Abstract

As digital and intelligent technologies become increasingly intertwined. Digital and Intelligent Transformation (DIT) emerges as a key catalyst for advancing high-quality economic and social development. Against this backdrop, as the core entities in green and low-carbon transition, corporate green innovation (GI) capabilities have garnered increasing attention. To evaluate the effects of DIT on corporate GI, the study employs the establishment of the “National New Generation Artificial Intelligence Innovation and Development Pilot Zones” (NAIPZ) as a quasi-natural experimental. This paper analyzes the impact and transmission channels of DIT on GI, using panel data from Chinese A-share listed companies (2011–2022). Employing a multi-period DID approach, the results indicate that the policy promotes GI. Additionally, the findings are supported by extensive robustness checks. Heterogeneity analysis reveals that the policy impact is moderated by firm size, and industry characteristics. Mechanism analysis reveals that urban DIT promotes corporate GI by enhancing government governance capacity, accelerating corporate digital transformation, and optimizing human capital structures. Based on these findings, we recommend tailored policy frameworks, strengthened innovation infrastructure, increased R&D support, and effective performance-tracking mechanisms. These measures can help maximize the potential of artificial-intelligence technology in advancing corporate GI.

1. Introduction

In an era when digital technologies are deeply integrated into economic and social development, urban digital-intelligence transformation has emerged as a key driver of high-quality growth. The proliferation of next-generation information technologies, including artificial intelligence, big data, and the Internet of Things, in urban governance, industrial optimization, and public services is reshaping urban development paradigms while creating novel technological and institutional conditions for corporate innovation [1]. At the same time, China has clearly articulated its strategic goals of “carbon peak” and “carbon neutrality,” making green and low-carbon transition a central agenda for sustainable development [2]. As fundamental units of economic activity, firms play a pivotal role in this transition. Their capacity for GI not only affects the effectiveness of environmental governance but also directly influences the enhancement of national green competitiveness. Against the backdrop of the dual transformation of digital progress and ecological sustainability, how the digital and intelligent upgrade of cities can stimulate enterprise innovation, especially green-technology innovation, has become a key issue at the intersection of policy and academic research.

In recent years, the Chinese government has advanced the construction of “new-type smart cities” and launched the “National New Generation Artificial Intelligence Innovation and Development Pilot Zones” starting in 2019, aiming to promote the deep integration of AI technologies with urban governance and industrial development. This policy initiative provides a valuable quasi-natural experimental setting for identifying the economic effects of urban DIT. Theoretically, such transformation can foster corporate GI through multiple pathways [3]. First, intelligent regulatory systems can enhance the precision and deterrence of environmental enforcement, strengthening firms’ incentives for compliance. Second, the efficient circulation of data as a production factor improves resource allocation and reduces information barriers and coordination costs in green technology R&D. Furthermore, the development of city digital infrastructure facilitates knowledge spillovers and technological diffusion, accelerating the adoption of GIs [4].

This research has made certain contributions to the study related to GI. Firstly, it breaks through the limitation of existing research that mostly focuses on the micro level of enterprises and neglects the key connecting role of cities [5]. It innovatively approaches from the perspective of urban governance, expands the research dimension to the urban level, systematically explores the role of urban DIT on the GI of enterprises, and builds an “intermediate transmission layer” between macro-policies and micro-enterprise behaviors. Secondly, it breaks the narrow technical understanding of digital-intelligent transformation, redefines the concept of urban DIT, extends it to a systematic framework covering governance models, resource allocation and the reconstruction of the innovation ecosystem, and constructs a more comprehensive analytical paradigm. Thirdly, unlike the existing research that focuses on the isolated impact of policies on individual enterprises and the direct technological effects of digitalization within enterprises, this paper clarifies that the DIT of cities is achieved through regulatory monitoring, macro resource allocation, technological cooperation among enterprises, and knowledge spillover; Fourth, incorporating cities and enterprises into a unified analytical framework supplements macro, indirect and systematic research perspectives, reveals the key value of smart cities in coordinating resources and fostering an innovative atmosphere, improves the evaluation system for the effects of relevant policies, and provides more targeted theoretical support for the formulation of regional GI policies.

Therefore, the paper employs a DID framework to investigate how urban DIT influences corporate GI, using pilot cities designated under the NAIPZ. We further analyze how urban DIT promotes corporate GI by strengthening regulation, improving resource allocation efficiency, and facilitating technological spillovers. Additionally, analysis of heterogeneity highlights that the effect of urban DIT differs significantly among firms based on their size, and industrial classification. Further investigation shows that urban DIT enhances corporate GI by optimizing government governance capacity, accelerating corporate digital transformation, and enhancing human capital structure. The objective of this study is to reveal the channels through which urban DIT drives corporate GI, thereby providing theoretical insights and policy implications for supporting GI within the urban DIT framework. The findings provide reference points for policymakers in formulating sustainable development strategies and guide enterprises in enhancing green-innovation capabilities, thereby facilitating societal green transition and supporting coordinated environmental–economic development in China and globally.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Corporate GI Research

Current research about corporate GI primarily focuses on external environmental factors and internal firm characteristics.

In terms of external environments, studies center around policy orientation and market-driven mechanisms. Regarding policy orientation, many scholars investigate the roles of environmental regulation and government fiscal and tax incentives. On the one hand, research indicates that under the global push toward eco-friendly development, environmental regulation has become a fundamental governance tool adopted by governments worldwide to facilitate low-carbon transitions in economies and societies [6]. Some studies find a U-shaped pattern in the relationship between environmental regulation and GI [7], while others identify an inverted U-shape [8]. On the other hand, regarding fiscal and tax incentive policies, many countries implement subsidies, rewards, and tax rebates under environmental constraints to promote GI [9]. The combination of government subsidies and tax incentives plays a complementary role in advancing corporate green technological innovation [10]. Green subsidies have been found to significantly enhance corporate GI [11]. Regarding market-driven mechanisms, market-driven studies mainly explore the influence of financial instruments, consumer behavior, and media monitoring on corporate GI. Studies show that green finance [12], green credit [13], green bonds, and green funds [14] all play a significant promoting role in GI. Consumer feedback exerts a considerable influence on firms’ GI efforts [15]. Media attention affects corporate GI primarily through its influence on corporate reputation; positive media coverage enhances green technological innovation outcomes [16].

Research on internal firm factors mainly centers around ESG performance, green resources, and digital transformation. First, the Environmental–Social–Governance (ESG) framework has been widely recognized across countries as a sustainability indicator for firms operating under green development models [17], contributing to improved investment allocation [18,19] and effectively promoting green-innovation activities [20]. Second, corporate green human resource management [21] and executives’ environmental awareness [22] are also conducive to GI. Third, digital transformation significantly boosts corporate GI [23], although it exhibits an inverted U-shaped relationship with GI in resource-based firms [24].

Although existing research on GI has generated substantial insights regarding external policies, market mechanisms, and firms’ internal factors, several limitations remain evident. On the one hand, studies on macro-level policy orientations, market-driven forces, and micro-level firm factors tend to be fragmented. The “intermediate transmission layer” connecting these dimensions has received limited attention, and there is a lack of in-depth analyses of policy effects that account for regional contexts. On the other hand, most existing studies focus predominantly on a single dimension, either at the national level or the firm level, while paying insufficient attention to the critical role of cities as both “carriers of policy implementation” and “spaces of enterprise agglomeration.” Consequently, the pivotal function of cities in integrating policy resources, optimizing market environments, and linking firms’ internal dynamics has often been overlooked. Exploring the drivers of corporate GI from the urban perspective is therefore of considerable significance. As specific arenas for the implementation of environmental regulations and the deployment of green finance, cities not only provide a more precise spatial framework for assessing the effects of policies and market mechanisms but also help bridge the gap between macro-level and micro-level research. By examining how urban characteristics such as digital infrastructure and industrial agglomeration shape corporate GI, such an approach can offer valuable insights for the formulation of more targeted and effective regional green-innovation policies.

