Abstract

Aircraft turnaround efficiency is a key determinant of the sustainability of air transport systems. Each stage of ground handling—passenger disembarkation, baggage handling, refuelling, and ancillary services—contributes to the total turnaround time, with direct implications for airport capacity, operating costs, and environmental performance. Using empirical records from ground operations, the study characterizes the duration and variability of individual activities and identifies the main process bottlenecks. Building on this evidence, a comparative PERT-COST protocol with explicit threshold rules (quantized billing steps for selected resources) is developed and applied across predefined scenarios (remote versus gate, day versus night, low versus high fuel uplift, with versus without a second baggage team) under both linear and threshold cost models. The protocol aligns with ITS-enabled decision support by mapping stochastic activity times to cost-of-crashing functions and by providing harmonized performance metrics: final time T, total cost ∑ΔC, and efficiency η (EUR/min). The results show that moderate time reductions are attainable at reasonable cost, whereas aggressive targets that lie below the structural minimum are infeasible under current constraints; gate stands reduce the attainable minimum time but increase the marginal price near the minimum, and night operations raise costs without improving that minimum. These findings delineate the most productive intervention range and inform operational choices consistent with sustainability objectives.

1. Introduction

The civil aviation sector is seeing growth in passenger transport—according to data published by the International Air Transport Association (IATA), international passenger traffic is on an upward trend [1]. ACI World–ICAO (Airports Council International (ACI) World and the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) forecasts indicate that by 2030, global passenger traffic may exceed 12 billion, and by 2042 it may reach as much as 19.5 billion [2]. The growing number of passengers is leading to an intensification of ground handling tasks. Ground handling is an integral part of the air transport system. It includes a set of logistical, administrative, and technical activities. This process is extremely important because it is responsible for preparing the aircraft for transport and servicing it after the flight. The ground handling market is expected to reach $83.8 billion by 2033 [3].

Increasing passenger traffic means that airports and companies responsible for ground handling services are focusing on finding solutions that enable the efficient use of resources. Current ground handling activities focus on two main areas. The first is activities aimed at sustainable development. The second area covers activities aimed at ensuring maximum throughput. Ground handling is an anthropotechnical system and therefore requires the involvement of technical and human resources. The difficulty in managing this process is also related to the phenomenon of delays—understood as the difference between the planned and actual departure/arrival of an aircraft. Delays require the appropriate redirection of resources so that the aircraft can carry out its planned transport tasks. The costs of delays can range from EUR 95 (5 min delay at the gate for an Airbus A320) to as much as EUR 1.366 (30 min delay at the gate for an Embraer 190) [4].

Ground handling should focus on improving its processes and acting in line with the concept of sustainable development. This requires considering human, technical, economic, and environmental factors. Ensuring high efficiency requires analyzing the duration and variability of individual activities and identifying bottlenecks in the process. Therefore, the main objective of this article is to present how empirical data can be used to optimize ground handling time, considering the above-mentioned aspects.

Methodologically, the paper contributes a comparative PERT-COST protocol with threshold rules, tailored to airport turnarounds. The protocol integrates stochastic activity times with cost-of-crashing functions and incorporates quantized billing thresholds (e.g., 900 s for stairs/jet-bridge tasks B/F), so that cost discontinuities are explicitly represented. We predefine a set of operational scenarios—remote vs. gate, day vs. night (night multiplier ), low vs. high fuel uplift (1000 vs. 4000 kg), and with vs. without a second baggage team—and assess both linear and threshold cost models. Comparative performance is reported in terms of the final time , total cost , and efficiency (EUR/min); infeasibility is identified when a target lies below the structural minimum implied by lower duration bounds and precedence constraints.

The structure of the article is as follows: Section 2 presents a review of the literature on ground handling issues, indicating a research gap; Section 3 presents a summary of activities carried out in the ground handling process on the airport apron; Section 4 describes the research methodology; Section 5 presents the results and discussion; and Section 6 is a summary.

2. Literature Review

Due to the research area under consideration, the review of the state of knowledge was divided into four main parts. The first part presented the issue of sustainable development, focusing on the aspect of energy consumption. The second part analyzed publications focusing on ground handling operations. The third part draws attention to the human factor. The fourth part identifies a research gap based on the considerations presented.

2.1. Energy Consumption in Ground Handling

A 2016 literature review by Ortega [5] identified all sources of energy and areas of energy use at airports. According to Gao et al. [6], ground support equipment (GSE) operations are one of the main factors responsible for energy consumption. Previous studies on energy consumption have focused on selected areas and equipment in ground support operations. Heß et al. [7] pointed out that heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC) accounts for 50% of the total energy consumption of electric airport buses. In the work of Boa et al. [8], it is noted that the electrification of the ground handling fleet has an impact on delays. Boa et al. [8] proposed a model for the operation of electric and fuel-air tractors using an Adaptive Large Neighbourhood Search (ALNS) algorithm, in which one of the criteria for scheduling fleet tasks was to minimize energy consumption. The use of an autonomous tractor powered by pure hydrogen (CHAT) to tow aircrafts could contribute to energy savings in the form of fuel oil at a level of 20–40 million tons per year [9]. The operation of ground support equipment and energy consumption also depend on the operations performed. Timmermans et al. [10] showed that electric GSE can be operated throughout the day, provided that there is no need to use them at night. Lower energy consumption in ground support vehicles can be achieved by reducing the idle speed [11]. At Copenhagen Airport, energy demand on the apron for service equipment is 2% and for Auxiliary Power Unit (APU) equipment is 5% [12].

Energy consumption is related not only to the method but above all to the number of devices involved. Computational experiments conducted by Volt et al. [13] indicate that a mathematical model can be used to predict the demand for trolleys and loaders needed for loading and unloading baggage. Romanenko et al. [14] used a fuzzy control algorithm based on singleton rules to analyze the efficiency of the baggage handling system and determine the minimum number of GSE devices. The improved iterative sequence method (iSIM) in [15] takes into account, first, the minimization of GSE waiting time before the start of operations and the minimization of aircraft turnaround time.

