Abstract

The construction industry accounts for a significant share of CO2 emissions in Europe and Denmark. Renovation can reduce these emissions since it is significantly less carbon-intensive than new construction. Denmark uses life-cycle assessment (LCA) to evaluate the climate impact of construction, but lacks standard mandates for renovation, leading to inconsistent LCA approaches. This research examines LCA methodologies for building renovations in Denmark, developing a tailored approach that draws on existing approaches outlined in the Danish Building Regulations and various reports from both private and public entities. It assesses different renovation depths (minor, moderate, deep) and preservation interventions. A case study of an actual renovation project in Denmark is used to analyse the energy and environmental impacts. The results indicate that LCAs for minor renovations are not methodologically viable due to their limited scope. In contrast, LCAs of moderate and extensive renovations yield meaningful insights, showing potential reductions of over 50% in energy use and 20–50% variations in overall CO2 emissions across scenarios. In addition, it is observed that energy renovations (i.e., adopting measures to improve the energy efficiency of buildings, especially in moderate and deep renovations) can reach a point at which further improvements do not significantly reduce emissions. Future research should expand LCA applications to a broader range of renovation cases and refine standardised methodologies. Additionally, studies should investigate climate benchmarks and incorporate social and economic factors shaping renovation decisions.

1. Introduction

Today, one of humanity’s major problems is man-made climate change, as seen in changing temperatures and weather patterns. Climate change relates to the greenhouse effect, which causes Earth to warm up. The most significant cause of climate change is CO2 emissions, which accumulate in Earth’s atmosphere [1]. One of the biggest CO2 emission culprits is the buildings and construction sector, accounting for 39% of global carbon emissions, with operational emissions (energy for heat, cooling, and power) accounting for 28% and materials and construction accounting for the remaining 11% [2]. Due to this significant impact, the building and construction industry has a major focus on reducing CO2 emissions [2]. To avoid irreversible climate change, the construction sector must achieve a 65% reduction in embodied carbon emissions by 2030 and become carbon neutral by 2040 [3].

A city the size of Paris is being built every week [4], resulting in significant material consumption and waste generation through both construction and demolition. In the European Union (EU), this expansion of the built environment results in approximately one-third of the materials consumed being used in construction [5], and 25–30% of all waste originates from construction and demolition [6]. Furthermore, 42% of the total energy consumption in the EU and 35% of the greenhouse gas emissions are caused by the building and construction industry [5]. In addition, about half of the building stock in the EU is ageing and was not built to withstand climate change, while also being inefficient in the use of energy [5]. Out of the current European building stock 86% will still be used in the future [5]. The ageing building stock poses a challenge to both energy use and human health and well-being, as the current European building stock is 75% energy inefficient, and older building mass also entails poorer living conditions [5]. These poorer living conditions are already evident today, as 15.5% of Europeans live in substandard housing, e.g., with leaky roofs, rotten window frames or floors, or damp walls, floors, and foundations [5]. To address both challenges, energy-efficient building renovations are necessary, but they are progressing at a slow pace.

Renovation is a key solution to reducing the environmental impact of the building sector in Europe. The EU has launched a renovation wave [7], as part of the EU Commission’s European Green Deal, which aims to improve energy efficiency, deliver better living standards for Europeans and boost the economy [8]. Through the renovation of the European building stock, the building energy use can be lowered, its reliance can be increased [9], and the average lifespan can be extended, as the average lifespan of a European building is 25–30 years, compared to the global average of 39 years [6]. As a result of the EU renovation wave, it is expected that 35 million buildings will be renovated by 2030 [10].

Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) [11,12] is a valuable tool to investigate the extent to which renovating the existing building stock can potentially reduce greenhouse gas emissions, as well as other environmental impact indicators such as biodiversity [13]. LCA in building renovation helps assess the environmental impacts throughout a building’s lifecycle, from raw material extraction to construction, use, and eventual disposal. Applying LCA during the renovation process enables stakeholders to identify opportunities for improvement, such as selecting sustainable materials, optimising energy efficiency, and minimising waste.

In Denmark, LCA and climate requirements for building projects were introduced in January 2023, aiming to limit associated CO2 emissions. Renovation, restoration, and transformation projects are not included in these requirements, as they only cover new construction [14]. There is currently no standardised LCA approach in this regard, which causes problems, including a weak basis for comparing renovation projects and potential renovation interventions. Renovations of existing buildings can be carried out in multiple ways. This can include minor interventions/measures to a building (such as minor interior renovations) to more major interventions (such as window replacement, insulation improvement, roof replacement/repair, and HVAC system update), broadly referred to as minor, moderate, deep, and restoration renovations (the definition of renovation depths follows the work by Kamari et al. [15]). This wide array of renovation options complicates the LCA process. Consequently, this study aims to achieve the following:

- (a)

- Examine the existing literature and methodologies on Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) specifically within the context of renovation projects,

- (b)

- Develop a tailored LCA methodology designed for the assessment of various renovation interventions (or so-called renovation depths), and

- (c)

- Evaluate the energy and environmental implications associated with varying building renovation scenarios through an actual building renovation case study conducted in Denmark.

This paper comprises six sections: Introduction, Background, Methodology, Case Study, Results, Discussion, and Conclusions. Section 2 provides an overview of the current state of building renovation and LCA in Denmark. Section 3 outlines the LCA methodology employed in the case study presented in Section 4. Section 5 summarises the results according to the specified renovation depths. Section 6 discusses the key findings and concludes with recommendations for future research.

2. Background

Renovation work enhances the value of the building, improving its attractiveness, distinctiveness, and dignity [16]. The extent of renovation work depends on the age of the building, with older buildings requiring more work. Renovating an older building can breathe new life into it while preserving its character and original features. During its renewal, the building may either retain its original function or undergo a change, making the renovation a transformation project. Through transformation, an existing building can be given a new life and function, while preserving evidence of climate, culture and history [17]. The transformation can be an environmentally friendly and resource-efficient solution through the reuse of existing structures and elements, while also extending the building’s lifespan [18]. An added benefit of renovation over new construction is the use of fewer natural resources, resulting in a lower environmental impact [19].

In building conservation, repair is an integral part of the process, but it also fosters an understanding of the building’s historical context and value, informing future decisions. Work carried out should maintain characteristics and value with as little harm as possible, contributing to the importance of knowledge of conservation practices and policy [20]. In the restoration of a historic building, it is a challenge to preserve and maintain the integrity without altering or compromising it, highlighting the importance of knowledge and education regarding conservation practices and policies [21,22].

In the renovation field, “energy renovation” refers to the process of renovating a building to reduce its energy consumption and overall environmental impact [23]. Existing buildings may have been constructed under less stringent building regulations than those in effect today, resulting in higher energy consumption compared to newer buildings. The most considerable potential for reducing energy use through energy renovation lies in buildings built before 1980, which have not undergone additional insulation since that time [24]. Renovation is therefore a tool to minimise the climate impact through the reduction in energy consumption, e.g., by energy renovation through additional insulation, replacement of windows or installation of solar cells [25].

In Denmark, there are around 7000 listed buildings and approximately 350,000 buildings worthy of renovation [26]. During the last 10 years in Denmark, on average, more than three houses built before 1929 have been demolished every day [27]. A reason for demolishing older buildings is a combination of economic considerations, as renovations are often perceived as expensive, and a need to demolish older buildings to make space for new ones. There are two categories of conservation buildings, categorised by the Danish Agency for Culture and local authorities. If only the exterior is protected, the protection class is referred to as “worthy of preservation”; if the whole building is protected, then it is classified as “listing protection” [28]. The tendency to demolish and rebuild comes with both environmental and cultural consequences, as the production of building materials emits CO2 equivalents. At the same time, demolition also negatively impacts cultural heritage, as it erases a significant part of Denmark’s architectural history. For example, old villas have historical details and styles that modern houses often lack [27]. Maintaining and renovating the current building stock will contribute to keeping the condition of older buildings adequate, preventing them from falling into disrepair or outliving their functional lifetime, as 30% of building demolitions in Denmark are due to poor condition, with the justification for demolition often involving challenges with the layout, interior design, size of the houses, and budget [21].

Braae and Stilling [22] believe that sustainability should be a parameter for building renovation, where the existing building’s CO2 impact is assessed, which serves as the basis for determining whether it should be preserved. For example, buildings from the 1950s have a significant CO2 footprint due to the materials used. For buildings from this era, it is better to renovate them than demolish them from a CO2 perspective [22]. There is also support in Denmark for preserving buildings, driven by an interest in maintaining good craftsmanship, the details, and the history behind them. In local areas, old buildings give identity and pride. There has also been a foundation created, the Danish Cultural Heritage Foundation, which works with buildings saved from demolition [29].

2.1. Environmental Life Cycle Assessment (LCA)

The building and construction industry is responsible for 39% of global CO2 emissions, with 11% being embodied carbon originating from building materials and the construction process, and 28% being operational carbon [30]. Operational carbon refers to emissions generated by the building’s energy use, including heating, cooling, and lighting. Embodied carbon emissions include those from the design, production, and deployment of materials. Strategies commonly used to minimise embodied carbon include avoiding unnecessary extraction and production of materials, shifting to regenerative materials, and improving the decarbonisation of conventional materials [31]. Operational carbon is a significant contributor to a building’s climate impact, and the industry has focused on reducing it over the last two decades. With a focus on reducing operational energy, embodied carbon will account for a greater share of a building’s total emissions in the future. Currently, operational accounts for around 60%, while materials account for 40% [32]. It is predicted that, in the coming decades, it will be possible to reduce the total operational emissions of the building and construction sector by 50% to 75%. Leading to the further prediction by 2030, 74% of total carbon emissions from buildings constructed after 2020 will be associated with the embodied carbon [33].