2.2. Research on the Impact of DIT on GI

In recent years, scholars have examined the impact of artificial intelligence (AI) on corporate GI from a micro-level perspective, focusing on its application in firms. On the one hand, AI enhances production efficiency and technological capabilities, thereby stimulating firms’ green-innovation potential. Research indicates that the adoption of intelligent technologies improves process stability, reduces operational risks and costs, and increases resource efficiency, thus creating favorable conditions for green R&D [25]. The widespread use of industrial robots not only raises automation levels by replacing repetitive tasks but also significantly boosts GI output by optimizing human capital structure and improving internal governance mechanisms, AI substantially strengthens data processing capabilities in manufacturing, unlocking the productive potential of data as a new factor of production, and driving overall industrial transformation and upgrading—thereby facilitating green-technological innovation and structural optimization [26]. In this process, cost reduction, knowledge spillovers, and human capital enhancement have been identified as key mediating pathways [25]. On the other hand, studies suggest a potential nonlinear relationship between AI and GI, with the effect contingent on firms’ resource endowments and external environmental conditions [27]. International research further shows that firms with stronger capabilities in developing and integrating AI are more likely to achieve green product and process innovation [28].

Research on policies related to the DIT of cities mainly focuses on the city and enterprise levels, as shown in Table 1. The implementation of this policy can significantly enhance the energy-utilization efficiency of cities, promote the synergy of industrial digitalization and greening [29,30], and effectively reduce the carbon emissions of enterprises and improve ESG performance [31,32,33]. Regarding the discussion on this policy and the GI of enterprises, existing studies all hold that the implementation of the policy has enabled enterprises to enhance their operational efficiency, improve internal governance, optimize internal human capital, and increase productivity through the application of digital technology, thereby promoting the GI of enterprises [34,35,36]. Obviously, these studies only considered the isolated impact of policies on individual enterprises.

Table 1.

Research on Policies Related to Urban DIT.

Although the existing literature has enriched the theoretical understanding of the relationship between DIT and GI from the enterprise level, the related disputes have not yet been resolved. Moreover, most of the existing research focuses on the direct technical application of artificial intelligence within enterprises, and the attention paid to policies merely remains at the level where policies bring direct digital technologies to enterprises and thereby promote innovation. However, there is a clear lack of attention paid to how the DIT of systems at the city level affects the innovative behavior of enterprises. Focusing solely on digital transformation within enterprises has inherent limitations [37], and their internal resource management and optimization capabilities are limited. When enterprises take other goals into account, it is also difficult for them to maximize the benefits of GI [38]. In contrast, the DIT of cities can identify potential problems at the enterprise level through regulatory monitoring and provide support for problem-solving with the help of macro resource allocation. At the same time, it can also promote collaboration among enterprises and technology spillover, all of which are difficult for a single enterprise to achieve independently. From a more macroscopic perspective of systems and resource allocation, the DIT of cities can influence the GI of enterprises through enhancing government governance capacity, accelerating the digitalization process of enterprises, and optimizing human capital structure. However, its mechanism of action is essentially different from the internal adjustment of enterprises. This study holds that we should link cities with enterprises and systematically explore the impact of urban DIT on enterprise innovation. It supplements the existing field with a more macroscopic, indirect and systematic analytical dimension, which has significant theoretical and practical value.

This study is designed to address this critical research gap. By employing a multi-period difference-in-differences (DID) model, it extends the analytical scope of research on corporate GI. The main contributions are threefold. First, by leveraging the NAIPZ as a quasi-experimental setting, we integrate advanced AI policy evaluation with corporate GI within a unified framework, exploring how policy-enabled urban DIT promotes corporate GI. Employing a multi-period Difference-in-Differences framework supplemented by comprehensive robustness analyses, our findings are more precise and reliable. Second, this study offers empirical evidence on the heterogeneous effects of the pilot zones across different firm types, providing insights for policy design. Third, we present empirical evidence regarding the internal mechanisms through which the pilot zones promote corporate GI. Specifically, we empirically analyze the mediating roles of government governance capacity, corporate digital transformation, and human capital structure, thereby deepening our understanding of the pathways linking urban DIT and corporate GI. Our findings may offer both theoretical insights and policy-relevant implications for relevant authorities, aiming to refine the design of the NAIPZ and promote corporate GI.

3. Background and Hypotheses Development

3.1. Background

Against the backdrop of rapid advancements in artificial intelligence (AI) technology, its effects on economic and social aspects are becoming increasingly evident. In 2017, the State Council released the “New Generation Artificial Intelligence Development Plan,” which clearly set forth the development goals and prioritized the creation of experimental zones. In 2019, the Ministry of Science and Technology released the “Guidelines for the Construction of National New Generation Artificial Intelligence Innovation and Development Pilot Zones,” initiating pilot programs at the prefectural level. As of June 2025, seven batches of experimental zones have been established across 18 cities, exploring new pathways for AI industrialization, urban digital transformation, and government–enterprise collaboration. Each pilot zone leverages regional features to drive technological innovation and practical implementation, fostering the intelligent growth of cities and offering robust support for the high-quality advancement of China’s AI industry.

3.2. Hypotheses Development

3.2.1. The Policy Effect of the Impact of Urban DIT on Corporate GI

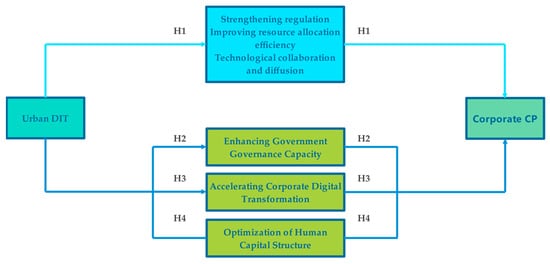

According to institutional theory, reasonable institutional arrangements play a guiding role in economic behavior [39]. The establishment of NAIPZ and Urban DIT essentially aim to regulate and guide the behavior of enterprises within the region by building a digital institutional and platform environment. Urban DIT markedly improves firms’ GI capabilities by deeply integrating emerging technologies like artificial intelligence. This transformation strengthens regulatory oversight over enterprises. AI-driven big data analytics, IoT-based monitoring systems, and intelligent recognition algorithms are increasingly integrated into government-led environmental governance frameworks, facilitating real-time surveillance and dynamic assessment of corporate energy usage, carbon emissions, and waste management practices. This smart regulatory approach improves the precision and transparency of policy implementation, prompting firms to proactively accelerate green technology upgrades under stricter compliance requirements in order to reduce environmental risks and enhance sustainability performance. Moreover, urban DIT optimizes resource allocation [40]. By deeply mining production, supply chain, and market data, AI helps enterprises identify areas of resource inefficiency and optimize energy usage structures, thereby improving the efficiency of green production. For example, intelligent manufacturing systems can predict equipment operating conditions and reduce unnecessary energy consumption; smart scheduling platforms facilitate the efficient allocation of green raw materials and low-carbon logistics resources, thus enhancing the economic viability of corporate GI. At the stage of technological development and diffusion, advancements in digital and intelligent platforms, together with open-source technology ecosystems, facilitate the rapid dissemination of green knowledge and technologies, thereby reducing the entry barriers for small and medium-sized enterprises to participate in GI [41]. Meanwhile, the advancement of industrial internet fosters cross-sector collaborative innovation, enabling manufacturers, environmental technology firms, and other stakeholders to jointly tackle challenges in energy conservation, emission reduction, and circular economy development. This has given rise to a more dynamic GI network. Therefore, we propose:

Hypothesis 1:

Urban DIT significantly promotes corporate GI.

