Abstract

Humanity faces converging crises of climate change, biodiversity loss, inequality, and social fragmentation. These challenges are usually treated as technical or policy problems, yet their persistence suggests deeper causes in the paradigms through which human beings understand themselves and act in the world. Systems thinking highlights that paradigms shape perception, motivation, and institutions, but it does not specify which paradigms best support sustainability. This article develops a conceptual framework to examine how paradigms of human nature have shifted historically and how these shifts influence sustainability outcomes. Using a comparative synthesis of wisdom traditions (Greek, Islamic, Christian, Jewish, Hindu, Confucian, and Daoist) together with modern and late-modern frameworks, the study identifies key differences in how human faculties and values are ordered, and how these differences manifest in ecological and social outcomes. A paradigm–perception–intention–action–impact feedback model is introduced to explain how worldviews propagate into institutions and outcomes, and how inversions contribute to ecological overshoot, inequality, and dislocation. The article contributes a synthesized map of paradigms across traditions, a causal schema linking paradigm shifts to sustainability outcomes, practice-oriented design principles, and a research agenda for testing the framework in sustainability transitions. Re-examining paradigms is argued to be a critical leverage point for durable sustainability.

1. Introduction

Humanity today is confronted with an unprecedented convergence of crises. Climate change accelerates with intensifying extremes, biodiversity loss erodes the foundations of ecosystems, resource depletion undermines security, while inequality, polarization, and the erosion of shared meaning destabilize social life [1,2,3]. These disruptions are typically approached in isolation: as discrete technical, economic, or policy problems. Yet decades of effort have not delivered durable solutions. Instead, rebound effects, unintended consequences, and persistent “lock-ins” show that symptoms are treated while underlying causes remain largely unexamined [4,5,6,7].

Systems thinking provides a lens to move beyond this surface orientation. It teaches us that events are the visible tip of much deeper structures: patterns of behavior, institutional logics, and—most fundamentally—the mental models and paradigms through which people interpret reality and act within it [1,5]. Without attention to these deeper levels, interventions risk shifting burdens from one domain to another, or solving problems in the short term while reproducing them in the long term. Systems thinking thus directs attention to paradigms as the deepest leverage points: the assumptions about what it means to be human, what counts as knowledge, which ends are desirable, and how societies should pursue them [4,7].

Yet systems thinking itself does not prescribe which paradigms are appropriate for guiding sustainable action. Paradigms vary widely across history and culture. Modern frameworks often define the human being as an autonomous individual, a rational optimizer, or a self-constructing subject, prioritizing freedom of choice, technological mastery, and material progress [8,9,10]. Wisdom traditions across civilizations, by contrast, have articulated integrated anthropologies in which human faculties are oriented toward ethical, spiritual, and communal ends [11,12,13,14,15]. These divergent paradigms shape institutions, practices, and aspirations differently. As such, they have far-reaching consequences for sustainability: influencing whether societies treat nature as a resource to be mastered or as a living whole to be stewarded [16,17], whether sufficiency is valued or limitless desire is legitimized [7,18], whether community cohesion is cultivated or individual preference dominates [19,20]. This raises a pressing question for sustainability science:

How do paradigms of human nature shape the trajectories of social–ecological systems?

If contemporary crises reflect not only technical shortcomings but also paradigm drift, then understanding and comparing paradigms becomes essential. Historical wisdom traditions provide one set of resources; modern and late-modern frameworks offer another [21,22,23]. A systematic comparison may reveal both convergences and fractures, and in turn clarify what kinds of anthropological assumptions support or undermine the pursuit of sustainable futures.

The aim of this article is therefore to examine how paradigms of human nature have shifted across history, to compare the differences between traditional wisdom paradigms and contemporary modern/late-modern ones, and to explore how these differences manifest in sustainability outcomes. By analyzing paradigms at this deep level, the article seeks to illuminate why surface-level interventions so often fail, and how a reorientation of human self-understanding might contribute to more durable transitions [1,2,4].

To address this aim, the study employs a concept-building synthesis. We first conduct a comparative reading of selected wisdom traditions—Greek, Islamic, Christian, Jewish, Hindu, Confucian, and Daoist—to map how they conceptualize the human person and its faculties [11,12,13,24]. We then trace transformations in modernity and late modernity, examining how emerging philosophical and political frameworks altered or inverted earlier assumptions [8,9,10,25]. Using systems thinking tools, including the iceberg model and systems archetypes, we analyze how these paradigms propagate into institutions and outcomes, and how paradigm inversions generate sustainability threats and persistent lock-ins [1,4]. Finally, we translate the comparative insights into design principles and propose testable propositions to connect conceptual analysis with empirical research in sustainability transitions.

The guiding research questions are:

- RQ1. How have paradigms of human nature shifted historically, from wisdom traditions to modern and late-modern frameworks?

- RQ2. What are the key differences between traditional wisdom paradigms and contemporary paradigms in shaping sustainability outcomes?

- RQ3. How can insights from this comparative analysis be translated into design principles for sustainability practice, education, and policy?

- RQ4. What testable propositions can link these conceptual insights to empirical sustainability research?

The contributions of the article are fourfold. First, it synthesizes a map of paradigms of human nature across cultural and historical traditions. Second, it articulates a causal schema that links paradigm shifts to sustainability outcomes. Third, it derives practice-oriented principles for governance, pedagogy, and organizational design. Fourth, it sets out a research agenda that bridges conceptual insights with empirical sustainability science. Because paradigms operate at the highest level of abstraction, the analysis necessarily spans multiple traditions and historical periods, and this broad scope is essential for identifying the large-scale patterns that systems thinking aims to reveal.

The remainder of this article is organized as follows. Section 2 introduces the background and related work, along with the foundations of systems thinking and its relevance for understanding paradigms as deep leverage points in sustainability transitions. Section 3 describes the research method and outlines the development of a general worldview metamodel that provides a conceptual scaffold for comparing human–world relations across historical and cultural contexts. Section 4 elaborates the general worldview metamodel, clarifying its core components and relational structure. Section 5 presents the Wisdom Traditions Metamodel as a specialization of the general framework, articulating the triadic anthropology of heart, reason, and desire aligned with the transcendentals of the Good, the True, and the Beautiful. Section 6 introduces the Late Modernity Metamodel, developed on the basis of the general worldview metamodel. Section 7 presents a feature diagram for sustainability, identifying its essential and variable dimensions. Section 8 analyzes how different worldview configurations influence sustainability outcomes using this structured feature model. Section 9 discusses implications for sustainability practice, policy, and research, and outlines methodological approaches for operationalization and empirical validation. Finally, Section 10 concludes the paper.

2. Background and Related Work

2.1. Systems Thinking

Systems thinking is an approach that seeks to understand the world not as a collection of isolated parts, but as an interconnected web of relationships, feedbacks, and purposes [1,4,5]. It emphasizes that events rarely occur in isolation; they are shaped by broader dynamics that link cause and effect across space and time. This perspective has become increasingly important in a world marked by complexity and turbulence. Climate change, economic instability, social fragmentation, and the erosion of meaning are not random disruptions. They are symptoms of deeper forces at work—forces that cannot be addressed by piecemeal or short-term fixes [1,2,3]. Systems thinking provides a lens to see those hidden connections, to recognize patterns, and to trace problems back to their root causes. Without such a perspective, our interventions risk treating only surface symptoms, often unintentionally reinforcing the very dynamics that generate them [4,5,6,7].

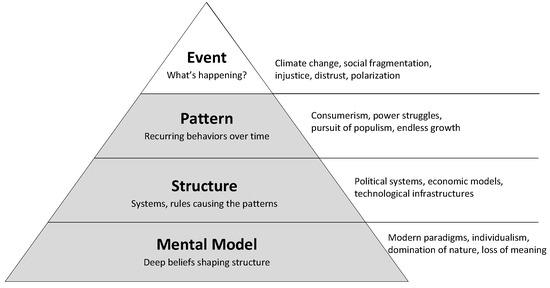

The iceberg model, as used in systems thinking, makes this logic tangible (see Figure 1). Like the visible tip of an iceberg, the events that capture headlines are only a small portion of the whole system. Beneath them lie several layers. The second layer is patterns, the recurring trends and behaviors that emerge over time. For example, repeated waves of economic inequality or polarization in public discourse show that problems are not one-time anomalies but systemic tendencies [1,2,19]. Deeper still are structures, the institutional rules, incentive systems, technological infrastructures, and social norms that produce and reinforce those patterns. At the very base are mental models: the underlying beliefs, values, and worldviews that determine how societies set goals, build structures, and interpret reality. The model suggests that while acting at the level of events may bring temporary relief, more enduring change requires shifting structures, and the deepest transformation requires reshaping the mental models that anchor a system.

