, and rural dwellers to access necessary services [63]. With dynamic scheduling, virtual stops, and door-to-door services, ToD provides convenience over fixed-route transit, cutting down on waiting times and walking distances while guaranteeing on-time arrivals [65,66]. ToD’s advantages in price, accessibility, and convenience greatly improve the quality of life in rural areas, despite certain reliability issues still being when compared to regular public transportation.

Shared mobility offers an alternative that lowers energy use, pollution, traffic, and parking demand, especially in rural areas where public transportation is less practical [67]. Nevertheless, disadvantages include a loss of individual travel autonomy [68] and longer journey times for carpooling as opposed to driving alone [69]. Studies like those on BlaBlaCar, which maintained an average vehicle occupancy of 3.9 people in 2018 and saved 1.6 million tons of CO2, show that carpooling systems have the potential to be sustainable [70,71]. According to studies, carpooling dramatically lowers CO2 emissions per person-kilometer to about 104.6 g, as opposed to the global average of 272 g per person-kilometer for cars with regular occupancy [72]. Despite its advantages, carpooling adoption is nevertheless hampered by safety concerns, with the dangers of sharing personal space and having less control over travel being seen as major turnoffs [73,74]. However, shared mobility promotes inclusivity by meeting the requirements of pensioners, non-drivers, and rural dwellers who want to socialize, strengthening ties within the community [75].

3.1.2. Mobility Infrastructure

Transport infrastructure plays a vital role in advancing sustainability, managing costs, and creating significant societal impacts. Mobility infrastructure encompasses the interconnected systems of communication, transportation, and regulations that facilitate the flow of people, products, and information, forming the foundation for diverse social and economic activities [33]. Important elements include railway and subway stations, which are vital for commuter and intercity travel, and bus terminals and stations, which are vital hubs for local and regional bus services. Rail tracks facilitate high-capacity train systems, which allow for the efficient movement of people and goods. Bus terminals and stations also encourage public transit, which emits significantly less CO2 per passenger than private vehicles—the Federal Transit Administration (FTA) estimates that transit systems emit an average of 0.45 pounds of CO2 per passenger mile, whereas single-occupancy private vehicles emit roughly 0.96 pounds per passenger mile. Public transportation lowers greenhouse gas emissions by providing a more effective way to move people [76,77]. Although costs vary depending on project scope and location, investments in bus infrastructure can improve connectivity and ease congestion. For example, it has been demonstrated that the installation of bus rapid transit (BRT) systems, which have dedicated bus lanes and stations, improves transit efficiency and reduces traffic congestion [78].

Subway systems are also essential for cutting emissions and easing urban congestion; studies show that cities with subways have 50% lower CO2 emissions than cities without, which adds to an 11% drop in CO2 emissions worldwide. Widespread subway installation might reduce emissions by up to 77%, which would significantly improve the quality of the air in contaminated urban areas [79,80]. However, because of the demands of their construction and operation, subways are among the most costly infrastructure solutions [81]. In addition to encouraging healthier lifestyles and lowering dependency on motor cars, bike lanes and pedestrian greenways provide affordable, sustainable options for active transportation. According to a systematic review, street vegetation promotes active travel and improves environmental esthetics and safety, while weather and safety issues may have an impact on how beneficial they are [82]. Community-focused features, such public areas, encourage communication and social engagement. By enabling drivers to switch to public transportation, park-and-ride (P&R) facilities improve mobility and lower emissions and traffic. Their usefulness is directly related to how close they are to dependable transit networks, and their strategic location greatly boosts usage [83,84]. But according to research, P&R facilities at end-of-line stations are more successful at lowering greenhouse gas emissions than those at inner-corridor stations [85]. Mobility hubs provide concentrated areas for consumers to access numerous forms of transportation, such as shared mobility and micromobility, further integrating these modes of transportation while lowering emissions and improving connection [86]. Although mobility hubs can need large upfront investments, these expenses are frequently compensated for by improved accessibility and long-term advantages; therefore, strategic planning is crucial to their success [87]. Bike lanes, pedestrian greenways, P&R facilities, and mobility hubs all work together to create a sustainable and affordable framework for contemporary mobility systems that promote healthier urban environments and less traffic and emissions.

3.1.3. Mobility Platforms

A mobility platform is a system that integrates various transportation services, enabling users to plan, book, and pay for multiple types of mobility through a unified interface, typically via a digital application. These platforms aim to provide seamless, efficient, and user-centric access to transportation options, reducing reliance on private vehicle ownership and promoting shared mobility solutions [34]. By offering individualized routes and schedules, on-demand mobility platforms improve accessibility in underserved and rural areas while delivering flexible, user-requested transportation services. These platforms promote convenience and inclusion while lowering emissions and infrastructure costs through delivery route optimization and the use of smaller fleets [88]. To guarantee operational effectiveness and equity, however, successful implementation necessitates meticulous planning, community involvement, and fair service allocation. To optimize their advantages, issues including bridging the digital gap, guaranteeing affordability, and integrating these services with current public transportation must be resolved [89]. By utilizing technology to ensure safety and dependability, hitchhiking platforms update conventional methods. For instance, RezoPouce in France uses a digital interface to link drivers and passengers, encouraging shared travel and promoting sustainability, particularly in areas with limited access to public transportation [90,91]. By making it easier to access shared vehicles like automobiles, bikes, and scooters, shared mobility platforms encourage resource optimization and lessen the need for individual ownership [92]. Although these platforms have drawbacks including logistical issues and lengthy travel times that necessitate careful planning, they also reduce emissions and improve user collaboration [93]. In order to promote multimodality and increase access to public transit through shared-use alternatives, Mobility as a Service (MaaS) unifies many forms of transportation onto a single platform [94,95,96]. The adoption of MaaS can be prohibitively expensive, despite its potential, and there are issues with data security and privacy that need to be resolved for wider use [97,98]. Last but not least, accessibility-focused transportation systems offer tailored solutions for isolated or underprivileged locations, enhancing access to vital services like healthcare and education. In order to reduce travel barriers that impede social participation and economic development, the Service-to-People Accessibility Solution, for example, assists inhabitants in remote locations in effectively accessing essential services [99].

