Modulating Secondary Metabolite Content in Olive Leaves Through Foliar Application of Biochar and Olive Leaf-Based Phenolic Extracts

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material and Experimental Setup

2.2. LC-MS-MS

2.3. ICP-OES

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

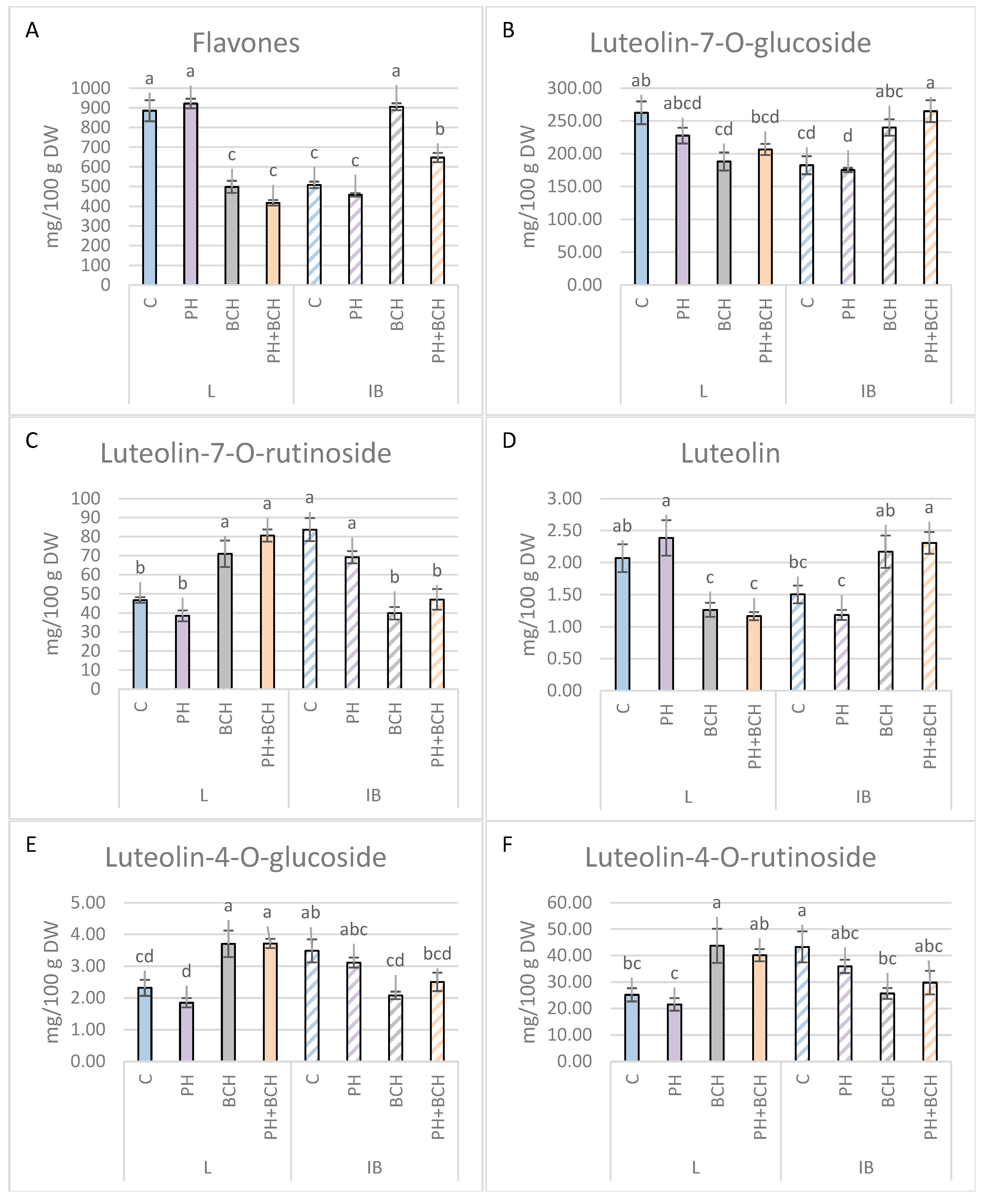

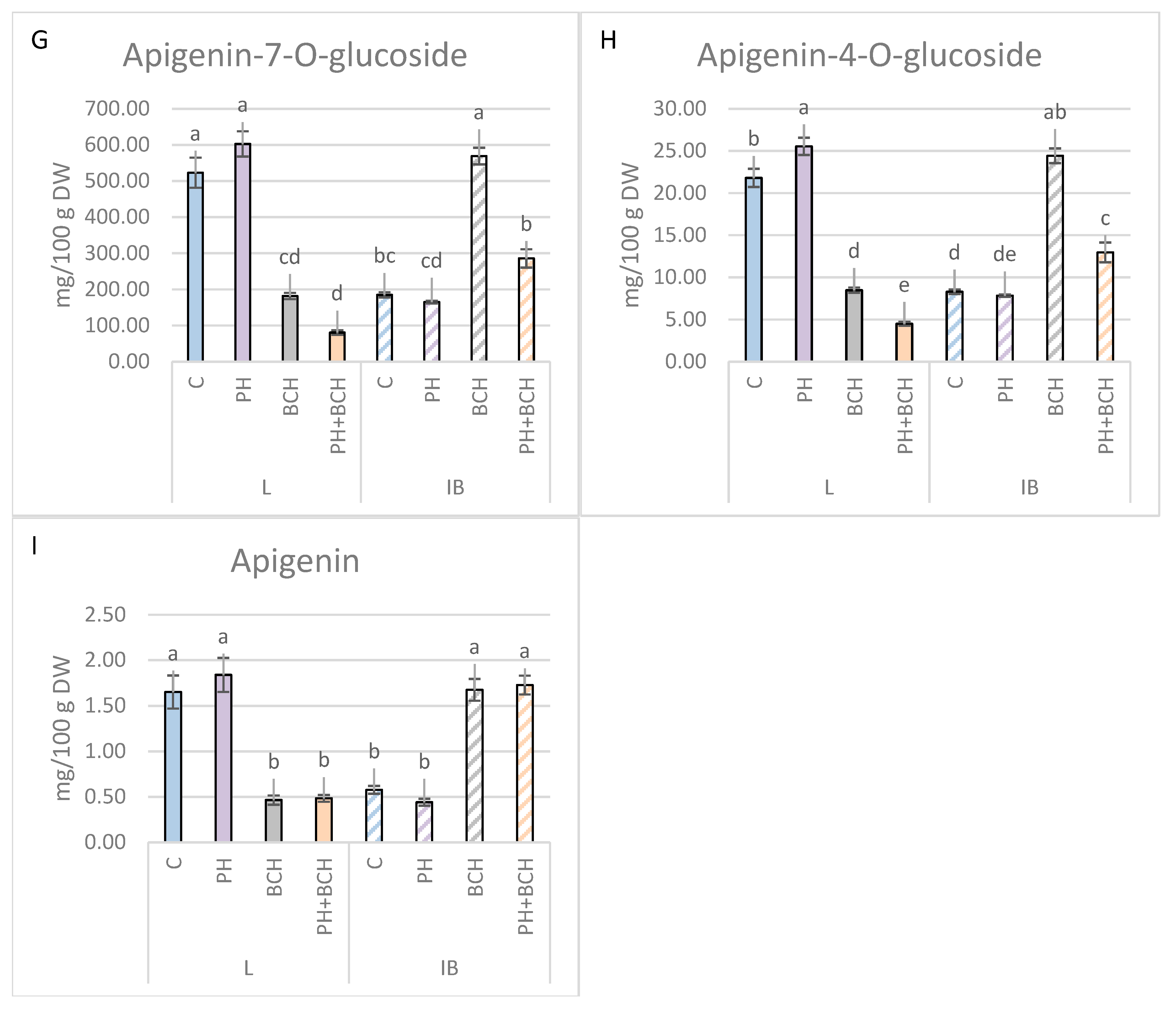

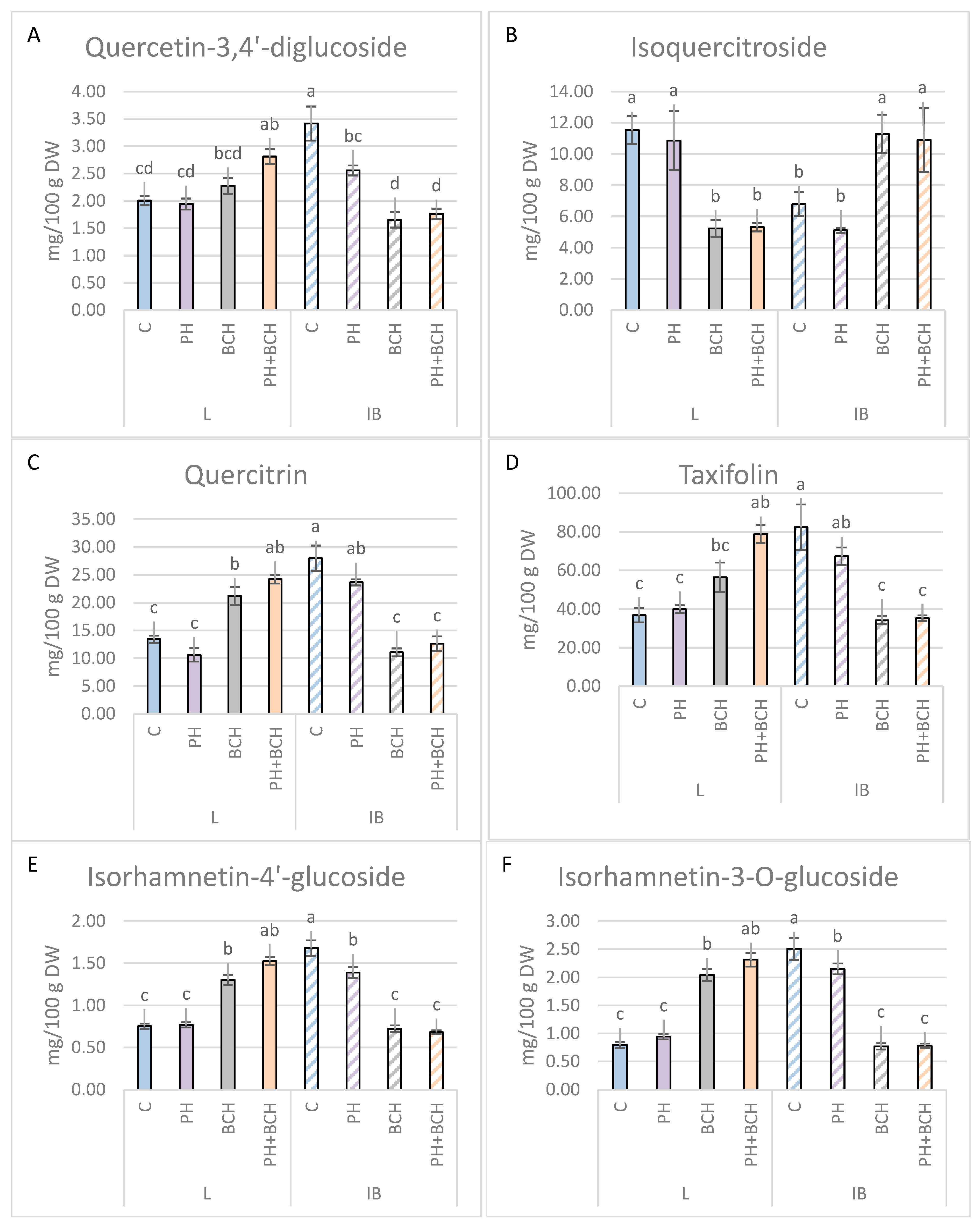

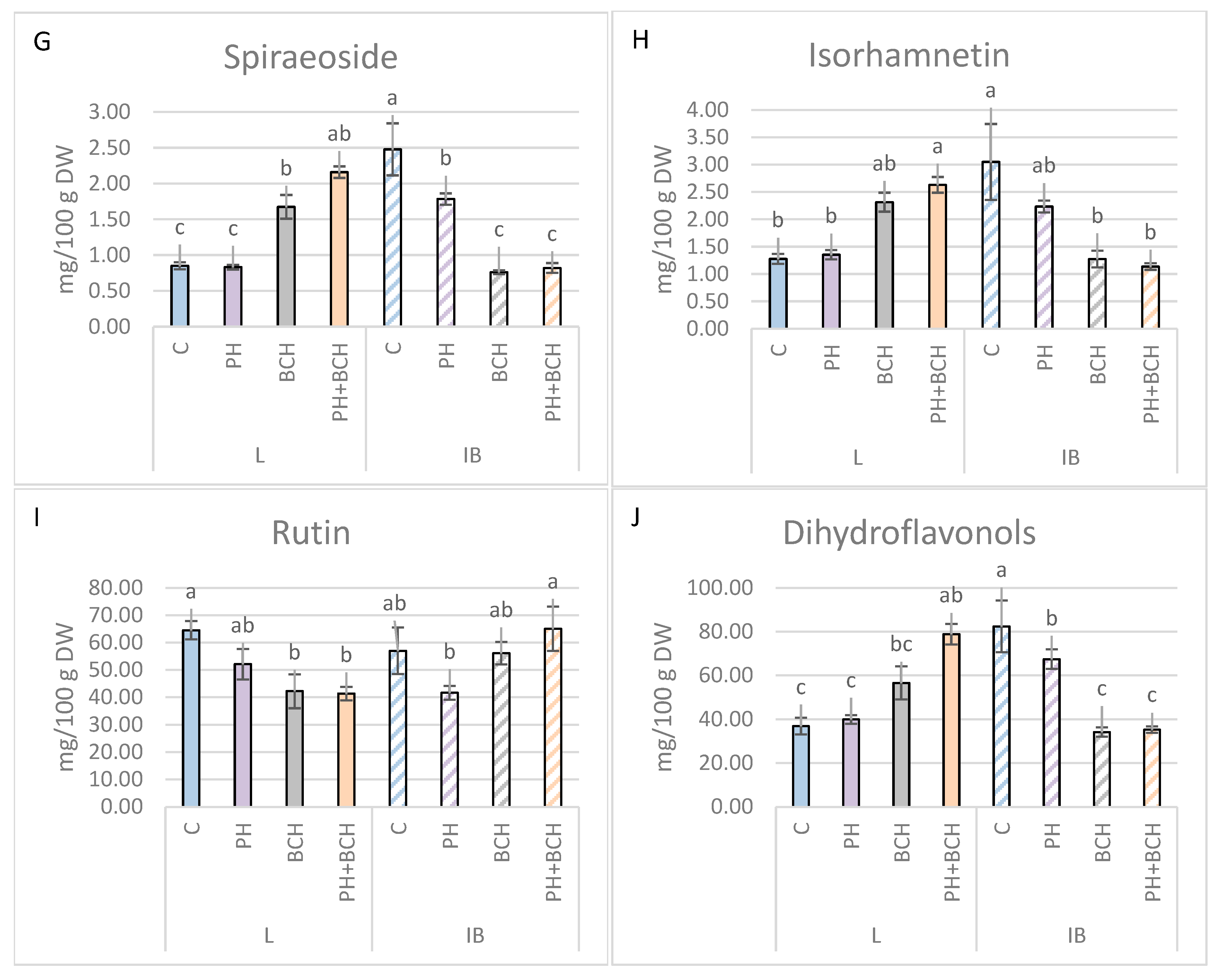

3.1. Effects of Biochar and/or Phenolic Extracts on Phenolic Contents in Olive Leaves

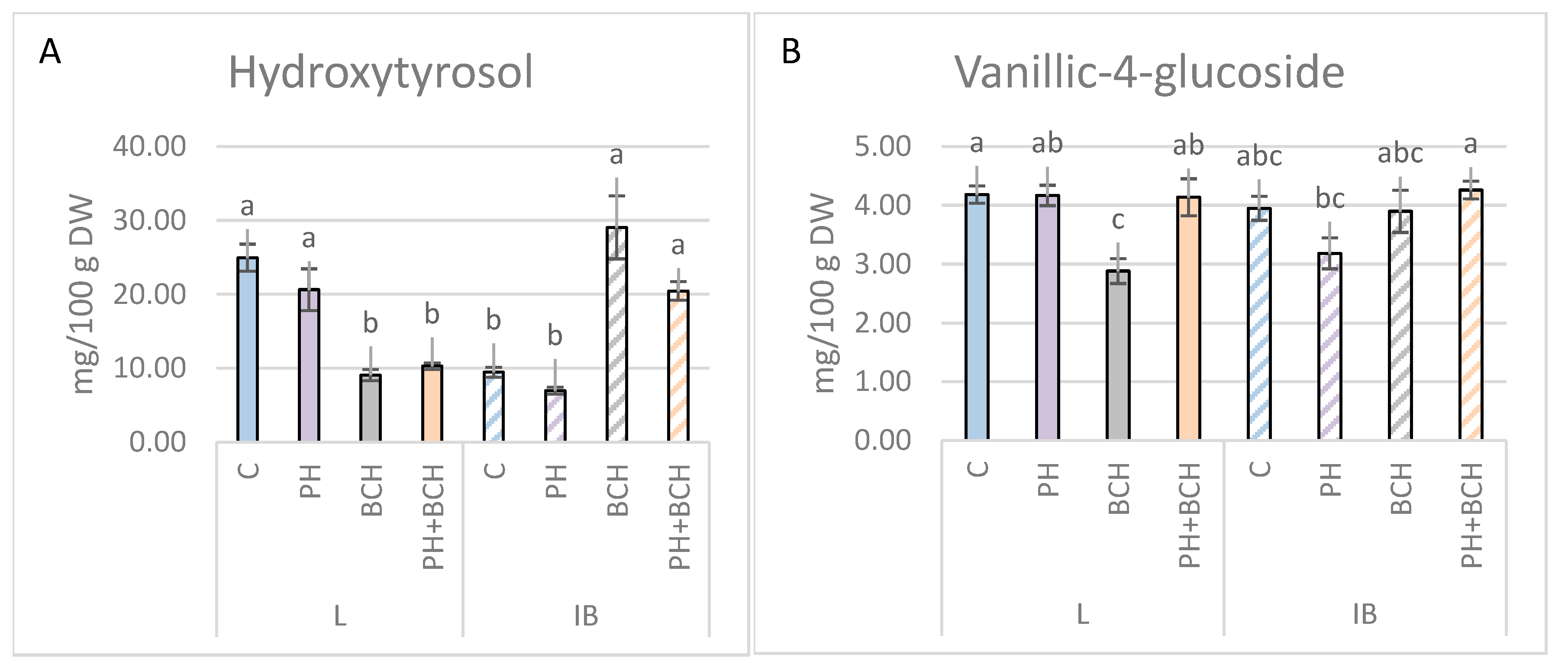

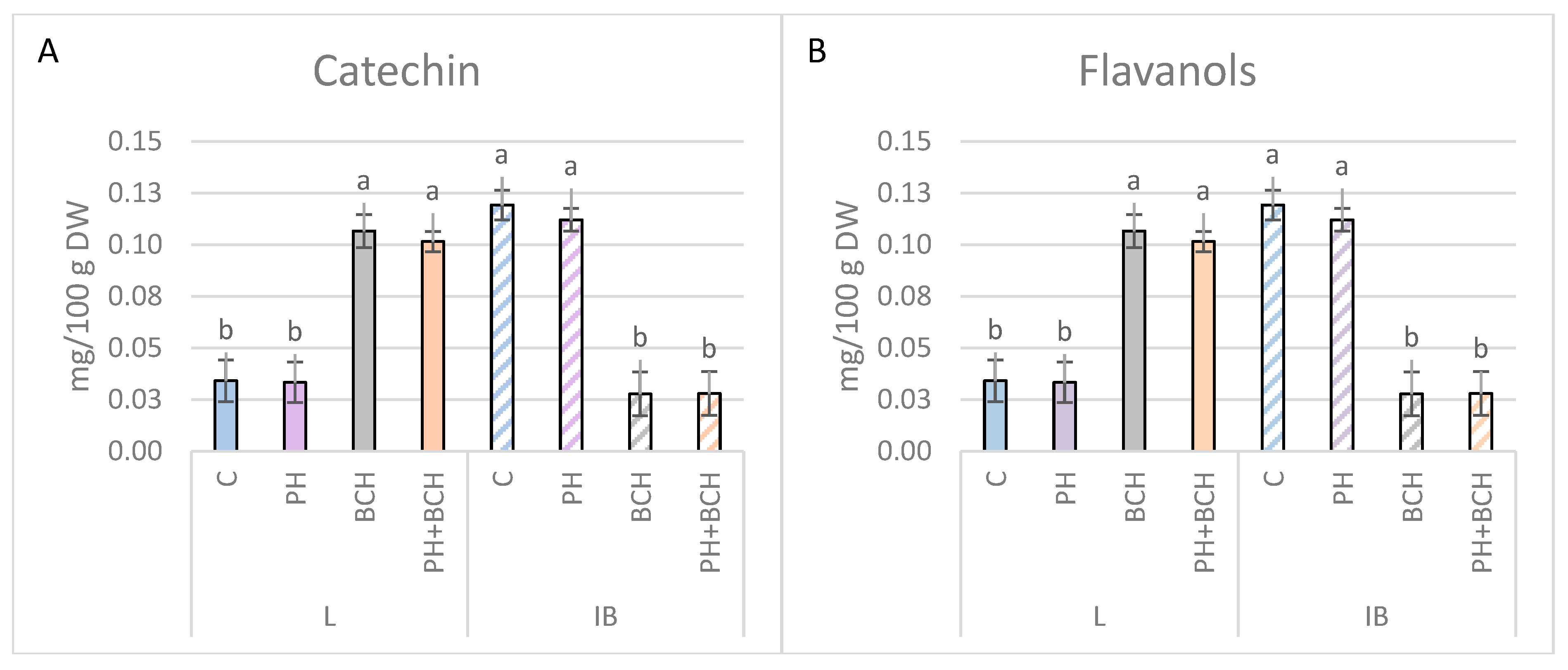

3.1.1. Pattern I

3.1.2. Pattern II

3.1.3. No Evident Pattern

3.2. Effects of Biochar and/or Phenolic Extracts on Elemental Content in Olive Leaves

3.3. Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Difonzo, G.; Crescenzi, M.A.; Piacente, S.; Altamura, G.; Caponio, F.; Montoro, P. Metabolomics Approach to Characterize Green Olive Leaf Extracts Classified Based on Variety and Season. Plants 2022, 11, 3321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guinda, Á.; Albi, T.; Pérez-Camino, M.C.; Lanzón, A. Supplementation of Oils with Oleanolic Acid from the Olive Leaf (Olea europaea). Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 2004, 106, 22–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, A.L.S.; Gondim, S.; Gómez-García, R.; Ribeiro, T.; Pintado, M. Olive Leaf Phenolic Extract from Two Portuguese Cultivars–Bioactivities for Potential Food and Cosmetic Application. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 106175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selim, S.; Albqmi, M.; Al-Sanea, M.M.; Alnusaire, T.S.; Almuhayawi, M.S.; AbdElgawad, H.; Al Jaouni, S.K.; Elkelish, A.; Hussein, S.; Warrad, M.; et al. Valorizing the Usage of Olive Leaves, Bioactive Compounds, Biological Activities, and Food Applications: A Comprehensive Review. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 1008349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debs, E.; Abi-Khattar, A.-M.; Rajha, H.N.; Abdel-Massih, R.M.; Assaf, J.-C.; Koubaa, M.; Maroun, R.G.; Louka, N. Valorization of Olive Leaves through Polyphenol Recovery Using Innovative Pretreatments and Extraction Techniques: An Updated Review. Separations 2023, 10, 587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Márquez, J.M.; Navarro-Hortal, M.D.; Forbes-Hernández, T.Y.; Varela-López, A.; Puentes, J.G.; Pino-García, R.D.; Sánchez-González, C.; Elio, I.; Battino, M.; García, R.; et al. Exploring the Antioxidant, Neuroprotective, and Anti-Inflammatory Potential of Olive Leaf Extracts from Spain, Portugal, Greece, and Italy. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Innosa, D.; Bennato, F.; Ianni, A.; Martino, C.; Grotta, L.; Pomilio, F.; Martino, G. Influence of Olive Leaves Feeding on Chemical-Nutritional Quality of Goat Ricotta Cheese. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2020, 246, 923–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukić, I.; Pasković, I.; Žurga, P.; Germek, V.M.; Brkljača, M.; Marcelić, Š.; Ban, D.; Grozić, K.; Lukić, M.; Užila, Z.; et al. Determination of the Variability of Biophenols and Mineral Nutrients in Olive Leaves with Respect to Cultivar, Collection Period and Geographical Location for Their Targeted and Well-Timed Exploitation. Plants 2020, 9, 1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash, D.; Suri, S.; Upadhyay, G.; Singh, B.N. Total Phenol, Antioxidant and Free Radical Scavenging Activities of Some Medicinal Plants. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2007, 58, 18–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Shahzad, B.; Rehman, A.; Bhardwaj, R.; Landi, M.; Zheng, B. Response of Phenylpropanoid Pathway and the Role of Polyphenols in Plants under Abiotic Stress. Molecules 2019, 24, 2452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chintra, J.; Shivani, K.; Rekha, V. Bioactivity of secondary metabolites of various plants: A review. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Res. 2019, 10, 494–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takshak, S.; Agrawal, S.B. Defense Potential of Secondary Metabolites in Medicinal Plants under UV-B Stress. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 2019, 193, 51–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, S.M.; Chakraborty, D.; Dey, S. Phenolic Acids Act as Signaling Molecules in Plant-Microbe Symbioses. Plant Signal Behav. 2010, 5, 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El, S.N.; Karakaya, S. Olive Tree (Olea europaea) Leaves: Potential Beneficial Effects on Human Health. Nutr. Rev. 2009, 67, 632–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brockman, H.G.; Brennan, R.F. The Effect of Foliar Application of Moringa Leaf Extract on Biomass, Grain Yield of Wheat and Applied Nutrient Efficiency. J. Plant Nutr. 2017, 40, 2728–2736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Culver, M.; Fanuel, T.; Chiteka, A. Effect of Moringa Extract on Growth and Yield of Tomato. Greener J. Agric. Sci. 2012, 2, 207–211. [Google Scholar]

- Safi-Naz, S.Z.; Mostafa, M.R. Moringa Oleifera Leaf Extract Improves Growth, Physiochemical Attributes, Antioxidant Defence System and Yields of Salt-Stressed Phaseolus vulgaris L. Plants. Int. J. ChemTech Res. 2015, 8, 120–134. [Google Scholar]

