Abstract

This study investigates the complex relationship between the performance of logistics and Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) performance, drawing upon the multi-methodological framework of combining econometrics with state-of-the-art machine learning approaches. Employing Instrumental Variable (IV) Panel data regressions, viz., 2SLS and G2SLS, with data from a balanced panel of 163 countries covering the period from 2007 to 2023, the research thoroughly investigates how the performance of the Logistics Performance Index (LPI) is correlated with a variety of ESG indicators. To enrich the analysis, machine learning models—models based upon regression, viz., Random Forest, k-Nearest Neighbors, Support Vector Machines, Boosting Regression, Decision Tree Regression, and Linear Regressions, and clustering, viz., Density-Based, Neighborhood-Based, and Hierarchical clustering, Fuzzy c-Means, Model-Based, and Random Forest—were applied to uncover unknown structures and predict the behavior of LPI. Empirical evidence suggests that higher improvements in the performance of logistics are systematically correlated with nascent developments in all three dimensions of the environment (E), social (S), and governance (G). The evidence from econometrics suggests that higher LPI goes with environmental trade-offs such as higher emissions of greenhouse gases but cleaner air and usage of resources. On the S dimension, better performance in terms of logistics is correlated with better education performance and reducing child labor, but also demonstrates potential problems such as social imbalances. For G, better governance of logistics goes with better governance, voice and public participation, science productivity, and rule of law. Through both regression and cluster methods, each of the respective parts of ESG were analyzed in isolation, allowing us to study in-depth how the infrastructure of logistics is interacting with sustainability research goals. Overall, the study emphasizes that while modernization is facilitated by the performance of the infrastructure of logistics, this must go hand in hand with policy intervention to make it socially inclusive, environmentally friendly, and institutionally robust.

Keywords:

logistics performance index (LPI); environmental social and governance (ESG) indicators; panel data analysis; instrumental variables (IV) approach; sustainable economic development JEL Classification:

C33; F14; O18; Q56; M14

1. Introduction

In the globalized world of today, logistics systems’ productivity and resilience are essential drivers of competitiveness at the national level as well as of economic development and sustainability. The empirical organization of supply chains, developments in technology and global trade intensification have brought the performance of logistics to the forefront of both economic policy and corporate decision-making. In parallel to these developments has been the rise of the Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) paradigm as the leading framework used to evaluate sustainable economic performance, transcending conventional financial measurements to consider broader societal and environmental consequences [1,2].

Justification for the study. Despite the increasing importance of both the logistics performance perspective and the environmental, social, and governance (ESG) framework in the design of sustainable economic systems, the intersection between the two areas remains largely [3,4]. Currently, existing literature focuses predominantly on logistics performance as economic infrastructure, with most economic studies being carried out on a firm level, whereas, conversely, most existing studies on ESG frameworks focus mostly on a firm level paradigm, thereby largely ignoring their systemic dynamics within the country’s economic infrastructure. Currently, this systemic divide also leaves a huge knowledge gap, particularly with increasing recognition being accorded to the roles of logistics systems, as either facilitators or barriers, within environmental sustainability, as well as social well-being, and within governance dynamics [3]. Knowledge within this intersection is also highly required, particularly since logistics infrastructure designs significantly impact issues such as energy consumption, carbon emissions, resource use efficiency, working conditions, inclusive supply chains, and transparency in governance [4]. In addition, most global commitments, such as the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, significantly depend on the assurance of sustainable logistics systems, so empirical studies within this field, particularly within the intersection of systemic dynamics within logistics infrastructure design, within ESG frameworks within different countries, remain largely uncharted.

In the midst of these twin evolutions, a recurring and relatively unexamined question sits at its core:

- How do the interactions between the quality of logistics performance and each of the ESG pillars vary by country?

In contrast to the expanding real-world applicability of both ESG and logistics globally, academic work connecting the two is relatively rare. Most research on the Logistics Performance Index (LPI) targets economic metrics like trade levels, industrial competitiveness, and infrastructure quality [4], whereas ESG scholarship is typically centered around firm-level sustainability, ethical investment practices, and policy at a high level [5]. Consequently, our knowledge base is missing a systematic exploration of how logistics capabilities impact environmental sustainability, social fairness, and governance quality at the country level. That is a stark deficiency, given how essential sustainable logistics has become to attainment of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) [1]. This study has as its objective bridging that gap through a data-driven examination of how disaggregated ESG indicator variables correlate with logistics performance. In contrast to research using composite ESG indices, however, the research takes a disaggregated framework and looks at how infrastructure and efficiency in operations independently impact environmental (E), social (S), and governance (G) dimensions [2]. The research question is simple but fundamental:

- Does better logistics performance systematically have a positive impact on ESG results—and if so by which mechanisms?

This research advances the frontier of merging sustainable development and logistics research by offering practical lessons for both governments and MNCs. The key strength of this research is that it employs multiple methods, combining econometric analysis with ML. Endogeneity in this research has been controlled using instrumental-variable panel-data regression techniques, namely 2SLS and G2SLS, on a balanced panel of 163 countries from 2007 to 2023. This tackles endogeneity by improving the accuracy of results by mitigating the challenges posed by unobserved variables and reverse causality. To complement the econometric model, this research applies both supervised machine learning algorithms (Random Forests, k-Nearest Neighbors, Support Vector Machines) and unsupervised clustering algorithms (Density-Based, Fuzzy C-Means, Hierarchical, Model-Based, Neighborhood Clusters). This dual modeling approach not only provides robustness testing rigor but also identifies nonlinear behaviors and hidden patterns that are not accounted for or apparent in traditional statistical modeling. The ever-deepening integration of ML applications in the sustainability literature has led to greater predictive precision and the detection of patterns in high-dimensional data [6,7]. The dual-methodology approach thus strengthens internal validity and enhances generalizability, in line with prevailing research perspectives that intertwine ML and econometric analysis in the realm of ESG studies [8]. An important aspect of the analysis involves using ESG factors decomposed across the environmental, social, and governance pillars, rather than considering overall ESG scores, to identify the individual relationships of each factor with the Logistics Performance Index (LPI). Environmental factors are measured based on pressures exerted by emissions, air pollution, and land use; social factors are measured based on factors such as education access, service delivery, income levels, and child labor; and governance factors are measured based on the rule of law, regulatory quality, and innovation. This type of analysis has not been carried out in the literature with the depth and rigor reported here [6,7]. The conclusive evidence indicates that the ESG and logistics nexus involves various aspects of LPI improvements, including significant positive outcomes and challenges in environmental sustainability, tangible social impacts, applicable risks, and significant improvements in governance. However, effective logistics may exacerbate environmental or social inequalities in the absence of strengthened regulatory protection. Descriptive observations from all the collective data confirm the imperative of congruent policies that align with the evolution of logistics and the universal principles of ESG goals.

Study purpose. This research aims to develop a paradigm that establishes empirical links between logistics performance metrics and the Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) aspects of Sustainable Development. Recent studies indicate that national logistics performance closely correlates with both social and environmental aspects [3]. Although the importance of the world’s logistics capabilities as basic determinants of economic competitiveness, trade efficiency, and development is well-appreciated, their relationship with Sustainable Development remains uncharted. There still remains a chasm in knowledge regarding the independent and cumulative roles of different logistics capabilities, particularly with regard to their effects on ESG metrics, given recent debates stratified by their effects on Sustainable Development. Studies on the effects of logistics performance on sustainability suggest that the G20 nations’ sustainability levels remain largely driven by their logistics performance, underscoring the importance of joint policy formulation [9]. This assumption’s importance lies in its effort to bridge this chasm by exploring determinants of ESG, along with the interaction between logistical efficiency and ESG dimensions, as defined in the existing literature. Empirical studies suggest that ESG practices in logistics, environmental compliance, social responsibility, and corporate governance exert independent as well as cumulative effects at the firm and macroeconomic levels [4]. Similarly, improvements in ESG capabilities, particularly as applicable to Small, Medium, and Large Enterprises, remain identified as an effective approach for sustainable and human-oriented practices [2]. However, the use of digital technologies, along with Industry 4.0 technologies, in logistics remains effective in integrating urban and corporate logistics strategies with ESG dimensions [10]. Therefore, within this background, this proposal’s subsequent analysis shall conduct a rigorous, sequential, bi-variate analysis of the Logistics Performance Index’s variables, prepared through thorough verification against detailed ESG variables, within the realm of its governance units spanning 2007–2023, totaling 163 governance units. Specifically, the analysis will focus on: (1) the correspondence between improved logistics capabilities and environmental stress, as opposed to environmental efficiency (e.g., customs clearance and lead-time reliability); (2) the social determinants as antecedents of logistics capabilities, shedding light on education, working conditions, demographics, and accessibility issues (e.g., ease of arranging shipments and customer satisfaction); (3) the governance quality, with a focus on its constitutive aspects: enabling institutions, regulatory systems, scientific productivity, as well as enabling governance structures (e.g., tracking and tracing capabilities and supply chain transparency). Using instrumental variables panel regression analyses and sophisticated machine learning models, this analysis will examine the two-way relationships between logistics capabilities and sustainable development.

Study Purpose and Research Themes. This proposed research aims to develop a theoretical framework that explains the relationship between Logistics Capabilities Metrics and Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) factors within Sustainable Development. The emerging literature shows a strong correlation between national logistics capabilities metrics and social or environmental issues [3]. Although the correlation between global logistics capabilities metrics and Sustainable Development remains uncharted, the general implication is that logistics capabilities significantly affect economic competitiveness, trade, and Sustainable Development. However, there seems to be limited insight into the independent or cumulative aspects of such logistics capabilities, particularly as a Sustainable Development factor. With regard to the literature established in the precedent of existing literature on logistics capabilities metrics/sustainability, more recent literature asserts that the Sustainability path within G20 nations is largely dependent on their capabilities, thus establishing that policy as collectively decisive [9]. By implication, that this literature fills a much-needed aspect, within existing Sustainable literature, that might explore this correlation between determinants of ESG factors, through measures of Logistics Efficiency established within pertinent literature, as emergent empirical notions demonstrate that ESG Logistics, defined through necessary environmental, social, or governance protocols, remain collectively independent, with negative, positive, notions within the macroeconomic paradigm [4]. Improving ESG Capabilities, particularly within the realm of small-to-large-scale businesses, demonstrates a push towards more Sustainable, People-centric paradigms [2]. Simultaneously, technology such as Industry 4.0 remains effective within the strategic paradigm of transforming urban, corporate, or logistics infrastructure, as defined through the resultant ESG paradigm [10]. With this background, the proposed analysis will conduct a meticulous, sequential, multivariate analysis of Logistics Performance Index variables, cross-checked against more refined ESG variables, focusing on a dataset comprising 163 governance units for the years 2007–2023. To increase the validity of the results, posterior predictive checks and robustness analyses will be used. This will allow for issues of model specification parsimony and sensitivity issues that might qualify the conclusions. More specifically, this analysis will focus on the interaction between improved logistics capabilities under environmental stress and environmental efficiency, as captured by variables such as customs simplicity, customs clearance, and lead time reliability. Social-influence variables, such as education, working conditions, demographics, accessibility, ease of arranging shipments, and customer satisfaction, will be considered antecedents of logistics capabilities. More specifically, the knowledge generated by this analysis of education and working conditions might serve as a basis for formulating personnel management policies through train-and-develop programs or by establishing benchmark standards for laboratory practices, thus further reinforcing the social component of ESG. Governance quality will be analyzed through its constituent parts, including governance structures, governance frameworks, scientific productivity, and facilitative governance frameworks, which comprise tracking and tracing capabilities and transparency. By combining instrumental-variable panel regression with more sophisticated machine-learning analytics, this analysis will explore the two-way interaction between logistics capabilities and sustainable development.

Study Hypotheses. With the aforementioned research questions as the background, this study formulates three inclusive hypotheses that provide direction for the analysis, thereby aligning the conceptual framework with the methodology. These hypotheses assume that the correlation between logistics performance metrics and sustainability outcomes is complex, interacting with environmental, social, and governance factors within the ESG framework [11].

H1.

Logistics performance shows a systematic relationship with mixed environmental effects, reflecting trade-offs between development and the environment. This hypothesis argues that improvements in logistics infrastructure can minimize resource use and some types of pollutants, but simultaneously increase other pollutants, such as GHG emissions. The existing literature suggests that ESG innovations focused on logistics and transportation can improve environmental efficiency while addressing new environmental pressures, such as increased energy use and GHG emissions [1,12]. Using disaggregated measures of environmental effects, such as air, GHG emissions, heat stress, and land use, this research will examine the impact of environmental stresses and efficiencies as forces behind changes in the Logistics Performance Index [11].

H2.

Socio-economic variables significantly and diversely affect logistics performance. This hypothesis assesses the influence of education, basic service accessibility, demographics, working conditions, and income distribution on logistics performance. Evidence confirms that socio-economic variables, such as employee education, fair working conditions, and service accessibility, affect logistics efficiency [1]. Social determinants, such as education, access to basic services, demographics, working conditions, and income distribution, create inequality in human capital, working conditions, or both, affecting the efficiency of global logistics.

H3.

Improving governance quality promotes a positive outcome on logistics performance. This hypothesis assumes that a high-quality institution, with attributes of proper regulation, the rule of law, efficient administration, and scientific strength, fosters a supportive environment that facilitates the establishment of a sound, modern, and trustworthy logistics infrastructure. Empirical evidence shows that sound governance principles or regulations can enhance ESG practices and sustainable development across nations [12,13]. These hypotheses collectively form the focal point of this analysis, through which the rest of this report will explore the relationships that exist between logistical performance and the environmental, social, and governance aspects of sustainable development.

The research is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews the existing literature, identifying the main conceptual frameworks and empirical findings to date. Section 3 presents the data sources, sample characteristics, and the econometric and machine learning methodologies employed. Section 4, Section 5 and Section 6 are dedicated, respectively, to the analysis of the relationships between LPI and the Environmental, Social, and Governance components, detailing both the regression-based and clustering-based results. Section 7 concludes with a discussion of policy implications, limitations, and directions for future research. Furthermore, Appendix A presents the hyperparameter settings of the regression algorithms, Appendix B presents the hyperparameter settings of the clustering algorithms, Appendix C presents the summary statistics of the environmental (E) indicators, Appendix D presents the summary statistics of the social (S) indicators, and Appendix E presents the summary statistics of the governance (G) indicators.

2. Literature Review

The existing literature presents informed but incomplete insights into the interrelation between ESG outcomes and logistic performance tending to lack the level of systemic integration and granularity desired by this study. The research by [4,5] has as its main objective assessing the financial impact of adopting ESG in the case of logistic firms but does not reveal its investigation to wider systemic interactions unfolding from country-wide metrics such as the Logistics Performance Index (LPI). While suggesting that the impact of ESG schemes is mediated by logistic performance and economic results, ref. [14] does fail to differentiate the ESG pillars and does not treat direct causality, a concern treated by this research. The issue of ESG challenges and opportunities in the post-COVID-19 context is broached by [2,15], albeit in a way failing to integrate results systematically to transportation efficiency metrics such as the LPI. In the same spirit, research by [1,16] analyzes ESG’s impact on competitiveness and on stock performance but falls short of considering logistic infrastructure as country-wide driver of sustainability. Refs. [10,17] deal with smart and digitalized logistic as ESG enablers and participate in thematic add-ons short of adopting serious quantitative research practices like in the research presented here. The effect on firm performance of green logistic action is demonstrated by [18,19,20], the latter focused on the dimension of ESG transparency but both are subject to micro perspectives. The use of technology is analyzed by [21,22], and [23] but short of structural embedding of country-wide logistic performance in ESG effect. The research by [24] generalizes ESG discourse to maritime and seaport logistic industries but fails to systematically analyze environmental, social, and governance dimensions separately vis-à-vis the LPI as it does in this study.

Refs. [25,26] acknowledge transport and logistic firms to be influenced by ESG but reduce ESG to aggregate scores and fail to identify pillar-specific effects as identified here. Refs. [27,28] discuss communication and perception dimensions of ESG in the logistic sector but fail to attain econometric robustness. Refs. [29,30] discuss impact of ESG on supply chains but by a generalized application by qualitative methods and non-dynamic panel data methods or by using machine learning algorithms. Refs. [31,32] include governance variables like board diversity but fail to capture how the impact of logistic infrastructure performance on ESG is systematically captured. Refs. [33,34,35], and associate ESG and operation efficiency and productivity in the supply chain but to firm-specific or industry-specific studies and to system levels in countries by using LPI. Ref. [36] associate climate policy uncertainty and logistic stock returns and ESG scores but fail to include pillar disaggregation. Refs. [37,38] document sustainable optimization of the logistic industry but fail to document how optimization practices are associated with larger ESG systems in countries. Ref. [39] calculate competitiveness on efficiency of the logistic sector but their work does not systematically rule out environmental and social spillovers identified here. Ref. [40] discuss digitization and benefits to ESG and [41] discuss sustainable infrastructure but both fail to utilize instrumental variable panel data methods or machine learning regressions.

Research by [42,43] focuses on sustainability and governance in logistics companies but lacks generalizability at a country level. Refs. [44,45] design ESG assessment models but work primarily at conceptual or firm levels and lack the cross-country and long-dimensioned data included in this study. Refs. [46,47] connect ESG to credit risk at the firm level but do not conceptualize the firm as a fundamental unit of analysis as they do so. Refs. [48,49] acknowledge the role supply chain digitalization plays in improving ESG but do not systematically tie it to LPI measurements. Refs. [50,51] emphasize the predictive ability of sustainability initiatives and ESG outcomes but fail to discuss drivers exclusive to the logistics sector at the country level. Refs. [52,53] equate ESG with efficiency at the terminals and ports and get close to LPI issues but keep to a sectorial scope. Refs. [54,55] discuss procurement benefits and circular economy models but fail to consider logistics performance as a systemic driver. Together, this study is the first to combine both econometric and machine learning approaches to reveal LPI to be a first-order determinant of ESG outcomes and not a secondary measure and to do so across countries, filling gaps in existing research.

