Abstract

The U.S. municipal solid waste recycling rate has remained near 32% for two decades, placing the country 30th globally. In response, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has set a national goal of achieving a 50% recycling rate by 2030, yet concrete strategies for reaching this target remain limited. Persistent challenges—such as low public participation and inadequate dissemination of effective practices—highlight the potential importance of recycling education. This study has two aims. First, we assess federal investment in recycling education through the EPA’s Environmental Education Grants Program (1992–2023) using a large language model (LLM)-assisted text-mining approach to identify recycling-focused projects. Second, we examine the factors that shape state-level recycling rates, including policy, demographic, infrastructure, and education variables. Our results show that states with bottle bills—deposit–refund laws for beverage containers—and states with higher levels of educational attainment exhibit significantly higher recycling rates. By contrast, federal investments in recycling education, as measured through the grants program, were not statistically associated with state-level recycling performance. This study introduces a novel analytic approach for evaluating how policy and educational factors contribute to state-level recycling outcomes and to national recycling performance.

1. Introduction

Over the past two decades, the U.S. municipal-solid-waste (MSW) recycling rate has been stagnant around 32 percent [1], placing the country 30th worldwide on the Waste Recovery Rate indicator of the 2024 Environmental Performance Index [2]. To increase the recycling rate and support the transition toward a circular economy, the EPA has set a National Recycling Goal of boosting the rate to 50 percent by 2030 [3,4]. Achieving this objective will require modernization of collection systems, infrastructure, and information dissemination on recycling, Yet, current federal approaches to recycling remain largely programmatic and voluntary: the National Recycling Strategy articulates broad priorities (education and outreach, infrastructure and markets, and improved data), but does not establish binding nationwide performance standards, extended producer responsibility (EPR) requirements for packaging, or harmonized labeling and material-acceptance rules [5]. As a result, U.S. recycling policy continues to be implemented through a patchwork of state and local programs with divergent collection systems, financing mechanisms, and resident guidance—conditions that empirical work links to persistent contamination, low collection rates, and public confusion [6]. This mismatch between ambitious national goals and the absence of coherent federal implementation tools constitutes a critical policy gap in the U.S. recycling system.

Scholars generally trace stagnant U.S. recycling rates to limited public participation and insufficient diffusion of effective practices [7,8]. As part of public awareness activities, recycling education is widely recognized as a critical tool for promoting sustainable waste management. Research consistently highlights that public awareness and education serves as fundamental drivers for increasing recycling participation. For instance, Barr [9] and Viscusi et al. [7] emphasize that knowledge dissemination can help bridge the gap between environmental concern and concrete action by improving individuals’ understanding of how to recycle and why it matters. Schultz [10] also underscores the value of education in reinforcing the connection between environmental attitudes and everyday behaviors, even though prior research shows that environmental values do not consistently translate into pro-environmental actions [11,12,13].

Educational programs have demonstrated varying degrees of success in altering recycling behavior. A notable example is the study of 89 primary schools in Castilla-La Mancha, Spain, which assessed 20,710 students’ recycling practices and found that targeted instruction in glass recycling significantly improved students’ recycling attitudes and practices [14]. Similarly, Gamberini et al. [15] observed measurable improvements in waste separation behaviors in Italian communities following multimedia and in-school educational campaigns. Despite its importance, research remains limited in explaining how education is connected to broader recycling performance. Existing studies primarily rely on household surveys or evaluate specific educational interventions, rather than considering public education funding as a systemic driver of recycling performance. In addition, regulatory recycling policies like deposit-refund systems (i.e., bottle bills) are widely recognized as key mechanisms for higher recycling rates [16], yet no studies have empirically examined how these policy tools and federal investment into recycling and waste education relate to recycling performance, particularly within the U.S. context. Many studies conceptually track policy changes, and no studies included recycling education funding flows as an explanatory variable for cross-state recycling performance.

To address this research gap, our study first aims to explore to what extent recycling and waste management-focused education has been funded by federal government. Secondly, this research examines what factors drive state-level recycling performance that in turn contribute to the national recycling performance. For the first research purpose, we analyze the U.S. EPA’s Environmental Education (EE) Grants Program using a large language model (LLM)–assisted text mining to identify projects centered on recycling and waste management education. Since its inception, the program has awarded 3954 grants totaling approximately $95 million [17]. Second, we focus on bottle bills as an enabling policy environment for high recycling performance. With the policy factor, we add recycling education funding, other state-level infrastructure, and demographic factors to evaluate its association with overall recycling rates.

Our analysis shows that recycling and waste management education has not been substantially funded, while projects addressing biodiversity, ecosystem health, species protection, water, and general environmental literacy have received a much larger share of support. Funding distribution has also been geographically uneven, with California receiving the most support, while states such as South Carolina and South Dakota have attracted very limited funding. However, this uneven distribution of educational grants was not associated with actual differences in recycling performance across states.

From our regression analysis of state-level recycling performance, we found that states with bottle bills and those with a higher number of Superfund sites were more likely to exhibit higher recycling rates. These results underscore the importance of state-level, incentive-based regulatory policies that enhance recycling performance by altering the financial motivations underlying container return behavior. In contrast, federal investments in recycling education were not associated with state recycling rates, suggesting that policy structures and historical pollution burdens play a more substantial role than education alone in shaping recycling outcomes. More broadly, this study introduces a novel analytic approach for evaluating how policy and educational factors contribute to state-level recycling rates and, in turn, to national recycling performance.

