Abstract

Substrate amendment is a promising strategy to enhance phytoremediation in degraded coastal wetlands, yet the selection of optimal materials and their incorporation ratios remains challenging. This study systematically investigated the effects of five amendments, viz., manganese sand, maifan stone, bentonite, iron–carbon (Fe-C), and vermiculite, across an incorporation ratio gradient (5–40%) on the growth of the mangrove, Kandelia obovata, and the physicochemical properties of coastal wetland substrate. Results demonstrated material-specific and dose-dependent responses. Four amendments (vermiculite, Fe-C, manganese sand, and maifan stone) promoted Kandelia obovata growth to varying degrees, while bentonite exhibited significant inhibition. All amendments ensured the physical stability of the substrate. Nutrient removal efficiency followed the order: Fe-C > vermiculite > maifan stone > manganese sand, with 10% Fe-C showing the highest comprehensive nutrient removal. Conversely, bentonite functioned as a nutrient enrichment agent. The amendments differentially influenced redox potential, CO2 emissions, and electrical conductivity, yet all maintained a stable substrate pH. A comprehensive evaluation considering plant growth, nutrient removal, and CO2 sequestration identified maifan stone as the optimal amendment, with the 40% incorporation ratio delivering the most favorable integrated performance. This study provides critical, ratio-specific guidance for selecting and applying substrate amendments in coastal wetland restoration. This study provides critical, ratio-specific guidance for selecting and applying environmentally sustainable amendments, supporting the development of nature-based solutions for long-term coastal wetland restoration.

1. Introduction

Coastal wetlands, as critical ecotones at the land–sea interface, are among the most productive and biodiverse ecosystems on Earth. They deliver indispensable ecological functions, including water purification, storm surge buffering, substantial carbon sequestration (“blue carbon”), and biodiversity maintenance [1,2,3]. However, rapid socioeconomic development, industrialization, and urbanization have led to widespread degradation of these vital ecosystems globally [4,5,6]. Multiple stressors, including land reclamation, salinity intrusion, invasive species, and eutrophication, have severely impaired coastal wetlands [7,8]. The restoration of these degraded systems is inherently complex and challenging, posing a significant worldwide problem. In the context of rapid economic development and climate change, there is a pressing global need to develop effective restoration strategies that enhance nitrogen removal and carbon sequestration to maximize their blue carbon potential.

Current ecological restoration technologies for coastal wetlands primarily encompass physical, chemical, and biological approaches [9,10,11,12]. Physical methods, such as soil replacement and dredging, are often engineering-intensive, costly, and can disrupt the native habitat. Chemical methods, including the addition of passivators and pH regulators, are fast-acting but risk introducing secondary pollution and often lack long-term efficacy. In contrast, phytoremediation—a plant-based biological approach—is widely recognized as the most promising pathway due to its environmental friendliness, cost-effectiveness, and ability to restore ecosystem structure and function [13,14,15]. The cultivation of salt- and pollution-tolerant wetland plants (e.g., Phragmites australis, Suaeda salsa, mangroves) can directly uptake, accumulate, or degrade pollutants [16,17,18,19,20,21,22]. Furthermore, root activity can improve substrate physicochemical properties and stimulate microbial community recovery, facilitating positive ecosystem succession [23,24].

Nevertheless, the successful application of phytoremediation in coastal wetlands is severely constrained by the hostile substrate environment. Prevalent issues, including high salinity, imbalanced pH (often acidic or strongly alkaline), nutrient deficiency, and contaminant toxicity, significantly hinder seed germination, seedling establishment, and root development [25]. These adverse conditions lead to low phytoremediation efficiency and frequent failure. Therefore, the in situ amendment of unsuitable coastal substrates to create a favorable “micro-environment (the complex and dynamic physicochemical and biological conditions in the immediate vicinity of the plant roots)” for plant growth is a critical step to overcoming the technical bottlenecks of phytoremediation and enhancing the overall effectiveness of ecological restoration.

Kandelia obovata, a pioneer mangrove species, is a logical candidate for restoration in regions such as Wenzhou Bay in China [26,27,28,29]. Kandelia obovata delivers vital ecosystem services, including coastal stabilization, water purification, and habitat provision. Its ecological roles encompass shoreline defense and the transformation of pollutants into nutrients. Yet, its potential is often unrealized in degraded substrates without intervention. Substrate amendment involves incorporating materials to improve the physical, chemical, and biological properties of the native soil [30,31]. A wide range of materials, such as biochar and compost, has been explored for this purpose [32,33,34,35]. However, there is a lack of systematic comparison of the synergistic restoration efficiency of different properties of improved materials with mangroves under wide gradient ratios, which seriously restricts the selection and precise deployment of materials in restoration practice.

This study focuses on five distinct amendment materials: Maifan stone, vermiculite, and bentonite as mineral adsorbents, and manganese sand and iron–carbon material as functional amendments. Maifan stone is a natural mineral complex, also known as refined mountain stone, horse tooth sand, or soybean residue stone. Maifan stone is a composite mineral that is non-toxic, harmless, and has certain biological activity. It is known for its porosity and ability to release beneficial trace elements. The main chemical component of maifan stone is inorganic aluminosilicate [36]. Vermiculite and bentonite are excellent at improving water retention and cation exchange capacity, thereby potentially enhancing nutrient availability [37,38]. Vermiculite was chosen for its exceptionally high cation exchange capacity (CEC) and unique exfoliation property upon hydration, which creates a stable, porous structure that enhances both water retention and aeration—a critical combination in waterlogged wetland sediments where root oxygenation is often limiting. Bentonite (primarily composed of montmorillonite) was selected for its high swelling capacity and very high CEC, which not only improves water retention but also effectively stabilizes soil structure and immobilizes cationic contaminants through adsorption. Manganese sand (a natural material, manganese sand content of 30%), often used in filtration, can influence microbial processes involved in nutrient cycling [39]. The iron–carbon material, a product of micro-electrolysis, is hypothesized to facilitate contaminant degradation and alter nutrient dynamics through its redox activity [40].

While the benefits of the amendment are clear, a critical knowledge gap persists regarding the optimal type and, more importantly, the optimal incorporation ratio of these materials. An insufficient amount may yield no measurable benefit, while an excessive ratio could alter the substrate properties detrimentally, potentially inhibiting plant growth or causing economic inefficiency. A systematic comparison of different materials across a wide gradient of mixing ratios is necessary to identify the most effective combination for synergistic eco-remediation with mangroves.

To address this gap, we conducted a pot experiment using degraded coastal substrate from Wenzhou Bay. The primary objectives of this study were: (1) to evaluate the effects of five different amendment materials (Maifan stone, vermiculite, bentonite, manganese sand, and iron–carbon) at varying incorporation ratios (5% to 40%) on the growth performance of Kandelia obovata; and (2) to investigate the concomitant changes in key substrate chemical properties, specifically nitrogen and phosphorus levels.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals

Supplementary Table S1 shows the information on the chemicals used in this study. All chemicals were used as received, and all solutions were prepared using deionized water (18.2 MΩ cm).