To evaluate the environmental impacts of a building over its entire lifespan, the LCA method for construction works [11] is employed, utilising data-driven tools [34,35]. It allows assessing emissions from both operations and embodied carbon, while indicating the stage of the building’s life cycle to which each is associated. The life cycle of the building is divided into phases, from resource extraction (A1) to the disposal (C4) or recycling (C3) of materials [32]. LCA is a well-known methodology for assessing buildings, but the methods themselves can vary widely in terms of adoption and implementation across countries. This has the effect that comparing the basis between countries can lead to inconsistent outcomes and make it difficult to establish a standard benchmark for environmental impacts, thereby comparing projects with one another [36].

Existing studies have examined LCA methodologies in terms of scope, including life cycle stages, gross floor area definition, reference study period, and the level of detail between schemes regarding building element groups, as well as prerequisites for energy mixes and impact categories of life cycle assessments [36,37,38]. The studies [36,37,38] found significant variations between countries, highlighting the flexibility of the EN 15978:2011 standard [11] guideline, as it contains minimal scope definitions, which provide the basis for different interpretations and applications. An example of this is seen in the definition of gross floor area, which can be defined as either including or excluding the external wall thickness. The European and international standards for LCA (i.e., EN 15978:2011 [11]) do not specify the functional unit on which the LCA is based, but the most commonly applied approach is to use the floor area [38]. The widely applied reference study periods generally range from 50 to 60 years; cases where 75–100 years are used also exist, depending on the building type and country of assessment [36,37,39]. The selection of the reference study period is of great importance, as it directly affects emissions from the building use phases (B1–B7) and the balance between upfront and operational carbon. This occurs because longer reference study periods assign greater weight to operational carbon, while shorter reference study periods assign greater weight to upfront carbon.

2.2. LCA in Denmark

In 2021, the Danish government reached a political agreement on a national strategy for sustainable construction, which introduced requirements for LCA calculations for new construction exceeding 1000 m2 and an associated limit value for CO2 emissions from the beginning of 2023. In 2024, a political agreement was made to decrease the limit values from 2025 onward [40].

The BR18 (i.e., the Danish Building Regulations) LCA calculations must be carried out for all new buildings, where an energy framework calculation has been performed [41]. The calculation is based on a reference study period of 50 years. The functional unit for the calculation is kg CO2 equivalents per m2 per year (kg CO2-eq./m2/year), based on the gross floor area definition in BR18 and the reference study period. The following modules of the life cycle must be included in the calculation: modules A1–A3, B4, B6, C3, and C4, which are reported as one coherent number to comply with the regulations. The D module is reported individually, with no limit value. The modules have been defined in BR18, clauses 297–298 [41]:

- A1: Raw materials.

- A2: Transport.

- A3: Manufacturing.

- B4: Replacement (excluding transport and replacement process).

- B6: Energy consumption for operation.

- C3: Waste pre-treatment.

- C4: Disposal.

- D: Potential for reuse, recycling and other recovery (must be kept separate and is therefore not included in the main calculation).

The limit value was previously defined only for new buildings with a heated floor area exceeding 1000 m2. With the limit value being 12.0 kg CO2-eq./m2/year [41]. As of July 2025, the limit values were updated to accommodate various building typologies and all newly constructed buildings. Table 1 shows the limit values for new construction, which will be gradually tightened from 2025 to 2029 compared to the supplementary agreement from 2024. In 2027, the tightening is approximately 10%, while in 2029, it is approximately 11%, relative to the preceding limit value [41]. Table 2 presents the limit values for the low-emission class, which are approximately 18% below the 2025 limit value and 21% and 25% below the 2027 and 2029 limit values, respectively [41].

Table 1.

New standard climate requirements for buildings in Denmark [41].

Table 2.

New low-emission class requirements for buildings in Denmark [41].

2.3. LCA for Building Renovations in Denmark

Although it is not mandatory to perform LCAs for building renovation projects in Denmark, explorations and recommendations on the subject have been developed by major/flagship private and public entities in the Danish building industry. The following subsections present an overview of these methods.

2.3.1. Rambøll’s LCA Approach for Building Renovation

A report by Rambøll shows that renovation is the most beneficial option, both environmentally and economically, compared to demolition and new construction. The assessment is based on an analysis of 16 buildings, which span single-family houses, apartment buildings, public buildings, and commercial buildings [42].

The functional unit used to assess the environmental impact of the renovations suggested by Rambøll aligns with the functional unit in BR18, which is kg CO2-eq./m2/year for a 50-year reference period. The lifetime for individual building materials is based on the SBi instruction 2013:30 [43]. The Danish tool for calculating LCA, called LCAbyg [44], is used in this study, and the Environmental Product Declarations (EPDs) [45,46] are a combination of generic data from ÖKOBAUDAT [44] and industry-specific EPDs. The energy use in B6 is calculated using the Danish energy framework method [45]. In addition, the SBI 60 Building LCA Cases climate impact over 50 years has been used to simulate the new build scenario [46].

The proposed approach assesses the environmental impact of three levels of renovation and compares them with that of new construction. The definitions of the three degrees of renovation are as follows:

- -

- Level 0: Basic construction

- -

- Level 1, Roof (R): Renovation is being carried out for the roof

- -

- Level 2, Roof and exterior wall (RW): Renovation of both the roof and exterior walls is being carried out, including the replacement of windows

- -

- Level 3, Roof, exterior wall, and installations (RWI): Comprehensive renovation of roof, exterior walls, windows, and installations.

- -

- New building (N): Existing building is demolished, and a new one is built.

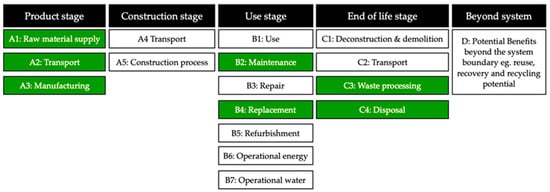

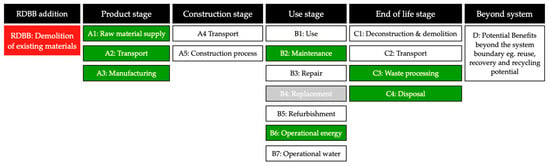

Figure 1 illustrates an overview of the LCA modules included in the assessment.

Figure 1.

Investigated scenarios and the associated LCA approach based on EN15978 (adapted from [42]).

The proposed LCA methodology does not account for the impacts of the existing building, as demolition or renovation of existing buildings is not included in the new construction and is therefore considered out of scope. The A1–A3 includes replacing the building component in renovation cases, whereas the new construction case involves producing all new materials. End-of-life (C3 and C4) for the renovation refers to the end of the service life of the renovated building parts, whereas for new construction, it is the end of life of the entire new building.

The study also includes a sensitivity analysis, in which the system boundaries are expanded to include C3 and C4 for the existing building parts, as illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

LCA approach for sensitivity analysis, using existing building parts (adapted from [42]).

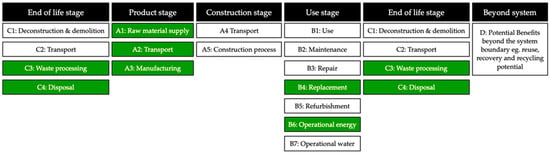

This change in system boundaries means that the operation remained the same, but the impact of the building parts became more pronounced. The study concluded that renovation has the potential to lower environmental impact than new construction, and this conclusion remained unchanged despite the expanded boundaries explored in the sensitivity analysis, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Comparison of GWP impact following the two LCA approaches applied in the Rambøll study (reproduced from [42]).

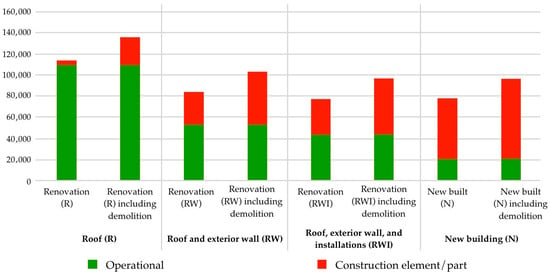

2.3.2. The Danish Association of Construction Clients’ LCA Approach for Building Renovation

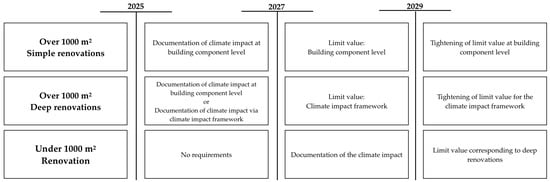

The Danish Association of Construction Clients [47] has created recommendations for climate-related renovation requirements based on the expected development of Danish Building Regulations from 2025 to 2029. Their recommendations are divided into three parts: (1) requirements for climate impact and verification method, (2) handling of materials and operation, and (3) limit value. Based on this, an associated LCA approach for renovation projects has been proposed. It includes LCA modules, building components, and calculation methods. In addition, they are being developed in line with anticipated changes to the building regulations, becoming increasingly comprehensive over time. Figure 4 illustrates the suggested LCA modules and the timeframe for their implementation.

Figure 4.

LCA approaches from 2025 to 2029 based on renovation size and scope (adapted from [47]).

