Abstract

This study evaluates the use of recycled materials in producing hollow section structural beams (HSSBs) from agglomerated sheets of thermo-stiffened polymeric aluminum (TSPA) derived from post-consumer Tetra Pak® containers. A novel geometric configuration for the TSPA beam assembly is proposed to reduce the deflections observed in the original Casa Eco Sísmica (CES) project. A combined numerical and statistical approach, incorporating Monte Carlo simulations and finite element method (FEM) models, was employed to assess different assembly alternatives and identify the configuration with the lowest deflection, while maintaining values below the L/78 limit. Experimental tests, were performed to compare the proposed configuration with the existing CES beams. Results show that the new configuration reduces deflections by 61% and increases vertical load capacity by 287% compared to the original beams. These findings highlight the critical influence of assembly methods on the structural performance of TSPA beams. The original configuration exhibited deficiencies in deflection and load-bearing capacity due to its construction method, whereas the new assembly efficiently exploits the mechanical properties of the TSPA material.

1. Introduction

Housing availability is a critical issue in Colombia, where 31% of households experienced a housing deficit in 2021 [1]. Informal housing construction is also increasing, with more than 35 million square meters built between 2007 and 2018, representing risks to residents living in non-conforming structures that do not comply with Colombian construction standards [2]. Therefore, it is necessary to explore new materials and methods to provide affordable housing that meets code requirements. Construction additionally has a significant environmental impact, accounting for 37% of global CO2 emissions, according to the UN; thus, new solutions must align with sustainability guidelines and future waste management strategies [3]. In parallel, inadequate solid waste management is a contributor to climate change, responsible for nearly 4% of global greenhouse gas emissions [4]. The World Bank estimates that by 2030, 2.5 million tons of solid waste will be generated annually worldwide, of which only 13% will be recycled, including construction waste. Post-consumer Tetra Pak® packages represent a reusable solid waste stream, with 13,650 tons produced annually in Colombia, but only 12% recycled [5]. Recycled Tetra Pak products generally lack direct application in structural housing and have been limited to non-structural uses such as roof tiles and wall finishes [6,7], although they have been identified as a potential alternative for masonry [8].

To address basic housing needs within a sustainable framework aligned with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), the Casa Eco Sísmica (CES) project was launched in 2015 by Pontificia Universidad Javeriana (Bogotá, Colombia). This housing system, known as Homeko, seeks to provide a functional and seismic-resistant temporary unit using thermo-stiffened polymeric aluminum (TSPA) sheets, a material derived from recycled post-consumer Tetra Pak® containers [9]. As a plastic-based recycled product, TSPA contributes to reducing plastic waste, conserves energy compared to virgin plastic, supports local economies through circular economy practices, and achieves a product quality capable of meeting local mechanical standards [10]. Applications of this type of recycled solid waste in direct structural use remain under evaluation and are scarcely represented in the literature. According to Scopus and Web of Science, a search using the keywords sustainable, construction, and recycled waste yields at least 4885 references addressing recycling applications in construction, many of which focus on cement, concrete, and aggregates derived from demolition. Narrowing the search by adding the keyword ‘structural’ reduces the number of documents to 105, with solutions involving plastic rebars, recycled aggregates, recycled asphalt, and plastics reinforced with natural fibers, but few comprehensive structural systems are described. Further filtering with the keyword ‘application’ identifies only seven references describing fully developed structural systems based on recycled solid waste. Among these, only one reports an experimental test, involving recycled plastic specimens of 145 mm length, evaluated in a setup without a shear-free region, focusing exclusively on tensile and compressive demands [11].

Homeko is not the only structural solution that explores functionality from non-conventional materials within space constraints. In recent years, researchers worldwide have investigated alternatives such as cardboard for affordable housing and examined their impact on residents [12,13,14]. Construction is increasingly moving toward eco-friendly approaches, often combining traditional materials (e.g., wood [15]) with recycled compounds to preserve mechanical performance while incorporating solid waste. However, these solutions face challenges, as environmental factors can compromise durability [16], particularly when certain wastes, such as diapers, are considered as components in composite construction materials [17].

TSPA is widely used in furniture and other products that do not require specific mechanical properties. However, its potential as a structural material has not been extensively studied, leaving a clear opportunity to expand knowledge of its capacity and applications. The CES project conducted a mechanical characterization of the flexural and compressive behavior of structural elements made with TSPA sheets, demonstrating the feasibility of developing complete structural solutions with this material [18]. Subsequent research characterized the tensile properties of TSPA (adapting the ASTM E8 standard [19]) and evaluated the dynamic performance of moment-frame connections under cyclic loads [20]. Later studies on the technical and financial feasibility of the housing system [21] supported a proof of concept in 2021 [22], during which two full-scale prototypes were constructed to assess construction constraints and processes.

The main conclusion from this full-scale test concerned the geometric configuration of the flooring system, which produced deflections exceeding the acceptable limits for housing structures under the Colombian construction code [23]. This drawback highlighted the need for an alternative assembly method to reduce excessive deflections. Initial findings indicated that the issue came from the assembly of girders with a mechanical midspan connection, which caused rigid-body rotations and, consequently, excessive deflections. Therefore, improving the flooring system requires construction solutions that directly address this limitation.

2. Materials and Methodology

Thermo-stiffened polymeric aluminum (TSPA) is a relatively new material produced through the recycling of Tetra Pak® containers. The process begins with the mechanical separation of the polymeric and aluminum layers, followed by grinding, during which all cardboard components are removed using pressurized water. The polymeric and aluminum fragments, reduced to pieces between 4 and 40 mm, are then compressed at approximately 600 psi and heated to about 400 °C. After pressing, the sheets are rapidly cooled with a –4 °C water spray, stiffening their surfaces. This thermo-stiffening process takes about 15 min. The resulting product is available in sheet thicknesses of 10, 15, 20, and 25 mm, with standard dimensions of 1220 × 2440 mm and an average unit weight of 1070 kg/m3 [18].

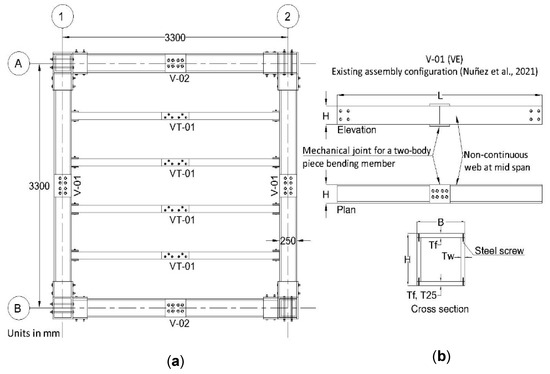

The flooring system (Figure 1a) is a lightweight structure composed of TSPA girders, beams (V-01 and V-02), and joists (VT-01). The hollow section structural beams (HSSBs) were fabricated from TSPA sheets with a modulus of elasticity of ETSPA = 789 MPa and a design elastic limit stress of Fela-TSPA ≈ 4.4 MPa, based on previous tests of this material [20,23]. For the present study, elements of different thicknesses (15, 20, and 25 mm) were used according to a modified structural design. The girders have a hollow rectangular cross-section of 250 × 250 mm (Figure 1b) and are reinforced with internal stiffeners. All parts were assembled with self-drilling steel screws to ensure mechanical friction between sheets. Each girder spans 2800 mm and is simply supported by rollers at both ends. This geometry matches the dimensions specified in the original CES flooring system design. The initial system consisted of two separate members joined by a continuity steel plate and eight 19 mm structural steel bolts, as shown in Figure 1a,b [22].

