Abstract

This study examines the determinants of tolerance among higher education students in Montenegro and their implications for educational and societal sustainability. Guided by the framework of Education for Sustainable Development (ESD), it investigates how socio-demographic factors, economic insecurity, political orientations, and digital media use shape attitudes toward ethnic, religious, and cultural diversity. Cross-sectional survey data were collected from 469 students in 2021 and analysed using binary logistic regression. Results show that education is the strongest predictor of tolerant attitudes (p < 0.01), highlighting the transformative role of higher education in fostering inclusive and sustainability-relevant competencies. Economic insecurity, particularly unemployment, was associated with more exclusionary views, linking social equity to sustainability outcomes. Gender (p < 0.001), age (p = 0.07), and engagement with human-rights content online (p < 0.01) also emerged as significant predictors. Religiosity showed a modest negative association with tolerance (p = 0.01). The final model explained 37% of the variance in tolerant attitudes (Nagelkerke R2 = 0.37). Digital media played an ambivalent role: while it increased exposure to diverse perspectives, it also contributed to polarization, underscoring the need for critical digital literacy within ESD-aligned curricula. Overall, the findings demonstrate that inclusive education, digital competence, and participatory learning environments are central to building tolerant, cohesive, and sustainability-oriented societies. The study contributes to ESD scholarship by linking social inclusion, sustainability competencies, and the role of higher education in post-transition contexts.

1. Introduction

In recent decades, attitudes toward diversity have undergone significant transformations across Europe, with younger generations—particularly university students—generally exhibiting greater openness to ethnic, religious, and cultural differences [1,2,3]. Recent empirical studies offer nuanced evidence from post-conflict contexts in Southeast Europe. Mulalic (2023) found that university and high school students in Bosnia and Herzegovina demonstrate low engagement with peace education and limited awareness of tolerance-building programs, highlighting gaps in formal curricula [4]. Similarly, Matevski & Matevska (2020) observed that ethnic identity and national belonging continue to influence attitudes toward religious and cultural out-groups among North Macedonian students, despite increased exposure to higher education [5]. Nevertheless, concerns about immigration and multiculturalism persist, especially in regions shaped by complex historical and socio-political legacies. Montenegro, a multiethnic country at the intersection of Eastern and Western influences, presents a distinctive context for examining these dynamics. As a post-socialist and post-conflict society navigating European integration, Montenegro reflects both aspirations for democratic inclusivity and the enduring influence of nationalist discourse.

Tolerance is not only a social virtue but also a core competency for sustainable development. The United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 4.7 calls on higher education institutions to promote knowledge, skills, and values that foster sustainable lifestyles, human rights, gender equality, and a culture of peace. Here, tolerance can be understood both as an outcome of inclusive education and a precondition for building cohesive, sustainable societies. Within ESD scholarship, tolerance is increasingly conceptualised as a key sustainability competency—linked to systemic thinking, participatory learning, and intercultural empathy—necessary for advancing peaceful and resilient societies [6,7].

Recent bibliometric and systematic reviews of Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) in higher education identify three main research clusters: (1) sustainability management and governance in universities, (2) sustainability competencies, and (3) curriculum implementation and integration [8,9,10]. For example, Wiek et al. (2011) [11] outline a foundational framework of sustainability competencies to support academic program design, while Rieckmann (2021) [12] emphasizes the need for future-oriented higher education approaches that operationalize these competencies in diverse institutional contexts. These studies indicate that ESD in higher education has expanded rapidly over the past decade, emphasizing measurable learning outcomes and whole-institution transformation [13,14]. Recent empirical studies, such as Wang et al. (2022) [15] and Sánchez-Carracedo et al. (2021) [16], confirm that competency-based pedagogies and interdisciplinary learning approaches improve students’ sustainability mindsets, action competences, and intercultural awareness in HEI settings. Similarly, Lozano et al. (2022) [17] found that transformative, systems-thinking pedagogies enhance students’ social responsibility and preparedness to address sustainability challenges. Despite evidence that ESD enhances student motivation, engagement, and problem-solving abilities [18,19], implementation remains uneven across contexts due to limited resources, insufficient teacher training, and a lack of valid evaluation indicators [20]. Systematic reviews also highlight the persistence of institutional barriers, including inconsistent curriculum alignment and weak evaluation models, especially in lower-resource or transitional higher education systems [19,21].

By linking tolerance with sustainability competencies such as critical thinking, empathy, and civic responsibility, this study contributes to current debates on how higher education can operationalize ESD in post-transition societies. These competencies align with UNESCO’s framework for Education for Sustainable Development Goals, which prioritizes inclusive, transformative learning for peace, rights, and sustainable living [22].

Several theoretical perspectives help explain how tolerance is formed, each offering distinct mechanisms for understanding attitudes toward diversity in higher education contexts. Intergroup Contact Theory [23] emphasizes that meaningful intergroup interaction reduces prejudice through positive contact under appropriate conditions, a finding that has been repeatedly confirmed in contemporary university settings [24,25]. Integrated Threat Theory [26,27] explains how perceived realistic and symbolic threats—often rooted in economic insecurity or cultural competition—can generate exclusionary attitudes, particularly in transitional societies [28]. Post-materialist values theory [29,30] argues that economic security supports the development of self-expression values and tolerance, whereas precarity fosters retrenchment and authoritarian preferences. Social Identity Theory [31] highlights the role of in-group identification and collective affiliations in shaping intergroup attitudes, with recent extensions illustrating its relevance in understanding polarization and identity-based exclusion among university students [32,33]. These frameworks are especially relevant for transitional societies like Montenegro, where historical narratives and identity politics continue to shape intergroup relations.

To integrate these theoretical perspectives into a coherent conceptual model, the key predictors examined in this study are positioned within their underlying frameworks. Education is linked to transformative learning theory and ESD scholarship, both of which emphasise that higher education fosters critical reflection, intercultural understanding, and sustainability competencies that reduce prejudice. Religiosity is interpreted through Social Identity Theory and cultural value models, which suggest that strong in-group identification may shape attitudes toward out-groups in ways that differ across cultural contexts. Economic insecurity aligns with Integrated Threat Theory, where perceived material and symbolic threats can reinforce exclusionary orientations. Following human-rights content online reflects contemporary extensions of Intergroup Contact Theory, in which digital exposure to diverse perspectives can operate as a form of mediated contact. Taken together, these connections provide an integrated rationale for examining how structural, psychological, and digital factors jointly shape tolerant attitudes among higher education students.

In this study, tolerance was operationally defined as a composite measure of attitudes toward ethnic, religious, and cultural diversity. The composite variable included survey items capturing acceptance of different ethnic groups, support for LGBTQ+ rights, and openness to religious diversity.

Education is widely recognized as a central driver of tolerance and inclusion. Multicultural curricula, participatory pedagogies, and transformative learning approaches have been shown to enhance empathy, reduce prejudice, and strengthen sustainability competencies [34,35,36]. However, the extent to which education fosters tolerance depends on institutional commitment and broader political conditions [37]. Higher education thus plays a pivotal role in advancing ESD by equipping students with critical thinking, intercultural understanding, and digital literacy—competencies essential for addressing contemporary societal challenges.

Digital media adds another layer of complexity. Online platforms enable access to diverse perspectives but can also amplify polarization through algorithmic filtering and echo chambers [38,39]. For university students, digital literacy becomes a crucial competency for navigating identity, civic participation, and sustainability challenges [40]. Without these skills, opportunities for intercultural learning risk being overshadowed by misinformation and ideological division.

Although Montenegro’s legal framework guarantees minority rights, the uneven implementation of inclusion policies and persistent socio-economic inequalities limit their impact [41,42]. Marginalized groups such as the Roma continue to face barriers to education, employment, and healthcare, highlighting the need for systemic and sustained interventions.