Figure 1.

The iceberg model of systems thinking applied to the current time (adapted from: [1]).

Applied to the identified research questions of this article, the iceberg model highlights how the crises we face are rooted far beneath the surface. A climate disaster or social unrest (events) reflects longer-term trajectories of overconsumption, division, and alienation (patterns). These, in turn, are sustained by economic systems oriented toward growth-at-all-costs, political frameworks that privilege competition over cooperation, and media ecosystems that amplify division (structures). All of these rest on deeper mental models: the worldview of human dominance over nature, the belief in limitless progress, and the prioritization of materialism and individualism over communal or spiritual values. In this sense, the iceberg lens not only diagnoses why our problems persist but also shows where the real leverage lies: at the level of the assumptions and paradigms that silently shape the whole.

This makes systems thinking and the iceberg model both useful and necessary. They encourage us to look past surface events, to uncover hidden patterns, and to identify leverage points where change can reverberate throughout a system. They remind us that quick fixes are rarely enough and that the deepest interventions must occur at the level of mental models. Yet here lies the limitation: systems thinking can tell us that paradigms matter, but it cannot prescribe which paradigms should guide us. It offers a map of where to look, but not a compass of where to go. The iceberg helps us see that beliefs and values are decisive, but it does not tell us which beliefs and values lead to a flourishing human nature or a just civilization. To answer that normative question, we must turn beyond the iceberg to frameworks that articulate and evaluate the paradigms themselves.

2.2. Related Work

Research on worldviews, human nature and cultural formation has been developed across philosophy, sociology, psychology and sustainability science, offering conceptual foundations for the framework proposed in this study. A classical point of departure is Wilhelm Dilthey’s typology of worldviews, which classifies cultural outlooks into naturalism, the idealism of freedom and objective idealism [26]. Dilthey argued that worldviews arise from lived experience, historical context and shared cultural intuitions rather than from abstract theory alone. His analysis shows how deep anthropological assumptions shape ethical orientation, epistemic priorities and institutional structures. This supports the premise of the present work, namely that recurrent patterns in cultural development can be traced to underlying configurations of the human faculties.

Complementing Dilthey’s account, Julian Baggini’s comparative study How the World Thinks surveys major philosophical traditions and identifies characteristic modes of thought that shape cultural self-understanding across civilizations [27]. Baggini emphasizes that worldviews operate not only through explicit doctrines but also through tacit assumptions, intuitive sensibilities and habitual interpretive practices. This global perspective reinforces the value of examining worldview structures when assessing cultural responses to sustainability challenges.

Several contemporary authors have examined how Western moral thought diverged from earlier integrated frameworks. Andreas Kinneging argues that Western societies gradually moved away from classical virtue traditions grounded in an objective moral order and toward models centered on autonomy, emotivism and moral subjectivism [28]. A related critique is developed by Alasdair MacIntyre in After Virtue, where he traces the fragmentation of modern moral discourse to the erosion of classical and medieval traditions that once provided coherent teleological foundations for ethical life [29]. MacIntyre’s analysis suggests that, without shared conceptions of the good and clearly oriented desires, moral reasoning becomes procedural and emotivist. From a non-Western perspective, İbrahim Kalın’s work on Islamic philosophy highlights a parallel but distinct articulation of the human faculties. Kalın shows how the classical Islamic tradition integrates qalb (heart), aql (reason) and nafs (desire) within a unified moral and epistemic framework oriented toward truth and virtue [30]. Together, these authors show how different traditions conceptualize the ordering of human faculties and how these orders shape moral orientation and cultural development.

Charles Taylor’s historical analyses of modernity provide an important complement to these perspectives. Taylor explains how Western societies shifted into what he terms the “immanent frame,” a cultural background in which meaning and purpose are increasingly sought within the boundaries of human agency rather than transcendent orders [31,32]. This transformation altered the relationship between moral intuition, rationality and desire, helping explain why modern societies exhibit value pluralism, identity fragmentation and weakened shared moral frameworks. Zygmunt Bauman’s concept of “liquid modernity” further illuminates these dynamics. Bauman argues that contemporary life is marked by fluidity, rapid change and declining stability in moral and social structures [8]. In liquid modernity, desire becomes unbounded, identity becomes flexible and social cohesion weakens—conditions that directly affect long-term responsibility and sustainability.

Broader systems-based perspectives also contribute to understanding these patterns. Fritjof Capra and Pier Luigi Luisi argue that dominant reductionist and mechanistic worldviews have promoted fragmented understandings of knowledge, values and human purpose, whereas holistic, relational and ecological worldviews align more closely with the requirements of sustainability [4]. Within the field of sustainability transitions, Kees Klomp’s work on purpose-driven and value-based economic models emphasizes the need to move beyond growth-oriented paradigms and toward frameworks grounded in meaning, responsibility and moral purpose [33].

In sustainability science, a substantial body of empirical research has demonstrated that worldviews and values exert a strong influence on environmental attitudes and behaviors. Stern’s value–belief–norm theory identifies value orientations as foundational determinants of environmentally significant behavior [34], while Schwartz’s cross-cultural research on universal value structures provides an empirical framework for understanding these orientations [35]. Studies by de Groot and Steg show that biospheric, altruistic and egoistic value orientations correlate with distinct environmental behaviors [36]. Hedlund-de Witt highlights how underlying worldviews shape attitudes toward climate change and support for sustainability policies, demonstrating direct links between meaning systems and environmental action [37].

Environmental psychology has also contributed empirical evidence. Meta-analyses of pro-environmental behavior identify moral norms, identity constructs and motivational factors as robust predictors of sustainable action [38]. Studies in moral psychology likewise show that moral intuition, cognitive framing and perceived responsibility influence environmental choices [39].

In sustainability transitions research, socio-technical studies emphasize that shared cultural narratives and institutional logics shape the feasibility and trajectory of large-scale change [40,41]. Research on environmental ethics highlights the role of moral worldviews, notions of responsibility and conceptions of the good life in influencing policy preferences and long-term decision-making [42]. Values-based sustainability research further shows that governance structures, consumption patterns and collective action reflect deeper assumptions about human flourishing, reciprocity and intergenerational justice [43]. These literatures collectively demonstrate that sustainability challenges cannot be addressed solely through technical innovation or regulatory design; they require attention to the cultural and anthropological frameworks that orient human cognition, motivation and action.

Together, these bodies of literature form the scientific and philosophical foundation for the metamodel developed in this study. They demonstrate that the ordering of moral, cognitive and motivational faculties is widely recognized as central to cultural formation and societal outcomes, even though the specific approaches and emphases vary across disciplines. Many additional studies within philosophy, sociology, environmental psychology and sustainability science further explore these relationships and could also be referenced here. The present work contributes by synthesizing these diverse insights into a comparative metamodel that links anthropological paradigms to sustainability trajectories across historical and contemporary contexts.

To make the connection to sustainability science more explicit, the framework is anchored in empirical research on environmental values, pro-environmental behavior and socio-technical transitions. Well-established approaches such as value–belief–norm theory, identity-based models, environmental psychology and transitions research show that deeper assumptions about human nature strongly shape behavior. These insights provide empirical support for the conceptual model developed in the following sections and clarify that paradigm-level structures, although abstract, have measurable effects on sustainability outcomes.

