Abstract

Business intelligence and analytics (BI&A) competencies are presented as a strategic factor in managing sustainable competitive advantage. Similarly, dominant logic is presented as a set of beliefs and practices within organizational culture, and strategic diversification is the degree of development for market diversification. This research explored whether BI&A competencies mediate the relationship between dominant logic and strategic diversification in a Chilean SME. This was a non-experimental study with a cross-sectional design. A non-probabilistic sample of 244 employees from the SME was collected. Three instruments were used to measure the variables: the Organizational Dominant Logic Scale, the Organizational Strategic Diversification Scale, and an instrument that measures BI&A competencies. The results identified a proactive dominant logic in the organization, moderate strategic diversification, and moderate consolidation in BI&A competencies. Likewise, in relation to the mediation analysis, it was found that the indirect effects were not statistically significant at the 0.05 level, while the direct effects were, therefore, proactive dominant logic is related to strategic diversification. In conclusion, BI&A competencies could not mediate the relationship between proactive dominant logic and strategic diversification.

1. Introduction

Business Intelligence and Analytics (BI&A) technologies are defined as those that enable organizations to apply analytical techniques and performance dashboards for organizational decision-making. Thus, BI&A in a modern company contributes to its success and competitiveness. However, its implementation in small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) remains generally limited [1].

According to the most recent data published by [2], Micro, Small, and Medium-sized Enterprises (MSMEs) represent around 99.4% of the country’s total businesses and generate approximately 65% of formal employment. This study addresses a crucial challenge for Chilean SMEs—as a main actor in the economic development fabric—consisting of a marked productivity and competitiveness gap derived from the limited adoption and development of the skills and abilities required by the digital transformation process, especially concerning the leadership competencies necessary to integrate these systems into organizational strategy. This gap for creating sustainable value is multi-causal, conditioned by the challenges of digital transformation; among them, the need to strengthen BI&A competencies stands out as a determining pillar for human capital to successfully lead adaptation and sustainable growth in highly agile environments.

Theoretical frameworks referring to dominant logic, dynamic capabilities and resources (RBV) [3,4] could help bridge the gap and provide a theoretical basis in the field of BI&A. In this sense, the digital revolution promises to improve the flexibility of manufacturing systems, mass customization, agility and productivity quality [3,4,5].

This research intends to provide direct and measurable benefits for SMEs, such as: increasing productivity through the optimized use of data for faster and more accurate decisions; reducing risks through better anticipation of market changes; favoring organizational adaptation to change with leaders prepared for disruptive environments; and facilitating expansion into new markets with diversification strategies backed by analytical and innovative capabilities.

In fact, it is important to study SMEs and the specific benefits and barriers they present in the use and exploitation of BI&A. Consequently, this research aims to measure the effects of the dominant logic and strategic diversification mediated by the strategic competencies of BI&A of managerial human capital in SMEs through a mediation analysis [6,7].

In digital environments, leaders must adapt or improve their skills to act, anticipate markets and trends, make decisions, change or adjust plans, and rely on technology in the face of changes in the environment and markets [8,9,10]. Faced with these new demands of contemporary society, managers’ leadership must have the appropriate managerial skills to bring reconfigurable competitive advantages to the organization [4] and be able to adopt attitudes, values, knowledge, and skills to overcome difficulties [11].

The existing literature has not comprehensively explored how leadership management competencies in BI&A, dominant logic, and strategic diversification interact, leaving significant gaps in our understanding of this phenomenon. Previous studies tend to address them in isolation or partially, without considering the mediation of intangible capabilities and resources in contexts of digital transformation and disruptive environments. This research seeks to contribute a novel integrative approach that links these dimensions under the framework of dynamic capabilities, thus offering a theoretical model that expands knowledge about adaptive strategic management and the creation of sustainable reconfigurable value in organizational scenarios that present challenges in the face of high uncertainty and agility [1].

As per above, the central research question guiding this study is: Are BI&A competencies capable of mediating the relationship between dominant logic and strategic diversification in Chilean SMEs, in contexts of digital transformation and disruptive environments?

In this sense, the work not only seeks to fill an academic gap, but also to offer an applicable theoretical–practical framework to reinforce the competitive position of SMEs in the digital economy.

This article is structured into five main sections: the Introduction, which presents the research context, the relevance of the study in the framework of SMEs, and the role of BI&A technologies in competitive advantage; the Literature Review and Hypothesis Development, which analyzes the theoretical foundations related to dominant logic, essential leadership competencies, and strategic diversification, formulating the study’s hypotheses.

Methodology: The instruments used to measure the variables, the population and sample used, and the methods of analysis applied are described.

Results: The findings of the analysis are presented, identifying the level of dominant logic, strategic diversification, and BI&A competencies in the SMEs studied.

Discussion and Conclusions: The results are interpreted in light of the reviewed literature, and the academic and practical implications are presented, as well as the limitations of the study and possible lines of future research.

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

Competencies incorporate knowledge, skills or abilities, experiences, feelings, motivations, desires and values that enable a person to perform successfully [12,13]. The notion of ‘strategic purpose’ also resides in competencies. With a vision for the future, there is a need to identify ‘core competencies’ as ‘those skills that capture what the organization does really well and that are not easy to imitate’. In fact, competencies are the basis for building and implementing a new vision of strategy to achieve the future, based on perceived opportunity, which is why the development of managers’ leadership skills plays a fundamental role. However, it is argued that managerial competencies mediate between dominant logic and strategic diversification [14].

It is important to determine how the essential competencies associated with the leadership of managers in BI&A—in the digital context—mediate between dominant logic and strategic diversification, since the management of disruptive events and the introduction of new ways of handling change and new ideas challenge continuity, in terms of leading a collaborative, analytical, learning and innovative thinking culture, with an effect on decision-making mediated by BI&A [14]. Leadership development in BI&A constitutes a set of skills that will enable managers to formulate various strategies for value creation, encompassing practices, personal resources, competencies, and fundamental knowledge, with adaptive, collaborative, complex, and self-organized attitudes [10,11,15].

2.1. Dominant Logic

Dominant logic is understood as a mindset or conceptualization of the business and management tools for achieving objectives and making decisions, stored as a cognitive map shared by the dominant coalition and expressed as learned problem-solving patterns [14]. Empirical studies indicate that its application has been extended and interpreted in various ways, such as the meanings of entrepreneurs, observable strategic decisions and the similarity of business models, as indicators of dominant logic. This has led to its application being extended and interpreted in various ways, making it difficult to obtain analytical clarity and generalize conclusions [16,17].

2.1.1. Dominant Proactive Logic

Among the types of dominant logic, proactive logic is characterized by the fact that management tends to process as much information as possible about the environment before making decisions; the company discards past actions as a basis for planning the future; constant monitoring of business progress is carried out to avoid deviations between objectives and results; long-term profitability is prioritized over short-term profitability; planning is the main focus of the decision-making process, gathering the opinions of several people before adopting a resolution; and both change and risk acceptance are an integral part of the corporate culture [14,18].