Figure 1.

(a) Flooring system geometry under study. (b) Geometrical parameters as random variables for an existing HSSB assembly beam configuration (adapted from [22]).

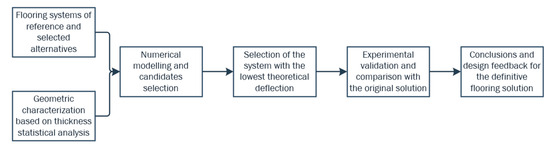

This study combines numerical modeling and full-scale testing to evaluate the structural behavior of TSPA girders, using a new construction process designed to prevent rigid-body displacements. The approach, based on rigorous statistical analysis followed by experimental validation, seeks to identify an efficient design candidate from numerical simulations to address the excessive deflections observed in the original CES flooring system. The research methodology consisted of the steps presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Methodology used in the present research to select a candidate girder construction option to improve midspan deflections.

- Geometric Characterization and Statistical Analysis: The initial characterization of the cross-sectional geometry of girder V-01 (Figure 1b) identified the parameters that, when treated as random variables, most strongly influenced TSPA midspan deflections. A performance index (PI) function was then defined to quantify the reduction in deflections relative to those observed with the original geometry, as reported in the proof of concept by Nuñez-Moreno et al. [23].

- Literature Review and Proposed Alternatives: In parallel with the statistical analysis, a literature review was conducted on reinforcement alternatives using different materials or geometric assemblies that could be adapted to TSPA girders to improve the final design. Based on this review, three reinforcement alternatives were selected as potential candidates.

- Numerical Modeling and Design Selection: Monte Carlo simulations and finite element method (FEM) models were used to calculate the PI for each alternative, based on the previously defined variables. The PI was defined as the ratio between the numerical midspan deflection and the value reported by Nuñez-Moreno et al. [23] (Equation (1)). The alternative with the lowest deflection index was selected for the experimental phase and designated as the best solution.

- Experimental Validation: Seven full-scale prototypes of the selected solution were built and tested. The tests followed an adaptation of the ASTM C78-22 standard to experimentally validate the midspan deflection [24].

3. Approach

3.1. Random Variable Definition

According to the experimental setup, all parameters influencing midspan deflection were defined as random variables of the system (geometry, loads, and material properties), reflecting the uncertainty inherent in the structural response. The random variables directly affecting the cross-sectional inertia were defined as follows: thick-sheet thickness (T25), internal stiffener thickness (Ts), flange thickness (Tf), web thickness (Tw), girder base (B), and girder height (H) (see Figure 1b).

The deflection ratio for a structural element under bending is a function of the moment of inertia, beam span (L), applied load (P), and the modulus of elasticity of TSPA (E). The load (P) was treated as a deterministic variable, since it was controlled by a monotonically incremental loading protocol during the tests.

Data were analyzed using the Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MLE) method implemented in an open-source Python code [25]. This method evaluated 31 probability distribution functions (PDFs) with data obtained from direct measurements of the cross-sectional parameters and from previously reported mechanical parameters [20] of the full-scale prototypes built during the 2021 proof-of-concept tests. Table 1 summarizes the measured values of the random variables under study.

Table 1.

Magnitudes and probability density functions associated with the variation in each parametric variable for a TSPA girder construction.

For this research, and given the sensitivity of the deflection analysis, geometric variables with a coefficient of variation (CoV) below 3% were treated as deterministic parameters, since they are directly related to prefabrication and can be improved through fabrication standardization [26]. Among the random variables considered in the deflection analysis, the modulus of elasticity exhibited the highest CoV at 13.8% (based on 25 data points), which is directly linked to the industrial processes of the local TSPA producer.

A finite element method (FEM) model was developed to simulate deflections, incorporating the variability of the selected random variables through Monte Carlo simulations.

3.2. Selection of a Candidate-Assembly Solution

A comprehensive study of alternative hollow structural members and their assembly considered both construction practices using TSPA and a literature review of housing construction. For this purpose, a selection matrix (Table 2) compared seven criteria: (i) adaptability to the original flooring system, (ii) weight of TSPA used in the reference, (iii) explicit weight of other materials used, (iv) type of cross-section proposed, (v) bonding type (mechanical, chemical, or mixed), (vi) number of assembly connections required to maintain continuity, and (vii) compatibility of the candidate solution with the architectural design of the original Homeko system. Options 1–3 correspond to constructive adaptations of the CES project configuration, while Options 4–9 were drawn from selected reported references (Table 2).

Table 2.

Alternative selection matrix.

TSPA sheets are commercially produced with standard dimensions of 1220 × 2440 mm. As a result, the original beam was built from two 1500 mm sections joined by a central bolted connection (Figure 1b). Thus, it is not possible to construct a continuous 2800 mm beam using commercially available sheets. After evaluating the alternatives in Table 2, Options 1, 2, and 3 were selected for numerical simulations, as these geometries (i) preserve the architectural integrity of the generic construction project, (ii) do not require chemical bonding, and (iii) use a lower weight of TSPA material compared to all other solutions considered.

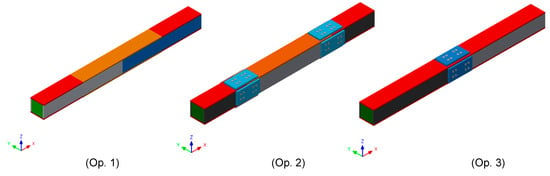

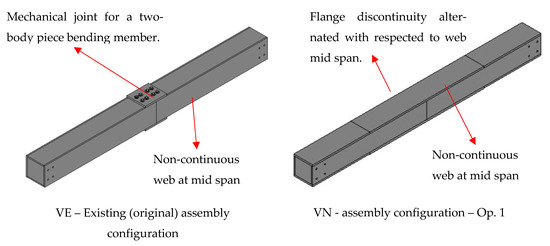

The three selected options focused the numerical analysis on identifying the most suitable solution. Figure 3 schematically illustrates the selected reinforcement alternatives.

Figure 3.

Selected reinforcement options. Op. 1: Continuous girder with variations in the assembly of the flanges and webs. Op. 2: Three-part girder, with continuity plates at each third of the span, with shear plates included. Op. 3: Original beam, including a shear connection at the center.

