Microplastic Accumulation in Commercially Important Black Sea Fish and Shellfish: European Sprat (Sprattus sprattus), Mussels (Mytilus galloprovincialis) and Rapa Whelks (Rapana venosa)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

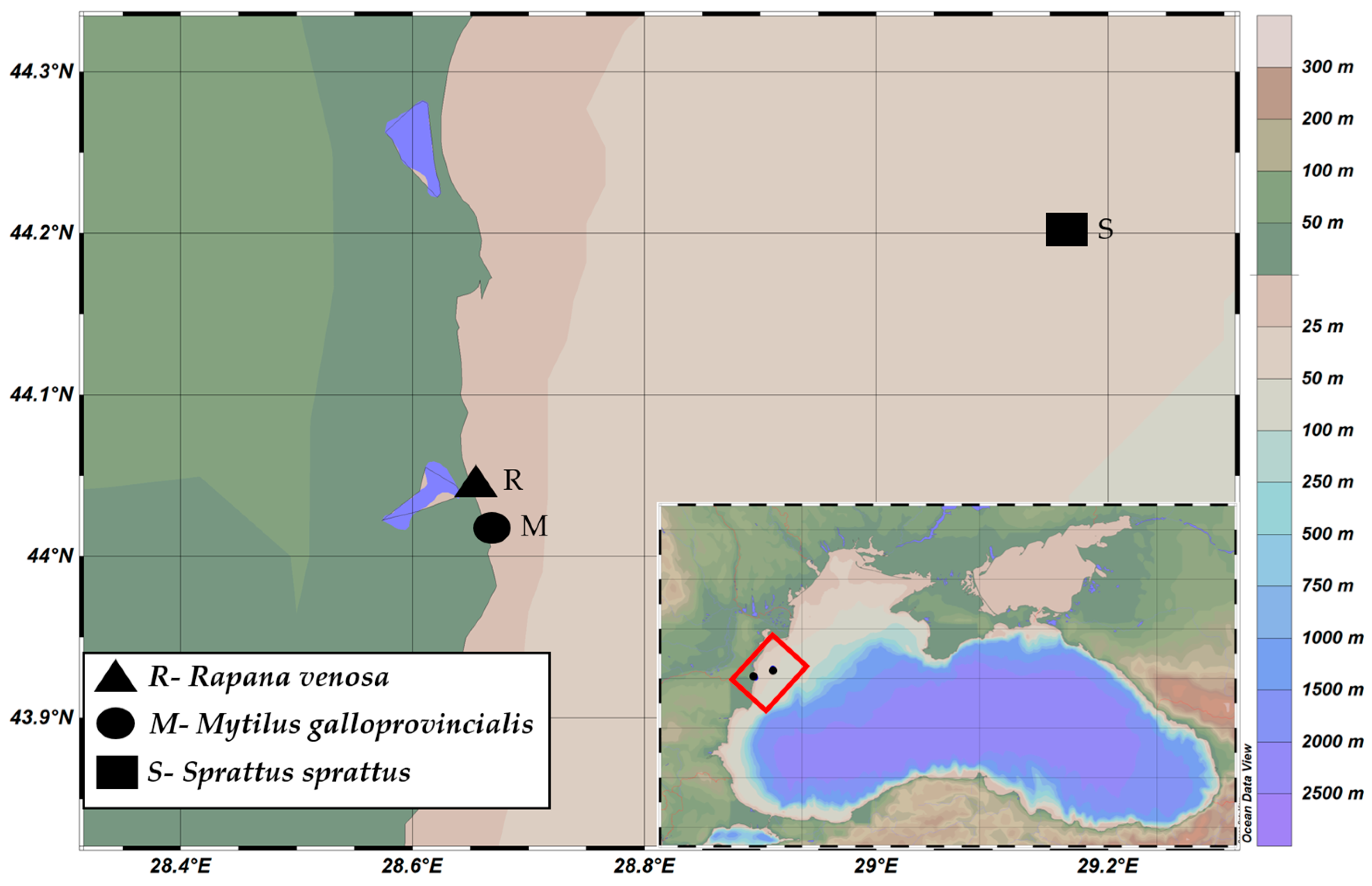

2.1. Specimen Collection

2.2. Sample Preparation and Microplastics Identification

2.3. Quality Assurance and Quality Control Measures

2.4. Statistical Analysis

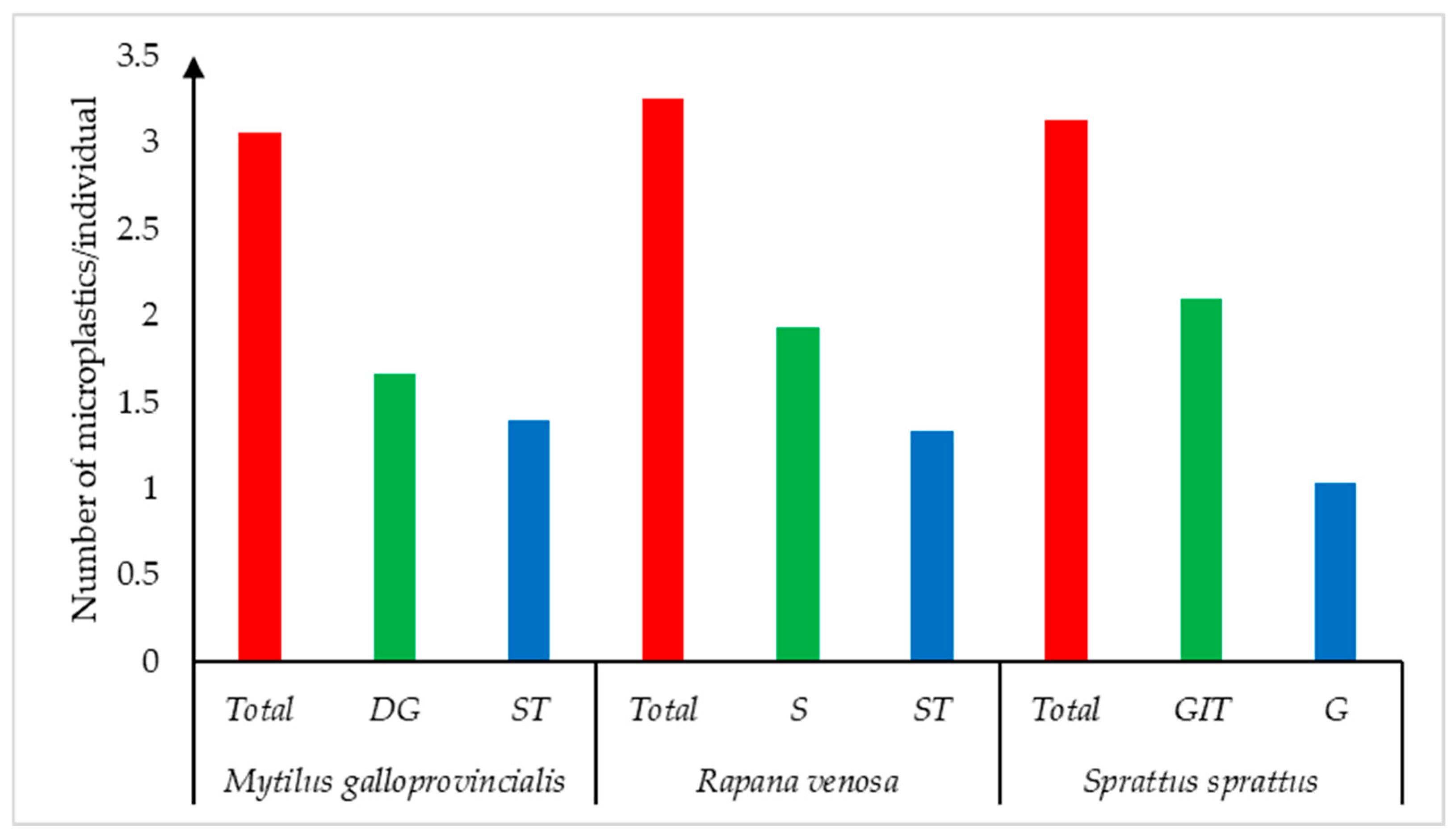

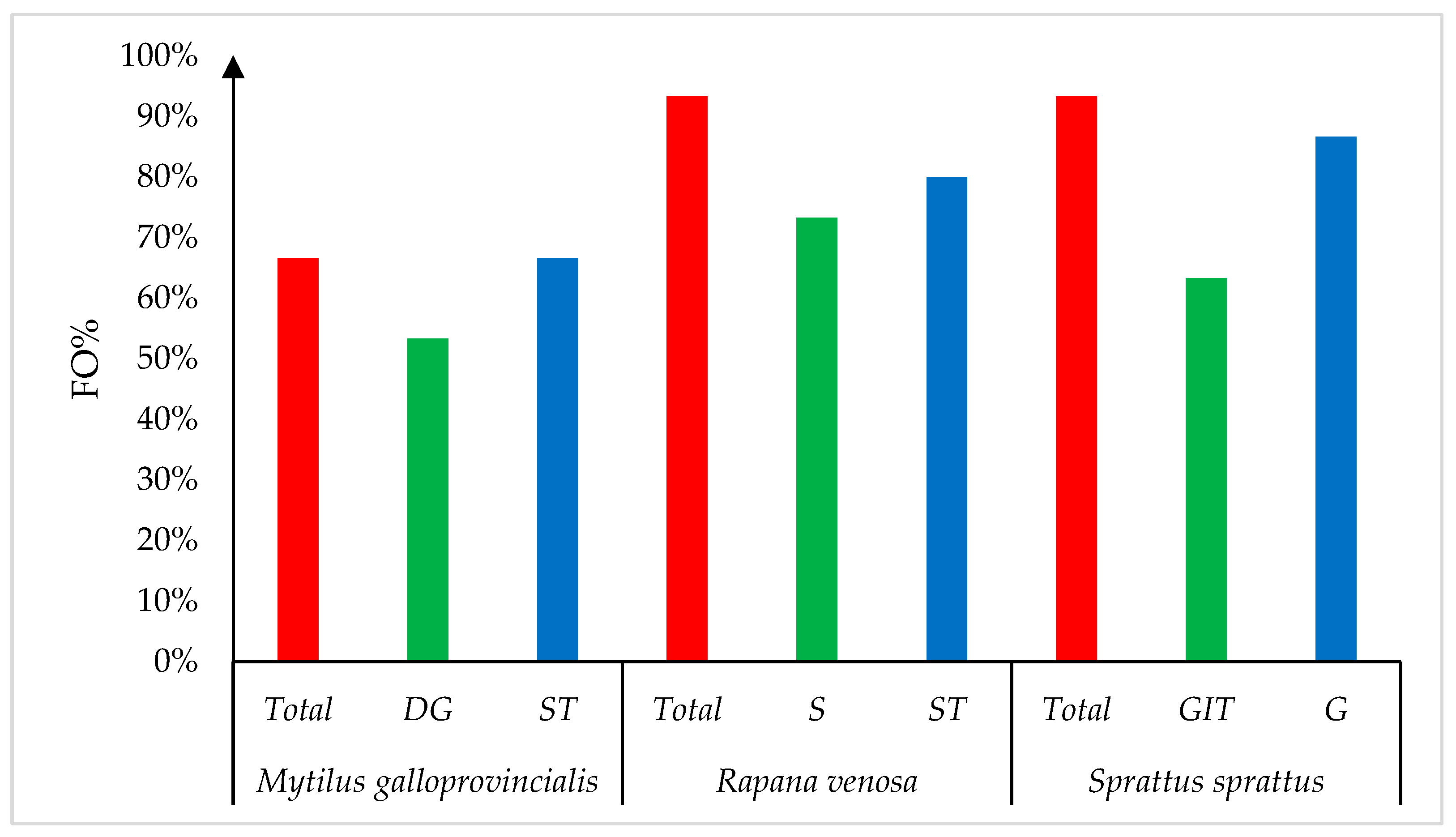

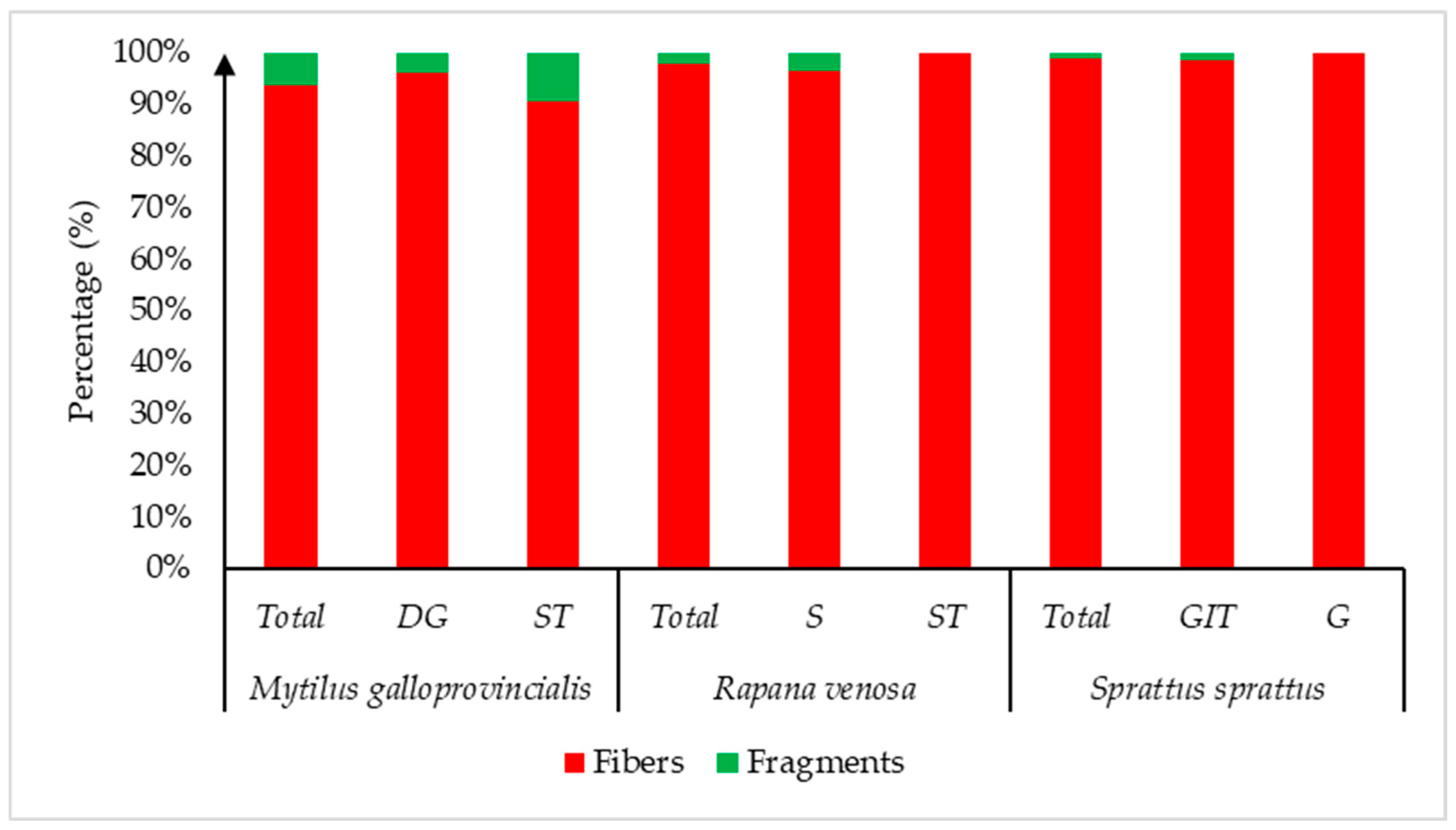

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| KOH | Potassium hydroxide |

| FO | Frequency of occurrence |

| PAH | Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons |

| PCB | Polychlorinated Biphenyls |

| QA/QC | Quality assurance and quality control |

| PET | Polyethylene terephtatale |

| PP | Polypropylene |

| PS | Polystyrene |

| DG | Digestive gland |

| ST | Soft tissue |

| S | Stomach |

| GIT | Gastrointestinal tract |

| G | Gills |

| N/A | Not Applicable |

| ANOVA | Analysis of Variance |

References

- Von Schuckmann, K.; Gues, F.; Moreira, L.; Liné, A.; de Pascual Collar, Á. Global Ocean Change in the Era of the Triple Planetary Crisis. State Planet 2025, 6-osr9, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Environment Programme Making Peace with Nature: A Scientific Blueprint to Tackle the Climate, Biodiversity and Pollution Emergencies. UN Environment Programme: Nairobi, Kenya, 2021. Available online: https://www.unep.org/resources/making-peace-nature (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Pinto da Costa, J.; Rocha-Santos, T.; Duarte, A.C. The Environmental Impacts of Plastics and Micro-Plastics Use, Waste and Pollution: EU and National Measures; European Parliament: Brussels, Belgium, 2020; Available online: http://www.europarl.europa.eu/supporting-analyses (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Plastics: Material-Specific Data; EPA: Washington, DC, USA, 2024. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/facts-and-figures-about-materials-waste-and-recycling/plastics-material-specific-data (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Arthur, C.; Baker, J.; Bamford, H. Proceedings of the International Research Workshop on the Occurrence, Effects, and Fate of Microplastic Marine Debris; NOAA Technical Memorandum NOS-OR&R-30; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bhat, M.A.; Gaga, E.O. Unveiling the Invisible: First Discovery of Micro- and Nanoplastic Size Segregation in Indoor Commercial Markets Using a