Abstract

The significance of organizational psychology within the hospitality sector has garnered increasing scholarly attention. This study seeks to examine the contextual effects of green organizational climate in international tourist hotels through a three-level analytical framework. Specifically, it investigates the influence of organizational-level factors (green organizational climate), peer-level dynamics (workplace friendship), and individual-level attributes (Brilliant Quotient (BQ)) on employee job satisfaction. Empirical data were obtained from 68 international tourist hotels, comprising 623 supervisor surveys and 6230 employee questionnaires. The findings indicate that (1) employees’ excellence competency, supervisors’ emphasis on the universality of workplace friendships, and responsibility-oriented goals exert a direct influence on employee job satisfaction; (2) the universality of workplace friendship significantly moderates the relationship between excellence, execution capability, and job satisfaction; (3) responsibility goals, reward systems, and decision-making structures function as critical moderating variables; and (4) responsibility goals directly affect supervisors’ prioritization of workplace friendship.

1. Introduction

Amid growing global awareness of climate change and the advancement of sustainable development goals, the international tourism hotel sector confronts unprecedented environmental challenges. Include the possible differences between hotels that accommodate international travelers and hotels that serve domestic travelers. The selection of international hotels as the focus of this study is justified by five primary considerations. First, the hotel industry exerts a substantial environmental impact, characterized by high consumption of energy and water resources, as well as significant waste generation. The adoption of green management practices within this sector has been demonstrated to yield notable environmental and economic advantages [1]. Second, the implementation of environmentally sustainable practices is closely linked to operational benefits and holds considerable practical significance for management. Specifically, green initiatives can lead to cost reductions while simultaneously enhancing customer satisfaction and strengthening brand equity, thereby increasing their acceptability and applicability among managerial personnel [2]. Third, there exists pronounced pressure stemming from customer environmental expectations and the need for market differentiation; international travelers increasingly prioritize sustainable services and environmental certifications, anticipating that global hotel chains will actively promote green climates and practices [3]. Fourth, the hotel context presents clear multi-level interactions among organizational units, peer groups, and individual employees, rendering it well-suited for cross-level research designs. Frequent interactions among internal departments—such as front desk, housekeeping, and food and beverage—facilitate the investigation of how a green organizational climate influences employee behavior through both organizational and peer effects [4]. Finally, the study of green climate within international hotels possesses a strong linkage between academic research and practical application, offering substantial potential for broader dissemination. As a representative segment of the service industry, insights derived from this context can be adopted or adapted by other service sectors, thereby providing high external validity and valuable policy implications [5]. Recent research indicates that buildings contribute approximately 1% of global carbon emissions, with the hotel industry’s energy consumption surpassing that of other building categories. This has led 83% of travelers to regard sustainable tourism as critically important. Within this context, the concept of green organizational climate—an essential indicator of internal environmental management practices—not only shapes employees’ pro-environmental behaviors but also directly influences organizational sustainability performance.

This study seeks to develop a theoretical framework spanning three hierarchical levels—organizational, peer, and individual—to examine the network effects of green organizational climate in international tourism hotels. Additionally, it investigates the combined influence of workplace friendship and brilliance quotient (BQ) on employees’ job satisfaction.

The term “green” predominantly refers to sustainable development, environmental initiatives, and carbon reduction objectives; however, it does not comprehensively elucidate the fundamental concept of a “green organization” in terms of corporate culture or governance principles. Therefore, the green organizational climate should be conceptualized as the process through which an organization integrates sustainability goals into its central decision-making framework at the organizational level. The theoretical foundation and measurement of green organizational climate derive from an extension of traditional organizational climate theory, emphasizing shared perceptions and behavioral norms related to environmental protection within organizations. Ref. [6] asserts that the green organizational climate is advanced through Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) criteria, which have evolved beyond serving merely as a critical benchmark for assessing corporate sustainability performance to becoming a significant determinant in shaping consumer behavior and investor assessments of corporate value. The recently developed measurement scale for the green organizational climate, constructed through a rigorous three-stage scale development methodology, delineates four principal dimensions: green economic climate, green social climate, green digital climate, and green bureaucratic climate. In the hotel industry context, ref. [7] surveyed 254 employees from environmentally certified hotels in Taiwan, revealing that perceptions of green organizational climate significantly affect employees’ environmental behaviors. However, recent studies suggest that while total quality management practices may reinforce green organizational culture, green behaviors do not necessarily translate directly into enhanced organizational performance, indicating a potential trade-off between environmental and business objectives [8,9]. Given that organizations are inherently multilevel nested systems, inferring individual attributes solely from organizational-level data risks ecological fallacy, whereas explaining organizational variables based on individual-level attributes may result in atomistic fallacy [10,11,12].

From the perspective of workplace friendship, which constitutes a vital component of informal social networks among employees, recent organizational behavior research has distinguished two primary dimensions: friendship opportunity and friendship prevalence. Friendship opportunity pertains to the frequency of informal interactions and social activities among colleagues, whereas friendship prevalence measures the extent and pervasiveness of actual friendship relationships within the organization [13]. Ref. [14] argue that informal workplace relationships are directly associated with employee job satisfaction, irrespective of formal work practices, underscoring the critical role of green organizational climate in shaping environmental behaviors. Moreover, workplace friendship not only directly enhances employees’ positive emotions and well-being but also amplifies positive affective states through mechanisms such as workplace recreational activities and colleague socialization [15]. Thus, a comprehensive green organizational theory necessitates integrating both macro- and micro-level perspectives.

Recognizing organizations as hierarchical nested systems [16], neglecting their multilevel nature when constructing and analyzing organizational phenomena may lead to level fallacy [11,12]. Ref. [17] further demonstrated a positive association between colleague friendship and team-level conceptual and problem-solving skills, suggesting that workplace friendship not only influences job satisfaction but may also mediate the relationship between individual brilliance quotient and job satisfaction. Regarding the relationship between brilliance quotient and job satisfaction, BQ encompasses two principal dimensions: charisma and execution ability, which have garnered increasing attention in human resource management. Charisma includes personal presentation, attractiveness, and creative performance, while execution ability involves efficient plan implementation, goal attainment, and excellence in service quality [18,19]. In the tourism hotel industry, employees’ BQ not only impacts service quality but also directly relates to customer satisfaction and organizational competitive advantage.

Research on job satisfaction indicates that factors such as compensation, self-expectations, and work ability collectively influence employees’ overall work attitudes [20,21]. Ref. [22] examining the hotel industry in Jaipur, identified pay rewards, career development opportunities, and working environment conditions as key determinants of employee job satisfaction.

The theoretical imperative for a multilevel analytical framework arises from the hierarchical and interactive nature of organizational behavior phenomena. Single-level analyses often fail to capture the complexity of inter-variable relationships. Consequently, acknowledging level-specific analyses is crucial; however, few studies within tourism and hospitality integrate factors across multiple levels to examine their joint effects on outcome variance. To model these organizational interactions appropriately, scholars advocate for multilevel methodologies that ensure accurate measurement and utilization of organizational-level effects [11,12,23,24,25]. For instance, ref. [26] employing hierarchical linear modeling on data from 538 employees across 24 hotels, found that service climate mediates the relationship between empowering leadership and employees’ service-oriented behaviors, with internal service quality of external departments enhancing this effect.

Recent reviews of multilevel analyses reveal that although such research in hotel management has increased substantially since 2017, challenges persist, including mismatches between theoretical constructs and measurement levels, insufficient transparency, incorrect model specifications, and limited sample sizes at higher organizational levels [12]. Building upon these theoretical and empirical insights, this study proposes a three-level research framework encompassing the organizational level (green organizational climate), peer level (workplace friendship), and individual level (brilliance quotient) to investigate their combined effects on job satisfaction. The research hypotheses include: (1) assessing the direct effect of brilliance quotient on job satisfaction; (2) analyzing the influence of workplace friendship on employee job satisfaction; (3) exploring the direct effects of green organizational climate on job satisfaction and workplace friendship; and (4) examining the moderating effects among variables across different levels.