3. Data and Methodology

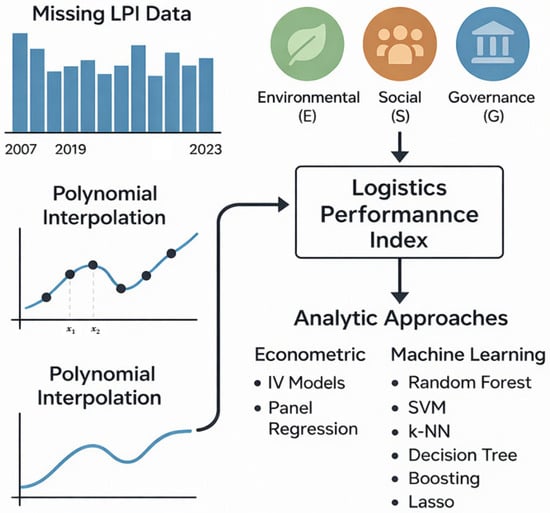

One of the main methodological difficulties faced in the current research stems from the non-existence of a continuous historical time series of the Logistics Performance Index (LPI). The available LPI data intermittently between the period of 2007–2023 pose a number of missing values by country and year and thereby complicate the creation of a full and balanced panel dataset adequate to perform rigorous econometric and machine learning analysis. In a bid to overcome this problem and maintain the consistency and integrity of the data’s longitudinal form, a polynomial-regression-based interpolation scheme was utilized. Polynomial fitting was used to fill in missing values on a country-wise basis to rebuild realistic historical traces of the LPI values and avoid risks of injecting spurious biases using simpler linear interpolation methods. The methodology is informed by existing research suggesting the benefits of using imputation as well as advanced interpolation methods in LPI research ranging from genetic algorithm-based weights to imputation methods using regression [56]. The second core analytic decision concerns ESG disaggregation. In contrast to keeping ESG as a combined or aggregate indicator, the research systematically breaks up the model into its three pillars—Environmental (E), Social (S), and Governance (G)—and studies the interrelation of LPI across each of these dimensions in turn. The pillar-wise design allows a finer and more detailed understanding of how the interactions between logistics performance and sustainability outcomes unfold than has been the case with prior research which tended to work with ESG as a uniform block. The research design is aligned with contemporary research underlining the different and diverging influence of a particular ESG dimension on firm and sector performance [4,57]. In keeping with the research question’s adverseness to simplicity, the analytic design follows both conventional econometric and sophisticated ML approaches. The econometric analysis was conducted by using Instrumental Variables (IV) panel regressions comprising both Two-Stage Least Squares (2SLS) and Generalized Two-Stage Least Squares (G2SLS) models to rigorously contend with endogeneity issues and ascertain causal interpretation of the estimated coefficients. Complementarily to the above, machine learning methodologies were implemented in both the regression and clustering tasks—utilizing Random Forest, k-Nearest Neighbors, Support Vector Machines, Decision Tree Regression, Boosting Regression, and Lasso in the case of the former and Density-Based Clustering, Fuzzy c-Means, Model-Based Clustering, Neighborhood Clustering, Random Forest Clustering, and Hierarchical Clustering in the case of the latter. The interplay between the econometric and machine learning models facilitates both the verification of outcomes by means of different methodological perspectives and the determination of nonlinear and latent patterns likely to pass under the radar of conventional regression analysis. These combined methodological options respond to the requirements of data constraints but also intensify the robustness, exhaustiveness, and novelty of the research’s empirical contribution to the extant literature on the topic of logistic performance and sustainable development (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Overview of the Research Design and Analytical Framework. Note: the diagram illustrates the full research workflow, including the reconstruction of missing LPI values through polynomial interpolation, the integration of Environmental, Social, and Governance indicators, and the application of both econometric and machine learning approaches for the analysis.

Study model. In this case, the proposed research will use a multi-method design to investigate the relationship between logistics performance and the different dimensions of Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG). In this design, the Logistics Performance Index (LPI) will be the dependent variable, with the environmental, social, and governance dimensions as determinants. Such designs have been used previously in other studies that investigated the effects of different dimensions of ESG issues on the quality of institutions and the economic aspects of different countries [58]. To specify the nature of this link, the analysis resorts to Instrumental Variable (IV) panel fixed-effect regression models, namely Two-Stage Least Squares (2SLS) and generalized (2SLS). These econometric models address endogeneity, missing variables, and reverse causality. Finally, the models assess the specific drivers of environmental, social, and governance variables on logistics performance across 163 countries spanning 2007–2023. Previous studies have shown that IV models, as well as panel regression models, may effectively examine the links between logistics performance, innovation, and environmental issues [59,60]. Apart from this established framework of causality, the study uses more complex machine learning models to examine nonlinear correlations, thereby improving predictability and the ability to identify hidden dynamics across nations. Regression models (Random Forest, Support Vector Machines, k-Nearest Neighbors, Decision Trees, Boosting, Lasso, or Elastic Net) will be used for the analysis of accuracy, while the application of clustering models (DBSCAN, Fuzzy C-Means, Hierarchical, Model-based, Neighborhood-based, or Random Forest) will identify structural variations, more specifically within models linked with different nations. Applying such models aligns with recent improvements in predictive analytics, where machine learning algorithms were rigorously tested for feature selection and model accuracy assessment in logistics models. By embracing this convergence, analyses that treat ESG variables as discrete will seek to identify their net impact on the logistics industry as a whole, delivering valuable insights into any correlations within the realm of sustainability studies. These analyses will also position the logistics industry as a key environmental agent, demonstrating the positive impact that increased adoption of best practices can have on minimizing resource use. Case analyses will also demonstrate the use of freight consolidation, routing, and other solutions that address industry improvement as a tool for environmental remediation, as defined by [59] and subsequent studies such as [60].

Study analysis. This empirical analysis combines econometric identification with predictions derived from machine learning models, focusing on the impact of environmental, social, and governance (ESG) factors on the logistics performance of 163 different nations from 2007 through 2023. Similar studies combining multiple models into a single methodology were recently used in tandem with other studies involving artificial intelligence models to achieve more realistic results through the intersection of economic models with AI models [61]. Using instrumental variables (IV) panel regression analysis, the empirical results show a twofold, double-edged, but mostly negative implication of environmental variables for every Logistics Performance Index (LPI). More specifically, greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, agricultural value added, air pollutants, and extensive agricultural use are positively or negatively associated with logistics efficiency. This illustrates that environmental and governance variables often have both positive and negative implications for economic performance, depending on the relevant environmental conditions and economic factors [62]. Specifically, variables such as water accessibility, sanitation facilities, aging, education, and increasing elementary education enrollment rates reflect modest negative adjustments, whereas child labor reflects higher LPI levels. However, income inequality has strong negative effects on logistics activity, suggesting that stronger social development, with reduced income inequality, facilitates efficient value chain management. By contrast, predictions from machine learning models indicate that IV estimates of environmental stress, education, and demographics remain applicable, valid, and accurate. Integration between the two models results in more robust models with enhanced predictability, a methodological improvement supported by previous studies on machine learning-based predictions of logistics performance. Clustering analyses identify distinct elements within each country, defined by attributes such as air pollutants, extreme temperatures, and agricultural intensity, and determine distinct loci for each country. Thus, the empirical results for this topic show that multifaceted logistics sustainability prevails, implying that the well-balanced evolution of logistics must address, alongside environmental enhancement, improved social conditions and proper governance [62].

Limitations. Across all analyses, the dataset includes 163 countries. Although such a large cross-country dataset helps derive corresponding cross-country correlations with relative ease, this inevitably affects the level of granularity available to inspect individual national settings. To address this tension, the necessity of accounting for national cross-country variability is carefully explained in this manuscript through complementary cross-country analysis strategies, including cluster and machine-learning algorithms.

4. Environmental Sustainability and Logistics Efficiency: A Multi-Method Analysis Using IV Regressions, Predictive Algorithms, and Clustering

This section examines the interplay between the Environmental (E) component of the ESG framework and the Logistics Performance Index (LPI) using a two-methodological framework involving Instrumental Variable (IV) panel models and machine learning (ML) models. IV models eliminate issues of endogeneity and enable causal inference of how environmental indicators such as PM2.5, nitrous oxide emissions, heat exposure levels, and agricultural land cover are determinative of logistics performance. This framework is a following of [63], in which they emphasize controlling for environmental-economic interactions when measuring LPI, and particular emphasis on the dimensions of green innovation, renewable energy, and global integration. ML models—such as used by [64] in environmental hazard predictions—are applied to best achieve predictive power and to compare the relative effect of environmental variables. The clustering methods following [65], who used functional regression-based clustering of air pollution data, identify latent country profiles through shared environmental-logistics patterns and add richness to the ensuing analysis.

4.1. Causal Estimation of Environmental Determinants of Logistics Performance Within the ESG Framework

This section investigates the impact of environmental and land use variables on the Logistics Performance Index (LPI) across 163 countries from 2007 to 2023. Using fixed-effects two-stage least squares (TSLS) and generalized two-stage least squares (G2SLS) models, the analysis addresses endogeneity by employing a broad set of instrumental variables. Key factors examined include nitrous oxide emissions, PM2.5 pollution, extreme heat exposure, agricultural land share, and agricultural value added. The results reveal that environmental degradation and land use dynamics significantly influence logistics performance, underscoring the need to integrate environmental considerations into logistics development strategies aligned with ESG objectives.

Specifically we have estimated the following model:

- (First Stage)

- (Second Stage)

- i = 163

- t = [2007; 2023]

The results are indicated in the following Table 1.

Table 1.

Environmental Stressors and Logistics Performance: An IV Panel Data Analysis.

This research focuses on the factors underlying the Logistics Performance Index (LPI) across 163 countries over 17 years, using panel data comprising 2771 observations. The research focuses on the significance of environmental factors, including nitrous oxide emissions, exposure to air pollution (PM2.5), exposure to extreme heat, and land use factors such as the share of agricultural land and the value added by agriculture. The conceptual approach uses the framework recently developed in the context of the relationship between environmental factors and logistics networks [59]. The issue of endogeneity is addressed using fixed-effect two-stage least squares (TSLS) and generalized two-stage least squares (G2SLS) with a large set of instruments based on living standards, health status, demographics, governance factors, education factors, and overall economic factors. This research follows the literature by emphasizing the importance of accounting for variations in LPI determinants across different locations [66] and for endogenous variables in cross-sectional analyses in the context of logistics research [67]. For both specifications, the results are significant and robust. All five endogenous variables are significant determinants of LPI; however, the relatively small values suggest that logistics performance depends on various factors not covered in this research, such as environmental and land use factors. Nitrous oxide release emerges as a significant positive determinant of LPI, indicating that improvements in logistics infrastructure often accompany the increase in industry and pollution levels in those regions; this agrees with other evidence in support of the idea that the increase in logistics infrastructure often conflicts with the increase in pollution levels in regions [68,69]. The exposure level of the population to air pollution shows a negative association with LPI levels, in line with other research in this context, suggesting that increased levels of air pollution exert negative pressure on workers’ productivity in industries and on transport infrastructure in regions [70]. The population exposure level in regions to extreme heat data (HI35) shows significant positive effects on LPI values. This indicates that technological adaptation in regions may accompany effective advanced infrastructure in the logistics sector in regions prone to high levels of temperature data. Agricultural land use shares exhibit negative significance in LPI values. This indicates that agrarian regions often possess ineffective infrastructure in the logistics sector, whereas data from overall value added in agriculture indicates significant positive significance in LPI values; this approaches research done in this context through support of research in support of commercialized regions through the increase in colder chains infrastructure in regions [71,72,73]. The collective data indicate complex conflicts between the expansion of infrastructure in the logistics sector and regions under environmental pressure. Although enhanced logistics improvements are linked to diversification and the commercialization of agriculture, they may also lead to environmental deterioration. The results highlight the need for a link between logistics enhancement and environmental preservation.

Causality. The fixed-effects two-stage least squares (TSLS) and generalized two-stage least squares (G2SLS) applications allow a causally robust interpretation of the correlation between environmental variables and logistics performance. Leveraging a dense set of instrumental variables that influence environmental and land use patterns but plausibly exogenous to the domain of logistics performance, the analysis manages to evade common issues of endogeneity like omitted variable bias and reverse causality. The methodology is aligned with recent empirical work which has utilized the TSLS and G2SLS framework to separate causal effects in the presence of complicated interdependencies and confounders, particularly in studies of environmental and economic performance [74]. Similarly, in environmental quality and green logistics as well, ref. [75] demonstrated how two-stage estimation methods are influential in capturing delicate interactions between logistics performance and sustainability outcomes across a variety of economies. Consequently, the positive effects of nitrous oxide emissions and agricultural value added and the negative effects of PM2.5 air pollution and agricultural share of land are causal effects and pure associations. The research is thus more policy-relevant because it means environmental quality and land management directly impact a country’s ability to perform logistics. The low R-squared values do however reveal that even though remarkable influence is exerted by these variables on logistics performance, they capture only a fraction of the complicated determinants driving it.

Impact of the results within the E-Environmental Component within the ESG model. Empirical evidence elucidates a two-side and multifaceted relationship between environmental consequences and the performance of logistics. While on the first side, improved LPI scores are typically associated with greenhouse emissions such as nitrous oxide evidencing the environmental impact of widespread transport, warehouse operation, and industrial production. This presents a time-tested trade-off in development-environment terms: more developed infrastructure of logistics produces a superior level of economic development but also accelerates environmental degradation if it is uncontrolled. More contemporary research has identified systems of logistics such as third-party and heavy goods-associated systems as prominent producers of emissions unless practices of sustainability are implemented [76]. Environmental degradation per se as well as air pollution (exposure to PM2.5) on the other hand negatively impinges on the efficiency and dependability of logistics. Pollution reduces productivity by labor, makes transport flows difficult and damages public health all of which impair the efficiency and dependability of logistics. Apart from environmental degradation per se, exposure to climate extremes such as hot days also underscores building climate-resililent systems of logistics. Adaptive practices such as green chains of supply, energy-efficient services and products as well as eco-friendly infrastructure are necessary to render logistics operations climate-resilent to climate risks. All of the above solutions are now increasingly implemented by models of logistics worldwide ranging from electric fleets and renewable sources to tracking emissions by blockchain in the supply chain [77]. The relationship between land use and logistics also confirms the role of the environment. Land economies with a high share of agricultural land have weaker performance of logistics while economies commercialized with sustainable land management are capable of developing stronger infrastructure of logistics. This is a part of a general transition towards a sustainable phase change in the development of logistics whereby firms are increasingly viewing green logistics as a source of competitive power to avoid the costs of emissions and to enhance resilience as opposed to a constraint [78]. Overall, incorporating strong environmental concerns into planning logic of logistics is now a requirement and not a choice but necessary to become competitive in the long term. Aligning LPI developments to Environmental pillar of ESG requires proactive investment in green logistics, regulatory transformation and sustainable innovation to ensure development of logistics complements and does not compromise global environmental goals.

4.2. Environmental Determinants of Logistics Efficiency: Evidence from Machine Learning Analysis Under ESG Standards

This section explores the application of various machine learning regression algorithms to predict the Logistics Performance Index (LPI) based on environmental and land use variables. Models such as Boosting Regression, Decision Tree Regression, k-Nearest Neighbors, Linear Regression, Random Forest, Lasso, and Support Vector Machine (SVM) are compared using standard performance metrics including MSE, RMSE, MAE, MAPE, and R2. The analysis identifies Random Forest Regression as the most robust model, offering the best trade-off between accuracy and generalizability. Further, variable importance measures from Random Forest highlight the critical role of environmental factors in shaping logistics performance across countries and over time (Table 2).

Table 2.

Comparative Performance of Machine Learning Models in Predicting Logistics Performance.

Comparing the results of different algorithms provides concrete evidence of the suitability of various predictive models for forecasting Logistics Performance Index (LPI) values. Among the various algorithms, such as Boosting Regression, Decision Tree Regression, k-Nearest Neighbors (k-NN), Linear Regression, Random Forest Regression, Lasso Regression, and Support Vector Machine (SVM), Random Forest Regression proves to be the most balanced or stable algorithm [79,80]. This algorithm not only provides the highest ‘R2’ of 0.29 but also proves to be the most effective model at explaining the difference in values (0.29), although the overall explained variability accounts for only 29 per cent. This high ‘R2’ value indicates greater adaptability to the nonlinearities prevalent in larger data samples that constitute the global research landscape in logistics [81]. Moreover, across various measures of prediction error, Random Forest Regression again proves more effective than other models. This algorithm yields values of 464.679 for mean squared error (MSE) and 21.556 for root mean squared error (RMSE), whereas Decision Tree Regression yields slightly lower values of 254.149 for MSE. However, this algorithm provides greater stability or resistance to overfitting and hence proves more effective in terms of generalizability or universal applicability [79]. Decision Tree Regression and k-NN Regression again provide slightly lower values in terms of mean absolute errors (MAE) but are otherwise are hampered by inherent drawbacks of high sensitivity towards noise and complexity arising out of depth in Decision Tree Regression [80], while k-NN Regression gets hampered by the hassles in scaling up and sparsity in data samples [81]. The data of SVM Regression again gets hampered by inconsistency in various parameters, such as high mean absolute percentage errors (MAPE) and lower values in terms of MSE and ‘R2’ measures due to appropriateness of choice of kernels in this context [81], although this again gets commonly exhibited in various other studies in comparison among various algorithms irrespective of parameters [81,82]. Linear Regression, Lasso Regression, and Boosting Regression again get completely hampered in terms of overall underperformances in various parameters due to domination by nonlinearities prevailing in the data samples in terms of interrelations of various environmental factors in constituting global governance parameters and various other economic factors in overall domains of the global arena in the realm of logistics [83].

Applying the Random Forest Regression we have the following results as showed in Table 3:

Table 3.

Variable Importance Metrics for Predicting Logistics Performance.

