Abstract

This study applies integrated LCA–LCC to 1 L of bottled beer at a representative small Japanese brewery using 2024 operational data. Following ISO 14040/44, the cradle-to-gate boundary covers raw materials (excluding agricultural cultivation while including transport and preprocessing), brewing, packaging, and thermal sterilization. The baseline global warming impact is 0.52 kg CO2e/L and the cost is JPY 487/L, with single-use glass and labor identified as dominant hotspots. As beer is produced from malt, hops, yeast, and water, this study focuses on how alternative production strategies mitigate sustainability hotspots within this process. Three alternative production scenarios were evaluated within this integrated LCA–LCC model. Scenario 1 (local rice substitution) replaces 30% of the fermentable extract from imported malt with domestically grown rice, changing only ingredient transport and preprocessing within the truncated cradle-to-gate boundary (crop cultivation remains excluded), and yields 0.55 kg CO2e/L and JPY 492/L, i.e., a slightly higher global warming impact and cost than the baseline. Scenario 2 (direct sales expansion) assumes that 50% of the beer is sold on site via draft, thereby reducing single-use glass bottles and fuel for pasteurization and achieving 0.29 kg CO2e/L (−44%) and JPY 435/L (−11%) in the deterministic model, the best combined environmental and economic performance among the modeled options. Scenario 3 (joint logistics) models cooperative brewing and shared distribution, which improve labor efficiency and modestly reduce transport intensity, delivering 399 JPY/L in the deterministic model; however, Monte Carlo analysis yields a higher expected cost and indicates that these cost savings are not robust. One-way sensitivity analysis identified packaging and labor as the dominant drivers of both environmental and economic performance, while Monte Carlo simulation confirmed the relative insignificance of electricity-related parameters and reinforced the comparative robustness of Scenario 2. Together, these results highlight the most effective leverage points for a sustainable transition in Japan’s craft beer sector, offering the greatest leverage for a more sustainable transition in Japan’s craft brewing sector.

1. Introduction

The craft beer sector has grown rapidly across the globe, reshaping the beverage industry through product diversification, consumer orientation toward authenticity, and strong regional embeddedness [1,2,3,4]. Despite its relatively small market share compared to multinational breweries, craft beer production has received increasing scholarly attention due to its distinct socioeconomic role and sustainability implications [5,6,7]. Previous life cycle assessment (LCA) and life cycle costing (LCC) studies have identified packaging, energy use, and raw material sourcing as critical environmental and economic hotspots in beer production [8,9]. To address these hotspots, widely discussed interventions include reusable glass bottles, can substitution, renewable electricity procurement, and automation [9,10,11,12]. While these strategies provide valuable insights, they largely represent generic measures, raising questions about their transferability to country-specific craft beer industries.

Japan offers a distinctive context in which to examine such issues. Following the deregulation of brewing licenses in 1994, the number of microbreweries increased significantly, giving rise to a diverse craft beer culture embedded in both urban and rural regions [13]. Yet Japanese craft breweries face structural challenges distinct from those of North America and Europe. First, malt and hops are predominantly imported, as domestic cultivation is limited by climatic and agronomic constraints [14]. Second, the small-scale nature of production, shaped by licensing thresholds and taxation schemes, generates inefficiencies in logistics and packaging [15]. Third, labor costs constitute a disproportionately large share of overall production expenses, reflecting artisanal practices but threatening long-term economic resilience [16]. Finally, although Japan enjoys high-quality water resources, the cultural preference for bottled beer and the limited valorization of brewing by-products highlight untapped opportunities for circular economy approaches [17,18,19].

International practices provide useful reference points. In Europe, localized malt and hop cultivation has been promoted to reduce import dependence and strengthen agricultural value chains [20,21]. Cooperative logistics and keg reuse schemes have been implemented to improve distribution efficiency [15,22]. Collaborative brewing and shared equipment use have become increasingly common in North America to lower fixed costs and enhance flexibility [23]. Brewing by-products such as spent grain are widely valued as feed, fertilizer, or bioenergy inputs, contributing to circular economy objectives [24].

In contrast, Japan relies heavily on imported malt and hops because domestic barley production is not self-sufficient and is constrained by climatic and agronomic limitations that restrict both yield and malting quality. Regional variability in barley cultivation is substantial, and only a small share of domestically produced barley meets malting-grade specifications, further reinforcing dependence on imports and increasing logistical burdens for breweries.

These structural conditions distinguish Japan from Western contexts, where local ingredient sourcing, collaborative logistics, and circular economy practices are more readily implemented. Consequently, the applicability and performance of such sustainability strategies in Japan remain insufficiently understood, given the country’s unique regulatory, agricultural, and consumer behavior constraints.

Building upon this gap, the present study designs and evaluates three alternative scenarios that explicitly reflect Japan’s institutional, agronomic, and sociocultural characteristics: (1) substitution of imported malt and hops with domestic grains such as rice or buckwheat, (2) expansion of on-site consumption and direct sales in tourism-oriented markets to reduce packaging and distribution burdens, and (3) cooperative brewing and shared logistics under Japan’s licensing regime to improve efficiency and mitigate labor cost pressures. The analysis is based on complete operational and financial data for the year 2024 from Ishikawa Shuzo, a representative small Japanese craft brewery, and is conducted as a process-level LCA–LCC case study rather than an experimental quality assessment. No additional sampling campaigns or chemical and physical analyses of beer quality were performed, as the focus lies on modeling environmental and economic performance over the full production system. By integrating LCA and LCC, we assess the environmental and economic implications of these scenarios, contributing to a better understanding of how international sustainability practices can be contextualized for non-Western craft beer industries. This study thus aims to advance the literature on sustainable food and beverage systems by highlighting the transferability and limitations of sustainability strategies when applied under Japan’s unique structural conditions. While sustainability is widely understood to encompass environmental, economic, and social dimensions, the present analysis focuses specifically on the environmental and economic pillars. The social dimension—such as community engagement, working conditions, or employment effects—is acknowledged as an important component of sustainability but lies outside the quantitative scope of this LCA–LCC framework.

2. Methodology

2.1. Case Study

This study employed a case study approach focusing on Ishikawa Shuzo, a local craft brewery located in Tokyo, Japan. The analysis was based on operational and financial data collected for the year 2024. Ishikawa Shuzo was selected because it represents a typical small- to medium-scale Japanese craft brewery with integrated production processes, including mashing, boiling, fermentation, bottling, and sterilization. The functional unit was defined as 1 L of bottled beer.