2.2. Operational Activities in the Ground Handling Process

Significantly more publications have been identified in the area of ground handling operations. An example is the multi-agent automated ground handling scheduling system [16], which uses the Temporal Sequential Single-Item auction (TeSSI) method. The problem of scheduling GSE tasks and routes [17,18,19], resource allocation [20,21], and vehicle service characteristics [22] has also been the subject of numerous studies. In the area of GSE route and equipment scheduling, the Sequence Iterative Method (SIM) [17], the Large Neighbourhood Search (LNS) method [18], and neural networks trained with reinforcement learning [19] are used. Zhu et al. [22] analyzed the characteristics of tanker and low-floor bus services using integer programming. The GSE resource allocation method presented by Andreatta et al. [20] is based on the Ground-service Resource Allocation Sequential Procedure (GRASP) heuristic. This allows for a 7.5% increase in ground handling efficiency. Kierzkowski and Kisiel [23] developed a logistics support model for a ground handling agent for the predicted traffic flow. A model for aircraft loading has also been developed that considers delays resulting from flight schedules, which can reduce loading times by up to 7% [24]. The main objective of the above research is to ensure aircraft punctuality, i.e., compliance with the flight schedule. Kierzkowski and Kisiel [25,26] used simulations to analyze the operational capacity of an airport after an initial delay.

The literature also includes works focusing on the assessment of airport performance. The method for assessing the efficiency of ground handling of multiple aircrafts, developed by Li et al. [27], is based on the analysis of data on key ground handling points. The work focuses on a matrix-based assessment of the efficiency of ground handling of multiple flights, enabling an increase in prediction accuracy to 87.63%. The quality of services provided is also an important element of operational activities. Aydın and Yörükoğlu [28] evaluated Turkish ground handling services (GHS) using the Neutrosophic MUL-TIMOORA method algorithm. At the same time, reference [29] presented a performance measurement system (PMS) that contributed to the introduction of new process segmentation and improved service quality at the airports studied.

2.3. The Human Factor in Ground Handling

The aircraft flight schedule affects the scheduling of ground handling tasks. Handling operators must make decisions in changing operating conditions. Yazgan et al. [30] classified ground handling personnel as one of the four most important risk factors for apron operations. The classification of risk factors in the above-mentioned group included 39 elements, such as improper personnel deployment, unreasonable actions, improperly performed tasks, and ground handling equipment failure. The risk of accidents in the context of ground handling personnel work was analyzed by Chikha and Skorupski [31]. In their work, they assessed the minimum level of operator training for which the risk of an accident is acceptable. On the other hand, the reliability of ground handling operators during the aircraft pushback process was assessed using the Systematic Human Error Reduction and Prediction Approach (SHERPA) [32]. The concept of managing fatigue among ground handling staff, considering physical and mental predispositions, was presented by Morais et al. [33]. The factors influencing task performance identified were working hours, shift work, night work, breaks, working conditions, and individual factors.

2.4. Identification of Research Gap

The ground handling process is a complex and dynamic process in which activities are carried out in series and/or sequentially. Despite numerous scientific studies in this area, there is still a lack of an approach focusing on the integration of technical, economic, and environmental factors. The strategic importance of the ground handling process means that it should be analyzed in a broader context.

This approach is possible using a tool known as PERT-COST (Program Evaluation and Review Technique Cost). PERT is a tool for scheduling, planning, and controlling the progress of complex projects. It allows for the identification of activities that are key to the timely completion of tasks. PERT is used to analyze the time required to complete production orders [34], minimize production time [35], and manage public transport vehicles [36]. This technique has also been used in areas related to ground handling by Makhloof et al. [37] and San Antonio et al. [38] used PERT to evaluate and improve the efficiency of the service process. Previous analyses of the ground handling process have largely focused on the time and cost of providing services. There is a lack of research focusing on integrating these three elements: cost, time, and sustainability. The following article addresses this identified research gap. A key element of this article is the analysis of ground handling process scenarios, including answering the following questions: How does the configuration of stations affect the total cost of the ground handling process? Does the time of day of the ground handling process affect the total time and cost of the process? Does increasing the number of teams affect the process and handling operations and their costs?

3. Structure of the Ground Handling Process

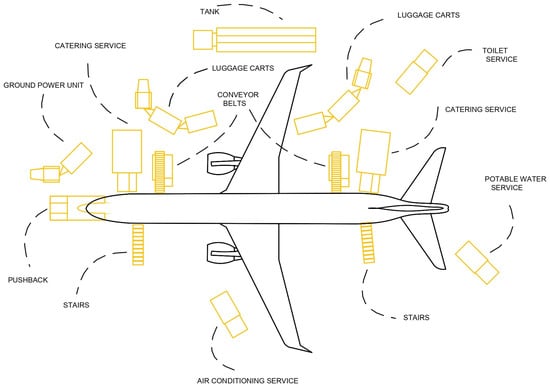

The ground handling process includes a set of activities performed after the arrival of an aircraft at an airport to ensure its readiness to perform tasks according to the planned schedule. Each type of aircraft has a defined procedure for handling. An example ramp layout is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Example of the arrangement of devices in the process of ground handling of an aircraft, adapted from [39].

