Abstract

Research on xenophobia in inbound tourism is relatively scarce, and the literature focusing on the support of local residents’ xenophobia for inbound tourism is even more limited. Using attribution theory as the guiding framework and incorporating social identity theory, this study systematically explored Chinese residents’ attitudes towards inbound tourism and focused on three types of social identities––cultural, environmental, and place identities, as well as xenophobia of local residents. Residents in Yangzhou, China were surveyed, yielding 401 valid questionnaires for analysis. The results showed that cultural and place identities significantly negatively affected residents’ xenophobia, while environmental identity had no significant effect on residents’ xenophobia. In addition, residents’ xenophobia significantly negatively affected their community participation as well as their endorsement of inbound tourism. Secondly, residents’ cultural and place identities indirectly influence their endorsement of inbound tourism through xenophobia. Finally, social distance played a significant moderating role in certain pathways, specifically in moderating the relationship between cultural identity and xenophobia, and between xenophobia and endorsement of inbound tourism. This study extends the research on the factors affecting inbound tourism, which is significant for promoting the sustainable development of inbound tourism.

1. Introduction

Inbound tourism has expanded rapidly in the 21st century and become a key industry for generating foreign exchange in numerous countries, especially developing countries [1]. In 2024, there were approximately 1.4 billion inbound tourists worldwide, nearly reaching pre-pandemic levels (99%), generating an estimated $1.6 trillion in international tourism revenue, which exceeds pre-pandemic levels [2]. This marks a resurgence of international tourism following the COVID-19 pandemic [2].

However, the recovery worldwide is not balanced. China, an important tourism market, recovered 90% of the pre-pandemic number of inbound tourists in 2024, while international tourism revenue recovered 71% of the pre-pandemic number [3]. Chinese tourism policymakers have implemented a series of policies to revitalize the inbound tourism market, such as relaxing visa policies and improving payments and accommodations [4]. However, among the world’s major economies, China’s inbound tourism market continues to lag in recovery speed. Thus, it is meaningful to identify effective methods to accelerate the recovery of inbound tourism in China.

Recently, scholars have categorized the factors influencing inbound tourism into two types: macro-level factors, such as economic development, geopolitical, and national policy factors [5,6,7,8]; and micro-level factors, including personal perception, tourist behavior, travel decision-making psychology, and residents’ attitudes [9,10,11,12]. Li et al. [6] have analyzed the literature on inbound tourism over the past 30 years and highlight that the current research has shifted focus from inbound tourism flow to the long-term sustainability of tourist destinations. Individual perception factors are garnering increasing attention because the development of inbound tourism is closely linked with resident-tourist relations [13,14], which are crucial for tourist destinations’ sustainability [14]. Previous studies have demonstrated that harmonious resident–tourist interactions enhance community support for tourism, strengthen social cohesion, and contribute to the long-term sustainability of destinations [15]. Conversely, negative emotional responses and conflictual relationships can undermine public acceptance of tourism development, thereby threatening sustainable growth [13].

Kock et al. [16] call for the exploration of negative bias and its consequences on the emotional responses of tourists and residents. Globalization has brought valuable benefits to people worldwide; it has also stimulated the integration of races and countries that were once culturally different, causing some people to feel anxious or disoriented; thus, tourism is particularly prone to xenophobia [17]. Xenophobia, defined as “negative tendencies or even denigration of groups and/or individuals based on perceived differences,” is a negative prejudice [18]. Tourism is highly dependent on external factors and is therefore sensitive to xenophobia, which affects the sustainable development of tourism [17]. The number of studies on xenophobia in the field of tourism is limited, and only a few studies concentrate on tourists’ xenophobic dispositions [17,18,19]. However, it is valuable to analyze local residents’ attitudes towards tourists in the post-pandemic context, as the sustainability of tourism increasingly relies on residents’ perceptions and actions regarding inbound tourism [13]. If tourists’ xenophobia impacts tourism behavior, xenophobia may also play an important role among residents who often encounter foreign tourists [17]. Therefore, gaining insight into the effects of residents’ xenophobia on inbound tourism is of significant importance [17,20].

Attribution theory studies how individuals rationalize the behaviors of others or events, and how these explanations affect attitudes and behaviors [21]. According to attribution theory, when the outcomes of a behavior match or mismatch an individual’s expectations, they lead to positive or negative emotional responses. These emotional reactions influence how individuals explain or attribute the causes of the behavioral outcomes [22]. Positive attributions can enhance an individual’s confidence in performing certain behaviors, whereas negative attributions may reduce their willingness to engage in those behaviors [23]. Xenophobia is a negative perception [17], and its subjectivity leads individuals to ascribe a set of traits to an outgroup based mainly on adverse details, thereby impacting residents’ subjective perceptions [24]. González-Reverté [25] points out that attribution theory is a suitable framework for analyzing how residents’ views are affected by emotional reactions and for understanding the psychosocial factors behind them. Despite the increasing application of attribution theory in tourism research, surprisingly little has been discussed regarding the connection between attribution and negative emotions [26], especially when studying residents’ negative emotions. Therefore, this study used attribution theory as a guiding framework to explore the emotional attitudes and behavioral reactions of residents in negative situations.

Emotional factors stem from the formation of individuals’ cognition, which is based on rational evaluation and perception [27]. Social identity theory investigates the influence of self-concept and associated mental processes on intergroup interactions and is an important link between individuals and groups [28,29]. Social identity affects individuals’ thoughts, emotions, attitudes, and behaviors, making them consistent with the objects or entities with which they identify [30]. Social identity theory helps us gain a more comprehensive understanding of the social behaviors of individuals and groups [31]. Accordingly, the present study uses social identity theory as an antecedent of residents’ cognitive factors to explore how residents’ perceptions of identity affect their behavioral responses. In addition, Genkova et al. [32] highlight that social distance is linked to xenophobia and that increased intergroup contact and communication can alleviate xenophobic sentiments.

In addition to emotional responses, community participation plays a critical role in shaping residents’ support for inbound tourism. Previous studies suggest that residents who actively engage in community affairs are more likely to perceive tourism development positively and support sustainable tourism initiatives [15]. Accordingly, the present study integrates community participation into the proposed framework to more comprehensively understand how social identity and xenophobia influence residents’ support for inbound tourism.

To investigate the intricate relationships among local residents’ social identities, xenophobia, community participation, and their endorsement of inbound tourism, this study seeks to (1) establish a framework based on attribution theory and analyze residents’ emotional responses towards inbound tourism; (2) explore how the antecedents of social identity affect residents’ xenophobia; and (3) identify the guiding factors of residents’ xenophobia on their behaviors. From a theoretical perspective, this study broadens existing theories, provides insights into residents’ xenophobia, and enriches the theoretical model of research on inbound tourism. From a practical perspective, the findings can assist policymakers by identifying the factors that influence residents’ endorsement of inbound tourism.

2. Theoretical Background and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Attribution Theory

Fritz Heider’s research in the 1950s laid the foundation for attribution theory, which suggests that individuals determine internal or external causes by observing behavior in diverse settings [33]. Weiner [34] extends attribution theory by arguing that causal attributions evolve over time, emphasizing how attributions made after an event affect future expectations, emotions, and performance. People’s emotional reactions (negative or positive) to the success or failure of a task are based on their attribution of the causes of their behavior after the event [35]. Heider [21], Kelley [33], and Weiner [34] laid the foundation for attribution theory, seeking to clarify how people infer causality, the types of inferences they draw, and the implications of their behavioral and attitudinal conclusions [36]. The central tenet of attribution theory posits that individuals are continually motivated to interpret the causes of the events they experience [36].