By employing hierarchical linear modeling, this study aims to offer practical recommendations for human resource management and organizational development within the international tourism hotel industry, while contributing to the academic discourse on multilevel organizational behavior theory.

Accordingly, the objectives of this study are as follows:

- (1)

- To examine the impact of employees’ brilliance quotient on job satisfaction in international tourism hotels.

- (2)

- To analyze the influence of workplace friendship on employees’ job satisfaction in international tourism hotels.

- (3)

- To investigate the direct effect of green organizational climate on employees’ job satisfaction in international tourism hotels.

- (4)

- To explore the direct effect of green organizational climate on peer workplace friendship in international tourism hotels.

- (5)

- To assess the moderating effect of workplace friendship on the relationship between employees’ brilliance quotient and job satisfaction in international tourism hotels.

- (6)

- To evaluate the moderating effect of green organizational climate on the relationship between employees’ brilliance quotient and job satisfaction in international tourism hotels.

- (7)

- To examine the moderating effect of green organizational climate on the interplay among workplace friendship, employees’ brilliance quotient, and job satisfaction in international tourism hotels.

- (8)

- Based on the empirical findings, to propose actionable recommendations to assist international tourism hotel operators in understanding employees’ perceptions of green organizational climate, workplace friendship, and brilliance quotient, thereby enhancing job satisfaction and improving work quality.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Theory of Green Organizational Climate and Related Research

The concept of green organizational climate is broadly defined by scholars as the collective perception of organizational members regarding their work environment, which subsequently influences employee motivation and behavior. Although interpretations vary, the construct generally encompasses the following attributes [6,27]: (1) it is an organizational characteristic rather than an individual’s preference or evaluation; (2) its components and dimensions are collective rather than individual; (3) the unit of analysis pertains to the organizational system or its subunits rather than individual employees; and (4) it is accompanied by diverse cognitive responses from members that affect their behavior [28]. Many studies adopt the nine dimensions of organizational climate developed by [29] to measure green organizational climate [8]. This study similarly employs these dimensions, adapted for employees in the hotel industry, as the primary framework. Incorporating the concept of a “green organization” as a fundamental element of corporate culture or governance framework. Beyond its foundation in the conventional conceptualization of organizational climate, the questionnaire additionally encompasses environmental themes, such as organizational values, the promotion of employee environmental awareness, and the incorporation of systematic decision-making processes. These dimensions are defined as follows [9,28]:

- (1)

- Structure: The extent to which individuals perceive constraints within the group, such as green regulations and procedural restrictions; the degree to which the organization emphasizes formal rules versus a more relaxed or strict atmosphere.

- (2)

- Responsibility: The degree to which individuals feel empowered to make decisions independently, particularly concerning green environmental tasks and their effective management.

- (3)

- Reward: The perception that successful performance on tasks, including green initiatives, will be fairly rewarded; the fairness and reasonableness of compensation and promotion policies, and the influence of reward or punishment systems on member perceptions.

- (4)

- Risk: The extent to which individuals perceive risk and challenge in green-related work; whether the organization encourages calculated risk-taking or prioritizes safety and conservatism.

- (5)

- Warmth: The overall harmony among personnel regarding green issues; the emphasis on positive interpersonal relations, presence of informal social groups, and the nature of colleague interactions.

- (6)

- Support: The degree of mutual assistance perceived among supervisors and colleagues in green-related work, including trust and support from supervisors.

- (7)

- Standard: Individuals’ perceptions of the importance of organizational goals and performance standards related to green issues; the challenge level of individual and group goals and the value placed on work performance.

- (8)

- Conflict: The extent to which differing opinions on green issues are openly addressed or suppressed among supervisors and colleagues.

- (9)

- Identity: The sense of belonging individuals feel toward the organization concerning green issues; the degree to which they feel valued and cherish their status within the group.

2.2. Theoretical Foundations and Related Studies on Workplace Friendship

Workplace friendship, a vital component of informal internal organizational networks, plays a significant role in public relations and has become a focal topic in contemporary organizational behavior research. Grounded in communal relationship theory, workplace friendship is defined as an unconditional caring relationship based on emotional interaction, characterized by reciprocity, equality, and spontaneity [30]. This relationship entails mutual commitment, trust, and shared work values, serving as a critical buffer during organizational change and challenges. To effectively measure employees’ cognitive perceptions and the importance of workplace friendship for individual and organizational effectiveness, ref. [31] synthesized perspectives from [32] to develop a construct-valid two-dimensional workplace friendship scale, comprising friendship prevalence and friendship opportunity [15]. This scale comprehensively captures workplace friendship within organizations. Based on these core concepts, workplace friendship functions as a key mediator of individual and organizational management effectiveness. A 2025 KPMG survey highlighted the economic value of workplace friendship: 57% of employees would accept a 10% salary reduction to work alongside close colleagues, equating to a 20% salary premium for workplace relationships [33]. Furthermore, 87% of employees regard close work friendships as extremely important, marking a 6-percentage-point increase since November 2024, indicating a growing emphasis on workplace friendship. Workplace friendship exerts dual effects: positively, it significantly enhances productivity and motivation, enabling employees to exceed basic job requirements [33]. In nursing research, workplace friendship mitigates the adverse effects of workplace bullying on knowledge hiding, suggesting that fostering a friendship culture among nurses is an effective strategy to reduce bullying [34]. Conversely, workplace friendship may engender role conflict when workplace norms of fairness clash with friendship norms of emotion and favoritism, leading to role strain, psychological resource depletion, and uncivil behavior [30]. Relationship motivation cognition critically determines whether workplace friendship activates communal or exchange norms, thereby promoting or inhibiting proactive helping behavior [35]. Contemporary research adopts integrative approaches to elucidate the complex mechanisms of workplace friendship. Some scholars incorporate workplace friendship into the contextual factors of work passion, combining dimensions such as passion, intimacy, and decisional commitment to examine their comprehensive impact on organizational effectiveness [36]. This integrative perspective enhances understanding of the multifaceted roles of workplace friendship in modern organizations, providing refined theoretical guidance for organizational management.

2.3. Theoretical Foundations and Related Research on Brilliant Quotient (BQ)

Brilliant Quotient (BQ) is a recently emerging mainstream concept that assesses an individual’s abilities and internal and external traits enabling them to excel in the workplace. Originating from the U.S.-based Koman Management Consulting Company, the theory posits that workplace success depends on the integrated performance of professionalism, image, and visibility [18,37]. The BQ framework encompasses self-awareness, self-management, interpersonal relationship management, social perception, and external behavioral performance, integrating perspectives related to work performance and workplace friendship [37]. The theoretical model comprises three dimensions—Beauty, Brain, and Behavior—collectively termed the 3B model. ‘Beauty’ refers to an individual’s aesthetic cognition, including aesthetic confidence, self-interpretation, environmental influence perception, and precise self-assessment. ‘Brain’ integrates IQ and EQ, encompassing professional competence, innovation ability, creative motivation, self-management motivation, achievement motivation, emotional control, interpersonal management, affinity, empathy, and positivity. ‘Behavior’ emphasizes self-observation from others’ perspectives, requiring social perception, interpersonal management, and self-management, expressed through body language and external behaviors that influence others and the organization [18,19]. Empirical research by [37] reported that Harvard Business Management Company’s application of the BQ scale among Taiwanese workers revealed BQ as a competitive advantage in the service industry. Key findings include: (1) Taiwan’s service workforce has entered a ‘quality’ era, elevating the importance of frontline service personnel’s BQ; (2) companies value BQ performance, which correlates positively with job position; and (3) roles involving external communication or frequent customer contact tend to exhibit higher personal BQ [18,19]. Ref. [38] emphasized that beyond professional skills, service personnel’s behavior and attitude during service interactions directly affect customer perceptions and company evaluations. Their study found employees perform better in the ‘Brain’ and ‘Beauty’ dimensions of BQ, while ‘Behavior’ is relatively weaker, suggesting managerial focus on enhancing employees’ behavioral capabilities [38] (Lin Caiyuan & Hong Ruiying, 2008). Consequently, establishing appropriate standards to measure employees’ capacity to excel—analogous to green organizational climate’s ‘green for others’ and ‘green for self’ constructs [39]—can facilitate assessment of employees’ internal and external cultivation and performance, thereby improving service quality, a matter warranting industry attention. Regarding organizational effectiveness, ref. [38] conducted BQ research on Taiwan’s three major hotel chains using cluster analysis, revealing significant differences among high, medium, and low BQ groups in internal marketing cognition, organizational commitment, and organizational citizenship behavior, with the high BQ group outperforming others. This confirms that individual BQ positively influences organizational commitment and citizenship behavior [18], indicating that personal BQ can be internalized into corporate culture, thereby shaping overall corporate style and brand image.