Materials are categorised into three groups, where the remaining life of existing materials is not included in the LCA calculation:

- (1)

- The retained and existing materials in the building that are included in module A1–A3,

- (2)

- The demolished and disposed materials that are included in modules C1–C4, or included in D, if they are reused and recycled, and

- (3)

- The new materials that are added are part of A, B, C, and D modules.

The modules recommended for inclusion in the LCA are marked in green in Figure 4. The included modules become more extensive over time and vary across different renovation types. The recommendation distinguishes between simple and deep renovations for buildings exceeding 1000 m2 and renovations of buildings under 1000 m2. Simple renovations involve the complete or partial reconstruction or replacement of one or two building parts. From this perspective, installations are viewed as a single building component. Deep renovation involves the complete or partial reconstruction or replacement of three or more building parts. Simple renovations examine the building at the part level in terms of requirements, while deep renovations assess the building at the part or building level in terms of the climate load framework [47]. For buildings below 1000 m2, there is no distinction between simple and deep renovations.

Energy for operation, module B6, is not included in the LCA recommendations for 2025, as there are no requirements in the BR18 for energy calculation in renovation, such as compliance with heat transfer coefficient (U-value) or other component requirements in the regulations. The reason to exclude B6 in the LCA is to avoid adding any extra “burden” to the project after the renovation.

For the LCA from 2027 to 2029, module B6 is included. The recommendations state [47] that it is a personal choice to document energy demand before and after renovation using the climate impact framework, and to document energy demand from 2025 to 2027. It is assumed that an energy framework will be implemented for deep renovations from 2027 onward, driven by the growing use of energy performance certificates and the upcoming requirements under the European Energy Performance of Buildings Directive (EPBD) and the European Energy Efficiency Directive (EED). This will include modules B6, A4, and A5, which will incorporate the new materials to be included in the LCA from 2027.

The recommendations further suggest that the LCA approach for renovations should mirror that for new construction. This means that if LCA for new construction includes A4, A5, B1, or B2, then these modules should also be included in the LCA for renovation. The report emphasises that analysing LCAs is necessary to provide a basis for developing requirements. Additionally, an investigation should be conducted into the importance of individual phases and modules in the overall LCA in relation to climate savings potentials, to determine which phases and modules should be included in the assessment for renovation projects [47].

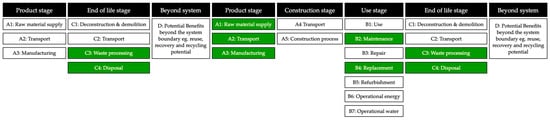

Regarding the third recommendation, Figure 5 presents the suggested limit values and documentation requirements for 2025 to 2029. It is recommended that there should be no limit values from 2025 to 2027. Still, a documentation requirement should be implemented, allowing stakeholders to start documenting without having to meet any limit values. Hereby, the association stresses that, from 2025 to 2027, a robust database can be built to establish valid limit values that account for the different characteristics of renovation, including the depth and size of the project [47]. From 2027 onward, renovations of buildings over 1000 m2 should meet the limit values. Buildings under 1000 m2 should start documenting their climate impact from 2027 and meet the limit values by 2029. Suggestions for limit values on a component level have not been proposed as of the fall of 2025.

Figure 5.

Limit value for climate impact (according to [47]).

2.3.3. Realdania’s LCA Approach for Building Renovation

Realdania By & Byg has investigated the LCA of renovation to account for all relevant parameters, e.g., house type, consumption, construction date, etc. Based on their studies, they introduce three approaches/scenarios regarding the LCA scope for renovations [48].

The first approach involves comparing demolition, new construction, and renovation. The method focuses on the decision of whether to preserve and renovate the building, rather than demolish it. The LCA modules included in this approach mirror those in LCAs for new buildings, per BR18, as shown in Figure 6. The approach suggests performing an LCA for both renovation and new construction, enabling a direct comparison of alternatives. The LCA for the renovation includes modules A1–A3, B4, B6, C3, and C4. It is further proposed to include the emissions from the waste management of materials removed from the building as part of the renovation. These are the C3 and C4 modules marked in the left part of Figure 6.

Figure 6.

LCA phase delimitation for scenario 1 of a demolition and new construction versus renovation (adapted from [49]).

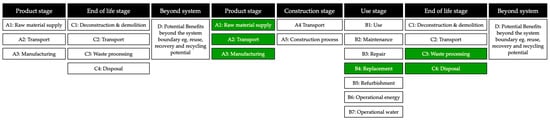

The second scenario developed by Realdania converts LCAs for the renovation of individual building parts. Following this method, the LCA is performed only for the building components added or replaced during the process. The inclusion of modules follows the guidelines in BR18, except that building energy use (module B6) is omitted from the calculation. Figure 7 illustrates an overview of the modules included.

Figure 7.

LCA phase delimitation for scenario 2 for renovation of individual building parts (adapted from [49]).

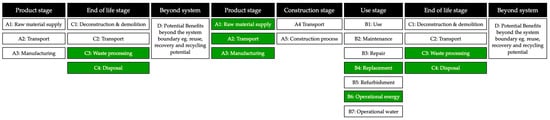

The third scenario focuses on an LCA approach for comparing major building renovation scenarios. The approaches strongly resemble the suggestions in Scenario 1, with the addition that modules B4, B6, C3, and C4, which utilise materials already in the building, are included in the reported results. The included modules are presented in Figure 8. This method provides more detailed LCA calculations and analysis than method 2 [48].

Figure 8.

LCA phase delimitation for scenario 3 for a larger renovation project (adapted from [49]).

2.3.4. Realdania’s LCA Approach for Conservation and Restoration

Realdania By & Byg has also investigated LCA methods for the transformations and restorations of historical buildings [50,51], with the method still under development. The study employs the same methodology for transformations and restorations, utilising the concepts to distinguish between whether the building retains its original function (restoration) or if it undergoes a change in function (transformation) [50,51].

The proposed LCA methodology includes selected modules from the European EN 15978 standard. The modules included in the LCA approach are A1–A3, B2, B6, C3, and C4, with C3 and C4 added for the materials removed from the building during the renovations. The modules are illustrated in Figure 9. The proposed method differs from other approaches for both new construction and renovation, as it uses B2 rather than B4. This methodological choice is made based on Realdania By & Byg, which is developing the method to apply to the building stock it owns. As the building owners, they can ensure continuous maintenance of the buildings, thereby mitigating the need for replacements [50,51].

Figure 9.

LCA approach for building conservation and restoration, where the dark green and red box is part of the approach (according to [51]).

2.4. Practical Gaps

In Denmark, the lack of mandatory requirements for performing LCAs on building renovations poses a significant challenge for consistent environmental assessment practices. Without regulatory enforcement, stakeholders may not prioritise conducting LCAs, thereby undermining the potential for informed decision-making on sustainable practices in the building sector. Moreover, the approaches developed by private and public entities often overlook the impacts of existing buildings in their assessments, potentially leading to a misleading comparison of the environmental costs of demolition versus renovation. This gap suggests that the true environmental footprint of renovation efforts may be underestimated, raising questions about the overall sustainability of current building practices.

The recommendations proposed by the Danish Association of Construction Clients highlight an evolving landscape for LCA methodologies, emphasising a transition toward more comprehensive and standardised approaches. However, the dynamic nature of these recommendations creates uncertainty regarding their implementation and enforcement, leaving stakeholders unsure of how to navigate the shifting requirements. Furthermore, excluding operational energy use from the initial LCA framework in the early years limits the ability to assess the full extent of energy impacts throughout a building’s lifecycle. This oversight underscores the need for a more integrated approach that incorporates energy considerations into the LCA process in future iterations of the requirements.

Finally, the variability in LCA methodologies across organisations, such as Rambøll, the Danish Association of Construction Clients, and Realdania, can complicate direct comparisons of their findings. This inconsistency may hinder the establishment of a unified understanding of best practices within the industry. Additionally, the lack of specifics regarding documentation requirements and limit values in the recommendations further adds to the confusion for stakeholders, necessitating a robust framework for gathering climate impact data. As the industry moves toward incorporating comprehensive metrics and analyses, establishing clear component-level limit values will be crucial to ensure that the nuances of material impact on renovations are effectively understood and addressed.

3. Materials and Methods

In this section, Section 3.1 defines the renovation depths applied in this study, and Section 3.2 and Section 3.3 introduce the LCA methodology adopted.

3.1. Renovation Depth

The proposed LCA methodology includes variations in scope depending on the degree of renovation (i.e., renovation depth). To differentiate the degree of renovation, the work builds upon the definitions of renovation depths by Kamari et al. [15], where renovation depths are separated into minor, moderate, and deep renovation scenarios, and are defined as follows:

- -

- Minor renovation: is the smallest intervention, characterised by a low ambitious renovation depth. This can include renovation of only the exterior walls and windows.

- -

- Moderate renovation: is a mid-level approach, involving basic interventions. A complete renovation can be carried out at this level, with three standard types of energy-efficient solutions (passive, active, and Renewable Energy Sources–RES) available.

- -

- Deep renovation: is the most intensive type of renovation, where the ambition is significantly higher compared to minor and moderate renovations. The renovation is expected to significantly improve energy efficiency.

In addition to the three renovation depths defined by Kamari et al. [15], this work introduces a fourth renovation type, referred to as restoration renovation, as follows:

- -

- Restoration renovation: is to preserve old buildings without altering or compromising their original design [52].