3.2.2. Mediating Roles of Government Governance Capacity

Urban DIT promotes corporate GI by significantly enhancing government governance capacity. Grounded in institutional theory, which posits that formal rules and enforcement mechanisms shape economic behavior [39], urban DIT provides governments with advanced technological tools to refine their governance across multiple dimensions, creating an institutional environment that either incentivizes or compels firms to pursue sustainable innovation. This enhanced governance capacity acts as a critical mediator.

Specifically, urban DIT augments government capabilities in four interconnected areas. First, it improves R&D environment governance through data-driven policy design and resource allocation. Intelligent platforms enable precise identification of innovation gaps and dynamic matching of R&D subsidies or tax incentives, effectively lowering the cost and risk of green technology exploration for firms. Second, it strengthens business environment governance by streamlining administrative procedures via digital platforms and smart regulatory systems. This reduces institutional transaction costs and increases market predictability, freeing up corporate resources for long-term GI investments [42]. Third, it transforms ecological environment governance. IoT-based monitoring networks and AI analytics allow for real-time, precise oversight of corporate emissions and resource use. This smart regulation raises the cost of non-compliance, creating a potent “regulatory push,” while also enabling governments to offer targeted technical guidance, thus facilitating a “supportive pull” for green transition [43]. Finally, it contributes to legal environment construction by accelerating the formulation of digital economy regulations and green standards. A clearer and more transparent legal framework, enforced through digital means, reduces uncertainty for green investments and protects intellectual property, providing a stable foundation for innovation.

In essence, by systematically upgrading governance in these four domains, urban DIT shapes a composite institutional setting characterized by effective incentives, stringent constraints, and orderly services. This enhanced governance capacity not only directly supports GI through improved resource allocation and knowledge spillovers but also imposes normative and coercive pressures on firms to align their strategies with sustainability goals. Therefore, we propose:

Hypothesis 2:

Urban DIT promotes corporate GI by enhancing government governance capacity.

3.2.3. Mediating Roles of Corporate Digital Transformation

Urban DIT significantly enhances firms’ GI capabilities by promoting corporate digital transformation. Against the backdrop of continuously improving digital infrastructure and strengthening policy guidance at the city level, firms are increasingly able to adopt advanced technologies such as big data, artificial intelligence, and the Internet of Things. These technologies enable firms to restructure production processes and management systems, fostering the development of data-driven operational models. This transformation allows firms to monitor energy consumption and emissions in real time and implement precise control measures, thereby providing essential technological support for GI [44]. According to the Resource-Based View (RBV), the digital assets, intelligent systems, and data analytics capabilities accumulated through digital transformation constitute strategic resources that are difficult for competitors to imitate. These resources help firms identify viable technological pathways for energy conservation and emission reduction, while reducing the trial-and-error costs associated with green R&D. Furthermore, the Dynamic Capabilities Theory suggests that firms must possess the ability to sense environmental changes, integrate resources, and reconfigure internal processes to respond to complex challenges. The digital environment enhances firms’ responsiveness to policy signals and market demands, enabling them to swiftly identify opportunities in green technologies [45]. Through digital R&D platforms, firms can achieve cross-functional collaboration and accelerate the iteration of green products. At the same time, digital systems facilitate knowledge creation and sharing. Firms continuously refine their production processes based on data feedback, fostering organizational learning and strengthening the internal drivers of GI. Therefore, we propose:

Hypothesis 3:

Urban DIT promotes corporate GI by accelerating corporate digital transformation.

3.2.4. Mediating Roles of Human Capital Structure

Within the framework of establishing the NAIPZ, urban DIT not only provides enterprises with advanced technological support and a favorable policy environment, but also indirectly promotes their GI capabilities by optimizing human capital structure. According to the resource-based view, unique resources owned by firms are among the key factors in gaining competitive advantage. High-skilled labor, as an important internal strategic resource, plays an irreplaceable role in advancing technological innovation and sustainable development [46]. Urban DIT enhances the inflow of high-tech talents by improving the city’s intelligent infrastructure and digital ecosystem, while also facilitating the upgrading of existing local labor to higher skill levels. For example, in cities such as Hangzhou and Shenzhen, where the level of digitalization is relatively high, joint investments by governments and enterprises in AI laboratories and innovation centers have created platforms for attracting top global research talents. The agglomeration of such high-end talents has significantly enhanced the innovation capabilities of local enterprises. Furthermore, according to the knowledge-based theory, the creation, sharing, and application of knowledge constitute the core driving force for sustained corporate development [47]. By establishing open knowledge exchange platforms and intelligent learning systems, urban DIT facilitates effective knowledge dissemination within and across organizations, thereby enhancing employees’ learning capacity and innovative thinking. Therefore, we propose:

Hypothesis 4:

Urban DIT significantly enhances corporate GI through the optimization of human capital structure.

Based on the above theoretical discussions and hypotheses, Figure 1 constructs a conceptual framework.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework.

4. Research Design

4.1. Data Sources

This study uses A-share listed firms on the Shanghai and Shenzhen Stock Exchanges from 2011 to 2022 as the research sample. Firm-level data, including fundamental characteristics, control variables, human capital composition, are sourced from the CSMAR database. We exclude ST, *ST, PT firms and financial companies, and perform winsorization on the main variables. We match the firm-level data to the cities based on the location of the firms. After matching, the final sample contains 13,026 observations. Corporate GI is measured by green patent data from the CNRDS. City-level data come from the China City Statistical Yearbook and missing values are filled using interpolation. All regressions are estimated using Stata/MP 18.0.

4.2. Definitions of Variables

4.2.1. Primary Explanatory Variable

In this study, GI patents are considered a more accurate indicator of the quality of corporate GI than green utility model patents. Accordingly, following prior literature [48], we utilize the count of GI patent applications filed by firms as a proxy measure for their GI capacity. The variable is computed as the natural logarithm of (1 + the total number of green invention patent applications), to account for potential zero values.

4.2.2. Independent Variable

Urban DIT is treated as a dummy variable in this study. We construct the dummy variable for the city-level pilot policy by matching the pilot zones with their corresponding enterprises. Specifically, it is captured through the interaction between a dummy variable indicating the construction period of the NAIPZ and a dummy variable identifying the treatment group.

4.2.3. Control Variables

To ensure a rigorous evaluation of the effect of urban DIT on corporate GI, we include a comprehensive set of control variables at both the firm and city levels. At the firm level, we draw upon the methodology of Huang et al. [33], and incorporate a series of indicators that are likely to affect innovation performance. Such as firm age (FA), return on assets (ROA), CEO-Chair duality (DUAL), institutional ownership (INST), Tobin’s Q (TQ).

At the city level, following Liu et al. [49], we further control for regional socioeconomic factors. Such as educational attainment (EA), population density (POP), industrialization level (IL), fiscal expenditure intensity (FE), level of environmental regulation (ER). These control variables help isolate the specific effect of urban DIT on corporate GI by accounting for both firm-specific and city-level heterogeneity. Specific definitions are provided in Table 2.

Table 2.

Descriptive analysis of variables.

4.3. Research Model

Given that 18 prefecture-level cities have been successively approved to establish National New-Generation Artificial-Intelligence Innovation and Development Pilot Zones in China, these zones provide significant support for urban AI industry development and digital transformation, contributing substantially to the application of digitalization in corporate settings. To examine the causal effect of urban DIT on GI, we leverage the designation of pilot zones as a quasi-natural experimental setting.

Firms listed on stock exchanges and registered in the designated pilot cities are classified as the treatment group, whereas those located in non-pilot cities constitute the control group. Given the heterogeneous initiation years of the NAIPZ across cities, the conventional Difference-in-Differences (DID) approach is not applicable because it assumes a uniform policy implementation year. Accordingly, in line with prior research, we adopt a multi-period DID model for the empirical analysis:

In the model, denotes corporate green innovation of firm i in year t. The key independent variable is , which is the interaction term between the treatment group dummy and the post policy period dummy. The coefficient on captures the effect of urban digital and intelligent transformation on corporate GI. represents a set of control variables. includes individual firm fixed effects and year fixed effects. is the error term.

