Abstract

As global food demand grows, the limited availability of natural resources exacerbates environmental and food security challenges. Household food waste is a major yet underexplored issue, contributing to inefficiencies, economic losses, and environmental harm. This study applies the Environmental-Economic Footprint (EN-EC) index to assess household food waste in Ireland. By integrating environmental and economic data, this index facilitates a comprehensive dual-perspective evaluation of food waste impacts. Data were collected from 1000 Irish households, analyzing waste patterns across 12 food categories. Environmental impacts were quantified using global warming potential (GWP) and water footprint (WF), while economic costs were based on waste generation and disposal. The EN-EC index synthesizes these parameters to facilitate informed decision-making. On average, Irish households reported approximately 966 g (0.97 kg) of edible food waste per week, equivalent to around 50 kg annually per household. This amount results in substantial associated impacts, including greenhouse gas emissions and water consumption, quantified through literature-based footprint coefficients. Red meat, particularly beef, contributes disproportionately to environmental and economic burdens despite its relatively lower waste volume. A 50% reduction in meat waste could cut CO2 emissions by 2.5 kg, water use by 563.50 L, and costs by €3623.48. These insights equip policymakers with targeted strategies to mitigate food waste, aligning with global sustainability goals.

1. Introduction

Food waste has become a critical issue globally, contributing significantly to environmental degradation and economic losses. In Europe alone, an estimated 88 million tonnes of food waste are generated annually, with associated costs reaching approximately €143 billion [1]. Household food waste accounts for a significant portion of this total, exacerbating both environmental and economic challenges [2]. Recent systematic reviews and bibliometric analyses further highlight that households are the dominant source of food waste in high-income regions and that research on household food waste has expanded rapidly, particularly in Europe [3,4,5]. Reducing food waste at the household level is thus essential to achieving sustainability goals and mitigating the effects of climate change.

The environmental impact of food waste is multifaceted. Not only does wasted food lead to unnecessary resource use, including water, land, and energy, but it also contributes to greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions when organic waste decomposes in landfills. Food waste accounts for about 8–10% of global GHG emissions, driven by the release of methane (a potent GHG) during anaerobic decomposition in landfills [3]. For example, in Ireland, it is estimated that food waste contributes to about 3 million tonnes of CO2-equivalent emissions annually [4]. Additionally, food production requires significant water resources, and wasting food translates to a direct loss of this valuable resource. Meat production, for instance, is particularly resource-intensive; beef production requires as much as 15,400 L of water per kilogram [5]. This highlights the environmental urgency of addressing food waste, particularly in resource-intensive food categories such as meat and dairy.

Economically, food waste represents not only the loss of valuable food resources, but also additional costs related to waste collection, disposal, and management [6]. In Ireland, households discard an estimated 250,000 tonnes of food annually, costing the average household between €400 and €1000 per year [7]. This financial burden, often overlooked by households, includes both the direct cost of wasted food and the indirect costs associated with waste management services [8]. Furthermore, local authorities in Dublin are faced with increasing costs for managing waste, driven in part by the growing volume of household food waste, which places strain on waste management infrastructure and services [4]. In parallel, recent science-mapping and bibliometric work has shown that household food waste research is increasingly multi-disciplinary and emphasizes the need for robust, comparable methodologies and stronger links to policy and intervention design [9]. More recently, a multi-level framework has been proposed that organizes the determinants of household food waste across micro- (individual), meso- (household), and macro- (wider food-system and policy) levels, underscoring that food waste emerges from the interaction of factors operating at and between these levels [6].

In Ireland, household food waste is a growing concern, driven by increasing consumption patterns, food purchasing behaviors, and inefficient waste management practices [4]. Research has shown that Irish households typically waste perishable items such as fruits, vegetables, dairy products, and bread, which are prone to spoilage and over-purchasing [7]. Bread, for instance, is one of the most wasted food items, with approximately 35% of Irish households discarding bread on a weekly basis [7]. Similarly, a significant number of fresh fruits and vegetables are wasted due to improper storage or overestimation of needs.

This study aims to assess the environmental and economic impacts of household food waste in Ireland through the development of a novel Environmental-Economic Footprint (EN-EC) index. This index integrates key environmental metrics, such as water footprint (WF) and GHG emissions, with economic factors, including food waste generation and disposal costs. By focusing on 12 food categories commonly wasted in households, gathered from a cross-country survey study, this study provides a comprehensive assessment of the dual impact of food waste on both the environment and the economy. Moreover, the analysis of food waste patterns in Ireland offers crucial insights into how Irish households contribute to the larger issue of food waste and provides guidance for targeted interventions aimed at reducing waste and improving sustainability efforts. Building on recent syntheses of household food waste drivers and research gaps [3,4,5,9,10], this work links behavioral patterns in Irish households to quantified environmental-economic consequences, offering a decision-support metric for targeted interventions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Gathering

The analysis is based on data collected from 1000 completed online surveys, covering all 26 counties of the Republic of Ireland. The cross-sectional survey was conducted over a fifteen-month period, beginning in late April 2023 and concluding in early August 2024.

The questionnaire was designed based on a synthesis of validated food waste survey instruments, adapted for the Irish context. Specifically:

- From [8], we adopted structuring for food categories and household food waste estimation techniques.

- From [9], we adapted motivational and attitudinal constructs (e.g., perceived behavioral control, food management practices), simplifying language for broader accessibility.

The survey included both closed- and open-ended questions across the following modules: Food waste quantity and category (grams/day per food type), Reasons for discarding food (e.g., spoilage, over-purchasing, expiry confusion), Food waste disposal methods (e.g., composting, landfill, animal feeding), Household demographic and socioeconomic profile, including household size, age distribution, education level, income bracket, dietary preferences, and geographic location (urban/rural, county). Participation was open to adults (≥18 years) residing in any of the 26 counties of the ROI. Eligibility required that the participants were involved in the activities to at least purchase, handle or manage food and food waste in the household.

The survey was disseminated nationally using a multi-channel strategy, including institutional mailing lists, public and private social media platforms (e.g., Twitter/X, Facebook, LinkedIn, Instagram), and a national radio campaign. Participation was voluntary, anonymous, and no identifiable information was collected.

Self-reported surveys are subject to known limitations such as recall and social desirability bias, potentially affecting the accuracy of reported food waste volumes. However, this method remains widely accepted in food waste research due to its scalability and cost-effectiveness [8,9]. Anonymity and practical estimation guidance were used to mitigate potential bias.

A full version of the questionnaire, the list of variables, and additional methodological details are provided in Supplementary Materials (Section S1) to support transparency, replication, and interpretation of our approach.

2.2. Data Cleaning and Estimation of Household Food Waste

The initial dataset comprised 1300 responses. Cases with missing values on food-waste quantity and sociodemographic variables were removed via listwise deletion. Additional cleaning involved checks for internal inconsistencies and removal of duplicate entries. Outliers were screened using z-scores; values beyond ±3 SD were retained when plausible. The final analytical sample consisted of 1000 valid cases (a reduction of ~23%). The sample’s sociodemographic characteristics are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Conversion coefficients from wasted food to agricultural products.

The mass of food waste was converted to its raw food equivalent and then further to agricultural products following the methods proposed by [10]. Conversion coefficients were extracted from the relevant literature [11]. The daily average weight of agricultural food waste in Irish households and its standard error was computed using Equation (1).

where is the daily average of wasted food in the household (kg/day/household), is the daily average wasted amount of food item i per household (kg), n is the total number of identified wasted food items (Table 1), is the conversion coefficient of wasted food item I (kg) to raw food item due to change in water content and cooking loss; is the conversion coefficient of raw food equivalent item i (kg) to the agricultural products due to value chain losses (Table 1).

The estimation of raw food waste equivalents relied on conversion factors derived from prior studies [10,11], which account for differences in water content, processing, and agricultural product equivalents. While these coefficients provide standardized comparability, their applicability to Ireland’s food supply chain requires more attention. Food production, processing techniques, and dietary habits differ across regions, potentially affecting conversion accuracy. For instance, the proportion of imported vs. locally produced meat, bread, and dairy products in Ireland may not align perfectly with existing coefficient assumptions. Future studies should explore region-specific adjustments to improve accuracy by integrating national food consumption and loss data from agencies such as the Irish Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the Central Statistics Office (CSO).