The perspective of differentiating renovations by depth aligns with the approach in BR18, where different building types have different benchmark values. This is underlined by the following quote from the supplementary agreement regarding the Danish building regulations [53]: “The parties to the agreement recognise that not all building types emit the same amount of CO2-eq./m2 and that the potential and opportunities for reducing climate impact are different”. The approach of applying variations in the LCA methodology is further supported by existing exploration of LCA for renovation [44,45,46,47].

3.2. LCA Methodology

The following sections outline the methodological choices made in the LCA calculation.

3.2.1. Reference Study Period

The study applies a 50-year reference study period (RSP) across all renovation depths. This aligns with the RSP commonly used in BR18 and existing renovation LCA methodologies [39]. The renovation aims to extend building life, but the 50-year RSP inherently limits the analysis horizon and fails to reflect the long-term preservation goals of historic buildings. Instead, it provides a practical framework for assessing CO2 emissions within a manageable timeframe.

The choice of a 50-year RSP is based on methodological uncertainties. Longer periods (80–120 years) correspond to the technical lifespan of buildings but introduce significant drawbacks. As Rasmussen et al. [54] discuss, longer horizons increase uncertainty in material production and end-of-life scenarios, with replacement impacts rising by 50% between 80 and 120 years. Moreover, responsibility for environmental impacts becomes ambiguous over extended periods (e.g., ownership changes within a 100-year RSP).

Given these concerns and the established Danish practice of applying a 50-year RSP in both renovation and new construction [41], this timeframe was adopted. While it does not reflect the actual building lifetime, it provides a consistent and comparable basis for evaluating environmental impacts. Even for historic buildings intended for long-term preservation, a 50-year RSP remains appropriate due to the uncertainties associated with longer horizons.

3.2.2. Functional Unit

The functional unit in the study is kg CO2-eq./m2/year, for the 50-year reference period. The unit is thereby aligning with commonly applied functional units in building LCA methodologies [38,39,42,47].

3.2.3. LCA Modules

The modules included in this study are A1–A5, B4–B5, C3 and C4, with the addition of the B6 module if an associated energy framework calculation has been carried out for the assessed renovation scenarios. The addition of B5 to the calculation is due to the application of OneClickLCA as the calculation tool (see Section 3.2.4). OneClickLCA [55] does not allow for the separation of B4 and B5 in the calculations, and both modules are therefore included. The modules included align with both commonly used approaches [39] and BR18. The alignment with these methodologies supports the comparison of results between projects.

Furthermore, energy consumption (B6) is calculated via the approach outlined in BR18 (Danish Building Regulations), utilising the tool Be18 (i.e., the Danish tool for monthly quasi-steady state calculation of the energy requirements in compliance with the building regulations) [56]. The calculation is based on heat transfer coefficients (U-values) and the heat losses (Psi-values) for the building envelope, along with information on shading, ventilation, and internal heat supply. It excludes domestic hot water, mechanical cooling, and technical systems.

3.2.4. Tool and Tool Settings

The LCA calculations are performed using the internationally recognised OneClickLCA tool [55], a widely utilised tool for both product-level and whole-building LCA analyses (using the student licence for writing the master’s thesis provided to the lead author), with the calculation tool, “Level(s) life-cycle assessment (EN15804 +A1)”. Calculations are performed between 5 May 2025 and 5 June 2025. In using the tool, the following specifications are set for the calculations:

- -

- Service life values for materials are set to be the same as the technical service life. Comparable materials are therefore set to have the same lifespan.

- -

- Transportation distance default values for materials are disregarded, due to there being no specific geographical location, as the case study is seen as generic. There is no set of defaults for the distance and transport mode for transporting materials from the manufacturer to the construction site. This influences the accuracy of A4.

- -

- Material manufacturing localisation is disabled, so the Global Warming Potential (GWP) of generic materials are not adapted based on the country of origin.

- -

- End of life calculation method: The default is market scenarios, user-adjustable and is the recommended version by [57], where C1–C4+D emission is based on material type and current market practices.

Quantities are imported from Revit 2024 using the OneClickLCA plug-in. The calculations are afterwards performed in the cloud version of OneClickLCA.

3.2.5. Methodological Limitations

The modules applied in the calculations are derived from the renovation scenarios outlined in Section 3.1. The LCA excludes the remaining life of existing building materials, as their associated emissions belong to the building’s pre-renovation life cycle and are omitted to avoid double-counting. This treatment of reused materials aligns with BR18 requirements for assessing environmental impacts in new construction [40]. Similarly, the study does not evaluate the load-bearing capacity of the static system, since the renovation scenarios do not significantly alter structural performance, consistent with clause 495 in BR18 [44] and related regulatory guidelines in Trafik Bygge-og Boligstyrelsen [58]. Moreover, it has to be underlined that, in this study, we assume that for the renovation of buildings with historical or cultural values (names as “listed for protection [59]” and “worthy of preservation [59]”), alterations that may impact the integrity of the building in terms of serviceability limits, are aligned with the requirements enforced by the Agency for Culture and Palaces (for “listed for protection [60]”) and local municipalities (for “worthy of preservation [59]”) in Denmark.

Uncertainties are addressed by limiting the scope of included stages; for example, B2 and B3 are excluded due to insufficient data. No reservation is made for the remaining lifetime of retained materials, as this varies across buildings and is difficult to determine. Arkitema, COWI, BUILD Aalborg Universitet and Rådet for Bæredygtigt Byggeri [48] emphasise the need for standardised methods to establish a uniform basis for incorporating remaining lifetimes in LCA calculations. Including remaining life would provide a more representative picture of renovation projects, particularly in relation to demolition (B4) and waste treatment (C3–C4) at year 50, as highlighted by Realdania [61]. However, the expected remaining life of demolished materials at year 0 is excluded. Given the absence of industry-wide standards and limited information on the condition of existing elements, this study does not apply reservations for remaining life.

3.3. LCA Methodology for Individual Renovation Scenarios

Scenarios are set up by category: minor, moderate, deep renovation, and restoration, with the first three building on each other, increasing the level of renovation intervention. The system boundary for the renovation depths, moderate, deep and buildings worthy of preservation, uses the cradle-to-grave system boundary with options, as removal of old materials during renovation is assessed. Minor renovations and listed renovations do not account for the existing materials; therefore, the cradle-to-grave system boundary is used. The methodological choices for each category are presented below.

3.3.1. Minor Renovation

It is assumed that the renovation leads to no changes in energy consumption, as the renovation focuses on minor renovation work, where repair of building parts is included, as well as minor changes and replacements, e.g., fixing damaged parts of a facade, painting interior walls or replacing damaged windows, without impacting energy use.

The LCA approach for minor renovations focuses on investigating different design solutions to support design choices in the design phase:

- -

- Goal and scope: Compare designs based on a cradle-to-grave system boundary, based on the included life cycle stages

- -

- Reference study period: 50 years

- -

- Functional unit: kg CO2-eq./m2/year

- -

- Life cycle stages:

- ○

- Year 0: None

- ○

- Year 0–50: A1–A3, A4–A5, B4–B5, C3–C4

- -

- Material handling and operation: Only newly added materials are included in the assessment

- -

- Evaluation and assessment: Direct comparison of comparable choices

3.3.2. Moderate Renovation

Changes made as part of a moderate renovation are assumed to potentially impact the building’s energy consumption, e.g., by adding insulation or new windows, resulting in a new heat transfer coefficient (U-value).

The LCA approach for moderate renovations strives to investigate renovation-related CO2 emissions:

- -

- Goal and scope: Determine the CO2 impact for a renovation situation with a focus on promoting energy demand reduction based on the cradle-to-grave system boundary, with options

- -

- Reference study period: 50 years

- -

- Functional unit: kg CO2-eq./m2/year

- -

- Life cycle stages:

- ○

- Year 0: C3–C4

- ○

- Year 0–50: A1–A3, A4–A5, B4–B5, B6, C3–C4

- -

- Material handling and operation: The emissions from materials that are removed and added to the project are included in the assessment, but the existing materials of the building are excluded from the evaluation

- -

- Evaluation and assessment: comply with energy requirements and future limit values

3.3.3. Deep Renovation

The deep renovation differs from the moderate renovation as more major changes are made to the building. The changes can include transforming a building or altering its function. Deep renovation also includes cases where large parts of the building are changed, for example, a completely new facade and roof, or if only the static system of the building is retained. The changes to the building will require a new energy framework calculation, as the deep renovation impacts the building’s energy use. The LCA approach for moderate renovations strives to investigate renovation-related CO2 emissions:

- -

- Goal and scope: Determine the CO2 impact for a renovation situation with a focus on promoting energy demand reduction and significant changes to the building based on the cradle-to-grave system boundary, with options

- -

- Reference study period: 50 years

- -

- Functional unit: kg CO2-eq./m2/year

- -

- Life cycle stages:

- ○

- Year 0: C3–C4

- ○

- Year 0–50: A1–A3, A4–A5, B4–B5, B6, C3–C4

- -

- Material handling and operation: Existing and added materials are included.

- -

- Evaluation and assessment: Comply with energy requirements and future limit values

3.3.4. Restoration Renovation (Buildings Worthy of Preservation and Listing Protection)

Restoration and renovation involve the restoration of a building, with the aim of preserving its original features. If the building has been categorised as worthy of preservation or listed for protection, then restrictions apply to the renovation work that can be carried out, and a permit from the relevant authorities is required. For buildings categorised as worthy of preservation, only the exterior heritage and history must be retained; whereas for buildings listed as protected, both the exterior and interior must be preserved. Due to the limitations of these types of buildings, meeting Building Regulations (BR18) requirements is flexible, as there is the possibility of dispensation.

