Abstract

Educational construction projects face the dual challenge of achieving sustainability targets while remaining cost-effective, yet existing studies often analyze supply chain drivers in isolation. This research addresses this gap by developing and validating a comprehensive model that examines five critical drivers—material selection, stakeholder engagement, waste management, energy efficiency, and digital technologies—within the context of educational infrastructure. Using a mixed-methods approach, data were collected through surveys with 100 industry professionals (35% project managers, 30% architects/designers, and 35% policymakers/consultants), 20 semi-structured interviews, and comparative analysis of three international case studies (Egypt, Singapore, and the United States). Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) was applied to test hypothesized relationships, supported by thematic analysis for qualitative depth. Results show that stakeholder engagement (β = 0.31), material selection (β = 0.28), and digital technologies (β = 0.23) exert the strongest influence on sustainability performance, while energy efficiency (β = 0.19) and waste management (β = 0.16) demonstrate weaker but still significant effects. Regional variations highlight the role of contextual factors such as governance, policy support, and infrastructure readiness. Unlike prior studies that focus on single aspects, this research offers an integrated framework for evaluating and implementing sustainable supply chain practices in educational construction. The findings provide both theoretical advancement and actionable insights for policymakers and practitioners seeking to accelerate sustainable transformation in the education sector.

1. Introduction

The construction industry is one of the most resource-intensive sectors globally, responsible for 25–40% of carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions and more than one-third of solid waste each year [1]. Within this sector, educational construction—covering schools, universities, and campus facilities—presents a distinctive context. Such projects are large, long-lived investments that not only must meet sustainability [2] and cost-effectiveness targets but also serve as “living laboratories,” shaping sustainability awareness among future generations [3]. Their societal role in embedding environmental responsibility distinguishes them from residential or commercial construction, making the study of sustainable supply chains in this domain both operationally and socially significant. Educational construction projects also differ substantially from other public or commercial buildings in ways that directly influence sustainable supply chain requirements. These facilities typically operate with higher occupancy densities, longer daily usage hours, and more diverse functional zones such as laboratories, classrooms, workshops, dormitories, and high-performance HVAC systems. This complexity results in distinct material, energy, and waste management demands. Additionally, educational institutions often commit to ambitious sustainability frameworks—such as LEED for Campus, BREEAM Education, and national green campus initiatives—which impose stricter procurement, life-cycle assessment, and supplier transparency requirements [4]. Their role as “living laboratories” further amplifies the need for construction processes that demonstrate innovation and environmental leadership. These characteristics make the educational sector a unique and strategically important domain for examining sustainable supply chain practices. Achieving sustainability in educational projects is particularly challenging. Cost constraints, diverse stakeholders, and strict regulatory requirements often hinder the adoption of environmentally preferable practices [5,6]. This complexity underscores the role of Sustainable Supply Chain Management (SSCM), which integrates environmental, social, and economic considerations across procurement, design, and delivery stages [7].

Previous studies have offered valuable insights but mostly analyzed SSC (Sustainable Supply Chain) drivers in isolation. For example, some focused narrowly on material optimization [8,9], others on digital technologies such as BIM and IoT [10,11], while others emphasized stakeholder collaboration [12]. While useful, this fragmented approach overlooks the interdependencies among drivers and the synergies that emerge when strategies are combined [13]. Moreover, empirical studies dedicated to educational construction remain scarce compared to other sectors, despite its unique governance structures, funding models, and long-term performance requirements [14]. These sector-specific constraints reinforce the need for a tailored analysis of supply chain practices that recognizes the distinct operational and governance context of educational buildings. Recent technological and managerial innovations illustrate both opportunities and challenges. Material selection strategies such as low-carbon concrete and cross-laminated timber have reduced embodied energy in pilot projects [8,15], while digital tools like BIM and IoT improve lifecycle performance monitoring [10,16,17]. Similarly, collaborative approaches, including Integrated Project Delivery (IPD) and participatory planning, have shown that early stakeholder engagement reduces cost overruns and enhances sustainability outcomes [12,18]. However, barriers such as high upfront costs, fragmented contracts, and cultural resistance continue to undermine consistent implementation [19]. To identify the most influential drivers of sustainable supply chain performance in construction, an extensive systematic literature synthesis was conducted. More than seventy peer-reviewed studies published between 2008 and 2024 were reviewed across leading journals in sustainability and construction management. Through thematic coding and frequency analysis, five recurring and theoretically grounded drivers emerged—Material Selection, Stakeholder Engagement, Waste Management, Energy Efficiency, and Digital Technologies [20]. These dimensions collectively reflect the environmental, managerial, and technological pillars of sustainable supply chain management, aligning with the Triple Bottom Line (TBL) and Resource-Based View (RBV) theoretical perspectives frequently cited in the literature (Seuring & Müller, 2008; Carter & Rogers, 2008; Kibwami & Tutesigensi, 2022) [1,21,22]. Alternative drivers such as cost, regulatory frameworks, workforce training, and organizational culture were initially considered but excluded to maintain conceptual clarity and avoid overlap, as these factors often function as contextual moderators rather than primary supply chain mechanisms. This theoretical refinement ensures that the model focuses on the core operational drivers most consistently supported by prior research and applicable to the educational construction context.

This study responds to these gaps by adopting a systems perspective that evaluates five interrelated SSC drivers—material selection, stakeholder engagement, waste management, energy efficiency, and digital technologies—within educational construction. Using a mixed-methods approach, survey data from 100 professionals, supported by 20 interviews and three international case studies, were analyzed with Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) and thematic analysis. This integrative approach provides both theoretical insights into the interaction of SSC drivers and practical recommendations for policymakers and practitioners.

2. Materials and Methods

This study adopted a convergent parallel mixed-methods design (Creswell & Plano Clark, 2018) [23], allowing quantitative and qualitative data to be collected and analyzed independently and then integrated during interpretation. The quantitative strand employed a structured questionnaire and Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) to test hypothesized relationships among the five Sustainable Supply Chain (SSC) drivers and sustainable success outcomes. In parallel, qualitative data from semi-structured interviews and case studies were gathered to provide deeper contextual insights into how and why these drivers influence implementation practices across different regions and project types. The mixed-methods approach was selected to ensure both breadth and depth of understanding. Quantitative data provided generalizable patterns and statistical relationships, while qualitative data explored underlying mechanisms, barriers, and regional nuances that numbers alone could not capture. Integration occurred during the interpretation phase, where convergent and divergent findings were compared to enhance validity and highlight areas of complementarity or contradiction between data sources.

