A Stochastic Multi-Objective Optimization Framework for Integrating Renewable Resources and Gravity Energy Storage in Distribution Networks, Incorporating an Enhanced Weighted Average Algorithm and Demand Response

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Motivation

1.2. Related Works and Gaps

- Most of the works focus only on BESS. The potential for GES as a storage solution with long duration and high cycle life for distribution networks remains unexploited, and most of the discussed applications are novel in a demand response framework [8].

- Though some studies [16,17,21] acknowledge uncertainty, most depend on deterministic models or computationally intensive methods, such as Monte Carlo Simulation. There is a lack of efficient modern probabilistic approaches, such as the two-point estimation method (2m + 1 PEM), applied to this problem.

- Most algorithms are applied to a narrow set of objectives. In this respect, it is necessary to develop an approach that simultaneously minimizes energy loss, pollution, and investment/operational costs within a unified stochastic framework.

- The potential synergy between demand response and gravity-based energy storage for enhancing voltage stability, reducing peak demand, and generally offering more flexibility to the grid has not been duly explored.

1.3. Contributions of the Paper

- This paper is among the first to formally model and integrate gravity energy storage within a demand response strategy. Unlike traditional incentive-based DR or battery-focused approaches, the proposed GES-based DR provides a physical, storage-backed mechanism for dynamic load management. This allows for a more robust peak shaving, increasing grid flexibility and contributing to voltage stability by active time-shifting of energy, hence offering a tangible alternative against pure financial load reduction.

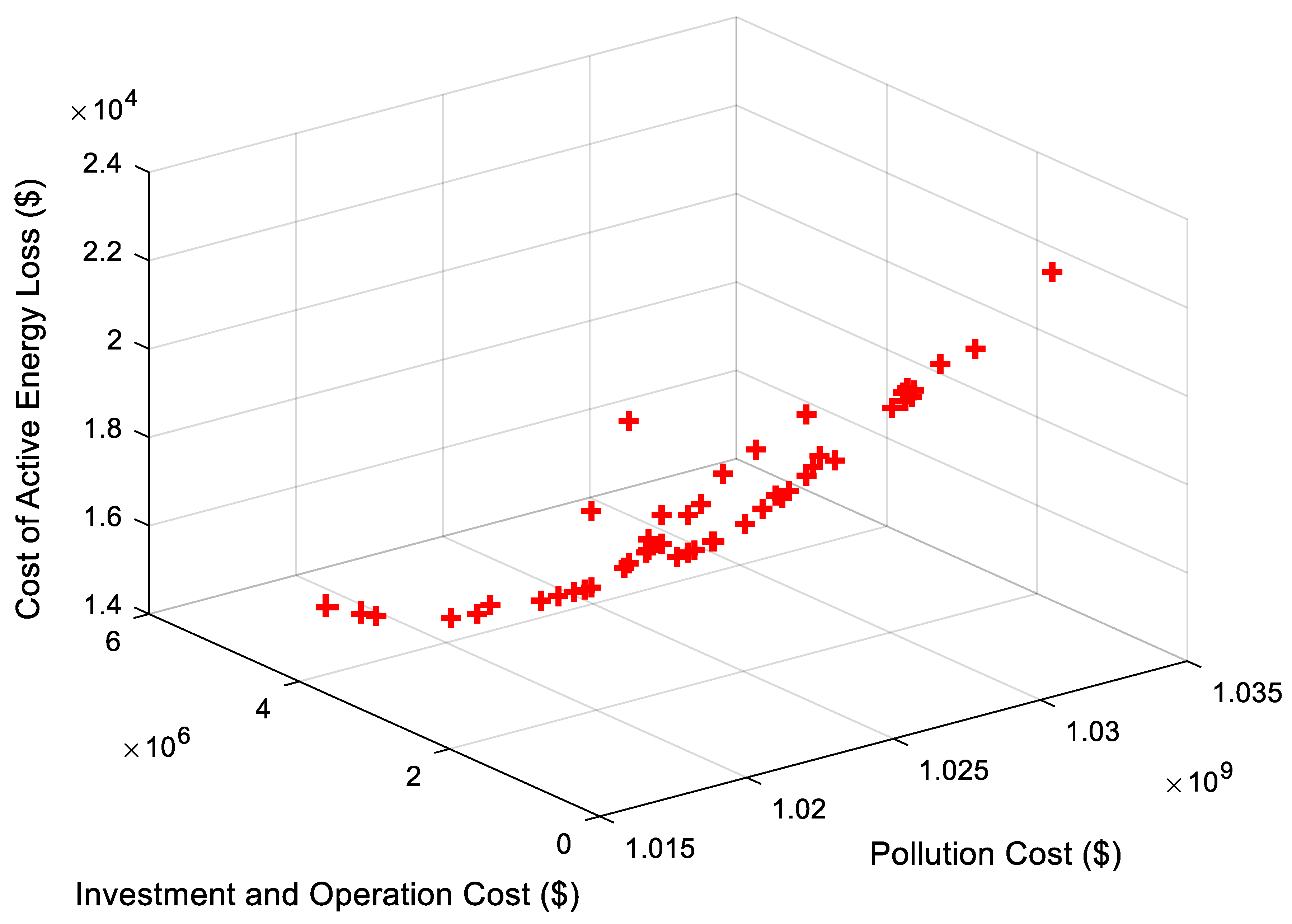

- This paper proposes a new metaheuristic called MO-EWAA, standing for multi-objective enhanced weighted average algorithm with an elite selection mechanism. While elite mechanisms are well recognized in optimization, their incorporation into the WAA is novel. More importantly, the ESM is deliberately designed to overcome the difficulties of a highly nonconvex, multimodal search space inherent in the simultaneous allocation of PV, WT, and GES units. The systematic preservation of the most promising nondominated solutions across iterations by the MO-EWAA effectively avoids premature convergence and local optima entrapment, which are common drawbacks of the classical WAA. This ensures the derivation of a well-distributed, high-quality Pareto front that offers network planners an improved set of trade-off solutions.

- This work implements an efficient probabilistic model based on the 2m + 1 PEM to capture uncertainties associated with renewable generation and load demand effectively. This represents a computationally tractable but powerful alternative compared to other, more intensive methods such as Monte Carlo Simulation. It allows a detailed assessment of how input uncertainties propagate to affect those key system outputs, such as energy losses and costs, that are of vital interest, thus leading to resilient and reliable planning decisions under real-world variability.

- This paper formulates and then solves a holistic multi-objective optimization problem of minimizing three conflicting objectives—the total cost of energy losses, the total cost of pollutant emissions, and the total investment and operational costs of integrated PV, WT, and GES systems—simultaneously. The model encompasses the full set of operational constraints: power balance, bus voltage limits, and line thermal ratings. Application of the fuzzy-based mechanism facilitates a balanced optimization among these competing goals and, as a result, presents a practical and comprehensive decision-support tool towards techno-economic-environmental optimality of modern distribution networks.

