Abstract

Achieving sustainable agricultural development necessitates a careful balance between the competing demands of environmental sustainability and food security. While extensive research has examined the economic impacts of agricultural parks, studies focusing on their environmental effects—particularly fertilizer usage—remain limited. Addressing this gap, this study investigates the impact of China’s National Modern Agricultural Industrial Parks (NMAIP) construction on fertilizer application using county-level panel data from 2014 to 2022. By leveraging the staggered establishment of these parks as a quasi-natural experiment, we apply a multi-period Difference-in-Differences (DID) approach. The results indicate that NMAIP construction led to a significant reduction in fertilizer use, a finding robust to a series of tests including parallel trends and placebo analyses. Mechanism analysis reveals that the reduction was primarily driven by enhanced agricultural labor and technology productivity. Heterogeneity analysis further shows that the effects were more pronounced in regions with high-level fertilizer consumption, in non-major grain-producing or wheat-producing areas, and in specialized or single-function parks. Importantly, this reduction in fertilizer use did not compromise grain output; instead, it was accompanied by stable or even increased production, thereby supporting food security. Our findings demonstrate that the NMAIP policy can achieve a “win-win” outcome by simultaneously promoting fertilizer reduction and safeguarding food security, offering a viable pathway toward sustainable agricultural development and food system resilience.

1. Introduction

The extensive application of chemical fertilizers has been a major driver of global agricultural economic growth [1,2]. However, long-term over-reliance on chemical inputs has generated severe environmental externalities, including soil degradation and agricultural non-point source pollution, which increasingly constrain the transition toward high-quality agricultural development. As the world’s largest fertilizer consumer, China has experienced both rapid growth in total fertilizer use and one of the highest application intensities globally. World Bank data (2002–2016) show that while global fertilizer consumption per hectare of arable land rose from 108.2 kg to 138.0 kg, China’s consumption increased from 335.8 kg to 463.2 kg per hectare—approximately 3.4 times the global average by 2016. This stark disparity highlights the challenge faces in reconciling fertilizer-driven yield gains with the goals of green and sustainable agricultural development.

In 2015, the Chinese government launched the “Zero Growth Action Plan for Fertilizer Use by 2020,” signaling a nationwide effort to curb fertilizer consumption. Yet by 2020, the fertilizer application intensity for key crops remained 1.39 times higher than the internationally recognized safety threshold of 225 kg per hectare [3], and fertilizer utilization efficiency was only 40.2% [4]. Such over-use not only erodes economic returns and weakens the international competitiveness of agricultural products, but also aggravates resource depletion, environmental pollution, and food safety risks, locking agricultural systems into a vicious cycle of “soil degradation–increased fertilizer use–further degradation” [5,6,7,8,9]. Against the backdrop of China’s shift from rapid growth to high-quality development, how to effectively reduce fertilizer use while safeguarding food security has thus become a central challenge for agricultural policy.

Existing research on fertilizer reduction has mainly focused on several themes. First, studies on agricultural production have analyzed how farmer behavior, resource endowments, and other micro-level factors influence fertilizer application [10,11]. Second, from a consumer perspective, some scholars advocate for establishing traceability systems for environmentally friendly products, which may steer consumer preference toward green alternatives and incentivize sustainable production [12,13]. Third, institutional and managerial studies have explored the role of land transfer, large-scale farming, and cooperative models in reducing fertilizer use [6,14,15]. Additionally, policy instruments such as economic incentives, green finance, and subsidy reforms have also been shown to significantly shape fertilizer application patterns [16,17,18,19,20]. These strands echo broader international debates on how institutional arrangements, market incentives, and behavioral interventions can jointly promote more environmentally efficient input use in agriculture, including technology-driven fertilizer reduction and sustainable intensification [21,22,23,24]. While considerable attention has been paid to scale operations and specialization as pathways to reduce fertilizer use, the potential role of agricultural modernization—particularly their environmental impacts and contribution to fertilizer reduction—remains underexplored.

The traditional model of agricultural modernization, characterized by fragmented organizational structures, has long constrained the growth of rural industries. National Modern Agricultural Industrial Parks (NMAIPs), as a core component of China’s supply-side structural reforms in agriculture, have emerged as key platforms for advancing green development and rural revitalization. Since the 1990s, China has promoted agricultural industrialization through various forms of agricultural parks. Unlike earlier models that were often sector-specific or limited in functional integration, NMAIPs are designed to build comprehensive industrial chains—spanning production, processing, technology, and marketing—with an emphasis on regional specialization. Under this model, land, capital, technology, and skilled labor are concentrated within a defined park area, where shared infrastructure and service platforms lower transaction costs and strengthen linkages along the value chain; this spatial and organizational concentration promotes industrial upgrading and accelerates the transition toward more sustainable farming systems [6,25]. In this sense, NMAIPs are closely related to the international experience of agro-industrial clusters and eco-industrial parks, which emphasize co-location of firms, shared services, and coordinated environmental management as a means of improving both economic performance and environmental efficiency [22,23,24]. Since the NMAIP program was launched in 2017, more than 20 billion yuan in central government funds have been allocated to establish 250 parks. These parks have contributed significantly to industrial restructuring, value-chain extension, and farmer income growth, establishing themselves as vital vehicles for rural revitalization and agricultural high-quality development.

Nevertheless, the existing literature has focused predominantly on NMAIP development models, performance evaluation, and operational challenges [25,26,27,28,29,30], with limited attention to their environmental impacts—particularly their effect on fertilizer application. Guided by green development principles, NMAIPs actively promote environmentally friendly agricultural practices, prioritize pollution prevention, enhance resource efficiency, and support the production of ecological and green products. These initiatives carry profound environmental implications. However, if the ecological function of these parks is overlooked and their development becomes solely driven by administrative targets, there is a risk of misallocating agricultural resources, which could ultimately undermine the sustainability of the agricultural sector.

Therefore, utilizing a multi-period Difference-in-Differences (DID) model and county-level data from 1289 Chinese counties (2014–2022), the impact of NMAIP construction on fertilizer use is examined, with particular attention to its implications for the foundational goal of food security [9,31]. This study contributes to the literature in several key aspects. First, it shifts the focus from the predominantly economic assessments of NMAIP to their environmental impacts, specifically their role in reducing fertilizer application. This addresses a critical gap in understanding the ecological consequences of NMAIP development. At the same time, the analysis speaks to the international literature on agricultural industrial clusters and environmental efficiency by providing large-scale quasi-experimental evidence on whether cluster-based modernization can simultaneously improve productivity and reduce chemical input intensity [23,24]. Methodologically, this research employs a rigorous quasi-experimental design, using county-level panel data and a multi-period DID approach to identify the causal effect of NMAIP establishment on fertilizer use. This strategy effectively controls for unobserved time-invariant confounders, significantly enhancing the credibility of the findings.

Furthermore, this study delves into the underlying mechanisms and heterogeneous effects. It examines how NMAIP construction influences fertilizer use through the lens of production efficiency and explores variations across regional fertilizer consumption levels, functional orientations, crop systems, and park types. These results contribute to ongoing international discussions on technology-driven fertilizer reduction by showing how combinations of mechanization, digital technologies, and organizational innovation embedded in territorial clusters can reshape fertilizer demand.

Finally, by integrating the core objective of food security into its framework, this study moves beyond a singular focus on input reduction. It investigates the synergy between fertilizer reduction and stable grain production, offering a theoretical and practical foundation for achieving a “win-win” outcome that balances environmental sustainability with food availability. Taken together, the findings not only enrich the evidence base on China’s agricultural green transition but also provide a reference point for other countries exploring cluster-based approaches to reconcile agricultural growth with environmental sustainability.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 delineates the background and formulates the theoretical hypotheses underpinning the study. Section 3 discusses the data collection process and the methodological framework employed in the analysis. Section 4 presents the baseline regression results, conducts robustness tests, explores the mechanisms at play, and examines potential heterogeneity within the data. Section 5 is dedicated to discuss the relationship between reducing fertilizer use and increasing grain production. Finally, Section 6 summarizes the findings, discusses their implications, and offers conclusions.

