1. Introduction

Megaconstellations refer to the deployment in orbit of enormous satellite networks, often in Low Earth Orbit (LEO). Their main purpose is to ensure the effectiveness of global communications, data services, and other technological capabilities associated with the ICT sphere. The definition of megaconstellations found in the literature broadens the scope of use of these systems, which sometimes consist of hundreds or even thousands of satellites working in tandem to assure uninterrupted ICT service coverage [

1]. The goal of megaconstellations extends across several industries beyond telecommunications; in this regard, Earth observation and scientific research—in the broadest sense of the term—should also be considered [

2]. The idea of megaconstellations is particularly significant for global connection since it ensures that good service is available even in the most remote corners of the Earth. However, the existence of such systems is not free from economic and environmental difficulties [

3]. For this reason, understanding the expenses created during the whole network life cycle (LCC) becomes critical. Life Cycle Costing (LCC) provides a complete methodology for examining the economic and financial implications of megaconstellations, enabling decision-making processes for initial investment assessments, running costs, and potential long-term profits [

4]. Additionally, the LCC technique enables all stakeholders to comprehend the comprehensive cost framework related to a satellite’s life cycle, including its design, production, operation, and eventual deorbiting phase [

5]. This article seeks to address the following research question: “How can a cost-budgeting process be designed to ensure fairness, efficiency, and sustainability within cooperative coalitions, while accounting for the potential existence of free riders and capacity limitations?” To this purpose, after an exhaustive assessment of the current literature, a Life Cycle Costing model based on the processes of Cooperative Game Theory will be given, with the aim of proving the relevance of a synergistic approach among diverse operators in the sector. This model is then evaluated on a specific case study in order to validate the soundness of the methodology itself. The contribution of this research is manifold. At the theoretical level, the study proposes an integrated framework connecting Life Cycle Costing with cooperative game theory, thereby filling the gap in the analytical models that are capable of assessing the fairness of cost allocation and coalition stability of megaconstellation programs. At the practical level, it will show how this integrated methodology can support decision-makers in managing multi-operator constellations by quantifying economic trade-offs, environmental externalities, and strategic risks such as free-rider behavior. Together, these features will contribute to the establishment of a more comprehensive evaluation tool for governments, regulators, and corporate operators interested in large-scale space infrastructures. The rest of the document is structured as follows:

Section 2 presents an overview of the literature about megaconstellations, Life Cycle Costing, and cooperative techniques.

Section 3 outlines the methodological approach, both with regard to LCC formulation and game-theoretic components.

Section 4 provides the case study and analyzes the application of the model to three operators.

Section 5 extends a larger assessment of findings, concentrating on collaboration, free-riding, and strategic ramifications.

Section 5 wraps up the work by discussing the main results, their practical uses, their limits, and the directions for future research.

2. Literature Review

Satellite megaconstellations have quickly become an important part of the modern space industry. They have changed the way broadband is delivered, global telecommunications, Earth observation, and the economics of space infrastructure in general. These systems are intended to provide high-frequency data services, low-latency connectivity, and continuous worldwide coverage. In most cases, there are hundreds or thousands of satellites in Low Earth Orbit (LEO) [

1,

2]. However, concerns about their long-term economic viability and effects on the orbital environment have grown as a result of their increasing size and operational complexity. Therefore, it is more important than ever to have analytical tools that can examine these systems in depth over their entire life cycle. Life Cycle Costing (LCC) has become a key way to evaluate space missions over the past few decades [

5,

6]. It helps make decisions from the early stages of design to manufacturing, deployment, in-orbit operations, and end-of-life disposal. Traditional LCC applications have focused on single-mission or single-operator initiatives, typically characterized by relatively stable operational profiles and limited constellation sizes. Usually, these models include engineering–economic analyses that examine aspects like reliability needs, mass limits, choosing a launch vehicle, weighing performance against cost, and costs that arise during the mission [

7,

8]. Nevertheless, within the framework of extensive constellations, most of these structures inherently depend on assumptions that have become obsolete. They usually do not account for the fact that satellites in crowded orbits share risks, treat operators as separate entities, and assume that costs occur without regard to what other people do. In megaconstellations, where many stakeholders work together in the same orbital shells, costs related to avoiding collisions, deorbiting, operational reliability, and managing the ground segment are all closely linked. Existing LCC models also have trouble with the changing nature of constellation replenishment cycles, phased deployment plans, technology improvements, and the problems with scaling that come with very large fleets [

9,

10]. In addition to operational and economic considerations, environmental concerns have become a significant focus in the scholarly discourse on megaconstellations [

11]. Much research shows that the rapid rise in Low Earth Orbit (LEO) traffic increases the likelihood of collisions, debris buildup in orbit, and damage to the orbital environment [