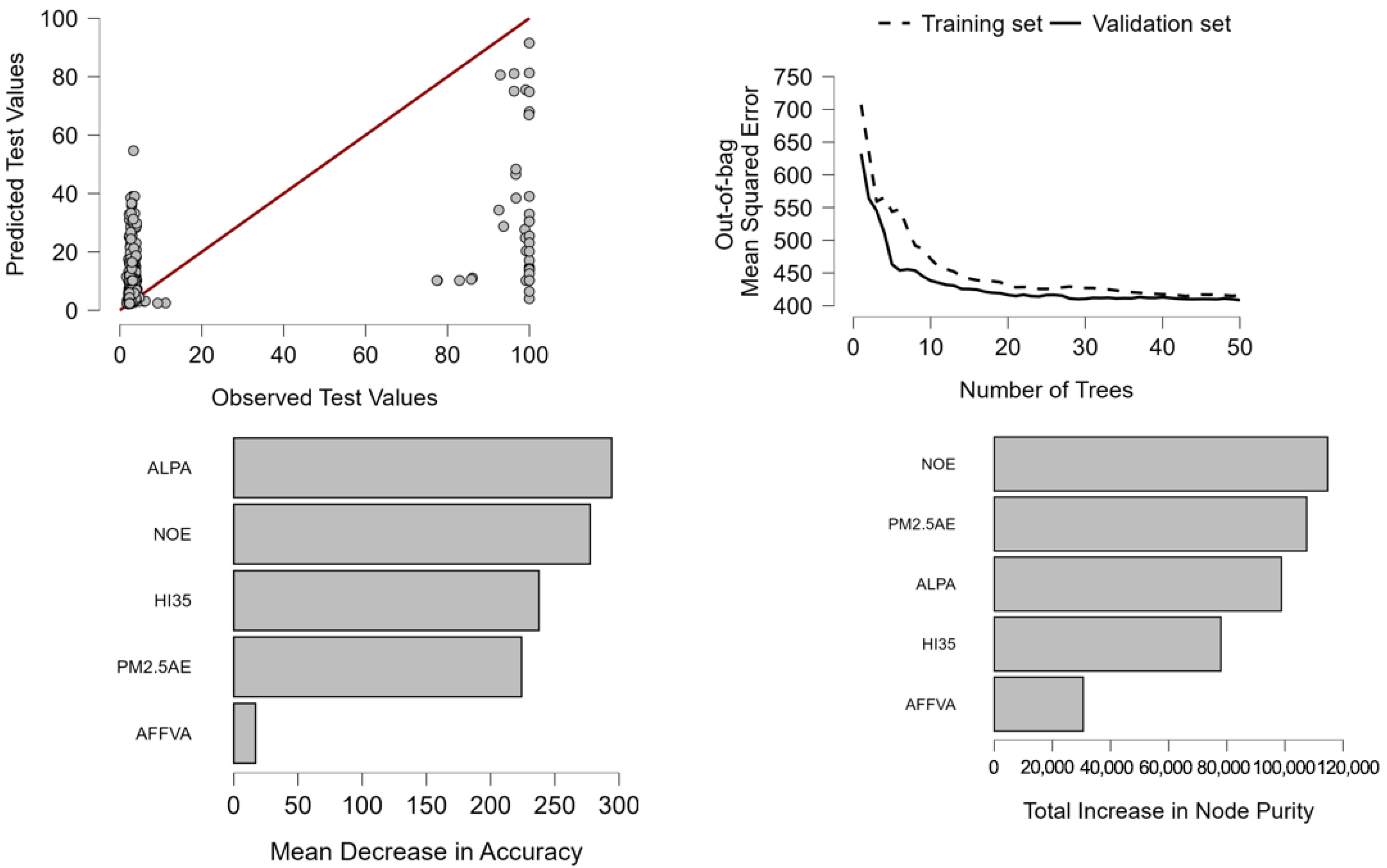

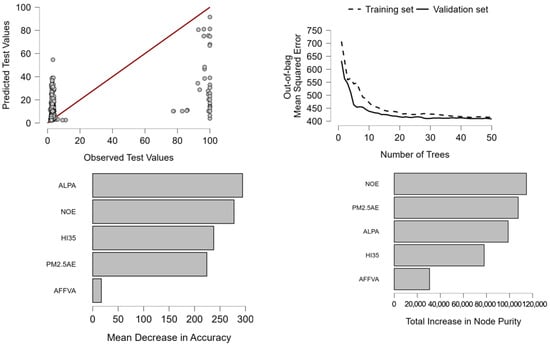

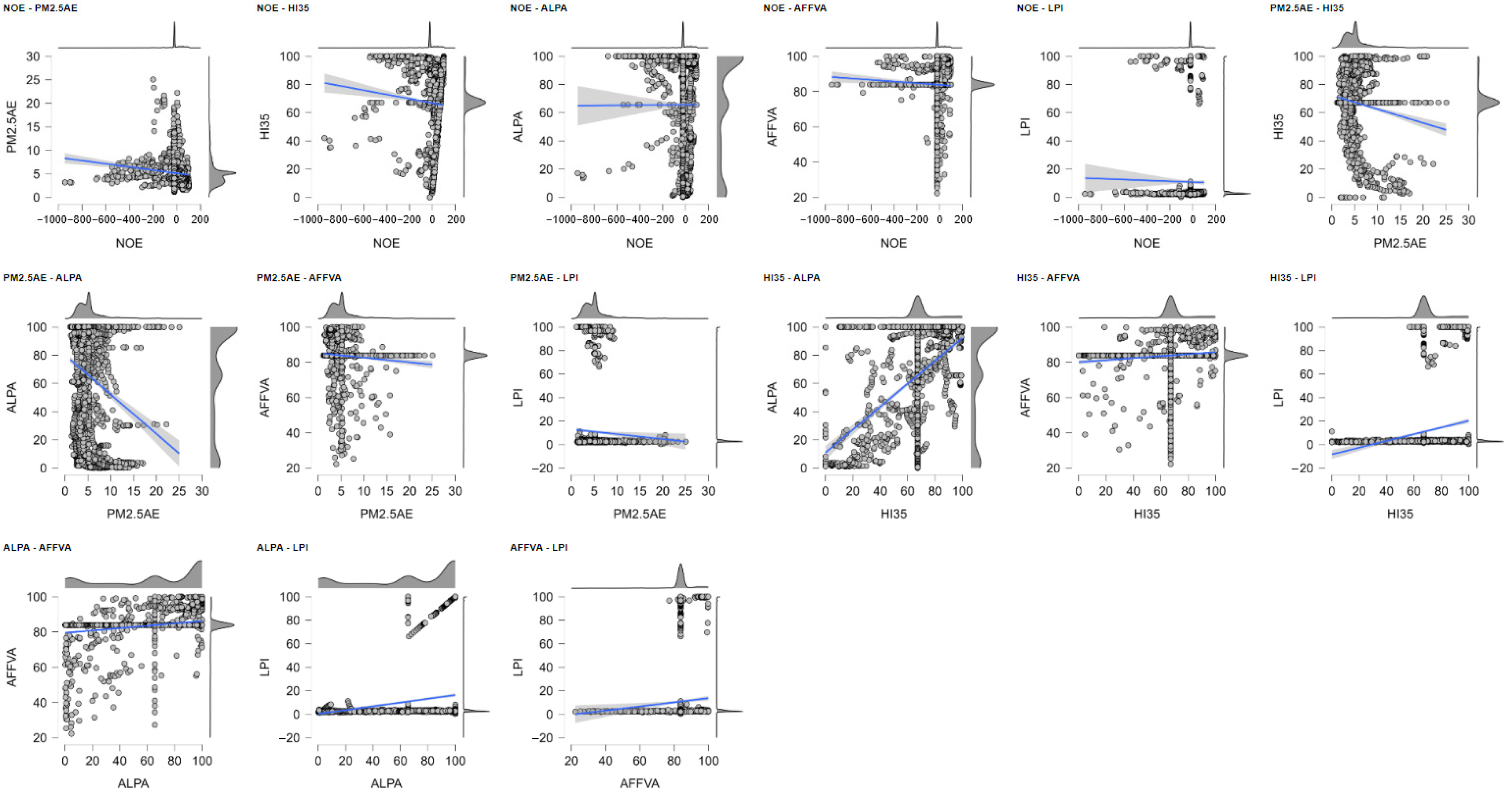

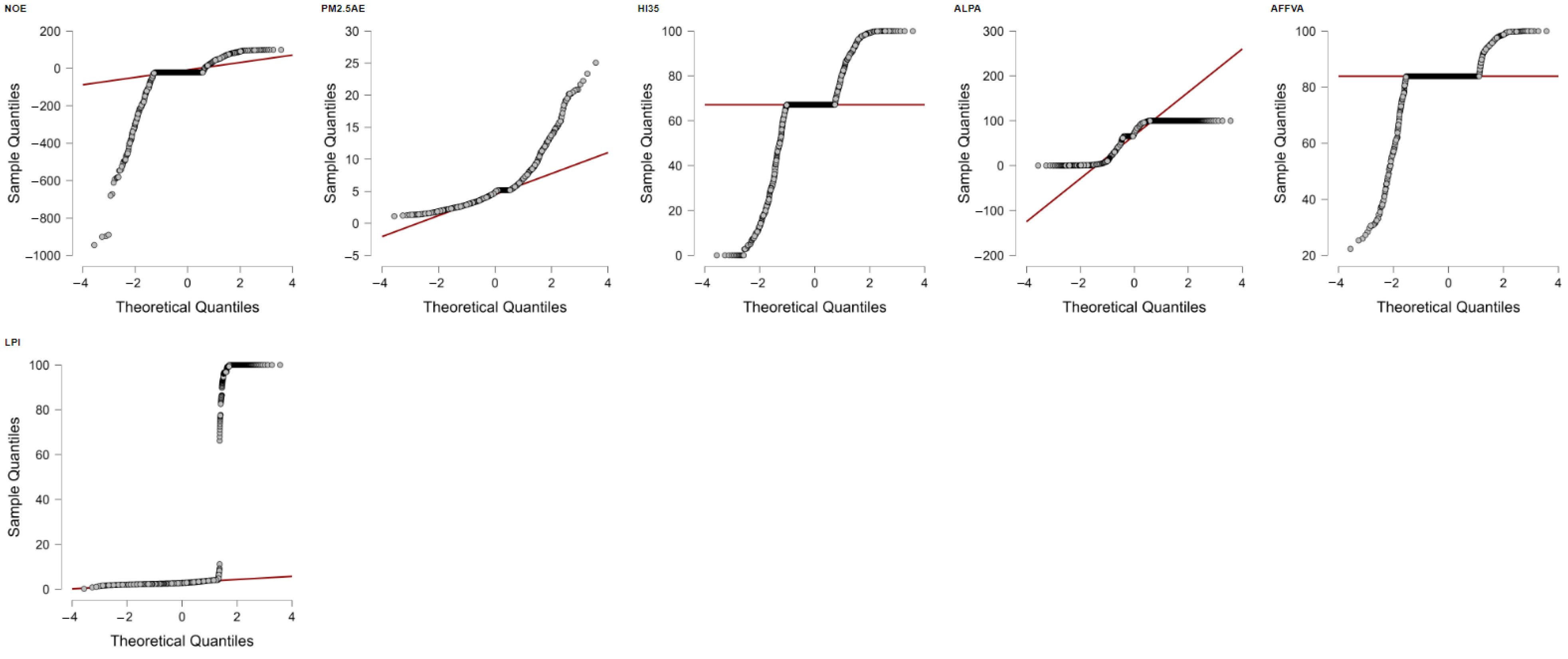

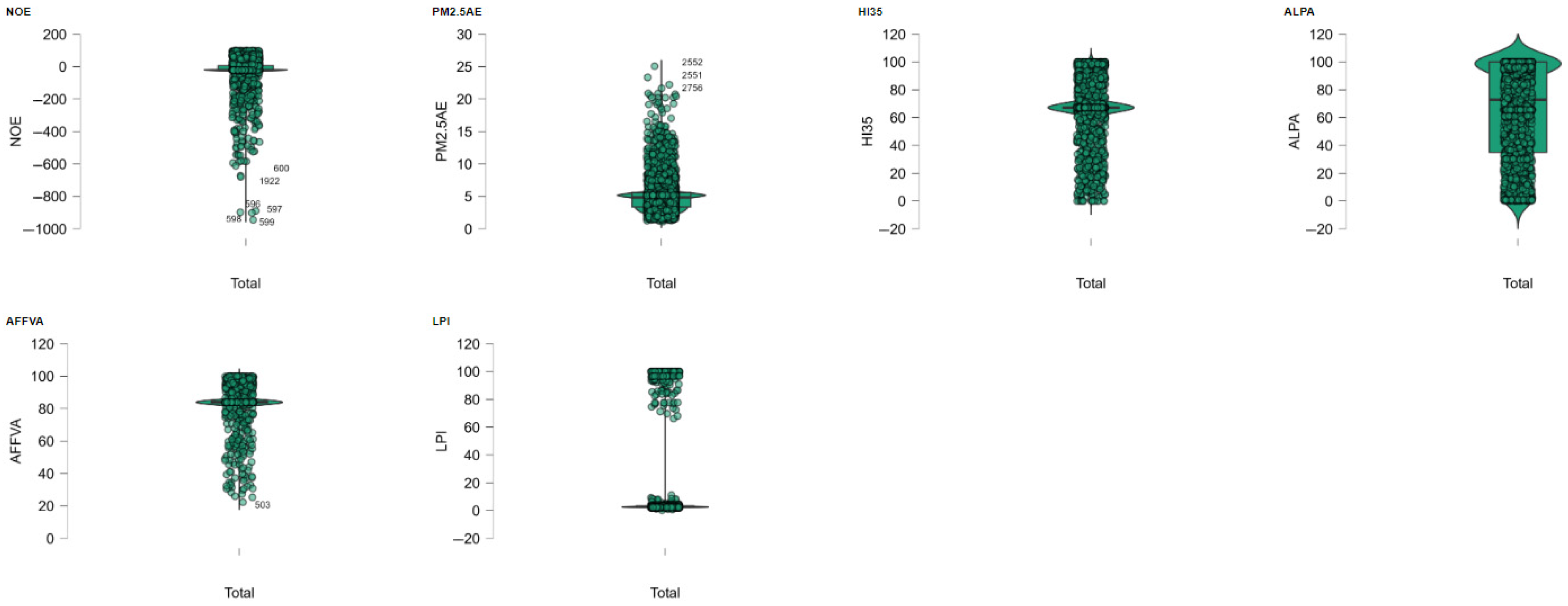

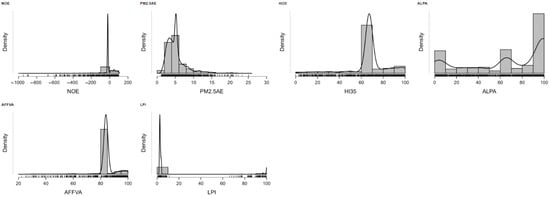

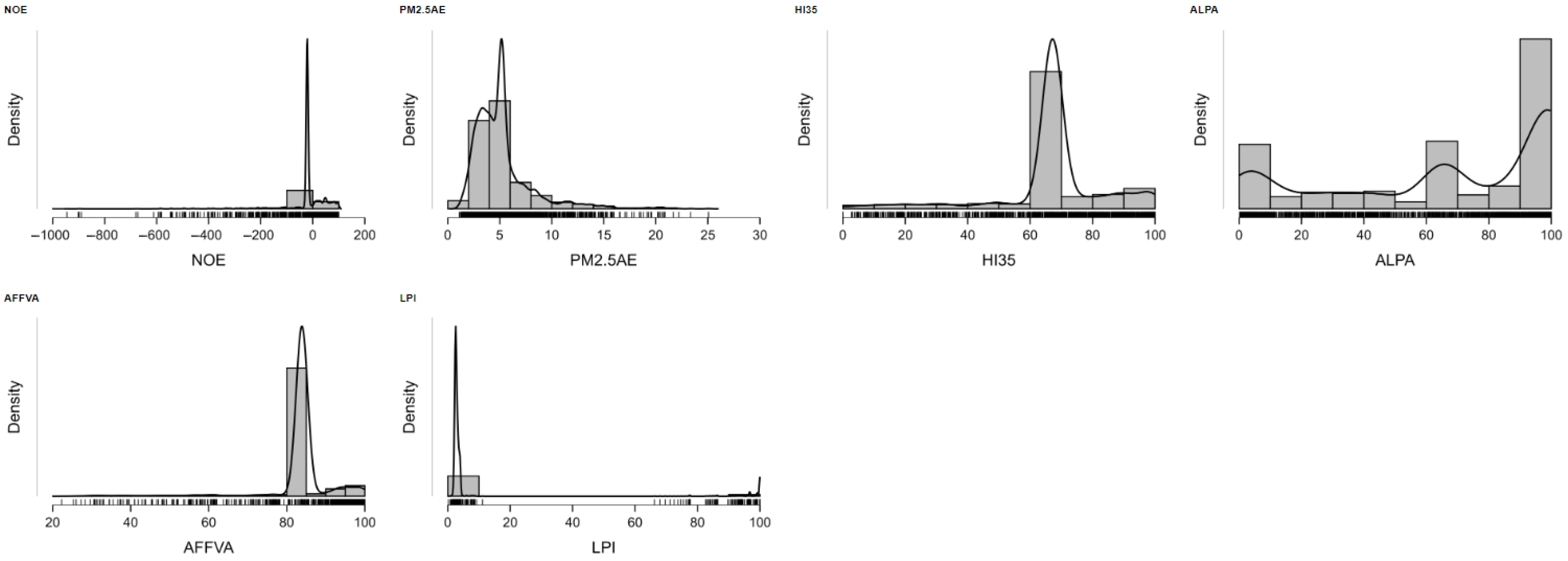

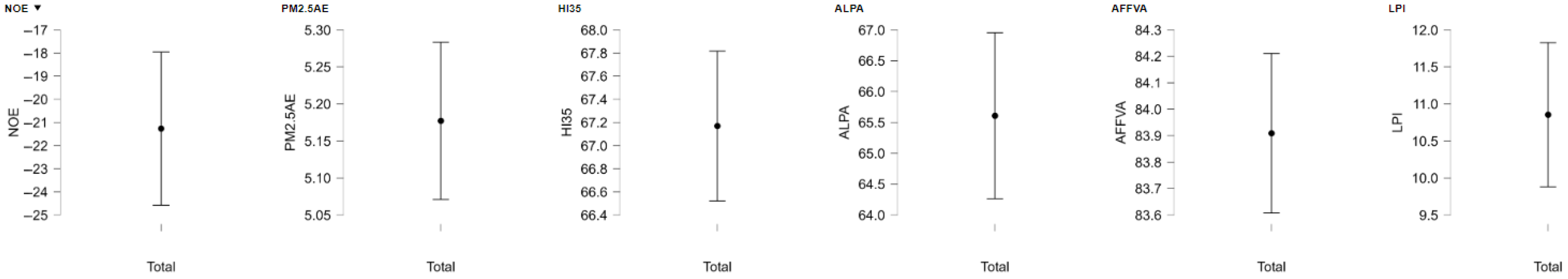

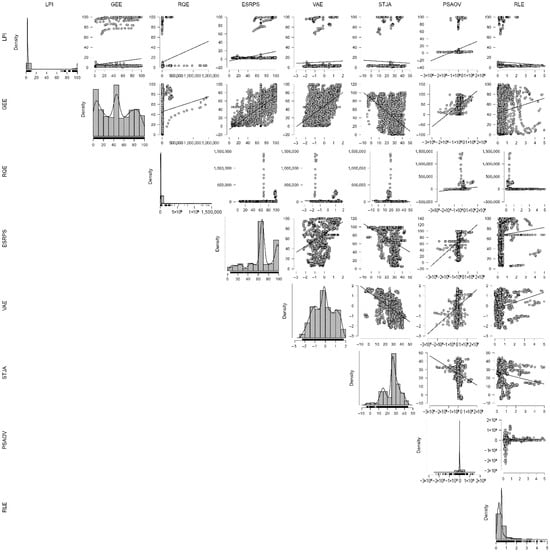

Applying the Random Forest process to the specified dataset unveiled pertinent information on the relative importance of explanatory variables to predict the Logistics Performance Index (LPI). The three importance metrics of Mean Decrease in Accuracy, Total Increase in Node Purity, and Mean Dropout Loss all recognize a core group of predictors key to determining the performance of both countries and times. The evidence shows agricultural land (ALPA) with a maximum Mean Decrease in Accuracy of 294.265 and is hence the most predictive variable on prediction accuracy. Removing or permuting ALPA causes the most harm to the performance of the Random Forest model. ALPA also tops Total Increase in Node Purity at a value of 98,796,892. This indicates how ALPA makes decision nodes purer with each split in the forest and contributes to its key determination of distinguishing better and worse performing logistics (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Random Forest Analysis of Environmental Drivers of Logistics Performance. The red diagonal line represents the 1:1 reference line (perfect agreement), where predicted values equal observed test values. Points lying on this line indicate ideal model performance, while deviations from the line reflect prediction errors and model bias.

The Mean Increase in Node Purity and Mean Decrease in Accuracy values reveal that Nitrous oxide emissions (NOE) and PM2.5 air pollution exposure (PM2.5AE) are major predictors of logistics performance. NOE’s Mean Decrease in Accuracy of 277.497 and exceptionally high Mean Increase in Node Purity of 114,677,766 rank the variable the second most important feature after ALPA, while PM2.5AE’s Mean Decrease in Accuracy of 224.074 and substantial Mean Increase in Node Purity also rank high. The results demonstrate that environmental degradation, as reflected in the release of greenhouse gases and air pollution, significantly influences logistics. This aligns with current trends in Random Forest analysis, in which nitrous oxide emerges as a significant predictor in environmental modeling [84,85]. The Heat Index above 35 °C (HI35) demonstrates significant predictive capacity in this regard, registering a Mean Increase in Node Purity of 77,966,120 and a Mean Decrease in Accuracy of 237.642. The rising significance of the Heat Index indicates that climate-related factors are exerting a growing—and profound—influence on the efficiency of logistics systems operating in extreme climates. Conversely, the “value added by agriculture, forestry, and fisheries” (AFFVA) variable shows little predictive power in this context. This variable’s Mean Increase in Node Purity of 30,634,277 and Mean Increase in Node Purity compared unfavorably with other factors but favorably with Mean Dropout Loss values, which placed ALPA and NOE first and highest in losses, followed by high rankings from PM2.5AE and HI35. This indicates that sectoral contributions are less significant than environmental factors. Dropout losses support this interpretation, wherein both ALPA and NOE exhibit the highest losses, followed by PM2.5AE and HI35 in descending order [86]. The results of the Random Forest analysis indicate that environmental factors are the primary determinants of interpretations of logistics improvements, while sectoral contributions are insignificant in this regard. This indicates that there must be synchronization in logistics improvements and environmental adaptation.

4.3. Identifying Country Profiles: A Cluster Analysis of LPI and Environmental Indicators

This section explores the clustering of countries based on environmental factors influencing the Logistics Performance Index (LPI) within the ESG framework. Using six different clustering algorithms—including Density-Based, Fuzzy C-Means, Hierarchical, Model-Based, Neighborhood, and Random Forest clustering—we assess model quality through key metrics such as Dunn Index, Silhouette score, Pearson’s gamma, and entropy. The goal is to identify homogeneous groups that reveal distinct patterns between environmental variables and logistics performance. Among the evaluated methods, Density-Based Clustering emerges as the most robust, offering well-separated, compact, and interpretable clusters that deepen understanding of the environmental dimension’s impact on LPI outcomes (Table 4).

Table 4.

Comparative Evaluation of Clustering Algorithms for Environmental Impacts on Logistics Performance.

The analysis of the results reveals that the Density-Based approach achieves the best structural quality, and that the best-balanced clustering sizes are obtained either with model-based or k-means clustering. The rank skill indicates that the Density-Based approach has the best structural quality, followed by hierarchical clustering. The Pearson correlation and Silhouette indices further support this result regarding structure quality. Although the maximum Diameter index values are not optimal, this does not strongly affect the overall quality of the approach. The Density-Based approach produces three clusters of sizes 2517, 238, and 8 with eight additional noise samples. This result indicates that although the clustering scheme works well overall, the resulting structure is unbalanced. For fuzzy c-means clustering methods, this structure balances relatively well compared with hierarchical clustering methods. The model-based and k-means clustering methods result in the most balanced structure. Based on the overall analysis above, the result again confirms that the Density-Based approach has the best structural quality compared to other methods. The k-means-based models are the most balanced and have the highest stability in terms of balanced clustering sizes. The overall analysis indicates that Density-Based clustering possesses the best structure quality compared to other approaches. The best-balanced clustering size structure can be obtained from either model-based or k-means clustering methods (Table 5).

Table 5.

Comparison of Clustering Algorithms by Cluster Size Distribution and Structural Stability.

Based on the analysis, the Density-Based clustering approach shall be discounted due to the formation of highly polarized clusters, in which 90% of the data points are confined to a single cluster. This defeats the purpose of understanding the relationship between environmental variables and their impact on the Logistics Performance Indicator. The Model-Based clustering analysis gives outcomes that are helpful in understanding the inter-relationships between environmental (E) factors studied in this research work: nitrous oxide emissions, exposure to PM2.5 air pollutants, heat stress exposure, proportion of land under agricultural use, value addition in agriculture, and Logistics Performance Indicator in terms of Environmental, Social, and Governance factors. Clustering based on mean values would allow sectorial profiles to be generated based on intensity levels. With eight clusters in the analysis, LPI values are mostly aggregated around the normalized mean, and the largest difference would come from factors in environmentally challenging situations. This means that no single environmental factor, but multiple factors, are responsible for LPI values. For instance, in Cluster 1, there are moderate levels of emissions and PM2.5 concentrations combined with below-average LPI values, signifying circumstances in which environmental pressures may hamper logistics systems. Conversely, in Cluster 2, there are clean environmental circumstances combined with slightly negative LPI values, signifying that effective logistics are not necessarily possible in excellent environmental conditions. However, in Cluster 3, there are the most stressful environmental circumstances caused by high levels of PM2.5 exposure and hot conditions combined with the highest LPI values signifying developed regions in which effective logistics are possible in areas with dirty environmental circumstances. Meanwhile, in Clusters 4 through 8, there are minimal levels of pollution and negligible use of arable land, yet relatively equivalent LPI values, suggesting that slight variations in environmental conditions do not affect logistical capability. The Model-Based clusters summarize that, in fact, the article’s conclusion regarding environmentally nonlinear LPI magnitudes holds true (Table 6).