3. Research Method

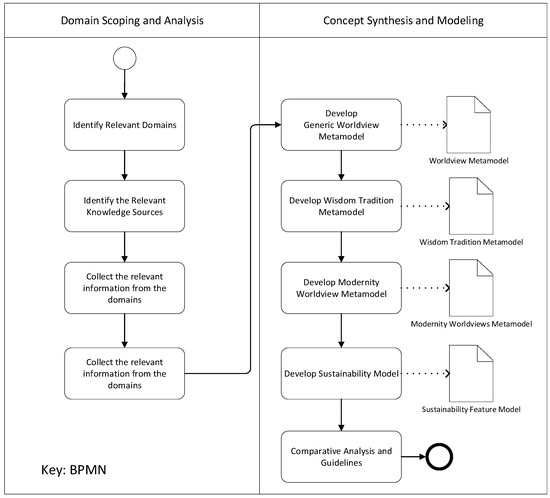

Figure 2 illustrates the methodological approach adopted in this study using the BPMN modeling notation. The methodological workflow consists of two main phases: Domain Scoping and Analysis and Concept Synthesis and Modeling [44]. Each phase contains several structured steps that together produce the metamodels developed in this study. The first phase, Domain Scoping and Analysis, structures the knowledge base by identifying the relevant conceptual and textual domains. It begins with identifying the relevant domains, which include historical, philosophical and sustainability-related bodies of knowledge. Next, the relevant knowledge sources within these domains are identified using relevance-based criteria focused on recurring constructs, anthropological patterns and sustainability implications. The selected texts are then examined to collect the relevant information, such as key concepts, faculty structures and value orientations.

Figure 2.

The adopted methodological approach.

These findings form the foundation for the synthesis phase. Domain analysis is therefore used to scope, select and organize the conceptual material that will be integrated in the subsequent modeling steps. In the second phase, Concept Synthesis and Modeling. The extracted concepts and patterns are integrated through a concept-building synthesis. These steps are described in the following.

- Development of a general worldview metamodel (RQ1, RQ2).

To compare paradigms across cultures and historical periods, it is necessary first to establish a general conceptual scaffold—a worldview metamodel—that captures the common structure underlying all interpretive systems. Rather than prescribing content, the metamodel defines the minimal set of relationships through which any worldview can be described. The general metamodel therefore abstracts from specific traditions to capture this dynamic in a way that is translatable across contexts. By remaining formally neutral, the metamodel allows diverse worldviews—spiritual, philosophical, or materialist—to be compared in a commensurable structure, preparing the ground for later specialization.

- Development of the wisdom traditions metamodel (RQ1)

Using the general scaffold, a metamodel of wisdom traditions was developed based on a comparative analysis of canonical sources from Greek, Islamic, Christian, Jewish, Hindu, Confucian, and Daoist thought. These texts were read synoptically to identify recurring constructs of human faculties, moral orientation, and ultimate ends. The coding of passages and comparison across traditions revealed convergences as well as distinctive emphases. The outcome was a wisdom traditions metamodel that expresses how these traditions frame the human person, how values are cultivated, and how worldviews are institutionalized through practices and exemplars. This provided a historically grounded model that captures enduring insights about the human condition.

- Development of the modernity and late-modernity metamodel (RQ1, RQ2).

The general metamodel was next applied to modern and late-modern thought. Philosophical and political texts from Hobbes, Locke, Rousseau, Sartre, and postmodern thinkers were examined to trace how their frameworks redefined the human person. This analysis showed how reason was narrowed to an instrumental tool, desire was legitimized or even elevated, and the moral-spiritual dimension was marginalized. The resulting metamodel of modernity and late modernity depicts how paradigms of human nature shifted away from integrated anthropologies and toward more fragmented and utilitarian accounts. Comparing this with the wisdom traditions metamodel provided a structured way to analyze paradigm drift and its broader implications.

- Linking paradigms to sustainability outcomes (RQ2)

After establishing the general and tradition-specific models, the next step is to examine how different worldview paradigms relate to sustainability outcomes. To support this analysis, a feature model is introduced to provide a structured representation of sustainability and its interrelated components. The model offers a generic lens through which diverse paradigmatic orientations can be analyzed in relation to long-term ecological, social, economic, and cultural coherence. By mapping paradigms onto this feature structure, the analysis elucidates how underlying anthropological assumptions shape sustainability trajectories. The feature model thereby serves as a bridge between abstract worldview analysis and observable sustainability configurations, offering a systematic means to trace how deep paradigms influence sustainability outcomes.

- Translation into design principles and research propositions (RQ3, RQ4)

Finally, the comparative analysis and metamodeling work were translated into practice-oriented guidelines. Normative criteria were articulated to evaluate governance, education, and organizational culture, emphasizing the alignment of values, truthfulness, and motivation. From this, a set of design principles was derived to inform sustainability practice and pedagogy. In addition, testable propositions were formulated so that the conceptual framework can be connected to empirical research in sustainability science. This ensures that the outcomes of the study are not only theoretical but also provide pathways for operationalization and future validation.

Through these five steps, the method delivers a coherent sequence: the general metamodel (Step 1) provides the conceptual scaffold; the wisdom traditions (Step 2) and modernity/late-modernity (Step 3) metamodels supply the historical content; the sustainability analysis (Step 4) reveals systemic implications; and the translation into principles and propositions (Step 5) extends the framework toward application and empirical testing.

It should be noted that the purpose of this study is to identify meta-level anthropological structures across wisdom traditions and modern formations. Therefore, the unit of synthesis is not sentences or micro-codes but conceptual constructs and their relational patterns. These criteria enhance traceability of interpretation and allow other scholars to reproduce the conceptual synthesis by applying the same sources and comparative logic.

Systematicity is ensured through structured domain scoping, explicit relevance criteria, and cross-tradition comparison, rather than through empirical coding protocols. This distinction aligns with established practice in systems thinking and metamodeling research, where abstraction rather than reduction is required.

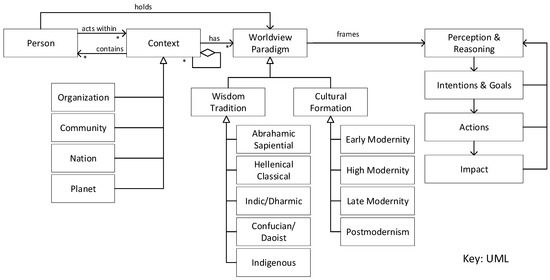

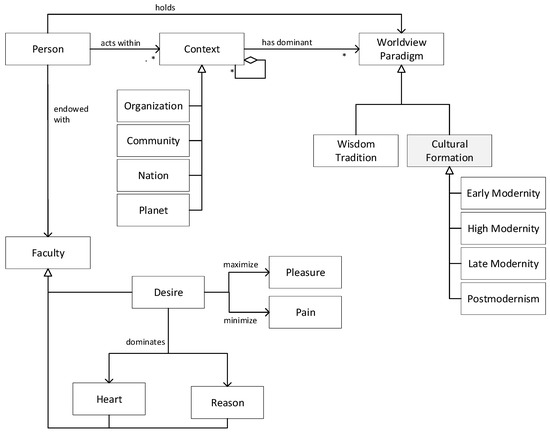

4. General Worldview Metamodel

Figure 3 presents a generic metamodel for worldviews using UML notation. Rectangles denote the identified concepts, while arrows illustrate the relationships among them. The triangle symbol indicates generalization–specialization relationships, and the diamond symbol represents part–whole (aggregation or composition) relationships.

Figure 3.

Worldview metamodel. * symbol denotes a multiplicity of zero or more elements.

The metamodel is designed to show, in one continuous picture, how persons, contexts, and meaning-giving frames interact. Persons live and act within contexts that are nested and multi-level—most immediately in organizations, more broadly in communities, and, beyond these, within nations and the planetary system. These contexts provide goals, rules, incentives, and narratives that shape attention, motivation, and judgment; at the same time, the accumulated impacts of personal and collective action can gradually reshape the very contexts in which they occur.

A context has a dominant Worldview Paradigm, understood as a transmissible orientation about reality, knowledge, value, and purpose [45,46,47]. In the metamodel, Worldview is a superclass with two analytically useful subclasses. Wisdom Traditions are sapiential lineages (for example, Sufi, Confucian, Thomistic) that carry a teleology, name and cultivate the triad of heart–reason–desire in their own lexicon, and offer practices and exemplars. Cultural Formations are modern-era families (for example, Modernity, Late Modernity, Postmodernism, Anthropocene awareness) that set background assumptions and institutional logics even when they lack an explicit program of cultivation.