3,

12,

13,

14]. Carbon black, alumina particles, and other pollutants are released during launches and atmospheric re-entries, and the infrastructures’ long-term sustainability risks are increased by the inability to guarantee effective end-of-life disposal [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19]. Even though these factors are frequently discussed, they are not often quantified for LCC analyses. The literature often fails to assign monetary value to the externalities associated with orbital congestion, atmospheric pollution, or regulatory non-compliance, opting instead to illustrate environmental impacts through qualitative assessments or risk-based metrics. The lack of monetized environmental components is a major research gap because it limits the ability of LCC frameworks to accurately measure the long-term costs of megaconstellations. Another issue is that there is limited research examining megaconstellations from a strategic or cooperative point of view. Most economic analyses assume that operators will act in a way that is both cooperative and symmetrical, even though they all share the same orbital environment, ground infrastructure, radio frequencies, and rules. In reality, each operator has a number of incentives that do not always work together. Some operators may not invest sufficiently in collision-avoidance techniques, deorbiting technologies, or shared infrastructures. This is because they rely on others to keep orbital safety at acceptable levels. This is why free-riding is a natural part of the megaconstellation context. Additionally, the way risks and costs are shared is usually not equal, and this is affected by factors such as the size of the constellation, the height of the orbit, and how often satellites need to be replaced. There are few attempts in the literature to model cost sharing, coordination breakdowns, coalition building, or incentive systems among different players, even though these issues are important [

20,

21]. Cooperative game theory, prevalent in various network sectors like energy, transportation, and environmental management, has garnered minimal attention in satellite megaconstellations. This indicates a considerable methodological deficiency in comprehending how to attain equitable and stable cooperation within these networks. This review identifies three major problems with the current state of the literature, even though numerous technical and regulatory studies exist. First, standard LCC models do not adequately represent how megaconstellations are connected, involve many stakeholders, and are driven by externalities. The second issue is that cost functions do not sufficiently take into account environmental externalities, even though their importance is recognized. The absence of analytical frameworks that can take into consideration free-rider behavior, strategic interactions, and equitable cost distribution among operators in the same orbital environment is the third—and possibly most important—factor. This study occupies the intersection of these three gaps. The research proposes an innovative approach to evaluate the strategic and economic viability of satellite megaconstellations by integrating a Life Cycle Cost (LCC) model, augmented with environmental impact monetization, within a cooperative game-theoretic framework for coalition analysis and cost distribution. To elucidate the development of more equitable and effective budgeting frameworks for the industry, the emphasis will be on the equitable distribution of costs, the maintenance of cooperation amidst asymmetric incentives, and the potential threat to coalition stability posed by free-rider behavior. Overall, there have been few attempts to combine technical, economic, and regulatory viewpoints into a single analytical model, and the literature is still dispersed throughout these domains. Specifically, previous research hardly ever addressed the strategic interactions that occur when multiple actors share orbital infrastructure, rarely included discounting in multi-operator scenarios, and hardly ever monetized environmental externalities. This emphasizes the necessity of a more thorough and multidisciplinary strategy. The current study fills this gap by evaluating coalition stability, cost allocation equity, and economic sustainability within megaconstellation programs using cooperative game theory and discounted Life Cycle Costing.

3. Materials and Methods

The proposed model aims to address a specific research question: “How is it possible to design a cost-budgeting process that ensures fairness, efficiency, and sustainability within so-called cooperative coalitions, while taking into account the potential presence of free riders and capacity constraints?” This question can be further specified by considering that cooperation among the parties may be assessed in terms of fairness in cost sharing among partners, and that the economic burden of the project will weigh differently depending on whether one or more free riders are present. Moreover, an additional research question that may be posed is whether this model—originally developed specifically for satellite megaconstellations—could also be adopted, with the appropriate adjustments and sector-specific adaptations, in other critical domains such as energy infrastructure. Having made this necessary methodological preamble, the focus now shifts to the mathematical formalization of the proposed model, defining the underlying logic that governs its functioning. Let us consider a finite number of actors, with . A generic actor may decide either to pursue an individual strategy or to collaborate with other partners in order to share the costs. Regardless of the chosen strategy, each operator, for the realization of its satellite megaconstellation, will have to bear.

Development and manufacturing costs of the satellites (

), which include all expenses necessary for the design and physical realization of the satellites comprising the megaconstellation. Taking into account that design costs are calculated based on the hours spent by designers to produce the projects, while materials are purchased as lump-sum items, the formula describing the total development costs is given by the sum of the total expenses for the acquisition of materials (i.e., equipment, hardware, etc.) and the design costs, calculated as the product of the hourly service rate and the total number of hours employed. In symbols:

Launch costs (

). The launch cost takes into account a set of fixed costs as well as the variable cost directly related to the mass of the satellite to be placed in orbit. In symbol

where

denotes the product of the mass of the i-th satellite and the price per kilogram of the material to be launched;

is the fixed mission fee, i.e., the cost to be paid for the launch of the satellite;

represents the logistics cost required to transport the satellite from the factory to the launch site;

is the cost associated with pre-launch verification; and finally,

corresponds to the insurance costs incurred to cover the launch against potential third-party damages.

