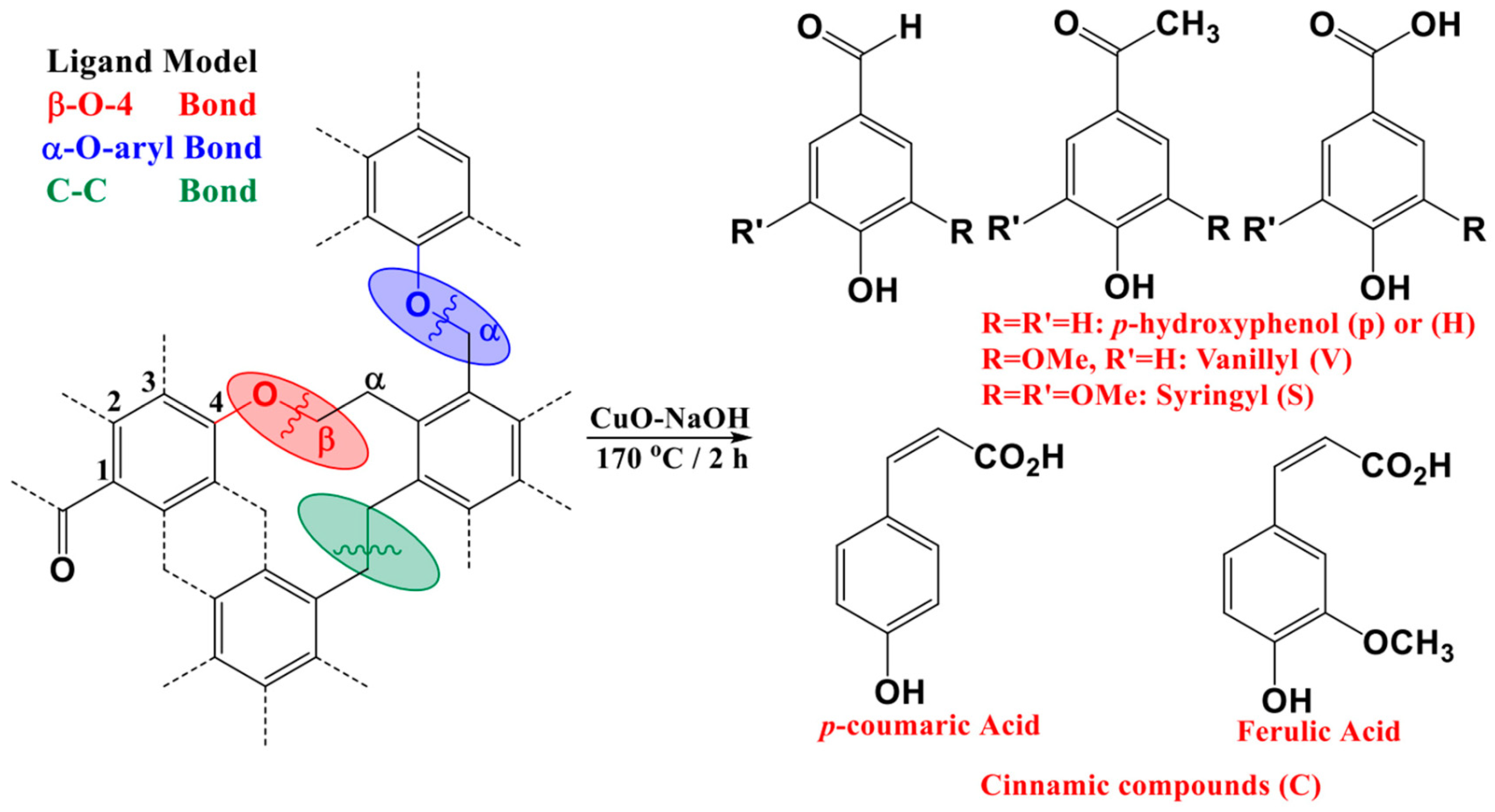

3.1. Lignin Proxies

The lignin proxies examined exhibited significant temporal and depth-dependent variations in lignin biomarkers, highlighting the effects of artichoke cultivation (2008–2011) and resting (2011–2012) practices on SOM dynamics (

Figure 3). In the surface layer (0 to −20 cm), SVC values increased under cultivation, reaching a maximum in November 2011 during the rest period. This increase reflects improved stabilization and microbial treatment of lignin under low disturbance and changing soil conditions [

1,

18,

20]. The reduction in the Ad/Al ratio during the resting period indicates increased lignin degradation, driven by microbial breakdown of aromatic structures. These patterns align with findings from Thevenot et al. [

1], who reported decreased trends for lignin degradation under reduced soil management intensity.