2.2. Experiment of Substrate Amendment Combined with Kandelia obovata Plantation

Five amendment materials, viz., manganese sand, maifan stone, bentonite, iron–carbon, and vermiculite, were selected to enhance and restore coastal wetland sediment. The mangrove species, Kandelia obovata, was employed as the indicator vegetation. Sediment samples were collected from a coastal wetland located in Ersha Village, Pingyang County, Wenzhou City, Zhejiang Province, China. A simulated seawater solution (30 g sea salt: 1 L deionized water), formulated to replicate natural seawater chemistry, was used throughout the study. A mesocosm system integrating the water body, coastal wetland sediment, amendments, and vegetation was established under controlled laboratory conditions.

Each of the amendment materials was thoroughly mixed with the wetland sediment at four distinct mass ratios: 5%, 10%, 30%, and 40%. The proportion of 30% and 40% is intended to simulate scenarios that require high load improvement (such as polluted hotspot areas), while 5% and 10% correspond to general remediation needs. All treatments were performed in triplicate to ensure statistical reliability. After an overnight stabilization period to allow initial sediment-amendment equilibrium, uniform seedlings of Kandelia obovata were transplanted into the respective mesocosms to initiate the restoration experiment (Figure S1). After planting Kandelia obovata, its growth and substrate properties were monitored every week.

2.3. Analytical Methods

Total potassium (TK) content was determined by the potassium tetraphenylborate gravimetric method. Total phosphorus (TP) and total nitrogen (TN) were determined by spectrophotometry. The particle size distribution of the samples was characterized using a laser diffraction particle size analyzer (Mastersizer 3000, Malvern Panalytical, Malvern, UK). Carbon dioxide (CO2) samples were collected using the static chamber method, and their concentrations were subsequently quantified with a portable greenhouse gas analyzer (G2508, Picaro, San Francisco, CA, USA). The oxidation-reduction potential (ORP) was monitored using a portable soil ORP detector (ORP30, Clean, Shanghai, China). The pH and electrical conductivity (EC) were monitored using a handheld soil detector (LB-101, LuBo Environmental Protection, Qingdao, China).

Treatment differences were evaluated using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Duncan’s new multiple range test was applied for post hoc comparisons. All analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics (Version 27).

3. Results

3.1. Amendment Effect of Manganese Sand

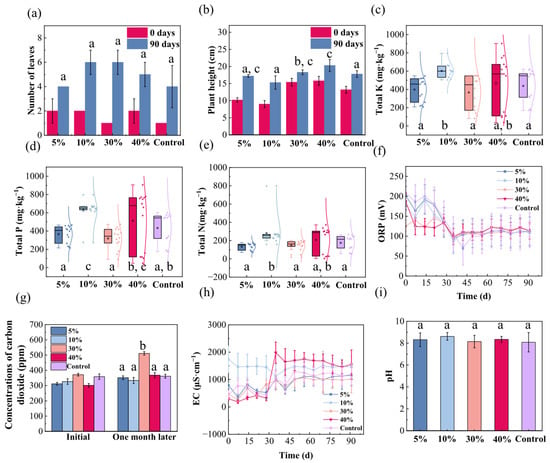

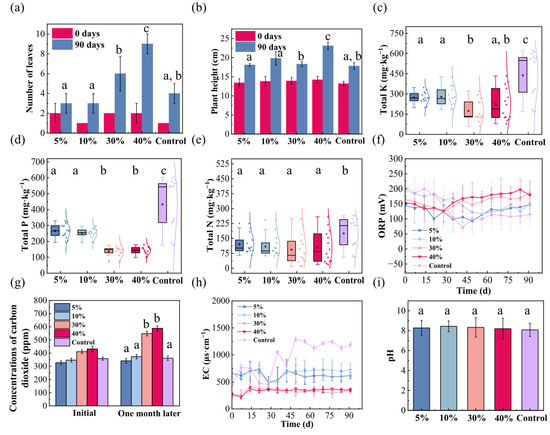

Figure 1 illustrates the effects of varying manganese sand addition ratios on coastal wetland sediment properties and the growth of the mangrove plant, Kandelia obovata. In terms of leaf development, manganese sand amendment generally promoted leaf proliferation compared to the control. Over the 90-day period, plants in manganese sand-treated groups exhibited a net increase of 1–2 leaves relative to the control. Specifically, 5% manganese sand addition showed no significant effect on leaf number, while 10% manganese sand addition induced a more pronounced promotional effect. Increasing the addition ratio to 30% provided no significant further improvement compared to the 10% manganese sand group. However, at 40% manganese sand, a noticeable decline in leaf count occurred compared to the 10% and 30% groups, suggesting a suppression effect at higher concentrations (Figure 1a). Plant height also exhibited a clear dosage dependence: seedlings grown in 5% and 10% manganese sand substrates reached 6–8 cm, outperforming both the control and higher manganese sand treatments (30% and 40%), which showed growth similar to the control, indicating that the growth-promoting effect diminishes as the addition ratio increases (Figure 1b). These findings confirm that the addition of manganese sand to the substrate positively influences Kandelia obovata growth, preliminarily eliminating concerns regarding its biotoxicity to mangroves and supporting its environmental compatibility for use in coastal wetland restoration.

Figure 1.

Effects of manganese sand addition ratios on Kandelia obovata growth and coastal wetland substrate properties. (a) Leaf number; (b) Plant height (decrease denotes pruning of withered apices); (c) Total potassium; (d) Total phosphorus; (e) Total nitrogen; (f) Oxidation-reduction potential (ORP); (g) CO2 emission; (h) Electrical conductivity (EC); (i) pH. Different lowercase letters denote significant differences (p < 0.05, Duncan’s test).

Analysis of sediment physicochemical properties revealed that manganese sand addition did not significantly alter substrate particle size within one month, confirming the physical stability of the amended sediment (Figure S2a). During the experimental period, manganese sand addition to the substrates effectively regulated nutrient dynamics in the overlying water and demonstrated significant removal of nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P), and potassium (K). This suggests that the material functions not only as a physical adsorbent but may also facilitate specific biogeochemical processes that immobilize or transform these elements. A non-linear response to manganese sand dosage was observed in total K content, which changed to 90%, 137%, 84%, and 106% of the control level for 5%, 10%, 30%, and 40% manganese sand, respectively, with the 30% manganese sand treatment achieving the most substantial K removal (Figure 1c). A similar trend was evident for total P, with contents shifting to 84%, 146%, 74%, and 118% across the same addition gradient, again identifying 30% manganese sand as the most effective ratio (Figure 1d). In contrast, total N content varied to 77%, 161%, 84%, and 119% for 5%, 10%, 30%, and 40% manganese sand, with the 5% manganese sand treatment demonstrating the highest N removal efficiency (Figure 1e). The amendment of 10% manganese sand resulted in significantly lower concentrations of TN, TP, and TK compared to the control group (p < 0.05, Duncan’s test). A comprehensive analysis indicated that the 30% manganese sand substrate showed the most balanced and effective overall performance in terms of nutrient removal.