2.3. Carbon and Water Footprint of Household Food Waste

The environmental impacts of wasted food items were assessed using the carbon footprint and water footprint indices, as indicated in Equations (2) and (3). All footprint coefficients were applied to the Irish household dataset described in Section 2.1; results are reported per kilogram of discarded product unless otherwise stated.

The variables CFFW and WFFW represent the average carbon footprint (kg CO2-eq) and water loss (m3) from household food waste. The global warming potential GWPi (kg CO2-eq/kg) was taken from [12], while the water footprint WFi (m3/kg) was derived from [5]. These metrics assess the environmental impact of food waste, using life cycle analysis to quantify GHG emissions from food production to retail, and country-specific water usage for crops and livestock. Environmental impact coefficients (GWPi and WFi) were sourced from [12], a widely accepted meta-analysis of carbon footprints of food products across European contexts, and from [5], which provides globally comparable water footprint values. For composite items like soup and bread, values were derived using disaggregated ingredient-level approximations based on typical Irish recipes and adjusted using weighted footprint values from these same sources. This ensures a consistent, regionally appropriate basis for all environmental impact calculations. The category-level water footprint results (e.g., beef: 52%, pork: 9%, poultry: 5%, and rice: 4%) were obtained by multiplying the household-reported food waste quantities for each category with food-specific water footprint coefficients (WFi, L/kg). As the survey categorized meats into broader groups (e.g., red and white meat), we used national dietary consumption statistics from the national adult nutrition survey 2011 [13] to proportionally allocate quantities to beef, pork, and poultry. These assumptions and disaggregations are explained in the Supplementary Materials.

2.4. Economic Impact of Household Food Waste

The economic cost of food waste in Irish households was determined by considering the market prices of agricultural products, and the expenses for waste management. Retail prices were obtained from the Irish Agriculture Fact Sheet. Due to the absence of reliable, context-specific data, we excluded behavioral or inconvenient costs from our economic calculations. The formula for calculating the economic impact of food waste was:

where

- -

- is the average economic cost of wasted food in Dollars,

- -

- is the retail price of each wasted food item (€/kg),

- -

- is the average cost of food waste disposal per household (€) [4],

2.5. Combined Environmental and Economic Impact Analysis

To evaluate the combined environmental and economic effects of food waste, this study used the EN-EC Footprint Index proposed by [14]. This metric integrates environmental aspects like the water footprint (m3) and GHG emissions (kg CO2-eq) with economic factors such as household food waste (kg of agricultural products) and associated costs (€). Data were normalized on a 0 to 1 scale, where 0 denotes the minimal impact and 1 signifies the maximum. Due to their large values, economic data were further normalized using logarithms (Table S2). The EN-EC index for each food type was calculated using the following formula.

where

- -

- EN-EC Footprint Index represents the combined environmental and economic impact of specific food waste types,

- -

- and are the water footprint (m3) and GHG emissions (kg CO2-eq),

- -

- is the converted agricultural product weight (kg),

- -

- is the waste cost (€) for the food type.

2.6. Carbon Footprint of Household Food Waste

The carbon footprint of household food waste was assessed using data for 12 types of food waste identified in the surveyed Irish households. As mentioned earlier, survey data was obtained from a total of 1000 completed responses, collected across all 26 counties in Ireland. This online cross-sectional survey took place over a fifteen-month span, beginning in late April 2023 and ending in early August 2024. GWP for each food item were taken from [4], ensuring consistency with their list of 168 food products. This approach allowed for a standardized estimate of the embedded GHG emissions associated with the 12 food products analyzed in this study.

3. Results

Overview of Household Demographic Characteristics

The demographic profile of the sample (as shown in Table 2) reflects a heterogeneous mix of Irish households, with the majority (71%) aged between 25 and 54 years, corresponding to the most active food-purchasing and family management stages. Women constituted a greater share of respondents (56.8%), a pattern that aligns with the gendered responsibility for domestic food provisioning reported in many European households. Educational attainment was relatively high, with 33.2% holding postgraduate qualifications, consistent with the online survey mode typically attracts more educated respondents. The sample also showed strong urban representation (58.9%). Collectively, these characteristics suggest that the sample constitutes a broad but slightly more affluent and educated segment of Irish households.

Table 2.

Demographic Distribution of Irish Households in the Study Sample.

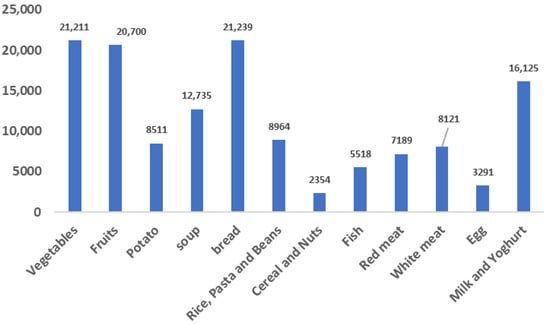

The weekly edible food waste generation per household is estimated at 0.97 ± 0.07 kg, which amounts to an annual average of 50.25 ± 3.64 kg. This waste has an environmental impact, though the associated carbon emissions are relatively low. Specifically, the waste generates 1.22 × 10−3 CO2-eq annually, resulting in a comparatively small daily carbon footprint compared to other studies. The percentage distribution of household food waste is shown in Figure 1. Unless otherwise specified, all quantitative results reported in this manuscript refer to the Irish household food waste dataset collected in this study (1000 surveyed households during 2023–2024) and are expressed per kilogram of discarded product, using footprint coefficients reported by [5,12].

Figure 1.

Average food waste items per wet weight generated by Irish households. The horizontal axis lists food categories, and the vertical axis presents average waste per household per week (g).

Figure 1 presents the distribution of household food waste by weight across the 12 food categories. Vegetables (21,210.71 g), bread (21,239.10 g), and fruits (20,700 g) represent the largest quantities of food waste generated by Irish households. These high amounts are likely driven by spoilage, perishability, and frequent consumption of these items. Other substantial contributions include milk and yogurt (16,124.90 g) and rice, pasta, and beans (12,735.40 g). In contrast, eggs (3291.43 g) and cereal and nuts (2354.29 g) account for the lowest quantities of waste, reflecting their longer shelf life and greater stability during storage.

The data on food waste distribution indicates that bread (15.62%), vegetables (15.60%), and fruits (15.23%) are the predominant categories of waste by weight. This pattern aligns with findings in other European countries, where perishable items like bread and fresh produce often dominate household food waste [15]. The high waste rates in these categories suggest common issues such as over-purchasing, improper storage, and a lack of utilization of perishable goods before they spoil [16].

Interestingly, beef waste contributes to over 50% of the total carbon footprint from household food waste, despite constituting only 4% of the total waste by weight. This significant impact is attributed to the high GHG emissions involved in beef production, including energy inputs for animal feed and livestock maintenance [17]. Targeting food waste reduction in high-impact foods such as beef could yield considerable environmental benefits. On the other hand, vegetables and fruits make up a larger proportion of the total waste by weight (72%) but account for less than 18% of the overall carbon footprint. Similar findings were reported by [18] who highlighted that while red meat has a disproportionate impact on GHG emissions, plant-based foods have a smaller impact despite their higher volume of waste. In terms of water usage, the total water footprint of household food waste is 23.72 m3 annually, underscoring the resource-intensive nature of food production. Moreover, the economic loss due to food waste is significant, amounting to €2690 per household annually.

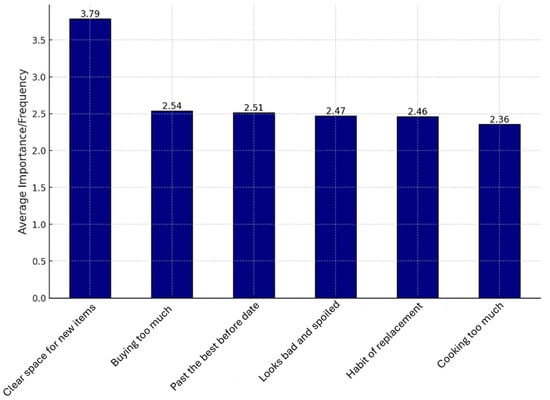

The analysis of food waste reasons, as visualized on Figure 2, reveals significant behavioral and logistical factors contributing to food disposal at the household level. The most frequently cited reason for food waste is clearing space for new items, suggesting that waste often results from storage limitations rather than spoilage. This finding is consistent with previous studies, such as [19], which indicate that households tend to discard food to make room for newly purchased items, particularly in developed countries where frequent grocery shopping is common. This behavior underscores a systemic issue in food consumption patterns, where household food management practices directly influence waste generation rather than just food perishability alone.