3.2. Analysis of the Selected Practices

Four practices that best support vulnerable groups and promote social inclusivity were chosen for this analysis. Specific criteria, such as inclusivity and accessibility, which prioritize fair access for marginalized groups, and community engagement and impact, which emphasize building social ties and empowering local communities, guided the selection process. Another important consideration was sustainability, which gave long-term, ecologically friendly solutions top priority. Transferability was also taken into account, guaranteeing that the procedures could be modified and repeated in various settings. Lastly, cultural and regional relevance was important because it addressed particular regional issues and ensured alignment with local customs. From a pool of 24 practices, we were able to select 4 that stood out based on these criteria as effective and flexible ways to improve inclusivity in mobility systems.

3.2.1. Good Practice #1: Cycling Without Age in Kalundborg and Lamvig, Denmark (Mobility Mode: Micromobility)

Description of the Context

Denmark’s seaside municipality of Kalundborg is distinguished by a blend of urban and rural surroundings. Its topography consists of both industrial areas and agricultural land. With a dispersed settlement layout, the city is home to about 17,000 people. Furthermore, there is a strong emphasize on community engagement. Community engagement is central to ecological and industrial projects like the Kalundborg Symbiosis. Residents, businesses, and local authorities collaborate to promote sustainability, with public consultations and educational programs fostering awareness and involvement. This participatory approach ensures that projects align with environmental goals and benefit the entire community.

Similar rural surroundings can be seen at Lemvig, a small, isolated town in western Denmark with a population of about 7500. The town experiences a coastal climate, with mild summers and windy winters. Its geography makes it a hub for renewable energy projects, particularly wind energy. Both locations struggle with issues like inadequate public transportation and accessibility [100,101,102].

Description of the Practice

Cycling Without Age is a global movement launched by Ole Kassow in 2012 in Copenhagen, Denmark, to reconnect elderly and less mobile individuals with their communities through cycling. The initiative, now present in over 50 countries, uses trishaws—three-wheeled rickshaws as presented in Figure 2, that provide comfortable, accessible transportation. It began when Ole envisioned the joy that a simple bike ride could bring to someone with limited mobility. Focusing on Kalundborg and Lemvig in Denmark, the program also demonstrates its success in rural and remote areas, fostering social inclusion and revitalizing community ties.

Figure 2.

Trishaw picture from Cycling Without Age official web page.

The movement is based on values like connections, slowness, generosity, storytelling, and accepting aging in a healthy way. With over 3050 chapters across more than 50 countries, it has expanded into a global network that employs over 4900 trishaws and is piloted by 39,000 volunteer pilots. By giving them “the right to wind in their hair” and re-engaging them with their communities, it essentially promotes social inclusion, intergenerational relationships, and the well-being of senior adults.

This initiative aims to target three Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), as presented in Figure 3. By promoting mental and physical well-being among the elderly, this initiative aims to achieve Goal 3 (Good Health and Well-Being), Goal 10 (Reduced Inequalities), and Goal 11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities) by promoting sustainable, eco-friendly mobility solutions that strengthen local community ties and ensure inclusive access to outdoor activities and social engagement. Through its grassroots foundation and robust volunteer network, Cycling without Age keeps innovating and growing, demonstrating that improving social cohesion and well-being can coexist alongside sustainable transportation solutions [103,104,105].

Figure 3.

SDGs targeted in “Cycling Without Age” good practice (Source@sdgs.un.org).

Issues and Critical Elements

- Social Isolation: Many older people experience social isolation, especially those who reside in nursing facilities or have limited mobility. Their inability to move about or access transportation prevents them from participating in social activities that allow them to meet new people and learn about their communities.

- Loss of Independence: As people age, they often become less independent, especially in terms of mobility. Many older people are less able to engage in outdoor activities and socialize with others because they are unable to walk or pedal long distances.

- Physical and Mental Health: Exercise and exposure to fresh air are critical for the general well-being of older adults. An older person’s mental and cognitive health might suffer from spending too much time indoors, and many of them have little access to outdoor spaces or activities that promote health.

- Generational Connection: Enhancing intergenerational relationships was another goal of the program. By recruiting volunteers, often younger people, to go on bike rides with the elderly, “Cycling Without Age” fosters intergenerational relationships and provides younger people with the chance to engage with them in meaningful ways.

Main Elements

- Restoring Mobility and Freedom: Older people who might no longer be able to ride motorcycles because of mobility issues can now experience the freedom that comes with riding a rickshaw. Their sense of independence and connection to nature are restored by this small gesture.

- Intergenerational Bonding: The program helps senior passengers and volunteer cyclists (pilots) develop deep connections. In addition to providing transportation, these rides promote memory sharing, storytelling, and intergenerational trust, all of which improve the emotional and mental health of senior citizens.

- Scaling through Volunteerism: The concept’s rapid and natural growth through word of mouth demonstrates the power of community-based innovation. Beginning with a small group of volunteers, the project swiftly expanded throughout Denmark and abroad as more people were motivated to join.

- Combating Ageism: By actively involving senior citizens in an activity typically associated with youth and physical fitness, the pilot combats societal ageism and advances the notion that one’s age should not determine one’s capacity to enjoy life and maintain an active lifestyle.