Ground handling activities mainly involve handling baggage, cargo, mail, and passengers. Specific activities in this area include the following:

- Wheel chocking—the process of placing chocks to prevent the movement of an aircraft while it is parked on the airport apron;

- Positioning passenger stairs/jet bridge—the process of securely connecting stairs/jet bridges to aircraft necessary for boarding/deboarding passengers and aircraft crew;

- Passenger deboarding—the process of passengers and crew leaving an aircraft;

- Cabin servicing/cleaning—the process of cleaning the aircraft, including seats and surfaces, and replenishing supplies inside the aircraft;

- Passenger boarding—the process of passengers and crew boarding an aircraft;

- Removing passenger stairs/disconnecting the jet bridge—process of safely disconnecting stairs/jet bridge;

- Unload compartment—the process of unloading passenger baggage and cargo from the hold of an aircraft;

- Load compartment—the process of loading passenger baggage and cargo into the hold of an aircraft;

- Aircraft refuelling—the process of delivering a specified amount of fuel to aircraft tanks;

- Service lavatories—the process of emptying aircraft tanks of waste;

- Potable water replenishment—the process of filling aircraft tanks with potable water;

- Removing wheel chocks—the process of removing chocks that prevent the aircraft from moving while parked on the airport apron.

All activities must be carried out in accordance with the applicable operating instructions. Aircraft handling is characterized by the fact that some activities can be performed simultaneously, e.g., passenger disembarkation and baggage unloading, while others must be performed sequentially—for example, aircraft cleaning can only take place after passengers have left the aircraft.

4. Methodology for Compressing Ground Handling Process Networks

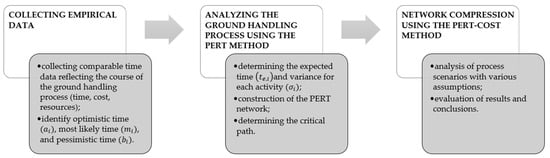

The network compression method using PERT-COST (Program Evaluation and Review Technique-Cost) model is based on three main steps: collecting empirical data, analyzing the ground handling process using the PERT method, and network compression using the PERT-COST method. Figure 2 presents the methodological procedure.

Figure 2.

Methodology for compressing ground handling process networks.

Step 1—collecting empirical data—is responsible for gathering comparable time data reflecting the course of the ground handling process. A lack of reliable empirical data leads to erroneous analyses. This stage ensures the quality and reliability of the input data necessary for the analysis of the handling process using the PERT method. The data should be collected using appropriate methods, i.e., measurement sheets and time recording tools. In the event of gaps or outliers, appropriate corrections and additions should be made. The minimum sample size is 30 observations of the service process for 30 aircrafts. It is also important that each type of aircraft has its own operational manual containing information on the equipment necessary for its implementation and its expected operational duration. The times that should be included in the measurements are presented in Section 3 of the paper. These times are the starting point for step 2—analyzing the ground handling process using the PERT method. The collected data should enable the identification of the start and end times of each ground handling process activity. The data must be complete (a list of all activities performed within the ground handling process), consistent (without missing information), and reproducible (allowing for the reconstruction of the full process sequence).

Step 2—analyzing the ground handling process using the PERT method—focuses on mapping the sequence of ground handling activities in the form of a diagram representing the relationships between individual activities. The PERT diagram consists of the following elements:

- Arrows—symbolizing the beginning, direction, and end of the activity being performed;

- Events—symbolizing a point in time during the activity being performed;

- Apparent activities—symbolizing only the relationship between events in time, for which .

This stage also requires defining the earliest possible start time , the latest possible start time , the earliest possible completion time , and the latest possible time for the activity to finish .

Each activity is described by three time assessments—optimistic , most likely , and pessimistic . The expected (nominal) duration is computed by (1), while the uncertainty of the time description, expressed as the variance, follows (2). In the deterministic baseline schedule, the nominal duration is set equal to the expected value as in (3), and a technological crash duration , shorter than the nominal, is defined in accordance with equipment and infrastructure constraints (e.g., an additional cleaning team, a second set of stairs, parallel Ground Power Unit (GPU)/Air Start Unit (ASU)), which is formalized in (4).

The result of the developed graph and defined times is the identification of the critical path of the process. There are activities whose delay will cause a delay in the implementation of the entire service process.

Step 3—network compression using the PERT-COST method—is based on the cost layer and is built on two parameters: the nominal cost , associated with standard execution, and the crash cost , which captures surcharges driven by time compression (for example, purchasing additional 0.25 h/0.5 h billing quanta for stairs or GPU, deploying a second crew, or priority call-outs). Because the relationship between cost and the assigned time is stepwise and piecewise in practice, the activity cost is written as (5), where encodes tariff thresholds and resource indivisibilities. For summary diagnostics, it is convenient to use a linear marginal indicator—the “cost slope”—as in (6); in steps where tariff thresholds must be respected exactly, this is replaced by a discrete cost increment (7).

The schedule used for optimization is obtained by critical path analysis for the current duration vector . The project completion time is defined by (8). The set of critical activities comprises those with zero total float, as in (9). In practice, shortening one branch (e.g., stairs → deboarding → cleaning → boarding) can activate constraints on baggage branches and technical/logistics branches (fuelling, lavatory, potable water, pushback), so may contain multiple paths simultaneously.

The PERT-COST procedure is iterative. In each iteration, the critical set is identified, and then an activity or subset of activities with is selected for which the marginal cost of shortening is minimal—under the linear surrogate by (6), or exactly by the discrete increment in (7). The time reduction is applied by the smallest admissible quantum consistent with tariff granularity (0.25 h/0.5 h) and resource indivisibility (a whole crew, a complete equipment set), after which the network is re-evaluated immediately. Because compressing the dominant passenger branch often activates baggage, technical, and logistics constraints, multiple critical paths typically emerge; to achieve a further reduction in project time, at least one activity on each critical path must be shortened, otherwise remains unchanged.

The process terminates in the full-crash regime when every activity on each current critical path has reached its crash limit , expressed by condition (10). Alternatively, a deadline constraint (11) or a budget constraint (12) can be imposed. In all variants, a full audit trail is maintained: which durations were shortened, by how much, and what cost increment was incurred—consistently with the cost function (5) and the airport’s tariff rules.

Under this specification, the method links computational simplicity with operational fidelity: stepwise tariff thresholds, resource indivisibilities, and parallelization directly shape the cost function (5) and the slope values (6), and thereby the order and magnitude of time reductions applied in successive iterations. As a result, PERT-COST yields a transparent, auditable relationship between time compression and the total cost of the post-landing turnaround.