Operating costs (

). These include all expenses incurred to maintain the satellite in operation throughout its useful life. This will also be expressed as the summation of mission control activities; the fee paid for data transmission

to and from Earth; the cost of the so-called ground segment (

; updates and maintenance of software and operating systems, calculated as a given percentage of the cost of the software installed on board the system

; and finally, the renewal of insurance coverage for in-orbit damages

, calculated as a given percentage of the value of the megaconstellation in orbit. In symbols:

EOL costs (

. These are the end-of-life management costs of the megaconstellation, which account for deorbiting maneuvers, expressed as the product of the amount of propellant required for the deorbiting operations and its unit cost

; ground support activities, calculated as the product of the hours of ground mission dedicated to the deorbiting maneuvers and the hourly rate

; and the insurance cost for damages resulting from the deorbiting process. In symbols:

Environmental costs

. These include all costs related to the production of pollutants generated throughout the entire life cycle of the megaconstellation. In symbols:

where

represents the quantity of the i-th pollutant released into the atmosphere or into space, while

is the unit cost associated with the i-th pollutant. Emission quantification and the application of unit damage prices for each pollutant are used to monetize the environmental cost component. We calculated the primary emission categories for each stage of the satellite life cycle: manufacturing, launch, orbit-keeping, and re-entry (e.g., black carbon from launch burning, alumina particles from ablation during re-entry, NOx from propulsive operations, and CO

2 from satellite production). The accompanying emission variables, which are given in kilos per event or per unit of propellant burned, were acquired from recent space-sustainability studies and publicly accessible environmental-impact databases. In order to reflect damages to the atmosphere, climate, and upper-atmosphere chemistry, each pollutant was then given a monetary value (EUR/kg) based on external-cost coefficients used in environmental economics. The final environmental cost is consequently determined as the product of the mass of the emitted pollutant and its related unit damage cost. This strategy makes it possible to compare diverse operators systematically and incorporate environmental externalities into the LCC framework as a whole.

Each actor

will therefore determine the total cost of its megaconstellation project according to the following formula:

Life Cycle Costing requires a clear understanding of how costs change over time during the system’s operating lifetime, even though the cost components above are shown in an analytical way. We make clear in the amended paper that the megaconstellation’s life cycle is analyzed over a given time horizon, during which time operating and environmental costs are paid on a regular basis. While operational and environmental consequences are produced annually during the span of the satellite’s service life, development, launch, and end-of-life expenditures are still one-time expenses. All costs that arise at various dates are appraised in present-value terms using a typical discounting process to ensure adherence with standard LCC practice. This ensures that the model follows the economic rule that costs incurred later in the project are less important than those incurred at the start. The resulting total life-cycle cost used in the case study is comparable to the discounted sum of all cost categories across the specified lifetime, even though the analytical structure of the cost components stays the same. Without changing the mathematical formulae given earlier in the section, the discounting procedure is now clearly included in the calculation of the LCC figures displayed in the program. Thus, the technique maintains the original formulation of the cost components described in the paper while completely conforming to Life Cycle Cost Analysis (LCCA) criteria. At this point, the model aims to analyze two different types of scenarios. The first, of a non-cooperative nature, assumes that each actor will individually bear the cost of its own project. The second scenario, instead, assumes that the

N actors form a coalition in order to share the overall costs, thus adopting cooperative behavior. When analyzing this second scenario, we assume that, given

actors, there exists a coalition

to which a cost function

is associated, representing the total expenditure that will be incurred if the actors in SSS decide to collaborate. Given the characteristics of

, it is possible to state that it must satisfy the following conditions:

Cooperative Game Theory provides the mathematical tools to examine how the entire cost of a collaborative endeavor might be distributed fairly among the participants. A cooperative game is described by a pair (N,v), where N is the set of actors and v(S) is the cost (or value) generated by any coalition S⊆N. The purpose is to establish an allocation vector that assigns to each actor a cost share reflecting its marginal contribution to the coalition. Reasoning in the abstract, it is evident that the first allocation method to be considered is the equal distribution of costs among the members of

. This allocation can be simply expressed in symbols through the following notation:

Although the presented solution has the advantage of simplicity, it suffers from the drawback of not accounting for the relative weight of each actor. To overcome this limitation, the solution adopted in this work relies on the use of the Shapley value in order to achieve a more consistent cost distribution among the actors. The Shapley value, derived from Cooperative Game Theory, was developed by Lloyd Shapley in 1953 and allows the calculation of the value associated with a given player iii in coalition

S. This value corresponds to the weighted average of the marginal contribution that this player provides to the coalition, taking into account all possible orderings in which the players belonging to the coalition may join. Before adopting the Shapley value as the allocation rule for the cooperative scenario, it is necessary to briefly discuss why this specific method is selected above other well-established cooperative–game solutions. The literature contains a number of allocation mechanisms, including proportionate cost-sharing principles, the Aumann-Shapley value, and the Nucleolus. For example, the Nucleolus aims to reduce player unhappiness but often provides allocations that are hard to comprehend economically, particularly when coalitions demonstrate asymmetric marginal contributions. Although it works well in continuous production situations, the Shapley value is built on differential cost structures that are incompatible with satellite megaconstellations’ discrete and modular construction. The Shapley value, on the other hand, assures stability and fairness under symmetric conditions by publicly revealing each actor’s marginal contribution across all feasible coalition formations. Its axiomatic foundations include efficiency, symmetry, linearity, and the null-player property. This makes it especially useful for circumstances where actors contribute different amounts to the expenses of development, launch, operation, and the environment. The Shapley value is chosen as the major allocation mechanism in this study due to these qualities as well as the requirement for a rule that is consistent, repeatable, and interpretable among different operators. In symbols, the Shapley value is expressed through the following formula:

where

is the set of all players;

is a sub-coalition that does not contain player ;

is the payoff or value obtained from coalition ;

is the size of coalition ;

is the total number of players in the group.