Table 6.

Standardized Mean Values of Environmental and Logistical Indicators Across the Eight Model-Based Clusters.

The shape of the mixing probabilities distribution sheds further light on the significance of each component in capturing the correlation between Logistics Performance Index (LPI) and the environmental (E) component of the ESG structure. The probabilities indicate the number of observations associated with each component and allow us to identify which forms of environmental-logistics correlation the majority of observations in the data are distributed across. Component 1 has a probability of 0.247 and is the most common correlation type. This corresponds to about one out of every five observations in the dataset and asserts that the environmentally related factors and LPIs pertaining to this component capture the most common correlation pattern in the overall relationship between environmental pressures and LPI. Component 2, with probability 0.202, also shows a relatively abundant data representation and indicates the presence of another common correlation pattern in the data, through which environmental factors affect LPI. The remaining components, with probabilities of 0.075–0.104, capture less abundant data patterns and highlight more specific correlations between environmental factors and LPIs in smaller country groups. However, the existence of all components underlines that the correlation pattern between LPI’s and environmental factors is not homogenous in various contexts but depends in each particular case upon levels of release of polluting gases into the atmosphere from industry and transport, levels of air pollution caused after those releases by both gases and solid matter wastes from those releases through various meteorological factors like temperature and wetness levels, and structure parameters of agriculture in each country. The entire mixture probability distribution shows, in essence, that there are, in the overall correlation structure of the LPI-ESG-Environment model, not only the dominant but also other relatively rare patterns that are essential for covering the variability of this correlation phenomenon worldwide. This pattern further underscores the multidimensional nature of LPI-ESG-Environment correlation patterns, highlighting the overall interrelationships between environmental sustainability and LPIs (Table 7).

Table 7.

Mixing Probabilities of the Eight Components in the LPI–ESG–Environment Mixture Model.

The analysis of the standardized means for each component sheds further light on how different components of the environmental variables are linked to the values of the Logistics Performance Index (LPI). The most interesting result is Component 3, with the LPI well above the average. This particular component has moderate GHG emissions and PM2.5 exposure levels, high heat stress, and high weights for agricultural factors. This particular combination shows that quite high levels of logistical strength can coexist with strong levels of environmental pressure, further establishing the nonlinear relationship between environmental sustainability and logistical effectiveness. The remaining components are negative in terms of the LPI values. This shows that each component has underperformed in terms of average logistical capability. Component 1 shows relatively lower levels of GHG emissions and air pollution, along with reduced LPI levels and strong levels of agricultural factors. This further suggests that there may be restrictions on overall logistical efficiency in the particular economy, due more to structural factors than to environmental pressures. Component 2 further provides evidence that the values resulting from environmental factors are not linear. This component shows relatively higher GHG emissions alongside relatively higher levels of both temperature and humidity. The next components, 4 through 8, appear negligible in terms of both PM2.5 levels and Heat Index 35 levels, in combination with considerable levels of agricultural land use. This further indicates overall particular levels of logistical capacity in each of these economies, with relatively more homogeneous particular levels of environmental factors. This further suggests that there may not be substantial nonlinear variations in particular levels of LPI, in combination with relatively marginal variations in particular levels of individual factors (Table 8).

Table 8.

Component-Wise Standardized Means of Logistical and Environmental Factors in the Mixture Model.

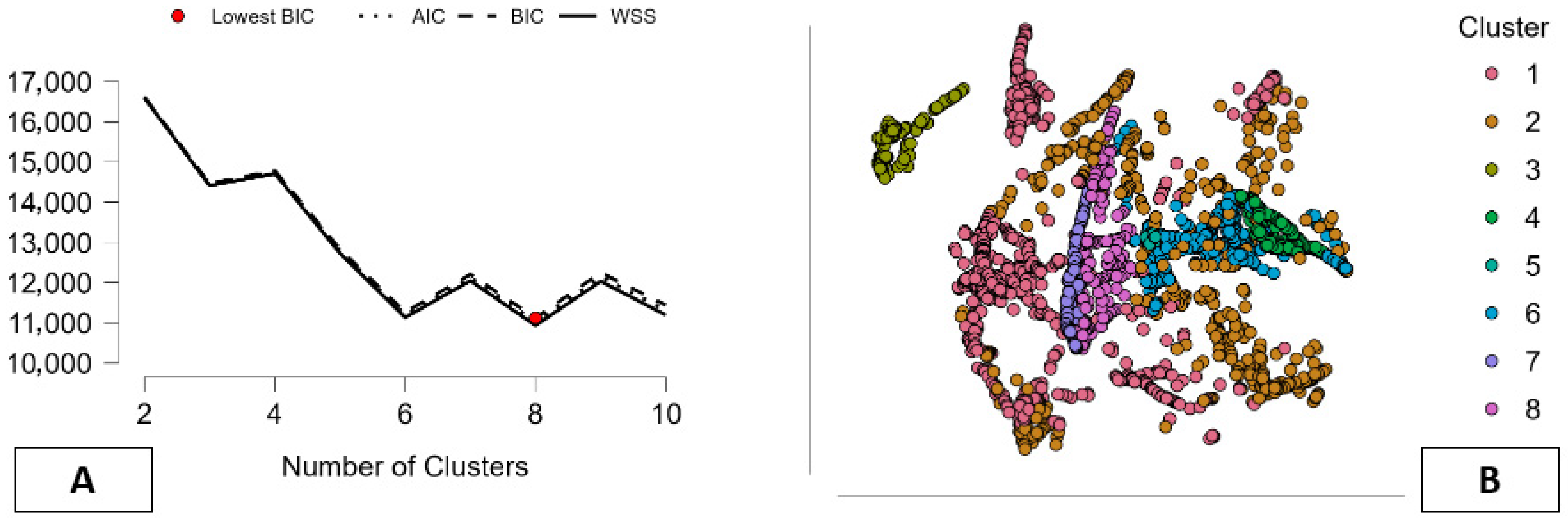

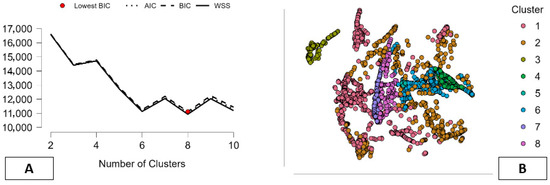

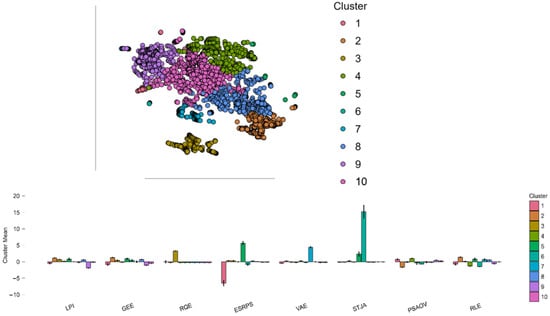

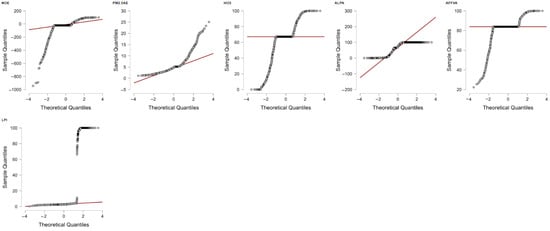

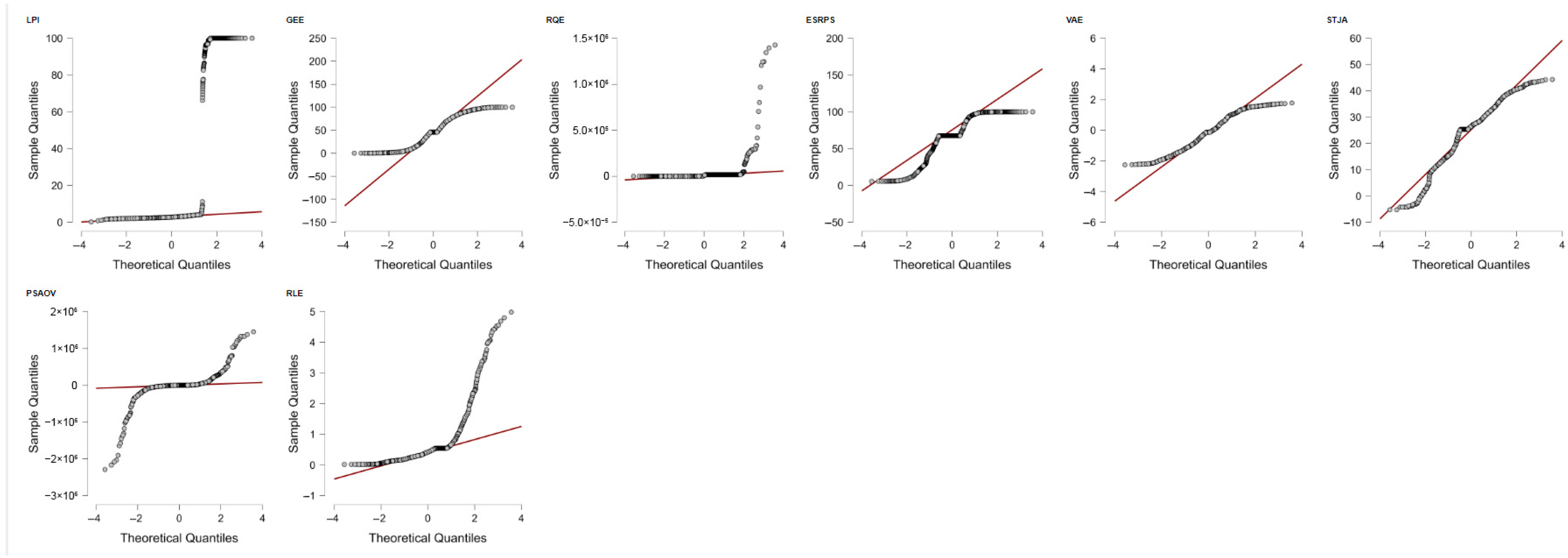

Figure 3 provides a summary of the model-based clustering outcomes with respect to both identifying the number of clusters and visualizing the data structure in the data space. Figure 3A illustrates the change in Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) and Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) scores and Within-Cluster Sum of Squares (WSS) values with respect to the increase in the number of clusters. The red spot in the figure marks the point with the lowest BIC score; this indicates that the best compromise between data fit and model complexity is achieved with the model including eight clusters. This indicates that this number of factors provides sufficient information about the data structure pattern without sacrificing accuracy through overfitting or underfitting. The plot of the WSS indicates a gradual reduction in values until reaching the point corresponding to the medium number of clusters, beyond which the values vary, though in a smooth pattern. This pattern corresponds to data with a complex structure that cannot be adequately represented by a few clusters. Figure 3B provides information regarding the pattern of the eight clusters in the projected feature space. The clusters are well differentiated in this representation and express complex configurations in most cases. This color representation indicates that each component differs in predetermined regions of the data point space. This indicator also shows regions of differentiation in most components, with some appearing sparser than others. This provides information regarding the complexity of the patterns of various environmental and logistical factors represented through the model. The structure that emerges from this representation provides information on the effectiveness of the clustering analysis through the model’s grouping of profiles in conformity with the analysis’s objectives (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Model-Based Clustering Evaluation and Visualization of Cluster Structure. Note: Panel (A) displays changes in AIC, BIC, and WSS values across models with varying numbers of clusters, with the lowest BIC indicating an optimal solution at eight clusters. Panel (B) illustrates the spatial arrangement of the eight identified clusters in the projected feature space, highlighting distinct and complex structural patterns within the data.