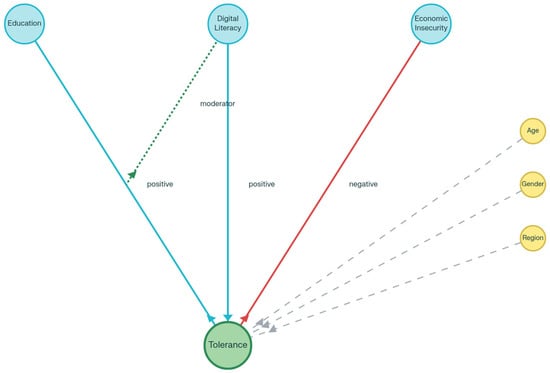

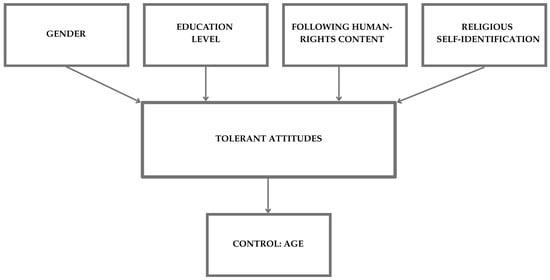

In recent years, Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) has been widely acknowledged as a crucial factor in promoting tolerance within diverse societies. However, the mechanisms linking education to tolerance are complex and potentially moderated by other variables such as digital literacy and economic insecurity. To clarify these interrelations, we developed a conceptual framework (Figure 1) that illustrates the hypothesized direct and indirect influences of education, digital literacy, economic insecurity, and related factors on tolerance among higher education students. This framework guided the formulation of our research questions.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework illustrating the hypothesized relationships among education, digital literacy, economic insecurity, and tolerance, authors.

Against this backdrop, this study addresses three interrelated research questions:

- (1)

- To what extent do higher education students in Montenegro express tolerant attitudes toward ethnic, religious, and cultural diversity?

- (2)

- How do these attitudes compare with broader European and regional trends?

- (3)

- Which individual and contextual factors—such as education, economic security, political engagement, and digital media use—influence tolerance levels?

- (4)

- How does digital literacy interact with education level to influence tolerance among higher education students?

By situating these findings within the framework of Education for Sustainable Development (ESD), the study contributes to ongoing debates on how higher education can cultivate sustainability competencies—such as empathy, tolerance, and civic responsibility—essential for inclusive and sustainable societies in post-transition contexts.

2. Materials and Methods

This study employed a mixed-methods research design combining quantitative and qualitative data collection and analysis. A structured online survey was conducted in Montenegro in 2021 among a broader youth population aged 15–30. For the purpose of the present analysis, only respondents currently enrolled in higher education institutions were included, to examine determinants of tolerance and their implications for educational and societal sustainability. The sample included students from multiple universities across Montenegro, covering a balanced mix of public and private institutions. The universities represented various regions, including urban and rural areas, ensuring geographic diversity. To prevent duplicate survey responses, measures such as restricting multiple submissions from the same IP address and distributing unique survey links were implemented.

The questionnaire consisted of 21 items in multiple-choice and Likert-scale formats, addressing demographic characteristics, perceptions of diversity and discrimination, social interactions, political attitudes, and digital media use. It also included an open-ended question inviting participants to propose measures for improving societal tolerance. The instrument was pre-tested with a pilot group (n = 25) to ensure clarity, internal consistency, and relevance, leading to minor adjustments in item wording and structure. The questionnaire was developed collaboratively with social psychologists and sociologists familiar with youth attitudes and intergroup relations in the Western Balkan context. To ensure conceptual and theoretical alignment, survey items were formulated in accordance with the core dimensions of Intergroup Contact Theory, Integrated Threat Theory, and Social Identity Theory. While the instrument was not directly adapted from standardised tools such as the World Values Survey or European Social Survey, several items were modelled on comparable constructs used in prior European and regional studies. This consultative and theory-informed process helped ensure content validity, contextual relevance, and coherence with established frameworks on tolerance and diversity.

Participants were recruited through university mailing lists, student organizations, and social media platforms to ensure diversity across academic disciplines, socio-economic backgrounds, and regions of Montenegro. A total of 469 valid responses from higher education students were included in the analysis.

To increase transparency in the operationalization of constructs used in the logistic regression analysis, Table 1 summarizes all variables included in the Student Tolerance Model, specifying their roles (dependent, independent, control), descriptions, and coding schemes.

Table 1.

Variables used in the Student Tolerance Model.

In the logistic regression model, male gender, lower education level, not following human-rights content, and non-religious identification served as the reference categories. To further improve methodological clarity, the rationale for using both binary logistic regression and principal component analysis (PCA) has been elaborated. Logistic regression enabled the identification of key predictors of tolerant attitudes, while PCA served to uncover the broader latent value dimensions underlying individual attitudinal items, thereby providing a complementary analytical perspective on how these patterns cluster within the student population. Logistic regression was applied because the dependent variable—tolerant attitudes—was operationalized as a binary outcome, allowing the estimation of effect sizes and predictive relationships. PCA was used to detect underlying attitudinal structures among correlated survey items and to examine how these value orientations align with broader theoretical expectations. Before conducting these analyses, statistical assumptions were evaluated. Multicollinearity diagnostics indicated no concerns, with Variance Inflation Factors ranging from 1.02 to 1.41. The suitability of PCA was confirmed through a Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin value of 0.78 and a significant Bartlett’s test of sphericity (p < 0.001), which together confirm sampling adequacy and the reliability of the factor-extraction procedure.

Quantitative data were analyzed using descriptive statistics, chi-square tests, correlation analysis, logistic regression, and principal component analysis (PCA). A statistically significant association was observed between gender and perceptions of societal tolerance (χ2 = 61.82, p < 0.001), with a moderate effect size (Cramér’s V = 0.21). Logistic regression identified key demographic predictors of tolerant attitudes, while PCA extracted latent dimensions related to tolerance. The internal consistency of the instrument was confirmed with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.86.

Open-ended responses were analyzed thematically to capture subjective insights and complement the quantitative findings through methodological triangulation.

All participants provided informed consent prior to participation. The study adhered to ethical standards for social science research, ensuring anonymity, voluntariness, and data protection. Ethical approval was granted by the Ethics Committee of the University of Donja Gorica (approval code: UDG-EC-2021-04, 15 April 2021).

The data and results presented are original and have not been published elsewhere. The dataset was purpose-built for this study. Data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request, in accordance with ethical and privacy considerations.

No generative artificial intelligence (GenAI) tools were used in the production of text, data, or analysis in this study. Minor language editing was performed manually by the authors.

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics

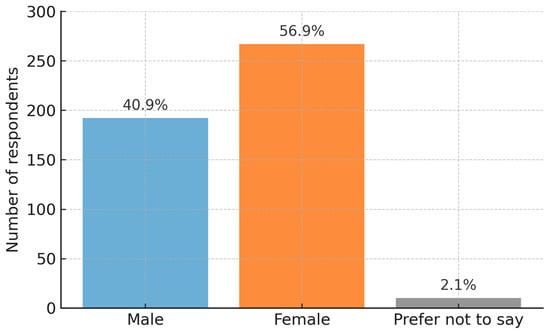

The final sample included 469 respondents currently enrolled in higher education institutions across Montenegro, representing diverse academic disciplines and geographic regions. Female students comprised 56.9% (n = 267) of the sample, 40.9% (n = 192) were male, and 2.1% (n = 10) preferred not to disclose their gender. This gender distribution reflects common participation patterns observed in voluntary online surveys within higher education contexts (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Gender Distribution. Source: Youth Tolerance Survey of Montenegro (2021), authors’ calculations.

