Abstract

Coal fly ash (CFA) is a promising secondary resource for rare earth element (REE) recovery. This study characterized CFA using XRF, SEM-EDS, ICP-MS, and XRD, revealing critical REE concentrations of 26.3 ppm (Nd), 4.84 ppm (Dy), 2.89 ppm (Er), 1.69 ppm (Eu), and 0.85 ppm (Tb). REEs are distributed in Al-Si-Mg-Ca-rich aluminosilicates, except Dy, which is associated with Fe-rich phases. Leaching optimization using response surface methodology (RSM) with a central composite design (CCD) identified optimal conditions at 59.5% HCl:40.5% citric acid, 85 °C, and 720 min, achieving recoveries of 94.8% (Dy), 85.2% (Er), 73.1% (Eu), 79.1% (Nd), and 85.7% (Tb). These conditions provided the best balance between recovery, acid use, and selectivity, demonstrating potential scalability for industrial applications. The quadratic model accurately predicted REE recoveries, with accuracies of 95.61% (Dy), 97.76% (Er), 97.30% (Eu), 99.07% (Nd), and 99.17% (Tb). Thermodynamic analysis showed that mineral dissolution influenced REE selectivity, with anorthite (ΔG358K = −348.1 kJ·mol−1) dissolving readily, while ankerite (ΔG358K = 5.49 × 106 kJ·mol−1) contributed to high selectivity, particularly for Mg. Element selectivity followed Mg > Al > Si > Fe ≥ Ca, indicating Mg- and Al-bearing phases were more susceptible, while Fe- and Ca-bearing minerals remained more resistant under mixed-acid conditions.

1. Introduction

The International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) defines rare earth elements (REEs) as the group of fifteen elements from the lanthanide series in the periodic table, including lanthanum (La), cerium (Ce), praseodymium (Pr), neodymium (Nd), promethium (Pm), samarium (Sm), europium (Eu), gadolinium (Gd), terbium (Tb), dysprosium (Dy), holmium (Ho), erbium (Er), thulium (Tm), ytterbium (Yb), and lutetium (Lu). In addition to these, yttrium (Y) and scandium (Sc) are also considered as rare earth elements [1]. REEs and their alloys are indispensable, especially in various sectors including manufacturing, transportation, agriculture, construction, and energy generation. More recently, REEs and their compounds have become essential components of renewable energy and clean storage technologies like electric vehicles and wind turbines, which are essential for climate change mitigation strategies globally [2]. For example, a typical 3 MW wind turbine requires 2 tonnes of REEs in addition to 4.7 tonnes of copper, 3 tonnes of aluminum and substantial amounts of molybdenum and zinc [3]. Because of this, the demand for REEs is forecasted to grow by 5–9% over the next 25 years. However, there are supply security concerns, and REE global supply is projected to fall short by approximately 3000 tonnes each year [4,5,6]. These could be attributed to the social and environmental challenges of mine development, availability of REE-bearing ores, and economic constraints and issues like trade and permitting restrictions [7,8,9]. Thus, it becomes imperative to identify alternative sources to cater to the global demand for REEs.

In recent years, coal fly ash (CFA), a byproduct of coal-fired power plants, has been increasingly recognized as a potential source of REEs. The global production volume of CFA is approximately 380.5 million tonnes in 2022, with projections reaching 475.4 million tonnes by 2028 [10]. In the Philippines, there is a significant accumulation of coal fly ash, reportedly reaching approximately 2.78 MT, with projections suggesting it may rise to nearly 13.02 MT by 2035 [11]. The bulk of CFA, around 75%, ends up in landfills, with only about 25% being repurposed [12,13,14,15]. Numerous studies have reported about the REE contents of CFAs, revealing that they generally contain between 400 and 600 ppm of REEs, which is about three times higher than conventional REE ores [15,16,17,18,19]. Most notably, a significant fraction, approximately 34–38%, of REEs found in CFA consist of critical elements like Nd, Eu, Tb, Dy, Y, and Er [17]. These previous works highlighted that CFA could be a potential alternative source of REEs. Meanwhile, coal accounted for approximately 26% of global primary energy consumption in 2023, maintaining its position as a significant energy source despite the increasing adoption of renewables. Furthermore, the contribution of coal to global electricity generation remained substantial, comprising 35.6% in 2023 [20]. This suggests that CFA generation is poised to increase in line with growing electricity demand. By harnessing REEs from CFA, circular economy concepts are championed and two global challenges are addressed, that is, meeting the increasing demand for REEs and sustainably managing the negative environmental impacts of CFAs.

Numerous studies have reported the potential extraction and recovery of REEs from CFAs and related coal materials [19]. Earlier investigations have explored approaches such as physical separation and chemical treatment in addition to leaching. For example, Pan et al. [21] reported ~80% leaching efficiency when acid leaching was applied to a physically pre-concentrated fraction, and Taggart et al. [22] showed that NaOH roasting prior to acid leaching raised the leachable REE fraction to ~80–90%. A prevalent finding among these previous works is that leaching stands out as the most effective method for REE recovery from CFA. Leaching is a chemical process wherein soluble target elements, such as REEs, are dissolved and extracted from samples using a specific solvent or lixiviant [21,22,23,24,25,26]. Hydrochloric acid (HCl) has been identified as an effective lixiviant, consistently yielding high REE extraction rates. However, the use of HCl presents challenges due to its highly corrosive nature and relatively high cost compared to other acids [23]. Exploring alternative lixiviants, Prihutami et al. [25] investigated the effectiveness of citric acid (C6H8O7) using the magnetic fraction of CFA under conditions of 0.5–2.0 M citric acid, a 1:10 solid–liquid ratio, 4 h leaching, and temperatures up to 90 °C. They found that temperature had a stronger effect on extraction than acid concentration, with citric acid yielding moderate REE recoveries (generally ~45%), but still outperforming acetic acid and showing potential as a more environmentally friendly lixiviant. Further substantiating the potential of citric acid, Ji et al. [27] showed that under identical leaching conditions (0.05 mol/L lixiviant, pH 3.0, 75 °C, 2 h, and S/L = 1:10), citric acid achieved higher REE recoveries than HCl leaching at ~65% of LREEs and ~32% of HREEs, compared with only ~45% and ~20% for HCl, respectively. This superior performance could be attributed to the dual role that citric acid plays during the leaching process. First, protons (H+) directly attack and solubilize mineral phases, and second, citrate forms stable complexes with metal ions, not only stabilizing dissolved metal ions but also freeing additional H+ for leaching [28]. Based on these previous findings, it is compelling to consider the synergistic potential of combining citric acid, as a citrate source, with hydrochloric acid, as a proton source, for even more efficient REE extraction from CFA.