Cascade Impactor. Air Qual. Atmos. Health 2025, 18, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cverenkárová, K.; Valachovičová, M.; Mackuľak, T.; Žemlička, L.; Bírošová, L. Microplastics in the Food Chain. Life 2021, 11, 1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelms, S.E.; Galloway, T.S.; Godley, B.J.; Jarvis, D.S.; Lindeque, P.K. Investigating Microplastic Trophic Transfer in Marine Top Predators. Environ. Pollut. 2018, 238, 999–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Au, S.Y.; Lee, C.M.; Weinstein, J.E.; van den Hurk, P.; Klaine, S.J. Trophic Transfer of Microplastics in Aquatic Ecosystems: Identifying Critical Research Needs. Integr. Environ. Assess. Manag. 2017, 13, 505–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Cauwenberghe, L.; Devriese, L.; Galgani, F.; Robbens, J.; Janssen, C.R. Microplastics in Sediments: A Review of Techniques, Occurrence and Effects. Mar. Environ. Res. 2015, 111, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Yuan, J.; Huang, Q.; Liu, R.; Yang, Y.; Yang, X.; Wang, K. A Review of Sources, Hazards, and Removal Methods of Microplastics in the Environment. Water 2025, 17, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Tan, Z.; Peng, J.; Qiu, Q.; Li, M. The Behaviors of Microplastics in the Marine Environment. Mar. Environ. Res. 2016, 113, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stanev, E.V.; Ricker, M. The Fate of Marine Litter in Semi-Enclosed Seas: A Case Study of the Black Sea. Front. Mar. Sci. 2019, 6, 660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öztekin, A.; Üstün, F.; Bat, L.; Tabak, A. Microplastic Contamination of the Seawater in the Hamsilos Bay of the Southern Black Sea. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2024, 235, 325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berov, D.; Klayn, S. Microplastics and Floating Litter Pollution in Bulgarian Black Sea Coastal Waters. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2020, 156, 111225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terzi, Y.; Gedik, K.; Eryaşar, A.R.; Öztürk, R.Ç.; Şahin, A.; Yılmaz, F. Microplastic Contamination and Characteristics Spatially Vary in the Southern Black Sea Beach Sediment and Sea Surface Water. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2022, 174, 113228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akkan, T.; Gedik, K.; Mutlu, T. Protracted Dynamicity of Microplastics in the Coastal Sediment of the Southeast Black Sea. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2023, 188, 114722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekova, R.; Prodanov, B. Spatiotemporal Variation in Marine Litter Distribution along the Bulgarian Black Sea Sandy Beaches: Amount, Composition, Plastic Pollution, and Cleanliness Evaluation. Front. Mar. Sci. 2024, 11, 1416134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aytan, U.; Esensoy, F.B.; Senturk, Y. Microplastic Ingestion and Egestion by Copepods in the Black Sea. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 806, 150921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eryaşar, A.R.; Gedik, K.; Mutlu, T. Ingestion of Microplastics by Commercial Fish Species from the Southern Black Sea Coast. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2022, 177, 113535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciucă, A.-M.; Manea, M.; Barbeş, L.; Stoica, E. Marine Birds’ Plastic Ingestion: A First Study at the Northwestern Black Sea Coast. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2025, 313, 109032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihova, S.; Doncheva, V.; Stefanova, K.; Stefanova, E.; Popov, D.; Panayotova, M. Plastic Ingestion by Phocoena phocoena and Tursiops truncatus from the Black Sea. In Environmental Protection and Disaster Risks; Dobrinkova, N., Nikolov, O., Eds.; EnviroRISKs 2022, Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; Volume 638, pp. 295–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexandrova, A.; Mihova, S.; Tsvetanova, E.; Andreeva, M.; Pramatarov, G.; Petrov, G.; Chipev, N.; Doncheva, V.; Stefanova, K.; Grandova, M.; et al. Distribution and Uptake of Microplastics in Key Species of the Bulgarian Black Sea Ecosystem and Their Effects from a Stress Ecology Viewpoint. Preprints 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibryamova, S.; Toschkova, S.; Bachvarova, D.C.; Lyatif, A.; Stanachkova, E.; Ivanov, R.; Natchev, N.; Ignatova-Ivanova, T. Assessment of the bioaccumulation of microplastics in the Black Sea mussel Mytilus galloprovincialis L., 1819. J. IMA-Annu. Proceeding Sci. Pap. 2022, 28, 4676–4682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexandrova, A.; Mihova, S.; Tsvetanova, E.; Andreeva, M.; Pramatarov, G.; Petrov, G.; Chipev, N.; Doncheva, V.; Stefanova, K.; Grandova, M.; et al. Microplastic Bioaccumulation and Oxidative Stress in Key Species of the Bulgarian Black Sea: Ecosystem Risk Early Warning. Microplastics 2025, 4, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pojar, I.; Dobre, O.; Baboș, T.; Lazăr, C. Quantitative Microfiber Evaluation in Mytilus Galloprovincialis, Western Black Sea, Romania. Geoecomarina 2022, 28, 65–71. [Google Scholar]