3.2. Awareness and Perceptions of Social Tolerance

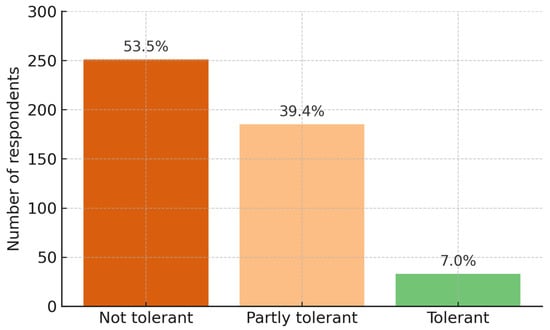

Awareness of the International Day for Tolerance was modest among higher education students; 29% (n = 136) reported being familiar with it, while the remaining respondents were unaware of this observance. When asked whether Montenegrin society can be considered tolerant, most higher education students expressed a critical view: 53.5% (n = 251) stated that it is not tolerant, 39.4% (n = 185) believed it is only partly tolerant, and only 7.0% (n = 33) considered it tolerant (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Perception of Social Tolerance in Montenegro. Source: Youth Tolerance Survey of Montenegro (2021), authors’ calculations.

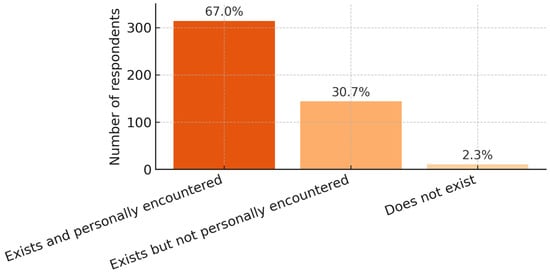

When asked whether nationalism exists in Montenegro and to what extent it is present, the vast majority of students acknowledged its persistence. Two thirds (66.9%, n = 314) reported that nationalism exists and that they personally encounter it, 30.7% (n = 144) believed it exists but had not experienced it directly, while only 2.3% (n = 11) stated that nationalism does not exist (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Perception of Nationalism in Montenegro. Source: Youth Tolerance Survey of Montenegro (2021), authors’ calculations.

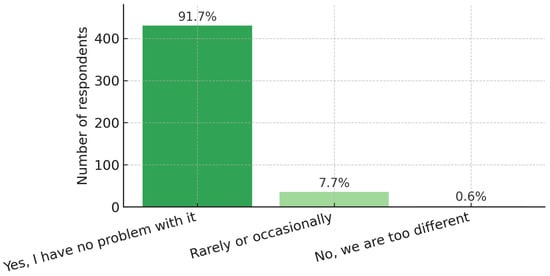

Social interactions across ethnic lines were overwhelmingly positive. A vast majority of students (91.7%, n = 430) reported having friendships with individuals of different national backgrounds and expressed no discomfort in such interactions. 7.7% (n = 36) stated that they rarely or occasionally socialize with people from other ethnic groups, while only 0.6% (n = 3) indicated reluctance to do so (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Friendships Across National Backgrounds. Source: Youth Tolerance Survey of Montenegro (2021), authors’ calculations.

3.3. Cultural and Political Attitudes

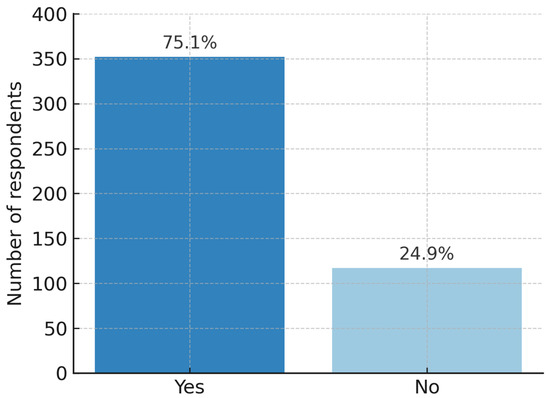

A substantial majority of students (75.1%, n = 352) believed that all cultural and religious groups in Montenegro should have representation in the national government, while 24.9% (n = 117) disagreed (Figure 6). Following the 2020 parliamentary elections in Montenegro, 49.9% of students believed that the political situation would improve, 30.7% expected no major changes, and 19.4% anticipated a decline in political conditions.

Figure 6.

Support for Cultural Representation. Source: Youth Tolerance Survey of Montenegro (2021), authors’ calculations.

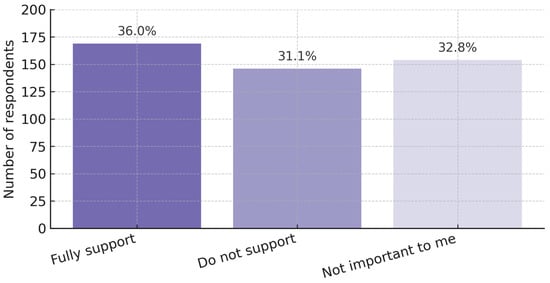

Regarding LGBTQ+ rights, 36.0% of students fully supported the legalization of same-sex partnerships, 31.1% opposed it, while 32.8% stated that the issue was not important to them (Figure 7). When asked whether transgender and homosexual individuals should have the same rights as others, 73.8% (n = 346) of students agreed, while 26.2% (n = 123) disagreed. When asked about the possibility of a relationship or marriage with a transgender person, 78.0% (n = 366) of students responded negatively, 16.2% (n = 76) were uncertain, and only 5.8% (n = 27) expressed willingness to do so.

Figure 7.

Same-Sex Partnership Law Support. Source: Youth Tolerance Survey of Montenegro (2021), authors’ calculations.

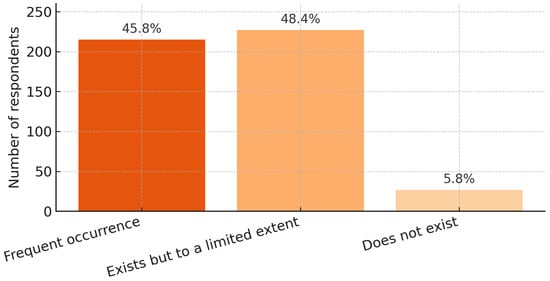

When asked about the presence of religious discrimination in Montenegro, 45.8% (n = 215) of students considered it a frequent occurrence, while 48.4% (n = 227) believed it exists but to a limited extent. Only 5.8% (n = 27) stated that such discrimination does not exist (Figure 8). These findings indicate that most students recognize religious discrimination as a persistent, though variably perceived, social issue. When asked whether a person of a different race would be accepted in their social environment, 60.1% (n = 282) of students believed such a person would be only partly accepted, 32.2% (n = 151) thought they would be fully accepted, while 7.7% (n = 36) stated they would not be accepted.

Figure 8.

Perception of Religious Discrimination. Source: Youth Tolerance Survey of Montenegro (2021), authors’ calculations.

3.4. Media Influence and Digital Behavior

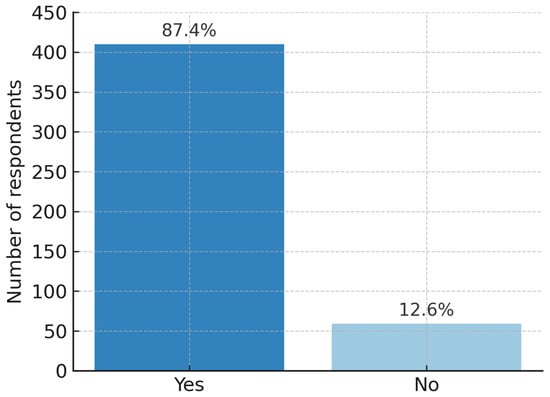

Most students (87.4%, n = 410) believed that social media can serve as an effective platform for educating the public about discrimination and its consequences, while 12.6% (n = 59) disagreed (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Social Media Role in Awareness. Source: Youth Tolerance Survey of Montenegro (2021), authors’ calculations.