2. Policy Background and Theoretical Mechanisms

2.1. Policy Background

Beginning in the 1990s, China has actively explored ways to transform and upgrade its traditional agricultural sector, focusing mainly on developing agricultural parks. These parks are central to creating a multi-level, diversified system to promote agricultural growth and increase farmers’ incomes. The industrial revolution and significant shifts in the economic and social landscape have influenced the transformation of China’s agricultural industry. Alongside economic development and structural changes, the rise of large-scale, centralized agricultural production has marked the beginning of agriculture’s modernization [26,32].

Agricultural industrial parks, which consist of geographic clusters of related firms, provide essential infrastructure such as roads, electricity, communications, warehousing, packaging, wastewater treatment, logistics, transportation, and laboratory facilities. These parks enable firms involved in agricultural production, processing, and marketing to achieve economies of scale, creating positive externalities that benefit the broader industry [33,34]. As such, agricultural industrial parks are critical drivers of agricultural industrialization, improving production efficiency and advancing scientific and technological progress. Over time, the development of agricultural industrial parks in China has gained significant momentum, evolving into a robust, mature model for agricultural industrialization.

Entering the 21st century, particularly by the end of 2016, China introduced the concept of NMAIP integrating “production + processing + science and technology.” These parks, centered on large-scale breeding bases, emphasize the role of key enterprises in driving agricultural industrialization. The goal is to create an environment where modern production factors converge, fostering synergies across production, research and development, and market integration. The scope and functions of these parks have expanded significantly, evolving from a focus solely on agricultural production to include farm research and development (R&D) and deep integration with the market.

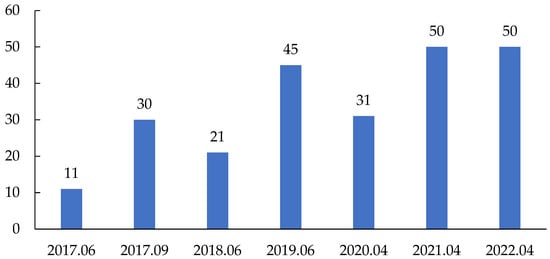

In March 2017, the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs (MARA) and the Ministry of Finance (MOF) jointly issued the “Notice on the Creation of National Modern Agricultural Industrial Parks,” outlining specific criteria for NMAIP establishment, construction goals, and related policy specifications. By the end of 2022, 250 NMAIPs had been approved across seven batches for inclusion in the national management system. Figure 1 illustrates the timeline and number of parks created in each batch. Most of these parks are established at the county level, with management and guidance provided through annual documents issued by the MARA and the MOF to ensure standardized construction and operation.

Figure 1.

Batch-wise timeline of the NMAIP initiative (2017–2022).

It is important to note that the establishment of NMAIP affects not only agricultural production and industrial development but also the structure and efficiency of agricultural input use, particularly chemical fertilizers. Policy-driven infrastructure upgrades, technology extension, and organizational innovation within these parks are expected to promote more efficient and environmentally friendly fertilization practices. Consequently, the staggered rollout of NMAIPs across counties provides a policy shock that can be treated as a quasi-natural experiment for this study, enabling us to identify their impact on fertilizer use and related environmental outcomes in agricultural production.

2.2. Theoretical Mechanisms

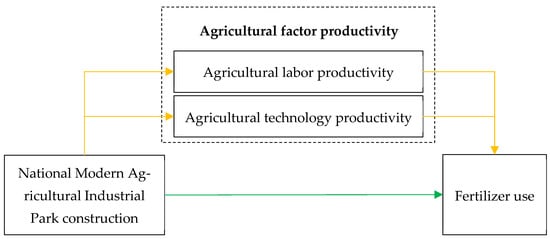

The construction of NMAIP represents a significant transformation in agricultural development. These parks are centered on efficient resource allocation and optimization of production models, emphasizing improving production efficiency. This study explores two key dimensions through which NMAIP may reduce fertilizer use: agricultural labor and technology productivity. These dimensions correspond to the fundamental elements of agricultural production: labor and technology inputs. Improvements in both areas directly affect economic efficiency and resource utilization, which can, in turn, lead to reduced chemical fertilizer consumption [1,27].

Agricultural labor productivity refers to the output generated per unit of labor input. In traditional farming systems, laborers rely heavily on chemical fertilizers and pesticides to boost yields. However, this model is inefficient and heavily dependent on human labor and chemical inputs, leading to considerable resource waste. Improvements in labor productivity can lower labor costs and shorten production time and, in turn, significantly diminish the use of chemical fertilizers [35]. In contrast, agricultural technology productivity involves enhancing the overall efficiency of agricultural production through technological innovations that enable higher output with fewer resources. The development of NMAIP typically aligns with the widespread adoption of advanced technologies such as big data analytics, Artificial Intelligence (AI), and the Internet of Things (IoT). These innovations have markedly increased agricultural productivity while reducing reliance on chemical fertilizers [36].

It is important to note that agricultural labor and technology productivity are closely interconnected, with improvements in both often progressing simultaneously [1]. In NMAIPs, increases in labor efficiency are frequently supported by technological advancements, while technological innovations rely on the rational allocation and effective utilization of labor. For instance, intelligent machinery allows agricultural workers to operate equipment more efficiently, thus reducing labor intensity. At the same time, technological progress enhances crop output quality, further decreasing the need for excessive fertilizer use.

In conclusion, by enhancing agricultural labor and technology productivity, NMAIP construction optimizes agricultural production models, reducing chemical fertilizer usage (Figure 2). This mechanism not only supports the goals of sustainable agriculture and green development but also lays a strong foundation for the long-term sustainability of the agricultural sector.

Figure 2.

Theoretical analysis framework.

2.2.1. Agricultural Labor Productivity

Improving agricultural labor productivity is a primary objective in constructing the NMAIP and a key strategy for reducing fertilizer use [35]. As global attention increasingly focuses on environmental protection and sustainable development, transforming agricultural practices has become essential. Improving agricultural labor productivity enhances agricultural efficiency, reduces resource consumption, and mitigates environmental impacts. Within the NMAIP framework, agricultural labor productivity has been significantly enhanced by adopting advanced agricultural technologies and scientific resource management systems. These improvements are reflected in higher crop yields, lower production costs, and, most importantly, more precise regulation of fertilizer use.

First, NMAIP construction improves agricultural labor productivity by optimizing labor organization. Traditional agriculture is often characterized by fragmented and decentralized labor structures, leading to inefficient resource allocation, redundant labor inputs, and excessive fertilizer use [37]. In contrast, NMAIP adopts an intensive, large-scale operational model that optimizes labor allocation and task division, enhancing worker efficiency. This model reduces over-reliance on chemical fertilizers and minimizes waste [38].

Second, NMAIP construction increases agricultural labor productivity by implementing standardized production processes. Standardized management improves production efficiency and ensures more precise fertilizer use through optimized labor division and resource allocation. Within these parks, agricultural production follows well-defined standards and plans, particularly for fertilizer application. Precision fertilization technologies and scientifically developed nutrient ratios enable workers to apply fertilizers based on specific crop needs [39]. This refined management leads to significant productivity gains, allowing the workers to complete tasks efficiently while preventing fertilizer overuse [40].

Additionally, NMAIP construction enhances agricultural labor productivity through collaborative models, such as farmers’ cooperatives, contributing to reduced fertilizer use. These cooperatives serve as organized platforms for cooperation, facilitating the sharing and rational allocation of labor resources [41]. By collectively purchasing inputs such as fertilizers and seeds and sharing knowledge and best practices, cooperatives improve labor efficiency and ensure fertilizers are applied according to a unified plan, thus preventing overuse due to individual misjudgments [42,43].