The ORP of manganese sand-amended substrates decreased gradually during the first 30 days and stabilized thereafter, suggesting an initial shift towards reduced conditions before reaching a steady state (Figure 1f). Initial monitoring revealed virtually identical levels of released CO2 across all manganese sand additions and the control, precluding a direct role for manganese sand in early CO2 dynamics. After 30 days, however, the 30% manganese sand group showed a sharp increase in CO2 emissions. This implies that a high dosage of manganese sand uniquely enhances microbial activity, likely by accelerating the decomposition of organic matter or boosting microbial respiration rates [41] (Figure 1g). EC monitoring showed that the addition of manganese sand led to initial fluctuations in the substrates until approximately 30 days, after which values stabilized, mirroring the trend observed in the control. This indicates that manganese sand incorporation did not alter the fundamental physicochemical properties of the substrate system, maintaining its ionic buffering capacity and self-regulatory ability, thereby ensuring long-term EC stability (Figure 1h). The pH of all substrates remained stable between 7 and 9 throughout the experiment, demonstrating the resilience of the native buffering system against manganese sand incorporation and underscoring the material’s chemical compatibility (Figure 1i). The reason for the fluctuation of these physical and chemical properties is that manganese sand (primarily MnO2) is not an inert material. Its effectiveness is governed by dynamic redox reactions in the rhizosphere. Fluctuations in soil moisture, organic acid exudates from roots, and microbial activity can rapidly cycle manganese between its different oxidation states (e.g., Mn4+ ↔ Mn2+). This cycling can cause transient shifts in pH and the release/immobilization of manganese and other ions, which in turn leads to the observed variability in plant growth responses and soil parameters over time. Rather than a flaw, this dynamic nature is an intrinsic property of a chemically active amendment, and its initial phases may indeed exhibit instability before reaching a new equilibrium [42,43].

3.2. Amendment Effect of Maifan Stone

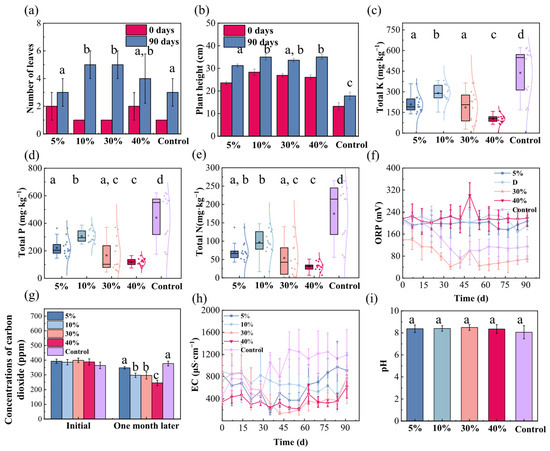

Figure 2 illustrates the effects of different maifan stone addition ratios on the remediation of coastal wetland sediments. Regarding leaf development, maifan stone amendment generally enhanced the growth of Kandelia obovata compared to the control, yielding a net increase of 1–2 leaves over the 90 days. Specifically, a 5% addition ratio showed no significant effect, whereas 10% addition exhibited a clear promotional effect. Further increasing the ratio to 30% provided no additional benefit over the 10% group, and a 40% ratio even led to a reduction in leaf number relative to the 10% and 30% groups, indicating that excessive maifan stone addition does not yield continuous improvement and may instead inhibit growth (Figure 2a). In terms of plant height, Kandelia obovata in maifan stone-amended substrates reached 14–18 cm within 90 days. A 5% addition ratio already stimulated growth, and this effect intensified with increasing addition levels up to a threshold, beyond which it plateaued, suggesting a saturation point in the growth-promoting capacity of maifan stone (Figure 2b). These findings collectively demonstrate that maifan stone-amended substrate promotes the growth of Kandelia obovata, alleviating concerns regarding its potential ecological toxicity and supporting its application as a safe and effective material for coastal wetland restoration.

Figure 2.

Effects of maifan stone addition ratios on Kandelia obovata growth and coastal wetland substrate properties. (a) Leaf number; (b) Plant height (decrease denotes pruning of withered apices); (c) Total potassium; (d) Total phosphorus; (e) Total nitrogen; (f) Oxidation-reduction potential (ORP); (g) CO2 emission; (h) Electrical conductivity (EC); (i) pH. Different lowercase letters denote significant differences (p < 0.05, Duncan’s test).

To further elucidate the impact of maifan stone on the sediment environment, we analyzed key physicochemical properties under varying addition ratios. Particle size analysis showed no significant alterations within one month of maifan stone incorporation, confirming the physical stability of the amended substrate (Figure S2b). Throughout the experiment, maifan stone-amended sediments exhibited substantial removal of nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium, effectively regulating nutrient balance. These results imply that beyond mere physical adsorption, maifan stone may stimulate specific biogeochemical processes (e.g., microbial-mediated transformations or enhanced plant uptake), thereby facilitating nutrient fixation and transformation and mitigating eutrophication pressure in the surrounding environment. Maifan stone addition ratio exerted a significant nonlinear influence on total potassium removal. Compared to the control, addition ratios of 5%, 10%, 30%, and 40% reduced total potassium content to 47%, 66%, 42%, and 23% of the control level, respectively, with the 40% group exhibiting the most pronounced removal efficiency (Figure 2c). A similar trend was observed for total phosphorus, with contents declining to 50%, 69%, 37%, and 27% of the control at the corresponding ratios, also with optimal performance in the 40% group (Figure 2d). Total nitrogen removal likewise displayed a dose-dependent response, with contents reduced to 41%, 56%, 31%, and 18% of the control, and the highest removal capacity was again observed at the 40% addition level (Figure 2e). The amendment of maifan stone resulted in significantly lower concentrations of TN, TP, and TK compared to the control group (p < 0.05, Duncan’s test). Overall, the 40% maifan stone-amended substrate showed the best comprehensive performance in nutrient removal, highlighting its strong potential for managing nutrient loads in coastal wetland remediation.

The ORP of the original sediment gradually decreased before 30 days and stabilized thereafter, indicating a decline in oxidative capacity during the initial stage and a gradual equilibration of the redox milieu after one month. Among the amended groups, only the 30% maifan stone substrate followed a comparable trajectory. In contrast, substrates with 5%, 10%, and 40% maifan stone maintained stable ORP values around 200 mV from the outset, suggesting that these addition ratios contribute to a more stable redox environment within the sediment (Figure 2f). The addition of maifan stone initially showed a negligible impact on released CO2, ruling out a direct role in short-term fluxes. Subsequently, a pronounced decrease in CO2 emissions emerged, which scaled with the maifan stone dosing ratio. This points to a maifan stone-induced modification of the sediment microenvironment that likely suppresses microbial respiration and/or enhances CO2 fixation [44] (Figure 2g). EC monitoring indicated that maifan stone-amended substrates underwent fluctuations prior to day 30 before stabilizing. Although the overall trend resembled that of the control, the stabilized EC values in maifan stone-treated groups were systematically lower. Given the efficient nutrient removal observed, we propose that maifan stone may regulate sediment ionic strength by adsorbing and immobilizing soluble ions, offering a promising strategy for salinity management in coastal wetlands (Figure 2h). The pH of all substrates remained stable between 8 and 9 throughout the experiment, indicating that maifan stone amendment does not disrupt the inherent buffering capacity of the system. We attribute this stability to the mild chemical properties of maifan stone, which enable it to regulate nutrients without substantially releasing or consuming H+/OH− ions. This capacity to maintain ambient pH is of practical significance for preventing acidification or alkalization and ensuring the long-term efficacy of wetland ecological engineering (Figure 2i).