1.4. Organization of the Paper

2. Methodology

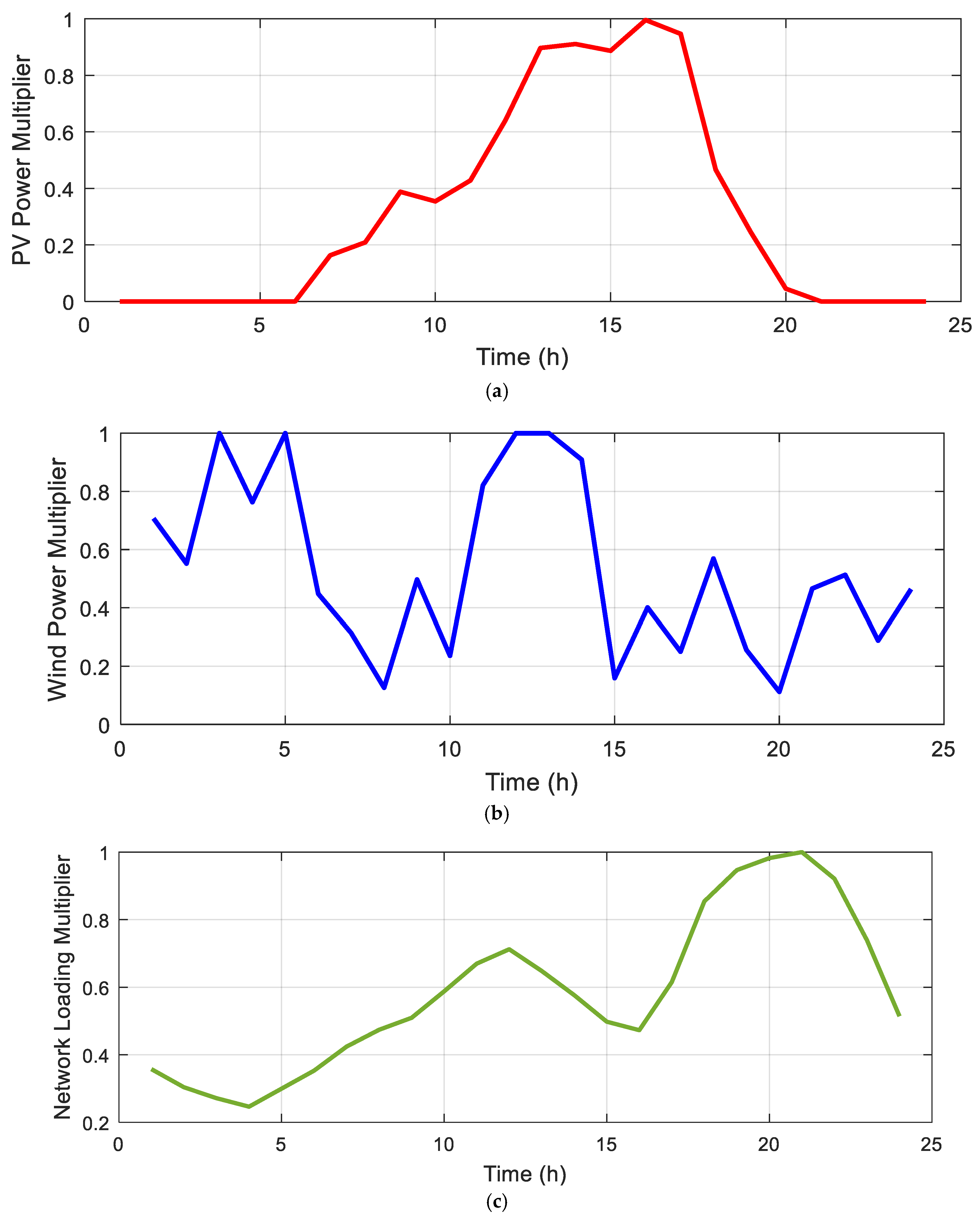

2.1. Renewable Resources and GES Storage Modeling

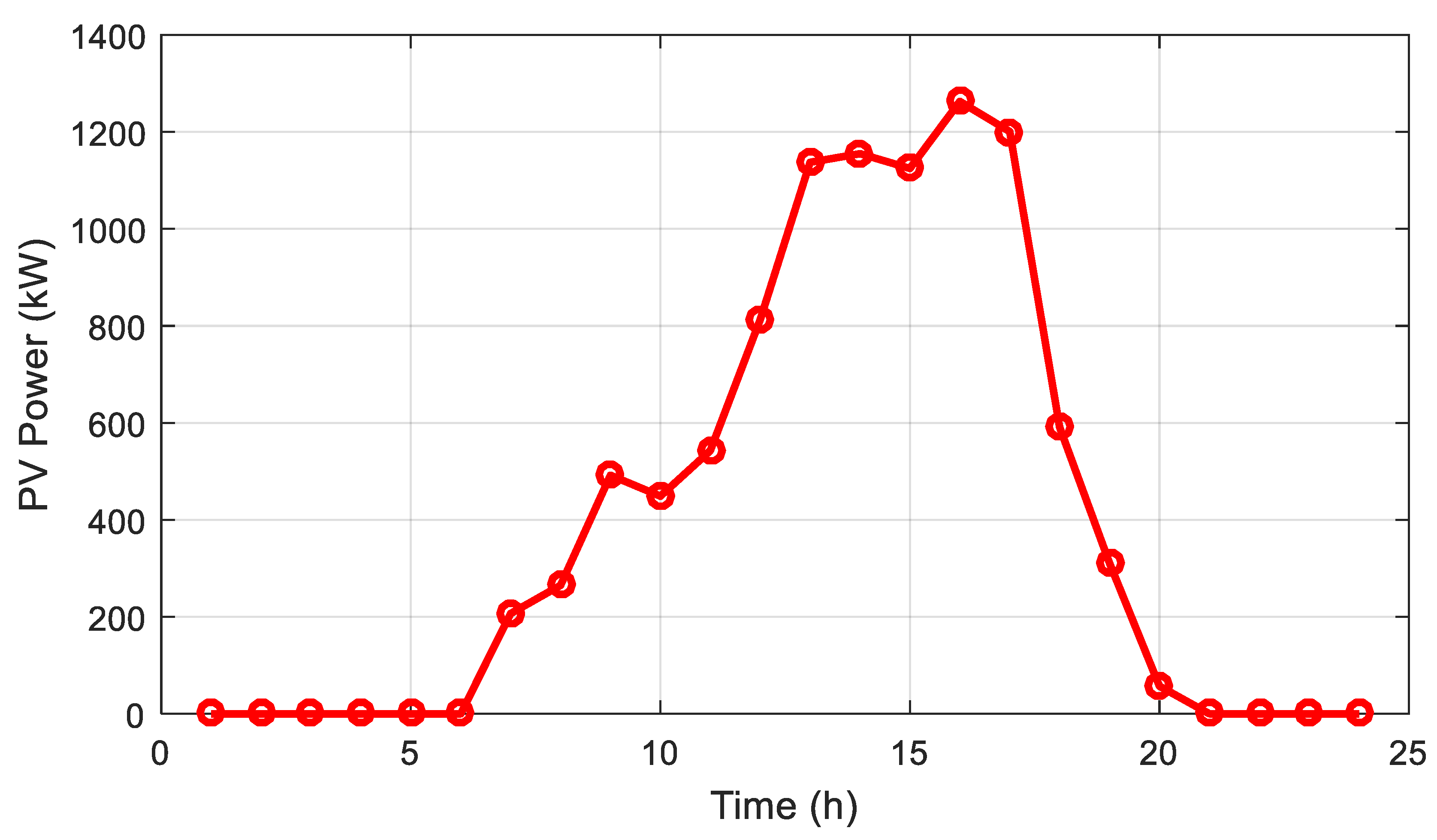

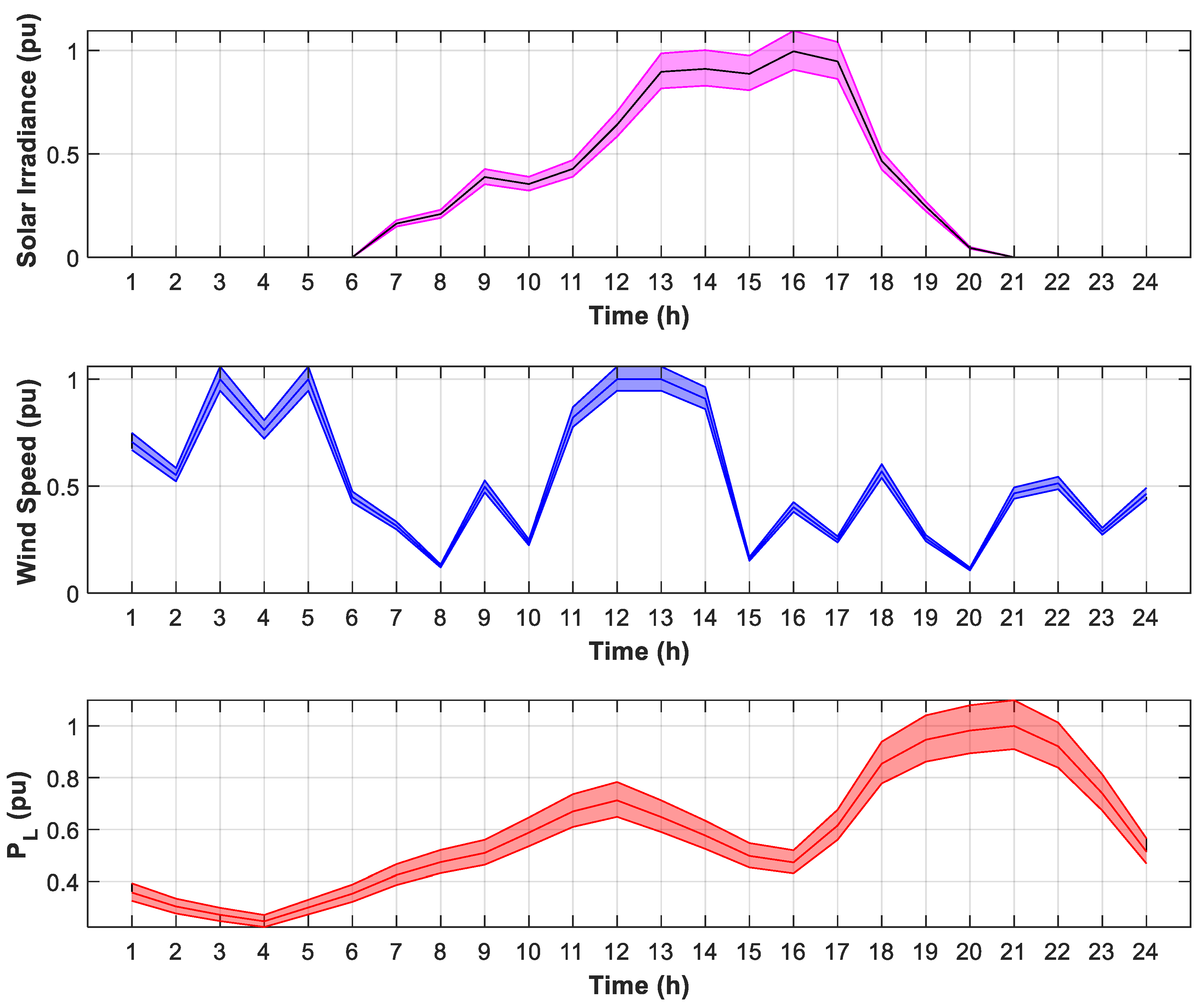

2.1.1. Photovoltaic Model

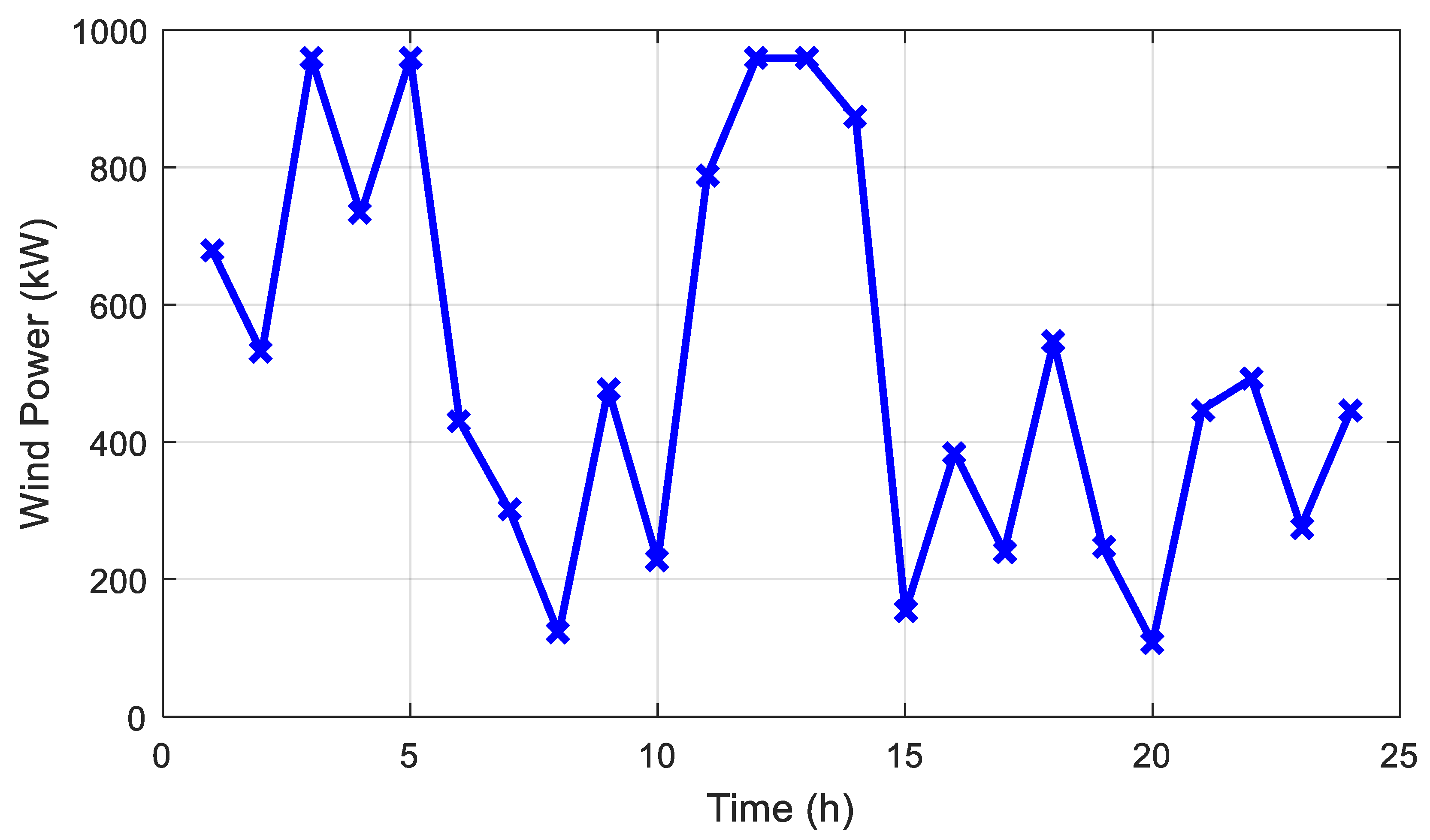

2.1.2. Wind Turbine Model

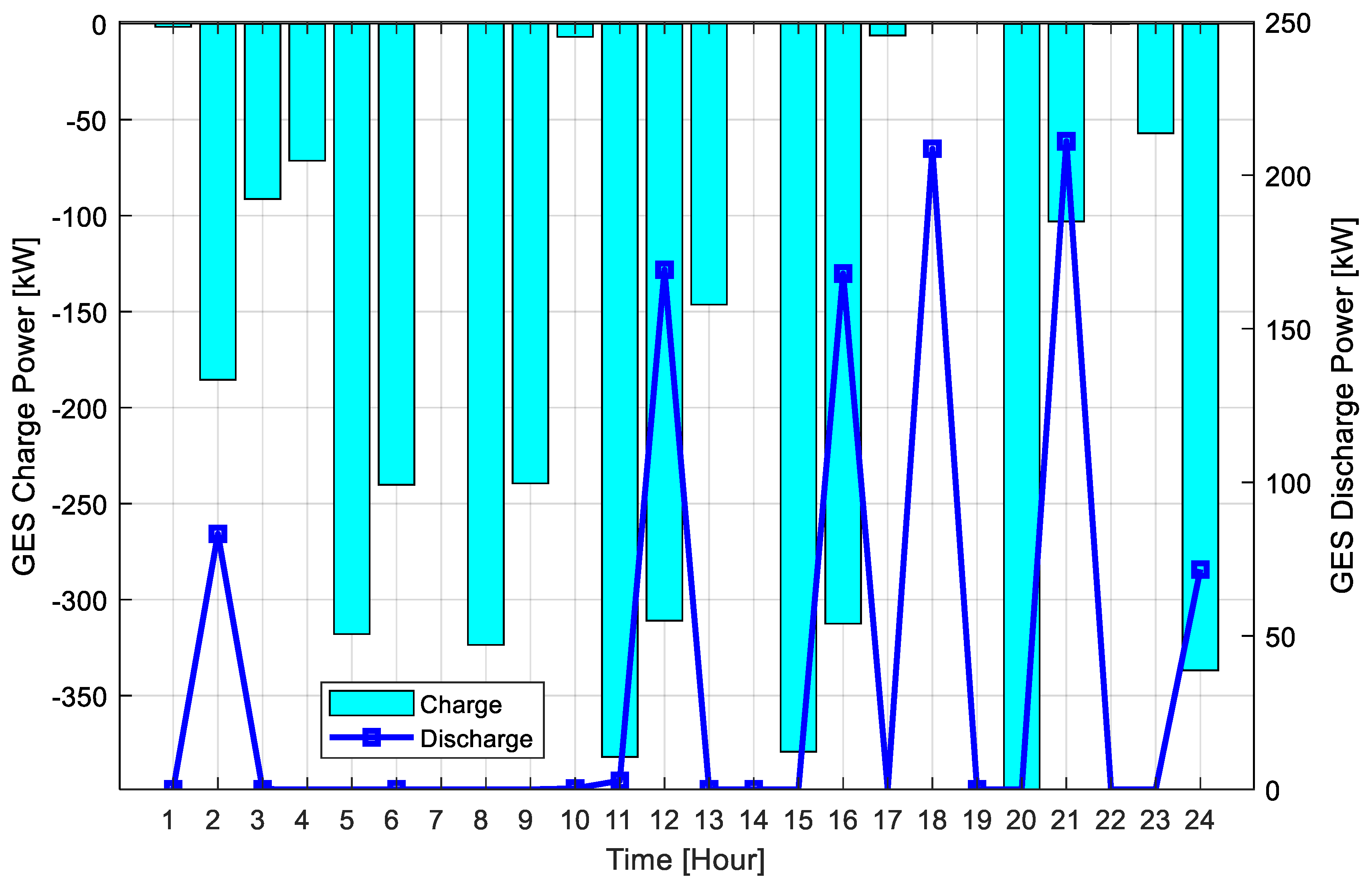

2.1.3. Gravity Energy Storage (GES) Model

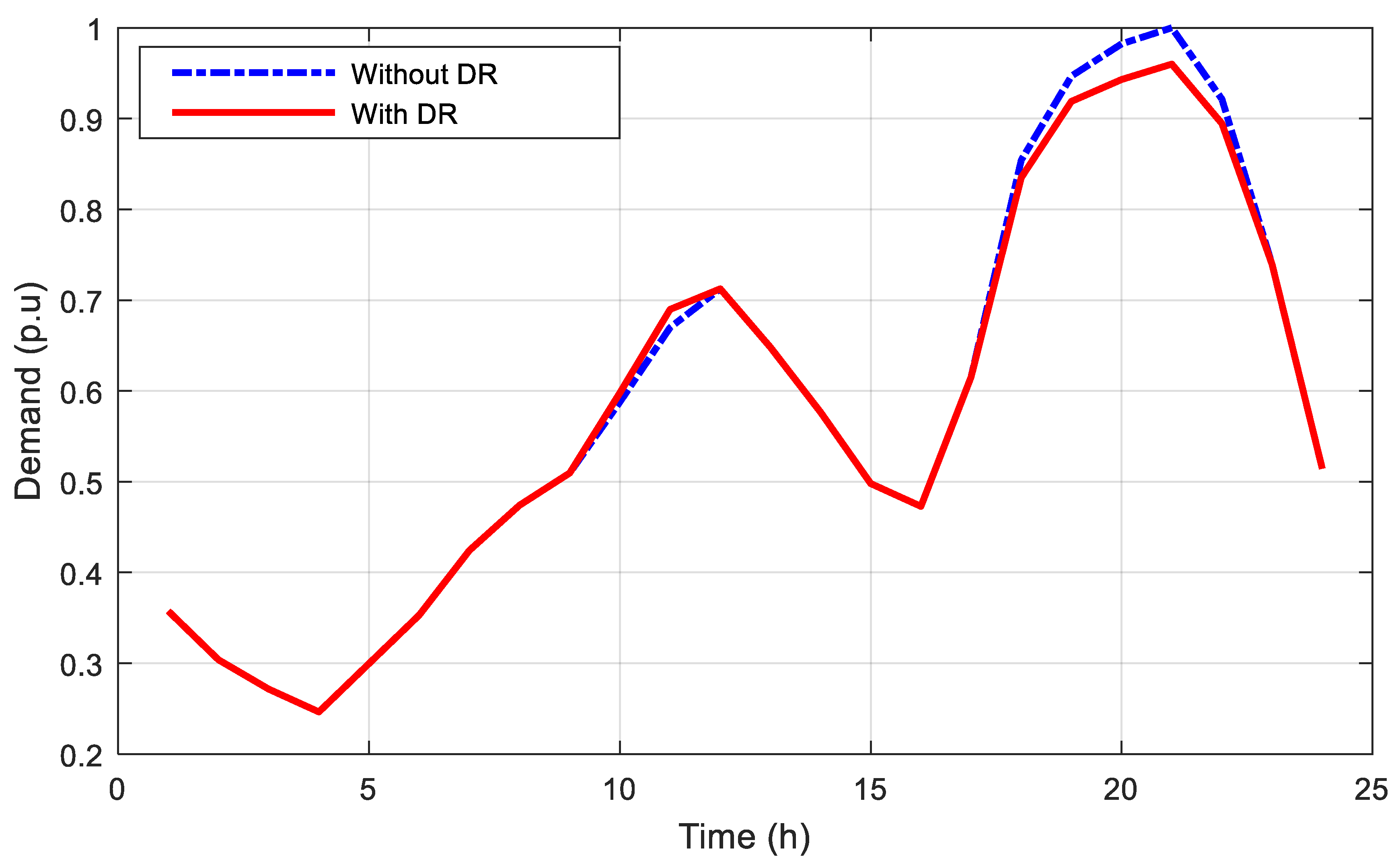

2.2. Demand Response Model

2.3. Objective Function

2.4. Constraints

2.4.1. Power Balance

2.4.2. Bus Voltage

2.4.3. Capacity of Line