In conclusion, improving agricultural labor productivity is central to constructing NMAIP. Intensive management, standardized operations, and cooperative collaboration have significantly enhanced agricultural labor productivity. These innovations enable precise control over fertilizer use, contributing to both increased production efficiency and more sustainable agricultural practices [10,39]. Based on these findings, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 1.

The construction of NMAIP can reduce fertilizer use by improving agricultural labor productivity.

2.2.2. Agricultural Technology Productivity

The construction of NMAIP plays a pivotal role in enhancing agricultural technology productivity and promoting sustainable agricultural development, particularly by reducing fertilizer use [44]. Numerous studies have shown that industrial agglomerations, especially those within urban development zones, facilitate the efficient alignment of specialized production factors, services, and technologies. These zones provide supportive environments, economies of scale, and innovation-driven policies, which foster technology spillovers, accelerate innovation, and promote knowledge transfer—all of which enhance agricultural production processes [28,45]. As a key form of agricultural and industrial agglomeration, NMAIP benefit significantly from these effects, which are crucial for reducing reliance on chemical fertilizers.

First, NMAIP construction facilitates the introduction of advanced agricultural technologies. These parks are often established as hubs for the research, development, and application of advanced agricultural technologies and equipment, with substantial government involvement. Through policy support and financial incentives, NMAIP construction creates conducive environments for introducing advanced agricultural technologies and lays the groundwork for transforming agricultural production methods [46]. Integrating advanced technologies such as precision fertilization and intelligent agricultural management systems has significantly enhanced production efficiency, making agricultural processes more resource-efficient and sustainable [47,48]. Precision fertilization, for example, dynamically adjusts inputs based on soil conditions and crop needs, reducing the overuse of fertilizers in traditional farming practices [44].

Second, the construction of NMAIP stimulates breakthroughs in advanced agricultural technologies. Policies that incentivize innovation, combined with the scale effects of resource agglomeration and cross-industry collaboration, reduce R&D costs and risks for enterprises. As a result, businesses within the parks are better positioned to invest in R&D, leading to technological breakthroughs that align with the specialized needs of the parks’ industries. Additionally, the competitive environment within NMAIP accelerates technological innovation, driving the development of advanced agricultural production and processing technologies. By adopting these more efficient technologies, NMAIP construction further reduces dependence on chemical fertilizers, supporting the goal of fertilizer reduction [12,36].

Third, the NMAIP construction facilitates the diffusion of advanced agricultural technologies. The geographic proximity of enterprises within these parks encourages the exchange of tacit knowledge and the disseminating of the latest technological advancements [28]. This diffusion occurs horizontally—through technology transfer and collaboration among different enterprises—and vertically—across agricultural production and processing chains. By fostering cooperation between production and processing enterprises, NMAIP construction helps disseminate agricultural technologies, particularly in regions with less developed infrastructure. As a result, technology sharing reduces reliance on chemical fertilizers and supports adopting green farming practices [49,50].

In conclusion, NMAIP construction is essential for introducing, stimulating, and facilitating advanced technologies. Through the agglomeration effect and knowledge-sharing mechanisms, these parks significantly enhance the technical capabilities of the agricultural sector. Technological advancements increase agricultural productivity and provide a strong foundation for reducing fertilizer use. Advanced technologies, such as precision fertilization and intelligent management systems, ensure more targeted and efficient fertilizer use. Therefore, NMAIP construction is crucial in advancing agricultural technology, reducing fertilizer dependence, and promoting sustainable development. Based on these insights, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 2.

The construction of NMAIP can reduce fertilizer use by enhancing agricultural technology productivity.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data Sources

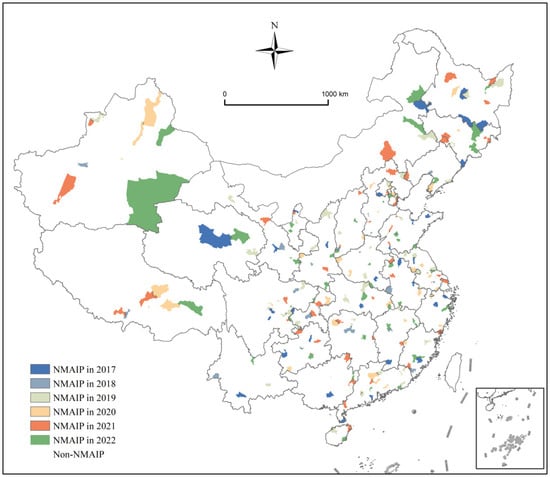

This study utilizes an unbalanced panel dataset of 1289 counties in China from 2014 to 2022. The primary dependent variable is county-level chemical fertilizer use. Fertilizer data are obtained from the agriculture chapters of the China County Statistical Yearbook, the China Statistical Yearbook for Regional Economy, and provincial, municipal, and county statistical yearbooks, supplemented by the EPS database [51]. These sources report the annual quantities of nitrogen, phosphate, potash and compound chemical fertilizers actually applied in agricultural production. So we can construct the total amount of chemical fertilizers used in each county-year. The list of NMAIP is compiled from official documents jointly issued by the MARA and MOF, ensuring comprehensive coverage of all officially recognized parks (Figure 3). To guarantee at least one year of post-implementation observation for identifying the fertilizer reduction effect, the 50 NMAIPs designated in 2023 are excluded from the sample. Data on economic, agricultural, and social development used as control variables are primarily sourced from the China Statistical Yearbook for Regional Economy and the China County Statistical Yearbook, complemented by provincial, municipal, and county statistical yearbooks. The study also consults the National Economic and Social Development Statistical Bulletin and relevant datasets from the EPS platform to supplement missing indicators. During data cleaning and processing, counties with extensively missing data were removed to ensure the completeness and representativeness of the dataset. For sporadically missing observations, interpolation methods were applied so as to minimize their impact on the empirical analysis.

Figure 3.

Spatial distribution of the NMAIP in batches (2017–2022).

3.2. Variable Selection

The definitions of variables and their descriptive statistics are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Definitions of variable and descriptive statistics.

3.2.1. Dependent Variable

Fertilizer use is the primary dependent variable in this study and is measured by the standardized amount of fertilizer applied. The standardized amount represents a conversion of various fertilizer types based on nutrient content, reflecting actual fertilizer usage more accurately. To ensure the robustness and comprehensiveness of the model, alternative measures are also included in the robustness tests, such as fertilizer use per unit area and average fertilizer application per laborer. This approach accounts for regional land-use variations and labor inputs, minimizing potential biases.

3.2.2. Key Independent Variable

The key independent variable is a dummy variable indicating whether a county has established an NMAIP. The establishment of an NMAIP is identified for each county based on the NMAIP creation list published by the MARA and MOF. The year each county first appeared on this list is considered the starting year for the NMAIP construction. A binary variable, NMAIP, is created, where counties involved in the construction of an NMAIP are assigned a value of 1 for the corresponding year, and counties not involved are assigned a value of 0.

From an identification perspective, the NMAIP program can be regarded as a quasi-natural experiment for at least three reasons. First, the total number of NMAIP in each batch is determined at the central level, and quotas are allocated across provinces according to national strategic considerations, rather than short-run fluctuations in county-level fertilizer use. Second, candidate counties must satisfy a set of relatively time-invariant or slowly changing conditions to be eligible for application. These structural advantages may affect the level of fertilizer use but are unlikely to be closely tied to the timing of NMAIP approval; in the empirical model, they are absorbed by county fixed effects, while time-varying controls further mitigate confounding from observable differences. Third, the timing of park designation is largely driven by ministerial planning cycles, evaluation schedules, and cross-regional coordination, generating staggered policy shocks across counties whose short-term trajectories of fertilizer use would otherwise be similar. We acknowledge that policy targeting cannot be completely random and that NMAIP placement may still exhibit some selection on observables. To address this concern, the baseline DID design is complemented by a Propensity Score Matching and Difference-in-Differences (PSM-DID) approach in which treated counties are matched to comparable control counties based on pre-treatment characteristics. Also, under the parallel-trend assumption, the staggered introduction of NMAIPs can be interpreted as providing plausibly exogenous variation for identifying the average treatment effect of NMAIP construction on fertilizer application.