Attribution theory has a wide range of applications in several fields and has become a key framework for understanding responses in the social, consumer, and organizational contexts. Hewett et al. [36] explore the application of attribution theory in human resource management and note that it provides a new perspective for understanding complex phenomena in human resource management and holds significance for practice. Kim et al. [37] show that the attribution process supports moral reasoning in the context of athlete scandals and that attribution directly affects consumers’ reactions, emphasizing the role of attribution theory in shaping moral and behavioral reactions according to perceived causal relationships. Nguyen et al. [38] applied attribution theory to explore how responsibility judgments generated public blame and negative biases in the context of the COVID-19 crisis. Attribution theory provides a framework for how individuals interpret and assign causality to events; it is central to predicting individual emotional, attitudinal, and behavioral responses in different contexts.

Growing interest has emerged in applying attribution theory within tourism studies, particularly in examining how tourists and stakeholders interpret behaviors, perceptions, and emotional reactions. Zhang et al. [26] investigate the association between attribution and emotional reactions in tourist experiences and believe that attribution affects tourists’ negative emotions. Fu et al. [39] integrate attribution theory into an analysis of tourism service failures, indicating that the attribution process explains how tourists interpret and respond to service defects. Alamrawy et al. [40] review the enlightenment of attribution theory in tourism marketing, emphasizing that tourists’ attribution of destinations affects their perceptions and decision-making processes. Hassan and Saleh [41] emphasize the relevance of attribution theory in metaverse tourism and propose that understanding tourists’ attribution processes can enhance their virtual experience. Under the framework of attribution theory, González-Reverté [25] analyze how residents’ views on overtourism are affected by emotional factors. These studies suggest that attribution theory provides a valuable framework for understanding various behavioral and emotional response factors in tourism, and that the theory provides insight into the affective responses and behaviors of local residents towards inbound tourism and foreign tourists.

2.2. Social Identity Theory

Social identity theory explores the ways in which individuals’ self-perceptions, cognitive frameworks, and shared beliefs shape group behavior and intergroup relations. This concept functions as an essential link between individuals and groups, illustrating why people desire group identification and membership [28,29]. An individual’s social identity reflects a component of their self-concept, shaped by both the recognition of group affiliation and the personal values and emotional meaning attributed to that group membership [28]. When individuals perceive themselves as members of a particular group, they develop a sense of belonging and form emotional attachments with the group [42]. Accordingly, individuals tend to internalize the group’s values and behaviors as integral components of their self-identity [43]. Therefore, social identity theory provides a more comprehensive understanding of the social behaviors of individuals and groups [31].

Hogg [44] provides a comprehensive overview of social identity theory, emphasizing its analysis of intergroup conflict and expanding it into various sub-theories, focusing on diverse facets of influence within groups, leadership processes, motivational factors, and group-level behavioral patterns. Social identity theory is used in various fields to study the impact of group membership on attitudes and behaviors. For example, based on social identity theory, Hsieh [45] explores how the cue consistency of social media influencers on multiple platforms affected the social identity and behavioral intention of their followers.

The utilization of social identity theory in tourism research has involved many tourism-related populations, concentrating chiefly on the identity of community residents [46,47,48] and the perspective of tourists [49,50,51]. Social identity theory highlights how residents’ and tourists’ perceptions of group membership influence their attitudes and behaviors towards tourism. For example, from the perspective of tourists, Lee and Jan [51] integrate the social identity theory into the ecotourism behavior model, emphasizing how ecotourism self-identity affects the behavioral intention of nature tourists. Jiang et al. [50] have developed a comprehensive model integrating social identity theory to analyze how knowledge, identity, and perceived risk affect tourism intentions, emphasizing the importance of subjective factors, such as social identity, in understanding tourists’ decision-making processes. By examining Chinese tourists’ perceptions of North Korea, Chen et al. [49] reveal how tourists negotiate their intergroup identity at a tourist destination, highlighting the interactivity and contingency of social identity in the tourism experience.

Nunkoo and Gursoy [46] study residents’ attitudes and supporting behaviors towards local tourism development with respect to their professional, environmental, and gender identities. Sinclair-Maragh and Gursoy [47] use the three dimensions of gender, cultural, and professional identities to explore local residents’ social identities as possible predictors of their perceptions of tourism and their support for tourism development. Wang and Chen [48] examine the influence of place identity, such as self-esteem and self-efficacy, on residents’ perceptions of and support for tourism and find that a strong place identity promotes residents’ positive attitudes towards tourism development. Social identity theory emphasizes the importance of group identity in shaping residents’ ideas, behaviors, and interactions in the community. Therefore, this study explores local residents’ attitudes towards foreign tourists, community participation, and endorsement of inbound tourism from the three dimensions of cultural, environmental, and place identities under social identity theory.

2.2.1. The Effect of Cultural Identity

Cultural identity is an integral component of an individual’s self-concept, marking the psychological connection between an individual and a certain culture [52]. Jameson [53] believes that cultural identity is an intrinsic state that relies on self-recognition and represents a central element of personal identity. The formation of cultural identity arises from individuals’ experiences, perceptions, and interpretations of culture [54]. Cultural identity is a dynamic and continuously changing process that includes both the continuity of the past (“being”) and the new formation process (“becoming”) [55]. Specific cultural identity affects individuals’ perception of various situations because it guides them to accept or reject certain things [56]. For example, tourism development within communities may necessitate the sharing of local culture as a means of tourism promotion. However, the utilization of culture for tourism purposes often conflicts with efforts to preserve that culture [57]. Tourism activities may destroy a local culture [58], because residents may think that their traditional culture is being eroded through tourism activities [59]. Such activities may become less authentic [60], thus affecting cultural identity. Accordingly, residents may think that tourism development negatively impacts local culture [47]. Therefore, factors based on cultural identity may influence local residents to harbor negative emotions or even xenophobia towards tourism. Thus, we propose the following hypothesis:

H1:

Cultural identity affects residents’ xenophobia.

2.2.2. The Effect of Environmental Identity

The self-identity related to the natural environment is called “environmental identity” [61]. Individuals give meaning to themselves when interacting with the natural environment. Simultaneously, the natural environment plays a pivotal role in shaping individual identity [62]. Previous studies have shown that environmental identification explains how people view the development of things [63]; it affects a person’s attitude and behavior towards the development of things and directly influences one’s assessment of developmental processes [64]. Residents’ environmental identity is a key factor affecting their attitudes towards the impact of tourism and their behavioral tendency to support tourism development [46]. Residents of developing countries generally keep close contact with their natural surroundings [65]. Their frequent engagement with water, land, plants, and animals constitute a vital component of their survival [66]. However, tourism is accompanied by a large amount of resource consumption, which places pressure on the environment and may lead to negative attitudes towards tourism [66]. Guo [67] shows that resident perceptions of environmental degradation would trigger resistance and opposition to tourism, becoming a key factor hindering their support. Choi and Murray [68] emphasize that residents’ support for tourism is guided by their views on environmental impact. These studies collectively indicate that environmental identity plays a decisive role in shaping residents’ attitudes toward tourism. Thus, we propose the following hypothesis:

H2:

Environmental identity affects residents’ xenophobia.

2.2.3. The Effect of Place Identity

Place identity states that “the concept of self is based on the location of an individual” [69]. Place identity emphasizes the connection and meaning developed in the interaction between “people and place” [70]. For instance, residents of a specific place tend to feel a sense of belonging to that place [71]. Proshansky [72] believes that place identity is an important concept in tourism that captures an individual’s personal bond with a location and encompasses conceptions, convictions, inclinations, affections, principles, aims, and conduct dispositions. Place identity is regarded as an important pre-factor that affects residents’ attitudes and behaviors [73]. Tourism involvement has both positive and negative influences on the construction of residents’ place identity, and the two are intertwined. Changes in place identity may lead to residents’ negative emotions towards tourism development [74]. Residents’ place identity shapes their attitudes towards tourism and their support for––or opposition to––tourism development, which often reflects their concerns about local integrity [75]. Wang and Chen [48] believe that place identity affects one’s perception of tourism’s impact; when this identity is threatened or undermined, negative emotions develop and support for tourism is reduced. Previous studies show that residents’ attitudes towards tourism are significantly affected by their perceptions of place identity. Negative attitudes towards tourism often stem from perceived threats or conflicts related to place identity. Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

H3:

Place identity affects residents’ xenophobia.