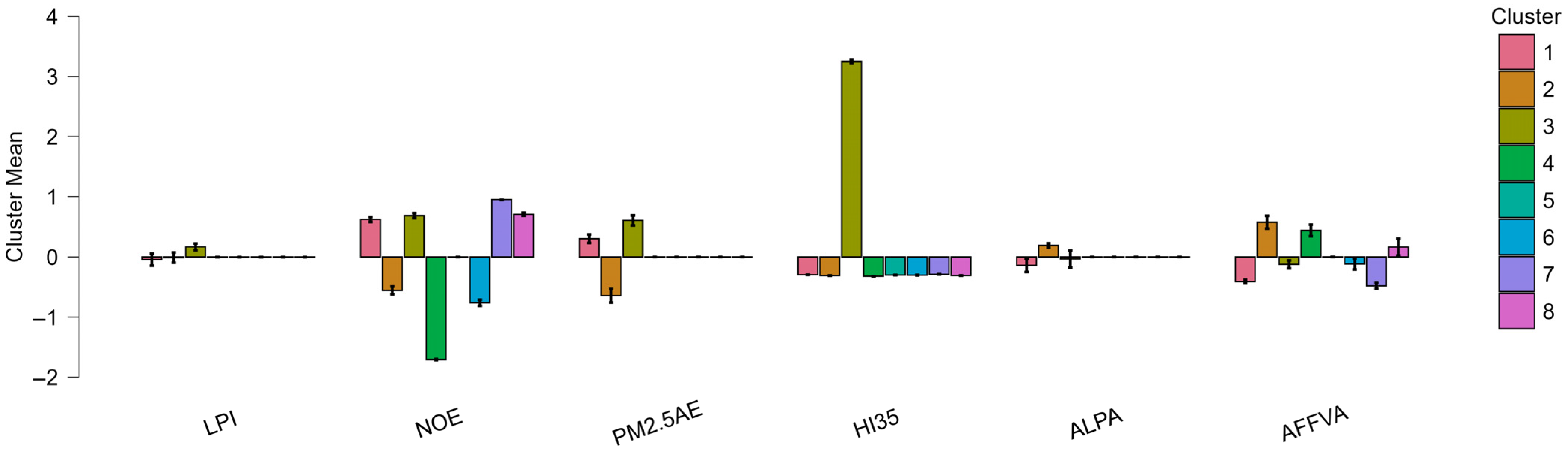

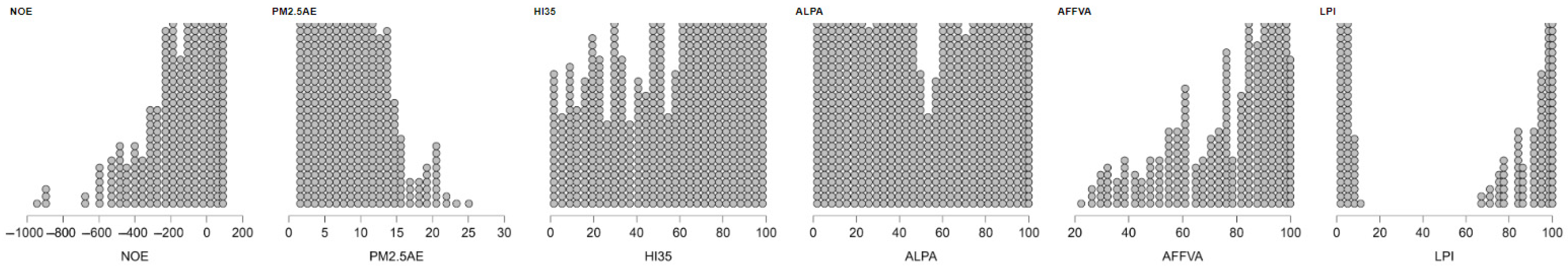

Figure 4 depicts the standardized means for each variable across the eight clusters formed using the model-based approach, thereby clarifying the distinct environmental-logistical configurations within each grouping. The LPI values show small variation, indicating minimal differences among the clusters in LPI. However, environmental factors exhibit significant variation. The nitrous oxide emissions (NOE) and PM2.5 exposure values show both positive and negative standardisations, indicating clusters with high levels of pollution and others that are relatively clean, based on environmental conditions. The Heat Index (HI35) showed the highest discrimination value, with one cluster recording a substantially high value, indicating higher heat stress in this grouping than in others. The other clusters recorded values close to the overall average. The Agricultural land share (ALPA) and Agricultural value added (AFFVA) recorded moderate discrimination values. The figure illustrates that overall group formation is driven by environmental factors rather than LPI values, indicating that the majority of the model’s variation is attributable to these factors (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Standardized Variable Means Across the Eight Model-Based Clusters. Note: This figure displays the standardized means of key environmental and logistical variables across the eight clusters derived from the model-based clustering approach. LPI values show minimal variation across clusters, whereas environmental variables—particularly NOE, PM2.5AE, and HI35—exhibit strong differentiation. HI35 demonstrates the greatest discrimination, with one cluster showing notably elevated heat stress relative to others. ALPA and AFFVA present moderate variation among clusters. Overall, the figure highlights that cluster differentiation is primarily driven by environmental factors rather than LPI values.