3.5. Statistical Associations and Predictive Modelling

Beyond descriptive findings, a broader analytical approach was applied to explore which factors most strongly predict tolerant attitudes among higher education students. The constructed “Student Tolerance Model” integrates demographic, socio-cognitive, and value-based dimensions to identify the underlying drivers of inclusivity within the university population (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

Statistical Associations and Predictive Modelling, authors’ calculations.

Figure 1 illustrates the conceptual structure of the Student Tolerance Model, including the dependent variable (tolerant attitudes), four independent predictors (gender, education level, following human-rights content, religious self-identification), and the control variable (age). Arrows denote the direction of hypothesised influence tested in the logistic regression model.

Binary logistic regression was used to examine how gender, education, following human-rights content online, age, and religious self-identification shape tolerant outlooks. As shown in Table 2, the model correctly classified 74% of cases and demonstrated good explanatory power (Nagelkerke R2 = 0.37). Education emerged as the strongest predictor of tolerant attitudes (OR = 2.10, p < 0.01), followed by gender, with female students more likely to express inclusive views (OR = 1.97, p < 0.001). Students who regularly follow human-rights–related content online also showed higher odds of expressing tolerant views (OR = 1.80, p < 0.01). This effect likely reflects the combined influence of greater exposure to diverse perspectives, more opportunities for critical and civic learning, and instructional approaches that support dialogue and reflection. Age exhibited a marginal positive effect (p = 0.07). In contrast, students who self-identified as religious were somewhat less likely to report tolerant attitudes (OR = 0.70, p = 0.01). However, previous research indicates that the relationship between religiosity and tolerance varies across cultural settings, depending on dominant religious norms, the nature of religious socialization, and broader value systems.

Table 2.

Binary logistic regression predicting tolerant attitudes, authors’ calculations.

To better visualize interrelations among attitudes, a principal component analysis (PCA) was performed, revealing two dominant latent dimensions:

- Inclusive Values Component (43% variance explained)—encompassing support for LGBTQ+ rights, racial and religious acceptance, and social media as a platform for anti-discrimination education.

- Institutional Confidence Component (24% variance explained)—defined by belief in multicultural representation in government and awareness of tolerance-related global observances.

We conducted Principal Component Analysis (PCA) exclusively on attitudinal survey items, including those related to ethnic, religious, and gender attitudes. Behavioral indicators, such as reported participation in tolerant actions, were analyzed separately and not included in the PCA.

3.6. Qualitative Insights

To complement the survey results, students provided open-ended reflections on how to reduce nationalism, homophobia, transphobia, racism and religious discrimination. A thematic analysis (inductive coding) revealed eight recurring themes, ranging from strongly inclusion-oriented proposals to skepticism and resistance. Previous research on youth attitudes similarly shows that educational exposure, intergroup contact, and media environments play a central role in shaping tolerance levels, which aligns with the dominant themes observed in these open-ended responses.

- Education across the pipeline (dominant theme).

Students repeatedly proposed systematic education from early grades through university: dedicated courses (civic/global education), classroom discussions, school workshops, and university seminars linking diversity, human rights, and critical thinking. Typical suggestions emphasized “starting early,” “learning to respect differences,” and “integrating these topics as part of normal schooling rather than one-off events.”

Representative quote: “Children should learn from an early age that differences are normal and should be respected. This needs to be part of regular education.”

- 2.

- Dialogue, contact, and lived-experience exposure.

Many advocated structured intergroup contact: mixed-group workshops, debates, “living-library” formats, and testimonials that humanize minority experiences. The intent was to replace abstract labels with personal stories and empathy-building encounters.

Representative quote: “People understand much more once they hear real stories and experiences. It reminds them that behind every label there is a person.”

- 3.

- Media and digital campaigns.

Students saw social media and TV as double-edged: powerful for awareness yet prone to polarization. Proposed actions included short factual videos, biographical stories, campus-led Instagram pages, and collaborations with credible public figures to normalize inclusion and counter misinformation.

Representative quote: “Social media should be used for short educational content that explains these topics clearly and simply.”

- 4.

- Family socialization and early norms.

A sizeable set pointed to the family as the primary source of (in)tolerance. Measures included parent-focused information sessions, school–family partnerships, and guidance for discussing sensitive topics at home.

Representative quote: “Everything starts at home. If parents teach children to respect differences, they will see the world that way.”

- 5.

- Institutional and legal measures.

Proposals included clearer codes of conduct, consistent sanctions for hate speech and discrimination, equal representation of cultural/religious groups in public bodies, and alignment with EU human-rights frameworks.

Representative quote: “We need clear rules and real consequences for hate speech, along with better representation of different groups in institutions.”

- 6.

- Socio-economic levers.

Some respondents linked prejudice to frustration and insecurity, recommending policies that improve employment prospects and reduce precarity—framed as indirect but meaningful drivers of social cohesion.

Representative quote: “When people have better living conditions and fewer worries about survival, there is less frustration and less space for intolerance.”

- 7.

- Religion, tradition, and public discourse.

Comments diverged: some advocated limiting religious institutions’ influence on politics to reduce divisions; others argued for “patriotic” or tradition-affirming narratives. This cleavage mirrors broader societal debates about identity and values.

Representative quote: “It is important to separate religion from politics more clearly, because mixing them increases divisions.”

- 8.

- Skepticism and resistance.

Alongside constructive ideas, a non-trivial subset expressed resignation (“this will always exist”) or overt rejection of LGBTQ+ inclusion (sometimes in harsh language). These responses underline that progress requires not only information but also norm-setting, contact, and institutional safeguards.

Representative quote: “Some people think nothing will ever change, no matter how much we talk about these issues.”

Taken together, students most often converged on education + dialogue + media literacy as mutually reinforcing levers, with institutional rules and family engagement as necessary supports. The presence of resistant voices signals that knowledge transmission alone is insufficient; effective interventions must combine curricular work (knowledge/skills), intergroup contact (empathy), digital citizenship (online behavior), and consistent enforcement (norms).

4. Discussion

4.1. Key Findings and Interpretations

This study offers the first systematic evidence on tolerance among higher education students in Montenegro, revealing both encouraging signs of openness and persistent attitudinal divides, with direct implications for educational and societal sustainability. The findings align with broader European and Balkan trends but also reflect Montenegro’s distinct socio-political context. These findings align with the assumptions of transformative learning theory and sustainability-oriented education frameworks. Both perspectives suggest that intercultural competencies, critical reflection, and systemic awareness foster increased tolerant attitudes and more inclusive worldviews [34,43]. This indicates that tolerance, in addition to being a social attitude, can be understood as an emerging sustainability competency shaped by learning environments and institutional practices.

While our findings support a strong association between higher education and tolerant attitudes, the cross-sectional nature of our data limits the ability to determine the direction of causality. Both theoretical reasoning and prior studies suggest that education can foster tolerance by broadening perspectives; however, it is equally plausible that individuals predisposed towards tolerance are more likely to pursue higher educational opportunities.

Tolerant attitudes among students were most strongly associated with inclusive value orientations—notably support for LGBTQ+ rights, openness toward racial diversity, and endorsement of multicultural political representation—while perceiving nationalism as widespread was negatively related to tolerant attitudes. Gender and education level showed moderate but noteworthy associations, indicating that structured learning environments and gendered socialization patterns may indirectly shape inclusivity. These results suggest that higher education contributes to tolerance primarily through the competencies it cultivates—such as intercultural understanding, empathy, and digital citizenship—rather than through formal level alone. This also aligns with previous studies showing that competency-based and interdisciplinary pedagogical models increase learners’ sensitivity to cultural differences. Models grounded in ESD have been shown to strengthen global citizenship outcomes as well [15,16]. By situating tolerance within a broader sustainability competence framework, the present findings challenge narrow interpretations of tolerance as merely attitudinal and instead support its operationalisation as a measurable educational outcome.