The H/S ratio is higher during resting periods compared to cultivation, indicating a relative increase in H-units within the lignin composition. This reflects changes in lignin inputs, microbial metabolism, and decomposition dynamics. During cultivation, crop residues such as artichoke, which predominantly contain S-units, lead to lower H/S ratios [

4,

8]. Conversely, resting periods are dominated by root-derived inputs, naturally higher in H-units content [

1,

19]. Additionally, since H-units are more stable than S-units, microbial activity during resting periods may preferentially degrade S-units, further enhancing H-units’ proportions [

1,

27]. This shift is further influenced by the absence of fresh aboveground plant exudates, directing microbial communities to utilize resistant root-exuded lignin while stabilizing H-compounds [

4,

8]. These mechanisms underscore the significance of resting periods in promoting SOM stabilization and suggest that higher H/S ratios can serve as indicators of reduced fresh biomass inputs and the selective preservation of recalcitrant lignin-associated compounds through sustainable soil management practices [

1].

In the middle layer (−20 to −60 cm), SVC values remained moderate during the cultivation phase but spiked sharply during the rest period in November 2011, with leaching and root-derived inputs identified as key contributors [

8,

19] (

Figure 3). Compared to surface samples, the middle layer exhibited similar or higher Ad/Al ratios, reflecting ongoing microbial activity that facilitates the breakdown of aromatic compounds and stabilization of more resistant lignin derivatives [

1,

18]. The consistent C/V ratios (approximately 0.1;

Figure 3) across this depth highlight the steady influence of C-based compounds, primarily associated with root structures and their gradual incorporation into SOM [

4,

8].

The lowest SVC values, indicating reduced input of fresh OM and a dominance of aged, stabilized compounds, were observed at the deepest layer (−60 to −100 cm;

Figure 3) [

1,

18]. The high S/V ratios at this depth suggest that S-compound deposition, primarily derived from vascular plant roots, dominates, consistent with findings by Hedges and Mann [

17]. Variations in Ad/Al ratios at this depth imply that decomposition processes, although slower, are still occurring due to limited microbial activity and improved substrate quality. These results underscore the recalcitrant nature of lignin fractions and their significant role in maintaining SOM stability in deeper soil profiles [

19].

Fer/Coum ratio indicates changes in lignin composition and microbial activity and varied significantly between cultivation and rest periods across all depths (

Figure 3). During cultivation, a comparatively higher Fer/Coum ratio highlighted the significant influence of ferulic-rich residues from crop inputs [

4,

8]. In contrast, during the rest period, this ratio decreased due to microbial degradation of ferulic-rich components, which are less recalcitrant compared to coumaric-rich components [

20]. Similarly, the H/S ratio significantly declined with depth during resting periods (particularly in May 2012,

Figure 3), reflecting the increased contributions of root-derived lignin and the selective decomposition of H-units by microbes [

4,

8].

These findings highlight the complex interactions between agricultural practices, microbial processes, and lignin stabilization in shaping SOM dynamics. The rest period in 2011–2012 appeared to promote microbial activity, enhancing lignin turnover and stabilization in subsurface layers. Sustainable management practices, such as fallow periods and periodic tillage, can significantly influence SOM quality and contribute to long-term carbon sequestration. These insights align with broader literature [

18,

19,

20], emphasizing the critical role of agricultural management in maintaining soil health and mitigating carbon loss.