When considering a cooperative process, it is also important to take into account the case in which one or more actors of a given project decide to participate without cooperating. In the proposed model, this is addressed by considering a specific subset of

, denoted by

, with

, representing the free riders. In this case, the total cost will be borne only by the so-called “paying” actors, defined as

. This corresponds to the so-called competitive game scenario with free riders, which will follow the methodological steps described below; it is not a cost function but a proportionality factor used to weight the buy-in distribution when more than one free rider is present. It ensures that the additional expense is spread proportionally among the paying actors. First, using Equation (10), we calculate the payments made exclusively by the paying participants in the coalition. If we denote by

the payments associated with the i-th paying actor, then by applying the Shapley value to the cooperative game restricted to the paying actors, we obtain:

Taking into account the inclusion of a free rider in the process, we proceed to determine the so-called overall buy-in, understood as the extra cost that the participants will have to bear for the inclusion of such an actor. In general terms, the buy-in can be described by the following relation:

Taking into account that the buy-in is divided among the participants in the game according to a given weight

with

then

Assuming that the payment can be allocated according to a proportionality criterion equal to

It can be stated that each paying actor will have to bear a cost equal to

and that each paying actor will incur, as a penalty due to the presence of the free rider, a value equal to

At this point, considering that the objective of each paying actor is to minimize the penalty incurred through an equitable distribution of the additional costs, and that

represents the maximum cost that the i-th actor is willing to bear, we can introduce an optimization mechanism aimed at minimizing the maximum relative penalty of the allocation

among the payments, while ensuring fairness in the distribution and compliance with the spending capacity constraints of the actors. In symbols:

A procedural flow chart that covers the entire concept, from LCC computation to cooperative-game allocation and free-rider evaluation, is shown in

Figure 1. The flow chart covers the following steps: (i) defining the components of life-cycle costs; (ii) discounting costs; (iii) establishing the cost function v(S); (iv) calculating Shapley values for each coalition; (v) identifying free riders and recalculating cost allocations; (vi) assessing fines and buy-in values. Every level of the process and its inherent logic are made evident by this visual framework.

For clarity and reproducibility,

Table 1 summarizes the main parameters and symbols used throughout the Life Cycle Costing and cooperative-game formulations presented in this study.

4. Case Study: Application of the LCC–Cooperative Game Model to Three Operators

The detailed methodological steps are provided in

Appendix A.

This case study examines three operators, designated as “A,” “B,” and “C,” who have chosen to establish a satellite megaconstellation for telecommunications purposes. To implement this megaconstellation, we posit a satellite with a mass of roughly 200 kg, with development costs varying based on the unique attributes of each company. Conversely, launch costs, operational management expenses, and end-of-life (EOL) costs will remain uniform, predicated on the assumption that all three organizations will utilize the same entity for the operational management of the megaconstellation. The environmental costs linked to the megaconstellation are sourced from publicly accessible databases; for computational simplicity, the following elements will be examined: “black carbon from launch,” “aluminum oxides from re-entry,” “NOx from propulsive maneuvers,” and “CO

2 from satellite manufacturing”. Equations (1)–(6) were directly utilized on a reference satellite platform weighing about 200 kg to generate the baseline cost estimates illustrated in

Figure 1 and

Figure 2. Development expenses were calculated using standard engineering-hour labor rates and material procurement costs derived from industry benchmarks for small-satellite manufacture. Current commercial launch service pricing encompasses both set mission fees and variable expenses that correlate with satellite mass. Operational expenses were estimated using data-transmission service prices, yearly insurance premiums from current industrial studies, and ground-segment operation fees. Fuel mass requirements and standard deorbiting service cost factors were utilized to compute end-of-life expenses. Finally, the aforementioned monetization technique was employed to integrate environmental expenses. Although the study does not utilize private industry data, the numerical values are credible and derived from academic literature, open-source databases, and market averages. This ensures the case study is both empirically substantiated and illustrative. In an initial analysis, assuming each company operates independently without collaboration, the resulting cost values are depicted in