Innovations in This Good Practice

- Engagement and Partnership: The foundation of Cycling Without Age is volunteerism, which allows local communities worldwide to participate in providing free trishaw rides to senior persons. By recruiting local volunteers, the program combats senior isolation and fosters social contacts. This community-driven approach not only enhances well-being but also strengthens intergenerational bonds and creates a more welcome and supportive environment in the communities it serves.

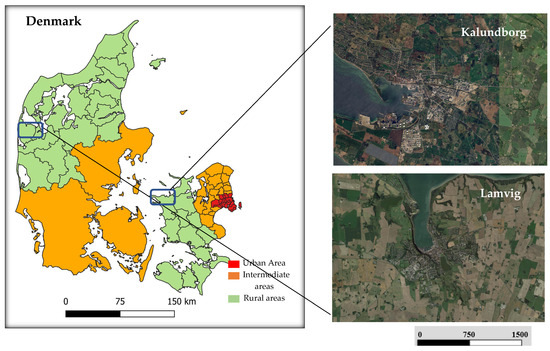

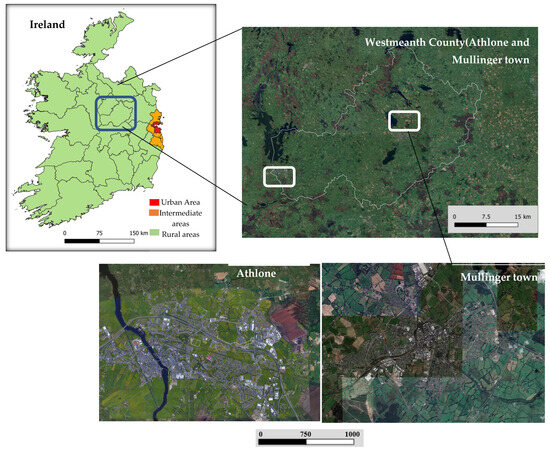

- Social Inclusivity: It prevents social isolation, bridges generational divides, and ensures that older people may engage in communal life. It improves seniors’ quality of life by allowing them to engage with their environment and enjoy the outdoors. Apart from this, the locations of Kalundborg and Lemvig are presented in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Good practice #1 case study area (Data source @Eurostate and Google satellite).

Figure 4. Good practice #1 case study area (Data source @Eurostate and Google satellite).

Worldwide Expansion

The simplicity, adaptability, and community-driven structure of the Cycling Without Age (CWA) approach are the main elements contribute to its global success. The basic idea—using trishaws to provide elderly and less mobile people with bike rides—is simple to execute and does not require a lot of infrastructure, so it can be tailored for different areas. Local chapters can modify the project to suit their needs while upholding its essential objectives thanks to the open-source methodology, which shares resources and good practices. In order to help new chapters get off to a quick start, the organization also offers a thorough toolbox that includes advice on trishaw procurement, volunteer recruiting, fundraising, safety procedures, and local partnerships. The movement’s growth is driven by a grassroots, volunteer-based structure, with money and support coming from local partnerships. Social media and favorable media coverage have increased the initiative’s awareness, and CWA is thriving in more than 50 countries thanks to its robust global network of chapters that encourage cooperation and knowledge exchange.

3.2.2. Good Practice #2: Transport on Demand and Shared Mobility in Badenoch and Strathspey (Mobility Mode: On Demand and Shared Mobility)

Description of the Context

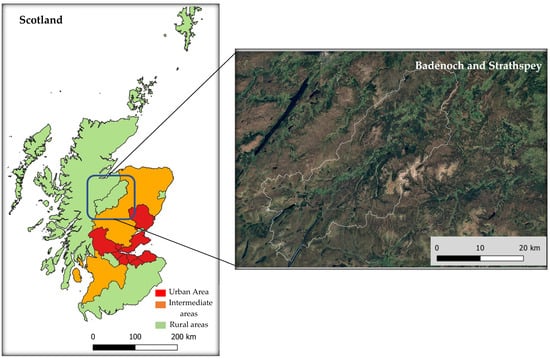

The Scottish Highlands region of Badenoch and Strathspey as presented in Figure 5, is a varied and picturesque area known for its breathtaking natural scenery, which includes moorlands, forests, and mountains. The surrounding territories are made up of small villages and remote dwellings, with a limited population dispersed across large, rocky terrains; these places are well known for outdoor tourism activities including hiking, skiing, and birdwatching. In addition to being a natural retreat, Badenoch and Strathspey is rich in cultural legacy, with communities long associated with traditional activities like shinty, a sport that is essential to village life. Even while tourism contributes significantly to the economy, many of the most isolated areas still have difficulty accessing amenities like transportation. Mobility issues are made worse by the region’s climate, which includes severe winters and mountainous terrain, particularly for the elderly and people with mobility impairments [106,107].

Figure 5.

Good practice #2 case study area (Data source@Eurostat and Google satellite).

Description of the Practice

The Badenoch and Strathspey Community Transport Company (BSCTC), also known as “Where2Today?”, is a charitable organization that has been operating for over 20 years, providing accessible and affordable transportation services for local residents and visitors in the Badenoch and Strathspey area of Scotland. The services, which provide vital transportation to healthcare, social events, and other everyday requirements, are especially beneficial for people with mobility or geographic issues. The charity helps vulnerable and mobility-impaired people access these essential services by running a minibus service and a community car program.

By purchasing accessible cars and minibusses to run Section 22 community bus routes, scheduled public transportation services run by nonprofit organizations, BSCTC gradually increased the scope of its offerings. In underserved locations, these routes enable BSCTC to offer consistent, reasonably priced transportation options. Although Section 22 services, in contrast to regular commercial bus routes, are allowed to charge fees and may employ paid drivers, its main goal is to increase social welfare and accessibility. By providing a dependable, door-to-door transportation alternative that many people rely on, these services, which are available Monday through Friday, encourage social connection and lessen isolation.