2. Literature Review

- (1)

- US Recycling Rates

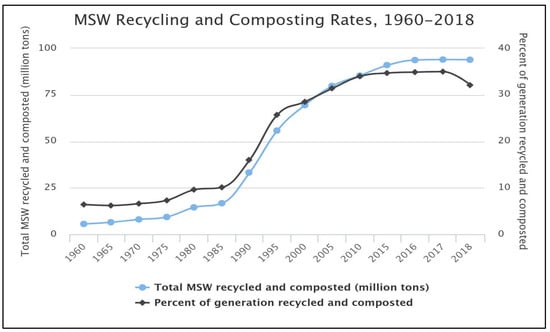

The United States’ recycling and composting rate of municipal solid waste is about 32.1%, which has remained relatively flat since 2012 as shown in Figure 1 [1,4]. The recycling rate by materials varies. For instance, plastics show a low recycling rate, and in 2018 only about 8.7% of plastics were recycled, while roughly 75.6% were sent to landfills [18,19].

Figure 1.

U.S. recycling rates from 1960 to 2018 [1].

In contrast, many European Union (EU) countries achieve much higher municipal waste recycling and composting rates, with about 48% of municipal waste recycled or composted [20]. Several developed nations far surpass this benchmark: Germany (56.8%), Austria (53.8%), and Republic of Korea (53.7%). These nations have shown strong policy directives at the national level like deposit refund scheme(s) for packaging (bottle bills that reimburse consumers for returning beverage containers) or extended producer responsibility which require producers to manage the environmental impacts of products [21].

By comparison, the U.S. records one of the lowest recycling rates among OECD peers, particularly for plastics, where U.S. performance lags significantly [19]. In response, the U.S. has introduced new policy initiatives, including its first national recycling goal, which seeks to raise the recycling rate to 50% by 2030 through modernization of collection systems and infrastructure [3,22,23,24]. However, before 2020, the U.S. lacks a national recycling framework, leaving thousands of municipalities to independently design systems. Studies describe this as a “governance patchwork” that limits coordination and innovation [5]. Prior research further notes that US recycling is fragmented and inconsistent, in part due to decentralized governance arrangements without a central policy direction [6]. This fragmentation contributes to low investment in infrastructure, including materials recovery facilities (MRFs), constraining the ability to process diverse or contaminated materials [16].

- (2)

- Deposit-refund Systems (Bottle Bills)

Policies promoting recycling, particularly deposit–refund systems, have proven highly effective in the United States. Policy evaluations consistently show that states with bottle bills achieve return and recycling rates between 60 and 90%, compared with 20–40% in non-deposit states [25]. By placing a small refundable deposit on beverage containers, these systems create direct economic incentives for consumers to return bottles and cans, substantially reducing litter, increasing material recovery, and improving the supply of high-quality recyclables. Deposit levels are typically set at 5 cents across most states, with Michigan’s 10-cent deposit and Maine’s variable 5–15 cent structure as notable exceptions Ten U.S. states—California, Connecticut, Hawaii, Iowa, Maine, Massachusetts, Michigan, New York, Oregon, and Vermont—along with Guam, maintain active deposit–refund systems [26].

Beyond improving recycling performance, bottle bills contribute to broader environmental and economic objectives. They generate clean, high-value PET, aluminum, and glass feedstocks for circular manufacturing, reduce contamination, and increase resilience to market disruptions in recycled materials [27]. Several scholars note that their behavioral effectiveness stems from simplicity, transparency, and the immediacy of financial reward, which lower participation barriers and encourage durable recycling habits [25]. Moreover, bottle bills can complement other state-level interventions—such as extended producer responsibility (EPR)—by stabilizing material flows and supporting municipal recycling systems [28]. As states reassess recycling strategies amid persistently low national recycling rates, deposit–refund systems remain one of the most consistently validated mechanisms for delivering measurable performance gains.

- (3)

- Trends in Recycling Education

Environmental education in general can foster a deeper appreciation of nature’s intrinsic value while cultivating a sense of responsibility to protect it. By enhancing awareness of the ecological consequences of overconsumption and waste, education can encourage behaviors that prioritize maximizing material use and minimizing the culture of disposability [29].

Over the past few decades, recycling education has undergone substantial development, becoming a critical mechanism for fostering pro-environmental behavior and supporting the transition to a circular economy. Early educational efforts focused on raising awareness of environmental issues, often within the broader scope of environmental education. Over time, the pedagogical focus has shifted toward behavior-specific programs that target recycling practices through formal and informal education channels [30,31]. In particular, school-based recycling education has become a vital strategy in shaping lifelong environmental behavior, with curricula now integrating both theoretical knowledge and hands-on learning experiences.

One prominent trend in recycling education is the increasing use of experiential learning to engage students more deeply in sustainability practices. Research has shown that interventions combining instruction with active participation, such as school recycling campaigns and student-led waste audits, are more effective in influencing attitudes and behavior than passive forms of education [32,33]. For example, a study by Vicente-Molina et al. [34] found that university students exposed to practical recycling opportunities demonstrated higher recycling intentions and behaviors, especially when coupled with strong institutional norms and peer influences. Similarly, integrating recycling content into science and social studies curricula at the K–12 level has been shown to improve both knowledge and self-reported pro-environmental behavior [35].