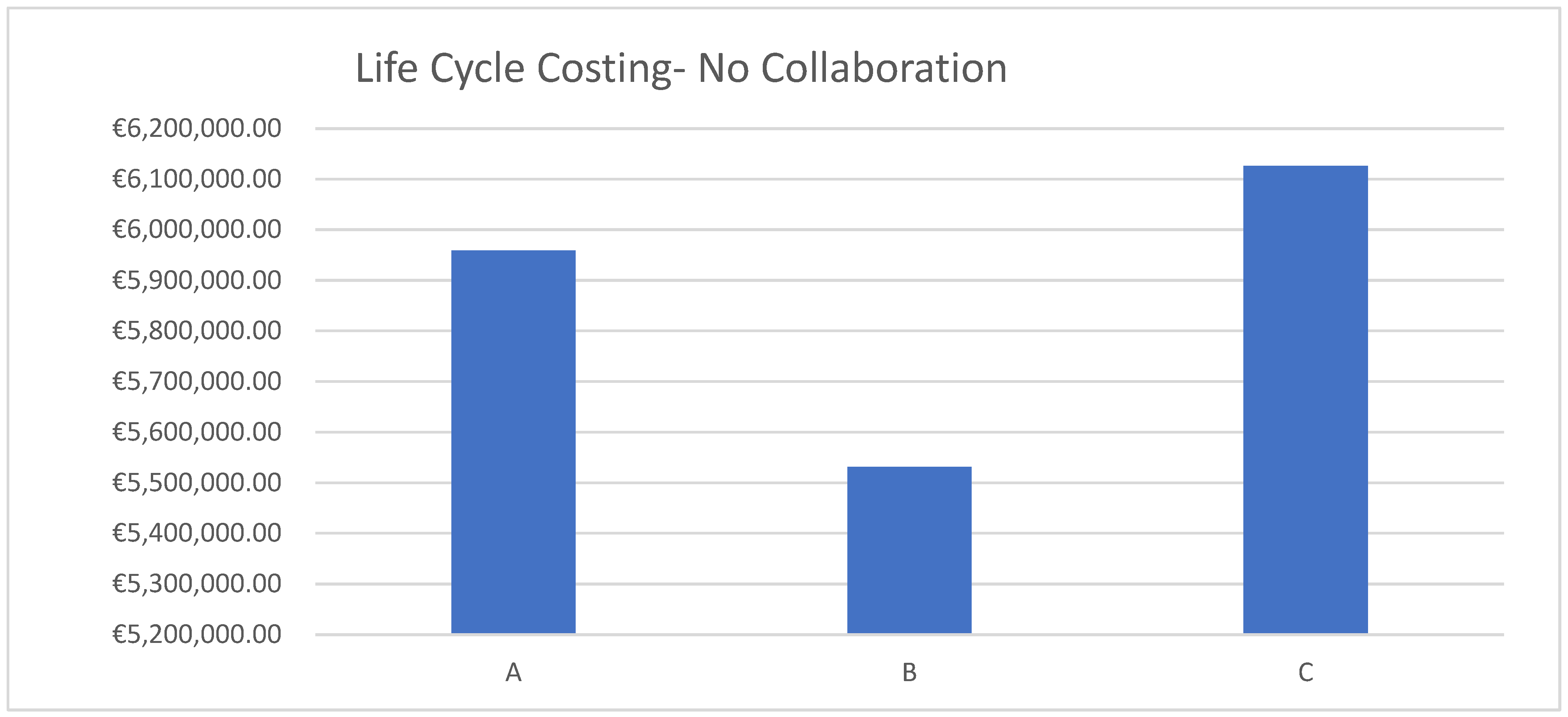

Figure 2.

Figure 2 illustrates the expenditures incurred by operators A, B, and C in establishing their respective megaconstellations independently. The bar chart clearly indicates that the three individuals under examination are not managing their finances equitably. Operator A’s total estimated expenditure is slightly below EUR 6 million, positioning it in the median range relative to the others. Operator B incurs the lowest expenditure, just above EUR 5.5 million, while Operator C has a financial obligation that considerably exceeds EUR 6.1 million. This variation highlights the differences in efficiency, technical-operational skills, and strategic approaches that characterize the three firms. The “no collaboration” scenario highlights several critical economic factors. Initially, each player must assume full financial responsibility for the life-cycle expenses of their own initiatives. This encompasses the development, launch, operational, and termination stages, together with any related environmental costs. This situation results in a substantial disparity in financial risk, particularly for Operator C, who bears considerably higher costs than Operator B. Secondly, the absence of collaboration hinders the attainment of potential synergies that could be utilized. Joint initiatives in development, launch services, or operational management can minimize redundancy, realize economies of scale, and distribute costs more equitably among stakeholders. The absence of collaboration tools generates inefficiencies that jeopardize the project’s economic viability. The identified cost discrepancies suggest the presence of enduring unequal competitive advantages. Operator B, having the lowest expenditures, may gain increased flexibility in reallocating resources or lowering service prices, thereby achieving a stronger market position. Conversely, Operator C may encounter financial challenges, potentially undermining its competitiveness without external support or strategic alliances. The collaboration among partners is illustrated in the accompanying figure (

Figure 3), which highlights the significant impact of active cooperation between the organizations involved in a satellite megaconstellation project.

This figure compares the overall project costs borne by operators A, B, and C under two different scenarios: no collaboration (blue bars) and collaboration (orange bars). This side-by-side representation clearly illustrates the significant economic advantages that cooperation can generate in the context of satellite megaconstellation projects. In the non-collaborative scenario, costs remain relatively high for all three operators, with Operator A close to EUR 6 million, Operator B slightly above EUR 5.5 million, and Operator C just over EUR 6.1 million. However, when collaboration is introduced, a marked reduction in costs is observed for each participant. Operator A sees its cost decrease from around EUR 6 million to just above EUR 4 million, Operator B reduces its expenditure from approximately EUR 5.5 million to EUR 4 million; and Operator C benefits most, lowering its costs from more than EUR 6.1 million to just under EUR 4.5 million. This reduction corresponds to an optimization of roughly 25–27%, confirming the tangible benefits of shared efforts in terms of efficiency and fairness. The collaborative framework allows participants to exploit economies of scale, eliminate redundancies in research and development, share launch and operational infrastructure, and distribute environmental and insurance-related costs more effectively. From a strategic standpoint, the graph demonstrates that cooperation generates a win–win outcome: no actor suffers an increase in costs, and all benefit from substantial reductions. This directly addresses one of the critical challenges of megaconstellation development—namely, the enormous financial burden that individual companies would face if acting alone. By pooling resources, operators can lower their individual exposure while maintaining access to the full benefits of the constellation. Equally important, the chart underscores the role of cooperative game-theory mechanisms—such as the Shapley value—in ensuring that these benefits are distributed fairly among participants. By aligning incentives, such mechanisms promote coalition stability and discourage opportunistic behavior. To make the free-rider mechanism and the associated Shapley value computations more transparent, it is useful to illustrate the procedure with a simple numerical example. Let us consider three operators,