To test Hypotheses 2, 3, and 4, this study adopts the following mediation models to examine the mechanisms through which urban DIT improves carbon performance:

where denotes the mediating variable. All other variables have the same definitions as in Equation (1).

5. Empirical Analysis

5.1. Baseline Regression

Table 3 presents the baseline regression results examining the impact of urban DIT on corporate GI. Column (1) includes only firm and year fixed effects, revealing a positive and statistically significant coefficient (0.037) at the 5% level. After incorporating firm-level control variables in Column (2), the coefficient remains stable at 0.038 and significant. With the full set of controls included in Column (3), the estimated coefficient increases to 0.045, significant at the 5% level. This implies that a one-unit increase in urban DIT is associated with a 4.5% rise in corporate GI, ceteris paribus. The consistency of these positive and significant results across specifications provides robust evidence that DIT fosters GI among local listed firms, thus supporting Hypothesis 1.

Table 3.

Benchmark regression results.

5.2. Endogeneity Examination

5.2.1. Incorporating Baseline Variables to Mitigate Selection Bias

When evaluating the policy effects of the AI Pilot Zones, the selection of cities for the establishment of these zones is influenced by factors such as economic development, geographical location, and informatization level. Over time, these factors may exert varying effects on corporate GI performance, potentially leading to biased estimation results. To mitigate the impact of this non-random selection on policy evaluation, this paper draws on the approach of Liu and Xu (2022) [50] by adding interaction terms between city baseline factors and a linear time trend to Equation (1). The specific model is specified as follows:

Here, represents dummy variables for city baseline characteristics, specifically whether the city is a provincial capital (PC) and whether it is designated as a Special Economic Zone (SEZ). denotes the linear time trend variable. The results in Table 4 show that regardless of whether the interaction terms between city baseline factors and the time trend are introduced separately or simultaneously, the estimated coefficient for the impact of urban DIT on corporate GI performance remains statistically significant at the 5% level. This indicates that the main findings of this paper remain robust after controlling for potential estimation biases arising from pre-existing difference across cities.

Table 4.

Tests results.

5.2.2. Instrumental Variable Approach

This paper treats the AI Pilot Zone policy as a quasi-natural experiment. Although the policy pilot assignment is relatively exogenous, the approval of pilot cities is related to their local AI development levels and may also be influenced by potential omitted variables, leading to non-random selection issues. To further address endogeneity concerns, this paper draws on the approach of Nunn and Qian (2014) [51], selecting the interaction term between the city’s year-end post office count in 1984 and the number of internet users in the previous year as an instrumental variable (IV) for the establishment of the AI Pilot Zones.

On one hand, the year-end post office count reflects the development level of the city’s early information infrastructure. Cities with a higher number of year-end post offices likely held a first-mover advantage in the process of digitalization and informatization, laying the foundation for subsequent AI development. Consequently, these cities are more likely to be selected as pilot cities for the AI Pilot Zone policy, satisfying the relevance condition of the instrumental variable. On the other hand, the year-end post office count in 1984 cannot directly affect corporate GI, which satisfies the exogeneity condition of the instrumental variable.

This paper adopts an IV-2SLS approach to correct for endogeneity. The results in Table 5 (columns 1–2) verify the instrument’s strength: the Kleibergen–Paap rk LM test (p = 0.000) rejects under identification, and the Wald F statistic (40.064) exceeds the 10% threshold, negating weak instrument concerns. The first-stage regression confirms a significantly positive coefficient for the instrument. Crucially, the second-stage estimate shows that the effect of DIT remains positive and significant at the 1% level, affirming the robustness of our main finding.

Table 5.

Instrumental variable test results.

5.3. Robustness Checks

5.3.1. Pre-Trend Test

The validity of the multi-period Difference-in-Differences approach relies on the parallel trends assumption, which stipulates that, in the absence of the policy intervention, the treatment and control groups would have exhibited comparable trends in GI over time. To test this assumption, this study employs an event study approach. The specific econometric model is specified as follows:

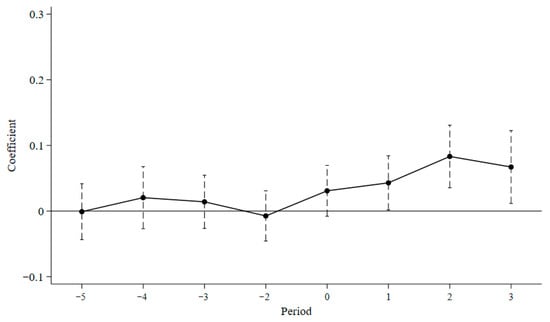

In the model, denotes a set of time dummy variables indicating the z year relative to the implementation of NAIPZ, where z = −11, −10, −9, −8, −7, −6, −5, −4, −3, −2, −1, 0, 1, 2, 3. All other variables are consistent with Model (1). To address potential multicollinearity, the period immediately before the policy takes effect (z = −1) is set as the base category. Periods prior to z = −5 are collapsed into a single category (z ≤ −5). The coefficients of interest, denoted by , capture the interaction between the and . If the coefficients are statistically insignificant when z ≤ 0, this supports the parallel trends assumption. As shown in Figure 2, for z ≤ 0, the interaction terms between and are not statistically significant, and the confidence intervals include zero. In contrast, for z > 0, these coefficients become positive and statistically significant, indicating a clear divergence after policy adoption. Therefore, the parallel trends assumption is satisfied. This finding confirms that urban DIT serves as a valid identification strategy and strengthens the robustness of the baseline regression results.

Figure 2.

Parallel-trend test (90% robust coefficient interval).

5.3.2. Sensitivity Analysis

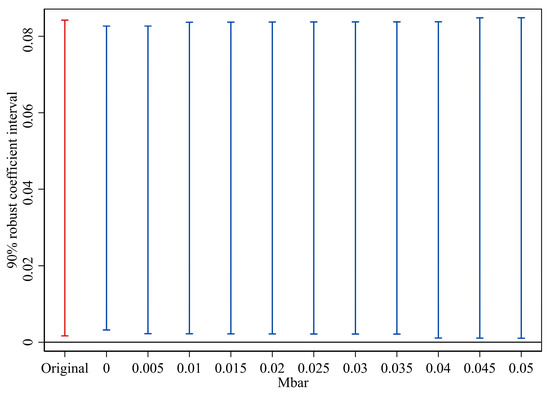

To assess the robustness of the parallel trends test, this study follows the approach of Rambachan and Roth (2023) [52] and employs the Honest Difference-in-Differences (Honest DID) method to evaluate sensitivity to potential violations of parallel trends. Furthermore, following Biasi and Sarsons (2022) [53], we set the maximum deviation level Mbar = 1 × 0.005. Under this assumption, we examine whether the post-policy coefficients deviate from the pre-policy trend that is projected to continue under this maximum plausible deviation. As shown in Figure 3, under the specified maximum deviation level, the estimated coefficient for the first year of policy implementation remains statistically significant even at the upper bound of deviation. This indicates that the estimated treatment effect is robust even if the parallel trends assumption is subject to plausible violations, thereby reinforcing the credibility of our baseline findings. The sensitivity analysis results for the second and third periods are reported in the Supplementary Materials.

Figure 3.

Parallel trend sensitivity test.