A Worldview Paradigm defines a particular ordering policy for the human faculties (for example, ordered, desire-dominant, or reason-dominant), specifies the overarching system goals and their relative evaluation weights (how the Good, the True, and the Beautiful are balanced), and translates these into the rules, incentives, and information flows that shape behavior within a given context. A Wisdom Tradition typically frames perception and reasoning, which in turn shape intentions and goals that guide actions and ultimately produce impacts. Over time, feedback from observed actions and impacts can lead to adaptations in perception and reasoning, allowing the worldview to evolve while maintaining coherence between understanding, intention, and outcome.

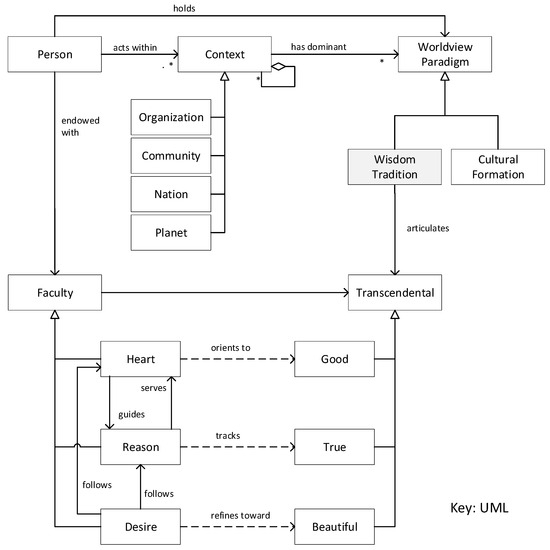

5. Wisdom Traditions Metamodel

Building upon the general worldview metamodel, this section introduces the Wisdom Traditions Metamodel as its first specialization, as shown in Figure 4. While the general model defines the structural grammar common to all worldviews, the wisdom traditions metamodel instantiates it with the content of classical civilizations—Greek, Islamic, Christian, Jewish, Hindu, Confucian, and Daoist—each articulating a coherent anthropology that orients human faculties toward moral, intellectual, and aesthetic harmony [9,10,11,12,13,22,45,47].

Figure 4.

Wisdom Tradition Metamodel as specialization of Worldview metamodel. * symbol denotes a multiplicity of zero or more elements.

To avoid misunderstanding, the triadic structure presented in this section is not proposed as a flattening of diverse traditions but as a systems-level abstraction. Each tradition contains internal diversity, historical layers, and distinct metaphysical commitments. The model therefore does not claim doctrinal uniformity; rather, it identifies a recurrent structural pattern across civilizations at the level of anthropological architecture. This type of abstraction is standard in systems thinking and metamodeling, where the aim is to highlight shared structural regularities without diminishing cultural nuance.

In this context, the Wisdom Traditions Metamodel centers on the alignment of three core human dimensions: heart, reason, and desire, which correspond to the transcendentals of the Good, the True, and the Beautiful. These faculties form the perceptual and motivational structure through which human beings engage the world. The metamodel expresses how the wisdom traditions frame this triad as an ordered system: the heart guides with moral discernment, reason discerns truth, and desire follows when refined by both. When this order holds, perception and action remain attuned to ethical and ecological balance; when it inverts, fragmentation and excess arise [15,30,46,48].

Although the metamodel identifies a recurring triadic pattern across classical civilizations, this structure is not presented as a uniform or exhaustive account of each tradition. Greek, Islamic, Christian, Jewish, Hindu, Confucian and Daoist thought contain significant internal diversity, historical development and philosophical debate. The threefold structure is therefore used as an abstracted analytical, and generic pattern that helps compare broad orientations, while the manuscript acknowledges that each tradition frames these faculties in different linguistic, metaphysical and ethical terms.

To illustrate how this structure has been expressed across civilizations, the following discussion traces how different traditions have interpreted human nature and the alignment of faculties. Across these paradigms, a shared pattern emerges: the vision of the human being as oriented toward the Good, the True, and the Beautiful (Bonum, Verum, Pulchrum). These transcendentals are not abstract ideals but deep dimensions of the self—heart, reason, and desire—whose proper ordering enables integrity, balance, and flourishing, while their distortion gives rise to fragmentation, alienation, and social decay. To appreciate this vision more fully, we can consider each of the transcendentals in turn.

The Good (Bonum) concerns our deepest sense of what is right, just, and worthy of devotion. It is accessed through the heart, which serves as the center of moral insight, sincerity, and spiritual attunement. The heart allows us to feel the weight of ethical choices, to be moved by compassion, and to act in alignment with values greater than the self. In many wisdom traditions, the heart is seen as the place where knowledge becomes conviction and where truth is translated into action. When nurtured and clear, it gives rise to discernment, humility, and integrity. When neglected or clouded, it can lead to confusion, moral compromise, and superficiality. To cultivate the heart is to engage in a deep ethical and existential task, essential for living a life of coherence and moral depth.

The True (Verum) is pursued through reason, our capacity to reflect, question, and understand. Across cultures and centuries, reason has been honored as the means through which human beings seek wisdom, truth, and coherence. It enables us to distinguish what is real from what is illusory, and what is consistent from what is contradictory. Reason is more than a mechanical calculating instrument. It offers orientation and structure, helping us align our knowledge with our values. When guided by the heart, reason serves the pursuit of truth in the service of the good. But when detached from ethical and spiritual grounding, it can become instrumental and self-serving. In such cases, facts may accumulate, information may expand, and knowledge may grow, but wisdom is lost. Only when guided by wisdom does reason bring clarity and support human flourishing.

The Beautiful (Pulchrum) awakens our longing, wonder, and capacity to be moved. It speaks to desire, which animates our actions and draws us toward fulfillment. Desire is vital, expressing our yearning for happiness, connection, creativity, and transcendence, yet it requires guidance. Aligned with truth and goodness, it becomes a force for love, beauty, and growth; left unchecked or cut off from heart and reason, it distorts judgment and breeds imbalance, excess, and conflict. Wisdom traditions teach that desire must be refined to seek what is truly beautiful, not merely pleasurable. Cultivation, in this view, is not repression but refinement: learning to love the truly beautiful, to choose well, and to live with depth and purpose. A key distinction lies between needs and desires: needs are finite and life-sustaining, bringing contentment when fulfilled, while desires are limitless, shaped by culture and ego, multiplying the more they are indulged. True wisdom affirms the fulfillment of needs while warning against unbridled desire, which without the guidance of heart and reason leads to fragmentation, dissatisfaction, and separation.

Across cultures and traditions, this triadic understanding of human nature appears in remarkably consistent forms (Table 1). In ancient Greece, Plato described the soul as composed of thymos (spirit or heart), logos (reason), and epithymia (desire or appetite). Islamic thought reflects this structure in the concepts of qalb (heart), aql (intellect), and nafs (lower self or desire). Christian thought highlights the need for harmony between spirit, mind, and body under love and divine grace. In Judaism, the triad appears as the lev (heart), the sechel/binah (intellect), and the yetzer ha-tov and yetzer ha-ra (desire). Hindu philosophy emphasizes the integration of manas (mind/heart), buddhi (intellect or discernment), and kama (desire), calling for discipline and orientation toward the highest truth. Confucian thought stresses harmony between ren (human-heartedness), zhi (moral wisdom), and yu (desire), each cultivated through virtue and right conduct. Taoist philosophy, with its focus on balance between xin (heart-mind), yi (intention or rational discernment), and yu (desire or appetite), underscores the same insight.

Table 1.

The three elements of the triadic understanding of human nature across cultures.

Despite theological and cultural differences, these traditions converge on a shared insight: human flourishing depends on the alignment of heart, reason, and desire. The heart must remain rooted in moral clarity. Reason must serve understanding rather than domination. Desire must be refined, not suppressed or left to rule. When ordered in harmony, these faculties enable integrity, wisdom, and peace. This recurring pattern suggests that true wisdom is universal.

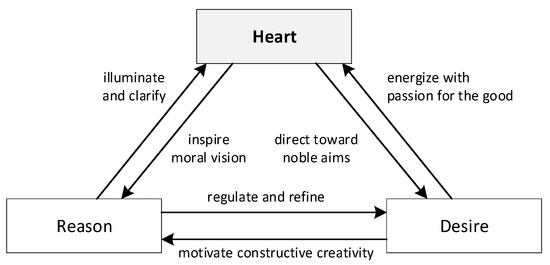

Figure 5 illustrates the ideal relational structure among the core dimensions of the human self as defined by wisdom traditions: heart, reason, and desires. In this model, the heart stands at the center as the guiding faculty, attuned to the Good and rooted in moral and spiritual clarity. Reason supports the heart by discerning what is true and by translating values into understanding, sound judgment, and thoughtful action. Desire follows, directed and refined by what the heart values and what reason clarifies. When this order is maintained, the self becomes integrated, and action flows from inner alignment. When the order is disrupted, and desires take the lead while the heart and reason are suppressed, confusion, conflict, and imbalance follow.