4. Numerical Study

4.1. Numerical Approach

Simulating polymeric materials with the finite element method (FEM) often requires a high level of discretization, which can make structural evaluations overly complex. For example, Böl and Reese [33] demonstrated that modeling lattice-level behavior in polymeric networks demands major simplifications—such as neglecting volume changes under loading—which can lead to deviations from linear elastic behavior (e.g., Poisson’s ratio). In civil and structural applications, such as polymer bars used to reinforce bending elements, FEM analyses frequently assume a linear elastic material model [34]. However, this assumption can introduce inaccuracies, particularly when the material exhibits brittle behavior near its elastic limit. To address these limitations, some authors instead conduct direct stress–strain tests of polymeric specimens or evaluate composite structural elements at higher scales [35].

Following this approach, the present research employed an elastic FEM to evaluate the behavior of the assembly for the three selected alternatives. The analysis was conducted using SAP2000 Ultimate v.20.1.0 (Computers and Structures Inc., Berkeley, CA, USA), assuming material isotropy. All models were simply supported and consisted of quadrilateral shell elements and two-joint frame elements, with 24 and 12 degrees of freedom, respectively.

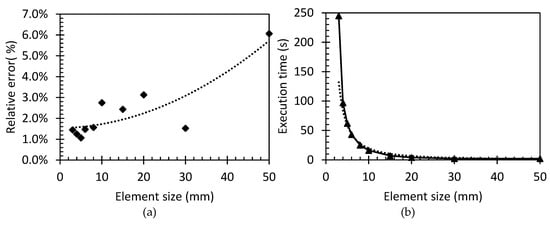

A convergence analysis was conducted to determine the appropriate mesh size for all girder models. Figure 4 shows that as the finite element size decreases, the relative error in displacements also decreases, while execution time increases. Based on this analysis, a mesh size of 10 mm was adopted as suitable for the numerical approach.

Figure 4.

Mesh size calibration for the numerical models: (a) relative error curve as a function of mesh size; (b) run time curve as a function of mesh size. Dotted line shows an approximated data behavior as a function of mesh sizing.

4.2. Monte Carlo Simulations

Using the information in Table 1, random data were generated through Monte Carlo simulations. The probability density functions (PDFs) that best fit each random variable were determined with open-source Python v.3.11.0 code [25]. Through integration between Python and the SAP2000 v.20.1.0 API, 3000 iterations were performed for each assembly option (Options 1–3), combining the previously defined random variables. The Python code randomly assigned magnitudes to the geometric variables, updating the SAP2000 v.20.1.0 cross-secion database and material definitions. The structural analysis then performed an elastic simulation for the given loads and reported the midspan deflection. This process was systematically repeated for each of the 3000 models per assembly option, producing a database of midspan deflections as a function of cross-sectional geometry and modulus of elasticity variability.

For each simulation, a deflection performance index (PI) was computed, as defined in Equation (1), representing the ratio of the simulated midspan deflection to the limit of L/78. This limit was established in previous research as the maximum allowable deflection under service conditions for a girder made of TSPA [22]. The PI was also treated as a random variable with its own probability density function (PDF).

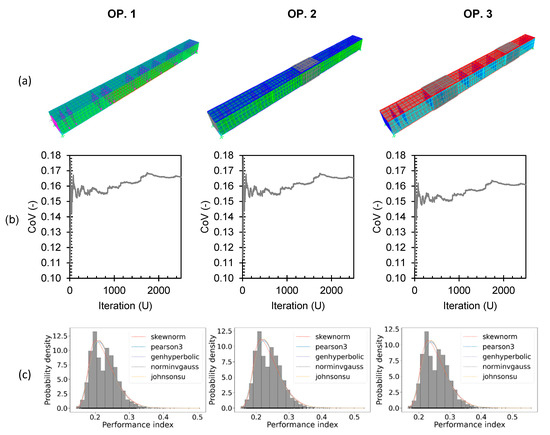

The skew-normal PDF was found to best fit the simulation results for all three options, as shown in Figure 5c.

Figure 5.

(a) FEM models in SAP2000 for each assembly option (Op. 1 to Op. 3). (b) Convergence of CoV as a function of PI, combining variables from Monte Carlo simulations of construction options (Op. 1 to 3). (c) P.I. probability density distribution fitting process for 3000 Monte Carlo simulations of each assembly option (Op. 1 to 3).

Figure 4b illustrates the convergence of the coefficient of variation (CoV) of the PI. The results indicate that after 2000 iterations, the CoV shows no significant variability, confirming the stability of the response and establishing the cross-sectional parameters.

Table 3 presents the PI statistics comparing the different girder assembly alternatives modeled numerically. The results suggest that Option 1 exhibited the lowest deflection, accounting for both geometric and mechanical variability associated with the TSPA sheets.

Table 3.

Average performance index of alternatives.

Based on the numerical results of midspan behavior and the selection criteria in Table 2, Option 1 was identified as the assembly solution that theoretically improves the reported deflections [22], thereby enhancing the serviceability of the TSPA flooring system. The next step focused on full-scale tests to evaluate midspan deflection in the selected assembly.

5. Experimental Study

Seven full-scale specimens were fabricated using Assembly Option 1 (see Table 2), which enabled the construction of a TSPA girder without mechanical overlapping plates (see Figure 3). The specimens were tested under service load conditions to measure midspan deflections and compare the results with those obtained from the numerical simulations. These specimens were designated with the testing code VN.

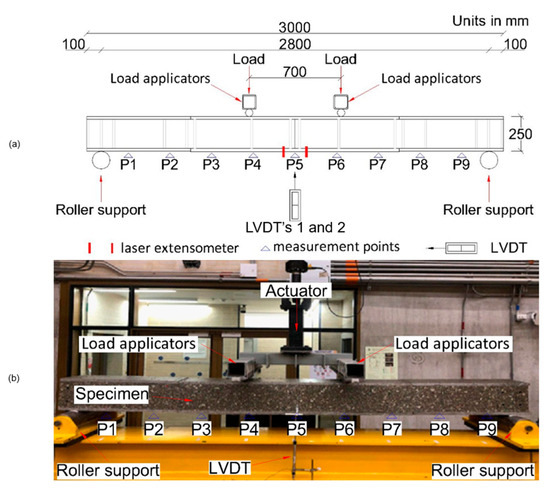

The experimental setup and the locations of the displacement measurement points (P1–P9) are shown in Figure 6. Following the ASTM C78-22 standard, midspan displacements were recorded for a simply supported beam configuration with loads applied at the thirds of the span. A displacement-controlled loading protocol was applied at a rate of 3 mm/min using an MTS DuraGlide 244.22 servo-hydraulic actuator (MTS systems, Eden Praire, MN, USA) with a load capacity of 100 kN. Load distribution was achieved using HSS steel sections (100 × 100 × 6 mm) and circular bars (55 mm diameter), both fabricated from ASTM A36 steel [36]. The structural behavior was monitored by recording the applied load directly from the MTS actuator. Midspan displacements were measured with two linear OMEGA LD620-75 LVDTs (Dwyer Instruments, LLC, Norwalk, Connecticut, CT, USA), while additional displacements at intermediate points were recorded with a Bosch GLM20 laser distance meter (Robert Bosch GmbH, Gerlingen, Germany). The strain in the lower flange at midspan was measured throughout the test using an MTS LX1500 laser extensometer (MTS systems, USA).