2.1.2. Conservative Dominant Logic

It is considered conservative when senior management processes limited information about the environment before making decisions; bases its decisions on previous experiences and tends to repeat actions that have been successful in the past; adopts corrective measures only after detecting unsatisfactory results; focuses its attention on the present without projecting into the future; seeks primarily short-term profitability; bases its decisions on intuition, generally in a unilateral and inflexible manner; and avoids change as part of its culture, accepting it only when it is essential for the survival of the organization [18].

2.2. Strategic Diversification: From Dominant Logic and the Intermediation of BI&A Leadership Capabilities

Several studies indicate that a company can achieve and sustain competitive advantages based on its intangible resources and capabilities, supported by uncodified data and tacit knowledge, which makes them difficult to imitate and leads to a slow development process [3]. Resource theory focuses on the elements that generate value in mergers and acquisitions, considering that business resources, being heterogeneous and idiosyncratic, form the basis of competitive advantages. These resources are assets under the control of the company—physical, technological, human, and organizational—whose competitiveness will depend on both tangible and intangible factors, with intangibles being the fundamental factor in the advantage, as internal resources and capabilities guide strategy and constitute the main source of benefits [19].

However, it was noted that it is difficult to demonstrate the relationship between industrial structure and profitability, as variations within the same sector are more significant than differences between sectors, due to factors such as increasing global competition, technological transformation of demand, and business diversification processes [20]. This is why the development of resources and capabilities to generate competitive advantages has become an essential objective of corporate strategy. While the traditional approach to advantage is based on cost leadership and unique value differentiation, the resource-based perspective focuses on the resources and capabilities that underpin these advantages [19,21].

Consequently, resources represent a set of factors available and under the control of companies to develop a competitive strategy, which may be tangible or intangible, such as financial, physical, human, technological and reputational resources. On the other hand, capabilities or competencies encompass knowledge and skills, including technologies, that arise from collective learning within the organization and result from the combination of resources and the generation of organizational routines, determined by the exchange of information supported by human capital and dependent on both the incentive system and the integration of people.

In this way, these capabilities enable improved productivity and business efficiency, considering that competition translates into rivalry based on these competencies. Articulating and harmonizing diverse technologies, managing long standardization processes, establishing alliances with suppliers of complementary products, potential rivals and accessing as many distribution channels as possible means that competition is, at the same time, a confrontation between rival groups—often overlapping—and between individual companies. Thus, competition for the future develops both at the inter-company level and between alliances [1,22].

Capabilities, understood as core competencies, emerge from collective learning within the organization, particularly with regard to the coordination of different production techniques and the integration of multiple technological trends [5]. Based on the resource-based view (RBV) of competitive advantage, the theory of dynamic capabilities (MDC) has been developed, which, according to [23], can be classified into three approaches: (1) capability development, (2) innovation, and (3) contingency. These capabilities are a way of combining assets, people and processes to convert inputs into products [19,23,24], guiding business action to continuously integrate, reconfigure, renew and recreate its resources and competencies and, above all, to update and rebuild its essential capabilities in the face of a changing environment in order to maintain and strengthen its competitive advantage. MDCs are part of processes and therefore tend to materialize in an explicit or codifiable structuring and combination of resources, which facilitates their transfer both internally and externally. In turn, the environment has a decisive influence on organizational development and innovation, maintaining close links with technology, culture, the economy and the institutional framework, among others [3,25,26].

2.2.1. Adaptability

According to [23], dynamic adaptability is a variable within the dynamic capabilities model, understood as the organization’s ability to react to changes in the environment [27]. Organizations with greater dynamic adaptability manage to establish a rational and structured approach, allocating resources quickly and efficiently to deal with critical problems and events. In turn, organizations that promote and consolidate this capacity constantly generate and apply new knowledge [23,27,28].

2.2.2. Absorptive Capacity

Absorptive capacity is the organization’s ability to recognize the value of useful knowledge present in its environment, assimilate it, transform it and integrate it into its knowledge base, subsequently applying it through processes and actions linked to innovation, investment in R&D and competitiveness. A company’s ability to learn from another depends on the similarity of knowledge bases, organizational structures and remuneration policies, as well as the dominant logics of organizations [29,30,31,32].

2.2.3. Capacity for Innovation

For innovation to become a dynamic capability, it is essential to encourage the assimilation of changes arising from the environment [33]. According to [34], innovation capacity corresponds to a company’s ability to create new products and services, implement novel production methods and identify new markets. Consequently, expanding innovation capabilities within the organization [35] is a significant source of competitive advantage in scenarios characterized by rapid change [23,36,37]. In effect, this capacity refers to the company’s ability to develop, modify and innovate in products and/or markets through innovative strategies, behaviors and processes [38]. Innovation is therefore an essential element in generating transformations that drive development, wealth creation and the strengthening of competitive advantages, establishing itself as a priority area of research in the context of business operations [39].

2.2.4. Dominant Logic and Strategic Diversification

Dominant logic defines how senior management conceptualizes the business and makes decisions, serving as a collective cognitive framework that guides strategy. The literature distinguishes between proactive approaches, which prioritize information and long-term planning, and conservative approaches, which draw on past experiences and seek immediate profitability. Previous research has shown that this logic influences companies’ ability to diversify their markets and product lines. However, the effect may be mediated by intangible competencies, such as adaptive leadership in BI&A [16,17,19,20].

2.2.5. Leadership in BI&A as a Dynamic Competency

BI&A allows large volumes of data to be analyzed in real time, facilitating quick and informed decisions. The presence of leaders with BI&A competencies enhances the organization’s absorptive capacity, innovation, and adaptability in the face of disruptive environments. This suggests that BI&A competencies may be a mechanism that transforms the dominant logic into more effective diversification strategies [10,11,14,15].

From the resource-based view (RBV) and dynamic capabilities perspective, intangibles such as BI&A competencies can reconfigure resources and routines, generating sustainable competitive advantages. Thus, if the dominant logic guides the strategy, BI&A leadership competencies act as a catalyst to materialize it in strategic diversification.

From what was proposed, the following hypotheses were derived:

H0:

The indirect effect of dominant logic on strategic diversification through BI&A competencies is nil.

Theoretical argument: Based on studies showing that, without technological adaptation competencies, dominant logic may not translate into new market strategies.

H1:

BI&A competencies significantly mediate the relationship between dominant logic and strategic diversification.

According to the dynamic capabilities approach, these competencies enable the absorption of information, innovation, and adaptation, turning strategic vision into diversified actions.

2.3. Leadership in Business Intelligence and Analysis (BI&A)

Business intelligence and analytics (BI&A) is a set of techniques, technologies, systems, practices, methodologies and applications aimed at analyzing essential business data, enabling companies to better understand their activity and the market and make more effective decisions [40]. Given the increase in the amount of data, there is a need for more predictive and real-time information, driving the transition to a new generation of BI&A with an enhanced focus on data intelligence, in which analysis takes on a more forward-looking character [41,42].