Figure 5.

Paradigm of Universal Wisdom traditions in which the heart guides, reason serves and desire follows.

6. Modernity and Late Modernity Metamodel

In contrast to the wisdom traditions metamodel, which emphasizes the integration and cultivation of human faculties, the modernity and late-modernity metamodel (Figure 6) depicts a profound reconfiguration of the relation between person, paradigm, context, and worldview. Using the general metamodel, this section traces how successive phases of modern thought—early modernity, high modernity, late modernity, and postmodernism—redefined human nature, reordered faculties, and introduced new paradigms that continue to shape contemporary societies and their sustainability trajectories [8,29].

Figure 6.

Late Modernity Metamodel as specialization of Worldview metamodel. * symbol denotes a multiplicity of zero or more elements.

It should be noted that modernity and late modernity are likewise not treated as monolithic entities. As scholars such as Taylor and Bauman have shown, modernity encompasses multiple and sometimes conflicting strands, including rationalist, humanist, existential, technocratic, consumerist and postmodern currents. The metamodel therefore abstracts general tendencies relevant for sustainability analysis while recognizing the complexity and heterogeneity of modern cultural formations.

- Early Modernity: Contractual Individualism and Rational Utility

The worldview of early modernity arose in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries with the breakdown of medieval synthesis and the rise of mechanistic science and political liberalism. Thinkers such as Thomas Hobbes portrayed human beings as driven by fear, self-interest, and competition. In his Leviathan (1651), life in the state of nature was “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short.” Reason was recast as a tool for survival and calculation, not for the pursuit of truth or virtue. Desire was framed as limitless appetite for pleasure and security, while the heart—the faculty of moral and spiritual discernment—was dismissed as irrational.

John Locke offered a different but complementary paradigm: the human mind as a tabula rasa, shaped by experience. For Locke, reason was empirical, pragmatic, and linked to securing property, liberty, and life. Desire was legitimized through political rights and economic freedoms. The classical hierarchy of faculties tilted: reason was narrowed, desire was expanded and protected, and the heart was marginalized.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau complicated this picture by valorizing natural goodness and authenticity of feeling. He distrusted society as corrupting and elevated inner authenticity, giving renewed weight to the heart. Yet by loosening moral structures and diminishing the guiding role of reason, Rousseau’s paradigm risked leaving desire unchecked, destabilizing earlier visions of ordered harmony.

In early modern contexts, including emerging states, growing markets, and colonial expansion, these paradigms embedded themselves in institutions of law, property, and contract. The Person was reframed as an autonomous, rights-bearing individual. Paradigms privileged survival, liberty, and property, setting the foundations for liberal democracies and market societies.

- High Modernity: Rationalism, Science, and Industrial Progress

High modernity, emerging in the Enlightenment and consolidating during industrialization, deepened these transformations. The worldview privileged rationalism, empiricism, and mechanistic science as the universal path to knowledge. Human nature was increasingly described in reductionist terms, aligned with scientific determinism and industrial utility [7,8].

In this paradigm, reason was elevated as the supreme faculty but narrowed to instrumental and calculative forms. It guided engineering, bureaucratic control, and industrial organization. Desire was legitimized through expanding markets and industrial consumption, framed as both driver and beneficiary of progress. The heart was increasingly privatized, relegated to the sphere of religion or personal life, and excluded from public rationality.

Contexts included centralized bureaucratic states, industrial economies, and colonial empires. High modernity institutionalized paradigms of progress, mastery over nature, and technocratic planning. The Person was understood as both producer and consumer, a rational planner embedded in large-scale organizations. Happiness was equated with material progress, while sustainability costs—resource depletion, exploitation, ecological degradation—were externalized.

- Late Modernity: Freedom, Consumption, and Existential Uncertainty

Late modernity, emerging in the mid-twentieth century, introduced new paradigms shaped by existentialist philosophy and global consumer capitalism. Jean-Paul Sartre and other existentialists declared that “existence precedes essence”: human beings have no fixed nature but are radically free to construct their own identity and meaning. The Person became a project of self-authorship, yet also a being burdened by anxiety and meaninglessness in a disenchanted world. The heart, as shared moral compass, was marginalized; reason provided no final answers; desire was liberated but often unmoored [49,50,51,52,53,54,55].

In parallel, neoliberal thought and consumer culture reframed freedom in economic terms. Markets and consumption became the arenas where individuals expressed identity and agency. In this neoliberal consumer paradigm, desire was no longer moderated but celebrated as the essence of freedom. Reason was instrumentalized to optimize markets and choices, while the heart was displaced as subjective sentiment.

Contexts included global markets, mass media, and transnational corporations. Institutions promoted short-term gain, competition, and consumption as the engines of prosperity. The late-modern Person was cast primarily as a consumer, free to choose but structurally dependent on systems that encouraged limitless appetite. This reinforced feedback loops of ecological overshoot, social inequality, and cultural fragmentation.

- Postmodernism: Skepticism, Relativism, and Fragmentation

Postmodernism pushed late-modern tendencies further by questioning the very idea of a unified self, universal truth, or shared moral foundation. Knowledge was treated as contingent and constructed; grand narratives were distrusted. The Worldview became plural, fragmented, and ironic [56,57].

Under this paradigm, reason lost its claim to universality and coherence. The heart was reframed as one subjective preference among many, no longer anchored in transcendent values. Desire was proliferated through consumerism, digital culture, and identity politics, often fragmented into niche markets and lifestyles.

Contexts reflected this fragmentation: globalized media, virtual networks, and liquid institutions. The Person was understood as decentered, flexible, and performative—able to adopt multiple identities but lacking stable orientation. Happiness was redefined in terms of experiences, consumption, and expression rather than coherence or depth.

These paradigms manifest in Contexts such as market economies, nation-states, bureaucratic institutions, and global consumer culture. They reinforce the dominant worldview by embedding competition, consumption, and autonomy into rules, incentives, and expectations. Educational systems increasingly reward instrumental reasoning and individual performance, while economic systems encourage limitless desire and short-term gain. Feedback loops stabilize these formations: everyday practices of consumption and competition reinforce the cultural assumptions that legitimize them, making paradigm drift self-reinforcing.

At the center of this model, the Person is reframed. No longer primarily a moral and spiritual agent to be cultivated, the modern individual is often conceived as a rational optimizer or autonomous self. In late modernity, this image fractures further: the self becomes radically free yet burdened with existential uncertainty, or fragmented under postmodern critique. Desire, far from being refined, is equated with authenticity and celebrated as freedom. Reason is reduced to an instrument of efficiency and control. The heart, once seen as the seat of moral discernment and spiritual orientation, is marginalized as subjective or irrelevant.

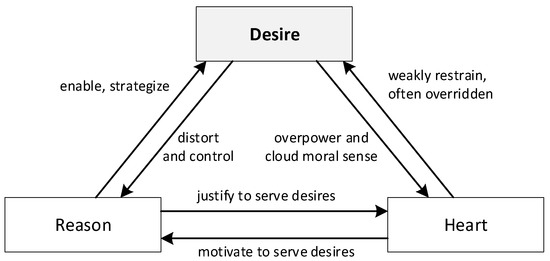

The modernity and late-modernity metamodel thus depicts a paradigmatic inversion relative to the wisdom traditions (Figure 7). Where earlier worldviews sought harmony among faculties, modern and late-modern formations often privilege desire, instrumentalize reason, and marginalize the heart. This reconfiguration has profound implications for sustainability. It legitimizes cultures of consumerism, justifies the pursuit of endless growth, and fragments communal bonds. It also redefines happiness itself, shifting from inner coherence and moral depth to the pursuit of pleasure, material success, and consumption. Needs, which are finite, are blurred with desires, which are boundless—fueling ecological overshoot and social fragmentation.

Figure 7.