Figure 2.

The most frequently reported reasons for household food waste, based on survey responses.

The second most prevalent reason for food waste is buying too much, reflecting consumer habits of over-purchasing beyond actual consumption needs. This aligns with the observations of [6], who found that bulk purchasing promotions and misjudged consumption rates significantly contribute to food waste in high-income countries. This behavior is particularly relevant to perishable items like bread and dairy, which are commonly discarded before consumption due to their limited shelf life. Similarly, a study by [20] reported that food waste in Canadian households was primarily driven by habitual over-purchasing and a lack of structured meal planning, further reinforcing the role of consumer purchasing behavior as a critical determinant of food waste. The most frequently reported reasons for household food waste were spoilage due to improper storage (37%), preparation of excessive quantities leading to leftovers (24%), and confusion over date labels (18%). Portion management issues and overcooking were also notable contributors, particularly for perishable items such as vegetables and bread.

Another key factor contributing to food waste is expiration-based disposal, as indicated by the high frequency of respondents citing “past best-before date” as a reason for discarding food. This trend highlights a critical misunderstanding of food labeling practices, leading to premature disposal of still-edible products. Studies by [21] have demonstrated that consumers frequently misinterpret best-before dates as indicators of food safety rather than quality, a misunderstanding that disproportionately affects dairy products. Ref. [22] found that label modifications and public awareness campaigns led to a 27% reduction in dairy waste, emphasizing the importance of targeted educational interventions.

Aesthetic and spoilage concern also play a role in food waste, as evidenced by the significant proportion of respondents who cited “looks bad/spoiled” as a reason for disposal. This behavior is particularly relevant to bread and bakery products, which are often discarded based on appearance rather than actual spoilage. Ref. [16] noted that perceived food quality standards influence consumer waste behaviors, particularly for perishable and processed products. These findings suggest that improving consumer understanding of food quality and enhancing storage conditions could mitigate unnecessary disposal.

Comparing these findings with existing literature reinforces the conclusion that structural and behavioral factors drive food waste as much as food perishability does. Studies by [20] emphasize that supermarket practices, such as bulk promotions and aesthetic quality controls, contribute to food waste at the consumer level by influencing purchasing behaviors. Similarly, Ref. [15] identified perishability as a leading factor in food waste, particularly for bread and dairy products, which aligns with the results from the dataset.

Given the significant role of storage limitations, misinterpretation of best-before dates, and over-purchasing in driving food waste, targeted interventions could substantially reduce waste in bread and dairy products. Policies focused on improving date labeling regulations, enhancing household food storage education, and implementing retail strategies such as discounting near-expiry products could help mitigate this issue. Studies have shown that proper storage of bread in airtight conditions extends its shelf life by up to 40% [23]. In conclusion, the analysis of food waste demonstrates a clear correlation between consumer behavior, retail practices, and waste generation, particularly for high-waste food categories like bread and dairy. While meat waste continues to dominate discussions due to its high per-unit environmental footprint, the sheer volume of wasted bread and dairy products necessitates greater attention in both policy and research. Future studies should further investigate the life cycle impact of interventions to quantify their effectiveness in reducing food waste at both household and commercial levels.

4. Discussion

4.1. Water Footprint of Household Food Waste

Table 2 indicates that the average daily water footprint linked to household food waste is estimated at 0.46 ± 0.04 m3 per household, resulting in an annual total of 167.90 ± 14.60 m3. This corresponds to approximately 460 L of water per day wasted on food that is never consumed. This figure represents roughly 20% of the water footprint per capita for food consumption in the EU region [24].

Comparatively, this is significantly higher than the estimated 19 m3 per capita water loss due to food waste in industrialized Asia [25]. The discrepancy could be attributed to dietary shifts towards more resource-intensive, meat-based diets [26]. This issue is particularly relevant in regions facing water scarcity and reliance on imported food, especially water-intensive products like beef and pork [26]. Estimates from other countries demonstrate varying levels of water loss associated with food waste: 66 m3 per household annually for Chinese households [27], 42 m3 for North America [5], 106 m3 for the United Kingdom [28], 44 m3 for Oceania [29], and 47.70 m3 for Spain [5]. These values encompass the entire food supply chain—including production, processing, distribution, and consumption stages—not just household-level waste. While our study focuses specifically on household food waste, these global estimates provide important context on the scale of water resource loss due to food wastage. In terms of specific food categories, beef accounts for 52% of the total water footprint of household food waste, followed by pork (9%), poultry (5%), and rice (4%), even though these food products have relatively lower waste volumes by weight. For instance, rice makes up only 4% of the total food waste. In contrast, plant-based foods such as lettuce, ginger, cucumber, tomato, and mushrooms contribute less than 1% to the total water footprint despite their higher waste volumes. Animal-based foods collectively account for 66% of the water footprint from household food waste, despite representing only 13% of the total waste by weight. These findings are consistent with previous studies, which indicate that animal-based food waste is responsible for significant water losses, despite its lower overall volume compared to plant-based food waste [20]. Transitioning towards a more plant-based diet, which includes a greater proportion of vegetables and fruits, could result in considerable savings, both in production and consumption stages [24]. In contrast, categories such as cereal and nuts (1.73%) and eggs (2.42%) show the lowest waste percentages, possibly due to their longer shelf life and lower household consumption rates compared to fresh produce. The overall trend suggests that perishable items like fruits, vegetables, and dairy products are the most wasted, reflecting both consumption habits and the challenges of managing fresh food items effectively. These insights highlight the importance of targeting these food categories in strategies aimed at reducing household food waste.

One of the primary drivers of Ireland’s elevated food water footprint might be its high proportion of discarded animal-based foods, particularly meat and dairy products. The study revealed that although meat and dairy waste account for only 13% of total waste by weight, they contribute 66% of the water footprint due to their intensive resource demands. Meat, especially beef, has one of the highest water footprints among food items, with beef production requiring approximately 15,400 L of water per kilogram. These findings align with prior studies emphasizing the disproportionate environmental impact of animal-based food waste [3,17,28].

In contrast, China’s lower household food water footprint can be attributed to its predominantly plant-based diet, which relies more on grains, vegetables, and legumes [19]. Studies suggest that a shift toward plant-based diets could reduce the water footprint of food consumption by 35–55%, highlighting the role of dietary choices in shaping resource efficiency [14]. While Spain’s Mediterranean diet includes substantial vegetable consumption, its higher seafood waste inflates the overall water footprint, as fish and shellfish farming demand significant freshwater resources [28].

Bread waste was also found to be a major contributor to household food waste in Ireland, constituting 15.62% of total waste. Although bread has a lower unit water footprint (1600 L per kilogram) compared to meat, its frequent disposal significantly contributes to total resource losses [15]. Spain’s food waste composition features greater seafood waste, while China’s rice- and noodle-based dietary patterns result in lower staple grain waste due to portion control and frequent consumption of leftovers [27].

International Policy Interventions in Food Waste Reduction

Several countries have successfully implemented policies to curb food waste, offering valuable insights for Ireland. France has been at the forefront of legislative action, introducing laws in 2016 that prohibit supermarkets from disposing of unsold food, instead requiring them to donate surplus items to charities and food banks [29]. This policy has significantly reduced food waste at the retail level and has been recognized as a model for reducing waste within the supply chain [23]. Implementing similar regulations in Ireland could help reduce retail-level waste, particularly for high-water-footprint foods such as meat and dairy.

Denmark has demonstrated the effectiveness of consumer education campaigns in reducing household food waste. Through initiatives such as public awareness programs, improved supermarket food waste labeling, and household waste audits, Denmark successfully reduced national food waste by 25% in just five years. The Danish approach highlights the role of behavioral change in food waste reduction, emphasizing that consumer engagement and education are equally important as policy enforcement [30]. Ireland could benefit from similar public education initiatives aimed at improving food storage practices and promoting meal planning to mitigate over-purchasing.