Access to massive data in real time and the ability to use data from entire populations, rather than samples, gives managers the ability to detect new patterns, correlations, and relationships that are useful for supporting decision-making [43]. Likewise, having timely information allows managers—professionals who direct and guide the work of others to ensure its execution with less risk—to quickly evaluate various scenarios and consider actions that can be simulated and compared simultaneously, influencing the decision-making process [44,45]. Currently, BI&A places greater emphasis on human capital capabilities [45]. In this context, [46] points out that the key elements for organizations to obtain benefits through BI include leadership, management support, a corporate culture based on the effective management of information resources, defined objectives and strategies, and the appropriate use of BI techniques. This implies that managerial leadership requires diverse competencies and levels aimed at achieving results, integrating physical and mental capabilities [47]. In this sense, competencies are understood as the possession of relevant knowledge acquired through training, practice and experience [18,47,48].

2.4. Purpose, Importance and Role of the Research

This section has reviewed the theoretical frameworks on essential competencies, leadership in BI&A, dominant logic and strategic diversification, providing a conceptual framework where these dimensions converge. Indeed, it has been highlighted that leadership competencies are a key element in value creation, mediating between dominant logic and strategic diversification, transforming perceptions, skills, competencies and management routines into reconfigurable actions that strengthen competitive advantage.

Purpose: The conceptual basis for understanding and measuring the influence of managerial competencies and leadership in BI&A in mediating between dominant logic and strategic diversification is established, highlighting their role in creating sustainable value for products, processes and markets.

Importance: It responds to the need to manage digital and disruptive environments by optimizing internal resources and dynamic capabilities, where leadership and its competencies in BI&A act as strategic catalysts for innovation and diversification.

Role of research: To contribute as a framework to guide future strategic decisions, integrating theory and practice to enhance innovation and business competitiveness through BI&A, and providing an analytical foundation on how leadership competencies can effectively mediate between dominant logic and strategic diversification, maximizing value creation.

3. Materials and Methods

This research was non-experimental with a cross-sectional design [49].

3.1. Participants

The sample consisted of 244 workers from all hierarchical levels of a Chilean company, who were chosen through a non-probabilistic, intentional sampling procedure [50].

Of the 244 workers evaluated, 61 are women (25%) and 183 men (75%), who have an average age of 43.88 years, with a standard deviation of 10.31 years.

Of these workers, the majority have university studies (58.2%), followed by 27% who have a specialization and 14.8% a master’s degree.

3.2. Instruments

Three instruments previously validated in earlier studies were used. These instruments are explained below:

The instrument that measures organizational dominant logic is made up of two dimensions (proactive dominant logic and conservative dominant logic). This instrument has 17 binary-response items (true and false).

The instrument that measures organizational strategic diversification consists of 36 items distributed across three dimensions (adaptive capacity, absorption capacity and innovation capacity), which use a 5-point frequency scale ranging from never to always.

Regarding the instrument that measures BI&A competencies, it consists of 67 items distributed across four dimensions (strategic vision of BI&A, mastery of the enabling environment for BI&A learning, integrating BI&A skills into expert work and developing professional capabilities for business managers in BI&A). Forty-seven items use a 5-point frequency scale ranging from never to always, while the remaining 20 items use a binary response format (0 and 1).

Table 1 shows the three measured variables, their role in the study, and the instruments used to measure them.

Table 1.

Types of variables and instruments used.

3.3. Procedure

A Chilean SME was contacted to carry out the study. The three instruments were arranged in a Google Forms survey with a confidentiality statement and informed consent. The URL for the survey was distributed by the Human Resources department to employees at different levels of the company. The survey was available for 3 weeks. The data was available in a spreadsheet, which was reviewed and cleaned. Categorical variables were also coded. Finally, the data was exported to R Studio version 2025.09.2.

3.4. Data Analysis

For data processing, a set of statistical techniques was used, such as absolute and relative frequencies, arithmetic mean, standard deviation and median.

For the graphical representation of the results from the instruments applied to the workers, box plots were used, which were designed in R Studio using the base function boxplot() of the R language (version 4.5.1).

The box plots were constructed from the total scores obtained in each dimension of the applied instruments (Dominant Logic, Strategic Diversification, and BI&A Competencies). Each graph shows the median (central line), the quartiles (box), and the minimum and maximum values (whiskers), which allows for the visualization of the dispersion and central tendency of these scores.

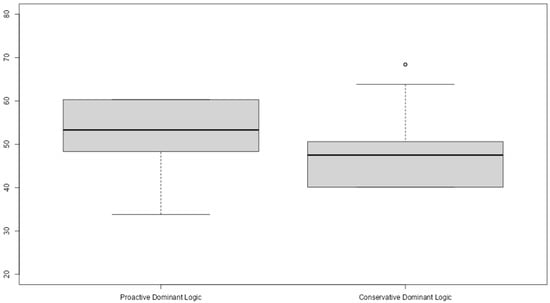

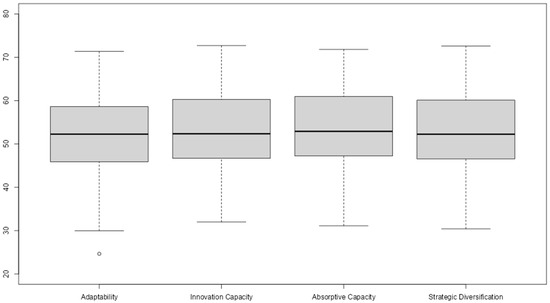

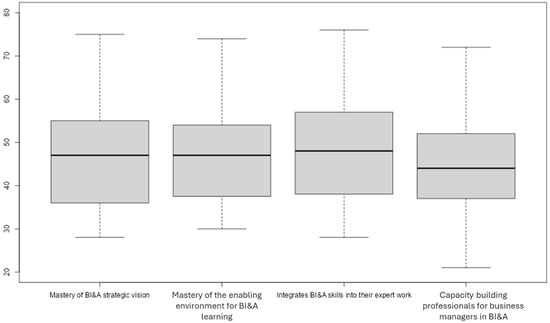

In the Section 4: Figure 1 represents the scores for dominant logic (proactive and conservative); Figure 2 shows the dimensions of strategic diversification (adaptive capacity, absorption capacity, innovation capacity and overall scale); Figure 3 presents the four BI&A competencies (strategic vision of BI&A, mastery of the enabling environment for BI&A learning, integrating BI&A skills into expert work and developing professional capabilities for business managers in BI&A).

Figure 1.

Boxplot for the dimensions of dominant logic.

Figure 2.

Boxplot for dimensions and overall scale of strategic diversification.

Figure 3.

Boxplot for BI&A competencies.

This graphical representation was used as descriptive support to identify behavioral patterns in the sample before conducting the mediation analyses.

Additionally, Mardia’s test was employed to evaluate the multivariate normality of the variables involved in each model. A total of 4 models were evaluated, as there are 4 BI&A competencies, and each one acts as a mediating variable in a distinct model. The models evaluated are the following:

Model 1: Relationship between Proactive Dominant Logic and Strategic Diversification mediated by BI&A Strategic Vision.