Paradigm of Late Modernity in which desire dominates over reason and heart.

As stated before, in wisdom traditions, the triad is ordered: the heart (moral salience and sincerity) guides, reason serves, and desire is refined; the Good, True, and Beautiful operate as joint guardrails—none may be pursued while another falls below a viability threshold. By contrast, Early Modernity (Enlightenment/early industrial) makes reason ascendant: truth is secured by method and coherence (scientific realism), the good is cast as progress, rights, and universal duty, and desire is disciplined toward productivity; beauty is classical proportion shading into the romantic sublime. High Modernism intensifies this into technocratic reason: optimization, metrics, and standardization “see like a state”; the good becomes efficiency-plus-welfare, truth is what is measured, desire is managed/standardized, and beauty collapses into functionalism—yielding large-scale externalities when metrics miss what matters. Late Modernity inverts the stack: desire becomes the goal-setter (consumer sovereignty, lifestyle identity), reason turns instrumental (analytics to optimize markets), and the heart retreats to the private; the good reduces to preference satisfaction and growth, truth to performance signals/prices, beauty to spectacle/branding—driving overshoot, rebound effects, and inequality. Postmodernism then de-centers truth claims, pluralizing narratives and fragmenting shared standards; the heart becomes expressive/emotivist, desire is aestheticized/playful, the good is contextual/negotiated, and beauty is remix/pastiche—sharp for critique yet often weak for coordination. In short, where wisdom paradigms aim at integrated ordering under Good–True–Beautiful as joint constraints, modern formations oscillate between reason-dominant (early/high), desire-dominant (late), and truth-decentered (postmodern) regimes—each producing characteristic sustainability failures that the wisdom ordering was designed to prevent.

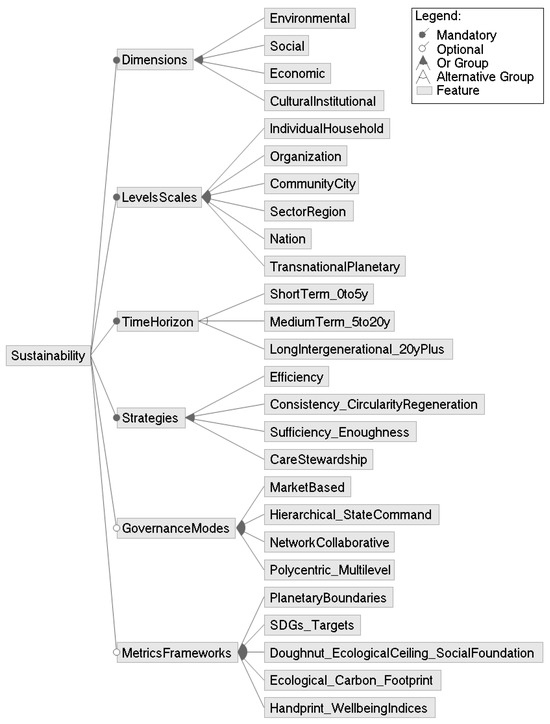

7. Sustainability Feature Model

To compare how different paradigms of human nature shape sustainability, it is necessary to define sustainability itself in a structured way. In this study, sustainability is modeled through a feature diagram (Figure 8). This approach captures its essential components—dimensions, levels, time horizons, strategies, governance modes, and metrics—while also showing where variation and alternatives exist. The result is a representation that allows different paradigms to be systematically assessed against the same model.

Figure 8.

Sustainability Feature Model.

Sustainability is treated here as a normative systems goal: to maintain and enhance the integrity of coupled social–ecological systems so that present and future generations can flourish within ecological limits. This definition highlights three critical implications. First, sustainability is intergenerational, requiring that current choices not compromise the options of those who follow. Second, it is precautionary, demanding caution in the face of uncertainty and irreversibility. Third, it requires alignment of human provisioning systems with the planetary boundaries that define safe operating space for humanity.

The feature diagram distinguishes several mandatory dimensions:

- Environmental: safeguarding climate stability, biodiversity, and the integrity of land, water, and atmospheric systems. This is the biophysical foundation without which other dimensions collapse.

- Social: fostering wellbeing, justice, equity, inclusion, and social cohesion. Sustainability is not only ecological but also relational, depending on resilient and fair communities.

- Economic: ensuring livelihoods, resilient value chains, and provisioning systems that operate within ecological limits. Economic vitality must be compatible with long-term ecological and social integrity.

- Cultural–Institutional: capturing the values, norms, governance capacity, and trust that stabilize the other three. This dimension ensures that sustainability is not just a technical balance but a moral and cultural project.

Sustainability also operates across multiple levels and scales. These range from individuals and households to organizations, communities and cities, regions and sectors, nations, and ultimately the planetary system. Each level introduces unique challenges and opportunities, and feedback across levels can amplify or undermine sustainability efforts. For example, household consumption choices accumulate into global ecological pressures, while global treaties constrain or enable local practices.

Time horizons are equally crucial. The diagram distinguishes short-term (up to 5 years), medium-term (5–20 years), and long-term or intergenerational (20+ years). Many sustainability problems arise because short-term gains undermine long-term viability, reflecting the tension between immediate incentives and enduring responsibility.

The model also identifies alternative strategies toward sustainability. Efficiency focuses on “doing more with less” through technological or organizational innovation. Consistency emphasizes circularity and regenerative alignment with natural cycles. Sufficiency stresses moderation, restraint, and the cultivation of “enoughness,” resisting pressures for endless consumption. Finally, care or stewardship introduces an explicitly ethical stance: the recognition of responsibility for others, for nature, and for future generations. These strategies are not mutually exclusive, but paradigms of human nature influence which are emphasized.

Optional governance modes further shape sustainability pathways. These include market-based systems that rely on price signals and competition; hierarchical state or command structures; network-based collaboration across actors; and polycentric governance that coordinates across levels and institutions. Which mode is privileged depends in part on the underlying paradigm: a market-oriented paradigm may elevate competition and efficiency, while a stewardship-oriented paradigm may favor collaboration and care.

Finally, the feature diagram recognizes multiple metrics and frameworks for assessing progress. These include the planetary boundaries framework, the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), doughnut economics, ecological and carbon footprints, and wellbeing or “handprint” indices. Each metric emphasizes different priorities, and their adoption often reflects deeper paradigmatic assumptions about what should be measured and valued.

Taken together, this sustainability feature model provides a structured architecture that makes the link between paradigms and outcomes explicit. Paradigms influence which dimensions are prioritized, which scales and horizons are emphasized, which strategies dominate, which governance modes are legitimized, and which metrics are used to judge success. In the next section, the wisdom traditions metamodel and the modernity/late-modernity metamodel will be systematically mapped onto this sustainability model, clarifying how divergent anthropological assumptions generate contrasting ecological, social, and cultural outcomes.

8. Paradigms and Sustainability Outcomes

The sustainability feature model provides a structured lens for evaluating how different paradigms of human nature translate into ecological, social, and cultural outcomes. By mapping the wisdom traditions metamodel and the modernity/late-modernity metamodel onto this model, key contrasts emerge across the core features of sustainability.

- Dimensions

Wisdom traditions emphasize moral responsibility toward all dimensions of sustainability. The environmental domain is grounded in stewardship and reverence for creation, emphasizing care and restraint. The social dimension is expressed through solidarity, justice, and mutual responsibility. The economic dimension is framed not as accumulation but as provisioning for needs, balanced by moderation. The cultural–institutional dimension is central: rituals, virtues, and narratives provide continuity and orientation across generations. By contrast, modern and late-modern paradigms privilege the economic dimension, treating growth and consumption as primary goals. The environmental dimension is often subordinated to human control, while the social dimension is fragmented by individualism and competition. Cultural–institutional stability is weakened, as shared moral frameworks give way to pluralism and relativism.

- Levels and scales

In wisdom traditions, sustainability is pursued through nested scales, from household ethics to cosmic harmony. The household, community, and polity are seen as microcosms of a larger order, with responsibilities extending outward to humanity and nature as a whole. By contrast, modern and late-modern paradigms often elevate the individual and the market as primary sites of action, while broader scales are managed through abstract institutions such as the state or global markets. This creates disjunctures: local responsibilities are weakened, and global consequences accumulate without adequate governance.