Changes made to a building undergoing restoration may impact its energy use, and the proposed LCA approach includes a new energy calculation and module B6.

The differences between the regulations related to buildings worthy of preservation and protected buildings lead to the proposal of two distinct LCA approaches.

The LCA approach applied to buildings worthy of preservation renovation is as follows:

- -

- Goal and scope: Compare designs based on the cradle-to-grave system boundary with options, where the aim is to support the decision-making process

- -

- Reference study period: 50 years

- -

- Functional unit: kg CO2-eq./m2/year

- -

- Life cycle stages:

- ○

- Year 0: C3–C4

- ○

- Year 0–50: A1–A3, A4–A5, B4–B5, B6, C3–C4

- -

- Material handling and operation: New and old materials are included

- -

- Evaluation and assessment: Meet the requirements for being worthy of preservation, and the LCA results can be used to find the best sustainable solution

The LCA approach for renovations for protected buildings is as follows:

- -

- Goal and scope: Compare designs based on the cradle-to-grave system boundary, where the aim is to support the decision-making process

- -

- Reference study period: 50 years

- -

- Functional unit: kg CO2-eq./m2/year

- -

- Life cycle stages:

- ○

- Year 0: None

- ○

- Year 0–50: A1–A3, A4–A5, B4–B5, B6, C3–C4

- -

- Material handling and operation: New materials will only be included

- -

- Evaluation and assessment: Meet the requirements for listing protection, and the results can be used to find the best sustainable solution

4. Case Study

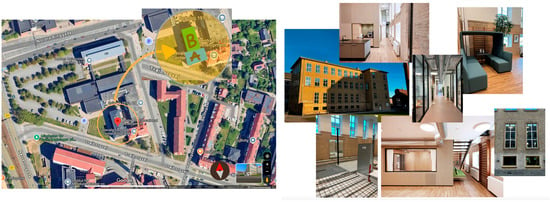

The case study carried out is based on a building from 1932 owned by Aarhus University. The building was constructed in 1932 and initially served as the Aarhus Women’s Seminary. The building was designed by architects Rudolf Frimodt Clausen and Ejnar Høvring Nielsen [62]. In 1954 and 1962, the building underwent an extension and renovation [63]. Today, the building houses The Centre for Educational Development (CED), which focuses on teaching and competence development, providing assistance and guidance to Aarhus University’s teachers and leaders. CED also works on university pedagogical research, development projects and experiments within learning technology, teaching, and education [64]. The building consists of 4 floors with an associated gymnasium. Figure 10 shows the building’s location. In the project, building 1911 has been divided into two parts: building A and building B. The orientation of buildings A and B is marked on Figure 10.

Figure 10.

Building 1911 with location and marking buildings A and B for the new Educational Centre at Aarhus University, Aarhus, Denmark [62].

4.1. Presentation of the Case

The building has undergone a renovation and transformation, evolving from academic premises and a gymnasium to housing office spaces, teaching rooms, and social areas. The building has been renovated to meet today’s technical and functional needs. Through the transformation, the building’s identity has been preserved and strengthened, despite the change in function. The building features a gymnasium with a temporary design, which has been preserved during the renovation [62].

Due to its building style, the building is classified as Class 3 under the category of buildings worthy of preservation [62]. Class 3 indicates that the building has a high ranking in terms of its worthiness of preservation, which may influence the degree of changes that can be made to the façade during the renovation process.

During the transformation, the rooms in the building have been fully renovated, and the gymnasium has been adapted for office use in terms of interior design. As part of the renovation, a new sunken deck has been constructed in the gymnasium, and new windows have been installed.

This renovation project has made it possible to rethink the renovation of buildings that have been declared worthy of preservation. A balance has been created between past and present by maintaining the functional history of the building, where the height of the gymnasium is optimally utilised through the construction of a new inserted floor deck with a glass vault, which creates an incidence of light to the ground floor. Functionality and design meet the needs of the users while respecting the building’s conservation values, performed through non-traditional solutions.

4.2. Case Baseline

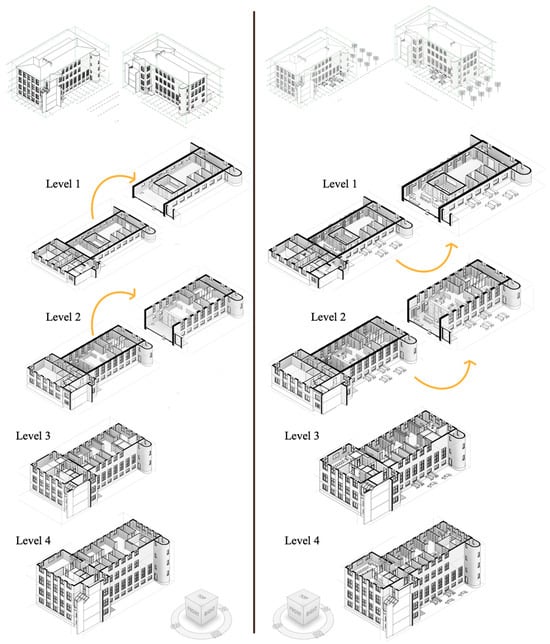

The Revit model used as the foundation for the LCA study is presented in Figure 11. The project’s associated BIM Level of Development (LOD) is LOD-300 according to the specifications defined in [65]. Before the model was imported into OneClickLCA, it was simplified by removing fixed and loose inventory that is not included in the LCA study, such as furniture, kitchens, and toilets.

Figure 11.

The building case’s original Revit model (right) and the clean-up version model (left).

4.2.1. Baseline Energy Use (B6)

The building’s energy consumption was calculated using Be18 to establish a theoretical baseline for energy use. In establishing the baseline, the following data were added to the calculation tool:

- -

- Building type: Educational buildings

- -

- Heated floor area: 1607.5 m2

- -

- Developed area: 1607.5 m2

- -

- Heat capacity: 106.6 Wh/k m2

- -

- Normal usage: 45 h/week (start at 8 am and end at 17 pm)

- -

- Heat supply is district heating combined with heat pumps, where Table 3 contains the heat capacity calculations.

Table 3. Heat capacity of the building elements.

Table 3. Heat capacity of the building elements.

As exact data on the U-values and Psi-values of the building envelope were unavailable, a worst-case approach was employed based on the building’s age, such as a two-layer window glazing system. Table 4 provides an overview of the U-values for the elements included in the Revit model and in the existing building drawings. Some of the calculated U-values do not comply with current requirements, BR18, as the building was constructed before any U-value or insulation requirements existed. As the building was built to the standards in 1932, the baseline for energy use is expected to exceed the current building regulations’ energy requirements.

Table 4.

Heat transfer coefficient (U-value) used for the Be18 (the calculation of U-values is presented in an Excel format, which can be found in the Supplementary Materials to the article).

Table 5 presents the Psi-values (Line Loss). The line loss for the foundation is based on the minimum requirement from BR18.

Table 5.

Line Loss for Be18.

Table 6 provides an overview of whether the building case, in its pre-transformation state, meets any of the requirements regarding energy use, specifically the energy classes from BR18 in Denmark [45]. The results of the energy calculation are presented in Table 7.

Table 6.

Compliance of the baseline with the existing energy frameworks in BR18 (clauses 260 and 280–282) [45].

Table 7.

Energy results from Be18 for baseline (kWh/m2/year).

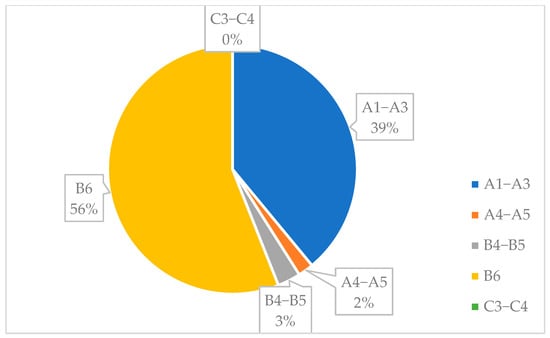

4.2.2. Baseline GWP

The LCA for the baseline is based on the modules A1–A3, A4–A5, B4–B5, B6, and C3–C4, spanning a 50-year reference study period. The total GWP of the baseline is 1.59∙1006 CO2-eq., corresponding to an emission of 19.74 kg CO2-eq./m2/year. The result is significantly higher than the current limit value of 7.5 kg CO2-eq./m2/year for office buildings in BR18 [41]. The distribution of the emissions among the assessed modules is presented in Figure 12. The figure shows that the majority of emissions originate in B6, followed by A1-A3. The demolition of the buildings in C3 and C4 contributes the least to total emissions, primarily because they are built of brick, mortar, and concrete, which have minimal environmental impacts compared to A1–A3.

Figure 12.

LCA modules’ CO2 emission level for the baseline case study.

5. Results

The following subsections present the results of applying the proposed LCA methodology for different renovation depths to the case building.

5.1. Minor Renovation

Following the LCA methodology for minor renovation, three scenarios are explored. The scenarios are presented in Table 8. In doing so, no new energy calculation has been made, as the LCA approach for minor renovations does not include B6. The renovation scenarios presented in Table 8 are also assumed not to significantly impact the building’s energy consumption, thereby aligning with the decision not to perform an energy calculation for these scenarios.

Table 8.

Renovation scenario: Minor.