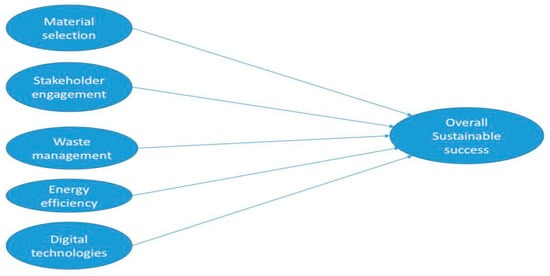

The proposed conceptual framework (Figure 1) was developed from a systematic thematic review of 72 peer-reviewed publications addressing sustainability and supply chain management in the construction sector. The review aimed to identify the most recurrent and empirically supported drivers influencing sustainable project outcomes. Thematic clustering revealed five dominant categories—Material Selection, Stakeholder Engagement, Waste Management, Energy Efficiency, and Digital Technologies—which consistently appeared across diverse contexts (Darko et al., 2019; Agyekum et al., 2022; Liu et al., 2024; Cheng et al., 2024) [24,25,26,27]. Each driver was selected for its theoretical and practical relevance. Material Selection captures lifecycle and embodied energy considerations; Stakeholder Engagement represents governance and collaborative management dimensions; Waste Management reflects resource efficiency and circularity; Energy Efficiency covers operational performance; and Digital Technologies (e.g., BIM, IoT, blockchain) act as cross-cutting enablers of data-driven decision-making. Together, these drivers operationalize the environmental, managerial, and technological domains emphasized in sustainable construction theory. The initial framework was refined through an expert validation process, involving consultation with five sustainability practitioners and academics to ensure construct coverage and clarity. Their feedback confirmed the theoretical robustness and measurability of the five chosen drivers. Alternative categories such as regulatory frameworks and organizational culture were acknowledged but omitted to maintain model parsimony and analytical coherence. This framework served as the foundation for the survey instrument and guided the design of interview and case study protocols, ensuring theoretical and methodological alignment throughout the study.

Figure 1.

Proposed Conceptual Framework for SSC Drivers in Educational Construction.

2.1. Sampling and Participant Recruitment

This study employed a purposive–snowball sampling strategy to ensure that participants possessed direct and relevant experience in sustainable educational construction projects. Given the specialized focus of this research, random sampling was impractical because the target population—professionals engaged in sustainability-related construction management and policy—is relatively limited and geographically dispersed. Therefore, purposive sampling was adopted to reach qualified respondents, while snowball recruitment was used to expand participation through professional referrals. This approach follows Etikan et al. (2016) [28], who recommend purposive–snowball techniques when sampling experts from niche professional domains.

Inclusion criteria required that participants:

- Have a minimum of five years of professional experience in the construction or infrastructure sector;

- Have participated in at least one educational construction project that integrated sustainability or supply chain management practices;

- Hold a professional or managerial role directly influencing planning, procurement, or policy decisions (e.g., project manager, architect/designer, consultant, policymaker).

Individuals who worked exclusively in unrelated sectors or had no direct project-level involvement were excluded. Participants were identified through professional associations, LinkedIn groups, and institutional mailing lists focusing on sustainable or educational construction. Initial invitations were sent to targeted networks, and respondents were asked to recommend additional qualified professionals, allowing expansion through snowballing. A total of 161 invitations were distributed across three regions—Egypt (38%), Singapore (33%), and the United States (29%)—selected to represent varying policy environments and levels of sustainability maturity. Ultimately, 100 valid responses were received, representing a 62% response rate. To minimize selection bias, recruitment included professionals from different organization types, such as construction firms, government agencies, consulting offices, and academic institutions. Participants represented a wide range of professional roles—35% project managers, 30% architects or designers, and 35% policymakers or consultants—ensuring a balanced perspective on sustainable practices. The online questionnaire was administered using Google Forms, ensuring broad accessibility across regions. To test for non-response bias, early and late respondents were compared on demographic variables, showing no statistically significant differences (p > 0.05) (Table 1). Participation was voluntary, with informed consent obtained electronically. No identifying information was collected to preserve anonymity. Ethical approval was granted by the Institutional Review Board of the Military Technical College, Cairo (Protocol No. MTC-228-2025).

Table 1.

Respondent Demographics and Regional Distribution.

2.2. Survey Design and Sample Adequacy

The questionnaire contained 4–6 reflective items for each Sustainable Supply Chain (SSC) construct, measured on a five-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree). All items were adapted from validated SSCM literature and refined through expert review. Since all respondents were proficient in English, no translation or back-translation was required. The full list of items is presented in Table 2. A power analysis using GPower [29] 3.1* (f2 = 0.15, α = 0.05, power = 0.80, predictors = 5) indicated a minimum required sample size of 92, confirming that the obtained sample (n = 100) satisfies statistical adequacy for Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM). Although smaller than conventional SEM guidelines (10 observations per indicator), PLS-SEM is widely recognized as robust for moderate samples and exploratory frameworks (Hair et al., 2019) [30]. The limitation of sample size and non-random sampling is acknowledged in Section 4.10.

Table 2.

Measurement Items for SSC Constructs.

To complement the survey, 20 semi-structured interviews were conducted with professionals directly involved in sustainability-oriented educational projects. Interviews continued until thematic saturation was reached at the eighteenth session, defined as the point where no new codes emerged; two additional interviews confirmed stability. Each session lasted 45–60 min, was recorded with consent, and transcribed for analysis. In addition, three international case studies were analyzed: eco-campus projects in Egypt, Singapore’s Green Campus Initiative, and LEED-certified schools in the United States. These cases were chosen to represent diverse policy and regulatory contexts, ranging from emerging market challenges to digitally advanced frameworks and mature certification systems.