- Şentürk, Y.; Başak Esensoy, F.; Öztekin, A.; Aytan, Ü. Microplastics in Bivalves in the Southern Black Sea. In Marine Litter in the Black Sea; Aytan, Ü., Pogojeva, M., Simeonova, A., Eds.; Turkish Marine Research Foundation (TUDAV): Istanbul, Turkey, 2020; Volume 56, pp. 303–313. [Google Scholar]

- Bat, L.; Öztekin, H.C. Heavy Metals in Mytilus Galloprovincialis, Rapana Venosa and Eriphia Verrucosa from the Black Sea Coasts of Turkey as Bioindicators of Pollution. Walailak J. Sci. Technol. WJST 2016, 13, 715–728. [Google Scholar]

- Apetroaei, M.-R.; Samoilescu, G.; Nedelcu, A.; Pazara, T. Significance of Bioindicators in Evaluating Pollution Factors on the Romanian Black Sea Coast: A Minireview. In Proceedings of the “Research-Innovation-Innovative Entrepreneurship”. International Congress, 2nd ed., Chişinău, Moldova, 17–18 May 2024; Ion Creangă Pedagogical State University: Chișinău, Moldova, 2024; pp. 360–372. [Google Scholar]

- Setälä, O.; Norkko, J.; Lehtiniemi, M. Feeding Type Affects Microplastic Ingestion in a Coastal Invertebrate Community. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2016, 102, 95–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirbu, R.; Paris, S.; Cadar, E.; Cherim, M.; Mustafa, A.; Luascu, N. Mytilus Galloprovincialis—A Valuable Resource of the Black Sea Ecosystem. Eur. J. Med. Nat. Sci. 2024, 7, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drapkin, E. Effect of Rapana Bezoar Linné (Mollusca, Muricidae) on the Black Sea Fauna. Dokl. Akad. Nauk. SRR 1963, 151, 700–703. [Google Scholar]

- Zolotarev, V. The Black Sea Ecosystem Changes Related to the Introduction of New Mollusc Species. Mar. Ecol. 1996, 17, 227–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danilov, C.-S.; Tiganov, G.; Anton, E.; Nenciu, M.-I.; Nita, V.N.; Cristea, V. Rapana Venosa—New exploitable resource at the Romanian Black Sea coast. Sci. Pap. Ser. D Anim. Sci. 2018, LXI, 274–279. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. The State of Mediterranean and Black Sea Fisheries 2023—Special Edition; General Fisheries Commission for the Mediterranean: Rome, Italy, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanelli, E.; Da Ros, Z.; Menicucci, S.; Malavolti, S.; Biagiotti, I.; Canduci, G.; De Felice, A.; Leonori, I. The Pelagic Food Web of the Western Adriatic Sea: A Focus on the Role of Small Pelagics. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 14554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizraji, R.; Ahrendt, C.; Perez-Venegas, D.; Vargas, J.; Pulgar, J.; Aldana, M.; Patricio Ojeda, F.; Duarte, C.; Galbán-Malagón, C. Is the Feeding Type Related with the Content of Microplastics in Intertidal Fish Gut? Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2017, 116, 498–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Directive 2008/56/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 17 June 2008 Establishing a Framework for Community Action in the Field of Marine Environmental Policy (Marine Strategy Framework Directive). Off. J. Eur. Union 2008, L164, 19–40. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, R.-S.; Singh, S. Microplastic Pollution: Threats and Impacts on Global Marine Ecosystems. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, B.K.; Das, S.; Kumar, V.; Roy, S.; Mitra, A.; Mandal, B. Microplastics in Ecosystems: Ecotoxicological Threats and Strategies for Mitigation and Governance. Front. Mar. Sci. 2025, 12, 1672484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Digka, N.; Tsangaris, C.; Torre, M.; Anastasopoulou, A.; Zeri, C. Microplastics in Mussels and Fish from the Northern Ionian Sea. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2018, 135, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matiddi, M.; Pham, C.K.; Anastasopoulou, A.; Andresmaa, E.; Avio, C.G.; Bianchi, J.; Chaieb, O.; Palazzolo, L.; Darmon, G.; de Lucia, G.A.; et al. Monitoring Micro-Litter Ingestion in Marine Fish: A Harmonized Protocol for MSFD & RSCs Areas; INDICIT II Project Report; Wageningen University & Research: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2021; Available online: https://accedacris.ulpgc.es/bitstream/10553/114417/1/Report_Monitoring-microlitter-ingestion-in-marine-fish.pdf (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Galgani, F.; Ruiz-Orejon, L.F.; Ronchi, F.; Tallec, K.; Fischer, E.K.; Matiddi, M.; Anastasopoulou, A.; Andresmaa, E.; Angiolillo, M.; Bakker Paiva, M.; et al. Guidance on the Monitoring of Marine Litter in European Seas—An Update to Improve the Harmonised Monitoring of Marine Litter Under the Marine Strategy Framework Directive; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2023; p. 193. [Google Scholar]