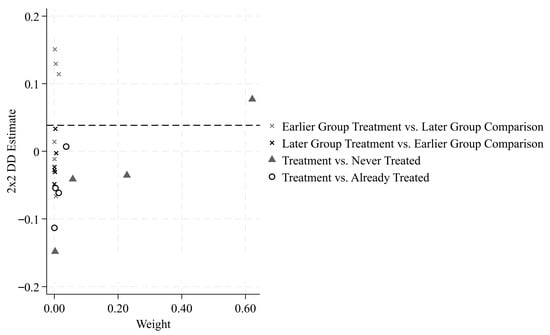

5.3.3. Goodman-Bacon Decomposition Test

In staggered Difference-in-Differences (DID) designs, treatment is not implemented simultaneously across all units. Because different units receive the policy intervention at different times. This leads to the so-called “bad control” problem (Goodman-Bacon, 2021) [54]. To examine this issue, we apply the Goodman–Bacon decomposition method. This approach breaks down the overall DID estimator into all possible 2 × 2 DID estimates based on pairwise comparisons between treatment and control groups. (Detailed decomposition results are presented in Supplementary Materials Section S5) Each pairwise estimate is weighted according to its contribution to the full-sample result. As shown in Figure 4, the share of later group treatment vs. earlier group comparison is small. This indicates that the estimated effect of urban DIT on corporate GI is unlikely to be driven by the bad control problem. A closer look at the decomposition reveals that 90.9% of the total weight comes from comparisons in which never-treated units serve as the control group. In contrast, comparisons that use already-treated units as controls—those potentially affected by the bad control problem—account for only 5.4% of the total weight. Therefore, the staggered DID estimator used in this study is robust and credible.

Figure 4.

Goodman-Bacon decomposition results.

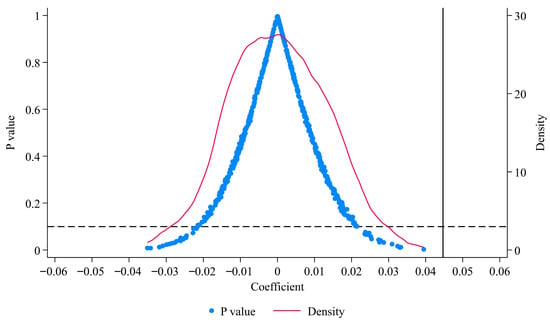

5.3.4. Placebo Test

To mitigate potential biases arising from unobserved omitted variables in the baseline regression, we conduct a placebo test. Specifically, we randomly assign pseudo-policy groups in the sample, generating fake treatment dummies. We construct a placebo test by randomly selecting a group of firms—equal in number to the actual treatment group—as a pseudo-treatment group, with the remaining firms treated as the control group. This simulation is repeated 500 times. As shown in Figure 5, the results of the placebo test indicate that the distribution of estimated coefficients is approximately normal, centered around zero, and notably distinct from the true coefficient. Moreover, the randomly generated coefficients predominantly fall to the left of the actual coefficient value of 0.045, with significant differences observed at the 1% significance level compared to the simulated random process. These findings collectively suggest that unobserved factors have not influenced the empirical results reported in this study.

Figure 5.

Placebo test (90% robust coefficient interval).

5.3.5. Exclude Interference from Other Policies

To rule out potential interference from other concurrent policies that may affect corporate GI, this study controls for several major policy initiatives. These include the Smart City Pilot program (SCP), the establishment of National Big Data Comprehensive Pilot Zones (NBDPZ), and the “Broadband China” strategy (BC). Accordingly, this study includes dummy variables for these policies in the model to account for potential confounding effects. Specifically, a dummy variable is included to indicate whether the city where a firm is located was designated as a Smart City pilot in a given year; whether it was established as a National Big Data Comprehensive Pilot Zone in that year; and whether it was included in the “Broadband China” initiative. Each dummy variable takes the value of 1 if the condition is met in the corresponding year, and 0 otherwise. As shown in Column (1) to Column (4) of Table 6, the estimated coefficients on urban DIT remain positive and statistically significant, whether we control for each policy separately or include all policy dummies simultaneously. These results align with the baseline estimates, thereby underscoring the robustness of our findings.

Table 6.

Results of Exclude interference from other policies.

5.3.6. Other Robustness Checks

To account for potential omitted variable bias at the city level—such as urban environmental conditions, innovation atmosphere, government service capacity, and governance systems—we further control for city fixed effects in the regression model. The findings reported in the first column of Table 7 yield a regression coefficient of 0.049, which is positive and significant at the 5% level, further supporting the robustness of our conclusions.

Table 7.

Robustness tests results.

To further verify the robustness of our findings, we conduct additional tests using alternative model specifications. First, we substitute the dependent variable with a composite measure of corporate GI, defined as the natural logarithm of one plus the total count of a firm’s independently filed green invention and utility model patents in a given year. As shown in Column (2) of Table 7, the coefficient of interest remains positive and significant. Second, we introduce a one-period lag to the core explanatory variable. The results in Column (3) continue to show a statistically significant positive effect, indicating that the impact of urban DIT on GI is not only contemporaneous but also exhibits some persistence.

To address potential selection bias, we employ a Propensity Score Matching (PSM) methodology to construct a balanced sample that approximates a randomized experiment. Using 1:1 nearest-neighbor matching, we construct matched samples based on the set of control variables. Subsequently, we perform staggered DID regressions on the matched sample. The results presented in Column (4) of Table 7, which apply the common support condition, indicate that the coefficient for urban DIT remains significantly positive, providing additional confirmation of the baseline model’s robustness.

Furthermore, urban DIT may be influenced by geographical location and other city-specific characteristics. Municipalities directly under the central government generally enjoy greater policy advantages and locational benefits compared to other cities. To further examine the impact of urban DIT on corporate GI, this study conducts a subsample robustness test. Beijing, Tianjin, Shanghai, and Chongqing are China’s four municipalities directly under the central government. These cities typically lead in policy piloting, resource agglomeration, and infrastructure development. As a result, they are more likely to advance DIT earlier and more intensively. This may introduce unique influences on the overall estimation results. Therefore, this study excludes these four cities from the sample. As shown in column (5) of Table 7, the positive effect on corporate GI remains statistically significant after their exclusion. This indicates that the regression results are robust.

Finally, to rule out potential spatial spillover effects of the policy on the control group through geographic proximity, which could compromise the accurate identification of the treatment effect, this study adopts the following approach for verification. First, we remove all control group cities that are geographically adjacent to the treated cities and re-run the regression analysis. As shown in column (6) of Table 7, the positive effect on corporate GI remains statistically significant after excluding these adjacent cities, indicating the robustness of the regression results.

5.4. Heterogeneity Analysis

5.4.1. Firm Size Heterogeneity

Given that firms of different sizes possess varying levels of innovation resources and production capabilities, these differences may lead to variations in how urban DIT affects their GI. To examine whether the impact of urban DIT on corporate GI differs across firm sizes, we divide the sample into two groups—large enterprises (LEs) and small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs)-based on the median value of firm size. As shown in Columns (1) and (2) of Table 8, the estimated coefficients for GI are 0.07 for large enterprises and 0.079 for SMEs. The coefficient for large enterprises is not statistically significant, whereas it remains positive and significant at the 1% level for SMEs. This finding may stem from inherent structural differences between the two groups, including variations in organizational flexibility, resource access, and responsiveness to policy measures. First, from an organizational perspective, SMEs typically have flatter management structures and more efficient decision-making mechanisms, allowing them to respond more quickly to external environmental changes and rapidly convert technological advancements brought about by digital transformation into GI practices. In contrast, large enterprises, with their multiple hierarchical layers and complex processes, exhibit lower flexibility in technology and strategy adjustments, leading to a slower pace of green upgrades. Second, regarding resource allocation, although large enterprises usually have stronger financial and technological reserves, they tend to have lower marginal willingness to invest in GI within their existing mature production systems. Conversely, SMEs, due to limited resource endowments, are more inclined to leverage emerging technologies such as artificial intelligence and big data to optimize resource allocation and improve energy efficiency, thereby achieving competitive differentiation through GI. Lastly, from a policy responsiveness perspective, SMEs are more sensitive to external policy signals and are more likely to translate supportive measures like green finance and tax incentives into actual R&D investment. Large enterprises, already possessing strong market positions and policy adaptability, depend less on policy guidance, resulting in weaker motivation for GI. Therefore, the technology empowerment and policy incentive system established by urban DIT demonstrates stronger transmission effects and incentives among SMEs, significantly enhancing their GI capabilities.