2.3. Quantitative Strand: Survey Design and Analysis

Survey data were analyzed using SmartPLS (v3.2.9). Reliability was assessed through Cronbach’s Alpha and Composite Reliability (CR), all exceeding 0.80. Convergent validity was confirmed with AVE values greater than 0.50, and discriminant validity was evaluated using both the Fornell–Larcker criterion and the Heterotrait–Monotrait (HTMT) ratio, with all HTMT values below 0.85. To assess common method bias, both Harman’s single-factor test and full collinearity VIFs were applied, with all VIF values below 3.3, indicating no significant bias. The structural model was evaluated using bootstrapping with 5000 subsamples. Model fit indices included SRMR (0.061) and NFI (0.92), both within acceptable thresholds. Prior to analysis, the dataset was screened for missing values, outliers, and distributional irregularities. Missing data accounted for 2.7% of all responses and were confirmed to be Missing Completely at Random (MCAR) using Little’s test [31] (p > 0.05). Given the small proportion of missingness and the robustness of PLS-SEM to MCAR data, mean substitution was applied as a conservative and minimally distortive method. This approach is commonly used in PLS-SEM studies when missingness is below 5% and when the goal is to preserve the original distributional characteristics without inflating variance estimates. Outliers were assessed using standardized z-scores for each indicator. Values exceeding ±3 standard deviations were detected in four cases (representing 1.8% of the dataset). Following established methodological recommendations, these values were winsorized to the nearest non-extreme boundary to reduce the influence of artefactual extremes while retaining the affected observations in the analysis. This threshold (±3 SD) is widely recognized in behavioral and construction management research as a reasonable criterion for detecting infrequent anomalies caused by measurement noise rather than true population variance. To ensure that these preprocessing decisions did not meaningfully alter the structural relations, a robustness check was conducted by rerunning the PLS-SEM model using the unadjusted dataset. Path coefficient significance patterns remained consistent, indicating that the imputation and winsorization procedures did not bias the analytical results.

Interview transcripts were analyzed thematically following Braun and Clarke’s [32] six-step framework using NVivo 12 Plus. Coding was inductive, and intercoder reliability was ensured by double-coding 10% of transcripts and resolving discrepancies through discussion. Case study findings were triangulated with survey and interview results to enhance credibility and provide contextual depth. Ethical approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of the Military Technical College, Cairo, Egypt, under protocol number MTC-228-2025. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants, and all data were anonymized and securely stored.

2.4. Quantitative Strand: Semi-Structured Interviews

To complement the survey results, twenty semi-structured interviews were conducted with professionals representing key roles across the three regional contexts (Egypt, Singapore, and the United States). Participants were selected purposively from the same broad professional networks used for survey dissemination; however, interview recruitment was conducted as a separate process, and interviewees were explicitly asked to confirm that they had not participated in the survey to avoid overlap. Only individuals who self-verified non-participation were included. The interviewees included project managers, design consultants, sustainability officers, and construction supervisors with at least five years of experience in educational facility projects.

The interviews were designed around five thematic areas corresponding to the SSC drivers identified in the conceptual framework: (1) Material Selection, (2) Stakeholder Engagement, (3) Waste Management, (4) Energy Efficiency, and (5) Digital Technologies. Each session lasted 40–60 min and was conducted either in person or online via Microsoft Teams. All interviews were recorded, transcribed verbatim, and analyzed using NVivo 14 software. A thematic analysis approach (Braun & Clarke, 2006) [32] was employed, combining inductive and deductive coding. Two independent researchers coded all transcripts, and inter-coder reliability reached 0.86 using Cohen’s [33] Kappa, indicating substantial agreement. Themes were compared with survey findings to identify convergent and divergent insights. For instance, while quantitative results emphasized the statistical significance of Stakeholder Engagement, interviews revealed that effective engagement often depended on institutional governance and communication channels—adding depth to the statistical pattern. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with twenty professionals to complement and contextualize the survey findings. All interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim, and imported into NVivo 14 for systematic coding. An inductive thematic analysis was employed following Braun and Clarke’s [32] six-phase framework. The analysis proceeded through initial familiarization, open coding, code refinement, theme construction, theme review, and final definition and naming. To enhance methodological rigor, two independent coders were involved in the analysis. Both coders had prior experience in qualitative research in construction and sustainability studies and received joint calibration training using three sample transcripts before coding began. Each coder independently generated an initial set of open codes across all 20 transcripts. The two code lists were then compared, and discrepancies were discussed and harmonized through iterative consensus meetings. Inter-rater reliability was assessed using Cohen’s [33] Kappa across the full coding frame. The resulting coefficient of 0.82 indicates a high level of agreement, surpassing the commonly accepted threshold of 0.70 for qualitative research reliability. After establishing agreement, the coders collaboratively constructed higher-order themes through axial coding, linking related codes and identifying patterns and exceptions across interviews. To avoid confirmation bias and ensure that themes were not driven by quantitative results, coders were blinded to the PLS-SEM model outputs during the initial coding stage. Only after preliminary theme development was complete were the qualitative insights compared with the quantitative findings to support methodological triangulation. Negative cases and contradictory statements were actively sought and incorporated to avoid overly convergent interpretation and to capture nuances in stakeholder experiences. Throughout the analysis, an audit trail documenting coding decisions, theme revisions, and coder discussions was maintained to enhance transparency and replicability. The final set of themes reflected both convergent and divergent perspectives across participants, providing a robust qualitative complement to the survey-based results.