3.2.3. Control Variables

To strengthen the model’s explanatory power and enhance the robustness of the results, several control variables are incorporated to account for factors that may influence fertilizer use [10,12,20,39,52]. These include economic development, agricultural development, financial development, infrastructure development, financial revenue, farmers’ income, human capital, and population density. Specifically, first, economic development is positively associated with fertilizer use, as higher economic levels tend to stimulate agricultural modernization, thereby increasing fertilizer demand. Second, the share of the primary sector, which represents agricultural development, captures the local economy’s reliance on agriculture and its subsequent effect on fertilizer application. Third, financial development plays a crucial role in facilitating agricultural production by improving access to credit, particularly for NMAIP-related investments. Fourth, fixed investment may indirectly shape fertilizer use by promoting the development of agricultural infrastructure. Fifth, budgetary revenue, which reflects local government fiscal capacity, influences agricultural input structures through public spending. Sixth, rural residents’ income affects farmers’ purchasing power for fertilizers, with higher income potentially leading to greater use in pursuit of higher crop yields. Seventh, human capital, representing the education and skill level of the labor force, influences the adoption of modern agricultural technologies, thereby improving fertilizer use efficiency. Finally, population density affects land use intensity and farming structures, which in turn shape fertilizer application patterns. By including these control variables, this study ensures a more accurate estimation of the effect of NMAIP construction on fertilizer use.

3.2.4. Mechanism Variables

This study examines agricultural labor and technology productivity as mediating mechanisms. Agricultural labor productivity is defined as the gross output value of agriculture, forestry, and fisheries per employee, while agricultural technology productivity is measured as the total power of agricultural machinery per unit of sown crop area.

3.3. Empirical Strategy

This study’s empirical strategy to evaluate the impact of NMAIP construction on fertilizer use treats the phased rollout of NMAIP as a quasi-natural experiment. The causal effect is identified using a multi-period DID model [53], which compares counties designated as NMAIP (the treatment group) with non-NMAIP counties. The baseline regression model is specified as follows:

In Equation (1), FUi,t represents fertilizer use of county i in year t, which is the dependent variable. NMAIPi,t is the key independent variable, indicating the implementation of NMAIP construction. It is a binary variable where NMAIPi,t = 1 if county i implemented the policy in year t, and NMAIPi,t = 0 otherwise. The coefficient α1 is the primary parameter of interest, capturing the average effect of NMAIP construction on fertilizer use. Xi,t denotes a set of control variables, including economic development, agricultural development, financial development, and others, included to account for potential confounding factors. The item αn represents the regression coefficient for each control variable. The item μi denotes county-fixed effects, controlling for time-invariant, county-specific characteristics such as geographic location, resource endowment, and historical economic development. The item δt represents time-fixed effects, which control for common temporal shocks like macroeconomic trends and nationwide policy changes. Finally, εi,t is the idiosyncratic error term, capturing all unobserved factors that vary over time and across counties.

4. Results

4.1. Baseline Regression

Table 2 presents the detailed results of the baseline regressions examining the impact of NMAIP construction on fertilizer use. In column (1), the model controls only for county and year-fixed effects without including additional county-level variables. The regression results indicate that the NMAIP variable is significant at the 1% level, with a negative coefficient. This suggests that the construction of NMAIP has a significant negative impact on fertilizer use, providing preliminary support that NMAIP construction can effectively reduce fertilizer application. Columns (2) to (4) introduce additional county-level control variables, which help refine the assessment of the independent effect of NMAIP construction. The results indicate that, even after accounting for these factors, the significance of the NMAIP variable remains unchanged, reinforcing the reliability of the initial findings. This suggests that the negative effect of NMAIP construction on fertilizer use is not driven by other economic variables and highlights the park’s consistent role in reducing fertilizer application. Taking column (4) as an example, the key independent variable NMAIP remains significant at the 1% level, with a regression coefficient of −0.212. In other words, the establishment of an NMAIP led to a 21.20% reduction in fertilizer use compared to counties without such parks. This result indicates that the construction of NMAIP plays a significant role in promoting fertilizer reduction.

Table 2.

Baseline regression results of NMAIP construction on fertilizer use.

4.2. Robustness Tests

4.2.1. Parallel Trend Test

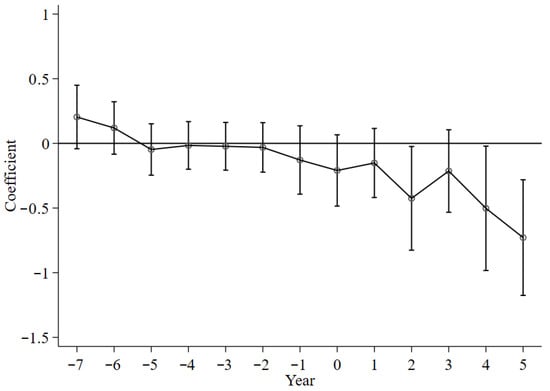

To ensure the validity of the DID methodology, this study conducted a rigorous pretest based on the parallel trends hypothesis. The parallel trends assumption posits that, in the absence of the NMAIP policy, the trends in fertilizer use for both the treatment and control counties should follow similar trajectories over time. This research employs the event study method to test whether this assumption holds and to investigate the dynamic effects of NMAIP construction on fertilizer use.

Figure 4 plots the estimated coefficients for each lead and lag of NMAIP implementation together with their confidence intervals. On the pre-treatment side, the coefficients for all lead terms are close to zero and their confidence intervals clearly include zero; moreover, the intervals substantially overlap across pre-policy years, indicating that there is no systematic upward or downward pattern in fertilizer use between treated and control counties before park establishment. This visual and statistical evidence suggests that, conditional on controls, the treatment and control groups followed comparable trends in fertilizer use prior to the policy shock, which supports the parallel trends assumption and provides a solid foundation for the subsequent DID analysis.

Figure 4.

Dynamic effects of NMAIP policy on fertilizer use.

In terms of dynamic effects, the impact of NMAIP construction on fertilizer use appears to manifest with a delayed response. As shown in Figure 4, the post-treatment coefficients gradually become negative after policy implementation, and from approximately the second year onward the confidence intervals no longer overlap zero, indicating a statistically significant decline in fertilizer use in treated counties relative to the control group.

Notably, in the second year following the policy’s implementation, fertilizer use in the treatment group decreased significantly, and this reduction continued to intensify in subsequent years. This gradual divergence suggests that the policy’s effect was not immediate but accumulated over time. Several factors may explain this delayed effect. Initially, the NMAIP policy may have provided early-stage incentives. However, its more substantial impact on fertilizer use became evident only as agricultural production technologies improved, precision fertilizer application techniques were promoted, and the agricultural industry chain was optimized. These changes take time to influence production practices, meaning the policy’s effects were not immediately visible. However, the effect became more pronounced from the second year onward. Additionally, the policy’s lagged effects may vary across regions. Adapting to new agricultural models may have taken longer in areas with a high dependency on chemical fertilizers. In contrast, regions with a stronger focus on green agriculture likely experienced a more immediate response. Overall, the dynamic effect analysis demonstrates that the construction of NMAIP does not immediately reduce fertilizer use. Instead, its effects materialize progressively, with a sustained decline in fertilizer use resulting from continued policy implementation and the gradual transformation of agricultural practices.