Despite these advancements, several challenges remain. One of the most persistent gaps is the absence of macro-level research examining whether and how public investments in environmental education contribute to improved recycling performance. Existing research on recycling education largely examines behavior at the household or municipal level, focusing on informational campaigns, normative messaging, or individual knowledge clarity often using digitalized games [36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43]. In these studies, “education” is operationalized as exposure to outreach programs or self-reported understanding of local recycling rules [41,42]. In contrast, our approach conceptualizes education as a structural, system-level determinant of recycling outcomes. By using national education funding as a proxy for institutional educational capacity, we capture broader forms of public literacy, cognitive skills, and government ability to disseminate environmental information—factors that are not measured in household- or municipality-focused studies. This macro-level operationalization of education represents a novel contribution to the recycling-policy literature, enabling analysis of how long-term national investment in education systems relates to recycling performance across jurisdictions.

- (4)

- EPA’s Environmental Education Grants Program

The longstanding U.S. EPA Environmental Education (EE) Grants Program provided stable funding for environmental education from its inception in 1992 until its termination in 2023 under the Trump administration [44]. Despite its long history, there is no dedicated scholarly review evaluating its cumulative impacts or synthesizing prior research on the program. Existing documents offer only partial coverage. Early assessments, such as the National Environmental Education Advisory Council’s report to Congress, describe the EPA’s implementation of the National Environmental Education Act but do not systematically evaluate EE grant outcomes [45].

Subsequent federal performance assessments—most notably the Office of Management and Budget’s review—explicitly noted that the program lacked independent, high-quality evaluations of sufficient scope to assess its long-term effectiveness [46]. More recently, the EPA Office of Inspector General concluded that the agency cannot determine the results or benefits of its EE grants due to insufficient outcome data and inconsistent reporting systems [47]. Although the EPA continues to publish annual summaries of grant awards, no contemporary study evaluates the Environmental Education Grants Program as a federal policy instrument or examines whether variation in state-level funding is associated with measurable environmental outcomes. This gap underscores the need for an analysis of EE grants program, and its relationship with environmental outcomes like recycling rates.

3. Data and Methods

- (1)

- EPA Environmental Education Grants Data

In this study, we utilized the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) Environmental Education (EE) Grants database, established under the Environmental Education Grants Program [44]. The program solicited applications from eligible entities to support projects that would advance environmental awareness, foster stewardship, and cultivate the competencies required for informed environmental actions. It provided financial resources to initiatives that developed, demonstrated, or disseminated innovative environmental education practices, methods, and techniques. Since its start in 1992, the program distributed between $2 million and $3.5 million annually, ultimately supporting 3964 projects nationwide until its formal termination in November 2023. The analysis of the distribution of EE grants by issue area, which was double counted, shows that the largest shares supported projects on general environmental literacy (27%), water (26%), and biodiversity, ecosystems, habitats, and species (20% projects). In contrast, only a small proportion of projects addressed environmental education needs concerning solid waste, recycling, and redevelopment (6%), as well as soil and agriculture, including composting (4%).

To examine trends in recycling and waste management education funding across time and states, we employed a large language model (LLM)–assisted text-mining procedure to improve the consistency of project identification. The LLM was used to read and interpret project descriptions from the EPA Environmental Education Grants database and provide an initial classification of whether each grant involved (a) waste-related content and (b) educational activities.

In the first stage, we identified candidate projects using waste-related terms such as “recycling,” “waste,” “solid waste,” “landfill,” “composting,” “hazardous waste,” and “toxic waste.” The LLM assisted in determining whether waste represented the project’s primary focus rather than a secondary reference within broader environmental education efforts. For instance, projects that mentioned waste only in the context of general environmental awareness or community clean-up related to non-point pollution were excluded from the initial set of 493 projects. In the second stage, we refined the dataset using education-oriented keywords (“K–12,” “curriculum,” “hands-on,” “training,” “experiential learning,” “field trip”) in combination with the LLM’s assessment of whether the project description included an explicit educational component.

To validate classification accuracy, we manually coded a stratified sample consisting of 63 recycling-education projects (15% of identified positives) and 176 non-recycling projects (5% of the remaining grants), yielding 239 manually reviewed cases. Agreement between the manual and LLM-assisted coding was 92%, and any misclassified projects were corrected before constructing the final dataset [48,49,50].

Using this validated set of recycling and waste management education grants, we examined state-level patterns by analyzing the number of such projects awarded, total funding allocated, and variation in state recycling performance. In the next section, we provide an overview of environmental education grants and present trends in recycling education funding.

- (2)

- Data and Variables for Regression Analysis

On the other hand, we employed a multivariate regression analysis to examine the role of recycling education on state recycling rates. The dependent variable was state recycling rate, based on Eunomia’s state-by-state assessment of recycling performance for packaged products (glass bottles and jars, aluminum cans, and steel cans), excluding cardboard, boxboard, plastic films, and flexible plastics [51]. Recycling rates ranged from a low of 2% in West Virginia to a high of 65% in Maine.

One of our key independent variables was the presence of a bottle bill. Because packaging redemption is most affected by bottle returns [52,53], we included an indicator for whether a state had enacted a bottle bill. Ten U.S. states—California, Connecticut, Hawaii, Iowa, Maine, Massachusetts, Michigan, New York, Oregon, and Vermont—have adopted such laws Accordingly, we coded the ten bottle-bill states as 1 and all others as 0. We also included the total amount of EPA Environmental Education (EE) grants awarded for recycling in each state as an additional independent variable.