BSCTC quickly responded to the needs of the community during the COVID-19 pandemic by setting up support teams to provide necessities, strengthening volunteer–service user relationships, and especially enlisting younger volunteers to assist the elderly [108,109].

Issues and Critical Elements

- Limited Access to Public Transportation: Due to Badenoch and Strathspey’s low population density, regular service operations are financially untenable for transport operators. Many residents are unable to use public transportation for essentials because of the limited routes and erratic mobility due to the small population.

- Insufficient Assistance for Seniors and Residents with Limited Mobility: Many times, older or less mobile persons cannot use the public transportation options that are now available. Buses may lack accessibility features like wheelchair spaces or low floors, which makes it difficult for these individuals to travel on their own, particularly in more remote areas.

- Limited Door-to-Door Transportation Options: For those who are unable to utilize conventional public transportation, there are not many door-to-door transportation options. The capacity and availability of the already available community transport options are sometimes limited, and many residents, especially the elderly and disabled, find it challenging to travel to bus or rail stops. As a result, residents become isolated and are unable to access essential services.

Essential Elements

- Social Inclusion: to improve the social inclusion of senior citizens and others with mobility impairments by offering reasonably priced and easily accessible modes of transportation, guaranteeing their access to daily necessities, social activities, and healthcare.

- Sustainability: to create a long-term, community-driven transportation strategy that relies on volunteer assistance and local collaborations to sustain operations and grow services.

- Community Cohesion: to promote social interaction, engagement in activities, and better access to community life by providing transportation options that lessen isolation and strengthen links within the community.

- Improved Mobility: to solve rural areas’ mobility issues by providing adaptable, affordable, and easily accessible transportation options, particularly in places with few or no public transportation options.

Innovation in This Good Practice

- Engagement and Partnership: The program encourages cooperation between regional parks, local government agencies, tourism offices, and community businesses, promoting alliances for sustainable, locally driven solutions. The Community Transport Association (CTA), a UK charity that assists neighborhood organizations in providing necessary transportation services, founded the service. Its main goal is to increase everyone’s access to transportation.

- Social Inclusivity: The program’s major goal is to transport the elderly and disabled, who are frequently left out of the mainstream transportation system. Those who have trouble climbing stairs can easily reach their vehicles thanks to lifts or ramps. Skilled drivers provide passengers with individualized door-to-door assistance.

Key Features and How the Section 22 Permit/Service Works

The Section 22 community bus service is a specific type of bus service in the UK that is authorized under Section 22 of the Transport Act 1985. It is not a physical bus or a route provided by the UK government but rather a legal framework that allows community transport organizations (typically not-for-profit, charitable, or voluntary groups) to operate bus services for the general public.

Key Features:

- Operated by Not-for-Profit Organizations: Section 22 services are operated by community transport organizations or other non-profit entities, meaning that the focus is on service provision rather than making a profit.

- Public Service: since Section 22 services are available to the entire public, they are inclusive and generally accessible in contrast to many other community transportation programs that are restricted to particular demographics (such as the elderly or the disabled).

- Volunteers: Fully trained volunteer drivers who may possess specialized licenses to handle larger vehicles are frequently used to operate the bus services. This volunteer expectation promotes community involvement while keeping expenses down.

- Localized and Adaptable Routes: Section 22 services are intended to fill in the gaps in public transportation. They usually work in places like rural or underserved communities where traditional bus companies do not provide enough services. Buses can frequently be reserved in advance for door-to-door services, and the routes and schedules are adjusted to meet the demands of the community.

- Vehicle Accessibility: to ensure that even individuals with mobility impairments may utilize the service, these services frequently make use of cars that are accessible to individuals with disabilities, such as minibuses equipped with wheelchair lifts.

- Fare Collection: although fares may be assessed for passengers, they are typically subsidized and reasonably priced because the service’s objective is to serve the community’s needs rather than make a profit.

- Funding and Licensing: in order to legally run the bus service, Section 22 services must register with the Traffic Commissioner and ask for funding from local authorities.

How it works:

- Service Type: It is a public local bus service run by non-profit organizations or community transport groups in contrast to commercial bus services. These services are especially intended to cover gaps in public transportation in places like rural or remote areas where commercial operators do not offer enough services.

- Operators: Non-profit groups, such community transportation companies or charities, are in charge of operating Section 22 services. These groups submit an application for a Section 22 permit, which enables them to operate the service lawfully and collect fees.

- Government Role: Community organizations must apply for licenses under Section 22 and the legal framework provided by the UK government (via the Traffic Commissioner). Although community organizations, not the government, provide the services directly, the government may also offer grants or subsidies through local authorities to assist pay for these activities.

- Volunteer Involvement: A large number of Section 22 services are run by volunteer drivers and are intended to be accessible and reasonably priced to cater to the needs of the community, frequently targeting those who are old, disabled, or otherwise underserved by conventional public transportation.

3.2.3. Good Practice #3: Conversion of Old Rail Trails to Greenways, Ireland (Mobility Infrastructure: Bike Paths and Pedestrian Ways)

Description of the Context

The central Irish county of Westmeath is well known for its picturesque lakes, pastoral scenery, and extensive history. It is located in the Leinster province and is distinguished by the way that urban and rural areas coexist. The county, which takes its name from the old Meath region, boasts a rich cultural legacy that draws tourists to its numerous historic sites, castles, and monuments. Towns like Athlone, a significant regional center on the Shannon River, and Mullingar, the county’s largest town and economic center, are located there. The Loughs (lakes) like Lough Ennell and Lough Ree, which support outdoor tourism pursuits including boating, fishing, and walking, are among the county’s well-known natural beauties.