The role of education therefore remains pivotal but should be reinterpreted as a platform for developing sustainability competencies rather than merely as an institutional credential. In the Montenegrin context, where civic education is still elective, the forthcoming Education Reform Strategy (2025–2035) [44] presents an opportunity to embed intercultural and experiential learning as core curricular elements. Such approaches are consistent with the framework of Education for Sustainable Development (ESD), which emphasizes systems thinking, intercultural dialogue, and empathy as key competencies for societal transformation. As Veidemane (2022) [45] notes, universities must also operationalize these competencies through measurable indicators and internationally comparable benchmarks to ensure systematic progress toward sustainability goals.

Economic insecurity also showed a contextual influence. In line with threat theory [26], respondents perceiving greater financial precarity were more likely to express exclusionary views. These findings support the extension of Integrated Threat Theory to post-transition societies, where perceived socio-economic instability reinforces symbolic and realistic threat perceptions that undermine openness to diversity [28,46]. With youth unemployment exceeding 40%, these findings highlight the need for integrative policies that connect social equity, economic resilience, and sustainable development [47].

Digital media played a dual role. A large majority of students (87.4%) perceived social media as an effective platform for education and awareness about discrimination, yet many also recognized the prevalence of online hostility and polarization. Similar findings across Europe [39,48] point to the urgency of national-level digital literacy initiatives. For higher education institutions, embedding digital citizenship within curricula represents a practical entry point for advancing both social inclusion and sustainability. In this context, Muhonen, Timonen, and Väänänen (2024) [49] demonstrate that integrating ESD competences through research, development, and innovation (RDI) enhances curricular relevance and promotes stakeholder-informed sustainability transformations.

Historical narratives and unresolved identity politics continue to shape intergroup relations. Montenegro’s contested national identity and the legacy of the Yugoslav past influence how students conceptualize belonging [50,51]. Comparative experiences from post-conflict education reforms in Rwanda and Bosnia illustrate that reconciliation-oriented curricula can mitigate such divisions [52,53]. Finally, the EU accession process offers transformative potential. Croatia’s experience indicates that alignment with EU frameworks on education, minority rights, and anti-discrimination can strengthen societal tolerance [54]. For Montenegro, continued convergence with these standards will be critical to sustaining inclusive and resilient pathways toward social and educational sustainability. Compared to EU-wide data, Montenegrin students demonstrate moderately lower levels of acceptance of ethnic diversity (32% in our sample versus 46% across the EU-27). This disparity may reflect Montenegro’s unique historical narratives and recent social transitions. It suggests that efforts to foster tolerant attitudes may benefit most from context-sensitive educational reforms [55].

4.2. Limitations

Several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the study relied on self-reported survey data addressing sensitive topics such as nationalism, minority rights, and gender diversity, which may have introduced social desirability bias and self-censorship among respondents. Second, the online sampling method limited participation to students with internet access and adequate digital literacy, potentially excluding less connected groups. Moreover, since the sample included only higher education students, the findings cannot be generalized to all youth in Montenegro.

The cross-sectional design provides a static view and does not capture how tolerance-related attitudes evolve over time or in response to political and educational changes. Future research should therefore incorporate longitudinal or intervention-based designs to examine whether targeted educational practices, such as ESD-oriented courses or structured intergroup dialogues, produce measurable changes in tolerant attitudes over time. Future longitudinal research should therefore explore the dynamics of tolerance formation within educational and social contexts, especially during periods of reform and institutional transition. Surveys about tolerance are particularly sensitive to cultural desirability bias. This bias occurs when respondents give answers that reflect positively on their social standing or align with socially valued traits, rather than their genuine attitudes. In cultures where tolerance is viewed as desirable, individuals may consciously or unconsciously overstate their openness or acceptance. As a result, the reported levels of tolerance in survey responses may be inflated compared to actual beliefs or behaviors. Anonymized survey methods and careful question design that we used could help mitigate—but not fully eliminate—this effect.

While the inclusion of open-ended responses enriched the quantitative analysis by providing contextual explanations, the absence of in-depth qualitative interviews or focus groups limited deeper insight into the motivations and emotional underpinnings behind certain attitudes. Future studies could adopt mixed-method approaches combining survey data with interviews, digital ethnography, or classroom observations. To improve future research on tolerance, supplementing self-reported survey data with behavioral measures can add depth and credibility. Methods such as implicit association tests (IATs) or observing reactions in classroom interventions reveal attitudes that people might not consciously admit or may not accurately report due to social desirability. For example, studies have found that participants often report higher satisfaction or greater attendance at cultural events in direct questions than what their behavior suggests, with implicit tests uncovering more nuanced or less socially desirable attitudes. Incorporating such approaches would enable validation of survey results and clarify the true prevalence of tolerant attitudes. Additionally, the reliance on a single-method attitudinal instrument imposes epistemological constraints on how tolerance is conceptualized and measured. While the principal component analysis (PCA) helped identify latent value dimensions linked to inclusive orientations, the absence of triangulation with behavioural or longitudinal measures limits the ability to capture dynamic or situational aspects of tolerance. Future research would benefit from integrating mixed-method designs and validated scales from comparative studies on intercultural sensitivity and sustainable citizenship (e.g., ISSI, GCE frameworks), which would strengthen construct validity and allow for a more comprehensive understanding of how attitudes interact with real-world behaviour.

Although digital media use was examined, this study did not assess algorithmic exposure, misinformation patterns, or online engagement mechanisms, which may significantly influence youth perceptions of diversity. Subsequent research should also investigate how ESD-oriented curricula, experiential learning, and digital citizenship education shape long-term tolerance and sustainability competencies among higher education students.

4.3. Comparative Perspectives: Montenegro and the Balkans

When viewed within a regional context, attitudes toward tolerant attitudes among higher education students in Montenegro appear to align with broader patterns observed across the Western Balkans, situated between more inclusive contexts (e.g., parts of Slovenia and Croatia) and more polarized ones (e.g., Romania or Serbia). While openness toward ethnic and gender diversity is gradually increasing, persistent biases—particularly regarding LGBTQ+ and Roma communities—remain a shared regional challenge [55].

Recent international indicators reinforce this regional positioning. According to the Special Eurobarometer 535: Discrimination in the EU [55], perceptions of discrimination based on ethnic origin, skin colour, religion/belief, and sexual orientation remain high across the EU, with Bulgaria and Romania consistently scoring among the least accepting countries. These East–West differences closely mirror patterns historically observed in Western Balkan societies, where comfort with intergroup contact tends to be lower than the EU-27 average. Findings from OECD’s Education at a Glance 2024 [56] likewise reveal persistent disparities in civic competencies and digital literacy across Southeast Europe, indicating structural factors that influence young people’s democratic attitudes and inclusion-related skills. Together, these updated sources contextualize Montenegrin students’ levels of tolerant attitudes within broader European and regional trends.

In Bosnia and Herzegovina, long-standing ethnic segregation in schools continues to reproduce exclusive narratives [57], while in Serbia, nationalist rhetoric and algorithm-driven polarization have been identified as key factors shaping youth attitudes [58]. Similar dynamics are reflected in Montenegro’s digital landscape, where social media simultaneously fosters awareness and reinforces ideological divides.

Although the extent and form of intolerance vary across countries, common structural drivers—such as economic insecurity, politicized identity discourse, and fragmented civic education systems—remain evident throughout the region. However, comparative analyses suggest that education policy and civic engagement frameworks can mitigate these risks by strengthening democratic participation and social inclusion.

Within the sustainability agenda, higher education emerges as a decisive lever for shaping inclusive worldviews and advancing SDG 4.7 on global citizenship and sustainable development. Integrating ESD principle, including intercultural dialogue, critical reflection, and participatory learning—across regional higher education systems could therefore play a transformative role in fostering tolerance, resilience, and social cohesion.