2.4. Theoretical Foundations and Related Research on Job Satisfaction

The concept of job satisfaction originated from Mayo’s Hawthorne experiments (1927–1932). Ref. [40] first conceptualized it as employees’ psychological and physiological satisfaction with work environment factors, reflecting subjective responses to work situations. Job satisfaction manifests as employees’ degree of contentment derived from work, encompassing psychological and physiological dimensions related to promotion, job content, supervisors, compensation, work environment, and coworkers [41,42] defined job satisfaction as the congruence between employees’ feelings of fulfillment, realization of work value, and personal needs [43,44]. Theories on job satisfaction are broadly categorized into content theories, which explain influencing factors (e.g., Need Hierarchy Theory, Two-Factor Theory, ERG Theory), and process theories, which explore how expectations, needs, and values lead to satisfaction (e.g., Equity Theory, Expectancy Theory, Discrepancy Theory). Ref. [45] revised Maslow’s hierarchy into three needs: existence, relatedness, and growth. Ref. [42] further distinguished job satisfaction factors into job events (e.g., job value, rewards, work environment) and agents (individuals and others inside and outside the organization) [43]. Traditionally, organizations prioritized external customer satisfaction, often neglecting employees’ internal experiences [46]. However, satisfied employees are prerequisites for satisfying customers [44,47]. Employee dissatisfaction impedes the transmission of positive satisfaction to customers [48].

Ref. [49] identified job satisfaction components including fairness of distribution, managerial support, promotion opportunities, coworker friendship, and salary. Ref. [50] defined job satisfaction as an individual’s overall affective response to their job. Ref. [51] viewed it as employees’ subjective evaluation of job goals and expectations, influenced by role positioning, incentives, work environment, and management systems. Ref. [44] highlighted factors promoting job satisfaction: mentally challenging work, fair compensation, supportive environment, and promotion systems. Ref. [52] described job satisfaction as positive psychological fulfillment during work. Ref. [53] defined it as workers’ emotional responses toward their work, reflecting liking or satisfaction. Job satisfaction serves as a critical variable in organizational and management theories, functioning as both an outcome measure and predictor of organizational behaviors. For instance, ref. [48] employed job satisfaction as a mediator in examining the relationship between organizational learning and commitment in five-star hotels, finding significant positive effects of organizational learning on job satisfaction, with sub-dimensions such as information sharing, inquiry climate, and learning practice contributing positively. Ref. [54] expanded job satisfaction to include supervisor and coworker relationships, welfare, compensation, job meaning, and role development, encompassing ‘company treatment,’ ‘self-expectation,’ and ‘job ability’ factors [43,44]. Thus, job satisfaction is both an outcome and a contextual factor within green organizational climate. In summary, job satisfaction can be conceptualized as international tourist hotel employees’ emotional responses to their work, with positive emotions indicating satisfaction and negative emotions indicating dissatisfaction.

2.5. Employee-Level Factors (Brilliant Quotient) and Job Satisfaction in Hotels

Brilliant Quotient (BQ), encompassing beauty, emotional intelligence (EQ), intelligence quotient (IQ), and behavior, represents an individual’s capacity and internal and external traits to excel in the workplace [18,37]. Individual motivation and actions closely relate to workplace performance, thereby influencing job satisfaction [55]. Consequently, employees’ job satisfaction is associated with their beauty, EQ, IQ, and behavior. Moreover, BQ affects organizational behavior [38]; individuals with higher BQ demonstrate accurate self-assessment, superior EQ and affinity, and foster a more favorable work environment [56]. Job satisfaction encompasses intrinsic rewards, convenience, financial compensation, coworker relationships, promotion and development opportunities, and resource adequacy. Ref. [57] conceptualized job satisfaction antecedents as environmental attributes, occupational nature, and personal traits, with consequences including individual, organizational, and social responses [43,44]. Organizational behavior reflects internal employee cohesion, work atmosphere, integration, and communication, which are implicit and not readily observable by customers. Employee behavior effectively conveys the company’s philosophy to internal and external stakeholders. Thus, BQ integrates beauty and execution (brain and behavior) dimensions. Industry experts in international tourist hotels assert that higher BQ, due to superior beauty and execution, correlates directly with job satisfaction. Based on this literature, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 1:

Employees’ Brilliant Quotient in international tourist hotels positively influences job satisfaction.

2.6. Peer-Level Factors (Workplace Friendship) and Job Satisfaction in Hotels

Within public relations, workplace friendship is conceptualized as a job characteristic [58]. Research indicates that spontaneous workplace friendships enhance organizational team utilization and promote work effectiveness [31]. individuals with higher [59] emphasized that positive coworker relationships are vital for creating and sustaining a productive work environment. Employees with harmonious relationships perform better, suggesting organizations should select compatible employees [60]. In sum, workplace friendship positively influences individual professional excellence and job satisfaction, also impacting organizational teams. Workplace friendship functions as a social environmental support mechanism [61,62], comprising friendship prevalence and opportunity [31]. Positive coworker relationships foster productivity and emotional commitment to organizational goals [31]. This emotional dependence enhances cohesion and aims to improve organizational performance, with workplace friendship augmenting employee engagement and performance [63]. Ref. [64] found that workplace friendship indirectly affects employees’ work behavior; it positively correlates with self-efficacy [65]. Thus, workplace friendship facilitates interaction and social support, enhancing positive emotions and job satisfaction. In the international tourist hotel industry, workplace friendship significantly affects job satisfaction. Industry experts note that camaraderie and tacit understanding among colleagues substantially improve job satisfaction. Friendly relationships foster trust and warmth, facilitating coordination and communication. Friendships between colleagues and supervisors naturally build emotional commitment, providing support during challenges, creating a low-stress environment, and enhancing job satisfaction. Therefore, cultivating a positive work atmosphere and team cohesion contributes to overall job satisfaction [56]. Accordingly, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 2:

Workplace friendship in international tourist hotels positively influences employees’ job satisfaction.