The Philippines has seen a significant accumulation of coal fly ash, reportedly reaching approximately 2.78 MT, with projections suggesting it may rise to nearly 13.02 MT by 2035 [29]. Despite this growing volume, CFA remains largely unutilized, posing environmental and management challenges. Few studies have explored its REE recovery potential, leaving a gap in understanding its composition, extractability, and valorization prospects. Addressing this gap is vital to transform CFA from an environmental burden into a value-added secondary resource that advances the country’s circular economy and resource security goals. Building on this context, Dahan et al. [23] provided an important foundation by presenting one of the first systematic assessments of REE extraction from Philippine CFA using HCl. Through response surface methodology (RSM), they identified HCl concentration, temperature, and leaching time as critical variables influencing the extraction efficiency, with optimal conditions (3 M HCl, 65 °C, and 270 min) yielding up to 70–90% recovery for selected REEs. However, their work was limited to a single-acid system and did not explore alternative or mixed-acid approaches that could address known limitations of HCl leaching, such as its high corrosivity, reagent cost, and silica-gel formation in CFA with substantial amorphous content. This research aims to optimize the leaching of CFA using a combination of mineral and organic acids, building on the work of Ranay et al. [30], and to compare the effectiveness of HCl leaching, as described in the study by Dahan et al. [23], with a combined approach using citric acid and HCl. To support this objective, Philippine CFA was comprehensively characterized using ICP-MS, XRD, SEM-EDS, and XRF to establish its elemental composition, mineral phases, and morphological attributes. A systematic evaluation of leaching temperature, leaching time, and acid ratio was subsequently performed through central composite design (CCD) integrated with RSM to develop predictive models and determine optimal extraction conditions. By benchmarking the mixed-acid system against pure HCl and pure citric acid leaching, this study offers a novel and potentially more sustainable pathway for enhancing REE extraction efficiency from CFA.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Equipment

The CFA used in this study was sourced from a 200-megawatt circulating fluidized bed combustion (CFBC) coal-fired power plant. Sample collection was performed using grab sampling and a Jones riffle. A 20 kg sack of CFA was systematically split using the Jones riffle until a representative 2 kg sample was obtained. The sample was sieved through a 200-mesh (75 µm) sieve. The finer fraction was further grab-sampled to obtain 5 g portions, which were stored in hinged, sealed containers for the leaching experiment and analysis.

Characterization techniques included XRF (Bruker S8 TIGER Series 2, Bruker Corporation, Karlsruhe, Germany) for bulk chemical composition, conducted at Intertek Testing Services Philippines’ Minerals Laboratory. Trace element analysis of both CFA and leachates was performed using ICP-MS (Agilent 7700, Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) at Intertek’s laboratory (±2% margin of error). Morphological analysis was conducted using SEM-EDS (JEOL JSM-5310, JEOL Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) equipped with an AMETEK/EDAX Element EDS system (EDAX/AMETEK, Berwyn, PA, USA) at De La Salle University’s Central Instrumentation Facility. Imaging was performed at 1500× and 5000× magnifications under ultrahigh vacuum, using an accelerating voltage of 15 keV; elemental mapping and EDS micrographs were also obtained. Mineralogical composition was determined using XRD (Rigaku SmartLab diffractometer, Rigaku Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) at the DOST-ITDI technical services facility, operating with Cu radiation at 40 kV and 30 mA; the instrument scanned a 2θ range of 2–70° to capture mineral phase data.

2.2. Methods

The selection of lixiviant concentration plays a crucial role in the extraction efficiency of critical REEs. Based on the findings of Dahan et al. [23], a hydrochloric acid (HCl) concentration of 3 M was utilized [3]. Similarly, preliminary scoping experiments identified 0.5 M citric acid (C6H8O7) as the optimal concentration for organic acid leaching. To prepare the 3 M HCl stock solution, 250 mL of concentrated 12 M HCl was diluted with 750 mL of deionized water in a 1 L volumetric flask. The 0.5 M citric acid solution was prepared by dissolving citric acid monohydrate in deionized water and adjusting the final volume to 1 L in a volumetric flask.

The leaching experiments followed the methodology established by Ranay et al. [30]. The experimental setup consisted of a magnetic stirrer, a water bath, a 500 mL beaker, and a thermometer. The leaching temperature was monitored using an integrated thermometer, while continuous mixing of the solid sample with the acid solution was achieved using a magnetic stir bar. To minimize evaporation losses, the beaker was sealed with parafilm. The water bath level was routinely checked to ensure consistent thermal conditions throughout the experiment.

The leaching process was standardized at a solid-to-liquid ratio of 1:10 g mL−1 and a stirring rate of 260 rpm. Following leaching, the suspension was filtered using Whatman filter paper, and the collected filtrate was diluted with an equal volume of 3 M HCl. The solid residue retained on the filter paper was oven-dried at 105 °C for 48 h. To ensure reproducibility and reliability, each experimental condition was performed in triplicate. The concentrations of critical REEs and major elements (Si, Fe, Al, Ca, and Mg) in the leachate were quantified using Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS). The leaching recovery percentage and the selectivity ratio were calculated using the following equations:

2.3. Design of Experiment

The experimental design followed a central composite design (CCD) under the response surface methodology (RSM) framework for optimization, as detailed in Table 1. Each variable was evaluated at five levels: ±α (axial points), ±1 (factorial points), and the central point. Table 2 presents the experimental design, which examined the effects of the leaching time, temperature, and acid ratio on the extraction process. Each independent variable was tested at five levels. Statistical analysis was conducted using a three-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) to assess parameter interactions and their significance. The experiment consisted of 18 unique conditions, each performed in triplicate, resulting in a total of 54 runs. A significance threshold of 0.05 was applied in all statistical evaluations.

Table 1.

RSM central composite design experimental independent variables and coded levels.

Table 2.

RSM experimental runs in coded units (X1—acid ratio; X2—temperature; X3—time).

3. Results and Discussion

This section contains a detailed presentation and discussion of the data analysis and the results of this study. The findings are presented under the following major headings: characterization of the coal fly ash; determination of optimum leaching parameters using RSM-CCD; and selectivity of mixed mineral–organic acid with respect to the extraction of major elements Si, Al, Ca, Fe, and Mg. This study is focused on the recovery of critical REEs, particularly Nd, Dy, Er, Eu, and Tb. The discussion centers on the main determining factor response, which is the leaching recovery (or % leaching efficiency or % leaching extraction) of the critical REE, as the acid ratio, temperature, and time were varied.