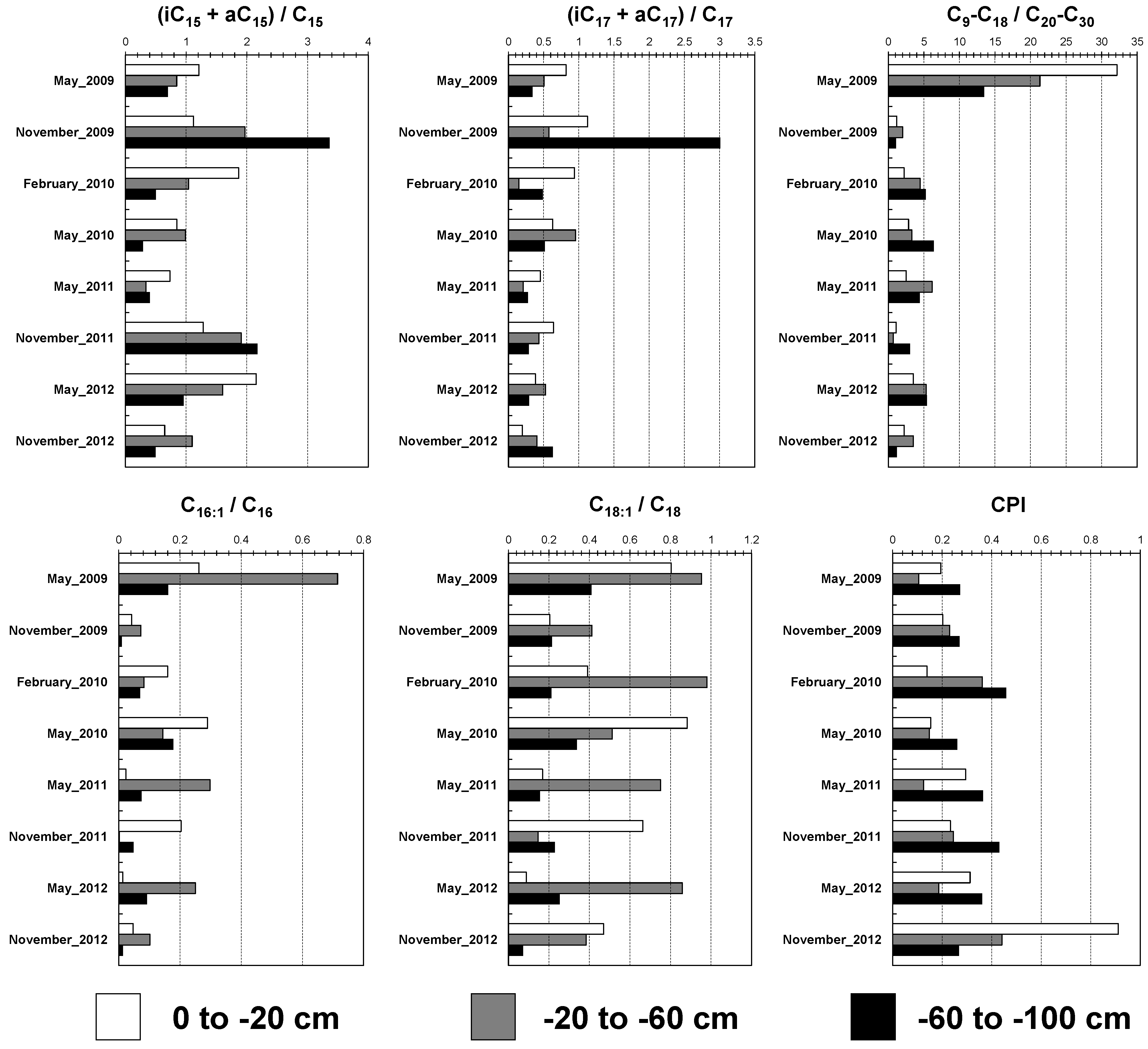

3.2. Lipid Proxies

Lipid biomarker proxies demonstrate remarkable differences both over time and across soil depths, reflecting the effects of agricultural practices (artichoke cultivation from 2008–2011) and a subsequent rest period (2011–2012) (

Figure 4). These changes underline significant shifts in microbial activity, OM dynamics, and stabilization processes. Microbial communities in the surface layer (0 to −20 cm;

Figure 4) were highly responsive to management practices. During the rest period, the i15+a15/C15 ratio peaked (May 2012: 2.15;

Figure 4), indicating enhanced microbial activity due to reduced soil disturbance. This finding aligns with Conant et al. [

28], who observed that fallow systems promote microbial adaptations. Conversely, during cultivation, the C9-C18/C20-C30 ratio reached its highest level (May 2009: 32.15;

Figure 4), reflecting fresh OM inputs and the rapid turnover of plant-derived lipids, as crop residues served as microbial substrates [

4,

18]. The decline in C16:1/C16 and C18:1/C18 ratios during the rest period (May 2012: 0.014 and 0.088;

Figure 4) suggests reduced lipid biosynthesis, indicating a microbial shift toward stabilization rather than fresh lipid production [

8]. Similarly, the rise in CPI values during the rest period (November 2012: 0.91;

Figure 4) indicates the accumulation of stable lipid fractions, reflecting slower decomposition rates and long-term OM stabilization, as noted by Rasse et al. [

19].