Figure 6.

Experimental test setup: (a) instrumentation schematic; (b) laboratory setup.

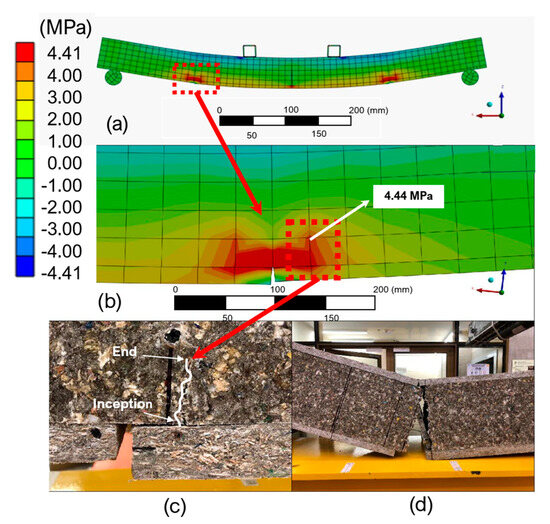

Prior to the physical tests, a new finite element method (FEM) model developed in ANSYS 2022/R2 was used to simulate the test behavior, with a focus on identifying potential failure zones. As with the SAP2000 model described earlier, the numerical analysis was performed as a linear elastic simulation assuming isotropic material behavior, using SOLID186, TARGET170, and CONTACT174 elements. The resulting normal stresses in the X-direction (Figure 7a,b) indicated a plausible stress concentration at the lower web-to-flange transition, where stresses exceeded Fela-TSPA (4.4 MPa; Table 6). This suggested a potential crack initiation zone, corresponding to a discontinuity in the lower flange caused by a change in plate thickness. Consequently, it was expected that tensile stresses in the bottom flange would be redistributed through the vertical walls, promoting an upward failure progression as the test advanced.

Figure 7.

Comparison of experimental and numerical failure modes: (a) FEM model showing the elastic stress concentration area in the context of the whole girder; (b) stress concentration zone as predicted by the FEM model; (c) web zone detail in the tested girder where cracking took place; (d) beam collapse as crack moved upwards (units in MPa).

6. Results

6.1. Qualitative Failure Analysis

All tested specimens exhibited the same failure mechanism: an upward-propagating crack originating in the lower web-to-flange transition. This crack initiated at the discontinuity of the tension flange caused by the assembly design. Although the lower flange was intended to transfer tensile loads continuously, it was interrupted at a section where its thickness increased to help control bending stresses and midspan deflection. This thickness transition created a stress concentration in the web. The FEM model identified the approximate load at which the girder exceeded the elastic range, occurring at 9.8 kN (applied through the two HSS steel elements; Figure 6a), with a corresponding midspan displacement of 16.5 mm. This load was defined as the upper limit at which vertical loading became unsafe due to crack initiation (Figure 7c,d).

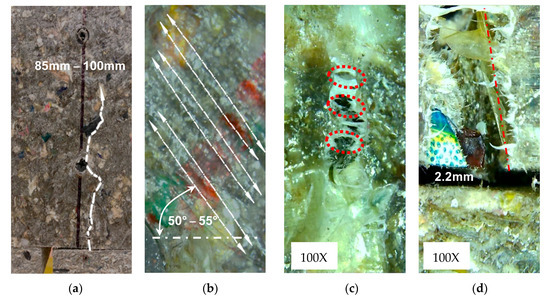

Qualitative observations showed that cracks initiated at the hole of the self-drilling steel screw connecting the vertical stiffener (Figure 8a). The crack then propagated upward, following the nearest hole and forming a failure plane. Near the supports, a combined buckling–tension zone was observed within the TSPA plastic matrix, suggesting the development of a tension-field failure where shear stresses were highest (Figure 8b). The angle of this tension field was estimated at approximately 50–55°, indicating a shear-like failure pattern.

Figure 8.

Failure modes and micrographic photograph at 100X of the crack tip failure on the plastic matrix of the material: (a) Crack length and crack tip advance due to material discontinuity. (b) TSPA plastic matrix tension field near high-shear zones close to the supports. (c) Crack formation mechanism. (d) Open crack at its inception.

6.2. Deflection Analysis

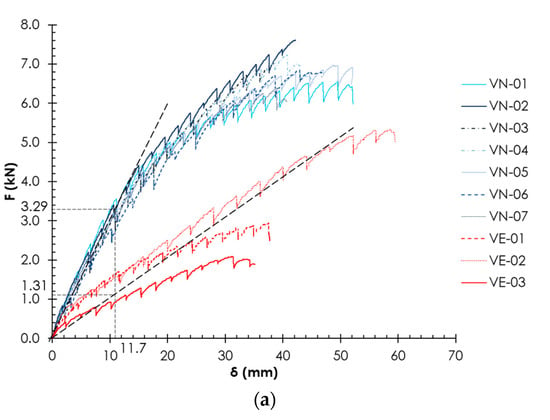

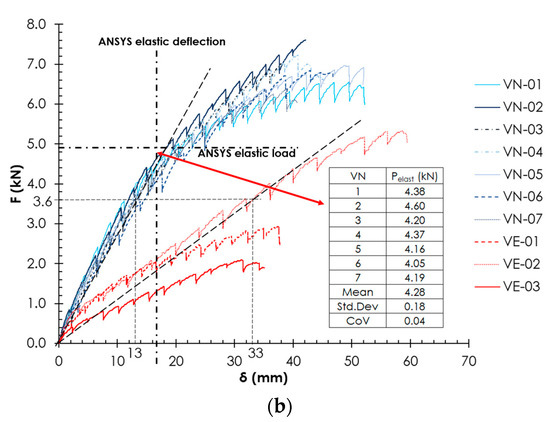

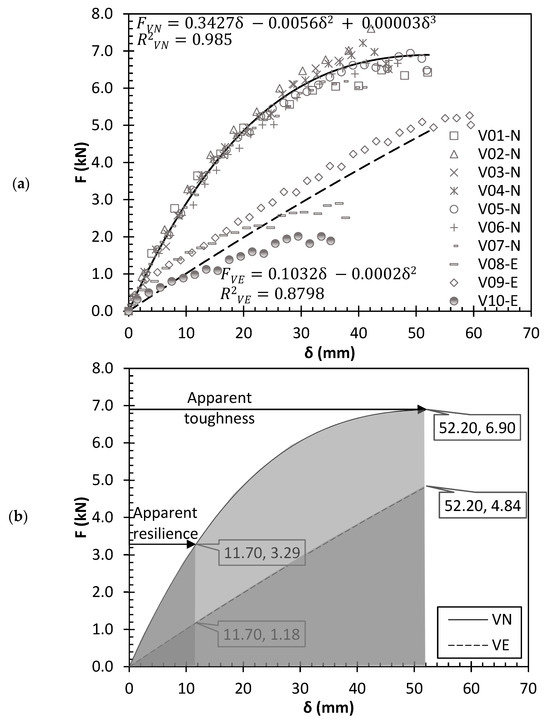

Testing seven specimens with the new assembly configuration (VN) and three girders with the original configuration (VE) enabled a detailed analysis of mechanical response through load–displacement diagrams (Figure 9). Despite the limited number of VE girders tested in the elastic range, the VN assembly demonstrated a 287% increase in bending capacity (Figure 10a) and a 61% improvement in deflection performance (Figure 10b).