2.3. The Effects of Xenophobia and Its Mediating Role

“Negative tendencies toward, or even denigration of, groups and/or individuals based on perceived differences” is a type of prejudice often referred to as xenophobia [18]. Xenophobia is a long-standing phenomenon [76], an avoidance mechanism is based on fear of foreigners [77]. In the xenophobic world view, foreigners are constructed as “unknown others” who threaten the status quo and should be regarded with suspicion [78]. Xenophobia functions as a mechanism for maintaining distance from out-groups [76], reflecting the explicit or implicit derogation and isolation of those perceived as invaders and hostile “others” [17].

With the progress of science and technology, interactions between groups have become increasingly extensive, and xenophobia has come to reflect the spirit of our current times [17]. The widespread existence of xenophobia in today’s world has attracted the interest of policymakers and researchers [76].

Research on xenophobia in the context of tourism is predominantly centered on tourists and the development of their xenophobic dispositions [17,18,19]. For example, xenophobia is attributed to the perception held by tourists that they are not treated well because of the negative out-group bias [17]. Xenophobia is considered a prerequisite for and factor in shaping travel behavior [19], as well as a social stimulus for tourism-based behaviors [18].

Xenophobia also impacts the perceptions of local residents [77]. Xenophobic subjectivity plays a role in shaping group typologies, because individuals tend to associate a set of largely negative attributes with out-groups [24]. Previous studies have shown that emotions significantly influence how residents respond to tourism development [79]. Matiza [14] suggests that the perceptions of inbound tourists and xenophobia directly and negatively affect residents’ perceptions of local tourism and tourism activities. Nugroho and Numata [80] empirically demonstrate that the level of resident participation in community tourism activities is associated with their degree of support for tourism development. Huitt and Cain [27] indicate that cognitive factors develop through objective evaluation and recognition of an object’s attributes, emotional factors emerge as affective responses grounded in these cognitive processes, and behavioral factors are based on cognitive and emotional factors. Thus, we propose the following hypotheses:

H4:

Xenophobia affects residents’ community participation.

H5:

Xenophobia affects residents’ endorsement of inbound tourism.

H6:

Residents’ community participation positively affects their endorsement of inbound tourism.

H7:

Xenophobia plays a mediating role between local residents’ (a) cultural identity, (b) environmental identity, and (c) place identity and their endorsement of inbound tourism.

2.4. The Moderating Effect of Social Distance

During the early 1920s, Park [81] defined social distance as the measure of understanding and intimacy present in personal and social connections. Recently, social distance has been conceptualized as the level of physical and emotional proximity that individuals permit between themselves and individuals from different social groups [82]. Social distance has been extensively examined within the discipline of sociology [83] and is related to the prejudice, stigma, and stereotypes of individuals or groups [82]. As a structural factor, social distance can be easily understood as the attempt to understand the relationship between groups [84].

Although tourism encourages different national, racial, and ethnic groups to patronize, it is prone to prejudice, stigma, and stereotypes when clear social and cultural differences exist between tourists and locals [85]. Measuring social distance provides us with the opportunity to comprehend these intergroup relationships and measure an individual’s willingness to interact with others [86]. Thyne et al. [86] demonstrate that social distance explains the attitudes and behavioral tendencies of tourists and hosts. Joo et al. [87] propose social distance as a useful structural factor for measuring the connections between residents and tourists in tourism research; this idea is rapidly developing in tourism literature [85]. Accordingly, we propose the following hypothesis:

H8:

Social distance moderates multiple paths in the structural model.

2.5. Conceptual Framework

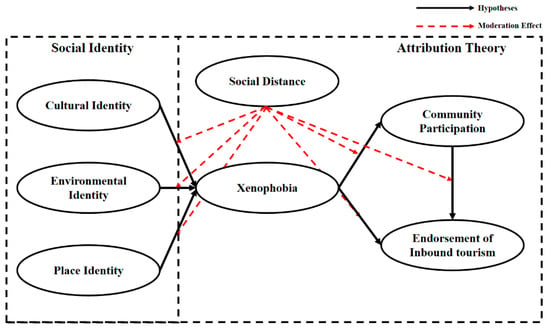

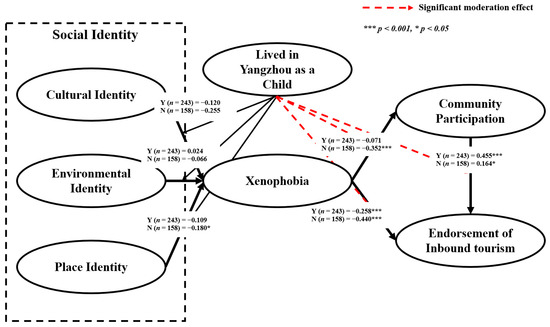

This study proposes the research model illustrated in Figure 1 to examine the influence of local residents’ endorsement of inbound tourism. First, this study investigated the effects of cultural, environmental, and place identities on local residents’ xenophobic attitudes. Second, it examined how these xenophobic tendencies affect local residents’ participation in community tourism activities and their endorsement of inbound tourism. Furthermore, the influence of participating in community tourism activities on one’s endorsement of inbound tourism was examined. Third, the mediating role of xenophobia was analyzed, followed by the moderating role of social distance.

Figure 1.

Proposed Conceptual Framework.

3. Methodology

3.1. Procedure for Data Acquisition

The objective of this study was to examine the interrelationships among local residents’ social identity, xenophobia, community participation, and their endorsement of inbound tourism. To collect representative data, residents of China were selected for the research sample. Considering China’s vast geographical expanse and substantial regional cultural diversity [88], a specific, representative city was chosen. Yangzhou, which is among the first 24 cultural and historical cities in China [89], holds multiple international honors, including “Culture City of East Asia,” “World Canal Capital,” and “World Cuisine Capital” [90]. Thus, employing Yangzhou for illustrative purposes offers considerable representational significance for research on inbound tourism in China.

Data were collected through offline questionnaires using convenience sampling, conducted in several public squares in Yangzhou during August–September 2024. Residents who visit these public squares have a higher probability of interacting with foreign tourists; consequently, selecting residents from these locations through convenience sampling enables a more effective understanding of local residents’ perceptions. Before completing the questionnaire, respondents were screened to confirm that they were residents of Yangzhou. Participation was entirely voluntary. The researchers explained the purpose and procedures of the study to each participant and obtained their verbal informed consent in person.

After excluding incomplete responses, 401 valid questionnaires were retained for the analysis. Table 1 presents the demographic characteristics of the respondents. Among them, women accounted for more than half (59.1%), with the largest age cohort comprising individuals aged 31–40 years (56.9%). Most participants were married (87%), and a significant portion (29.7%) had attained education at the high school or technical secondary level. Additionally, 46.1% of the participants had lived locally for over two decades, and 8.5% reported working within tourism-related sectors. Notably, 89% of the respondents owned property in Yangzhou, and 60.6% reported having lived in Yangzhou during their childhood.

Table 1.

Demographic Profile of Respondents (n = 401).