To account for differences in recycling and waste management infrastructure, we included several infrastructure-related variables. These comprised the number of Superfund sites, obtained from the U.S. EPA’s National Priorities List [1], the number and total capacity of landfill sites [3], and the number of recycling facilities. Data on recycling facilities were compiled from state and municipal waste agencies, environmental directories, and publicly available MRF (Materials Recovery Facility) databases, and further enriched with geospatial verification from Google Maps.

Finally, we controlled demographic and economic characteristics at the state level. State populations were incorporated as proxies for both the scale of waste generation and resources available for waste management and recycling programs, using data from the U.S. Census Bureau. The share of residents with a bachelor’s degree or higher was controlled, as prior studies have shown that young generation and higher levels of educational attainment are positively associated with recycling behavior [54]. Both data also draw from the U.S. Census Bureau. The descriptive statistics of variables are seen in Table 1 below. Multicollinearity diagnostics showed no concern (all VIF < 5), and residual plots confirmed normality, homoscedasticity, and linearity. Cook’s distance values were below 1, and the Durbin–Watson statistic (2.082) indicated no autocorrelation. Thus, the regression assumptions were reasonably satisfied.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of variables and data sources.

4. Results

- (1)

- Analysis of Environmental Education Grants

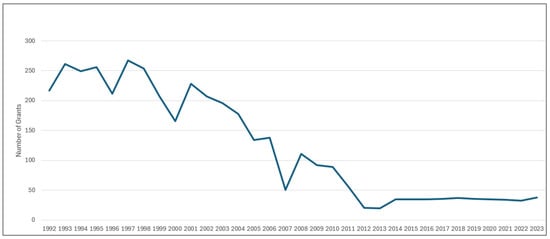

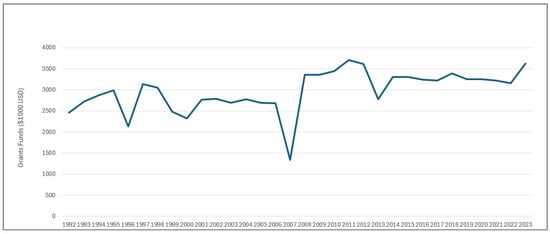

Between 1992 and 2004, at the first stage when the U.S. national recycling rate had grown fast, on average 223 environmental education grants were awarded per year. Beginning in 2005, however, the number of grants declined, reaching a low of just 20 projects in 2013 (Figure 2). Over the past decade, the number of projects averaged 35 projects per year, but the average grant size rose substantially, reaching $3.3 million per year (Figure 3). In terms of recycling education during the same period, only 13 grants were awarded, with an average of $90,077, showing 9.46% of the total amounts funded per year at maximum (Table 2). These findings show that public spending on recycling education has not kept pace with rising societal concern about packaging waste or with regulatory actions designed to increase recycling [55].

Figure 2.

Number of environmental education grants awarded by year (1992–2023).

Figure 3.

Amount of environmental education grants awarded by year (1992–2023).

Table 2.

Number and amount of grants for recycling projects, as well as the percentage of recycling education per year from 2014 to 2023.

- (2)

- Analysis of Recycling and Waste Management Education Funding

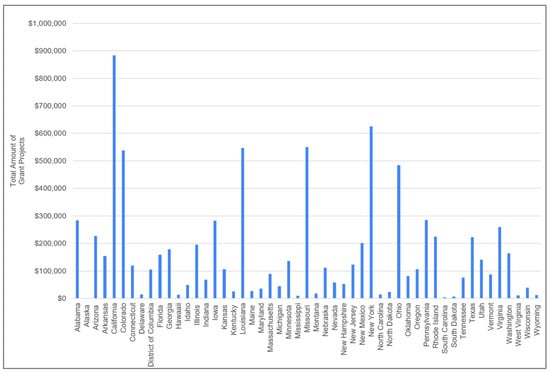

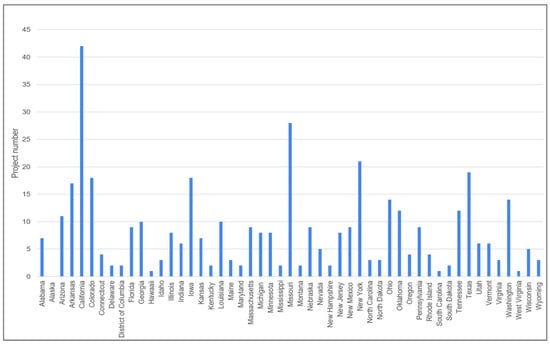

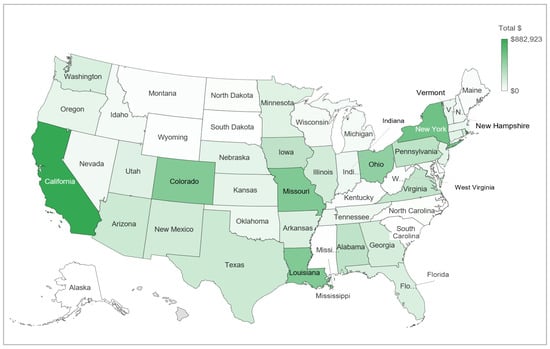

Our analysis found 421 recycling or composting projects, totaling $8,281,557 in funding. California received the greatest funding, totaling $882,923. The lowest funding by grant amount was Alaska, with no funding, while South Carolina received $5000, and South Dakota received $6500 (Figure 4). We also surveyed the number of projects characterized as hands-on, which numbered 84. Moreover, the number of projects focusing on curriculum development was 110. Figure 5 presents the total project funding by the state.