3.3. Amendment Effect of Bentonite

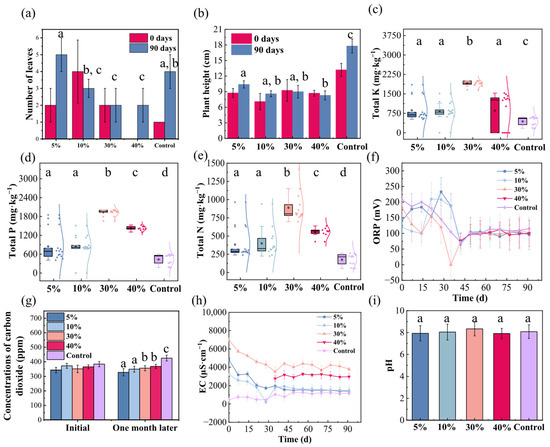

Figure 3 depicts the effects of varying bentonite addition ratios on coastal wetland substrates. In terms of leaf number, bentonite amendment generally inhibited the growth of Kandelia obovata leaves compared to the control, with a net reduction of 1–2 leaves over the 90 days. Specifically, a 5% addition ratio showed no significant promoting effect, although one to two more leaves were observed relative to the control. In contrast, 10% addition exerted a clear inhibitory effect, resulting in fewer leaves after 90 days than at the initial stage. Increasing the addition ratio to 30% did not further alter this effect compared to the 10% group, with no significant change in leaf number after 90 days. At 40% addition, leaf count decreased relative to the 10% group but remained similar to the 30% group. These results indicate that bentonite addition significantly inhibits leaf formation in Kandelia obovata (Figure 3a). Regarding plant height, Kandelia obovata in bentonite-amended substrates reached only 7–9 cm within 90 days. Both 5% and 10% addition ratios inhibited growth, markedly reducing plant height increment compared to the control. The 30% and 40% addition ratios showed even stronger inhibition, with no increase in plant height over the 90-day experimental period; instead, a decrease was observed (Figure 3b). This further demonstrates the negative impact of bentonite addition on the growth of Kandelia obovata. This study clearly confirms the growth-inhibiting effect of bentonite-amended substrate on Kandelia obovata, revealing its potential ecological risks in coastal wetland environments and providing critical insights for scientifically evaluating its environmental behavior and establishing safe application thresholds.

Figure 3.

Effects of bentonite addition ratios on Kandelia obovata growth and coastal wetland substrate properties. (a) Leaf number; (b) Plant height (decrease reflects pruning of withered apices); (c) Total potassium; (d) Total phosphorus; (e) Total nitrogen; (f) Oxidation-reduction potential (ORP); (g) CO2 emission; (h) Electrical conductivity (EC); (i) pH. Different lowercase letters denote significant differences (p < 0.05, Duncan’s test).

To further investigate the influence of bentonite on the substrate environment, we analyzed the physicochemical properties under different addition ratios. Particle size analysis of the substrate showed no significant deviation in grain-size parameters within one month of bentonite incorporation, indicating that a stable composite structure formed between bentonite and native substrate particles, thereby ensuring the long-term physical stability of the amended system (Figure S2c). During the experimental period, bentonite-amended substrates exhibited a significant enrichment capacity for nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium, leading to increased nutrient contents in the substrate. Although this resulted in nutrient accumulation within the sediment, the process essentially transferred and immobilized nutrients from the water column to the substrate, effectively reducing the nutrient load in the aqueous phase and alleviating eutrophication pressure in the surrounding environment. The bentonite addition ratio exhibited a notable nonlinear effect on total potassium enrichment. Compared to the control, addition ratios of 5%, 10%, 30%, and 40% increased total potassium content to 198%, 187%, 434%, and 194% of the control level, respectively, with the 30% group showing the most pronounced enrichment (Figure 3c). A similar trend was observed for total phosphorus, with contents rising to 196%, 197%, 446%, and 328% of the control at the corresponding ratios, again with the highest increase in the 30% group (Figure 3d). Total nitrogen also showed a comparable pattern, increasing to 219%, 228%, 508%, and 319% of the control, respectively, and the strongest enrichment capacity was demonstrated at the 30% addition level (Figure 3e). The amendment of bentonite resulted in significantly lower concentrations of TN, TP, and TK compared to the control group (p < 0.05, Duncan’s test). These results indicate that bentonite amendment generally enhances nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium contents in the substrate, with the strongest enrichment effect consistently observed at a 30% addition ratio. The parallel dose–response patterns for all three elements suggest the involvement of a universal physicochemical mechanism rather than element-specific processes.

The ORP of the original sediment showed a fluctuating decline before day 45 and stabilized thereafter, indicating a gradual weakening of oxidative capacity and an unstable state in the early experimental stage, followed by redox equilibrium in the later phase. Substrates with different bentonite addition ratios followed the same variation pattern, demonstrating that bentonite addition did not alter the inherent redox characteristics of the substrate (Figure 3f). This suggests that bentonite, as an amendment, exhibits good chemical inertness and does not interfere with the inherent electron transfer processes in wetland substrates. The 45-day mark may represent a critical time point for redox stabilization in such substrates, providing a useful reference for designing monitoring cycles in future wetland restoration projects. Initial monitoring of released CO2 ruled out the direct involvement of bentonite in CO2 production or consumption. The negative dose-dependent reduction in CO2 suggests a long-term, indirect mechanism. A testable hypothesis is that bentonite promotes the abiotic fixation of CO2 into carbonate phases [45] (Figure 3g). EC monitoring showed that bentonite-amended substrates experienced fluctuations before day 30 and then stabilized. Although the trend was generally consistent with the original substrate, the EC values of bentonite-treated groups were systematically higher than those of the control after stabilization. Combined with the material’s significant nutrient enrichment capacity, this suggests that bentonite may release soluble ions into pore water while immobilizing nutrients, leading to an overall increase in system conductivity (Figure 3h). Monitoring data showed that the pH of all treatment groups (including the control) remained within the weakly alkaline range of 7–9. This indicates that bentonite addition does not disrupt the inherent buffering capacity of the substrate system, and the acid-base balance remains stable. We attribute this to the intrinsic chemical buffering properties of bentonite, which allow it to participate in nutrient conversion without significantly interfering with the proton balance of the system. This ability to maintain pH stability is of considerable practical importance for preventing wetland soil degradation and ensuring the sustainability of ecological engineering (Figure 3i).