4.2.2. Heterogeneous Treatment Effect Test

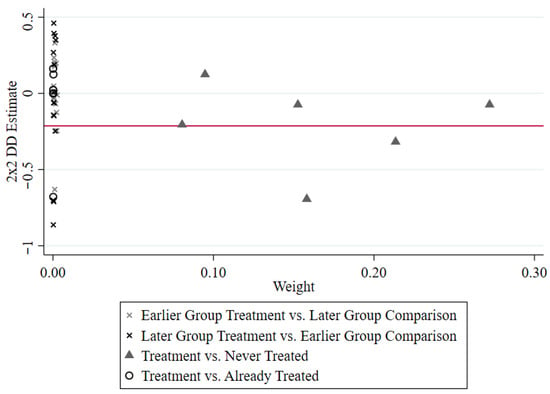

In analyzing the impact of NMAIP construction on fertilizer use, the traditional multi-period DID model with two-way fixed effects may be subject to estimation bias due to heterogeneous treatment effects. This issue arises because NMAIP construction is implemented in different batches across regions, resulting in temporal heterogeneity. Since the policy does not affect all regions simultaneously, the weighted average effects derived from the DID model may not accurately reflect each group’s treatment effects. To test for potential estimation bias, this study applies the diagnostic methods proposed by Goodman-Bacon (2021) [54] and Chaisemartin and D’Haultfoeuille (2024) [55], which are designed to assess the reliability of two-way fixed effects estimators in a multi-period DID framework.

The Goodman-Bacon (2021) [54] approach decomposes the total DID estimator into a weighted average of four distinct categories to evaluate the impact of different groupings on the overall estimation. The decomposition results in Figure 5 and Table 3 illustrate the weights assigned to each category and their contribution to the final estimates. Specifically, the results show that the control group, consisting of counties treated later, accounts for 97.10% of the total weight. This indicates that the DID estimates in this study are predominantly derived from counties not yet affected by the policy, thereby avoiding the potential bias that could arise from over-reliance on counties in the treatment group that experienced later policy implementation. As a result, the estimates in this study are robust and not subject to substantial estimation bias.

Figure 5.

Distribution of two-way fixed effects estimation bias weights.

Table 3.

Bacon decomposition results.

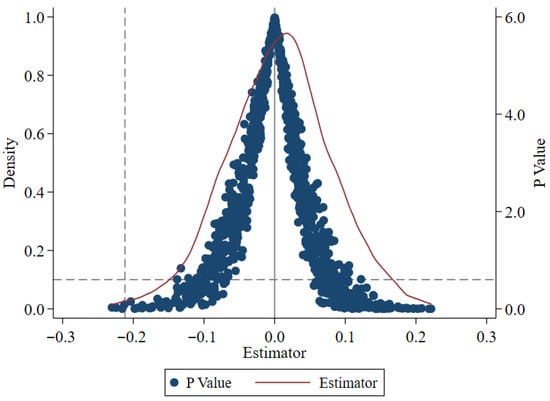

4.2.3. Placebo Test

A placebo test is conducted to ensure the robustness of the results and to rule out the influence of non-randomized policy shocks or potential unobservable confounders. Specifically, this study randomly reassigned the treatment groups and simulated hypothetical policy implementation time points. A regression analysis was then performed on these placebo groups, repeated 1000 times, to assess the stability and consistency of the results across simulated scenarios.

Figure 6 presents the results of the placebo test, showing that the estimated coefficients for the simulated groups follow an approximately normal distribution centered on zero. This indicates that the effect of the placebo groups is negligible and symmetrically distributed, with no evidence of systematic bias. Additionally, most placebo estimates exhibit p values greater than 0.1 (approximately 77%), suggesting that their effects are statistically insignificant. These findings confirm that random factors and unobservable confounding variables did not significantly influence the estimated policy effects in this study. Therefore, the placebo test supports the conclusion that the observed policy effects are not driven by external random factors or unobserved confounders.

Figure 6.

Distribution of placebo estimates from 1000 simulations.

4.2.4. Sample Self-Selection Discussion

During the construction of NMAIP, systematic differences may exist between counties that have established NMAIP and those that have not. These differences could affect the comparability of the treatment and control groups, potentially leading to biased estimates of policy effects. To mitigate this issue, this study employs the PSM-DID method, which integrates PSM with DID to control for systematic biases and enhance the reliability and accuracy of the estimation results. Multiple matching methods are utilized to further strengthen the matching process, including nearest neighbor matching and caliper matching. Table 4 presents the results of PSM-DID test under different matching methods. The findings indicate that, even after matching, the coefficients of the key independent variables remain statistically significant and retain the same negative direction. This suggests that the potential influence of non-random selection has been effectively addressed, further supporting the conclusion that the construction of NMAIP plays a critical role in reducing fertilizer use.

Table 4.

PSM-DID test results.

4.2.5. Controlling for Other Relevant Policies

During the study period, several policies other than the construction of NMAIP may have influenced fertilizer use [17,19]. To account for these potential confounding factors and ensure the accuracy and robustness of the results, this study incorporates controls for a range of relevant policies. These policy controls help isolate the direct impact of NMAIP construction on fertilizer use.

First, land improvement has been identified as a key factor affecting agricultural fertilizer use [27,28]. During the study period, China implemented the Comprehensive Territorial Land Management (CTLM) policy to accelerate land remediation efforts nationwide, aiming to enhance agricultural productivity and reduce resource waste. Based on the specific implementation of the CTLM policy in each region, this study includes corresponding policy indicators in the regression model to control for its potential impact.

In addition to the land remediation policy, several other policy measures are considered. For example, the Integrated Urban-Rural Transportation Construction (IURTC) policy could influence agricultural production methods and fertilizer use by improving the distribution efficiency of agricultural products. Similarly, the Rural Homestead Reform (RHR) policy, aimed at optimizing rural land resource allocation, may indirectly affect agricultural production and fertilizer use by influencing rural labor mobility and land use efficiency [56].

Furthermore, the E-commerce into Rural Areas (ERA) policy has promoted the digitalization of rural areas, particularly in the marketing of agricultural products and the application of smart agricultural technologies. The spread of e-commerce may have contributed to the modernization of agricultural practices, thereby influencing fertilizer usage patterns [12].

Finally, we explicitly consider national policies that directly target chemical fertilizer reduction. In February 2015, the MARA issued the “Zero Growth Action Plan for Fertilizer Use by 2020,” which for the first time set a quantitative target of zero growth in fertilizer use and launched the fertilizer zero-growth action (FZA) policy in 48 pilot counties. To capture the potential influence of this initiative, we construct a policy dummy for counties participating in the FZA and interact it with the post-2015 period, and include this term in the regression model. This specification helps net out the incremental impact of the national fertilizer-reduction campaign, so that the estimated coefficient on NMAIP construction reflects the effect of park establishment over and above contemporaneous national efforts to curb fertilizer use.

Table 5, Columns (1) to (6), presents the estimation results after controlling for these policies. The results consistently show that the impact of NMAIP construction on fertilizer use remains statistically significant, with the coefficients retaining their negative sign across all specifications. In conclusion, after accounting for the influence of other potentially confounding policies, this study confirms that the suppressive effect of NMAIP construction on fertilizer use remains significant and robust.

Table 5.

The regression results of controlling for other relevant policies.

4.2.6. Other Robustness Tests

This study performs several additional robustness tests to ensure the reliability and broad applicability of the findings and to further validate the baseline regression results. The details of these tests and their outcomes are as follows.

First, the model incorporates province-year interaction fixed effects to control for potential regional heterogeneity. Agricultural policies in China, particularly those targeting fertilizer reduction, vary considerably across provinces. Different provinces may adopt distinct strategies for reducing fertilizer application, which could affect the results. By including province-year interaction fixed effects, this study accounts for such regional differences, yielding a more accurate assessment of the impact of NMAIP construction on fertilizer use. The results, presented in Column (1) of Table 6, show that after including these fixed effects, the regression estimates remain stable, confirming the robustness of the baseline findings.

Second, the analysis excludes data from municipalities directly under the central government, such as Beijing and Shanghai, which possess unique administrative statuses and economic structures that differ substantially from those of typical provinces. Their relatively low agricultural output and distinctive industrial development patterns could bias the policy evaluation. To mitigate this potential bias, the study omits data from these cities. As shown in Column (2) of Table 6, even after excluding these atypical observations, the regression results remain stable and consistent, further supporting the robustness of the findings.