5. Results and Discussion

5.1. Results of Collecting Empirical Data

The data for analysis were collected based on observations and measurements of ground handling times. The sample selection—30 Embraer E190 aircraft—was random. Measurements and observations were carried out on different days and at different times. Additionally, data were collected for different aircraft rotations. This approach allowed for the diversification of airport operating conditions to be considered in the time database. The data collection process was based on a specially prepared measurement form, thus ensuring the completeness and repeatability of the results. The collected empirical data allowed us to identify optimistic time (), most likely time (), and pessimistic time (). The optimistic scenario was determined based on the minimum completion time of the observed activities. The most likely scenario was defined as the average duration of the activity. The pessimistic scenario was determined based on the maximum identified completion time. A summary of the collected times is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Empirical data on the duration of ground handling operations for the Embraer E190.

The empirical data obtained reflect the heterogeneity of the duration of individual ground handling activities. In the optimistic and most likely scenario, the longest activity is related to refuelling the aircraft. In the pessimistic scenario, however, it is toilet service. The time required for activities related to baggage handling (load compartment, unload compartment) and passengers (passenger deboarding, passenger boarding) depends on the number of bags and passengers, respectively. The times required for other activities also vary, reflecting the impact of operational and human factors.

5.2. Results of Ground Handling Process Analysis Using the PERT Method

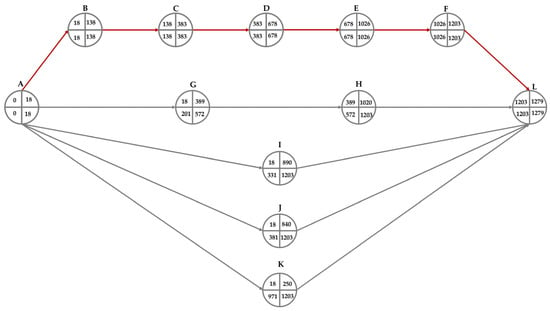

The collected empirical data formed the basis for the PERT diagram. Figure 3 shows the PERT network diagram, with the critical path marked in red. Table 2 presents data on events (the earliest possible start time of an activity , the latest possible start time of an activity , the earliest possible completion time of an activity and latest possible start time of the activity ) and the determined values of expected (nominal) duration (), standard deviation (), lower confidence limit (, and upper confidence limit (.

Figure 3.

Diagram of the ground handling process for the Embraer E190 aircraft.

Table 2.

Empirical data for the Embraer E190 PERT diagram.

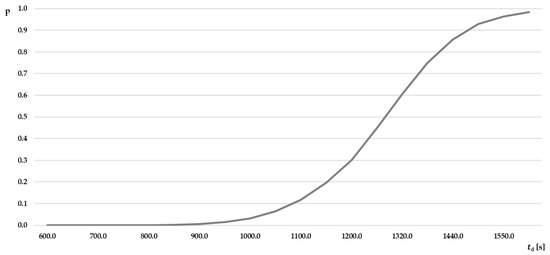

The network diagram presented in Figure 4 shows the logical and temporal relationships between the activities carried out as part of the ground handling process. The network diagram also shows the critical path of the aircraft handling process—A, B, C, D, E, F, L. According to the diagram and the data presented in Table 2, the aircraft ground handling process can take 21.3 [min]. Figure 4 shows the probability of completing the service process within a given time and .

Figure 4.

Probability of completing the service process on time .

5.3. Results of Network Compression Using the PERT-COST Method

This section presents a comparative set of PERT-COST variants and a reporting protocol that ensures full comparability across configurations. Each variant preserves the same activity network and precedence relations, as well as the same rules for determining and from the methodological section; the project completion time defined previously serves as the outcome of time compression, and activity costs are described by (see (5)–(9)).

The following variants were analyzed:

- A linear model versus a threshold (piecewise) model, both targeting the same time objective (see (11)) and differing only in the cost representation—under the linear model we apply a piecewise-linear approximation , whereas under the threshold model we allow reductions only in the smallest billing quanta consistent with tariffs (see (16));

- Remote stand versus contact gate with jet bridge, where the impact of stand configuration on the times and costs of stair/bridge activities (B, F) is captured via multipliers that shorten time and cost relative to the remote stand baseline (see (17));

- Low versus high refuelling volume, where the nominal into-plane component is computed from the fuel uplift (see (18)), allowing an assessment of when branch I becomes co-critical;

- Day versus night (with surcharges), where a multiplier is applied to the crash portion of the cost to reflect night/peak tariffs (see (19));

- Without versus with a second baggage team, where parallelization of G/H is permitted by shortening crash limits and adding a duplication cost to the crash cost (see (20)).

For comparability, each run reports the final project time (see (8)), the total crash cost , the set of critical paths at termination, and the profile of “euro per minute saved” as crashing progresses. To that end, the following iteration-level indicators are defined: the total cost increment in (13), the reduction in the project time in (14), and the marginal cost of time reduction in [EUR/min] (15). The plot makes tariff thresholds and diminishing marginal returns explicit.

Variant parameterization was as follows:

- Linear vs. threshold. In the linear case, a piecewise-linear approximation between and is applied as in (16). In the threshold case, the cost function with explicit tariff steps (see (5)) is used directly, and reductions are permitted only in the smallest billable quanta.

- Remote stand vs. gate with jet bridge. For activities B and F in the “gate” configuration, times and nominal costs are scaled by and , respectively, with all other parameters unchanged, as formalized in (17) (see also the full-crash stopping condition (10)).

- Low vs. high refuelling volume. The nominal into-plane cost is computed by (18), with times unchanged; the comparison identifies thresholds at which branch I becomes co-critical and the profile shifts.

- Day vs. night (surcharges). The crash cost in night conditions is obtained by applying a multiplier to the threshold component , while remains unchanged (see (5)).