Figure 9.

Geometric differences in the existing (original) girder assembly (VE) and the proposed new assembly (VN).

Figure 10.

Applied load vs. midspan deflection diagrams for the VN and VE girder assembly tests: (a) for a reference displacement; (b) for a reference applied force vs. the ANSYS model suggestions.

Comparing the theoretical elastic load limit suggested by the numerical model (a midspan deflection of 16.5 mm at 4.9 kN) with the average experimental results for the VN girder assembly tests (see Table in Figure 10b), it is seen that the model reproduced the midspan deflections of the VN girders with 87.2% accuracy. In other words, the ratio between the numerically predicted elastic load and the experimental average was 4.28 kN/4.9 kN = 0.872. This highlights the need for refinement in model parameters such as modulus of elasticity, assembly details, and the influence of steel screws. Nevertheless, for practical purposes and an initial assessment, the approximation is considered acceptable.

The zig-zag pattern observed in the load–midspan displacement diagrams (Figure 10) may be attributed to crack initiation or propagation in the stress concentration zone described in the previous section. It may also be linked to the multiple discontinuities created by the holes of the steel screws used to join the individual TSPA sheets into a monolithic girder.

The results show a consistently increasing load capacity with two distinct stages: (i) an elastic response and (ii) an inelastic response followed by failure. At a finer scale, this behavior may be linked to plastic matrix dislocations in the TSPA or to inter-particle boundaries formed during the industrial thermo-stiffening process used to manufacture the sheets. Further research is recommended to investigate these mechanisms at the micro-scale, which lies beyond the scope of this study (see Figure 8d).

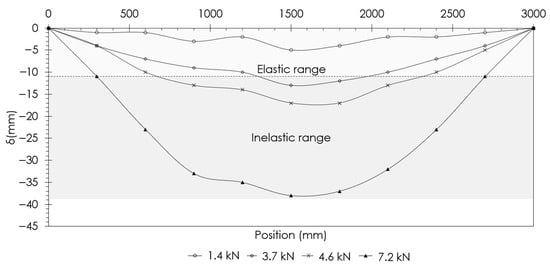

Figure 11 shows the deflection response of girder VN-02 at selected points as the load increased. The elastic limit, defined as the allowable deflection of L/78 according to previous research [22], is also indicated. Results suggest that a TSPA girder can sustain up to 4.5 times its elastic limit deflection before collapse. The same procedure was applied to all other VN and VE girders.

Figure 11.

Deflections at selected control points (P1 to P9) along girder VN-02.

Table 4 presents the experimental midspan deflection statistics for both the VN and VE girders in the elastic and inelastic ranges. In the elastic range, the VN girders exhibited a CoV of 8.1%, compared to 42.6% for the VE girders.

Table 4.

Statistics of the experimental midspan deflections for TSPA VN and VE girder assemblies.

These findings suggest that the proposed VN girder assembly mitigates complex interactions—such as relative displacements between TSPA sheets and internal defects from the reinforcement process—that previously caused unexpected rigid-body behavior and increased midspan deflection. In both the elastic and inelastic ranges, the VN assembly exhibited lower uncertainty, indicating an improved construction methodology that ultimately enhances mechanical reliability. However, this aspect was not explored in depth in the present research due to the limited number of available VE and VN specimens.

Regarding the inelastic behavior of the VN girders, a marked variability in deflections was observed, with a CoV of 11.8% in this range. This trend aligns with Figure 10, where the elastic zone of the seven VN girders shows similar responses among specimens, but deflections diverge once the inelastic range is reached. These findings indicate that the design of this girder type should remain within the elastic range. In contrast, the VE girders exhibited the opposite trend, with higher variability in the elastic range compared to the inelastic range. The limited statistical evidence, combined with Figure 10, highlights the need for a broader experimental campaign, as only three VE girders were available (from previous research [22]) and no well-defined elastic zone could be established. This limitation makes it difficult to discern whether the observed non-linearity corresponds to the intrinsic inelastic behavior of the material or to relative displacements between girder components. Nevertheless, the results suggest that the VN assembly provides an improved construction method, yielding a closer agreement between theoretical and experimental midspan deflections for TSPA girders (see Table 4).

6.3. Approximated Mechanical Properties for a TSPA Girder

Figure 12a presents the least squares method (LSM) fit for the three VE girders and the seven VN girders. The resulting equations provide a simplified model relating force and midspan deflection, enabling an approximation of energy-based mechanical parameters for TSPA girders.

Figure 12.

Least squares mathematical models for the mechanical response of applied load vs. midspan deflection: (a) for each VN and VE girder assembly test; (b) schematic average resilience capacity and apparent toughness with their integration limits for the VN and VE girder assemblies tested (kN·mm).

Figure 12b shows the resilience and apparent toughness for each girder assembly. The results indicate that VN girders dissipate energy through the material’s inelastic capacity before failure, whereas VE girders display a more limited response. For the VN assembly, the elastic load–deflection behavior ends at 3.29 kN (corresponding to a midspan deflection of 11.7 mm), while the VE girders reach only 1.18 kN at the same deflection. Thus, within the elastic range, VN girders can sustain 2.79 times more load than VE girders, demonstrating greater elastic resilience under service conditions and higher load capacity per unit area in construction applications.

Two approximate energy-based parameters were defined from the applied load–midspan deflection diagram, as indicated in Equations (2) and (3):

For the VN girder assembly, the apparent resilience (Equation (2)) was approximately 19.24 kN·mm. In the inelastic range, the maximum deflection reached 52.2 mm under a load of 6.90 kN, yielding an apparent toughness (Equation (3)) of 257.1 kN·mm. By contrast, the VE girder assembly exhibited an apparent resilience of 7.0 kN·mm and an apparent toughness of 131.1 kN·mm.

This indicates that a TSPA girder constructed with the VN assembly option can dissipate approximately 1.96 times more mechanically induced energy than a TSPA girder built with the VE assembly option under vertical overload conditions.

For the TSPA girder in the present research, ductility can be defined either as the ratio between inelastic and elastic midspan displacements (fixed at 4.5 for both cases) or as the ratio between apparent toughness and resilience. The results for both VN and VE assemblies are presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

Elastic, inelastic, and apparent ductility for the VN and VE girder assemblies.