Spain has focused on food donation programs to address surplus food waste, particularly in bakeries and supermarkets. Policies incentivizing businesses to donate unsold bread, dairy, and fresh produce to food banks have been shown to reduce bread waste by 33% in participating regions [24]. Given that bread is the second most wasted food category in Ireland, adopting a similar donation-based approach could significantly lower the environmental and economic costs associated with food waste.

China’s “Clean Plate” campaign, launched in 2020, provides another example of a nationwide food waste reduction strategy, emphasizing public engagement, school education, and restaurant portion control to discourage excessive food ordering and promote responsible consumption [19]. This campaign builds upon existing food conservation traditions, demonstrating the effectiveness of cultural reinforcement in shaping sustainable behaviors. Ireland could adapt a similar public engagement strategy to encourage portion control and mindful consumption.

4.2. Economic Impacts of Household Food Waste

Table 3 shows that the average household generates approximately 0.97 ± 0.07 kg of edible food waste per week, which amounts to 50.25 ± 3.64 kg annually. This level of waste is associated with a carbon footprint of about 1.22 × 10−3 kg CO2-eq per annum and a water footprint of 21.84 m3 per annum. The economic cost of this wasted food is also notable, reaching approximately €22 per week or €1144 per year per household. These findings underscore the significant environmental and economic implications of household food waste. As highlighted by [12], greenhouse gas emissions from food production are particularly high for certain food groups such as meat, meaning that reductions in household waste can lead to meaningful sustainability gains and cost savings.

Table 3.

Characteristics of average weekly and annual household edible food waste, including carbon footprint (GHG emissions), water footprint, and associated economic costs. Data presented as mean values ± standard deviations. Values are based on Irish household food waste data (1000 households, 2023–2024), reported per household per week and per year as indicated.

4.3. Global Warming Potential (GWP)

The following values are emission factors per kilogram of food product, not direct household totals, and are used to calculate the household-level emissions reported in Table 2. For the Irish household food waste dataset analyzed in this study (1000 surveyed households during 2023–2024), the following literature based GWP emission factors were applied to estimate the environmental impact of each food category: red meat waste exhibits the highest global warming potential, with an average factor of 27 kg CO2-eq per kilogram of discarded product, followed by white meat (≈6 kg CO2-eq/kg) and fish (≈5 kg CO2-eq/kg), based on footprint coefficients reported by [12]. Plant based foods such as vegetables and potatoes have significantly lower GWP values. These per kilogram factors are used in combination with the measured household waste quantities (Table 2) to calculate total carbon emissions. For example, the average Irish household in this study discards 0.97 ± 0.07 kg of edible food per week, corresponding to a total carbon footprint of 2.35 × 10−5 kg CO2-eq per week and 1.22 × 10−3 kg CO2-eq per year as summarized in Table 2. The GWP values cited here reflect product specific impacts rather than household totals, ensuring consistency between the literature derived emission factors and the aggregated weekly/annual impacts reported in Table 2.

4.4. EN-EC Footprint Index

The EN-EC footprint index, combining environmental and economic impacts, is highest for red meat, followed by white meat and eggs. Plant-based foods have significantly lower indices, reinforcing their overall sustainability. Research consistently shows that plant-based diets result in lower environmental impacts and economic costs compared to animal-based diets. For example, Ref. [14] found that adopting a global plant-based diet could reduce food-related GHG emissions by up to 70% and lower healthcare costs. The EN-EC footprint index supports global efforts to transition to more sustainable diets. Policies promoting plant-based diets could significantly reduce environmental pressures and improve public health outcomes.

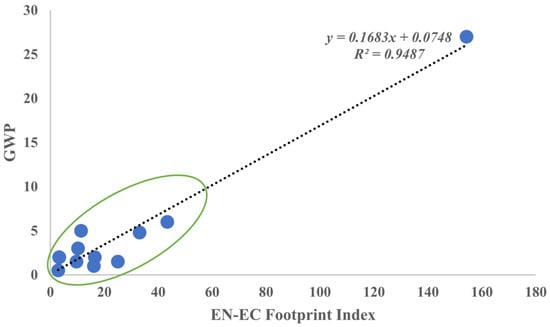

Figure 3 demonstrates a strong linear relationship between the EN-EC Footprint Index and Global Warming Potential (GWP), as evidenced by an R2 value of 0.94. This high correlation suggests that increasing the environmental and economic footprint (EN-EC) leads to a significant rise in GWP, which is consistent with studies showing that integrated footprint analyses are effective in predicting climate impacts. For instance, Ref. [31] highlight that combining environmental metrics with economic assessments is crucial in identifying major drivers of GHG emissions across food systems.

Figure 3.

Performance of EN-EC index against carbon footprint of Irish household FW. (EN-EC (dimensionless composite score; normalized values integrating environmental and economic impacts), GWP (kg CO2-eq/kg)). Circle marker indicates 95% confidence intervals.

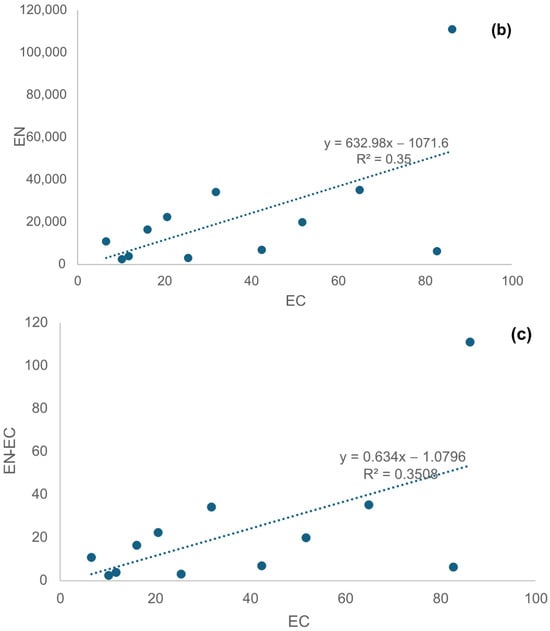

Figure 4 examines the relationships between environmental impact (EN), economic impact (EC), and a new EN-EC Footprint index, highlighting the statistical strength of these relationships using linear regression models. The results, depicted in the three panels, suggest complex and varied interactions between environmental and economic factors, with implications for sustainability research and policymaking.

Figure 4.

General linear relationship between: (a) Environmental impact (EN) and economic cost (EC); (b) Environmental impact (EN) and EN-EC Footprint Index; (c) Economic cost (EC) and EN-EC Footprint Index.

In this study, the EN-EC Index shows a stronger correlation with environmental impact (EN) than with economic cost (EC), reflecting the nature of Irish household food waste patterns. (EN-EC (dimensionless composite score; normalized values integrating environmental and economic impacts), EC (€), EN (kg CO2-eq)).

The first panel demonstrates a perfect linear relationship between the EN-EC Footprint index and environmental impact (EN), with an R2 value of 0.97. This suggests that the EN-EC Footprint index is highly sensitive to environmental factors such as GHG emissions and water footprints. The tight clustering of data points within the 95% confidence interval indicates a reliable model fit. Similar findings have been observed in studies that directly correlate environmental indices with specific environmental metrics. For example, in life cycle assessment (LCA) studies, metrics such as the Global Warming Potential (GWP) are often used to assess the environmental impact of products, and these metrics are tightly linked to carbon emissions [32].

4.5. EN-EC Footprint Index and Economic Impact (EC)

Figure 4 clearly illustrates that the EN-EC Footprint Index is predominantly driven by environmental impact (EN), as shown by the strong linear relationship in panel (c) (R2 = 0.98), while the association with economic cost (EC) remains modest, as seen in panel (a) (R2 = 0.35) and weak in panel (b) (R2 = 0.3508). This pattern is consistent with findings by [33], who, in their analysis of household food waste in Daegu, South Korea, reported a similarly high correlation between composite sustainability indices and environmental factors (R2 ≈ 0.977), with only moderate alignment to economic loss (R2 ≈ 0.50).