3.1. Characterization of the Coal Fly Ash

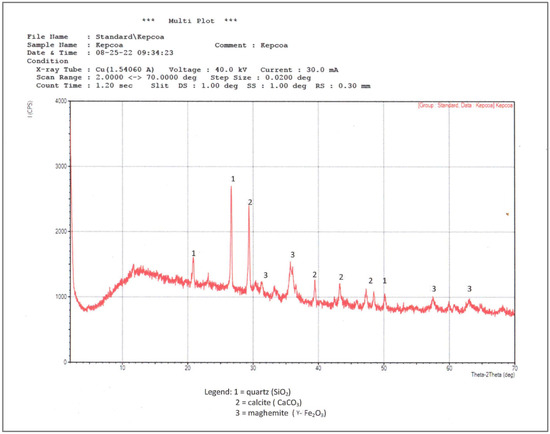

The major crystalline phases identified in the CFA by XRD are quartz (SiO2), calcite (CaCO3), and maghemite (γ-Fe2O3), as shown in Figure 1. Quartz exhibited prominent reflections at 2θ = 20.8° and 26.6°, consistent with its thermal stability at combustion temperatures [31]. Calcite shows its main peak at 29.3°, while maghemite is identified at 35.5°, indicating the transformation of Fe-bearing precursors such as pyrite during combustion [32]. An amorphous phase, attributed to aluminosilicate glass often modified by Ca2+, Mg2+, Na+, or K+, appears as a broad peak between 2θ ≈ 5° and 25° [25,33].

Figure 1.

X-ray diffractogram of the CFA sample.

The XRF results summarized in Table 3 show silicon (Si), aluminum (Al), calcium (Ca), and iron (Fe), along with minor elements such as barium (Ba), potassium (K), manganese (Mn), sodium (Na), phosphorus (P), and sulfur (S). The chemical composition aligned well with the phases identified by XRD, particularly the dominance of quartz and the presence of Ca- and Fe-bearing minerals such as calcite and maghemite. Although Al2O3 was abundant in XRF, no distinct alumina peaks were detected in the diffractogram because aluminum is primarily hosted in the amorphous aluminosilicate glass phase rather than as crystalline Al2O3. This behavior is typical for coal fly ash, where clay minerals dehydroxylate and melt during combustion, incorporating Al into the glassy matrix [34].

Table 3.

Relative amounts of oxides in coal fly ash samples.

Based on ASTM C618, the coal fly ash (CFA) is classified as Class C due to its high CaO content and the combined SiO2 + Al2O3 + Fe2O3 concentration of 63.2%, which meets the chemical criteria for this category. The same ash source supplies fly and bed ash to a cement corporation for use as additives in cement production. This industrial application confirms that the ash is utilized within a cementitious context, further supporting its classification as a Class C-type fly ash under ASTM C618. Furthermore, the loss on ignition (LOI) of 11.95% exceeds the ASTM limit of 6%, likely due to the presence of carbonate minerals (e.g., calcite and dolomite) and volatile organic residues [35,36,37,38]. Overall, the integrated XRD and XRF results confirm that Si, Al, Ca, and Fe are the principal constituents of the CFA, consistent with earlier reports for CFBC-derived ashes by Dahan et al. [23] and Ranay et al. [30].

The concentration of rare earth elements as well as the major elements in the coal fly ash were determined using ICP-MS analysis. The REE content of the coal fly ash can be categorized to make an evaluation of the REE distribution more relevant to the industry. They can be classified (geochemically) into the following: light earth elements (LREE—La, Ce, Pr, Nd, and Sm), medium (MREE—Eu, Gd, Tb, Dy, and Y), and heavy (HREE—Ho, Er, Tm, Yb, and Lu). However, Seredin and Dai [39] devised a new REE classification that considers the current market trends and is related to the likely supply and demand forecast over the next few years. This classification divides REEs into three groups: critical (Nd, Eu, Tb, Dy, Y and Er), uncritical (La, Pr, Sm, and Gd), and excessive (Ce, Ho, Tm, Yb, and Lu) [34,39]. Table 4 shows the relative abundance of REE major elements in coal fly ash, and the total concentrations according to geochemical and economic classification. A slight discrepancy was observed for Si, which is attributed to the known analytical variability between XRF (oxide basis) and ICP (elemental basis) measurements due to matrix and instrumental effects. As shown, Ce, Y, La, Nd, and Sc are the most abundant REEs in the coal fly ash, ranging from 26 to 59 ppm. Furthermore, Si appears to be the most abundant major element at 17.7 ppm, followed by other elements in this order: Si > Fe > Ca > Al > Mg. Furthermore, the highest concentrations among critical REEs are Nd and Y, La for uncritical REEs, and Ce for excessive REEs. In addition, La, Ce, and Nd are the highest concentrations for LREEs, Y for MREE, and Yb and Er for HREEs. It is noteworthy that the concentration of HREEs is only minimal in comparison to LREEs and MREEs. The total REE content in the CFA sample was 195 ppm, lower than the commonly reported 400–600 ppm range in global studies. This difference may be attributed to the coal source, as the Philippines imports most of its coal from Indonesia [40], as well as to differences in combustion technology (CFBC) and ash-handling conditions. In addition, the outlook coefficient index (Coutlook) was calculated using the ratio between the total relative amounts of critical REEs and excessive REEs. The Coutlook is 1.05, which falls under Area II of the Seredin and Dai classification, 0.7 ≤ Coutlook ≤ 1.9 and 30% ≤ critical REE ≤ 51%, categorizing the coal fly ash used in this study as promising for economic development.

Table 4.

Concentration of critical REEs and major elements in the coal fly ash.

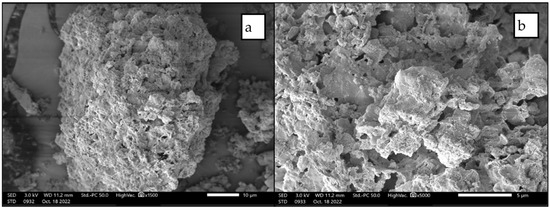

The morphology of the CFA was evaluated using SEM-EDS (Figure 2). From the SEM image, CFA particles appear to be irregularly shaped, porous particles with sizes ranging from <1 μm to 100 μm, and multiple particles (<10 μm) attached to surfaces to form agglomerates. The variety of irregularly shaped porous particles signifies a significant content of unburnt carbon material on the surface of the coal fly ash [13]. This agrees with the XRF result, with a high LOI value of 11.95% (Table 3). In addition, the agglomerated particles could be amorphous particles that underwent inter-particle contact due to rapid cooling after the combustion process of coal [41]. These are cryptocrystalline aluminosilicates, which were identified by many studies before [13,23,42].

Figure 2.

SEM photomicrograph of a coal fly ash sample at (a) 1500× magnification and (b) 5000× magnification.