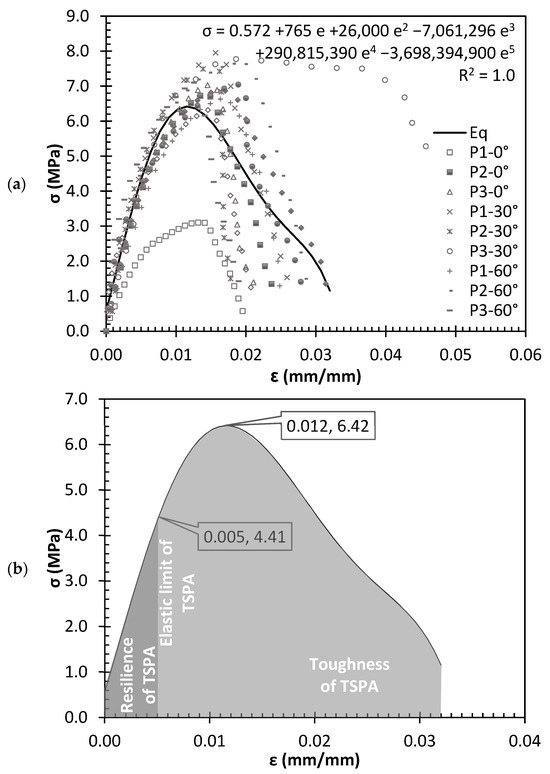

6.4. Comparison of Performance with Previous Studies

A data fit was previously performed using the least squares method (LSM) on 600 data points from 15 tension tests, adapting the ASTM E8 standard as reported by Fuentes [20], to obtain the first approximated stress–strain curve for TSPA. The fitted curve is presented in Figure 13a. Similarly, Figure 13b illustrates the resilience and toughness of TSPA within the context of the stress–strain curve, directly reflecting the mechanical response of the material as detailed by Fuentes [20].

Figure 13.

(a) Approximated stress–strain diagram (σ vs. ε) for TSPA (data from Fuentes [17]). (b) Equivalent σ vs. ε curve of TSPA for the calculation of elastic, inelastic, and ductility properties of TSPA.

Table 6 presents the elastic, inelastic, and ductility properties of TSPA, calculated from tensile test data [17]. These properties are compared with those of the VN and VE girder assemblies.

Table 6.

Elastic, inelastic, and ductility properties of TSPA.

Based on the elastic properties, the TSPA’s resilience is approximately 0.013 MPa·(mm/mm), while its apparent toughness, based on inelastic properties, is 0.133 MPa·(mm/mm). The ductility based on energy dissipation is 10.1, and the ductility based on unit strain is approximately 6.3. This behavior also happens at the material stress–strain level.

The ratio between the apparent resilience of the VN girder assembly and that of the VE girder assembly is 2.74, while the ratio between the apparent toughness of the VN girder assembly and that of the VE girder assembly is 1.96. This means that the new proposed assembly has a greater capacity of controlling elastic demand for service conditions, and a larger capacity to withstand overload scenarios before collapse. Thus, this shows the increased bending capacity using a larger amount of TSPA, which ultimately means a greater use of solid waste to improve the mechanical capacity of this flooring system (see Table 2—%kg of TSPA material).

7. Solid Waste Use per Flooring System and Its Approximated CO2-Equivalent Footprint

Option 1 was selected as the girder assembly candidate for the full-scale tests, as numerical approximations suggested enhanced structural performance compared to the previously used girders.

Constructing a complete VN girder requires approximately 100 kg of TSPA (see Table 2). On average, producing 1 kg of TSPA requires about 30.3 standard Tetra Pak® containers, according to the industrial process implemented by a Colombian transformer company [6]. As with any industrial process, this number may vary due to differences in container density or fluctuations in TSPA sheet thickness during production.

Producing 1 kg of TSPA requires the consumption of natural gas, electricity, and water, as summarized in Table 7.

Table 7.

Raw materials involved during the fabrication and assembly of 1kg of TSPA according to [18].

In other words, a single VN girder assembly requires approximately 3030 recycled Tetra Pak containers. Considering that a flooring system (see Figure 1) consists of four VN girders (V-01, V-02) and at least two additional girders equivalent to the four VT-01 joists, a complete TSPA flooring system would therefore reuse about 18,200 1L Tetra Pak containers. This estimate does not include the additional containers required for the connections and columns of a full housing system.

For a VN girder, an estimated 600 kg of TSPA is required for a complete flooring system, along with approximately 6.2 kg of 38 mm long steel screws. The total carbon footprint of 1 kg of a TSPA VN girder is determined by summing the footprint of the original Tetra Pak container [37,38], the footprint associated with the TSPA transformation process, and the footprint of all prefabrication activities. The latter is mainly influenced by the use of steel screws, with an estimated emission factor of 2.3 kg CO2 per kg of steel [39], as expressed in Equation (4):

Substituting the values, the total is as follows:

Kg-CO2.Eq = 0.0016 kg-CO2/Kg of Tetra Pak + 0.143 kg-CO2/Kg of TSPA + 0.023 kg-CO2/Kg of assembly = 0.1676 per kilogram of TSPA, including transformation and VN assembly. Thus, for 600 kg of TSPA, the carbon footprint of a VN-girder-based system, for a 14 m2 architectural footprint, is approximately 100.56 Kg of CO2. Thus, this means an index of 7.18 Kg-CO2 Eq. per square meter of TSPA flooring.

For comparison, a sustainable concrete mixture incorporating recycled aggregates has an estimated carbon footprint between 620 and 800 kg-CO2-Eq. per cubic meter of concrete [40]. Considering that the average density of concrete is approximately 2400 kg/m3, this corresponds to a carbon footprint in the range of 0.26–0.33 kg-CO2·Eq. per kilogram of sustainable concrete [40].

The flooring system developed in this research, manufactured from solid waste, i.e., recycled Tetra Pak containers, provides not only a sustainable alternative material for housing applications but also a second-life use for containers that would otherwise end up in landfills if not properly managed. Moreover, this solution achieves a carbon footprint equivalent to 56.8% of that of a reference sustainable concrete and only 7.3% of that of steel, when compared on a per-kilogram basis.

8. Conclusions

This study evaluated a new set of bending-resistant structural elements with hollow cross-sections made of TSPA, aligning with the growing trend of using recycled solid materials to develop innovative construction products. The results demonstrate that these elements are capable of controlling deflections and providing enhanced bending resistance compared to the structural components previously employed in housing systems built from recycled Tetra Pak containers.

The proposed VN girder assembly configuration reduces deflections in the elastic range by 61% and increases resistance to vertical loads by 287% compared to the previous VE configuration. This represents a significant functional and mechanical improvement, achieved without increasing the overall dimensions or material weight of the girders. From a sustainability perspective, the VN configuration eliminates the need for additional steel continuity plates and instead employs eight 19 mm structural bolts (see Figure 1), thereby lowering the overall carbon footprint of the flooring system. Moreover, the lightweight nature of the solution can contribute to reduced emissions during construction by minimizing reliance on heavy lifting machinery.