3.2. Measurement Development

The measurement model consisted of two parts: demographic information and variable information. The information variables included seven components: cultural identity, environmental identity, place identity, xenophobia, community participation, endorsement of inbound tourism, and social distance. We used data adapted from Seo et al. [91], Lai and Hitchcock [92], and Wang et al. [93] to obtain demographic information. Cultural identity was measured through three items adapted from Zhang et al. [94] and Cleveland et al. [95]. Three items adapted from Li et al. [64] were employed to measure environmental identity. Place identity was assessed through four items adapted from Wang et al. [74]. To measure residents’ xenophobic attitudes toward foreign tourists, five measurement items based on Ikeji and Nagai [77] were adopted. Community participation, characterized by whether residents participate in local tourism activities, was evaluated employing five items derived from Qin et al. [96]. Five measurement items derived from Lai and Hitchcock [92] were employed to assess residents’ endorsement of inbound tourism, defined as their recognition and support for its encouragement, promotion, and development. Social distance, operationalized as the willingness of residents to engage in intimate interactions with foreign tourists, was measured using three items adapted from Woosnam et al. [97]. Participants evaluated the statements on a seven-point response scale, and elevated scores represented increased levels of social closeness.

In addition to collecting demographic data, the questionnaire comprised multiple items rated on a 7-point Likert scale, with 1 indicating strong disagreement and 7 indicating strong agreement. The Likert scale is considered the appropriate assessment tool when many items involve considerable uncertainty, as it enables respondents to indicate the relative importance of items without imposing arbitrary rankings [98]. Since the first version of the questionnaire was designed in English, a back-translation process was employed: first translating the items into Chinese and then translating them back into English to guarantee linguistic and conceptual equivalence. Minor revisions were made to the wording to adapt the questionnaire to specific research contexts. Before formal distribution, a pre-test was conducted during which feedback was gathered from management scholars, graduate students, and local community members. Based on their input, further refinements were made to remove semantic ambiguities and overly specialized terminology. The final version of the questionnaire is presented in Appendix B.

3.3. Data Analysis

SPSS (version 29.0) and AMOS (version 26.0) were used for dataset processing. SPSS was used to summarize the demographic characteristics of the sample. Prior to subsequent analyses, the structural validity of the measurement model was examined using exploratory factor analysis (EFA). Following this, AMOS was employed to perform a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to appraise the model’s fit and examine path coefficients. Structural equation modeling (SEM) was used to scrutinize the six hypotheses. Finally, the mediating and moderating effects of the variables were validated.

4. Results

4.1. Assessment of the Measurement Model

EFA employed factor rotation to classify the key construct dimensions. Items with factor loadings equal to or above 0.5 were deemed acceptable [99]. The results indicated a six-factor solution, and Cronbach’s alpha coefficients were computed to examine the measurement stability of the scales. Cronbach’s alpha coefficients fell between 0.920 and 0.964, demonstrating strong item-level consistency. In accordance with George’s [100] guideline, alpha values more than 0.5 were considered satisfactory; all constructs in this study demonstrated satisfactory reliability and validity. Detailed Cronbach’s alpha results are presented in Appendix B.

CFA results show that all standardized factor loadings exceeded the 0.5 threshold, which is commonly accepted in measurement validation [101,102], and therefore all indicators were retained in the model. The assessment of convergent validity involved analyzing both average variance extracted (AVE) and item loadings [101]. All constructs exhibited composite reliability (CR) values exceeding 0.800, indicating strong reliability. As summarized in Table 2, all the constructs satisfied the acceptable evaluation criteria. Discriminant validity was further confirmed, as each construct’s AVE square root was greater than its correlations with other constructs [102]. The results are presented in Table 3. The model’s goodness-of-fit indices were χ2 = 967.949, DF = 260, χ2/DF = 3.723, p < 0.000, CFI = 0.937, IFI = 0.937, GFI = 0.830, NFI = 0.916, RMSEA = 0.083. The analysis demonstrated that the model corresponds adequately to the observed data [101].

Table 2.

Results of the Confirmatory Factor Analysis.

Table 3.

Results of the Discriminant Validity Assessment.

4.2. Assessment of the Structural Model

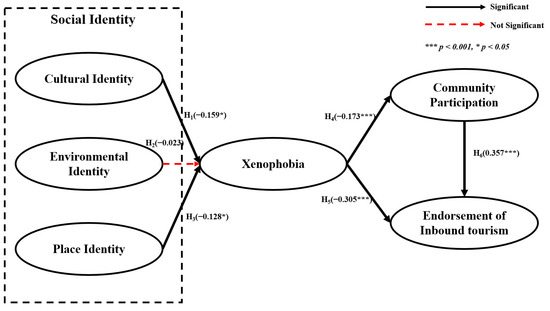

SEM revealed that the model demonstrated acceptable fit to the observed data (χ2 = 1203.751; DF = 266; p < 0.000; NFI = 0.896; GFI = 0.806; RMSEA = 0.094). Table 4 illustrates the results obtained from the path analysis. Analysis of the data revealed that cultural identity (β = −0.159, p < 0.05) and place identity (β = −0.128, p < 0.05) had a significant negative impact on local residents’ xenophobia. Therefore, H1 and H3 are valid. Xenophobia significantly negatively affected community participation of local residents and their endorsement of inbound tourism (β = −0.173, p < 0.001; β = −0.305, p < 0.001). Therefore, H4 and H5 are valid. Community participation of local residents (β = 0.357, p < 0.001) had a significant positive impact on their endorsement of inbound tourism. Therefore, H6 is valid. However, the results showed that environmental identity (β = −0.023, p > 0.05) had no significant effect on residents’ xenophobia. Therefore, H2 is not valid. The results are presented in Figure 2 and Table 4.

Table 4.

Results of the Path and Mediation Analyses.

Figure 2.

Path Analysis Results.

4.3. Assessment of the Mediating Effects

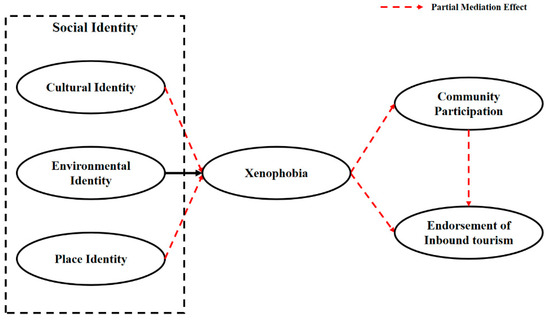

Indirect effects of this study found that cultural identity and place identity indirectly affected local residents’ endorsement of inbound tourism through their xenophobia and their community participation (βCI—XEN—CP—EOIT = 0.004, p < 0.05; βPI—XEN—CP—EOIT = 0.002, p < 0.05). This indicates a chain mediating effect. Additionally, cultural identity and place identity indirectly affected local residents’ endorsement of inbound tourism through their xenophobia (βCI—XEN—EOIT = 0.035, p < 0.05; βPI—XEN—EOIT = 0.022, p < 0.05). Meanwhile, the direct effects of cultural identity and place identity on local residents’ endorsement of inbound tourism remained significant (β = 0.499, p < 0.001; β = 0.245, p < 0.001). This indicates that these four pathways exhibited partial mediating effects, as shown in Table 4 and Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Mediation Analysis Results.

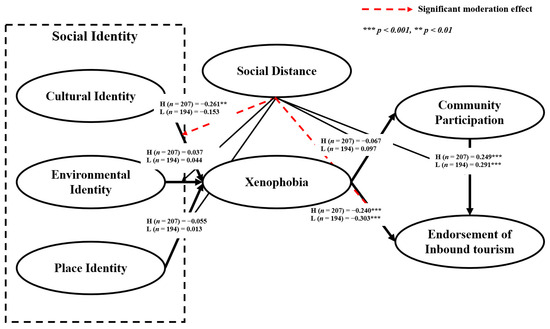

4.4. Assessment of the Moderating Effects

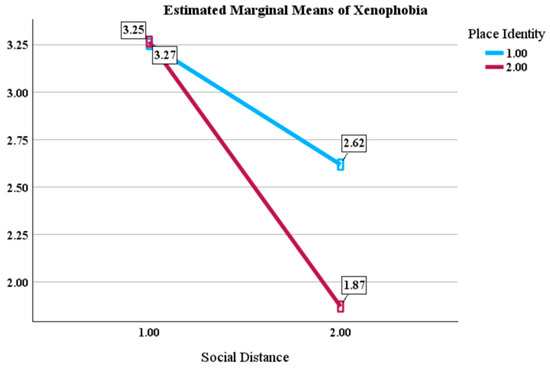

A multigroup analysis was conducted to assess the moderating role of social distance in the research model. The 401 questionnaires were grouped into two categories depending on their scores: those higher than the mean (n = 207) and those lower than the mean (n = 194). The analysis revealed that social distance significantly moderated two relational paths: from cultural identity to xenophobia, and from xenophobia to endorsement of inbound tourism. The results are shown in Table 5 and Figure 4.