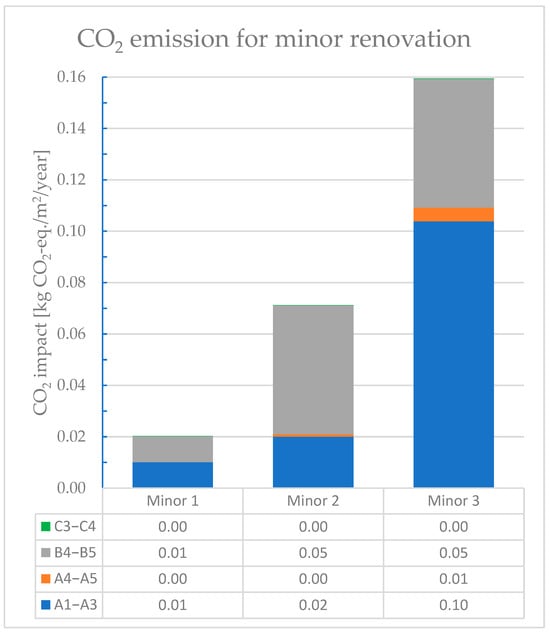

As shown in Figure 13, the results indicate that the environmental impact from all three scenarios is minor compared to the limit value for newly constructed office buildings, as the LCA calculation includes only new materials.

Figure 13.

LCA results for the minor renovation scenarios.

The environmental impact of the minor renovation scenarios primarily stems from the A1–A3 modules, consistent with the fact that the renovation scenarios focus on building parts with a long lifespan and use building materials with a high upfront carbon impact. The renovation work carried out has a minor environmental impact compared to existing benchmark values and the current environmental impact of the building. The investigation of the environmental impacts of minor renovations may yield only insignificant opportunities for optimisation, in the broader scope, with significant investments of time and money that may not be deemed worthwhile from the perspective of the developer or project consultant. Instead of carrying out an LCA, decisions can be based on a combination of common sense (for example, if windows need replacing, then they should be replaced with windows living up to today’s standard) and direct comparison of EPDs (e.g., comparing the EPDs of comparable bricks or windows when deciding which product to use). However, these approaches can only be applied in simple cases where materials can be directly compared and there are no cascading consequences of the renovation on the building.

5.2. Moderate Renovation

Following the LCA methodology for moderate renovation, five scenarios focused on improving the building’s energy performance are explored. The scenarios are presented in Table 9. Due to the focus on energy performance across all scenarios, a new energy framework calculation has been performed for each.

Table 9.

Renovation scenarios: Moderate.

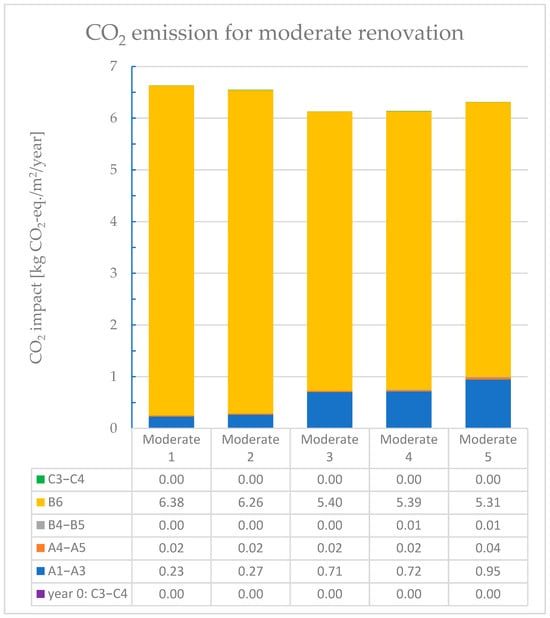

The renovation work is being carried out to improve the building’s energy efficiency. The building’s energy consumption is reduced by increasing the U-values in various parts of the building to meet the minimum requirements set out in the building regulations.

Scenario 1 improves the facade by insulating the building. In the original building, it is assumed that there is no insulation in the facade based on the external wall thickness. Likewise, the wall U-value does not comply with the minimum requirement; however, a reduction closer to the minimum has been achieved. For scenarios 2 to 5, the U-value has been further improved to meet the minimum requirements of the building regulations. LCA considers the disposal of materials from the existing construction, which occurs as part of the renovation, as well as the addition of new materials during the renovation. In scenario 2, it is assumed that the original insulation is retained in the roof but is not included in the energy and LCA calculations. In the detailed drawings of the building, insulation was already provided in the roof, but none in the facade. The insulation thickness was 0.045 m and was used to calculate the baseline. However, for moderate renovation scenarios, we ignored the original insulation due to uncertainty about its energy efficiency. Instead, we used a 0.15 m insulation thickness to estimate CO2 emissions from improving roof insulation. In addition, for scenarios 1 and 2, no materials are disposed of from the building during the renovation, resulting in zero emissions in modules C3–C4 in year 0. This applies to the other scenarios where materials are disposed of.

In Table 10, the results are compared to determine whether the renovation scenarios will meet the requirements outlined in BR18. It is observed that the actions taken in scenarios 1 and 2 meet the requirements for renovation class 2, while renovation class 1 is also upheld in scenarios 3–5. However, it is not possible to meet the requirements for new construction. The results of the energy calculation for the moderate renovation scenarios are presented in Table 11. The results show that improving the building’s insulation significantly reduces its heating energy consumption.

Table 10.

Compliance with the energy frameworks according to the BR18.

Table 11.

Energy results from Be18 for moderate renovation scenarios (kWh/m2/year).

Figure 14 shows the overall LCA results for the moderate renovation scenarios. A decrease in emissions is observed between scenarios 2 and 3, primarily due to the significant improvements in energy consumption, as shown in Table 11. The increase in emissions between scenarios 3, 4, and 5 is evident because more significant interventions lead to increased waste and material consumption, yet renovation is carried out based on energy improvements. The figure shows that the majority of the emissions originate in module B6, with a minor portion originating in modules A1–A3. From scenarios 1 to 5, the CO2 emissions for B6 decrease, while the emissions from A1–A3 increase in relation to the extent of renovation. Scenario 5 involves the most significant changes to the building and the largest improvements in energy performance. This results in scenario 5, among the five moderate scenarios, having the lowest emissions in B6 and the highest percentage-wise emissions from A1–A3. This illustrates a connection between the amount of added materials and the decrease in the building’s energy use. Based on the results presented in Figure 14, there is a trade-off between the degree of renovation and the GWP of the scenario. The proposed LCA method for moderate renovations can therefore be used to examine this trade-off and decide on the optimal degree of renovation from an environmental perspective. The introduction of limit values may be subject to discussion, as they depend on the scale of the renovation intervention.

Figure 14.

LCA results for the moderate renovation scenarios.

5.3. Deep Renovation

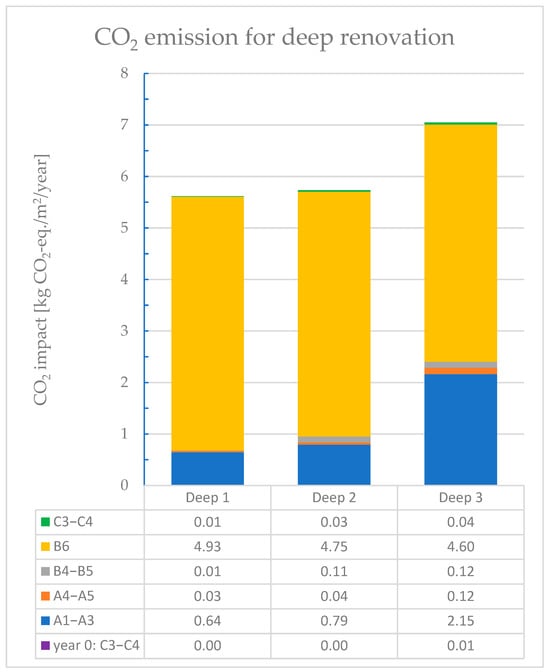

Following the LCA methodology for deep renovation, three scenarios focused on improving building energy performance and making major changes to building elements are explored. The scenarios are presented in Table 12, which includes significant changes to the building, resulting in the complete removal and addition of new individual building components. Structural stability is assumed to be maintained, even though a structural assessment was not conducted due to scope limitations.

Table 12.

Renovation scenarios: Deep.

Comparing the energy performance of the building in the deep renovation scenarios reveals that all scenarios meet the requirements for renovation classes 1 and 2, as shown in Table 13. Comparing the energy performance in Table 14 for the deep renovation with that in Table 11 for the moderate renovations reveals that the deep renovation will result in lower energy consumption. The course for this is evident in the fact that deep renovation involves changes to entire constructions, in contrast to moderate renovations, which only make changes to parts of the constructions, e.g., adding more insulation.

Table 13.

Compliance with the energy frameworks according to BR18.

Table 14.

Energy results from Be18 for deep renovation (kWh/m2/year).

Figure 15 presents the results of the LCA, conducted in accordance with the methodology for deep renovations. The assessment reveals an increase in overall emissions from scenarios 1 to 3, primarily driven by rising material consumption.

Figure 15.

LCA results for the deep renovation scenarios.

In the deep renovation scenarios, modules A1–A3 contribute a larger share of the total emissions compared to the moderate scenarios. This shows that although the initial CO2 emission for deep renovation is larger due to a larger addition of new materials, the time span of the calculation has the effect that the inclusion of a higher upfront carbon results in an overall lower emission due to the decrease in the energy use of the building, resulting in fewer emissions in B6. The trade-off between material consumption and energy savings is more favourable for deep than for moderate renovation, resulting in lower emissions. It is therefore essential to consider the construction structure in relation to energy consumption to maintain a balanced trade-off.