However, rural Westmeath has issues like restricted mobility, particularly for senior individuals, and limited access to basic services. However, the local economy depends on tourism, agriculture, and light industries, and its central location provides access to major cities. Infrastructure and transportation services for both urban and rural populations are being improved [110].

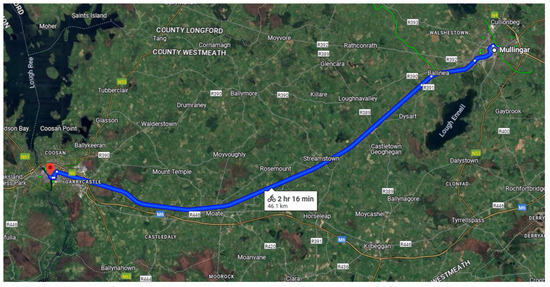

Description of the Practice

The Old Rail Trail as presented in Figure 6 and Figure 7, is a 43 km cycling path located in County Westmeath that stretches between the towns of Athlone and Mullingar as shown in Figure 8, offering a scenic and peaceful journey through Ireland’s heartland. This Greenway is a converted section of the historic Midlands Great Western Railway, providing cyclists with a tranquil ride through lush landscapes, restored railway stations, and under beautifully preserved stone-arched bridges. The route connects two important waterways, the River Shannon in Athlone and the Royal Canal in Mullingar, making it a perfect mix of natural beauty, historical landmarks, and cultural heritage.

Figure 6.

Section of Old Rail Trail in Mullingar, Ireland.

Figure 7.

Old Rail Trail bicycle path (Source@Google sattelite).

Figure 8.

Good practice #3 case study area (Data source@ Eurostat and Google satellite).

Cyclists of all ages and abilities will find the trail accessible, with mostly flat surfaces and gentle slopes, making it ideal for families. Along the route, visitors can explore attractions such as Athlone Castle, the Dún na Sí Amenity & Heritage Park, and the historic Castletown Station. For those interested in Ireland’s mythological past, a short detour to the Hill of Uisneach, the ancient seat of Ireland’s High Kings, offers a memorable experience. The trail can be completed in about six hours, but with so much to see along the way, its best enjoyed at a leisurely pace with plenty of stops to explore the surroundings.

To further enhance visitors’ experiences, the trail leverages technological innovations like GPS-enabled maps and smartphone apps for efficient route planning, nearby lodging options, and up-to-date weather forecasts. QR codes placed at key historical sites provide instant access to contextual information, enriching the understanding of each location. Additionally, augmented reality (AR) features allow cyclists to explore the canal’s rich industrial past through immersive digital recreations, bringing the area’s legacy to life. These digital enhancements not only make navigating the trail easier but also create a more engaging and educational connection to the region’s history and attractions [111].

Issues and Critical Elements

- Abandonment and Decay of Historical Rail Lines: A number of the region’s old rail lines have been abandoned, leading to overgrowth and ruin. These abandoned rails are now unused resources because so much of the infrastructure is decaying. Reviving these lines could help restore lost transit linkages and enhance regional connectivity.

- Absence of Paths for Safe Bicycling and Walking: Designated bike and walking lanes were desperately needed to encourage better living and environmentally friendly transportation. Because residents and visitors lacked safe paths for bicycling and walking, inadequate infrastructure made it challenging to promote environmentally friendly travel and outdoor activities.

- Economic Revitalization: Reviving these transit networks, which comprised train lines and sidewalks, provided a chance to boost the local economy. By attracting tourists and supporting local small businesses, better transportation infrastructure may stimulate economic growth, create jobs, and make the area a more desirable vacation destination.

Main Elements

- Preservation of Heritage along the Route: The Old Rail Trail incorporates historic features including intact stone arch bridges and rebuilt railway station structures (such as Moate and Castletown Stations). These historic buildings enhance the cultural experience by acting as educational stops in addition to adding elegance.

- Uisneach Historical Site: by linking nature and history, the trail leads to the Hill of Uisneach, a significant archeological and mythological site that enhances tourists’ experiences.

- Diverse Access Points: From Athlone to Mullingar, the route has a number of access points. Important places like Castletown Station, Newbrook, and Tully offer free parking. This makes it more accessible and adaptable for a variety of user groups (families, visitors, and locals) by enabling users to start or finish their journey at multiple locations.

- Connection with Other Greenways: The Old Rail Trail has a direct connection to the Royal Canal Greenway, which extends the trail network by connecting to places like Longford and Dublin. Longer distances for ecotourism and multi-day excursions are encouraged by this cross-connectivity.

- Family-Friendly Infrastructure: All ages may enjoy the trail’s level, well-kept routes, and a variety of bikes, including electric and tandem bikes, are available for rent. Both experienced bikers and families with small children can enjoy the trail thanks to its inclusive design.

- Eco-Tourism Support: The trail promotes eco-friendly travel by offering bike hire facilities at several points (Athlone, Moate, and Mullingar). The easy terrain also makes it possible for cyclists to cover the entire 43 km route without needing a car, aligning with sustainable tourism practices.

- Attractions along the Trail: The route is dotted with key attractions like Athlone Castle, Dún na Sí Amenity & Heritage Park, and the Hill of Uisneach. This makes the trail not just a cycling route but also a cultural and recreational journey, encouraging the exploration of nearby towns and heritage spots.

Innovation in This Good Practice

- Social Inclusivity: The path features “Greenway Hubs”, which are powered by sustainable solar energy and provide drinking water, bike racks, sitting, and shelter. While taking a rest, guests can use smart seats with USB ports to charge their gadgets. By incorporating accessibility features, the path is made inclusive and friendly for people of all abilities, improving sustainability and convenience for all visitors.

- Community Engagement: By bringing communities together and interacting with them through refurbished historic buildings, the trail promotes social inclusion. The trail’s integration of historical features along its path not only protects cultural heritage but also promotes community engagement, strengthening ties between locals and tourists.