Table 5.

Results of the Moderation Analysis for Social Distance.

Figure 4.

Social Distance Moderation Analysis Results.

5. Discussion

The study advances our comprehension of the relationships linking local residents’ social identity, xenophobic attitudes, community participation, and their endorsement of inbound tourism. Prior research examining the effect of xenophobia on inbound tourism concentrates on tourists’ perspectives. However, it is vital to study the xenophobia exhibited by local residents because the sustainable development of inbound tourism depends on the residents’ affective responses and behaviors. Previous studies have suggested that negative attitudes toward tourists may arise from either irrational prejudice or rational responses to perceived threats associated with tourism development [103]. By focusing on the psychological mechanisms of local residents, this study conceptualizes unmotivated xenophobia as a distinct psychological response, thereby enriching theoretical understanding within the tourism field.

Based on empirical data from 401 local residents’ questionnaires in Yangzhou, China, residents’ cultural and place identity significantly negatively affected their xenophobia, whereas residents’ environmental identity had no significant effect on their xenophobia. Second, residents’ xenophobia significantly negatively affected their community participation and their endorsement of inbound tourism, consistent with prior studies showing that xenophobia undermines individuals’ willingness to interact with outsiders and influences tourism-related decision-making [18,19,104]. However, unlike most existing research that focuses on tourists’ perspectives [17,18,19], our findings emphasize residents’ xenophobia as a key factor influencing community participation and support for inbound tourism, thereby extending current understanding in this field. In addition, residents’ community participation significantly promoted their endorsement of inbound tourism. Third, the residents’ xenophobia and community participation partially mediated the association of cultural identity, place identity, and endorsement of inbound tourism. Residents’ xenophobia partially mediated the association of cultural and place identities and endorsement of inbound tourism. Fourth, residents’ social distance functioned as a moderator on two pathways: from cultural identity to xenophobia, and from xenophobia to endorsement of inbound tourism.

The findings indicate that xenophobia significantly increases negative emotional and behavioral reactions toward inbound tourists, which may pose a risk to sustainable development of tourism destinations. Promoting positive resident–tourist interaction and reducing perceived threats may therefore be critical strategies for enhancing social sustainability and supporting the long-term viability in tourism communities.

5.1. Theoretical Implications

Three theoretical contributions can be drawn from this research regarding understanding local residents’ endorsement of inbound tourism. First, prior studies on xenophobia in the field of tourism are limited, and a small number of studies focus on tourists’ perspectives. This study broadens the perspective of xenophobia among local residents and explores the antecedents and consequences of their endorsement of inbound tourism. It complements the role of xenophobia as an independent attribute of tourism destinations and as a personality trait of local residents [104]. In the post-COVID-19 context, it is crucial to understand the attitudes and behaviors of local residents to promote the sustainable development of tourism [13].

Second, prior research on the association between residents and tourists use social exchange theory to explain local residents’ endorsement of tourism; nevertheless, social exchange theory has certain limitations [105]. To overcome this deficiency, this study introduces attribution theory into the research framework and integrates social identity theory as the antecedent of local residents’ cognition, which enriches the theoretical research. This study explores the factors and processes underlying resident endorsement of tourism based on theories [92], specifically interrelations of local residents’ social identity and xenophobic attitudes. The findings show that local residents’ cultural identity and place identity significantly negatively affected their xenophobia. Residents may believe that the arrival of foreign tourists will negatively impact their local culture [47], and negative emotions occur when place identity is threatened or damaged [48]. However, the environmental identity had no significant impact on their xenophobia, which may be explained by the fact that environmental identity reflects individuals’ emotional connections to the natural environment [62]. Xenophobia mostly comes from the threat perception of others [28], which differs from the psychological basis of environmental identity. The internal mechanism between the two is not directly related; thus, environmental identity is not an important determinant of xenophobia.

Third, the present study conceptualizes the key elements of the research framework from various angles and consolidates measurement measures utilized in prior research; clarifies the action path among the variables; systematically constructs the relationship model among social identity, xenophobia, and inbound tourism support; and verifies the mediating role of xenophobia in cultural identity, place identity, and endorsement of inbound tourism. Furthermore, in this study, a moderating variable was added to extend the model and assess the moderating influence of social distance. This model provides support for understanding the complex relationships among social identity, xenophobia, and endorsement of inbound tourism.

5.2. Practical Implications

The findings of this study provide practical guidance for local governments and tourism managers. The empirical findings indicate that xenophobic attitudes among local residents exert a significant influence on both community participation and endorsement for inbound tourism, and the community participation of local residents significantly positively affects their endorsement of inbound tourism, indicating that it is important to strengthen community education and communication to facilitate the sustainable development of local tourism [79]. Tourism managers can guide residents to participate in tourism activities, publicize and highlight the positive benefits of inbound tourism, strengthen residents’ positive cognition of inbound tourism, and reduce dislike directed at foreign tourists.

In addition, the research shows that cultural and place identities have a significant impact on residents’ xenophobia, and social distance has a negative moderating effect on this path. Therefore, tourism managers should prioritize interactive relationships between residents and tourists; increased interaction between groups can reduce xenophobia [32]. Cultural exchange activities, community co-construction projects, and other methods should be implemented to improve residents’ multicultural values, which can effectively deter xenophobia [106].

Finally, the post-pandemic recovery of inbound tourism brought new development opportunities to destination cities. Inbound tourism drives local economic development, increases employment opportunities, raises income levels, and promotes infrastructure construction [9]. Considering the importance of China’s inbound tourism market in global tourism, this study reveals the influence of local residents’ xenophobia on the sustainable development of inbound tourism and proposes reasonable suggestions to accelerate the industry’s recovery.

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

This study has some limitations, and these deficiencies offer implications for future studies. First, the analysis was conducted quantitatively to show the interrelations of residents’ xenophobia, social identity, and endorsement of inbound tourism, but a qualitative perspective to further clarify these relationships was lacking. Qualitative methods can capture the deeper emotional states of residents and reveal subtle nuances that quantitative data may fail to measure [107]. Future research should use mixed methods to deepen the link between xenophobia, social identity, and inbound tourism support.

Second, this study used convenience sampling in public. Although there are sufficient reasons to adopt this approach, future research should consider using the probability sampling method, particularly in tourist cities with large city sizes, to improve our understanding of the resident-tourist relationship and inbound tourism development. Additionally, the research was performed in Yangzhou, China; thus, the conclusions might not apply to various urban areas or depict the national trend. Therefore, future field studies should be conducted in multiple cities to enhance the representativeness and universality of the research.