- Without vs. with a second baggage team. For G and H, crash limits are shortened via and a team-duplication charge is added to in accordance with (20), enabling the assessment of how parallelization unlocks node L.

Across all variants, computations are stopped at two points: first, upon reaching the time target for (see (11)), which supports “to-target” comparisons; and second, in the full-crash regime when on all current critical paths and further reduction in is impossible (see (10)). This comparative framework allows an objective assessment of how cost modelling and resource/infrastructure configuration affect , , the set of critical paths, and the evolution of .

The analysis was conducted for the ground handling activity network of the Embraer E190LR using the PERT-COST framework with duration bounds , 900 s billing thresholds for the stairs/jet-bridge tasks (B and F), and a night-time cost multiplier . For the remote stand configuration (threshold cost model) the baseline time was ; for the gate with the passenger boarding bridge—with shortened B/F operations—. Two reduction targets were defined, and , i.e., and , and full crashing down to was considered, yielding the minimal attainable time . The total cost was interpreted as the cumulative surcharge required to achieve a given , and the efficiency index as the cost per minute of turnaround time saved. Detailed numerical results are reported in Table 3.

Table 3.

Results of PERT-COST analysis.

For the target, the results are unequivocal: the target is feasible in all variants, and the achieved “final time” coincides with . In the Threshold/Remote/Day setting, we obtained and at a cost of EUR 85.79 with . In the Threshold/Gate/Day setting, the lower implies and , but the cost is slightly higher—EUR 87.53 with . This difference follows from cost discontinuities on B/F: with a smaller , the reduction is sooner displaced onto branches with a higher marginal price. Night-time surcharges increase the cost of reaching the same : Threshold/Remote/Night yields , , a cost of EUR 111.53, and , reflecting the network-wide amplification of the crashing premium. Changing the refuelling uplift from 1000 to 4000 kg does not affect the outcome (in both cases , cost is EUR 85.79, ), because activity I is not the binding constraint in this reduction range. Adding a second baggage team is neutral at (the same and virtually unchanged cost), indicating that other segments of the critical path dominate at this target.

Under full crashing, Threshold/Remote/Day attains at a cost of EUR 466.98 with . The Threshold/Gate/Day variant descends further to but at a higher closing cost—EUR 477.79 with —which indicates that the gate configuration lowers both and , yet each additional minute saved near the minimum is more expensive than at the remote stand. Night operations materially escalate the cost of the minimum: Threshold/Remote/Night yields , cost EUR 607.07, and . A second baggage team produces a small cost increase at unchanged (Threshold/Remote/Day + 2nd baggage: , EUR 473.08, ), confirming the marginal impact of additional G/H parallelism in this precedence structure. Varying the fuel uplift remains immaterial at the minimum as well (for 1000 and 4000 kg: , EUR 466.98, ), because the refuelling branch does not govern the critical path.

For the target, infeasibility was demonstrated across all variants; the corresponding values—about (remote) and (gate)—lie below of and , respectively. Formally, this means that there exists no vector of durations satisfying and the B/F threshold rules such that ; the critical path is fully bound by the lower limits , and any further reduction would require technological changes to the process (e.g., additional gate/Fixed Electrical Ground Power (FEGP)/Pre-Conditioned Air (PCA) infrastructure, a different boarding/deboarding organization, or electrification of GSE to the extent that operating times are structurally reduced) rather than higher spending within the current crashing logic.

From a structural viewpoint, the infeasibility of the −50% time compression target in all variants is not a numerical artefact of the PERT-COST model but reflects the intrinsic rigidity of the present turnaround network. Along the critical path, most activities are already executed with very limited slack and are constrained by physical, safety-related, and regulatory minima: passenger deboarding and boarding are bounded by aircraft door and cabin geometry and by acceptable passenger flow rates; the positioning and removal of the stairs or passenger boarding bridge and buses must comply with obstacle-clearance and marshalling procedures; and several GSE operations compete for the same apron space and personnel, which limits further overlap. Under these conditions, the additional shortening and parallelisation required to halve the project completion time would systematically violate precedence constraints, simultaneous-occupation limits, or minimum handling times. The −50% target therefore represents a level of compression that cannot be accommodated within the current process logic, resource set, and safety rules, even when all crash options available in the model are activated.

The resource allocation problem and the associated operation time were also analyzed by Yao et al. [40]. The first objective of the model was to minimize the fuel consumption of air taxis. The second objective was to minimize the travel time of ferry vehicles. The two-stage optimization model for airport parking allocation used by Yao et al. [40] allows for a 20.4% reduction in travel distance. The approach presented by Gök et al. [41] focuses on an optimization and simulation approach to the gas utilization of maintenance teams in the scope of aircraft maintenance planning during turnaround.