2.7. Organizational-Level Factors (Green Organizational Climate) Affecting Job Satisfaction and Workplace Friendship in Hotels

Ref. [6] posits that leadership style, structure, and consideration dimensions of green organizational climate extend to the development of managerial workplace friendship, facilitating the diffusion of a green atmosphere within organizations. Irrespective of leadership style, organizations should encourage managers to cultivate friendships with subordinates beyond formal work relationships, as workplace friendship is voluntary, whereas work relationships are organizationally assigned [66,67]. Emotional dependence fosters cohesion and aims to enhance organizational performance. Thus, organizations should promote leadership styles characterized by high structure and consideration, as fostering workplace friendship influences employee engagement and performance, demonstrating supervisors’ concern for both production and employees’ psychological and emotional well-being, thereby nurturing harmonious relationships and organizational development toward shared goals [63]. Ref. [68] argue that meaningful understanding of workplace phenomena necessitates multilevel approaches. To comprehend job satisfaction, theory and research must consider individual and organizational-level influences. Historically, few studies have incorporated organizational factors into emotional labor research, such as job dissatisfaction [69,70]. Ref. [71] define organizational climate as individuals’ subjective awareness and cognition formed through values, needs, and personality regarding organizational structure, rules, policies, and leadership style, which affect peer workplace friendship, morale, behavior, and job satisfaction in achieving organizational goals. Ref. [72] contended that job satisfaction depends on the ratio of rewards to work input relative to others; greater equity leads to higher perceived fairness and satisfaction [73]. Ref. [74], adopting a cross-level perspective on impression management motivation and supervisor-oriented organizational citizenship behavior, found that organizational climate directly influences job satisfaction related to organizational citizenship behavior. Ref. [71] noted that organizational climate affects members’ cognition, psychological state, and behavior, significantly impacting employee engagement and self-directed learning. Ref. [75] observed that positive organizational climate during ERP system implementation correlates with higher job satisfaction; employees’ perceptions of the organization influence job satisfaction in the hotel industry. Ref. [6] conceptualized green economic, social, digital, and bureaucratic atmospheres, integrating variables pertinent to green organizational climate in organizational behavior research. Accordingly, the following hypothesis is proposed: Hypothesis 3: Green organizational climate in international tourist hotels directly influences employees’ job satisfaction.

Ref. [74] also found that organizational climate directly affects peer workplace friendship related to organizational citizenship behavior, linking deep-level workplace friendship to positive job satisfaction display rules. Studies confirm that organizational factors significantly influence both deep and surface workplace friendship behaviors [69,76,77]. Ref. [78] integrated organizational unit, peer, and individual-level display rules, verifying that shared beliefs about organizational climate span multiple levels. Thus, organizational environmental factors influence job satisfaction processes [11]. Ref. [6] identified green organizational climate factors encompassing economic, social, digital, and administrative dimensions. The green economic atmosphere pertains to economically motivated green practices; the green social atmosphere involves socially motivated green practices; the green digital atmosphere relates to environmentally beneficial digital practices; and the green bureaucratic atmosphere concerns environmentally supportive bureaucratic processes. These processes affect workplace friendship. Therefore, the following hypothesis is advanced: Hypothesis 4: Green organizational climate in international tourist hotels directly influences peer workplace friendship.

In summary, this study posits:

Hypothesis 3:

Green organizational climate in international tourist hotels directly influences employees’ job satisfaction.

Hypothesis 4:

Green organizational climate in international tourist hotels directly influences peer workplace friendship.

2.8. Contextual Moderating Effects of Peer-Level (Workplace Friendship) and Organizational-Level (Green Organizational Climate) Factors in Hotels

Ref. [79] posit that organizations within the hotel sector should prioritize fostering employee positivity. Utilizing Affective Events Theory, with particular emphasis on organizational support, these organizations can mitigate employees’ emotional exhaustion (EE) resulting from exploitative leadership (EL), thereby facilitating the development of positive work attitudes. Allocating resources toward this domain has the potential to augment employee engagement and enhance overall organizational performance. Furthermore, workplace friendships serve as a moderating variable in the relationship between employees’ behavioral quotient (BQ) and their job satisfaction. Ref. [65] defines workplace friendship as individuals’ perceptions of interpersonal friendliness within the organization, characterized by mutual commitment, trust, and shared work–life values, providing social support. Workplace friendship encompasses coworker interpersonal relationships [80], facilitating information sharing [81] and private emotional interactions. Ref. [66] describe workplace friendship as coworker relationships wherein employees offer emotional support and internal feedback, enhancing information sharing and promotion opportunities, existing among peers and between supervisors and subordinates. Ref. [31] emphasize three aspects of workplace friendship and organizational connectivity: (1) positive correlations with individual and organizational work outcomes; (2) contributions to informal organizational structures; and (3) increased organizational use of teams. Ref. [82] propose that transformational leadership transmits values, emotions, and attitudes through workplace friendship, influencing employee BQ, psychological capital, work engagement, and satisfaction; peer workplace friendship moderates the relationship between employee BQ and job satisfaction via service climate. Accordingly, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 5:

Workplace friendship in international tourist hotels moderates the relationship between employee BQ and job satisfaction.

Regarding workplace friendship and organizational climate, ref. [83] identified a significant positive relationship between organizational climate interaction fairness and workplace friendship. Ref. [84] argue that perceived organizational support fosters employee reciprocity beliefs, enhancing organizational performance, BQ, job satisfaction, and commitment. When employee BQ influences job satisfaction and job security is high, the willingness to maintain workplace friendships increases. Ref. [85] found that workplace friendship partially positively affects organizational citizenship behavior, with organizational justice moderating this relationship. Low perceived procedural justice diminishes the positive effect of friendship opportunity on the relationship between employee BQ and job satisfaction; thus, green organizational climate moderates the relationship between employee BQ and job satisfaction. Ref. [4] examined the direct effect of green organizational climate on organizational citizenship behavior in international tourist hotels and its moderating effect on the relationship between personal factors and organizational citizenship behavior. Ref. [86] found that personal green values moderate and enhance the relationship between affective commitment and hotel environmental performance. Ref. [87] studied the positive moderating effect of perceived green organizational support on the relationship between transformational environmental leadership and organizational citizenship behavior in international tourist hotels. Ref. [88] investigated the moderating role of green psychological climate (GPC) in international tourist hotels, finding a positive moderating effect on the relationship between green human resource management and ecological innovation. Ref. [89] reported that environmental sensitivity moderates the effect of green psychological climate on environmentally friendly behavior in international tourist hotels. Ref. [90] examined the association between environmental management practices in international tourist hotels and sustainable hotel performance, emphasizing the mediating role of employees’ pro-environmental behavior and environmental strategies. Their study was grounded in the Job Demands-Resources (JD-R) model and the Conservation of Resources (COR) theory. Additionally, they explored the moderating influence of environmental strategy (ES) on the linkage between hotel environmental management practices and employees’ pro-environmental behavior. Accordingly, this study posits that green organizational climate moderates the relationship between employee BQ and job satisfaction, contributing to environmental sustainability goals. Thus, the following hypothesis is advanced:

Hypothesis 6:

Green organizational climate in international tourist hotels moderates the relationship between employee BQ and job satisfaction.

Ref. [4] employed a multilevel approach to explore the direct effect of employee participation in organizational pro-environmental actions on green organizational citizenship behavior and the moderating effects of green organizational climate on the relationships between individual environmental values, collective emotions, organizational actions, and green organizational citizenship behavior. Ref. [87] contend that successful innovation in international tourist hotels requires cultivating a culture conducive to innovation and adaptability. Transformational leaders inspire motivation, intellectual stimulation, and autonomy, driving internal innovation. Ref. [91] assert that organizational culture, akin to organizational climate, exerts a long-term positive moderating effect on green human resource management practices, moderating green training and organizational citizenship environmental behavior, as well as green rewards and such behavior. Ref. [92] found no significant relationship between green organizational climate and employee creativity; a highly supportive, fair, and stable green organizational climate may lead to employee satisfaction with the status quo and reduced innovation motivation. Dissatisfied employees may seek novel approaches, such as enhancing BQ, to alter their circumstances [93,94,95,96]. Organizational communication mechanisms play a vital role in fostering employee capability development. Organizations should establish informal communication channels and actively organize cross-departmental gatherings to enhance mutual understanding and friendship between supervisors and employees, solicit employee feedback, and promote effective communication. Diverse communication channels improve member understanding, recognition of interaction fairness, and BQ, thereby increasing job satisfaction [18]. Job characteristics impose differentiated capability requirements across positions. Job variety and BQ both emphasize the utilization of multiple skills to complete work. For front-of-house employees in international tourist hotels, who represent the company’s image and interact directly with customers, creativity in both beauty and execution (brain and behavior) dimensions is essential [19,97]. Conversely, back-of-house employees typically engage in standardized service quality and products, requiring less development and customer interaction; while stimulating beauty and execution remains important, creativity demands are comparatively lower. Thus, green organizational climate moderates the relationships among workplace friendship, employee BQ, and job satisfaction. Accordingly, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 7:

Green organizational climate in international tourist hotels moderates the relationships among workplace friendship, employee BQ, and job satisfaction.