4.4. Challenges for Future Tolerance

Several interrelated dynamics may challenge future progress toward tolerance and social cohesion in Montenegro. Digital polarization, youth emigration, demographic aging, and potential climate-induced migration collectively pose risks that extend beyond individual attitudes, affecting broader patterns of inclusion and resilience.

Digital spaces represent both opportunity and risk. While a large majority of students view social media as a valuable platform for education and awareness, many also recognize its potential to amplify polarization and hate speech. Algorithmic echo chambers and selective exposure threaten to reinforce ideological divisions, underscoring the need for systematic digital literacy and media education anchored in ESD principles [39].

Youth emigration continues to produce a “double loss”—of both human capital and the socially progressive cohort most likely to support diversity and civic engagement [59]. Combined with demographic aging and declining birth rates, this trend may shift the social balance toward more conservative outlooks and reduce intergroup contact within communities.

Looking ahead, climate-related mobility may introduce new dimensions of diversity, testing the adaptability of existing tolerance norms and policy frameworks. Responding effectively to these overlapping challenges requires an integrated approach that links education, economic equity, and sustainability governance. Specifically, Montenegro will need to invest in:

- Digital literacy programs that strengthen critical media competence and counter online polarization;

- Economic strategies that reduce youth precarity and promote equitable participation;

- Inclusive educational reforms that mainstream intercultural and experiential learning across curricula; and

- Community-based initiatives that cultivate intergroup collaboration, dialogue, and youth participation in sustainability transitions.

4.5. Recommendations

The findings of this study reinforce the growing recognition that higher education plays a central role in shaping inclusive, democratic, and sustainability-oriented societies. Within the framework of Education for Sustainable Development (ESD), tolerance can be understood not only as a civic value but also as a core sustainability competency that supports peaceful, resilient, and socially cohesive communities. As ESD aims to equip learners with the knowledge, skills, and dispositions needed to address complex social and environmental challenges, the development of tolerant attitudes forms an essential component of this broader educational mandate.

Within ESD scholarship, tolerance is increasingly conceptualised as a key sustainability competency—linked to systemic thinking, participatory learning, and intercultural empathy—necessary for advancing peaceful and resilient societies [10,60,61]. This reframing positions tolerance not only as an ethical or civic virtue but as an integral learning outcome bridging higher education and societal transformation.

Recent European analyses emphasize that universities should move beyond fragmented or course-level initiatives and adopt whole-institution approaches to sustainability learning. The 2024 Eurydice report on Learning for Sustainability [62] highlights persistent gaps in teacher preparation, curricular integration, and institutional support across European higher-education systems. These structural gaps resonate with the findings of this study, in which education level and indicators of digital engagement emerged as strong predictors of tolerant attitudes. This suggests that strengthening sustainability-oriented curricula and digital literacy initiatives may hold particular potential for fostering inclusive and democratic values among Montenegrin students.

Contemporary ESD research also points to the importance of developing specific sustainability-related competencies. Empirical evidence from Hammer and Lewis (2023) [62] shows that students and graduates most frequently emphasize the importance of systems thinking, anticipatory reasoning, interdisciplinary problem-solving, perspective-taking, and targeted communication. Complementary findings from Muhonen et al. (2024) [49] indicate that sustainability-relevant competences in higher education cluster around disciplinary expertise, systems thinking, strategic reasoning, and integrative skills. Embedding these competencies through experiential, participatory, and dialogue-based pedagogies enhances learners’ understanding of societal interdependencies. It also strengthens their ability to navigate value pluralism, a capacity closely linked to tolerant and inclusive mindsets.

Taken together, these insights indicate several concrete opportunities for Montenegrin higher-education institutions. Universities could incorporate introductory modules on intercultural dialogue, digital citizenship, human-rights literacy, and sustainability ethics into general education courses. Activities such as community-based projects, living-library sessions, structured intergroup dialogues, and cross-disciplinary collaborations may further support the development of empathy, civic responsibility, and systems thinking. Teacher-training programmes may also include professional-development activities focused on inclusive pedagogy, participatory learning, and approaches for managing diversity in the classroom. These measures would align Montenegrin higher education more closely with international ESD benchmarks and support progress toward SDG 4.7, while simultaneously contributing to institutional cultures grounded in inclusion, social responsibility, and democratic citizenship.

4.5.1. Policy Recommendations

Based on the evidence presented, a coherent, cross-sectoral national strategy is required to integrate education, digital literacy, and anti-discrimination frameworks within a unified sustainability agenda. Embedding Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) principles into national curricula and teacher training programs is essential to cultivate the competencies defined under SDG 4.7—including critical thinking, empathy, and global citizenship. Universities in Montenegro increasingly incorporate civic education courses highlighting human rights, diversity, and tolerance, sometimes as stand-alone modules or embedded within broader social science curricula (projects like: Developing Human Rights Education at the Heart of Higher Education, etc.), At the same time institutions offer professional development workshops focusing on inclusive teaching strategies, multicultural sensitivity, and ethical classroom management. For example, future teachers often complete courses in social pedagogy and diversity awareness as part of their certification.

University administrators should prioritize designing curricula that formally embed tolerance and civic competencies and invest in regular faculty training on inclusive practices. Supporting campus-wide inclusion programs, such as mentorship for minority students and campaigns against discrimination, can foster a more welcoming university environment and position institutions in line with European standards and expectations.

Legal and institutional frameworks should be reinforced to protect minority rights and guarantee equitable access to education, employment, and participation in public life. Policy coherence between education, labour, and social sectors would help address the structural roots of intolerance identified in this study, particularly economic precarity and digital polarization.

Finally, public investment should prioritize community-level intercultural initiatives and participatory governance mechanisms—such as youth councils, civic forums, and local sustainability partnerships—that foster dialogue, strengthen social cohesion, and ensure that inclusion efforts remain both locally grounded and nationally coordinated.

4.5.2. Practical Recommendations

Practical actions to advance educational and societal sustainability can be implemented through a combination of pedagogical, digital, and community-based interventions.

First, the integration of inclusion, diversity, and equity (IDE) principles into national curricula—delivered through interactive, experiential, and inquiry-based learning—can strengthen key competencies for sustainable development. Embedding these principles at all levels of education supports the cultivation of empathy, civic engagement, and systems thinking as core sustainability outcomes.

Second, cross-sectoral digital literacy programs should be developed to promote critical and ethical media use, enabling young people to navigate misinformation and online polarization while fostering sustainability-oriented values and digital citizenship.

Third, social and emotional learning (SEL) should become a central objective of both formal and informal education, cultivating empathy, self-awareness, and conflict-resolution skills that directly reinforce tolerance and intercultural understanding.

Fourth, youth participation mechanisms—including councils, mentorship schemes, and intercultural exchange programs—should be expanded to encourage dialogue, co-creation, and collaborative problem solving across diverse groups. Such participatory spaces are key to building sustainable social cohesion and empowering young people as agents of change.

Finally, all initiatives should include continuous evaluation and feedback loops, ensuring that interventions remain evidence-based, scalable, and responsive to evolving societal challenges.

A few considerations should contextualise these findings. Because the data rely on self-reported attitudes related to sensitive issues such as nationalism, minority rights and gender diversity, responses may be shaped by social desirability and varying levels of willingness to disclose personal views. The online survey format may also have favoured students who are more digitally active or more comfortable interacting with such topics in web-based environments. These factors do not undermine the main patterns observed, but they suggest that the reported levels of tolerance should be interpreted with awareness of the broader social and methodological context.