- Dehaut, A.; Cassone, A.-L.; Frère, L.; Hermabessiere, L.; Himber, C.; Rinnert, E.; Rivière, G.; Lambert, C.; Soudant, P.; Huvet, A.; et al. Microplastics in Seafood: Benchmark Protocol for Their Extraction and Characterization. Environ. Pollut. 2016, 215, 223–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusher, A.L.; Bråte, I.L.N.; Munno, K.; Hurley, R.R.; Welden, N.A. Is It or Isn’t It: The Importance of Visual Classification in Microplastic Characterization. Appl. Spectrosc. 2020, 74, 1139–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, D.K.A.; Galgani, F.; Thompson, R.C.; Barlaz, M. Accumulation and Fragmentation of Plastic Debris in Global Environments. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2009, 364, 1985–1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhat, M.A.; Gaga, E.O.; Gedik, K. How Can Contamination Be Prevented during Laboratory Analysis of Atmospheric Samples for Microplastics? Environ. Monit. Assess. 2024, 196, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, W.; Deng, X.-J.; Zhang, J.; Qi, L.; Zhao, X.-Q.; Zhang, P.-Y. Assessment of Quality Control Measures in the Monitoring of Microplastic: A Critical Review. Environ. Pollut. Bioavailab. 2023, 35, 2203349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sá, S.; Torres-Pereira, A.; Ferreira, M.; Monteiro, S.S.; Fradoca, R.; Sequeira, M.; Vingada, J.; Eira, C. Microplastics in Cetaceans Stranded on the Portuguese Coast. Animals 2023, 13, 3263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusher, A.L.; O’Donnell, C.; Officer, R.; O’Connor, I. Microplastic Interactions with North Atlantic Mesopelagic Fish. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 2016, 73, 1214–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avio, C.G.; Gorbi, S.; Regoli, F. Experimental Development of a New Protocol for Extraction and Characterization of Microplastics in Fish Tissues: First Observations in Commercial Species from Adriatic Sea. Mar. Environ. Res. 2015, 111, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JASP Team. JASP (Version 0.95.4.0); JASP Team: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Gross-Sampson, M.A. Statistical Analysis in JASP—A Guide for Students, version 0.18.3; JASP: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; p. 185. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, K.R.; Gorley, R.N. PRIMER v7: User Manual/Tutorial; Plymouth Routines in Multivariate Ecological Research (PRIMER-e): Plymouth, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Lechner, A.; Keckeis, H.; Lumesberger-Loisl, F.; Zens, B.; Krusch, R.; Tritthart, M.; Glas, M.; Schludermann, E. The Danube so Colourful: A Potpourri of Plastic Litter Outnumbers Fish Larvae in Europe’s Second Largest River. Environ. Pollut. 2014, 188, 177–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Öborn, L.; Österlund, H.; Svedin, J.; Nordqvist, K.; Viklander, M. Litter in Urban Areas May Contribute to Microplastics Pollution: Laboratory Study of the Photodegradation of Four Commonly Discarded Plastics. J. Environ. Eng. 2022, 148, 06022004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Justino, A.K.S.; Lenoble, V.; Pelage, L.; Ferreira, G.V.B.; Passarone, R.; Frédou, T.; Lucena Frédou, F. Microplastic Contamination in Tropical Fishes: An Assessment of Different Feeding Habits. Reg. Stud. Mar. Sci. 2021, 45, 101857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masiá, P.; Ardura, A.; Garcia-Vazquez, E. Microplastics in Seafood: Relative Input of Mytilus Galloprovincialis and Table Salt in Mussel Dishes. Food Res. Int. 2022, 153, 110973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dambrosio, A.; Cometa, S.; Capuozzo, F.; Ceci, E.; Derosa, M.; Quaglia, N.C. Occurrence and Characterization of Microplastics in Commercial Mussels (Mytilus Galloprovincialis) from Apulia Region (Italy). Foods 2023, 12, 1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Zhu, X.; Teng, J.; Zhao, J.; Li, C.; Shan, E.; Zhang, C.; Wang, Q. Pollution Characteristics of Microplastics in Mollusks from the Coastal Area of Yantai, China. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2021, 107, 693–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolandhasamy, P.; Su, L.; Li, J.; Qu, X.; Jabeen, K.; Shi, H. Adherence of Microplastics to Soft Tissue of Mussels: A Novel Way to Uptake Microplastics beyond Ingestion. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 610–611, 635–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, B.; Albentosa, M. Insights into the Uptake, Elimination and Accumulation of Microplastics in Mussel. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 249, 321–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piarulli, S.; Airoldi, L. Mussels Facilitate the Sinking of Microplastics to Bottom Sediments and Their Subsequent Uptake by Detritus-Feeders. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 266, 115151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovačić, I.; Štefanko, K.; Špada, V.; Pustijanac, E.; Buršić, M.; Burić, P. Microplastics in Mediterranean Mussel Mytilus galloprovincialis: Comparison between Cultured and Wild Type Mussels from the Northern Adriatic. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 2056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, J.; Jeyasanta, K.I.; Laju, R.L.; Edward, J.K.P. Microplastic Contamination in Indian Edible Mussels (Perna perna and Perna viridis) and Their Environs. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2021, 171, 112678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, V.G.; Skov, M.W.; Hiddink, J.G.; Walton, M. Microplastics Alter Multiple Biological Processes of Marine Benthic Fauna. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 845, 157362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naji, A.; Nuri, M.; Vethaak, A.D. Microplastics Contamination in Molluscs from the Northern Part of the Persian Gulf. Environ. Pollut. 2018, 235, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bour, A.; Avio, C.G.; Gorbi, S.; Regoli, F.; Hylland, K. Presence of Microplastics in Benthic and Epibenthic Organisms: Influence of Habitat, Feeding Mode and Trophic Level. Environ. Pollut. 2018, 243, 1217–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savini, D.; Occhipinti-Ambrogi, A. Consumption Rates and Prey Preference of the Invasive Gastropod Rapana Venosa in the Northern Adriatic Sea. Helgol. Mar. Res. 2006, 60, 153–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harding, J.M.; Mann, R. Observations on the Biology of the Veined Rapa Whelk, Rapana Venosa, (Valenciennes, 1846) in the Chesapeake Bay. J. Shellfish Res. 1999, 18, 9–17. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, R.N. Optimal Foraging Theory in the Marine Context. Ocean. Mar. Biol. Ann. Rev. 1980, 18, 423–481. [Google Scholar]