3. Mixed Methods Design

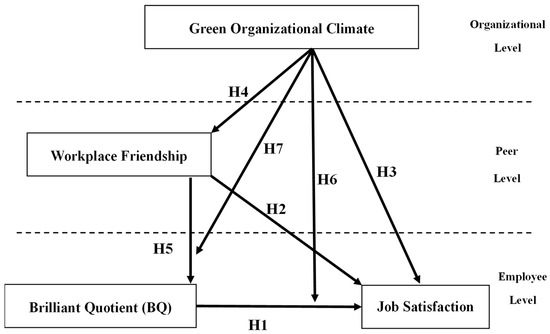

Drawing upon the research motivation, objectives, and an extensive review of the pertinent literature, a three-level hierarchical linear model was employed for data analysis. The conceptual framework and hypothesis testing are depicted in Figure 1. Specifically, the analysis was structured as follows:

Figure 1.

Diagram Illustrating the Research Analysis.

- -

- Organizational Level: Examination of the cross-level direct and moderating effects of the green organizational climate within international tourist hotels.

- -

- Peer Level: Investigation of the cross-level direct and moderating effects of workplace friendship among employees in international tourist hotels.

- -

- Employee Level: Assessment of the influence of employees’ Brilliant Quotient (BQ) on job satisfaction within international tourist hotels.

In alignment with the research objectives and literature synthesis, the following hypotheses were formulated:

- -

- Hypothesis 1 (H1): Employees’ Brilliant Quotient in international tourist hotels positively influences job satisfaction.

- -

- Hypothesis 2 (H2:) Workplace friendship in international tourist hotels positively influences employees’ job satisfaction.

- -

- Hypothesis 3 (H3): Green organizational climate in international tourist hotels directly influences employees’ job satisfaction.

- -

- Hypothesis 4 (H4): Green organizational climate in international tourist hotels directly influences peer workplace friendship.

- -

- Hypothesis 5 (H5): Workplace friendship in international tourist hotels moderates the relationship between employee BQ and job satisfaction.

- -

- Hypothesis 6 (H6): Green organizational climate in international tourist hotels moderates the relationship between employee BQ and job satisfaction.

- -

- Hypothesis 7 (H7): Green organizational climate in international tourist hotels moderates the relationships among workplace friendship, employee BQ, and job satisfaction.

3.1. Modified Delphi Technique

In the process of refining the Delphi technique, an initial series of three rounds of expert consultations was undertaken to develop the evaluation framework. This framework encompassed the procedural aspects, questionnaire design, and the criteria for achieving consensus among expert opinions. The primary objective was to conceptualize the “green organization” as the fundamental core of corporate culture and governance logic. Beyond its foundation in conventional organizational climate theory, the evaluation system was expanded to incorporate environmental considerations, including organizational values, the promotion of employees’ environmental awareness, and the integration of systematic decision-making processes.

3.1.1. Expert Panel Composition

Expert Group Composition: Includes tourism scholars (including professors specializing in hotel management, tourism communication, and sports tourism) (n = 4), public relations directors in the tourism industry (including international tourist hotels, comprehensive travel agencies, and leisure resorts) (n = 3), and tourism communication practitioners (n = 3), totaling 10 individuals, all with over 10 years of experience in their respective fields.

3.1.2. Process Design

- (1)

- Round One: Utilized open-ended questionnaires, which were subsequently synthesized into 38 value proposition indicators.

- (2)

- Round Two: Employed Likert scale scoring and the Content Validity Index (CVI) to confirm content validity. The CVI was calculated at 0.86, surpassing the established threshold. Indicators with importance ratings equal to or exceeding 4.0 on a six-point scale were retained.

- (3)

- Round Three: Conducted a consensus meeting to finalize indicators exhibiting a quartile deviation ≤ 0.5 and a coefficient of variation (CV) below 25%, thereby confirming the final dimensions and indicators.

Scale Development Outcomes:

- (1)

- The Green Organizational Climate Scale converged into six dimensions and six key indicators, comprising a total of 27 items.

- (2)

- The Workplace Friendship Scale was consolidated into two dimensions and two key indicators, encompassing 12 items.

- (3)

- The Brilliant Quotient (BQ) Scale was refined into two dimensions and two key indicators, including 30 items.

- (4)

- The Job Satisfaction Scale was distilled into three dimensions and three key indicators, containing 15 items.

3.1.3. Consensus Criteria

To ensure reliability and validity, subsequent analyses incorporated Cronbach’s alpha, the coefficient of variation (CV) of group responses, and Kendall’s W coefficient of concordance. The final Green Organizational Climate Scale at the organizational level demonstrated six dimensions with Cronbach’s alpha values detailed in Table 1. The CV (0.28) was within the acceptable limit (≤0.3), and Kendall’s W (0.83) exceeded the minimum threshold (≥0.7), thereby satisfying the Modified Delphi Technique’s consensus standards.

Table 1.

Key Indicators and α Values of Each Main Dimension in Green Organizational Climate.

Similarly, the Workplace Friendship Scale at the peer level included two dimensions with Cronbach’s alpha values presented in Table 2; the CV (0.27) and Kendall’s W (0.78) met the established criteria. The Brilliant Quotient (BQ) Scale, comprising two dimensions, exhibited Cronbach’s alpha values as shown in Table 3, with CV (0.25) and Kendall’s W (0.79) conforming to the consensus requirements. Lastly, the Job Satisfaction Scale, encompassing three dimensions, reported Cronbach’s alpha values in Table 4; the CV (0.28) and Kendall’s W (0.80) also fulfilled the consensus benchmarks of the Modified Delphi Technique.

Table 2.

Key Indicators and α Values of Each Main Dimension in Workplace Friendship.

Table 3.

Key Indicators and α Values of Each Main Dimension in Brilliant Quotient (BQ).

Table 4.

Key Indicators and α Values of Each Main Dimension in Job Satisfaction.

3.2. Research Samples and Sampling Design

3.2.1. Pilot Questionnaire Sampling

Following the initial development of the measurement scale, content validity was first assessed through a Delphi revision process involving ten academic experts. Incorporating their feedback, a pilot questionnaire was subsequently formulated. Item analysis and exploratory factor analysis were conducted to evaluate the scale’s reliability, validity, discriminative capacity, and internal consistency across dimensions, thereby ensuring its appropriateness for formal administration. Upon completion of the formal survey and data collection, confirmatory factor analysis was performed to reaffirm the scale’s reliability and validity [98,99]. Utilizing data from the Tourism Bureau’s Accommodation Network on international tourist hotels, the study encompassed 22 counties and cities throughout Taiwan. Regional classification was based on urban and regional development statistics from the National Development Council [100], dividing the 22 administrative areas into four groups: Northern, Central, Southern, and Eastern and Offshore Islands. The Northern region comprised Taipei City, New Taipei City, Keelung City, Hsinchu City, Taoyuan City, Hsinchu County, and Yilan County; the Central region included Taichung City, Miaoli County, Changhua County, Nantou County, and Yunlin County; the Southern region encompassed Kaohsiung City, Chiayi City, Tainan City, Chiayi County, and Pingtung County; and the Eastern and Offshore Islands region consisted of Taitung County, Hualien County, Kinmen County, and Lienchiang County. The target population comprised employees of international tourist hotels in Taiwan. For the pilot test, purposive sampling was employed. After securing consent from hotel management and supervisors, questionnaires were distributed to ten international tourist hotels located in Taipei City and Taichung City to facilitate item analysis and exploratory factor analysis of the preliminary scale. A total of 120 supervisor questionnaires and 350 employee questionnaires were disseminated. Following data collection and exclusion of invalid responses, 91 valid supervisor questionnaires (response rate: 75.8%) and 271 valid employee questionnaires (response rate: 77.4%) were retained.