Third, the physical and economic scale of NMAIPs is not uniform, and some parks cover only a few towns within a county. This raises a legitimate concern that using county-level fertilizer use as the outcome variable may dilute the measured impact for relatively small parks. Ideally, one would directly exclude parks below a certain area or coverage threshold; however, the official documents for NMAIPs do not provide standardized data on park area or the proportion of county agricultural land included, making it infeasible to implement such a size-based exclusion rule. To address this issue indirectly, we restrict the sample by dropping counties where the share of the primary industry in GDP is very low (bottom 20 percent). In these counties, agricultural production accounts for a small fraction of local economic activity, and any NMAIP, if present, is more likely to occupy only a limited part of the county, so county-level fertilizer use is a relatively noisy proxy for the park-level input. By contrast, in counties with a higher agricultural share, NMAIPs typically represent a larger share of agricultural land and input use, making county-level fertilizer data a more accurate reflection of the treatment intensity. The re-estimated result on this restricted subsample in Columns (3) of Table 6 is highly consistent with the baseline findings in terms of sign, magnitude, and statistical significance, suggesting that our conclusions are not driven by small-scale parks or by the mismatch between park and county boundaries.

Fourth, the key independent variable is re-measured to test the reliability of the results under alternative specifications. Specifically, the cumulative number of years since NMAIP implementation is used to replace the original binary indicator, allowing an examination of how the duration of policy exposure influences fertilizer use. The results in Column (4) of Table 6 indicate that fertilizer use declines significantly with the increasing number of years under NMAIP construction, further corroborating the reducing effect of the policy.

Finally, fertilizer use per unit area and fertilizer application per agricultural worker are used as alternative dependent variables to test the robustness of the results. This approach adjusts for regional differences in land use and labor input, reducing potential estimation bias. The findings, reported in Columns (5) and (6) of Table 6, demonstrate that the effect of NMAIP construction remains statistically significant under these alternative measures, confirming the consistency of the policy effect across different model specifications.

In conclusion, the results of these robustness tests show that the reducing effect of NMAIP construction on fertilizer use persists across a variety of model specifications. These additional tests enhance the credibility and reliability of the baseline regression results, confirming the robustness of the study’s conclusions. Therefore, the baseline regression results can be considered both robust and persuasive.

Table 6.

Other robustness test results.

Table 6.

Other robustness test results.

| Controlling Province-Year FE | Excluding Samples Located in Unique Cities | Excluding Low Primary-Share Counties | Replacement of Key Independent Variable | Replacement of Dependent Variable | Replacement of Dependent Variable | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| Variables | FU | FU | FU | FU | FU | FU |

| NMAIP | −0.151 ** | −0.256 ** | −0.263 *** | −0.102 *** | −0.030 ** | −0.026 ** |

| (0.065) | (0.102) | (0.093) | (0.033) | (0.014) | (0.012) | |

| Control variables | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| County FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 8989 | 7724 | 7173 | 8989 | 8907 | 8989 |

Note: Parentheses contain robust standard errors; *** and ** indicate significance at the 1% and 5% levels, respectively.

4.3. Mechanism Tests

The empirical results from the previous section demonstrate that the construction of NMAIP significantly reduces fertilizer use. Theoretical analysis suggests that this reduction is primarily attributable to improvements in production efficiency, specifically through gains in agricultural labor productivity and enhancements in agricultural technology productivity. The following section further examines the underlying mechanisms through which the construction of NMAIP promotes fertilizer reduction.

4.3.1. Improving Agricultural Labor Productivity

This study uses per capita agricultural output to assess NMAIP construction’s impact on agricultural labor productivity. This indicator represents the ratio of agricultural output (including agriculture, forestry, animal husbandry, and fisheries) to the agricultural labor force, enabling an evaluation of labor productivity improvements within the context of NMAIP construction.

The estimation results in Table 7 indicate a significant positive impact of NMAIP construction on agricultural labor productivity. In Column (1) of Table 7, the coefficient is 0.233, statistically significant at the 1% level. This suggests that agricultural labor productivity increased following the construction of NMAIP, underscoring that developing these parks substantially enhanced productivity. Further analysis in Column (2) reveals that the increase in agricultural labor productivity corresponds with a notable reduction in fertilizer use, consistent with our theoretical expectations.

In practice, many NMAIPs integrate “smart agriculture” facilities—such as IoT-based irrigation and fertilization systems, AI-driven monitoring platforms, and digital decision-support tools—that provide real-time information on crop growth, soil moisture, and nutrient status. These technologies enable park enterprises and farmers to optimize labor allocation (e.g., by remotely controlling fertigation systems and coordinating field operations through digital platforms), thus reducing the need for labor-intensive “experience-based” fertilization and lowering the incentive to over-apply chemical fertilizers as a substitute for managerial precision.

The modernization of agricultural practices within NMAIP—including the adoption of advanced technologies such as precision farming and intelligent management systems—has decreased reliance on chemical fertilizers [38,39]. This shift not only reduces chemical fertilizer consumption but also promotes more sustainable and environmentally friendly agricultural practices. Additionally, the results in Column (2) show that the coefficient for the key independent variable—NMAIP construction—diminishes when agricultural labor productivity is included. This change highlights the pivotal role of labor productivity in facilitating fertilizer reduction. Specifically, as agricultural labor productivity improves, farming becomes less dependent on excessive fertilizer to boost yields and more efficient overall, leading to further reductions in fertilizer use. This finding empirically supports Hypothesis 1, which posits that NMAIP construction indirectly promotes fertilizer reduction by enhancing agricultural labor productivity.

4.3.2. Enhancing Agricultural Technology Productivity

To assess enhancements in agricultural technology productivity, this study uses the level of agricultural mechanization as a key indicator, as it directly reflects technological advancements in agriculture. The total power of agricultural machinery per unit of crop sowing area serves as a proxy for agricultural technology productivity [12].

The regression results in Column (3) of Table 7 indicate that NMAIP construction significantly improves agricultural technology productivity. The estimated coefficient for NMAIP construction is 0.024, statistically significant at the 1% level, suggesting that establishing these parks enhances agricultural technology productivity. Increased agricultural mechanization typically contributes to higher production efficiency and more effective adoption of agricultural technologies. This reduces labor demand and improves the precision of production and resource utilization, ultimately lowering fertilizer consumption [50,57].

In many NMAIPs, high-horsepower tractors, precision seeders, variable-rate fertilizer spreaders, and unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) are widely used alongside soil testing and formula fertilization programs. Soil testing allows parks to determine plot-specific nutrient requirements, while variable-rate machinery and UAVs apply fertilizers only where and when needed, avoiding blanket applications across entire fields. As a result, the same yield targets can be achieved with lower total fertilizer input, and the mismatch between actual crop demand and fertilizer supply is substantially reduced.

Further analysis in Column (4) of Table 7 reveals that enhancing agricultural technology productivity significantly reduces fertilizer use. These concrete technologies—soil testing and formula fertilization, precision variable-rate application, and UAV-based topdressing—provide a direct operational channel through which NMAIP construction translates into more accurate fertilizer management and lower overall application intensity. As mechanization and technological efficiency advance, agricultural production becomes less dependent on chemical fertilizers. This shift stems mainly from the use of advanced machinery, which improves land use efficiency, enables more precise fertilizer application, and minimizes fertilizer waste.

A comparison between Column (4) in Table 2 and Column (4) in Table 7 further supports this conclusion. In Table 2, the coefficient for NMAIP is 0.212, while in Table 7, it declines to 0.207. This change indicates that improving agricultural technology productivity helps reduce fertilizer use by optimizing production patterns. The integration of efficient technology and mechanization not only increases yields but also promotes the rational allocation of resources, thereby decreasing excessive fertilizer inputs. This empirical evidence supports Hypothesis 2, which posits that NMAIP construction reduces fertilizer use by enhancing agricultural technology productivity.