Model 2: Relationship between Proactive Dominant Logic and Strategic Diversification mediated by mastery of the enabling environment for BI&A learning.

Model 3: Relationship between Proactive Dominant Logic and Strategic Diversification mediated by integrating BI&A skills into their expert work.

Model 4: Relationship between Proactive Dominant Logic and Strategic Diversification mediated by capacity building professionals for business managers in BI&A.

For the evaluation of multivariate normality, the MVN library in R was used.

These four BI&A competencies were included as mediating variables based on theoretical arguments from the resource-based view [5] and the dynamic capabilities perspective [51,52].

Various studies have suggested that BI&A competencies influence the capacity for adaptation, innovation, and knowledge absorption [53]. These competencies strengthen operational efficiency, strategic decision-making, and the organization’s capacity to adapt to the market. For this reason, BI&A competencies were introduced as mediators to test whether they effectively act as a bridge between the dominant logic and organizational strategic diversification.

For the mediation analysis, a structural equation modeling (SEM) approach was used. For model fitting, the maximum likelihood with robust standard errors (MLR) estimator was employed in models where the assumption of multivariate normality was not met. This estimator is highly robust against the violation of this assumption. For the model where this assumption was met, the maximum likelihood (ML) estimator was used.

Four mediation models were constructed, each with a distinct BI&A competency, which were previously presented and detailed. This disaggregation allowed for a more precise evaluation of which aspect of the competencies could have a mediating effect on the relationship between dominant logic and strategic diversification.

With the mediation analysis, three types of effects were estimated:

Direct effect: This is the relationship between proactive dominant logic and strategic diversification while controlling for the BI&A competencies.

Indirect effect: This is the effect of the proactive dominant logic on strategic diversification through the BI&A competencies.

Total effect: This is the sum of the direct and indirect effects.

The lavaan library in R was used to carry out the mediation analysis. A confidence level of 95% was defined to evaluate the significance of the results.

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Analysis

Figure 1 shows the behavior of the sample in the two types of dominant logic. For the proactive dominant logic, a median of 53.30 was obtained, which means that 50% of the workers reached or equaled 53.30 points in this variable, while for the conservative dominant logic, 47.50 was obtained, which shows that 50% of the sample reached 47.50 points in this variable.

Figure 2 shows the behavior of the sample evaluated in the dimensions of strategic diversification, as well as in the total scale. As can be seen, the sample had a similar behavior in the four variables; in the dimension of adaptive capacity, a median of 52.24 was obtained, in absorption capacity 52.89, in innovation capacity 52.33 and in the total scale 52.23.

Figure 3 shows the behavior of the sample in the 4 BI&A competencies, whose medians were: 47 for strategic vision of BI&A, 47 for mastery of the enabling environment for BI&A learning, 48 for integrating BI&A skills into expert work, and 44 for developing professional capabilities for business managers in BI&A. As can be seen, the medians are very close to each other, with the lowest being that of developing professional capabilities for business managers in BI&A; however, it is in the middle range, like the others.

4.2. Multivariate Normality Assessment

To assess multivariate normality, Mardia’s test was used. Table 1 shows all the mediation models.

In Table 2, it can be observed that p-values associated with Mardia’s test statistic were lower than 0.05 in the first three models, which leads to the rejection of the null hypothesis in favor of the alternative hypothesis. This means that the assumption of multivariate normality is not met.

Table 2.

Mardia’s test.

Regarding the fourth model, a p-value greater than 0.05 was obtained, which leads to the acceptance of the null hypothesis; therefore, the assumption of multivariate normality is met.

4.3. Mediation Analysis

In Table 3, the fit indices for the first model can be observed, which allow for the evaluation of the measurement model’s fit to the data.

Table 3.

The fit indices for the relationship between Proactive Dominant Logic and Strategic Diversification mediated by BI&A Strategic Vision.

Observing the absolute fit indices, the chi-square was not statistically significant, which means the model does not fit the data satisfactorily. Regarding the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), it is less than 0.08, which indicates a good fit of the measurement model to the data. In relation to the incremental fit measures, the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), the Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI), and the Normed Fit Index (NFI) are greater than 0.90, suggesting that the proposed measurement model is better than an independent (null) model, and therefore, the former fits the data satisfactorily. As for the normed chi-square, its value is below 3, which means the measurement model fits the data.

Table 4 presents the fit indices for the second model. As observed, the original model has unfavorable measures. To improve the model, modification indices were requested, which allowed for the correlation of the measurement errors of the observed variables. The new fit indices can be seen in the Modified Model column. In this column, it can be seen that these measures are satisfactory, with the exception of the chi-square. These results indicate that the second model fits the data satisfactorily.

Table 4.

The fit indices for the relationship between Proactive Dominant Logic and Strategic Diversification mediated by mastery of the enabling environment for BI&A learning.

Concerning the fit indices for the third model, Table 5 shows that the original model yielded inappropriate values for the chi-square, normed chi-square, Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), and Normed Fit Index (NFI). To improve these indices, the measurement errors of the observed variables were correlated based on the suggestions from the modification indices. The Modified Model column shows a significant improvement in the fit indices, with the exception of the chi-square. These new measures suggest that the measurement model fits the data satisfactorily.

Table 5.

The fit indices for the relationship between Proactive Dominant Logic and Strategic Diversification mediated by integrating BI&A skills into their expert work.

Regarding the fourth model, it can be seen in Table 6 that the initial fit indices were unsatisfactory. To improve these measures, the measurement errors were correlated based on the indications from the modification indices. The new fit indices obtained reached acceptable values, with the exception of the chi-square and the Normed Fit Index (NFI). This means that the fourth model fits the data satisfactorily.

Table 6.

The fit indices for the relationship between Proactive Dominant Logic and Strategic Diversification mediated by capacity building professionals for business managers in BI&A.

In summary, the four proposed measurement models are valid, as they fit the data satisfactorily.

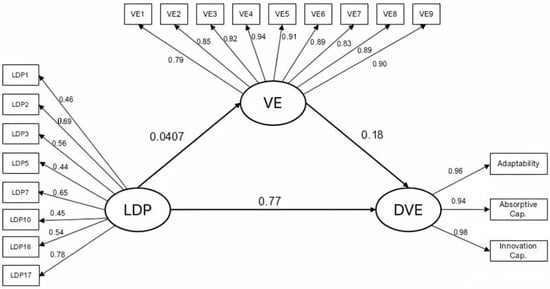

The mediation analysis for the variables proactive dominant logic, strategic vision, and strategic diversification is presented below. Figure 4 shows that the relationship between proactive dominant logic and strategic diversification is high and positive (β = 0.77, p < 0.001), which means that high scores in proactive dominant logic are associated with high scores in strategic diversification. However, the relationship between proactive dominant logic and strategic vision dominance is not statistically significant at the 0.05 level (β = 0.047, p = 0.506), but it has a very weak yet significant relationship with strategic diversification (β = 0.18, p < 0.001). Therefore, high values in strategic vision dominance correspond to high values in strategic diversification. This suggests that workers with a strong and dominant strategic vision tend to foster organizational behaviors oriented towards diversification, thus linking personal strategic orientation with the organization’s strategic outcomes.