,

, and

, and assume that the total life-cycle cost of each stand-alone project. Suppose all three operators decide to cooperate fully. In that case, the joint LCC is reduced to

which is lower than the sum of the stand-alone projects, reflecting the presence of economies of scale and shared infrastructures. For simplicity, let us further assume that the cost of any two-player coalition is

The Shapley value for each operator is then computed by averaging its marginal contribution across all possible coalition-forming orders. For player

, the marginal contributions are as follows:

A Shapley allocation for A of approximately EUR 4.7 million is derived by averaging the six potential combinations of the three participants. The Shapley values for B and C, yielding EUR 3.8 M and EUR 3.5 M, respectively, can be derived by a comparable methodology. In the “full collaboration” scenario, these values represent the cooperative benchmark. The game is restricted to the group of paying participants P = {A,B} upon the introduction of a free rider F. The free rider utilizes the communal infrastructure without engaging in the collaborative cost-sharing system. In this case, as indicated in Equation (11), the Shapley value is recalibrated solely for the contributing players, and the cost function is redefined on the diminished player set P. The disparity between the overall expenditure incurred by the contributing participants in the presence of the free rider and the cost they would have incurred in a fully cooperative environment devoid of free riding is the supplementary expense attributed to the presence of F, or the buy-in. The additional burden is thereafter distributed among the paying entities based on the weighting scheme outlined in Equations (14)–(16). Employing this method on the LCC values of Operators A, B, and C produces the numerical outcomes presented in