The revised R2 values presented in Figure 4 reflect recalculations using updated footprint coefficients from [5,12]. These updates provided more regionally relevant data for Irish food categories, improving the correlation between EN EC and EC from 0.0088 in the initial analysis to 0.35 in the revised version. These findings align with those reported in Spain, where [33] identified spoilage as the leading driver of household food waste. Similar patterns were noted in South Korea [14], although cultural practices around portion sizes resulted in higher leftovers. At a global scale, Ref. [34] highlighted the universality of spoilage and date label confusion as key contributors. Despite contextual differences between Irish and Korean households, the shared emphasis on environmental drivers suggests a broader trend: environmental burdens—such as greenhouse gas emissions and water use—tend to dominate composite food waste metrics. This consistency supports the robustness and transferability of our EN-EC framework, while highlighting the importance of clearly communicating the relative influence of environmental versus economic components when applying or interpreting the index.

The relatively weak relationship between the EN-EC Index and EC (panel a) further underscore this point. The spread of data points and limited explanatory power suggest that economic costs of food waste—while relevant from a consumer or policy perspective—do not systematically align with the environmental intensities of discarded products. This decoupling reflects broader empirical patterns in the sustainability literature. For example, Refs. [35,36] observed that economic growth and environmental pressures are not always correlated across sectors or regions. Likewise, technological advances and efficiency improvements can reduce environmental impacts without proportional increases in cost [37], weakening the expected linkage between EC and EN-EC outcomes. Taken together, these findings emphasize the need for nuanced interpretation of composite indices like EN-EC and reinforce the value of disaggregating environmental and economic components in future food waste assessments.

Findings from the [29] indicate that while food waste reduction leads to household economic savings, the environmental benefits, such as reduced greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, are not proportionally reflected in financial gains. This suggests that market pricing mechanisms do not adequately account for environmental externalities, similar to our findings in Ireland. The study highlights that while economic benefits from food waste reduction may include lower household spending, productivity gains, and food security improvements, they do not align with environmental savings, which remain largely an external, unpriced benefit.

Similarly, research by [31] on economic drivers of household food waste found that higher economic prosperity does not necessarily lead to lower food waste levels across different EU countries. This suggests that pricing structures and consumer behavior play a greater role in food waste generation than income alone. Our study supports this conclusion by showing that economic waste costs do not strongly correlate with environmental impact, reinforcing the idea that subsidies and food pricing mechanisms distort the relationship between financial and environmental burdens.

An additional study by [20] focused on the potential energy and environmental footprint savings from food waste reduction. The researchers found that while reducing food waste improves resource efficiency and lowers emissions, these benefits are not always reflected in economic metrics. This aligns with our findings that food waste’s economic cost remains relatively low compared to its environmental impact, reinforcing the need for policy-driven pricing reforms.

The discrepancy between economic and environmental costs in food waste can be attributed to multiple factors. One significant issue is market distortions caused by government subsidies on meat and dairy products. Subsidies artificially lower the market price of high-impact foods, reducing the economic incentive for minimizing waste. Our study found that red meat waste contributes over 50% of the total carbon footprint from household food waste, despite constituting only 4% of total waste by weight. However, because of subsidies, the economic cost of this waste remains disproportionately low. Similar findings from the [31] suggest that subsidized food products lead to increased waste and a disconnect between economic and environmental impacts.

Another key factor is the undervaluation of environmental externalities in food pricing. Food production contributes significantly to environmental degradation, yet current pricing structures do not integrate external costs such as carbon emissions, water use, and biodiversity loss. Unlike other industries where carbon pricing mechanisms or pollution taxes exist, the food sector lacks comprehensive policies that would internalize these externalities into market prices. The result is an economic model that underestimates the environmental savings of food waste reduction, leading to weak correlations in economic analyses. Findings from the [20] study also support this, emphasizing the need for integrated life cycle costing approaches that better account for environmental and economic trade-offs.

A final explanation for the weak correlation could be structural differences in waste management costs across EU countries. Waste disposal fees, landfill taxes, and regulatory frameworks vary significantly, affecting how food waste is economically assessed. Some EU countries with higher landfill taxes and stricter waste policies report stronger economic correlations with environmental costs, whereas regions with lower disposal fees or less regulated waste systems, such as Ireland, tend to show weaker correlations. While our findings align with broader EU trends, Ireland’s food economy presents unique characteristics that may exacerbate the economic-environmental disconnect. The country’s heavy reliance on livestock and dairy farming, combined with food subsidy structures and relatively low landfill fees, contributes to a greater disparity between economic and environmental waste costs than in some other EU nations. Countries with higher food taxation policies and stricter waste regulations, such as those in Scandinavia and the Netherlands, may exhibit stronger economic-environmental correlations, a potential area for future comparative research.

Addressing this issue requires policy interventions that integrate environmental costs into food pricing, such as carbon pricing on food production, eco-taxation on high-waste food categories, and financial incentives for waste reduction programs. The findings from both our study and EU-wide research suggest that reforming food pricing structures and subsidy policies could help bridge the gap between economic and environmental food waste assessments. The presence of outliers in both the second and third panels is notable. These outliers could represent cases where unique circumstances (e.g., extreme pollution events or high-cost waste management scenarios) deviate significantly from the general trend. Such outliers are often observed in studies that assess the environmental and economic impacts of industrial activities [38]. These outliers may indicate that specific industries or regions have disproportionately high environmental or economic impacts relative to others.

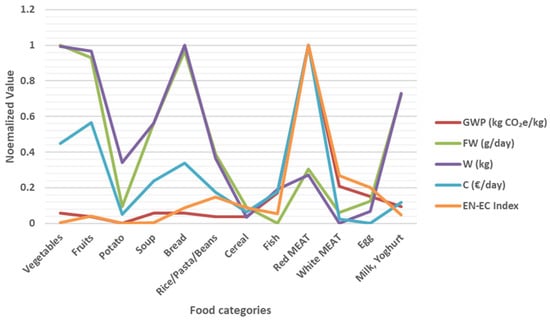

The normalized parallel coordinates graph (Figure 5). visually compares the environmental and economic impacts of different food categories, emphasizing the significant variations in water footprint, carbon emissions, and economic costs. This discussion integrates the findings from the graph with insights from relevant literature, exploring how these patterns align with or deviate from established knowledge.

Figure 5.

Normalized environmental and economic performance of the twelve food categories across six metrics: Global Warming Potential (GWP, kg CO2e/kg), Food Waste generation (FW, g/day), Waste mass (W, kg), Cost (C, €/day), and the combined EN-EC Footprint Index. All variables were normalized using Min–Max scaling (range 0–1) to enable comparability across metrics with different units and magnitudes. Higher normalized values represent greater relative impacts within each metric. Food categories include Vegetables, Fruits, Potato, Soup, Bread, Rice/Pasta/Beans, Cereal, Fish, Red Meat, White Meat, Egg, and Milk/Yoghurt.

The findings shown in this figure have important implications for sustainability research and policymaking. The strong linear relationship between the EN-EC Footprint index and environmental impact suggests that environmental policies aimed at reducing emissions and water use could have a direct and measurable impact on the EN-EC index. However, the weak relationships with economic factors indicate that economic policies alone may not be sufficient to drive significant improvements in environmental performance, and more targeted environmental interventions may be needed. The European Union’s Green Deal and Circular Economy Action Plan emphasizes the need for integrated approaches that combine environmental and economic policies to achieve sustainability goals [29]. The weak relationships in the second and third panels highlight the importance of these integrated approaches, where environmental and economic policies need to be carefully coordinated to avoid unintended consequences and ensure that both economic growth and environmental protection are achieved.

In summary, this figure suggests that while environmental impacts are closely tied to the EN-EC Footprint index, economic factors do not exhibit strong linear relationships with either the footprint index or environmental impact. This underscores the complexity of achieving sustainability goals, where economic and environmental systems may need to be addressed through multifaceted and integrated policies. The findings align with broader literature on the challenges of decoupling economic growth from environmental degradation and the importance of focusing on specific environmental metrics in sustainability assessments.