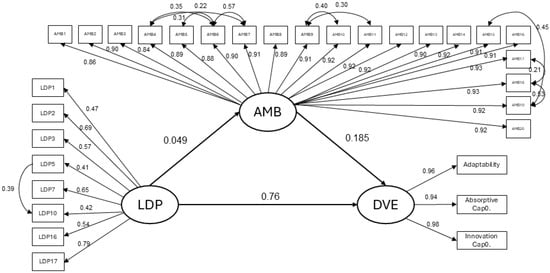

Figure 4.

Path diagram for the relationship between dominant logic, strategic vision and strategic diversification. Note: LDP—Proactive Dominant Logic, VE—Strategic Vision Mastery, and DVE—Strategic Diversification.

Table 7 shows the direct, indirect, and total effects of proactive dominant logic on strategic diversification. When observing the direct effect of proactive dominant logic on strategic diversification by controlling the effect of the strategic vision domain, it is statistically significant at the 0.05 level, which shows that the greater the predominance of proactive logic, the greater the strategic diversification of the organization.

Table 7.

Direct, indirect, and total effects of the dominant logic on strategic diversification mediated by strategic vision.

Regarding the indirect effect of proactive dominant logic on strategic diversification through the strategic vision domain. In the table in question, it is observed that the relationship between proactive dominant logic and strategic diversification is no longer statistically significant.

Regarding the total effect of the independent variable, proactive dominant logic on the dependent variable, strategic diversification. It is worth mentioning that the total effect occurs when the mediating variable, that is, the strategic vision domain, is excluded [54].

It is observed that the p-value obtained is less than 0.05; therefore, the total effect of the proactive dominant logic on strategic diversification is statistically significant.

In the path diagram shown in Figure 5, mastery of the enabling environment for BI&A learning was included as a mediating variable. The diagram shows that the relationship between proactive dominant logic and strategic diversification is high and positive (β = 0.76, p < 0.001). The relationship between proactive dominant logic and mastery of the enabling environment for BI&A learning is not statistically significant (β = 0.049, p = 0.473). However, the relationship between mastery of the enabling environment for BI&A learning and strategic diversification is statistically significant (β = 0.185, p < 0.001), meaning that high values in mastery of the enabling environment for BI&A learning are associated with high values in strategic diversification. This suggests that workers who excel in leveraging the BI&A learning environment contribute to organizational behaviors oriented towards strategy diversification, thus linking personal analytical mastery with organizational strategic expansion.

Figure 5.

Path diagram for the relationship between dominant logic, mastery of the enabling environment for BI&A learning and strategic diversification. Note: LDP—Proactive Dominant Logic, AMB—Mastery of the Enabling Environment for BI&A Learning and DVE—Strategic Diversification.

Regarding the indirect effect of the proactive dominant logic on strategic diversification through the mastery of the enabling environment for BI&A learning, this was not statistically significant according to the p-value contained in Table 8. It should be noted that the direct and total effects remain statistically significant.

Table 8.

Direct, indirect, and total effects of the dominant logic on strategic diversification mediated by mastery of the ena-bling environment for BI&A learning.

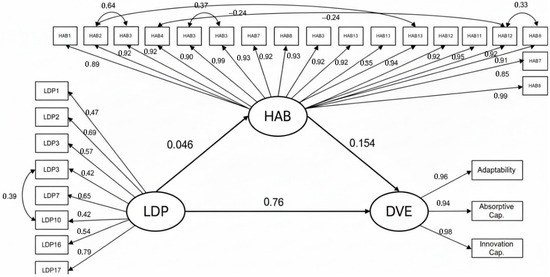

In the path diagram in Figure 6, the integration of BI&A skills into the work of BI&A experts was included as a mediating variable. This path diagram shows that the relationship between proactive dominant logic and strategic diversification is high and positive (β = 0.76, p < 0.001).

Figure 6.

Path diagram for the relationship between dominant logic, integrating BI&A skills and strategic diversification. Note: LDP—Proactive Dominant Logic, HAB—Integrates BI&A Skills into their Work, BI&A Expert and DVE—Strategic Diversification.

The relationship between proactive dominant logic and integrating BI&A skills is not statistically significant (β = 0.046, p = 0.495). However, the relationship between integrating BI&A skills and strategic diversification is of low magnitude but statistically significant (β = 0.154, p = 0.002). Therefore, high scores in integrating BI&A skills are associated with high scores in strategic diversification. This implies that the successful integration of BI&A skills by workers translates into organizational actions focused on strategy diversification, thus linking analytical integration at the individual level with organizational strategic growth.

Regarding the indirect effect of the proactive dominant logic on strategic diversification through the BI&A skills integration variable, this was not statistically significant according to the p-value contained in Table 9. Likewise, the direct and total effects continue to be significant.

Table 9.

Direct, indirect, and total effects of the dominant logic on strategic diversification mediated by integrates BI&A skills into their work, BI&A expert.

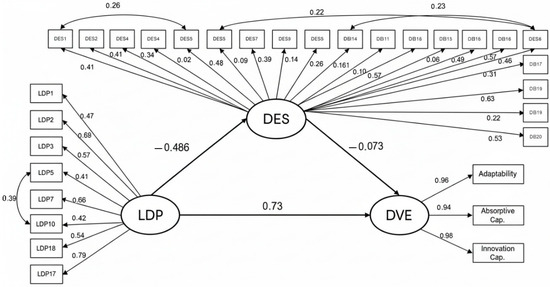

In the path diagram of Figure 7, professional skills development for business managers in BI&A was incorporated as a mediating variable. The path diagram shows that the relationship between proactive dominant logic and strategic diversification is high and positive (β = 0.73, p < 0.001).

Figure 7.

Path diagram for the relationship between dominant logic, professional skills development for business managers in BI&A and strategic diversification. Note: LDP—Proactive Dominant Logic, DES—Professional Skills Development for Business Managers in BI&A and DVE—Strategic Diversification.

The relationship between proactive dominant logic and professional skills development for business managers in BI&A is moderate, negative, and statistically significant (β = −0.486, p < 0.001), which means that high scores in proactive dominant logic are associated with low scores in professional skills development for business managers in BI&A. On the other hand, the relationship between this last variable and strategic diversification is not statistically significant (β = −0.073, p = 0.256).

The indirect effect of the proactive dominant logic on strategic diversification through the professional skills development for business managers in BI&A variable was not statistically significant according to the p-value shown in Table 10. Additionally, the direct and total effects remain significant at the 0.05 level.

Table 10.

Direct, indirect, and total effects of the dominant logic on strategic diversification mediated by professional skills development for business managers in BI&A.