3.2.2. Formal Questionnaire Distribution

The formal survey targeted all international tourist hotels across Taiwan, employing stratified proportional sampling. Based on the number of hotels and rooms reported by the [101], the population was stratified into four regions (North, Central, South, East), with proportional sampling of international tourist hotels within each region. Using weighted sampling to select international tourist hotels, including hotel heterogeneity (category, size, chain affiliation, and independent status).

After obtaining consent from hotel management and supervisors, 79 international tourist hotels were selected. Within each hotel, ten supervisors and ten employees from each supervisor’s department were surveyed. A total of 900 supervisor questionnaires and 9000 employee questionnaires were distributed. Following follow-up procedures, 68 hotels returned completed questionnaires. After excluding invalid responses, 623 valid supervisor questionnaires and 6230 valid employee questionnaires were obtained, yielding an effective response rate of 69.2% for both groups.

3.3. Development of Research Instruments and Data Processing

3.3.1. Green Organizational Climate Scale

Given the well-established conceptualization of green organizational climate, this study adopted an existing scale with demonstrated reliability and validity to measure the construct. Green organizational climate is conceptualized herein as an organizational environment that shapes members’ cognition, influencing both psychological states and behaviors, and significantly affecting employees’ work engagement and self-directed learning. The comparison between employees’ expectations and perceptions within international tourist hotels indicates that, beyond attending to employee voices, organizations also address diverse employee needs to foster exceptional employee value. Drawing upon organizational climate scales by [44,75] and as well as green organizational climate scales developed by [6,8,9], six principal dimensions were adapted for application in the hotel industry. Following expert review and revision via the Delphi method and exploratory factor analysis, 30 measurement items were finalized. Confirmatory factor analysis conducted using LISREL identified six dimensions with factor loadings ranging from 0.76 to 0.89, collectively explaining 76.15% of the variance. The fit indices are as follows: χ2/df = 3.597, GFI = 0.97, NNFI = 0.92, CFI = 0.94, TLI = 0.93, RMSEA = 0.076, and SRMR = 0.055. The composite reliability (CR) value is 0.935. The square roots of the average variance extracted (AVE) for the latent variables range from 0.753 to 0.907, while the correlations between latent variables range from 0.322 to 0.664. According to the Fornell-Larcker criterion, the square roots of the AVE are all greater than the correlations with other constructs, indicating that convergent validity is satisfied and discriminant validity is established. Additionally, the HTMT value is 0.72; since HTMT is less than 0.85, the model demonstrates excellent discriminant validity; Cronbach’s alpha coefficients ranged from 0.796 to 0.873, indicating satisfactory model fit and robust reliability and validity.

3.3.2. Workplace Friendship Scale

Given the mature development of the workplace friendship construct, an existing scale with established reliability and validity was employed. Workplace friendship is defined as the process by which employees in international tourist hotels transfer friendship opportunities from their personal lives into the workplace, fostering mutual understanding and collaboration that facilitate organizational goal attainment. The study utilized the two-dimensional workplace friendship scale developed by [31], encompassing the dimensions of friendship opportunity and friendship prevalence, previously applied in the hotel industry [83]. After expert review and Delphi method revision, followed by exploratory factor analysis, 12 measurement items were finalized. Confirmatory factor analysis via LISREL revealed two dimensions with factor loadings between 0.71 and 0.86, explaining 75.15% of the variance. The fit indices were χ2/df = 4.681, GFI = 0.96, NNFI = 0.97, CFI = 0.95, TLI = 0.92, RMSEA = 0.061, and SRMR = 0.035. The composite reliability (CR) value was 0.961. The square roots of the average variance extracted (AVE) for the latent variables ranged from 0.724 to 0.823, while the correlations between latent variables ranged from 0.411 to 0.529. According to the Fornell-Larcker criterion, the square roots of the AVE were all greater than the correlations with other constructs, indicating that convergent validity was satisfied and discriminant validity was established. Additionally, the HTMT value was 0.63, which is below the 0.85 threshold, further confirming excellent discriminant validity for the model; Cronbach’s alpha values ranged from 0.816 to 0.882, confirming good reliability and validity.

3.3.3. Brilliant Quotient Scale

The Brilliant Quotient (BQ) construct in this study is based on the framework proposed by the U.S.-based Coleman Management Consultant (CMC), which posits that workplace success depends on professionalism, image, and visibility. These elements collectively constitute the BQ [18,37,38,56]. BQ is defined as the integration and effective demonstration of employees’ professional image and competencies (both implicit and explicit) within relevant work contexts in the travel industry. The BQ construct comprises self-awareness, self-management, friendship opportunity management, and social awareness, organized into two primary components: beauty and execution, with execution further divided into cognitive and behavioral capacities. This scale was adapted for the hotel industry [18]. Following expert review, Delphi revision, and exploratory factor analysis, 30 measurement items were finalized. Confirmatory factor analysis using LISREL yielded factor loadings ranging from 0.72 to 0.89, explaining 79.64% of the variance. The fit indices are χ2/df = 6.243, GFI = 0.91, NNFI = 0.92, CFI = 0.92, TLI = 0.94, RMSEA = 0.078, and SRMR = 0.058. The composite reliability (CR) value is 0.948. The square roots of the AVE for the latent variables range from 0.699 to 0.895, while the correlations between latent variables range from 0.410 to 0.673. According to the Fornell-Larcker criterion, the square roots of the AVE are all greater than the correlations with other constructs, indicating that convergent validity is satisfied and discriminant validity is established. Additionally, the HTMT value is 0.69, which is below the 0.85 threshold, further confirming excellent discriminant validity of the model; Cronbach’s alpha coefficients ranged from 0.786 to 0.864, indicating satisfactory reliability and validity.

3.3.4. Job Satisfaction Scale

After reviewing extant literature on job satisfaction, a well-established and reliable scale tailored to the hotel industry was adopted. Within the context of international tourist hotels, job satisfaction is defined as an individual’s positive emotional state resulting from the appraisal of their job or work experience. Satisfaction is contingent upon the balance between rewards received and effort expended, as well as comparative evaluations of others’ work rewards and efforts; greater perceived equity corresponds to higher satisfaction. The study referenced [102] job satisfaction theory and utilized scales developed by [103,104], which focus on internal service quality evaluation in international tourist hotels and have been applied in the hotel industry [43]. Following expert review, Delphi revision, and exploratory factor analysis, 15 measurement items were finalized. Confirmatory factor analysis via LISREL identified three dimensions with factor loadings ranging from 0.72 to 0.91, cumulatively explaining 80.13% of the variance. The fit indices were GFI = 0.92, NNFI = 0.91, CFI = 0.92, RMSEA = 0.051, and SRMR = 0.051. The composite reliability (CR) value was 0.929. The square roots of the AVE for the latent variables ranged from 0.738 to 0.891, while the correlations between latent variables ranged from 0.369 to 0.534. According to the Fornell-Larcker criterion, the square roots of the AVE were all greater than the correlations with other constructs, indicating that convergent validity was satisfied and discriminant validity was established. Additionally, the HTMT value was 0.76, and since HTMT < 0.85, the model demonstrated excellent discriminant validity; Cronbach’s alpha values ranged from 0.838 to 0.879, demonstrating strong reliability and validity.

To address potential common method variance (CMV), Harman’s single-factor test was conducted to assess CMV among the research variables [105]. The analysis revealed that the first principal component accounted for less than 50% of the variance in each scale, indicating the absence of significant common method bias.