The economic impact of food waste varies by food category. In Ireland, beef and fish are major contributors to the economic cost of food waste, accounting for 21% and 13% of the total economic cost, respectively, despite comprising only a combined 6% of the total waste by weight [31]. Conversely, vegetables and fruits like watermelon, which constitute a larger portion of the waste by volume, account for a smaller percentage of the economic cost—10% and 5%, respectively. This discrepancy highlights the disproportionate economic impact of higher value items and underscores the need for targeted strategies to mitigate waste in these categories. We also appreciate the potential to incorporate calorific or nutritional value into the EN-EC Index, as it could provide additional insights into the relative sustainability of food categories. Our current approach aligns with conventional footprinting methods, but future research could explore how normalizing impacts by energy or protein content might shift sustainability rankings.

4.6. Exploring the Disconnect Between Economic and Environmental Costs

The disconnect between economic and environmental costs is a crucial aspect of food waste analysis, and we appreciate this insightful suggestion. Our current analysis highlights the disproportionate impact of high-water-footprint foods (e.g., meat and dairy) compared to their economic cost, but we agree that factors such as government subsidies, carbon pricing, and externalized environmental costs merit deeper investigation. Studies have shown that subsidized food production, particularly for meat and dairy, artificially lowers market prices while environmental externalities remain largely unaccounted for [3,33]. A more detailed policy-driven economic analysis could further elucidate how pricing distortions impact household food waste behaviors and associated environmental burdens.

The results indicate a clear disconnect between economic and environmental costs of food waste, particularly for high-impact foods such as meat and dairy. While these products contribute disproportionately to the carbon and water footprint of food waste, their economic cost per kilogram remains relatively low due to factors such as government subsidies, international trade dynamics, and the exclusion of externalized environmental costs from market pricing.

Studies suggest that subsidies for meat and dairy in the European Union artificially lower consumer prices, reducing the perceived financial impact of waste [3,33]. Meanwhile, environmental costs—such as carbon emissions, biodiversity loss, and water depletion—are not directly reflected in food prices, resulting in an economic-environmental cost imbalance [17]. Addressing this requires policy interventions such as carbon pricing on food products, tax incentives for waste reduction, and full-cost accounting frameworks that integrate environmental externalities into economic assessments [14].

A more in-depth exploration of these factors could further strengthen the economic-environmental analysis in future research. Additionally, a sensitivity analysis on the potential impact of including externalized costs in food pricing could provide a quantitative perspective on how policy-driven pricing adjustments might alter consumer waste behavior.

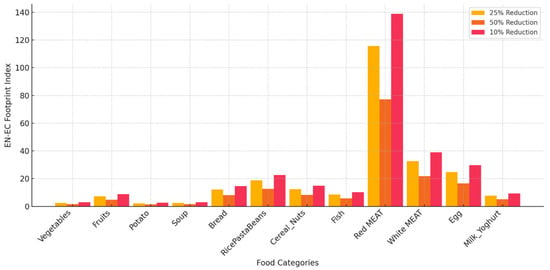

4.7. Environmental and Economic Footprint of Food Waste Reduction Scenarios

The EN-EC Footprint Index, a composite metric integrating Global Warming Potential (GWP), Water Footprint (WF), and Economic Impact (C), provides a holistic assessment of the environmental and economic burden of food waste across different reduction levels. Figure 6 illustrates the variation in the EN-EC Footprint Index for various food categories under 10%, 25%, and 50% food waste reduction scenarios.

Figure 6.

EN EC Footprint Index (dimensionless composite score) for different food waste reduction scenarios across various food categories. The index integrates Global Warming Potential (GWP, kg CO2-eq), Water Footprint (WF, m3), and Economic Impact (C, €)—normalized and combined—to assess the overall environmental and economic burden.

The results reveal distinct disparities in the environmental and economic burdens among different food groups:

- High-impact categories: Red meat exhibits the highest footprint values, with an EN-EC Footprint Index of 138.86 at a 10% reduction level, decreasing to 115.72 at 25% reduction and 77.15 at 50% reduction. This trend aligns with previous studies highlighting the disproportionate contribution of livestock products to environmental degradation due to high GWP (27 kg CO2-eq/kg) and water footprint (15,400 L/kg) [3].

- Moderate-impact categories—white meat, eggs, and fish—show EN-EC Index values ranging from approximately 30 to 110 across scenarios, consistent with literature estimates of GWPi between 4.8 and 6.0 kg CO2-eq/kg and WFi from 1127 to 4325 L/kg [5,12]. These findings confirm their intermediate environmental burdens compared to high-impact red meat (GWPi = 26.6; WFi = 15,415) and low-impact plant-based categories like vegetables or fruits. The reduction across 10%, 25%, and 50% minimization scenarios further highlights the disproportionate environmental savings possible by targeting animal-based foods.

- Lower-impact categories: Vegetables, potatoes, and soup display the lowest footprints, with vegetables exhibiting an EN-EC Footprint Index of 2.93 at 10% reduction, decreasing to 2.44 at 25% and 1.63 at 50%. Similar trends have been reported in life cycle assessment (LCA) studies [39], reinforcing the low environmental impact of plant-based foods.

Reduction in Footprint Across Categories: The graph demonstrates a consistent decline in the footprint index as food waste is minimized. This trend highlights the potential for substantial environmental gains through waste prevention strategies, consistent with findings by [40] who emphasized that reducing food waste at the consumption stage is one of the most effective sustainability interventions. The graph distinctly illustrates the disproportionate environmental burden of animal-derived products (red meat, white meat, and fish). This aligns with the study by [14] Springm, which found that shifting to plant-based diets could reduce food-related greenhouse gas emissions by up to 70%. The correlation between economic expenditure (C, Euro/day) and footprint values is evident, particularly in high-cost items such as red meat and fish. The cost inefficiency of these items is further exacerbated by their high water and carbon footprints, as previously demonstrated by [5].

4.7.1. Implications of Different Reduction Levels

The 50% reduction scenario in the graph shows the greatest impact in footprint minimization, reinforcing the effectiveness of policy-driven food waste interventions. This supports previous research by [41], which emphasized that reducing food waste in livestock-based products is one of the most effective strategies for lowering the overall environmental footprint.

4.7.2. Environmental and Economic Contributors to the EN-EC Footprint Index

The analysis of individual components contributing to the EN-EC Footprint Index demonstrates the following:

- Global Warming Potential (GWP): Food categories with higher GWP values (e.g., Red Meat: 27 kg CO2-eq/kg, White Meat: 6 kg CO2-eq/kg) exhibit significantly higher footprint values. This aligns with findings from [13], which underscore the dominant role of livestock in global GHG emissions.

- Water Footprint (WF): Categories with excessive water demand, such as Red Meat (15,400 L/kg) and White Meat (4325 L/kg), further exacerbate environmental impacts, consistent with findings from [34].

- Economic Cost (C, Euro/day): Economic expenditures on high-impact food categories, such as Red Meat (€86.27/day) and Fish (€82.77/day), significantly contribute to their overall footprint, reinforcing the economic inefficiencies of resource-intensive foods [14].

Given the observed trends, the following policy and behavioral interventions are recommended:

- Targeted waste reduction policies: Governments should incentivize waste reduction in high-impact categories to achieve maximum environmental benefits [40].

- Dietary shifts and consumer awareness: Encouraging plant-based diets could lower the overall environmental burden of food production, as supported by the EAT-Lancet Commission [42].

- Circular economic approaches: Valorization of food waste through anaerobic digestion or composting could further mitigate environmental impacts and enhance resource efficiency [43].

4.8. Scenario Analysis: Impact of a 50% Reduction on Household Meat Waste

To explore the potential environmental and economic benefits of reducing household meat waste in Ireland, we conducted a hypothetical scenario analysis assessing the impacts of a 50% reduction in meat waste. Given that meat products, particularly beef, have a disproportionately high environmental footprint despite lower waste volumes, targeted reductions in this category could yield significant sustainability benefits.