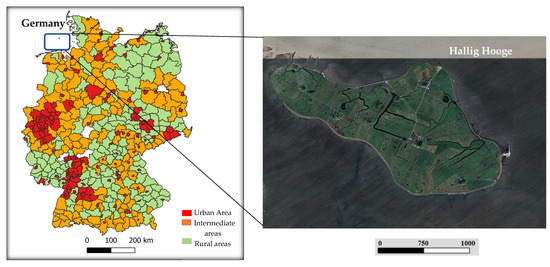

3.2.4. Good Practice #4: The Service-to-People Accessibility Solution in Hallig Hooge (Mobility Platform: Service-to-People Accessibility Platform)

Description of the Context

Located in Schleswig-Holstein, Germany, Hallig Hooge is a small, flat island in the North Frisian Wadden Sea. There are about 120 people living there, and during severe winter storms, it is sometimes submerged. The island has vast salt marshes on its eastern and western sides, as well as sizable fallow lands that are occasionally utilized for raising animals. A valuable habitat for migratory birds, Hallig Hooge is distinguished by its exposed mudflats that emerge during low tide. Along with being a vital stopover for many migratory birds and waders, the island is home to a number of breeding species, including the Common Redshank and Eurasian Oystercatcher. The island, which is reachable by ferry, is a special place for environmental tourism and birdwatching because of its small, grouped towns and natural setting [112,113].

Description of the Practice

The Service-to-People Accessibility Solution, created by Diakonie Schleswig-Holstein as part of the MAMBA project, addresses the unique mobility challenges of Hallig Hooge, Germany, and its location map is presented in Figure 9. Hallig Hooge required a novel approach to ensure access to essential social services because it had just 109 residents and insufficient mobility. The primary problem was that islands frequently had to travel to the mainland to access services like social counseling, healthcare, and shopping. Due to limited transportation choices and the community’s reliance on horse-drawn carriages for tourists, Diakonie developed a mobile social counseling service to offer these services directly to the inhabitants.

Figure 9.

Good practice #4 case study area (Data source@Eurostat and Google sattelite).

This program employs a reverse service delivery strategy by delivering basic services like healthcare, groceries, and social support directly to individuals. By using mobile devices and digital technologies like video conferencing, it removes barriers to mobility and distance, allowing citizens to obtain essential services from the convenience of their homes. This creative idea guarantees that people can obtain vital care without having to travel great distances, even in rural locations.

The project started with regular meetings at the neighborhood store, “Markttreff”, which acts as a community center, in close collaboration with the island’s mayor and residents. Residents of the island voiced a wish to age in comfort on the island without having to travel for basic amenities. In response, the solution provided elder care training, on-site counseling, and integrated video conferencing technology to link residents with mainland medical professionals. Despite the elderly population’s lack of familiarity with digital technology, video conferencing and hands-on, in-person care training sessions were successfully implemented. Plans for service expansion, including dementia training and continuing social care on-site, resulted from the community’s positive involvement with the project [114].

Issues and Critical Elements

- Geographic Isolation: Hallig Hooge is a small island in the North Sea that is difficult to get to and frequently floods. Residents have to take a 1.5 h ferry to reach the mainland, which significantly limits their access to essential services and makes daily life challenging, especially during bad weather.

- Lack of Public Transport: People cannot use public transportation, and there are not many cars on the island. Because of this, a lot of people have trouble getting around, particularly those who cannot drive, which limits their ability to travel for work, shopping, or medical appointments.

- Aging Population: A significant portion of the island’s population is old, and they frequently require access to social services and medical care. However, due to the island’s remote position, it might be challenging and time-consuming to go to the mainland for services like doctor’s appointments.

- Digital Divide: Many senior citizens on Hallig Hooge have limited access to online services due to their incapacity to use digital technologies. They have a harder time accessing social media, healthcare, and online government services because of the digital divide.

Main Elements

Mobile social counseling combined with video conferencing: Because of this dual solution, residents who might otherwise find it impossible to access fundamental services like healthcare and social support due to the island’s remote position can now acquire them directly. Residents can overcome the obstacles of distance by connecting with main-land professionals via video conferencing for consultations, medical guidance, and social help, while mobile units with specialists on staff visit the island to provide in-person services. This idea fosters social inclusion, reduces isolation, and offers a scalable and sustainable model for other remote or underprivileged areas, all while enhancing the physical and emotional health of the population. By using digital technology and on-site mobility, this method sets a new benchmark for providing services to those who live far away, offering continuous care without requiring significant infrastructure investments.

Innovation in This Good Practice

- Community involvement: The people of Hallig Hooge actively contributed to the project’s development. A “solution tree” and frequent meetings gave locals a way to express their priorities and participate in decision making. By ensuring that services like mobile counseling and healthcare were customized to the unique needs of the island, this strategy helped to build a strong sense of trust and ownership among the residents.

- Social Inclusivity: Through in-person meetings and telemedicine, vital social services like healthcare and counseling are provided directly to isolated residents on Hallig Hooge, especially helping the elderly. By providing assistance to vulnerable people, this strategy promotes social innovation and increases inclusivity.

How the Idea Was Developed

- Identifying the Need: The small, isolated island of Hallig Hooge has limited access to essential services such as healthcare, social counseling, and elderly care. With no public transport except for a ferry to the mainland, residents, particularly the elderly, face challenges in accessing services. Community meetings, led by Diakonie Schleswig-Holstein and the island’s mayor, revealed that the population wanted to age in place without having to frequently travel to the mainland for services.

- Involving the Community: From the outset, regular meetings were held with the island’s residents at the local hub, “Markttreff.” These meetings allowed the residents to express their needs and concerns, such as the desire for local elderly care training and social counseling. A “solution tree” was created to visualize the issues faced by the residents and identify priorities. This inclusive approach ensured that the solution directly addressed the community’s specific needs.