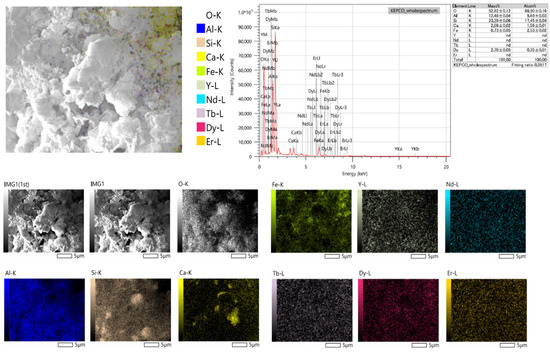

Investigating the SEM-EDS elemental map of the CFA (Figure 3), Al and Si concentrations are high. This is also a confirmation of the dominant presence of aluminosilicates in CFA. Additionally, most Fe does not coincide with oxygen. This could mean that a high concentration of Fe mineral is not in the form of Fe oxides. As for the distribution of REEs in the CFA, REE-bearing particles are found throughout the matrix. Critical REEs are evenly distributed throughout the Al-Si-Mg-Ca-rich aluminosilicates, except for Dy which seemed to be closely associated with the Fe-rich particles, concurring with previous findings [18,23].

Figure 3.

SEM-EDS image at 5000× magnification with elemental map and point analysis.

3.2. Optimization of Leaching Parameters

Prior to optimization experiments, the screening result is analyzed to determine the levels of parameters for the RSM optimization. This section then discusses the fit summary of the data, the ANOVA and general statics for the creation of an empirical model, and the diagnostics to confirm a normal distribution in the experiment data.

The critical REEs in the leachate samples were analyzed, and the leaching recovery was calculated according to Equation (1), as shown in Table 5. Yttrium (Y) was not detected in the samples at a detection limit of 2 ppm, and was therefore excluded from the response data. As observed, the highest recovery was achieved at the longest leaching time and the highest temperature of 720 min (12 h) and 85 °C, respectively. Conversely, the lowest leaching recovery was obtained at 480 min (8 h) and 62.5% HCl:37.5% citric at the lowest leaching temperature of 18 °C. These data were used and inputted into the Design Expert 12 Software to generate an empirical model for response prediction and to determine the optimized leaching parameters.

Table 5.

Average% recovery of the critical REEs for the RSM experiment.

Table 6 presents the final% recovery actual equation with transformation. The response (REE recovery) was transformed using the recommended transformation provided by Design Expert, which is necessary if the error varies with the magnitude of the response. If not, transformation is recommended within the confidence interval (Stat-Ease, n.d.). As illustrated in the table, all critical REEs except for Eu were transformed using a power function.

Table 6.

Final% recovery actual equation with transformation (X1—acid ratio, X2—temperature, X3—time).

To test the adequacy of the quadratic model, the ANOVA result is evaluated. p-values less than 0.05 are considered significant. From Table 7, the model p-value of <0.0001 implies that the quadratic model is significant. Additionally, almost all model terms are significant except for X1X3, X2X3, and X32 for Dy; X1X2, X1X3, X2X3, and X32 for Er, Nd, and Tb; and X2X3 and X32 for Eu. The Lack of Fit f-value for Nd of 1.10 implies the Lack of Fit is not significant. There is a 38.44% chance that a Lack of Fit F-value this large could occur due to noise. A non-significant Lack of Fit is good—we want the model to fit. In summary, the model for all critical REEs is significant.

Table 7.

ANOVA summary for critical REEs.

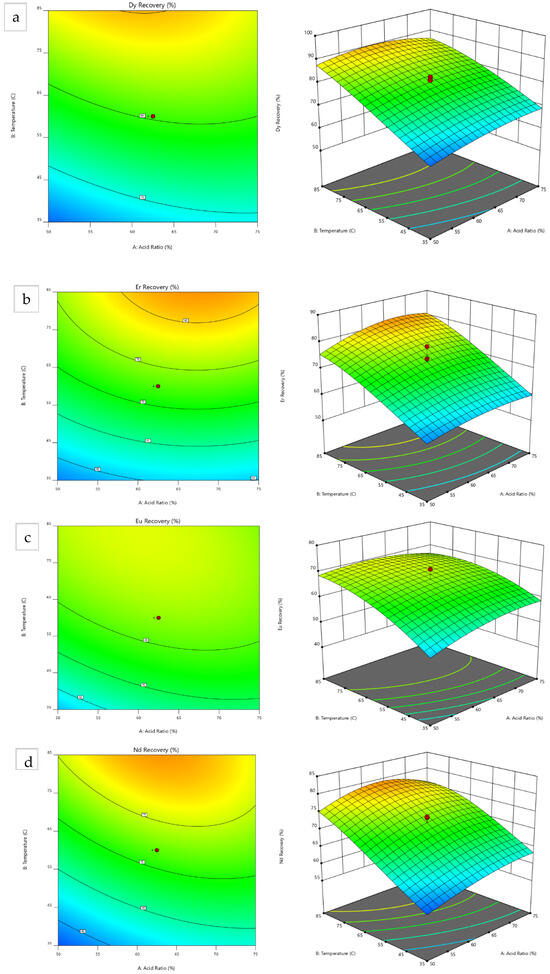

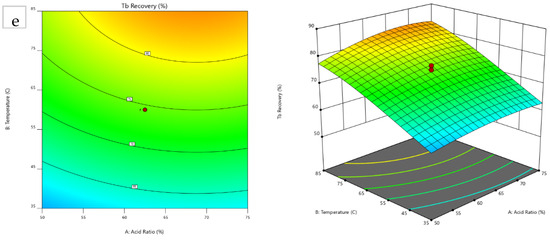

The response surface plots were generated, with the 2D contour plot of the temperature vs. acid ratio and the 3D model graphs illustrated in Figure 4. These visualizations aid in identifying and analyzing the optimal conditions for maximum REE recovery. Most critical REEs exhibit peak recovery at higher temperatures, except for Eu, which shows potential for further improvement with an increase in the temperature upper limit of the experimental range (85–102 °C).

Figure 4.

Contour and 3D model graphs for (a) Dy, (b) Er, (c) Eu, (d) Nd, and (e) Tb.

The accuracy of the empirical models was evaluated by comparing the experimental results with the predicted values under optimal conditions, as summarized in Table 8. For the model to be considered accurate, the percentage error, which is the deviation between the predicted and experimental values, must be less than 5%. The results confirmed that all models exhibited errors below this threshold, indicating that the established models effectively predicted REE extraction with high accuracy.

Table 8.

Comparisons between experimental and predicted results at 75% HCl:25% citric acid, 85 °C, and 240 min.