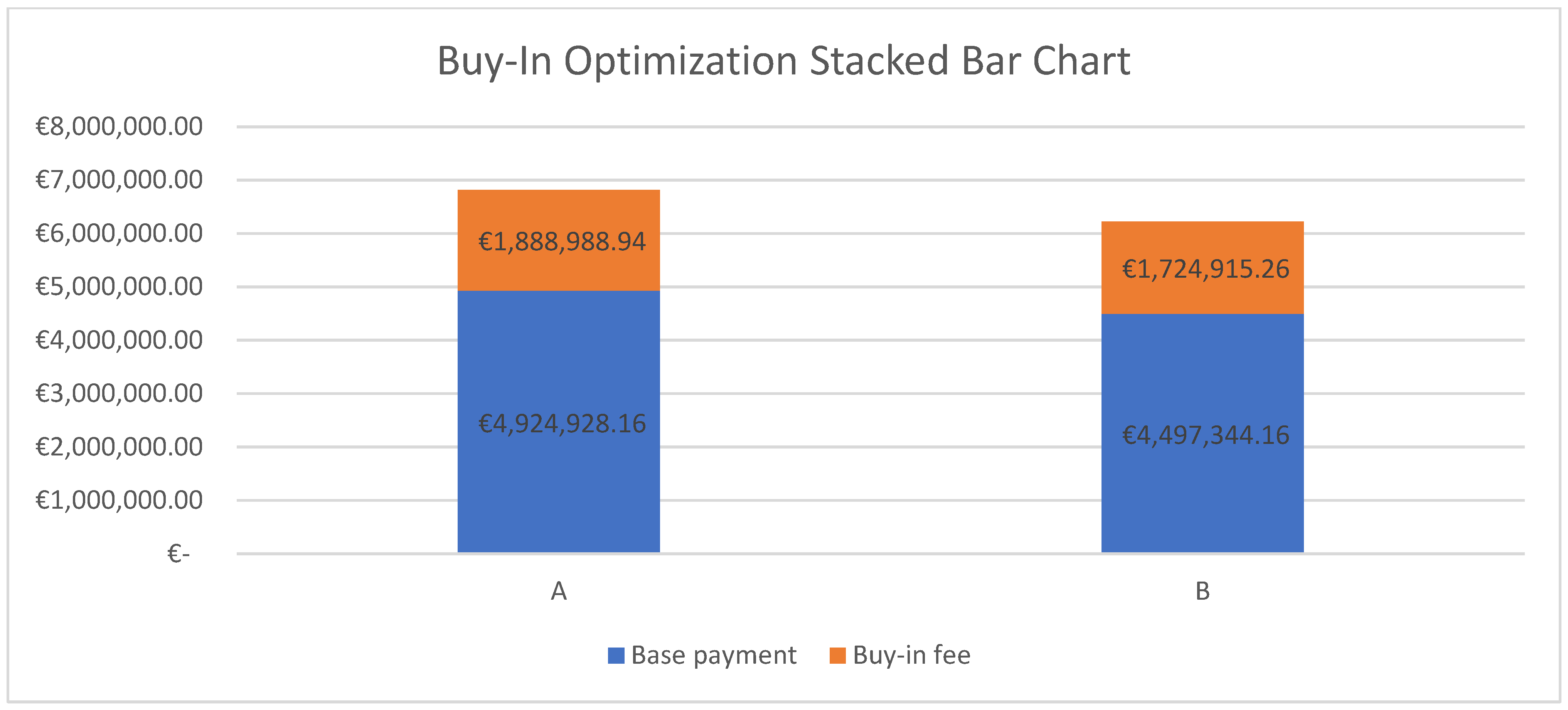

Table 1 and

Figure 3. The subsequent table (

Table 2) delineates a comparison of the three scenarios under examination: the lack of collaboration, complete collaboration, and the presence of a free rider in the process. To enhance the transparency of the free-rider mechanism and the corresponding Shapley value calculations, it is beneficial to demonstrate the process with a straightforward numerical example. Let us consider three operators, A, B and C and assume that the total life-cycle cost of each stand-alone project is given by

The table delineates the expenses incurred by the three entities—A, B, and C—across three separate scenarios: absence of collaboration, complete collaboration, and collaboration with a free rider present. It also presents two supplementary metrics, the Buy-In Value and the Total Cost, which illuminate the redistributive consequences of opportunistic behavior. In the absence of collaboration, costs are disproportionately elevated: approximately EUR 5.96 million for Actor A, EUR 5.53 million for Actor B, and EUR 6.12 million for Actor C. This illustrates the inefficiencies inherent in individual strategies, wherein each operator must independently bear the entire burden of satellite development, launch, operation, end-of-life management, and environmental impact. In the collaborative context, expenses are markedly diminished for all stakeholders. Actor A reduces its cost to approximately EUR 4.43 million, Actor B to EUR 3.97 million, and Actor C to EUR 4.64 million. This indicates a decrease of 25–27%, consistent with the advantages depicted in the preceding chart. The findings validate that collaboration not only improves efficiency but also guarantees a more equitable allocation of costs. The introduction of a free rider significantly transforms the scenario. In this instance, Actors A and B are required to incur elevated expenditures of EUR 4.92 million and EUR 4.50 million, respectively, in contrast to the comprehensive partnership scenario. Actor C, assuming the role of the free rider, disproportionately gains by minimizing its spending to EUR 3.61 million. The Buy-In Value measures the supplementary penalty incurred by the paying participants: approximately EUR 1.89 million for Actor A and EUR 1.72 million for Actor B. When these penalties are combined, the Total Cost escalates considerably, amounting to EUR 6.81 million for A and EUR 6.22 million for B—figures exceeding their individual scenarios. This discovery illustrates the destabilizing impact of free riders on cooperative coalitions. Although formal fairness can be maintained by cost-allocation procedures, the resultant outcome disadvantages cooperative participants, making the partnership less appealing than solo operation. The table underscores the advantages of teamwork and the threats presented by free riders. It underscores the imperative for effective allocation mechanisms—like the Shapley value—coupled with strategic protections to deter opportunistic conduct and guarantee the economic sustainability of coalitions. Although the case study models operators A, B, and C as private entities with symmetrical access to launch and operational services, real-world megaconstellation programs are strongly influenced by the applicable legal framework governing financing responsibilities. National agencies typically bear part of the development or environmental-mitigation costs for state-sponsored operators, whereas private actors remain fully liable for launch, debris-mitigation, and insurance obligations under instruments such as the Outer Space Treaty and national space-law licensing regimes. These asymmetries affect the cost-bearing capacity of each operator and the incentives to join cooperative coalitions. In the revised model description, we explicitly state how such regulatory constraints would modify the distribution of costs and potentially reinforce free-rider behavior. In order to clarify the asymmetric structure of the coalition and to address the Reviewer’s request, we explicitly quantify here the relative weight of Operators A, B, and C within the cooperative case study. In the context of the Shapley-value allocation rule, the weight of each operator corresponds to its marginal contribution to the overall reduction in life-cycle costs generated by cooperation. Using the standalone LCC values reported in

Table 2, we compute the proportional contribution of each operator to the coalition value

. The resulting weights, summarized in

Table 3, show that Operator C provides the largest marginal contribution (38%), reflecting its higher baseline costs and consequently larger impact on collaborative savings. Operator A follows with 34%, whereas Operator B contributes 28%. Making these weights explicit clarifies the heterogeneous influence of each participant in the cooperative framework and provides the quantitative foundation required to interpret the subsequent allocation and stability analysis.

Figure 4 demonstrates how collaborative processes involving free riders create detrimental conditions for the participants.