2.2. Life Cycle Assessment (LCA)

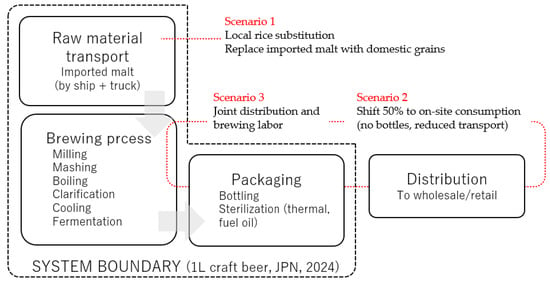

The environmental assessment followed the ISO 14040/44 framework [25], using SimaPro software (version 9.5) in combination with the ecoinvent 3.9.1 database under a cut-off allocation system. The system boundary was defined as a truncated cradle-to-gate system, encompassing raw material transport (malt imported by sea freight and domestic distribution by truck), brewing operations (milling, mashing, boiling, clarification, cooling, and fermentation), packaging (bottling), and sterilization prior to distribution. The system boundary and process flows are illustrated in Figure 1. A detailed foreground life cycle inventory (LCI) for electricity use, water consumption, heavy fuel oil inputs, packaging materials, and process equipment is provided in Supplementary Table S1 to ensure transparency and reproducibility.

Figure 1.

System boundary of craft beer production and scenario interventions (functional unit: 1 L of bottled beer at the brewery gate, Japan, 2024). The diagram illustrates the system boundary and three scenarios: Scenario 1 substitutes 30% of imported malt with domestic rice; Scenario 2 shifts 50% of sales to on-site draft to reduce packaging and pasteurization; Scenario 3 introduces shared logistics and partial labor reduction. Note: Agricultural cultivation is excluded from the main boundary. Scenario 1’s upstream effects are assessed separately in a supplementary sensitivity analysis.

Upstream agricultural cultivation of barley and rice was excluded from the main system boundary. This exclusion is consistent with previous brewery-level LCA studies and reflects the practical limitations of data availability for small breweries.

However, because Scenario 1 involves a material substitution that implicitly affects upstream processes, we conducted a supplemental sensitivity analysis to quantify the potential impact of barley and rice cultivation, without extending the core model boundary.

Because Scenario 1 involves the partial substitution of imported malt with domestic rice, upstream agricultural cultivation may nevertheless influence the relative comparison between scenarios. To quantify the magnitude of the upstream processes excluded from the truncated cradle-to-gate boundary, we therefore conducted a literature-based sensitivity analysis using cultivation emission factors for malted barley and Japanese rice reported in previous LCA and water footprint studies [26,27,28,29,30,31]. These factors (kg CO2e kg−1 and L kg−1) were first converted to a per-liter-of-beer basis using the ingredient inputs applied in this study (0.20 kg malt L−1 in the baseline; 0.14 kg malt L−1 and 0.06 kg rice L−1 for the 30% rice adjunct in Scenario 1), as summarized in Supplementary Table S2. In the second step, the cultivation-related global warming impact per liter (Gcult) was added to the truncated cradle-to-gate global warming impact obtained from the brewery-level model (Gtrunc) to obtain an adjusted value including cultivation (Gtotal = Gtrunc + Gcult) for each scenario. The resulting changes in global warming impact are reported in Supplementary Table S3. This supplementary analysis serves only as an approximation and does not constitute an expansion of the system boundary. It clarifies the relative scale of omitted upstream processes and confirms that the dominant hotspots—single-use glass bottle production and thermal sterilization—remain unchanged in all modeled cases.

Particular attention was paid to two aspects that are often aggregated or omitted in related research. First, clarification was modeled as a distinct stage, which enabled by-products such as spent grain and trub to be explicitly accounted for. In this study, these by-products refer to the solid residues generated during mashing and wort clarification; although spent grain is often considered a high-quality feed ingredient or a potential input to fertilizer or bioenergy systems, such downstream valorization, quality assessment, and cost-effectiveness analysis lie outside the system boundary of this LCA–LCC model. Accordingly, the by-products are modeled only in terms of their mass flows and not their economic or functional value.

Second, thermal sterilization was treated as a separate process to represent the reliance of small breweries on heavy fuel oil.

Impact assessment was conducted at the midpoint level using the ReCiPe 2016 method [32], which covers 18 impact categories including climate change, particulate matter formation, freshwater and marine ecotoxicity, water consumption, and resource scarcity. Greenhouse gas emissions were converted into CO2 equivalents using global warming potentials (GWP100) as characterization factors, while the resulting indicator was reported as global warming impact (kg CO2e). In this study, six categories are chosen as the main baseline indicators: global warming impact, water consumption, terrestrial ecotoxicity, fossil resource depletion, human carcinogenic toxicity, and fine particulate matter formation. These indicators were selected because they are closely related to the dominant hotspots identified in our system—namely heavy fuel oil combustion, single-use glass bottle production, and water use—and because their inventory data are relatively robust and relevant for brewery-level decision making.

2.3. Life Cycle Costing (LCC)

Life cycle costing (LCC) was applied in parallel with the LCA, ensuring consistency in the definition of the system boundary [33]. Costs were classified into three categories: fixed costs, variable costs, and maintenance costs. Fixed costs represent the initial capital investments in equipment such as milling machines, mash tuns, kettles, fermentation tanks, bottling machines, and sterilizers, which were annualized over useful lifetimes of 7 to 20 years. In practice, brewing and bottling equipment in small- and medium-sized breweries is often used much longer than the statutory depreciation period, commonly around 15–20 years with proper maintenance. Although Japanese tax rules specify shorter lifetimes (e.g., about 7 years for machinery), the actual service life is typically longer. Therefore, the lifetimes applied in our LCC model (7–20 years) were chosen to reflect realistic operational conditions at the case study brewery and similar facilities.

Variable costs correspond to expenditures directly linked to production volume, including raw materials (malt, hops, and adjuncts), packaging materials (primarily glass bottles), utilities such as electricity, water, and heavy fuel oil, and labor. Maintenance costs represent the recurrent expenditure required to sustain the operation of brewing and bottling equipment.

The cost analysis was conducted by allocating all expenses to the functional unit of 1 L of bottled beer at the brewery gate, following the same system boundary as defined for the LCA. This alignment ensures direct comparability between environmental and economic indicators and supports integrated interpretation of results. For reference, producing 1 L of bottled beer requires approximately three 330 mL single-use glass bottles, which together cost about JPY 93 according to the brewery’s 2024 operational data; these bottles are standard, non-returnable containers commonly used in Japanese craft breweries and therefore represent average-quality packaging rather than premium glassware. All numerical inputs used in the LCC model—including equipment purchase prices, service lifetimes, annualized capital costs, ingredient prices, electricity and fuel consumption costs, labor costs, and packaging costs—are fully documented in Supplementary Table S4 to ensure transparency and reproducibility. The numerical outcomes of the baseline case are presented in the Results section.