5. Discussion

Based on the scores achieved by the sample evaluated in dominant logic, they revealed that in the organization where they work, a proactive dominant logic predominates to a greater extent; therefore, their leaders tend to promote changes and digital transformation. Also, within the organization, innovative ideas are generated and applied based on technological changes. Based on this, the leaders of the organization have a more entrepreneurial strategic behavior.

Regarding the behavior of the sample on the scale of organizational strategic diversification, it reached scores that placed it at an intermediate level, both in the dimensions and in the total scale. In the adaptive capacity dimension, the organization tends to have a certain organizational flexibility, and additionally, it has the capacity to adjust to changes in the environment in a reasonably effective manner; that is, the organization can recognize and respond to changes in the market and in its industry, but may face certain challenges in the process.

In the absorptive capacity dimension, the organization has the capacity to acquire, assimilate and use new knowledge, technologies or skills effectively, although with certain challenges. It should be noted that there may be some resistance to change and innovation within the organization.

In the innovative capacity dimension, the organization is usually willing to invest in research and development, but may lack the resources, culture or experience necessary to carry out disruptive or revolutionary innovations.

Regarding the scores obtained by the sample on the total scale (strategic diversification), these show that the organization tends to expand its range of products, services, markets or clients, but not in a radical way. This means that the organization maintains its main focus, but also ventures into other areas or activities that are related to its main business.

Regarding the behavior of the sample of workers in the instrument of the 4 BI&A competencies, the largest proportion has the four competencies (mastery of strategic vision of BI&A, mastery of the environment conducive to BI&A learning, integration of BI&A skills into their expert work, and development of Professional Capabilities for business managers in BI&A) moderately consolidated.

This means that in the first dimension, mastery of strategic vision of BI&A, most workers have the tendency to think about the future in a more or less creative way, and generate future scenarios based on external and internal variables of the organization. In the second dimension, mastery of the enabling environment for BI&A learning, the sample tends to regularly promote an environment of trust, respect, and equality in order to create an appropriate work climate that stimulates learning in BI&A technologies. Regarding the dimension Integrating BI&A skills into their expert work, the sample is able to put into practice, autonomously, and more or less frequently, their BI&A skills and knowledge in situations that warrant them. Regarding the fourth dimension, development of professional capabilities for business managers in BI&A, the majority of the sample more or less masters the concepts, terms, and necessary characteristics associated with business intelligence and analytics.

Finally, referring to the mediation analysis, it was found that none of the BI&A competencies managed to mediate the relationship between the proactive dominant logic and strategic diversification. This finding contrasts with that found by [55], whose study reported that the adoption of BI&A significantly improved managerial decision-making and performance in data-oriented organizations. On the other hand [56], highlighted the role of BI&A in fostering organizational agility and innovation, suggesting that its strategic value might be more pronounced in large companies or those with greater digital maturity.

Regarding the dominant logic [57], found that a proactive dominant logic positively influences innovation through external collaboration, in both emerging and developed economies. The findings in the present research partially align with this perspective, by showing that in SMEs, the proactive dominant logic is directly related to strategic diversification, even without mediation by BI&A competencies.

From a methodological point of view, the mediation analysis carried out in this study followed the recommendations of [58], who propose the use of standardized effect sizes and robust estimators to refine theoretical models. The absence of statistically significant indirect effects in this study could reflect contextual limitations in the development of BI&A within SMEs, or it may indicate that managerial cognitive frameworks exert a more direct influence on strategic behavior in resource-constrained environments.

For its part, following [14], the absence of mediation may be mainly due to the fact that the dominant logic is concentrated in the top management of the organization, which generates a very strong direct effect on organizational strategic diversification, thus negating the need for a mediation process through BI&A competencies [52].

Furthermore, since the dominant logic is concentrated in top management, it is the one that directs the diversification of the strategy within the organization and does not take into account the BI&A competencies of the personnel in hierarchies below top management [59,60].

It is important to note that, although top management directs the organization’s strategy, the key BI&A competencies for analysis and decision-making reside with the organization’s leaders and analysts, as they are the ones who manage the information. However, the workers who made up the sample belong to different hierarchical levels, so they are not completely linked to BI&A competencies. This implies that this sample may not have fully captured the influence that BI&A competencies actually have on the relationship between the dominant logic and the organization’s strategy, since the dominant logic ignores levels below top management.

In this context, the dominant logic can operate as a direct strategic driver, and the mediating role of BI&A competencies could depend on organizational size, the degree of digital readiness, or sectoral dynamics.

It is important to highlight that classical literature, such as [14], conceptualized dominant logic as a driver of diversification, but few studies have empirically tested this link in Latin America.

On the other hand, although recent reviews [54] emphasize the potential of BI&A in SMEs, the results of this research suggest that it is not yet consolidated as a strategic mediator.

6. Conclusions

The objective of this research was to evaluate the relationship between dominant logic and organizational strategic diversification mediated by BI&A competencies in a sample of workers from a Chilean SME.

The results showed that the evaluated Chilean SME is marked by a proactive dominant logic, which means that senior management promotes change, innovation, and digital transformation actively. Consequently, there is an entrepreneurial tendency in the organization and a greater willingness to plan long-term and accept risks, which positively impacts organizational strategic diversification.

Regarding strategic diversification, the organization presents intermediate levels in both adaptive capacity and absorption and innovation. This suggests that while there is flexibility and responsiveness to changes in the environment, the organization still faces certain challenges in consolidating innovation processes to be able to expand into new markets.

Referring to BI&A competencies, the majority of the evaluated workers show moderate consolidation in the four competencies: BI&A strategic vision, mastery of the enabling environment for BI&A learning, integration of BI&A skills into their expert work, and Capacity building professionals for business managers in BI&A.

However, it is relevant to clarify that the workers evaluated in these competencies did not reach a sufficient level to mediate the relationship between proactive dominant logic and organizational strategic diversification.

According to the results of the mediation analysis, this technique revealed that the proactive dominant logic directly and significantly influences strategic diversification, while the effect of the proactive dominant logic on strategic diversification through BI&A competencies (indirect effects) was not statistically significant at the 0.05 level. This confirms the null hypothesis (H0) and suggests that, in the context of the SME studied, the strategic logic of senior management is the main driver of diversification, omitting the mediating role of BI&A competencies.

Consequently, the four BI&A competencies failed to act as effective mediators in the relationship between the proactive dominant logic and organizational strategic diversification.

In summary, this research provides empirical evidence that the proactive dominant logic constitutes a key factor for strategic diversification in SMEs, while BI&A competencies have not yet reached a sufficient level of consolidation to mediate this relationship.

7. Practical Implication

This research evidenced that the Chilean SME evaluated is characterized by a proactive dominant logic, with moderate strategic diversification. On the other hand, the organization’s employees have moderately developed BI&A competencies, and consequently, did not reach the necessary level to mediate the relationship between the proactive dominant logic and strategic diversification.