3.4. Amendment Effect of Iron–Carbon

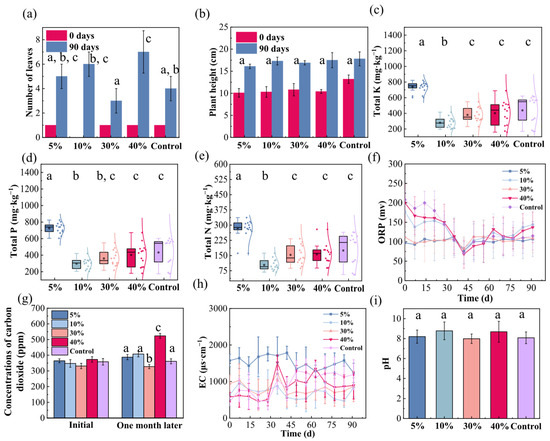

Figure 4 demonstrates the effects of different iron–carbon (Fe-C) addition ratios on the physicochemical properties of coastal wetland sediments and their subsequent influence on plant growth. In terms of leaf development, Fe-C addition generally promoted leaf growth in Kandelia obovata over the 90 days, with an overall increase of 1–2 leaves compared to the control. Specifically, 5% Fe-C addition resulted in 1–2 additional leaves, while 10% addition led to a more pronounced increase of 2–3 leaves. However, at 30% addition, an inhibitory effect was observed, with only 1–2 extra leaves. In contrast, 40% addition produced the most significant promotion, increasing leaf number by 3–4 leaves (Figure 4a). Regarding plant height, Kandelia obovata grown in Fe-C amended substrates exhibited a slightly greater increase than the control over 90 days. Plant height showed a gradual upward trend with increasing addition ratio, although absolute differences among treatments remained relatively small (Figure 4b). These growth responses indicate that Fe-C addition exerts complex dose-dependent effects: a non-monotonic response in leaf number—with optimal promotion at 40% and inhibition at 30%—contrasts with a steady increase in plant height with addition ratio. These findings underscore the need for precise optimization of the Fe-C amendment ratio, with 40% showing the greatest potential for enhancing vegetative growth in Kandelia obovata.

Figure 4.

Effects of iron–carbon (Fe-C) addition ratios on Kandelia obovata growth and coastal wetland substrate properties. (a) Leaf number; (b) Plant height (decrease denotes pruning of withered apices); (c) Total potassium; (d) Total phosphorus; (e) Total nitrogen; (f) Oxidation-reduction potential (ORP); (g) CO2 emission; (h) Electrical conductivity (EC); (i) pH. Different lowercase letters denote significant differences (p < 0.05, Duncan’s test).

To further elucidate the impact of Fe-C addition on the substrate environment, we systematically analyzed sediment physicochemical properties under different addition ratios. Particle-size analysis indicated that substrate composition remained stable over one month, confirming the formation of a stable composite structure between Fe-C and sediment particles and ensuring long-term physical stability (Figure S2d). Monitoring data revealed that Fe-C addition differentially regulated nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium levels in the aqueous phase. Total potassium responded non-linearly to the addition ratio: relative to the control, 5%, 10%, 30%, and 40% Fe-C led to potassium levels of 169%, 64%, 87%, and 92% of the control, respectively. The 5% group showed notable nutrient enrichment, whereas the 10% group exhibited the strongest removal (Figure 4c). Total phosphorus followed a similar trend, with corresponding values of 167%, 69%, 83%, and 93% of the control. Again, the 5% and 10% groups displayed the highest enrichment and removal efficiency, respectively (Figure 4d). Total nitrogen also showed a comparable pattern, with concentrations reaching 163%, 59%, 87%, and 90% of the control across the same addition gradient, and the 10% group demonstrating the highest removal capacity (Figure 4e). The amendment of 5% and 10% Fe-C resulted in significantly lower concentrations of TN, TP, and TK compared to the control group (p < 0.05, Duncan’s test). These results highlight a complex dose–response relationship in nutrient regulation: low-level (5%) Fe-C addition enhances nutrient accumulation, whereas 10% addition maximizes removal efficiency. At higher ratios (30–40%), removal performance declines slightly but remains superior to the control. This non-monotonic behavior suggests the involvement of multiple interaction mechanisms—such as chemical reduction, adsorption, and microbial-mediated transformation—with the dominant process varying by element and addition ratio.

The ORP of the native soil decreased irregularly over the first 30 days before stabilizing, reflecting a transition from an initial oxidized condition to a reduced equilibrium. Fe-C addition did not markedly alter the inherent redox characteristics of the substrate, as all addition groups displayed similar ORP trajectories and ranges (Figure 4f). This confirms good interfacial compatibility of the Fe-C amendment and its minimal disruption to native electron transfer processes. It also validates 30 days as a critical time point for achieving redox stability in such systems, offering a scientific basis for monitoring cycles in wetland restoration projects. Monitoring of released CO2 revealed a significant dose-dependent effect: low Fe-C addition ratios (5–10%) resulted in a marginal increase in concentration, the 30% group exhibited a distinct suppression, and the 40% group triggered a pronounced surge (Figure 4g). This biphasic pattern implies complex interactions among competing biogeochemical processes. The slight rise at low doses and the sharp increase at 40% may reflect a shift in dominant microbial metabolism—from limited mineralization to stimulated heterotrophic respiration or organic matter decomposition. Conversely, the unexpected decrease observed at the 30% addition highlights a potential “sweet spot”, where the Fe-C amendment may optimally enhance chemolithoautotrophic processes that consume CO2 or promote its conversion into insoluble carbonate phases [46]. Collectively, these results demonstrate that the net impact of Fe-C on carbon dynamics is not a simple linear function, but rather the net outcome of competing mechanisms whose balance is critically governed by the application rate. EC stabilized after approximately 30 days of fluctuation across all Fe-C treatments. Notably, only the 5% addition ratio significantly increased substrate EC, while other ratios exhibited trends similar to the control (Figure 4h). This indicates a concentration threshold effect, whereby low-level Fe-C addition markedly influences the ionic environment, whereas medium to high ratios produce minimal impact. pH monitoring showed that all Fe-C treatments and the control maintained stability within the weakly alkaline range (pH 7.0–9.0), indicating that the amendment did not disrupt the intrinsic buffering capacity of the substrate (Figure 4i). This stability can be attributed to the inherent pH-buffering ability of the Fe-C composite, which helps maintain proton balance during nutrient cycling—a favorable characteristic for sustaining wetland ecosystem health and supporting sustainable low-carbon restoration technologies.

3.5. Amendment Effect of Vermiculite

Figure 5 illustrates the effects of varying vermiculite addition ratios on coastal wetland substrates, encompassing both the growth response of Kandelia obovata and associated physicochemical changes. Regarding leaf development, the leaf number of Kandelia obovata increased with higher vermiculite addition ratios, rising from 1–2 leaves (control) to 6–8 leaves after 90 days. This marked enhancement indicates that vermiculite amendment significantly promotes the growth of Kandelia obovata, likely by facilitating increased carbon dioxide assimilation via photosynthesis and subsequent conversion into organically stored carbon (Figure 5a). In terms of plant height, only the 40% vermiculite treatment promoted vertical growth relative to the control, whereas lower ratios (5–30%) showed no significant effect. This suggests that low vermiculite content has minimal impact on plant development, posing limited risk to wetland ecosystem structure and function under natural conditions (Figure 5b). Collectively, these growth observations demonstrate that while low vermiculite addition has negligible phytotoxic effects, appropriate dosing can substantially promote Kandelia obovata biomass accumulation, offering a viable strategy for targeted wetland ecological restoration.

Figure 5.