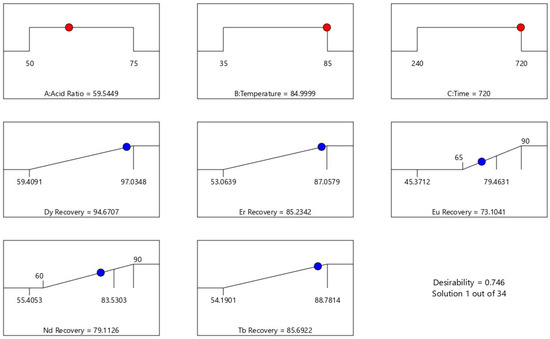

Furthermore, the optimal leaching parameters for maximizing critical REE recovery were determined. The goal of optimization is to identify conditions that satisfy all objectives, with a desirability value approaching 1.0. The optimum leaching conditions (Figure 5) are 59.5% HCl: 40.5% citric acid, 85 °C, and 720 min with a leaching recovery of 94.8%, 85.2%, 73.1%, 79.1%, and 85.7% for Dy, Er, Eu, Nd, and Tb, respectively. The desirability of this condition is 0.746. The selection of these parameters reflects the complementary roles of the two acids: HCl provides strong proton activity and chloride complexation that enhance dissolution of REE-bearing phases, while citric acid chelates REE3+, stabilizing them in solution and often suppressing Fe/Al co-leaching, though the resulting REE–citrate complexes can affect downstream separations and should be considered in flowsheet design [25,28].

Figure 5.

Optimized leaching conditions with the desirability value. The red dot indicates the predicted optimal condition identified by the RSM desirability function, while the blue dots represent experimental runs used to construct the model.

From an industrial perspective, operating temperatures around 80–90 °C are commonly employed in acid leaching of coal fly ash and are therefore realistic for scale-up. The optimized leaching duration of 720 min (12 h), although statistically determined as the best compromise among competing responses, primarily reflects laboratory kinetic equilibrium rather than process throughput limits. Comparable studies have achieved high REE recoveries within 1–3 h at similar temperatures using single-acid systems such as HCl (e.g., 3 M HCl at 65 °C for 270 min, and 1 M HCl at 80 °C) [23]. These findings suggest that while the chosen parameters effectively maximize REE recovery under experimental conditions, further kinetic refinement could reduce the residence time for industrial application without altering the underlying chemistry.

3.3. Leaching Selectivity and Comparison of Direct HCl Leaching vs. Mixed Mineral–Organic Acid Leaching

Selective leaching of valuable metals (from waste materials) offers both economic and environmental advantages by minimizing dissolution, chemical consumption, and waste generation. To achieve a cost-effective leaching process, the lixiviant used for REE extraction must be evaluated for its selectivity. The selectivity coefficient was determined following the method of Elmoaa et al. [43], using Equation (2), comparing the ratio of dissolved valuable metals to major elements in the solution. The primary objective was to assess the preferential dissolution of valuable metals over major elements in coal fly ash.

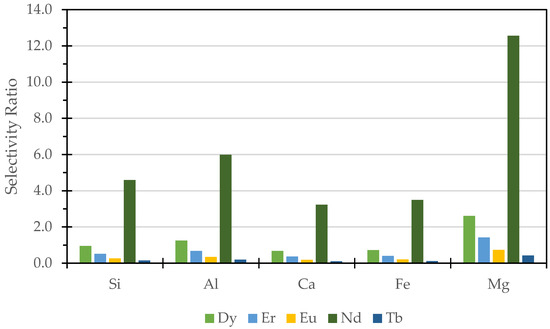

The selectivity ratio, as illustrated in Figure 6, represents the concentration of critical REEs relative to major elements (Si, Al, Ca, Fe, and Mg) under the leaching conditions of 720 min, 85 °C, and 75% HCl:25% citric acid. The purpose of presenting this data is to highlight the preferential dissolution of critical REEs over major elements, which is essential in evaluating the efficiency and selectivity of the leaching process. From the graph, it is evident that Nd exhibits the highest selectivity ratio, particularly with Mg, followed by Al and Si. This suggests that Nd is preferentially leached in the presence of these elements. Meanwhile, Dy, Er, Eu, and Tb show lower selectivity ratios, indicating that their extraction is less favorable under the same conditions. Additionally, the high selectivity ratio of Mg compared to other major elements suggests that Mg may be more susceptible to dissolution under these conditions, potentially influencing the overall recovery. In contrast, Ca and Fe exhibit the lowest selectivity ratio, implying a lower tendency to dissolve, which may indicate that calcium- and iron-bearing minerals in the coal fly ash matrix are more resistant to the mixed mineral–organic acid leaching. Understanding these selectivity trends helps in fine-tuning the lixiviant composition and process conditions to maximize REE recovery while minimizing the unwanted dissolution of major elements, ultimately improving the economic and environmental feasibility of the process.

Figure 6.

Selectivity ratio (concentration of REE/major element) of critical REEs at 720 min, 85 °C, and 75% HCl: 25% citric acid.

To further understand the leaching mechanism, the Gibbs free energy change (ΔG) at 358 K (85 °C) was calculated to determine whether the mixed mineral–organic acid system effectively dissolved the mineral matrix in which these major elements are closely associated. The mineral phases of the coal fly ash used in the calculation of the free energy were identified as aluminosilicate, quartz (), anorthite (), maghemite (), calcite (), and ankerite (), as reported by Ranay et al. [30]. Additionally, the aluminosilicate phase was classified by Dahan et al. [23] to be illite (); thus, this study used the following reactions:

Hydrochloric acid was used to determine the free energy change (ΔG358K) of the reaction, as it is a strong acid capable of facilitating dissolution. The Gibbs free energy values, calculated using the Geochemist Workbench Software and presented in Table 9, indicate that anorthite (ΔG358K = −348.1 kJ·mol−1) dissolves spontaneously, while ankerite (ΔG358K = 5.49 × 106 kJ·mol−1) is reactant-favored, requiring external energy for dissolution. This trend aligns with the selectivity ratio patterns in Figure 6, where Ca, primarily from anorthite and calcite, shows the lowest selectivity ratio due to its high dissolution tendency, whereas Mg, sourced from ankerite and illite, exhibits the highest selectivity ratio since ankerite’s highly positive ΔG358K limits its dissolution. These findings confirm that the thermodynamic favorability of mineral dissolution directly influences the selectivity of REE leaching, with elements from readily dissolvable phases (Ca from anorthite and calcite) showing low selectivity, while those from resistant phases (Mg from ankerite) exhibit high selectivity.

Table 9.

Change in the Gibbs free energy of each mineral phase.