Based on these findings, the following recommendations are derived:

For Senior Management:

Strengthen the proactive dominant logic as part of the organizational culture, promoting long-term strategic planning and the promotion of change as a key factor for organizational growth.

Integrate BI&A competencies into strategic processes, preventing them from developing as isolated resources and ensuring their use directly impacts the organization’s strategic diversification.

For Middle Management and Area Leaders:

Promote continuous training in BI&A, fostering collaborative learning and the application of analytical tools in decision-making.

Create organizational routines that integrate data analysis into daily management, facilitating the anticipation of changes in the environment and the identification of new market opportunities.

For Operational Personnel:

Incentivize participation in learning processes and technological adaptation, promoting a work environment that values innovation and the use of data for continuous improvement.

Guidelines for BI&A Implementation:

Ensure that the adoption of BI&A tools is accompanied by leadership and strategic vision, so that their impact is cross-cutting throughout the organization and is not limited only to technical areas.

Foster an organizational culture oriented toward learning and data-driven decision-making, integrating all hierarchical levels into the digital transformation process.

8. Limitations of the Study and Future Research

As with all research, this one was not free of limitations, one of which is that the majority of the workers who made up the sample were not linked to the business intelligence and analytics area, which could have influenced the correlation between BI&A competencies and the dominant proactive logic, on the one hand, and strategic diversification on the other. BI&A competencies reside in a smaller, more strategic group of workers. Therefore, the mediating effect might exist, but only within the subpopulation of BI&A leaders or area managers, which was not captured by the sampling procedure applied.

Based on the above, it is recommended that future research create a sample of workers who are linked to business intelligence and analytics in order to determine the existence of a relationship between BI&A competencies, the dominant logic and strategic diversification.

Furthermore, research focused on BI&A leaders is recommended to evaluate whether, within these subgroups, BI&A competencies are capable of mediating the relationship between the proactive dominant logic and organizational strategic diversification.

On the other hand, studies are recommended to replicate the present research, but in different sectors and countries, with the objective of identifying variations in the influence of the dominant logic and BI&A competencies on organizational strategic diversification.

Additionally, it could be investigated how the organization’s degree of digital maturity affects the mediating role of BI&A competencies.

And finally, it is recommended to evaluate the effect of BI&A training programs on the ability of SMEs to diversify strategically.

To provide greater robustness to this research, it is recommended to incorporate qualitative methodologies to delve deeper into the perceptions and barriers faced by leaders and employees in the integration of BI&A into business strategy.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study because the research was limited to the administration of anonymous surveys. This type of methodology is classified as minimal risk, as it did not involve the collection of personally identifiable data, physical interventions, or the handling of sensitive or clinical information.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all workers involved in the study. Participation was entirely voluntary, and prior to accessing the digital survey, all workers were presented with an informed consent statement detailing the study’s purpose, voluntary nature, and confidentiality measures. Given that the data collection instrument was strictly anonymous, no personal or identifying information was gathered from the participants, thus ensuring the complete anonymity and data protection of the workers involved.

Data Availability Statement

The data is available upon request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks are extended to the employees of the organization who participated in this research, particularly to the leaders whose support was essential for the development and successful achievement of the study’s objectives.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares that there are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Abdelfattah, F.; Madi, H.; Al-Washahi, M.; AlAraimi, A.; Nagi, S.; Abbas, M. Harnessing Artificial Intelligence, Business Intelligence, and Digital Technologies for achieving supply chain excellence in Oman: Investigating the mediating role of predictive analytics. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2025, 11, 100644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palma, J. Más que Números: Las MiPymes Chilenas y el Desafío de Crecer con Propósito, Tecnología y Redes. Diario Sustentable [Internet]. Santiago (Chile): Diario Sustentable. June 2025. Available online: https://www.diariosustentable.com/2025/06/mas-que-numeros-las-mipymes-chilenas-y-el-desafio-de-crecer-con-proposito-tecnologia-y-redes/ (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- Prahalad, C.K.; Hamel, G. The core competence of the corporation. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1990, 79–90. Available online: https://managementmodellensite.nl/webcontent/uploads/Artikel-over-kerncompetenties.pdf (accessed on 15 August 2025).

- Adeyelure, T.S.; Kalema, B.M.; Bwalya, K.J. A framework for deployment of mobile business intelligence within small and medium enterprises in developing countries. Oper. Res. 2018, 18, 825–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J. Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobedo, M.; Hernández, A.J.; Estebané, V.; Martínez, G. Modelos de Ecuaciones Estructurales: Características, Fases, Construcción, Aplicación y Resultados. Rev. Cienc. Trab. 2016, 18, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huff, A.S. Industry influences on strategy reformulation. Strateg. Manag. J. 1982, 3, 119–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, K.; Bardier, C.; Greer, D.; Clayton, A.; Poblete, M. Unleashing leadership potential in unprecedented times: Lessons learned from an evaluation of a virtual cohort-based adaptive leadership program for public health executives. Public Health Pract. 2024, 8, 100532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liden, R.; Wang, X.; Wang, Y. The evolution of leadership: Past insights, present trends, and future directions. J. Bus. Res. 2025, 186, 115036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rychen, D.S.; Salganik, L.H. Highlights from the OECD Project Definition and Selection Competencies: Theoretical and Conceptual Foundations (DeSeCo). 2003. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED476359.pdf (accessed on 15 August 2025).

- Marzano, R.J. A Theory-Based Meta-Analysis of Research on Instruction. Mid-Continent Regional Educational Lab. 1998. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED427087.pdf (accessed on 15 August 2025).

- Boyatzis, R.E. Beyond competence: The choice to be a leader. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 1993, 3, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wernerfelt, B.A. A Resource-based view of the firm. Strateg. Manag. J. 1984, 5, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prahalad, C.K.; Bettis, R.A. The dominant logic: A new linkage between diversity and performance. Strateg. Manag. J. 1986, 7, 485–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzano, R.J. The New Taxonomy of Educational Objectives; Hawker Brownlow Education: Cheltenham, VIC, Australia, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Engelmann, A.; Kump, B.; Schweiger, C. Clarifying the dominant logic construct by disentangling and reassembling its dimensions. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2020, 22, 323–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, T.; Cooper, R.; Vasilakos, A.; Deng, J.; Zhang, Q. From data to strategy: A public market framework for competitive intelligence. Expert Syst. Appl. 2025, 296, 129061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díez, E.; Calvo-Mora, A.; Navarro-García, A. Lógica dominante, comportamiento estratégico emprendedor y rendimiento de la organización. In Gestión Científica Empresarial: Temas de Investigación Actuales; Barreiro, J., Díez, J., Barreiro, B., Eds.; Netbiblo: Oleiros, Spain, 2003; pp. 33–48. [Google Scholar]

- Tao, J.; Zhang, X.; Wu, X.; Zhou, Q. Rethinking corporate diversification in emerging markets: How digital transformation reshapes strategies in China. Technol. Soc. 2025, 84, 103086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosic, R.; Shanks, G.; Maynard, S. Towards a Business Analytics Capability Maturity Model. 2012. Available online: https://aisel.aisnet.org/acis2012/14 (accessed on 15 August 2025).