2.4.4. Renewable and GES Capacity

- PV size

- Wind turbine size

- GES size

2.4.5. Reactive Power Capability of Inverter-Based Resources

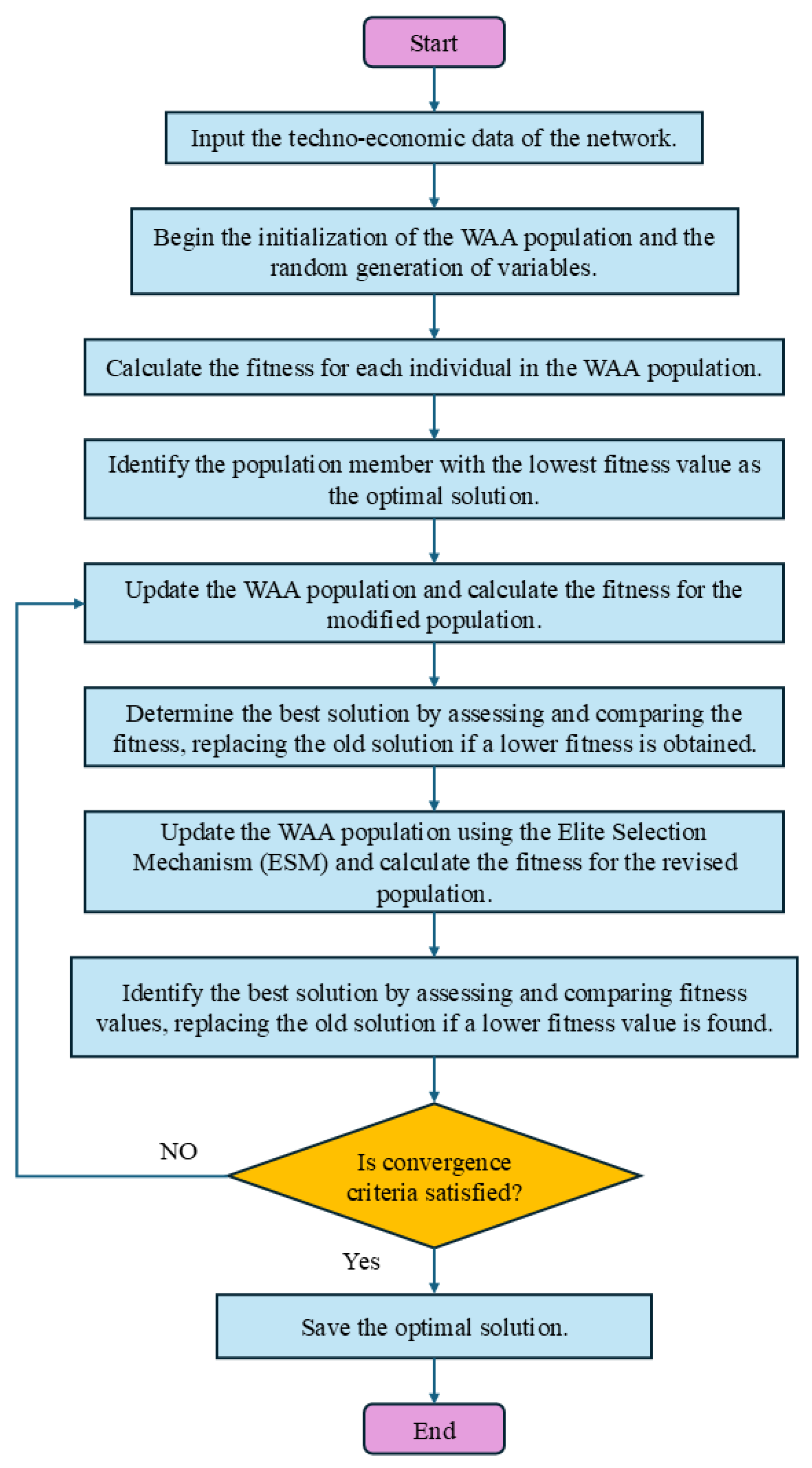

2.5. Proposed Optimizer (MO-EWAA)

2.5.1. Foundation: The Weighted Average Algorithm (WAA)

- (a)

- Initialization

- (b)

- Weighted Average Position Calculation

- (c)

- Search Phase Identification

- (d)

- Position Update Strategies

- Exploitation Phase: Refines solutions around promising areas by using three strategies:

- Guidance from the global best (), personal best (), and the weighted average () (Equation (26)).