Effects of vermiculite addition ratios on Kandelia obovata growth and coastal wetland substrate properties. (a) Leaf number; (b) Plant height (decrease denotes pruning of withered apices); (c) Total potassium; (d) Total phosphorus; (e) Total nitrogen; (f) Oxidation-reduction potential (ORP); (g) CO2 emission; (h) Electrical conductivity (EC); (i) pH. Different lowercase letters denote significant differences (p < 0.05, Duncan’s test).

To further elucidate vermiculite’s influence on the substrate environment, we analyzed its physicochemical properties under different addition ratios. Particle size analysis revealed no significant alterations in substrate grain-size distribution within one month of vermiculite incorporation, suggesting the formation of a stable composite structure between vermiculite and native sediment particles that ensures long-term physical stability of the amended system (Figure S2e). During the 90-day experiment, all vermiculite-amended substrates showed significant reduction in total potassium, phosphorus, and nitrogen compared to the control. In such nutrient-depleted conditions, plants typically develop more efficient nutrient acquisition strategies, such as enhanced root development and microbial symbioses (e.g., with rhizobia or arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi), to improve nitrogen and phosphorus uptake. Concurrently, suppression of fast-growing, nutrient-demanding species may promote a more balanced community structure in wetland ecosystems. Vermiculite addition ratio exhibited a nonlinear relationship with total potassium removal, with the 30% group achieving the most effective reduction (to 39.8% of the control). The 5%, 10%, and 40% groups reduced potassium to 62.3%, 63%, and 50.9% of the control, respectively (Figure 5c). Total phosphorus content showed a decreasing yet stabilized trend across all treatments, consistently remaining lower than the control, indicating vermiculite’s capacity to remove phosphorus from sediments and mitigate aqueous eutrophication risk (Figure 5d). Similarly, vermiculite amendment effectively reduced total nitrogen across all addition ratios (5%, 10%, 30%, and 40%), lowering nitrogen content to 69.2%, 62%, 53.2%, and 60.9% of the control, respectively, demonstrating stable and significant nitrogen removal efficiency (Figure 5e). The amendment of vermiculite resulted in significantly lower concentrations of TN, TP, and TK compared to the control group (p < 0.05, Duncan’s test). These findings collectively indicate that optimized vermiculite amendment can simultaneously maintain essential sediment nutrients and reduce eutrophication pressure, offering synergistic benefits for ecological adaptation, environmental protection, and plant performance.

The ORP of the original sediment remained below the control during the first 30 days, then exceeded it thereafter, suggesting a transition from initially oxidized to progressively reduced conditions. We hypothesize that early oxygen consumption by Kandelia obovata root respiration promoted growth while lowering ORP. By day 30, an equilibrium between respiration and photosynthesis was likely established. The subsequent ORP increase may reflect oxygen release via photosynthetic activity and organic carbon storage, demonstrating that vermiculite amendment supports plant-mediated carbon cycling and contributes to ecosystem stability (Figure 5f). Initial CO2 monitoring showed negligible effects from low vermiculite addition. After one month, however, a clear dose-dependent escalation in CO2 release was observed. A proposed explanation is that vermiculite enhances either microbial or plant root respiration, surpassing photosynthetic uptake [47] (Figure 5g). EC results showed systematically lower values across all vermiculite-amended substrates compared to the control. This supports the role of vermiculite as a sediment conditioner, leveraging its high cation exchange and adsorption capacity to improve substrate structure and enhance water retention (Figure 5h). pH monitoring revealed that all vermiculite-amended substrates maintained weakly alkaline conditions (pH ≈ 8), similar to the control. This stability underscores vermiculite’s role as a natural buffer, mitigating rapid pH fluctuations and enabling gradual nutrient release within the plant growth medium. A stable pH environment not only favors Kandelia obovata growth and nutrient uptake but also enhances overall nutrient retention and substrate structural integrity (Figure 5i).

4. Discussion

This study compared the effects of five substrate amendments and found that, except for bentonite, the other four materials, viz., vermiculite, manganese sand, Fe-C, and maifan stone, all promoted the growth of Kandelia obovata to varying degrees. These results confirm the effectiveness and safety of these four materials as environmentally friendly amendments, alleviating concerns about their potential ecotoxicity to mangroves and supporting their practical application in coastal wetland restoration.

All five materials exhibited excellent performance in maintaining the physical stability of the substrate. Particle size analysis conducted within one month of amendment showed no significant changes, indicating the formation of stable composite structures with native sediment particles and ensuring long-term physical integrity. Evaluation of nutrient removal efficiency revealed the following order: Fe-C > vermiculite > maifan stone > manganese sand. The 10% Fe-C substrate showed the best comprehensive performance with the highest removal rates for total nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium. The 30% vermiculite substrate demonstrated effectiveness in potassium removal with satisfactory nitrogen and phosphorus reduction. 40% maifan stone also achieved optimal nitrogen removal. Manganese sand exhibited element-specific removal patterns. Notably, bentonite functioned as a nutrient-enrichment substrate, transferring and fixing nutrients from water to sediment rather than removing them. The 40% maifan stone amendment achieved TN and TP removal rates comparable to those reported for more complex, engineered remediation systems (Supplementary Table S2) [48,49,50,51].

ORP analysis revealed three distinct patterns: bentonite and Fe-C maintained stable, high ORP levels; vermiculite and manganese sand followed the natural ORP trajectory of the original sediment; and maifan stone showed concentration-dependent effects. At the carbon cycle level, our results demonstrate that the addition of different materials exerts distinct effects on soil CO2 release. Maifan stone and bentonite significantly suppressed CO2 emissions, whereas high-loading additions of manganese sand, iron–carbon, and vermiculite substantially promoted them. This material-specific influence is likely mediated through their contrasting impacts on processes such as organic matter mineralization. EC monitoring revealed three regulatory modes: bentonite and low-dose Fe-C (5%) increased conductivity; vermiculite and maifan stone decreased ionic strength; while manganese sand and medium-to-high dose Fe-C (10–40%) maintained native electrochemical conditions with minimal perturbation. The stability of substrate pH under all amendment conditions underscores a key practical advantage: these materials can be applied without the risk of inducing adverse acidification or alkalization. Preserving the original pH environment is critical for the predictable management of wetland ecosystems and enhances the feasibility of employing these amendments in large-scale restoration. Overall, considering the growth of Kandelia obovata, nitrogen reduction, and CO2 sequestration effects, we believe that maifan stone is the optimal amendment, with a 40% addition yielding the best nitrogen reduction and CO2 sequestration effects.

Building on these results, we recommend that future research: (1) conduct long-term field trials to validate the durability and ecological impacts of these amendments under natural tidal regimes; (2) employ isotopic tracing and microbial community analysis to mechanistically resolve the pathways of nutrient removal and CO2 flux modulation; and (3) develop integrated life-cycle and cost–benefit models to guide the selection of amendment types and dosing for specific restoration goals.