- Time horizons

Wisdom traditions emphasize long-term and intergenerational horizons, often invoking eternity, lineage, or cosmic cycles. Practices such as restraint, cultivation, and stewardship are designed to preserve continuity across generations. Modernity and late modernity, by contrast, tilt toward short- and medium-term horizons: electoral cycles, quarterly returns, and immediate consumer satisfaction. The result is discounting of the future, a key driver of ecological overshoot and social instability.

- Strategies

Wisdom traditions typically stress sufficiency and care/stewardship. Efficiency and consistency are present but embedded within a larger ethical framework that constrains excess and orients action toward the common good. By contrast, modern and late-modern paradigms elevate efficiency as the dominant strategy, often in service of unbounded desire. Consistency is selectively applied (e.g., circular economy initiatives), but sufficiency and care are marginalized as “anti-progressive” or “restrictive.” This imbalance helps explain why technical innovations alone have not delivered sustainability transitions: efficiency without sufficiency leads to rebound effects.

- Governance modes

Wisdom traditions lean toward networked and polycentric governance, rooted in communal deliberation, moral authority, and shared norms. Authority is often distributed across family, community, and spiritual institutions, creating resilience through redundancy. Modernity and late modernity, by contrast, privilege market-based and hierarchical governance. Markets allocate resources through price, while states enforce rules to secure competition and growth. Collaborative and polycentric modes are present but often secondary, emerging only in response to crises.

- Metrics and frameworks

Wisdom traditions evaluate outcomes through moral and spiritual criteria—virtue, justice, harmony, beauty—rather than quantitative metrics. These qualitative standards encourage alignment with transcendent values. Modernity and late modernity, by contrast, privilege quantitative metrics such as GDP, productivity, or consumption indicators. Even when sustainability frameworks such as the SDGs or ecological footprints are adopted, they are often interpreted within growth-oriented paradigms, limiting their transformative potential.

Table 2 shows the summary of the analysis of sustainability features for the wisdom traditions vs. modernity paradigm. Taken together, the comparison shows that wisdom traditions align closely with the full feature set of sustainability: they integrate environmental, social, economic, and cultural dimensions; work across scales and horizons; emphasize sufficiency and care; and embed governance in moral and communal frameworks. Modern and late-modern paradigms, by contrast, narrow sustainability to economic growth, short-term horizons, efficiency-driven strategies, and market/hierarchical governance. This narrowing helps explain persistent lock-ins and rebound effects: the paradigm itself is misaligned with the goal of sustainability.

Table 2.

Summary of sustainability evaluation for Wisdom Tradition vs. Modernity Paradigm.

Thus, the mapping makes clear that sustainability outcomes are not simply the result of technical or institutional factors but are deeply rooted in paradigms of human nature. Addressing crises at the level of events or structures is insufficient unless the paradigmatic assumptions guiding perception, motivation, and judgment are reconsidered.

9. Discussion

9.1. Synthesis of Findings

This study set out to explore how paradigms of human nature influence the ways societies define and pursue sustainability. The analysis shows that sustainability challenges are not only technical or institutional but arise from deeper anthropological assumptions—how human faculties are understood, ordered, and cultivated. By comparing wisdom traditions with modern and late-modern frameworks through the proposed metamodel, several key insights emerge.

First, the triadic anthropology of heart, reason, and desire, aligned respectively with the Good, the True, and the Beautiful, provides a coherent structure for comparing worldviews across time and culture. In wisdom traditions, this triad is ordered and integrated: the heart guides with moral discernment, reason serves by seeking truth, and desire follows when refined by both. This configuration generates coherence between ethical intention, intellectual clarity, and motivation, fostering harmony between human flourishing and the larger ecological and social order.

Second, the modern and late-modern formations reveal progressive reconfigurations of this triad. Early and High Modernity elevated reason to dominance but restricted it to instrumental calculation. Late Modernity placed desire at the center, equating freedom with choice and fulfillment with consumption, while the heart was relegated to private sentiment. Postmodernity further fragmented coherence by questioning universal truths and shared moral reference points. These successive shifts help explain the move from stewardship to control, from balance to excess, and from meaning to disorientation.

Third, these anthropological transformations are reflected in corresponding cultural and institutional patterns. Wisdom traditions emphasize cultivation—education of the heart, refinement of desire, and discipline of reason—whereas modern paradigms emphasize production, optimization, and expansion. The resulting institutions, values, and aspirations tend to mirror the prevailing ordering of the faculties: when desire dominates, societies valorize consumption and competition; when reason dominates, they privilege control and efficiency; when the heart leads, they orient toward care, truth, and sufficiency.

Overall, the findings indicate that the roots of sustainability lie not primarily in external technologies or policies but in the internal architecture of human understanding. Re-aligning heart, reason, and desire is therefore not a nostalgic return to the past but a forward-looking act of integration—a renewal of moral, intellectual, and motivational balance that can provide the cultural foundation for genuine and lasting sustainability.

9.2. Implications for Sustainability Practice and Policy

The results carry direct implications for sustainability design, governance, and culture. If sustainability crises originate in paradigmatic inversions, then durable transitions require reconfiguring the underlying WorldviewParadigm (WP) that guides how institutions define success, allocate incentives, and interpret knowledge. The metamodel suggests several directions for transformation.

- Design for guardrails, not only goals

Sustainability practice often focuses on measurable targets such as emissions or economic output, yet systems collapse when goals are pursued without normative thresholds. The Good, the True, and the Beautiful can function as conceptual guardrails—moral, epistemic, and aesthetic constraints that prevent over-optimization in any single domain. For example, economic growth should not advance if justice (Good) or truth quality (True) falls below a viability threshold. Embedding such multidimensional guardrails into policy design helps avoid rebound effects and moral blind spots.

- Move leverage upstream

Interventions at the structural layer—rules, norms, incentives, and information quality—have far more lasting impact than event-level adjustments. Governance reforms should therefore begin by diagnosing which WP is implicitly shaping current structures. For instance, market-based systems often embed a desire-dominant WP, whereas community-oriented systems reflect a heart-guided or wisdom-oriented WP. Making the implicit paradigm explicit allows policymakers to re-align institutional design with the intended ordering of values.

- Re-center the heart as moral salience, not sentimentality

Re-centering the heart does not imply emotionalism but the cultivation of sincerity, empathy, and ethical attentiveness within collective decision-making. Institutional structures that enhance moral salience include transparency mechanisms that reveal externalized harms, participatory processes for setting thresholds, and accountability systems that protect dignity rather than image. In organizations, moral salience can be strengthened through leadership development, narrative framing, and ethical reflection practices.

- Strengthen epistemic quality and truth calibration

The “True” dimension concerns the integrity of information flows and the ability to learn from error. Sustainability governance must ensure independent measurement, transparent uncertainty disclosure, and incentives that reward correction rather than performance theater. This entails redesigning scientific advisory systems, integrating epistemic humility into decision protocols, and aligning metrics with meaningful outcomes rather than superficial indicators.

- Refine rather than repress desire

Desire is not the enemy of sustainability but its potential energy. When refined through education, culture, and aesthetics, desire motivates stewardship rather than consumption. Policy can influence preference formation through product standards, advertising regulation, public aesthetics, and education for sufficiency. The goal is not asceticism but alignment—lives that are materially sufficient and emotionally fulfilling within planetary boundaries.

- Foster coherence across scales of governance

Because contexts are nested (organization → community → nation → planet), interventions at one level must remain coherent with those above and below. The same WP can be traced through these levels to detect contradictions—for example, when national policies promote efficiency but local communities practice sufficiency. Polycentric and reflexive governance models are best suited to sustain such coherence, balancing autonomy with shared purpose.

- Integrate wisdom into institutional learning

Finally, the model suggests that sustainability governance should include reflexive loops for learning not only from data but from ethical and experiential insight. This implies institutional mechanisms that combine empirical evaluation with deliberation on values, virtues, and meaning—reconnecting the procedural rationality of modern institutions with the moral wisdom of cultural traditions.

Taken together, these implications propose a practical synthesis: sustainability transitions must be both structural and sapiential. Technical innovation, regulation, and market mechanisms remain necessary but insufficient without a parallel re-ordering of human faculties and values. Durable transformation emerges when the heart regains its guiding role, reason serves truth rather than power, and desire becomes oriented toward care, beauty, and sufficiency.