2.4. Scenario Design

To explore alternative production strategies, three scenarios were developed in addition to the baseline. Each scenario targets different structural hotspots identified in the baseline assessment: imported ingredients and transport (Scenario 1), single-use packaging and thermal sterilization (Scenario 2), and labor- and logistics-related inefficiencies (Scenario 3). Scenario 1 involves partial substitution of brewing ingredients using domestic grains, whereas Scenarios 2 and 3 focus on reducing packaging burdens and improving labor and logistics efficiency, respectively. All quantitative assumptions are listed in Supplementary Table S5.

Baseline: Current operation of Ishikawa Shuzo (2024), with single-use glass bottles, conventional Japanese grid electricity, and manual bottling.

Scenario 1 replaces 30% of the fermentable extract from imported malt with domestically grown rice on a mass basis (0.14 kg malt and 0.06 kg rice per liter of beer), while maintaining a constant total extract yield. This scenario therefore represents partial substitution rather than full replacement of barley with rice. International sea freight associated with the substituted malt portion is removed (equivalent to a 30% reduction in the baseline 4.21 tkm/L), and domestic truck transport of rice (30–80 km) is added. No changes are introduced to brewing temperature profiles, fermentation, or packaging; thus, the scenario isolates the effects of ingredient sourcing and associated transport within the truncated cradle-to-gate boundary.

Scenario 2 (direct sales expansion): This scenario models a shift toward on-site consumption by assuming that 50% of the beer volume is sold via draft (kegs) and 50% via bottled distribution. For the draft share, single-use glass bottles are reduced from 3.0 to 1.5 bottles per liter, and thermal sterilization is largely eliminated, decreasing heavy fuel oil consumption from 0.0909 L/L to approximately 0.01 L/L. Labor requirements for packaging are reduced by an estimated 30%, reflecting simplified handling and cleaning operations, and a small additional electricity demand for keg cleaning and cooling is included.

Scenario 3 (Joint logistics): Scenario 3 represents cooperative brewing and shared logistics among multiple breweries. The model assumes a 20–30% reduction in truck-kilometers per liter due to consolidated deliveries and a 30–40% reduction in labor time per liter arising from shared bottling, cleaning, and handling operations. Brewing yields and packaging formats (single-use 330 mL bottles) remain unchanged relative to the baseline, so the scenario isolates the effects of logistics and labor efficiency.

2.5. Senstitivity and Uncertainity Analysis

Sensitivity and uncertainty analyses were conducted to evaluate the robustness of the LCA–LCC results. First, one-at-a-time sensitivity analysis was performed by varying key parameters by ±10%, ±20%, and ±30%. The parameters examined included glass bottle mass, labor time and wage rate, transport distances, heavy fuel oil consumption, domestic ingredient prices, electricity emission factors, and production scale. These parameters correspond to the structural changes represented in the three scenario designs. The variation ranges and parameter choices were based on observed operational variability at the case brewery, supplier-provided specifications, market price fluctuations, and values reported in previous LCA studies, ensuring that the sensitivity tests remained within realistic and technically feasible bounds. In addition, the parameterization was reviewed to avoid combinations that would violate brewing practice or system constraints, and the logistics assumptions for ingredient substitution and joint deliveries were confirmed to be operationally achievable within the brewery’s existing infrastructure.

For the uncertainty analysis, a Monte Carlo simulation with 1000 iterations was performed. Probability distributions were assigned according to the nature of each parameter. Triangular distributions were applied to cost-related and market-based variables (e.g., malt price, bottle price, labor cost), using minimum–mode–maximum values derived from accounting data and observed price ranges. Lognormal distributions were used for strictly non-negative operational quantities such as electricity consumption, heavy fuel oil use, and glass bottle mass, reflecting their skewed variability. Beta distributions were assigned to proportion-type parameters (e.g., draft sales share), ensuring values remained within 0.1. When only point estimates were available, conservative ±20% triangular ranges were applied.

Correlations were introduced where parameters were causally related. Labor cost was calculated deterministically from sampled labor time and the wage rate, and fuel cost was derived from sampled heavy fuel oil consumption and its unit price. All other parameters were treated as independent. The full list of stochastic parameters, probability distributions, parameter ranges, and correlation structures is provided in Supplementary Table S6.

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Performance

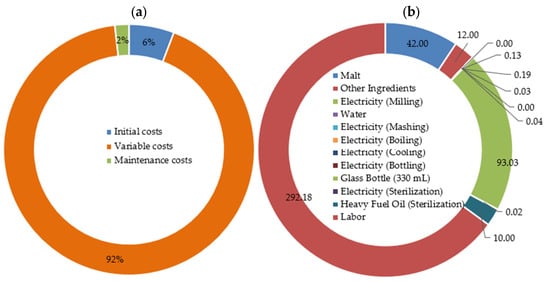

The total cost of producing 1 L of bottled craft beer in the baseline case is JPY 487/L. Operational (variable) costs dominate the LCC, accounting for JPY 450/L, while fixed capital investments and maintenance contribute JPY 28/L and JPY 9/L, respectively. Within variable costs, labor accounts for JPY 292/L (65%) and single-use glass bottles for JPY 93/L (21%) (Figure 2). These values indicate that the cost structure is primarily driven by labor and packaging rather than equipment-related costs.

Figure 2.

Breakdown of baseline life cycle cost (LCC) per 1 L of beer. (a) Overall cost structure by category, showing fixed (initial), variable, and maintenance costs as proportions of total cost, (b) Detailed breakdown of variable costs with absolute values (JPY), highlighting labor (JPY 292.18) and glass bottles (JPY 93.03) as dominant contributors. Zero-cost items are shown explicitly for completeness. Total cost is JPY 487 per liter. Charts are displayed side-by-side for comparative clarity.

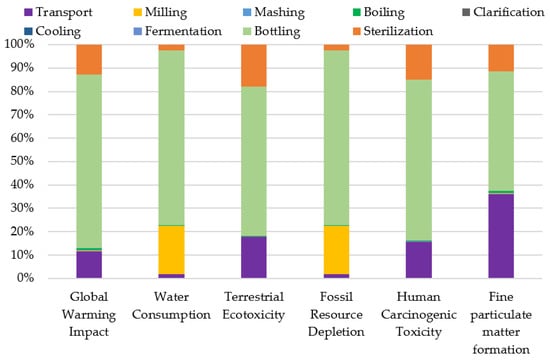

A 1 L volume of bottled craft beer emits 0.52 kg CO2e/L in the truncated cradle-to-gate scope (Figure 3). Packaging and thermal sterilization are the dominant contributors to global warming impact and several other midpoint categories. Glass bottle production and associated packaging account for the largest single share of global warming impact, fossil resource use, and toxicity-related indicators, while heat sterilization using heavy fuel oil is a major source of CO2 and air pollutant emissions. A step-by-step breakdown of all process-level emissions, including transport, brewing stages, packaging, and sterilization, is provided in Supplementary Table S7, which reports the contribution of each unit process to total global warming impact and all other midpoint indicators. Other brewing steps (milling, mashing, boiling, cooling, fermentation) contribute relatively little to total impacts.