In the intermediate layer (−20 to −60 cm), the lipid profile indicates a transition zone influenced by both surface inputs and deeper soil processes. During rest periods, the i15+a15/C15 ratio showed a moderate increase (November 2011: 1.91;

Figure 4), suggesting microbial utilization of OM transported from above, such as leached compounds or root exudates [

4,

19]. Conversely, a decline in the C9-C18/C20-C30 ratio during rest periods (November 2011: 0.70;

Figure 4) points to reduced contributions of short-chain lipids, likely due to the limited availability of fresh OM from the surface. This finding aligns with Kögel-Knabner [

4], who observed that contributions of recent organic inputs diminish with increasing soil depth. Furthermore, microbial activity, as indicated by the C16:1/C16 ratio, decreased significantly during rest (November 2011: 0.002;

Figure 4), reflecting constrained microbial activity due to limited substrate availability. Despite these declines, the CPI value showed moderate increases (February 2010: 0.36;

Figure 4), indicating that stabilization processes led to the accumulation of more resistant lipid fractions. This pattern is consistent with studies highlighting slower turnover in intermediate soil layers [

29].

At the deepest layer (−60 to −100 cm), lipid biomarkers indicate low microbial activity and a predominance of stabilized OM. This is reflected in the consistently low C9-C18/C20-C30 ratios (November 2012: 1.21;

Figure 4), suggesting the absence of fresh lipid contributions from microbial organisms [

4,

8]. Similarly, the low values of C16:1/C16 and C18:1/C18 (November 2012: 0.014 and 0.072, respectively;

Figure 4) highlight reduced lipid biosynthesis, likely due to nutrient limitations and reduced oxygen availability at this depth [

1]. Despite these constraints, occasional spikes in the i15+a15/C15 ratio (November 2009: 3.36;

Figure 4) suggest sporadic microbial activity in the deeper layers. A similar upward trend in this ratio was also observed in November 2011.

These findings emphasize how agricultural practices and soil management shape lipid dynamics over time and across depths. Cultivation periods encourage microbial turnover and fresh OM inputs, while rest periods promote the stabilization of organic compounds, particularly at greater depths. This interplay of processes underscores the importance of sustainable soil management strategies that balance OM turnover with long-term stabilization, ensuring soil health, fertility, and carbon storage.

3.3. OM Dynamics with Time and Depth

The comparison of lignin-derived and lipid biomarker proxies provides interesting insights into SOM dynamics in response to agricultural practices and fallow periods. This comparison highlights both shared trends and unique behaviors across time and depth, illustrating how these compounds react differently to changes in soil management. The findings align with prior investigations, emphasizing the critical roles of microbial activity, organic inputs, and stabilization mechanisms. Through a long-term study of a Mediterranean agricultural soil system (artichoke cultivation: 2008–2011; rest period: 2011–2012), the temporal and spatial variability of these proxies offers valuable information to enhance our understanding of SOM responses, contributing to improved soil management practices.

In the surface soil layer (0 to −20 cm), both lignin and lipid biomarkers showed clear responses to agricultural activities and subsequent rest periods. At the transition between cultivation and rest (November 2011;

Figure 3), SVC increased significantly, suggesting enhanced microbial processing and stabilization of lignin compounds under conditions of reduced disturbance. Similarly, lipid biomarkers like i15+a15/C15 exhibited increases in November 2011 and May 2012 compared to the directly preceding sampling times (

Figure 4), reflecting heightened microbial activity when the soil was less disturbed. These findings align with previous studies showing that fallow periods foster microbial growth due to reduced rest [

4,

8,

18]. During rest periods, Ad/Al ratios decreased (

Figure 3), indicating intensified lignin decomposition driven by microbial breakdown of its complex aromatic structures, consistent with findings by Thevenot et al. [

1]. Conversely, lipid biomarkers such as C16:1/C16 and C18:1/C18 exhibited reduced synthesis during rest periods, suggesting a shift in microbial lipid production toward stabilization rather than the creation of fresh lipids [

4,

8].

During cultivation, lignin proxies indicated elevated S/V ratios, reflecting a stronger contribution of angiosperm-derived lignin—rich in syringyl units—from crop residues such as artichoke, consistent with the dominance of herbaceous plant inputs in surface soils [

1]. This aligns with findings by Kögel-Knabner [

4], who highlighted the significant role of plant residues in surface SOM. Similarly, lipid proxies exhibited high C9-C18/C20-C30 ratios during cultivation (May 2009: 32.15;

Figure 4), reflecting the abundance of short-chain lipids typically associated with fresh organic inputs and active microbial turnover. As the soil transitioned to the rest period, CPI increased markedly (November 2012: 0.91;

Figure 4), suggesting the stabilization of odd-chain, plant-derived lipid components [

25,

30]. Following a similar pattern, lignin decomposition slowed during rest periods, as indicated by declining Ad/Al ratios. This illustrates the shared pathways through which lignin and lipid compounds contribute to SOM stabilization (

Figure 3).