5. Conclusions

This study provides a comprehensive, ratio-specific evaluation of five substrate amendments for the synergistic phytoremediation of coastal wetlands with Kandelia obovata. The growth of Kandelia obovata was significantly influenced by the amendment type and ratio. Vermiculite, iron–carbon, manganese sand, and maifan stone were confirmed as safe and effective. In stark contrast, bentonite consistently inhibited plant growth, highlighting its potential ecological risk. The amendments exhibited distinct functions in nutrient management. Iron–carbon (10%) demonstrated the highest comprehensive nutrient removal efficiency. Vermiculite (30%) also showed effective and balanced nutrient removal. Maifan stone achieved high removal performance, albeit at a high dosage (40%). Conversely, bentonite acted not as a removal agent but as a nutrient enrichment material, transferring and immobilizing nutrients from the water to the sediment phase. All amendments successfully maintained substrate physical stability and pH buffering capacity. Their impacts on other parameters were varied: they induced distinct ORP patterns and differentially influenced CO2 emissions. Maifan stone and bentonite suppressed CO2 release, while high-loading manganese sand, Fe-C, and vermiculite enhanced it. These material-specific effects on the substrate microenvironment must be considered in relation to restoration goals. Based on a holistic assessment of plant growth promotion, nutrient removal efficiency, and CO2 sequestration potential, maifan stone is identified as the optimal amendment. A preliminary cost estimate suggests that the material and application costs for the 40% maifan stone and 10% Fe-C treatments would be approximately 129.6 and 63 ¥·m−2, respectively. The choice between amendments can be guided by economic considerations: the 40% maifan stone is preferable where maximizing performance is paramount, whereas the 10% Fe-C amendment offers a balanced and economically favorable option for achieving effective nutrient removal. The 40% maifan stone incorporation ratio is recommended for achieving the most effective integrated eco-remediation performance in coastal wetland systems. This work offers a scientifically grounded and practical strategy for enhancing the synergy between plant and substrate in coastal wetland restoration, providing a clear pathway for optimizing future ecological engineering applications.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/su172411142/s1.