Statistical analyses were performed using hierarchical linear modeling (HLM), a method that simultaneously accounts for variables at multiple levels. Unlike traditional approaches that aggregate variables into a single multiple regression model, HLM independently analyzes variables at distinct levels [99]. Following Hofmann’s (1977) [106] guidelines and considering the study’s hypotheses involving level-1 direct effects, level-2 contextual direct effects, and level-2 contextual moderating effects, the conditions for hypothesis testing within the cross-level analysis model are presented in Table 5 [99].

Table 5.

Hypothesis Models and Verification Conditions for Level 1 and Level 2 in This Study.

Furthermore, this study aims to investigate a three-level framework addressing the cross-level effects of green organizational climate within international tourist hotels. To ascertain the presence of discriminant and convergent validity among the variables, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was employed to evaluate whether the measured dimensions satisfy the criteria for these validity types [98,107]. Four competing models were compared and validated: a single-factor model, wherein all three variables load onto a single latent construct; a three-factor model, Brilliant Quotient (BQ), workplace friendship, and green organizational climate; and a ten-factor model, encompassing beauty, execution ability, friendship opportunities, friendship prevalence, responsibility goals, interpersonal relationships, risk, openness, rewards, and decision-making structure.

Model fit indices, including the Goodness-of-Fit Index (GFI = 0.94), Adjusted Goodness-of-Fit Index (AGFI = 0.93), Incremental Fit Index (IFI = 0.95), Normed Fit Index (NFI = 0.93), and Relative Fit Index (RFI = 0.91), collectively indicated that the ten-factor model provided the superior fit. Within this model, all factor loadings were statistically significant at the 0.05 level, ranging from 0.71 to 0.89, thereby adhering to the recommended thresholds that factor loadings should neither exceed 0.95 nor fall below 0.50. Correspondingly, individual indicator reliabilities surpassed the 0.45 criterion, ranging from 0.796 to 0.882, which is indicative of robust convergent validity.

To assess discriminant validity, the study utilized the chi-square difference test alongside the confidence interval method as proposed by [108] and further applied by [98]. The analyses revealed that all 72 chi-square difference values were significant, and none of the 72 confidence intervals encompassed the value of 1, thereby confirming the discriminant validity of the ten-factor model [109].

Regarding data aggregation, the green organizational climate data were collected from supervisors within international tourist hotels. Prior to conducting cross-level analyses, it was imperative to evaluate the suitability of aggregating individual-level data to the group level, thereby enabling the representation of group characteristics (e.g., team or departmental data). This study employed the intraclass correlation coefficient 1 (ICC1) and the between-group consensus measure eta squared (η2) to assess within-group agreement and between-group variance. In practical research, an rwg value typically ranging from 0.90 to 0.96 indicates excellent group consensus. [98,99,107,110,111]. The ICC1 for supervisors’ evaluations of green organizational climate was 0.35, ICC2 was 0.85, ICC1 > 0.05, ICC2 > 0.80, rwg = 0.93 and η2 was 0.33 (F = 7.68, p < 0.001). Given that ICC1 exceeded the threshold of 0.05, these results support the appropriateness of aggregating the data for subsequent group-level analyses [112].

4. Research Findings

This study utilized a questionnaire survey methodology to investigate a three-tiered framework and the prevailing conditions concerning the cross-level effects of green organizational climate within international tourist hotels. The primary objective was to examine how factors at the organizational level (green organizational climate), peer level (workplace friendship), and individual employee level (Brilliant Quotient (BQ)) collectively impact job satisfaction in this context. Guided by the established research framework and hypotheses, the valid sample data collected were subjected to rigorous statistical analyses, the outcomes of which were subsequently interpreted and discussed.

4.1. Model and Hypothesis Evaluation: Null Model (Model 1)

In conducting cross-level analysis, it is imperative first to verify the presence of cross-level effects, fulfilling the criteria outlined as Condition 1 (refer to Table 5). This necessitates decomposing the variance of the dependent variable into within-group variance and between-group variance components, denoted as within-group variance (δ2) and between-group variance (τ00), respectively. Crucially, the between-group variance component must demonstrate statistical significance, differing from zero. The analytical model employed for this purpose is consistent with prior studies [11,99,113].

Level 1: Job Satisfaction ijk = β0jk + rijk

Level 2: β0jk = β00k + U0jk

Level 3: β00k = r000 + U00k

Drawing upon the aforementioned model, the present study identified that the variance components attributable to peer groups (χ2 = 668.47, df = 202, p < 0.001) and organizational groups (χ2 = 328.41, df = 30, p < 0.001) were both significantly greater than zero, whereas the within-group variance component was estimated at 154.61. Integrating these findings, it is evident that 10.25% of the variance in employees’ job satisfaction is accounted for by differences between peer groups, while 29.14% is explained by differences between organizational groups; both proportions reached statistical significance. These results suggest that the dependent variable exhibits meaningful variance at both within-group and between-group levels. Additionally, reliability estimates were calculated as 0.80 at the peer group level and 0.89 at the organizational level. In the model, −2LL = 21 indicates a significant improvement in the model. Additionally, when AIC and BIC point to different models, AIC tends to select models with stronger predictive power but higher complexity, while BIC tends to favor more parsimonious models. In this study, both AIC = 1.8 and BIC = 1.1 are less than 2, indicating that the models have equivalent advantages. In the model, p < 0.05 and Δχ2 = 13 (usually >10) indicate that the model is statistically valid. Collectively, these data substantiate the suitability of employing a three-level Hierarchical Linear Modeling (HLM) framework to analyze employees’ job satisfaction [109].

4.2. Model and Hypothesis Testing: Random Parameter Regression Model (Model 2)

Subsequent to establishing the presence of variance components at multiple levels, the study proceeded to assess model fit under Conditions 2 and 3, specifically evaluating whether intercepts and slopes differ significantly across groups. This step entails testing Hypothesis 2 (H2), which posits that intercepts vary meaningfully between groups. Moreover, the model facilitates direct examination of the relationship between level-1 independent variables and the dependent variable, as articulated in Hypothesis 1 (H1). By comparing variance components derived from this model with those from a null model, the influence of hierarchical levels on the dependent variable can be quantified [11,99,113].

Level 1: Job Satisfaction ijk = β0jk + β1jk (Charm) + β2jk (Execution Ability) + rijk

Level 2: β0jk = β00k + U0jk

β1kj = β10k + U1jk

β2jk = β20k

Level 3: β00k = r000 + U00k

β10k = r100

β20k = r200

Regarding the random parameter regression model, the model shows a −2LL = 23, indicating a significant improvement. Additionally, when AIC and BIC point to different models, AIC tends to select models with stronger predictive power but higher complexity, while BIC tends to favor more parsimonious models. In this study, AIC = 6.3 and BIC = 1.5, with a difference between 2 and 7, suggesting that the model with the lower value (the more parsimonious model) has a substantial advantage. In the model, p < 0.05 and Δχ2 = 15 (usually >10) indicate that the model is statistically valid. This model analyzes the predictive power of employees’ attractiveness and execution ability on their job satisfaction.

From Model 2 in Table 6, it can be seen that Level 1 attractiveness (γ100 = 0.38, se = 0.12, t = 2.35, df = 227, p = 0.024) reaches a significant level. In contrast, execution ability does not reach significance. This shows that Level 1 employees’ attractiveness has a significant positive effect on job satisfaction. However, it is worth noting that although execution ability does not have a significant impact on job satisfaction, the estimate γ200 = −0.19 in Table 6 is negative, indicating that the relationship between execution ability and job satisfaction is likely negative. In other words, execution ability may still weaken employees’ job satisfaction, so Hypothesis 1 (H1) is partially supported. Through explanations involving resource allocation, performance pressure, and misfit mechanisms, when there is a lack of clear rewards and participatory decision-making processes, employees with high execution ability may experience emotional exhaustion and lower satisfaction (demand-supply misfit).

Table 6.

Summary Table of the Three-Level Hierarchical Linear Model Analysis Concerning the Climate of Green Organizations in International Tourist Hotels.