Figure 3.

Baseline LCA results (per 1 L beer).

For the remaining ReCiPe midpoint categories—such as water consumption, terrestrial ecotoxicity, fossil resource depletion, human carcinogenic toxicity, and fine particulate matter formation—the same pattern is observed: single-use glass bottles and heavy fuel oil dominate the impacts. The complete numerical baseline results for all 18 midpoint categories are provided in Supplementary Table S7.

3.2. Scenario Comparison

To assess sustainability trade-offs in Japanese craft beer production, three alternative scenarios were modeled against the baseline: (1) local rice substitution, (2) on-site consumption and direct sales, and (3) cooperative brewing and logistics. Each scenario targets different hotspots and alters the life cycle cost (LCC) and global warming impact to varying degrees.

Scenario 1 (local rice substitution) replaces 30% of imported barley malt with domestically grown rice, while keeping the total fermentable input constant (0.14 kg malt and 0.06 kg rice per liter). Within the truncated cradle-to-gate boundary, which includes transport of imported malt but excludes agricultural cultivation, this scenario primarily affects international shipping and domestic processing. The resulting global warming impact is 0.55 kg CO2e/L compared with 0.52 kg CO2e/L in the baseline, and the LCC is JPY 492/L compared with JPY 487/L, indicating small increases in both emissions and cost within the modeled boundary. Sensitivity checks that approximate cultivation emissions for barley and rice using literature-based factors (Supplementary Tables S2 and S3) suggest that including upstream farming would further increase the relative global warming impact of Scenario 1, so it is unlikely to outperform the baseline even under a cultivation-inclusive perspective. Direct field monitoring of all cultivation emissions was beyond the scope of this brewery-level LCA–LCC study; instead, we relied on literature-based inventory data to represent upstream rice and barley cultivation in the sensitivity analysis.

Scenario 2 (direct sales expansion) assumes that 50% of beer volume is sold via draft for on-site consumption and 50% via bottled distribution. The use of single-use glass bottles is reduced by approximately 50%, from 3.0 bottles per liter (330 mL × 3) to 1.5 bottles per liter, corresponding to the 50% draft sales share in this scenario. Thermal sterilization is largely avoided for the draft portion. As a result, Scenario 2 produces a clear positive environmental impact, with global warming impact decreasing from 0.52 to 0.29 kg CO2e/L (−44%) and LCC from JPY 487 to JPY 435/L (−11%). These reductions are mainly driven by decreased glass packaging and heavy fuel oil use, with additional savings from reduced labor requirements in packaging. Importantly, this scenario does not involve increasing the total production volume; instead, it reallocates the same production output between draft and bottled formats, which explains why costs and emissions decline without requiring higher production. This pattern is consistent with previous work identifying packaging as a dominant contributor to beer life cycle impacts. However, Monte Carlo results indicate more moderate environmental and economic improvements, with a mean global warming impact of approximately 0.47 kg CO2e/L and a mean cost of about 475 JPY/L, reflecting the influence of variability in packaging, labor, and draft sale parameters.

Scenario 3 (Joint logistics) maintains the same packaging and sterilization configuration as the baseline but reduces labor requirements and outbound transport intensity through cooperative brewing and shared logistics. The global warming impact slightly decreases to 0.50 kg CO2e/L, while cost falls to JPY 399/L (−18% relative to the baseline). Thus, the scenario delivers a substantial cost reduction with only a modest change in emissions, reflecting the limited impact of logistics and labor measures when packaging and energy use remain unchanged. This demonstrates that cooperative arrangements can meaningfully improve the economic viability of small breweries even if their environmental benefits are limited.

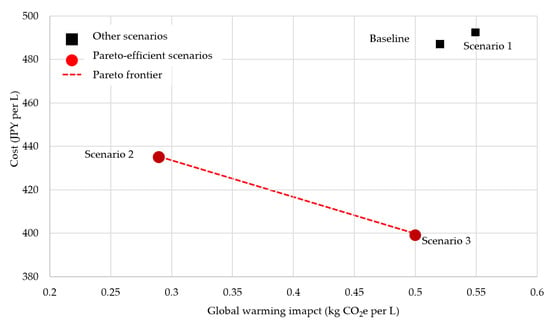

Figure 4 illustrates these trade-offs: Scenario 2 occupies the most favorable lower-left quadrant, achieving both low global warming impact and low cost (Pareto-optimal). Scenario 3 is economically optimal but offers limited emissions reduction, while Scenario 1 performs worse than the baseline in both dimensions. Packaging-focused strategies (Scenario 2) deliver the highest dual benefit, while labor-focused strategies (Scenario 3) improve financial sustainability. Localization efforts (Scenario 1), though well-intentioned, reinforce the importance of data-driven evaluation, as they may inadvertently increase the environmental impact due to crop-level emission profiles (e.g., methane from rice paddies).

Figure 4.

Cost–impact trade-offs for the baseline and three scenarios, expressed per 1 L of bottled beer at the brewery gate.

3.3. Sensitivity Analysis

The sensitivity analysis examined how variations in key parameters affect global warming impact and cost per liter (Supplementary Figure S1). Among the parameters tested, packaging-related variables had the strongest effect on global warming impact. A ±30% change in glass bottle mass caused global warming impact to vary from approximately 0.43 to 0.66 kg CO2e/L, reflecting the high contribution of bottle manufacturing. Increasing the share of on-site sales (reducing packaging and transport) lowered the global warming impact from roughly 0.64 to 0.30 kg CO2e/L across the tested range.

On the cost side, labor cost was the most influential parameter. A ±30% change in labor expenses shifted the total cost from about JPY 390 to JPY 585/L. Changes in bottle mass resulted in cost variations between roughly JPY 465 and JPY 509/L, and the on-site sales share produced a cost range of approximately JPY 455 to JPY 504/L.

By comparison, rice substitution (0–40%) and fuel oil use (±30%) produced only modest changes: the global warming impact remained within 0.50–0.54 kg CO2e/L and cost within about JPY 484–494/L. Overall, the sensitivity analysis shows that global warming impact and LCC respond most strongly to packaging (especially bottle weight) and labor cost, while energy use and raw material sourcing have comparatively smaller effects.