Author Contributions

H.J. conceived the idea. X.P. and J.L. performed the experiments and analyzed the data. Z.W., S.J., Y.L., S.H., K.M., M.Z. and X.Z. provided constructive suggestions and discussion. X.P. wrote the manuscript. X.Z. and H.J. supervised the work. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was financially supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (No. 2023YFE0101700).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Wu, Y.; Zhang, R.; MacDougall, A.S.; Tian, D.; Wang, J.; Niu, S. Wetland restoration is effective but insufficient to compensate for soil organic carbon losses from degradation. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2025, 34, e70063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Qin, L.; Kong, L.; Tian, W.; Zhao, C. Temporal variation of soil phosphorus fractions and nutrient stoichiometry during wetland restoration: Implications for phosphorus management. Environ. Res. 2025, 266, 120486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zhong, Q.; Meng, Q.; Xu, W. Environmental behaviors and ecological risks of trace metals in typical mangrove wetlands in the pearl river delta, south china. Mar. Environ. Res. 2025, 212, 107514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, J.; Fan, X.; Lu, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, Z.; He, S.; Lyu, H.; Li, J. Geochemical behavior of iron-sulfur coupling in coastal wetland sediments and its impact on heavy metal speciation and migration. Mar. Environ. Res. 2025, 207, 107065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mutillod, C.; Buisson, É.; Mahy, G.; Jaunatre, R.; Bullock, J.M.; Tatin, L.; Dutoit, T. Ecological restoration and rewilding: Two approaches with complementary goals? Biol. Rev. Camb. Philos. Soc. 2024, 99, 820–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Q.; Liu, G.; Casazza, M.; Dumontet, S.; Yang, Z. Ecosystem restoration programs challenges under climate and land use change. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 807, 150527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Ouyang, Y.; Cai, L.; Dai, J.; Wu, Y. Ecological restoration approaches for degraded muddy coasts: Recommendations and practice. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 149, 110182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Liu, X.; Li, X.; Tian, C. Soil organic carbon changes following wetland restoration: A global meta-analysis. Geoderma 2019, 353, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, N.; Ma, Z. Ecological restoration of coastal wetlands in china: Current status and suggestions. Biol. Conserv. 2024, 291, 110513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, B.; Liu, Y.; Meadows, M.E. Ecological restoration for sustainable development in china. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2023, 10, nwad033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Lin, B.; Fang, Q.; Jiang, X. Effectiveness assessment of china’s coastal wetland ecological restoration: A meta-analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 934, 173336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Xu, D.; Xu, Z.; Tang, H.; Jiang, H.; Dong, J.; Liu, Y. Ten key issues for ecological restoration of territorial space. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2024, 11, nwae176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, K.; Yang, L.; Tao, J.; Xu, X.; Zheng, X.; Wu, Y.; Jin, K.; Xiao, D.; Zhao, M.; Han, W. Effect of cipangopaludina chinensis and diversity of plant species with different life forms on greenhouse gas emissions from constructed wetlands. Atmos. Pollut. Res. 2024, 15, 102120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Liu, K.; Ning, T.; Huang, G.; Zhang, Q.; Li, Y.; Wang, M.; Fan, Y.; An, W.; Ji, L.; et al. Environmental remediation promotes the restoration of biodiversity in the shenzhen bay estuary, south china. Ecosyst. Health Sustain. 2022, 8, 2026250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panda, S.K.; Das, S. Potential of plant growth-promoting microbes for improving plant and soil health for biotic and abiotic stress management in mangrove vegetation. Rev. Environ. Sci. Biotechnol. 2024, 23, 801–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Yang, S.; Liu, H.; Hu, Q.; Liu, X.; Wang, J.; Wang, J.; Xin, W.; Chen, Q. Physiological and transcriptomic analysis of the mangrove species kandelia obovata in response to flooding stress. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2023, 196, 115598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verâne, J.; Dos Santos, N.C.P.; Da Silva, V.L.; de Almeida, M.; de Oliveira, O.M.C.; Moreira, Í.T.A. Phytoremediation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in mangrove sediments using rhizophora mangle. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2020, 160, 111687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Gan, S.; Yang, P.; Zhou, J.; Huang, X.; Chen, H.; He, H.; Saintilan, N.; Sanders, C.J.; Wang, F. A global assessment of mangrove soil organic carbon sources and implications for blue carbon credit. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 8994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ur Rahman, S.; Han, J.; Zhou, Y.; Ahmad, M.; Li, B.; Wang, Y.; Huang, Y.; Yasin, G.; Ansari, M.J.; Saeed, M.; et al. Adaptation and remediation strategies of mangroves against heavy metal contamination in global coastal ecosystems: A review. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 441, 140868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karmakar, S.; Riya, K.K.; Jolly, Y.N.; Akter, S.; Mamun, K.M.; Kabir, J.; Paray, B.A.; Arai, T.; Yu, J.; Ngah, N.; et al. Effectiveness of artificially planted mangroves on remediation of metals released from ship-breaking activities. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2025, 212, 117587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bappy, M.M.M.; Rahman, M.M.; Hossain, M.K.; Moniruzzaman, M.; Yu, J.; Arai, T.; Paray, B.A.; Hossain, M.B. Distribution and retention efficiency of micro- and mesoplastics and heavy metals in mangrove, saltmarsh and cordgrass habitats along a subtropical coast. Environ. Pollut. 2025, 370, 125908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evenson, G.R.; Golden, H.E.; Christensen, J.R.; Lane, C.R.; Kalcic, M.M.; Rajib, A.; Wu, Q.; Mahoney, D.T.; White, E.; D’Amico, E. River basin simulations reveal wide-ranging wetland-mediated nitrate reductions. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 57, 9822–9831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, L.; Ni, B.; Zou, Y.; Freeman, C.; Peng, X.; Yang, L.; Wang, G.; Jiang, M. Deciphering soil environmental regulation on reassembly of the soil bacterial community during wetland restoration. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 954, 176586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Huang, X.; Chen, S.; Xu, Y.; Qiao, Y.; Jia, R.; Zhang, S.; Lin, W.; Jiao, X.; Shi, M.; et al. Bioremediation of heavy metals by mangrove rhizosphere microbes: Extracellular adsorption mechanisms and enhanced performance of immobilized aestuariibaculum sp. JKB11. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 498, 139968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meera, S.P.; Bhattacharyya, M.; Nizam, A.; Kumar, A. A review on microplastic pollution in the mangrove wetlands and microbial strategies for its remediation. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2022, 29, 4865–4879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Xia, Y.; Chen, X.; Wang, J.; Liu, W.; Wang, Z.; Su, Z.; Ren, H. Enhanced sediment microbial diversity in mangrove forests: Indicators of nutrient status in coastal ecosystems. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2025, 211, 117421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Lin, X.; An, X.; Liu, S.; Wei, X.; Zhou, T.; Li, Q.; Chen, Q.; Liu, X. Mangrove afforestation as an ecological control of invasive spartina alterniflora affects rhizosphere soil physicochemical properties and bacterial community in a subtropical tidal estuarine wetland. PeerJ 2024, 12, e18291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, Y.; Dong, J.; Wang, H.; Shang, M.; Xie, H.; Du, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, Y. Spatiotemporal response of water quality in fragmented mangroves to anthropogenic activities and recommendations for restoration. Environ. Res. 2023, 237, 117075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, S.; Zhang, H.; Xu, Z.; Lin, G.; Lin, Y.; Liang, X.; Ling, J.; Wee, A.K.S.; Lin, H.; Zhou, Y.; et al. Coastal urbanization may indirectly positively impact growth of mangrove forests. Commun. Earth Environ. 2024, 5, 608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, H.; Li, Z.; Chen, H.; Zhou, J.; Lv, C. Effects of biochar and plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria on plant performance and soil environmental stability. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, X.; Liu, Q.; Pan, F.; Yao, Y.; Luo, X.; Chen, C.; Liu, T.; Zou, L.; Wang, W.; Wang, J.; et al. Research advances in the impacts of biochar on the physicochemical properties and microbial communities of saline soils. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Xie, H.; Liu, X.; Kong, D.; Zhang, S.; Wang, C. A novel green substrate made by sludge digestate and its biochar: Plant growth and greenhouse emission. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 797, 149194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.; Pan, Y.; Jin, X.; Zhao, S.; Xu, X.; Chen, Y.; Shen, Z.; Chen, C. A novel biochar-PGPB strategy for simultaneous soil remediation and safe vegetable production. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 356, 124254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, M.; Ilyas, N.; Bibi, F.; Shabir, S.; Jayachandran, K.; Sayyed, R.Z.; Shati, A.A.; Alfaifi, M.Y.; Show, P.L.; Rizvi, Z.F. Development of novel kinetic model based on microbiome and biochar for in-situ remediation of total petroleum hydrocarbons (TPHs) contaminated soil. Chemosphere 2023, 324, 138311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, H.; Ye, J.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, M.; Peng, W.; Wang, H.; Tang, D. Evaluation and characterization of biochar on the biogeochemical behavior of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in mangrove wetlands. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 864, 161039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, T.; Meng, M.; Wang, N.; Xu, X.; Lu, H.; Yang, Q. Investigation on desorption of petroleum hydrocarbon contaminants by active and passive particle self-rotation. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 106330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Cui, Z.; Li, S.; Song, Z.; He, M.; Huang, D.; Feng, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, K.; Wang, X.; et al. Unlocking osmotic energy harvesting potential in challenging real-world hypersaline environments through vermiculite-based hetero-nanochannels. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Duan, X.; Wang, J.; Cheemaa, N.; Nazish, H.T.; Peng, G. Bentonite and its modified derivatives: Application and factors influencing radioactive nuclide adsorption. Prog. Nucl. Energy 2026, 191, 106104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Liu, H.; Ma, C.; Chen, W.; Huangfu, X. Treatment of wastewater containing thallium(i) by long-term operated manganese sand filter: Synergistic action of MnOx and MnOM. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 908, 168085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Q.; Hu, Y.; Fu, N.; Zhang, X.; Shen, Q. Improving semi-thermophilic anaerobic digestion of kitchen waste by iron-carbon materials regulation: Insights from energy supply and genetic information processing. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2025, 203, 107971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, J.; Chen, X. Microbial conversion of CO2 to organic compounds. Energy Environ. Sci. 2024, 17, 7017–7034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, J.; Guo, Z.; Zhang, M.; Xie, Y.; Shi, R.; Huang, X.; Tuo, Y.; He, X.; Xiang, P. Mn-modified bamboo biochar improves soil quality and immobilizes heavy metals in contaminated soils. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2024, 34, 103630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brüggenwirth, L.; Behrens, R.; Schnee, L.S.; Sauheitl, L.; Mikutta, R.; Mikutta, C. Interactions of manganese oxides with natural dissolved organic matter: Implications for soil organic carbon cycling. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2024, 366, 182–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Zheng, X.; Wen, Y.; Yu, C.; Li, D.; Zhang, H. Microbial-induced carbon dioxide (CO2) mineralization: Investigating the bio-mineralization chemistry process and the potential of storage in sandstone reservoir. Appl. Energy 2025, 377, 124268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Qu, F.; Sun, Z.; Shah, S.P.; Li, W. Carbon sequestration, performance optimization and environmental impact assessment of functional materials in cementitious composites. J. CO2 Util. 2024, 90, 102986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhang, W.; Jin, H.; Li, Z.; Liu, G.; Xing, F.; Tang, L. Exploring the carbon capture and sequestration performance of biochar-artificial aggregate using a new method. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 859, 160423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, X.; Wang, B.; Yuan, Y.; Lei, J.; Qian, C. Interactions between deep microbial biosphere and geo-sequestrated CO2: A review. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2025, 197, 105958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.; Xu, W.; Wang, H.; Zhao, D.; Ding, H. Nitrogen and phosphorus removal efficiency and denitrification kinetics of different substrates in constructed wetland. Water 2022, 14, 1757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Hu, M.; Xu, Y.; Tao, M.; Guan, L.; Kong, Y.; Cao, S.; Jing, Z. Synergistic removal of nitrogen and phosphorus in constructed wetlands enhanced by sponge iron. Water 2024, 16, 1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, M.; Jing, Z.; Shen, Y.; Cao, S.; Li, Y. Nitrogen and phosphorus removal in microbial fuel cell-constructed wetland integrated with layered double hydroxides coated filter for treating low carbon wastewater. J. Water Process Eng. 2025, 70, 106907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Zhou, K.; Huang, L. Effects of manganese sand proportion on nitrogen and phosphorus removal performance and microbial community in constructed wetlands. Processes 2025, 13, 3804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).