The observed failure mechanism was attributed to cracking within the plastic matrix of the TSPA. This process results from stress accumulation that induces permanent dislocations in the material’s microstructure. As the crack tip advances, propagation leads to the formation of a complete fracture zone within the material.

TSPA girders demonstrated apparent toughness, as they were able to continue carrying load even after cracks developed in the web. This behavior highlights the material’s capacity to resist crack propagation, enabling the beams to sustain load without experiencing sudden failure. As a future line of research, it is recommended to investigate this behavior under environmental influences that could accelerate crack formation or reduce the apparent toughness of TSPA when subjected to service loads in flooring systems.

The coefficients of variation (CoV) for TSPA sheet thicknesses ranged between 3.9% and 10.4% (Table 1). Likewise, the modulus of elasticity presented a CoV of 32%, suggesting the need for continued material research and industrial standardization. These findings emphasize the importance of strengthening quality control protocols during the sheet manufacturing process to ensure greater mechanical reliability and consistency.

Information on assembly alternatives is scarce in the literature, as the structural application of TSPA has not yet been explored at a state-of-the-art level. The solution proposed in this study demonstrates potential for mitigating excessive deflections; however, further research is required, particularly through testing a larger number of specimens under controlled laboratory conditions. Future work should also consider the implementation of additional control strategies—such as post-tensioning systems—to further reduce the residual deflections observed in the full-scale tests (Figure 10 and Figure 11) and to limit crack initiation at the locations identified both numerically and experimentally in the VN girders.

The construction of a single flooring system, such as the one illustrated in Figure 1, provides a second-life use for approximately 18,200 Tetra Pak containers that would otherwise be considered solid waste. The findings presented herein highlight the potential to create a structural application for these containers, achieving a solution that represents only 56.8% of the CO2 equivalent of a reference sustainable concrete alternative and 7.3% of the CO2 equivalent of steel products, in terms of unit mass.

The construction of a single flooring system, such as the one illustrated in Figure 1, provides a second-life use for approximately 18,200 Tetra Pak containers that would otherwise be discarded as solid waste. The findings presented herein highlight the potential to create a structural application for these containers, achieving a solution that represents only 56.8% of the CO2 equivalent of a reference sustainable concrete alternative and 7.3% of the CO2 equivalent of steel products, in terms of unit mass. Beyond its technical merits, this approach contributes to the principles of the circular economy by transforming post-consumer packaging waste into durable structural elements. In doing so, it closes a material loop that traditionally ends in landfill disposal, offering both an environmentally responsible solution and a novel pathway for sustainable construction.

9. Patents

The present research is covered under the patent disclosure in Colombia, under register code NC 2019/0012797, and also under a patent disclosure in Chile under register code No 69.063.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: F.N.-M., S.A.-V., and H.P.-S.; Methodology: F.N.-M. and S.A.-V.; Software: S.A.-V. and H.P.-S.; Validation: F.N.-M. and S.A.-V.; Formal Analysis: S.A.-V., H.P.-S., and C.G.-Q.; Investigation: S.A.-V. and H.P.-S.; Resources: F.N.-M. and S.A.-V.; Data Curation: Y.A.A., S.A.-V., H.P.-S., and C.G.-Q.; Writing—Original Draft: S.A.-V. and H.P.-S.; Writing—Review and Editing: F.N.-M., Y.A.A., and C.G.-Q.; Visualization: S.A.-V.; Supervision: F.N.-M. and Y.A.A.; Project Administration: F.N.-M. and Y.A.A.; Funding Acquisition: F.N.-M. and Y.A.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded as a joint effort by Pontificia Universidad Javeriana, the National Business Association of Colombia (Visión Circular-ANDI), the Tetra Pak multinational packaging solutions company and its subsidiary in Colombia, and the ATENEA Agency of the city of Bogotá, grant no. 00010572. The authors also acknowledge the proof-of-concept grant from the Vice-Rector’s Office for Research at Pontificia Universidad Javeriana, awarded in 2021 and 2022, and direct funding from the university’s engineering laboratory.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data are available upon request.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Tetra Pak Andina for their generous material donation, and the Structures Laboratory of Pontificia Universidad Javeriana, Bogotá, Colombia, for their invaluable technical assistance. The authors confirm that AI-assisted technologies were used in the preparation of this manuscript. The Gemini language model was used as a writing and translation assistant to improve the clarity, grammar, and overall professional tone of the text. This tool was specifically used to translate certain sections and to refine the English-language phrasing to ensure the manuscript adhered to standard academic writing conventions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- DANE and Departamento Nacional de Estadística. Boletín Técnico Déficit Habitacional. 2021. Available online: https://www.dane.gov.co/index.php/estadisticas-por-tema/demografia-y-poblacion/deficit-habitacional (accessed on 15 May 2024).

- Asobancaria. Informalidad en la Vivienda y Propuestas de Solución. Edición 1317. 21 February 2022. Available online: https://www.asobancaria.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/1317_BE.pdf (accessed on 18 April 2023).

- ONU. Las Emisiones Históricas del Sector de la Construcción, lo Alejan de Los Objetivos de Descarbonización. Available online: https://news.un.org/es/story/2022/11/1516722 (accessed on 18 April 2023).

- Pérez Roas, J.A. Riesgo climático y definición de estrategias financieras para su mitigación en el sector Agua y Saneamiento en ALC: Metodología Para Priorizar y Dimensionar las Inversiones en Medidas de Adaptación y Mitigación al Cambio Climático. 2020. Available online: https://publications.iadb.org/es/riesgo-climatico-y-estrategias-financieras-para-su-mitigacion-en-el-sector-agua-y-saneamiento-en (accessed on 18 April 2023).

- Betancourt-García, H.E. Plan de Negocios Para la Creación de Una Planta de Procesamiento de Envases Usados y Desechos Posindustriales de Tetrapak, Para la Producción de Láminas Aglomeradas de Tektan. Bachelor’s Thesis, Pontificia Universidad Javeriana, Bogotá, Colombia, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RIORION LTDA. Características Técnicas Láminas Ecoplak; RIORION LTDA: Bogotá, Colombia, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Innovative Eco-Friendly Housing: Homes Made from Recycled Plastic|Plastics for Change. Available online: https://www.plasticsforchange.org/blog/we-built-houses-made-out-of-plastic-waste (accessed on 18 August 2025).

- Milad, A. Recycled and upcycled materials in contemporary architecture and civil engineering: Their applications, benefits, and challenges. Clean. Waste Syst. 2025, 10, 100203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesquisa Javeriana. Una Casa Construida Con Envases Tetra Pak Que Desafía Los Terremotos Más Poderosos. 64. Bogotá, Colombia. July 2023, pp. 20–22. Available online: https://www.javeriana.edu.co/pesquisa/casa-tetra-pak-terremoto/ (accessed on 15 May 2024).