Third, this study adopted cross-sectional data that only reflect residents’ attitudes towards inbound tourism at a specific point in time. In addition, this study does not make a detailed distinction between foreign tourists from different cultures; local residents may have different attitudes towards foreigners from similar cultures versus different cultures. Future research should distinguish tourists according to their cultural attributes. Ultimately, subsequent studies might examine additional social psychological factors like doomscrolling behavior [108] and depression [109] to evaluate residents’ reactions to inbound tourism and broaden insights into the resident-tourist relationship.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.G. and Z.-Y.Z.; Methodology, P.G. and Z.-Y.Z.; Software, P.G.; Validation, Z.-Y.Z.; Investigation, Z.-Y.Z.; Resources, P.G.; Data curation, P.G.; Writing—original draft, P.G.; Writing—review and editing, Z.-Y.Z.; Supervision, Z.-Y.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study following the IRB guidelines of Kookmin University.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent for participation was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Interaction Tests

To test whether the relationship between place identity and xenophobia was moderated by social distance, this study introduced an interaction term (place identity × social distance) into the model. The results showed that the interaction term significantly influenced xenophobia (F = 24.323, p < 0.001), demonstrating that social distance alters the pathway from place identity to xenophobia. Furthermore, simple slope analysis showed that when place identity was in Group 2 (higher than the average), the negative predictive effect of social distance on xenophobia was stronger (simple slope = −1.38). However, when place identity was in Group 1 (lower than the average), the negative predictive effect was weak (simple slope = −0.65). These results support the existence of interaction effects, as shown in Figure A1.

Figure A1.

Social Distance Interaction Analysis Results.

Although the interaction term (place identity × social distance) was significant in the regression analysis using SPSS, the corresponding moderation effect was not supported by the structural equation modeling (SEM) conducted in AMOS. This inconsistency may result from the methodological differences between traditional regression and SEM. Regression detects moderation through observed variable interactions [110], whereas SEM requires explicit modeling of latent interactions, often through complex procedures, such as product indicator methods or latent moderated structural equations [111], which may reduce statistical power or require larger samples.

Appendix A.2. The Moderating Role of Having Lived in Yangzhou as a Child

Additionally, we checked whether demographic information variables had a moderating effect on each critical path. Individual demographic variables were analyzed using a multigroup analysis approach. The results show that having lived in Yangzhou as a child significantly moderated the impact of xenophobia on community participation, the impact of xenophobia on endorsement of inbound tourism, and the influence of community participation on endorsement of inbound tourism. Therefore, understanding the role of having lived in Yangzhou as a child can direct more effective interventions. The results are presented in Table A1 and Figure A2.

Table A1.

Results of the Moderation Analysis for Lived in Yangzhou as a Child.

Table A1.

Results of the Moderation Analysis for Lived in Yangzhou as a Child.

| Path | Yes (n = 243) | No (n = 158) | χ2 | DF | Δχ2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient | Coefficient | ||||

| CI–XEN | −0.120 | −0.255 | 1769.478 | 538 | 23.379 |

| EI–XEN | 0.024 | −0.066 | |||

| PI–XEN | −0.109 | −0.180 * | |||

| XEN–CP | −0.071 | −0.352 *** | |||

| XEN–EOIT | −0.258 *** | −0.440 *** | |||

| CP–EOIT | 0.455 *** | 0.164 * |

Note: CI = Cultural identity, EI = Environmental identity, PI = Place identity, XEN = Xenophobia, CP = Community participation, EOIT = Endorsement of inbound tourism. Note: *** p < 0.001, * p < 0.05.

Figure A2.

Lived in Yangzhou as a Child Moderation Analysis Results.

Appendix B

| Construct | Items | Cronbach’s Alpha |

| CI | Q1: I feel very proud to identify with Yangzhou culture | 0.930 |

| Q2: I consider it very important to maintain Yangzhou culture | ||

| Q3: It is very important for me to remain close to Yangzhou culture | ||

| EI | Q1: I am very concerned about the natural environment of Yangzhou | 0.920 |

| Q2: I am very protective of the natural environment in Yangzhou | ||

| Q3: I am respectful of Yangzhou natural environment | ||

| PI | Q1: I have a strong identity with Yangzhou | 0.936 |

| Q2: I feel attached to Yangzhou | ||

| Q3: I feel a sense of belonging to Yangzhou | ||

| Q4: Living and working in Yangzhou means a lot about who I am | ||

| XEN | Q1: I try to avoid contact with foreign tourists | 0.956 |

| Q2: I feel anxious when interacting with foreign tourists | ||

| Q3: Interacting with foreign tourists makes me uneasy | ||

| Q4: I don’t think foreign tourists and I can understand each other | ||

| Q5: Foreign tourists should not be trusted | ||

| CP | Q1: I actively participate in tourism related activities in Yangzhou | 0.946 |

| Q2: I understand Yangzhou tourism related planning and policies | ||

| Q3: I have participated in the decision-making related to tourism in Yangzhou | ||

| Q4: I have participated in tourism related training in Yangzhou | ||

| Q5: The government regularly seeks my advice on developing tourism in Yangzhou | ||

| EOIT | Q1: I believe inbound tourism should be actively encouraged in Yangzhou | 0.964 |

| Q2: I support the promotion of inbound tourism in Yangzhou | ||

| Q3: I support the development of new tourism facilities that attract more foreign tourists to Yangzhou | ||

| Q4: I support Yangzhou’s continued development as a popular tourist destination | ||

| Q5: I agree that tourism will continue to play a major role in Yangzhou’s economy | ||

| SD | Q1: I welcome foreign tourists as friends or family | 0.929 |

| Q2: I would like to have a close personal relationship with foreign tourists | ||

| Q3: I would like to invite foreign tourists into my home |

- Note: CI = Cultural identity, EI = Environmental identity, PI = Place identity, XEN = Xenophobia, CP = Community participation, EOIT = Endorsement of inbound tourism, SD = Social distance.

References

- Rasool, H.; Maqbool, S.; Tarique, M. The relationship between tourism and economic growth among BRICS countries: A panel cointegration analysis. Future Bus. J. 2021, 7, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN Tourism. World Tourism Barometer; UN Tourism: Madrid, Spain, 2025; Volume 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Bureau of Statistics of China. National Data. Available online: https://data.stats.gov.cn/easyquery.htm?cn=C01 (accessed on 28 February 2025).

- Xinhuanet. Xinhua headlines: Visa Policy Eases Boost China Travel and Beyond. Available online: https://english.news.cn/20241201/aa6a214a2fc7405089c9b1037110eb77/c.html (accessed on 1 December 2024).

- Khalid, U.; Okafor, L.E.; Shafiullah, M. The effects of economic and financial crises on international tourist flows: A cross-country analysis. J. Travel Res. 2019, 59, 315–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Huo, T.; Shao, Y.; Zhao, Q.; Huo, M. Inbound tourism—A bibliometric review of SSCI articles (1993–2021). Tour. Rev. 2022, 77, 322–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muddasir, M.; Borges, A.P.; Vieira, E.; Vieira, B.M. The impact of macroeconomic factors on the European travel and leisure sector: The context of Russo–Ukrainian war. Tour. Rev. 2025, 80, 513–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portella-Carbó, F.; Pérez-Montiel, J.; Ozcelebi, O. Tourism-led economic growth across the business cycle: Evidence from Europe (1995–2021). Econ. Anal. Policy 2023, 78, 1241–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, P.; Zhu, Z.-Y. Sustainable tourism development in China: An analysis of local residents’ attitudes toward tourists. Tour. Hosp. 2025, 6, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, A.A.-T.; Rahman, M.M.; Gani, M.O. Exploring factors influencing smart tourism destination visiting behaviors in a historic country: A theory of e-consumption behavior. Eur. J. Manag. Bus. Econ. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibragimov, K.; Perles-Ribes, J.F.; Ramon-Rodriguez, A.B. The economic determinants of tourism in Central Asia: A gravity model applied approach. Tour. Econ. 2022, 28, 1749–1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Wang, Z. Analysis of intermediary variables in the market image identity influencing on experience willingness about micro-vacation destinations. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 422, 138492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antwi, C.O.; Ntim, S.Y.; Boadi, E.A.; Asante, E.A.; Brobbey, P.; Ren, J. Sustainable cross-border tourism management: COVID-19 avoidance motive on resident hospitality. J. Sustain. Tour. 2022, 31, 1831–1851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matiza, T. The ‘xenophobic’ resident: Modelling the interplay between phobic cognition, perceived safety and hospitality post the Chinese ‘zero-COVID-19′ policy. Curr. Issues Tour. 2023, 27, 1769–1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Kang, Y.; Park, J.-H.; Kang, S.-E. The Impact of Residents’ Participation on Their Support for Tourism Development at a Community Level Destination. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, F.; Josiassen, A.; Assaf, A.G.; Karpen, I.; Farrelly, F. Tourism ethnocentrism and its effects on tourist and resident behavior. J. Travel Res. 2018, 58, 427–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, F.; Josiassen, A.; Assaf, A.G. The xenophobic tourist. Ann. Tour. Res. 2019, 74, 155–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zenker, S.; Braun, E.; Gyimóthy, S. Too afraid to travel? Development of a pandemic (COVID-19) anxiety travel scale (PATS). Tour. Manag. 2021, 84, 104286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gyimóthy, S.; Braun, E.; Zenker, S. Travel-at-home: Paradoxical effects of a pandemic threat on domestic tourism. Tour. Manag. 2022, 93, 104613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zenker, S.; Kock, F. The coronavirus pandemic—A critical discussion of a tourism research agenda. Tour. Manag. 2020, 81, 104164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heider, F. The Psychology of Interpersonal Relations; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1958. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, H. The influence of attributional style on decision related to symbolic consumption. Manag. World 2007, 5, 162–163. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Zhu, Z. How does mental simulation affect causal attribution? Acta Psychol. Sin. 2003, 35, 237. [Google Scholar]