- Mobile Social Counseling: Diakonie developed a mobile social counseling service that brought professional counselors to the island to offer face-to-face consultations on-site. This ensured that islanders could access crucial services without needing to travel. Special attention was given to elderly residents, with courses offered on-site to help community members learn how to care for their aging neighbors, promoting self-sufficiency in elderly care.

- Introduction of Video Conferencing: Recognizing the limitations of on-site services due to geographical isolation, the project introduced video conferencing technology to connect islanders with healthcare and social service professionals based on the mainland. This technology allowed for remote consultations, including discussions with doctors, social workers, and specialists. For example, a video conference with a dementia specialist was organized to provide residents with knowledge and training on how to support elderly individuals with dementia. Despite the older population’s initial unfamiliarity with digital tools, the project ensured that the video conferencing was easy to use, and early trials of digital consultations were met with success, with a high-quality digital transmission.

- Combining Digital and Face-to-Face Services: The project combined on-site services (such as elderly care training and social counseling) with remote digital services (via video conferencing), creating a hybrid model that allowed the community to access a wide range of services without the need for frequent travel to the mainland. This dual approach balanced the community’s preference for face-to-face interaction while also leveraging technology to overcome geographical barriers.

- Expanding the Scope: The success of this hybrid model encouraged plans to expand the video conferencing system further, with upcoming online courses planned for dementia care and other health-related issues. The long-term goal was to continue providing services to vulnerable groups on the island, including the elderly, people with disabilities, and families in crisis, ensuring ongoing accessibility to essential services through both digital and in-person means.

- Ensuring Sustainability: Regular meetings with the islanders and collaboration with the Diakonie’s In-House Mobility Centre ensured that the solution remained responsive to the community’s needs and evolved over time. The project also emphasized the importance of community trust by involving the islanders in every step of the planning and execution process.

3.3. Synthetical Overview and Comparative Analysis of the Four Selected Practices

In this overview, we summarize information about innovation, relevant demographic details and compare important aspects of the selected good practices, which are presented in Table 2, Table 3 and Table 4 to facilitate the discussion in this article.

Table 3.

Innovations overview of the four selected practices.

Table 4.

Comparative analysis table of the four practices.

Table 2.

Population dynamics, land area, and density of case study areas for in-depth analysis.

Table 2.

Population dynamics, land area, and density of case study areas for in-depth analysis.

| Name of Good Practices | Land Area Sq.km | Total Population | Population Dynamics | Population Density pr sq km | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0–19 Years (2022) | 20–64 Years | 65 Year and Above (2022) | |||||

| 2011 | 2024 | ||||||

| 16.76/4.95 | 23,575 | 23,360 | 4603 | 12,128 | 4371 | 988.1/1373 |

| 2331 | 13,680 | 12,782 (2022) | 2319 | 7003 | 3456 | 5.484 |

| 32.57 | 43,262 | 48,846 (2022) | 12,547 | 28,956 | 6533 | Avg (1414.57) |

| 5.78 | 109 | 101 (2022) | 19 | 54 | 28 | 17.30 |

4. Discussion and Conclusions: Comparative Analysis of the Four Selected Practices

4.1. Discussion

Enhancing rural mobility requires a multifaceted approach that leverages mobility modes, infrastructure, and platforms. Each of these categories addresses specific aspects of transportation challenges, yet their effectiveness lies in their interdependence, forming a cohesive and sustainable mobility ecosystem.

Mobility modes that provide flexible alternatives to private automobiles include shared mobility, micromobility, and transport on demand. Micromobility, which includes e-bikes and scooters, encourages active lifestyles, enhances mental health, and supports low-emission, sustainable commuting. Carpooling is one example of a shared transportation system that lowers emissions, traffic, and parking demand while promoting inclusivity and community relationships. For underserved rural areas, transport on demand (ToD) offers tailored, affordable solutions that increase accessibility for disadvantaged groups. These modes cater to a wide range of user needs, but they depend on platforms and infrastructure to function smoothly.

Mobility infrastructure forms the backbone of transportation systems, enabling the smooth flow of people and goods. Bus terminals, subway stations, bike lanes, and mobility hubs are examples of elements that offer the physical foundation for integrating different modes of transportation. Investments in infrastructure increase transportation effectiveness, lessen traffic, and cut pollutants. For example, park-and-ride lots allow vehicles to switch to public transportation, and mobility hubs consolidate access to many modes of transportation. However, when combined with effective platforms and a variety of modes, infrastructure’s usefulness is increased.

The digital link between consumers and transportation providers is provided by mobility platforms. Platforms like Mobility as a Service (MaaS) facilitate multimodality and lessen dependency on private automobiles by streamlining planning, booking, and payment processes. In rural locations, on-demand platforms improve accessibility by customizing services to meet specific needs, while shared mobility platforms save expenses and maximize resource use. These platforms’ capacity to provide thorough and dependable services depends on the availability of physical infrastructure and a variety of mobility options.

The way these categories interact is crucial. The safety and accessibility of mobility modes rely on infrastructure, whereas platforms integrate both modes and infrastructure to improve user comfort and system efficiency. An e-bike system, for instance, works best when it has dedicated bike lanes (infrastructure) and a booking portal that shows availability in real time (platform). A robust network of transit hubs and dependable platforms for scheduling and coordination are also necessary for ToD services. Understanding how infrastructure, platforms, and modes of transportation are interdependent allows rural communities to implement creative and flexible solutions. All of these components work together to form a framework for sustainable mobility that promotes social and economic advancement while addressing issues of accessibility, inclusion, and ecology.