The stacked bar chart entitled “Buy-In Optimization” clearly illustrates the cost structure encountered by Actors A and B within a cooperative framework that incorporates a free rider. The chart categorizes total expenditure into two elements: the Base Payment (in blue), reflecting costs directly associated with the project, and the Buy-In Fee (in orange), denoting the supplementary penalty incurred by cooperating parties to offset the non-participation of free riders. Actor A’s basic remuneration totals around EUR 4.92 million, indicating cost savings relative to the independent scenario. Nonetheless, when the buy-in charge of approximately EUR 1.89 million is included, the total exceeds EUR 6.81 million. This value exceeds the original expense Actor A would have incurred by functioning autonomously. Actor B encounters a comparable scenario: Its base remuneration is roughly EUR 4.50 million, although the inclusion of a EUR 1.72 million buy-in fee elevates the total expenditure to almost EUR 6.22 million. This number once again exceeds the no-collaboration figure of EUR 5.53 million. The visualization underscores two significant insights. Initially, although cooperative systems aim to minimize costs and equitably allocate them among participants, the emergence of free riders induces a structural disparity. The sanctions imposed to counter non-contributing participants diminish the economic advantages of collaboration and unjustly penalize those who act in good faith. Secondly, the stacked representation highlights the significance of this burden: the orange buy-in component is considerable enough to negate the savings originally achieved by collaboration, elevating expenses beyond the non-collaborative baseline. The chart underscores the imperative of establishing effective allocation procedures to deter free riding from a strategic governance standpoint. In the absence of such safeguards, rational agents may choose to forgo cooperation, viewing it as less beneficial than acting independently. Mechanisms derived from cooperative game theory—such as the Shapley value or other weighted allocations—are crucial for guaranteeing coalition stability, equity, and economic viability. In conclusion, the chart presents persuasive evidence of how free rider dynamics can undermine the advantages of collaboration, transforming a potentially mutually beneficial arrangement into a detrimental outcome for contributing individuals. Ultimately, we can affirm that the findings indicate the Shapley value effectively mitigates free riding by enhancing transparency and ensuring that each participant compensates an amount proportional to their marginal contribution. This diminishes the motivation to deviate and enhances coalition stability. A methodological breakthrough is the integration of LCC and cooperative game theory, which, although distinct, provides a practical instrument for evaluating efficiency, equity, and the vulnerability of coalitions to opportunistic conduct. The findings indicate that although collaboration yields substantial cost reductions, it becomes fragile in the presence of freeloaders unless appropriate governance mechanisms are established.

5. Conclusions

This paper proposes an integrated paradigm that merges cooperative game theory with Life Cycle Costing (LCC) to evaluate the strategic, economic, and environmental sustainability of satellite megaconstellations. The paper contributes to the field by formalizing a model that concurrently incorporates Shapley value-based fairness allocation mechanisms, the monetization of environmental externalities, and discounted life-cycle costs. The paper offers a novel approach to assessing the stability and effectiveness of multi-operator constellations by integrating two traditionally separate analytical domains: cooperative game theory and economic–engineering models. Considering the significance of megaconstellations for the environment, forthcoming model applications ought to examine how outcomes are influenced by variations in discount rates, emission coefficients, and technological degradation, while also systematically revising environmental externalities utilizing discounted LCCA values. Sensitivity analysis is particularly vital in an industry where long-term forecasts amid uncertainty are essential for investment decisions and when operational, technological, and regulatory factors rapidly evolve. The findings also illustrate the significance of the Shapley value in ensuring a transparent and fair cost allocation among participating operators. The analysis confirms that free riding may persist in practice despite the Shapley mechanism promoting equity and perhaps diminishing incentives for opportunistic activity. The expenses eventually escalate for the remaining coalition members when one or more participants benefit from communal infrastructures without providing commensurate contributions. In certain configurations, this additional burden may render collaboration less effective than autonomous strategies, hence jeopardizing coalition stability. This underscores the need for proactive measures and governance mechanisms that might mitigate the incidence and impact of free riders. The results indicate many policy instruments that could facilitate the establishment of more resilient cooperative structures. Licenses for launch and operation based on contributions may necessitate active participation in sustainability efforts, such as coordinated deorbiting operations or debris mitigation, to obtain access to orbital shells or frequency bands. The expenses associated with collision avoidance maneuvers, debris cleanup missions, or inadvertent damages could be partially subsidized by an international compensation or guarantee fund, financed in accordance with operators’ life-cycle costs or environmental impacts. International agreements that include binding dispute-resolution and arbitration mechanisms may ensure transparent management of accountability and cost-sharing conflicts. Finally, incentive-compatible mechanisms that deter chronic free riding and promote cooperative conduct encompass fee reductions, preferential access to launch windows, or spectrum-allocation benefits for compliance operators. The proposed approach would be more relevant, and the long-term sustainability of shared orbital infrastructures would be enhanced if these policy elements were included in the governance of megaconstellations. The study possesses several deficiencies despite its contributions. Valuations of environmental externalities may vary significantly depending on legal frameworks and scientific progress; therefore, the case study employs general cost factors instead of private industry data. Moreover, although real-world interactions may be affected by competitive dynamics, regulatory disparities, and uncertainty, the cooperative model assumes rational conduct and comprehensive knowledge. Consequently, the framework may be augmented in subsequent research by integrating stochastic or probabilistic models, dynamic coalition formation, scenario-based sensitivity assessments, or agent-based modeling methodologies that can encapsulate adaptive behavior across time. The study’s integrated LCC–game-theoretic framework provides valuable insights for researchers, policymakers, and private operators engaged in the design and governance of large-scale space infrastructures, representing an initial step toward a comprehensive evaluation tool for megaconstellations.