9.3. Threats to Validity

While this study offers a new integrative framework for understanding the relationship between paradigms of human nature and sustainability outcomes, several considerations qualify the scope of its claims and point toward opportunities for future refinement.

- Conceptual abstraction and ideal-typical representation

The worldviews and cultural formations discussed are presented as ideal types to clarify underlying anthropological structures and causal patterns. Real contexts, however, display hybrid and evolving configurations—modern institutions often preserve traces of older moral frameworks, while traditional communities adopt modern reasoning and technologies. This conceptual abstraction strengthens theoretical clarity and comparability, though it limits direct empirical generalization. Future work can build on this foundation through comparative case studies that test how ideal-typical patterns manifest in contemporary organizations, policies, and cultures.

- Normative explicitness and evaluative coherence.

The framework intentionally integrates normative assumptions by treating the Good, the True, and the Beautiful as evaluative anchors for human development and sustainability. This transparency enhances the model’s interpretive power by making value trade-offs explicit rather than implicit. Still, it may not align with all philosophical or cultural perspectives. Subsequent research can explore pluralistic adaptations of the model—testing its robustness under alternative value systems (e.g., justice, wellbeing, harmony)—to assess its universality and intercultural applicability.

- Temporal and cultural breadth

Covering wisdom traditions and modern formations across millennia and cultures introduces a challenge of contextual generalization. The synthesis emphasizes broad philosophical trajectories rather than exhaustive ethnographic accuracy. Nevertheless, this cross-historical scope is also a strength: it reveals structural recurrences and anthropological constants that might otherwise remain hidden. Future studies can enrich this dimension by examining non-Western modernities or indigenous frameworks that may embody alternative yet complementary anthropological orderings.

- Empirical operationalization and measurement

As a concept-building effort, the model prioritizes theoretical integration, but it also lays a clear pathway for empirical testing. Proposed instruments such as the Triadic Balance Index (TBI) and WorldviewParadigm inference approach can be further developed through psychometric validation, text analysis, and longitudinal data. These tools will enable systematic evaluation of how moral, epistemic, and motivational coherence relate to sustainability performance in organizations and communities.

- Reflexivity and interdisciplinary integration

Because the framework unites insights from systems science, philosophy, and comparative traditions, the researcher’s interpretive lens inevitably shapes synthesis and emphasis. This reflexivity is acknowledged not as a weakness but as an asset of integrative scholarship, demonstrating how diverse epistemic traditions can converge on shared insights about human flourishing and sustainability. Future collaborations across disciplines and cultures can further enhance both the depth and the inclusivity of the model.

In summary, these considerations highlight not only the boundaries but also the evolutionary potential of the proposed metamodel. Its strength lies in offering a coherent, value-explicit, and transdisciplinary foundation for linking human anthropology to sustainability outcomes. Far from being a limitation, its openness to empirical testing, intercultural dialogue, and iterative refinement ensures that the model can grow into a robust platform for both theoretical advancement and practical application in sustainability research and policy.

10. Conclusions

This study examined how paradigms of human nature influence sustainability outcomes by shaping the way societies define progress, knowledge, and responsibility. The comparative metamodel developed here demonstrates that each historical framework, whether derived from wisdom traditions or modern formations, reflects a distinct ordering of the human faculties of heart, reason, and desire. This ordering determines how values are prioritized, how institutions are designed, and how human–environment relations are understood.

The analysis indicates that enduring sustainability depends on the alignment of moral discernment, intellectual coherence, and motivated action. In wisdom traditions, this alignment results in an integrated anthropology where ethical insight, truthful knowledge, and refined aspiration reinforce one another, leading to a balance between human development and ecological integrity. Modern and late-modern paradigms, while driving scientific and technological progress, often separate these dimensions, emphasizing instrumental reasoning and individual preference over moral and communal coherence.

The study contributes to sustainability research by providing a conceptual metamodel that connects anthropological assumptions to societal outcomes. It highlights that the success or failure of sustainability initiatives cannot be understood solely in terms of technical solutions or governance mechanisms, but must also consider the underlying paradigm that defines what counts as knowledge, value, and progress. The framework offers a basis for interdisciplinary inquiry into how moral, epistemic, and motivational integration influence collective behavior and long-term resilience.

Future research should put this framework into practice by developing measurable indicators that capture how heart, reason and desire are ordered within individuals, institutions and cultures. With such indicators, comparative studies across sectors and societies could examine how different configurations of these faculties relate to sustainability outcomes. To achieve this, the triadic model needs to be translated into observable variables at the individual, organizational and societal levels. This may include textual and discourse analyses that reveal underlying value orientations; psychometric or behavioral measures that indicate motivational patterns; and institutional coding schemes that assess whether organizational practices align with declared values. Creating such indicators is urgent because they would make it possible to empirically compare how different anthropological paradigms influence sustainability-related behaviors, policy choices and systemic dynamics. Relevant indicators may span economic domains (such as consumption patterns and incentive structures), social domains (such as cohesion, trust and value alignment), environmental domains (such as ecological footprint and resource efficiency) and cultural domains (such as shared narratives and ethical orientation).

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Meadows, D.H. Thinking in Systems: A Primer; Chelsea Green: White River Junction, VT, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Raworth, K. Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st-Century Economist; Cornerstone: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hickel, J. Less Is More: How Degrowth Will Save the World; William Heinemann: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Capra, F.; Luisi, P.L. The Systems View of Life: A Unifying Vision; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Capra, F. The Web of Life: A New Scientific Understanding of Living Systems; Anchor Books: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Klomp, K. Ecoliberalisme: Een Veranderverhaal over Ware Vrijheid; Business Contact: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher, E.F. Small Is Beautiful: Economics as if People Mattered; Harper Perennial: New York, NY, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Bauman, Z. Liquid Modernity; Polity: Cambridge, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Habermas, J. The Philosophical Discourse of Modernity; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Heidegger, M. Being and Time; Harper & Row: New York, NY, USA, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Plato. The Republic; Bloom, A., Translator; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Confucius. The Analects; Waley, A., Translator; Vintage: New York, NY, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Chittick, W.C. The Sufi Path of Knowledge: Ibn al-‘Arabi’s Metaphysics of Imagination; SUNY Press: Albany, NY, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Can, Ş. Fundamentals of Rumi’s Thought: A Mevlevi Sufi Perspective; The Light: Trenton, NJ, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Kalın, İ. Açık Ufuk: İyi, Doğru ve Güzel Düşünme Üzerine; İnsan Yayınları: İstanbul, Turkey, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong, K. Sacred Nature: How We Can Recover Our Bond with the Natural World; Knopf: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Berry, T. The Great Work: Our Way into the Future; Bell Tower: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Fromm, E. To Have or To Be? Harper & Row: New York, NY, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam, R.D. Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community; Simon & Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Sandel, M.J. What Money Can’t Buy: The Moral Limits of Markets; Farrar, Straus and Giroux: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Wilber, K. A Brief History of Everything; Shambhala: Boston, MA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Jonas, H. The Imperative of Responsibility: In Search of an Ethics for the Technological Age; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Næss, A. Ecology, Community and Lifestyle; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Schimmel, A. Mystical Dimensions of Islam; University of North Carolina Press: Chapel Hill, NC, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Latour, B. We Have Never Been Modern; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Dilthey, W. The Types of World-View and Their Development in Metaphysical Systems. In Selected Works, Volume VI: The Formation of the Historical World in the Human Sciences; Makkreel, R.A., Rodi, F., Eds.; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 249–293. [Google Scholar]

- Baggini, J. How the World Thinks: A Global History of Philosophy; Granta Publications: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kinneging, A.A. Geography of Good and Evil; ISI Books: Wilmington, DE, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- MacIntyre, A. After Virtue: A Study in Moral Theory, 3rd ed.; University of Notre Dame Press: Notre Dame, IN, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Kalın, I. Reason and Rationality in the Qur’an; SETA: Ankara, Turkey, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, C. A Secular Age; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, C. Sources of the Self: The Making of the Modern Identity; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Klomp, K.; Oosterwaal, S. Thrive: Fundamentals for a New Economy; The Thrive Institute: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Stern, P.C. New Environmental Theories: Toward a coherent theory of environmentally significant behavior. J. Soc. Issues 2000, 56, 407–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]