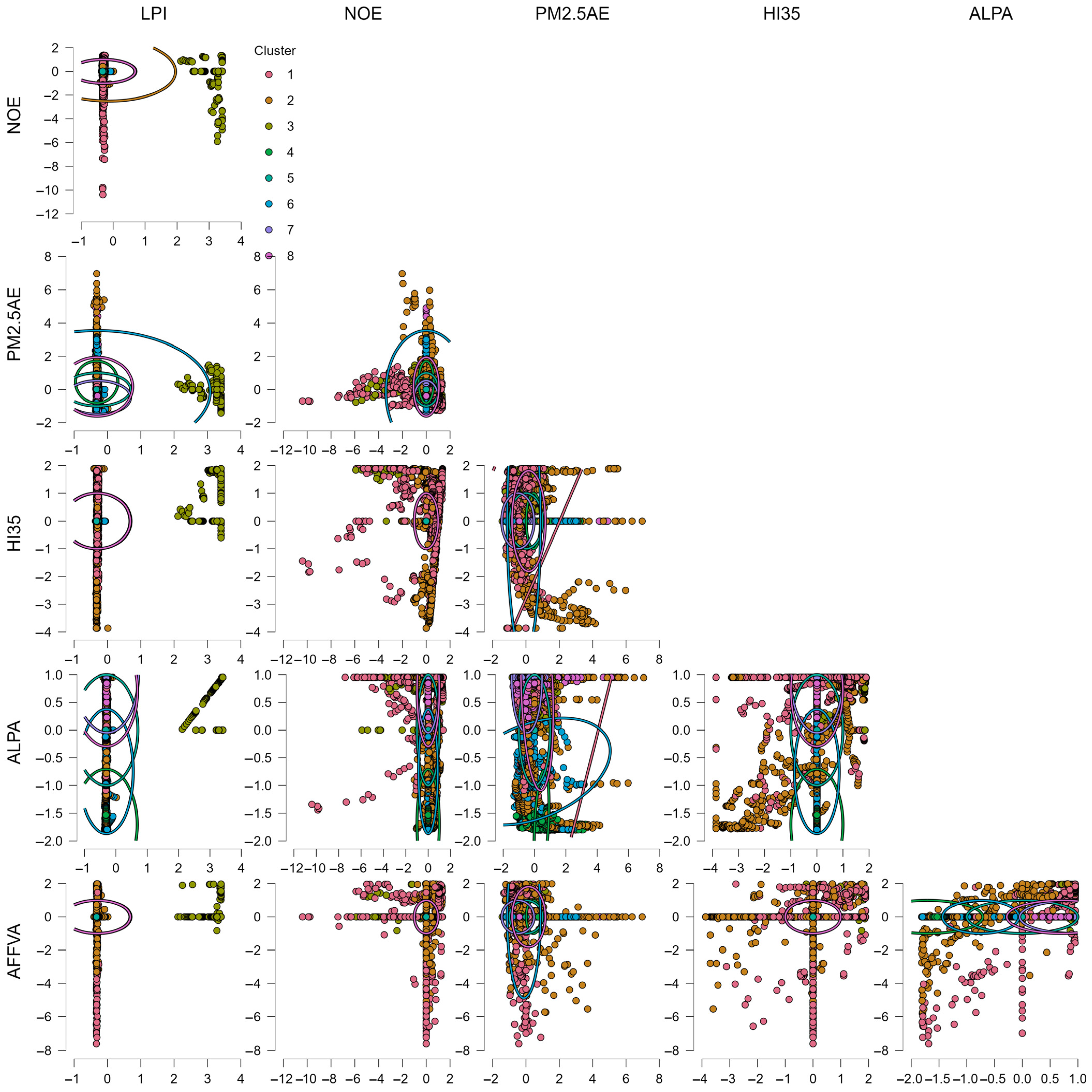

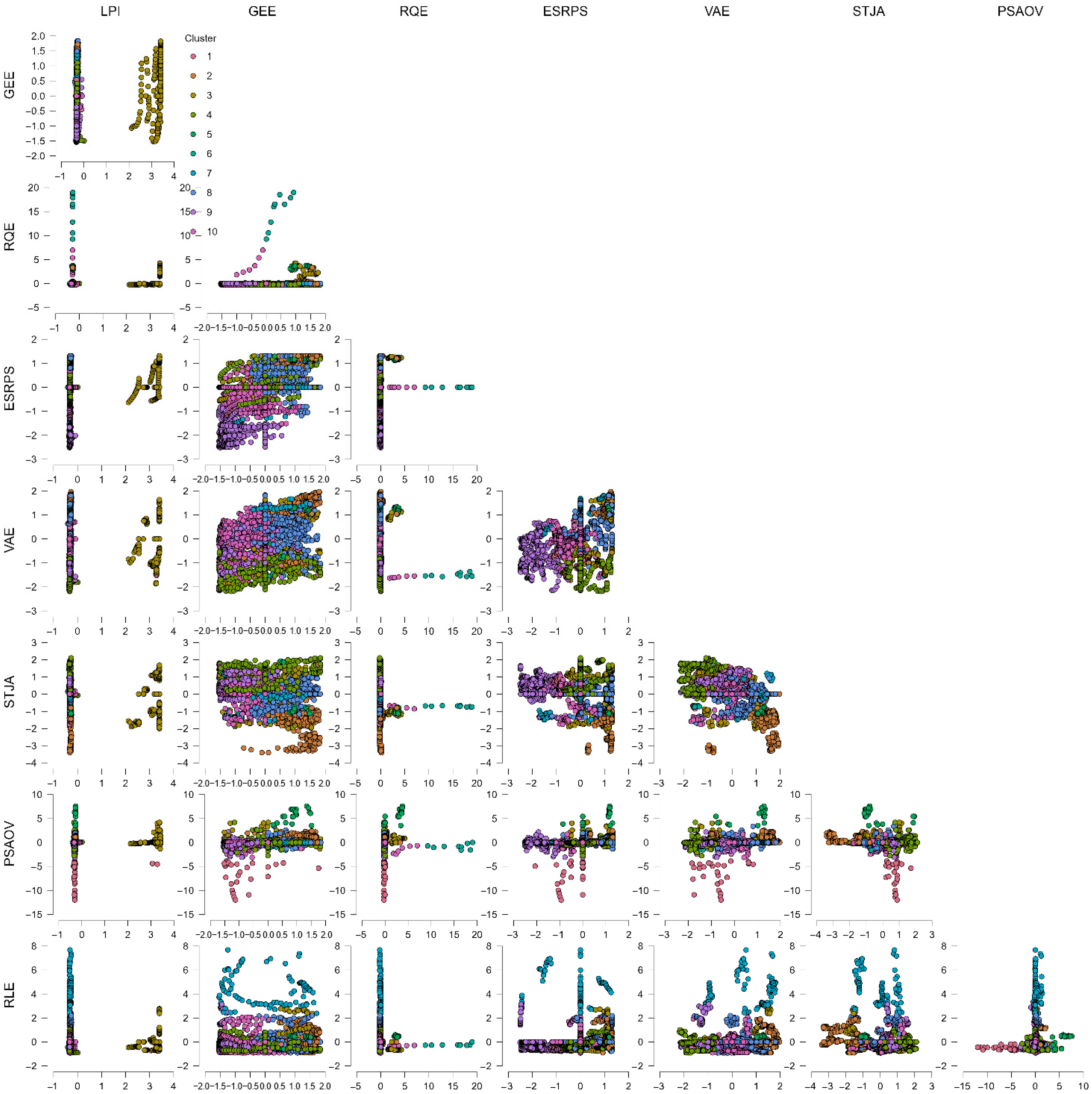

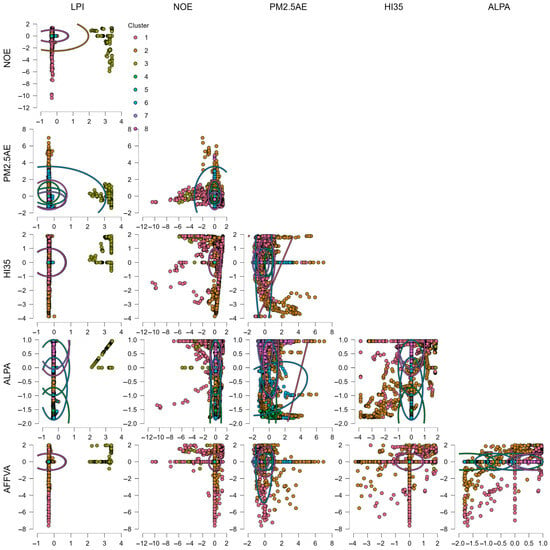

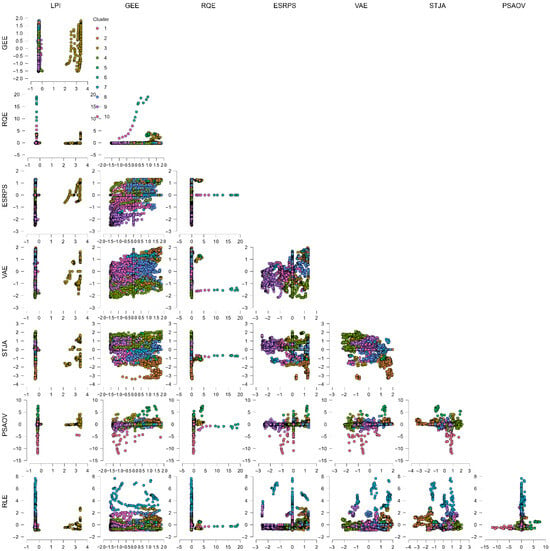

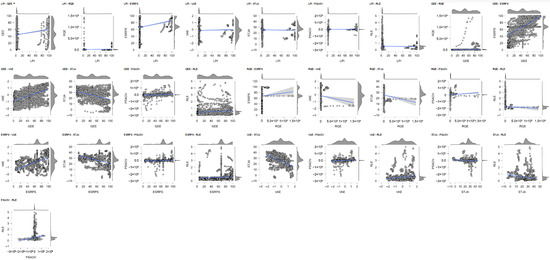

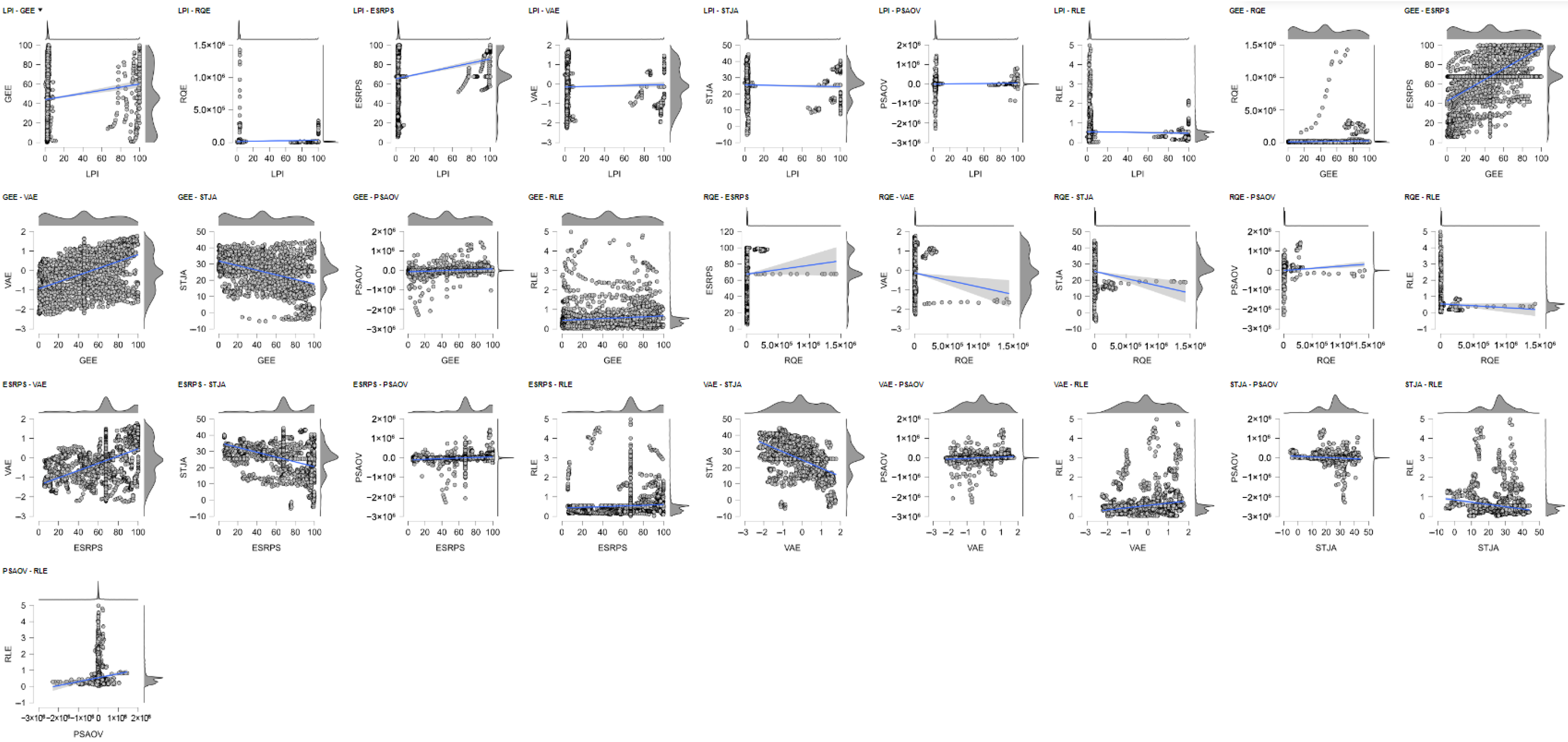

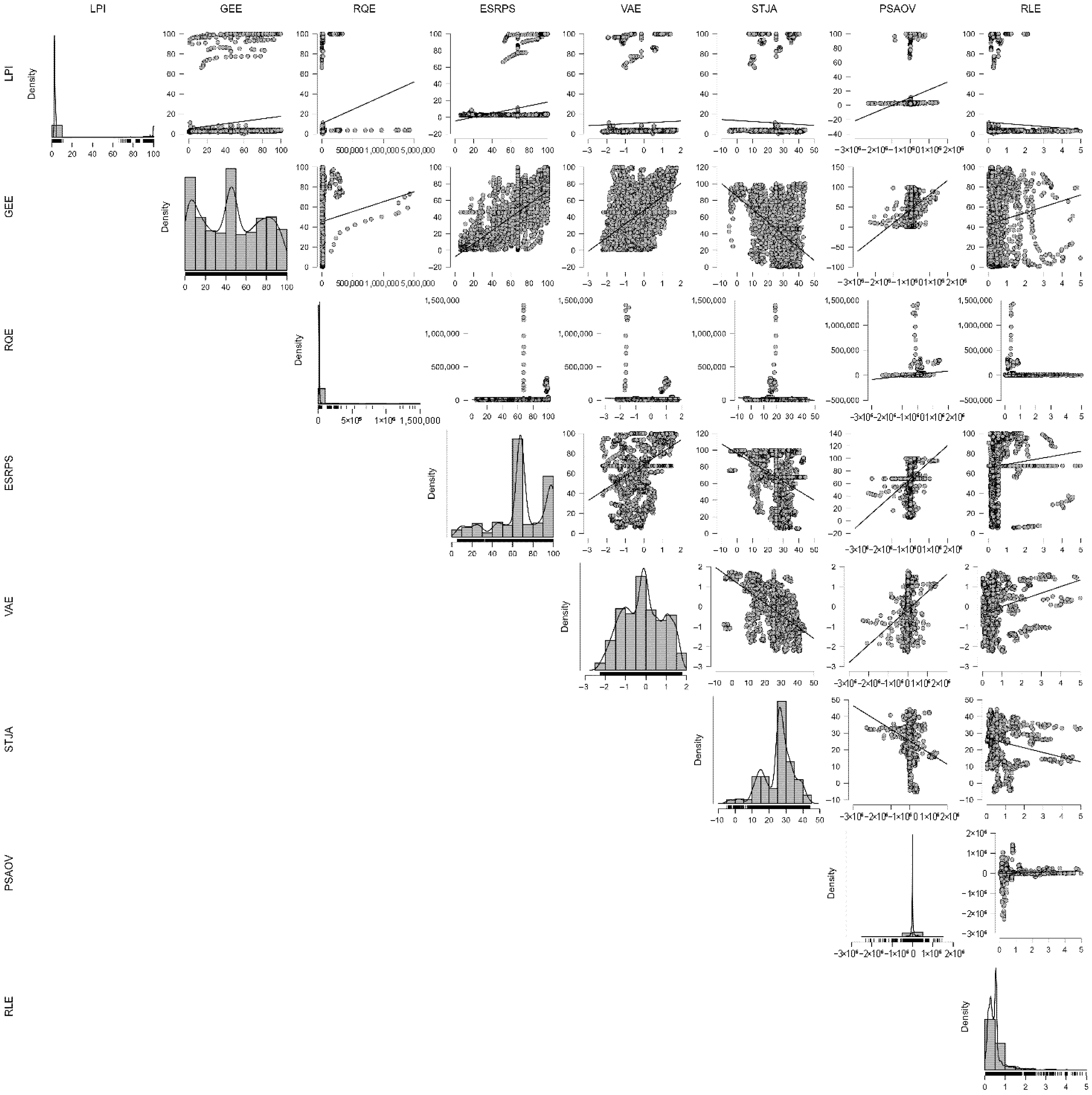

Figure 5 summarizes a pairwise scatter plot matrix of six standardized variables across eight clusters derived from a model-based clustering analysis. Each subplot presents the relationship between two variables using colored ellipses, noting the probability distribution of each component. The combined results indicate that environmental factors such as NOE, PM2.5 exposure levels, and HI35 are the key determinants in distinguishing the various clusters. Clusters are arranged in well-defined regions based on these factors, especially in the NOE and PM2.5 exposure level plots, where clear separations occur between high and low emission factors. However, the most significant determinant in this analysis is the HI35 variable, which shows one component with abnormally high levels of heat stress compared to other factors. Conversely, LPI shows minimal variation between factors and groups, yet remains clustered around the standard mean in terms of standardization. The result indicates that variations in logistical performance do not significantly account for the observed pattern in the data and supports the primary idea of relying on the environmental factors outlined in this analysis. The agricultural factors of ALPA and AFFVA provide more information, though they exhibit less-defined edges in the figure, suggesting minute variations in land use or in the overall economic role of agriculture. This analysis indicates that the figure presents a complex clustering pattern across multiple dimensions, in which environmental factors account for overall variation, except for LPI, which is significant yet supplementary in the overall context of Environmental Social Governance (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Pairwise Scatter Plot Matrix of Standardized Variables Across Eight Model-Based Clusters. Note: This figure presents a pairwise scatter plot matrix of six standardized variables across eight clusters derived from the model-based clustering analysis. Each subplot illustrates the bivariate relationship between variables, with colored ellipses representing the probabilistic distribution of each cluster component. The environmental variables—NOE, PM2.5AE, and HI35—demonstrate the strongest discriminatory power, producing distinct separations between high- and low-emission clusters. HI35 is the most influential factor, with one cluster exhibiting markedly elevated heat stress. In contrast, LPI shows minimal variation across clusters, clustering closely around the standardized mean and contributing little to group differentiation. Agricultural variables (ALPA and AFFVA) reveal moderate but less sharply defined patterns, suggesting subtle variations in land use and agricultural economic contribution. Overall, the matrix highlights that environmental factors predominantly drive cluster formation, whereas logistical performance indicators play a supplementary role within the broader ESG context.

5. Exploring the Interaction Between Social Factors and LPI in an ESG Context

This part examines the causality between the Logistics Performance Index (LPI) and the Social (S) pillar of the ESG framework in 163 nations from the period 2007 to 2023. Employing two-stage least squares (TSLS) and generalized two-stage least squares (G2SLS) techniques, the research looks at how important social variables like water and sanitation accessibility, education, population structure, income distribution and labor conditions influence the efficiency of logistics. Accounting for endogeneity by using a comprehensive set of instrumental variables, the outcomes show social development drivers to be important influencers of logistic performance and prove why socially inclusive approaches are required to boost supply chain systems everywhere.

5.1. Analyzing the S-Social Component’s Impact on Logistics Performance

This section explores the relationship between the Logistics Performance Index (LPI) and the Social (S) pillar of the ESG model. Using fixed-effects two-stage least squares (TSLS) and generalized two-stage least squares (G2SLS) methods, the study investigates how social factors—such as access to basic services, education, income distribution, labor market conditions, and demographic structures—impact logistics performance. The results reveal that improvements in social indicators can have both positive and negative effects on LPI, highlighting the intricate connections between human development, equity, and logistics efficiency within a sustainable growth framework.

We have estimated the following model:

- (First Stage)

- i = 163

- t = [2007; 2023].

Results are indicated in Table 9.

Table 9.

Impact of Social Factors on Logistics Performance: Fixed-Effects TSLS and G2SLS Estimates.