- Josiassen, A.; Kock, F.; Nørfelt, A. Tourism affinity and its effects on tourist and resident behavior. J. Travel Res. 2020, 61, 299–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Reverté, F. The perception of overtourism in urban destinations: Empirical evidence based on residents’ emotional response. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2021, 19, 451–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Prayag, G.; Song, H. Attribution theory and negative emotions in tourism experiences. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2021, 40, 100904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huitt, W.; Cain, S. An overview of the conative domain. Educ. Psychol. Interact. 2005, 3, 45. [Google Scholar]

- Tajfel, H. Human Groups and Social Categories; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Tajfel, H.; Turner, J.C. An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. In The Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations; Austin, W.G., Worchel, S., Eds.; Brooks-Cole: Monterey, CA, USA, 1979; pp. 33–47. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. Defining identification: A theoretical look at the identification of audiences with media characters. In Advances in Foundational Mass Communication Theories; Routledge: London, UK, 2018; pp. 253–272. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, N.; Hsu, C.H.C.; Li, X. Feeling superior or deprived? Attitudes and underlying mentalities of residents towards Mainland Chinese tourists. Tour. Manag. 2018, 66, 94–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genkova, P.; Schaefer, C.D.; Karch, S. Intergroup contact as a potential path to neutralize the detrimental effect of national identification on xenophobia in Germany. J. Int. Migr. Integr. 2021, 23, 1903–1919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelley, H.H. The processes of causal attribution. Am. Psychol. 1973, 28, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiner, B. A theory of motivation for some classroom experiences. J. Educ. Psychol. 1979, 71, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiner, B. Reflections on the history of attribution theory and research: People, personalities, publications, problems. Soc. Psychol. 2008, 39, 151–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewett, R.; Shantz, A.; Mundy, J.; Alfes, K. Attribution theories in human resource management research: A review and research agenda. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2017, 29, 87–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Lee, J.S.; Jang, W.; Ko, Y.J. Does causal reasoning lead to moral reasoning? Consumers’ responses to scandalized athletes and endorsements. Int. J. Sports Mark. Spons. 2022, 23, 465–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.; Croucher, S.M.; Diers-Lawson, A.; Maydell, E. Who’s to blame for the spread of COVID-19 in New Zealand? Applying attribution theory to understand public stigma. Commun. Res. Pract. 2021, 7, 379–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.; Liu, X.; Hua, C.; Li, Z.; Du, Q. Understanding tour guides’ service failure: Integrating a two-tier triadic business model with attribution theory. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2021, 47, 506–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamrawy, M.A.T.; Hassan, T.H.; Saleh, M.I.; Abdelmoaty, M.A.; Salem, A.E.; Mahmoud, H.M.E.; Abdou, A.H.; Helal, M.Y.; Abdellmonaem, A.H.; El-Sisi, S.A.-W. Tourist attribution toward destination brands: What do we know? What we do not know? Where should we be heading? Sustainability 2023, 15, 4448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, T.; Saleh, M.I. Tourism metaverse from the attribution theory lens: A metaverse behavioral map and future directions. Tour. Rev. 2023, 79, 1088–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashforth, B.E.; Mael, F. Social identity theory and the organization. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 20–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, S.G.; Lane, V.R. A stakeholder approach to organizational identity. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2000, 25, 43–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogg, M.A. Social Identity Theory; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 3–17. [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh, J.-K. The impact of influencers’ multi-SNS use on followers’ behavioral intentions: An integration of cue consistency theory and social identity theory. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 74, 103397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunkoo, R.; Gursoy, D. Residents’ support for tourism: An Identity Perspective. Ann. Tour. Res. 2012, 39, 243–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinclair-Maragh, G.; Gursoy, D. Residents’ identity and tourism development: The Jamaican perspective. Int. J. Tour. Sci. 2017, 17, 107–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Chen, J.S. The influence of place identity on perceived tourism impacts. Ann. Tour. Res. 2015, 52, 16–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Bie, S.; Zhang, C.; Li, Z. Exploring tourists’ social identities in a similar-others destination: The case of Chinese tourists in North Korea. Tour. Rev. 2024, 79, 825–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Qin, J.; Gao, J.; Gossage, M.G. How tourists’ perception affects travel intention: Mechanism pathways and boundary conditions. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 821364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.H.; Jan, F.-H. Ecotourism behavior of nature-based tourists: An integrative framework. J. Travel Res. 2017, 57, 792–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, C.; Chew, P.Y.G. Cultural knowledge, category label, and social connections: Components of cultural identity in the global, multicultural context. Asian J. Soc. Psychol. 2013, 16, 247–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jameson, D.A. Reconceptualizing cultural identity and its role in intercultural business communication. J. Bus. Commun. 2007, 44, 199–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kranz, D.; Goedderz, A. Coming home from a stay abroad: Associations between young people’s reentry problems and their cultural identity formation. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 2020, 74, 115–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, S. Cultural identity and diaspora. In Colonial Discourse and Post-Colonial Theory; Routledge: London, UK, 1994; pp. 392–403. [Google Scholar]

- Parboteeah, K.P.; Cullen, J.B. Social institutions and work centrality: Explorations beyond national culture. Organ. Sci. 2003, 14, 137–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besculides, A.; Lee, M.E.; McCormick, P.J. Residents’ perceptions of the cultural benefits of tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2002, 29, 303–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brida, J.G.; Osti, L.; Barquet, A. Segmenting resident perceptions towards tourism—A cluster analysis with a multinomial logit model of a mountain community. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2010, 12, 591–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andereck, K.L.; Valentine, K.M.; Knopf, R.C.; Vogt, C.A. Residents’ perceptions of community tourism impacts. Ann. Tour. Res. 2005, 32, 1056–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinclair-Maragh, G.; Gursoy, D. Imperialism and tourism: The case of developing island countries. Ann. Tour. Res. 2015, 50, 143–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stets, J.E.; Biga, C.F. Bringing identity theory into environmental sociology. Sociol. Theory 2003, 21, 398–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, S. Environmental identity: A conceptual and an operational definition. In Identity and the Natural Environment: The Psychological Significance of Nature; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2003; pp. 45–65. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, D.L.; Jurowski, C.; Uysal, M. Host community residents’ attitudes: A comparison of environmental viewpoints. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2000, 2, 129–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.-X.; Kim, S.; Lee, Y.-K.; Griffin, M. Sustainable environmental development: The moderating role of environmental identity. Asian J. Soc. Psychol. 2016, 19, 298–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franks, T.R. Managing sustainable development: Definitions, paradigms, and dimensions. Sustain. Dev. 1996, 4, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, C.H. Small island states and territories: Sustainable development issues and strategies—Challenges for changing islands in a changing world. Sustain. Dev. 2006, 14, 75–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.-H. Local revitalization: Support from local residents. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.C.; Murray, I. Resident attitudes toward sustainable community tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 2010, 18, 575–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, B.; Martín, A.M.; Ruiz, C.; Hidalgo, M.D.C. The role of place identity and place attachment in breaking environmental protection laws. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 281–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bott, S.; Cantrill, J.G.; Myers, O.E., Jr. Place and the promise of conservation psychology. Hum. Ecol. Rev. 2003, 10, 100–112. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, S.Y.; Tang, S.Y.; Dai, J.C. Identification of the significance of the concept of place to branches under human geography. Hum. Geogr. 2011, 26, 10–13. [Google Scholar]