3.4. Uncertainty Analysis

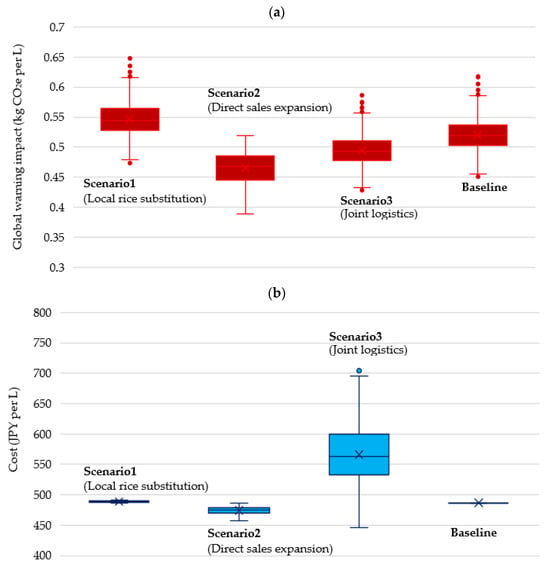

To evaluate the robustness of the scenario comparison under parameter uncertainty, a Monte Carlo simulation with 1000 iterations was conducted. Uncertainty was propagated across both background LCI parameters—such as emission factors for materials, energy, and transport—and foreground assumptions, including labor costs, distribution ratios, ingredient sourcing, and production scale. Triangular distributions were used for cost and operational variables, lognormal distributions for emission-related parameters, and beta distributions for allocation ratios such as the direct sales share. A weak correlation between labor cost and production efficiency was modeled via a linked triangular scale adjustment. The resulting distributions for global warming impact and cost are visualized as boxplots in Figure 5, and summary statistics (mean, median, standard deviation, and 5th–95th percentiles) are reported in Supplementary Table S8.

Figure 5.

Boxplot of Monte Carlo results for (a) global warming impact and (b) life cycle cost (LCC) across baseline and scenarios.

For global warming impact, the mean values from the Monte Carlo analysis are 0.52 kg CO2e/L (baseline), 0.55 kg CO2e/L (Scenario 1), 0.47 kg CO2e/L (Scenario 2), and 0.49 kg CO2e/L (Scenario 3). The corresponding 5th–95th percentile ranges are approximately 0.48–0.56, 0.50–0.59, 0.42–0.51, and 0.45–0.54 kg CO2e/L, respectively.

For life cycle cost, the mean values are JPY 487/L (baseline), JPY 489/L (Scenario 1), JPY 475/L (Scenario 2), and JPY 566/L (Scenario 3). The 5th–95th percentile ranges were as follows: Scenario 1 (487–491 JPY/L), Scenario 2 (464–484 JPY/L), and Scenario 3 (489–646 JPY/L). The baseline cost was modeled as a fixed value with no variation (487–487 JPY/L) because it was based on direct operational data from the case brewery and was not subject to uncertainty in this analysis. This also allowed for a clearer comparison of scenario-induced cost variability.

These ranges indicate that Scenario 2 consistently outperforms the baseline in both indicators, whereas Scenario 1 shows no improvement, and Scenario 3 exhibits substantially higher expected costs while providing only modest environmental gains.

4. Discussion

This study assessed the environmental and economic trade-offs of four production strategies in the Japanese craft beer sector using an integrated LCA–LCC approach coupled with sensitivity and uncertainty analysis. Across all scenarios, packaging and labor consistently emerged as dominant hotspots, confirming that sustainability improvements in small-scale brewing hinge primarily on these two levers. These findings are consistent with prior beverage LCAs that identify single-use glass bottles and manual labor as key contributors to both environmental and economic impacts [34,35], and they are broadly aligned with recent assessments of beverage and food production systems in Japan and other Asian countries, where packaging and process energy similarly play a central role. In the Japanese craft beer context, many breweries operate at relatively low production volumes and under tight capital constraints, making extensive automation economically unattractive; as a result, production remains manual and labor-intensive even though automation could, in principle, reduce effort and processing time.

Scenario 2, focused on on-site consumption and direct sales, achieved substantial reductions in both global warming impact and production cost precisely because it eliminated these two hotspots. By replacing single-use bottles with reusable draft systems and removing the need for fuel-intensive pasteurization, this scenario directly addressed the most impactful stages of the baseline process. The magnitude of the deterministic improvement—nearly halving total emissions (0.29 vs. 0.52 kg CO2e/L)—is consistent with previous studies reporting that packaging dominates life cycle impacts in brewing and that reuse can reduce GHG emissions by 40–60% [36,37,38]. When Monte Carlo uncertainty is considered, Scenario 2 still remains the lowest-emission option and generally the lowest-cost option on average, although its advantage over the baseline is more moderate than suggested by the deterministic results. In the Japanese context, where many breweries already operate taprooms or engage in regional tourism [39], expanding such models offers a feasible, high-impact pathway toward carbon reduction and profitability. At the same time, the practical scalability of Scenario 2 is conditional on regulatory and institutional constraints specific to Japan, including licensing requirements under the Liquor Tax Act, taproom operation rules, and local public health regulations that can limit the expansion of on-site draft sales.

Scenario 3, modeling cooperative brewing and shared logistics, primarily targets labor and capital efficiency—again aligning with one of the identified hotspots. In the deterministic scenario analysis, it delivered notable cost reductions by improving labor productivity and sharing fixed assets, paralleling findings from North American and European microbreweries, where contract brewing and shared facilities have enabled lower unit costs and improved competitiveness [36,38]. However, the environmental benefits remained modest because the scenario did not mitigate packaging or thermal energy use. Moreover, the Monte Carlo uncertainty analysis revealed that these cost advantages are not robust: once parameter uncertainty is propagated, Scenario 3 can entail substantially higher expected costs than the baseline while still offering only limited environmental gains. This underscores a critical distinction: economic resilience can be achieved through collaboration, but meaningful environmental gains require addressing material and energy intensity. In addition to these environmental–economic trade-offs, Scenario 3 also carries potential social implications. Reduced labor requirements may alleviate excessive workloads and improve operational flexibility for small breweries yet could also raise concerns about employment stability depending on how collaborative models are implemented. Although social impacts were not quantitatively assessed in this study, these considerations highlight the need for future research that explicitly evaluates the social pillar of sustainability alongside environmental and economic outcomes.