Table 8.

Analysis of heterogeneity.

5.4.2. Industry Type Heterogeneity

Considering that the impact of urban DIT on corporate GI may vary across industries, we classify listed firms into high-tech industries (HTS) and non-high-tech industries (Non-HTS) based on the Catalogue for Guiding the Development of Strategic Emerging Industries and the Industry Classification Guidance for Listed Companies (2012 Revision). As shown in Columns (3) and (4) of Table 8, the estimated policy coefficient for high-tech industries is 0.058, which is statistically significant at the 5% level; in contrast, the coefficient for non-high-tech industries is 0.024, which is not statistically significant. This difference can be explained from three perspectives: technological absorptive capacity, resource alignment, and innovation ecosystem synergy. High-tech firms generally possess stronger R&D capabilities, higher levels of digitalization, and more flexible organizational structures, enabling them to more effectively leverage technological spillovers, data resources, and policy support arising from urban DIT, thereby accelerating the development and adoption of green technologies. Moreover, as knowledge-intensive and technology-driven sectors, high-tech industries exhibit inherent compatibility between their innovation activities and digital technologies such as artificial intelligence and big data, facilitating deeper integration between the digital-intelligent environment and their GI processes. In comparison, non-high-tech industries—such as traditional manufacturing, construction materials, and textiles—often face challenges including high costs of equipment upgrading and insufficient motivation for digital transformation, which weaken their responsiveness to the benefits of urban DIT and slow the initiation and progress of GI. Furthermore, policy resources in pilot cities may be preferentially allocated to high-tech enterprises, further amplifying inter-industry differences in policy response. Therefore, the incentive effect of urbanDIT on GI is more pronounced in high-tech industries.

5.5. Mechanism Analysis

5.5.1. Enhancement of Government Governance Capacity

To examine whether government governance capacity (GGC) plays a mediating role in the process through which urban DIT affects corporate GI, we introduce it as a mediating variable in our empirical model. This paper develops a comprehensive evaluation system based on four dimensions: governance capacity in the R&D environment, governance capacity in the business environment, governance capacity in the ecological environment, and capacity in constructing a legal environment. Using principal component analysis, we construct a comprehensive composite indicator for government governance capacity, where a higher value indicates stronger overall governance performance by the local government across these dimensions. The mediation test results reported in Column (1) of Table 9 show that the regression coefficient of urban DIT on GGC is 0.350, which is significantly positive at the 1% level. This suggests that urban DIT significantly enhances the overall governance effectiveness of local governments. This indicates that urban DIT significantly enhances the overall governance effectiveness of local governments. The improvement in government governance capacity, in turn, creates an institutional environment characterized by “effective incentives and strong constraints” for corporate GI. Therefore, the empirical findings confirm that government governance capacity serves as a mediating mechanism in the relationship between urban DIT and corporate GI, thus providing support for Hypothesis 2.

Table 9.

Analysis of effect mechanisms.

5.5.2. Accelerating Corporate Digital Transformation

To investigate whether firm-level digital transformation (DT) mediates the impact of urban DIT on GI, we include it as a key intermediary variable in the empirical framework. Following the approach of Chen et al. [55], we employ Python 3.9.0 to conduct text mining on the annual reports of listed firms. By identifying, comparing, and calculating the frequency of keywords related to digital transformation—such as smart technology, big data, cloud computing, and blockchain—we classify and integrate terminology across these key domains to construct a comprehensive dataset. Based on this dataset, we develop an indicator system to measure the extent of corporate DT. This index reflects the degree to which firms integrate digital technologies into their operations and strategic planning, with higher values indicating a deeper level of digitalization. The regression results, reported in Column (2) of Table 9, yield a coefficient of 0.08, significant at the 1% level. This suggests that urban DIT significantly promotes the digitalization of local firms, likely through enhanced digital infrastructure, technology spillovers, and policy incentives. In turn, improved digital transformation enables firms to optimize production processes, enhance resource allocation efficiency, and strengthen innovation management, thereby facilitating GI. These findings provide robust empirical support for the mediating role of corporate DT and confirm the theoretical predictions of Hypothesis 3.

5.5.3. Optimization of Human Capital Structure

To further investigate the potential mediating role of human capital structure (HCS), we examine whether improvements in the quality of human capital serve as an underlying mechanism through which urban DIT exerts its influence. Following the methodology proposed by Dong et al. [56], we use the share of high-skilled labor in the total workforce as a proxy for HCS in the empirical model. This measure captures the extent to which firms benefit from a more knowledge-intensive workforce, which is critical for the adoption and implementation of innovative and sustainable practices. The regression results, reported in Column (3) of Table 9, yield a coefficient of 0.01, which is significantly positive at the 1% significance level. This suggests that urban DIT is conducive to enhancing the human capital structure of firms, potentially by facilitating access to digital tools, improving training systems, and attracting high-quality talent. In turn, such improvements may enhance firms’ GI capabilities and support the development of green technologies and processes. Therefore, Hypothesis 4 is supported.

6. Discussion, Conclusions and Policy Suggestions

6.1. Discussion

This study, leveraging the quasi-natural experiment of establishing China’s “National New Generation Artificial Intelligence Innovation and Development Pilot Zones,” systematically examines the impact of urban DIT on corporate GI.

However, compared to most literature focusing on how firms’ own digitalization levels or AI applications directly affect their GI [26,57], this paper adopts a more macro perspective of urban governance. It reveals the causal effect of policy-driven regional digital ecosystem construction on corporate innovation behavior. This suggests that promoting GI depends not only on internal technological changes within firms but also significantly on the external digital environment and innovation ecosystem constructed by their host cities. Our findings extend the research on the driving factors of corporate GI from the micro firm level to the urban system level, enriching the dimensionality of this research field.

While previous studies have placed great importance on the role of traditional policy instruments, such as environmental regulation and government subsidies, in incentivizing GI [58,59], this research highlights the positive impact generated by a new model of urban governance enabled by digital and intelligent technologies. Differing from the traditional view that relies primarily on direct fiscal incentives, this study finds that urban DIT, through constructing AI-driven intelligent regulatory systems, efficient data circulation markets, and shared technology platforms, can reshape the innovation incentives and constraints for firms in a more market-oriented and precise manner, thereby guiding resources towards green technology sectors.

In conclusion, the findings of this study emphasize the importance of strategically aligning digital economic development with the GI agenda. Urban DIT is not merely a technological revolution but also a profound governance change. It provides strong and sustainable external drivers for corporate green transformation through multiple pathways, including enhancing government governance capacity, accelerating corporate DT, and optimizing human capital structure.

6.2. Conclusions

This study uses the designation of “National New-Generation Artificial-Intelligence Innovation and Development Pilot Zones” as a quasi-natural experiment, analyzing panel data from listed companies between 2011 and 2022. By employing a multi-period Difference-in-Differences model, we evaluate the impact of urban DIT on corporate GI. The results show that urban DIT significantly promotes corporate GI. The robustness of the finding is confirmed through a series of tests, including parallel trend assumption, sensitivity analyses, placebo test, Goodman–Bacon decomposition test, controlling for other concurrent policies, and additional robustness checks. Moreover, heterogeneity analysis reveals that the policy’s impact is more pronounced among small- and medium-sized enterprises and firms in high-tech industries, while the effect is weaker for large enterprises and those in non-high-tech sectors. This disparity may stem from differences in technological absorptive capacity, resource alignment, and responsiveness to policy incentives across firm types. Mechanism analysis indicates that the policy promotes GI by improving enhancing government governance capacity, accelerating corporate DT, and human capital structure. These pathways highlight the multifaceted ways through which urban DIT supports sustainable corporate development.