Figure 4.

Total amount of grant project funds by state.

Figure 5.

Total number of grant projects by state.

We also examined the distribution of projects by state, finding an average of 8 projects per state. California received the greatest number of projects, with 42 funded initiatives, whereas Hawaii, South Carolina, and West Virginia each received only one project (Figure 5). Figure 6 illustrates the total number of projects by state, while Figure 6 presents state-by-state variation in total grant funding, displayed in a U.S. map format.

Figure 6.

State-by-state variation in the amount of grant funds by state.

- (3)

- Regression Analysis of Antecedents for State Recycling Rate

In the regression analysis, we obtained an adjusted R2 of 0.702, suggesting that the model accounts for a considerable portion of variation in state recycling rates (Table 3). The amount of recycling grant funding and the number of recycling facilities did not exhibit significant relationships with overall state recycling rates. By contrast, states that have adopted bottle bills demonstrated significantly higher recycling rates (t = 8.290, p < 0.01), underscoring the role of container deposit legislation in increasing redemption rates and thereby enhancing recycling performance. Higher levels of educational attainment were also positively associated with recycling rates (t = 3.109, p < 0.01), aligning with prior research suggesting that more educated populations are more likely to engage in pro-environmental behaviors, including recycling. In addition, the number of Superfund sites was associated with recycling rates (t = 2.573, p < 0.05), suggesting that states with greater exposure to toxic waste challenges may exhibit stronger public and institutional commitment to waste management. For example, New Jersey which has the largest number of Superfund sites reported a high recycling rate of 39%, whereas Nevada and Wyoming with very few Superfund sites reported comparatively low recycling rates of 12%.

Table 3.

Regression outcomes of factors that could affect state recycling rates.

5. Discussion

From the analysis of EE grants, we find that in the early period of 1992 to 2005, when national recycling performance had increased rapidly, many grants were around $5000, on a very small scale, mainly focusing on Earth Day events, as well as extracurricular workshops and activities to introduce recycling and waste reduction needs. Students were primarily in a passive role, receiving information. This tendency likely reflects the short-term, informational scope of many small awards. However, because our dataset does not include evaluation results, we refrain from interpreting these patterns as indicators of project effectiveness. As the grant amount increased from 2014 to 2023, grant projects focused on empowering students to not only learn conservation practices but also connect with communities as strong advocates for conservation and sustainable living. Also, we find that large grants include an activity of creating professional development programs for teachers. For instance, EdAdvance, a local nonprofit environmental group in Connecticut, received $100,000 to develop a training program for teachers. This program aims to help teachers understand how to design a pedagogy that integrates agricultural and environmental education curricula into their classrooms.

Second, we find that many recycling education projects focus on local waste issues, which can be effective in capturing students’ attention. However, these projects often remain limited in providing hands-on learning opportunities, such as visits to recycling facilities or engagement with disadvantaged communities to promote recycling awareness. Approximately 20% of funded projects incorporated hands-on activities. However, these were often one-time events, such as retreats or team-building exercises, rather than ongoing educational initiatives involving sustained experiential learning that could be much needed [56]. Moreover, because recycling education can help bridge the gap between the public’s willingness to engage in pro-environmental behavior and recycling facilities’ need for stable, high-quality material flows, the content of what is taught becomes critical [57]. In this vein, recycling education should be framed within the broader concept of pollution prevention rather than pollution control, which focuses on managing pollution only after it has been generated. Emphasizing pollution prevention allows education programs to provide practical guidance on how to recycle effectively and how individual actions contribute to reducing waste at the source [58]. While some projects highlight the 3Rs waste management hierarchy (i.e., Reduce, Reuse, and Recycle), their prevalence remains relatively low. Greater emphasis is needed on pollution prevention, particularly in highlighting the connections between waste reduction, natural resource conservation, and greenhouse gas emissions.

Third, findings from our regression analysis underscore the critical role of incentives and regulatory mechanisms—particularly bottle bills—in shaping recycling performance. States that have adopted deposit–refund systems consistently demonstrate markedly higher recycling rates, reflecting the power of direct financial incentives to influence consumer behavior and increase material recovery. These programs not only drive higher return rates but also improve the quality of collected materials, reduce contamination, and stabilize recycling streams, thereby enhancing the overall efficiency of state recycling systems. The strong and persistent association between bottle bill adoption and superior recycling outcomes observed in our analysis aligns with decades of empirical evidence showing that regulatory incentives can effectively motivate pro-environmental behavior and overcome participation barriers [59]. Combined, these results highlight that policy design, especially the inclusion of clear, enforceable, and incentive-based mechanisms, remains central to improving recycling system performance in the United States.

Moreover, we also found that states with a higher proportion of residents holding a college degree or higher tend to have higher recycling rates. This suggests that greater educational attainment may foster more environmentally responsible behaviors, thereby positively influencing recycling outcomes [34]. In this regard, expanding recycling education and outreach programs could further strengthen overall recycling performance. Moreover, the presence of Superfund sites may heighten community awareness of waste-related risks, toxic legacies, and long-term remediation costs—issues that could be more effectively communicated to the public through education initiatives. The wide variance in state recycling rates also raises important questions about how to reduce uneven performance across states. This disparity is a constant challenge often observed in environmental governance and one that underscores the risks of fragmented or inoperative federalism [52].