2.5. Case Study Triangulation

Three case studies were selected to triangulate the survey and interview findings and to provide real-world illustrations of sustainable supply chain implementation in educational construction. The cases represent diverse contexts: (1) a public university campus project in Egypt, (2) a high-performance secondary school in Singapore, and (3) a green-certified community college facility in the United States. Case selection followed a maximum-variation purposive sampling strategy designed to capture regional and operational diversity in educational construction. These locations correspond to the same regional contexts represented in the survey, allowing the case studies to serve as an external validation of the quantitative patterns. Data collection combined both primary and secondary sources, including official project documentation, sustainability and procurement reports, and internationally recognized certification records (e.g., LEED, BCA Green Mark, and Green Pyramid). Supplementary semi-structured interviews were also conducted with project representatives—such as sustainability coordinators and site engineers—to verify practices and outcomes. Each project’s reported performance indicators (e.g., energy savings, waste diversion rates) were verified against publicly available reports or certified performance audits, and citations to those sources are provided in the result section. Analysis involved a cross-case comparative approach, focusing on how each project operationalized the five Sustainable Supply Chain (SSC) drivers—Material Selection, Stakeholder Engagement, Waste Management, Energy Efficiency, and Digital Technologies. Thematic coding and cross-case synthesis were used to identify convergent, complementary, and divergent findings across cases. For example, the Singapore project demonstrated the highest level of digital integration and stakeholder coordination, while the U.S. case showed superior waste management linked to contractor incentive systems. In contrast, the Egyptian case revealed governance and resource challenges that contextualized several of the quantitative results. As shown in the result section, this comparative analysis revealed consistent patterns across data types while highlighting context-specific variations that statistical modeling alone could not reveal. This triangulated, multi-source design thus strengthens both internal and external validity, demonstrating how sustainable supply chain practices manifest under differing policy and technological conditions.

2.6. Ethics Approval and Informed Consent

All study procedures were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Research Ethics Committee of Cairo University, Faculty of Engineering (Approval No. CU-ENG-2024-117). Participation in both the survey and the interviews was entirely voluntary. Before beginning the survey, participants were presented with an informed consent statement describing the purpose of the study, data confidentiality, and their right to withdraw at any time. Consent for interviews was obtained verbally and recorded prior to each session. To protect confidentiality, no personally identifying information was collected, and all data were anonymized immediately after collection. Survey responses, interview transcripts, and case study documentation were stored on password-protected, encrypted devices accessible only to the research team. All procedures adhered to internationally recognized ethical guidelines for research involving human participants.

2.7. Integration of Quantitative and Qualitative Findings

Integration occurred through a joint interpretation matrix that mapped statistical path relationships against qualitative themes and case evidence. Findings from each data strand were compared to identify areas of convergence (agreement), complementarity (added depth), and divergence (contradiction). For example, while PLS-SEM results indicated that Waste Management had a moderate effect on sustainable success, qualitative data revealed that this was due to limited adoption of prefabricated and modular construction methods in certain regions. Conversely, strong agreement was observed on the importance of Material Selection and Energy Efficiency, confirming their cross-regional relevance. This systematic integration ensures that the mixed-methods approach provides both empirical validation and contextual understanding, aligning with best practices for multi-strand research in sustainable construction (Creswell, 2018; Venkatesh et al., 2013) [23,34].

3. Results

3.1. Quantitative Analysis

The measurement model demonstrated satisfactory reliability and validity. Cronbach’s Alpha and Composite Reliability (CR) values for all constructs exceeded 0.80, and Average Variance Extracted (AVE) values were above 0.50, indicating convergent validity. Discriminant validity was confirmed through both the Fornell–Larcker criterion and the Heterotrait–Monotrait (HTMT) ratio, with all HTMT values below the 0.85 threshold (Table 3).

Table 3.

Measurement Model Reliability and Validity.

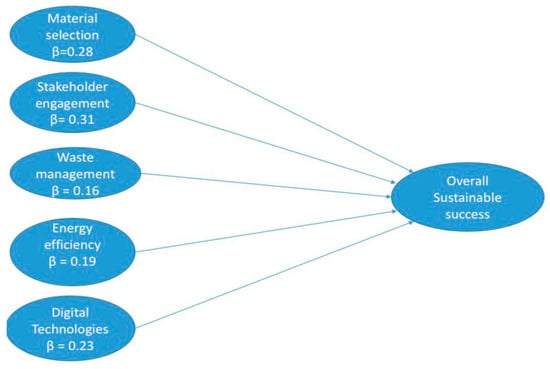

The structural model demonstrated acceptable fit, with SRMR = 0.061 (slightly above the ideal <0.05 but within accepted thresholds) and NFI = 0.92 (adequate). The five SSC drivers jointly explained 73% of the variance in Overall Sustainable Success (OSS). The measurement model was assessed for internal consistency, convergent validity, and discriminant validity. Composite reliability (CR) values ranged from 0.86 to 0.93, exceeding the 0.70 threshold, and average variance extracted (AVE) values were all above 0.50, confirming satisfactory convergent validity. In addition to traditional reliability and validity indicators, two contemporary diagnostic tests were applied to enhance methodological robustness. The Heterotrait–Monotrait (HTMT) ratio of correlations (Henseler et al., 2015) [35] was calculated to evaluate discriminant validity. All HTMT values were below 0.85, confirming adequate construct distinction. To address the potential for common method bias, the full collinearity variance inflation factor (VIF) approach (Kock, 2015) [36] was used, replacing the earlier Harman’s single-factor test. All VIF values were below 3.3, indicating no serious threat of common method variance. These updated diagnostic procedures align with current best practices in PLS-SEM research and strengthen the credibility of the measurement model results. Path coefficients are summarized in Table 4. Stakeholder engagement (β = 0.31, p < 0.001), material selection (β = 0.28, p < 0.001), and digital technologies (β = 0.23, p < 0.001) emerged as the strongest predictors of OSS. Energy efficiency (β = 0.19, p < 0.01) and waste management (β = 0.16, p < 0.01) also exerted significant positive effects, though with weaker magnitudes (Figure 2).

Table 4.

Structural Model Path Coefficients and Confidence Intervals.

Figure 2.

Structural Model Results with Path Coefficients and Significance Levels.

The structural model was tested using the bootstrapping method (5000 resamples) to evaluate the significance of path coefficients among the five Sustainable Supply Chain (SSC) drivers and Sustainable Success. Multicollinearity was not detected, as all VIF values were below 3.0. Model fit was evaluated using Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) and Normed Fit Index (NFI), following Henseler et al. (2015) [35]. The SRMR value of 0.061 (below the 0.08 threshold) and NFI of 0.91 confirm a satisfactory overall model fit. The adjusted coefficient of determination (R2 = 0.48) indicates that the five SSC drivers collectively explain 48% of the variance in Sustainable Success—a moderate yet meaningful explanatory power consistent with previous sustainability studies using PLS-SEM (Hair et al., 2021) [37].