- Prabakaran, M.; Kim, S.H.; Sasireka, A.; Chandrasekaran, M.; Chung, I.M. Polyphenol Composition and Antimicrobial Activity of Various Solvent Extracts from Different Plant Parts of Moringa Oleifera. Food Biosci. 2018, 26, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balal, R.M.; Shahid, M.A.; Javaid, M.M.; Anjum, M.A.; Ali, H.H.; Mattson, N.S.; Garcia-Sanchez, F. Foliar Treatment with Lolium perenne (Poaceae) Leaf Extract Alleviates Salinity and Nickel-Induced Growth Inhibition in Pea. Braz. J. Bot. 2016, 39, 453–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahid, M.A.; Balal, R.M.; Pervez, M.A.; Abbas, T.; Aqeel, M.A.; Javaid, M.M.; Garcia-Sanchez, F. Foliar Spray of Phyto-Extracts Supplemented with Silicon: An Efficacious Strategy to Alleviate the Salinity-Induced Deleterious Effects in Pea (Pisum sativum L.). Turk. J. Botany 2015, 39, 408–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd Elwahed, M.S.; Abd El-Aziz, M.E.; Shaaban, E.A.; Salama, D.M. New Trend to Use Biochar as Foliar Application for Wheat Plants (Triticum aestivum). J. Plant Nutr. 2019, 42, 1180–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, J.; Joseph, S. Biochar for Environmental Management. In Biochar for Environmental Management: Science, Technology and Implementation; Routledge: London, UK, 2024; pp. 1–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, P. Soil Carbon Sequestration and Biochar as Negative Emission Technologies. Glob. Change Biol. 2016, 22, 1315–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woolf, D.; Amonette, J.E.; Street-Perrott, F.A.; Lehmann, J.; Joseph, S. Sustainable Biochar to Mitigate Global Climate Change. Nat. Commun. 2010, 1, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yaseen, S.; Amjad, S.F.; Mansoora, N.; Kausar, S.; Shahid, H.; Alamri, S.A.M.; Alrumman, S.A.; Eid, E.M.; Ansari, M.J.; Danish, S.; et al. Supplemental Effects of Biochar and Foliar Application of Ascorbic Acid on Physio-Biochemical Attributes of Barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) under Cadmium-Contaminated Soil. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danish, S.; Tahir, F.A.; Rasheed, M.K.; Ahmad, N.; Ali, M.A.; Kiran, S.; Younis, U.; Irshad, I.; Butt, B. Effect of Foliar Application of Fe and Banana Peel Waste Biochar on Growth, Chlorophyll Content and Accessory Pigments Synthesis in Spinach under Chromium (IV) Toxicity. Open Agric. 2019, 4, 381–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mark, J.; Fantke, P.; Soheilifard, F.; Alcon, F.; Contreras, J.; Abrantes, N.; Campos, I.; Baldi, I.; Bureau, M.; Alaoui, A.; et al. Selected farm-level crop protection practices in Europe and Argentina: Opportunities for moving toward sustainable use of pesticides. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 477, 143577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anđelini, D.; Cvitan, D.; Prelac, M.; Pasković, I.; Černe, M.; Nemet, I.; Major, N.; Ban, S.G.; Užila, Z.; Ferri, T.Z.; et al. Biochar from Grapevine-Pruning Residues Is Affected by Grapevine Rootstock and Pyrolysis Temperature. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Major, N.; Išić, N.; Kovačević, T.K.; Anđelini, M.; Ban, D.; Prelac, M.; Palčić, I.; Ban, S.G.; Major, N.; Išić, N.; et al. Size Does Matter: The Influence of Bulb Size on the Phytochemical and Nutritional Profile of the Sweet Onion Landrace “Premanturska Kapula” (Allium cepa L.). Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, N.T.; Xuan, T.D. Foliar Application of Vanillic and P-Hydroxybenzoic Acids Enhanced Drought Tolerance and Formation of Phytoalexin Momilactones in Rice. Arch. Agron. Soil Sci. 2018, 64, 1831–1846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, G.H.; de Souza, J.A.R.; Macedo, W.R.; Pinto, F.G. Tyrosol, a Phenolic Compound from Phomopsis sp., Is a Potential Biostimulant in Soybean Seed Treatment. Phytochem. Lett. 2021, 43, 40–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mughal, A.; Jabeen, N.; Ashraf, K.; Sultan, K.; Farhan, M.; Hussain, M.I.; Deng, G.; Alsudays, I.M.; Saleh, M.A.; Tariq, S.; et al. Exploring the Role of Caffeic Acid in Mitigating Abiotic Stresses in Plants: A Review. Plant Stress 2024, 12, 100487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Fu, W.; Li, B.; Wang, Y.; Cheng, Y.; Kang, H.; Zeng, J.; Li, S.; Fu, W.; Li, B.; et al. Insight into Cd Detoxification and Accumulation in Wheat by Foliar Application of Ferulic Acid. Plants 2025, 14, 1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jhilik, N.Z.; Hoque, T.S.; Moslehuddin, A.Z.M.; Abedin, M.A. Effect of Foliar Application of Moringa Leaf Extract on Growth and Yield of Late Sown Wheat. Asian J. Med. Biol. Res. 2017, 3, 323–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafeez, A.; Tipu, M.I.; Saleem, M.H.; Al-Ashkar, I.; Saneoka, H.; Sabagh, A. El Foliar Application of Moringa Leaf Extract (MLE) Enhanced Antioxidant System, Growth, and Biomass Related Attributes in Safflower Plants. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2022, 150, 1087–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Rahman, S.S.A.; Abdel-Kader, A.A.S. Response of Fennel (Foeniculum vulgare, Mill) Plants to Foliar Application of Moringa Leaf Extract and Benzyladenine (BA). S. Afr. J. Bot. 2020, 129, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkuwayti, M.A.; El-Sherif, F.; Yap, Y.K.; Khattab, S. Foliar Application of Moringa Oleifera Leaves Extract Altered Stress-Responsive Gene Expression and Enhanced Bioactive Compounds Composition in Ocimum basilicum. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2020, 129, 291–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batool, S.; Khan, S.; Basra, S.M.A. Foliar Application of Moringa Leaf Extract Improves the Growth of Moringa Seedlings in Winter. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2020, 129, 347–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizwan, M.; Noureen, S.; Ali, S.; Anwar, S.; Rehman, M.Z.U.; Qayyum, M.F.; Hussain, A. Influence of Biochar Amendment and Foliar Application of Iron Oxide Nanoparticles on Growth, Photosynthesis, and Cadmium Accumulation in Rice Biomass. J. Soils Sediments 2019, 19, 3749–3759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.; Rizwan, M.; Noureen, S.; Anwar, S.; Ali, B.; Naveed, M.; Abd_Allah, E.F.; Alqarawi, A.A.; Ahmad, P. Combined Use of Biochar and Zinc Oxide Nanoparticle Foliar Spray Improved the Plant Growth and Decreased the Cadmium Accumulation in Rice (Oryza sativa L.) Plant. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2019, 26, 11288–11299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Ji, Q.; Rizwan, M.; Li, H.; Li, D.; Chen, G. Effects of Biochar and Foliar Application of Selenium on the Uptake and Subcellular Distribution of Chromium in Ipomoea Aquatica in Chromium-Polluted Soils. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2020, 206, 111184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filho, M.N.C.; Melo, L.C.A.; Lustosa Filho, J.F.; de Castro Paes, É.; de Oliveira Dias, F.; Lino Gomes, J.; Nick Gomes, C. Improved Tomato Development by Biochar Soil Amendment and Foliar Application of Potassium under Different Available Soil Water Contents. J. Plant Nutr. 2024, 47, 2620–2644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasiri, S.; Andalibi, B.; Tavakoli, A.; Delavar, M.A.; El-Keblawy, A.; Van Zwieten, L. Using Biochar and Foliar Application of Methyl Jasmonate Mitigates Destructive Effects of Drought Stress Against Some Biochemical Characteristics and Yield of Barley (Hordeum vulgare L.). Gesunde Pflanz. 2023, 75, 1689–1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafez, E.M.; Gowayed, S.M.; Nehela, Y.; Sakran, R.M.; Rady, A.M.S.; Awadalla, A.; Omara, A.E.D.; Alowaiesh, B.F. Incorporated Biochar-Based Soil Amendment and Exogenous Glycine Betaine Foliar Application Ameliorate Rice (Oryza sativa L.) Tolerance and Resilience to Osmotic Stress. Plants 2021, 10, 1930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiara Di Meo, M.; Izzo, F.; Rocco, M.; Zarrelli, A.; Mercurio, M.; Varricchio, E. Mid-Infrared Spectroscopic Characterization: New Insights on Bioactive Molecules of Olea europaea L. Leaves from Selected Italian Cultivars. Infrared Phys. Technol. 2022, 127, 104439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talhaoui, N.; Gómez-Caravaca, A.M.; Roldán, C.; León, L.; De La Rosa, R.; Fernández-Gutiérrez, A.; Segura-Carretero, A. Chemometric Analysis for the Evaluation of Phenolic Patterns in Olive Leaves from Six Cultivars at Different Growth Stages. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2015, 63, 1722–1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klisović, D.; Novoselić, A.; Lukić, M.; Kraljić, K.; Bubola, K.B.; Klisović, D.; Novoselić, A.; Lukić, M.; Kraljić, K.; Bubola, K.B. Thermal-Induced Alterations in Phenolic and Volatile Profiles of Monovarietal Extra Virgin Olive Oils. Foods 2024, 13, 3525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polić Pasković, M.; Vidović, N.; Lukić, I.; Žurga, P.; Majetić Germek, V.; Goreta Ban, S.; Kos, T.; Čoga, L.; Tomljanović, T.; Simonić-Kocijan, S.; et al. Phenolic Potential of Olive Leaves from Different Istrian Cultivars in Croatia. Horticulturae 2023, 9, 594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasković, I.; Lukić, I.; Žurga, P.; Germek, V.M.; Brkljača, M.; Koprivnjak, O.; Major, N.; Grozić, K.; Franić, M.; Ban, D.; et al. Temporal Variation of Phenolic and Mineral Composition in Olive Leaves Is Cultivar Dependent. Plants 2020, 9, 1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koprivnjak, O.; Majetić, V.; Bubola, K.B.; Kosić, U. Variability of Phenolic and Volatile Compounds in Virgin Olive Oil from Leccino and Istarska Bjelica Cultivars in Relation to Their Fruit Mixtures. Food Technol. Biotechnol 2012, 50, 216–221. [Google Scholar]