In summary, this study provides robust empirical evidence that DIT serves as a powerful driver of corporate GI, particularly when supported by skilled labor, digital adoption, and innovation investment. The findings underscore the importance of integrating digital infrastructure development with sustainability goals in urban policy design. Nevertheless, this study has several limitations. First, the analysis is confined to China, where institutional arrangements, policy enforcement capacity, and industrial structure may differ substantially from those in other countries. Future research could extend this inquiry through cross-national comparisons to assess the generalizability of these findings across different economic and regulatory contexts. Second, while this study identifies broad patterns at the firm level, it does not focus on specific industries. Subsequent studies could conduct in-depth analyses on critical sectors such as manufacturing or energy-intensive industries to yield more granular insights. Finally, the long-term evolution of the synergistic effects between digital technologies and green transformation warrants further investigation. Dynamic modeling and longitudinal tracking may uncover nonlinear or lagged effects that static panel models are unable to capture.

6.3. Policy Suggestions

Based on the empirical findings and mechanism analysis of this study, we propose a four-quadrant policy framework targeting the central government, local governments, enterprises, and financial institutions, aiming to maximize the synergistic driving effect of urban DIT on corporate GI.

The central government should play the role of top-level designer, committed to scaling up pilot experiences and creating a favorable macro-policy environment. Specifically, building on the existing National New Generation Artificial Intelligence Innovation and Development Strategy, the pilot policy should be upgraded from single-city designation to a systematic “policy package,” forming a replicable solution that integrates digital infrastructure, green R&D incentives, and talent aggregation. The mechanism analysis shows that government governance capacity is an important transmission pathway. It is therefore recommended that policymakers focus on strengthening government governance capacity across multiple dimensions.

As key implementers of policy, local governments need to develop differentiated and precise empowerment plans. Heterogeneity analysis indicates that SMEs and high-tech enterprises respond most significantly. It is recommended to establish municipal-level “Green Digital Transformation Funds” to specifically support the intelligent transformation of SMEs and reduce innovation costs through shared technology platforms in industrial parks—a measure strongly supported by the highest elasticity coefficient of corporate DT (0.08). Large enterprises should be guided to act as “green supply chain leaders,” using digital tools to manage the carbon footprint of their supply chains. For high-tech industries, the formation of “green technology alliances” should be promoted, while traditional industries should implement “green intelligent upgrade” plans with subsidized loan support.

Additionally, adopt tailored strategies that address corporate heterogeneity to establish a more effective urban DIT empowerment framework that fosters GI. The influence of urban DIT on corporate GI differs across firms due to variations in size, and industry, resulting in diverse developmental trajectories. Therefore, policymakers should focus on differentiated strategies and precise guidance during the integration of AI with green development, fully utilizing digital technologies to empower GI. Specifically, small- and medium-sized enterprises tend to respond more dynamically due to their organizational agility, yet they are often constrained by limited access to capital, talent, and technology. To support them, governments should strengthen digital infrastructure funding, establish green digital transformation grants or leasing subsidies, and develop shared technology platforms in industrial parks. These platforms can provide modular, scalable green solutions to lower adoption costs and improve innovation efficiency. In contrast, while large firms may exhibit lower policy responsiveness, their central role in supply chains offers substantial spillover potential. Policymakers should encourage them to act as “chain leaders” by implementing green supply chain management systems, integrating carbon and energy performance into supplier assessments, and using digital tools to monitor end-to-end carbon footprints. Supporting large firms in establishing GI or pilot testing centers—open to SMEs—can further promote collaborative upgrading. For high-tech industries, policy should reinforce their leadership by fostering green technology innovation consortia that integrate digital tools into R&D and production. Incorporating GI metrics—such as green patent output—into high-tech enterprise evaluations can enhance policy alignment. In non-high-tech sectors, particularly traditional and resource-intensive industries, structural barriers like path dependence and slow equipment turnover impede change. A targeted “Green Intelligence Upgrade” program, supported by subsidized loans and carbon-efficiency incentives, can promote the adoption of smart systems for energy optimization and process improvement, accelerating the diffusion of proven low-carbon technologies.

At the enterprise level, there is a need to shift from passive response to actively building dual-driven capabilities in digitalization and green transformation. Enterprises are advised to make digital transformation a core strategy (coefficient 0.08), systematically advancing the deep integration of AI, big data, and IoT technologies in energy management and circular production. Simultaneously, they should leverage the talent aggregation effect of pilot cities to cultivate interdisciplinary “green digital” talent through industry–academia collaboration (human-capital-structure coefficient 0.01) on green technology breakthroughs, transforming policy dividends into sustainable competitive advantages.

Financial institutions should innovate green financial instruments to overcome transformation financing bottlenecks. It is recommended to develop AI-based ESG rating models to accurately identify the risks of green projects through data empowerment. Expand the scale of specialized credit and bonds for digital–green integration projects. Moreover, joint government-financial institution green investment risk compensation funds could be established to reduce the risk threshold for social capital participating in cutting-edge green technology investments.

Finally, construct a multi-faceted cooperation framework and mechanism. Integrate resources from central government, local governments, enterprises, financial institutions, and involve public participation and social supervision to collectively promote corporate GI. A diversified cooperation mechanism should be established, featuring government policy guidance, enterprise leadership, academic and research institution support, financial backing from financial institutions, and public oversight. Such a multi-stakeholder framework can generate strong synergies that effectively promote corporate GI. However, practical operations may encounter coordination issues and conflicts of interest. For example, companies might face short-term profit pressures due to increased costs from green transitions, conflicting with long-term sustainable goals pursued by governments. Financial institutions may be hesitant to invest in green projects due to risk concerns and return cycles. Moreover, public supervision mechanisms that lack timely and transparent information disclosure may become ineffective. To resolve these challenges, a multi-level, systematic coordination mechanism is necessary. Fiscal subsidies, tax reductions, and green credit interest subsidies can alleviate initial costs for green transitions, encouraging sustained investment. To enhance policy coherence and efficiency, cross-departmental collaboration platforms should be strengthened to improve coordination among government agencies and facilitate the sharing of resources, ensuring the consistent and effective implementation of policies. Independent third-party assessment agencies can monitor and provide dynamic feedback on green project implementation, enhancing policy transparency and societal trust in GI outcomes. In advancing corporate GI, the principle of “multi-stakeholder governance and collaborative progress” should be adhered to by strengthening institutional frameworks and mechanism design. This approach aims to stimulate the enthusiasm and proactive engagement of all parties, thereby creating a unified force that supports urban DIT and drives high-quality green development.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/su172411092/s1, Table S1. Policy Rollout Timeline. Table S2. Definitions and Descriptions. Table S3. Parallel Trend Test Results. Table S4. Goodman-Bacon decomposition results. Figure S1. Parallel trend sensitivity test (Left: Period 2; Right: Period 3).