In the middle layer (−20 to −60 cm), the proxies suggest a transitional zone influenced by surface inputs and subsurface processes. SVC values moderately decreased during cultivation but spiked significantly during the rest period (November 2011;

Figure 4), reflecting contributions from leaching and root-derived inputs [

19]. Similarly, i15+a15/C15 ratio increased during the rest period (November 2011: 1.91;

Figure 4), aligning with microbial utilization of OM transported from the surface layer. However, both lignin and lipid proxies indicated a decline in markers associated with fresh inputs—C/V for lignin and C9-C18/C20-C30 for lipids—suggesting reduced contributions of short-chain and C-based compounds. These findings are consistent with Kögel-Knabner’s [

4] observation of diminishing fresh OM inputs with depth and a shift toward more stabilized compounds.

Microbial activity, indicated by proxies such as C16:1/C16, declined markedly during the rest period (November 2011: 0.002;

Figure 4), reflecting substrate limitations [

4,

8]. Ad/Al ratios steadily increased from November 2011 to May 2012 (

Figure 3), pointing to the ongoing decomposition of aromatic structures. While lignin decomposition persisted, lipid turnover appeared to slow, which facilitated lipid stabilization, as evidenced by the moderate decrease in CPI observed between November 2011 and May 2012 (

Figure 4). These dynamics highlight the intricate interactions in transitional soil layers, where both leaching and microbial activity significantly influence the composition and stabilization of SOM [

8,

19].

At the deepest layer (−60 to −100 cm), both lignin and lipid proxies consistently indicated reduced inputs of fresh OM and slower decomposition. SVC values remained low throughout, reflecting the limited availability of fresh material (

Figure 3). This aligns with the low C9-C18/C20-C30 ratios observed in these depths, signifying the dominance of stabilized, long-chain FAs (

Figure 4). High S/V ratios for lignin suggest contributions of S-units lignin from vascular plant roots (

Figure 3), emphasizing inputs from woody tissues [

1,

17]. CPI values remained stable (0.2–0.4;

Figure 4), further confirming the persistence of recalcitrant compounds in deep soil layers [

25,

30].

The comparison of lignin and lipid proxies demonstrates that while both highlight overarching trends in SOM dynamics, they provide complementary perspectives. Lignin biomarkers are particularly responsive to plant-derived inputs and decomposition dynamics, offering valuable insights into the turnover of aromatic compounds and the contributions of above- and belowground biomass [

1,

17,

19]. Lipid biomarkers, by contrast, are more sensitive to microbial activity, lipid synthesis, and stabilization processes, capturing shifts in microbial community composition and the preservation of recalcitrant compounds [

4,

8,

25]. Together, these proxies reveal the interplay of agricultural practices, microbial activity, and stabilization processes in shaping SOM composition across soil depths.