- Movement between the personal best and the weighted average (Equation (27)).

- Movement between the global best and the weighted average (Equation (28)).

- Exploration Phase: Broadens the search to avoid local optima using two strategies:

- Lévy Flight: A random walk with intermittent long jumps (Equations (29)–(32)).

- Random Reinitialization: The act of guiding search agents to new, random positions within the search space (Equation (33)).

2.5.2. Enhancement: The Elite Selection Mechanism (ESM)

- Elite Selection: After sorting the population, the top solutions (e.g., 10% of the population) are marked as the elite set .The individuals of this elite are preserved unchanged for the next generation.

- Update of Non-Elite Solutions: The rest of the non-elite solutions are updated according to the position update rules of the conventional WAA (presented in Section 2.5.1, d), which utilizes weighted average, global best, and personal best positions.

- Merging of the populations: The revised non-elite population produced is combined with the elite set preserved to provide the new population for the next iteration.

2.6. Stochastic Approach for Uncertainty Modeling

- Identify Input Random Variables: Define the number of input random variables, for .

- Initialize Output Moments: Set the moments of the output variable (e.g., power loss or cost) to zero: for .

- For each random variable :a. Determine Concentrated Locations: Calculate two standard locations using the skewness () and kurtosis () of :b. Calculate Estimation Points: Determine the two estimation points :where and are the mean and standard deviation of .c. Form Input Vectors: Create two input vectors for the system model where all other variables are at their mean values:d. Compute Weights: Calculate the weighting factors for the two points:e. Update Output Moments: Run the system model for each vector and update the moments of :

- Central Point Evaluation (Optional for Hong’s 2PEM): Evaluate the system at the mean values of all inputs, . Calculate its weight and update the output moments accordingly.

- Final Statistics: After processing all variables, the mean and standard deviation of the output are obtained as:

3. Numerical Results and Discussion

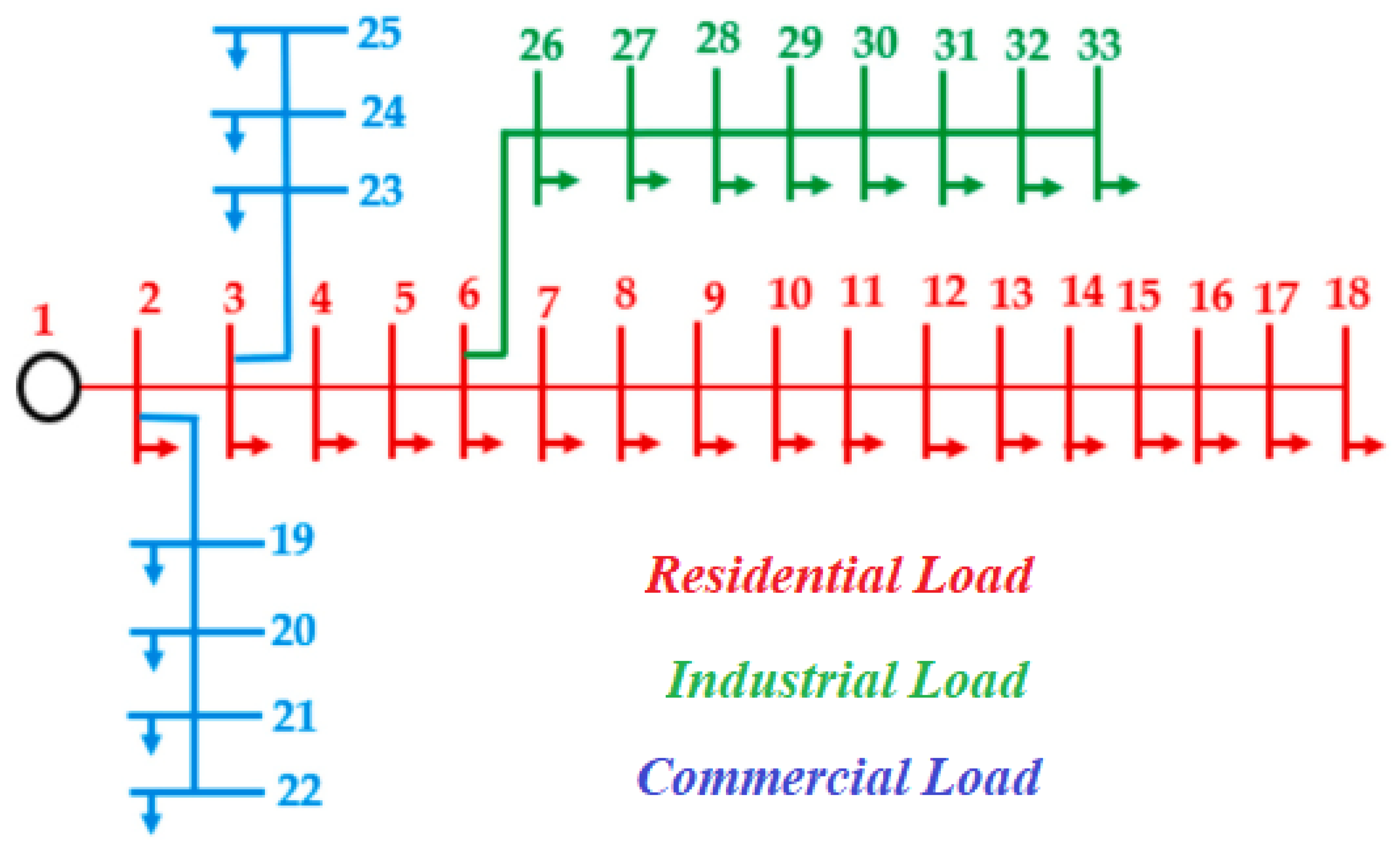

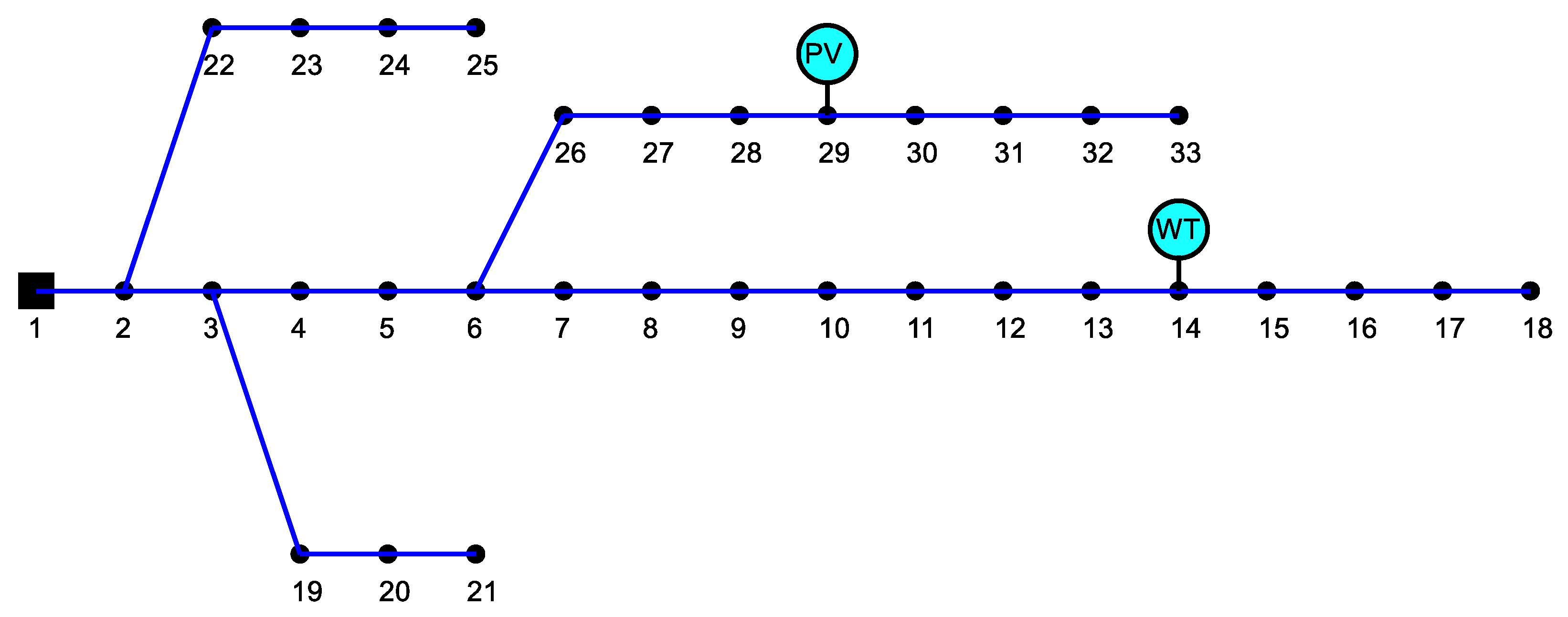

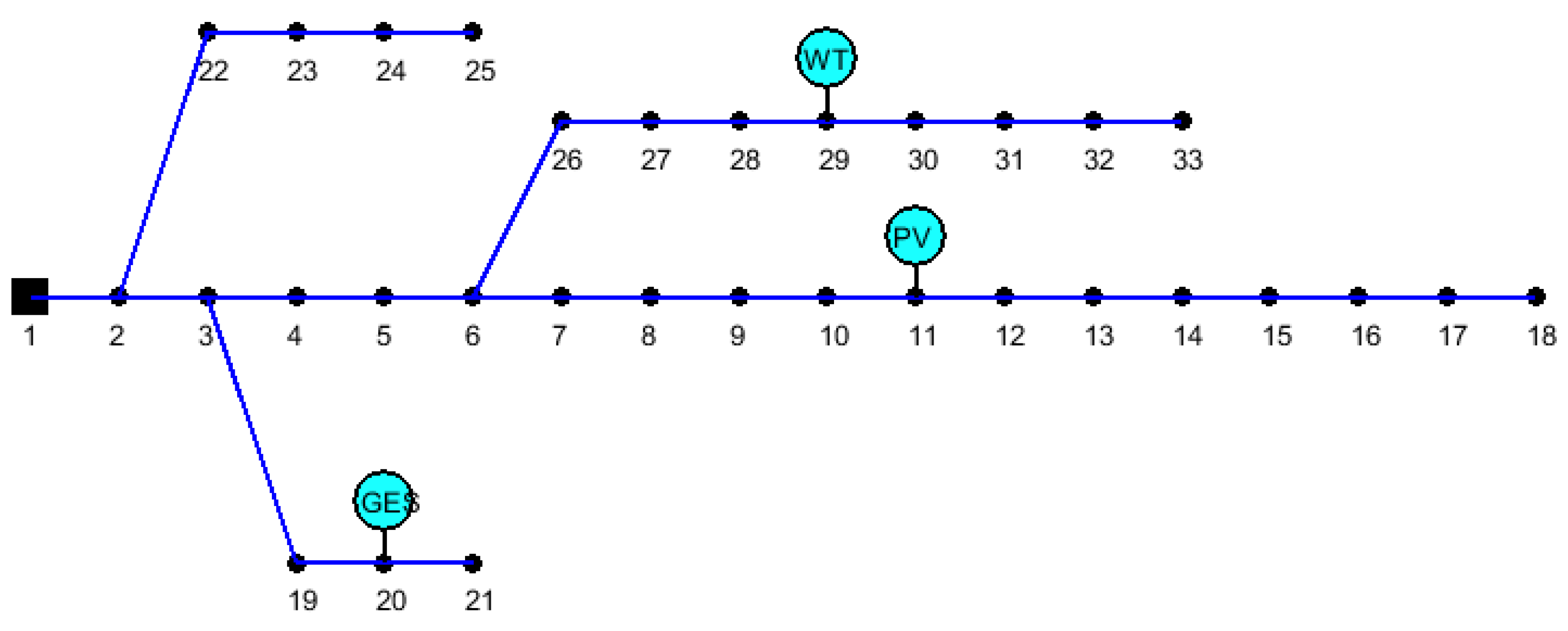

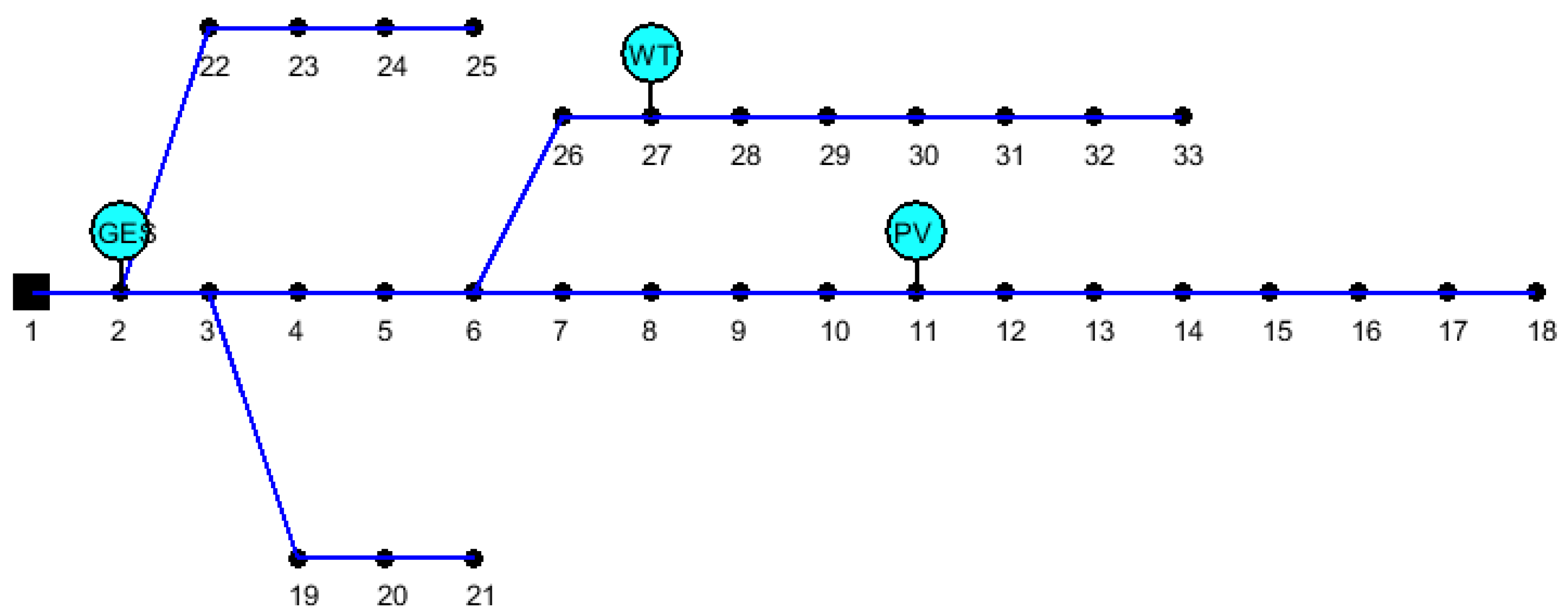

3.1. System Data Ans Simulation Scenarios

- Scenario 1: Optimization of renewable energy sources (RES) without the GES system.

- Scenario 2: Optimization of RES with demand response and without GES using MO-EWAA.

- Scenario 3: Optimization of RES and GES using MO-EWAA.

- Scenario 4: Optimization of RES and GES considering a probabilistic model using MO-EWAA.