Table 7.

Mechanism test results: Agricultural labor and technology productivity.

Table 7.

Mechanism test results: Agricultural labor and technology productivity.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Agricultural Labor Productivity | FU | Agricultural Technology Productivity | FU |

| NMAIP | 0.233 *** | −0.204 *** | 0.024 ** | −0.207 *** |

| (0.078) | (0.079) | (0.012) | (0.079) | |

| Agricultural labor productivity | −0.033 ** | |||

| (0.015) | ||||

| Agricultural technology productivity | −0.137 *** | |||

| (0.048) | ||||

| Control variables | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| County FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 8989 | 8989 | 8907 | 8907 |

Note: Parentheses contain robust standard errors; *** and ** indicate significance at the 1% and 5% levels, respectively.

4.4. Heterogeneity Analysis

4.4.1. Fertilizer Use Levels

Fertilizer use exhibits significant variation across regions and agricultural production types. This study further investigates the heterogeneous effects of NMAIP construction on fertilizer use. To achieve this, we employ unconditional quantile regression (QR), which enables us to analyze the impacts across the fertilizer use distribution at different quantiles. Table 8 presents the results of these regressions, focusing on the low (Q10, Q25), middle (Q50), and high (Q75, Q90) quantiles to capture the differential impacts across regions with varying levels of fertilizer consumption.

Table 8.

Results of heterogeneity analysis in fertilizer use levels.

The regression results in Table 8 show that the key independent variable—NMAIP—exerts a significant negative impact on fertilizer use only at the Q90 quantile, which represents regions with the highest fertilizer use. This suggests that the construction of NMAIP most notably reduces fertilizer use in areas with historically high fertilizer consumption. NMAIP policy can thus play a critical role in curbing excessive fertilizer use in regions characterized by over-application of chemical inputs. By contrast, in regions with low fertilizer use, the impact of NMAIP construction is insignificant, indicating that the potential for reduction is more limited where fertilizer application is already moderate and agricultural practices are relatively efficient.

This outcome can be interpreted from several perspectives. Farmers in high-level fertilizer use regions generally rely more heavily on chemical fertilizers to boost crop yields. This dependency reflects greater room for improving agricultural practices. Over time, these regions have often adopted approaches that prioritize high fertilizer inputs, which, while enhancing short-term yields, have led to long-term challenges such as soil degradation and water pollution. The construction of NMAIP addresses these issues by providing technical support and policy guidance. This includes the promotion of precision fertilization technologies, such as soil testing and smart fertilization systems, which help reduce fertilizer inputs and enhance the precision of fertilizer management. As a result, regions with high-level fertilizer use benefit substantially from the establishment of NMAIP, leading to a marked decline in chemical fertilizer consumption. In contrast, regions with low-level fertilizer use typically already employ more refined and sustainable agricultural practices. Farmers in these areas have adopted efficient and environmentally sound fertilization methods, resulting in lower baseline fertilizer inputs. In such contexts, the marginal effect of NMAIP construction is minimal, as existing practices have already optimized fertilizer usage. Therefore, the establishment of NMAIP does not significantly alter fertilizer use patterns, given that agricultural production in these regions is already aligned with sustainable fertilization principles.

4.4.2. Agricultural Production Characteristics

Resource endowments and regional characteristics strongly shape agricultural development patterns. The agricultural production profiles of different regions, particularly crop types, production methods, and technological levels, directly shape the effect of NMAIP construction on fertilizer use [58].

We divide the entire sample into major grain-producing and non-major grain-producing areas to examine how these agricultural traits influence the reduction in fertilizer use. Regression analyses were performed according to agricultural functional zoning. As shown in columns (1) and (2) of Table 9, in major grain-producing areas, the impact of NMAIP construction on fertilizer use is negative but statistically insignificant. By contrast, in non-major grain-producing areas, NMAIP construction significantly reduces fertilizer use. This outcome indicates that the fertilizer-reducing effect is markedly more pronounced in non-major grain-producing areas.

This difference may be related to several factors. First, major grain-producing areas depend more heavily on chemical fertilizers in high-yield monoculture systems, where fertilizers are regarded as a key instrument for maintaining stable crop output. Although NMAIP construction in these regions may impose certain restrictions on fertilizer application, the reducing effect remains relatively weak or slower to emerge, given the overriding priority of ensuring food security. Moreover, farmers in many of areas have long relied on chemical fertilizers, and the transition toward alternative farming practices tends to be gradual. As a result, the short- to medium-term potential of NMAIP policy to curb fertilizer use may be more constrained in such regions.

In contrast, agricultural production in non-major grain-producing areas is more diversified, often involving vegetables, fruits, cash crops, and other forms of cultivation. The establishment of NMAIP in these regions typically encourages technological innovation, eco-agriculture, and refined management, all of which help raise fertilizer use efficiency and lower over-application. In addition, farmers in these areas generally face less rigid grain-output targets and, according to existing case studies, may exhibit greater openness to adopting sustainable agricultural practices. Hence, the fertilizer reduction effect under NMAIP construction is more substantial in non-major grain-producing areas. In many cases, the agro-ecological conditions and market positioning of these regions also encourage stricter environmental standards and the use of organic fertilizers, precision fertilization, and other approaches to minimize fertilizer inputs. These explanations should, however, be viewed as indicative rather than exhaustive, as our county-level data do not directly observe farm-level nutrient management decisions.

Table 9.

Results of heterogeneity analysis in agricultural production characteristics.

Table 9.

Results of heterogeneity analysis in agricultural production characteristics.

| Major Grain-Producing Area | Non-Major Grain-Producing Area | Rice-Producing Area | Wheat-Producing Area | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| Variables | FU | FU | FU | FU |

| NMAIP | −0.165 | −0.233 ** | −0.153 | −0.252 ** |

| (0.104) | (0.119) | (0.121) | (0.104) | |

| Control variables | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| County FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 5000 | 3989 | 3711 | 5278 |

Note: Parentheses contain robust standard errors; ** indicates significance at the 5% level.

China’s traditional grain production pattern of “southern rice and northern wheat” reflects regional disparities in crop growth conditions shaped by natural, historical, and cultural factors [59]. Against this background, a heterogeneity test based on staple crop type offers deeper insight into the role of NMAIP policy across different farming systems. Columns (3) and (4) of Table 9 further examine this variation, showing that NMAIP construction significantly reduces fertilizer use in wheat-producing areas but does not significantly affect fertilizer use in rice-producing areas.

One plausible interpretation of this pattern relates to the differing growth traits and nutrient demands of wheat and rice. Rice, as an aquatic crop, requires ample water and fertilizer to achieve high yields, particularly key nutrients such as nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium. In many rice-based systems, this translates into higher fertilizer input requirements than in typical wheat-based systems. In contrast, wheat is a dryland crop with lower water requirements and more concentrated nutrient needs. Fertilizer application strategies for wheat are more optimized, leading to lower overall use under comparable technical management. Coupled with the ongoing adoption of precision agriculture technologies, intelligent fertilization systems, and soil health management, farmers in a growing number of wheat-producing regions have begun to embrace more efficient and eco-friendly fertilization practices, which can help reduce their dependence on chemical fertilizers.

In particular, NMAIP initiatives in wheat areas have enhanced fertilizer use efficiency through information-driven management and scientific application techniques, thereby curbing environmental pollution and resource waste caused by over-fertilization. By comparison, the effect of NMAIP construction on fertilizer use in rice-producing regions appears more muted in our estimates, which may reflect rice’s inherently higher nutrient and water demand and the stronger constraints faced when attempting to substantially cut chemical fertilizer use in the short run. These crop-specific explanations are consistent with agronomic insights but should be interpreted cautiously, as the present analysis is conducted at the county level and cannot fully capture within-county variation in crop systems, technology adoption, and management practices.

4.4.3. Park Types

The impact of constructing different types of NMAIP on fertilizer use can vary considerably due to differences in dominant industries, production characteristics, market demands, and technological capacities.