5. Conclusions

This study provides one of the first empirical assessments of tolerance among higher education students in Montenegro, revealing a society positioned between progressive openness and enduring divisions shaped by economic insecurity and historical legacies. The findings indicate that education remains the strongest driver of tolerant attitudes, emphasizing its transformative potential in fostering empathy, intercultural understanding, and sustainability competencies aligned with Education for Sustainable Development (ESD).

Although the survey included limited indicators on digital media use, results suggest that online environments play an ambivalent role—supporting access to diverse perspectives while occasionally reinforcing ideological divides. This underlines the importance of strengthening digital literacy within higher education as a complementary tool for promoting reflective engagement and civic responsibility.

Economic marginalization continues to correlate with exclusionary attitudes, underscoring the need for policies that link social equity and sustainable development outcomes. Similarly, identity-related tensions reveal that historical narratives still shape perceptions of belonging, highlighting the potential of reconciliation-oriented and intercultural education.

Within the broader sustainability agenda, higher education institutions play a decisive role in embedding tolerance, empathy, and critical thinking into curricula and institutional practices. By systematically integrating these competencies through experiential, interdisciplinary, and participatory learning, universities can enhance their contribution to SDG 4.7 and advance the transformative goals of Education for Sustainable Development, fostering inclusive, cohesive, and sustainable societies. To monitor progress toward SDG 4.7, institutions should regularly review how global citizenship and education for sustainable development are embedded in national education policies, curricula, teacher education, and student assessment. Using SDG indicator 4.7.1, future tracking can assess advances in teaching human rights, cultural diversity, and sustainability across all educational levels.

Universities therefore remain key enablers of societal sustainability, translating the principles of Education for Sustainable Development into tangible learning experiences that prepare future citizens for intercultural coexistence.

In addition to its empirical insights, this study offers several contributions to the literature and practice. Theoretically, it strengthens current debates on tolerance by situating youth attitudes within well-established sociopsychological and sustainability-education frameworks. Methodologically, it provides a transparent, mixed-methods model for examining tolerance in small and transitional societies, integrating logistic regression with complementary attitudinal mapping. Practically, the findings offer clear guidance for higher-education and public-policy actors, highlighting how inclusive curricula, digital-literacy programs, and equity-oriented social policies can jointly advance tolerance and the broader goals of sustainable development.

These findings may also offer guidance for higher education institutions in other post-transition or multicultural contexts, where integrating intercultural dialogue, digital citizenship, and sustainability-oriented competencies into curricula can strengthen tolerance and support broader democratic and social-cohesion goals.

By grounding the analysis in both sociopsychological theory and sustainability education frameworks, this study not only advances scholarly understanding of tolerance in post-transition contexts but also provides actionable pathways for educators, policymakers, and institutions seeking to cultivate more inclusive and resilient societies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.P. and I.K.; methodology, I.K., I.P. and A.O.; software, I.P.; validation, I.K., A.G. and A.O.; formal analysis, I.K.; investigation, A.O., M.M. and A.G.; resources, I.K. and M.M.; data curation, I.K., A.O. and A.G.; writing—original draft preparation, I.P.; writing—review and editing, I.P., A.G. and I.K.; visualization, A.O.; supervision, I.P.; project administration, I.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Donja Gorica (approval code: UDG-EC-2021-04, approved on 15 April 2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Participation was voluntary, anonymous, and in line with ethical research guidelines.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. Data are not publicly available due to privacy and ethical restrictions.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the student organizations and youth networks in Montenegro that supported the dissemination of the survey. We also extend our appreciation to all participants who voluntarily contributed their time and perspectives. Special thanks go to the University of Donja Gorica (UDG) for institutional support throughout the research process.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ESD | Education for Sustainable Development |

| SDG | Sustainable Development Goal/Goals |

| EU | European Union |

| OECD | Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development |

| HEI | Higher Education Institution(s) |

| PCA | Principal Component Analysis |

| OR | Odds Ratio |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| RDI | Research, Development and Innovation |

| SEL | Social and Emotional Learning |

References

- Janmaat, J.G.; Keating, A. Are Today’s Youth More Tolerant? Trends in Tolerance among Young People in Britain. Ethnicities 2019, 19, 44–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayram Özdemir, S.; Özdemir, M.; Boersma, K. How Does Adolescents’ Openness to Diversity Change Over Time? The Role of Majority-Minority Friendship, Friends’ Views, and Classroom Social Context. J. Youth Adolesc. 2021, 50, 75–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, E.; Schönwälder, K.; Petermann, S.; Vertovec, S. Diversity Assent: Conceptualisation and an Empirical Application. Ethn. Racial Stud. 2024, 47, 3212–3236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulalic, A. Students’ Awareness and Participation in the Education for Peace in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Intellect. Discourse 2023, 31, 345–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matevski, Z.D.; Matevska, D.N. Identity and Tolerance among University Students in North Macedonia. In Proceedings of the Conference Culture and Identities 2020, Tokyo, Japan, 31 July 2020; University of East Sarajevo: Pale, Bosnia and Herzegovina, 2020; pp. 165–178. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Reimagining Our Futures Together: A New Social Contract for Education; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2021; ISBN 978-92-3-100478-0. [Google Scholar]

- Probst, L. Higher Education for Sustainability: A Critical Review of the Empirical Evidence 2013–2020. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuenyong, T. Management Strategies for Higher Education Institutions Based on the Principles of Education for Sustainable Development in the Lower Northern Region. J. Ecohumanism 2024, 3, 712–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, R.M.; Kemp, S.; Price, E.A.C.; Longhurst, J.W.S. Perspectives and Practices of Education for Sustainable Development: A Critical Guide for Higher Education; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2025; ISBN 9781032588018. [Google Scholar]

- Ignacio Gonzalez Arruti, C.; Jacinta Musalem Enriquez, A. Responsibility in Institutions of Higher Education: Education for Sustainable Development. Am. J. Appl. Sci. Res. 2022, 8, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiek, A.; Withycombe, L.; Redman, C.L. Key Competencies in Sustainability: A Reference Framework for Academic Program Development. Sustain. Sci. 2011, 6, 203–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rieckmann, M. Future-Oriented Higher Education: Which Key Competencies Should Be Fostered through University Teaching and Learning? Futures 2012, 44, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; Khan, A.M. A Phenomenological Study of Education for Sustainable Development in Higher Education of Pakistan. Pak. J. Educ. 2018, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ujeyo, M.S.; Najjuma, R. Sustainable Development in the Context of Higher Education; IGI: Antwerp, Belgium, 2022; pp. 211–232. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Sommier, M.; Vasques, A. Sustainability Education at Higher Education Institutions: Pedagogies and Students’ Competences. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2022, 23, 174–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Carracedo, F.; Romero-Portillo, D.; Sureda Carbonell, B.; Moreno-Pino, F.M. Education for Sustainable Development in Spanish Higher Education: An Assessment of Sustainability Competencies in Engineering and Education Degrees. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2022, 23, 940–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano, R.; Barreiro-Gen, M.; Pietikäinen, J.; Gago-Cortes, C.; Favi, C.; Jimenez Munguia, M.T.; Monus, F.; Simão, J.; Benayas, J.; Desha, C.; et al. Adopting Sustainability Competence-based Education in Academic Disciplines: Insights from 13 Higher Education Institutions. Sustain. Dev. 2022, 30, 620–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ujeyo, M.S.S. Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) in Higher Education. In Research Anthology on Preparing School Administrators to Lead Quality Education Programs; IGI Global: Antwerp, Belgium, 2021; pp. 986–1002. [Google Scholar]

- Bonilla-Jurado, D.; Zumba, E.; Lucio-Quintana, A.; Yerbabuena-Torres, C.; Ramírez-Casco, A.; Guevara, C. Advancing University Education: Exploring the Benefits of Education for Sustainable Development. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebire, R.H.; Isabeles-Flores, S. Sustainable Development in Higher Education Practices. Rev. Leng. Cult. 2023, 5, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, C.K.; Haufiku, M.S.; Tan, K.L.; Farid Ahmed, M.; Ng, T.F. Systematic Review of Education Sustainable Development in Higher Education Institutions. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Education for Sustainable Development Goals: Learning Objectives; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2017; ISBN 9789231002090.