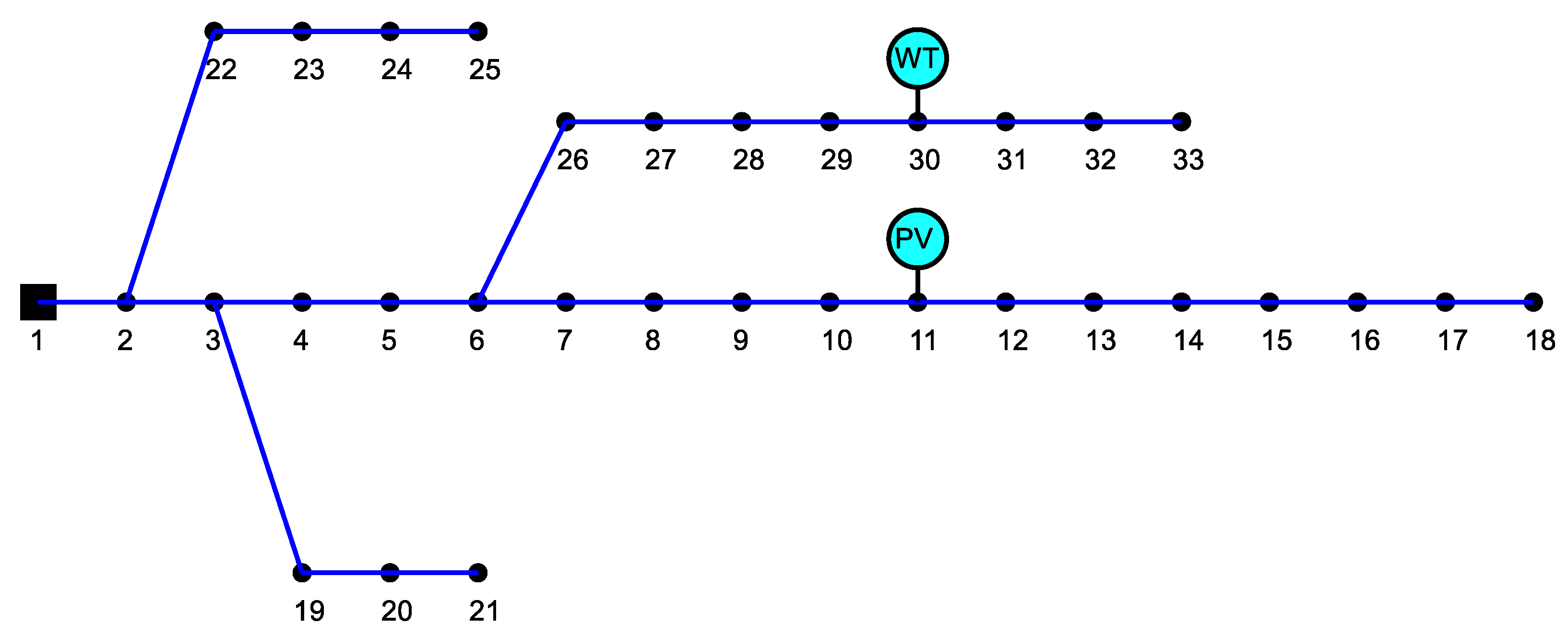

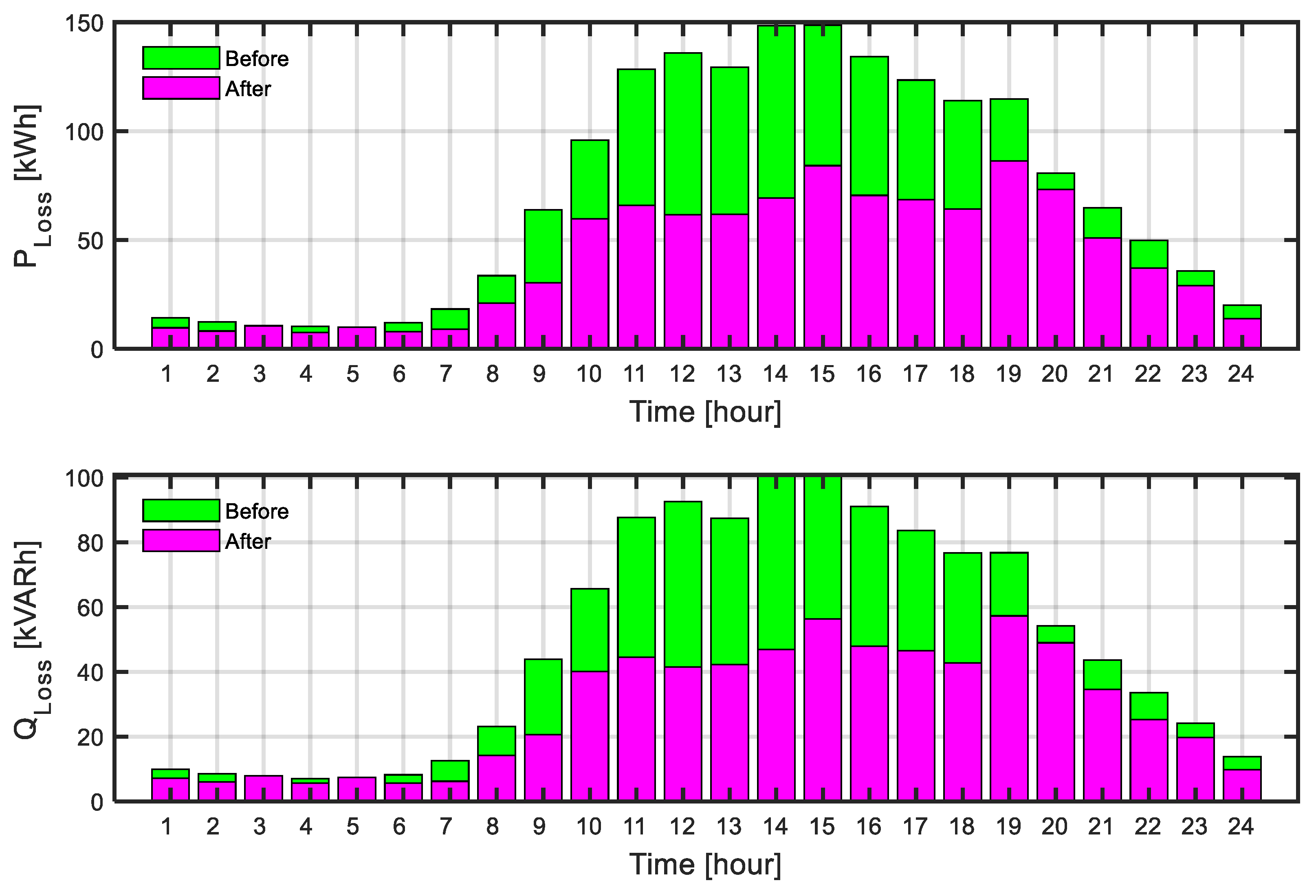

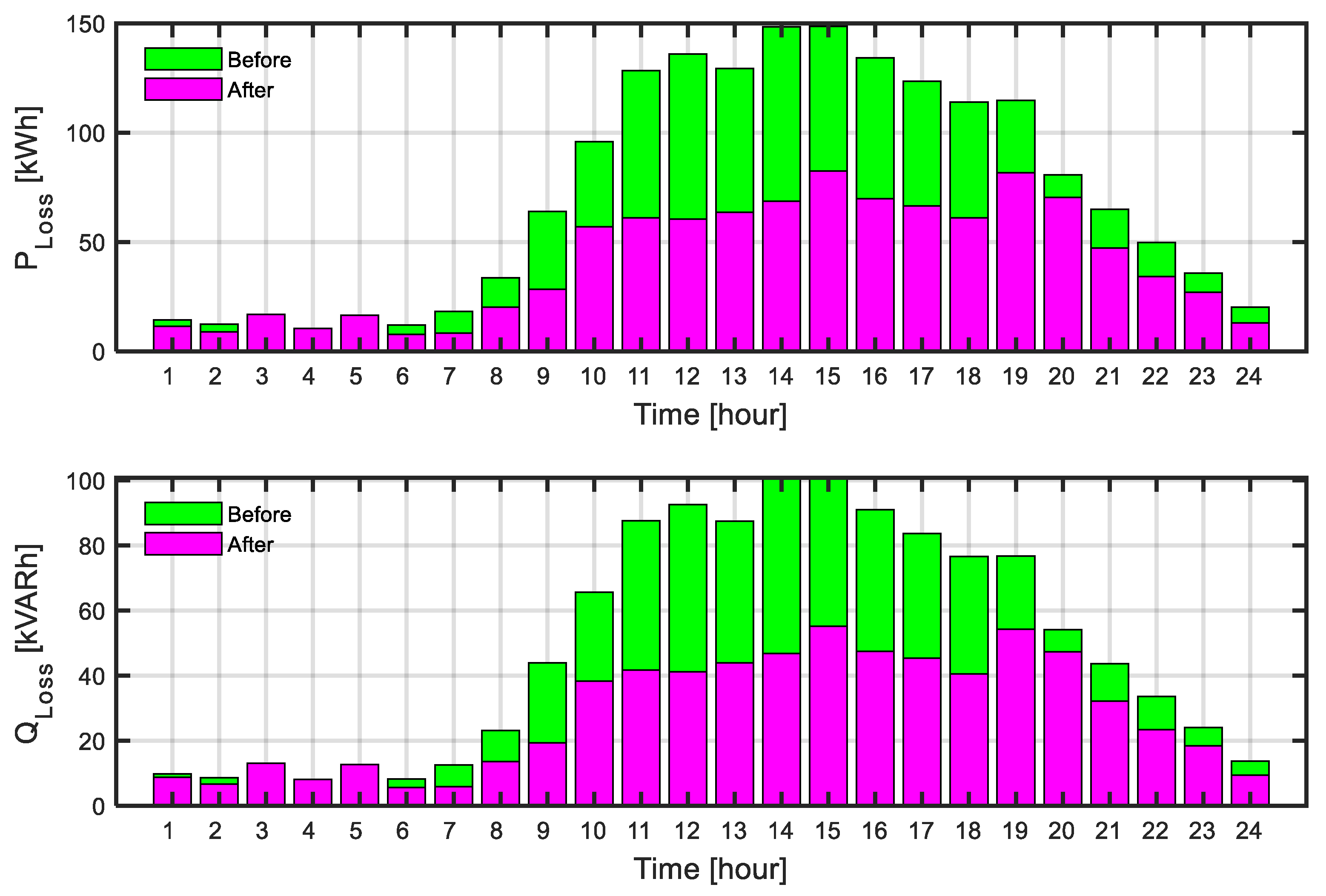

3.2. Results of Scenario One

3.3. Results of Scenario Two

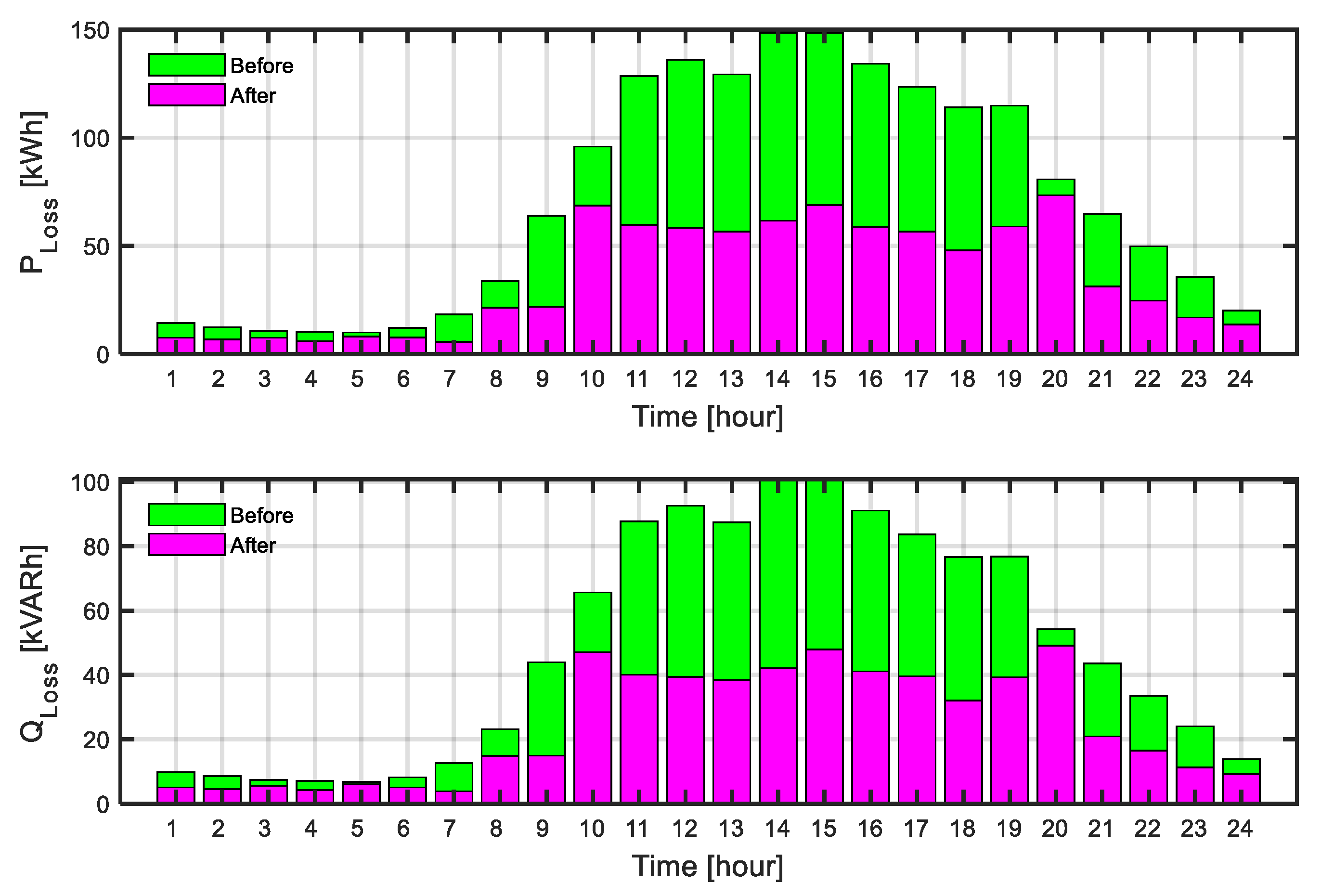

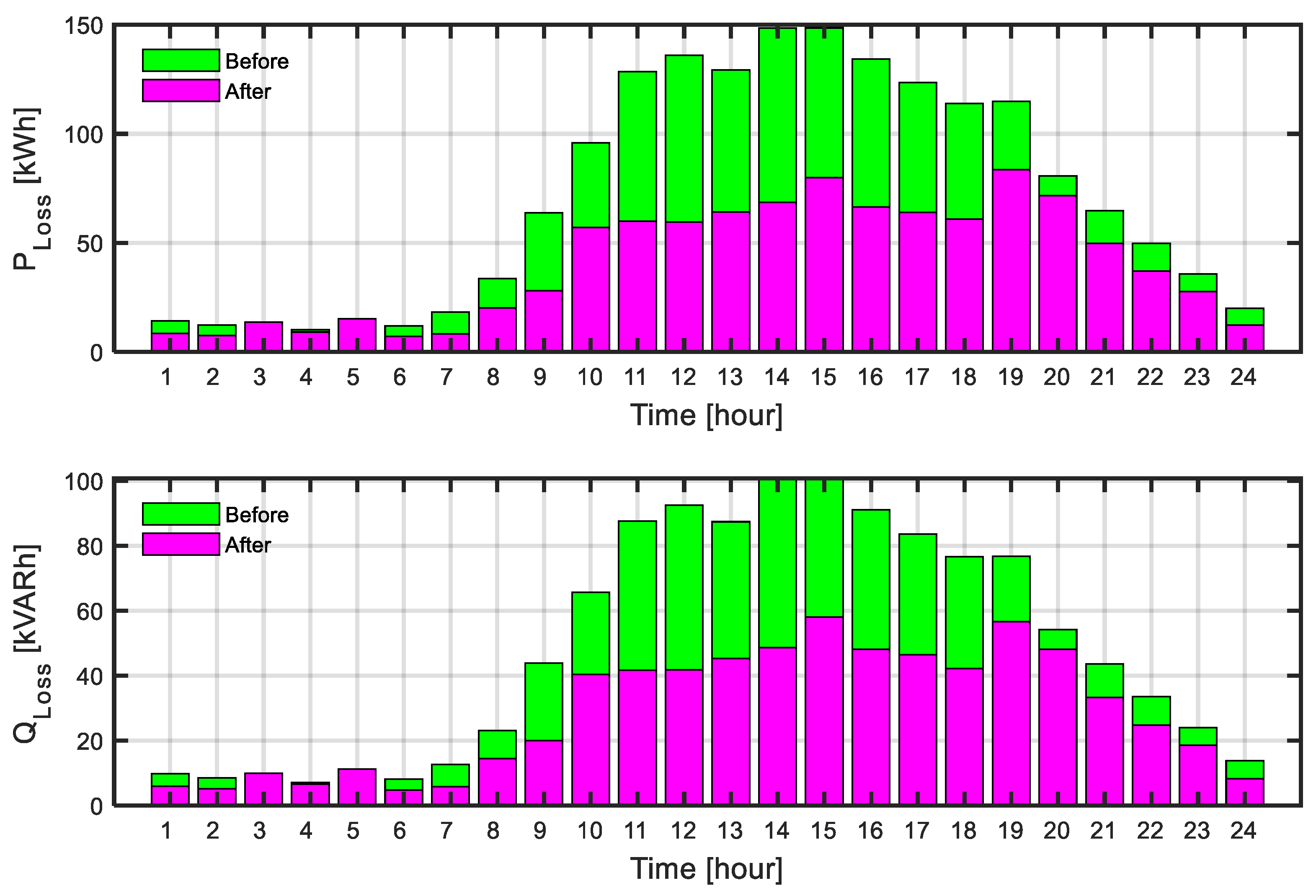

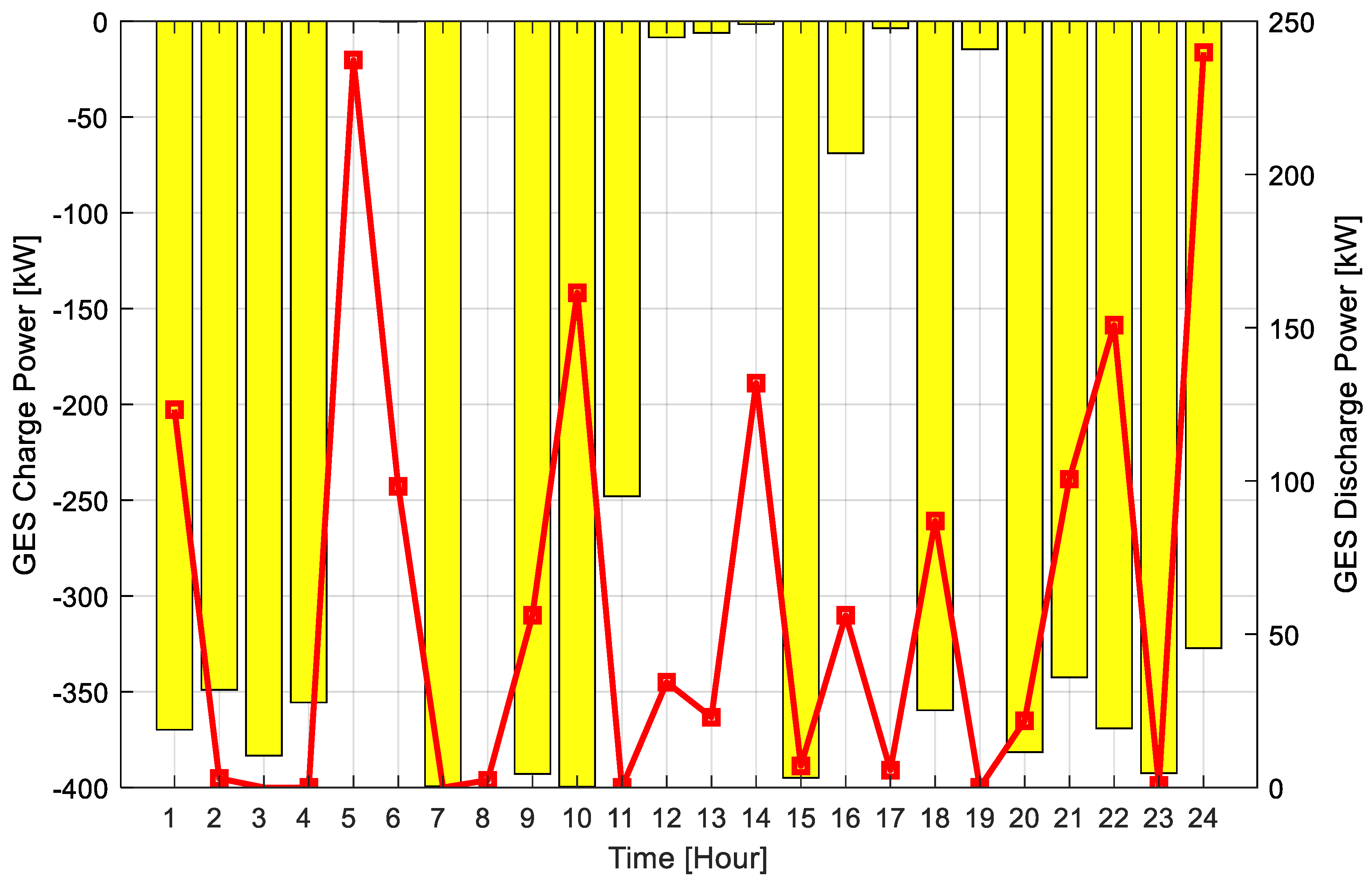

3.4. Results of Scenario Three

3.5. Results of Scenario Four

- It invests in slightly larger WT/PV/GES units—increased investment cost—to make sure it is reliable in a wider range of conditions.

- It may be more reliable but possibly more expensive or pollute the grid power as a buffer, increasing operational costs and emissions.

- Optimal placement and sizing under uncertainty yield different power flow patterns that can lead to higher expected energy losses.

4. Comparison with Previous Studies

5. Conclusions

- The proposed MO-EWAA was rigorously tested against conventional MO-WAA, MO-PSO, NSGA-II, and MO-GWO. As evidenced by the results, MO-EWAA demonstrated superior performance by achieving the lowest active power losses (847.89 kW), the lowest investment and operational cost (USD 1,295,191), and the lowest pollution cost (USD 1,024,341,093). This practical superiority is complemented by its exceptional optimization metrics, where it achieved the highest Hypervolume (0.9263) and lowest Spacing (0.2029), confirming its superior ability to find a well-distributed and high-quality set of Pareto-optimal solutions. This combination of best-in-class practical results and robust multi-objective performance solidifies MO-EWAA as a highly effective and reliable optimizer for complex stochastic multi-objective problems in distribution networks.

- GES integration with renewable resources proved to be a game-changing strategy. As can be viewed, Scenario Three, based entirely on operation via GES, has active and reactive power losses reduced by about 50.40% and 50.14%, respectively, demonstrating far superior performance compared to demand response-based scenarios—Scenario Two or renewable-alone-based Scenario One.

- The application of 2PEM in Scenario Four resulted in a power system where the uncertainties of renewable generation and load were quite pronounced. Although the stochastic model resulted in necessary increases in investment (3.94%) and operational costs—e.g., a 6.50% increase in energy loss cost—to ensure a robust system, it was a far more reliable and realistic result from the planning perspective, quantifying the cost of uncertainty and the value of risk-aware decisions.

- The MO-EWAA also showed the best computational performance by converging to the final solution much quicker compared to others, while having a standard deviation less than 1% over different runs; this confirms reliability and consistency against MO-WAA (1.2644%) and MO-PSO (1.2193%).

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Standard Models for PV, Wind, and Demand Response

Appendix A.1. Photovoltaic (PV) Model

Appendix A.2. Wind Turbine (WT) Model

Appendix A.3. Demand Response (DR) Model

References

- Nowdeh, S.A.; Davoudkhani, I.F.; Moghaddam, M.H.; Najmi, E.S.; Abdelaziz, A.Y.; Ahmadi, A.; Razavi, S.E.; Gandoman, F.H. Fuzzy multi-objective placement of renewable energy sources in distribution system with objective of loss reduction and reliability improvement using a novel hybrid method. Appl. Soft Comput. 2019, 77, 761–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naderipour, A.; Nowdeh, S.A.; Saftjani, P.B.; Abdul-Malek, Z.; Mustafa, M.W.B.; Kamyab, H.; Davoudkhani, I.F. Deterministic and probabilistic multi-objective placement and sizing of wind renewable energy sources using improved spotted hyena optimizer. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 286, 124941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naderipour, A.; Abdul-Malek, Z.; Hajivand, M.; Seifabad, Z.M.; Farsi, M.A.; Nowdeh, S.A.; Davoudkhani, I.F. Spotted hyena optimizer algorithm for capacitor allocation in radial distribution system with distributed generation and microgrid operation considering different load types. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 2728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davoudkhani, I.F.; Zishan, F.; Mansouri, S.; Abdollahpour, F.; Grisales-Noreña, L.F.; Montoya, O.D. Allocation of renewable energy resources in distribution systems while considering the uncertainty of wind and solar resources via the multi-objective Salp Swarm algorithm. Energies 2023, 16, 474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzaei, M.A.; Yazdankhah, A.S.; Mohammadi-Ivatloo, B. Stochastic security-constrained operation of wind and hydrogen energy storage systems integrated with price-based demand response. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2019, 44, 14217–14227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Shi, Y.; Maleki, A.; Rosen, M.A. Optimal location and size of a grid-independent solar/hydrogen system for rural areas using an efficient heuristic approach. Renew. Energy 2020, 156, 1203–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Y.; Li, Q.; Wang, T.; Yin, L.; Chen, W.; Liu, H. Optimal planning of cross-regional hydrogen energy storage systems considering the uncertainty. Appl. Energy 2022, 326, 119973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.F.; Xie, J.Z.; Fan, Y.F.; Qiu, J. Potential of different forms of gravity energy storage. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2024, 64, 103728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emrani, A.; Achour, Y.; Sanjari, M.J.; Berrada, A. Adaptive energy management strategy for optimal integration of wind/PV system with hybrid gravity/battery energy storage using forecast models. J. Energy Storage 2024, 96, 112613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Shafiullah, G.M.; Das, C.K.; Wong, K.W. Optimal allocation of battery energy storage systems to improve system reliability and voltage and frequency stability in weak grids. Appl. Energy 2025, 377, 124541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ALAhmad, A.K. Voltage regulation and power loss mitigation by optimal allocation of energy storage systems in distribution systems considering wind power uncertainty. J. Energy Storage 2023, 59, 106467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elseify, M.A.; Kamel, S.; Nasrat, L. An improved moth flame optimization for optimal DG and battery energy storage allocation in distribution systems. Clust. Comput. 2024, 27, 14767–14810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belbachir, N.; Kamel, S.; Hassan, M.H.; Zellagui, M. Optimizing energy management of hybrid wind generation-battery energy storage units with long-term memory artificial hummingbird algorithm under daily load-source uncertainties in electrical networks. J. Energy Storage 2024, 78, 110288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautam, R.; Khadka, S.; Malla, T.B.; Bhattarai, A.; Shrestha, A.; Gonzalez-Longatt, F. Assessing uncertainty in the optimal placement of distributed generators in radial distribution feeders. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2024, 230, 110249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fathy, A.; Yousri, D.; El-Saadany, E.F. A novel memory-based artificial gorilla troops optimizer for installing biomass distributed generators in unbalanced radial networks. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2024, 68, 103885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javad Aliabadi, M.; Radmehr, M. Optimization of hybrid renewable energy system in radial distribution networks considering uncertainty using meta-heuristic crow search algorithm. Appl. Soft Comput. 2021, 107, 107384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Fosso, O.B.; Marafioti, G. Probabilistic planning of distribution networks with optimal DG placement under uncertainties. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2023, 59, 2731–2741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elseify, M.A.; Mostafa, R.R.; Hashim, F.A.; Domínguez-García, J.L.; Kamel, S. Optimal scheduling of photovoltaic and battery energy storage in distribution networks using an ameliorated sand cat swarm optimization algorithm: Economic assessment with different loading scenarios. J. Energy Storage 2025, 116, 116026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emrani, A.; Berrada, A.; Bakhouya, M. Modeling and performance evaluation of the dynamic behavior of gravity energy storage with a wire rope hoisting system. J. Energy Storage 2021, 33, 102154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Wu, J.; Zhu, R.; Kong, D.; Guo, H. Double layers optimal scheduling of distribution networks and photovoltaic charging and storage station cluster based on leader follower game theory. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, L.; Liu, J.; Lu, H.; Liu, B.; Chen, Y.; Wu, S. Robust operation of distribution network based on photovoltaic/wind energy resources in condition of COVID-19 pandemic considering deterministic and probabilistic approaches. Energy 2022, 261, 125322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muralikrishnan, G.; Preetha, K.; Selvakumaran, S.; Hariramakrishnan, P. Optimal planning of photovoltaic, wind turbine and battery to mitigate flicker and power loss in distribution network. J. Energy Storage 2025, 116, 116034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emrani, A.; Berrada, A.; Ameur, A.; Bakhouya, M. Assessment of the round-trip efficiency of gravity energy storage system: Analytical and numerical analysis of energy loss mechanisms. J. Energy Storage 2022, 55, 105504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franklin, M.; Fraenkel, P.; Yendell, C.; Apps, R. Gravity energy storage systems. In Storing Energy; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 91–116. [Google Scholar]