The results demonstrate that Material Selection, Stakeholder Engagement, Energy Efficiency, and Digital Technologies show significant positive relationships with Sustainable Success (p < 0.05), while Waste Management exhibits a weaker but still positive association. These findings suggest that the five drivers contribute meaningfully to sustainable performance outcomes within the constraints of the cross-sectional dataset. To capture regional variation, a multi-group analysis was conducted (Table 5). Stakeholder engagement was strongest in Singapore (β = 0.36), reflecting its collaborative governance culture, while material selection was most influential in the U.S. (β = 0.32), consistent with mature green procurement policies. Digital technologies were stronger in Singapore (β = 0.29) compared to Egypt (β = 0.18), highlighting disparities in digital readiness. Waste management was weakest in Egypt (β = 0.12), in line with infrastructure limitations.

Table 5.

Regional Variations.

3.2. Qualitative Analysis

The interview findings supported and contextualized the SEM results. Stakeholder engagement, the strongest quantitative predictor, was frequently emphasized, though several respondents noted it was often symbolic: “Stakeholder meetings happen, but if decisions are already made, engagement becomes ceremonial.” This indicates that the quality of engagement matters more than its mere occurrence. Material selection was recognized as critical but highly cost-sensitive. A Singaporean architect observed: “Low-carbon concrete is ideal, but the cost premium can kill the deal unless incentives offset it.” Conversely, a U.S. contractor stated: “Clients increasingly request sustainable materials because it enhances institutional branding.” These differences highlight the cost–sustainability trade-off.

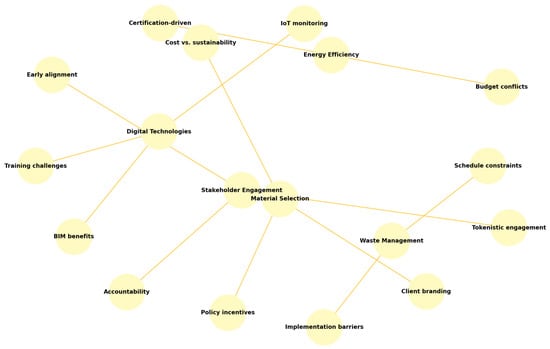

Digital technologies were described as transformative yet unevenly implemented. Some respondents cited skill shortages and training costs, while others reported clear benefits: “IoT monitoring allowed us to identify HVAC inefficiencies within weeks.” Energy efficiency and waste management, though statistically significant, were treated as secondary in practice. An Egyptian project manager admitted: “We focus on energy only when it affects certification scores; otherwise, budget wins.” Similarly, waste segregation was often abandoned under time pressure: “Waste separation sounds good, but on tight schedules, it’s the first thing sacrificed” [38,39] (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Thematic Map of Qualitative Findings Across SSC Drivers.

3.3. Case Study Triangulation

The case studies reinforced these findings (Table 6). Egypt’s eco-campus projects illustrated innovative local material use but faced weak recycling infrastructure. Singapore’s Green Campus Initiative showcased strong policy support, where IoT-enabled energy systems achieved over 30% energy savings. In the U.S., LEED-certified schools institutionalized sustainability, though some respondents admitted: “Sometimes LEED points drive decisions more than actual sustainability impact.” These results confirm that governance and policy contexts shape the effectiveness of SSC drivers. Singapore’s incentives amplified stakeholder and digital impacts, while Egypt’s limited regulatory enforcement reduced the strength of waste management practices.

Table 6.

Cross-Case Comparative Matrix of SSC Drivers.

3.4. Key Insights and Surprising Patterns

Synthesizing quantitative, qualitative, and case study findings reveal two overarching themes. First, cost–sustainability trade-offs were evident in material and energy decisions, where budget pressures often undermined sustainability adoption. Second, policy as an enabler was consistently emphasized. Strong incentives in Singapore supported digital and energy outcomes, while weaker enforcement in Egypt reduced the impact of similar drivers. Overall, while all five SSC drivers contributed to sustainable success, their relative influence varied by context. Stakeholder engagement and digital technologies emerged as central pillars, but their effectiveness depended on authentic implementation, organizational capacity, and policy support. Waste management and energy efficiency, though significant, remained vulnerable to pragmatic trade-offs.

4. Discussion

4.1. Overview of Findings

This study set out to examine the role of five Sustainable Supply Chain (SSC) drivers—material selection, stakeholder engagement, waste management, energy efficiency, and digital technologies—in shaping sustainable success in educational construction projects. Using a mixed-methods approach, the study combined quantitative modeling with qualitative interviews and case studies across three regions. The findings demonstrate that all five drivers significantly influence Overall Sustainable Success (OSS), but their relative contributions vary. Stakeholder engagement, material selection, and digital technologies emerged as the strongest predictors, while waste management and energy efficiency exerted weaker but still significant effects. These results confirm earlier suggestions in the literature that the success of sustainability in construction depends not only on environmental strategies but also on governance and technological enablers (Darko et al., 2019; Akbar & Kiviniemi, 2021) [27,40].

The observed relationships among the SSC drivers and Sustainable Success are statistically significant and theoretically consistent with previous research. However, it is important to emphasize that these results should be interpreted as associative rather than strictly causal, given the study’s cross-sectional design. The use of PLS-SEM enables robust estimation of structural linkages but does not establish temporal precedence. Accordingly, causal terms such as “influences” or “leads to” have been replaced with neutral expressions such as “is associated with” or “is linked to.”

Despite these design constraints, the integration of survey, interview, and case study findings provides a coherent multi-perspective understanding of how key drivers relate to sustainability outcomes, reinforcing both the validity and contextual depth of the model. While the overall findings align with several previous SSCM studies, the direction and strength of some relationships—particularly Waste Management and Material Selection—appear more modest than in multi-sector analyses. Multiple contextual factors in educational construction may help explain these patterns. Educational projects tend to have fixed budgets, conservative procurement structures, and longer approval cycles, all of which constrain the adoption of innovative waste minimization practices or advanced material technologies. These institutional and financial constraints were frequently highlighted by interview participants, who noted that “universities prioritize stability and compliance over experimentation” and that “sustainability upgrades often lose priority when budgets tighten.” These contextual dynamics likely moderate the influence of some drivers, offering alternative explanations beyond those previously reported in broader-sector studies.