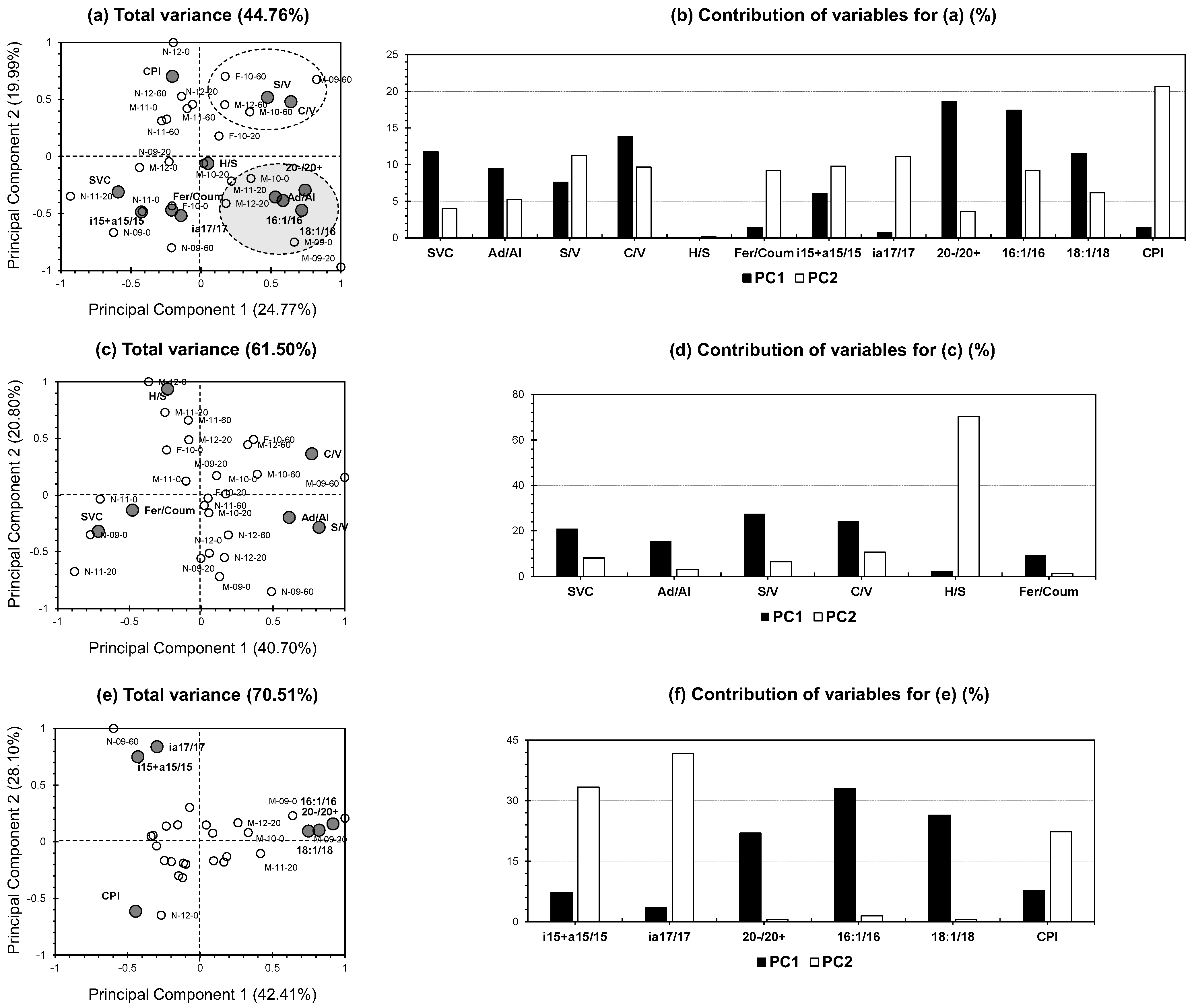

3.4. Application of PCA to Molecular Proxies

PCA is a versatile multivariate analysis tool widely employed in geochemistry and soil studies to simplify complex datasets and reveal significant patterns and relationships [

16]. It aids in determining the origins of OM—whether terrestrial or marine—and tracing its transformations across various environments [

31]. PCA also facilitates the comparison of samples, identifies trends such as similarities and differences, and helps create meaningful metrics like degradation indices [

16,

32]. For instance, Schellekens [

32,

33,

34] applied PCA to study molecular changes in peat, uncovering long-term vegetation shifts and decomposition pathways. Cordovil et al. [

35] utilized PCA to examine how organic amendments, such as compost and slurry, aid in post-fire soil recovery. Similarly, Zhou et al. [

9] employed PCA to explore how decaying plant material impacts dissolved organic carbon and nitrogen in tropical soils. By reducing the complexity of intricate relationships into easily interpretable components, PCA serves as an invaluable tool for deriving insights and visualizing data, making it essential for advancing sustainable soil and environmental management [

9,

35]. In this study, PCA was applied to assess similarities and differences between the lipid and lignin proxies utilized. The application of this multidimensional statistical method has the potential to validate or question the interrelationships among the proxies, thereby extending our understanding of SOM dynamics. To ensure clearer interpretation of molecular patterns, three separate PCA models were generated: one incorporating all lignin and lipid proxies (

Figure 5a,b), one restricted to lignin-derived ratios (

Figure 5c,d), and one restricted to lipid-derived ratios (

Figure 5e,f), allowing plant-derived and microbial-derived contributions to be examined independently.