In this study, we analyze practices from the interdependent categories of mobility modes, mobility infrastructure, and mobility platforms, highlighting their role in promoting inclusivity across social, economic, and physical dimensions. One notable example is the Cycling Without Age initiative in Denmark, which demonstrates how these solutions can foster community engagement and address diverse mobility needs. This initiative reduces social isolation by giving older persons access to free, inclusive transportation services that give them chances to engage with their communities. In addition to increasing mobility, this program promotes social interaction and intergenerational bonding, both of which are critical for the elderly’s overall well-being, by enabling volunteers to transport seniors on trishaw rides. Cycling Without Age’s quick worldwide adoption is proof of its success. With the initiative now implemented in more than 50 countries globally, its reach has expanded well beyond Denmark. It is already operating in 39 countries and plans to grow to 20 more countries on all six continents. The substantial need for creative, neighborhood-based solutions that combat social isolation and advance accessible, sustainable transportation is highlighted by this expansion. This program’s widespread success is indicative of a larger social need for mobility solutions that serve vulnerable groups, such as the elderly and those with little mobility options. These kinds of programs highlight that transportation is about more than just traveling from one place to another; it is also about promoting social inclusion, enhancing life quality, and promoting mental health. As a result, these programs are essential for creating harmonious communities and encouraging inclusive urban and rural settings.

Their applicability is further highlighted by taking into consideration the spatial conditions of the rural areas where these practices are employed. Two clear examples of how location-specific factors affect the implementation and success of inclusive mobility solutions like Cycling Without Age are the Danish municipalities of Kalundborg Municipality and Lemvig Town. Despite the differences in the two regions’ physical and social environments, both settings demonstrate how the initiative adjusts to local needs. The majority of Kalundborg’s population consists of young professionals employed in industry, logistics, or related services. Through the project, this demographic structure facilitates intergenerational interaction and builds relationships between senior citizens and younger employees. The program enhances social inclusion and demonstrates the community’s strong environmental consciousness by using volunteer drivers to give older residents free trishaw rides. Kalundborg’s dedication to sustainability and social welfare is further demonstrated by its emphasis on community participation and decision making. In contrast, Lemvig is well-known for emphasizing renewable energy, especially wind energy, which fits with its geographic setting and instills a strong sense of environmental responsibility in its citizens. This awareness also extends to the Cycling Without Age campaign, which promotes social inclusion and lessens reliance on cars through sustainable transportation options. The town’s small size, rustic charm, and tight-knit community make it the perfect place for trishaw rides, which let senior citizens get back in touch with their surroundings. Strong ties between generations within the community also help the Lemvig initiative, which supports its objectives of improving environmental and social sustainability. Instead of contrasting, Kalundborg and Lemvig show how the same initiative can be tailored to different local contexts in complementary ways, highlighting its adaptability and wide range of applications.

The on-demand and shared mobility services in Scotland’s Badenoch and Strathspey region are another example examined in this study. This initiative’s all-encompassing approach to affordability and accessibility makes it a great illustration of inclusive mobility. Using wheelchair-accessible cars is one of its most notable aspects, guaranteeing that people with impairments can travel without any obstacles. This emphasis on accessibility promotes engagement by allowing people who might otherwise find it difficult to use traditional transportation systems to fully participate in their community. Volunteer community drivers run the service, which is essential to its continuous functioning. Because of this involvement, the community is actively involved in maintaining the solution rather than merely using it passively. Additionally, by using a Section 22 bus permit, the initiative encourages economic inclusion. In the UK, only non-profit organizations are eligible for this authorization, which enables them to offer community-focused public transportation services. Section 22 permits are exceptional because they enable non-profit organizations to operate public scheduled routes, particularly in places that are underserved by conventional public transportation operators. The main objective of these services is to improve accessibility and social welfare, not to make money, even if they may collect fees to cover operating expenses. Since 1999, the service has been operating continuously, consistently addressing the demands of the community, demonstrating its effectiveness and success. This sustained dedication demonstrates not only its dependability but also its noteworthy benefits to the area.

Since the population density in Badenoch and Strathspey is only 5.4 persons per square kilometer, the community transport system is especially practical for places with low population densities and sparse populations. Other modes of transportation are difficult to use because of the severe weather and difficult terrain, which is why this service works so well. It provides voluntary services and organized door-to-door transportation, and it runs on a demand-responsive basis. This strategy guarantees that despite the difficult geographic and climatic conditions of the area, individuals, especially those living in distant areas, have access to dependable transportation.

Reusing existing resources and infrastructure, the Old Rail Trail’s transformation into a bike path in Westmeath County, Ireland, is the third scenario examined in this study. This project is a prime example of how reusing outdated infrastructure can be a model for sustainable, inclusive growth. The Old Rail Trail, which runs 43 km from Athlone to Mullingar, has been converted into a car-free, accessible path that is suitable for persons of all ages and skill levels. The greenway’s relatively level terrain and mild gradients make it perfect for children, the elderly, and first-time cyclists alike, guaranteeing that everyone can take in the splendor of the Irish countryside regardless of experience or level of fitness. In addition to being accessible, the Old Rail Trail encourages social inclusion by bringing communities together along its path and involving the community through heritage structures. In addition to conserving cultural property, the project promotes local involvement and strengthens ties between locals and tourists by repurposing historic features along the trail. The path offers places where tourists can interact with local history and tradition, connecting important cultural sites including Athlone Castle and Dún na Sí Amenity & Tradition Park. It also offers important access points close to minor towns and villages, which boost local economies by attracting both residents and visitors. This greenway supports physical well-being, social connection, and economic vitality by connecting people with the environment, culture, and one another. It is more than just a bike route. The trail’s conversion of the former railway into a greenway serves as an example of how inclusive infrastructure can revitalize rural communities and guarantee that all people, from seniors to students, can use and profit from these common areas.