Building on the findings of this study, future research could further examine the role of other policy instruments—such as extended producer responsibility (EPR) and Pay-as-You-Throw (PAYT) systems—and their potential synergies with recycling education. It would also be valuable to investigate the barriers prohibiting policy adoption in states without bottle bills, particularly given the slow diffusion of such legislation across the United States. In addition, future studies could explore whether, and to what extent, educational interventions promote recycling behaviors across differing institutional contexts, curricular frameworks, and sociocultural settings, and how these outcomes compare with countries that demonstrate high recycling performance. Such experimental or quasi-experimental research would offer practical insights for strengthening U.S. recycling education strategies and enhancing the design of policy–education integration.

6. Policy Suggestions

Given substantial and long-standing evidence that bottle bills increase container return rates and overall recycling performance, federal and state policymakers could encourage broader adoption in states that have not yet implemented such legislation. Federal guidance—such as model laws, best-practice frameworks, or incentive-based grants—could help reduce the administrative and political barriers that have historically slowed policy diffusion. Prior scholarship on environmental policy diffusion shows that supportive federal signals and financial incentives often accelerate adoption of state-level innovations [60]. For states such as Virginia, recent proposals (e.g., HB826) offer detailed templates grounded in long-standing bottle-bill models, potentially shortening the learning curve and helping policymakers avoid early design pitfalls [61]. In this context, targeted recycling education could broaden public understanding of the environmental and economic benefits of deposit–refund systems, thereby increasing political support for adoption.

Several bottle-bill states have modernized and expanded their programs to respond to evolving beverage markets and recycling needs. Michigan illustrates both the challenges and opportunities of such updates. Once a national leader with redemption rates approaching 95%, Michigan’s return rate declined to about 70% in 2024 as its deposit system—largely unchanged since the 1990s—struggled to keep pace with shifts in the beverage market and consumer behavior. The state still relies heavily on retailer-based returns and lacks dedicated redemption centers used in other states to increase convenience. Recent efforts to expand the list of eligible containers, including additional beverage types such as wine bottles, demonstrate how existing systems can be modernized to improve performance and material recovery [62].

Federal support for state-level regulatory mechanisms promoting recycling rates should be incorporated into future updates of the U.S. 2030 National Recycling Strategy. For instance, the modernized approach of bottle bills, such as updating deposit values, expanding container coverage, and improving redemption infrastructure, could be guided to states without bottle bills. Moreover, integrating strengthened deposit–refund systems with a more explicit role for recycling education would help align behavioral, infrastructural, and regulatory levers. Educational initiatives can cultivate public understanding of why deposit policies matter, increase willingness to return containers, and build broader political support for adopting or modernizing bottle bills. Embedding these mutually reinforcing strategies into the national framework would create a more coherent, comprehensive approach to achieving a 50% recycling rate and advancing a circular economy.

7. Conclusions

Our research contributes to the literature on recycling and sustainable waste management in three key ways. First, it reconceptualizes recycling education not merely as an awareness-raising activity but as a policy instrument with potential influence on recycling performance. By situating educational initiatives within the broader framework of the U.S. National Recycling Strategy, the study advances understanding of how behavioral, infrastructural, and regulatory factors interact to shape recycling outcomes. Second, drawing on an original dataset of more than three decades of U.S. EPA Environmental Education Grant Program records (1992–2023), the study offers the first empirical assessment of the extent to which federal investments in recycling education have supported state-level recycling performance. Although the analysis did not identify a statistically significant relationship between EE grant funding and state recycling rates, the results highlight persistent gaps in how recycling education is integrated into broader waste management systems and point to opportunities for more systematic approaches to educational design, implementation, and evaluation. Finally, by reaffirming the policy relevance of bottle bills, the study provides timely insights for the U.S. EPA and state governments working toward the national goal of achieving a 50% recycling rate by 2030. The findings underscore the importance of regulatory mechanisms that directly shape citizen behavior and illustrate how educational initiatives can deepen public understanding of waste management and foster policy support. Collectively, these contributions emphasize the need to reconceptualize waste as a resource and to equip current and future generations to participate actively in building a circular economy.

Author Contributions

C.B.O. contributed to data collection and analysis and to the writing of the manuscript. Y.K. contributed to the conceptual design of the research, supervised the data collection and analysis, and was involved in writing and editing the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

No funding was received to support the conduct of this research.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data that supported the findings derived from the EPA EE grants database (https://www.epa.gov/education/grants (accessed on 5 October 2025)), US EPA Landfill database (https://www.epa.gov/lmop/lmop-landfill-and-project-database (accessed on 5 October 2025)), US EPA NPL Sites-by State (https://www.epa.gov/superfund/national-priorities-list-npl-sites-state (accessed on 5 October 2025)), and US Census Bureau https://www.census.gov/data.html (accessed on 5 October 2025).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper. All research activities were conducted in accordance with relevant institutional and ethical guidelines.

References

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. National Overview: Facts and Figures on Materials, Waste and Recycling. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/facts-and-figures-about-materials-waste-and-recycling (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- Yale Center for Environmental Law Policy. Waste Recovery Rate indicator. In 2024 Environmental Performance Index; 2024; Available online: https://epi.yale.edu/measure/2024/WRR (accessed on 5 October 2025).