3.4.1. PCA All Dataset

Figure 5a,b illustrate the PCA-biplot incorporating the entire dataset (both lignin and lipid proxies). The first two PCs accounted for 44.76% of the total variance, with PC1 contributing 24.77% and PC2 contributing 19.99% (

Figure 5a). Compared to other PCA studies in geochemical contexts, our results indicate a moderate to low contribution [

16]. This discrepancy may be attributed to differences in the mechanistic approaches between the two molecular analysis techniques: CuO-NaOH oxidation and lipid extraction. The first involves the cleavage of C-C and C-O bonds in lignin through high-temperature redox reactions (170 °C; [

17]), while the second consists of a simpler process involving the maceration of soil samples with organic/aqueous solvents followed by fraction separation using liquid chromatography. Despite this, the analyzed samples exhibit a well-distributed pattern across the biplot, aiding in the identification of distinct temporal and spatial trends. Two primary clusters are evident: a white cluster and a gray cluster. The white cluster, comprising exclusively deepest samples (−60 to −100 cm;

Figure 5a), correlates strongly with lignin vegetation indicator proxies, such as C/V and S/V. In contrast, the gray cluster is predominantly composed of middle-depth samples (−20 to −60 cm;

Figure 5a) and exhibits high correlations with Ad/Al, C16:1/C16, C18:1/C18, and C9-C18/C20-C30—proxies often associated with microbial activity. This distinction highlights the middle depth as a transitional zone between two ecological niches: a fresh OM input zone at the upper layers and a vegetation deposition zone at the lower layers [

9,

20]. This integrative approach not only underscores the utility of combining lignin and lipid proxies in soil studies but also reveals nuanced patterns of OM cycling [

1,

18,

19].

SVC, i15+a15/15, i17+a17/17, and Fer/Coum exhibit a negative influence on the first two PCs (

Figure 5a). These proxies are closely related, indicating a shared response to the dynamic interplay between lignin inputs, microbial activity, and OM stabilization. Microbial activity, which decomposes lignin and synthesizes branched FAs, explains the tight linkage of SVC with microbial biomarkers i15+a15/C15 and i17+a17/C17 [

36]. This relationship suggests that microbial reworking zones, particularly in surface and middle soil layers, lead to a simultaneous decline in lignin concentration and microbial lipid synthesis as OM stabilizes [

1,

18,

20]. This dynamic is highlighted by the proximity of probable surface samples to these proxies in terms of arrangement, contrasting with the negative positioning of these proxies relative to the white cluster (representing middle-layer samples;

Figure 5a). The inclusion of Fer/Coum further underscores the likelihood of microbial preference for degrading ferulic acids during active OM turnover [

37,

38]. Together, these proxies portray a unified view of OM dynamics, where lignin decomposition is closely tied to microbial lipid synthesis and the preferential degradation of C-compounds.

Figure 5b displays the contributions of the studied variables to the first two PCs. For PC1, the largest contributors were C9-C18/C20-C30 and C16:1/C16 (18.62% and 17.42%, respectively;

Figure 5b), underscoring the dominant role of microbial lipid proxies in explaining primary dataset variance. Conversely, the low contributions of other proxies to PC1 suggest that, while these variables capture niche-specific dynamics, they have a less significant impact on overall variability. For PC2, CPI emerged as the leading contributor (20.70%), reflecting the impact of lipid chain length and stabilization processes on the secondary axis. This finding highlights the utility of CPI as an indicator of OM maturity, particularly in deeper soil layers dominated by stabilized lipids. The PCA-biplot further illustrates this strong association between CPI and deeper soils through its high positive correlation with the white cluster representing lower-depth samples (

Figure 5a).

3.4.2. PCA of Subsets

Figure 5c,d present the PCA biplot focusing exclusively on lignin proxies, with the first two PCs accounting for 61.50% of the total variance (40.70% for PC1 and 20.80% for PC2;

Figure 5c). No specific clustering is evident among the individuals, as the soil samples are distributed throughout the plot. Notably, positive correlations are observed for Ad/Al along with the vegetation indicator proxies’ C/V and S/V. These ratios, widely recognized as vegetation source markers, are also effective indicators of lignin degradation under certain soil conditions [

1].

The phenol ratios derived from S, V, and C-lignin distributions provide valuable insights into both the types of plant inputs and the extent of lignin decomposition. Studies demonstrate that S- and C-units are degraded more rapidly than V-units during lignin breakdown [

17,

39,

40]. This discrepancy arises from the structural characteristics of the phenols, with V-units showing greater resistance to microbial and enzymatic degradation [

1,

17]. Consequently, lower S/V and C/V ratios in soil lignin profiles often signal advanced stages of decomposition, particularly in soils experiencing microbial activity and oxidative processes [

1]. Shifts in these ratios, linked to oxidative degradation intensity, underscore their utility as indicators of SOM decomposition [

41]. These ratios serve a dual role as both source and degradation indicators, enabling the tracing of vegetation inputs and the tracking of lignin alterations across different environmental contexts. This enhances understanding of lignin’s role in carbon cycling and turnover in soils [