By contrast, Scenario 1, involving partial substitution of imported barley malt with locally grown rice, showed a slight increase in global warming impact despite reduced transport distance because the system boundary excluded cultivation emissions and transport savings were minor. Although local sourcing is often perceived as sustainable, this finding highlights the importance of defining full life cycle boundaries. In this study, the core LCA model uses a truncated cradle-to-gate boundary that excludes agricultural cultivation. References to upstream emissions in this section are based on a one-time supplemental sensitivity analysis and are not part of the primary model. Similar observations have been made in other food sectors where localization produces limited or even adverse climate effects [40]. In our supplementary analysis (Supplementary Tables S2 and S3), cultivation emissions for barley and rice were added using literature-based factors and scaled to per-liter inputs. The results showed that Scenario 1’s total global warming impact could increase by up to ~0.29 kg CO2e/L, reflecting the high emission intensity of paddy rice. However, these supplemental values are only intended to contextualize the model results and do not alter the scenario ranking or hotspot identification. The main conclusions remain unchanged: raw material substitution offers limited benefit compared to the more impactful improvements achieved through packaging reuse and energy efficiency. Accordingly, the implications of Scenario 1 should be interpreted as brewery gate comparisons rather than generalized statements about the overall sustainability of domestic rice sourcing. Within the environmental and economic pillars assessed in this LCA–LCC framework, Scenario 1 therefore cannot be regarded as an improvement in quantitative sustainability performance. Local ingredient substitution may still be pursued for other normative reasons—such as supporting regional farmers, strengthening regional branding, or enhancing perceived authenticity—but these social and cultural dimensions lie beyond the quantitative scope of the present analysis.

In addition to global warming impact, the results for other midpoint impact categories—such as water consumption, terrestrial ecotoxicity, fossil resource depletion, human carcinogenic toxicity, and fine particulate matter formation—showed broadly similar patterns. In nearly all categories, single-use glass bottles and heavy fuel oil for pasteurization remained the dominant contributors, reinforcing that these processes represent structural hotspots across multiple environmental dimensions, not only climate change. Scenario 2 reduced impacts consistently across these categories, whereas Scenario 3 showed limited environmental improvement. These cross-category consistencies strengthen the robustness of the overall conclusions.

The methodological integration of deterministic scenario modeling, sensitivity analysis, and Monte Carlo-based uncertainty simulation enabled a robust comparison of outcomes and their variability. This multi-layered approach is aligned with best practices in applied LCA and increases confidence in strategic recommendations, particularly for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) in food and beverage sectors with limited decision support tools [41,42,43]. In this framework, one-way sensitivity analysis primarily identifies packaging and labor as the dominant drivers of environmental and economic performance, while Monte Carlo simulation characterizes how uncertainty in key parameters affects the relative ranking and robustness of the modeled scenarios.

4.1. Limitations

Nevertheless, several limitations must be acknowledged. First, Scenario 1 is evaluated within a truncated cradle-to-gate boundary that excludes agricultural cultivation, meaning that its environmental performance cannot be generalized beyond brewery-level processes. Because upstream emissions differ substantially between barley and rice cultivation in Japan and Asia—for example, methane emissions from paddy systems and higher fertilizer inputs reported in regional LCAs—the relative ranking of Scenario 1 would likely differ under a full cradle-to-grave assessment. Second, the analysis is based on a single case study, which may not represent Japan’s regional diversity in energy mixes, ingredient supply chains, or market structures. The cradle-to-gate scope also excludes downstream processes such as distribution, refrigeration in retail, and end-of-life packaging treatment, all of which can alter total life cycle impacts in real settings. Third, Scenario 2 is subject to real-world regulatory constraints in Japan, including requirements under the Liquor Tax Act, licensing rules for taproom operation, and local public health regulations that may restrict on-site consumption or draft beer sales. These institutional factors influence the practical feasibility of increasing direct sales, and regional variation in demand and tourism flows may further shape adoption potential. Fourth, several scenario parameters—such as cooperative labor efficiency, shared logistics performance, and bottle return rates—were derived from secondary sources or expert judgment. Although uncertainty analysis was used to assess their robustness, these assumptions introduce inevitable simplifications relative to actual brewery operations. Finally, the broader Asian context warrants further consideration. Prior LCAs in Japan, Korea, and Southeast Asia indicate that energy intensity, packaging systems, and grain production methods differ meaningfully from European and North American cases commonly cited in the literature. Incorporating region-specific pathways—such as reusable bottle infrastructures in East Asia or decarbonizing industrial heat sources in Japan—would strengthen the contextual relevance of future analyses.

4.2. Future Research Directions

Building on these findings and limitations, several avenues for future research can be identified. First, the single-brewery focus of this study suggests the need for multi-brewery comparative analyses that include different scales, technologies, and regional contexts within Japan and other Asian countries. Such cross-case studies would make it possible to examine how variations in energy mixes, packaging systems, labor organization, and market structures influence the environmental and economic performance of craft beer production and would help to clarify which of the observed trade-offs are case-specific and which are more general.

Second, the truncated cradle-to-gate boundary applied here could be extended toward a full cradle-to-grave assessment. Future work may explicitly integrate upstream cultivation processes for barley and rice under region-specific conditions, as well as downstream stages such as distribution, cold-chain logistics, retail refrigeration, and end-of-life management of packaging. Incorporating these additional life cycle stages would allow for a more comprehensive evaluation of whether strategies such as local sourcing, reusable containers, or logistics cooperation remain effective when the entire supply chain is considered.

Third, several technological and organizational options mentioned qualitatively in this study—such as reusable or lightweight packaging systems, alternative container materials, increased use of renewable energy for process heat, and partial automation of labor-intensive operations—were not modeled quantitatively. Scenario-based LCA–LCC analyses that explicitly simulate these options, possibly in combination with direct-sales or cooperative models, would provide more detailed guidance to breweries on feasible transition pathways.

Finally, the potential social implications of different production and collaboration strategies, as well as the role of policy and regulation, warrant more systematic investigation. Future research could, for example, combine environmental and economic assessment with social impact metrics to evaluate how cooperative brewing, shared logistics, or expanded taproom operations affect employment stability, working conditions, and regional development. In addition, integrating policy scenarios—such as adjustments to the Liquor Tax Act, incentives for reusable packaging, or support for decarbonizing industrial heat—would help clarify under which institutional conditions small breweries can realistically adopt low-impact, resilient business models.

5. Conclusions

This study presented an integrated LCA and LCC of beer production at a Japanese craft brewery, focusing on Ishikawa Shuzo as a representative case. The baseline results revealed that the environmental burden is dominated by single-use glass bottles and heavy fuel oil-based sterilization, while the economic burden is dominated by labor and packaging costs. These findings underscore the dual-hotspot nature of small-scale breweries, where environmental and economic challenges converge around packaging and labor.