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. U.S. National Recycling Goal. 11 February 2025. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/circulareconomy/us-national-recycling-goal (accessed on 3 September 2025).

- Kim, Y.; Oh, C.B.; Oh, S.C.; Sivanandan, T.; Small, J.M. Identifying the determinants of recycling rates in the US: A multi-level analysis. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- US Government Accountability Office (GAO). Recycling: Building on Existing Federal Efforts Could Help Address Cross-Cutting Challenges; GAO-21-87; Washington, DC, USA, 2020. Available online: https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-21-87 (accessed on 3 September 2025).

- Blanco, C.; Spanbauer, C.; Stienecker, S. America’s broken recycling system. CMR Insights. 2023, 65. Available online: https://cmr.berkeley.edu/2023/05/america-s-broken-recycling-system (accessed on 21 September 2025).

- Viscusi, W.K.; Huber, J.; Bell, J. Promoting recycling: Private values, social norms, and economic incentives. Am. Econ. Rev. 2011, 101, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, K.; Kim, Y. Problems of the US recycling programs: What experienced recycling program managers tell. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barr, S. Factors influencing environmental attitudes and behaviors. Environ. Behav. 2007, 39, 435–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, P.W. Conservation means behavior. Conserv. Biol. 2011, 25, 1080–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, P.C. Toward a coherent theory of environmentally significant behavior. J. Soc. Issues 2000, 56, 407–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thøgersen, J. Norms for environmentally responsible behavior: An extended taxonomy. J. Environ. Psychol. 2006, 26, 247–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar-Jurado, M.Á.; Gil-Madrona, P.; Ortega-Dato, J.F.; Zamorano-García, D. Effects of an educational glass-recycling program against environmental pollution in Spain. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 5108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamberini, R.; Del Buono, D.; Lolli, F.; Rimini, B. Municipal solid waste management: Identification and analysis of engineering indexes representing demand and costs generated in virtuous Italian communities. Waste Manag. 2013, 33, 2532–2540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine. Municipal Solid Waste Recycling in the United States: Analysis of Current and Alternative Approaches; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- US. Environmental Protection Agency. National Recycling Strategy. 2025. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/circulareconomy/national-recycling-strategy (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Thomas, D.S.; Kneifel, J.D.; Butry, D.T. The U.S. Plastics Recycling Economy: Current State, Challenges, and Opportunities. National Institute of Standards and Technology, Gaithersburg, MD, NIST Advanced Manufacturing Series (AMS) 100-64. 2024. Available online: https://www.nist.gov/publications/us-plastics-recycling-economy-current-state-challenges-and-opportunities (accessed on 22 August 2025).

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. OECD Environmental Performance Reviews: United States 2023; OECD Publishing, 2023. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/oecd-environmental-performance-reviews-united-states-2023_47675117-en.html (accessed on 14 March 2025).

- Eurostat. Municipal Waste Statistics: Statistics Explained; European Commission, 2024; Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php/Municipal_waste_statistics (accessed on 23 August 2025).

- Gilles, R.; Jones, P.; Papineschi, J.; Hogg, D. Recycling: Who Really Leads the World? Eunomia and the European Environmental Bureau: Bristol, UK, 2017; pp. 1–39. Available online: https://eeb.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Recycling_who-really-leads-the-world-REPORT.pdf (accessed on 7 September 2025).

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. EPA Releases Bold National Strategy to Transform Recycling in America. 2021. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/newsreleases/epa-releases-bold-national-strategy-transform-recycling-america (accessed on 7 May 2025).

- Quinn, M. EPA’s 2030 Recycling Strategy Turns Focus to Circular Economy and Environmental Justice; WASTEDIVE, 2021; Available online: https://www.wastedive.com/news/epa-national-recycling-strategy-circular-economy-takeaways/610076/ (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. An assessment of the US Recycling System: Financial Estimates to Modernize Material Recovery Infrastructure. EPA-530-R-24-010. 2024. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/system/files/documents/2024-12/financial_assessment_of_us_recycling_system_infrastructure.pdf (accessed on 7 September 2025).

- Picuno, C.; Gerassimidou, S.; You, W.; Martin, O.; Iacovidou, E. The potential of Deposit Refund Systems in closing the plastic beverage bottle loop: A review. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2025, 212, 107962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Conference of State Legislatures (NCSL). State Beverage Container Deposit Laws. 2025. Available online: https://www.ncsl.org/environment-and-natural-resources/state-beverage-container-deposit-laws (accessed on 21 September 2025).