- Rasool, B.; Mahmood-ur-Rahman; Zubair, M.; Khan, M.A.; Ramzani, P.M.A.; Dradrach, A.; Turan, V.; Iqbal, M.; Khan, S.A.; Tauqeer, H.M.; et al. Synergetic Efficacy of Amending Pb-Polluted Soil with P-Loaded Jujube (Ziziphus mauritiana) Twigs Biochar and Foliar Chitosan Application for Reducing Pb Distribution in Moringa Leaf Extract and Improving Its Anti-Cancer Potential. Water Air Soil. Pollut. 2022, 233, 344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bibi, S.; Ullah, R.; Burni, T.; Ullah, Z.; Kazi, M. Impact of Resorcinol and Biochar Application on the Growth Attributes, Metabolite Contents, and Antioxidant Systems of Tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum Mill.). ACS Omega 2023, 8, 45750–45762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzadi, J.; Zaib-un-Nisa; Ali, N.; Iftikhar, M.; Shah, A.A.; Ashraf, M.Y.; Chao, C.; Shaffique, S.; Gatasheh, M.K. Foliar Application of Nano Biochar Solution Elevates Tomato Productivity by Counteracting the Effect of Salt Stress Insights into Morphological Physiological and Biochemical Indices. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 3205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muhammad Mehmood, H.; Yasin Ashraf, M.; Iqra Almas, H.; Zaib-un-Nisa; Ali, N.; Khaliq, B.; Ahmad Ansari, M.; Singh, R.; Gul, S. Synergistic Effects of Soil and Foliar Nano-Biochar on Growth, Nitrogen Metabolism and Mineral Uptake in Wheat Varieties. J. King Saud Univ. Sci. 2024, 36, 103392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasković, I.; Perica, S.; Pecina, M.; Hančević, K.; Polić Pasković, M.; Herak Ćustić, M. Leaf mineral concentration of five olive cultivars grown on calcareous soil. J. Cent. Eur. Agric. 2013, 14, 1488–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cukrov, M.; Ninkovic, V.; Maslov Bandić, L.; Marcelić, Š.; Palčić, I.; Franić, M.; Žurga, P.; Majetić Germek, V.; Lukić, I.; Lemić, D.; et al. Silicon-Mediated Modulation of Olive Leaf Phytochemistry: Genotype-Specific and Stress-Dependent Responses. Plants 2025, 14, 1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, X.; Guo, J.; Zheng, G.; Yang, J.; Yang, J.; Chen, T.; He, M.; Li, Y. Combination of Low-Accumulation Kumquat Cultivars and Amendments to Reduce Cd and Pb Accumulation in Kumquat Grown in Contaminated Soil. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 365, 132660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Zhao, Y.; Sima, J.; Zhao, L.; Mašek, O.; Cao, X. Indispensable Role of Biochar-Inherent Mineral Constituents in Its Environmental Applications: A Review. Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 241, 887–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graber, E.R.; Harel, Y.M.; Kolton, M.; Cytryn, E.; Silber, A.; David, D.R.; Tsechansky, L.; Borenshtein, M.; Elad, Y. Biochar Impact on Development and Productivity of Pepper and Tomato Grown in Fertigated Soilless Media. Plant Soil 2010, 337, 481–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, M.G.; Ascough, G.D.; Van Staden, J. Effects of Foliar Applications of Smoke-Water and a Smoke-Isolated Butenolide on Seedling Growth of Okra and Tomato. HortScience 2007, 42, 179–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mungkunkamchao, T.; Kesmala, T.; Pimratch, S.; Toomsan, B.; Jothityangkoon, D. Wood Vinegar and Fermented Bioextracts: Natural Products to Enhance Growth and Yield of Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.). Sci. Hortic. 2013, 154, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, R.; Joseph, S.; Shi, W.; Li, L.; Taherymoosavi, S.; Pan, G. Biochar DOM for Plant Promotion but Not Residual Biochar for Metal Immobilization Depended on Pyrolysis Temperature. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 662, 571–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Metabolite | PH | BCH | PH+BCH | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L | IB | L | IB | L | IB | |