Furthermore, Table 6 indicates the absence of a random effect for execution ability within the model employed in this study. Specifically, the random effect term for execution ability was non-significant (variance component = 1.31, χ2 = 231.34, p = 0.198). Consequently, a likelihood ratio test was performed to compare models incorporating and excluding this random effect. Model fit was assessed using the maximum likelihood (ML) estimation method to derive deviance values for each model [98,112]. The deviance for the model including the random effect was 20,141.81, whereas the deviance for the model excluding the random effect was 20,143.04. The difference in deviance (1.23) was not statistically significant (p > 0.05), supporting the decision to simplify the model. Accordingly, subsequent analyses treated the random effect of execution ability as nonexistent.

4.3. Cross-Level Analysis: Comprehensive Model Analysis of Workplace Friendship in International Tourism Hotels (Model 3)

Given that Hypothesis 1 (H1) was only partially supported, the present study proceeds to investigate whether the presence of the intercept can be accounted for by Level 2 variables, specifically human resource management factors such as friendship opportunities and friendship prevalence. This analysis aims to assess the validity of Hypotheses 2 (H2) and 5 (H5). The analytical model employed is as follows [11,98,107,113]:

The complete Level 2 model of this study is shown below:

Level 1: Job Satisfaction ijk = β0jk +β1jk (Charm) + β2jk (Execution Ability) + rijk

Level 2: β0jk = β00k + β01k (Opportunities for Friendship) + β02k (Prevalence of Friendship) + U0jk

β1jk = β10k + β11k (Opportunities for Friendship) + β12k (Prevalence of Friendship) + U1jk

β2jk = β20k + β21k (Opportunities for Friendship) + β22k (Prevalence of Friendship)

Level 3: β00k = r000 + U00k

β01k = r010

β02k = r020

β10k = r100

β11k = r110

β12k = r120

β20k = r200

β21k = r210

β22k = r220

In the model, −2LL = 26 indicates a significant improvement in the model. Additionally, with AIC = 7.5 and BIC = 1.8, the difference falls between 2 and 7, showing that the more parsimonious model with the lower BIC has a substantial advantage. In the model, p < 0.05 and Δχ2 = 19 (usually >10) indicate that the model is statistically valid.

The results from Model 3, as presented in Table 6, indicate that the direct effect of workplace friendship at Level 2 on employees’ job satisfaction is significant only for friendship opportunities (γ020 = 0.11, t = 2.45, p = 0.018). Consequently, Hypothesis 2 (H2) receives partial empirical support. It should be noted that the direct effect estimates were derived exclusively from the intercept-only prediction model; however, for the sake of clarity, these values are consolidated within the table, a convention that will be maintained throughout the subsequent analyses without further mention.

Regarding employees’ attractiveness, the interaction coefficient was statistically significant (γ120 = −1.65, t = −2.53, p = 0.035), suggesting that the positive association between attractiveness and job satisfaction is moderated by the generality of workplace friendships, with this moderation effect being negative. In other words, when supervisors place greater emphasis on the generality of friendships, the initially positive relationship between employees’ attractiveness and their job satisfaction tends to be attenuated.

Similarly, for employees’ execution ability, the interaction coefficient also reached significance (γ220 = 1.71, t = 2.57, p = 0.022), indicating that the negative relationship between execution ability and job satisfaction is moderated by friendship generality, with the moderation effect again being negative. This implies that supervisors’ emphasis on friendship generality likely diminishes the originally negative association between execution ability and job satisfaction. Accordingly, Hypothesis 5 (H5) is also only partially supported.

Furthermore, it is important to highlight that random effects at Level 3, aside from the intercept term, were not present in this model. This conclusion is based on the random effects analysis, which revealed that none of the terms other than the intercept achieved statistical significance. A likelihood ratio test comparing models with and without random effects, estimated via the maximum likelihood method [98,112], yielded deviance values of 21,358.42 and 21,352.89, respectively. The difference in deviance (5.53) was not statistically significant (p > 0.05). Additionally, reliability estimates at Level 3 ranged from 0.079 to 0.128, indicating relatively low reliability. These findings collectively justify the simplification of the model by excluding random effects at Level 3. Therefore, random effects at this level are deemed absent in the present study.

4.4. Cross-Level Analysis: Comprehensive Model Analysis of Green Organizational Climate in International Tourism Hotels (Model 4)

Given that Hypotheses 2 (H2) and 5 (H5) received only partial empirical support, the present study proceeds to investigate whether the direct effects observed in the intercept prediction model, as well as the moderating effects identified in the interaction terms of the slope prediction model, can be accounted for by Level 3 variables. These Level 3 variables pertain to human resource management (HRM) factors, specifically responsibility goals, interpersonal relationships, risk, openness, rewards, and decision-making structure. This analysis aims to assess the validity of Hypotheses 3 (H3), 4 (H4), 6 (H6), and 7 (H7). The analytical framework employed is based on the methodologies outlined by [11,98,107,113].

The complete Level 3 model of this study is presented below:

Level 1: Job Satisfaction ijk =β0jk + β1jk (Charm) +β2jk (Execution Ability) + rijk

Level 2: β0jk = β00k + β01k (Opportunities for Friendship) + β02k (Prevalence of Friendship) + U0jk

β1jk = β10k + β11k (Opportunities for Friendship) + β12k (Prevalence of Friendship) + U1jk

β2jk = β20k + β21k (Opportunities for Friendship) + β22k (Prevalence of Friendship)

Level 3: β00k = r000 + r001(Responsibility and Goals) + r002(Interpersonal Relations) + r003(Risk) + r004

(Openness) + r005(Rewards) + r006(Decision-Making Structure) + U00k

β01k = r010 + r011(Responsibility and Goals) + r012(Interpersonal Relations) + r013(Risk) + r014

(Openness) +r015(Rewards) + r016(Decision-Making Structure)

β02k = r020 + r021(Responsibility and Goals) + r022(Interpersonal Relations) + r023(Risk) + r024

(Openness) + r025(Rewards) + r026(Decision-Making Structure)

β10k = r100 + r101(Responsibility and Goals) + r102(Interpersonal Relations) + r103(Risk) + r104

(Openness) + r105(Rewards) + r106(Decision-Making Structure)

β11k = r110 + r111(Responsibility and Goals) + r112(Interpersonal Relations) + r113(Risk) + r114

(Openness) + r115(Rewards) + r116(Decision-Making Structure)

β12k = r120 + r121(Responsibility and Goals) + r122(Interpersonal Relations) + r123(Risk) + r124

(Openness) + r125(Rewards) + r126(Decision-Making Structure)

β20k = r200 + r201(Responsibility and Goals) + r202(Interpersonal Relations) + r203(Risk) + r204

(Openness) + r205(Rewards) + r206(Decision-Making Structure)

β21k = r210 + r211(Responsibility and Goals) + r212(Interpersonal Relations) + r213(Risk) + r214

(Openness) + r215(Rewards) + r216(Decision-Making Structure)

β22k = r220 + r221(Responsibility and Goals) + r222(Interpersonal Relations) + r223(Risk) + r224

(Openness) + r225(Rewards) + r226(Decision-Making Structure)

In the model, −2LL = 29 indicates a significant improvement in the model. Additionally, with AIC = 8.9 and BIC = 2.1, the difference falls between 2 and 7, showing that the more parsimonious model with the lower BIC has a substantial advantage. In the model, p < 0.05 and Δχ2 = 21 (usually >10) indicate that the model is statistically valid.

The green organizational climate at the third hierarchical level within international tourist hotels comprises six dimensions: responsibility goals, interpersonal relationships, risk tolerance, openness, rewards, and decision-making structure. The analysis presented herein proceeds in two stages. Initially, an intercept prediction model is employed to examine the direct effects of the green organizational climate on employees’ job satisfaction and peer-level workplace friendships. Subsequently, a slope prediction model is utilized to investigate the moderating influence of the green organizational climate on the interaction between employees’ job satisfaction and peer-level workplace friendships.