- Container Recycling Institute. BC Case Study: The Environmental and Economic Performance of Beverage Container Reuse and Recycling in British Columbia, Canada; Container Recycling Institute: Culver City, CA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Walls, M. Deposit-Refund Systems in Practice and Theory. Resources for the Future Discussion Paper No. 11–47. 2011. Available online: https://media.rff.org/archive/files/sharepoint/WorkImages/Download/RFF-DP-11-47.pdf (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- Nigbur, D.; Lyons, E.; Uzzell, D. Attitudes, norms, identity and environmental behavior: Using an expanded theory of planned behavior to predict participation in a curbside recycling program. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2010, 49, 259–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kollmuss, A.; Agyeman, J. Mind the gap: Why do people act environmentally and what are the barriers to pro-environmental behavior? Environ. Educ. Res. 2002, 8, 239–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardoin, N.M.; Clark, C.; Kelsey, E. An exploration of future trends in environmental education research. Environ. Educ. Res. 2013, 19, 499–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, J.C.; Waliczek, T.M.; Zajicek, J.M. Relationship between environmental knowledge and environmental attitude of high school students. J. Environ. Educ. 1999, 30, 17–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Leeuw, A.; Valois, P.; Ajzen, I.; Schmidt, P. Using the theory of planned behavior to identify key beliefs underlying pro-environmental behavior in high-school students: Implications for educational interventions. J. Environ. Psychol. 2015, 42, 128–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicente-Molina, M.A.; Fernández-Sainz, A.; Izagirre-Olaizola, J. Environmental knowledge and other variables affecting pro-environmental behavior: Comparison of university students from emerging and advanced countries. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 61, 130–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zelezny, L.C. Educational interventions that improve environmental behaviors: A meta-analysis. J. Environ. Educ. 1999, 31, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geiger, S.M.; Dombois, C.; Funke, J. The role of environmental knowledge and attitudes in environmental behavior: Predictors for ecological behavior across cultures? Umweltpsychologie 2018, 22, 69–87. [Google Scholar]

- Barlett, P.F.; Chase, G.W. Sustainability on Campus: Stories and Strategies for Change; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Keramitsoglou, K.; Tsagarakis, K.P. Raising effective awareness for domestic water saving: Evidence from an environmental educational programme in Greece. Water Policy 2018, 13, 828–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudok, F.; Pigniczki-Kovács, E. Education for sustainability through gamification. Acta Cult. Paedagog. 2024, 3, 61–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakhan, C. The relationship between municipal waste diversion incentivization and recycling system performance. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2016, 106, 68–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidique, S.F.; Lupi, F.; Joshi, S.V. The effects of behavior and attitudes on drop-off recycling activities. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2010, 54, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seacat, J.D.; Boileau, N. Demographic and community-level predictors of recycling behavior: A statewide assessment. J. Environ. Psychol. 2018, 56, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wesley Schultz, P. Changing Behavior with Normative Feedback Interventions: A Field Experiment on Curbside Recycling. Basic Appl. Soc. Psychol. 1999, 21, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Environmental Protection agency. Environmental Education Grants: National statistics. June 2025. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/education/environmental-education-grants-national-statistics (accessed on 3 April 2025).

- National Environmental Education Advisory Council (NEEAC). Report to Congress: The Status of Environmental Education in the United States; U.S. Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Office of Management and Budget (OMB). Program Assessment Rating Tool (PART): EPA Environmental Education; Executive Office of the President: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- EPA Office of Inspector General. EPA Cannot Assess Results and Benefits of Its Environmental Education Programs; Report No. 16-P-0206; U.S. Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Krippendorff, K. Content Analysis: An Introduction to Its Methodology, 4th ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Neuendorf, K.A. The Content Analysis Guidebook, 2nd ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Grimmer, J.; Stewart, B.M. Text as data: The promise and pitfalls of automatic content analysis methods. Political Anal. 2013, 21, 267–297. [Google Scholar]

- Eunomia Research & Consulting. The 50 States of Recycling: A State-by-State Assessment of US Packaging Recycling Rates; Eunomia: New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Rabe, B.G. Racing to the top, the bottom, or the middle of the pack? The evolving state government role in environmental protection. In Environmental Policy, 12th ed.; Kraft, M.E., Rabe, B.G., Vig, N.J., Eds.; CQ Press: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Schnurr, R.E.J.; Roy, P.; Walker, T.R. Reducing marine pollution from single-use plastics (SUPs): A review of legislative and non-legislative interventions. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2018, 137, 157–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daoud, O.W.; Ahmed, V.; Alzaatreh, A.; Anane, C. The Impact of Socio-Economic Factors on Recycling Behavior and Waste Generation: Insights from a Diverse University Population in the UAE. Clean. Waste Syst. 2025, 11, 100266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Ruedy, D. Mushroom Packages: An Ecovative design approach in packaging industry. In Handbook of Engaged Sustainability; Dhiman, S., Marques, J., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Rogoff, M.J.; Ross, D.E. The future of recycling in the United States. Waste Manag. Res. 2016, 34, 181–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caulfield, C. Why Doesn’t Honolulu Recycle More? 2020. Available online: https://www.civilbeat.org/2020/07/why-doesnt-honolulu-recycle-more/ (accessed on 5 October 2025).

- Kirchherr, J.; Reike, D.; Hekkert, M. Conceptualizing the circular economy: An analysis of 114 definitions. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2017, 127, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zelezny, L.D.; Chua, P.; Aldrich, C. New ways of thinking about environmentalism: Elaborating on gender differences in environmentalism. J. Soc. Issues 2000, 56, 443–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konisky, D.M.; Woods, N.D. Environmental policy, federalism, and the Obama presidency. Publius J. Fed. 2016, 46, 366–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virginia General Assembly. HB826: Beverage Container Deposit and Redemption Program; Civil Penalties. 2022. Available online: https://www.vpap.org/bills/74990/HB826/ (accessed on 28 November 2025).

- Loria, K. Michigan’s Bottle Bill at a Crossroads. Recycling Institute, Inc. Available online: https://resource-recycling.com/recycling/2025/11/10/michigans-bottle-bill-at-a-crossroads/ (accessed on 26 November 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).