- Dixit, S.; Singh, P.; Ogale, J.; Bansal, P.; Sawle, Y. Energy management in microgrids with renewable energy sources and demand response. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2023, 110, 108848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horrillo-Quintero, P.; García-Triviño, P.; Ugalde-Loo, C.E.; Hosseini, E.; García-Vázquez, C.A.; Tostado, M.; Jurado, F.; Fernández-Ramírez, L.M. Efficient energy dispatch in multi-energy microgrids with a hybrid control approach for energy management system. Energy 2025, 317, 134599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habibi, S.; Effatnejad, R.; Hedayati, M.; Hajihosseini, P. Stochastic energy management of a microgrid incorporating two-point estimation method, mobile storage, and fuzzy multi-objective enhanced grey wolf optimizer. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Jiang, L.; Wan, W.; Wang, K.; Bai, Y. Fuzzy multi-objective optimization model for carbon emissions during water supply based on life cycle assessment. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2024, 72, 104027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qtaish, A.; Braik, M.; Albashish, D.; Alshammari, M.T.; Alreshidi, A.; Alreshidi, E.J. Enhanced coati optimization algorithm using elite opposition-based learning and adaptive search mechanism for feature selection. Int. J. Mach. Learn. Cybern. 2025, 16, 361–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; De Waele, W. Weighted average algorithm: A novel meta-heuristic optimization algorithm based on the weighted average position concept. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2024, 305, 112564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, R.; Xu, Z.; Yu, L.; Wei, T. EABC-AS: Elite-driven artificial bee colony algorithm with adaptive population scaling. Swarm Evol. Comput. 2025, 94, 101893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Chen, X. Elite-driven grey wolf optimization for global optimization and its application to feature selection. Swarm Evol. Comput. 2025, 92, 101795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kan, R.; Xu, Y.; Li, Z.; Lu, M. Calculation of probabilistic harmonic power flow based on improved three-point estimation method and maximum entropy as distributed generators access to distribution network. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2024, 230, 110197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, N.B.; Das, D. Probabilistic optimal power allocation of dispatchable DGs and energy storage units in a reconfigurable grid-connected CCHP microgrid considering demand response. J. Energy Storage 2023, 72, 108207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alghamdi, A.S.; Alanazi, M.; Alanazi, A.; Qasaymeh, Y.; Zubair, M.; Awan, A.B.; Ashiq, M.G.B. Stochastic Programming for Hub Energy Management Considering Uncertainty Using Two-Point Estimate Method and Optimization Algorithm. Comput. Model. Eng. Sci. 2023, 137, 2163–2192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nassar, Y.F.; El-Khozondar, H.J.; Khaleel, M.M.; Ahmed, A.A.; Alsharif, A.H.; Elmnifi, M.H.; Salem, M.A.; Mangir, I. Design of reliable standalone utility-scale pumped hydroelectric storage powered by PV/Wind hybrid renewable system. Energy Convers. Manag. 2024, 322, 119173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deb, K.; Pratap, A.; Agarwal, S.; Meyarivan, T. A fast and elitist multiobjective genetic algorithm: NSGA-II. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 2002, 6, 182–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirjalili, S.; Saremi, S.; Mirjalili, S.M.; Coelho, L.D.S. Multi-objective grey wolf optimizer: A novel algorithm for multi-criterion optimization. Expert Syst. Appl. 2016, 47, 106–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, F.; Bu, X. A new cloud-stochastic framework for optimized deployment of hydrogen storage in distribution network integrated with renewable energy considering hydrogen-based demand response. Energy 2025, 316, 134483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shayeghi, H.; Davoudkhani, I.F. Fuzzy-stochastic planning and optimization of mobile solid-state hydrogen storage in renewable-powered distribution networks. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 168, 151048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Ref. | Focus/Method | Limitations/Gaps | Addressed in This Work |

|---|---|---|---|

| [10] | BESS allocation using AGWO for frequency/voltage stability. | Deterministic; focuses on BESS, not GES. | ✓ |

| [11] | MOPSO for wind uncertainty and storage dispatch. | Does not integrate GES or GES-based DR. | ✓ |

| [12] | IMFO for PV/battery scheduling to minimize loss. | Deterministic model; limited storage technology. | ✓ |

| [13] | MOMAHA for WT and BESS placement. | Deterministic; does not consider GES. | ✓ |

| [14] | PMOMVO for DG and BESS allocation. | Deterministic model. | ✓ |

| [15] | Virtual Participation Theory for loss reduction. | Focused on loss allocation, not integrated resource planning. | -- |

| [16] | Probabilistic allocation (MCS) for Wind/PV/Battery. | Uses MCS, which is computationally heavy; focuses on BESS. | ✓ |

| [17] | Probabilistic framework for DG placement. | Does not incorporate energy storage or DR. | ✓ |

| [18] | Differential Evolution for solar-wind swapping stations. | System-level focus, not distribution network operation. | -- |

| [19] | Turbulent Flow of Water-based Optimization for Wind/Solar. | Crisis-context planning; deterministic. | -- |

| [20] | Gaussian Pied Kingfisher algorithm for PV/WT/Battery. | Focus on power quality; deterministic approach. | ✓ |

| [21] | Sand Cat Swarm Optimization for PV/Battery scheduling. | Considers randomness but with a single heuristic; uses BESS. | ✓ |

| [22] | AOA for DG placement with a new VSI. | Deterministic; no integrated storage or DR model. | ✓ |

| Parameter | Photovoltaic | Wind Turbine | GES |

|---|---|---|---|

| Investment cost (USD) | 517 | 1200 | 1350 |

| Operation and maintenance cost (USD/kWh) | 5.17 | 12 | 13.5 |

| Maximum capacity (kW) | 2000 | 2000 | 400 |

| Minimum capacity (kW) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Parameter | Main Grid |

|---|---|

| Cost of energy loss (USD/kWh) | 0.06 |

| Grid cost (USD/kWh) | 0.096 |

| Emission cost (USD/kg/year) | 57 |

| NOx (kg/kWh) | 0.0023 |

| SO2 (kg/kWh) | 0.0036 |

| CO2 (kg/kWh) | 0.9215 |

| Parameter | Base Network | Scenario One Values |

|---|---|---|

| WT Site and Capacity | -- | @11/676 kW |

| PV Site and Capacity | -- | @30/1232 kW |

| GES Site and Capacity | -- | -- |

| Active Power Losses (kW) | 1709.597 | 1009.931 |

| Reactive Power Losses (kVAR) | 1159.583 | 684.857 |

| Cost of Active Energy Loss (USD) | 37,440.173 | 22,117.481 |

| Pollution Cost (USD) | 1,040,967,338 | 1,027,467,587 |

| Investment and Operation Cost (USD) | -- | 1,021,216.180 |

| HES Cost (USD) | -- | -- |

| Parameter | Base Network | Scenario Two Values |

|---|---|---|

| WT Site and Capacity | -- | @14/459 kW |

| PV Site and Capacity | -- | @29/1034 kW |

| GES Site and Capacity | -- | -- |

| Active Power Losses (kW) | 1709.597 | 992.244 |

| Reactive Power Losses (kVAR) | 1159.583 | 678.560 |

| Cost of Active Energy Loss (USD) | 37,440.173 | 21,730.358 |

| Pollution Cost (USD) | 1,040,967,338 | 1,026,530,271 |

| Investment and Operation Cost (USD) | -- | 757,111 |

| DR Cost (USD) | -- | 43,901 |

| HES Cost (USD) | -- | -- |

| Parameter | Base Network | MO-EWAA | MO-WAA | MO-PSO | NSGA-II | MO-GWO |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT Site and Capacity | -- | @29/959 kW | @26/973 kW | @29/971 kW | @29/978 kW | @29/968 kW |

| PV Site and Capacity | -- | @11/1268 kW | @8/1305 kW | @13/1255 kW | @8/1311 kW | @13/1259 kW |

| GES Site and Capacity | -- | @20/211.05 kW | @11/196.58 kW | @20/215.40 kW | @20/192.38 kW | @20/219.01 kW |

| Active Power Losses (kW) | 1709.597 | 847.890 | 863.36 | 856.910 | 861.574 | 858.311 |

| Reactive Power Losses (kVAR) | 1159.583 | 578.146 | 610.20 | 589.372 | 607.033 | 591.248 |

| Cost of Active Energy Loss (USD) | 37,440.173 | 18,568.800 | 18,907.584 | 18,766.329 | 18,868.470 | 18,797.011 |

| Pollution Cost (USD) | 1,040,967,338 | 1,024,341,093 | 1,024,629,114 | 1,024,475,662 | 1,024,527,816 | 1,024,493,276 |

| Investment and Operation Cost (USD) | -- | 1,295,191 | 1,318,403 | 1,303,227 | 1,322,791 | 1,302,425 |

| DR Cost (USD) | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| HES Cost (USD) | -- | 11,542 | 12,092 | 11,859 | 12,165 | 11,923 |

| Hypervolume | 0.9263 | 0.8927 | 0.9058 | 0.9042 | 0.9046 | |

| Spacing | 0.2029 | 0.2573 | 0.2210 | 0.2275 | 0.2234 |

| Parameter | MO-EWAA (Scenario Three) | MO-EWAA (Scenario Four) | MO-WAA (Scenario Four) | MO-PSO (Scenario Four) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT Site and Capacity | @29/959 kW | @27/691 kW | @9/871 | @6/1508 kW |

| PV Site and Capacity | @11/1268 kW | @11/2000 kW | @28/1697 kW | @15/786 kW |

| GES Site and Capacity | @20/211.05 kW | @2/239.83 kW | @3/43 kW | @2/41 kW |

| Active Power Losses (kW) | 847.890 | 899.74 | 916.052 | 909.923 |

| Reactive Power Losses (kVAR) | 578.146 | 615.724 | 641.285 | 590.879 |

| Cost of Active Energy Loss (USD) | 18,568.800 | 19,704.306 | 20,061.538 | 19,927.314 |

| Pollution Cost (USD) | 1,024,341,093 | 1,045,406,492 | 1,045,626,527 | 1,045,573,112 |

| Investment and Operation Cost (USD) | 1,295,191 | 1,346,285 | 1,454,855 | 1,388,495 |

| DR Cost (USD) | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| HES Cost (USD) | 11,542 | 13,117 | 13,465 | 13,286 |

| Computational Time (s) | -- | 279 | 317 | 305 |

| Standard Deviation (%) | -- | 0.8571 | 1.2644 | 1.2193 |

| Parameter | MO-EWAA | MOEEDO [39] | MOCPO [40] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Active Power Losses (kW) | 50.40 | 41.96 | 44.03 |

| Reactive Power Losses (kVAR) | 50.14 | 41.48 | 43.05 |

| Cost of Active Energy Loss (USD) | 50.40 | 41.96 | 44.03 |

| Pollution Cost (USD) | 1.60 | 1.27 | -- |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alghamdi, A.S. A Stochastic Multi-Objective Optimization Framework for Integrating Renewable Resources and Gravity Energy Storage in Distribution Networks, Incorporating an Enhanced Weighted Average Algorithm and Demand Response. Sustainability 2025, 17, 11108. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411108

Alghamdi AS. A Stochastic Multi-Objective Optimization Framework for Integrating Renewable Resources and Gravity Energy Storage in Distribution Networks, Incorporating an Enhanced Weighted Average Algorithm and Demand Response. Sustainability. 2025; 17(24):11108. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411108

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlghamdi, Ali S. 2025. "A Stochastic Multi-Objective Optimization Framework for Integrating Renewable Resources and Gravity Energy Storage in Distribution Networks, Incorporating an Enhanced Weighted Average Algorithm and Demand Response" Sustainability 17, no. 24: 11108. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411108

APA StyleAlghamdi, A. S. (2025). A Stochastic Multi-Objective Optimization Framework for Integrating Renewable Resources and Gravity Energy Storage in Distribution Networks, Incorporating an Enhanced Weighted Average Algorithm and Demand Response. Sustainability, 17(24), 11108. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411108