- Porter, M. Towards a dynamic theory of strategy. Strateg. Manag. J. 1991, 12, 95–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mertzanis, C. Artificial intelligence and investment management: Structure, strategy, and governance. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2025, 107, 104599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J. Dynamic Capabilities: Routines versus Entrepreneurial Action. J. Manag. Stud. 2012, 49, 1395–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J. Business models and dynamic capabilities. Long Range Plan. 2018, 51, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michailova, S.; Zhan, W. Dynamic capabilities and innovation in MNC subsidiaries. J. World Bus. 2015, 50, 576–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kloviene, L. Improvement of the Performance Measurement System According to Business Environment. Econ. Manag. 2013, 18, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, J.L. A theory of vocational choice. J. Couns. Psychol. 1959, 6, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savickas, M.L. The Theory and Practice of Career Construction. In Career Development and Counseling: Putting Theory and Research to Work; Brown, S.D., Lent, R.W., Eds.; John Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2005; pp. 42–70. [Google Scholar]

- Zahra, S.A.; George, G. Absorptive capacity: A review, reconceptualization, and extension. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2002, 27, 185–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zapata, G.; Hernández, A. Absorptive capacity: A literature review and a model of its determinants. Rev. Cienc. Adm. Econ. 2018, 8, 121–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, P.J.; Lubatkin, M. Relative absorptive capacity and interorganizational learning. Strateg. Manag. J. 1998, 19, 461–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrios-Hernández, K.O.; Olivero, E.; Acosta-Prado, J. Capacidad dinámica de innovación en instituciones de educación superior. Rev. Espac. 2017, 38, 24. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; Ahmed, P. Dynamic Capabilities: A review and Research Agenda. Strateg. Manag. J. 2007, 9, 31–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Froehlich, C.; Bitencourt, C.C.; Bossle, M.B. The use of dynamic capabilities to boost innovation in a Brazilian Chemical Company. Rev. Adm. 2017, 52, 479–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vodovoz, E.; May, M.R. Innovation in the business model from the perspective of dynamic capabilities: Bematech’s case. Rev. Adm. Mackenzie 2017, 18, 71–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kuo, S.Y.; Lin, P.C.; Lu, C.S. The effects of dynamic capabilities, service capabilities, competitive advantage, and organizational performance in container shipping. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2017, 95, 356–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zapata Rotundo, G.J.; Martínez, M. Capacidades Dinámicas de la Organización: Revisión de la Literatura y un Modelo Propuesto. Investig. Adm. 2018, 47, 47–70. [Google Scholar]

- Damanpour, F.; Wischnevsky, D. Research on innovation in organizations: Distinguishing innovation-generating from innovation-adopting organizations. J. Eng. Technol. Manag. 2006, 23, 269–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soldić-Aleksić, J.; Chroneos, B.; Karamata, E. Business analytics: New concepts and trends. Manag. J. Sustain. Bus. Manag. Solut. Emerg. Econ. 2019, 25, 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davenport, T.; Harris, J. Competing on Analytics: Updated, with a New Introduction: The New Science of Winning; Harvard Business Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Rikhardsson, P.; Yigitbasioglu, O. Business intelligence & analytics in management accounting research: Status and future focus. Int. J. Account. Inf. Syst. 2018, 29, 37–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dichter, E. How Hot a Manager Are You? McGraw-Hill: Columbus, OH, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar, P.; Vivekanand, K.; Manoj, T. Integrating machine learning with dynamic multi-objective optimization for real-time decision-making. Inf. Sci. 2025, 690, 121524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seal, K.C.; Leon, L.A.; Przasnyski, Z.H.; Lontok, G. Delivering Business Analytics Competencies and Skills: A Supply Side Assessment. Inf. J. Appl. Anal. 2020, 50, 239–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olszak, C.M. Assessment of business intelligence maturity in the selected organizations. Fed. Conf. Comput. Sci. Inf. Syst. 2013, 1, 951–958. [Google Scholar]

- Attewell, P. What is skill? Work Occup. 1990, 17, 422–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kane, G.C.; Phillips, A.N.; Copulsky, J.; Andrus, G. How digital leadership is (n’t) different. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 2019, 60, 34–39. [Google Scholar]

- Ashkenas, R.; Manville, B. The 6 fundamental skills every leader should practice. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2018, 96, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández, R.; Fernández, C.; Baptista, P. Metodología de la Investigación; McGraw-Hill: Columbus, OH, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández, C.E.; Carpio, N. Introducción a los tipos de muestreo. Alerta Rev. Cient. Inst. Nac. Salud. 2019, 2, 75–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J.; Pisano, G.; Shuen, A. Dynamic capabilities and strategic management. Strateg. Manag. J. 1997, 18, 509–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D. Explicating dynamic capabilities: The nature and microfoundations of (sustainable) enterprise performance. Strateg. Manag. J. 2007, 28, 1319–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsiu, S.V.; Ngobeni, M.; Mathabela, L.; Thango, B. Applications and Competitive Advantages of Data Mining and Business Intelligence in SMEs Performance: A Systematic Review. Businesses 2025, 5, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galindo-Domínguez, H.; Pegalajar, M.; Uriarte, J.D. Efecto mediador y moderador de la resiliencia entre la autoeficacia y el burnout entre el profesorado universitario de ciencias sociales y legales. Rev. Psicodidáctica 2020, 25, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurbean, L.; Militaru, F.; Muntean, M.; Danaiata, D. The impact of business intelligence and analytics adoption on decision making effectiveness and managerial work performance. Sci. Ann. Econ. Bus. 2023, 70, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malawani, L.; Sanguinoa, R.; Tato Jiménez, J.L. A systematic literature review on the impact of business intelligence on organization agility. Adm. Sci. 2025, 15, 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donado, A.; Hernández, L.; Alvear, C.; Castro, I. Dominant logic and external collaboration: Determinants of innovation in an emerging economy and a developed country. J. Technol. Manag. Innov. 2023, 18, 67–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, J.I.; Wang, C.; Ponnapalli, A.R.; Sin, H.-P.; Xu, L.; Lapeira, M.; Song, M. Assessing common-metric effect sizes to refine mediation models. Organ. Res. Methods 2023, 27, 351–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quiñonez, M.; Velez, M.; Guzman, C.; González, J.; Ortiz, J. Desde los pasillos hasta el CEO: La planificación estratégica en todos los niveles. Cienc. Desarro. 2025, 28, 631–637. Available online: http://revistas.uap.edu.pe/ojs/index.php/CYD/index (accessed on 26 October 2025). [CrossRef]

- Awaad, A.; Ababneh, O.; Karasneh, M. The mediating impact of it capabilities on the association between dynamic capabilities and organizational agility: The case of the Jordanian IT sector. Glob. J. Flex. Syst. Manag. 2022, 23, 315–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).