Using the Environmental-Economic Footprint (EN-EC) Index dataset, we estimated reductions in carbon emissions, water usage, and economic costs resulting from halving the waste of four key meat categories: beef, pork, poultry, and fish. The analysis applied a 50% reduction multiplier to the respective environmental and economic parameters, yielding the following results:

- CO2 emissions reduction: 2.50 kg CO2-eq

- Water usage reduction: 563.50 L

- Economic savings: €3623.48

These reductions are based on the Irish household dataset (1000 households, 2023–2024) and represent annualized household-level impacts. These findings underscore the significant role of meat waste reduction in mitigating environmental impacts and reducing household-level financial losses. Given that red meat waste contributes over 50% of the total carbon footprint of household food waste despite comprising only 4% of waste by weight, these results align with previous studies emphasizing the outsized impact of animal-based food waste [3,17].

This scenario analysis provides quantifiable targets for policymakers seeking to develop food waste reduction strategies. By implementing targeted interventions—such as improved consumer education on portion control, enhanced food labeling, and incentives for waste minimization, substantial progress can be made in reducing both environmental burdens and household food-related expenses. Future research should expand on this analysis by incorporating broader dietary shifts, alternative protein sources, and behavioral interventions, offering a more comprehensive framework for national food waste reduction policies in Ireland [44,45,46].

4.9. Policy Strategies for Reducing Beef Waste

The results of this study highlight the significant financial and environmental burden associated with red meat waste, given its high economic cost per unit and substantial water and carbon footprints. Despite comprising a relatively small portion of total food waste by weight, beef accounts for a disproportionate share of the overall environmental impact of food waste due to its intensive resource demands. To effectively address this issue, targeted policy interventions at the consumer, retail, and supply chain levels are necessary.

4.9.1. Economic Incentives for Waste Reduction

Given that beef is a high-value food product, economic interventions that provide financial incentives for waste reduction could be effective. Policies such as:

- Dynamic pricing and markdowns for near-expiry beef products: Retailers could implement progressive discounting on beef as it approaches its expiration date, similar to successful food waste reduction models in countries like Japan and Denmark [30]. This strategy encourages consumers to purchase meat closer to its sell-by date rather than discarding unsold products.

- Tax incentives for food donation: Governments could expand tax benefits for restaurants, retailers, and food service providers that donate surplus beef products to food banks. France has demonstrated the effectiveness of such policies, where supermarket food donation laws have led to a substantial decrease in food waste at the retail level [29].

4.9.2. Consumer Awareness and Behavior Change

Consumer behavior plays a crucial role in beef waste, as misinterpretation of expiration labels and poor meal planning contribute to premature disposal of meat products. Public awareness campaigns could:

- Educate consumers on proper meat storage: Studies indicate that freezing beef at optimal temperatures could extend its shelf life by up to six months, yet many consumers discard beef unnecessarily due to misconceptions about freezing and thawing [24]. A national awareness campaign, similar to Denmark’s “Stop Wasting Food” initiative, could inform consumers about safe storage practices.

- Improve date labeling regulations: Misinterpretation of “best-before” and “use-by” labels often leads to avoidable food waste [21]. Standardizing and clarifying date labeling for beef and other perishable products—as seen in the Netherlands’ regulatory framework—could reduce unnecessary disposal.

4.9.3. Supply Chain and Retail-Level Interventions

In addition to consumer behavior, supply chain inefficiencies contribute to beef waste at multiple stages. Policies that address losses in transportation, storage, and retail distribution could significantly reduce beef waste:

- Optimizing portion sizes in food service: Large portion sizes in restaurants and catering services contribute to plate waste, particularly for high-protein foods like beef [33]. Regulations encouraging smaller, customizable portion sizes in restaurants—as successfully implemented in China’s “Clean Plate” campaign—could help mitigate this issue.

- Encouraging supply chain transparency: Many losses occur at the slaughterhouse and distribution stages, where spoilage and inefficiencies contribute to waste. Mandating transparent reporting on meat waste at the industry level could improve logistics and efficiency in beef supply chains.

5. Conclusions

This study presents an innovative approach to assessing the environmental and economic impacts of household food waste through the development of the Environmental-Economic Footprint (EN-EC) Index. By integrating carbon emissions, water footprint, and economic costs, the EN-EC Index provides a comprehensive framework for evaluating the dual burden of food waste in Ireland. This multidimensional assessment surpasses traditional single-focused methods, offering policymakers a more data-driven tool to develop effective waste reduction strategies.

The findings highlight the disproportionate environmental and financial impact of specific food categories, particularly meat, bread, and dairy waste, underscoring the need for targeted interventions to enhance sustainability efforts. Red meat, despite comprising only 4% of household food waste by weight, accounts for over 50% of the total carbon footprint, emphasizing the urgent need for policy measures to mitigate high-impact food waste. Similarly, bread and dairy waste contribute significantly to economic losses due to over-purchasing, misinterpretation of expiration labels, and improper storage.

A key insight from this study is the weak relationship between economic and environmental costs of food waste. This disconnect arises due to market distortions, government subsidies, and externalized environmental costs, which lower the economic burden of high-impact foods while their environmental footprint remains significant. Addressing these inefficiencies requires policy-driven pricing mechanisms, such as eco-taxation on high-waste foods, aligning food prices with their environmental impact and reallocating subsidies from livestock production toward sustainable protein alternatives.

This study also benchmarks Ireland’s food waste patterns against those of other countries, identifying best practices in waste reduction policies: France’s supermarket food donation laws, which significantly reduced retail-level waste; Denmark’s public awareness campaigns, which led to a 25% national reduction in household food waste; and China’s “Clean Plate” initiative, successfully targeting plate waste in the food service sector. Furthermore, a 50% reduction in household meat waste was modeled to estimate quantifiable benefits, demonstrating a CO2 emissions reduction of 2.50 kg CO2-eq., water savings of 563.50 L, and economic savings of €3623.48 annually per household. These findings emphasize the potential impact of policy-driven interventions, reinforcing the importance of waste reduction strategies that combine financial incentives, consumer education, and regulatory measures.

Finally, our study focuses on immediate economic and environmental impacts, we acknowledge that a life-cycle costing (LCC) approach or an extended cost–benefit analysis could provide a more holistic perspective by incorporating these long-term effects.

From a practical perspective, the EN-EC Index can support public institutions, local authorities and waste-management agencies in prioritizing targeted interventions, guiding food redistribution programs, and informing date-labeling reforms, dynamic pricing and consumer education. For policymakers, the index offers a decision-support tool that can be adapted to evaluate policy scenarios, track SDG 12.3 progress, and identify the cost–benefit balance of behavioral or infrastructure-based interventions.

Future research could integrate environmental damage valuation, carbon pricing, and ecosystem service losses to better capture the full financial burden of food waste. The EN-EC framework could also be strengthened by incorporating direct waste measurement (e.g., compositional audits, sensor-enabled smart bins) to complement self-reported estimations. Applying demographic weighting or quota sampling would also improve representativeness and allow behavioral and socioeconomic subgroup analyses. By providing data-driven insights, the EN-EC Index contributes to the global discourse on food sustainability, offering policymakers a practical tool to design targeted and effective waste reduction strategies. Addressing food waste through integrated policy, consumer education, and supply chain interventions is essential for building a more sustainable and resource-efficient food system in Ireland and beyond.

Limitations

A key limitation of this study is the use of water footprint coefficients sourced from Korean studies [26], which may not fully reflect the water use characteristics of Irish agricultural systems. Agricultural water footprints are influenced by numerous regional variables including climate, irrigation practices, and crop/livestock types. The absence of publicly available Irish-specific WFi data necessitated reliance on international coefficients, which may introduce estimation bias. Future efforts should aim to develop regionally appropriate WFi databases to improve the geographic validity of sustainability indicators such as the EN-EC Index.