For deep renovation, major changes are made to the original building. The changes can, in more extreme manners, result in only the original static system being retained. In such a case, the building is close to being considered new, but it does need to comply with the climate requirements for new construction. This means that transformations and deep renovation can be used as loopholes to avoid the climate requirements. The methodology proposed in this work, as demonstrated in this case, allows for assessing the environmental impact of deep renovation or transformation and could serve as a basis for further developing limit values for deep renovations.

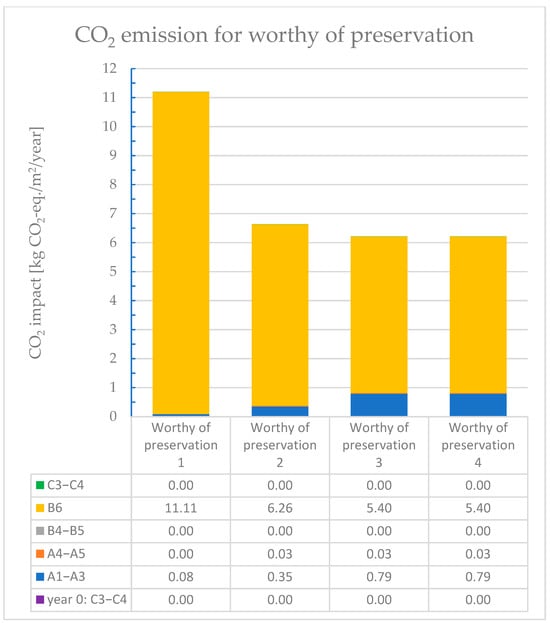

5.4. Restoration Renovation: Worthy of Preservation

Following the LCA methodology for buildings worthy of preservation, four scenarios have been explored. The scenarios are presented in Table 15. In scenario 1, no changes are made to the building’s energy use, whereas in scenarios 2 to 4, a new energy framework is calculated due to changes in insulation and windows.

Table 15.

Renovation scenarios: Worthy of preservation.

The renovation scenarios are comparable to the moderate scenarios. For scenario 4, the layout of the third and fourth floors has been modified to accommodate larger office spaces.

The energy use after completion of the renovation scenarios is presented in Table 16, where the drop in energy use for the building occurs in scenarios 2 to 4. The lack of change in the energy requirement for scenario 1 indicates that it does not comply with any of the energy classes in BR18, as shown in Table 17. Scenarios 2 to 4 all comply with renovation class 1, while scenarios 3 and 4 also comply with renovation class 2.

Table 16.

Energy results from Be18 for worthy of preservation (kWh/m2/year).

Table 17.

Compliance with the energy frameworks according to BR18.

The results of the LCA calculation, following the methodology for buildings worthy of preservation, are presented in Figure 16. In scenarios 1–3, CO2 emissions decrease. However, emissions increase in scenario 4 due to changes to the building interior and floor plan, which are not subject to restrictions in the conservation category. Thus, although the increase in this scenario is slight, it can be larger in other renovation projects. Changing the building interior for room layout generally does not lead to energy improvements compared to changing the building’s exterior. Thus, emissions from this type of renovation scenario can lead to increased impact, as no trade-off is made between energy use and the additional materials used for the building interior.

Figure 16.

LCA results for the worthy of preservation renovation scenarios.

Likewise, A1–A3 and C3–C4 (for years 50 and 0) are small, as only elements have been removed from the building, and no new ones have been added to alter the building layout. If new materials are added in connection with the change in the building’s floor plan, an increase in the modules can be expected.

5.5. Restoration Renovation: Listing Protection

Following the LCA methodology for buildings listed for protection, three scenarios have been explored. The scenarios are presented in Table 18. Due to the details of the scenarios, energy calculations are performed only for scenarios 2 and 3, as scenario 1 does not impact energy use.

Table 18.

Renovation scenarios: Listing protection.

The results of the energy calculation are presented in Table 19, with compliance with the energy classes outlined in Table 20. Scenario 1 does not comply with any of the energy classes. Scenario 2 complies with renovation class 2, and scenario 3 complies with both renovation classes 1 and 2.

Table 19.

Energy results from Be18 for listing protection (kWh/m2/year).

Table 20.

Compliance with the energy frameworks according to BR18.

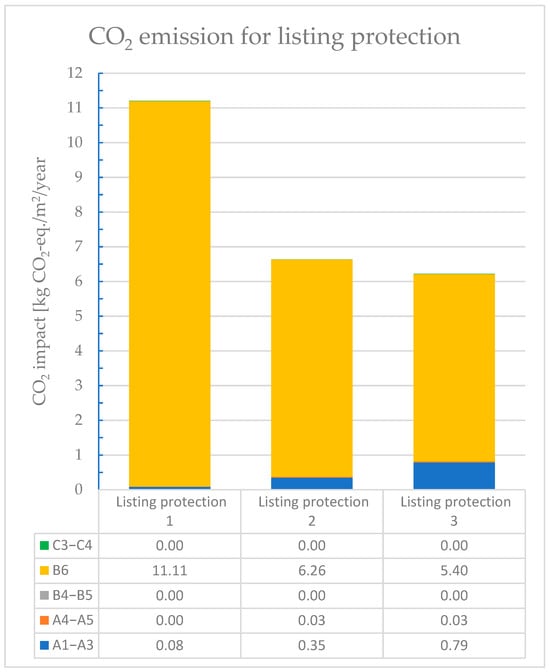

The results of the LCA calculation are presented in Figure 17. Due to restrictions on changes allowed for buildings listed for protection, there are limitations on the changes that can be made to reduce the building’s energy consumption. Changes to buildings in this category must therefore be carefully considered, as their operations can significantly affect the building’s overall impact. This impacts the LCA results because the B6 module accounts for a significant share of the building’s overall emissions.

Figure 17.

LCA results for the listing protection renovation scenarios.

The value of performing LCA of buildings listed for protection depends on the nature of the renovation being undertaken. If the renovation interventions are comparable to minor renovations, an LCA may provide limited value to the project, as energy use remains unchanged and building-related changes are straightforward, allowing comparisons and decisions to be made more effectively based on EPDs. In cases where the renovations are more extensive, e.g., scenarios 2 and 3, the LCA performance allows a variation analysis to be conducted. This enables the assessment of the trade-off between energy needs and emissions, allowing the selection of solutions with the lowest overall emissions. Introducing limit or benchmark values for the renovation of buildings listed for protection should not be considered, as stringent regulations regarding listed buildings limit viable renovation solutions. The acceptance of no-limit values for this building type can mirror the existing approach in BR18, where it is possible to obtain a dispensation for fulfilling energy requirements for listed buildings.

6. Discussion and Conclusions

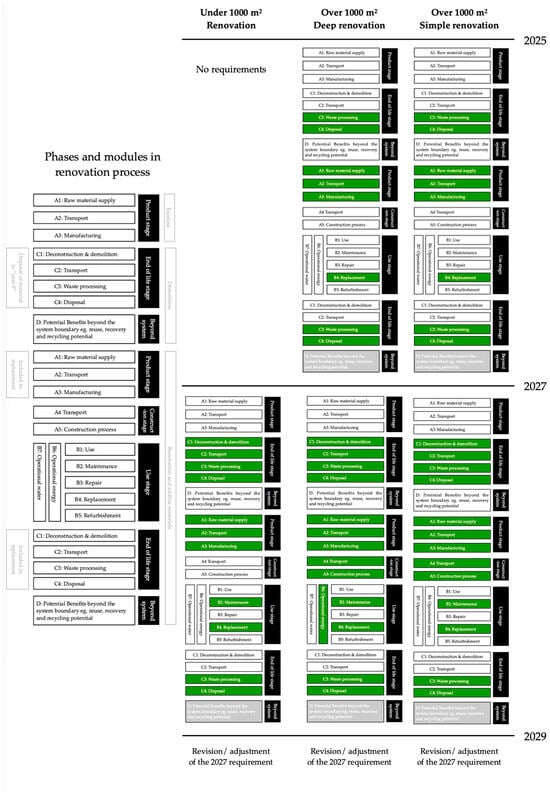

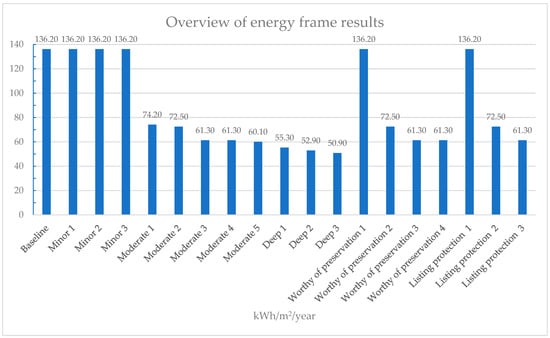

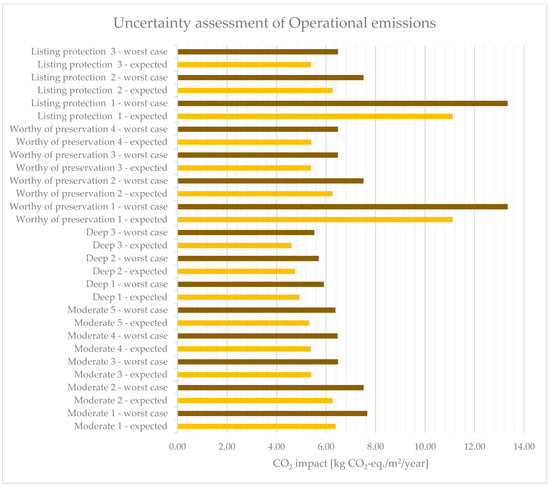

6.1. Energy and Overall CO2 Emissions of Renovation Depths

An overview of the energy demand from the assessed renovation scenarios on the building case study is presented in Figure 18. The figure illustrates a general trend of decreasing energy demand with more extensive renovation interventions, as compared to minor, moderate, and deep renovation cases. This finding echoes existing findings from Italy [69], indicating that the more extensive the renovations are in terms of energy optimisation, the greater the decrease in building energy demand. This trend is also observed in scenarios worthy of preservation and listing protection, as compared to renovation scenarios within each of these categories. This leads to the conclusion that renovating the building will result in energy savings if the renovation improves its energy efficiency measures. The degree of improvement depends on the building’s original energy needs.