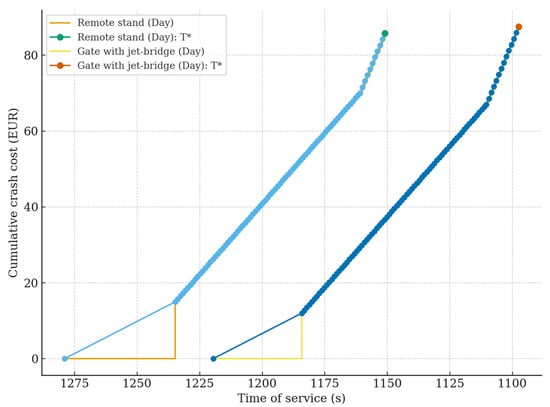

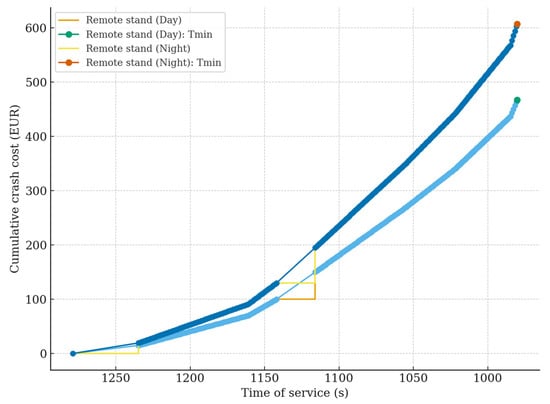

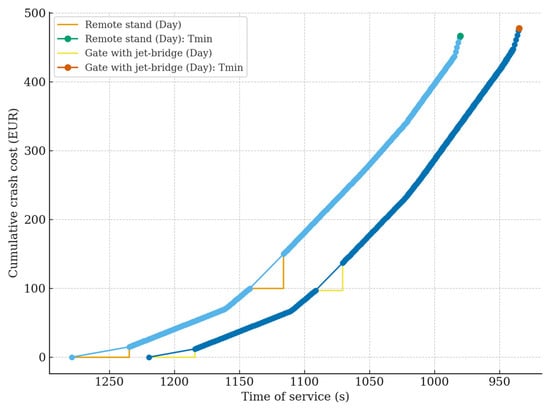

To elucidate the results, Figure 5, Figure 6 and Figure 7 present relationships selected to isolate three mechanisms that govern the marginal effectiveness of crashing in the PERT-COST network: the effect of stand infrastructure (remote versus gate) under a moderate target, the effect of night-time markups under an unchanged time minimum, and the trade-off between the lowest achievable time and the marginal price in full crashing.

Figure 5.

Cost–time trade-off for the −10% target (threshold model).

Figure 6.

Cost–time trade-off under full crash (remote stand).

Figure 7.

Cost–time trade-off under full crash (daytime), remote stand versus gate with jet bridge.

Figure 5 compares the remote and gate variants for the −10% target and exposes the role of the 900 s billing thresholds for the stairs/jet-bridge tasks (B/F) when the critical path still has positive crashing slack: the left-hand curve corresponds to the remote configuration and reaches at a lower cumulative cost (≈EUR 85.8) with a gentler terminal slope, whereas the right-hand curve corresponds to the gate configuration, which attains a lower target time and a slightly higher cost (≈EUR 87.5) with a steeper segment immediately before . The slope difference follows from the earlier activation of the 900 s thresholds on B/F in the gate setup, and a faster displacement of crashing onto branches with higher marginal cost.

Figure 6 isolates the night-policy effect: both curves start from the same baseline and terminate at the same minimum , yet the right-hand curve (night; ) runs strictly above the left-hand curve (day) across the entire range and closes at a markedly higher cost (≈EUR 607 versus ≈EUR 467). This confirms that internalizing the environmental and social externalities of night operations alters the cost profile without changing the attainable time minimum.

Figure 7 compares the feasibility frontiers in full crashing for the same daytime conditions: the left-hand curve represents remote and ends at with a lower cost (≈EUR 467), whereas the right-hand curve represents the gate and descends further to but at a higher closing cost (≈EUR 478), i.e., it achieves a shorter minimum time at the expense of a higher marginal price for the “last minutes”.

Methodologically, this set of views is coherent: Figure 5 shows how the 900 s thresholds modulate the cost of reaching a moderate target at different . Figure 6 separates the impact of the night multiplier on cost while holding fixed. Figure 7 delineates the time frontier of the infrastructure (remote versus gate) at the minimum, quantifying the trade-off between a lower and a higher closing cost. Taken together, the figures form an integral part of the argument, progressing from differences in pre- cost behaviour, through the pure effect, to a comparison of the network’s physical bounds that determine both the feasibility and economic rationality of time reduction.

Formally, the project time satisfies under the feasible set . The structural minimum is . In the present network, 980 s (remote) and 934 s (gate), whereas the −50% targets are 640 s and 610 s, respectively; since , the target is infeasible: there is no with .

The gap is explained by three root causes:

- The largely serial passenger chain B–C–D–E–F–L, whose activities possess tight lower bounds and admit only limited overlap;

- Quantized thresholds (900 s) for stairs/jet-bridge tasks B/F, which induce discontinuous costs and accelerate the shift in crashing onto higher-marginal-cost branches;

- Insufficient structural parallelism in the critical segments, so that full crashing binds multiple simultaneously.

Viewed in synthesis, the numerical results in Table 3 show that the −10% target can be attained in all variants at moderate crash costs and comparatively low values of the efficiency index η, whereas the −50% target is infeasible and full-crash solutions are associated with sharply increasing η. For daytime operations at a remote stand, the linear and threshold formulations produce identical time and cost outcomes at both the −10% and full-crash settings (project completion time reduced from 1279 s to 1151 s and 980 s, respectively, with ΣΔC = EUR 85.79 and EUR 466.98, and η = 40.21 EUR/min and 93.71 EUR/min). Switching to a contact gate with jet bridge improves the final time both at −10% (1097 s, ΣΔC = EUR 87.53, η = 43.05 EUR/min) and under full crash (934 s, ΣΔC = EUR 477.79, η = 100.59 EUR/min), but at a consistently higher marginal price per minute saved. Introducing night-time surcharges while keeping the remote stand configuration leaves the attainable times unchanged (1151 s and 980 s) but increases ΣΔC to EUR 111.53 and EUR 607.07 and η to 52.28 EUR/min and 121.82 EUR/min, indicating that aggressive compression in night conditions is economically inefficient. Additional baggage resources and changes in refuelling uplift do not modify the final project time or η at the investigated compression levels, which suggests that, in the present network structure, the dominant levers for economically sustainable time reduction lie in the choice of stand and the timing of operations rather than in baggage handling or fuel volume decisions.