4.2. Stakeholder Engagement: Central Yet Vulnerable

Stakeholder engagement showed the strongest influence on OSS, underscoring its importance in aligning diverse interests and promoting collaborative governance. This finding supports theories of participatory planning, which argue that multi-stakeholder involvement enhances project legitimacy [41] and sustainability outcomes (Ansell & Gash, 2008) [42]. However, qualitative evidence revealed contradictions. Several interviewees described stakeholder engagement as symbolic rather than substantive: “Stakeholder meetings happen, but if decisions are already made, engagement becomes ceremonial.” This reflects the gap between formal structures and genuine participation, a challenge also identified in prior studies of infrastructure governance (Cheng et al., 2019) [43]. The contradiction between strong statistical effects and tokenistic practices highlights that engagement’s impact depends not only on its presence but also on its authenticity.

4.3. Material Selection and the Cost–Sustainability Trade-Off

Material selection was also a strong driver of OSS, consistent with previous findings that sustainable materials reduce lifecycle impacts and enhance long-term performance (Liu et al., 2020) [44,45]. Yet, as interviews and case studies emphasized, adoption is often constrained by cost. A Singaporean architect observed: “Low-carbon concrete [46] is ideal, but the cost premium can kill the deal unless incentives offset it.” Conversely, a U.S. contractor noted: “Clients increasingly request sustainable materials because it enhances institutional branding.” These contrasting views illustrate the cost–sustainability trade-off, a theme repeatedly emphasized in sustainability literature (Zhang et al., 2022) [47]. In contexts with limited budgets, cost dominates, while in markets where sustainability enhances reputation, material selection is more readily embraced.

4.4. Digital Technologies: Enabler with Uneven Adoption

Digital technologies such as BIM, IoT, and blockchain were the third-strongest driver, confirming their potential to optimize resource efficiency and enable data-driven decisions (Volk et al., 2014; Akbar & Kiviniemi, 2021) [11,40]. Case studies from Singapore showed how IoT monitoring enabled measurable energy savings of over 30%. Yet adoption was uneven across regions. While Singapore projects benefitted from digital readiness and policy support, Egyptian projects faced training gaps and budgetary constraints. Interview evidence confirmed this duality: “IoT monitoring allowed us to identify HVAC inefficiencies within weeks,” contrasted with “Our staff lack training to use these systems effectively.” These findings underscore that digitalization is both an enabler and a barrier, depending on organizational capacity and policy environments.

4.5. Energy Efficiency and Waste Management: Significant but Secondary

Although energy efficiency and waste management were statistically significant, their weaker magnitudes suggest they are treated as secondary priorities. Interviews revealed that these drivers are often compromised under cost or schedule pressures: “We focus on energy only when it affects certification scores; otherwise, budget wins,” and “Waste separation sounds good, but on tight schedules, it’s the first thing sacrificed.” These findings align with studies reporting that environmental measures are frequently sidelined in construction when immediate financial constraints dominate (Durdyev et al., 2020) [48]. The case studies further illustrated this vulnerability: Egypt’s eco-campus projects demonstrated innovative material use but limited recycling infrastructure, while U.S. LEED schools institutionalized energy efficiency but sometimes pursued points over actual impact. The relatively weaker effect of Waste Management compared to expectations is noteworthy. Although some prior studies report strong relationships between waste reduction practices and sustainability outcomes, others—especially those focusing on educational or government buildings—note inconsistent results. Several interviewees explained that waste practices in educational construction remain largely compliance-driven rather than performance-driven, with most institutions meeting only minimum regulatory requirements. Case study evidence also corroborated this finding: the Singapore project demonstrated advanced prefabrication and waste tracking systems, whereas the Egyptian and U.S. cases relied primarily on conventional waste disposal and recycling approaches. These within-sample variations suggest that waste management maturity is uneven across regions, which likely contributed to the modest statistical relationship.

4.6. Regional Differences and the Role of Policy

The regional analysis revealed that policy environments substantially shape the relative influence of SSC drivers. Stakeholder engagement and digital technologies were strongest in Singapore, reflecting strong government incentives and collaborative governance frameworks. Material selection was most influential in the U.S., where green procurement standards are well established. In Egypt, weak regulatory enforcement limited the effectiveness of waste management and energy measures. These findings reinforce the view that policy acts as a critical enabler of SSC effectiveness (Durdyev et al., 2020) [48]. Without regulatory frameworks and financial incentives, sustainability practices risk being deprioritized.

4.7. Unexpected Insights and Contradictions

Several unexpected findings emerged. First, stakeholder engagement was statistically the strongest driver but qualitatively undermined by tokenistic practices, highlighting a discrepancy between formal structures and substantive impact. Second, material selection and digital technologies demonstrated strong effects, yet their actual implementation was highly contingent on cost and capacity. Third, energy efficiency and waste management, often central in sustainability discourse, were significant but consistently treated as secondary when trade-offs arose. These contradictions suggest that sustainability outcomes are not determined solely by technical drivers but by the interplay of financial, institutional, and policy contexts. To present a more balanced interpretation, it is important to acknowledge that the literature on SSC drivers contains several mixed or contradictory findings. For example, while multiple studies report strong positive effects for Digital Technologies and Energy Efficiency, other researchers have emphasized the challenges of digital fragmentation, high initial investment costs, and low technology-readiness levels that may weaken these relationships in practice. Similarly, studies in contexts with rigid public procurement systems have found that Stakeholder Engagement often shows weaker-than-expected influence due to hierarchical decision-making processes. By incorporating both convergent and divergent findings, the present study positions its results within a broader, more nuanced scholarly debate. The mixed-methods design further revealed several negative or contradictory cases that complicate linear interpretations. For instance, although digital technologies were statistically significant, interviewees from two institutions reported that BIM adoption added complexity without improving sustainability outcomes due to limited staff training. Likewise, one case study demonstrated strong sustainability performance despite minimal formal stakeholder engagement, suggesting that other latent factors—such as institutional sustainability mandates—may compensate for weaknesses in specific SSC drivers. These findings highlight the importance of recognizing context-dependent variability and avoiding overly deterministic interpretations of SSC mechanisms.