Figure 18.

Overview of energy frame results for all renovation scenarios.

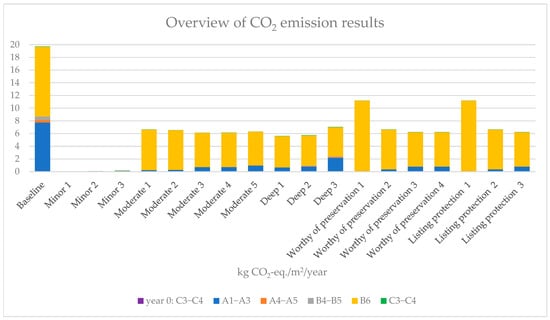

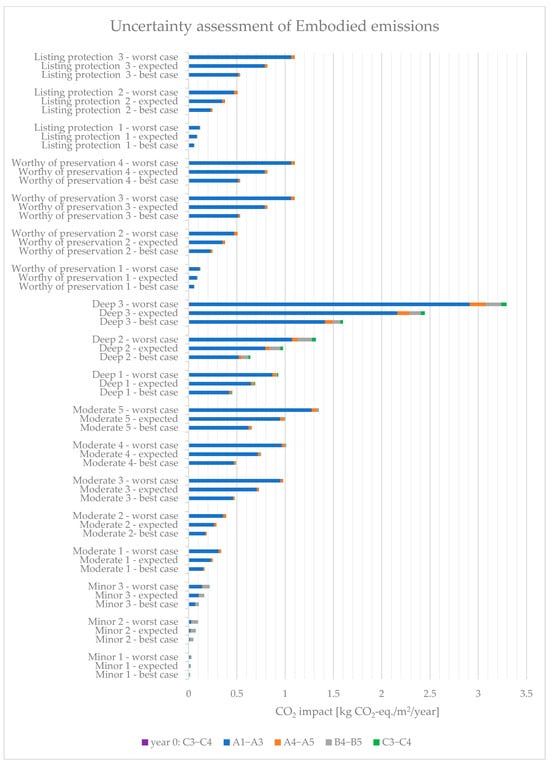

The results of the LCA calculations for the 18 scenarios and the baseline are presented in Figure 19. The results cannot be directly compared across renovation depths because the scope applied in the calculation for minor renovation differs from that applied to the remaining four renovation depths, as described in Section 3.

Figure 19.

Overview of the LCA results for all renovation scenarios. The building energy use is not included in the minor renovation scenarios.

In the three minor renovation cases, emissions increase with increasing renovation depth. This change is observed without affecting the expected energy use, resulting in the renovation adding embodied carbon to the project without any trade-off with operational carbon.

For moderate renovations, the GWP decreases slightly from scenario 1 to 3, as the embodied carbon from added materials reduces energy use, thereby lowering the building’s overall GWP. Likewise, between the moderate renovation scenarios 3 and 5, the building’s GWP increases even as its energy use decreases. This is caused by energy savings being offset by increased embodied carbon emissions in A1-A5 and C3-C4. In the moderate renovation scenarios, the point at which the payback time for the carbon investment (as defined in [63]) exceeds the building’s expected lifetime renders the renovation efforts introduced between scenarios 3 and 5 unsuitable from a purely environmental perspective. This finding aligns with the works of Huuhka et al. [70], showing that the reference study period is of significant importance when assessing the suitability of a renovation intervention for reducing CO2 emissions.

Comparing the energy use for the deep renovation (see Figure 18) with the CO2 emissions from the same scenarios further highlights the trend observed in the latter half of the moderate renovation scenarios, where an increase in embodied carbon is counterbalancing the reduction in operational carbon. This results in an overarching increase in GWP despite an apparent decrease in energy use. This indicates that the deep renovation scenarios all assess renovation activities for which the payback time for the carbon investment exceeds the reference study period.

In renovation scenarios for both worthy of preservation and listing protection, there is a decrease in emissions between scenarios 1 to 3, due to the significant reduction in building energy use. Between scenarios 3 and 4 in the worthy of preservation renovations, the GWP is increasing due to the lack of improvement in the building’s energy performance. Even though it is outside the focus of this study, other studies have previously found that renovating, restoring, or transforming buildings can still be worth it from an environmental perspective if the alternative is to tear down the existing building and build a new one [48,70]. The assessed scenarios for both worthy of preservation and listing protected buildings are limited by existing regulations that restrict the changes allowed during renovation or transformation.

Comparing the baseline emissions to those associated with the renovation scenarios reveals a significant difference in kg CO2 emissions/m2/year. These results, however, are not directly comparable due to the differences in the scope of the LCAs. The scope of the baseline LCA is based on the scope often applied to new construction buildings, following the methodology in BR18 [41]. In this light, LCA is conducted as if the building were constructed today, including embodied carbon and maintenance for all existing building parts, and energy use is calculated using Be18 [56]. On the contrary, the scope of the LCA for the renovation cases includes only the embodied carbon from the building parts that are replaced or added during the renovation, as well as the continuous maintenance of these parts, and the energy use for moderate, deep, worthy of preservation, and listed protected scenarios.

This methodological choice has two key implications. On the one hand, this means no direct comparison can be made between the baseline and the renovation cases due to differences in scope. On the other hand, the risk of double-counting materials or processes [71] are limited by excluding existing materials and structures from the renovation LCA, as this establishes clear boundaries for which life cycle of the building a given process belongs. The choice to exclude the maintenance and demolition of existing materials is also aligned with the LCA method used in the Danish version of the sustainability certification systems, i.e., DGNB [72].

The comparability of the results from renovation cases with emissions from newly constructed buildings is debated in the literature and in existing methodologies. In the work by Arkitema, COWI, BUILD Aalborg Universitet and Rådet for Bæredygtigt Byggeri [48], it is suggested that the emissions for renovated buildings should include maintenance of existing building parts as well, while the alternative of constructing a new building should consist of the emissions associated with tearing down the existing building. At the other end of the spectrum, the Danish version of the DGNB [64] system suggests that LCA for renovation cases should assess only the emissions associated with newly added materials, thereby aligning with the methodology applied in this study. Both the Danish DGNB system [72] and BR18 [41] do not require an LCA assessment for new buildings to include the demolition of the existing building, thereby establishing a clear distinction between the different life cycles of the buildings and limiting the theoretical risk of double-counting.

In all scenarios assessed, due to the lack of available data regarding the construction and operation of the case building, both the LCA and the energy calculation include uncertainties. Consequently, the presented results cannot be expected to directly correspond to changes in energy demand or to the building’s actual GWP.

Former studies show that the variation in GWP between comparable generic EPDs can significantly impact the result of LCAs for buildings [73,74], with one study even finding variations of up to 1500% in GWP between comparable isolation materials [73]. To limit the uncertainty resulting from data quality, this study utilised generic EPD data and kept the selected dataset constant across scenarios. This methodological choice means that changes in GWP between scenarios are due to the actual change described in the scenarios, rather than to changes in the assigned EPD. The choice of using generic EPDs aligns with the LCA method presented in BR18 [41] as well as the method applied in practice in the early design stages, when exact material choices have not been made yet [73].

The calculated energy use is not expected to reflect the building’s actual energy use, due to the performance gap [75], which is also present in the Danish Be18 tool [56]. Previous studies have been conducted on Be18’s predecessor, Be10, showing a significant gap between the calculated and the realised electricity and heat demand [76,77]. The LCA study presented in this paper maintains a consistent calculation method across renovation scenarios, and the errors in energy-use calculations are assumed to be constant. Further adding to the validity of using Be18 as the tool for calculating the energy demand of the building is the Danish building regulations’ requirement to use the tool for both the energy calculation [45], and as the basis for the energy demand in the LCA calculation [41].

In both moderate and deep renovation scenarios, the GWP of the renovation cases is comparable in range to the emissions identified for 23 renovation cases by Zimmerman et al. [78]. This supports that the presented results are of a magnitude comparable to and realistic for renovation cases in Denmark.

A further limitation in the study is the lack of structural assessment of the building in both the pre- and post-renovation scenarios. The study assumes that the renovation scenarios do not involve any significant structural modifications. It is therefore presumed that there is no need to strengthen or adapt the building’s static system. Even though this simplifies the modelling process, it may lead to overlooking environmental aspects of potential structural interventions in more complex, deeper renovation scenarios.

6.2. Limit Values