- Proshansky, H.M. The city and self-identity. Environ. Behav. 1978, 10, 147–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Lan, H.; Chen, J. Defend and remould—Residents’ place identity construction in traditional villages in the rural tourism context: A case study of Cuandixia village, Beijing. Tour. Crit. Pract. Theory 2024, 5, 21–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wu, B.; Li, J.; Yuan, Q.; Chen, N. Can positive social contact encourage residents’ community citizenship behavior? The role of personal benefit, sympathetic understanding, and place identity. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Chen, S.; Xu, H. Resident attitudes towards dark tourism: A perspective of place-based identity motives. Curr. Issues Tour. 2017, 22, 1601–1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadić-Maglajlić, S.; Lages, C.R.; Sobhy Temerak, M. Dual perspective on the role of xenophobia in service sabotage. Tour. Manag. 2024, 101, 104831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikeji, T.; Nagai, H. Residents’ attitudes towards peer-to-peer accommodations in Japan: Exploring hidden influences from intergroup biases. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2020, 18, 491–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjerm, M. National identities, national pride and xenophobia: A comparison of four Western countries. Acta Sociol. 1998, 41, 335–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunkoo, R.; So, K.K.F. Residents’ support for tourism: Testing Alternative Structural Models. J. Travel Res. 2016, 55, 847–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nugroho, P.; Numata, S. Resident support of community-based tourism development: Evidence from Gunung Ciremai National Park, Indonesia. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 30, 2510–2525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, R.E. The concept of social distance: As applied to the study of racial relations. J. Appl. Sociol. 1924, 8, 334–339. [Google Scholar]

- Yilmaz, S.S.; Tasci, A.D.A. Circumstantial impact of contact on social distance. J. Tour. Cult. Change 2014, 13, 115–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parrillo, V.N.; Donoghue, C. Updating the Bogardus social distance studies: A new national survey. Soc. Sci. J. 2005, 42, 257–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyaupane, G.P.; Timothy, D.J.; Poudel, S. Understanding tourists in religious destinations: A social distance perspective. Tour. Manag. 2015, 48, 343–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleshinloye, K.D.; Fu, X.; Ribeiro, M.A.; Woosnam, K.M.; Tasci, A.D.A. The influence of place attachment on social distance: Examining mediating effects of emotional solidarity and the moderating role of interaction. J. Travel Res. 2019, 59, 828–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thyne, M.; Woosnam, K.M.; Watkins, L.; Ribeiro, M.A. Social distance between residents and tourists explained by residents’ attitudes concerning tourism. J. Travel Res. 2022, 61, 150–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, D.; Tasci, A.D.A.; Woosnam, K.M.; Maruyama, N.U.; Hollas, C.R.; Aleshinloye, K.D. Residents’ attitude towards domestic tourists explained by contact, emotional solidarity and social distance. Tour. Manag. 2018, 64, 245–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y.; Chow, I.H.-S.; Ahlstrom, D. Cultural diversity in China: Dialect, job embeddedness, and turnover. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2010, 28, 221–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- China Daily. Yangzhou shines with historical heritage and cultural charm. Available online: http://subsites.chinadaily.com.cn/yangzhoutravel/2022-02/09/c_706822.htm (accessed on 9 February 2022).

- The Paper. Let the world discover the beauty of Yangzhou! A cultural tourism invitation from the “Three Capitals”. Available online: https://m.thepaper.cn/baijiahao_29448882 (accessed on 25 November 2024).

- Seo, K.; Jordan, E.; Woosnam, K.M.; Lee, C.-K.; Lee, E.-J. Effects of emotional solidarity and tourism-related stress on residents’ quality of life. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2021, 40, 100874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, I.K.W.; Hitchcock, M. Local reactions to mass tourism and community tourism development in Macau. J. Sustain. Tour. 2016, 25, 451–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Hu, W.; Park, K.-S.; Yuan, Q.; Chen, N. Examining residents’ support for night tourism: An application of the social exchange theory and emotional solidarity. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2023, 28, 100780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.-N.; Ruan, W.-Q.; Yang, T.-T. National identity construction in cultural and creative tourism: The double mediators of implicit cultural memory and explicit cultural learning. Sage Open 2021, 11, 21582440211040789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleveland, M.; Rojas-Méndez, J.I.; Laroche, M.; Papadopoulos, N. Identity, culture, dispositions and behavior: A cross-national examination of globalization and culture change. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 1090–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Albrecht, J.N.; Tao, L. The effects of migratory village residents’ social identity on community participation in tourism. J. China Tour. Res. 2024, 20, 811–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woosnam, K.M.; Joo, D.; Ribeiro, M.A.; Johnson Gaither, C.; Sánchez, J.J.; Brooks, R. Rural residents’ social distance with tourists: An affective interpretation. Curr. Issues Tour. 2023, 27, 939–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von der Gracht, H.A. Consensus measurement in Delphi studies. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2012, 79, 1525–1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suhr, D.D. Exploratory or Confirmatory Factor Analysis? SAS Institute: Cary, NC, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- George, D. SPSS for Windows Step by Step: A Simple Study Guide and Reference, 17.0 Update, 10/e; Pearson Education India: New Delhi, India, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Anderson, R.E.; Babin, B.J.; Black, W.C. Multivariate Data Analysis: A Global Perspective, 7th ed.; Pearson Education: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cocola-Gant, A. Tourism gentrification. In Handbook of Gentrification Studies; Lees, L., Phillips, M., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2018; pp. 281–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nghiêm-Phú, B.; Phạm, H.L. Local residents’ attitudes toward reopening inbound tourism amid COVID-19: A study in Vietnam. Sage Open 2022, 12, 21582440221099515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erul, E.; Woosnam, K.M.; McIntosh, W.A. Considering emotional solidarity and the theory of planned behavior in explaining behavioral intentions to support tourism development. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 28, 1158–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uygur, M.R.; Eser, H.B.; Çoksan, S.; Sarıdağ, S. Multiculturalism, social distance, and xenophobia among non-WEIRD individuals toward Syrian refugees: Positive and negative emotions as moderators. Curr. Psychol. 2024, 43, 22859–22871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunkoo, R.; Smith, S.L.J.; Ramkissoon, H. Residents’ attitudes to tourism: A longitudinal study of 140 articles from 1984 to 2010. J. Sustain. Tour. 2013, 21, 5–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taskin, S.; Yildirim Kurtulus, H.; Satici, S.A.; Deniz, M.E. Doomscrolling and mental well-being in social media users: A serial mediation through mindfulness and secondary traumatic stress. J. Community Psychol. 2024, 52, 512–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, N.D.; Truong, N.-A.; Quang Dao, P.; Nguyen, H.H. Can online behaviors be linked to mental health? Active versus passive social network usage on depression via envy and self-esteem. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2025, 162, 108455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klein, A.; Moosbrugger, H. Maximum likelihood estimation of latent interaction effects with the LMS method. Psychometrika 2000, 65, 457–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).