- Allport, G.W. The Nature of Prejudice; Addison-Wesley Pub. Co.: Boston, MA, USA, 1954; ISBN 0201001756. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, S.; Ng, S.-M. Reducing Stigma Among College Students Toward People with Schizophrenia: A Randomized Controlled Trial Grounded on Intergroup Contact Theory. Schizophr. Bull. Open 2021, 2, sgab008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albuja, A.F.; Gaither, S.E.; Sanchez, D.T.; Nixon, J. Testing Intergroup Contact Theory through a Natural Experiment of Randomized College Roommate Assignments in the United States. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2024, 127, 277–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blalock, H.M. Toward a Theory of Minority-Group Relations; Capricorn Books: Jenkintown, PA, USA, 1970; ISBN 0399502343. [Google Scholar]

- Oskamp, S. (Ed.) Reducing Prejudice and Discrimination; Psychology Press: Oxfordshire, UK, 2013; ISBN 9781410605634. [Google Scholar]

- Yuk, J.; Shin, H. Refugees as Perceived Threat: College Students’ Attitudes towards Refugees in South Korea. Int. Migr. 2024, 62, 182–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inglehart, R. Post-Materialism in an Environment of Insecurity. Am. Political Sci. Rev. 1981, 75, 880–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inglehart, R.; Welzel, C. Modernization, Cultural Change, and Democracy: The Human Development Sequence; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2005; ISBN 0521609712. [Google Scholar]

- Tajfel, H.; Turner, J. Chapter 3 An Integrative Theory of Intergroup Conflict; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Thomsen, J.P.F.; Juhl, S.W.L. Contact Experiences Shape the Outcomes of Interethnic Differences: Elaborating Social Identity Theory. Ethnopolitics 2024, 23, 435–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genkova, P.; Groesdonk, A. Intercultural Attitudes as Predictors of Student’s Prejudices Towards Refugees. J. Int. Migr. Integr. 2022, 23, 1045–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezirow, J. Transformative Dimensions of Adult Learning; Jossey-Bass: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2000; ISBN 1555423396. [Google Scholar]

- Sahal, M.; Musadad, A.A.; Akhyar, M. Tolerance in Multicultural Education: A Theoretical Concept. Int. J. Multicult. Multireligious Underst. 2018, 5, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anugrah, D.S.; Supriadi, U.; Anwar, S. Multicultural Education: Literature Review of Multicultural-Based Teacher Education Curriculum Reform. Eurasia Proc. Educ. Soc. Sci. 2024, 39, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osin, R.V.; Roganova, A.E.; Medvedeva, I.A. Research of Ethnic Tolerance in the Youth Environment. Психoлoгия Психoтехника 2022, 4, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pariser, E. The Filter Bubble: What the Internet Is Hiding from You; Viking: Norway, Sweden, 2011; ISBN 014196992X. [Google Scholar]

- Metzler, H.; Garcia, D. Social Drivers and Algorithmic Mechanisms on Digital Media. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2024, 19, 735–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ying, Y.; Karim, A.M.; Mondol, E.P.; Helal, M.S.A. Influence of Digital Education to Uplift the Global Literacy Rate in the Age of Digital Civilization. Int. J. Acad. Res. Account. Financ. Manag. Sci. 2024, 14, 383–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Džankić, J. Montenegro’s Minorities in the Tangles of Citizenship, Participation, and Access to Rights. JEMIE 2012, 11, 40. [Google Scholar]

- Vukadinovic, S. The Education Situation of Roma in Montenegro. In Lifelong Learning and the Roma Minority in the Western Balkans; Emerald Publishing Limited: Leeds, UK, 2023; pp. 109–124. [Google Scholar]

- Sterling, S. Transformative Learning and Sustainability: Sketching the Conceptual Ground. Learn. Teach. High. Educ. 2011, 5, 17–33. [Google Scholar]

- Ministarstvo Prosvjete; Nauke i Inovacija. Strategija Reforme Obrazovanja za Period 2025–2035: Nacrt; Ministarstvo Prosvjete: Podgorica, Montenegro; Nauke i Inovacija: Podgorica, Montenegro, 2024; pp. 1–91. [Google Scholar]

- Veidemane, A. Education for Sustainable Development in Higher Education Rankings: Challenges and Opportunities for Developing Internationally Comparable Indicators. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephan, W.G.; Renfro, C.L.; Davis, M.D. The Role of Threat in Intergroup Relations. In Improving Intergroup Relations; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008; pp. 55–72. [Google Scholar]

- MONSTAT. Statistical Yearbook of Montenegro; Statistical Office of Montenegro: Podgorica, Montenegro, 2021; ISBN 0354-2076. [Google Scholar]

- Törnberg, P. How Digital Media Drive Affective Polarization through Partisan Sorting. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2207159119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muhonen, T.; Timonen, L.; Väänänen, K. Fostering Education for Sustainable Development in Higher Education: A Case Study on Sustainability Competences in Research, Development and Innovation (RDI). Sustainability 2024, 16, 11134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meleshkina, E.Y.; Pomiguev, I.A. The Situational Nationalism: A New Age of Nation and State Building in Montenegro? RUDN J. Political Sci. 2023, 25, 778–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlović, S. Literature, Social Poetics, and Identity Construction in Montenegro. Int. J. Politics Cult. Soc. 2003, 17, 131–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staub, E. The Roots of Goodness and Resistance to Evil: Inclusive Caring, Moral Courage, Altruism Born of Suffering, Active Bystandership, and Heroism; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2016; ISBN 019538203X. [Google Scholar]

- Žiga, J.; Turčilo, L.; Osmić, A.; Bašic, S.; Džananović Mirasčija, N. Youth Study: Bosnia and Herzegovina; Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung: Berlin, Germany, 2015; ISBN 9789958884382. [Google Scholar]

- Banovac, B.; Katunarić, V.; Mrakovčić, M. From War to Tolerance? Bottom-up and Top-down Approaches to (Re)Building Interethnic Ties in the Areas of the Former Yugoslavia. Zb. Pravnog Fak. Sveučilišta Rijeci 2014, 35, 455–483. [Google Scholar]

- Special Eurobarometer 535 Discrimination in the EU Age. Available online: https://europa.eu/eurobarometer/surveys/detail/2972 (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Education at a Glance 2024; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2024; ISBN 9789264514256.

- OSCE Mission to Bosnia and Herzegovina. “Two Schools Under One Roof”: The Most Visible Example of Discrimination in Education in Bosnia and Herzegovina; OSCE Mission to Bosnia and Herzegovina: Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Stoeckel, F.; Ceka, B. Political Tolerance in Europe: The Role of Conspiratorial Thinking and Cosmopolitanism. Eur. J. Political Res. 2023, 62, 699–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostojić, V. Youth Study Montenegro 2024: Navigating Uncertainty amidst Traditional Constraints; Centre for Civic Education (CCE): Podgorica, Montenegro, 2024; ISBN 9789940440749. [Google Scholar]

- European Education; Culture Executive Agency. Learning for Sustainability in Europe: Building Competences and Supporting Teachers and Schools; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wals, A.E.J. Beyond Unreasonable Doubt: Education and Learning for Socio-Ecological Sustainability in the Anthropocene; Wageningen University: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2015; ISBN 9789462573697. [Google Scholar]

- Hammer, T.; Lewis, A.L. Which Competencies Should Be Fostered in Education for Sustainable Development at Higher Education Institutions? Findings from the Evaluation of the Study Programs at the University of Bern, Switzerland. Discov. Sustain. 2023, 4, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).