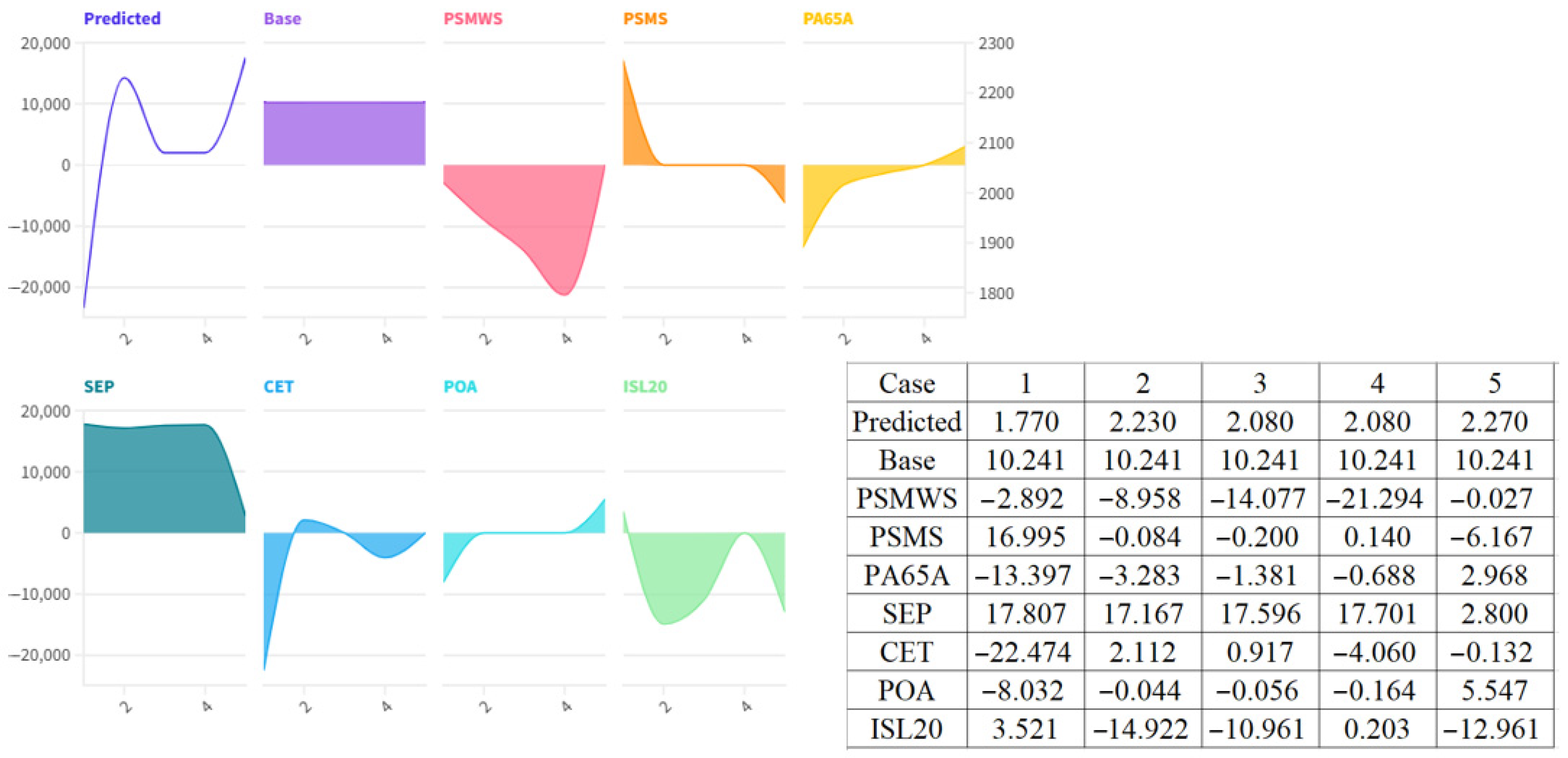

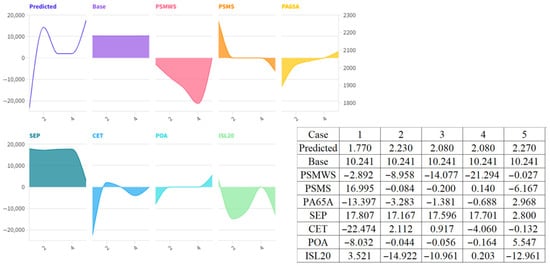

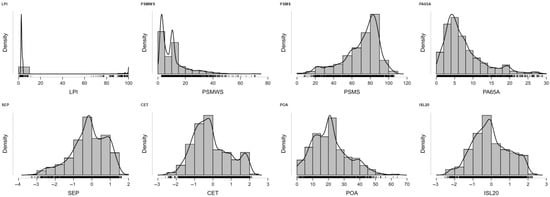

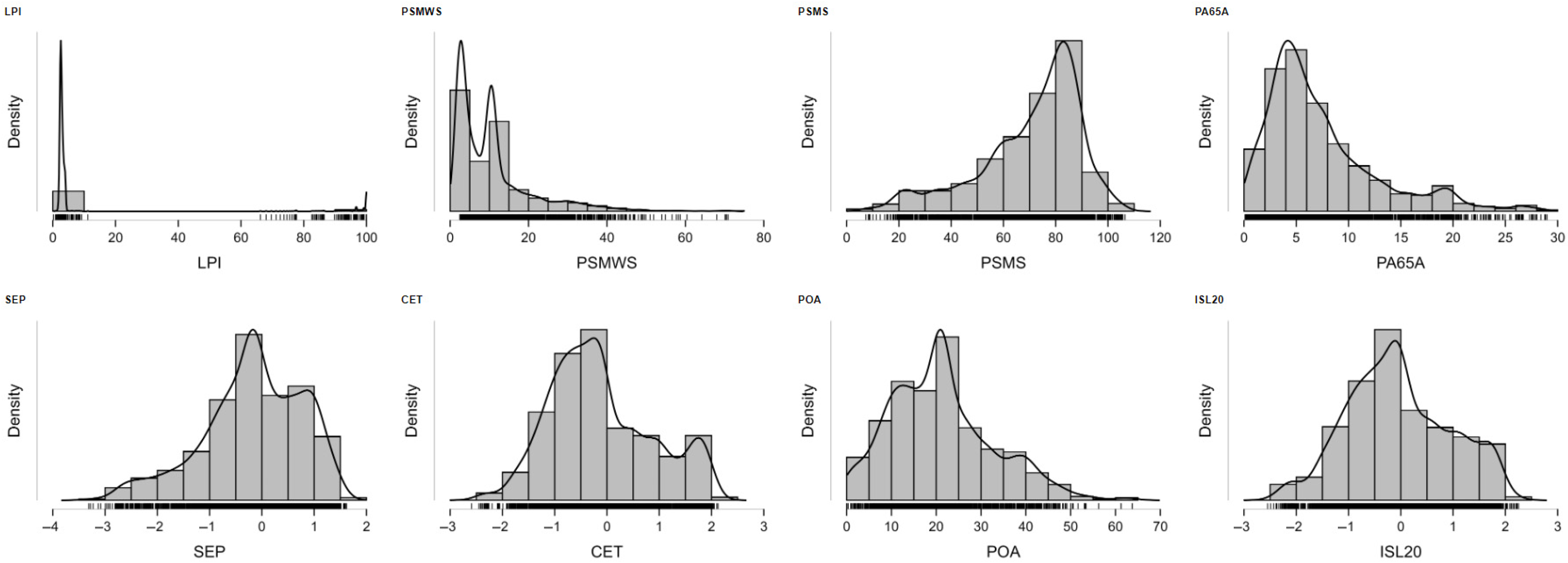

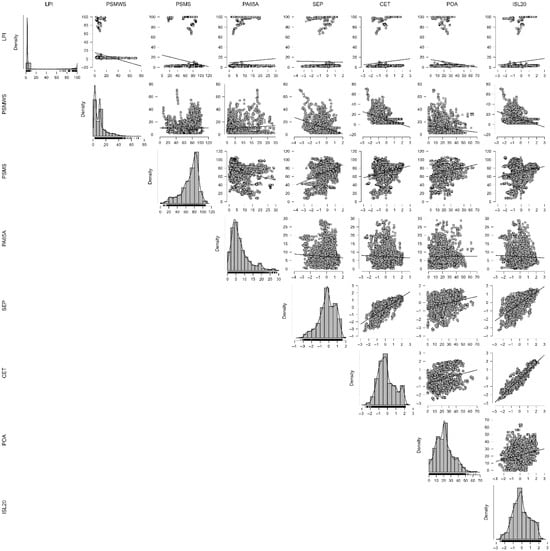

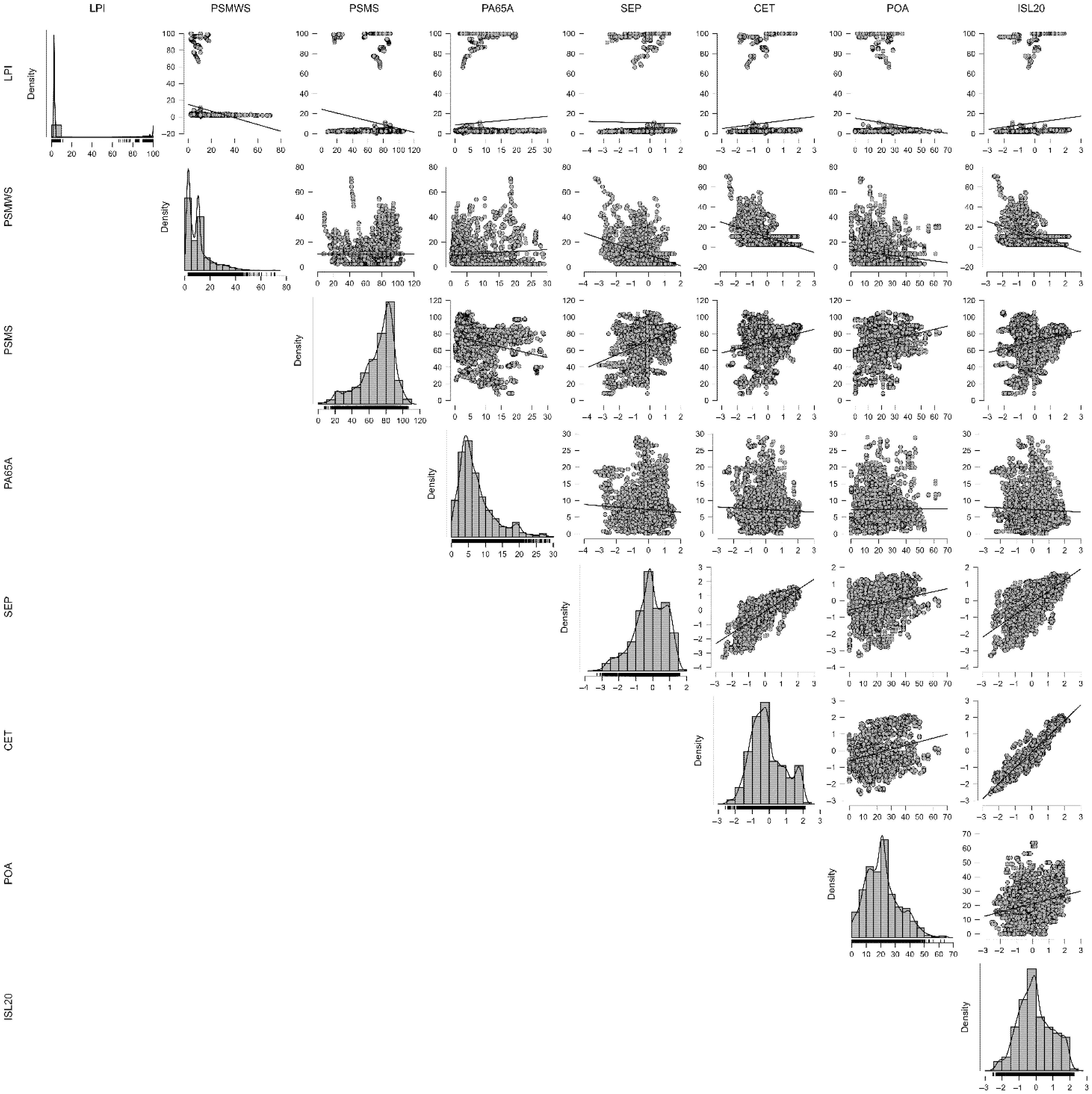

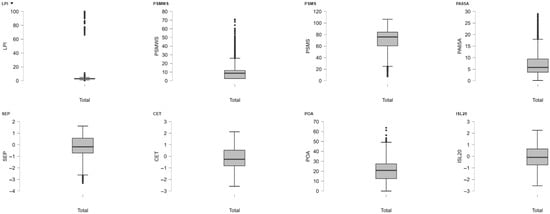

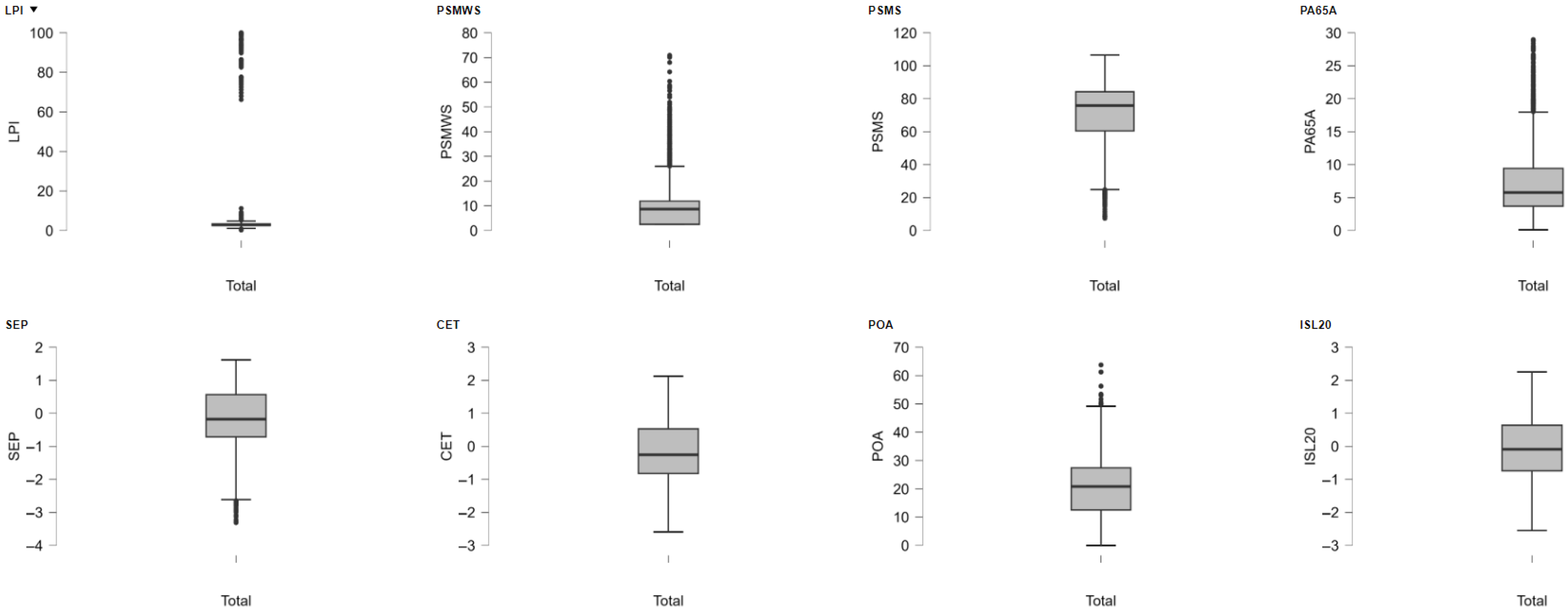

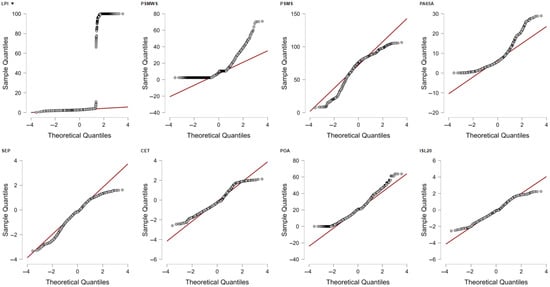

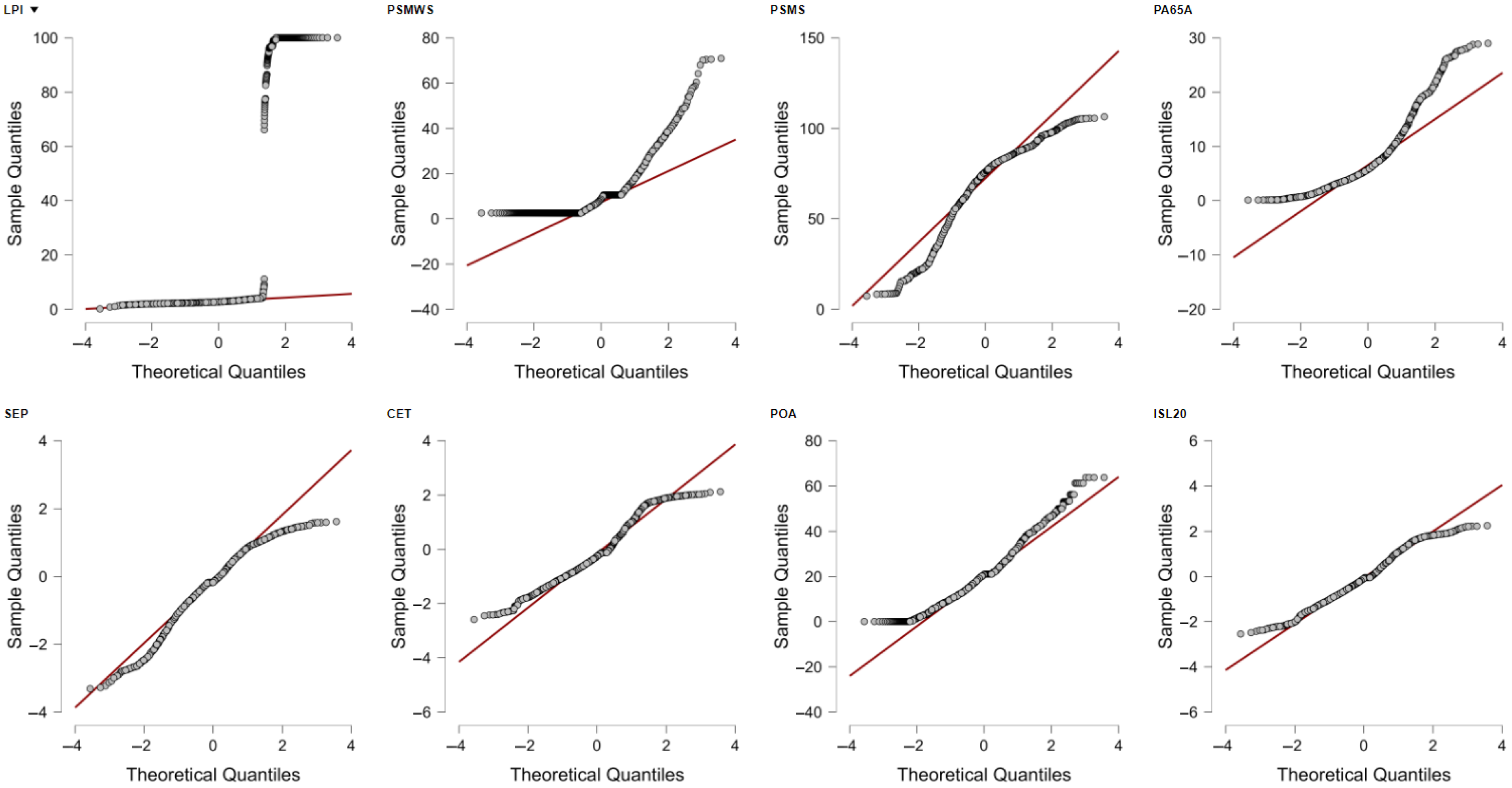

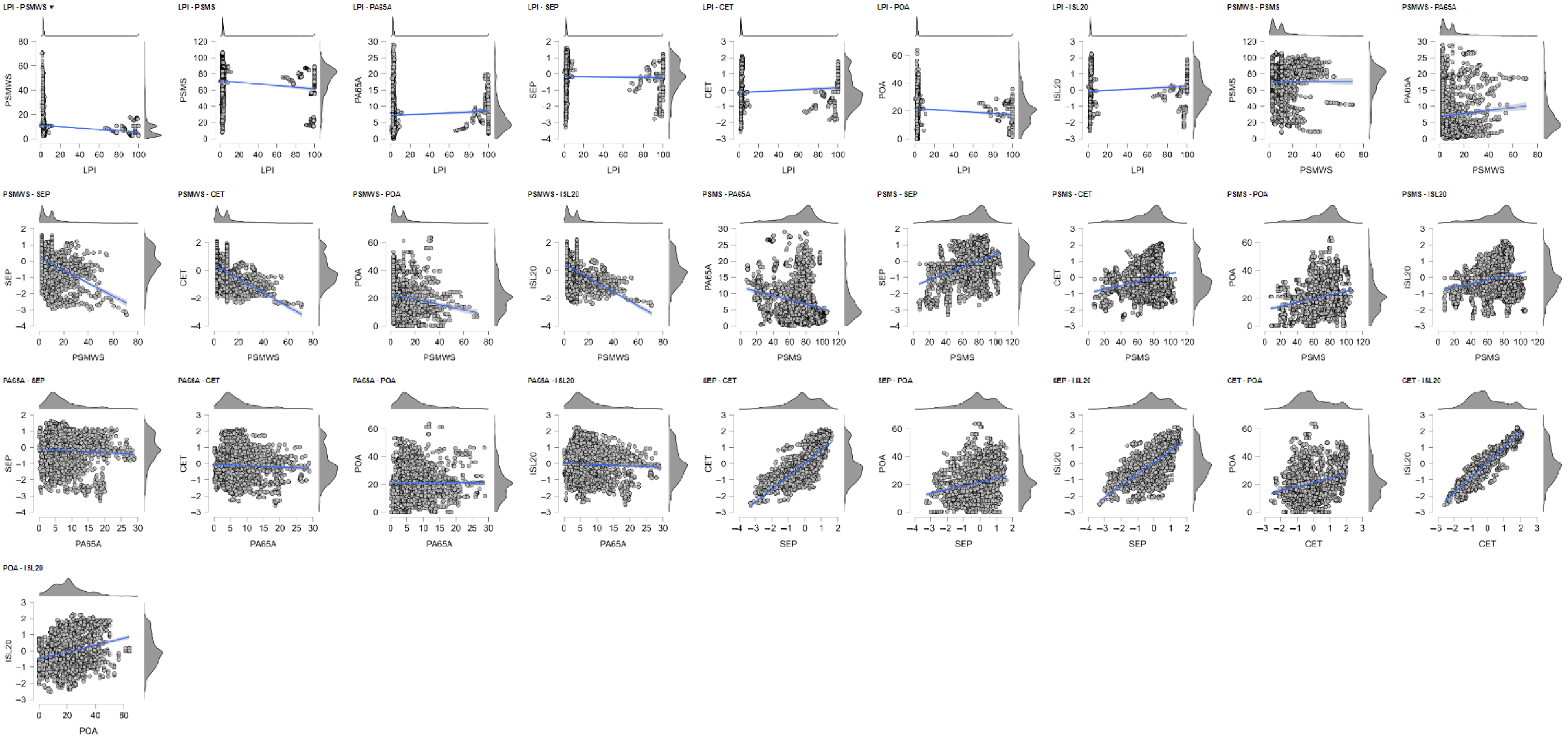

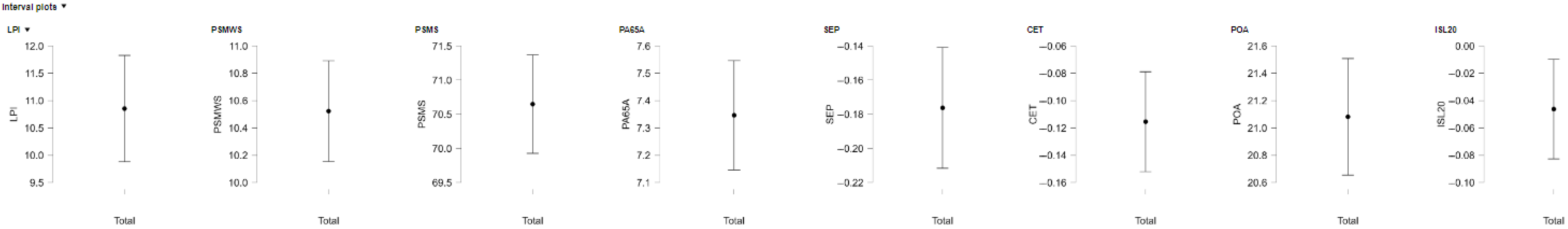

This research examines the determinants of the Logistics Performance Index (LPI) of 163 countries over a period of 17 years using fixed-effects two-stage least squares (TSLS) and generalized two-stage least squares (G2SLS) models with random effects. The framework includes a broad range of instruments capturing economic, demographic, governance, and environmental data. One key finding from the research has a direct bearing on the Social (S) component of the ESG framework. The endogenous variables—i.e., access to safely managed drinking water (PSMWS) and sanitation services (PSMS), elderly population percentage (PA65A), primary school enrollment (SEP), employment of children (CET), prevalence of overweight adults (POA), and income share held by the poorest 20% (ISL20)—all are dimensions of social development considered essential. The correlation unfolds as follows: More widespread provision of simple services like water and sanitation is somewhat counterintuitively negatively related to the variable of logistics performance. While statistically robust, however, the effect is small and implies high-performance social service provision may be related to more rigorous regulatory systems or greater operational costs marginally impacting the effectiveness of logistics. Demographic issues are also seen: a larger percentage of aging population and more enrollment in schools is negatively related to LPI. This may represent the effects of changing labor market fundamentals, whereby aging societies and higher education enrollment fewer youth in the workforce temporarily limit the labor available to the heavily labor-intensive industries like logistics. The opposite effect is identified in the case of the prevalence of child labor (CET), which has a strong positive effect on LPI—a worrying indicator. This indicates improving the performance of logistics in less developed economies may depend partly on exploitative employment arrangements. This has a fundamental social sustainability issue at its core: efficiency gains at the expense of youth welfare and human rights are unacceptable if it goes against the core tenet under the Social pillar of ESG. Equally, the positive effect of overweight prevalence (POA) on the variable of logistics performance is likely a reflection of deeper patterns of economic prosperity and consumerism requiring more sophisticated systems of logistics. This also has social concerns related to modern lifestyles and unjust food systems. The negative correlation of income inequality (ISL20) and the variable of logistics performance is a fundamental finding. In economies in which the bottom 20% of the population possess less income, logistics systems look less efficient. More economic inequality contributes to fragmented markets, stagnant mobility, and lower human capital, all of which contribute to less smooth logistics operations. From an ESG-Social stance, this result confirms that more inclusive economic development bolsters better-performing logistics and supply chain systems. The extensive range of tools utilized—and range of indicators including internet penetration and rule of law, female labor force participation and governance—also highlight social and institutional environments as the determinants of the performance of logistics. More robust social structures, improved legal protections and more inclusive labor markets are not social goods alone but also efficiency enablers of global supply chain operations. In general, this examination makes it evident that social development underpins the performance of logistics. Education, services provision, equality of condition, labor quality and provision of health services all play important parts. Logistics infrastructures policies to enhance them must be strongly integrated with social investment plans to guarantee progress in the area of logistic infrastructures does not happen at the expense of the development of humanity but hand in hand with it and in full coherence with ESG-S objectives.