- Cincinelli, A.; Scopetani, C.; Chelazzi, D.; Martellini, T.; Pogojeva, M.; Slobodnik, J. Microplastics in the Black Sea Sediments. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 760, 143898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beer, S.; Garm, A.; Huwer, B.; Dierking, J.; Nielsen, T.G. No Increase in Marine Microplastic Concentration over the Last Three Decades—A Case Study from the Baltic Sea. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 621, 1272–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ory, N.C.; Gallardo, C.; Lenz, M.; Thiel, M. Capture, Swallowing, and Egestion of Microplastics by a Planktivorous Juvenile Fish. Environ. Pollut. 2018, 240, 566–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collard, F.; Gilbert, B.; Eppe, G.; Roos, L.; Compère, P.; Das, K.; Parmentier, E. Morphology of the Filtration Apparatus of Three Planktivorous Fishes and Relation with Ingested Anthropogenic Particles. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2017, 116, 182–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Hont, A.; Gittenberger, A.; Leuven, R.S.E.W.; Hendriks, A.J. Dropping the Microbead: Source and Sink Related Microplastic Distribution in the Black Sea and Caspian Sea Basins. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2021, 173, 112982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobchev, N.; Berov, D.; Klayn, S.; Karamfilov, V. High Microplastic Pollution in Marine Sediments Associated with Urbanised Areas along the SW Bulgarian Black Sea Coast. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2024, 209, 117150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tunç Dede, Ö.; Tepe, Y. An Overview on Microplastic Pollution in the Black Sea Coastal Waters of Türkiye. Reg. Stud. Mar. Sci. 2025, 89, 104319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aytan, U.; Valente, A.; Senturk, Y.; Usta, R.; Esensoy Sahin, F.B.; Mazlum, R.E.; Agirbas, E. First Evaluation of Neustonic Microplastics in Black Sea Waters. Mar. Environ. Res. 2016, 119, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ugwu, K.; Herrera, A.; Gómez, M. Microplastics in Marine Biota: A Review. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2021, 169, 112540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Procop, I.; Calmuc, M.; Pessenlehner, S.; Trifu, C.; Ceoromila, A.C.; Calmuc, V.A.; Fetecău, C.; Iticescu, C.; Musat, V.; Liedermann, M. The First Spatio-Temporal Study of the Microplastics and Meso–Macroplastics Transport in the Romanian Danube. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2024, 36, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akyildiz, S.H.; Fiore, S.; Bruno, M.; Sezgin, H.; Yalcin-Enis, I.; Yalcin, B.; Bellopede, R. Release of Microplastic Fibers from Synthetic Textiles during Household Washing. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 357, 124455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tedesco, M.C.; Fisher, R.M.; Stuetz, R.M. Emission of Fibres from Textiles: A Critical and Systematic Review of Mechanisms of Release during Machine Washing. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 955, 177090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Świątek, O.; Dąbrowska, A. A Feasible and Efficient Monitoring Method of Synthetic Fibers Released during Textile Washing. Microplastics 2024, 3, 67–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novotna, J.; Tunak, M.; Militky, J.; Kremenakova, D.; Wiener, J.; Novakova, J.; Sevcu, A. Release of Microplastic Fibers from Polyester Knit Fleece during Abrasion, Washing, and Drying. ACS Omega 2025, 10, 14241–14249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Browne, M.A.; Crump, P.; Niven, S.J.; Teuten, E.; Tonkin, A.; Galloway, T.; Thompson, R. Accumulation of Microplastic on Shorelines Woldwide: Sources and Sinks. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011, 45, 9175–9179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Napper, I.E.; Thompson, R.C. Release of Synthetic Microplastic Plastic Fibres from Domestic Washing Machines: Effects of Fabric Type and Washing Conditions. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2016, 112, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tursi, A.; Baratta, M.; Easton, T.; Chatzisymeon, E.; Chidichimo, F.; De Biase, M.; De Filpo, G. Microplastics in Aquatic Systems, a Comprehensive Review: Origination, Accumulation, Impact, and Removal Technologies. RSC Adv. 2022, 12, 28318–28340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lambert, S.; Wagner, M. Formation of Microscopic Particles during the Degradation of Different Polymers. Chemosphere 2016, 161, 510–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezania, S.; Park, J.; Md Din, M.F.; Mat Taib, S.; Talaiekhozani, A.; Kumar Yadav, K.; Kamyab, H. Microplastics Pollution in Different Aquatic Environments and Biota: A Review of Recent Studies. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2018, 133, 191–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Wang, J.; Yee Leung, K.M.; Wu, F. Color: An Important but Overlooked Factor for Plastic Photoaging and Microplastic Formation. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 9161–9163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martí, E.; Martin, C.; Galli, M.; Echevarría, F.; Duarte, C.M.; Cózar, A. The Colors of the Ocean Plastics. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 54, 6594–6601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kole, P.J.; Löhr, A.J.; Van Belleghem, F.; Ragas, A. Wear and Tear of Tyres: A Stealthy Source of Microplastics in the Environment. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frias, J.P.G.L.; Sobral, P.; Ferreira, A.M. Organic Pollutants in Microplastics from Two Beaches of the Portuguese Coast. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2010, 60, 1988–1992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.; Xu, E.G. Black Microplastic in Plastic Pollution: Undetected and Underestimated? Water Emerg. Contam. Nanoplastics 2022, 1, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, B.; Jin, S.-R.; Chen, Z.-Z.; Gao, J.-Z.; Liu, Y.-N.; Liu, J.-H.; Feng, X.-S. Single and Combined Effects of Microplastics and Cadmium on the Cadmium Accumulation, Antioxidant Defence and Innate Immunity of the Discus Fish (Symphysodon aequifasciatus). Environ. Pollut. 2018, 243, 462–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crawford, C.B.; Quinn, B. The Biological Impacts and Effects of Contaminated Microplastics. In Microplastic Pollutants; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 159–178. [Google Scholar]

- Lusher, A. Microplastics in the Marine Environment: Distribution, Interactions and Effects. In Marine Anthropogenic Litter; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 245–307. [Google Scholar]

- Pojar, I.; Stănică, A.; Stock, F.; Kochleus, C.; Schultz, M.; Bradley, C. Sedimentary Microplastic Concentrations from the Romanian Danube River to the Black Sea. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baboș, T.; Dobre, O.; Lazăr, C.; Palcu, D.V.; Pojar, I. Characterisation of Floating Microplastic in Romanian Coastal Waters. Geoecomarina 2025, 31, 51–58. [Google Scholar]

- Glevitzky, M.; Dumitrel, G.-A.; Rusu, G.I.; Toneva, D.; Vergiev, S.; Corcheş, M.-T.; Pană, A.-M.; Popa, M. Microplastic Pollution on the Beaches of the Black Sea in Romania and Bulgaria. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 4751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, S.; Soltani, N.; Keshavarzi, B.; Moore, F.; Turner, A.; Hassanaghaei, M. Microplastics in Different Tissues of Fish and Prawn from the Musa Estuary, Persian Gulf. Chemosphere 2018, 205, 80–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conger, E.; Dziobak, M.; Berens McCabe, E.J.; Curtin, T.; Gaur, A.; Wells, R.S.; Weinstein, J.E.; Hart, L.B. An Analysis of Suspected Microplastics in the Muscle and Gastrointestinal Tissues of Fish from Sarasota Bay, FL: Exposure and Implications for Apex Predators and Seafood Consumers. Environments 2024, 11, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Giacinto, F.; Di Renzo, L.; Mascilongo, G.; Notarstefano, V.; Gioacchini, G.; Giorgini, E.; Bogdanović, T.; Petričević, S.; Listeš, E.; Brkljača, M.; et al. Detection of Microplastics, Polymers and Additives in Edible Muscle of Swordfish (Xiphias Gladius) and Bluefin Tuna (Thunnus Thynnus) Caught in the Mediterranean Sea. J. Sea Res. 2023, 192, 102359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.B.; Pingki, F.H.; Azad, M.A.S.; Nur, A.-A.U.; Banik, P.; Paray, B.A.; Arai, T.; Yu, J. Microplastics in Different Tissues of a Commonly Consumed Fish, Scomberomorus Guttatus, from a Large Subtropical Estuary: Accumulation, Characterization, and Contamination Assessment. Biology 2023, 12, 1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhbarizadeh, R.; Moore, F.; Keshavarzi, B. Investigating a Probable Relationship between Microplastics and Potentially Toxic Elements in Fish Muscles from Northeast of Persian Gulf. Environ. Pollut. 2018, 232, 154–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barboza, L.G.A.; Lopes, C.; Oliveira, P.; Bessa, F.; Otero, V.; Henriques, B.; Raimundo, J.; Caetano, M.; Vale, C.; Guilhermino, L. Microplastics in Wild Fish from North East Atlantic Ocean and Its Potential for Causing Neurotoxic Effects, Lipid Oxidative Damage, and Human Health Risks Associated with Ingestion Exposure. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 717, 134625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karami, A.; Golieskardi, A.; Choo, C.K.; Larat, V.; Karbalaei, S.; Salamatinia, B. Plastic and microplastic contamination in canned sardines and sprats. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 612, 1380–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed Nor, N.H.; Kooi, M.; Diepens, N.J.; Koelmans, A.A. Lifetime Accumulation of Microplastic in Children and Adults. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 55, 5084–5096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Microplastics in Food Commodities—A Food Safety Review on Human Exposure Through Dietary Sources; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merdzhanova, A.; Raykov, V.; Stancheva, R.; Stanchev, P. Consumption of Fish and Fishery Products in Bulgaria: Trends and Perspectives in the Context of the Black Sea Region. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Length (cm) | Width (cm) | Weight (g) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Range | Mean | Range | Mean | Range | Mean | |

| Mytilus galloprovincialis | 4.08–5.35 | 4.67 ±0.4 SD ±0.1 SE | 2.84–1.96 | 2.23 ±0.24 SD ±0.06 SE | 2.43–6.05 | 3.59 ±0.94 SD ±0.24 SE |

| Rapana venosa | 3.91–5.52 | 4.62 ±0.41 SD ±0.1 SE | 3.29–4.11 | 3.47 ±0.35 SD ±0.09 SE | 5.02–9.27 | 7.02 ±1.11 SD ±0.28 SE |

| Sprattus sprattus | 6.7–8.9 | 7.75 ±0.65 SD ±0.11 SE | N/A | N/A | 1.72–3.89 | 2.66 ±0.65 SD ±0.12 SE |