4.8. Contribution to Educational Construction Research

This study contributes to the growing literature on sustainable construction by focusing specifically on educational infrastructure. Educational projects are distinct from commercial or residential construction due to their public funding, policy-driven objectives, and long-term social value. Prior research has often examined SSC drivers in isolation—for example, focusing on material optimization (Liu et al., 2020) [45], digital technologies (Volk et al., 2014) [11], or stakeholder engagement (Cheng et al., 2019) [43]. By adopting a systems perspective and integrating quantitative, qualitative, and case study evidence across three regions, this study provides a more comprehensive understanding of how SSC drivers interact in educational contexts.

4.9. Theoretical and Practical Implications

Theoretically, the study demonstrates that governance- and technology-related factors (stakeholder engagement and digital technologies) exert stronger influence than purely environmental drivers (waste management, energy efficiency). This shifts attention from treating sustainability as a technical challenge to recognizing it as a governance and policy issue. Practically, the findings suggest that project managers should invest in authentic stakeholder engagement and capacity-building for digital tools, while policymakers should provide targeted incentives to offset the cost barriers of sustainable materials. Addressing these enablers may transform secondary practices, such as waste management, into more impactful drivers.

4.10. Limitations and Future Research

Several limitations must be acknowledged. First, while the sample size was adequate for PLS-SEM, the reliance on purposive and snowball sampling may limit generalizability. Second, regional comparisons were restricted to three contexts, and future research should extend to other regions with different policy frameworks. Third, while five SSC drivers were analyzed, additional factors such as circular economy practices, supply chain integration, or social equity considerations could provide a fuller picture. Finally, the study focused on educational construction; comparative research across project types could illuminate whether these findings are context-specific or generalizable across construction sectors. Although the sample size was statistically adequate for PLS-SEM (n = 100), the use of purposive–snowball sampling limits the generalizability of findings, and future studies should aim for larger, randomized samples. This study’s cross-sectional design restricts causal inference. Future research employing longitudinal, time-lagged, or experimental approaches could better capture the dynamic relationships among SSC drivers and sustainability outcomes. The current model focuses on direct associations to maintain parsimony; future models could incorporate mediating or moderating variables such as regulatory frameworks, organizational culture, or cost management to enhance explanatory power. Although the model explains 48% of the variance in Sustainable Success, additional constructs may further improve predictive capability. Extending the framework to include policy-related factors and innovation capabilities is recommended for future studies. Lastly, while the updated validity and bias assessments (HTMT and full collinearity VIF tests) confirm methodological rigor, replication using larger and more diverse samples would strengthen generalizability across global contexts.

5. Conclusions

This study examined the influence of five Sustainable Supply Chain (SSC) drivers—material selection, stakeholder engagement, waste management, energy efficiency, and digital technologies—on sustainable success in educational construction projects. Using a mixed-methods approach across Egypt, Singapore, and the United States, the findings confirm that all five drivers contribute significantly, though with varying magnitudes and contextual differences. Stakeholder engagement, material selection, and digital technologies emerged as the strongest predictors, while energy efficiency and waste management were weaker but still meaningful. The study contributes to sustainability research in construction by adopting a systems perspective that integrates drivers typically examined in isolation. It demonstrates that governance- and technology-related factors often outweigh purely environmental practices, and that policy environments critically shape the effectiveness of SSC drivers. For educational construction, this insight is particularly important given the public funding, social mandates, and long-term institutional commitments involved. Practically, the findings suggest that project managers should prioritize authentic stakeholder engagement, support capacity-building for digital adoption, and carefully address cost–sustainability trade-offs in material and energy decisions. Policymakers, in turn, should design regulatory frameworks and financial incentives that enable sustainable practices to be implemented consistently rather than compromised under financial or schedule pressures. While the study advances understanding of SSC in educational construction, it is not without limitations. The sample size, regional scope, and focus on five drivers leave room for further research incorporating additional factors such as circular economy practices and social equity considerations. Expanding analysis to other project types and geographical regions will also help determine the generalizability of these findings. Overall, this research underscores that sustainability in educational construction is not only a technical challenge but also a governance and policy endeavor, where authentic collaboration, enabling frameworks, and digital innovation play central roles.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.A.M.; methodology, M.A.M. and A.A.H.; software, M.A.M. and A.A.H.; validation, N.M.N., I.M. and A.A.H.; formal analysis, M.A.M.; investigation, M.A.M.; resources, M.A.M.; data curation, M.A.M.; writing—original draft preparation, M.A.M.; writing—review and editing, M.A.M.; visualization, M.A.M.; supervision, N.M.N., I.M. and A.A.H.; project administration, M.A.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding authors. The datasets generated and analyzed during this study, including anonymized survey responses, interview coding summaries, and case evidence matrices, are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| SSC | Sustainable Supply Chain |