This study’s online voluntary response format resulted in an over-representation of females, higher-educated individuals, and higher-income and urban households compared with existing Irish national survey data. While the sample covers all 26 counties, the demographic skew may limit the generalizability of behavior-waste relationships to under-represented groups (e.g., lower-income, lower-education). To mitigate this, no regional or subgroup comparisons were made, and results were interpreted at the population level.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/su172411184/s1, Section S1: Full version of the household food waste survey questionnaire (Ireland, 2023–2024); Table S1: Food categories, example items, and assumed raw equivalents; Table S2: Carbon and water footprint coefficients and data sources; Table S3: Step-by-step calculation details for weekly edible household food waste (TotalFW_gPerWeek) based on survey responses (n = 879); Table S4: Comparison of old and updated footprint coefficients and resulting EN-EC Index values for major food categories.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.B. and A.P.; methodology, M.B.; software, M.B.; validation, M.B. and P.H.; formal analysis, M.B.; investigation, M.B. and C.K.; data curation, C.K.; resources, P.H. and A.P.; writing—original draft preparation, M.B.; writing—review and editing, P.H., A.P. and C.K.; visualization, M.B.; supervision, P.H. and A.P.; project administration, P.H.; funding acquisition, A.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Irish Research Council [Project ID: COALESCE/2022/804] under the framework of the FORWARD project (Food Waste in Ireland—Assessment, Environmental & Economic Burden, and Mitigation Strategies).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Technological University Dublin (Ethics number REIC-21-106) February 2022.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be shared upon request.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the members of the Spatiotemporal Environmental Epidemiology Research (STEER) group at the Environmental Sustainability & Health Institute, as well as the Economics for a Healthy Society & Green Sustainable Communities (EcoLOGIC) Research group at Technological University Dublin, for their assistance and support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| EN-EC | Environmental–Economic Footprint Index |

| GWP | Global Warming Potential |

| WF | Water Footprint |

| EPA | Environmental Protection Agency |

| CSO | Central Statistics Office |

| GHG | Greenhouse Gas |

| LCA | Life Cycle Assessment |

| EU | European Union |

| CO2-eq | Carbon Dioxide Equivalent |

| EC | Economic Cost |

| EN | Environmental Impact |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| Eq. | Equation |

References

- Stenmarck, Å.; Jensen, C.; Quested, T.; Moates, G. Estimates of European Food Waste Levels; FUSIONS EU Project Report; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Werf, P.; Seabrook, J.A.; Gilliland, J.A. Food for thought: Comparing self-reported versus actual household food waste behavior. Waste Manag. 2019, 87, 238–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poore, J.; Nemecek, T. Reducing food’s environmental impacts through producers and consumers. Science 2018, 360, 987–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) Ireland. Food Waste in Ireland. 2022. Available online: https://www.epa.ie/publications/circular-economy/resources/epa-circular-economy-national-food-waste-survey-2022---survey-data.php/ (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Mekonnen, M.M.; Hoekstra, A.Y. The green, blue and grey water footprint of crops and derived crop products. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2011, 15, 1577–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aschemann-Witzel, J.; de Hooge, I.E.; Amani, P.; Bech-Larsen, T.; Oostindjer, M. Consumer-related food waste: Causes and potential for action. Sustainability 2015, 7, 6457–6477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stop Food Waste. Food Waste in Irish Households. 2022. Available online: https://www.stopfoodwaste.ie/ (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Quested, T.E.; Marsh, E.; Stunell, D.; Parry, A.D. Spaghetti soup: The complex world of food waste behaviours. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2013, 79, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Werf, P.; Gilliland, J.A. A systematic review of food losses and food waste generation in developed countries. Waste Resour. Manag. 2017, 170, 66–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Xue, L.; Li, Y.; Liu, X.; Cheng, S.; Liu, G. Horeca food waste and its ecological footprint in Lhasa, Tibet, China. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 136, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, P.; Mohanty, A.K.; Dick, P.; Misra, M. A Review on the Challenges and Choices for Food Waste Valorization: Environmental and Economic Impacts. ACS Environ. Au 2023, 3, 58–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Clune, S.; Crossin, E.; Verghese, K. Systematic review of greenhouse gas emissions for different fresh food categories. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 140, 766–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IUNA. National Adult Nutrition Survey; Irish Universities Nutrition Alliance: Dublin, Ireland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Adelodun, B.; Kim, S.H.; Odey, G.; Choi, K.S. Assessment of environmental and economic aspects of household food waste using a new Environmental-Economic Footprint (EN-EC) index: A case study of Daegu, South Korea. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 776, 145928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hebrok, M.; Heidenstrøm, N. Contextualising food waste prevention—Decisive moments within everyday practices. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 210, 1435–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Göbel, C.; Langen, N.; Blumenthal, A.; Teitscheid, P.; Ritter, G. Cutting food waste through cooperation along the food supply chain. Sustainability 2015, 7, 1429–1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridoutt, B.G.; Sanguansri, P.; Freer, M. Water and GHG footprints of beef production systems in southern Australia. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 211, 378–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldeira, C.; De Laurentiis, V.; Corrado, S.; van Holsteijn, F.; Sala, S. Quantification of food waste per product group along the food supply chain in the European Union: A mass flow analysis. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 149, 479–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Fu, S.; Liu, X. The Effect of Plate and Decoration Color on Consumer Food Waste in Restaurants: A Case of Four Chinese Cities. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parizeau, K.; von Massow, M.; Martin, R. Household-level dynamics of food waste production and related beliefs, attitudes, and behaviours in Guelph, Ontario. Waste Manag. 2015, 35, 207–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Boxstael, S.; Devlieghere, F.; Berkvens, D.; Vermeulen, A.; Uyttendaele, M. Understanding and attitude regarding the shelf life labels and dates on pre-packed food products by Belgian consumers. Food Control 2014, 37, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garnett, T.; Mathewson, S.; Angelides, P.; Borthwick, F. Policies and Actions to Shift Eating Patterns: What Works? Food Climate Research Network, University of Oxford: Oxford, UK, 2018; Available online: https://www.tabledebates.org/sites/default/files/2020-10/fcrn_chatham_house_0.pdf (accessed on 4 December 2025).

- Wilson, N.L.W.; Rickard, B.J.; Saputo, R.; Ho, S.T. Food waste: The role of date labels, package size, and product category. Food Qual. Prefer. 2017, 55, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanham, D.; Mekonnen, M.M.; Hoekstra, A.Y. The water footprint of the EU for different diets. Ecol. Indic. 2013, 32, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.H.; Lee, J.W.; Park, J.Y. Assessing the sustainability of dietary patterns: Integrating environmental, nutritional, and economic dimensions. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.; Jung, S. Exploring the influence of cultural values on food waste: A case study of Korea. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4140. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Z.; Sun, D.; Liu, Y. Understanding household food waste in China: National survey results. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 161, 1240–1249. [Google Scholar]

- Bahramian, M.; Hynds, P.D.; Priyadarshini, A. An Environmental and Economic Assessment of Household Food Waste Management Scenarios in Ireland. Recycling 2025, 10, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. A New Circular Economy Action Plan: For a Cleaner and More Competitive Europe; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- WRAP. Estimates of Food Surplus and Waste Arisings in the UK; Waste and Resources Action Programme: Banbury, UK, 2017; Available online: https://wrap.org.uk (accessed on 4 December 2025).

- Gencia, A.D.; Balan, I.M. Reevaluating Economic Drivers of Household Food Waste: Insights, Tools, and Implications Based on European GDP Correlations. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levasseur, A.; Lesage, P.; Margni, M.; Deschenes, L.; Samson, R. Considering time in LCA: Dynamic LCA and its application to global warming impact assessments. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2010, 44, 3169–3174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Herrero, I.; Margallo, M.; Laso, J.; Batlle-Bayer, L.; Bala, A.; Fullana-i-Palmer, P.; Vázquez-Rowe, I.; González, M.J.; Amo, F.; Durá, M.J.; et al. Nutritional data management of food losses and waste under a life cycle approach: The case study of the Spanish agri-food system. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2019, 82, 103223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kummu, M.; de Moel, H.; Porkka, M.; Siebert, S.; Varis, O.; Ward, P.J. Lost food, wasted resources: Global food supply chain losses and their impacts on freshwater, cropland, and fertiliser use. Sci. Total Environ. 2012, 438, 477–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bithas, K.; Kalimeris, P. Revisiting the decoupling hypothesis: Is there an empirical relationship between environmental and economic performance? Ecol. Econ. 2013, 93, 17–24. [Google Scholar]

- Mazzanti, M.; Zoboli, R. Waste generation, waste disposal and policy effectiveness: Evidence on decoupling from the European Union. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2008, 52, 1221–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popp, D. Innovation and Climate Policy. 2010. Available online: https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w15673/w15673.pdf (accessed on 2 November 2025).

- Pearce, D. Is the construction sector sustainable? Definitions and reflections on its future. Build. Res. Inf. 2006, 34, 201–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]