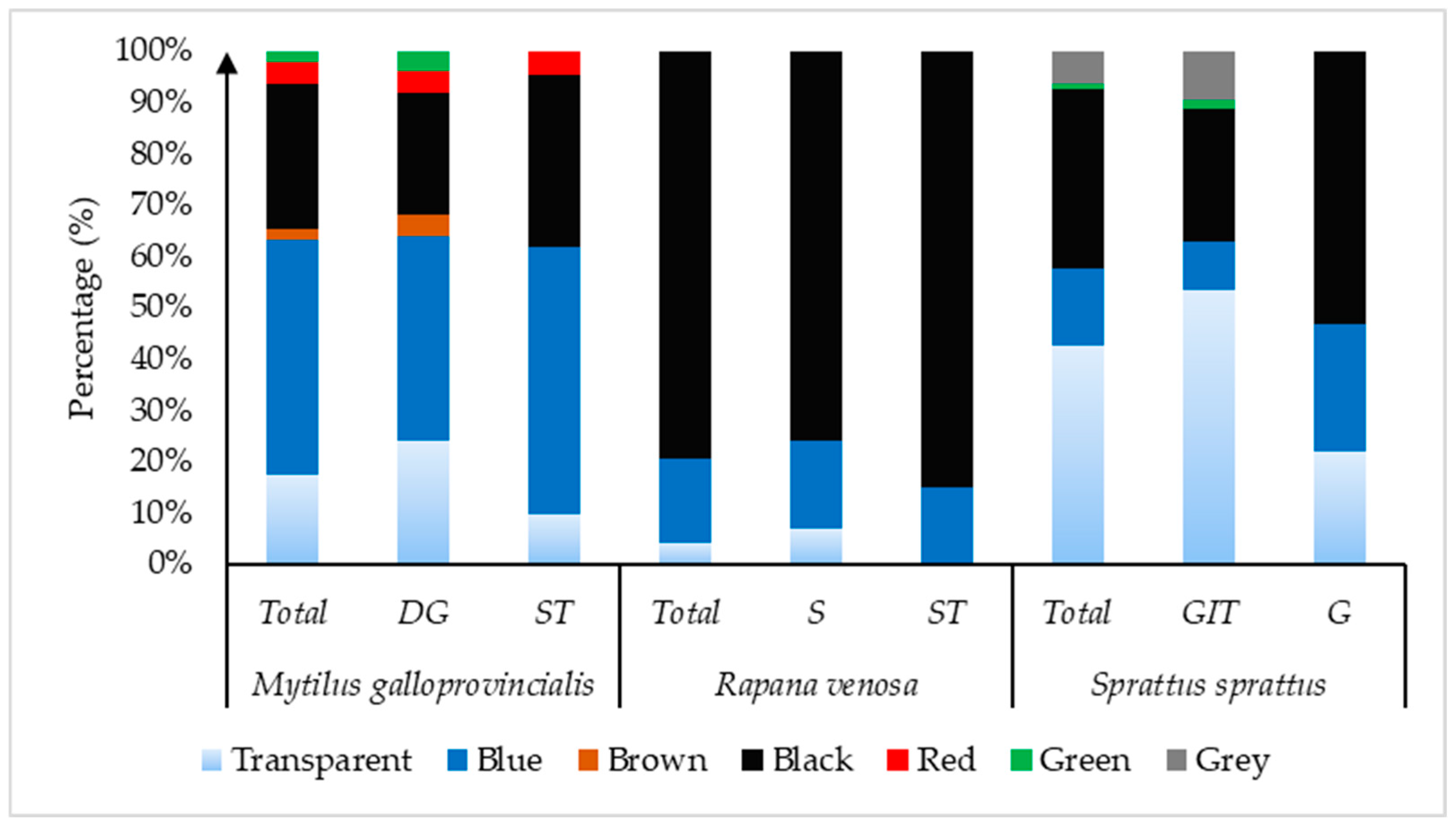

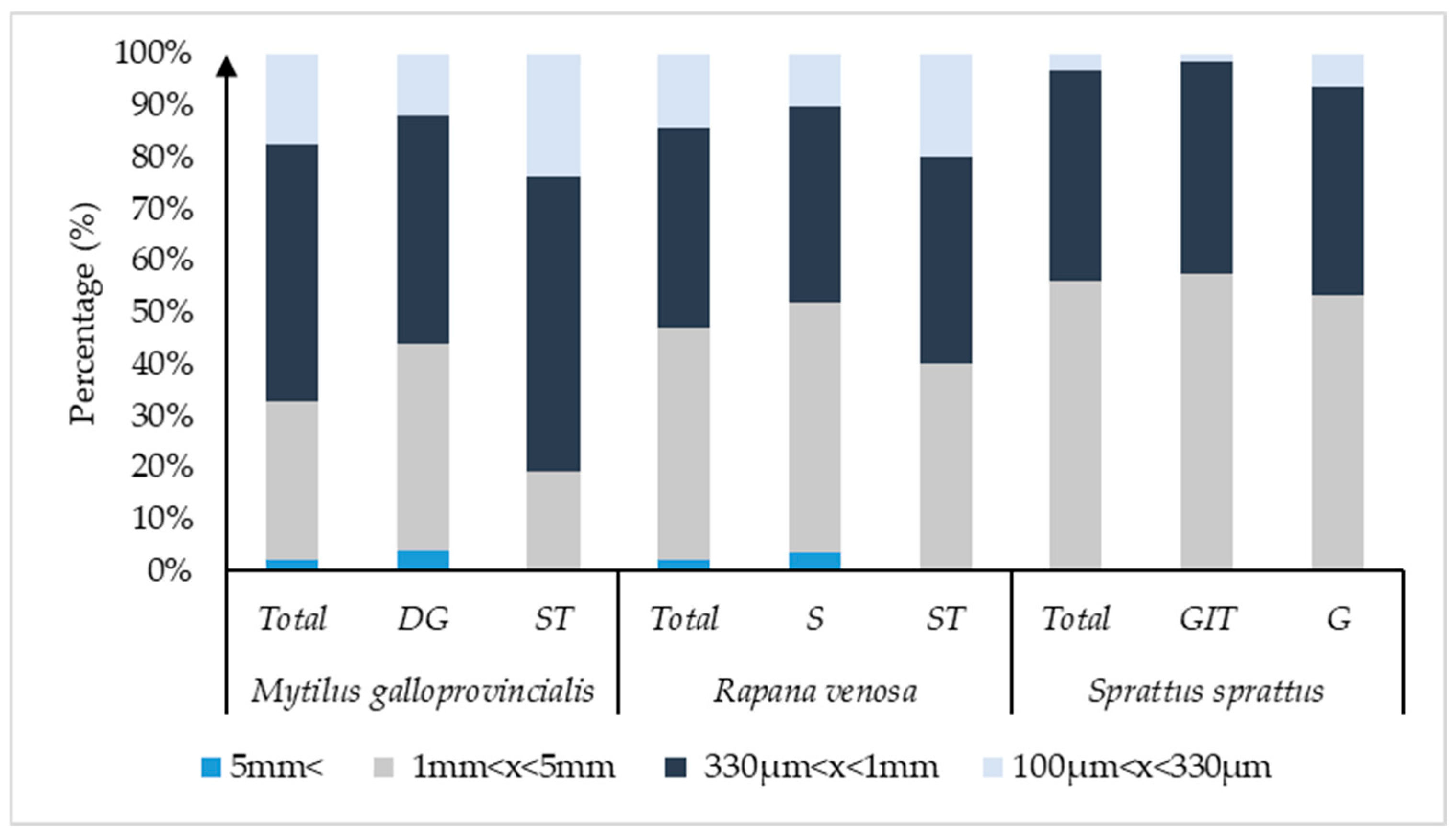

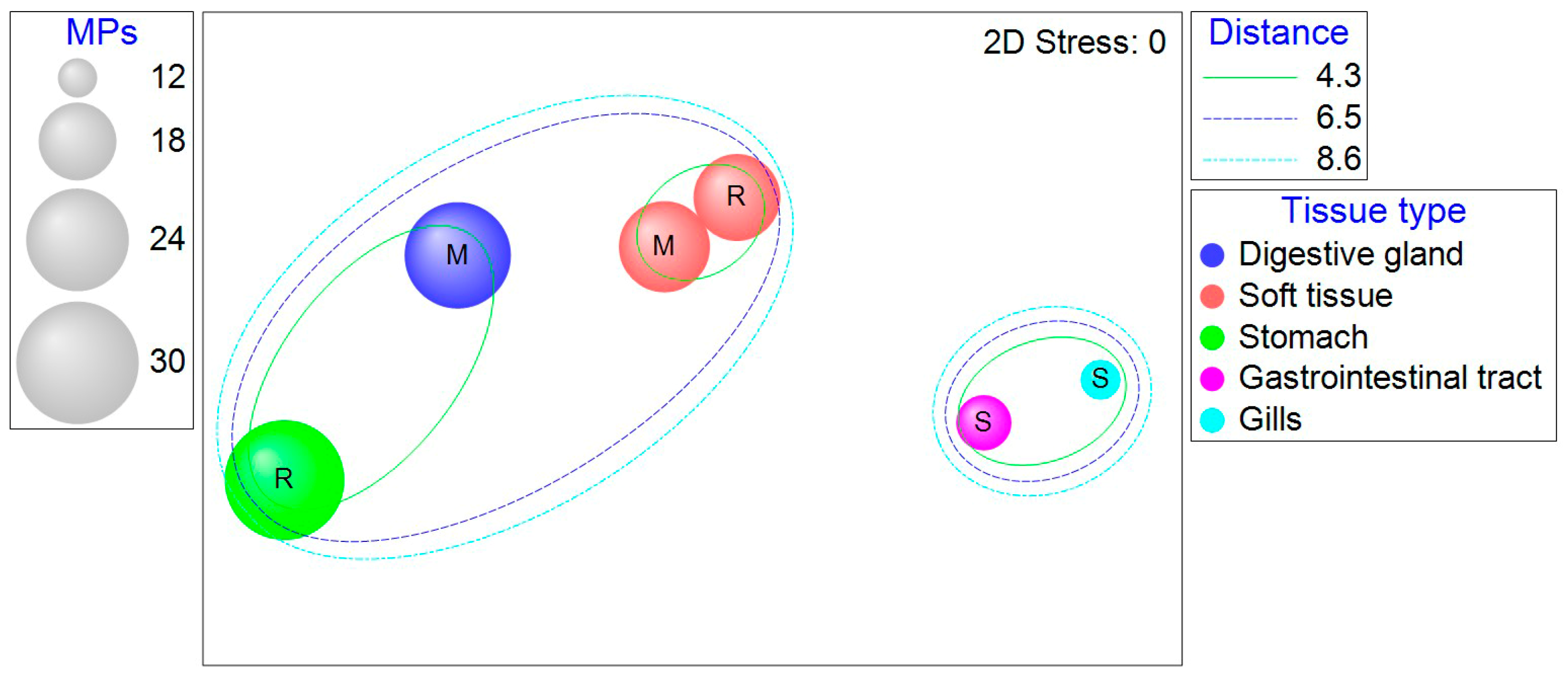

| Colors (%) | Size (%) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Species | Transparent | Blue | Black | Red | Green | Brown | Grey | 100–330 µm | 330 µm−1 mm | 1–5 mm | >5 mm |

| Mytilus galloprovincialis | |||||||||||

| Whole organism | 17.4 | 45.7 | 28.3 | 4.4 | 2.17 | 2.17 | 0 | 17.4 | 50 | 30.43 | 2.17 |

| DG | 24 | 40 | 24 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 12 | 44 | 40 | 4 |

| ST | 9.52 | 52.4 | 33.3 | 4.8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 23.81 | 57.14 | 19.05 | 0 |

| Rapana Venosa | |||||||||||

| Whole organism | 4.08 | 16.3 | 79.6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 14.29 | 38.78 | 44.89 | 2.04 |

| S | 6.9 | 17.2 | 75.9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10.34 | 37.93 | 48.28 | 3.45 |

| ST | 15 | 85 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 20 | 40 | 40 | 0 | |

| Sprattus sprattus | |||||||||||

| Whole organism | 42.55 | 14.9 | 35.1 | 0 | 1.06 | 0 | 6.38 | 3.23 | 40.86 | 55.91 | 0 |

| G | 53.23 | 9.67 | 25.8 | 0 | 1.61 | 0 | 9.68 | 6.25 | 40.62 | 53.13 | 0 |

| GIT | 21.88 | 25 | 53.1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1.63 | 41 | 57.37 | 0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ciucă, A.-M.; Barbeș, L.; Pantea, E.-D.; Harcotă, G.