6. Conclusions

The interpretation of the PERT-COST results is consistent with sustainable development objectives. The gate configuration (contact stand with a passenger boarding bridge), despite a higher marginal cost at large time reductions, facilitates a reduction in Auxiliary Power Unit (APU) usage and airside vehicle movements by enabling the systematic deployment of FEGP /PCA and by lowering the need for apron buses; consequently, it mitigates environmental externalities. Night operations—represented in the model by a multiplier λ = 1.3 applied to the crashing premium—internalize the social costs of noise and emissions, which manifests as a pronounced increase in the cumulative cost ∑ΔC and in the efficiency index η (EUR per minute of reduction) for the same target time T^“\*” and minimal attainable time T_min. The empirical evidence indicates that the most productive intervention range—economically and environmentally—lies at around a 10% reduction, where the critical path still exhibits positive crashing slack and the quantized thresholds (e.g., 900 s for the stairs/jet-bridge tasks) do not trigger a sharp escalation in the marginal price of the last minute saved. To ensure full alignment with sustainability policy, operational decisions should be made within a multi-criteria framework in which, alongside ∑ΔC and η, one also reports an “environmental cost equivalent per minute of reduction” derived from the reduction in APU operating time, GSE movements, and noise exposure; in practice, this implies prioritizing gate assignments, limiting night-time crashing, electrifying the GSE fleet, and engaging a second baggage team selectively—only in scenarios where the G/H branch (Unload compartment and Load compartment) effectively governs the critical path.

The analysis also indicates that achieving a turnaround time reduction in the order of 50% would require innovations that go beyond classical time–cost crashing of the existing network. Such a target would call for structural changes to the service concept (for instance, multi-door boarding and deboarding or the use of dual passenger boarding bridges), higher levels of automation and autonomy in GSE fleets and baggage handling systems, and tighter digital integration of the stakeholders through advanced turnaround management platforms and predictive decision support tools. In parallel, redesigned apron layouts and procedures would be needed to enable the safe parallel execution of tasks that are currently mostly sequential. These developments lie outside the scope of the present model, but they point to a natural direction for future research and for airport–airline investment decisions.

The use of the PERT method is associated with a certain level of uncertainty. This uncertainty will be identifiable due to the specific nature of the process. The ground handling process is complex and dynamic, involving ground handling operators with varying levels of training and psychosomatic conditions. Standardizing work organization could be helpful. Automating activities has the potential to minimize uncertainty within the process, allowing for an increased repeatability of tasks.

Scope is limited to a single aircraft type (Embraer E190LR), one activity network and precedence set, and European-style tariffs with stylized 900 s thresholds for selected resources. Cost parameters reflect representative airport tariffs rather than carrier- or station-specific contracts. Environmental externalities are simplified to a night multiplier . Results are reported deterministically; uncertainty in activity times is not propagated to cost outcomes. Stand assignment, gate availability, and safety constraints are treated exogenously. Structural process changes are not endogenized.

Future work should extend the protocol to multiple aircraft types and airports with port-specific tariffs and time-of-day pricing; propagate uncertainty with stochastic/robust targets for and cost; couple crashing with stand, crew, and schedule assignment; monetize environmental externalities in a multi-objective framework alongside ; and test structural innovations (dual-door operations, parallel G/H streams, hydrant fueling with compliant overlap, and gate automation) that reduce and increase admissible concurrency.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.K. and T.K.; methodology, A.K., T.K., J.R., E.M.; software, validation, A.K., T.K., J.R., E.M., O.P.; formal analysis, T.K.; investigation, A.K., T.K., J.R., E.M.; resources, E.M.; data curation, A.K., O.P.; writing—original draft preparation, J.R., E.M.; writing—review and editing, A.K., T.K., J.R.; visualization, E.M.; supervision, A.K., T.K., O.P.; project administration, J.R., O.P.; funding acquisition, A.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- IATA. Air Passenger Market Analysis. July 2025. Available online: https://www.iata.org/en/publications/economics/reports/air-passenger-market-analysis-july-2025/ (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Joint ACI World-ICAO Passenger Traffic Report, Trends, and Outlook | ACI World. Available online: https://aci.aero/2025/01/28/joint-aci-world-icao-passenger-traffic-report-trends-and-outlook/ (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Airport Ground Handling Market Size, Share, Trends Report 2033. Available online: https://www.alliedmarketresearch.com/airport-ground-handling-market (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- 16 Cost of Delay—EUROCONTROL Standard Inputs for Economic Analyses. Available online: https://ansperformance.eu/economics/cba/standard-inputs/latest/chapters/cost_of_delay.html (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Alba, S.O.; Manana, M. Energy Research in Airports: A Review. Energies 2016, 9, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Tang, T.-Q.; Cao, F.; Zhang, J.; Wang, R. A two-phase total optimization on aircraft stand assignment and tow-tractor routing considering energy-saving and attributes. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2023, 57, 103237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heß, L.; Dimova, D.; Piechalski, J.W.; Rusche, S.; Best, P.; Sonnekalb, M. Analysis of the Specific Energy Consumption of Battery-Driven Electrical Buses for Heating and Cooling in Dependence on the Technical Equipment and Operating Conditions. World Electr. Veh. J. 2023, 14, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, D.-W.; Zhou, J.-Y.; Zhang, Z.-Q.; Chen, Z.; Kang, D. Mixed fleet scheduling method for airport ground service vehicles under the trend of electrification. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2023, 108, 102379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battipede, M.; Della Corte, A.; Vazzola, M.; Tancredi, D. Innovative airplane ground handling system for green operations. In Proceedings of the 27th Congress of the International Council of the Aeronautical Sciences (ICAS), Nice, France, 19–24 September 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Timmermans, K.; Roling, P.; Mouli, G.R.C.; Atasoy, B. The impact of transitioning to electric Ground Support Equipment on the fleet capacity and energy demand at airports. Case Stud. Transp. Policy 2025, 21, 101498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baxter, G.; Srisaeng, P.; Wild, G. A Qualitative Assessment of a Full-Service Network Airline Sustainable Energy Management: The Case of Finnair PLC. WSEAS Trans. Environ. Dev. 2021, 17, 167–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winther, M.; Kousgaard, U.; Ellermann, T.; Massling, A.; Nøjgaard, J.K.; Ketzel, M. Emissions of NO x, particle mass and particle numbers from aircraft main engines, APU’s and handling equipment at Copenhagen Airport. Atmos. Environ. 2015, 100, 218–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volt, J.; Stojić, S.; Had, P. Optimization of the Baggage Loading and Unloading Equipment. Transp. Res. Procedia 2022, 65, 246–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanenko, V.A.; Skorokhod, M.A.; Guzha, E.D. Fuzzy control in the simulation model of airport baggage handling systems. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 919, 042017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padrón, S.; Guimarans, D. An Improved Method for Scheduling Aircraft Ground Handling Operations From a Global Perspective. Asia-Pac. J. Oper. Res. 2019, 36, 1950020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.-T.; Ermiş, G.; Sharpanskykh, A. Multi-agent planning and coordination for automated aircraft ground handling. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2023, 167, 104480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padrón, S.; Guimarans, D.; Ramos, J.J.; Fitouri-Trabelsi, S. A bi-objective approach for scheduling ground-handling vehicles in airports. Comput. Oper. Res. 2016, 71, 34–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Wu, Y.; Cao, Z.; Song, W.; Zhang, J.; Chen, Z. Learning Large Neighborhood Search for Vehicle Routing in Airport Ground Handling. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2023, 35, 9769–9782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Zhou, J.; Xia, Y.; Zhang, X.; Cao, Z.; Zhang, J. Neural Airport Ground Handling. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2023, 24, 15652–15666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreatta, G.; De Giovanni, L.; Monaci, M. A Fast Heuristic for Airport Ground-Service Equipment–and–Staff Allocation. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 108, 26–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamdouh, M.; Ezzat, M.; Hefny, H.A. Airport resource allocation using machine learning techniques. Intell. Artif. 2020, 23, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Sun, H.; Guo, X. Cooperative scheduling optimization for ground-handling vehicles by considering flights’ uncertainty. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2022, 169, 108092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kierzkowski, A.; Kisiel, T. Simulation model of logistic support for functioning of ground handling agent, taking into account a random time of aircrafts arrival. In Proceedings of the 2015 International Conference on Military Technologies (ICMT), Brno, Czech Republic, 19–21 May 2015; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahun, Y.; Zalevskii, A.; Chornohor, N.; Sikirda, Y. Development and visualization of the computer loadıng plannıng model for the cargo aırcraft. East.-Eur. J. Enterp. Technol. 2021, 3, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kierzkowski, A.; Kisiel, T. A Simulation Model of Aircraft Ground Handling: Case Study of the Wroclaw Airport Terminal. In Information Systems Architecture and Technology: Proceedings of the 37th International Conference on Information Systems Architecture and Technology—ISAT 2016—Part III; Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; Volume 523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kierzkowski, A.; Kisiel, T. Narzędzie symulacyjne analizy zdolności operacyjnej portu lotniczego po wystą-pieniu opóźnienia pierwotnego. Logistyka 2014, 6, 5411–5417. [Google Scholar]