To explore these variations, this study classifies NMAIP into two main categories: bulk commodity-based NMAIP and specialty high-value commodity-based NMAIP. Bulk commodity-based NMAIP primarily focus on producing staple crops, such as grains, oilseeds, and cotton. Their main objective is to ensure national food security and maintain stable agricultural production. These parks serve as a foundation for meeting basic food needs and contribute to more standardized farming practices. In contrast, specialty high-value commodity-based NMAIP concentrate on producing higher-value agricultural products, such as premium fruits, vegetables, specialty livestock, and medicinal herbs. The fertilizer reduction effect of these two types of parks differs significantly, as shown in columns (1) and (2) of Table 10. Specifically, the construction of specialty high-value commodity-based NMAIP has a more pronounced effect on reducing fertilizer use than bulk commodity-based parks. This differential impact can be attributed to several factors. First, specialty high-value commodity-based NMAIP require advanced technical inputs, including precision fertilization, soil nutrient monitoring, and intelligent production management systems. Because these crops are of higher value, farmers exercise greater precision in managing inputs, including fertilizers, to ensure crop quality and market value. The adoption of precision fertilization technologies helps lower chemical fertilizer application, thereby reducing environmental pollution and improving crop production efficiency. In contrast, bulk commodity-based NMAIP tend to operate with less technologically intensive methods, relying more on conventional fertilizer application practices. This reliance limits the scope for fertilizer reduction, as farmers in these parks primarily aim to maintain or boost yields through traditional agricultural approaches. While this strategy supports food security and stable production, it does not substantially diminish dependence on fertilizers. Additionally, market demand shapes fertilizer application patterns. Specialty high-value products typically face stronger market competition and greater price volatility. To preserve quality and market position, farmers in these parks are motivated to adopt more scientific management practices that lower chemical fertilizer use and enhance soil health. In contrast, bulk agricultural products experience relatively stable market demand, with prices more susceptible to policy adjustments and international market shifts. In these contexts, the emphasis on yield maximization can lead to elevated fertilizer application, making fertilizer reduction more difficult.

Table 10.

Results of heterogeneity analysis in Park Types.

Beyond classifying NMAIP by their dominant industries, this study also examines differences in the functional scope of these parks and their implications for fertilizer reduction. NMAIP can be categorized into single-function and integrated-function parks. Single-function NMAIP concentrate on a single agricultural industry, with production, processing, and distribution revolving around one specific agricultural product. In contrast, integrated-function NMAIP combine multiple agricultural industries to foster inter-sectoral synergies, optimizing resource use and leveraging complementary advantages. According to the data in columns (3) and (4) of Table 10, the effect of single-function NMAIP on reducing fertilizer use is significantly greater than that of integrated-function NMAIP. This difference stems mainly from the more centralized and specialized production processes in single-function NMAIP, which facilitate the adoption of tailored agricultural techniques for specific crops. For instance, precision fertilization, rational crop rotation, and targeted soil management can markedly reduce fertilizer application. The centralized production model also simplifies the implementation of fertilizer optimization strategies designed for the cultivated crops. In contrast, integrated-function NMAIP inherently involve a wider variety of crops and agricultural segments, complicating fertilizer management. The diverse nutrient requirements of different crops hinder the application of uniform technological solutions across the entire park, diminishing the feasibility of refined management and weakening the overall fertilizer reduction effect. Furthermore, single-function NMAIP generally prioritize enhancing the output value and quality of a specific agricultural product. This focus allows the introduction of targeted technical interventions, including advanced fertilizer application methods and soil nutrient monitoring systems, which optimize fertilizer use and lessen environmental impact. The specialized nature of these parks enables more efficient resource allocation, leading to more substantial reductions in fertilizer application compared to the more generalized approach of integrated-function parks. The complexity and broader scope of integrated-function NMAIP make it challenging to manage fertilizer use consistently across all production segments, resulting in a weaker aggregate effect on fertilizer reduction.

5. Further Research: Fertilizer Reduction and Food Security

Fertilizers are crucial inputs in agricultural production, playing a vital role in ensuring food security [60]. It is estimated that fertilizers contribute to more than 40% of the increase in China’s food production [61]. Fertilizers are often regarded as the “food” essential for boosting agricultural yields (source). However, excessive fertilizer use leads to environmental pollution and soil degradation and threatens the sustainability of agriculture. Thus, a central challenge in sustainable agricultural development lies in reducing fertilizer application while safeguarding food security [9,58].

This study highlights that the construction of NMAIP has contributed to fertilizer reduction. However, a critical concern is whether this reduction could negatively affect the stability and growth of food production. To address this concern, we examined the effects of NMAIP construction on food production from two perspectives: total grain output and grain yield per unit area. As shown in columns (1) and (2) of Table 11, NMAIP construction promotes an increase in grain output and improves production efficiency. This indicates that, while ensuring food security, NMAIP construction can support the sustainable development of agricultural resources and the environment by optimizing production methods and lowering fertilizer use. The key driver of this outcome is the transformation of agricultural practices promoted by NMAIP construction, particularly the adoption of technologies such as precision fertilization and digital farm management. These parks have facilitated the diffusion and innovation of agricultural science and technology, significantly enhancing soil fertility and nutrient uptake efficiency. As a result, grain output and productivity can rise even with reduced fertilizer inputs. Additionally, through farmer training and the dissemination of modern agricultural practices, NMAIP construction encourages more rational fertilizer application, improving fertilizer efficiency and preventing overuse.

Table 11.

The link between fertilizer reduction and grain output.

To further validate these findings, the study conducted a group regression analysis, dividing the sample into two groups based on median fertilizer use: high- and low-level fertilizer use. As shown in columns (3) to (6) of Table 11, the results indicate that in areas with high-level fertilizer use, NMAIP construction exerts a more substantial impact on increasing total grain output and improving grain production efficiency. NMAIP construction not only reduces fertilizer consumption but also significantly boosts grain yield and production efficiency through technological innovation and optimized fertilizer application methods, particularly in high-level fertilizer use areas. These results suggest that NMAIP construction can create a “win-win” scenario, promoting sustainable agricultural development while ensuring food security by lowering fertilizer use without compromising the food supply.

6. Conclusions and Policy Implications

6.1. Main Findings

This study develops a theoretical framework linking the construction of NMAIP to fertilizer use. Using the rollout of NMAIP as a quasi-natural experiment and applying a multi-period DID model to county-level data from China (2014–2022), we find that NMAIP construction significantly reduces fertilizer application. This result remains robust across a series of tests, including parallel trends, heterogeneous treatment effects, placebo simulations, and sample self-selection checks. Mechanism analysis shows that the reduction in fertilizer use is primarily driven by improved agricultural efficiency, manifested through increased labor and technology productivity.

Heterogeneity analysis reveals substantial regional variation in the fertilizer reduction effects of NMAIP. Notably, parks located in areas with initially high fertilizer application exhibit stronger reduction outcomes. Moreover, local agricultural production characteristics significantly shape NMAIP effectiveness: non-major grain-producing regions, with their diversified production structure and farmers’ greater receptivity to advanced technologies, achieve more pronounced fertilizer cutbacks. By crop type, NMAIP construction leads to greater fertilizer reduction in wheat-producing areas than in rice-producing areas, where ecological constraints and conventional farming practices persist. Further analysis highlights the importance of NMAIP typology in shaping fertilizer use outcomes. Parks specializing in high-value commodities or operating under a single-function model demonstrate superior performance in fertilizer reduction, owing to their focused technological adoption and refined management practices.

Importantly, NMAIP construction not only curbs fertilizer use through innovation and optimized application but also simultaneously raises grain output and production efficiency, thereby safeguarding food supply stability. These findings underscore the role of NMAIP in advancing sustainable agricultural development without compromising food security—achieving a “win-win” outcome for both environmental sustainability and food production.

6.2. Policy Implications