| Oleuropein aglycone | −23.6 | +21.2 | −91.9 * | +972 | −86.6 | +1282 |

| Oleacein | −30.3 | +2.1 | −98.5 | +4689 | −96.9 | +6184 |

| Hydroxytyrosol | −17.3 | −26.7 | −63.6 | +201.6 | −58.8 | +115.8 |

| Luteolin | +15.5 | −20.7 | −38.6 | +44.7 | −43.6 | +54.0 |

| Luteolin-7-O-glucoside | −13.24 | −4.02 | −28.29 | +31.47 | −21.30 | +45.11 |

| Apigenin-7-O-glucoside | +15.2 | −10.7 | −65.3 | +207.7 | −84.6 | +54.5 |

| Flavones | +4.2 | −9.9 | −43.7 | +78.1 | −52.8 | +24.7 |

| Quercetin-3-glucoside (isoquercitroside) | −5.9 | −24.6 | −54.7 | +66.4 | −53.9 | +60.6 |

| Isorhamnetin | +5.5 | −26.9 | +80.5 | −58.3 | +105.5 | −62.6 |

| Chlorogenic acid | −9.9 | −2.2 | −87.4 | +614.8 | −86.7 | +595.1 |

| Element | PH | BCH | PH+BCH | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L | IB | L | IB | L | IB | |

| B | 34.7 | −2.0 | 70.1 * | −43.7 | 104.2 | −46.5 |

| Fe | −16.6 | 5.1 | 52.2 | −38.1 | 53.4 | −27.1 |

| K | 8.9 | 14.8 | −14.4 | 20.5 | −4.1 | 18.0 |

| Li | 2.0 | 14.1 | −54.1 | 12.3 | −73.9 | −65.4 |

| S | −2.8 | −1.8 | −6.6 | 6.5 | −9.4 | 7.1 |

| Se | −39.7 | 1.8 | 22.4 | 1.8 | 37.8 | 121.1 |

| Metabolite | Mean Dropout Loss |

|---|---|

| Catechin | 220.043 |

| Luteolin-7-O-glucoside | 196.196 |

| 3,4,5-Trihydroxybenzoic acid (gallic acid) | 192.579 |

| Flavanols | 186.273 |

| Apigenin-4-O-glucoside | 183.572 |

| Quercetin-4′-glucoside (spiraeoside) | 165.924 |

| Apigenin | 164.738 |

| Hydroxybenzaldehydes | 157.343 |

| Chlorogenic acid | 149.305 |

| Oleuropein aglycone | 148.162 |

| 3,4-Dihydroxybenzoic acid (protocatechuic acid) | 144.974 |

| Luteolin-7-O-rutinoside | 139.818 |

| Quercetin-3-rhamnoside (quercitrin) | 124.767 |

| Quercetin-3,4′-diglucoside | 123.736 |

| Vanillin | 112.430 |

| Flavones | 109.218 |

| Apigenin-7-O-glucoside | 105.699 |

| Luteolin-4-O-glucoside | 92.390 |

| 4-hydroxybenzoic acid | 88.941 |

| Ferulic acid | 77.077 |

| 2,5-Dihydroxybenzoic acid (Gentisic acid) | 74.333 |

| Isoferulic acid | 60.998 |

| Oleacein | 55.830 |

| Luteolin | 55.118 |

| Luteolin-4-O-rutinoside | 51.063 |

| Isorhamnetin-3-O-glucoside | 47.150 |

| Vanillic acid | 41.809 |

| Neochlorogenic acid | 35.428 |

| Quercetin-3-rutinoside (rutin) | 35.393 |

| Secoiridodis | 30.447 |

| Oleuropein | 26.513 |

| Phenolic acids | 25.758 |

| Hydroxytyrosol | 25.741 |

| Caffeic acid | 17.619 |

| Quercetin | 11.559 |

| Quercetin-3-glucoside (Isorquercitroside) | 11.164 |

| p-Coumaric acid | 10.306 |

| Isorhamnetin | 9.681 |

| Vanillic-4-glucoside | 5.733 |

| Hydroxycinnamic acids | 1.437 |

| Isorhamnetin-4′-glucoside | 1.364 |

| Verbascoside | 0.489 |

| Flavonols | 0.358 |

| Hydroxybenzoic acids | 0.204 |

| Dihydroquercetin (taxifolin) | 0.186 |

| Dihydroflavonols | 0.184 |

| Element | Mean Dropout Loss |

|---|---|

| Li | 182.558 |

| B | 70.275 |

| K | 66.834 |

| Na | 41.904 |

| Ca | 24.805 |

| P | 24.177 |

| Si | 23.311 |

| Mg | 21.907 |

| Se | 21.835 |

| Fe | 18.774 |

| S | 15.177 |

| Mn | 12.708 |

| Zn | 11.182 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Franić, M.; Palčić, I.; Marcelić, Š.; Major, N.; Ban, D.; Kovačević, T.K.; Anđelini, D.; Prelac, M.; Cvitan, D.; Goreta Ban, S.; et al. Modulating Secondary Metabolite Content in Olive Leaves Through Foliar Application of Biochar and Olive Leaf-Based Phenolic Extracts. Sustainability 2025, 17, 11290. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411290

Franić M, Palčić I, Marcelić Š, Major N, Ban D, Kovačević TK, Anđelini D, Prelac M, Cvitan D, Goreta Ban S, et al. Modulating Secondary Metabolite Content in Olive Leaves Through Foliar Application of Biochar and Olive Leaf-Based Phenolic Extracts. Sustainability. 2025; 17(24):11290. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411290

Chicago/Turabian StyleFranić, Mario, Igor Palčić, Šime Marcelić, Nikola Major, Dean Ban, Tvrtko Karlo Kovačević, Dominik Anđelini, Melissa Prelac, Danko Cvitan, Smiljana Goreta Ban, and et al. 2025. "Modulating Secondary Metabolite Content in Olive Leaves Through Foliar Application of Biochar and Olive Leaf-Based Phenolic Extracts" Sustainability 17, no. 24: 11290. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411290

APA StyleFranić, M., Palčić, I., Marcelić, Š., Major, N., Ban, D., Kovačević, T. K., Anđelini, D., Prelac, M., Cvitan, D., Goreta Ban, S., Užila, Z., Polić Pasković, M., & Pasković, I. (2025). Modulating Secondary Metabolite Content in Olive Leaves Through Foliar Application of Biochar and Olive Leaf-Based Phenolic Extracts. Sustainability, 17(24), 11290. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411290