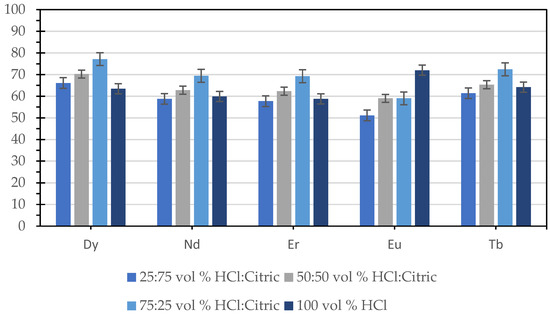

The recovery of critical REEs under identical conditions was compared to evaluate the performance of HCl–citric acid leaching relative to pure HCl leaching. Figure 7 presents this comparison performed at 65 °C for 3 h, using a 1:10 g mL−1 solid-to-liquid ratio and 260 rpm stirring speed. The pure-acid system employed 100 vol% 3 M HCl, while the mixed-acid systems consisted of 75:25, 50:50, and 25:75 vol% HCl:citric acid prepared from 3 M HCl and 0.5 M citric acid solutions. Notably, the 75:25 HCl:citric system yielded higher recoveries for Dy, Nd, Er, and Tb compared with 100 vol% HCl, suggesting a possible synergistic interaction between the inorganic and organic acids. Although direct comparisons between mixed and pure acid systems remain limited, similar enhancements in REE recovery from Philippine coal fly ash using mixed mineral–organic lixiviants were also reported by Ranay et al. [30], supporting the improved leaching efficiency of such systems. The superior performance of the mixed-acid system may be attributed to REE solubilization through citrate complexation and the possible suppression of secondary precipitation, which together stabilize REE3+ ions in solution. While direct evidence of this synergistic mechanism has not been widely reported, our findings are consistent with the general mechanisms described in earlier studies, where organic acids enhance REE leaching via complexation and selective dissolution pathways [44,45,46].

Figure 7.

Recovery of pure HCl leaching vs. mixed mineral–organic acid leaching.

In contrast, the lower Eu recovery observed under mixed-acid conditions could be attributed to the formation of highly stable Eu–citrate complexes, which restrict further dissolution of Eu from the solid phase. Experimental measurements by Neil [47] reported stability constants (log β101) ranging from 7.3 to 8.1 for the 1:1 Eu–citrate complex, confirming the strong affinity of Eu3+ for citrate ligands. Such strong complexation can sequester Eu3+ either as soluble chelates or surface-bound species, thereby limiting its leaching efficiency compared with other REEs. This element-dependent response aligns with existing evidence that REEs exhibit systematic differences in complexation behavior [48]. Moreover, experiments utilizing organic ligands demonstrate significant variation in stability constants and leaching behavior across REEs, underscoring the importance of ligand–metal interactions and process conditions in selective REE recovery [49].

In addition to the observed improvement in critical REE recovery, it is pertinent to consider the potential reuse of the leached fly ash residue. Although this study did not directly assess the mechanical or pozzolanic behavior of the residue, insights from related research provide valuable context. Citric acid pretreatment has been shown to enhance the chemical and mechanical suitability of coal bottom ash for use as a cement replacement. Yahya et al. [50] reported that treated CBA exhibited lower water absorption (≈8–10% at 28 days) compared with the untreated counterpart (≈12%) and higher compressive strength, reaching ≈31 MPa at 28 days for mortar containing 10% treated CBA, closely matching or slightly exceeding the control mix without replacement (≈32 MPa). At higher replacement levels (20–30%), the strength declined, suggesting that moderate substitution optimizes performance while maintaining durability. These findings indicate that citric acid treatment improves ash reactivity by removing deleterious phases and refining surface chemistry, thereby enhancing pozzolanic response and strength development. Classic studies on acid-leached fly ash using mineral acids further demonstrate that leached residues can remain effective pozzolanic additives. Hemmings et al. [51] found that HCl-leached fly ash residues from high-rank coal retained a high silica content and achieved pozzolanic indices exceeding 100% (ASTM C311), fully meeting standard pozzolanic performance criteria, while only low-rank residues exhibited increased water demand. Collectively, these studies support the feasibility of residue valorization when the amorphous Si–Al framework is preserved.

Complementary findings from an independent research group working on the researchers’ leached residue further reinforce this potential. Combining hydrochloric acid-leached fly ash with diatomaceous earth produced a geopolymeric insulating material with favorable physical and thermal properties, achieving a thermal conductivity of 0.344 W m−1 K−1 and a porosity of ≈89%, confirming its suitability for lightweight and insulating construction applications [52]. These results suggest that acid-leached residues retain sufficient aluminosilicate reactivity for non-firing ceramic or alkali-activated binder fabrication. Accordingly, even with partial substitution of HCl by an organic acid such as citric acid, the mixed-acid system is likely to yield a silica- and alumina-rich residue that remains reactive and suitable for similar value-added applications. Taken together, these findings underscore the plausibility that mixed-acid-leached coal fly ash can remain viable for supplementary cementitious, geopolymeric, or backfill uses, consistent with circular resource utilization principles.

4. Conclusions

This study demonstrated the potential of coal fly ash from a circulating fluidized bed coal-fired (CFBC) power plant as a promising source of rare earth elements (REEs). Through comprehensive characterization and optimization, key findings were drawn that address the research objectives and validate the feasibility of REE extraction from this industrial waste material.

The coal fly ash was thoroughly analyzed using XRF, SEM-EDS, and XRD, revealing that SiO2 is the most abundant component, along with significant concentrations of Al2O3, CaO, and Fe2O3. XRD analysis confirmed the presence of mineral phases such as quartz, maghemite, and calcite, as well as non-crystalline aluminosilicates, observed as a hump between 2θ ≈ 5° and 2θ ≈ 25°. Morphological analysis through SEM-EDS indicated that the fly ash particles are porous, ranging from 1 μm to 100 μm, with unburnt carbon observed on the particle surface. Notably, critical REEs were found to be evenly distributed throughout Al-Si-Mg-Ca-rich aluminosilicates, except for Dy, which appeared closely associated with Fe-rich particles. The critical REE head grades were calculated as 26.3 ppm (Nd), 4.84 ppm (Dy), 2.89 ppm (Er), 1.69 ppm (Eu), and 0.85 ppm (Tb). The Coutlook coefficient of 1.05 further categorizes the coal fly ash as a viable candidate for REE extraction.

Leaching optimization was performed using RSM-CCD, suggesting a quadratic model to predict the recovery of critical REEs. The model’s accuracy was statistically validated, achieving accuracy rates of 95.6% for Dy, 97.8% for Er, 97.3% for Eu, 99.1% for Nd, and 99.2% for Tb. The optimum leaching conditions (Figure 5) are 59.5% HCl:40.5% citric acid, 85 °C, and 720 min with a leaching recovery of 94.8%, 85.2%, 73.1%, 79.1%, and 85.7% for Dy, Er, Eu, Nd, and Tb, respectively. Furthermore, the leaching selectivity of the mixed mineral–organic acid was evaluated by determining the selectivity ratio (REE/major element concentration). The dissolution of ankerite was found to have a highly positive ΔG358K (5.49 × 106 kJ·mol−1), while anorthite exhibited a highly negative ΔG358K (−348.1 kJ·mol−1), favoring spontaneous dissolution. This aligns with the selectivity ratio results, where the majority of Ca ions in the leachate originate from anorthite and calcite, leading to a lower selectivity ratio. Conversely, Mg ions primarily come from ankerite and illite, leading to a higher selectivity ratio. As a result, the order of major element selectivity, in relation to REE concentration, was revised to Mg > Fe ≥ Al > Si > Ca.