-E.; Danilov, C.S.; Filimon, A.; Stoica, E. Microplastic Accumulation in Commercially Important Black Sea Fish and Shellfish: European Sprat (Sprattus sprattus), Mussels (Mytilus galloprovincialis) and Rapa Whelks (Rapana venosa). Sustainability 2025, 17, 11006. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411006

Ciucă A-M, Barbeș L, Pantea E-D, Harcotă G-E, Danilov CS, Filimon A, Stoica E. Microplastic Accumulation in Commercially Important Black Sea Fish and Shellfish: European Sprat (Sprattus sprattus), Mussels (Mytilus galloprovincialis) and Rapa Whelks (Rapana venosa). Sustainability. 2025; 17(24):11006. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411006

Chicago/Turabian StyleCiucă, Andreea-Mădălina, Lucica Barbeș, Elena-Daniela Pantea, George-Emanuel Harcotă, Cristian Sorin Danilov, Adrian Filimon, and Elena Stoica. 2025. "Microplastic Accumulation in Commercially Important Black Sea Fish and Shellfish: European Sprat (Sprattus sprattus), Mussels (Mytilus galloprovincialis) and Rapa Whelks (Rapana venosa)" Sustainability 17, no. 24: 11006. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411006

APA StyleCiucă, A.-M., Barbeș, L., Pantea, E.-D., Harcotă, G.-E., Danilov, C. S., Filimon, A., & Stoica, E. (2025). Microplastic Accumulation in Commercially Important Black Sea Fish and Shellfish: European Sprat (Sprattus sprattus), Mussels (Mytilus galloprovincialis) and Rapa Whelks (Rapana venosa). Sustainability, 17(24), 11006. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411006