The scenario analysis showed that not all commonly promoted sustainability measures yield meaningful improvements under Japan’s structural conditions. Scenario 1, which involved partial substitution of imported malt with domestic rice, did not lead to clear environmental or economic benefits within the defined system boundary. By contrast, Scenario 2, which expanded on-site consumption and direct draft sales, demonstrated simultaneous environmental and economic advantages by reducing reliance on single-use bottles and eliminating thermal sterilization for the draft portion. While Scenario 3 offers some operational cost-saving potential under specific conditions, the overall results indicate that rethinking packaging formats and sales channels—particularly through direct sales and reusable systems—is the most reliable path to sustainability.

Taken together, these results indicate that sustainability improvements in small-scale brewing are most effectively achieved by rethinking packaging formats and sales channels rather than focusing solely on raw material substitution or incremental energy changes. In practical terms, shifting a portion of production from single-use bottles to draft or refillable systems, combined with expanding direct-to-consumer pathways, offers a promising strategy for breweries seeking to strengthen both their environmental and economic performance. While cooperative brewing may help reduce costs under specific conditions, our uncertainty analysis suggests that its effectiveness is not consistent. Therefore, its role may be more supportive than transformative.

Overall, this study provides quantitative evidence that packaging-related interventions and labor efficiency are the most powerful levers for improving sustainability in small-scale breweries under the modeled conditions. The implications are particularly relevant for settings similar to the Japanese craft beer context analyzed here; extending the conclusions beyond these conditions should be done with caution, given the single-case design and truncated system boundary. While sustainability encompasses environmental, economic, and social dimensions, this study focused on the first two pillars; incorporating social aspects—such as labor conditions, local employment, and the impacts of collaborative models—represents an important direction for future research. The broader implication is that data-driven, systems-based strategies—rather than symbolic local sourcing—offer the most reliable path toward sustainable craft beer production. Future research should extend this integrated approach to multiple breweries and include downstream processes, ultimately informing regional and national strategies aligned with SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production), SDG 9 (Industry, Innovation, and Infrastructure), and SDG 13 (Climate Action).

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/su172411003/s1, Figure S1: Sensitivity analysis results for (a) global warming potential (GWP) and (b) life cycle cost (LCC); Table S1: Life cycle inventory for 1 L of beer production (Ishikawa Shuzo, 2024); Table S2: Cultivation impacts for malted barley and Japanese rice (per 1 L beer); Table S3: Effect of adding cultivation emissions for malted barley and Japanese rice on the global warming potential (GWP) of 1 L of beer; Table S4: Life cycle costing structure per 1 L of beer (Ishikawa Shuzo, 2024); Table S5: Complete ReCiPe 2016 midpoint impact results for all 18 categories (per 1 L of beer); Table S6: Scenario parameters and outcomes (per 1 L of beer); Table S7: Stochastic input parameters, distributions, and correlations used in the Monte Carlo simulation; Table S8: Monte Carlo summary statistics for GWP and cost (1000 iterations).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.S.; methodology, S.O. and Y.S.; software, S.O.; validation, Y.S.; formal analysis, S.O.; investigation, Y.S.; resources, Y.S.; data curation, S.O.; writing—original draft preparation, S.O.; writing—review and editing, Y.S.; visualization, S.O.; supervision, K.M. and Y.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

Co-author Koichi Maesako is the chief brewer at Ishikawa Shuzo Co., Ltd., which served as the case study site for this research. However, Ishikawa Shuzo had no role in the study design, data analysis, interpretation, or the decision to publish the results. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Garavaglia, C.; Swinnen, J.F.M. (Eds.) Economic Perspectives on Craft Beer: A Revolution in the Global Beer Industry; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobbi, L.; Stanković, M.; Ruggeri, M.; Savastano, M. Craft Beer in Food Science: A Review and Conceptual Framework. Beverages 2024, 10, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Bauman, M.J.; Ponting, S.S.-A.; Slevitch, L.; Webster, C.; Kirillova, K. Authenticity of Craft Brewery Visitor Experience: A Scale Development Study. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2023, 49, 386–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, P.H.; Christensen, J.L. Industry Evolution, Resilience, and Regional Embeddedness: The Case of the Danish Microbrewing Industry. Reg. Stud. 2023, 57, 1924–1936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talmage, C.A.; Bletscher, C.; Newton, J.D.; Mars, M.M. Community Development on Tap: How Local Breweries Provide Creative Community-Centered Spaces and Initiatives for Advancing Economic and Social Capital. Community Dev. 2025, 56, 815–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, R.; Miller, M. Provenance Representations in Craft Beer. Reg. Stud. 2023, 57, 1995–2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erhardt, N.; Martin-Rios, C.; Bolton, J.; Luth, M. Doing Well by Creating Economic Value through Social Values among Craft Beer Breweries: A Case Study in Responsible Innovation and Growth. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amienyo, D.; Azapagic, A. Life cycle environmental impacts and costs of beer production and consumption in the UK. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2016, 21, 492–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Ascenzo, F.; Vinci, G.; Maddaloni, L.; Ruggeri, M.; Savastano, M. Application of Life Cycle Assessment in Beer Production: Systematic Review. Beverages 2024, 10, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojnarowska, M.; Muradin, M.; Paiano, A.; Ingrao, C. Recycled Glass Bottles for Craft-Beer Packaging: How to Make Them Sustainable? An Environmental Impact Assessment from the Combined Accounting of Cullet Content and Transport Distance. Resources 2025, 14, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pino, A.; Pino, F.J.; Cabello González, G.M.; Navas, S.J.; Guerra, J. PVT Potential for a Small-Scale Brewing Process: A Case Study. Therm. Sci. Eng. Prog. 2024, 53, 102670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markovic, M.; Li, A.; Ayall, T.A.; Watson, N.J.; Bowler, A.L.; Woods, M.; Edwards, P.; Ramsey, R.; Beddows, M.; Kuhnert, M.; et al. Embedding AI-Enabled Data Infrastructures for Sustainability in Agri-Food: Soft-Fruit and Brewery Use Case Perspectives. Sensors 2024, 24, 7327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umemura, M.; Slater, S. Institutional Explanations for Local Diversification: A Historical Analysis of the Japanese Beer Industry, 1952–2017. J. Strateg. Mark. 2021, 29, 71–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewing Chemical Organization of Japan, 2021 Annual Report. Available online: https://www.brewers.or.jp/bcoj/pdf/2021_report_English.pdf (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- Morgan, D.; Styles, D.; Lane, E. Packaging Choice and Coordinated Distribution Logistics to Reduce the Environmental Footprint of Small-Scale Beer Value Chains. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 307, 114591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White Paper on Small and Medium Enterprises in Japan 2021, Trends in Small and Medium Enterprises in Fiscal Year 2020. Available online: https://www.chusho.meti.go.jp/pamflet/hakusyo/2021/PDF/chusho/03Hakusyo_part1_chap1_web.pdf (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- OECD Environmental Performance Reviews: Japan 2025. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/content/dam/oecd/en/publications/reports/2025/03/oecd-environmental-performance-reviews-japan-2025_947dc3da/583cab4c-en.pdf (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- GlobalData. Japan Beer and Cider Market Analysis by Category and Segment, Company and Brand, Price, Packaging and Consumer Insights. Available online: https://www.globaldata.com/store/report/japan-beer-and-cider-market-analysis/ (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- Pasquet, P.-L.; Villain-Gambier, M.; Trébouet, D. By-Product Valorization as a Means for the Brewing Industry to Move toward a Circular Bioeconomy. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossini, F.; Virga, G.; Loreti, P.; Iacuzzi, N.; Ruggeri, R.; Provenzano, M.E. Hops (Humulus lupulus L.) as a Novel Multipurpose Crop for the Mediterranean Region of Europe: Challenges and Opportunities of Their Cultivation. Agriculture 2021, 11, 484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halland, H.; Martin, P.; Dalmannsdóttir, S.; Sveinsson, S.; Djurhuus, R.; Thomsen, M.; Wishart, J.; Reykdal, Ó. Transnational Cooperation to Develop Local Barley-to-Beer Value Chains. Open Agric. 2020, 5, 138–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nettesheim, P.M.; Burggräf, P.; Steinberg, F. Enhancing Brewery Logistics with Smart Kegs: A Simulation Study. J. Transp. Supply Chain Manag. 2024, 18, a1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Said, Z.K. Craft Beer and the Rising Tide Effect: An Empirical Study of Sharing and Collaboration among Seattle’s Craft Breweries. Lewis Clark Law Rev. 2019, 23, 355. [Google Scholar]