Author Contributions

Methodology, H.J.; Conceptualization, H.J.; Writing—original draft, Z.W., W.W., T.H.; Funding acquisition, H.J.; Data curation, Z.W.; Writing—review & editing, H.J., Z.W., W.W., T.H.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Social Science Fund Project (23BRK002).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Chen, L.; Li, S.; She, Z. A study on the impact of artificial intelligence applications on corporate green technological innovation: A mechanism analysis from multiple perspectives. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2025, 103, 104490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Du, S.; Li, M. Green innovation perspective: Artificial intelligence and corporate green development. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2025, 102, 104345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Zhang, H.; Ying, J.; He, S.; Zhang, C.; Yan, J. Artificial intelligence and green transformation of manufacturing enterprises. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2025, 104, 104330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, B.; Yu, Y.; Ge, L.; Liu, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Liu, Z. The role of digital infrastructure construction on green city transformation: Does government governance matters? Cities 2024, 155, 105462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Yu, C.-H.; Zhao, J.; Lee, C.-C. How does corporate digital transformation affect green innovation? Evidence from China’s enterprise data. Energy Econ. 2025, 142, 108217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debbarma, J.; Choi, Y. A taxonomy of green governance: A qualitative and quantitative analysis towards sustainable development. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 79, 103693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, F.; Lian, H.; Liu, X.; Wang, X. Can environmental regulation promote urban green innovation Efficiency? An empirical study based on Chinese cities. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 287, 125060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, X.; Cheng, W.; Gao, Y.; Balezentis, T.; Shen, Z. Is environmental regulation effective in promoting the quantity and quality of green innovation? Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 6232–6241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Tong, Y.; Ye, F.; Song, J. The choice of the government green subsidy scheme: Innovation subsidy vs. product subsidy. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2020, 58, 4932–4946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Y.; Chen, Z. Can government subsidies promote the green technology innovation transformation? Evidence from Chinese listed companies. Econ. Anal. Policy 2022, 74, 716–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, D.; Qiu, L.; She, M.; Wang, Y. Sustaining the sustainable development: How do firms turn government green subsidies into financial performance through green innovation? Bus. Strategy Environ. 2021, 30, 2271–2292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Chen, C.; Lei, L.; Zhang, Y. Impacts of green finance on green innovation: A spatial and nonlinear perspective. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 365, 132548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Qi, S.; Zhou, C.; Zhou, J.; Huang, X. Green credit policy, government behavior and green innovation quality of enterprises. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 331, 129834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Liu, X.; Wang, H. Green bonds, financing constraints, and green innovation. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 381, 135134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, Z.; Wang, L.; Lai, F. Customer pressure and green innovations at third party logistics providers in China: The moderation effect of organizational culture. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2019, 30, 57–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Jin, J.; Li, M. Does media coverage influence firm green innovation? The moderating role of regional environment. Technol. Soc. 2022, 70, 102006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iamandi, I.-E.; Constantin, L.-G.; Munteanu, S.M.; Cernat-Gruici, B. Mapping the ESG behavior of European companies. A holistic Kohonen approach. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siew, R.Y.; Balatbat, M.C.; Carmichael, D.G. The impact of ESG disclosures and institutional ownership on market information asymmetry. Asia Pac. J. Account. Econ. 2016, 23, 432–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, K.; Qin, C.; Ma, S.; Lei, X.; Hu, Q.; Ying, J. Impact of ESG disclosure on corporate sustainability. Financ. Res. Lett. 2025, 78, 107134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, Y.; Cai, Z.; Lin, H.; Yuan, M.; Mao, Y.; Yu, M. Does better environmental, social, and governance induce better corporate green innovation: The mediating role of financing constraints. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2022, 29, 1513–1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muisyo, P.K.; Qin, S. Enhancing the FIRM’S green performance through green HRM: The moderating role of green innovation culture. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 289, 125720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, H.; Chen, Z. The driving effect of internal and external environment on green innovation strategy-The moderating role of top management’s environmental awareness. Nankai Bus. Rev. Int. 2019, 10, 342–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Zhang, Q. Digital transformation, corporate social responsibility and green technology innovation-based on empirical evidence of listed companies in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 424, 138805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Xue, Y.; Yang, J. Boundary-spanning search and firms’ green innovation: The moderating role of resource orchestration capability. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2020, 29, 361–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Sun, T.; Li, R. Does artificial intelligence promote green innovation? An assessment based on direct, indirect, spillover, and heterogeneity effects. Energy Environ. 2025, 36, 1005–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.-C.; Xu, X.-H. Intelligence-Driven Growth: Exploring the Dynamic Impact of Digital Transformation on China’s High-Quality Economic Development. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2025, 101, 104240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Wang, S.; Wang, X. How does artificial intelligence impact green development? Evidence from China. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassânego, V.M.; Moralles, H.F.; Nascimento, D.L.d.M.; Tortorella, G.L. Exploring the role of open innovation and artificial intelligence in green innovation: A dynamic capabilities approach. J. Innov. Knowl. 2025, 10, 100774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.; Shang, Y. How artificial intelligence drives industrial digitalization and greening synergies? Evidence from China’s AI innovation and development pilot zones. Technol. Soc. 2025, 83, 103011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, B.-Q.; Yang, Y.-X. Building efficiency: How the national AI innovation pilot zones enhance green energy utilization? Evidence from China. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 387, 125945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guan, T.; Zheng, R.; Chen, A. Artificial Intelligence and Corporate Energy Consumption: The Policy Effects of the New-Generation Artificial Intelligence Innovation and Development Pilot Zones. Econ. Anal. Policy, 2025; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Liu, S.; Gan, J.; Liu, B.; Wu, Y. How does the construction of new generation of national AI innovative development pilot zones drive enterprise ESG development? Empirical evidence from China. Energy Econ. 2024, 140, 108011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, H.; Zhang, J.; Yuan, K. Digital horizons, green futures: How does new-generation artificial intelligence pilot zone drive corporate low-carbon transformation? J. Asian Econ. 2025, 100, 102000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Zhou, N.; Zhao, X.; Yang, S. The impact of artificial intelligence on corporate green innovation: Can" increasing quantity" and" improving quality" go hand in hand? J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 376, 124439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mijit, R.; Hu, Q.; Xu, J.; Ma, G. Greening through AI? The impact of Artificial Intelligence Innovation and Development Pilot Zones on green innovation in China. Energy Econ. 2025, 146, 108507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Wang, L. Artificial intelligence and enterprise green innovation: Evidence from a Quasi-Natural experiment in China. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nambisan, S.; Wright, M.; Feldman, M. The digital transformation of innovation and entrepreneurship: Progress, challenges and key themes. Res. Policy 2019, 48, 103773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klingebiel, R.; Rammer, C. Optionality and selectiveness in innovation. Acad. Manag. Discov. 2021, 7, 328–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- North, D.C. Institutions and economic theory. Am. Econ. 1992, 36, 3–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Hoang, T. Impact of integrated artificial intelligence and internet of things technologies on smart city transformation. J. Tech. Educ. Sci. 2024, 19, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakura, S. Open innovation as a driver for new organisations: A qualitative analysis of green-tech start-ups. Int. J. Entrep. Ventur. 2020, 12, 109–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Qu, J.; Wei, J.; Yin, H.; Xi, X. The effects of institutional investors on firms’ green innovation. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2023, 40, 195–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Cheng, P.; Yang, F. Study on the impact of digital transformation on green competitive advantage: The role of green innovation and government regulation. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0306603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Gao, Y.; Hu, S.; Sun, M.; Zhang, C. How does digitalization affect the green transformation of enterprises registered in China’s resource-based cities? Further analysis on the mechanism and heterogeneity. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 365, 121560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Sun, G.; Kong, T. The impact of digital transformation on enterprise green innovation. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2024, 90, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bircan, I.; Gencler, F. Analysis of innovation-based human resources for sustainable development. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 195, 1348–1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du Plessis, M. Drivers of knowledge management in the corporate environment. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2005, 25, 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.; Dai, J.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, X. Does environmental regulation induce green innovation? A panel study of Chinese listed firms. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2022, 176, 121492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Li, Y.; Chen, X.; Liu, J. Evaluation of low carbon city pilot policy effect on carbon abatement in China: An empirical evidence based on time-varying DID model. Cities 2022, 123, 103582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Xu, H. Does low-carbon pilot city policy induce low-carbon choices in residents’ living: Holistic and single dual perspective. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 324, 116353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunn, N.; Qian, N. US Food Aid and Civil Conflict. Am. Econ. Rev. 2014, 104, 1630–1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rambachan, A.; Roth, J. A more credible approach to parallel trends. Rev. Econ. Stud. 2023, 90, 2555–2591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biasi, B.; Sarsons, H. Flexible wages, bargaining, and the gender gap. Q. J. Econ. 2022, 137, 215–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman-Bacon, A. Difference-in-differences with variation in treatment timing. J. Econom. 2021, 225, 254–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]