1]. Similar to the PCA results for the entire dataset (

Figure 5a), SVC and Fer/Coum exhibited close proximity, both positioned negatively along the axes of both PCs. This proximity reflects their shared responsiveness to OM dynamics, especially those driven by lignin inputs and microbial degradation processes. Their alignment on the negative axis also suggests high sensitivity to the availability of fresh lignin and its decomposition, supported by the proximity of surface samples to SVC and Fer/Coum (N-11-0 and N-09-0;

Figure 5c). Regarding variable contributions along the first two PCs (

Figure 5d), all variables displayed moderate to low contributions to PC1, except for H/S, which made a significant contribution to PC2 (70.28%;

Figure 5d). Statistically, this result indicates that H/S captures unique variance within the dataset not shared with other lignin proxies, consistent with the concept that PCA, by design, generates orthogonal (independent) components, each reflecting distinct underlying patterns in the data [

42].

Figure 5e,f display the PCA biplot focusing solely on lipid proxies, where the first PCs account for 70.51% of the total variance (42.41% for PC1 and 28.10% for PC2;

Figure 5e). Notably, microbial proxies exhibit two distinct patterns. The close proximity of i15+a15/C15 and i17+a17/C17 on PC2, alongside the grouping of C16:1/C16, C18:1/C18, and C9-C18/C20-C30 on PC1, highlights differences in microbial dynamics related to soil depth in agricultural settings (

Figure 5e). The first group, composed of branched FAs ratios, reflects the contributions of Gram-positive bacteria [

10,

23]. The strong loading of this group on PC2 indicates that it captures variance related to microbial community composition rather than metabolic activity. This association suggests a link to long-term microbial stability and resilience [

10,

23]. The predominance of Gram-positive bacteria, often associated with deeper soil layers, reflects their resistance to environmental stressors such as oxygen limitation and lower nutrient availability, conditions prevalent in depths beyond immediate agricultural inputs. This finding is supported by the proximity of deep-layer samples (N-09-60) to these proxies (

Figure 5e). Conversely, the second group (C16:1/C16, C18:1/C18, and C9-C18/C20-C30;

Figure 5e) correlates positively with intermediate soil depths (−20 to −60 cm), suggesting these ratios indicate active microbial metabolism in transitional zones. These regions serve as interfaces where OM inputs from surface layers meet stabilized OM from deeper layers. These proxies are associated with monounsaturated FAs, which are markers of Gram-negative bacteria, highlighting their dominance in metabolically active zones [

10,

23]. Together, these groups provide complementary perspectives on microbial contributions to soil microbial activity. The differentiation between PC1 and PC2 illustrates how microbial functions vary with soil depth and bacterial community composition in response to agricultural practices. Regarding variable contributions along the first two PCs (

Figure 5f), a clear independence between the two clusters of microbial proxies is evident.

In brief, PCA offers critical insights into the interactions between lignin and lipid proxies, shedding light on depth-dependent processes in OM cycling. When considering the entire dataset (simultaneous inclusion of lignin and lipid proxies;

Figure 5a,b), distinct clustering of samples highlights ecological niches across depths. Deep soil layers (−60 to −100 cm) are predominantly associated with lignin-derived proxies such as C/V and S/V, indicative of stabilized vegetation inputs. In contrast, middle depths (−20 to −60 cm) are characterized by microbial reworking proxies like Ad/Al, C16:1/C16, and C18:1/C18, reflecting active microbial processing. CPI stands out as a key indicator of OM maturity along the secondary axis, particularly in deeper soils. The grouping of proxies such as SVC, i15+a15/C15, i17+a17/C17, and Fer/Coum underscores their shared roles in linking lignin decomposition, microbial activity, and OM stabilization.

However, the analysis is constrained by a relatively low total variance explained by the first two PCs (44.76%;

Figure 5a), likely due to methodological differences between CuO-NaOH oxidation and lipid extraction. This overlap highlights the necessity for complementary methods or additional variables to enhance PCA accuracy.

When the subset approach was employed (

Figure 5c–f), higher variance was observed (60–70%). In lignin PCA, C/V and S/V positively correlated with Ad/Al [

1,

17], while SVC and Fer/Coum clustered on the negative side, associated with surface samples. In lipid PCA, i15+a15/C15 and i17+a17/C17 grouped along PC2 (deep layers), and C16:1/C16, C18:1/C18, and C9-C18/C20-C30 along PC1 (intermediate depths), indicating contrasting microbial dynamics [

10,

23].