- Li, B.; Wang, L.; Xing, Z.; Luo, Q. Performance Evaluation of Multiflight Ground Handling Process. Aerospace 2022, 9, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydın, S.; Yörükoğlu, M. Turkish ground handling services firms assesment with neutrosophic multiobjective method. J. Intell. Fuzzy Syst. 2019, 38, 545–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidberger, S.; Bals, L.; Hartmann, E.; Jahns, C. Ground handling services at European hub airports: Development of a performance measurement system for benchmarking. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2009, 117, 104–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazgan, E.; Durmaz, V.; Yilmaz, A.K. Development of risk factors taxonomy in ramp operations for corporate sustainability. Aircr. Eng. Aerosp. Technol. 2021, 94, 268–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chikha, P.; Skorupski, J. The risk of an airport traffic accident in the context of the ground handling personnel performance. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2022, 105, 102295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, Y.S.R.; Rashid, H. Enhancing human performance reliability in aircraft pushback operations. Int. J. Qual. Reliab. Manag. 2019, 36, 485–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morais, C.; Ribeiro, J.; Silva, J. Human factors in aviation: Fatigue management in ramp workers. Open Eng. 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kholil, M.; Alfa, B.N. Supriyanto Optimization of Production Process Time with Network/PERT Analysis Technique and SMED Method. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2018, 453, 012050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iheonu, N.O.; Achom, U.K. Project Planning Application to Juice Production Using PERT/CPM Technique: A Case Study. Asian J. Probab. Stat. 2023, 24, 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masłowski, D.; Kijewska, K.; Kulińska, E. Management of Municipal Public Transport Vehicle Journeys by Using the PERT Method. Energies 2021, 14, 4403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makhloof, M.A.A.; Waheed, M.E.; Badawi, U.A.E.-R. Real-time aircraft turnaround operations manager. Prod. Plan. Control. 2012, 25, 2–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonio, A.S.; Juan, A.A.; Calvet, L.; i Casas, P.F.; Guimarans, D. Using simulation to estimate critical paths and survival functions in aircraft turnaround processes. In Proceedings of the 2017 Winter Simulation Conference (WSC), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 3–6 December 2017; pp. 3394–3403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Airbus S.A.S. Aircraft Characteristics Airport and Maintenance Planning; Airbus A320; Airbus S.A.S.: Blagnac Cedex, France, 2024. Available online: https://aircraft.airbus.com/sites/g/files/jlcbta126/files/2025-01/AC_A320_0624.pdf (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Yao, M.; Hu, M.; Yin, J.; Su, J.; Yin, M. A Two-Stage Optimization Model for Airport Stand Allocation and Ground Support Vehicle Scheduling. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 11407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gök, Y.S.; Padrón, S.; Tomasella, M.; Guimarans, D.; Ozturk, C. Constraint-based robust planning and scheduling of airport apron operations through simheuristics. Ann. Oper. Res. 2022, 320, 795–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).