This study demonstrates that CFBC coal fly ash holds significant potential as a source of REEs, with optimized leaching conditions yielding promising recovery rates. These findings pave the way for sustainable resource utilization and contribute valuable insights to the development of REE recovery strategies from industrial waste, such as coal fly ash, bauxite residue (red mud), metallurgical slags, and spent catalysts.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.L.C.P. and V.J.T.R.; methodology, M.L.C.P.; software, V.J.T.R. and R.D.A.; validation, M.L.C.P., C.B.T., and V.J.T.R.; formal analysis, M.L.C.P.; investigation, M.L.C.P.; resources, V.J.T.R., C.B.T., and R.D.A.; data curation, M.L.C.P.; experiment, M.L.C.P. and K.A.R.; writing—original draft preparation, M.L.C.P.; writing—review and editing, K.A.R., C.B.T., V.J.T.R., and R.D.A.; visualization, M.L.C.P.; supervision, V.J.T.R.; project administration, V.J.T.R.; funding acquisition, V.J.T.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Department of Science and Technology (DOST), Philippines (Grant No. 12-123-24), with additional support from the DOST–Engineering Research and Development for Technology (ERDT) Scholarship Program. The APC was funded by DOST and MSU-IIT.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Balaram, V. Rare earth elements: A review of applications, occurrence, exploration, analysis, recycling, and environmental impact. Geosci. Front. 2019, 10, 1285–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabelin, C.B.; Dallas, J.; Casanova, S.; Pelech, T.; Bournival, G.; Saydam, S.; Canbulat, I. Towards a low-carbon society: A review of lithium resource availability, challenges and innovations in mining, extraction and recycling, and future perspectives. Miner. Eng. 2021, 163, 106743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabelin, C.B.; Park, I.; Phengsaart, T.; Jeon, S.; Villacorte-Tabelin, M.; Alonzo, D.; Yoo, K.; Ito, M.; Hiroyoshi, N. Copper and critical metals production from porphyry ores and e-wastes: A review of resource availability, processing/recycling challenges, socio-environmental aspects, and sustainability issues. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 170, 105610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Dai, S.; Zou, J.; French, D.; Graham, I.T. Rare earth elements and yttrium in coal ash from the Luzhou power plant in Sichuan, Southwest China: Concentration, characterization and optimized extraction. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2019, 203, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, J.; Vaziri Hassas, B.; Rezaee, M.; Zhou, C.; Pisupati, S.V. Recovery of rare earth elements from coal fly ash through sequential chemical roasting, water leaching, and acid leaching processes. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 284, 124725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reisman, D.; Weber, R.; McKernan, J.; Northeim, C. Rare Earth Elements: A Review of Production, Processing, Recycling, and Associated Environmental Issues; U.S. Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 2013.

- Julapong, P.; Numprasanthai, A.; Tangwattananukul, L.; Juntarasakul, O.; Srichonphaisarn, P.; Aikawa, K.; Park, I.; Ito, M.; Tabelin, C.B.; Phengsaart, T. Rare earth elements recovery from primary and secondary resources using flotation: A systematic review. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 8364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonzo, D.; Tabelin, C.B.; Dalona, I.M.; Abril, J.M.V.; Beltran, A.; Orbecido, A.; Villacorte-Tabelin, M.; Resabal, V.J.; Promentilla, M.A.; Suelto, M.; et al. Working with the community for the rehabilitation of legacy mines: Approaches and lessons learned from the literature. Resour. Policy 2024, 98, 105351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isacowitz, J.J.; Schmeidl, S.; Tabelin, C. The operationalisation of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) in a mining context. Resour. Policy 2022, 79, 103012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Research and Markets. Fly Ash Market Report and Forecast 2023–2028. Available online: https://www.researchandmarkets.com/reports/5869245/fly-ash-market-report-forecast (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- Prihutami, P.; Sediawan, W.B.; Astuti, W.; Prasetya, A. Effect of temperature on rare earth elements recovery from coal fly ash using citric acid. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 742, 012040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Rezaee, M.; Bhagavatula, A.; Li, Y.; Groppo, J.; Honaker, R. A review of the occurrence and promising recovery methods of rare earth elements from coal and coal by-products. Int. J. Coal Prep. Util. 2015, 35, 295–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franus, W.; Wiatros-Motyka, M.M.; Wdowin, M. Coal fly ash as a resource for rare earth elements. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2015, 22, 9464–9474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Sun, X.; Wang, Y.; Huang, C.; Zhao, Z. The sustainable and efficient ionic liquid-type saponification strategy for rare earth separation processing. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2016, 4, 1573–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, S.; Finkelman, R.B. Coal as a promising source of critical elements: Progress and future prospects. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2018, 186, 155–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hower, J.; Groppo, J.; Hsu-Kim, H.; Taggart, R. Distribution of rare earth elements in fly ash derived from the combustion of Illinois Basin coals. Fuel 2021, 289, 119990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taggart, R.K.; Hower, J.C.; Dwyer, G.S.; Hsu-Kim, H. Trends in the rare earth element content of U.S.-based coal combustion fly ashes. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 50, 5919–5926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolker, A.; Scott, C.; Hower, J.C.; Vazquez, J.A.; Lopano, C.L.; Dai, S. Distribution of rare earth elements in coal combustion fly ash determined by SHRIMP-RG ion microprobe. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2017, 184, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montross, S.; Verba, C.; Chan, H.; Lopano, C. Advanced characterization of rare earth element minerals in coal utilization byproducts using multimodal image analysis. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2018, 195, 362–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbon Brief. Analysis: Wind and Solar Added More to Global Energy than Any Other Source in 2023. Available online: https://www.carbonbrief.org/analysis-wind-and-solar-added-more-to-global-energy-than-any-other-source-in-2023 (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- Pan, J.; Nie, T.; Vaziri Hassas, B.; Rezaee, M.; Wen, Z.; Zhou, C. Recovery of rare earth elements from coal fly ash by integrated physical separation and acid leaching. Chemosphere 2020, 248, 126112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taggart, R.K.; Hower, J.C.; Hsu-Kim, H. Effects of roasting additives and leaching parameters on the extraction of rare earth elements from coal fly ash. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2018, 196, 106–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahan, A.M.E.; Alorro, R.D.; Pacaña, M.L.C.; Baute, R.M.; Silva, L.C.; Tabelin, C.B.; Resabal, V.J.T. Hydrochloric acid leaching of Philippine coal fly ash: Investigation and optimisation of leaching parameters by response surface methodology. Sustain. Chem. 2022, 3, 76–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, S.; Zhou, C.-C.; Pan, J.; Liu, C.; Tang, M.; Ji, W.; Hu, T.; Zhang, N. Study on influence factors of leaching of rare earth elements from coal fly ash. Energy Fuels 2018, 32, 8000–8005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prihutami, P.; Prasetya, A.; Sediawan, W.; Petrus, H.T.B.M.; Anggara, F. Study on rare earth elements leaching from magnetic coal fly ash by citric acid. J. Sustain. Metall. 2021, 7, 1241–1253. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, Z.; Zhou, C.; Pan, J.; Cao, S.; Hu, T.; Ji, W.; Nie, T. Recovery of rare-earth elements from coal fly ash via enhanced leaching. Int. J. Coal Prep. Util. 2020, 42, 2041–2055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, B.; Li, Q.; Zhang, W. Leaching recovery of rare earth elements from calcination product of a coal coarse refuse using organic acids. J. Rare Earths 2020, 40, 318–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silwamba, M.; Ito, M.; Hiroyoshi, N.; Tabelin, C.B.; Fukushima, T.; Park, I.; Jeon, S.; Igarashi, T.; Sato, T.; Nyambe, I.; et al. Detoxification of lead-bearing zinc plant leach residues from Kabwe, Zambia by coupled extraction–cementation method. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 104197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quiatchon, P.R.J.; Dollente, I.J.R.; Abulencia, A.B.; Libre, R.G.G., Jr.; Villoria, M.B.D.; Guades, E.J.; Promentilla, M.A.B.; Ongpeng, J.M.C. Investigation on the Compressive Strength and Time of Setting of Low-Calcium Fly Ash Geopolymer Paste Using Response Surface Methodology. Polymers 2021, 13, 3461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranay, K.A.; Pacaña, M.L.; Abid, A.R.; Baute, R.; Tabelin, C.B.; Silva, L.; Alorro, R.D.; Park, I.; Ito, M.; Arima, T.; et al. Characterization of coal fly ash from the Philippines and extraction of rare earth elements using mixed mineral–organic acids. SSRN, 2025; in press. [Google Scholar]