- Chen, L.; Yang, M.; Chen, Z.; Xie, Z.; Huang, L.; Osman, A.I.; Farghali, M.; Sandanayake, M.; Liu, E.; Ahn, Y.H.; et al. Conversion of waste into sustainable construction materials: A review of recent developments and prospects. Mater. Today Sustain. 2024, 27, 100930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fantuzzi, N.; Vidwans, A.; Dib, A.; Trovalusci, P.; Agnelli, J.; Pierattini, A. Flexural characterization of a novel recycled-based polymer blend for structural applications. Structures 2023, 57, 104966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, J.; Gomez-Lanier, L. Are Tiny Homes Here to Stay? A Review of Literature on the Tiny House Movement. Fam. Consum. Sci. Res. J. 2017, 45, 394–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brokenshire, S. Tiny houses desirable or disruptive? Aust. Plan. 2018, 55, 226–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Guevara Sánchez, C.; Mavrogianni, A.; Neila González, F.J. On the minimal thermal habitability conditions in low income dwellings in Spain for a new definition of fuel poverty. Build. Environ. 2017, 114, 344–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, M.T.; Wonodihardjo, A.S. Achieving Sustainability of Traditional Wooden Houses in Indonesia by Utilization of Cost-Efficient Waste-Wood Composite. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abera, Y.A. Sustainable building materials: A comprehensive study on eco-friendly alternatives for construction. Compos. Adv. Mater. 2024, 33, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuraida, S.; Dewancker, B.; Margono, R.B. Application of non-degradable waste as building material for low-cost housing. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 6390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintero, M.; Rodríguez, P.; Rubio, J.; Jaramillo, L.; Nuñez-Moreno, F. Caracterización de la flexión y compresión de elementos estructurales huecos fabricados con láminas de Tetra Pak® reciclado y cálculo aproximado de la huella de carbono producida en su elaboración. Rev. Ing. De Construcción 2017, 32, 131–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM E8; Standard Test Methods for Tension Testing of Metallic Materials. ASTM: Conshohocken, PA, USA, 1924. Available online: https://compass.astm.org/document/?contentCode=ASTM%7CE0008_E0008M-22%7Cen-US (accessed on 23 February 2024).

- Fuentes, J. Caracterización Experimental De La Respuesta Estructural De Conexiones A Cortante Viga-Columna Fabricadas Con Material Aglomerado De Tetra Pak Ante La Acción De Cargas Cíclicas. Master’s Thesis, Pontificia Universidad Javeriana, Bogotá, Colombia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Molano, A.; Gutierrez, C. Estudio de la Viabilidad Técnica y Financiera de un Macro Proyecto de Vivienda Aplicando la Propuesta de C.E.S® en un Proyecto de Control. Bachelor’s Thesis, Pontificia Universidad Javeriana, Bogotá, Colombia, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Nuñez-Moreno, F.; Alvarado-Vargas, Y. Natural-Sized Proof of Concept for the Prefabricated Construction System Made with Termo-Stiffened Polimeric-Aluminum (TSPA) Sheets (Internal Document); Vicerretor’s Office for Research, Pontificia Universidad Javeriana: Bogotá, Colombia, 31 December 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Nuñez-Moreno, F.; Ruiz, D.M.; Aristizabal-Vargas, S.; Gutierrez-Quintero, C.; Alvarado, Y.A. Seismic Performance of a Full-Scale Moment-Frame Housing System Constructed with Recycled Tetra Pak (Thermo-Stiffened Polymeric Aluminum Composite). Buildings 2025, 15, 813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM C78-22; Standard Test Method for Flexural Strength of Concrete (Using Simple Beam with Third-Point Loading). ASTM International: Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2022.

- Rodrigo, J.A. Ajuste y Selección de Distribuciones con Python. Available online: https://www.cienciadedatos.net (accessed on 28 March 2023).

- Li, L.; Xiang, J.; Liu, S.; Li, J.; Long, H.; Xue, Y. Uncertainty Optimization of Industrial Production Operations Considering the Stochastic Performance of Control Loops. Processes 2025, 13, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhou, A.; Zhao, L.; Chui, Y.H. Mechanical properties of wood columns with rectangular hollow cross section. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 214, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campione, G.; Carlea, D. Excessive Deflection in Long-Span Timber Beams of a Historical Building in the South of Italy: Analysis and Retrofitting Design. J. Perform. Constr. Facil. 2020, 34, 04020039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, W.; Fernando, D.; Heitzmann, M.; Gattas, J.M. Manufacture and structural performance of modular hybrid FRP-timber thin-walled columns. Compos. Struct. 2021, 260, 113506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gattas, J.M.; O’Dwyer, M.L.; Heitzmann, M.T.; Fernando, D.; Teng, J.G. Folded hybrid FRP-timber sections: Concept, geometric design and experimental behaviour. Thin-Walled Struct. 2018, 122, 182–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, J. Design of regular and shear-reinforced panel web beams for long-span construction. Eng. Struct. 2014, 76, 187–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karagiannis, V.; Málaga-Chuquitaype, C.; Elghazouli, A.Y. Behaviour of hybrid timber beam-to-tubular steel column moment connections. Eng. Struct. 2017, 131, 243–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böl, M.; Reese, S. Finite element modelling of rubber-like polymers based on chain statistics. Int. J. Solids Struct. 2006, 43, 2–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, B.-T.; Gencturk, B.; Belarbi, A.; Poudel, P. Nonlinear Finite-Element Modeling of Concrete Bridge Girders Prestressed with Carbon Fiber–Reinforced Polymers. J. Bridge Eng. 2024, 29, 04024058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bin Azuwa, S.; Bin Mat Yahaya, F. Experimental investigation and finite element analysis of reinforced concrete beams strengthened by fibre reinforced polymer composite materials: A review. Alex. Eng. J. 2024, 99, 137–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM A36-19; Standard Specification for Carbon Structural Steel. ASTM International: Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2019.

- Quintero, M.; Rodríguez, P. Caracterización Mecánica A Flexión Y Compresión De Elementos Cajón Armados Con Láminas Aglomeradas De Tetra Pak® Considerando Los Beneficios Ambientales De Su Uso Potencial. Bachelor’s Thesis, Pontificia Universidad Javeriana, Bogotá, Colombia, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tetra Pak. Sustainability Report FY24; Tetra Pak: Quarry Bay, Hong Kong, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Song, X.; Du, S.; Deng, C.; Shen, P.; Xie, M.; Zhao, C.; Chen, C.; Liu, X. Carbon emissions in China’s steel industry from a life cycle perspective: Carbon footprint insights. J. Environ. Sci. 2025, 148, 650–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanagaraj, B.; Anand, N.; Alengaram, U.J.; Raj, R.S.; Lubloy, E. A comprehensive review on life-cycle assessment of concrete using industrial by-products. Case Stud. Chem. Environ. Eng. 2025, 12, 101260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).