Causality. The causal identification strategy employed—fixed-effects TSLS and G2SLS with a rich instrument set—permits a strong identification of the causal impact of social variables on the Logistics Performance Index (LPI). The coefficients imply the causal influence of variations in social development indicators on logistics performance and do not simply correlate with it. In particular, better access to safely managed water (PSMWS) and sanitation (PSMS), a larger elderly population percentage (PA65A), and increased school enrollment (SEP) are causally associated with a marginally declining LPI, possibly through augmented regulatory costs or labor force shortages. More troublingly, the causal positive effect of child labor (CET) on LPI illustrates how, in certain settings, improving the efficiency of logistics depends on unsustainable and ethically challenged forms of labor. The causal negative effect of income inequality (ISL20) on LPI also shows how more equal income distribution facilitates the efficiency of the logistics system. Significantly, the instrumental variables technique enhances the causal assertions by reducing endogeneity generated by reverse causality or missing variable bias. Nevertheless, low R2 values signify how social variables have statistically significant causal impacts but account for a minimal share of overall variance in the performance of the logistics system and argue in favor of combining social interventions with more general economic and infrastructural reforms.

Overall impact of the S-Social component within the ESG model. The evidence presents unequivocal empirical proof that the Social (S) pillar of the ESG framework has a causal and sizable yet multifaceted effect on the performance of logistics. Social improvements in indicators have a positive or negative impact on the Logistics Performance Index (LPI), highlighting the subtle tradeoff between operational efficiency and human development. The provision of fundamental services such as safely managed drinking water (PSMWS) and sanitation (PSMS), demographic transitions like population aging (PA65A), and increased enrollment in schools (SEP) are causally linked to declines of minor magnitude in the performance of logistics, probably indicative of increased regulatory costs or labor shortage. The worrying causal positive effect of child labor (CET) on LPI also indicates the persistence of socially unsustainable patterns supporting the efficiency of logistics in some economies. The positive causal effect of overweight prevalence (POA) on LPI also shows stronger consumer-led logistic requirements, while income inequality (ISL20) has a negative effect on logistic efficiency and highlights the importance of equalized growth. Although the causal evidence is statistically strong because a rich list of instrumental variables was used, the low values of R2 reveal a minimal share of variance explained by social variables. Summing up, the development of logistic performance has to be coordinated with socially sustainable development policies completely aligned with ESG-S principles.

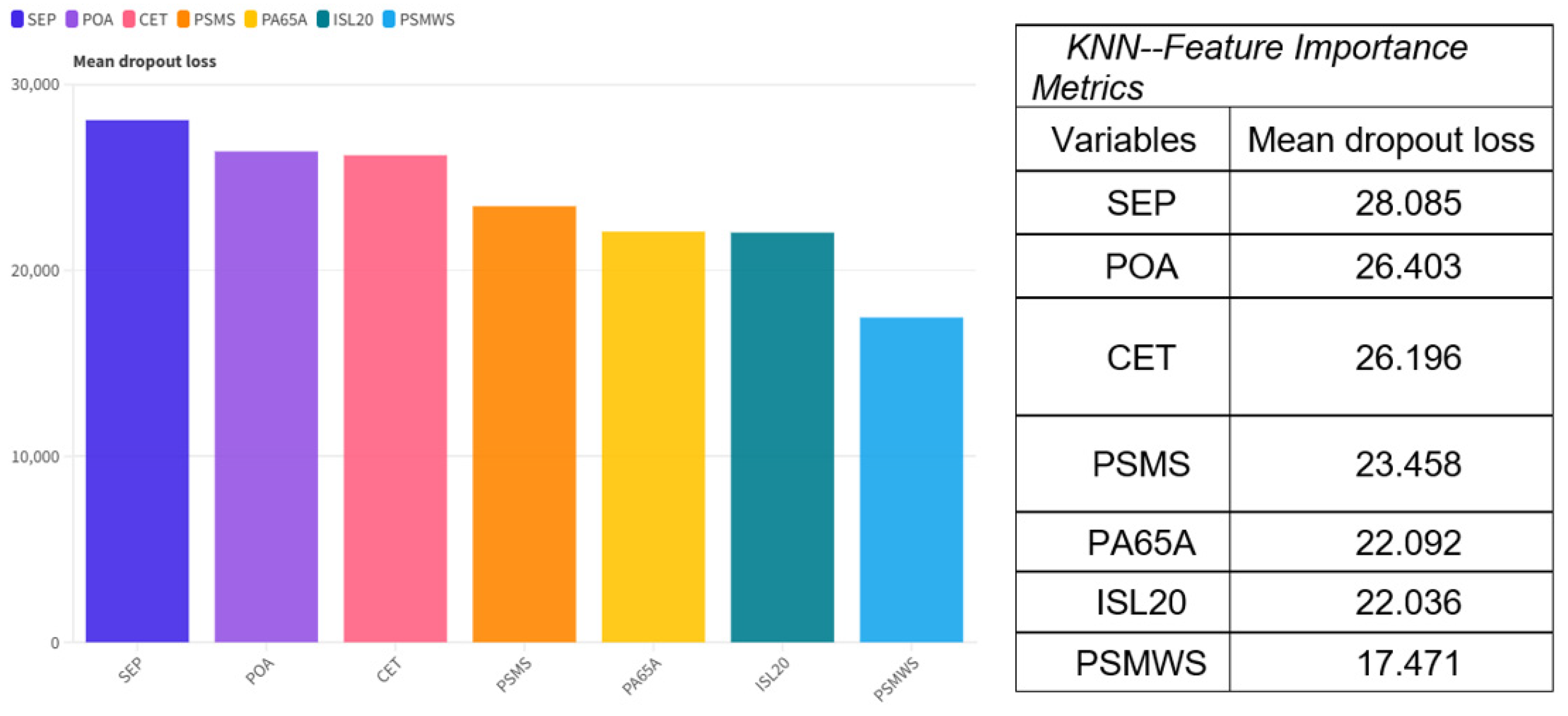

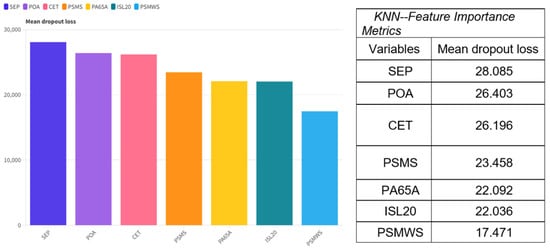

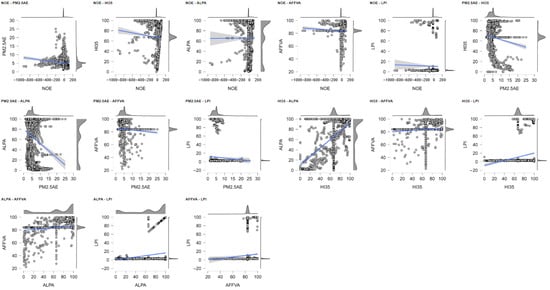

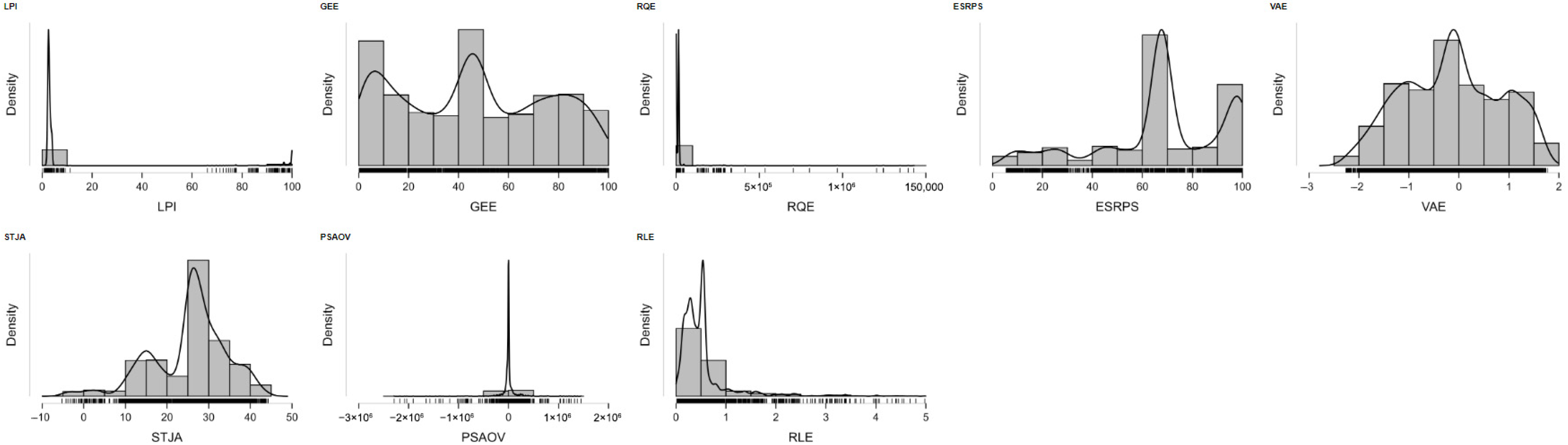

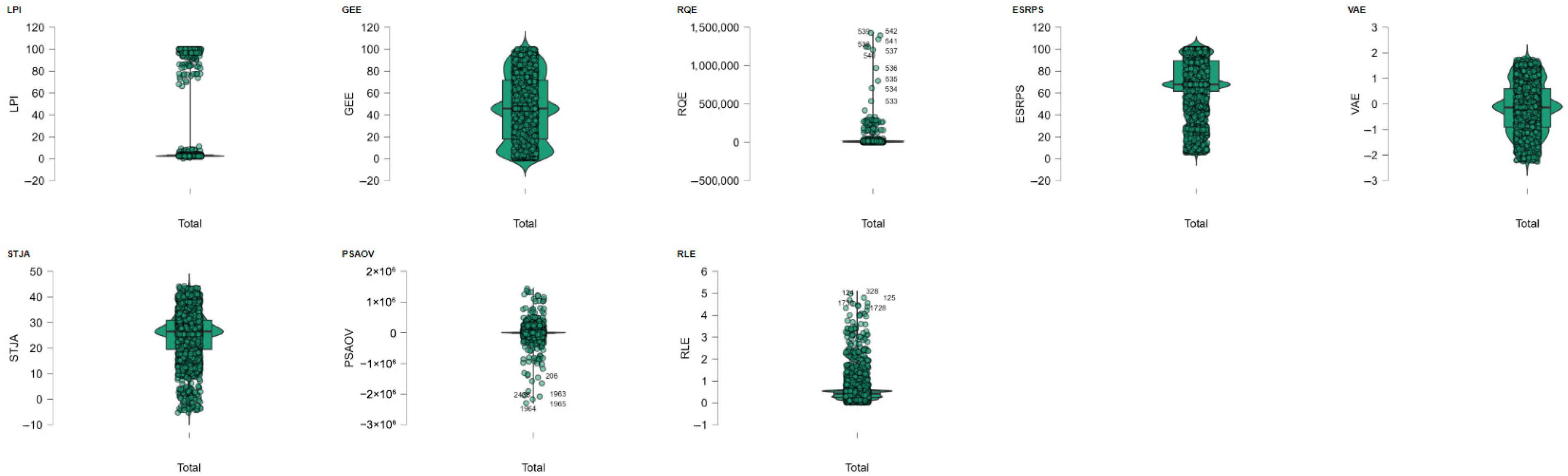

5.2. Machine Learning Estimation of Socio-Economic Impacts on Logistics Performance

This section applies machine learning methods to estimate the relationship between socio-economic variables and the Logistics Performance Index (LPI). Several algorithms—including Boosting, Decision Trees, Random Forests, and Support Vector Machines—are evaluated based on normalized performance metrics. The K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) algorithm emerges as the most accurate and robust model, achieving the lowest prediction errors and the highest explanatory power. Further analysis identifies key social predictors, such as school enrollment, overweight prevalence, and child labor incidence, highlighting the critical influence of human development factors on logistics performance. These results underline the complex interplay between social structures and logistic efficiency (Table 10).

Table 10.

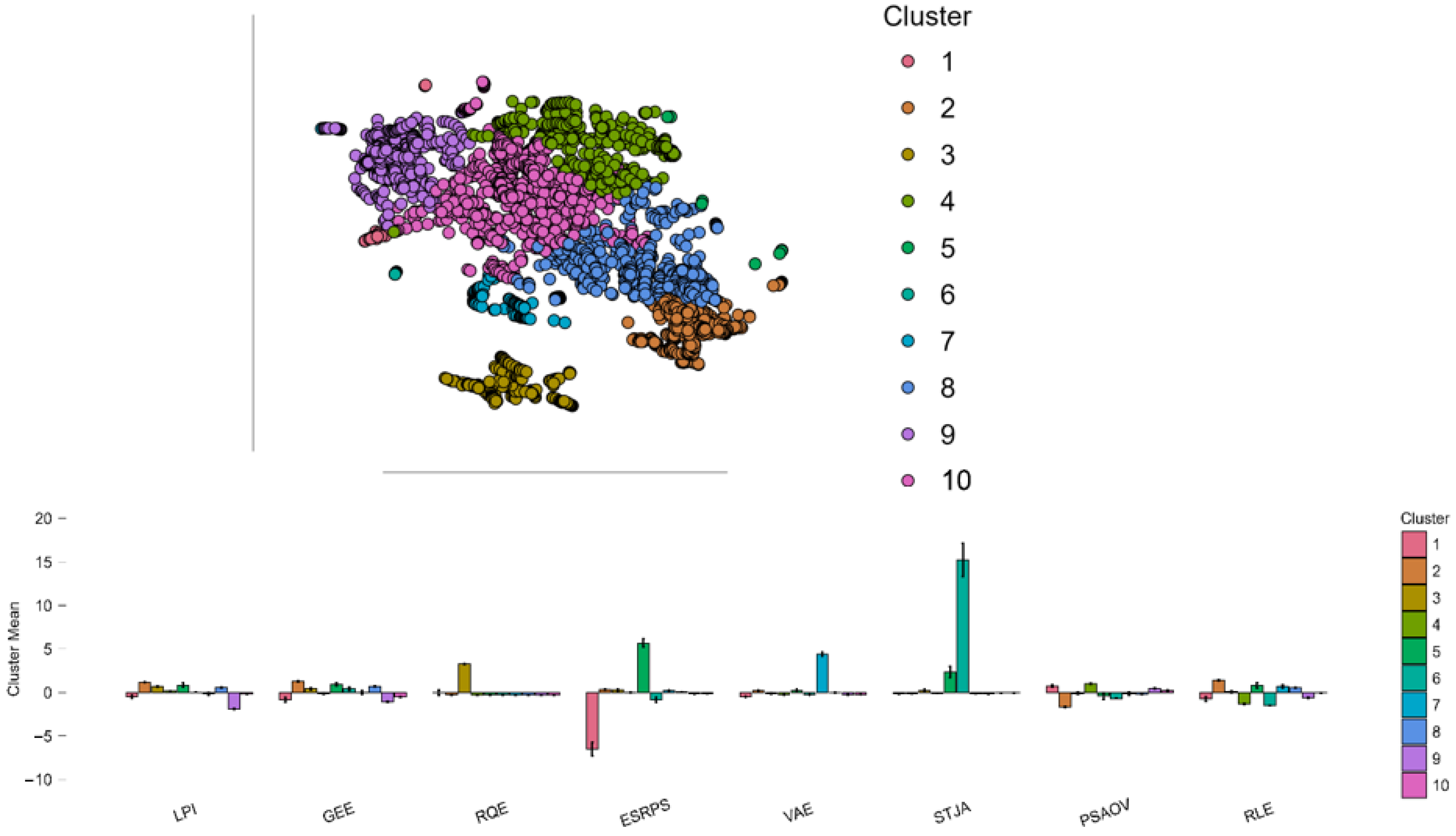

Comparison of Machine Learning Algorithms for Predicting Logistics Performance Based on Socio-Economic Factors.