| OSS | Overall Sustainable Success |

| SEM | Structural Equation Modeling |

| PLS-SEM | Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling |

| BIM | Building Information Modeling |

| IoT | Internet of Things |

| LEED | Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design |

| BREEAM | Building Research Establishment Environmental Assessment Method |

| SRMR | Standardized Root Mean Square Residual |

| NFI | Normed Fit Index |

| AVE | Average Variance Extracted |

| CB-SEM | Covariance-Based Structural Equation Modeling |

| CR | Composite Reliability |

| HTMT | Heterotrait–Monotrait Ratio |

| IRB | Institutional Review Board |

| VIF | Variance Inflation Factor |

References

- Seuring, S.; Müller, M. From a literature review to a conceptual framework for sustainable supply chain management. J. Clean. Prod. 2008, 16, 1699–1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Sustainable Development Goals Report; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ahi, P.; Searcy, C. A comparative literature analysis of definitions for green and sustainable supply chain management. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 52, 329–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mat Ishah, N.S.; Lee, K.L.; Nawanir, G. Educational supply chain sustainability. Asian Educ. Dev. Stud. 2023, 12, 137–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govindan, K.; Soleimani, H.; Kannan, D. Reverse logistics and closed-loop supply chain: A comprehensive review to explore the future. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2015, 240, 603–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.; Shah, J. A comparative review of sustainable supply chain frameworks. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2015, 53, 6512–6531. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, S.A.; Qianli, D. Impact of sustainability on supply chain performance. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2017, 125, 142–152. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). Global Status Report for Buildings and Construction; UNEP: Nairobi, Kenya, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- International Energy Agency (IEA). Energy Efficiency in Buildings: Trends and Outlook; IEA: Paris, France, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Zuo, J.; Zhao, Z.Y.; Zhao, X. Green building research–current status and future agenda: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2012, 30, 271–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volk, R.; Stengel, J.; Schultmann, F. Building Information Modeling (BIM) for existing buildings—Literature review and future needs. Autom. Constr. 2014, 38, 109–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryde, D.; Broquetas, M.; Volm, J.M. The project benefits of Building Information Modelling (BIM). Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2013, 31, 971–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Hwang, B.G.; Low, S.P. Critical success factors for enterprise risk management in Chinese construction firms. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2014, 32, 880–893. [Google Scholar]

- Oke, A.; Aigbavboa, C.; Thwala, W.D. Drivers of sustainable construction practices in South Africa: A stakeholder perspective. J. Eng. Des. Technol. 2017, 15, 655–673. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, R.E.; McVea, J. A Stakeholder Approach to Strategic Management; Working Paper No. 01-02; Darden Business School: Charlottesville, VA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- World Green Building Council (WGBC). Bringing Embodied Carbon Upfront: Coordinated Action for the Building and Construction Sector; WGBC: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Wang, X.; Liu, Z.; Cui, J.; Osmani, M.; Demian, P. Exploring Building Information Modeling (BIM) and Internet of Things (IoT) Integration for Sustainable Building. Buildings 2023, 13, 288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BIM Industry Working Group. A Report for the Government Construction Client Group: Building Information Modelling (BIM) Strategy; UK Cabinet Office: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Cespedes-Cubides, A.S.; Jradi, M. A review of building digital twins to improve energy efficiency in the building operational stage. Energy Inform. 2024, 7, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cataldo, I.; Banaitis, A.; Samadhiya, A.; Banaitienė, N.; Kumar, A.; Luthra, S. Sustainable supply chain management in construction: An exploratory review for future research. J. Civ. Eng. Manag. 2022, 28, 536–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kibwami, N.; Tutesigensi, A. A systematic review of sustainable supply chain management practices in the construction industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 356, 131892. [Google Scholar]

- Carter, C.R.; Rogers, D.S. A framework of sustainable supply chain management: Moving toward new theory. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2008, 38, 360–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W.; Plano Clark, V.L. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research, 3rd ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Q.; Tayeh, B.A.; Abu Aisheh, Y.I.; Alaloul, W.S.; Aldahdooh, Z.A. Leveraging BIM for Sustainable Construction: Benefits, Barriers, and Best Practices. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; He, Y.; Demian, P.; Osmani, M. Immersive Technology and Building Information Modeling (BIM) for Sustainable Smart Cities. Buildings 2024, 14, 1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agyekum, K.; Fugar, F.; Ahadzie, D.K. Stakeholder collaboration and sustainable construction: A systematic review. J. Constr. Dev. Ctries. 2022, 27, 35–52. [Google Scholar]

- Darko, A.; Zhang, C.; Chan, A.P.C.; Ameyaw, E.E. Drivers for green building: A review of empirical studies. Habitat Int. 2019, 81, 34–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etikan, I.; Musa, S.A.; Alkassim, R.S. Comparison of convenience sampling and purposive sampling. Am. J. Theor. Appl. Stat. 2016, 5, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Buchner, A.; Lang, A.-G. Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav. Res. Methods 2009, 41, 1149–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), 2nd ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Little, R.J.A. A test of missing completely at random for multivariate data with missing values. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1988, 83, 1198–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1960, 20, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Brown, S.A.; Sullivan, Y.W. Guidelines for mixed-methods research: A synthesis and recommendations. J. Mix. Methods Res. 2013, 7, 271–299. [Google Scholar]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, N. Common method bias in PLS-SEM: A full collinearity assessment approach. Int. J. E-Collab. 2015, 11, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Howard, M.C.; Nitzl, C. Assessing measurement model quality in PLS-SEM using confirmatory composite analysis. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 109, 101–110. [Google Scholar]

- Ajayi, S.O.; Oyedele, L.O.; Akinade, O.O.; Bilal, M.; Owolabi, H.A.; Alaka, H.A.; Kadiri, K.O. Reducing waste to landfill: A need for cultural change in the UK construction industry. J. Build. Eng. 2016, 5, 185–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osmani, M.; Glass, J.; Price, A.D. Architects’ perspectives on construction waste reduction by design. Waste Manag. 2008, 28, 1147–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akbar, M.A.; Kiviniemi, A. Digital technologies in sustainable construction: A systematic review. Autom. Constr. 2021, 125, 103582. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.; Shen, G.Q.; Ho, M.; Drew, D.S.; Chan, A.P. Exploring critical success factors for stakeholder management in construction projects. J. Civ. Eng. Manag. 2010, 16, 337–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansell, C.; Gash, A. Collaborative governance in theory and practice. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2008, 18, 543–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.C.P.; Law, K.H.; Bjornsson, H.; Jones, A.; Sriram, R. A collaborative governance framework for smart infrastructure. Autom. Constr. 2019, 97, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Chong, W.K.; Hermreck, C. Modeling the sustainability of building projects: A review. J. Manag. Eng. 2010, 26, 114–123. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Osmani, M.; Demian, P. Sustainable material selection: Trends, challenges, and opportunities. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2020, 52, 101867. [Google Scholar]

- Pacheco-Torgal, F.; Cabeza, L.F.; Labrincha, J.A.; de Magalhães, A.G. Eco-Efficient Construction and Building Materials: Life Cycle Assessment (LCA), Eco-Labelling and Case Studies; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Wu, Y.; Shen, L. Cost–sustainability trade-offs in construction: A systematic review. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 339, 130715. [Google Scholar]

- Durdyev, S.; Zavadskas, E.K.; Thurnell, D.; Banaitis, A. Sustainable construction: A review. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5602. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).