- Rosita, W.; Bendiyasa, I.; Perdana, I.; Anggara, F. Sequential particle-size and magnetic separation for enrichment of rare-earth elements and yttrium in Indonesian coal fly ash. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2019, 8, 103575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kukier, U.; Ishak, C.F.; Sumner, M.E.; Miller, W.P. Composition and element solubility of magnetic and non-magnetic fly ash fractions. Environ. Pollut. 2003, 123, 255–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, S.; Kang, Z.; Chen, L.; Fang, Y.; Zhuo, Y.; Xu, H. Characterization of aluminosilicates in fly ashes with different melting points using 27Al magic-angle spinning nuclear magnetic resonance. Energy Fuels 2017, 31, 10068–10074. [Google Scholar]

- Blissett, R.S.; Smalley, N.; Rowson, N.A. An investigation into six coal fly ashes from the United Kingdom and Poland to evaluate rare earth element content. Fuel 2014, 119, 236–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cockrell, C.F.; Leonard, J.W. Characterization and Utilization Studies of Limestone Modified Fly Ash; Coal Research Bureau: Morgantown, WV, USA, 1970; Volume 60. [Google Scholar]

- Chu, S.C.; Kao, H.S. A study of engineering properties of a clay modified by ash and slag. In Fly Ash for Soil Improvement; Sharp, K.D., Ed.; ASCE: New York, NY, USA, 1993; pp. 89–99. [Google Scholar]

- Ngo, S.-H.; Huynh, T.-P.; Le, T.-T.T.; Mai, N.-H.T. Effect of high loss-on-ignition fly ash on properties of concrete fully immersed in sulfate solution. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2018, 371, 012007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, M.; Brown, R. Comparison of the loss-on-ignition and thermogravimetric analysis techniques in measuring unburned carbon in coal fly ash. Fuel Energy Abstr. 2001, 15, 1414–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seredin, V.V.; Dai, S. Coal deposits as potential alternative sources for lanthanides and yttrium. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2012, 94, 67–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clean Air Asia. Coal Facts and Figures: An Issue Brief on Coal-Fired Power Plants in the Philippines; Clean Air Asia: Manila, Philippines, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Kutchko, B.G.; Kim, A.G. Fly ash characterization by SEM–EDS. Fuel 2006, 85, 2537–2544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmaruzzaman, M. A review on the utilization of fly ash. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2010, 36, 327–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elomaa, H.; Seisko, S.; Lehtola, J.; Lundström, M. A study on selective leaching of heavy metals vs. iron from fly ash. J. Mater. Cycles Waste Manag. 2019, 21, 1004–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lelong, C.; Nkulu, C.B.L.; Yabe, M. Extraction of rare earth elements from organic acid leachates: Mechanisms and environmental implications. Sustainability 2025, 17, 165. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, X.; Chen, L.; Liu, J. Rare earth elements recovery and mechanisms from coal and fly ash using citric acid leaching. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 501, 142210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhou, Q.; Xu, C. Hydrometallurgical recovery of rare earths from coal fly ash using organic and mixed-acid systems. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 458, 143267. [Google Scholar]

- Neil, K.E. Extraction and Stability Constants of Lanthanide–Citrate Complexes in Mixed Aqueous Systems. Master’s Thesis, Washington State University, Pullman, WA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne, R.H.; Liu, X.; Schijf, J. Comparative Complexation Behavior of the Rare Earths. Pure Appl. Chem. 1995, 67, 1305–1314. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, Z.; Liu, C. Organic Ligand-Mediated Dissolution and Fractionation of Rare-Earth Elements (REEs) from Carbonate and Phosphate Minerals. Minerals 2024, 14, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yahya, A.A.; Ali, N.; Samad, A.A.A.; Kamal, N.L.M.; Shahidan, S.; Abdullah, S.R. Mortar containing coal bottom ash (CBA) treated with citric acid as partial cement replacement. Int. J. Integr. Eng. 2024, 16, 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemmings, R.T.; Berry, E.E.; Cornelius, B.J.; Golden, D.M. Evaluation of acid-leached fly ash as a pozzolan. MRS Proc. 1988, 136, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldago, R.M. Fabrication of Non-Firing Ceramic Alkali-Activated Tile Using Hydrochloric Acid–Leached Fly Ash and Kapatagan Diatomaceous Earth. Bachelor’s Thesis, Mindanao State University–Iligan Institute of Technology, Iligan City, Philippines, 2023. Unpublished work. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).