- Farcas, A.C.; Socaci, S.A.; Chiș, M.S.; Pop, O.L.; Fogarasi, M.; Păucean, A.; Igual, M.; Michiu, D. Reintegration of Brewers Spent Grains in the Food Chain: Nutritional, Functional and Sensorial Aspects. Plants 2021, 10, 2504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arvanitoyannis, I.S. ISO 14040: Life Cycle Assessment (LCA)–Principles and Guidelines. In Waste Management for the Food Industries; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2008; pp. 97–132. Available online: http://ndl.ethernet.edu.et/bitstream/123456789/20466/1/136.pdf#page=122 (accessed on 18 February 2025).

- del Hierro, Ó.; Gallejones, P.; Besga, G.; Artetxe, A.; Garbisu, C. A Comparison of IPCC Guidelines and Allocation Methods to Estimate the Environmental Impact of Barley Production in the Basque Country through Life Cycle Assessment (LCA). Agriculture 2021, 11, 1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hokazono, S.; Hayashi, K. Variability in Environmental Impacts during Conversion from Conventional to Organic Farming: A Comparison among Three Rice Production Systems in Japan. J. Clean. Prod. 2012, 28, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hokazono, S.; Hayashi, K. Life Cycle Assessment of Organic Paddy Rotation Systems Using Land- and Product-Based Indicators: A Case Study in Japan. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2015, 20, 1061–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekonnen, M.M.; Hoekstra, A.Y. The Green, Blue and Grey Water Footprint of Crops and Derived Crop Products. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2011, 15, 1577–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshikawa, N.; Ikeda, T.; Amano, K.; Fumoto, T. Life-Cycle Assessment of Ecologically Cultivated Rice Applying DNDC-Rice Model. In Proceedings of the EcoBalance 2012 Conference, Yokohama, Japan, 20–23 November 2012; Available online: https://www.ritsumei.ac.jp/se/rv/amano/pdf/2012EBJ-yoshikawanaoki.pdf (accessed on 20 May 2025).

- Masuda, K. Eco-Efficiency Assessment of Intensive Rice Production in Japan: Joint Application of Life Cycle Assessment and Data Envelopment Analysis. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huijbregts, M.A.; Steinmann, Z.J.; Elshout, P.M.; Stam, G.; Verones, F.; Vieira, M.D.M.; Hollander, A.; Ziip, M.; van Zelm, R. ReCiPe 2016: A Harmonized Life Cycle Impact Assessment Method at Midpoint and Endpoint Level Report I: Characterization. 2016. Available online: https://rivm.openrepository.com/entities/publication/3d19272d-3ee1-4d95-bbc7-3ad21f0a769e (accessed on 20 May 2025).

- França, W.T.; Barros, M.V.; Salvador, R.; de Francisco, A.C.; Moreira, M.T.; Piekarski, C.M. Integrating life cycle assessment and life cycle cost: A review of environmental-economic studies. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2021, 26, 244–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marrucci, L.; Daddi, T.; Iraldo, F. Identifying the Most Sustainable Beer Packaging through a Life Cycle Assessment. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 948, 174941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brewers Association. 2024 Annual Report. Available online: https://www.brewersassociation.org/annual-report/2024-annual-report/ (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Cole, M.T.; McCullough, M. California Beer Price Posting: An Exploratory Analysis of Pricing along the Supply Chain. J. Wine Econ. 2023, 18, 205–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prim, A.L.; Sarma, V.; de Sá, M.M. The Role of Collaboration in Reducing Quality Variability in Brazilian Breweries. Prod. Plan. Control 2021, 34, 1192–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, L.M.; da Silveira, A.B.; Monticelli, J.M.; Kretschmer, C. Microfoundations of Dynamic Coopetition Capabilities in Firms from a Microbrewery Cluster. REGE Rev. Gestão 2023, 30, 190–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cracking Open Japan’s Craft Beer Market. Available online: https://www.usdajapan.org/wpusda/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/89852e59aaf6cee9d901f546e759b2bc.pdf (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- McDonagh, K.; Zhang, R.; Merkouri, L.-P.; Arnell, M.; Hepworth, A.; Duyar, M.; Short, M. Lowering the Carbon Footprint of Beer through Waste Breadcrumb Substitution for Malted Barley: Life Cycle Assessment and Experimental Study. Clean. Environ. Syst. 2024, 15, 100241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Economic and Earth-Friendly Beer Keg. Available online: https://www.micromatic.com/en-us/learn/dispensing-knowledge/learning-resource-center/the-economic-and-earth-friendly-beer-keg (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Notarnicola, B.; Sala, S.; Anton, A.; McLaren, S.J.; Saouter, E.; Sonesson, U. The Role of Life Cycle Assessment in Supporting Sustainable Agri-Food Systems: A Review of the Challenges. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 140, 399–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marson, A.; Zuliani, F.; Fedele, A.; Manzardo, A. Life Cycle Assessment-Based Decision Making under Methodological Uncertainty: A Framework Proposal. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 445, 141288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).